Multimodal Quantitative Research on the Emotional Attachment Characteristics between People and the Built Environment Based on the Immersive VR Eye-Tracking Experiment

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- (1)

- The characteristics and differences of participants’ eye-movement behaviors according to different natural and artificial campus landscape elements and features.

- (2)

- The emotional attachment characteristics and differences according to different natural and artificial campus landscape elements and features.

- (3)

- The relationship between eye-movement behavior characteristics and emotional attachment.

2. Materials and Methods

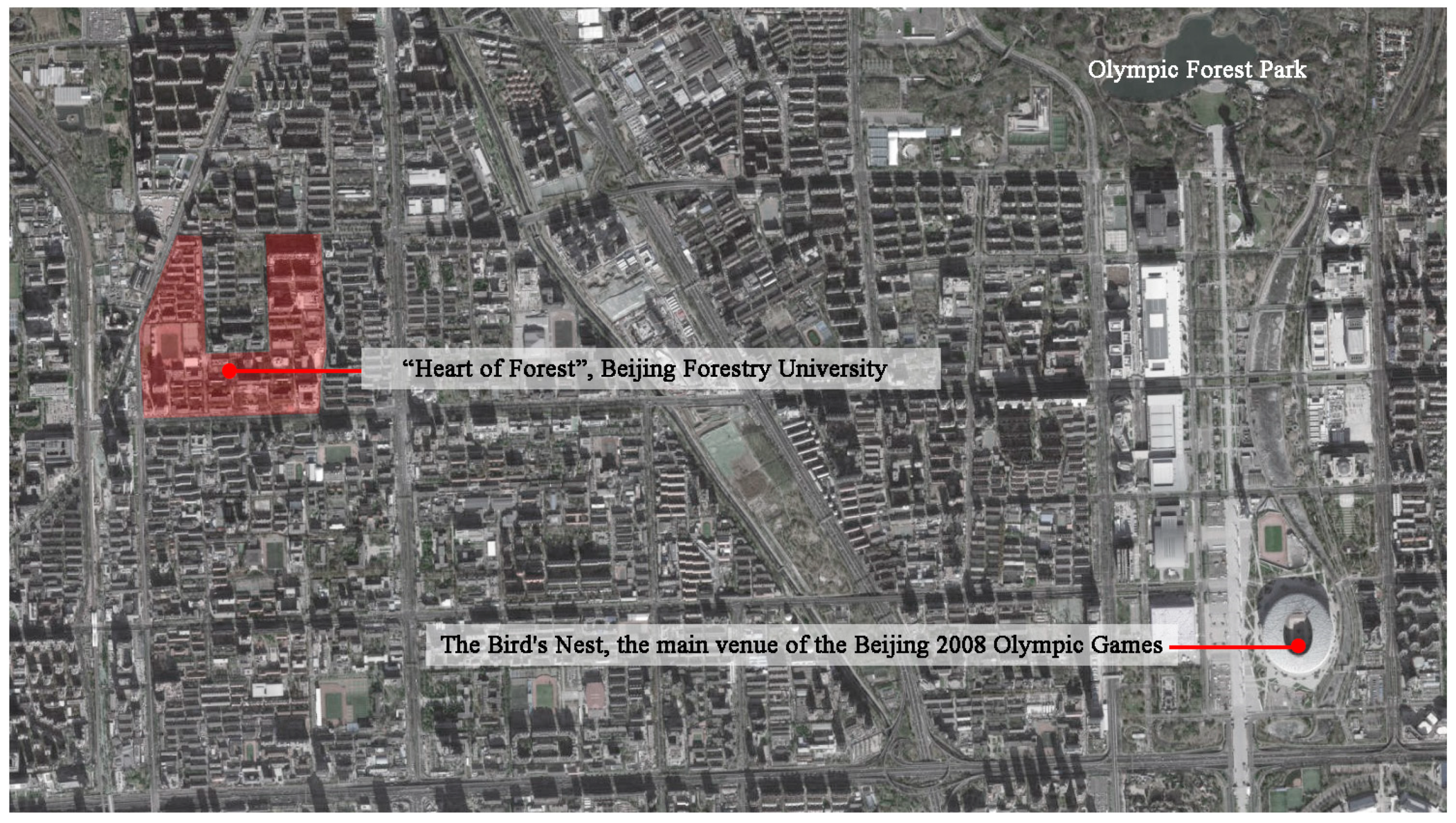

2.1. Research Area and Stimuli

2.2. Participants and Experimental Process

2.3. Eye-Tracking Index Selection and Emotional Attachment Scale Construction

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Influence of Different Types of Landscape Elements on Participants’ Visual Behavior

3.1.1. Differences in the Eye-Movement Indicators for Natural and Artificial Landscape Elements

3.1.2. Differences in Fixation Characteristics in Different Landscape Spaces according to AOI Heat Map

3.2. Influence of Different Landscape Characteristics on Participants’ Emotional Attachment

3.2.1. The Overall Features of Participants’ Emotional Attachment to the Heart of Forest

3.2.2. The Correlation between Place Attachment, Positive and Negative Effect and Attachment to Specific Landscape Characteristics

3.3. Relationship between Participants’ Emotional Attachment and Visual Behavior Concerning Different Types of Landscape Elements

3.3.1. Relationship between Visual Behavior and Emotional Attachment Indexes

3.3.2. Relationship between Visual Behavior and Emotional Attachment Evaluation Factors of Specific Landscape Characteristics

4. Discussion

4.1. Different Artificial and Natural Landscape Elements Have Differences in Observation Mode

4.2. Different Artificial and Natural Landscape Elements Trigger Different Levels and Degree of Emotional Attachment

- (1)

- The spatial composition and temporal characteristics of natural elements in the landscape significantly affect people’s emotional experience.

