Localized Canal Development Model Based on Titled Landscapes on the Grand Canal, Hangzhou Section, China

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. The Need for Localization of Cultural Landscapes

1.2. Conflicts between the Protection, Utilization, and Development of Cultural Landscapes along the Grand Canal, Hangzhou Section

1.3. Titled Landscapes with “Poetry and Painting Aesthetics”

1.4. Research Aim

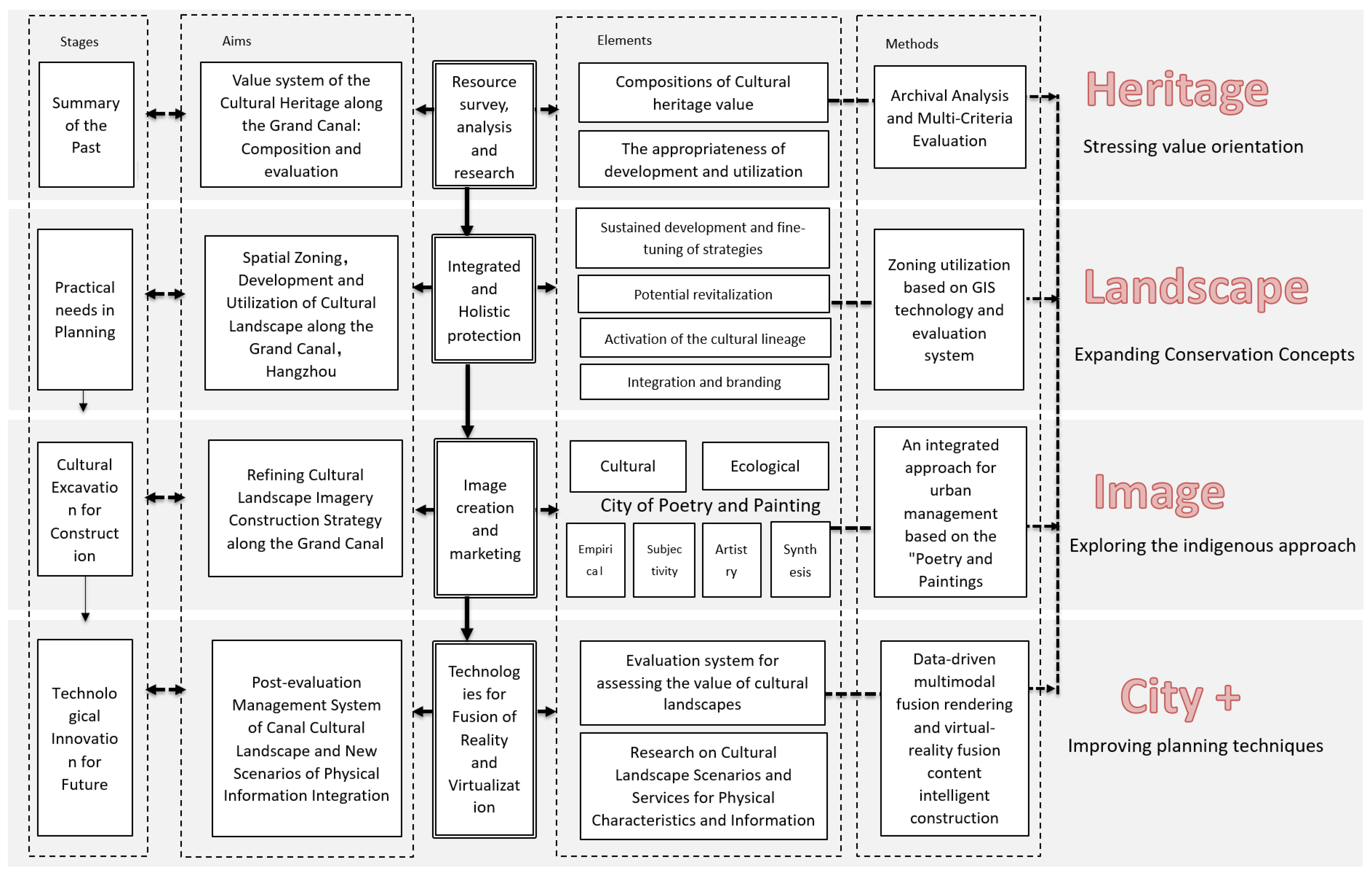

1.5. Research Framework

1.5.1. Resources Organization along the Hangzhou Section

1.5.2. Assessing the Value of the TCS

1.5.3. Strategies for TCS Landscape Imagery Construction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Literature Review on the Titled Landscape and the TCS

