Abstract

China’s rural areas have long been backward in development, and many villages have completed poverty alleviation with the help of the government. Facing the requirements of sustainable development, it is necessary to change the development path, continuously increase social capital, and effectively connect with government investment resources. The existing research and practice mostly construct the strategy of social capital from the inside of the village, lacking interaction with the superior government. This paper argues for the method of planners’ intervention. The advantage is that it links the power of government and villagers, creates a perceptible, experiential, valuable material environment, and promotes collective action. Through this process, the knowledge interaction and social relations in the village can be improved. The purpose of this paper is to study how participatory planning affects the content and mechanism of this process mentioned above. Taking Hongtang village as a case study, we analyze the in-depth changes that participatory planning has brought to the rural space and social level. In the participatory planning practice of Hongtang village, college rural planners took a small vegetable garden as the breakthrough point to stimulate villagers’ participation. In the process of the upgrade, planners evolved the interaction between the village committee and villagers in the path of IMEE, which is “Intervene, Motivate, Enable, Empower”. Moreover, planners always maintained contact with the higher-level government. Through the upgrade of small vegetable gardens, the villagers’ initiative was brought into practice, the social capital was fully explored, and an effective link with the government’s resource allocation was realized.

1. Introduction

Since the start of poverty alleviation, the Chinese government has devoted a lot of resources to rural areas and achieved remarkable effectiveness [1,2]. However, during the period of poverty alleviation, the government generally adopted the method of allocating resources completely by itself. Although it can concentrate on improving the countryside quickly, there is a lack of endogenous development momentum in villages, resulting in the risk of returning to poverty in rural areas [3,4]. Determining how to cultivate the social capital of rural areas and effectively connect with the allocation of government resources is an urgent problem to be solved [5,6].

Social capital is an indispensable resource to promote rural collective action. Since the 1970s, it has been part of the field of sociology, first introduced by French sociologist Bourdieu who gave a systematic explanation [7]. Scholars generally believe that social capital can promote coordinated action between villages and improve the efficiency of resource allocation by establishing mutually beneficial and trusted social norms and relationship networks [8]. Social capital provides an important breakthrough point for the establishment of sustainable rural development. Many scholars have paid attention to the significance of rural social capital, but most research focuses on the connotation or measurement of social capital and there are few studies on how to explore practical strategies, with the latter mostly limited to internal strategies of the countryside, lacking discussion of how to connect with external forces such as the government.

From the perspective of planners, we will take rural participatory planning as a way to build social capital with space as the breakthrough point, forming a perceptible, experiential, and valuable material environment; it encourages villagers to collaborate in interaction, improves villagers’ social relations, and enhances rural social capital. Planning is a kind of public policy that involves the rational allocation of government resources. Therefore, in rural planning, it is necessary to promote the formation of benign interactions among villagers, village committees, the superior government, and planners in order to build social capital and form an endogenous and sustainable driving force for rural development.

We mainly adopt the research methods of literature research and participatory observation. The former is mainly applied to the theoretical part and the latter is mainly applied to the case part. This paper is divided into the following sections: Firstly, we will discuss the transformation of the development path of rural areas in China, demonstrate the necessity of cultivating rural social capital, and explore the construction strategies of rural social capital with planners as the main body. Secondly, we use the social–spatial analysis perspective as the theoretical basis and take the human settlement environment as a breakthrough point to practice the specific methods of IMEE, which is “Intervene, Motivate, Enable, Empower”. Finally, we will use the upgrade process of small vegetable gardens in Hongtang village, which is located in Fengqing county, as an example to discuss the changes in the relationship between villagers, the village committee, and planners, as well as the connection with the superior government, so as to provide a reference for the improvement of social capital in rural areas.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Transformation of Development Paths in China’s Rural Areas

Since the 1960s, the process of urbanization in various countries has accelerated, population and capital have gathered in cities at a high speed, and the trend of village decline has become unavoidable [9]. In response to the decline of rural areas, developed countries have used government-led resources to improve village industries and infrastructure, such as small-town construction in the United States, rural reform in France, the village renewal movement in Germany, village building in Japan, and the new village movement in South Korea [10,11,12,13,14]. These practices of various countries have achieved positive results, but some practices adopt the model of exogenous resource introduction. The unbalanced and inadequate development of rural development has not been effectively solved, and some places have even produced resource consumption or environmental pollution problems [15]. With the injection of external resources, it is necessary to stimulate endogenous force and combine local development with social livelihood and the governance system to achieve the goal of sustainable development [16].

In China, many villages have completed poverty alleviation under the work of the government [17]. This is a “top-down” model, wherein the government is not only responsible for policy formulation and project selection but also dominates the collection and distribution of poverty alleviation resources. In the process of poverty alleviation, the Chinese government has experienced a transformation from emphasizing county-level poverty alleviation to village-level poverty alleviation, and then to individually targeted poverty alleviation [18]. Targeted poverty alleviation combines policy guidance, resource allocation, and farmers’ development conditions, eventually improving the effectiveness of poverty alleviation [19]. Poverty alleviation reflects a strong national orientation. Poverty alleviation is the central work of governments at top-down levels, so a lot of resources have been devoted to rural areas [20]. This has formed a working system of “five-level secretaries jointly grasp poverty alleviation”. The main battlefield of poverty alleviation is at the county level [21]. The greater the attention of the county party secretary to poor villages, the easier it is to achieve poverty alleviation [22]. Poverty alleviation further promotes the consolidation of the party’s power in rural areas and forms organizational and institutional resources for rural development [23].

As a result of poverty alleviation, the infrastructure and industries of rural areas have improved [24], and people’s living standards have risen [25]. However, some problems have also been exposed in the process of poverty alleviation [26]. Firstly, the marginal benefit of government investment is decreasing step by step. Although the government is still continuously investing resources into rural areas after poverty alleviation, the benefits obtained from the same resource inputs are decreasing [27]. Secondly, the simple emphasis on top-down policy intervention and assistance, which lacks the exploration of rural internal resources, may make some poverty-stricken households dependent [28]. Thirdly, compared with the government, the participation of market and social forces in poverty alleviation is not high, and the allocation of resources is limited [29].

Determining how to optimize the design of policies and fully mobilize the independent development ability of poverty-stricken people is an important issue in China’s current rural revitalization [30]. Many scholars have proposed a “bottom-up” development mechanism, which emphasizes self-development planning of the village itself and gives full play to the enthusiasm and main role of villagers in the selection, design, and implementation of rural revitalization projects [31]. Some scholars have studied the practice of “bottom-up” and found that it can encourage villagers to participate in the decision-making process, promote consultation to form social capital, reduce the waste of resources, and realize the integration of resources that are needed for various development plans [32]. There is no contradiction between “bottom-up” and “top-down” [33,34]. In the current period of rural revitalization, the government still continuously inputs resources to rural areas. The reason scholars emphasize “bottom-up” is to seek social capital and effectively connect with government resource allocation [35].

2.2. The Significance of Rural Social Capital

Rural social capital comes from the social relations between villagers. Bourdieu systematically analyzed the concept of social capital, which is defined as a collection of actual or potential resources owned and shared by members or groups of social networks [36]. Bourdieu believes that social capital exists in people’s relationship structures and can be transformed into economic resources to create value for individuals and society [37]. Furthermore, many scholars have given further explanations of social capital. Portes emphasizes that social capital is a kind of resource generated by social interaction, which often depends on stable social relations [38]. Nahapiet thinks that social capital exists in the relationship network of individuals or social groups and forms realistic or potential resources, which is conducive to the creation of new capital [39]. Putnam believes that social capital includes trust, norms, and social networks [40]. Krishna proposed two types of social capital: institutional capital and relational capital. According to his explanation, institutional capital is related to the structural elements that promote the development of mutually beneficial collective action, such as roles, rules, procedures, and organizations. Relational capital involves values, attitudes, norms, and beliefs that influence the formation of collective actions [41]. Lin defines social capital as being obtained by actors (whether individuals or groups) through social relations. Individual social capital refers to the social resources owned by individuals to achieve personal goals, including interpersonal relationships. Group social capital refers to the organizational resources of a group to achieve collective cooperation, including organizational networks, relationships, and culture [42].

