Safety Perceptions and Micro-Segregation: Exploring Gated- and Non-Gated-Community Dynamics in Quetta, Pakistan

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Literature Review

Gated and Non-Gated Communities and Their Relationship with Fear of Crime

- Residents in gated communities tend to perceive a higher sense of safety and a lower risk of crime victimization compared to those in non-gated communities.

- Individuals who experience high levels of fear related to crime often report poorer health conditions. Crime victims often report a decline in their sense of wellbeing and overall health.

- Individuals with higher socio-economic status generally experience a higher number of criminal incidents and tend to have higher levels of worry about being victims of crime.

2. Materials and Methods

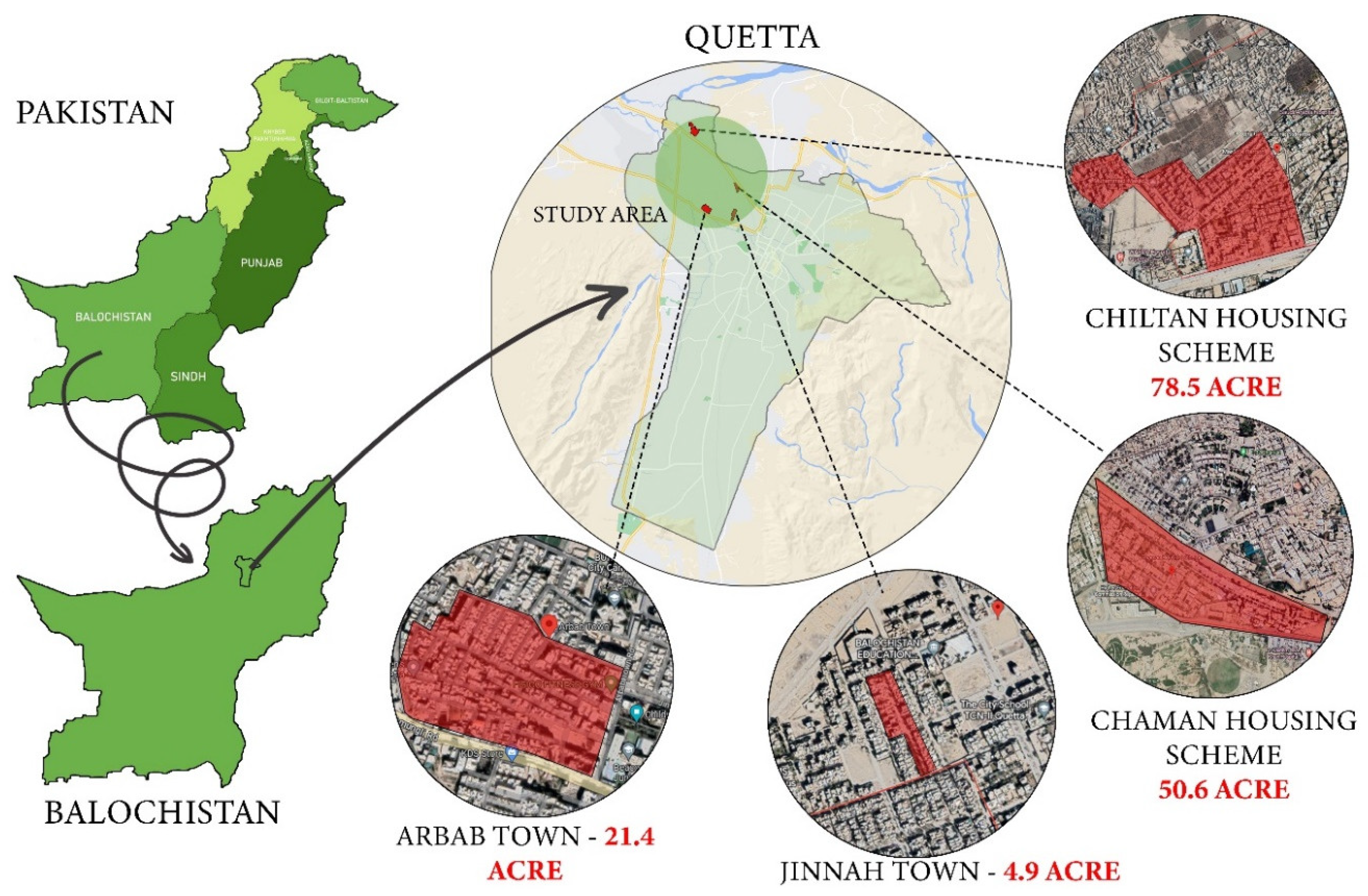

2.1. Framing the Case Study Area

2.2. Case Study 1

2.3. Case Study 2

2.4. Case Study 3

2.5. Case Study 4

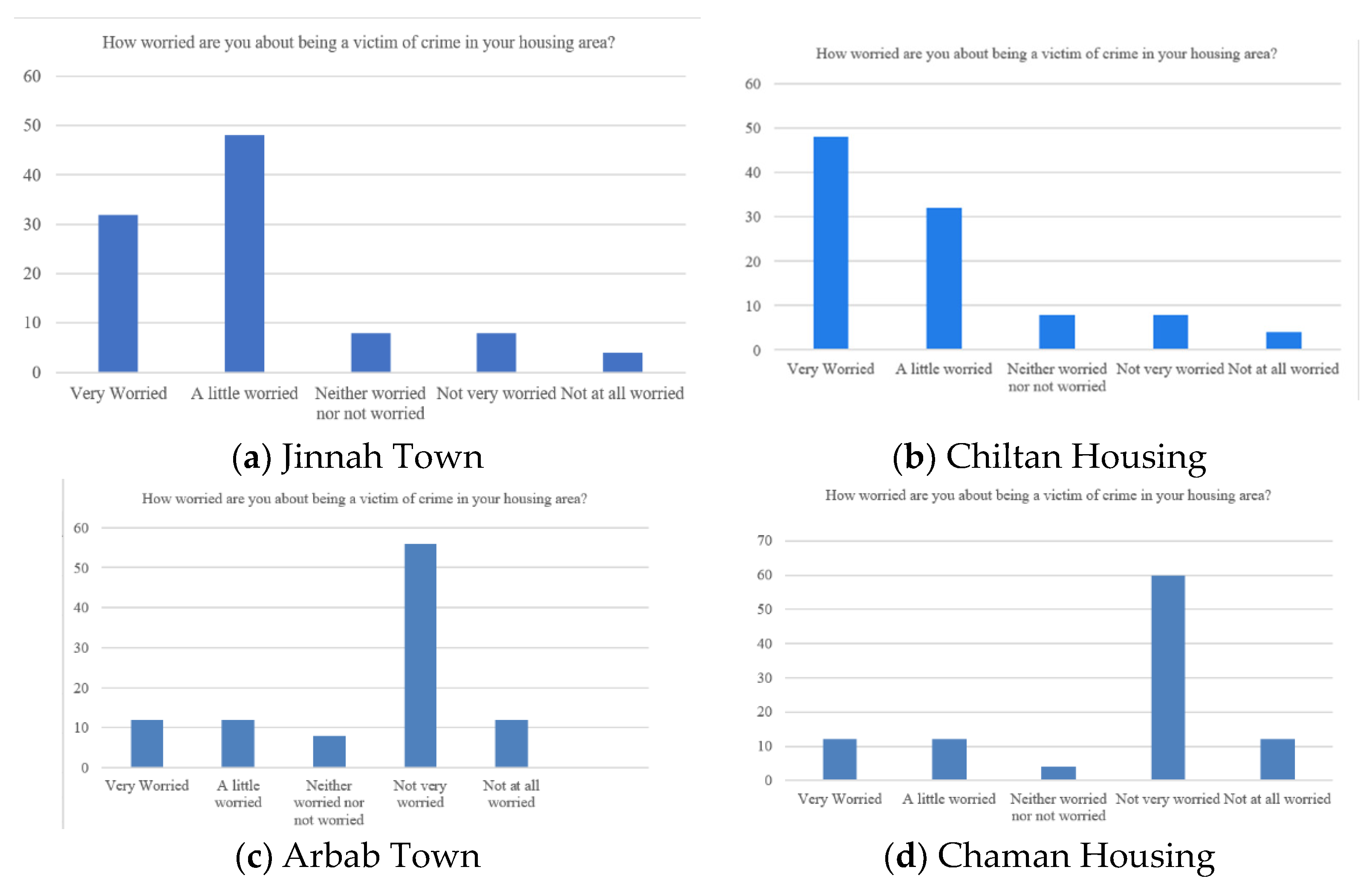

3. Results

4. Discussion of the Results

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sakip, S.R.M.; Johari, N.; Salleh, M.N.M. The Relationship between Crime Prevention through Environmental Design and Fear of Crime. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2012, 68, 628–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasar, J.L.; Jones, K.M. Landscapes of fear and stress. Environ. Behav. 1997, 29, 291–323. [Google Scholar]

