Abstract

With the rapid aging of the global population, China’s old urban areas, especially historical urban areas, are facing a more severe aging situation. In the context of heritage protection, the development and regeneration of historical urban areas are restricted. They usually face the aging and decay of housing, infrastructure, and public service facilities, which are harmful neighborhood environmental factors to the health development of older adults. Since the World Health Organization adopted “healthy aging” as a development strategy to deal with population aging, the mental health of older adults has become an increasingly important public health issue. A growing body of research demonstrates the positive impact of blue spaces (including oceans, rivers, lakes, wetlands, ponds, etc.) on older adults’ mental health, yet evidence on the potential of blue spaces in a historical environment to promote mental health among older adults remains limited. Therefore, exploring the neighborhood impact of blue space on the mental health of older adults has become a new entry point to provide an age-friendly environment for older adults in the ancient city. This study uses multi-source data such as community questionnaire data, remote sensing images, urban street view images, and environmental climate data of the ancient city of Suzhou, to extract a variety of blue space quantitative indicators, and uses the hierarchical linear model and mediation effect model to explore the neighborhood impact of blue space exposure in the historical environment on older adults, to try to explore the impact path and formation mechanism behind it. The result is that exposure to neighborhood blue space in Suzhou’s historic urban area is significantly related to the mental health of older adults. Additionally, neighborhood blue space exposure improves the mental health of older adults by relieving stress and promoting physical activities and social interaction. The health effects of neighborhood blue space exposure vary among elderly groups with different age and income stratifications, and have a greater impact on the healthy lifestyle and mental health of older adults in younger and lower-income aging groups. Based on a multidisciplinary theoretical perspective, this study enriches the empirical literature on the impact of blue space on the mental health of older adults in historical environments and provides a scientific basis for the regeneration planning of “healthy neighborhoods” and “healthy aging” in historical urban areas.

1. Introduction

The proposal of the “healthy aging” development strategy has made the mental health issues of older adults, which have been neglected, become an increasingly important public health issue. A survey by the World Health Organization (WHO) shows that the main psychological problems that cause the disease burden of older adults in China are depression, suicide, and Alzheimer’s disease [1]. Due to tourism, gentrification, and external forces, historical urban areas as cultural heritage are facing the threat of decline, including population loss, social desertification, and population aging [2,3,4,5]. In historic urban areas where a large number of elderly people gather, the emphasis on the protection of cultural heritage has sacrificed the needs of local residents [6]. The remaining residents live in a historical environment with old residentials, imperfect facilities, congested road traffic, and fragile social networks [2,5,7]. These negative environmental factors have an adverse impact on older adults’ residential satisfaction, thus becoming a source of stress and posing a threat to the mental health and well-being of older adults [8,9]. This is due to the physiological characteristics of older adults, which increases the length of time they stay in the neighborhood and increases their dependence on neighborhood resources. Therefore, it is necessary to explore the potential of the neighborhood environmental element in historical urban areas to create a restorative neighborhood living environment, and take into account the interests of older adults in the renewal of historical urban areas.

There is evidence of the health benefits of being close to blue space (including oceans, rivers, lakes, wetlands, ponds, etc.), such as reducing heat-related mortality [10], relieving stress [11], and supporting physical activities that enhances human health [12], and the particularly positive effects on mental health [13,14,15,16]. At the same time, the functions of water systems such as farming, fishing, transportation, and national defense have influenced the evolution of regions and cities [17]; therefore, many historical cities originate from the coast or near large inland water bodies and have abundant water systems [17,18]. Therefore, exploring the potential of blue spaces in promoting mental health and well-being and finding ways to alleviate the above mental health threats for older adults in historical urban areas has become an important research issue. In this study, we focus on three key questions. Firstly, do blue spaces in decaying historic urban areas benefit the mental health of older adults? Secondly, from the perspective of human-environment interactions, what environmental factors can influence the outcomes of blue space visits among older adults in historic urban areas? Thirdly, through which mediating pathways do blue spaces in historic urban areas interact with older adults’ mental health?