Compared with physical capital and human capital, social capital has both the same and different characteristics. On the one hand, they have similarities. They are all accumulated, have a certain scale effect, can reproduce economic benefits, and need to be constantly updated in this process [43]. On the other hand, there are also differences. Social capital can achieve reciprocal effects in use and its role is not only reflected in the production of material value but also in the sharing of income, so it can cover a larger group of residents [44]. More importantly, social capital can be regenerated through effective guidance, but its use is limited to a specific group in a certain region and has an inalienable characteristic [45]. In general, social capital in different regions will not be the same, and the level of social capital can be observed with the following four points: sense of community, collective efficacy, public participation, and proximity [46]. In a village, the sense of community is the degree of villagers’ attachment to the village. Collective efficacy is the feasibility and efficiency of village collective action. Public participation refers to the degree of villagers’ participation in rural affairs. Proximity refers to the relevance of villagers’ daily lives, which is used to characterize the convenience of communication [47].

Social capital is of great significance to the sustainable development of rural areas in social, economic, and political functions. Firstly, for the social function, it can form an atmosphere of mutual trust among residents, form positive feedback, and promote the improvement of the knowledge structure [48], which then can gradually evolve into common norms and a consensus of rural community [49]. Secondly, for the economic function, social capital can reduce transaction costs, accelerate the flow of information and innovation, and transform into financial capital. As the Nobel economic prize winner Arrow points out, every business or social affair has its credit as the basic element and social capital can make our society run smoothly and quickly [50]. Thirdly, social capital effectively promotes rural self-management [51]. By establishing an institutional mechanism to ensure ideal collective action, social norms and network connections are strengthened, which forms positive feedback and strengthens the mechanism itself. When the government and market behavior is carried out in such a social interaction network, the phenomenon of opportunism and inaction can be reduced [52,53].

In China’s rural areas, society is experiencing a high-speed transition, mainly reflected in the following aspects: from agricultural society to industrial society and post-industrial society, from rural society to urban society, from closed or semi-closed society to open society, and from ethical society to legal society [54,55]. The transformation of rural areas is an all-round change in society, economy, and politics, which is highlighted in the outflow of population and the change in age structure and deeply reflects the change in social relations and networks within the village. Traditional human society is a kind of homogeneous social capital, and the relationships between villagers depend on blood relationships. A strong homogeneous relationship provides the basis of trust and reciprocal relationships among members, which has long been convenient for cooperation and coordination within a village [56]. However, social capital after the rural transformation tends to be heterogeneous. The villagers maintain contact with family and friends of migrant workers but lose contact with other villagers in the village [57].

With the background of rural social change in China, if there is no external force intervention, the social capital of a community is determined by history, which is “path dependence” and may form a virtuous circle or a vicious circle [58]. For many villages that have just achieved poverty alleviation, social capital is often missing. Due to historical inertia, social capital cannot be formed on its own, and community external links provide a basis for linking government resources and community assets [59]. Therefore, effective intervention and guidance are needed. As a result of poverty alleviation and rural revitalization, under the government’s extensive investment of resources, social forces such as planners have intervened in villages as an intermediary to link the loose individuals in the village [60,61]. The core of this process lies in coordination, which can motivate and empower villagers in participatory planning and form a stable community norm and relationship network [62]. Eventually, it promotes the power to engage in dialogue with the village committee and superior government and shapes the vertical connection with the government‘s power structure [63].

2.3. The Construction Strategy of Rural Social Capital

Rural social capital plays a role through social resources related to multiple actors, and the construction process of rural social capital is also a process of exploring relevant social resources [64]. Firstly, it is important to identify who the key players are, concerning the active government, mobilized community management organizations, and residents, in order to build a collaborative relationship. The complementarity and embeddedness are combined to form a horizontal and external vertical relationship network within the village [65,66]. In addition to the social interaction between villagers, the government intervenes in a village through the allocation of public service resources, which is the embodiment of its performance. The villagers’ trust in the local government’s implementation of development plans promotes villagers themselves to participate in collective action [67]. The village committee is an organization of village autonomy. However, there is now the problem of administrative tendency in the village committee, which has led to a lot of paperwork such as statistics and statements but has alienated its relationship with the villagers. Therefore, the village committee needs to reconstruct the traditional local governance experience and provide social capital for collective organizations through the integration of rural society [68].

Social capital can be quickly constructed through the external support and cultivation of internal actors. Starting from specific events of small-scale space, cooperation can be promoted through the repeated interactions of villagers, and the sense of responsibility of villagers can be cultivated through empowerment [69]. The construction of social capital is not only an interaction at the rural level but also needs to be carried out in a wide range of political and social environments. The external environment is of great significance for ensuring fairness within the countryside [70]. So, it should be considered comprehensively with autonomy, internal/external connections, and investment return. Among them, “autonomy” is the ability of villages to implement plans independently; “internal/external connections” include economic and political connections within and outside the village; “investment return” refers to the fact that the construction of social capital needs to be considered with social, economic, or cultural returns to ensure the investment is worthwhile [71].

Guiding residents to participate in collective action to build an atmosphere of trust and cooperation is conducive to the cultivation of social capital [72]. Collective action should be adapted to individual development and respect for local diversity, which is also an efficient way to increase social capital [73]. The goal of collective action is to optimize the rural infrastructure and natural environment, which, in turn, has a positive impact on the improvement of rural cohesion and the introduction of external resources [74]. The object of collective action is many small projects, not a few large projects. Under the support of small projects, rural social capital accumulates over time [75].

Kreitzman proposed five steps to construct social capital [76]. Firstly, draw social capital maps from the current situation of rural areas, including the capabilities and resources of individuals and social forces in rural areas. Secondly, build social relations among multiple subjects in rural areas. Thirdly, mobilize social capital to complete economic development and information sharing. Fourthly, formulate a vision for community development and combine community planning with problem solving. Finally, after fully mobilizing social capital, combine it with external resources to support local development. However, in practice, scholars often improve social capital through social organizations, artists, and other forms simply by emphasizing the exploration of rural endogenous forces and relatively ignoring the connection with those not within the countryside [77,78].

In the context of China, the improvement of rural social capital not only depends on the stability of internal villagers’ social relations but also on communication with the government [79,80]. We will put forward the strategy of rural social capital construction from the perspective of planners. As a link between the government and villages, planners take the specific space as a breakthrough point [81], guide the village committee and villagers to form collective actions within the village, promote communication between the government and villagers outside the village, and can realize sustainable development [82].

2.4. Rural Participatory Planning for Social Capital

Planning is not only a space technology but is also a process of solving social problems and building social capital. Planning is a public policy whose goal is to help the poor and promote a more equitable distribution of resources [83]. In the 19th century, Howard proposed the concept of a garden city, hoping to reshape social relations and solve social problems through the construction of material space [84]. Participatory planning can explain and weigh the values, lifestyles, and cultural traditions of multiple subjects and construct a reasonable spatial form, deepening the relationship between social members [85].

The participatory planning idea of public participation originated from the trend of pluralism in the 1960s [86]. As daily life becomes more and more diversified and fragmented, no form of objective knowledge exists and all knowledge is relative, requiring collaboration among multiple subjects to learn from each other and build consensus [87]. The role of planners has changed from technicians to negotiators, organizers, and guides of planning. Planners promote consensus among the government, enterprises, social organizations, and citizens to ensure substantive public participation through the establishment of joint mechanisms for planning and decision-making [88]. Public participation can not only generate the optimal options for the problem but also form individual and collective learning, thereby enhancing social capital and promoting the participation of villagers in governance activities [89]. Through collaboration, governance resilience in villages is promoted to better address current and future changing and complex and fragmented multi-systems and make planning more scientific for future expectations [90].

Participatory planning can improve the rural material space environment and cultivate a good sense of place and belonging [91]. When it comes to public participation and the sense of place, most of the existing research focuses on personal feelings and experiences but rarely places them in the socio-political environment [92]. In participatory planning, the emphasis is on public participation and empowerment, along with an in-depth analysis of the potential people–space linkages in communities and how to promote public participation through such linkages [93].

In rural planning, research on the interaction between people and people and between people and space in the process of public participation is the focus [94]. This process involves multiple subjects jointly discovering and solving problems [95]. It is an important channel for building rural social capital to effectively empower villages through public participation. Public participation can promote the interaction of multiple subjects, close social relations, and enhance the endogenous power of villages [31,96]. Rural society is a free and open system in which multiple actors participate in meaningful communication with each other. The planners use participatory design methods to design rural society (interpersonal relationships, village regulations, customs, etc.), improve various social relations such as neighbors, cadres, and clans in rural areas, and construct villagers. Finally, planners can construct the villagers’ value system and institutional environment by motivating and empowering villagers [97] to form a sustainable action path.