2.1.1. The Origin of the Titled Landscape and Its Spread in Pan-East Asia

2.1.2. Similar Paradigmatic Titled Landscapes around the World

2.2. Literature Review on the Value System of Titled Landscapes

2.2.1. Historical Value and Traceability Study of Titled Landscapes

2.2.2. Cultural (Spiritual) Value of Titled Landscapes

2.2.3. Spatial Patterns and Inheritance and Innovation of Titled Landscapes

3. Research Methodology of Evaluation

3.1. The Framework of Conservation and Developmental Indicators

3.1.1. Evaluation Indicators for the Values of the TCS

3.1.2. Conservation Indicators for the TCS

3.1.3. Developmental Indicators for the TCS

3.2. Research Methods and Design

3.2.1. Archival Analysis

3.2.2. Identification Technology of Cultural Landscape Features

Average Nearest Neighbor (ANN) Analysis

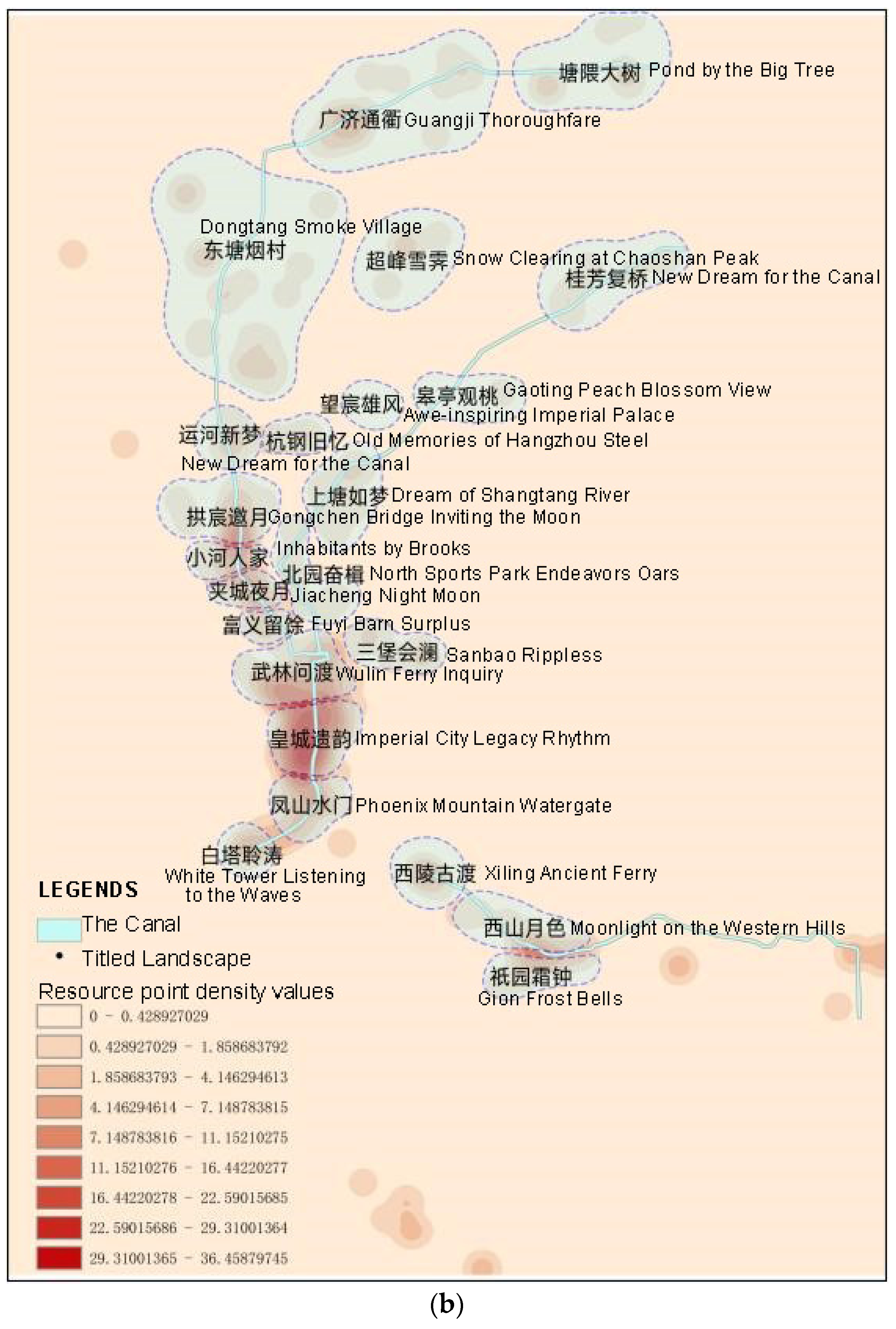

Nuclear Density Analysis

Clustering of Cultural Landscape Resource Site Analysis

3.2.3. Evaluation and Decision-Making Techniques

Refinement of the TCS

Comprehensive Assessment of the Conservation and Utilization Value of the “Ten Canal Scenes”

4. Results: Cultural Landscape Resources of the Grand Canal, Hangzhou Section

4.1. Summary of Data on Cultural Landscape Resources

4.2. Clustering of Cultural Landscape Resources

4.2.1. Average Nearest Neighbor Analysis

4.2.2. Nuclear Density Analysis

4.3. Spatial Location of Existing Titled Landscapes

5. Assessment Results: Coupling of the Conservation and Utilization Values

5.1. Evaluation Results of the Conservation Value: Refinement of the TCS

5.2. Assessment Results of the Utilization Value

5.3. Comprehensive Assessment Results of the Conservation and Utilization Values

5.4. Integrated Planning Propositions Based on the Assessment Results

5.4.1. Sustained Development and Fine-Tuning of Strategies

5.4.2. Potential Revitalization

5.4.3. Activation of the Cultural Lineage

5.4.4. Integration and Branding

6. Discussion

6.1. Review of the Aim for the TCS

6.2. Contemporary Drawings of the TCS

6.3. Historical Urban Landscapes (HUL) Approach and Conzen’s Urban Morphological Analysis

6.4. Shortcomings of Reductionist Methods in Cultural Landscape Heritage Conservation

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Appendix A.1. Average Nearest Neighbor (ANN) Analysis

| Section | No. | Chinese Title | Title of the Cultural Landscape | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hangzhou Tang (northern section) | 1 | 西浦斜阳 | Slanting Sunset of Xipu | 16 Scenes of Qixi [from Qing Dynasty], 10 Scenes of Bolu, 10 Scenes of the New Canal (2013) [69], new cultural landscapes |