- (2)

- The diversity of artificial elements and the communicable public space they provide are main factors affecting the degree of students’ emotional attachment.

- (3)

- The use of regional and unique artificial elements can significantly enhance people’s emotional attachment to landscape space.

- (4)

- Whether the interactivity of artificial elements is conducive to emotional experience depends on their later maintenance.

4.3. Connection and Interaction between Visual Behavior and Emotional Attachment to Landscape Space

- (1)

- The connection between different natural and artificial visual landscape elements and students’ emotional attachment to landscape characteristics.

- (2)

- The interaction between students’ visual behavior and emotional attachment to campus landscape space.

4.4. Limitations and Future Research

5. Conclusions

- (1)

- The results of eye-tracking indicators show that artificial elements are more likely to quickly attract people’s visual attention and continuously enhance their interest in the landscape. Combined with the results of the scale, it further shows that artificial elements with regionality, uniqueness and diversity are conducive to significantly promoting people’s emotional attachment, and whether playability and changeability can promote positive emotional experience are closely related to the maintenance of artificial facilities after completion.

- (2)

- For natural elements, a waterscape space composed of water and its surrounding elements is more likely to attract people’s visual attention, while the attractiveness of arbors and shrubs is related to their color and spatial location. Plants with yellow and red color changes in autumn and in the spatial position of the vanishing point of human eyes are more likely to be noticed. Furthermore, the characteristics related to nature are generally conducive to the establishment of students’ emotional attachment, which is not only limited to the natural elements in the landscape, but also includes artificial materials and structures that can reflect the natural texture, time traces and structural logic, such as pavilions that can extract the texture and mechanical characteristics of wood, and rusty steel plate landscape structures that can reflect the texture of materials.

- (3)

- Another important conclusion of this study is that the three-dimensional spatial structure and spatial sequence design of landscape elements will significantly affect people’s visual focus and emotional experience. This emphasizes the difference between experiencing real landscape space and two-dimensional landscape pictures and illustrates the importance of considering the spatial hierarchy of landscape elements and the spatial-temporal behavior of people experiencing the landscape in landscape space design.

- (4)

- The research provides the following possible references for the design theory and management of public landscape space in colleges in the future: for natural landscape elements, the design methods such as configuring plants with unique seasonal characteristics, creating more waterfront rest spaces, and arranging the elements in the space and time sequence of human perception may exert a significant impact on students’ emotional experience. For artificial landscape elements, the design and construction of structures using natural materials and structures, and the setting of regional, cultural or commemorative installations, can effectively promote the construction of students’ emotional attachment. For the interactive landscape elements designed in combination with new technologies, it is necessary to rely on regular maintenance and management after completion to ensure their normal use, otherwise it is easy to trigger negative emotions in students.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kelz, C.; Evans, G.W.; Röderer, K. The restorative effects of redesigning the schoolyard: A multi-methodological, quasi-experimental study in rural Austrian middle schools. Environ. Behav. 2015, 47, 119–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Lin, Y.; You, D.; Zhang, W.; Huang, Q.; van den Bosch, C.; Lan, S. The relationship between self-rated naturalness of university green space and students’ restoration and health. Urban For. Green 2018, 34, 259–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hipp, J.A.; Gulwadi, G.B.; Alves, S.; Sequeira, S. The relationship between perceived greenness and perceived restorativeness of university campuses and student-reported quality of life. Environ. Behav. 2016, 48, 1292–1308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akpinar, A. How is high school greenness related to students’ restoration and health? Urban For. Urban Green. 2016, 16, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lau, S.S.; Yang, F. Introducing healing gardens into a compact university campus: Design natural space to create healthy and sustainable campuses. Landsc. Res. 2009, 34, 55–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andre, E.K.; Williams, N.; Schwartz, F.; Bullard, C. Benefits of campus outdoor recreation programs: A review of the literature. J. Outdoor Recreat. Educ. Leadersh. 2017, 9, 15–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandisauskiene, A.; Buksnyte-Marmiene, L.; Cesnaviciene, J.; Daugirdiene, A.; Kemeryte-Ivanauskiene, E.; Nedzinskaite-Maciuniene, R. Sustainable school environment as a landscape for secondary school students’ engagement in learning. Sustainability 2021, 13, 11714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.; Tu, X.; Huang, G.; Fang, X.; Kong, L.; Wu, J. Urban greenspace helps ameliorate people’s negative sentiments during the COVID-19 pandemic: The case of Beijing. Build. Environ. 2022, 223, 109449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.Y.; Cao, H.; Leung, D.Y.; Mak, Y.W. The psychological impacts of a COVID-19 outbreak on college students in China: A longitudinal study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 3933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, W.; Wu, Y.; Li, W.; Liu, F. Influence of Classroom Colour Environment on College Students’ Emotions during Campus Lockdown in the COVID-19 Post-Pandemic Era—A Case Study in Harbin, China. Buildings 2022, 12, 1873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, L.; Peng, X.; Aniche, L.Q.; Scholten, P.H.; Ensenado, E.M. Urban renewal as policy innovation in China: From growth stimulation to sustainable development. Public Adm. Dev. 2021, 41, 23–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, Z.; Liu, G.; Lang, W.; Shrestha, A.; Martek, I. Strategic approaches to sustainable urban renewal in developing countries: A case study of Shenzhen, China. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Jiang, W.; Lu, T. Landscape characteristics of university campus in relation to aesthetic quality and recreational preference. Urban For. Urban Green. 2021, 66, 127389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghorbanzadeh, M. A Study on the quality of campus landscape on students’ attendance at the university campus. Civ. Eng. J. 2019, 5, 950–962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hami, A.; Abdi, B. Students’ landscaping preferences for open spaces for their campus environment. Indoor Built Environ. 2021, 30, 87–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnheim, R. Art and Visual Perception: A Psychology of the Creative Eye; University of California Press: Berkeley, CA, USA, 1954. [Google Scholar]