In order to solve the problem of rural planning, China has made many efforts in attracting talent to the countryside. There are many forms of rural planners, and groups of college students represent a new force that can participate in rural planning and construction [98]. In recent years, the government has issued policies to train groups of college students and rural governance talent in rural areas [99]. Under the guidance of the national policy system and the opportunity of rural planning, college students who combine college courses and professional practice as rural planners participate in rural construction actions through different channels, bringing new directions and strengths to rural construction in the new era [100,101].

As planners, college students play a unique role in improving rural social capital. Firstly, college students have always been the dominant force in the inheritance and innovation of cultural knowledge. They are full of curiosity and enthusiasm for exploring and transforming the world and have unlimited creativity that is not limited to the existing framework, and they can then transform this into key resources for community development [102]. Secondly, college students have certain professional knowledge, which can be combined with local knowledge and reproduced by local villagers [103]. Thirdly, college students play a role as a medium of communication and consultation in rural work. On the one hand, they have the affinity to motivate, enable, and empower villagers, and can establish good social ties with villagers. On the other hand, they can also pass on the needs of the villagers upward to play a role in connecting the government, the public, villagers, community organizations, and multiple other groups [104]. Fourthly, college students do not involve complex interests, can maintain relatively independent value judgments, and can participate in community transformation as a third-party force [105].

3. Theoretical Framework

3.1. A Social–Spatial Analysis Perspective

The social–spatial perspective is not a “social space” that regards “society” as a determiner, but rather integrates “society” and “space”, reflecting a continuous two-way process between people and space; that is, people transform space based on practical activities and are influenced by space in many ways [106].

The concept of social–spatial was put forward by Lefebvre. He clearly pointed out that space is the product of society [107]. As a result of the interpretation of Harvey, Foucault, and other scholars, social–spatial has become one of the classic topics in urban and rural planning. Social–spatial can be understood from two aspects: “Sociality of space” and “Spatiality of society” [108]. “Sociality of space” shows that space is the product of society. Space production theory holds that space is both the means and object of production. Therefore, each mode of production has its own special space. The transformation from one mode of production to another will inevitably be accompanied by the production of new space. “Spatiality of society” means that spatiality is both the medium and the result of social behavior and social relations. All social relations and social actions are materialized as social existence only when they project themselves into space, that is to say, spatiality is both a product and a producer [109]. Therefore, the concept of social–spatial is more inclined to a methodology of cognitive society and space. By discovering the political, economic, and social motivations behind the spatial form and its change process, the spatial production process and the social change process are combined to discuss the dialectical relationship between society and space.

Correctly understanding the connotation of space is a necessary condition for analyzing the motivation of planners’ behavior. Different from the previous methods of social organizations or artists’ intervention in practice, the improvement of rural social capital led by planners emphasizes continuous design with space as the breakthrough point. Rural space is not a simple material space but rather also contains rich and complex social relations [110]. In the history of China, rural areas have been planned and various resources have been allocated with space as the core. Through the spatial order of bottom-up unit combination and top-down resource allocation, the combination of national governance and regional development has been realized. “Guanzi” (a cultural classic in ancient China) has been expounded as a spatial unit that balances people and land. It can integrate and allocate various elements such as land, people, tax, currency, and valley to form a matching relationship between land fertility, population size, and tax volume. At the same time, this space unit is also the basic unit of social organization and management, with internal cohesion and identity [111].

Rural space is the catalyst of social capital as, on the one hand, it creates a good space environment, and on the other hand, on the basis of the space environment, it creates a harmonious society and the villagers’ own village. The villagers live in their own homes for a long time, so they can perceive, experience, and evaluate the space beside them so as to measure its quality and vitality [112]. When people and space are in a harmonious and unified relationship, villagers form a sense of place attachment and collective identity; when people are out of touch with space, villagers’ sense of identity with the place will dissipate and the traditional neighborhood relations and collective consciousness will gradually fade. Therefore, an accurate understanding of the relationship between people and space is the first step for planners to cultivate rural social capital.

The improvement of social capital with space as the breakthrough point includes two key points. The first point is the physical environment emphasized by rural planning. The material environment is the result of the interaction between natural factors and social factors, including the house at the micro level, roads and settlements at the meso level, the whole village at the macro level, and so on, which are combined to form a hierarchical system of neighbors, settlements, and villages [113]. The second point is the collective activities, knowledge interaction, and social relations emphasized by social capital [114]. These three factors complement each other, all taking the material environment as a carrier. Residents carry out various collective activities around the material environment, gradually construct the common consciousness of local knowledge, and engage collectively in repeated daily activities. As abstract cognition and emotion, local knowledge and social relations cannot be directly created; rather, only with the help of the role of the material environment and collective activities can villagers form a consensus, unite the neighborhood and social relations with space as a link, and enhance social capital [115].

A rural garden is an important human settlement environment. Existing research shows that many planners have regarded the construction of rural gardens as a source of social capital accumulation [116,117]. On the one hand, the garden is closely related to all villagers, which helps to promote collective action under the logic of collective ownership of rural land, forming knowledge interaction and social exchanges between villagers. On the other hand, it can cultivate villagers’ autonomy and decision-making ability in the construction of gardens. More importantly, farming culture is one of the most important characteristics in China, as the Chinese have always cherished the yearning for pastoral life. In ancient times, pastoral culture was the pursuit of society. In modern times, the invasion of social industrialization and urbanization into the countryside has made more and more villagers realize the significance of a beautiful home. Therefore, guiding villagers to form a consensus through a small and beautiful settlement environment such as a small garden is an important way to improve social capital.

In the construction of rural planning and social capital, there are four main bodies closely related to space: villagers, village committees, the superior government, and planners [118]. These four are not a top-down linear relationship, but rather influence each other, showing a long-term, dynamic process. Rural planning needs the cooperation of the four parties so as to build attractive, practical, meaningful, and lasting social capital. Among these four, the internal participation of the village and the external connection are particularly important. We will mainly introduce how planners can make contact with the higher-level government and guide the village committee and villagers to participate in the improvement of social capital.