| 2 | 长桥月色 | Moonlight on the Changqiao Bridge | ||

| 3 | 超峰雪霁 | Snow Clearing at Chaoshan Peak | ||

| 4 | 翠河秋色 | Autumn Color of the Cuihe River | ||

| 5 | 永明晚钟 | Evening Bell of Yongming | ||

| 6 | 北塘夜市 | Night Market of Beitang | ||

| 7 | 广济通衢 | Guangji Thoroughfare | ||

| 8 | 丁河红妆 | Red Makeup of Ding River | ||

| 9 | 五杭古集 | Ancient Gathering of Wuhang | ||

| 10 | 前溪风芦 | Wind of the Qianxi | ||

| Hangzhou Tang (southern section) | 1 | 夹城夜月 | Jiacheng Night Moon | [Ming] Eight Scenes of Hushu, [Yuan] Qiantang Ten Scenes, Tangqi Ten Scenes, Ten Scenes of the New Canal (2013) [69] |

| 2 | 陡门春涨 | Spring Rise of Steep Gate | ||

| 3 | 江桥暮雨 | Twilight Rain of River Bridge | ||

| 4 | 西山晚翠 | Evening Green of Xishan | ||

| 5 | 花圃啼莺 | Crowing Warblers in Flower Garden | ||

| 6 | 皋亭积雪 | Snow of Gao Ting | ||

| 7 | 白荡烟村 | Smoky Village of White Reeds | ||

| 8 | 半道春红 | Spring Red of Halfway | ||

| 9 | 北关夜市 | Night Market of North Juncture | ||

| 10 | 香积梵音 | Vanishing Sound of Xiangji Temple | ||

| 11 | 小河人家 | Inhabitants by Brooks | ||

| 12 | 拱宸邀月 | Gongchen Bridge Inviting the Moon | ||

| 13 | 运河新梦 | New Dream for the Canal | ||

| 14 | 义桥老街 | Old Street of Yixiao | ||

| Shangtang River | 1 | 桂芳复桥 | Osmanthus Fragrance by Ancient Bridge | New East Lake Ten Scenic Spots |

| 2 | 安平晚钟 | Anping Evening Bells | ||

| 3 | 断山残雪 | Broken Mountain Snow | ||

| 4 | 鼎湖玩月 | Dinghu Playing with the Moon | ||

| 5 | 藕洲泛艇 | Lotus Roots Island Panboat | ||

| 6 | 隆兴望月 | Longxing Looking at the Moon | ||

| 7 | 佛日禅踪 | Buddha’s Zen Trail | ||

| 8 | 段浜观梅 | Duanbang Guanmei | ||

| 9 | 枫林夕照 | Maple Grove Sunset | ||

| 10 | 桃堰渔火 | Peach Weir Fisherman’s Fire | ||

| 11 | 皋亭观桃 | Gaoting Peach Blossom View | New Shangtang Eight Scenic Spots | |

| 12 | 望宸雄风 | Awe-inspiring Imperial Palace | ||

| 13 | 上塘如梦 | Dream of Shangtang River | ||

| 14 | 北园奋楫 | North Sports Park Endeavors Oars | ||

| 15 | 双流抱亭 | Double Stream Beside Pavilion | ||

| 16 | 丁兰孝道 | Dinglan Filial Piety | ||

| 17 | 纤塘依君 | Xiantang by Your Side | ||

| 18 | 古松老桥 | Old Bridge by Ancient Pines | ||

| Zhonghe and Longshan Rivers | 1 | 吴山天风 | Winds in the Sky of Wushan | [Qing] West Lake 18 Scenes, New West Lake 10 Scenes (from 1984), the 3rd round of the West Lake 10 Scenes voting in 2007 [70] |

| 2 | 玉皇飞云 | Yuhuang Flying Clouds | ||

| 3 | 万松书缘 | Wansong Shuyuan | ||

| 4 | 凤岭松涛 | Phoenix Ridge Pines | ||

| 5 | 小营红巷 | Red Lane | New cultural landscape | |

| 6 | 夜坊清河 | Night Square Qinghe | ||

| 7 | 凤山水门 | Phoenix Mountain Watergate | ||

| 8 | 皇城遗韵 | Imperial City Legacy Rhythm | ||

| 9 | 八卦农作 | Bagua Farming | ||

| 10 | 白塔临江 | White Pagoda by the River | ||

| East Section of Zhejiang Canal | 1 | 菊山秋霁 | Chrysanthemum Hill Autumn Clearing | Xiaoshan Eight Scenes, Xiaoshan New Eight Scenes |

| 2 | 西陵古渡 | Xiling Ancient Ferry | ||

| 3 | 西山月色 | Moonlight on the Western Hills | ||

| 4 | 北岭烟光 | Beiling Smoke | ||

| 5 | 祈园霜钟 | Praying for the Garden Frost Bells | ||

| 6 | 樵楼晓角 | Dawn Corner of Woodcutter’s House | ||

| 7 | 杭坞龙湫 | Hangzhou Wall Dragon Marsh | ||

| 8 | 东岳揽胜 | East Mountain Embracing the Wonderful Scenery | Two scenes have been remodeled | |

| 9 | 梦笔亭驿 | Dream Brush Pavilion Inn |

| Titled Landscapes | Chinese Title | Historic Value (C.1.) | Cultural Value (C.2.) | Spiritual Value (C.3.) | Total | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C.1.1. | C.1.2. | C.1.3. | C.2.1. | C.2.2. | C.2.3. | C.3.1. | C.3.2. | |||

| lit. Wulin Ferry Inquiry | 武林问渡 | 0.99 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.40 | 0.40 | 0.00 | 1.00 | 5.79 |

| lit. Phoenix Mountain Watergate | 凤山水门 | 1.00 | 0.97 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.20 | 0.07 | 0.00 | 1.00 | 5.24 |

| lit. Imperial City Legacy Rhythm | 皇城遗韵 | 0.59 | 0.51 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 5.10 |

| lit. Gongchen Bridge Inviting the Moon | 拱宸邀月 | 0.15 | 0.14 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.40 | 0.27 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 4.96 |