- Gholami, Y.; Taghvaei, S.H.; Norouzian-Maleki, S.; Mansouri Sepehr, R. Identifying the stimulus of visual perception based on Eye-tracking in Urban Parks: Case Study of Mellat Park in Tehran. J. For. Res. 2021, 26, 91–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Qu, H.; Ma, Y.; Wang, K.; Qu, H. Restorative benefits of urban green space: Physiological, psychological restoration and eye movement analysis. J. Environ. Manag. 2022, 301, 113930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, N.; Liu, C. Towards landscape visual quality evaluation: Methodologies, technologies, and recommendations. Ecol. Indic. 2022, 142, 109174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mundher, R.; Abu Bakar, S.; Al-Helli, M.; Gao, H.; Al-Sharaa, A.; Mohd Yusof, M.J.; Maulan, S.; Aziz, A. Visual Aesthetic Quality Assessment of Urban Forests: A Conceptual Framework. Urban Sci. 2022, 6, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appleton, J. The Experience of Landscape; John Wiley & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, L.; Winterbottom, D.; Liu, J. Towards a “Positive Landscape”: An Integrated Theoretical Model of Landscape Preference Based on Cognitive Neuroscience. Sustainability 2023, 15, 6141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, R.; Kaplan, S.; Brown, T. Environmental preference: A comparison of four domains of predictors. Environ. Behav. 1989, 21, 509–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, R.; Kaplan, S. The Experience of Nature: A Psychological Perspective; Cambridge University Press: London, UK, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Daniel, C.T. Measuring Landscape Esthetics: The Scenic Beauty Estimation Method; Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Forest and Range Experiment Station: Fort Collins, CO, USA, 1976; Volume 167. [Google Scholar]

- Osgood, C.E. Semantic differential technique in the comparative study of cultures. Am. Anthropol. 1964, 66, 171–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arthur, L.M.; Daniel, T.C.; Boster, R.S. Scenic assessment: An overview. Landsc. Plan. 1977, 4, 109–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlson, A.A. On the possibility of quantifying scenic beauty. Landsc. Plan. 1977, 4, 131–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Cen, Q.; Qiu, H. Effects of urban waterfront park landscape elements on visual behavior and public preference: Evidence from eye-tracking experiments. Urban For. Urban Green. 2023, 82, 127889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahani, A.; Saffariha, M.; Barzegar, P. Landscape aesthetic quality assessment of forest lands: An application of machine learning approach. Soft Comput. 2023, 27, 6671–6686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Hu, M.; Zhao, B. Interactions between forest landscape elements and eye movement behavior under audio-visual integrated conditions. J. For. Res. 2020, 25, 21–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R. Integrating ergonomics data and emotional scale to analyze people’s emotional attachment to different landscape features in the Wudaokou Urban Park. Front. Archit. Res. 2023, 12, 175–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R. Research and evaluation on students’ emotional attachment to campus landscape renewal coupling emotional attachment scale and public sentiment analysis: A case study of the “Heart of Forest” in Beijing Forestry University. Front. Psychol. 2023, 14, 1250441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Navarro, J.P.; Martínez-Selva, J.M.; Torrente, G.; Román, F. Psychophysiological, behavioral, and cognitive indices of the emotional response: A factor-analytic study. Span. J. Psychol. 2008, 11, 16–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleureau, J.; Guillotel, P.; Huynh-Thu, Q. Physiological-based affect event detector for entertainment video applications. IEEE Trans. Affect. Comput. 2012, 3, 379–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, S.M.; Chakrabarti, D.; Karmakar, S. Emotion and interior space design: An ergonomic perspective. Work 2012, 41, 1072–1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buker, T.; Schmitt, T.; Miehling, J.; Wartzack, S. Exploring the importance of a usable and emotional product design from the user’s perspective. Ergonomics 2023, 66, 580–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.; Kim, N. Quantifying emotions in architectural environments using biometrics. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 9998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamani, M.; Kheirollahi, M.; Asghari Ebrahim Absd, M.J.; Rezaee, H.; Vafaee, F. Evaluating the Impact of Architectural Space on Human Emotions Using Biometrics Data. Creat. City Des. 2022, 5, 65–80. [Google Scholar]

