A Contribution to the Integration of International, National and Local Cultural Heritage Protection in Planning Methodology: A Case Study of the Djerdap Area

Abstract

:1. Introduction

Theoretical Background

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Interrelating of the Principles, Theoretical Concepts and Practical Tools

2.2. Case Study of SPSP Djerdap

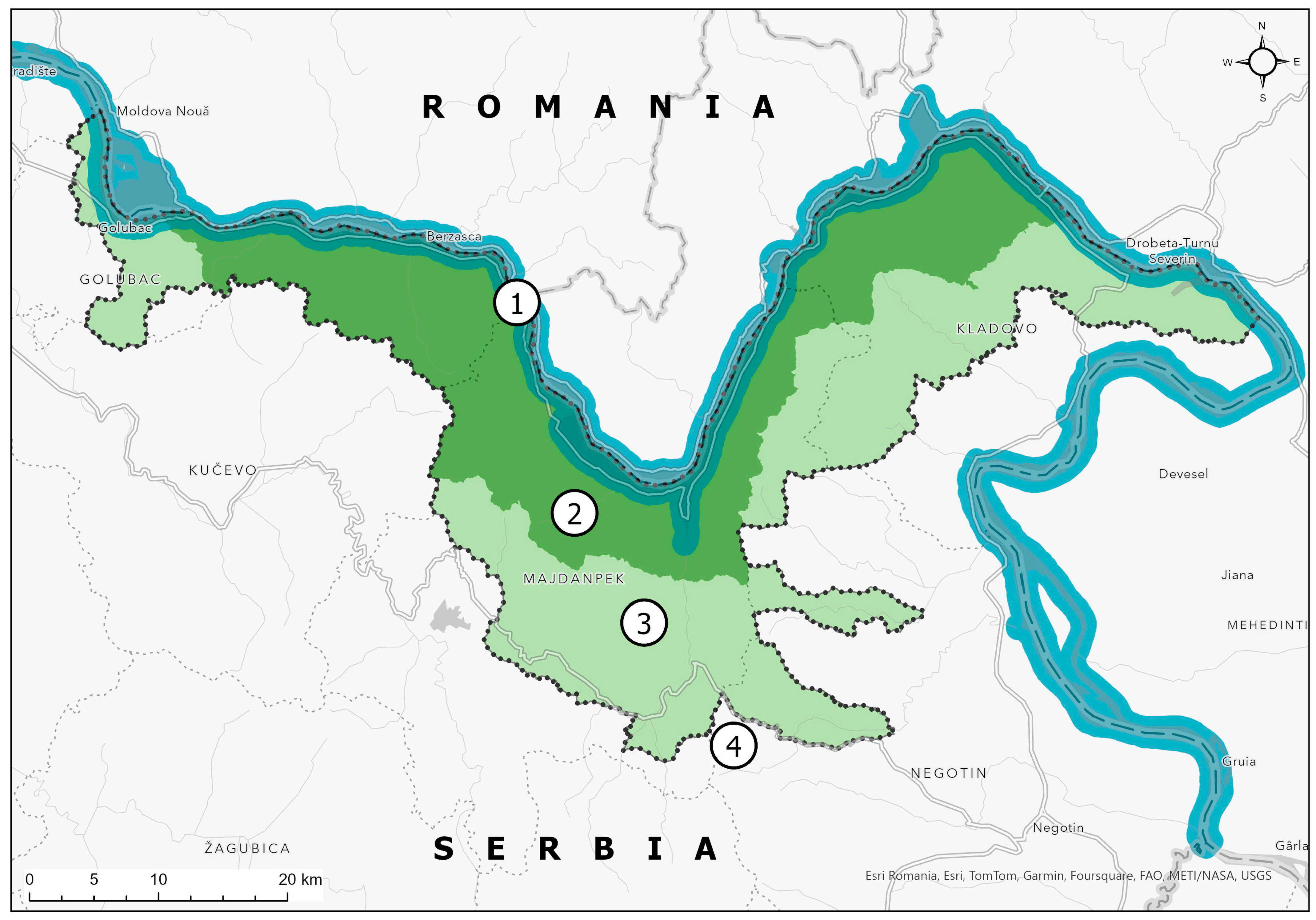

- Djerdap National Park (covering around 64,000 hectares) was established in 1974. It includes the spatial unit of Djerdap Gorge and the natural area along the gorge, with exceptional cultural-historical values, significant natural ecosystems of exceptional rarity and value, original flora and fauna specimens, and well-preserved forests of natural composition and exceptional appearance.