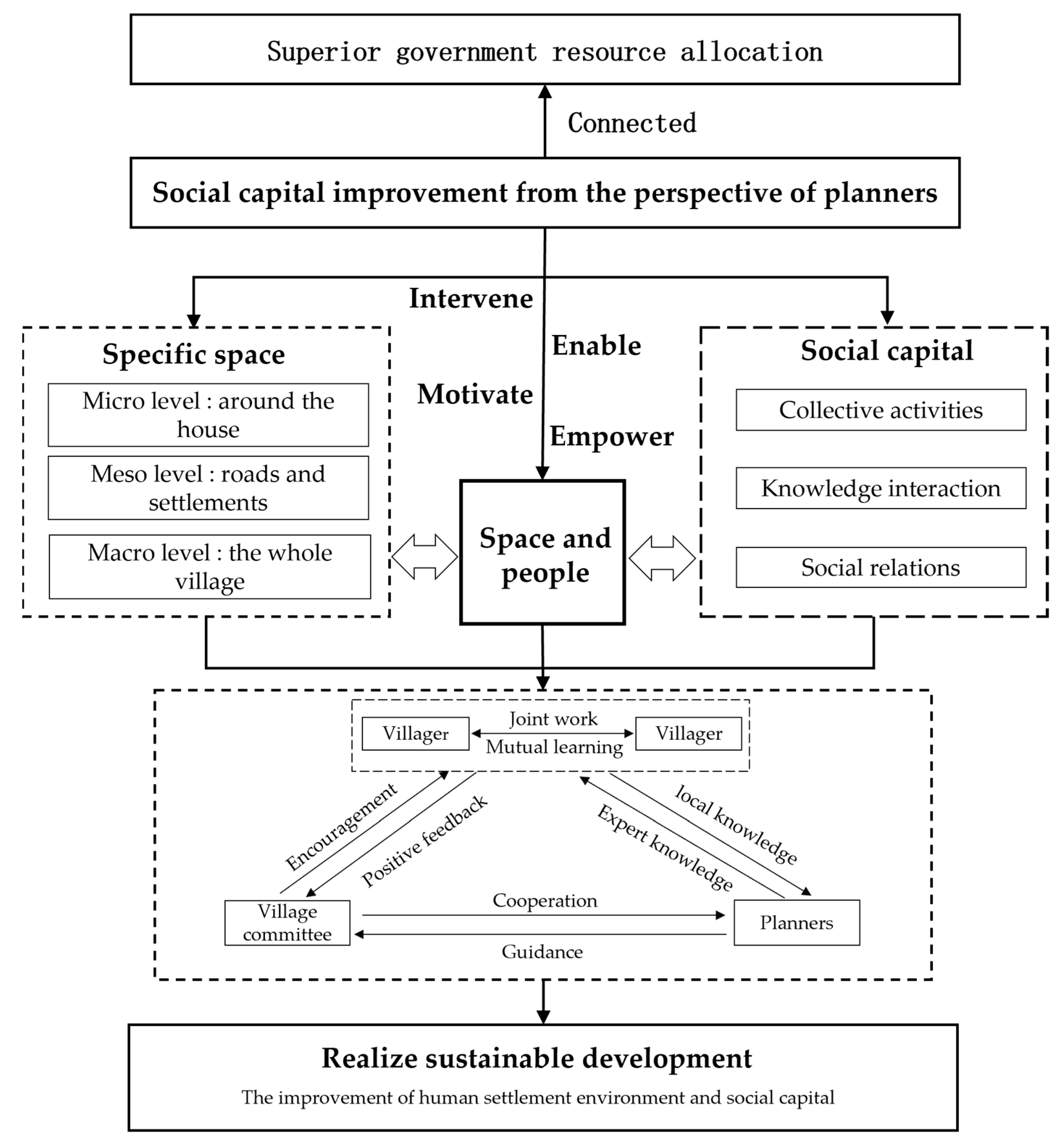

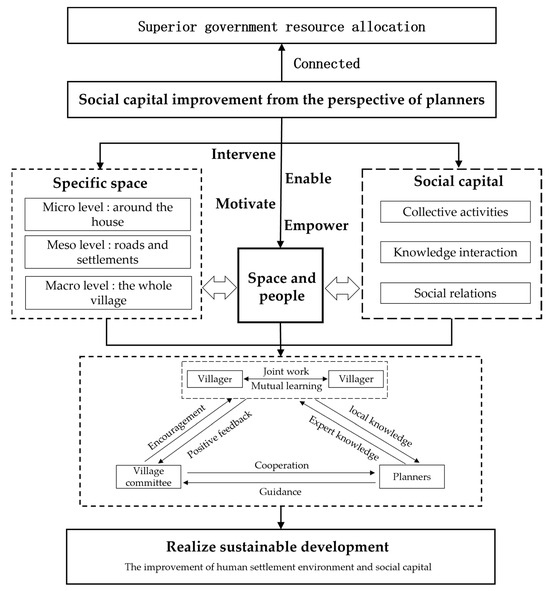

3.2. Framework of Improving Social Capital through Rural Planning

The improvement of rural social capital is a process in which planners design rural society. It can be divided into four processes of IMEE: Intervene, Motivate, Enable, and Empower [119,120]. Firstly, “Intervene” is a prerequisite for the trust of all parties. The planners should have an opportunity to intervene in the village. After investigating the basic situation of the village, the villagers’ meeting should be organized to form a planning consensus. Secondly, “Motivate” mainly includes material incentives and non-material incentives. “Reward instead of subsidy” is the main form of material incentives, in which planners and government use rewards to replace traditional subsidies to encourage villagers to participate in space transformation. The form of non-material incentives mainly works to enhance the subjectivity of villagers through joint planning and joint labor. Thirdly, “Enable” refers to planners fully exploring human and material elements related to rural planning, utilizing local knowledge, and enhancing the participation ability of villagers. Fourthly, “Empower” stipulates that planners give villagers power through formal or informal systems on the basis of “Enable” and turn to behind-the-scenes guidance. Planners evaluate the results of rural planning through remote communication and regular return visits. With the deepening of the four stages, villagers can actively explore and organize the relevant elements of the transformation of the human settlement environment, and can even help surrounding villagers, and the villagers’ initiative and participation ability are gradually improved.

Within the village, the process of rural planning is the process of deepening the interaction between village committees, planners, and villagers. The first step is the change in the relationship between the village committee and planners. On the basis of the common goal of rural revitalization, these two form the initial alliance, which belongs to the relationship of guidance and cooperation in the relationship structure, and trust is deepened with continuous communication and practice. The second step is the change in the relationship between villagers and the village committee. The villagers are the core subject of the transformation of the human settlement environment, and under the incentive of the village committee, they actively participate in rural construction. The human settlement environment and social relations can be effectively improved, which, in turn, has a positive feedback effect on the village committee. The third is the change in the relationship between villagers and planners. Planners guide villagers to complete the transformation through the process of IMEE, combine expert knowledge with local knowledge, reduce the cost of transformation, and promote the improvement of the knowledge structure of both sides. The fourth step is the change in the relationship between the villagers. Taking the transformation of the human settlement environment as an opportunity, the villagers are reorganized to construct social relations and interactive knowledge in labor. At the same time, the results of the transformation of the human settlement environment will encourage surrounding villagers to optimize their space independently.

Outside the village, planners actively communicate with the superior government. As a bridge between the government and the village, they reflect the current situation and requirements of the village development to the superior government and guide the superior government to effectively link the resource allocation to the social capital of the village (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

The research framework of this study.

4. An Empirical Practice in Hongtang Village, China

4.1. Introduction of Hongtang Village

Hongtang village is a typical remote mountain village in Yunnan Province. It belongs to Fengqing county, Lincang City. It achieved poverty alleviation in 2019, but the human settlement environment was still chaotic, the collective activities in the village were missing, and the collective consciousness was weak. In 2013, Sun Yat-sen University began to help Fengqing county. The China Regional Coordinated Development and Rural Construction Institute of Sun Yat-sen University entered Hongtang village in 2021 and compiled the “Rural Planning of Beautiful Hongtang Co-creating” (hereinafter referred to as “Planning”). The college planners took the upgrade of small vegetable gardens as a breakthrough point and continued to improve social capital through the strategies of IMEE. In June 2022, the Yunnan Provincial Department of Agriculture and Rural Affairs formulated the “Three-Year Action Plan for Green and Beautiful Villages in Yunnan Province”, requiring all counties to coordinate resources to build “Green and Beautiful Villages”. Fengqing county raised a social donation of 50,000 yuan for the upgrade of the human settlement environment in Hongtang village. Planners improved social capital in the upgrade of small vegetable gardens and promoted the efficiency of fund use.