2. Literature Review

2.1. Blue Space and Mental Health of Older Adults

There is a small but growing body of evidence that exposure to blue space in later life has potential benefits for mental health [19]. Older adults can experience emotional well-being, restorative psychological effects, and greater well-being from regular interactions with blue space [20]. However, despite the widespread recognition of these benefits, there is a relative paucity of research exploring the blue space in detail compared to “green spaces” such as city parks, woods and forests, or even private gardens [21,22,23,24]. And most previous surveys and studies focusing on blue space are conducted in developed regions and countries such as Europe, the United States, and Australia [25]. Although urbanization and population aging are developing rapidly in Asia, there is a lack of research on Asia [26]. We also found no research on the mental health effects of blue space in historic cities with unique urban water textures.

2.2. Influence Indicators of Blue Space on Mental Health

The purpose of early studies is mainly to explore the correlation between mental health and blue space [20,27]. Subsequent studies found that simply considering the correlation between the two ignored the interactive relationship between individuals and the environment, so the interaction index between people and the environment is included in the influencing indicator system [26,28,29]. Overall, the mental health evaluation results are used as the dependent variable, the conditions of the individual and social influencing factors are used as control variables, the blue space characteristic indicators are used as independent variables, and the interaction indicators are used as mediating variables to establish a connection [30,31,32]. The measurement of blue space characteristics mainly involves objective factors such as area, coverage, proportion, and accessibility [19,33]. However, simply linking the blue space characteristics obtained by objective measurement with health data, does not reflect the impact of the true character of blue space on mental health. [34]. We have no way of knowing what kind of blue space can better promote the mental health and well-being of older adults [35]. Therefore, according to the theory of environmental behavior, this study emphasizes incorporating people’s subjective feelings about the quality of blue space into the measurement of blue space characteristics.

2.3. The Mechanism of Blue Space’s Impact on the Mental Health of Older Adults

According to existing research, the effects of the exposure to natural environments in the neighborhood environment (such as water bodies) on mental health can be divided into direct effects and potential pathways. Most studies have proven the direct positive effects of the exposure to natural environments on human health and well-being, mainly including three aspects: sensory recovery, stress relief, and mood improvement [32,36,37]. Based on previous research [15,38,39,40], the potential pathways of blue space on the mental health of older adults can be summarized into the following three types:

- (1)

- Alleviating the harm to older adults from the living environment: as age increases, older adults group becomes more sensitive to the external living environment [41,42]. Long-term exposure to extreme temperatures may threaten the mental health and well-being of older adults, and sudden temperature changes can significantly aggravate depressive symptoms in older individuals [43]. At the same time, some studies have shown that compared with green spaces, blue spaces have higher specific heat capacities, which are more conducive to mitigating local urban thermal environments and giving full play to the urban cold island effect [44].

- (2)

- Restoration path: according to the Stress Reduction Theory (SRT) [45] and Attention Restoration Theory (ART) [46] of environmental psychology, the natural environment can reduce mental stress and repair attention for older adults, by restoring functions (relieving stress, fatigue, and regulating negative emotions) or reducing environmental noise [47,48].

- (3)

- Constructive path: chronic diseases such as hypertension and diabetes are caused by the decline of body function in older adults and lack of exercise [25]. Residents in areas with high accessibility to neighborhood blue space are more likely to engage in physical activities, such as walking and jogging, which can stimulate the secretion of happy hormones in the human body, thereby affecting physical and mental health [25]; at the same time, blue space provides a spatial carrier for older adults to socialize and participate in collective affairs, which can increase older adults’ sense of community identity and cohesion, thereby affecting the physical and mental health of older adults [15,25,33].