- Mohit, M.A.; Abdulla, A. Residents’ crime and safety perceptions in gated and non-gated low middle income communities in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. J. Archit. Plan. Constr. Manag. 2011, 1, 71–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mrozla, T. Procedural and distributive justice: Effects on attitudes toward body-worn cameras. Int. J. Police Sci. Manag. 2021, 23, 317–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakip, S.R.M.; Johari, N.; Salleh, M.N.M. Perception of Safety in Gated and Non-Gated Neighborhoods. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2013, 85, 383–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox, K.A.; Nobles, M.R.; Piquero, A.R. Gender, crime victimization and fear of crime. Secur. J. 2009, 22, 24–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, C.L.; Zhao, J.; Lovrich, N.P.; Gaffney, M.J. Social integration, individual perceptions of collective efficacy, and fear of crime in three cities. Justice Q. 2002, 19, 537–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGarrell, E.F.; Giacomazzi, A.L.; Thurman, Q.C. Neighborhood disorder, integration, and the fear of crime. Justice Q. 1997, 14, 479–500. [Google Scholar]

- Stafford, M.; Chandola, T.; Marmot, M. Association between fear of crime and mental health and physical functioning. Am. J. Public Health 2007, 97, 2076–2081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warr, M. Fear of crime in the United States: Avenues for research and policy. Crim. Justice 2000, 4, 451–489. [Google Scholar]

- Garofalo, J. The fear of crime: Causes and consequences. J. Crim. Law Criminol. 1981, 72, 839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobs, J. “The Uses of City Neighborhoods”: From the Death and Life of Great American Cities (1961). In The Urban Sociology Reader; Routledge: London, UK, 2012; pp. 50–57. [Google Scholar]

- Breetzke, G.D.; Landman, K.; Cohn, E.G. Is it safer behind the gates? Crime and gated communities in South Africa. J. Hous. Built Environ. 2014, 29, 123–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blandy, S. Gated communities in England as a response to crime and disorder: Context, effectiveness and implications. People Place Policy Online 2007, 1, 47–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkurdi, N. Gated communities (GCS): A physical pattern of social segregation. Anthropologist 2015, 19, 229–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Low, S.M. The edge and the center: Gated communities and the discourse of urban fear. Am. Anthropol. 2001, 103, 45–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynch, M. From the punitive city to the gated community: Security and segregation across the social and penal landscape. Univ. Miami Law Rev. 2001, 56, 89. Available online: https://repository.law.miami.edu/umlr/vol56/iss1/6 (accessed on 2 October 2023).