- Djerdap Geopark (covering approximately 133,000 hectares) was the first area from Serbia inscribed on the UNESCO World Geoparks List (Global Geoparks Network) in 2020. While not a protected area, the Geopark represents a specific concentration of geosites; a number of geological heritage sites are arranged, mostly within other protected areas, in the form of geological trails and individual structural profiles;

- The Roman Empire border is the Danube Limes area, included in the preliminary list of the Republic of Serbia for inclusion in the international serial nomination, the Roman Empire border (from the Black Forest area (Schwarzwald) to the Black Sea).

3. Findings: Contribution of the Applied Planning Methodology to Integrating Multilevel Principles and Actors into Plan Formation

3.1. Relevant Documents in Serbia for the Treatment of the Cultural Heritage at the Level of the Spatial Entites and Its Treatment in the Planning Documents

3.2. Legally Binding Elements in Planning: Content and Procedure

3.3. The Case Study of the SPSP Djerdap: Introducing of the Non-Binding Planning Concepts, Elements and Tools within the Planning Methodology

- Protecting wider spatial entites containing cultural assets and in doing so overcoming solely administrative boundaries;

- Making heritage visible and available to the wider community;

- Defining cultural areas and cultural routes at the international, national and local levels along with the management plans for their sustainable use and development;

- Further elaboration of nomination dossiers for WHC.

- Preparation and regular adoption of management plans for protected areas, in the manner and with the content determined by law and declaration acts;

- Tourism-development programs;

- Connection between geological and other territorial heritage, i.e., natural biotic, cultural and intangible properties.

- Building capacities to participate in future partnership strategies at national and international levels;

- Education strategy in partnership with other global geoparks;

- Activities to facilitate the mitigation of natural hazards and climate change in schools and local communities, etc.

4. Discussion

- Recognition of responsibilities at different decision-making levels and their inclusion in the plan’s implementation measures;

- Recognition of cultural heritage that is not institutionally protected but represents an important spatial resource and must be treated integrally with other spatial resources with the obligation of synergistic action with compatible sectors (nature protection, tourism, urbanization) and avoiding conflicts (industry, mining, etc.);

- Linking spatial scopes from different documents governing the said area, which give recommendations that are directed towards administrative units but which are not based on administrative divisions in a spatial sense.

5. Conclusions

6. Patents

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- UNESCO. Recommendation on the Historic Urban Landscape; UNESCO: Vienna, Austria, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Council of Europe. Territorial Agenda of the European Union 2020: Towards an Inclusive, Smart and Sustainable Europe of Diverse Regions; Council of Europe: Gödöllő, Hungary, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Guzmán, P.C.; Pereira Roders, A.R.; Colenbrander, B.J.F. Measuring links between cultural heritage management and sustainable urban development: An overview of global monitoring tools. Cities 2017, 60 Pt A, 192–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stegmeijer, E.; Veldpaus, L.; Janssen, J. Introduction to a research agenda for heritage planning: The state of heritage planning in Europe. In A Research Agenda for Heritage Planning, Perspectives from Europe; Veldpaus, L., Stegmaijer, E., Eds.; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK; Northampton, MA, USA, 2021; pp. 3–21. [Google Scholar]

- Veldpaus, L. Historic Urban Landscapes: Framing the Integration of Urban and Heritage Planning in Multilevel Governance. Ph.D. Thesis, Technische Universiteit Eindhoven, Eindhoven, The Netherlands, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- NARS—National Assembly of the Republic of Serbia. Law on the Planning System of Serbia. In Official Gazette RS, No. 30/2018; National Assembly of the Republic of Serbia: Belgrade, Serbia, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- NARS—National Assembly of the Republic of Serbia. Strategy of the sustainable urban development of the Republic of Serbia. In Official Gazette RS, No. 47/2019; National Assembly of the Republic of Serbia: Belgrade, Serbia, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Group of Institutions. PPRS 2021–2035: Spatial Plan of the Republic of Serbia, 2021–2035. (In Process of Adoption); National Assembly of the Republic of Serbia: Belgrade, Serbia, 2021.