| lit. Jiacheng Night Moon | 夹城夜月 | 0.16 | 0.12 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.20 | 0.07 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 4.55 |

| lit. Guangji Thoroughfare | 广济通衢 | 0.15 | 0.14 | 1.00 | 0.50 | 0.20 | 0.07 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 4.05 |

| lit. Fuyi Barn Surplus | 富义留馀 | 0.09 | 0.06 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.20 | 0.13 | 0.00 | 1.00 | 3.48 |

| lit. Qixi Night Mooring | 栖溪夜泊 | 0.06 | 0.07 | 0.33 | 0.50 | 0.20 | 0.20 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 3.36 |

| lit. Xiling Ancient Ferry | 西陵古渡 | 0.06 | 0.04 | 1.00 | 0.50 | 0.40 | 0.13 | 1.00 | 0.00 | 3.13 |

| lit. North Sports Park Endeavors Oars | 北园奋楫 | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.67 | 1.00 | 0.20 | 0.13 | 0.00 | 1.00 | 3.06 |

| lit. Broken Mountain Snow | 断山残雪 | 0.05 | 0.06 | 1.00 | 0.50 | 0.20 | 0.07 | 1.00 | 0.00 | 2.87 |

| lit. Inhabitants by Brooks | 小河人家 | 0.15 | 0.10 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.40 | 0.13 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 2.78 |

| lit. Gion Frost Bell | 祇园霜钟 | 0.15 | 0.15 | 0.67 | 0.50 | 0.20 | 0.07 | 1.00 | 0.00 | 2.73 |

| lit. Gaoting Peach Blossom View | 皋亭观桃 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.67 | 0.50 | 0.20 | 0.07 | 1.00 | 0.00 | 2.48 |

| lit. Pond by the Big Tree | 塘隈大树 | 0.07 | 0.06 | 0.33 | 0.50 | 0.20 | 0.20 | 1.00 | 0.00 | 2.37 |

| lit. Awe-inspiring Imperial Palace | 望宸雄风 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.67 | 1.00 | 0.40 | 0.20 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 2.27 |

| lit. Moonlight on the Western Hills | 西山月色 | 0.12 | 0.11 | 0.67 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.00 | 0.00 | 1.90 |

| lit. Dream of Shangtang River | 上塘如梦 | 0.07 | 0.08 | 0.67 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.00 | 1.82 |

| lit. White Tower Listening to the Waves | 白塔聆涛 | 0.12 | 0.11 | 1.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.23 |

| lit. Sanbao Ripples | 三堡会澜 | 0.06 | 0.04 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.00 | 1.10 |

| lit. Snow Clearing at Chaoshan Peak | 超峰雪霁 | 0.04 | 0.05 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.00 | 0.00 | 1.08 |

| lit. Dongtang Smoke Village | 东塘烟村 | 0.24 | 0.23 | 0.33 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.81 |

| lit. New Dream for the Canal | 运河新梦 | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.33 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.40 |

| lit. Old Memory of Hangzhou Steel Factory | 杭钢旧忆 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.33 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.38 |

| Titled Landscape | Chinese Title | Landscape Value (D1) | Social Value (D2) | Economic Value (D3) | Total | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| D.1.1. | D.1.2. | D.1.3. | D.1.4. | D.2.1. | D.2.2. | D.2.3. | D.3.1. | D.3.2. | |||

| lit. Gongchen Bridge Inviting the Moon | 拱宸邀月 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 42 |

| lit. Guangji Thoroughfare | 广济通衢 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 1 | 5 | 39 |

| lit. Wulin Ferry Inquiry | 武林问渡 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 3 | 38 |

| lit. Imperial City Legacy Rhythm | 皇城遗韵 | 1 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 3 | 1 | 5 | 34 |

| lit. North Sports Park Endeavors Oars | 北园奋楫 | 5 | 3 | 5 | 1 | 2 | 4 | 5 | 3 | 3 | 31 |

| lit. Fuyi Barn Surplus | 富义留馀 | 2 | 2 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 28 |

| lit. Xiling Ancient Ferry | 西陵古渡 | 3 | 2 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 28 |

| lit. Phoenix Mountain Watergate | 凤山水门 | 2 | 2 | 5 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 25 |

| lit. Jiacheng Night Moon | 夹城夜月 | 3 | 2 | 5 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 23 |

| lit. Osmanthus Fragrance by Ancient Bridge | 桂芳复桥 | 3 | 1 | 5 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 18 |

| Titled Landscape | Chinese Title | Conservation Indicator Score | Normalized Score 1 | Developmental Indicator Score | Normalized Score 2 | Normalized Total Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Imperial City Legacy Rhythm | 皇城遗韵 | 6.97 | 1.00 | 34 | 0.67 | 1.67 |

| lit. Wulin Ferry Inquiry | 武林问渡 | 5.79 | 0.70 | 38 | 0.83 | 1.53 |

| lit. Gongchen Bridge Inviting the Moon | 拱宸邀月 | 4.96 | 0.48 | 42 | 1.00 | 1.48 |

| Guangji Thoroughfare | 广济通衢 | 4.75 | 0.43 | 39 | 0.88 | 1.31 |

| Phoenix Mountain Watergate | 凤山水门 | 4.42 | 0.35 | 25 | 0.29 | 0.64 |

| Jiacheng Night Moon | 夹城夜月 | 4.63 | 0.40 | 23 | 0.21 | 0.61 |

| Fuyi Barn Surplus | 富义留馀 | 3.60 | 0.14 | 28 | 0.42 | 0.56 |

| North Sports Park Endeavors Oars | 北园奋楫 | 3.06 | 0.00 | 31 | 0.54 | 0.54 |

| Xiling Ancient Ferry | 西陵古渡 | 3.13 | 0.02 | 28 | 0.42 | 0.44 |

| lit. Osmanthus Fragrance by Ancient Bridge | 桂芳复桥 | 3.91 | 0.22 | 18 | 0.00 | 0.22 |