- Gomes, N.; Pato, M.; Lourenço, A.R.; Datia, N. A Survey on Wearable Sensors for Mental Health Monitoring. Sensors 2023, 23, 1330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rad, P.N.; Behzadi, F.; Yazdanfar, S.A.; Ghamari, H.; Zabeh, E.; Lashgari, R. Exploring Methodological Approaches of Experimental Studies in the Field of Neuroarchitecture: A Systematic Review. Health Environ. Res. Des. J. 2023, 16, 284–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shadiev, R.; Li, D. A review study on eye-tracking technology usage in immersive virtual reality learning environments. Comput. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 2023, 196, 104681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Posner, M.I.; Nissen, M.J.; Klein, R.M. Visual dominance: An information-processing account of its origins and significance. Psychol. Rev. 1976, 83, 157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morimoto, C.H.; Mimica, M.R. Eye gaze tracking techniques for interactive applications. Comput. Vis. Image Underst. 2005, 98, 4–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodge, R.; Cline, T.S. The angle velocity of eye movements. Psychol. Rev. 1901, 8, 145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wickens, C.D.; Xu, X.; Helleberg, J.; Carbonari, R.; Marsh, R. The allocation of visual attention for aircraft traffic monitoring and avoidance: Baseline measures and implications for freeflight; University of Illinois Institute of Aviation Technical Report (ARL-00-2/FAA-00-2); Aviation Research Laboratory: Savoy, IL, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Aoki, H.; Itoh, K. Analysis of influences of aural information on viewers’ visual cognition during viewing of television commercials by use of eye tracking technique. Jpn. J. Ergon. 2001, 37, 246–247. [Google Scholar]

- Eckstein, M.K.; Guerra-Carrillo, B.; Singley, A.T.M.; Bunge, S.A. Beyond eye gaze: What else can eyetracking reveal about cognition and cognitive development? Dev. Cogn. Neurosci. 2017, 25, 69–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meißner, M.; Pfeiffer, J.; Pfeiffer, T.; Oppewal, H. Combining virtual reality and mobile eye tracking to provide a naturalistic experimental environment for shopper research. J. Bus. Res. 2019, 100, 445–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wedel, M.; Pieters, R. A review of eye-tracking research in marketing. Rev. Mark. Res. 2008, 4, 123–147. [Google Scholar]

- Noland, R.B.; Weiner, M.D.; Gao, D.; Cook, M.P.; Nelessen, A. Eye-tracking technology, visual preference surveys, and urban design: Preliminary evidence of an effective methodology. J. Urban. Int. Res. Placemaking Urban Sustain. 2017, 10, 98–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Z.; Pesarakli, H. Seeing Is Believing: Using Eye-Tracking Devices in Environmental Research. HERD Health Environ. Res. Des. J. 2023, 16, 15–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, P.; Xiao, X.; Jordan, E. Tourists’ visual attention and stress intensity in nature-based tourism destinations: An eye-tracking study during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Travel Res. 2023, 62, 1667–1684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schirpke, U.; Tasser, E.; Lavdas, A.A. Potential of eye-tracking simulation software for analyzing landscape preferences. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0273519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Zhang, T.; Zhang, W.; Meng, H.; Zhang, Z. Research on Visual Behavior Characteristics and Cognitive Evaluation of Different Types of Forest Landscape Spaces. Urban For. Urban Green. 2020, 54, 126788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, N.; Zhang, R.; Le, D.; Moyle, B. A review of eye-tracking research in tourism. Curr. Issues Tour. 2019, 22, 1244–1261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Zhang, Z.; Jing, F.; Gao, J.; Ma, J.; Shao, G.; Noel, S. An evaluation of urban green space in Shanghai, China, using eye tracking. Urban For. Urban Green. 2020, 56, 126903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, H.; Wang, P.; Zhou, J.; Zhang, S.; Li, Y. Investigating Influence of Visual Elements of Arcade Buildings and Streetscapes on Place Identity Using Eye-Tracking and Semantic Differential Methods. Buildings 2023, 13, 1580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Ruan, R.; Deng, W.; Gao, J. The effect of visual attention process and thinking styles on environmental aesthetic preference: An eye-tracking study. Front. Psychol. 2023, 13, 1027742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nordh, H.; Hagerhall, C.M.; Holmqvist, K. Tracking restorative components: Patterns in eye movements as a consequence of a restorative rating task. Landsc. Res. 2013, 38, 101–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amati, M.; Parmehr, E.G.; McCarthy, C.; Sita, J. How eye-catching are natural features when walking through a park? Eye-tracking responses to videos of walks. Urban For. Urban Green. 2018, 31, 67–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Hu, M.; Zhao, B. Audio-visual interactive evaluation of the forest landscape based on eye-tracking experiments. Urban For. Urban Green. 2019, 46, 126476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pettersson, J.; Albo, A.; Eriksson, J.; Larsson, P.; Falkman, K.; Falkman, P. Cognitive ability evaluation using virtual reality and eye tracking. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE international conference on computational intelligence and virtual environments for measurement systems and applications (CIVEMSA), Ottawa, ON, Canada, 12–13 June 2018; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Sipatchin, A.; Wahl, S.; Rifai, K. Eye-tracking for clinical ophthalmology with virtual reality (vr): A case study of the htc vive pro eye’s usability. Healthcare 2021, 9, 180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Dai, Y.; Zan, P.; Zhang, S.; Sun, X.; Zhou, J. Research and Evaluation of the Mountain Settlement Space Based on the Theory of “Flânuer” in the Digital Age—Taking Yangchan Village in Huangshan City, Anhui Province, as an Example. J. Asian Archit. Build. Eng. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cottet, M.; Vaudor, L.; Tronchère, H.; Roux-Michollet, D.; Augendre, M.; Brault, V. Using gaze behavior to gain insights into the impacts of naturalness on city dwellers’ perceptions and valuation of a landscape. J. Environ. Psychol. 2018, 60, 9–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dupont, L.; Ooms, K.; Antrop, M.; Van Eetvelde, V. Comparing saliency maps and eye-tracking focus maps: The potential use in visual impact assessment based on landscape photographs. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2016, 148, 17–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dupont, L.; Ooms, K.; Antrop, M.; Van Eetvelde, V. Testing the validity of a saliency-based method for visual assessment of constructions in the landscape. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2017, 167, 325–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Jamiy, F.; Marsh, R. Survey on depth perception in head mounted displays: Distance estimation in virtual reality, augmented reality, and mixed reality. IET Image Process. 2019, 13, 707–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paes, D.; Arantes, E.; Irizarry, J. Immersive environment for improving the understanding of architectural 3D models: Comparing user spatial perception between immersive and traditional virtual reality systems. Autom. Constr. 2017, 84, 292–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, S.; Zhao, N.; Zhang, J.; Xue, T.; Liu, P.; Xu, S.; Xu, D. Landscape visual quality assessment based on eye movement: College student eye-tracking experiments on tourism landscape pictures. Resour. Sci. 2017, 39, 1137–1147. [Google Scholar]