4.2. The Upgrade Process of Small Vegetable Garden

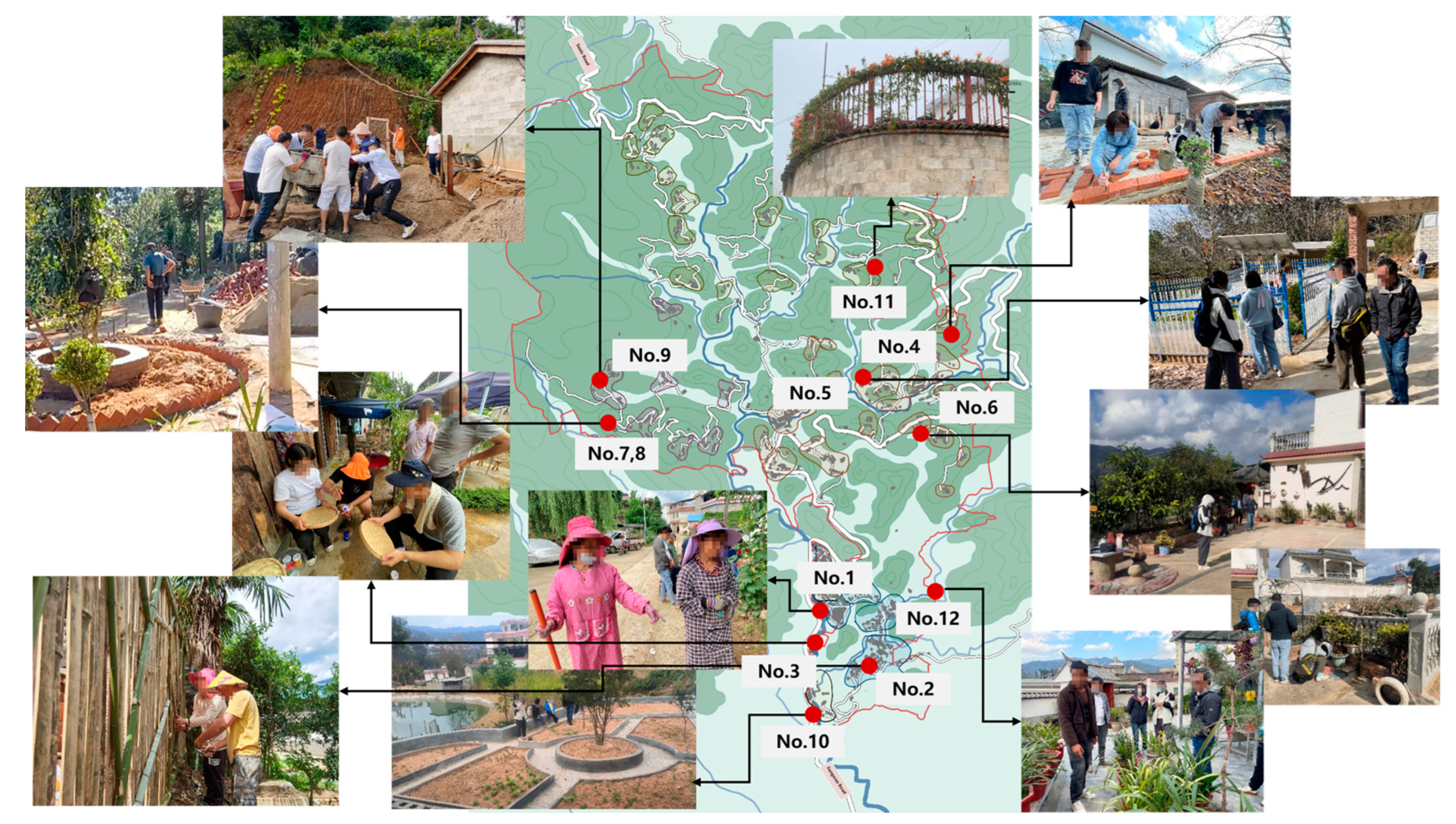

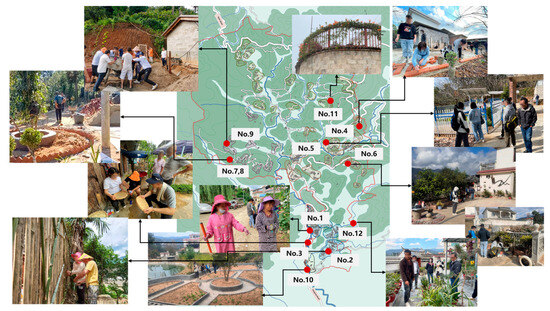

Up until December 2023, with the participation of planners, Hongtang village has completed 12 small vegetable garden renovations (Figure 2). Each upgrade is a process of continuous improvement of social capital, reflecting the evolution of IMEE. As representatives of the different stages of the process, we evaluate the first, second, and eighth vegetable gardens as examples for the comparative analysis. In addition, we will also introduce an example of a completely spontaneous upgrade by villagers.

Figure 2.

Twelve small vegetable gardens that have been improved in Hongtang village with planners’ assistance. Source: the authors.

4.2.1. From “Intervene” to “Motivate” (November 2021 to May 2022): The Construction of a Demonstration Site to Drive the Surrounding Villagers

The improvement of small vegetable gardens is the main action plan of “planning”, which is highly valued by the village committee. Throughout the whole village investigation and surveys, the village committee and planners initially selected the first batch of alternative points for upgrade. Zhang’s home is one of the first batches, located near the county road, next to Hongmu Road, adjacent to the public parking lot in the center of the village, which is the location of various collective activities in the village. Before the upgrade of the small vegetable garden, the weeds were overgrown and a large number of other materials were piled up in disorder, which not only hindered the view but also affected the daily use.

The village committee and planners decided to make this the first demonstration site to encourage villagers to join the upgrade of small vegetable gardens. Therefore, the first improvement cost is fully subsidized. At the same time, the village committee, Zhang’s family, and surrounding villagers were coordinated to participate in the transformation work in the whole process by adopting a working method of working and eating together (Figure 3). This upgrade took one week to complete, which was able to be perceived, experienced, and evaluated by every passing villager as it is a natural local exhibition site. After the upgrade of the first vegetable garden, many villagers expressed their willingness to participate.

Figure 3.

The improvement of Zhang’s small vegetable garden. (a) Before the improvement; (b) the design rendering; (c) the construction process; (d) after the improvement. Source: by the authors taken in May. 2022.

4.2.2. From “Motivate” to “Enable”(June 2022–August 2022): Coordinated Use of Surrounding Resources under the Guidance of Planners

In June 2022, the Department of Agriculture and Rural Affairs of Yunnan Province required every county to build “Green and Beautiful Villages”. After consulting with the county government and village committee, planners decided to expand the upgrade of small vegetable gardens. The first small vegetable garden played a demonstration effect, but “full subsidy” was not suitable for large-scale promotion. Therefore, planners and the village committee had a detailed exchange on the system of “awards instead of subsidies”, and then formulated an implementation method.

The implementation method was an institutionalized form of the motivation process. It regulated the implementation of the project from the aspects of reward conditions, reward standards, management regulations, and project processes to encourage householders and surrounding villagers to participate in the upgrade of the small vegetable garden. In this context, planners continued to guide the village committee and neighbors to help so as to motivate the family of the small vegetable garden. In the countryside, the neighbors who came to help mostly represented the good popularity of the family, so villagers were keen to invite relatives and neighbors to participate in the upgrade of their own small vegetable garden.

The implementation method stipulated the unit price (50 yuan/m2) and the upper limit (the reward for each small vegetable garden upgrade cannot exceed 6000 yuan) of the reward amount. Therefore, villagers would gradually explore raw materials that could be used in the village to reduce the cost of upgrade. Taking the second Yang’s home as an example, his own land has a large number of natural materials such as bamboo and stone; therefore, the upgraded design made full use of the existing materials. The small vegetable garden took a piece of tea as the design image and designed the entrance platform, tea table, vegetable ridge, flower area, and other areas, using bamboo fences and decorative bamboo walls.

This upgrade was strongly supported by the village committee and surrounding villagers, and all people jointly participated in the construction of stone handling, sawing bamboo, and bamboo piling. In this process, villagers taught each other their own knowledge and worked together to build a beautiful home (Figure 4). The upgrade of the small vegetable garden took 10 days to complete, and the surrounding resources were mobilized as much as possible, which greatly reduced the upgrade cost (more than 200 flat vegetable gardens cost less than 5000 yuan).

Figure 4.

The improvement of Yang’s small vegetable garden. (a) Before the improvement; (b) the design rendering; (c) the construction process; (d) after the improvement. Source: the authors, taken in August 2022–December 2022.

4.2.3. From “Enable” to “Empower” (after September 2022): Villagers Independently Mobilize Surrounding Resources for Upgrade

Before September 2022, planners personally went to Hongtang village and participated in the upgrade of four small vegetable gardens. In these processes, the related people (village committees supporting work, enthusiastic villagers, skilled craftsmen, etc.) and objects (available raw materials, suitable landscape, etc.) were sorted out and organized. Therefore, after September, the planners empowered villagers to upgrade their own small vegetable gardens, communicated with villagers online, and guided villagers to use the human and material resources around them to independently complete the upgrade, thus stimulating the endogenous power of the village.

The subjectivity of villagers in Hongtang village has deepened. After the joint design with planners, they carried out their own upgrade. Taking the design of the eighth small vegetable garden as an example, the planners communicated with Mei online and jointly determined design ideas: because this site was shared by brothers, the theme of ‘heart to heart’ was finally selected. Mei put forward many suggestions on the design, such as using dead wood, tires, and other materials around the house because the site is high so they want a viewing space, a guardrail, and so on.

After the joint design was completed, Mei’s household drew on the experience of the first few households and independently allocated the surrounding people and material resources for upgrade. The planners continuously optimized the design through online communication during the construction process (Figure 5). Compared with the previous upgrade, the subjectivity and ability of villagers had been greatly improved.

Figure 5.

The improvement of Mei’s small vegetable garden. (a) Before the improvement; (b) the design rendering; (c) the visit of planners; (d) after the improvement. Source: the authors, taken in September 2022–December 2022.

The process of “empower” needs to establish evaluation criteria and a management system. In the process of transformation, one villager attempted to ‘cheat funds’. After determining the design plan online with planners, the garden was not constructed according to the design, and the upgrade process was not interactive and completed at will. Therefore, it is necessary to support system construction for the empowerment process and avoid the untruthful behavior of some villagers by means of villagers’ self-evaluation, mutual evaluation, and multi-party evaluation. During the return visit, the planners organized the village committee and villagers’ assembly to determine the mutual evaluation system and finally formulated the provisions for the distribution of funds in batches. Only the construction of well-managed and qualifying small vegetable gardens could obtain the award amount.