- Čolić, N.; Nedović-Budić, Z. Public interest as a basis for planning standards in urban development: State-socialist and post-socialist cases in Serbia. J. Plan. Educ. Res. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhodes, R.A.W. Understanding Governance: Ten Years On. Organ. Stud. 2007, 28, 1243–1264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borraz, O.; Galès, P.L. Urban governance in Europe: The government of what? Pôle Sud 2010, 1, 137–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyden, G. Making the State Responsive: Rethinking Governance Theory and Practice. In Making the State Responsive: Experience with Democratic Governance Assessments; Hyden, G., Samuel, J., Eds.; UNDP: New York, NY, USA, 2011; pp. 5–28. [Google Scholar]

- Jessop, B. Territory, Politics, Governance, and Multispatial Metagovernance. Territ. Politics Gov. 2016, 4, 8–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Čolić, R.; Milić, Đ.; Petrić, J.; Čolić, N. Institutional capacity development within the national urban policy formation process—Participants’ views. Environ. Plan. C Politics Space 2022, 40, 69–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commision. Urban Agenda for the EU ‘Pact of Amsterdam’; European Commision: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Tasan-Kok, T.; Vranken, J. Handbook for Multilevel Urban Governance in Europe: Analysing Participatory Instruments for an Integrated Urban Development; EUKN: The Hague, The Netherlands, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Mäkinen, K. Scales of participation and multi-scalar citizenship in EU participatory governance. Environ. Plan. C Politics Space 2021, 39, 1011–1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fioretti, C.; Pertoldi, M.; Busti, M.; Van Heerden, S. Handbook of Sustainable Urban Development Strategies; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Healey, P. Transforming Governance: Challenges of Institutional Adaptation and a New Politics of Space. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2006, 14, 299–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rzasa, K.; Ogryzek, M.; Kulawiak, M. Cultural Heritage in Spatial Planning. In 2016 Baltic Geodetic Congress (BGC Geomatics); IEEE: Gdansk, Poland, 2016; pp. 85–89. [Google Scholar]

- Niković, A.; Manić, B. The challenges of planning in the field of cultural heritage in Serbia. Facta Univ. Ser. Archit. Civ. Eng. 2018, XVI, 449–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niković, A.; Manić, B. Building a Common Platform: Integrative and Territorial Approach to Planning Cultural Heritage within the Framework of the Spatial Plan of the Republic of Serbia 2021–2035. In REAL CORP 2020: Shaping Urban Change. Livable City Regions for the 21st Century-Aachen, Germany; Schrenk, M., Popovich, V.V., Zeile, P., Elisei, P., Beyer, C., Ryser, J., Reicher, C., Çelik, C., Eds.; CORP—Competence Center of Urban and Regional Planning: Vienna, Austria, 2020; pp. 107–115. [Google Scholar]

- Niković, A.; Manić, B. Prostorna dimenzija zaštite kulturnog nasleđa u Srbiji: Prilog unapređenju institucionalnog i pravnog okvira. In Zbornik Radova: XI Naučnostručna Konferencija “Graditeljsko Nasleđe i Urbanizam”; Mrlješ, R., Ed.; Zavod za Zaštitu Spomenika Kulture Grada Beograda: Beograd, Srbija, 2021; pp. 346–359. [Google Scholar]

- Nadin, V.; Stead, D.; Dąbrowski, M.; Fernandez Maldonado, A.M. Integrated, adaptive and participatory spatial planning: Trends across Europe. Reg. Stud. 2021, 55, 791–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dabrowski, M.M. Multi-Level and Multi-Actor Governance: Why it matters for spatial planning. In Teaching, Learning & Researching Spatial Planning; Rocco, R., Bracken, G., Newton, C., Dabrowski, M., Eds.; TU Delft OPEN Publishing: Delft, The Netherlands, 2022; pp. 56–67. [Google Scholar]

- NARS—National Assembly of the Republic of Serbia. Law on Planning and Construction. In Official Gazette RS, No. 72/09; National Assembly of the Republic of Serbia: Belgrade, Serbia, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Stefanović, N.; Danilović Hristić, N.; Srnić, D. A methodological framework for integrated planning in the protection and development of natural resource areas in Serbia—A case study of spatial plans for special purpose areas for protected natural areas. Spatium 2018, 40, 25–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NARS—National Assembly of the Republic of Serbia. Spatial Plan for the Special Purpose Area of the Djerdap National. In Official Gazette RS, No. 117/2022; National Assembly of the Republic of Serbia: Belgrade, Serbia, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- ZZPS-Zavod za Zaštitu Prirode Srbije. Nacionalni Park “Đerdap”. 2023. Available online: https://zzps.rs/nacionalni-park-djerdap/ (accessed on 2 March 2021).