References

- Li, H.; Xiao, J. Analysis of the types of cultural landscapes and their constituent elements in China. Chin. Gard. 2009, 2, 90–94. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, H.; Rong, M.; Chen, X. Landscape culture and cultural landscape. Anhui Agric. Sci. 2012, 3, 1618–1620+1774. [Google Scholar]

- Değirmenci, T. The Contribution of Intangible Cultural Heritage to Outstanding Universal Value of UNESCO World Heritage Sites: An Analytical Evaluation on Cultural Landscapes. Ph.D. Thesis, Dokuz Eylul Universitesi, İzmir, Turkey, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Saleh, M. Value Assessment of Cultural Landscape in Alckas Settlement, Southwestern Saudi Arabia. Ambio A J. Hum. Environ. 2009, 29, 60–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, M.; Wang, Z.; Pan, Y. Research on the regional landscape characteristics of the Jianghan Plain based on the eight scenic systems of the lake and river network. Landsc. Archit. 2020, 27, 10–15. [Google Scholar]

- Blocker, B. Cultural Landscapes, Historic Preservation, and Cattle Ranches: A New Protocol for Documenting and Preserving Historic Working Cattle Ranches in Texas. Featuring a Case Study at the Dudley Brothers Ranch in Comanche. Texas Using TX-CLEVR (Texas Cultural Landscape Evaluation for Ranches). Ph.D. Thesis, The University of Texas at Arlington, Landscape Architecture, Arlington, TX, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Kıran, A.İ. Evaluation of Historical Orchards in the Istanbul Land Walls World Heritage Site within the Scope of Cultural Landscape. Master’s Thesis, Mimar Sinan Fine Arts University, Istanbul, Turkey, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Hun, L.C.; Shin, H.-S. A Basic Study on the Establishment of Evaluation Items for the Resiliency of Planting Landscape in Hahoe and Yangdong of World Cultural Heritage. J. Korean Inst. Tradit. Landsc. Archit. 2018, 36, 21–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ongyerth, G. Analysis and evaluation of the cultural landscape in city construction. Goals and methods of applied historical geography in the context of use of space and care of the landscape. Archaol. Nachrichtenblatt 2001, 6, 212–221. [Google Scholar]

- Gravis, I.; Nemeth, K.; Procter, J.N. The Role of Cultural and Indigenous Values in Geosite Evaluations on a Quaternary Monogenetic Volcanic Landscape at IhumAtao, Auckland Volcanic Field, New Zealand. Geoheritage 2017, 9, 373–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golestani, N.; Khakzand, M.; Faizi, M. Evaluation of the quality of participatory landscape perception in neighborhoods of cultural landscape to achieve social sustainability. Aestimum 2022, 81, 71–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrova, E.G.; Mironov, Y.V.; Aoki, Y.; Matsushima, H.; Ebine, S.; Furuya, K.; Petrova, A.; Takayama, N.; Ueda, H. Comparing the visual perception and aesthetic evaluation of natural landscapes in Russia and Japan: Cultural and environmental factors. Prog. Earth Planet. Sci. 2015, 2, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z. The New Concept of World Heritage Conservation—Cultural Landscape. Urban Plan. Newsl. 1995, 14, 12. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, M. The connotation of cultural landscape and its research progress. Prog. Geogr. Sci. 2000, 1, 70–79. [Google Scholar]

- Han, F. Exploring cultural landscapes in the forward march. Chin. Gard. 2012, 5, 5–9. [Google Scholar]

- Shan, J. From ‘cultural landscape’ to ‘cultural landscape heritage’ I. Southeast Cult. 2010, 2, 7–18. [Google Scholar]

- Shan, J. From ‘cultural landscape’ to ‘cultural landscape heritage’ II. Southeast Cult. 2010, 3, 7–12. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, N.; Yu, K.; Huang, Z. Focusing on the New Trend of Heritage Conservation: Cultural Landscapes. Hum. Geogr. 2006, 21, 61–65. [Google Scholar]

- Cai, Q. Cultural Landscape Conservation Based on Territory. Ph.D. Thesis, Southeast University, Nanjing, China, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Shi, X. Spatial Characteristics and Formation Mechanism of Traditional Regional Cultural Landscape. J. Tongji Univ. (Soc. Sci. Ed.) 2010, 21, 31–38. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, H.; Wang, H.; Fu, X. Research on the evaluation of cultural landscape value of traditional villages in southern Anhui region: Taking the example of Xihe Ancient Town in Wuhu County. J. Hunan City Coll. (Nat. Sci. Ed.) 2021, 30, 37–42. [Google Scholar]

- Han, J.; Wang, Y. Implications of Cultural Landscape Value Perception for the Protection of Traditional Villages in China. Urban Archit. 2022, 19, 89–94. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J. Spatial division of the Grand Canal ontology and the conservation and construction of ‘one axis and two sides’ of the ancient and modern canals. Mod. Urban Stud. 2021, 7, 2–6. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, Y.; Wang, Y. Research on the influence of canals on the urban spatial structure of Beijing—another discussion on the protection and construction strategy of the canal culture belt. Urban Dev. Res. 2019, 26, 44–48. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Q. Research on Linear Cultural Heritage Tourism Cooperation under the Vision of World Heritage: Taking the Beijing-Hangzhou Grand Canal as an Example; China Economic Press: Beijing, China, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, F.; Yang, L.; Shi, Y.; Luo, S. A study on the spatial scope and level of recreation in the cultural belt of the Grand Canal. Reg. Res. Dev. 2019, 38, 80–84. [Google Scholar]

- Ren, S. Research on Waterfront Landscape of Hangzhou Main City Section of Beijing-Hangzhou Canal. Ph.D. Thesis, Zhejiang University, Hangzhou, China, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Hangzhou Planning and Natural Resources Bureau; Hangzhou Urban Planning and Design Institute. Planning of Hangzhou Grand Canal National Cultural Park; Hangzhou Planning and Natural Resources Bureau, Hangzhou Urban Planning and Design Institute: Hangzhou, China, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- People’s Government of Zhejiang Province. General Rules for Land Space Control in the Core Monitoring Zone of the Grand Canal in Zhejiang Province. Zhejiang government office letter [2021] No. 9. February 22, 2021; People’s Government of Zhejiang Province: Hangzhou, China, 2021.