- Van den Berg, A.E.; Joye, Y.; Koole, S.L. Why viewing nature is more fascinating and restorative than viewing buildings: A closer look at perceived complexity. Urban For. Urban Green. 2016, 20, 397–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scannell, L.; Gifford, R. Defining place attachment: A tripartite organizing framework. J. Environ. Psychol. 2010, 30, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scannell, L.; Gifford, R. The experienced psychological benefits of place attachment. J. Environ. Psychol. 2017, 51, 256–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, D.; Clark, L.A.; Tellegen, A. Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: The PANAS scales. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1988, 54, 1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.-D.; You, R.-H.; Liu, H.; Chung, P.-K. Chinese version of the international positive and negative affect schedule short form: Factor structure and measurement invariance. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2020, 18, 285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, A.S.-H.; Lin, Y.-J. The effect of landscape colour, complexity and preference on viewing behaviour. Landsc. Res. 2020, 45, 214–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsadek, M.; Sun, M.; Sugiyama, R.; Fujii, E. Cross-cultural comparison of physiological and psychological responses to different garden styles. Urban For. Urban Green. 2019, 38, 74–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dupont, L.; Antrop, M.; Van Eetvelde, V. Does landscape related expertise influence the visual perception of landscape photographs? Implications for participatory landscape planning and management. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2015, 141, 68–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Eye-Tracking Indicators | Definition | Corresponding Emotional Representations |

|---|---|---|

| TTFF (time to first fixation) | The amount of time that it takes a participant to look at a specific AOI from stimulus onset. | TTFF can represent both bottom-up stimulus-driven and top-down attention-driven searches. The shorter the TTFF, the stronger the attraction of the object to the participant, which is more conducive to the elicitation of emotions. |

| FC (fixation count) | The total number of fixations generated by participants when viewing each AOI. | A higher FC indicates a stronger interest in the corresponding AOI, which may correspond to a stronger emotional attachment of participants. |

| MFD (mean fixation duration) | The average length of fixation generated by participants when viewing each AOI. | The longer the MFD, the higher the participant’s attention to landscape elements or spaces, possibly indicating greater interest and emotional attachment. |

| VC (visit count) | The times a participant returned their gaze to a particular spot, defined by an AOI. | The VC indicates the landscape element or space which repeatedly attracted the participant (for better or worse). A higher VC indicates that the AOIs were more attractive to participants, corresponding to a stronger emotional attachment experience. |

| MPD (mean pupil diameter) | The average value of the change in pupil size when participants viewed the 10 landscape panoramic pictures. | Changes in MPD are directly associated with changes in participants’ emotions, but do not necessarily correspond to positive or negative emotions. |

| Very Slightly or Not at All | Extremely | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. interested | 1 [ ] | 2 [ ] | 3 [ ] | 4 [ ] | 5 [ ] |