- UNESCO. Djerdap UNESCO Global Geopark. 2021. Available online: https://en.unesco.org/global-geoparks/djerdap (accessed on 2 March 2021).

- Basarić, J. Kulturno nasleđe kao turistički potencijal Donjeg Podunavlja u Srbiji. Arhit. Urban. 2023, 56, 46–57. [Google Scholar]

- Nikolić, M.; Šćekić, J. Kulturno i prirodno nasleđe Đerdapa—Izgubljena istorija ili potencijal za održivi razvoj. Arhit. Urban. 2022, 55, 24–37. [Google Scholar]

- Dobričić, M.; Sekulić, G.; Josimović, B. Procena kulturno-istorijskih i drugih ekosistemskih vrednosti Nacionalnog parka Đerdap. Arhit. Urban. 2022, 54, 5–14. [Google Scholar]

- Maran Stevanović, A. Activities on the establishment of Djerdap geopark (Serbia) and candidature of the area to the UNESCO Global Geopark Network. Bull. Nat. Hist. Mus. 2017, 10, 7–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geopark Djerdap. 2020. Available online: https://geoparkdjerdap.rs/?pismo=lat (accessed on 2 March 2021).

- Rabrenović, D.; Manojlović, S.; Radaković, N.; Milovanović, Z.; Drndarević, D.; Milojković, D.; Maran Stevanović, A.; Ćalić, J.; Marinčić, S.; Srećković-Batoćanin, D.; et al. Application Dossier for Membership in Unesco Global Geoparks Network; NP Djerdap: Donji Milanovac, Serbia, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Viminacium. Danube Limes Brand/Dunavski Limes Kao Brend. 2024. Available online: http://viminacium.org.rs/en/projekti/danube-limes-brand/ (accessed on 20 March 2021).

- RZZZSK—Republički Zavod za Zaštitu Spomenika Kulture. Rimski Limes u Srbiji na Preliminarnoj Listi Svetske Baštine. 2024. Available online: https://www.heritage.gov.rs/latinica (accessed on 2 March 2021).

- UNESCO WHC (1992–2024). Frontiers of the Roman Empire—The Danube Limes (Serbia). 2024. Available online: https://whc.unesco.org/en/tentativelists/6475/ (accessed on 20 March 2021).

- UNESCO WHC (1992–2024). The World Heritage Convention. 2024. Available online: https://whc.unesco.org/en/convention/ (accessed on 20 March 2021).

- UNESCO (1992–2024). Upper German Raetian Limes Management Plan 2019–2023. 2024. Available online: https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/430/documents/ (accessed on 20 March 2021).

- UNESCO (1992–2024). The Operational Guidelines for the Implementation of the World Heritage Convention. 2024. Available online: https://whc.unesco.org/en/guidelines/ (accessed on 20 March 2021).

- Nacionalni Park Djerdap. 2020. Available online: https://npdjerdap.rs/?pismo=lat (accessed on 2 March 2021).

- NARS—National Assembly of the Republic of Serbia. Law on the National Parks. In Official Gazette RS, No. 84/2015; National Assembly of the Republic of Serbia: Belgrade, Serbia, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- RZZZSK-Republički Zavod za Zaštitu Spomenika Kulture. Centralni Registar NKD [Central Catalogue of IMP-Immovable Cultural Property]. 2024. Available online: https://heritage.gov.rs/english/nepokretna_kulturna_dobra.php (accessed on 12 December 2023).

- NARS—National Assembly of the Republic of Serbia. Spatial Plan for the Special Purpose Area of the Djerdap National. In Official Gazette RS, No. 43/2013; National Assembly of the Republic of Serbia: Belgrade, Serbia, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- NARS—National Assembly of the Republic of Serbia. Cultural Heritage Law. In Official Gazette RS, No. 129/21; National Assembly of the Republic of Serbia: Belgrade, Serbia, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Siguencia, M. Planning and heritage integration in multilevel governance: Cuenca, Ecuador. In The Future of the Past: Paths towards Participatory Governance for Cultural Heritage, 1st ed.; Garcia, G., Vandesande, A., Cardoso, F., Van Balen, K., Eds.; CRC Press: London, UK, 2021; pp. 101–108. [Google Scholar]