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Research Area and Data Sources

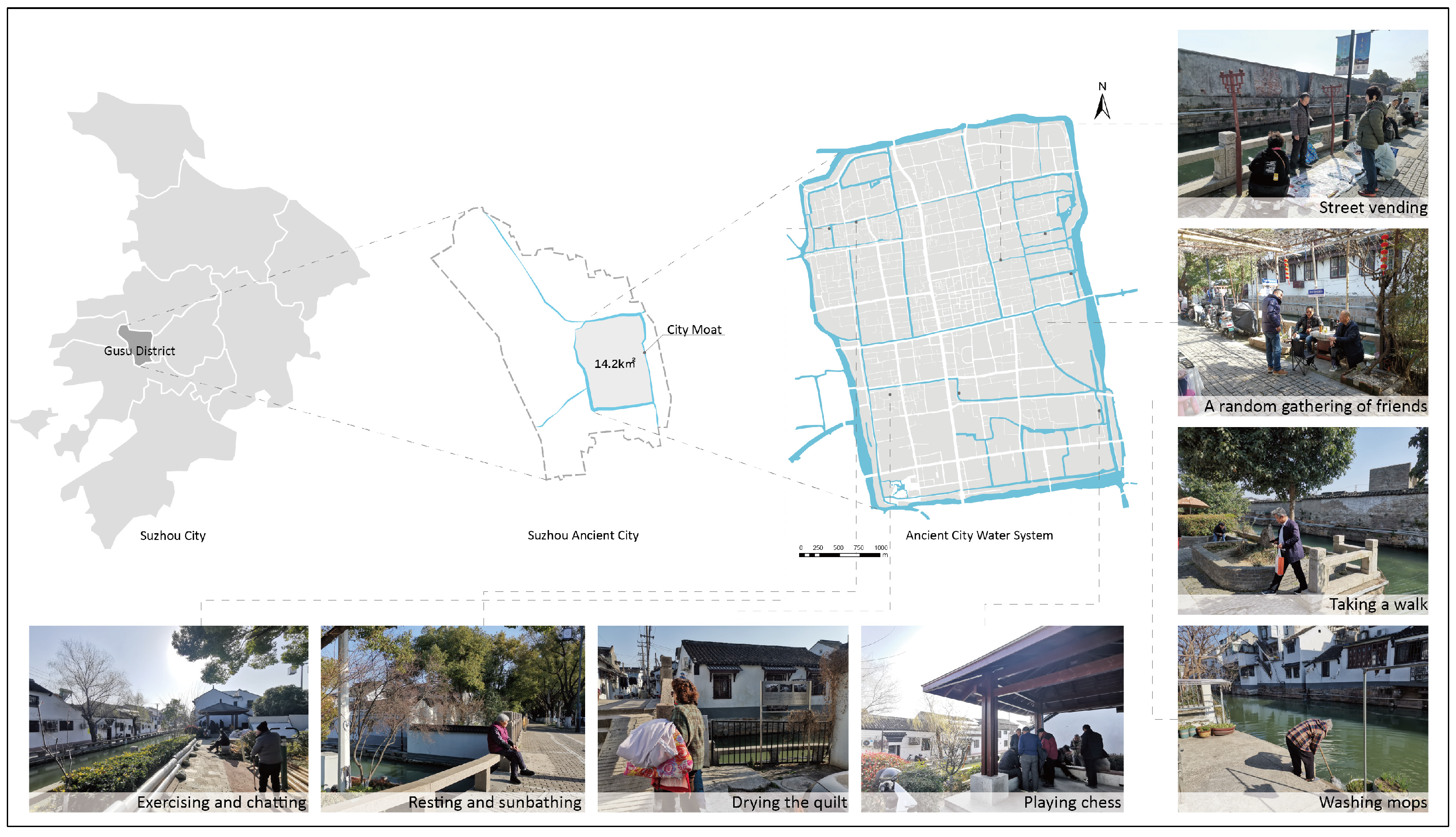

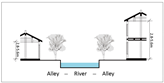

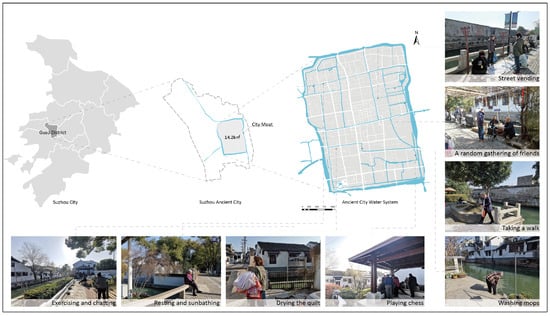

The scope of this study is the ancient city of Suzhou, which is 14.2 square kilometers, surrounded by a 15.8 km long moat (Figure 1). The total river area is 36.76 hectares of the ancient city of Suzhou and there are various forms of bridges which span large and small water alleys, and more than 600 streets and lanes which constitute the unique water city style. The “double chessboard” pattern of parallel water and land is a typical feature of Suzhou’s traditional urban space and pattern. The rivers and streets have a clear sense of order in the longitude and latitude directions, and together with the 54 neighborhoods of “streets in front and rivers in back”, which form the unique traditional texture of the ancient city of Suzhou. The river system plays the role of “setting city shape with water” and “water nourishing the city”, determining the urban form and planning structure, and historically playing a role in framing and stabilizing the ancient city.

Figure 1.

Map of Suzhou ancient city’s water system and photos of waterfront activities for seniors. Source: Author’s own photographs.

Suzhou is one of the first national historical and cultural cities in China and a unique example of urban construction in the new era of “protecting ancient cities and building new districts” [49]. For heritage protection and burden reduction, the population, factories, enterprises, and government agencies are moved from the ancient city to the new district. However, with the construction of the new district, it has gradually been able to provide residents with a good living environment, high-quality educational resources, and a higher return on real estate investment, which has led to the migration of some high–middle income groups and young people from the ancient city. The shrinkage of population size and structure has caused the aging of the population in the ancient city to become more prominent, and the proportion of older adults