| 2. distressed | 1 [ ] | 2 [ ] | 3 [ ] | 4 [ ] | 5 [ ] |

| 3. excited | 1 [ ] | 2 [ ] | 3 [ ] | 4 [ ] | 5 [ ] |

| 4. upset | 1 [ ] | 2 [ ] | 3 [ ] | 4 [ ] | 5 [ ] |

| 5. strong | 1 [ ] | 2 [ ] | 3 [ ] | 4 [ ] | 5 [ ] |

| 6. guilty | 1 [ ] | 2 [ ] | 3 [ ] | 4 [ ] | 5 [ ] |

| 7. scared | 1 [ ] | 2 [ ] | 3 [ ] | 4 [ ] | 5 [ ] |

| 8. hostile | 1 [ ] | 2 [ ] | 3 [ ] | 4 [ ] | 5 [ ] |

| 9. enthusiastic | 1 [ ] | 2 [ ] | 3 [ ] | 4 [ ] | 5 [ ] |

| 10. proud | 1 [ ] | 2 [ ] | 3 [ ] | 4 [ ] | 5 [ ] |

| 11. irritable | 1 [ ] | 2 [ ] | 3 [ ] | 4 [ ] | 5 [ ] |

| 12. alert | 1 [ ] | 2 [ ] | 3 [ ] | 4 [ ] | 5 [ ] |

| 13. ashamed | 1 [ ] | 2 [ ] | 3 [ ] | 4 [ ] | 5 [ ] |

| 14. inspired | 1 [ ] | 2 [ ] | 3 [ ] | 4 [ ] | 5 [ ] |

| 15. nervous | 1 [ ] | 2 [ ] | 3 [ ] | 4 [ ] | 5 [ ] |

| 16. determined | 1 [ ] | 2 [ ] | 3 [ ] | 4 [ ] | 5 [ ] |

| 17.attentive | 1 [ ] | 2 [ ] | 3 [ ] | 4 [ ] | 5 [ ] |

| 18. jittery | 1 [ ] | 2 [ ] | 3 [ ] | 4 [ ] | 5 [ ] |

| 19. active | 1 [ ] | 2 [ ] | 3 [ ] | 4 [ ] | 5 [ ] |

| 20. afraid | 1 [ ] | 2 [ ] | 3 [ ] | 4 [ ] | 5 [ ] |

| Very Slightly or Not at All | Extremely | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Everything about this place is a reflection of me. | 1 [ ] | 2 [ ] | 3 [ ] | 4 [ ] | 5 [ ] | 6 [ ] | 7 [ ] |

| This place says very little about who I am. | 1 [ ] | 2 [ ] | 3 [ ] | 4 [ ] | 5 [ ] | 6 [ ] | 7 [ ] |

| I feel relaxed when I’m in this place. | 1 [ ] | 2 [ ] | 3 [ ] | 4 [ ] | 5 [ ] | 6 [ ] | 7 [ ] |

| I feel happiest when I’m in this place. | 1 [ ] | 2 [ ] | 3 [ ] | 4 [ ] | 5 [ ] | 6 [ ] | 7 [ ] |

| This place is my favorite place to be. | 1 [ ] | 2 [ ] | 3 [ ] | 4 [ ] | 5 [ ] | 6 [ ] | 7 [ ] |

| I really miss this place when I’m away from it for too long. | 1 [ ] | 2 [ ] | 3 [ ] | 4 [ ] | 5 [ ] | 6 [ ] | 7 [ ] |

| I feel that I can really be myself in this place. | 1 [ ] | 2 [ ] | 3 [ ] | 4 [ ] | 5 [ ] | 6 [ ] | 7 [ ] |

| This place is the best place for doing the things I enjoy most. | 1 [ ] | 2 [ ] | 3 [ ] | 4 [ ] | 5 [ ] | 6 [ ] | 7 [ ] |

| For doing the things that I enjoy most, no other place can compare to this place. | 1 [ ] | 2 [ ] | 3 [ ] | 4 [ ] | 5 [ ] | 6 [ ] | 7 [ ] |

| This place is not a good place to do the things I most like to do. | 1 [ ] | 2 [ ] | 3 [ ] | 4 [ ] | 5 [ ] | 6 [ ] | 7 [ ] |

| This place reflects the type of person I am. | 1 [ ] | 2 [ ] | 3 [ ] | 4 [ ] | 5 [ ] | 6 [ ] | 7 [ ] |

| As far as I am concerned, there are better places to be than in this place. | 1 [ ] | 2 [ ] | 3 [ ] | 4 [ ] | 5 [ ] | 6 [ ] | 7 [ ] |

| The spiritual nature of the area ties me to this place. | 1 [ ] | 2 [ ] | 3 [ ] | 4 [ ] | 5 [ ] | 6 [ ] | 7 [ ] |

| I feel that this place is my home. | 1 [ ] | 2 [ ] | 3 [ ] | 4 [ ] | 5 [ ] | 6 [ ] | 7 [ ] |

| I intend to continue staying in or around this place for the next few years. | 1 [ ] | 2 [ ] | 3 [ ] | 4 [ ] | 5 [ ] | 6 [ ] | 7 [ ] |

| I have the feeling that this place constitutes a security base for me. | 1 [ ] | 2 [ ] | 3 [ ] | 4 [ ] | 5 [ ] | 6 [ ] | 7 [ ] |

| I feel a connection to the visual landscape of the area. | 1 [ ] | 2 [ ] | 3 [ ] | 4 [ ] | 5 [ ] | 6 [ ] | 7 [ ] |

| This place is an important part of my life. | 1 [ ] | 2 [ ] | 3 [ ] | 4 [ ] | 5 [ ] | 6 [ ] | 7 [ ] |

| I feel proud of this place. | 1 [ ] | 2 [ ] | 3 [ ] | 4 [ ] | 5 [ ] | 6 [ ] | 7 [ ] |

| I am totally involved and committed to my school, classmates and neighborhood. | 1 [ ] | 2 [ ] | 3 [ ] | 4 [ ] | 5 [ ] | 6 [ ] | 7 [ ] |

| Very Slightly or Not at All | Extremely | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. material | 1 [ ] | 2 [ ] | 3 [ ] | 4 [ ] | 5 [ ] | 6 [ ] | 7 [ ] |

| 2. color | 1 [ ] | 2 [ ] | 3 [ ] | 4 [ ] | 5 [ ] | 6 [ ] | 7 [ ] |

| 3. natural-related feature | 1 [ ] | 2 [ ] | 3 [ ] | 4 [ ] | 5 [ ] | 6 [ ] | 7 [ ] |

| 4. form and structure | 1 [ ] | 2 [ ] | 3 [ ] | 4 [ ] | 5 [ ] | 6 [ ] | 7 [ ] |