- Wilson-Doenges, G. An exploration of sense of community and fear of crime in gated communities. Environ. Behav. 2000, 32, 597–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipman, A.; Harris, H. Fortress johannesburg. Environ. Plan. B Plan. Des. 1999, 26, 727–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blakely, E.J.; Snyder, M.G. Fortress America: Gated Communities in the United States; Brookings Institution Press: Washington, DC, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Abbas, S.; Shouping, L.; Sidra, F.; Sharif, A. Impact of Crime on Socio-Economic Development: A Study of Karachi. Malays. J. Soc. Sci. Humanit. (MJSSH) 2018, 3, 148–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sindhu, A.J. Development of Affordable Housing Framework for Low-Income Households in Pakistan. Ph.D. Thesis, Liverpool John Moores University, Liverpool, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadeem, M.; Asim, M.; Muiz, A.; Abbas, Q.; Nadeem, M. Is it a dream or reality of five million housing units construction in Pakistan? A review of house construction approaches and measures. Pak. Econ. Soc. Rev. 2020, 58, 269–296. [Google Scholar]

- Mehmood, A. Urban Pakistan. 2014. Available online: https://www.academia.edu/16445017/Urban_Pakistan_Report (accessed on 23 November 2023).

- PBS, Pakistan Bureau of Statistics. 2017. Available online: http://www.pbs.gov.pk/content/population-census (accessed on 11 August 2023).

- Qayyum, F. State, Security, and People along Urban Frontiers: Juxtapositions of Identity and Authority in Quetta. Urban Forum 2020, 31, 409–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahar, W.A.; Knapen, E.; Verbeeck, G. Methodology to determine housing characteristics in less developed areas in developing countries: A case study of Quetta, Pakistan. In Proceedings of the European Network for Housing Research (ENHR) Annual Conference, Media Print, Tirana, Albania, 4–6 September 2017; Available online: https://api.semanticscholar.org/CorpusID:115266302 (accessed on 15 September 2023).

- Gul, Y.; Sultan, Z.; Moeinaddini, M.; Ahmed Jokhio, G. Measuring the differences of neighbourhood environment and physical activity in gated and non-gated neighbourhoods in Karachi, Pakistan. J. Urban Des. 2019, 24, 494–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdullah, A.; Salleh, M.N.M.; Sakip, S.R.M. Fear of Crime in Gated and Non-gated Residential Areas. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2012, 35, 63–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grundström, K.; Lelévrier, C. Imposing ‘Enclosed Communities’? Urban Gating of Large Housing Estates in Sweden and France. Land 2023, 12, 1535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crisci, M.; Santurro, M. Micro-segregation of ethnic minorities in Rome: Highlighting specificities of national groups in micro-segregated areas. Land 2023, 12, 1870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, L.J. Gated communities: Institutionalizing social stratification. Geogr. Bull. 2013, 54, 24. [Google Scholar]

- Tarichia, T. Security Strategies Used by Gated Communities in Enhancing Residential Security: A Case Study of Kitengela Township in Kajiado County, Kenya. Master’s Thesis, University of Nairobi, Nairobi, Kenya, 2022. Available online: http://erepository.uonbi.ac.ke/handle/11295/163194 (accessed on 15 September 2023).

- Bandauko, E.; Arku, G.; Nyantakyi-Frimpong, H. A systematic review of gated communities and the challenge of urban transformation in African cities. J. Hous. Built Environ. 2022, 37, 339–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bint-e-Waheed, H.; Nadeem, O. Perception of security risk in gated and non-gated communities in Lahore, Pakistan. J. Hous. Built Environ. 2019, 35, 897–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calderón-Figueroa, F. Residential Micro-Segregation and Social Capital in Lima, Peru. Land 2024, 13, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atkinson, R.; Blandy, S.; Flint, J.; Lister, D. Gated cities of today? Barricaded residential development in England. Town Plan. Rev. 2005, 76, 401–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coy, M.; Pöhler, M. Gated communities in Latin American megacities: Case studies in Brazil and Argentina. Environ. Plan. B Plan. Des. 2002, 29, 355–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leisch, H. Gated communities in Indonesia. Cities 2002, 19, 341–350. [Google Scholar]