- Zhang, Y. Eight Views of Xiaoxiang; Shanghai Museum: Shanghai, China; Available online: https://auction.artron.net/paimai-art5173200238/ (accessed on 28 July 2024).

- Shang-Rui. Eight Views of Xiaoxiang in Early Qing Dynasty. Available online: https://amma.artron.net/observation_shownews.php?newid=1109730 (accessed on 28 July 2024).

- Zhu, J. The origin and flow of eight scenic spots. Beijing Political Consult. 1994, 8, 42. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, C.; Yin, Q. Name, Origin and Characteristics of “Eight Scenic Spots” and “Ten Scenic Spots”. Yichun Teach. Coll. J. 1997, 6, 73–76. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, M. Text, Image, and History: Multiple Conceptions of Time in the Song Painting Zhongxing Ruiyingtu. Fine Arts 2022, 12, 110–119. [Google Scholar]

- Ye, X. Album of Ten Scenes of West Lake; National Palace Museum: Taiwan, China, Painted between year 1253 and 1258.

- Lan, Y. Ten Scenes of West Lake. Available online: https://amma.artron.net/observation_shownews.php?newid=1109730 (accessed on 28 July 2024).

- Sun, Z. Imagery and Patterns—A Study of Landscape Centered on Ye Xiaoyan’s Album of Ten Scenes of West Lake. Fine Arts Des. 2023, 6, 041. [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka, M.; Tobikin, Y.; Aoki, Y. On the distribution of the eight scenic spots in Japan. Res. Randus 1999, 63, 246–248. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- Pan, Y.; Yu, S.; Wan, M. Research Progress of Pan-East Asian Area Eight- Scenes Culture. Chin. Landsc. Archit. 2022, 38, 121–126. [Google Scholar]

- Scarre, C. The Seven Wonders of the Ancient World. Class. Bull. 2001, 80, 125–127. [Google Scholar]

- Ali, M.A.M.; Kotb, A.A.; Elsherif, A.; Hisham, R.; Osama, M. Environmental’s Design Role in the Reviving and Preserving of Architectural Heritage Case Study (Catacombs of Kom El Shoqafa). Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2016, 225, 132–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vrancic, T. The Seven Engineering Wonders of the World. Gradevinar 2010, 62, 771–773. [Google Scholar]

- Shao, Y. History of Western Art: From the Seventeenth Century to the Present; Peking University Press: Beijing, China, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Fan, S. A Study of the Subject Matter of Vietnamese Tang Dynasty Poems. Ph.D. Thesis, Jilin University, Changchun, China, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Yi, R. Drifting and Returning: The Lyric Underpinnings of Song Dynasty Poems on Landscapes in Xiaoxiang. In Proceedings of the Second International Symposium on Song Dynasty Literature; Mo, L., Ed.; Jiangsu Education Publishing: Nanjing, China, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Q. The Xiaoxiang Pictures in the History of Chinese Paintings. Rongbaozhai 2004, 2, 184–199. [Google Scholar]

- Geng, X.; Li, X.; Zhang, J. Cultural awareness of Chinese gardens from the “eight scenic spots” in China. Chin. Gard. 2009, 25, 34–39. [Google Scholar]

- Horikawa, T. The Eight Scenes of Xiaoxiang—Japaneseized Forms Shown in Poetry and Paintin; Ran, Y., Translator; Yuelu Shuyuan Publishing House: Changsha, China, 2006. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- Rho, J.H. A Study on the Meaning and Coherence of Xiao and Xiang Rivers as a Text of Traditional Scenery. J. Korean Inst. Landsc. Archit. 2009, 37, 100–119. (In Korean) [Google Scholar]

- An, J.L. A Study on the Acceptance of Eight Views of the Xiao and Xiang Rivers (潇湘八景) and the Fashion Patterns of Korean Palgyeong Poetry. Korean Lit. Arts 2014, 13, 45–75. (In Korean) [Google Scholar]

- Lu, J. Aesthetic exploration of landscape titles in the traditional “eight scenic spots”. Chin. Character Cult. 2021, 4, 171–172. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, L. Study on the title of urban landscape. Chin. Famous Cities 2019, 6, 58–65. [Google Scholar]

- Ye, K.; Li, X. Research on the construction characteristics of the landscape system of the ancient city of Lishui Oujiang River Basin. Landsc. Archit. 2020, 27, 114. [Google Scholar]

- Da, T.; Du, Y. Morphological reflections on the landscape organization of traditional towns and cities—Taking Wuchang City of Ming and Qing Dynasties as an example. Chin. Gard. 2015, 31, 56–60. [Google Scholar]