| 5. privacy | 1 [ ] | 2 [ ] | 3 [ ] | 4 [ ] | 5 [ ] | 6 [ ] | 7 [ ] |

| 6. diversity | 1 [ ] | 2 [ ] | 3 [ ] | 4 [ ] | 5 [ ] | 6 [ ] | 7 [ ] |

| 7. sociability | 1 [ ] | 2 [ ] | 3 [ ] | 4 [ ] | 5 [ ] | 6 [ ] | 7 [ ] |

| 8. regionality | 1 [ ] | 2 [ ] | 3 [ ] | 4 [ ] | 5 [ ] | 6 [ ] | 7 [ ] |

| 9. playability | 1 [ ] | 2 [ ] | 3 [ ] | 4 [ ] | 5 [ ] | 6 [ ] | 7 [ ] |

| 10. uniqueness | 1 [ ] | 2 [ ] | 3 [ ] | 4 [ ] | 5 [ ] | 6 [ ] | 7 [ ] |

| 11. changeability | 1 [ ] | 2 [ ] | 3 [ ] | 4 [ ] | 5 [ ] | 6 [ ] | 7 [ ] |

| TTFF (s) | MFD (s) | FC (n) | VC (n) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall Difference | 0.000 ** | 0.000 ** | 0.000 ** | 0.000 ** | |

| Difference among specific landscape elements | |||||

| Natural elements | Natural waters (a) | 81.31 (b**, c**, d**, e**, f**, g**, h**, j**) | 0.86 (b**, c**, d**, e**, g**, h**, i**, j**) | 35.70 (b**, c**, d**, e**, f**, g**, h*, i**) | 16.17 (b**, c**, d**, e**, f**, g**, h**, i**) |

| Arbors (b) | 194.90 (a**, c**, d**, e**, f**, g**, h**, i**, j**) | 3.79 (a**, d**, e**, f**, g**, h**, i**, j**) | 187.97 (a**, c**, d**, e**, f**, g**, h**, i**, j**) | 62.78 (a**, c**, d**, e**, f**, g**, h**, i**, j**) | |

| Shrubs and lawns (c) | 340.24 (a**, b**, d**, e**, f**, g**, h**, i**, j**) | 3.68 (a**, d**, e**, f**, g**, h**, i**, j**) | 85.22 (a**, b**, d**, e**, f**, g**, h**, i**, j**) | 42.46 (a**, b**, d**, e**, f**, g**, h**, i**, j**) | |

| Stones (d) | 112.29 (a**, b**, c**, e**, f**, g**, h**, j**) | 1.38 (a**, b**, c**, e**, g**, h**, i**, j**) | 17.90 (a**, b**, c**, g**, h**, i**, j**) | 9.72 (a**, b**, c**, e**, g**, h**, i**, j**) | |

| Artificial elements | Wood pavement (e) | 24.41 (a**, b**, c**, d**, f**, h**, i**) | 0.57 (a**, b**, c**, d**, f**, i**, j**) | 15.60 (a**, b**, c**, f*, h**, i**, j**) | 6.09 (a**, b**, c**, d**, f**, g**, i**, j**) |

| Slate and stone pavement (f) | 34.37 (a**, b**, c**, d**, e**, h**, i**, j**) | 0.83 (b**, c**, d**, e**, g**, h**, i**, j**) | 22.69 (a**, b**, c**, e*, g**, h**, i**, j**) | 11.33 (a**, b**, c**, e**, g**, h**, i**, j*) | |

| Cement pavement (g) | 26.72 (a**, b**, c**, d**, f**, h**, i**) | 0.54 (a**, b**, c**, d**, f**, i**, j**) | 7.90 (a**, b**, c**, d**, e**, f**, h**, i**, j**) | 3.87 (a**, b**, c**, d**, e**, f**, h**, i**, j**) | |

| Rusty steel plate (h) | 12.79 (a**, b**, c**, d**, e**, f**, g**, i**, j**) | 0.40 (a**, b**, c**, d**, f**, i**, j**) | 48.26 (a*, b**, c**, d**, e**, f**, g**) | 6.91 (a**, b**, c**, d**, f**, g**, i**, j**) | |

| Pavilions and chairs (i) | 93.60 (b**, c**, e**, f**, g**, h**, j**) | 2.09 (a**, b**, c**, d**, e**, f**, g**, h**) | 50.96 (a**, b**, c**, d**, e**, f**, g**) | 22.59 (a**, b**, c**, d**, e**, f**, g**, h**, j**) | |

| Symbols (logo, picture, herbarium, etc) (j) | 21.47 (a**, b**, c**, d**, f**, h**, i**) | 1.87 (a**, b**, c**, d**, e**, f**, g**, h**) | 44.84 (b**, c**, d**, e**, f**, g**) | 14.01 (b**, c**, d**, e**, f*, g**, h**, i**) | |

| n | 90 | 90 | 90 | 90 | |

| α | Mean | SD | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Place Attachment | 0.851 | 4.39 | 0.77 |

| Positive affect | 0.775 | 2.54 | 0.59 |

| Negative affect | 0.790 | 1.27 | 0.33 |

| Overall attachment to landscape characteristics | 0.843 | 4.96 | 0.83 |

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. positive effect | 1.000 | ||||||||||||||

| 2. negative effect | 0.059 | 1.000 | |||||||||||||

| 3. place attachment | 0.507 ** | −0.104 | 1.000 | ||||||||||||

| 4. material | 0.276 ** | −0.036 | 0.312 ** | 1.000 | |||||||||||

| 5. color | 0.192 | −0.171 | 0.465 ** | 0.401 ** | 1.000 | ||||||||||

| 6. natural-related feature | 0.155 | −0.155 | 0.363 ** | 0.494 ** | 0.630 ** | 1.000 | |||||||||