is much higher than the average level in the city. Judging from the distribution of aging population in various districts in Suzhou, in Gusu District, where the ancient city of Suzhou is located, the proportion of older adults population over 65 years old reached 25.17%, which is higher than the 16.96% of the entire Suzhou City [50].

The main data come from the community questionnaire survey (Table A1) of the ancient city conducted in June 2022. The sampling method for the survey [51] is as follows: (1) Select communities where the proportion of elderly people is greater than 10% and the main factors related to social areas are high, covering traditional residential communities, danwei compound communities (a form of community centered on the function of ‘work’ and organized with living facilities and various welfare facilities, and mostly built during the period of China’s socialist planned economy), ordinary commercial housing communities (with independent property rights and properties), and villa communities. According to the proportion of different types of housing area, a total of 15 communities are selected, which are relatively representative. It includes 4 traditional residential communities (Historical District Community, Changmen Community, Daoqian Community, and Dinghui Temple Community), and 6 danwei compound communities (West Street Community, Beiyuan Community, Yangcanli first Community, Yangcanli second Community, Yulan Community, and Guihua Community), and 3 ordinary commercial housing communities (Jinshi Community, Dongyuan Community, and Wangshixiang Community), and 2 villa communities (Tainan Community and Taohuawu Community). (2) Based on the proportion of the permanent population in the Sixth Census, stratified proportional sampling is used to determine the number of questionnaires in each community. (3) The Kish method is used to determine the list of surveyed households and conduct one-on-one interviews with older adults in the households. A total of 1000 questionnaires are distributed this time, with 733 valid questionnaires. Due to the rigorous sampling method, the sample is highly representative.