- Li, C.; Du, C. Phenomenological Interpretation of the Eight Scenes of Bayu in the Ming and Qing Dynasties. Chin. Gard. 2014, 30, 96–99. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, M.; Peng, Y. Research on urban park system based on the theory of spectrum of recreational opportunities—Taking Ningguo City, Anhui Province as an example. Planner 2017, 33, 100–105. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, M.; Hu, Y.; Li, X.; Yao, Y. Research on scenic planning of Jingning County under the background of whole-area tourism. China Gard. 2020, 36, 142–146. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Z.; Shou, X.; Duan, J. Restoration and protection project of “two embankments and three islands” in Hangzhou West Lake. Landsc. Archit. 2012, 6, 52–57. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, J.; Song, L. Cultural Inheritance, Development and Transformation of the New Eight Scenic Spots in the New Millennium (2000–2015). Landsc. Archit. 2016, 10, 16–29. [Google Scholar]

- Deng, Y.; Liu, Y. Research on the origin and development of “eight scenic spots” culture. Guangdong Gard. 2012, 34, 11–19. [Google Scholar]

- Wanja, G.; Brande, A.; Zerbe, S. Inventory and evaluation of historic cultural landscapes—Example of the region ‘Ferch’ in Brandenburg. Naturschutz Und Landschaftsplanung 2007, 39, 337–345. [Google Scholar]

- Franch-Pardo, I.; Cancer-Pomar, L.; Napoletano, B.M. Visibility analysis and landscape evaluation in Martin river cultural park (Aragon, Spain) integrating biophysical and visual units. J. Maps 2017, 13, 415–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krajnik, D.; Petrovic Krajnik, L.; Dumbovic Bilusic, B. An Analysis and Evaluation Methodology as a Basis for the Sustainable Development Strategy of Small Historic Towns: The Cultural Landscape of the Settlement of Lubenice on the Island of Cres in Croatia. Sustainability 2022, 14, 1564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Li, H. Ephemerality and co-temporality in the conservation of historic towns and cities—Insights and reflections on urban historic landscapes. Urban Dev. Res. 2019, 26, 13–20. [Google Scholar]

- Fu, F.; Jiang, J.; Li, C. Co-temporality and ephemerality of cultural landscapes—A multi-dimensional perception of the heritage value composition of Xiangshan Mountain. Chin. Gard. 2020, 36, 18–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bi, X.; Han, F. Nature value and its aesthetic interpretation under the vision of environmental ethics. Landsc. Archit. 2022, 29, 112–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, W.; Lin, G. Research on the value type of cultural landscape. Landsc. Des. 2021, 2, 22–29. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y. Three Value Dimensions of Cultural Landscape Inspiration Taking World Heritage Cultural Landscape as an Example. Landsc. Archit. 2015, 8, 50–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y. Ten Scenes of the Canal Unveiled. Available online: https://hznews.hangzhou.com.cn/chengshi/content/2013-07/03/content_4794369.htm (accessed on 28 July 2024).

- Wang, Y. Hangzhou’s New “Ten Scenic Spots of West Lake” Selected for the Third Time. CCTV.com. Available online: https://news.cctv.com/china/20071028/100288.shtml (accessed on 28 July 2024).

- Zhang, H. Tang Dynasty. Passing through Linping Lake. Three Songs of Living Under Linping Mountain in Shen, Q. eds “Linping Record” volume 4 in early qing dynasty.

- Ying, C. The distant Linping “Ten Scenes of East Lake”. Available online: https://blog.sina.com.cn/s/blog_16a9c348e0102wr8a.html (accessed on 28 July 2024).

- Zhejiang Government. Map of Hangzhou. In A Complete Map of Zhejiang (Partial); Bibliothèque Nationale de France: Paris, France, Early Qing Dynasty. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, Q. Linping Town Map. In Book of Linping; Qiantang Ding’s Jiahui Hall: Hangzhou, China, 1884; ISBN 9787807158264. [Google Scholar]

- Dika, I.R.; Anicic, B.; Krklec, K.; Andlar, G.; Hrdalo, I.; Perekovic, P. Cultural landscape evaluation and possibilities for future development—A case study of the island of Krk (Croatia). Acta Geogr. Slov.-Geogr. Zb. 2011, 51, 129–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F. A study on the evolution of spatial structure of linear cultural heritage—with an account of the impact of tourism in it. Geogr. Geogr. Inf. Sci. 2019, 35, 133–140. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, S. Research on the Development of Historical Remains and Cultural Tourism Industry along the Grand Canal; Jilin University Press: Changchun, China, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Delakorda, K.T. The Authenticity of the Hidden Christians’ Villages in Nagasaki: Issues in Evaluation of Cultural Landscapes. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baotian-Nice. Illustration on the Theme of “Ten Scenes of Hangzhou Canals”. Available online: https://www.zcool.com.cn/work/ZNDI3NTA1NjQ=.html (accessed on 19 April 2024).

- Gauthier, P.; Gilliland, J. Mapping Urban Morphology: A Classification Scheme for Interpreting Contributions to the Study of Urban Form. Urban Morphol. 2006, 10, 41–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ünlü, T.; Bas, Y. Morphological Processes and the Making of Residential Forms: Morphogenetic Types in Turkish Cities. Urban Morphol. 2017, 21, 105–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conzen, M.P. How Cities Internalize Their Former Urban Fringes: A Cross-Cultural Comparison. Urban Morphol. 2009, 13, 29–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y. Management units of urban morphology: Significance, formation and application. City Plan. Rev. 2021, 45, 9–16. [Google Scholar]