- Adetokunbo, I. Sense of security and production of place in gated communities: Case-studies in Lagos, Nigeria. Int. J. Prop. Sci. 2013, 3, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frias, S.; Udelsmann Rodrigues, C. Private condominiums in Luanda: More than just the safety of walls, a new way of living. Soc. Dyn. 2018, 44, 341–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabatini, F.; Salcedo, R. Gated communities and the poor in Santiago, Chile: Functional and symbolic integration in a context of aggressive capitalist colonization of lower-class areas. Hous. Policy Debate 2007, 18, 577–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pain, R. Place, social relations and the fear of crime: A review. Prog. Hum. Geogr. 2000, 24, 365–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrall, S.; Gray, E.; Jackson, J. Theorising the fear of crime: The cultural and social significance of insecurities about crime. In Experience & Expression in the Fear of Crime Working Paper; Keele University, Keele, &LSE: London, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitchen, T.; Schneider, R.H. Crime Prevention and the Built Environment; Routledge: London, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spinks, C. A New Apartheid? Urban Spatiality, (Fear of) Crime, and Segregation in Cape Town, South Africa; London School of Economics and Political Science, Development Studies Institute: London, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Minnery, J.R.; Lim, B. Measuring crime prevention through environmental design. J. Archit. Plan. Res. 2005, 22, 330–341. [Google Scholar]

- Ferraro, K.F.; Grange, R.L. The Measurement of Fear of Crime. Sociol. Inq. 1987, 57, 70–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasar, J.L.; Fisher, B. ‘Hot spots’ of fear and crime: A multi-method investigation. J. Environ. Psychol. 1993, 13, 187–206. [Google Scholar]

- Ross, C.E.; Jang, S.J. Neighborhood disorder, fear, and mistrust: The buffering role of social ties with neighbors. Am. J. Community Psychol. 2000, 28, 401–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandiani, J.A.; Banks, S.M.; Carroll, B.B.; Schlueter, M.R. Crime victims and criminal offenders among adults with serious mental illness. Psychiatr. Serv. 2007, 58, 1483–1485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Franklin, C.A.; Franklin, T.W. Predicting fear of crime: Considering differences across gender. Fem. Criminol. 2009, 4, 83–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Painter, K. The influence of street lighting improvements on crime, fear and pedestrian street use, after dark. Landsc. Urban Plan. 1996, 35, 193–201. [Google Scholar]

- Kelling, G.L.; Wilson, J.Q. Broken windows. Atl. Mon. 1982, 249, 29–38. [Google Scholar]

- LaGrange, R.L.; Ferraro, K.F.; Supancic, M. Perceived risk and fear of crime: Role of social and physical incivilities. J. Res. Crime Delinq. 1992, 29, 311–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moran, R.; Dolphin, C. The defensible space concept: Theoretical and operational explication. Environ. Behav. 1986, 18, 396–416. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, R.B.; Gottfredson, S.D.; Brower, S. Block crime and fear: Defensible space, local social ties, and territorial functioning. J. Res. Crime Delinq. 1984, 21, 303–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weidemann, S.; Anderson, J.R.; Butterfield, D.I.; O’Donnell, P.M. Residents’ perceptions of satisfaction and safety: A basis for change in multifamily housing. Environ. Behav. 1982, 14, 695–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilcox, P.; Quisenberry, N.; Jones, S. The built environment and community crime risk interpretation. J. Res. Crime Delinq. 2003, 40, 322–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yates, A.; Ceccato, V. Individual and spatial dimensions of women’s fear of crime: A Scandinavian study case. Int. J. Comp. Appl. Crim. Justice 2020, 44, 265–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunson, L.; Kuo, F.E.; Sullivan, W.C. Resident appropriation of defensible space in public housing: Implications for safety and community. Environ. Behav. 2001, 33, 626–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jalili, M.; Einifar, A.; Madani, R.; Judd, B. The effects of residential communities’ physical boundaries on residents’ perception of fear of crime: Comparison between gated, perceived gated, and non-gated communities in Ekbatan neighborhood, Tehran. J. Iran. Archit. Urban. 2021, 12, 189–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, K.; Glanz, L. Fear of crime among the South African public. S. Afr. J. Sociol. 1989, 20, 53–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearson, A.L.; Breetzke, G.D. The association between the fear of crime, and mental and physical wellbeing in New Zealand. Soc. Indic. Res. 2014, 119, 281–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S. The Gated Community: Residents’ Crime Experience and Perception of Safety behind Gates and Fences in the Urban Area. Ph.D. Thesis, ProQuest Information and Learning Company, Ann Arbor, MI, USA, 2006. Available online: https://api.semanticscholar.org/CorpusID:112737698 (accessed on 15 September 2023).