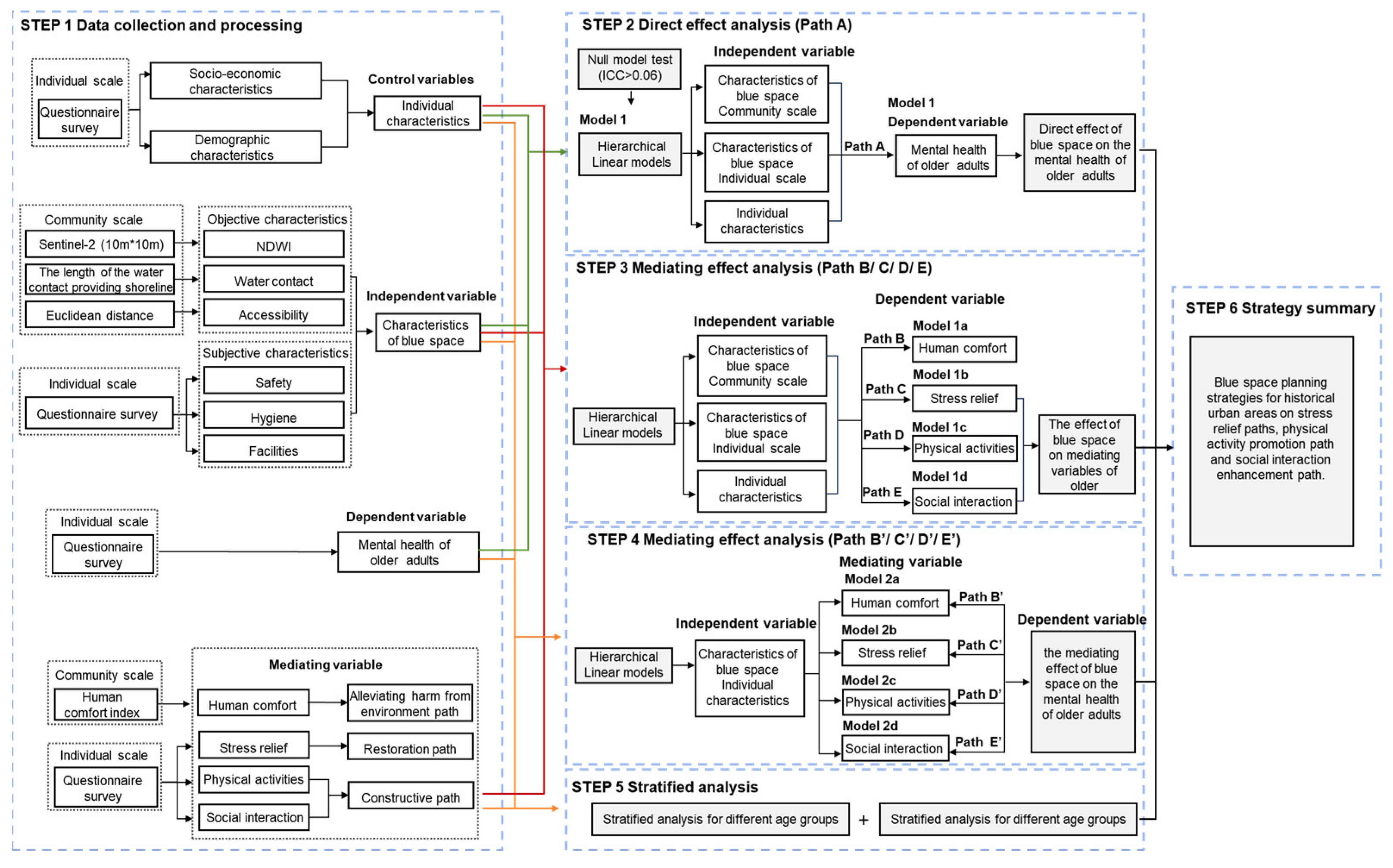

3.2. Research Framework

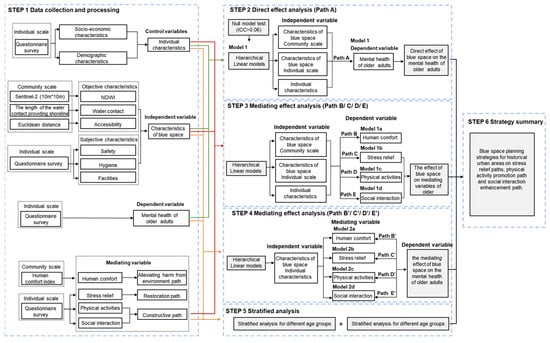

It has been shown that there are three mediating pathways that indirectly determine differences in the extent to which the natural environment influences the mental health of older adults, including the path of alleviating harm from environment, the path of restoration, and the path of construction power (Figure 2). Since these three ways come from the interaction between blue space and people, the measurement of blue space is carried out from two dimensions: the objective attribute of blue space itself and the subjective perception of people after the interaction between blue space and people. Firstly, for the path to alleviate harm from environment, we select the human comfort created by the blue space environment in the community as the measurement index. Secondly, for the restoration path, we select stress relief among older adults as the measurement index. Thirdly, for the constructive path, we select the physical activity duration and social interaction situation of older adults in the blue space environment as measurement indicators.