- Marcus, L.; Pont, M.B.; Barthel, S. Towards a Socio-Ecological Spatial Morphology: Integrating Elements of Urban Morphology and Landscape Ecology. Urban Morphol. 2019, 23, 115–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lombardi, P.L.; Basden, A. Environmental Sustainability and Information Systems. Syst. Pract. 1997, 10, 473–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Primary Indicators | Secondary Indicators | Tertiary Indicators | Primary Indicators | Secondary Indicators | Tertiary Indicators |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conservation indication (C) | Historic value (C.1.) | Number of historical and cultural resource sites (C.1.1.) | Developmental indicators (D) | Landscape value (D.1.) | Integrity of preservation (D.1.1.) |

| Conservation level of historical and cultural resource sites (C.1.2.) | Diversity of elements (D.1.2.) | ||||

| Conservation level of the heritage sections (C.1.3.) | Spatial coherence (D.1.3.) | ||||

| Cultural value (C.2.) | Number of intangible cultural heritages (C.2.1.) | Landscape coherence (D.1.4.) | |||

| Number of types of intangible cultural heritages (C.2.2.) | Social value (D.2.) | Educational value (D.2.1.) | |||

| Conservation level of intangible cultural heritages (C.2.3.) | Service value (D.2.2.) | ||||

| Spiritual value (C.3.) | Availability of relevant traditional art works (C.3.1.) | Economic value (D.3.) | Usable value (D.3.1.) | ||

| Availability of relevant works of modern art (C.3.2.) | Shipping value (D.3.2.) | ||||

| Tourism value (D.3.3.) |

| Primary Indicators | Secondary Indicators | Tertiary Indicators |

|---|---|---|

| Historic value (C.1.) | Number of cultural landscape resource sites (C.1.1.) | The total number of resource points within the clusters was calculated by combining the resource points at each level within ArcMap10.8. |

| Conservation level of cultural landscape resource sites (C.1.2.) | National cultural heritage units: 5 points; Provincial cultural heritage units: 4 points; Municipal cultural heritage units and sites: 3 points; Other historical and cultural resource sites: historic buildings and industrial heritage and contemporary cultural landscape resource sites: 2 points. | |

| Conservation level of the heritage sections (C.1.3.) | Class I protected riverbank: 3 points; Class II protected riverbank: 2 points; Class III protected riverbank: 1 point; Non-heritage section of river: 0 points. | |

| Cultural value (C.2.) | Number of intangible cultural heritages (C.2.1.) | Number of intangible cultural heritages. |

| Number of types of intangible cultural heritages (C.2.2.) | Intangible cultural heritages are categorized into 10 categories in accordance with the Representative List of Intangible Cultural Heritage at the National Level (ICH) as follows: folklore, traditional music, traditional dance, traditional drama, opera, traditional sports, performing arts and acrobatics, traditional fine arts, traditional arts and crafts, traditional medicine, and folklore. Only the number of intangible heritage categories within the clusters is counted in this indicator. | |

| Conservation level of intangible cultural heritages (C.2.3.) | 2 points for items on the national ICH list; 1 point for items on other ICH lists; and 0 points for no ICH on site. | |

| Spiritual value (C.3.) | Availability of relevant traditional art works (C.3.1.) | With: 1 point; without: 0 points. |

| Availability of relevant works of modern art (C.3.2.) | With: 1 point; without: 0 points. |

| Primary Indicators | Secondary Indicators | Tertiary Indicators |

|---|---|---|

| Landscape value (D.1.) | Integrity of preservation (D.1.1.) | The extent to which the components of the cultural landscape have been maintained in terms of their composition and during their development. |

| Diversity of elements (D.1.2.) | This refers to cultural landscapes that are themselves diverse in structures and functions, reflecting the complexity of the assemblage. | |

| Spatial coherence (D.1.3.) | Whether the building heights and skyline within the cultural landscape meet the height requirements of the Grand Canal zoning district and the requirements for the view corridors of important nodes along the Grand Canal. | |

| Landscape coherence (D.1.4.) | Whether the cultural landscape’s architectural style and volume are in harmony with the landscape along the canal and the traditional architectural style, and whether they meet the aesthetic requirements for the important interfaces along the Grand Canal. | |

| Social value (D.2.) | Educational value (D.2.1.) | This refers to whether the cultural, scientific, artistic, historical, and other values can enhance the social, cultural, and spiritual cultivation of visitors through tourism and publicity. |

| Service value (D.2.2.) | Whether it can provide diversified public services, thereby enhancing the quality of life for residents along the canal. | |

| Economic value (D.3.) | Usable value (D.3.1.) | This refers mainly to the economic value of the canal’s cultural landscape that can be generated directly by its continued use. |

| Shipping value (D.3.2.) | Whether the cultural landscape of the canal can enhance the function of flood control and drainage conservation, optimize allocation of water resources, promote shoreline conservation and wharf service enhancement, etc., so as to enhance the navigability of the canal waterway and contribute to the regional shipping value. | |

| Tourism value (D.3.3.) | This refers to whether the cultural landscape can enhance the tourism infrastructure and supporting services with cultural and tourism integration to develop high-quality canal tourism routes and products, or to build a canal cultural exchange platform. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Dong, W.; Zhang, C.; Han, W.; Wang, J. Localized Canal Development Model Based on Titled Landscapes on the Grand Canal, Hangzhou Section, China. Land 2024, 13, 1178. https://doi.org/10.3390/land13081178

Dong W, Zhang C, Han W, Wang J. Localized Canal Development Model Based on Titled Landscapes on the Grand Canal, Hangzhou Section, China. Land. 2024; 13(8):1178. https://doi.org/10.3390/land13081178

Chicago/Turabian StyleDong, Wenli, Chenlu Zhang, Wenying Han, and Jiwu Wang. 2024. "Localized Canal Development Model Based on Titled Landscapes on the Grand Canal, Hangzhou Section, China" Land 13, no. 8: 1178. https://doi.org/10.3390/land13081178

APA StyleDong, W., Zhang, C., Han, W., & Wang, J. (2024). Localized Canal Development Model Based on Titled Landscapes on the Grand Canal, Hangzhou Section, China. Land, 13(8), 1178. https://doi.org/10.3390/land13081178