- Tarrafa Silva, A.; Pereira Roders, A.; Cunha Ferreira, T.; Nevzgodin, I. Critical Analysis of Policy Integration Degrees between Heritage Conservation and Spatial Planning in Amsterdam and Ballarat. Land 2023, 12, 1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Council of Europe. The European Landscape Convention; Council of Europe: Florence, KY, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- RS-Republika Srbija Ministarstvo Poljoprivrede i Zaštite životne Sredine; Ministarstvo Kulturne i Informisanja; SIPU International AB; PROFID. Predlog Akcionog Plana za Implementaciju Evropske Konvencije o Predelu u Srbiji; National Assembly of the Republic of Serbia: Belgrade, Serbia, 2014.

- Crnčević, T.; Milijić, S.; Bakić, O. Prilog razvoju metodološkog pristupa planiranja predela u Republici Srbiji na primeru nacionalnog parka Djerdap. Arhit. Urban. 2012, 35, 22–33. [Google Scholar]

- Maksin Mićić, M. Some problems of integrating the landscape planning into the spatial and environmental planning in Serbia. Spatium 2003, 9, 28–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maksin, M. Planning system for sustainable territorial development in Serbia. Int. J. Environ. Sustain. Dev. 2014, 13, 296–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazarević Bajec, N. Rational or collaborative model of urban planning in Serbia: Institutional limitations. Serbian Archit. J. 2009, 1, 81–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vujošević, M. Collapse of strategic thinking, research and governance in Serbia and possible role of the Spatial Plan of the Republic of Serbia in its renewal. Spatium 2010, 23, 22–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perić, A. The evolution of planning thought in Serbia: Can planning be ‘resilient’ to the transitional challenges? In History-Urbanism-Resilience—Proceedings of the 17th International Planning History Society Conference; Hein, C., Ed.; TU Delft Open: Delft, The Netherlands, 2016; Volume 7, pp. 181–193. [Google Scholar]

- Albrechts, L. Strategic (spatial) planning reexamined. Environ. Plan. B Plan. Des. 2004, 31, 743–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marić, I.; Niković, A.; Manić, B. Kulturno nasleđe, prirodne vrednosti i novi programi u funkciji razvoja turizma ruralnih područja. In Održivi Razvoj Banjskih i Turističkih Naselja u Srbiji; Pucar, M., Josimović, B., Eds.; IAUS: Beograd, Srbija, 2010; pp. 159–184. [Google Scholar]

- Manić, B.; Krunić, N.; Niković, A. Izazovi neposrednog sprovođenja strateških planskih dokumenata—Planovi jedinica lokalne samouprave sa uređajnim osnovama. In Letnja Škola Urbanizma (19; 2023; Vrnjačka Banja); Jevtić, A., Drašković, B., Eds.; Udruženje Urbanista Srbije: Beograd, Srbija, 2023; pp. 3–12. [Google Scholar]

- Čolić, N.; Dželebdžić, O. Beyond formality: A contribution towards revising the participatory planning practice in Serbia. Spatium 2018, 39, 17–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- VOICE-Vojvođanski Istraživačko-Analitički Centar. Nacionalni Parkovi i Dalje bez Stručnog Saveta i Saveta Korisnika [National Parks Still without Expert Advisory Body and User Advisory Body]. 2018. Available online: https://voice.org.rs/nacionalni-parkovi-i-dalje-bez-strucnog-saveta-i-saveta-korisnika/ (accessed on 15 December 2022).

- Marcu, F.; Cupcea, G.; Dogărel, Ş. ISTER—ConnectIng hiSTorical Danube rEgions Roman Routes. INTERREG Danube Transnational Program. 2022. Available online: https://www.interreg-danube.eu/approved-projects/ister (accessed on 27 March 2024).