- Newman, O. National Institute of Law Enforcement and Criminal Justice. In Law Enforcement Assistance Administration; National Institute of Law Enforcement and Criminal Justice: Washington, DC, USA, 1973; p. 2700-00161. [Google Scholar]

- Addington, L.A.; Rennison, C.M. Keeping the Barbarians Outside the Gate? Comparing Burglary Victimization in Gated and Non-Gated Communities. Justice Q. 2015, 32, 168–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pow, C.P. Securing the’civilised’enclaves: Gated communities and the moral geographies of exclusion in (post-) socialist shanghai. Urban Stud. 2007, 44, 1539–1558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratcliffe, J. Suburb Boundaries and Residential Burglars. 2003. Available online: http://www.aic.gov.au/publications/tandi/ti246.pdf (accessed on 20 November 2023).

- Dawood, F.; Akhtar, M.M.; Ehsan, M. Evaluating urbanization impact on stressed aquifer of Quetta Valley, Pakistan. Desalin. Water Treat. 2021, 222, 103–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.S.; Khan, S.D.; Kakar, D.M. Land subsidence and declining water resources in Quetta Valley, Pakistan. Environ. Earth Sci. 2013, 70, 2719–2727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehman, A. Quetta Shura revival of Taliban in Afghanistan. Pak. J. Int. Aff. 2022, 5, 722–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gul, Y.; Sultan, Z.; Jokhio, G.A. The association between the perception of crime and walking in gated and non-gated neighbourhoods of Asian developing countries. Heliyon 2018, 4, e00715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gul, Y.; Sultan, Z.; Johar, F. Effects of neighborhood’s built environment on physical activities in gated communities: A review. Int. J. Built Environ. Sustain. 2016, 21, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Areas/Spaces and Amenity Details | Chaman Housing: Non-Gated Housing Scheme | Arbab Town: Non-Gated Housing Scheme | Chiltan Housing: Gated Housing Scheme | Jinnah Town: Gated Housing Scheme | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Public Spaces | Commercial activities | Shops/Tea stalls and tea shops | 8 | 14 | 14 | 6 |

| Hotels/ Restaurants | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | ||

| Grocery stores/general store | 1 | 11 | 16 | 11 | ||

| Supermarts | 1 | 2 | 2 | 3 | ||

| Snooker and Gaming points | 0 | 3 | 1 | 4 | ||

| Bank | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | ||

| Tailer shops | 0 | 3 | 2 | 0 | ||

| Medical stores | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0 | ||

| Community hall | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | ||

| Commercial buildings with shops on ground floor | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Mosque | 1 | 2 | 2 | Grand Mosque (1) | ||

| Parks | Community Park (1) | None | 3 parks | None | ||

| Auditorium and cinema | None | None | None | None | ||

| No. of houses | 200 houses | 265 houses | 665 houses | 83 houses | ||

| Total population | 3350 people | 550 people | 5400 people | 415 people | ||

| Case Studies | Chaman Housing | Arbab Town | Chiltan Housing | Jinnah Town | Total | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-Gated | Non-Gated | Gated | Gated | |||||