| 7. form and structure | 0.318 ** | −0.193 | 0.417 ** | 0.468 ** | 0.366 ** | 0.491 ** | 1.000 | ||||||||

| 8. privacy | 0.309 ** | −0.152 | 0.403 ** | 0.040 | 0.352 ** | 0.064 | 0.237 * | 1.000 | |||||||

| 9. diversity | 0.246 * | −0.321 ** | 0.488 ** | 0.313 ** | 0.409 ** | 0.448 ** | 0.485 ** | 0.361 ** | 1.000 | ||||||

| 10. sociability | 0.307 ** | −0.083 | 0.548 ** | 0.311 ** | 0.323 ** | 0.240 * | 0.392 ** | 0.122 | 0.573 ** | 1.000 | |||||

| 11. regionality | 0.311 ** | −0.315 ** | 0.370 ** | 0.236 * | 0.216 * | 0.269 * | 0.361 ** | 0.256 * | 0.414 ** | 0.314 ** | 1.000 | ||||

| 12. playability | 0.281 ** | −0.107 | 0.338 ** | 0.278 ** | 0.122 | 0.221 * | 0.319 ** | 0.407 ** | 0.518 ** | 0.248 * | 0.300 ** | 1.000 | |||

| 13. uniqueness | 0.225 * | −0.302 ** | 0.446 ** | 0.316 ** | 0.433 ** | 0.451 ** | 0.382 ** | 0.251 * | 0.498 ** | 0.407 ** | 0.491 ** | 0.465 ** | 1.000 | ||

| 14. changeability | 0.113 | −0.299 ** | 0.164 | 0.073 | 0.303 ** | 0.184 | 0.196 | 0.299 ** | 0.349 ** | 0.265 * | 0.304 ** | 0.362 ** | 0.469 ** | 1.000 | |

| 15. Overall attachment to landscape characteristics | 0.362 ** | −0.288 ** | 0.596 ** | 0.534 ** | 0.637 ** | 0.606 ** | 0.660 ** | 0.494 ** | 0.775 ** | 0.613 ** | 0.599 ** | 0.613 ** | 0.729 ** | 0.553 ** | 1.000 |

| FC | TTFF | MFD | VC | MPD | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Positive Effect | −0.065 | 0.142 | 0.008 | 0.033 | −0.317 ** |

| Negative Effect | 0.143 | 0.031 | 0.016 | −0.067 | 0.139 |

| Place Attachment | −0.032 | 0.042 | 0.020 | 0.176 | −0.225 * |

| Overall Attachment to Landscape Characteristics | −0.085 | −0.039 | −0.108 | 0.255 * | −0.117 |

| Space Sequence in VR Experience | Landscape Elements on Which Gaze Was Focused (in Descending Order) | Relating Landscape Characteristics in Emotional Scale |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Water space with pavilion | Pavilion, water, shrubs, stones, arbors | Form and structure, natural-related features, material, color |

| 2. Water space by pavilion | Water, pavilion, chair, stone, arbors | Natural-related features, form and structure, sociability |

| 3. Water space inside pavilion | Arbor in the center, shrubs, pavements, water, stone | Natural-related features |

| 4. Linear waterfront space with plants | Water, shrubs | Natural-related features |

| 5. Linear waterfront space with symbols | Symbols, water, shrubs | Regionality, uniqueness, natural-related features |

| 6. Open lawn space with pavilion and symbols (far from pavilion) | Pavilion, water, symbols, arbor (ginkgo biloba with yellow leaves) | Form and structure, natural-related features, regionality, uniqueness |

| 7. Open lawn space with pavilion and symbols (close to pavilion) | Symbols, pavilion, arbors (ginkgo biloba with yellow leaves) | Uniqueness, diversity, regionality, form and structure, natural-related features, color |

| 8. Pavilion inside space with symbols (specimen exhibition wall) | Symbols of specimen exhibition wall, symbols on the lawn | Uniqueness, regionality, sociability, playability |

| 9. Semi-enclosed pavilion space with maple tree and symbols | Symbols (interactive), arbors in distance, arbors nearby (the maple) | Regionality, uniqueness, natural-related features |

| 10. Pavilion inside space with chairs | Symbols (outside pavilion), pavilion (inside structure and furniture) | Sociability, uniqueness, form and structure |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhang, R.; Duan, W.; Zheng, Z. Multimodal Quantitative Research on the Emotional Attachment Characteristics between People and the Built Environment Based on the Immersive VR Eye-Tracking Experiment. Land 2024, 13, 52. https://doi.org/10.3390/land13010052

Zhang R, Duan W, Zheng Z. Multimodal Quantitative Research on the Emotional Attachment Characteristics between People and the Built Environment Based on the Immersive VR Eye-Tracking Experiment. Land. 2024; 13(1):52. https://doi.org/10.3390/land13010052

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Ruoshi, Weiyue Duan, and Zhikai Zheng. 2024. "Multimodal Quantitative Research on the Emotional Attachment Characteristics between People and the Built Environment Based on the Immersive VR Eye-Tracking Experiment" Land 13, no. 1: 52. https://doi.org/10.3390/land13010052

APA StyleZhang, R., Duan, W., & Zheng, Z. (2024). Multimodal Quantitative Research on the Emotional Attachment Characteristics between People and the Built Environment Based on the Immersive VR Eye-Tracking Experiment. Land, 13(1), 52. https://doi.org/10.3390/land13010052