Figure 2.

Research framework. Source: Author’s own drawing.

The objective attributes of blue space are mainly reflected at the community level. It includes three indicators: objective quantitative characteristics, water contact, and accessibility. The subjective perception characteristics of blue space are mainly reflected at the level of personal feelings. For subjective perception characteristics, respondents are asked to evaluate three aspects: water environment safety, hygiene, and supporting facilities. In addition, different age, gender, socio-economic status, and other factors have different preferences and opportunities for using blue spaces in historical urban areas, resulting in differences in the mental health effects of blue spaces [52]. Therefore, this article sets 6 control variables, including gender, age, marital status, education level, monthly income level, and length of residence.

3.3. Dependent Variables

At present, there is no unified standard for measuring mental health status in academia. Common mental health scales include the Warwick Edinburgh Mental Health Scale (SWEMWBS) [53] and the General Health Questionnaire (GHQ-12) [54], Health Survey Short Form (SF-36) [55], etc. This article uses the Chinese short version of the Warwick Edinburgh Mental Health Scale (SWEMWBS) [56] to investigate the mental health status of respondents. There are 7 items in this scale, which evaluate the mental health status of the respondent from ‘feeling optimistic/feeling valuable/in a relaxed mood/being able to handle problems well/thinking clearly/being close to others/being able to make decisions on one’s own’. Each question is scored on a scale from 1 (never) to 5 (all the time), with a maximum score of 35. And the higher score represents the better mental health level.

3.4. Independent Variables

This article selects indicators from two aspects: objective attributes and subjective perception characteristics of blue space [33,52]. Objective attributes include three aspects: the objective quantitative characteristics of the water environment, and accessibility. Among them, the objective quantitative characteristics are measured by the Normalized Water Index (NDWI). And the Sentinel-2 satellite remote sensing data on 27 July 2022 (10 m × 10 m) are used to calculate the average value within the 1 km buffer zone of the community boundary. Then, the variable ‘water contact’ refers to the riverside areas that provide opportunity for older adults to contact with water environment, whether it is through direct contact (e.g., washing, fishing and boating) with the water or not (e.g., walking by the river), so it is measured by the length of the riverside shoreline that allows older adults to have water contact. And accessibility is measured by the distance to the nearest body of water, which is the Euclidean distance between the center of the neighborhood where a residence is located and the nearest river, lake, or wetland. The subjective perception characteristics are obtained from a questionnaire survey, asking respondents to evaluate blue space from three aspects: (1) whether the water environment near you is safe; (2) whether the water quality of the water near you is good (clear and no smell); (3) are there good facilities of the water environment near you (e.g., parking, sidewalks, toilets, handicap facilities, etc.). Using a Likert-5 scale, the answers are five options: ‘strongly agree’, ‘agree’, ‘indifferent’, ‘disagree’ and ‘strongly disagree’, representing a score of 5–1, respectively.

3.5. Mediating Variable

According to existing research [33,38], this study uses physical activity duration, stress, social interaction, and human comfort as potential mediating pathways to study the impact of blue space on the mental health of older adults. The measurement data of mediating variables are obtained through a combination of questionnaire interviews and objective measurements. The four mediating variables are all continuous variables. Firstly, the respondent’s physical activities are measured as ‘Your average daily fitness (including walking) duration is _ hours’. Secondly, the following 3 questions are used to measure stress levels: ‘Feeling stress that affected your work and daily activities in the past month’, ‘Experienced emotional problems in the past month’ and ‘Unable to concentrate on anything in the past month’ we assign values from 5 to 1, respectively (always, often, sometimes, rarely, and never). Thirdly, social interaction includes social interaction, community recognition, neighbor trust, and is evaluated through the following 5 questions: ‘Have you made new friends when you are exposed to the water environment?’, ‘Have you participated in public social activities that occurred around the water environment?’, ‘Do you know many people in the community?’, ‘Do you relate well with people in your community?’ and ‘Is your community cohesive?’. ‘Strongly agree’, ‘agree’, ‘moderate’, ‘disagree’, and ‘strongly disagree’ are assigned values of 5 to 1, respectively. Finally, the mitigation of harm from older adults’ living environment is measured by human body comfort. Human comfort is a biometeorological index that evaluates human comfort under different climate conditions from a meteorological perspective based on the principle of heat exchange between the human body and the near-earth atmosphere [57]. When meteorological factors such as temperature, humidity, wind speed, and solar radiation change, the comfort of the human body will also change [58]. The climate characteristics of Suzhou and Shanghai are similar, so this article cites the calculation formula and human comfort index applicable to Shanghai’s climate characteristics in the second half of the year as reference standards (Table 1) [59]. They are calculated as follows:

DI = 1.8T + 0.145RH (1.8T-26) + A1(T-33) + 0.134T + 27

Table 1.

Correspondence table between human comfort index and human body feeling.

In the formula: DI is the human comfort index; T is the environment temperature (°C); RH is the relative humidity value (0.01); A1 is the wind direction correction coefficient in the second half of the year, and the value of A1 is 0.10 [60].

3.6. Control Variables

The control variables select residents’ socio-economic status and demographic attribute variables, such as age, gender, education, personal monthly income, marital status, length of residence. Table A2 shows the statistical description of the dependent variables, independent variables, mediating variables, and control variables.

3.7. Statistical Analysis Methods

3.7.1. Hierarchical Linear Model

This study uses R (4.3.1) and RStudio (2023.06.2+561) to carry out hierarchical linear model analysis. The hierarchical linear model fully considers the nestedness of data and can accurately calculate the contribution of elements at different geographical levels. In this study, the first level is 733 individual respondents, and the second level is 15 surveyed communities. The formula is as follows:

In the formula: individual i (1~733) is nested in community unit j (1~15); is the mental health score of i in community j; is an individual-level variable; is a community-level variable; α is the intercept;is the community-level residual; is the individual-level residual.

3.7.2. Mediating Effect Analysis

The mediation effect means that the independent variable X (neighborhood blue space) affects the dependent variable Y (mental health) through the mediating variable Μ. The hierarchical linear mediating effect model is a combination of a hierarchical linear model and a mediation effect model. It can explore the impact of variables at different levels under a hierarchical linear data structure, especially the impact of high-level independent variables on individual-level dependent variables, which strengthens the role of mediating effects. This study uses this model to explore each influence path and uses Sobel to test its mediating effect. The specific formulas are as follows:

In the formula: represents the mediating variable.

4. Results

4.1. Participant Characteristics

All participant characteristic variables are shown in Table 2. Among 1000 older adults who participated in the questionnaire survey and interviews, valid questionnaire and interview information are obtained from 733 participants. The gender representation of the sample is relatively balanced, with 51.4% of the participants identifying as female (n = 377) and 48.6% identifying as male (n = 356). Older adult participants comprised three age groups, of which 48.2% are in the 60–70 age group (n = 353). There is variability in the marital status of respondents, with 67.4% of older adults indicating that they are currently married (n = 494). In terms of educational level, 74.6% have received education beyond primary school (n = 547), but 25.4% has no schooling (n = 186). With regard to income distribution, a large proportion (47.9%) report a monthly income of less than CNY 1370 (n = 351). Regarding the length of residence, 35.6% of participants have lived in the ancient city of Suzhou for more than 10 years (n = 261). In terms of the socio-economic characteristics of the participants, this study has a rich and diverse sample.

Table 2.

Summary of participant socio-economic characteristics statistics.

4.2. The Impact and Path of Neighborhood Blue Space on the Mental Health of Older Adults

Since the independent variables () and mediating variables () in the model both include community-level and individual-level factors, the model includes three hierarchical linear mediating effect types: 2-2-1 type, 2-1-1 type, and 1-1-1 type. Firstly, establish a null model test with () as the dependent variable, and calculate the corresponding intraclass correlation coefficient ICC that is 0.2182 (>0.06), community-level blue space factors explain 21.82% of the differences in the mental health of older adults. Therefore, it is necessary to use hierarchical linear models to analyze the data to control errors caused by the incomplete independence of nested data. When individual-level and community-level variables are included, the likelihood ratio drops from 3599.79 (in the null model) to 3489.21, proving that the blue space in the historical environment can effectively explain the heterogeneity of older adults’ mental health at the community level and it is suitable for building a hierarchical linear model.