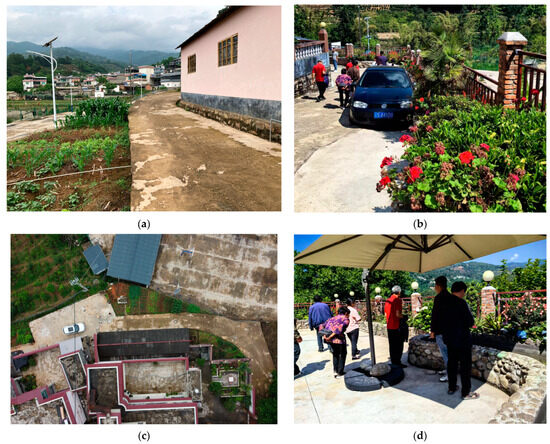

Through the strategic process of IMEE, the planners have successfully inspired many villagers to spontaneously join the improvement of the human settlement environment. Taking Wang’s home as an example, after seeing the transformation effect of Zhang and Yang’s small vegetable garden, he exchanged learning experiences with these two families and transformed an open space in front of his home into a small garden with a pool (Figure 6). This process was entirely completed by Wang himself by inviting craftsmen and surrounding neighbors, without the participation of planners. After construction, Wang took the initiative to apply for rewards to the village committee. In order to encourage more villagers to be like Wang, the village committee allocated reward funds to him according to the implementation method formulated previously (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

The improvement of Wang’s small vegetable garden. (a) Before aisle improvement; (b) after aisle improvement; (c) aerial view of the site before the improvement; (d) the villagers’ visit after improvement. Source: the authors, taken in September 2022–May 2024.

5. Discussion

5.1. Social Capital Improved through Rural Planning

Since the beginning of modern times in China, rural planning has always been a method to solve rural social problems. During the period of the Republic of China, Yangchu Yan, Shuming Liang, Zhixing Tao, and other intellectuals prevented the continuous decline of the countryside in the process of modernization to a certain extent through the construction of water conservancy, rural education, cooperative life, and production and cultural undertakings [121]. After the founding of the People’s Republic of China, the government promoted the design of the countryside and organized professionals to quickly plan the people’s communes; at this time, rural planning was a tool to facilitate collective production and life to meet the needs of rapid accumulation in the early days of the founding of the PRC [122]. After the reform and opening up, the reform of the land system led to a large-scale housing boom among villagers, and rural planning has become a means for village organizations to fight for the right to development. Villages are planned around increasing income, and the rural urbanization phenomenon has emerged. During this period, the government’s guidance and control of rural planning and rural construction were weak, leading to the disorderly expansion of rural space and the destruction of rural order. With the deepening of urbanization, the strong siphon effect of the city has prompted the forced flow of rural resources into the city. At the same time, the city culture and values are also spreading to the countryside [123]. Traditional agricultural and rural modernization has caused damage to the rural environment and social capital [124].

Since the start of the rural revitalization, the government has rationally coordinated the allocation of various resource elements in the rural space and has successively carried out rural construction actions such as rural housing water and toilet reform, household appliances and solar energy going to the countryside, farmland standardization construction, roads, communications, etc. Rural planning has generally adopted the project system for a long time. Although it can concentrate on the efficient allocation of resources to promote project construction, there are also difficulties regarding the effects of project construction and an uncoordinated construction process caused by the multi-objective nature of the project itself. Although the intervention of government and capital in rural planning is important, the fundamental breakthrough of the rural development path lies in the reshaping of rural governance and social capital. Rural space carries social relations, and the process of rural human settlement construction is also the process of social development and integration. The goal of rural construction should be internalized into the spiritual pursuit and conscious action of villagers so as to realize the benign interaction between rural construction and social capital.

Facing the goal of improving social capital, the goal and path of rural planning should change accordingly, from solving a single problem to exploring the idea of rural sustainable development under the superposition of multiple contradictions. Rural planning returns to the villagers themselves. While improving the rural material space, planners design the rural society, promote the connection between government resources and villagers, and explore the path of rural revitalization from the perspective of combining local social changes and national policies and systems so as to realize the transformation of rural areas from exogenous support to endogenous development. For a long time, the high dispersion of the countryside was completely different from the spatial order emphasized by the city, as spontaneous and scattered construction behavior is the universal state of the countryside. Therefore, planners needed to design rural society and guide villagers to form collective action.

In Hongtang village, the government has carried out public service facilities before the planners’ intervention. However, it can be found that the facilities have been unattended for a long time, and there are problems such as streetlamp aging, river blockage, and a chaotic human settlement environment. The reason is that villagers do not participate in the government resource allocation system as they are prone to indifference. The planners started with a human settlement environment that villagers cared about, guided villagers, the village committee, and higher government to talk to each other, and finally realized the stability of the relationship and improved rural social capital. The following will focus on the analysis of the changes in social relations and knowledge interaction among multiple subjects.

5.2. Social Relations and Knowledge Interaction among Multiple Subjects

In the process of improving small vegetable gardens, the planners always maintained contact with the deputy county governor of Fengqing county and the director of the Rural Revitalization Bureau, guiding the Fengqing government to effectively link the “Green and Beautiful Village” project with the beautification of the human settlement environment of Hongtang village and coordinate funds for the upgrade of small vegetable gardens. In order to improve the efficiency of resource use, the planners gradually explored social capital within Hongtang village, guided the village committee, villagers, and planners to learn from each other in collective action, and promoted the deepening of relations.

The first point is the knowledge interaction and social relations among villagers. Planners stayed in the village for a long time in the early upgrade of the small vegetable gardens and found that the villagers changed from bystanders to collaborators. When the first family was upgraded, the villagers felt very novel, all came to watch, joined the labor under the impetus of the village committee, and improved the neighborhood relationship in mutual cooperation. With the deepening of the transformation process of small vegetable gardens, the villagers have been able to organize the craftsmen and surrounding neighbors to complete the upgrade by themselves in the “Empower” stage. On the one hand, this reflects the improvement of the villagers’ participation ability, while on the other hand, it also shows the increasingly close relationship between the villagers. The small vegetable garden has been transformed into a window for neighborhood interaction. While sharing a beautiful environment in the neighborhood, it has also formed invisible supervision, encouraging each other to manage and protect human settlements.

The second point is the knowledge interaction and social relations between the village committee and villagers. China implements rural collective ownership, and collective property rights have a profound impact on the collective action logic of villagers [125], as well as the rural construction model. For villagers, many events related to their own interests are inseparable from the support of village collectives, and village collective activities further strengthen the internal integration of acquaintance society. The members of the village committee are generally local villagers and have a certain mass base in the village. The effective organization of the village committee is a necessary condition for the smooth upgrade of human settlements. Under the guidance of planners, the village committee participated in the process of upgrades, which greatly encouraged the households and surrounding villagers. The villagers provided positive feedback to the village committee, which meant the village committee personally experienced the changes in rural space. The village committee itself had also changed: from the beginning, it was difficult for them to take time out of the busy village affairs, but later on, they took the lead in helping villagers. Through this process, the relationship between the village committee and villagers gradually grew closer.

The third point is the knowledge interaction and social relations between planners and villagers. Farming-reading culture is one of the characteristics of rural culture. Villagers’ respect for knowledge enables planners to integrate into villagers relatively smoothly [126], and villagers always have great enthusiasm for planners because they are students from Sun Yat-sen University. A villager once said, “Sun Yat-sen University gave us a lot of help, I can not return, but only tell my future generations”. In the process of the small vegetable garden upgrade, the relationship between planners and villagers changed from a lack of mutual understanding in “Intervene” to working and communicating together in the process of “Motivate” and “Enable”, and finally, to mutual trust during the “Empower” stage. At the same time, planners and villagers had knowledge interactions, learning from each other through the small vegetable garden. On the one hand, villagers provide planners with many opportunities to learn rural knowledge; on the other hand, planners improve the aesthetic appreciation ability and design level of villagers. What is more, planners also narrate the significance of the construction of small vegetable gardens to the villagers through exchange seminars, management, and training to strengthen the construction and management of the villagers.