- Healey, P. Collaborative planning in perspective. Plan. Theory 2003, 2, 101–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forester, J. On the evolution of a critical pragmatism. In Encounters in Planning Thought, 1st ed.; Haselsberger, B., Ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2017; pp. 298–314. [Google Scholar]

- Čolić, N.; Dželebdžić, O.; Čolić, R. Building on Recent Experiences and Participatory Planning in Serbia: Toward a New Normal. In The ‘New Normal’ in Planning, Governance and Participation: Transforming Urban Governance in a Post-Pandemic World; Lissandrello, E., Sørensen, J., Olesen, K., Nedergård Steffansen, R., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 41–56. [Google Scholar]

| The Key Principles of Improved Planning Methodology | Connected Theoretical Concepts | Connected Practical Concepts and Tools |

|---|---|---|

| Territorial approach | Multilevel governance:

| Specific and context sensitive policy integration Citizen engagement |

| Integrated approach | Holistic strategies and coordinated actions of all participants | |

| Digitalization | Shared databases; mapping Visualisation |

| Status | Documents/Links | Management Institutions | Goals/Expected Effects | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| International level | UNESCO Global Geopark (2020) [35,36] |

|

| Holistic concept of protection, education and sustainable development. |

| World Heritage Centre, tentative list (2020) [37,38,39,40,41,42] |

|

| The process of increasing the public awareness; protection and care, research and presentation; development possibilities; planning guidelines. | |

| National level | National Park (1974) [43,44] |

|

| Preservation, protection, and enhancement of cultural-historical heritage and geological heritage objects of Djerdap National Park. |

| Immovable cultural properties—registered and categorized [45,46,47] |

|

| Protection and preserving of CH through: covering, collecting, researching, documenting, studying, evaluating, presenting, interpreting, using and managing cultural heritage. | |

| Local level | Immovable cultural properties—identified, recorded and other (identified through field work and alternative sources) |

|

| Protection of all valuable elements of the physical environment regardless of their institutional protection status; valorization of the context through additional research in the field; communication and collaboration between stakeholders, especially planners, conservationists and communities. |

| The Document Title | Adopted by UNESCO/COE | Ratified by RS |

|---|---|---|

| Convention Concerning the Protection of the World Cultural and Natural Heritage | 1972 | 1974 |

| Convention for the Protection of the Architectural Heritage of Europe-Granada | 1985 | 1991 |

| European Convention on the Protection of the Archaeological Heritage | 1992 | 2007 |

| Convention on the Value of Cultural Heritage for Society | 2005 | 2010 |

| European Landscape Convention | 2000 | 2011 |

| Legally Binding | |

|---|---|

| Content | (1) Determing the boundaries according to the principle of administrative territorial division; (2) Textual part (SWOT analysis; Goals and principles of spatial development; Development concepts by sectors/disciplines); (3) Graphic part/maps (Special purpose of space; Settlements’ network and infrastrucutre system; Natural resources, protection of life environment, nature and cultural assets; Implementation) |

| Procedure | (1) The Decision on the plan elaboration; (2) Early public consultations; (3) Acquiring conditions and data; (4) Preparing the draft plan; (5) Professional control: check of the compatibilty with law, the documents in force, feasibility; (6) Public consultations of the draft plan; (7) The commision conclusion; (8) Delivering the plan; (9) Publishing and archiving the plan. |

| Territorial approach | Horizontal integration of the areas of SPSP 2013, Geopark and National Park Djerdap; Merging admistrative boundaries in recognizing spatial entities that contains cultural and natural heritage. |

| Integrated approach | Identification of all registered and non-registered cultural heritage elements; Vertical integration of all levels of governance from supranational, national and local levels; Horizontal integration of all sectors and disciplines involved and conflict mitigation; Multiactor involvment of local communities and associations in the decision making process. |

| Digitalization | Producing the tables of integrated elements of cultural heritage and shared database in GIS; Maps of spatial distribution of cultural heritage ovelapped with other sectors of spatial protection (nature, tourism and other resources of sustainalable development). |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Niković, A.; Manić, B.; Čolić Marković, N.; Krunić, N. A Contribution to the Integration of International, National and Local Cultural Heritage Protection in Planning Methodology: A Case Study of the Djerdap Area. Land 2024, 13, 1026. https://doi.org/10.3390/land13071026

Niković A, Manić B, Čolić Marković N, Krunić N. A Contribution to the Integration of International, National and Local Cultural Heritage Protection in Planning Methodology: A Case Study of the Djerdap Area. Land. 2024; 13(7):1026. https://doi.org/10.3390/land13071026

Chicago/Turabian StyleNiković, Ana, Božidar Manić, Nataša Čolić Marković, and Nikola Krunić. 2024. "A Contribution to the Integration of International, National and Local Cultural Heritage Protection in Planning Methodology: A Case Study of the Djerdap Area" Land 13, no. 7: 1026. https://doi.org/10.3390/land13071026