| No. of Respondents | 25 | 25 | 25 | 25 | 100 | |||

| Respondents (%) | Total (%) | Mean | Std. Dev. | |||||

| Age | 16–24 | 4% | 60% | 24% | 36% | 33% | 2.39 | 1.197 |

| 25–34 | 12% | 16% | 28% | 20% | 19% | |||

| 35–44 | 36% | 24% | 16% | 28% | 26% | |||

| 45–54 | 44% | 0% | 8% | 8% | 20% | |||

| 55–64 | 4% | 0% | 4% | 0% | 2% | |||

| Marital Status | Single | 4% | 16% | 20% | 0% | 10% | 1.97 | 0.502 |

| Married | 88% | 76% | 80% | 100% | 86% | |||

| Divorced | 4% | 4% | 0% | 0% | 2% | |||

| Widowed | 4% | - | 0% | 0% | 1% | |||

| Other | - | 4% | 0% | 0% | 1% | |||

| Economic Activities | Employed | 24% | 68% | 0% | 36% | 34% | 2.49 | 1.259 |

| Unemployed | 0% | 16% | 8% | 20% | 11% | |||

| Self-employed | 60% | 4% | 44% | 16% | 31% | |||

| Student | 8% | 28% | 40% | 24% | 20% | |||

| Retired | 0% | 4% | 8% | 4% | 4% | |||

| Income Status | ≤20,000 | 0% | 0% | 16% | 0% | 4% | 4.36 | 1.345 |

| 20–30 k | 4% | 20% | 8% | 0% | 8% | |||

| 30–40 k | 4% | 28% | 4% | 0% | 11% | |||

| 40–50 k | 4% | 32% | 8% | 8% | 16% | |||

| >50 k | 84% | 16% | 40% | 84% | 52% | |||

| Refused | 4% | 4% | 24% | 8% | 10% | |||

| Other | 12% | 8% | 16% | 8% | 11% | |||

| Safety Perception and Crime Victimization | Fear of Crime on Health and Well-Being | Socio-Eco. Status | Employment Status | Housing Schemes | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A1 | A2 | A3 | A4 | A5 | A6 | A7 | A8 | n = 100 | ||

| A1 | Pearson Correlation | −0.371 ** | −0.223 | −0.675 ** | 0.060 | 0.092 | 0.171 | −0.314 * | Gated Housing schemes | |

| Significance (2-tailed) | 0.008 | 0.120 | 0.000 | 0.681 | 0.525 | 0.234 | 0.026 | |||

| A2 | Pearson Correlation | −0.371 ** | 0.454 ** | 0.582 ** | 0.072 | −0.080 | −0.215 | 0.087 | ||

| Significance (2-tailed) | 0.008 | 0.001 | 0.000 | 0.618 | 0.583 | 0.134 | 0.547 | |||

| A1 | Pearson Correlation | −0.143 | −0.071 | 0.239 | −0.093 | −0.202 | −0.188 | −0.342 * | Non-Gated Housing schemes | |

| Significance (2-tailed) | 0.323 | 0.625 | 0.095 | 0.520 | 0.159 | 0.191 | 0.015 | |||

| A2 | Pearson Correlation | −0.143 | −0.034 | 0.280 * | 0.123 | 0.399 ** | −0.072 | 0.063 | ||

| Significance (2-tailed) | 0.323 | 0.817 | 0.049 | 0.396 | 0.004 | 0.621 | 0.664 | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Iqbal, A.; Shaukat, T.; Nazir, H. Safety Perceptions and Micro-Segregation: Exploring Gated- and Non-Gated-Community Dynamics in Quetta, Pakistan. Land 2024, 13, 727. https://doi.org/10.3390/land13060727

Iqbal A, Shaukat T, Nazir H. Safety Perceptions and Micro-Segregation: Exploring Gated- and Non-Gated-Community Dynamics in Quetta, Pakistan. Land. 2024; 13(6):727. https://doi.org/10.3390/land13060727

Chicago/Turabian StyleIqbal, Asifa, Tahira Shaukat, and Humaira Nazir. 2024. "Safety Perceptions and Micro-Segregation: Exploring Gated- and Non-Gated-Community Dynamics in Quetta, Pakistan" Land 13, no. 6: 727. https://doi.org/10.3390/land13060727