Finally, we note the knowledge interaction and social relations between planners and the village committee. Planners had the task of poverty alleviation and could easily intervene in Hongtang village. However, in the context of grassroots autonomy, planners must first reach a consensus with the village committee to truly carry out rural work. Therefore, planners first made the village committee ideologically recognize this working method through training and case presentation, and then encouraged them to participate in labor to drive villagers and harvested the positive feedback of the villagers. The real recognition of social capital is an important means to activate the endogenous power of rural revitalization. In this process, the village committee continued to authorize planners to carry out work in the village, while giving the necessary support (institutional support, human support, publicity support, etc.). Guidance and cooperation were deepened in the process of continuous communication and practice. In the later stage of the upgrade of the small vegetable garden, the village committee obviously recognized the effectiveness of rural planning and had a vision and commitment to future work. The village party secretary said: “Small vegetable garden, big change! The small vegetable garden not only carries the transformation design of residential spaces but also connects our villagers with the village committee through the practice of joint creation. The power of the collective is great, it will promote the improvement of the surrounding environment and the improvement of social relations, I believe that the development of Hongtang village will be better and better”.

6. Conclusions

This paper argues that rural space and social capital coordinate and promote each other, using the upgrade of small vegetable gardens in Hongtang village as an example to explore the social capital promotion strategy of rural areas in China. Different from previous research and practice, we put forward a method of planners’ intervention, combining rural planning with the cultivation of social capital, organizing villagers to carry out collective action, and building a perceptible, experiential, evaluable human settlement environment to improve social capital in this process, achieving knowledge interaction and relationship improvement.

We hold that the improvement of rural social capital is a process of connecting with the allocation of resources of higher-level government and deepening the interaction between planners, villagers, and village committees. It can be roughly divided into four stages of IMEE: Intervene, Motivate, Enable, and Empower. The “Intervene” process is the starting point of the interaction among multiple subjects, and the initial cooperative relationship is established so that planners have a preliminary understanding of the current situation and upgrade plan of the small vegetable garden through field research and interviews. The “Motivate” process works to fully enhance the initiative of villagers and stimulate the subjectivity of the masses through material incentives (“reward instead of subsidy”) and non-material incentives (design, communicate, and work together). The “Enable” process functions to fully explore and organize the people and things related to the upgrade of the small vegetable garden, so as to reduce cost. The “Empower” process works to give the villagers power. On the basis of the formed system and organization, villagers will actively allocate their own ability combination, and villagers’ knowledge structure and participation ability are obviously improved. Eventually, this process promotes the gradual deepening of relationships between villagers, village committees, and planners to enhance the social capital of rural areas and realize sustainable development.

In the empirical study of small vegetable garden improvements in Hongtang village, we used the IMEE planning strategy to give villagers more ability to participate in rural development, effectively enhancing the social capital required for village development. We took the villagers’ vital settlement environment as the breakthrough point to provide them with participation motivation, build a multi-party participation consultation platform, and form a long-term participation mechanism with the support of external resources provided by the government. After improvement, the use function of the small vegetable gardens is much better and can meet the needs of villagers’ diverse social activities. More importantly, in this process, the relationship between villagers, village committees, planners, and the government gradually improved. As experts and negotiators, planners guide villagers to improve their knowledge, skills, and behavior. At the same time, they communicate with the government and the village committee so that the government-led mechanism system and resource allocation can guarantee villagers’ normalized participation in rural affairs.

This paper also has research shortcomings. There are few samples in this case (12 small vegetable gardens have been transformed as of December 2023), and due to the differences in natural characteristics, cultural features, and social relations between different villages, the application of the above-mentioned social capital promotion ideas to other villages may be biased. However, we still believe that there are both individuality and commonality in rural areas. We have explained the mechanism between participatory planning and social capital, which suggests that rural planning should change its thinking, take villagers as the main body, and bring villagers a harmonious settlement environment and social life as the goal. At the same time, planners should delve deeper into rural life, explore rural characteristics, and make use of the relevant elements of people and space systems according to local conditions.

For future research, we plan to explore more types of communities such as urban villages and old communities to further improve the relevant research content. In addition, the discussion of village social capital in this paper takes the public as a group, so it can confirm that collective activities, knowledge interaction, and social relations interact with each other. Future research can strengthen the long-term tracking of individuals on this basis to explain the interaction among the three in detail.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, X.L.; writing—original draft preparation, X.H.; writing—review and editing, L.C. and Y.L.; supervision, Y.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (42371206).

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Acknowledgments

The authors appreciate the editors’ and anonymous reviewers’ comments and suggestions.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Liu, Y.; Zang, Y.; Yang, Y. China’s rural revitalization and development: Theory, technology and management. J. Geogr. Sci. 2020, 30, 1923–1942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Liu, Y. Targeted poverty alleviation and its practices in rural China: A case study of Fuping county, Hebei Province. J. Rural Stud. 2022, 93, 430–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhao, J.; Yao, R.; Zhao, R.; Li, Y. Risk of Poverty Returning to the Tibetan Area of Gansu Province in China. Sustainability 2022, 14, 11268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, Y.; Liu, M.; Hu, S.; Wang, D.; Wang, J.; Wang, X.; Qader, S.; Cleary, E.; Tatem, A.J.; Lai, S. Who and which regions are at high risk of returning to poverty during the COVID-19 pandemic? Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2022, 9, 183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, A. The challenge in poverty alleviation: Role of Islamic microfinance and social capital. Humanomics 2014, 30, 76–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asadi, A.; Akbari, M.; Fami, H.S.; Iravani, H.; Rostami, F.; Sadati, A. Poverty alleviation and sustainable development: The role of social capital. J. Soc. Sci. 2008, 4, 202–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Portes, A. Social capital: Its origins and applications in modern sociology. In Knowledge and Social Capital; Routledge: London, UK, 2009; pp. 43–67. [Google Scholar]

- Keefer, P.; Knack, S. Social capital, social norms and the new institutional economics. In Handbook of New Institutional Economics; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2005; pp. 701–725. [Google Scholar]

- An, Y.; Zhou, G.H.; He, Y.H.; Mao, K.B.; Tan, X.L. Research on the functional zoning and regulation of rural areas based on the production-life-ecological function perspective: A case study of Changsha-Zhuzhou-Xiangtan area. Geogr. Res. 2018, 37, 695–703. [Google Scholar]

- Duany, A.; Plater-Zyberk, E. The second coming of the American small town. Wilson Q. 1992, 16, 3–51. [Google Scholar]

- Swinnen, J.F. Political reforms, rural crises, and land tenure in western Europe. Food Policy 2002, 27, 371–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damyanovic, D.; Reinwald, F. The “Comprehensive village renewal programme in Burgenland” as a means a strengthening the social capital in rural areas. Eur. Countrys. 2014, 6, 18–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radzuan, I.S.M.; Fukami, N.; Yahaya, A. Cultural heritage, incentives system and the sustainable community: Lessons from Ogimachi Village, Japan. Geografia 2014, 10, 130–146. [Google Scholar]

- Hong, J.Y.; Park, S.; Yang, H. In strongman we trust: The political legacy of the new village movement in South Korea. Am. J. Political Sci. 2023, 67, 850–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, J.; Yang, X. Sustainable development levels and influence factors in rural China based on rural revitalization strategy. Sustainability 2022, 14, 8908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griggs, D.; Stafford-Smith, M.; Gaffney, O.; Rockström, J.; Öhman, M.C.; Shyamsundar, P.; Steffen, W.; Glaser, G.; Kanie, N.; Noble, I. Sustainable development goals for people and planet. Nature 2013, 495, 305–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Su, K.; Hu, B.; Shi, K.; Zhang, Z.; Yang, Q. The structural and functional evolution of rural homesteads in mountainous areas: A case study of Sujiaying village in Yunnan province, China. Land Use Policy 2019, 88, 104100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Guo, Y.; Zhou, Y. Poverty alleviation in rural China: Policy changes, future challenges and policy implications. China Agric. Econ. Rev. 2018, 10, 241–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Q.; Li, E.; Yang, Y. Politics, policies and rural poverty alleviation outcomes: Evidence from Lankao County, China. Habitat Int. 2022, 127, 102631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Hao, X.; Cui, W.; Liu, H.; Gao, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Zhang, C.; Liu, A.; Dorairajoo, S. A preliminary study on the features of Chinese social work forces’ involvement in rural anti-poverty. China J. Soc. Work. 2023, 16, 239–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L. Poverty reduction in A transforming China: A critical review. J. Chin. Political Sci. 2022, 27, 771–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Wu, Z. Power and poverty in China: Why some counties perform better in poverty alleviation? J. Chin. Political Sci. 2022, 27, 319–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; Zhan, J.V. Repenetrating the Rural Periphery: Party Building Under China’s Anti-Poverty Campaign. J. Contemp. China 2023, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.G.; Zeng, X.X. From regional poverty alleviation and development to precision poverty alleviation: The evolution of poverty alleviation policies in China during the 40 Years of reform and opening-up and the current difficulties and countermeasures for poverty alleviation. Issues Agric. Econ. 2018, 8, 40–50. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Su, B.; Liu, Y. Realizing targeted poverty alleviation in China: People’s voices, implementation challenges and policy implications. China Agric. Econ. Rev. 2016, 8, 443–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Feng, X.; Wang, S.; Qiu, H. China’s poverty alleviation over the last 40 years: Successes and challenges. Aust. J. Agric. Resour. Econ. 2020, 64, 209–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, X.; Sarntisart, S.; Uddin, M.N. The Impact of Education Investment on Regional Poverty Alleviation, Dynamic Constraints, and Marginal Benefits: A Case Study of Yunnan’s Poor Counties. Economies 2023, 11, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Liu, J.; Zhou, Y. Spatio-temporal patterns of rural poverty in China and targeted poverty alleviation strategies. J. Rural Stud. 2017, 52, 66–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Wei, H. Annual Report on Poverty Reduction of China 2016; Social Sciences Academic Press: Beijing, China, 2016; Volume 50. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Y.; Liu, Y. The code of targeted poverty alleviation in China: A geography perspective. Geogr. Sustain. 2021, 2, 243–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Westlund, H.; Zheng, X.; Liu, Y. Bottom-up initiatives and revival in the face of rural decline: Case studies from China and Sweden. J. Rural Stud. 2016, 47, 506–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akpomuvie, O.B. Self-help as a strategy for rural development in Nigeria: A bottom-up approach. J. Altern. Perspect. Soc. Sci. 2010, 2, 88–111. [Google Scholar]

- Janusek, J.W.; Kolata, A.L. Top-down or bottom-up: Rural settlement and raised field agriculture in the Lake Titicaca Basin, Bolivia. J. Anthropol. Archaeol. 2004, 23, 404–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraser, E.D.; Dougill, A.J.; Mabee, W.E.; Reed, M.; McAlpine, P. Bottom up and top down: Analysis of participatory processes for sustainability indicator identification as a pathway to community empowerment and sustainable environmental management. J. Environ. Manag. 2006, 78, 114–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Liu, Y. Sustainable poverty alleviation and green development in China’s underdeveloped areas. J. Geogr. Sci. 2022, 32, 23–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourdieu, P. The forms of capital. In The Sociology of Economic Life; Routledge: London, UK, 2018; pp. 78–92. [Google Scholar]

- RogoÅ, S.; BaranoviÄ, B. Social capital and educational achievements: Coleman vs. Bourdieu. Cent. Educ. Policy Stud. J. 2016, 6, 81–100. [Google Scholar]

- Sensenbrenner, J.; Portes, A. Embeddedness and immigration: Notes on the social determinants of economic action. In The Sociology of Economic Life; Routledge: London, UK, 2018; pp. 93–115. [Google Scholar]

- Nahapiet, J.; Ghoshal, S. Social capital, intellectual capital, and the organizational advantage. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1998, 23, 242–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putnam, R.D. Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community; Simon and Schuster: New York, NY, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Krishna, A. Active Social Capital: Tracing the Roots of Development and Democracy; Columbia University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, N. Social Capital: A Theory of Social Structure and Action; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2002; Volume 19. [Google Scholar]

- Coleman, J.S. Social capital in the creation of human capital. Am. J. Sociol. 1988, 94, S95–S120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollenbeck, J.R.; Jamieson, B.B. Human capital, social capital, and social network analysis: Implications for strategic human resource management. Acad. Manag. Perspect. 2015, 29, 370–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Astone, N.M.; Nathanson, C.A.; Schoen, R.; Kim, Y.J. Family demography, social theory, and investment in social capital. Popul. Dev. Rev. 1999, 25, 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perkins, D.D.; Long, D.A. Neighborhood sense of community and social capital: A multi-level analysis. In Psychological Sense of Community: Research, Applications, and Implications; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2002; pp. 291–318. [Google Scholar]

- Prayitno, G.; Matsushima, K.; Jeong, H.; Kobayashi, K. Social capital and migration in rural area development. Procedia Environ. Sci. 2014, 20, 543–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falk, I.; Kilpatrick, S. What is social capital? A study of interaction in a rural community. Sociol. Rural 2000, 40, 87–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putnam, R.D. The prosperous community. Am. Prospect. 1993, 4, 35–42. [Google Scholar]

- Arrow, K.J. Observations on social capital. Soc. Cap. A Multifaceted Perspect. 2000, 6, 3–5. [Google Scholar]

- Garip, F. Discovering diverse mechanisms of migration: The Mexico–US stream 1970–2000. Popul. Dev. Rev. 2012, 38, 393–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feiock, R.C. The institutional collective action framework. Policy Stud. J. 2013, 41, 397–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Six, B.; Zimmeren Van, E.; Popa, F.; Frison, C. Trust and social capital in the design and evolution of institutions for collective action. Int. J. Commons 2015, 9, 151–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donaldson, J.A.; ZHANG, F.Q. Rural China in transition: Changes and transformations in China’s agriculture and rural sector. Contemp. Chin. Political Econ. Strateg. Relat. Int. J. 2015, 1, 51. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Q.; Huang, J.; Luo, R.; Liu, C. China’s labor transition and the future of China’s rural wages and employment. China World Econ. 2013, 21, 4–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saegert, S.; Thompson, J.P.; Warren, M.R. Social Capital and Poor Communities; Russell Sage Foundation: Manhattan, NY, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Du, Y.; Liu, P.; Ravenscroft, N.; Su, S. Changing community relations in southeast China: The role of Guanxi in rural environmental governance. Agric. Hum. Values 2020, 37, 833–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durston, J. Building social capital in rural communities (where it does not exist). In Proceedings of the Latin American Studies Association Annual Meetings, Chicago, IL, USA, 24–26 September 1998; pp. 24–26. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, B.; Liu, L.; Carter, C.J. Bridging social capital as a resource for rural revitalisation in China? A survey of community connection of university students with home villages. J. Rural Stud. 2022, 93, 254–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Wang, Y. Rural land engineering and poverty alleviation: Lessons from typical regions in China. J. Geogr. Sci. 2019, 29, 643–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, T.; Luo, Z.; Zhang, X. How do China’s villages self-organize collective land use under the background of rural revitalization? A multi-case study in Zhejiang, Fujian and Guizhou provinces. Growth Chang. 2024, 55, e12688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Liao, L. The active participation in a community transformation project in China: Constructing new forums for expert-citizen interaction. J. Chin. Gov. 2022, 7, 372–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, J.Z.; Zhu, Y. Social capital, guanxi and political influence in Chinese government relations. Public Relat. Rev. 2020, 46, 101885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilpatrick, S.; Field, J.; Falk, I. Social capital: An analytical tool for exploring lifelong learning and community development. Br. Educ. Res. J. 2003, 29, 417–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putnam, R.D. Making Democracy Work: Civic Traditions in Modern Italy; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Evans, P. Government action, social capital and development: Reviewing the evidence on synergy. World Dev. 1996, 24, 1119–1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabet, N.S.; Khaksar, S. The performance of local government, social capital and participation of villagers in sustainable rural development. Soc. Sci. J. 2024, 61, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, P.; Chen, J.; Gao, J.; Li, M.; Wang, J. What role(s) do village committees play in the withdrawal from rural homesteads? Evidence from Sichuan Province in Western China. Land 2020, 9, 477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceci, F.; Masciarelli, F.; Poledrini, S. How social capital affects innovation in a cultural network: Exploring the role of bonding and bridging social capital. Eur. J. Innov. Manag. 2020, 23, 895–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harriss, J. Social Capital Construction and the Consolidation of Civil Society in Rural Areas. 2001. Available online: https://www.lse.ac.uk/international-development/Assets/Documents/PDFs/Working-Papers/WP-1-159/WP16.pdf (accessed on 20 June 2024).

- Warner, M. Social Capital Construction and the Role of the Local State 1. Rural Sociol. 1999, 64, 373–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winters, P.; Corral, L.; Gordillo, G.A. Rural livelihood strategies and social capital in Latin America: Implications for rural development projects. Agric. Resour. Econ. 2001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lahiri Dutt, K.; Samanta, G. Constructing social capital: Self-help groups and rural women’s development in India. Geogr. Res. 2006, 44, 285–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]