Model 1 in Table 3 is the baseline model, which only includes independent variables and control variables, including gender (β = 0.827, p < 0.05), age (β = 0.692, p < 0.01), and marital status (β = 0.341, p < 0.01), education (β = −0.437, p < 0.05), income (β = −0.308, p < 0.1), and length of residence (β = −0.799, p < 0.01) are all significantly related to the mental health of older adults. Water contact (β = 4.658, p < 0.05), hygiene (β = 0.632, p < 0.01), and supporting facilities (β = 1.049, p < 0.01) are significantly positively correlated with the mental health of older adults.

Table 3.

Test coefficient of the mediating effect of blue space on the mental health of older adults.

Models 1a~1d in Table 4 use human comfort, stress relief, physical activities, and social interaction as dependent variables to conduct hierarchical linear regression analysis. NDWI (β = 0.396, p < 0.01) and water contact (β = 0.138, p < 0.01) are significantly positively correlated with human comfort, and accessibility (β = −0.508, p < 0.01) is significantly negatively correlated with human comfort. Water contact (β = −2.832, p < 0.1), safety (β = 0.964, p < 0.01), hygiene (β = −0.483, p < 0.1), supporting facilities (β = −0.570, p < 0.01) are significantly related to stress relief. NDWI (β = 0.764, p < 0.05), safety (β = 0.768, p < 0.05), hygiene (β = −0.685, p < 0.01) are significantly correlated with physical activities. Safety (β = 0.294, p < 0.05) and supporting facilities (β = 0.074, p < 0.05) are significantly positively correlated with social interaction.

Table 4.

The effect of blue space on mediating variables of older adults.

Models 2a~2d in Table 3 test the effect of the independent variable and four mediating variables (human comfort, stress relief, physical activities, and social interaction) on the dependent variable at the same time. The path of human comfort path in model 2a is not significant. In model 2b, water contact (β = 3.915, p < 0.01), hygiene (β = 0.877, p < 0.1), and supporting facilities (β = 0. 853, p < 0.01) are positively related to the mental health of older adults, and the stress relief path (β = −0. 340, p < 0.01) is significantly negatively correlated with the mental health of older adults. In model 2c, hygiene (β = 0.813, p < 0.01) and physical activities (β = 0.868, p < 0.01) are significantly positively correlated with the mental health of older adults, and the physical activities path (β = 0.857, p < 0.01) is significantly positively correlated with the mental health of older adults. In model 2d, supporting facilities (β = 0.660, p < 0.01) are significantly positively correlated with the mental health of older adults, and the social interaction path (β = 0.186, p < 0.01) is significantly positively correlated with the mental health of older adults. The Sobel test is used to determine whether the above variables played a mediating role. The results are that stress relief (Z = 5.020, p < 0.05), physical activities (Z = 2.696, p < 0.05) and social interaction (Z = 2.927, p < 0.05) passed the test.

In the historical environment, due to the high density of water networks, indicators such as NDWI and accessibility that reflect the objective quantitative characteristics of blue space have not shown a significant impact on the mental health of older adults. In contrast, due to the different spatial relationships between the unique traditional dwellings and rivers in the historical urban area of Suzhou, the water contact of the water system affects older adults’ exposure to blue space and thus affects their mental health. Compared with the objective quantitative characteristics of blue space, variables such as hygiene conditions and supporting facilities that reflect subjective quality characteristics have a more significant impact on the mental health of older adults. Clean and odorless water, a clean and tidy waterfront environment, and corresponding waterfront recreational facilities can affect the duration, frequency, and opportunities for older adults to move, stay, and socialize in waterfront areas. At the same time, blue space has the potential for mental healing, thereby relieving stress, restoring mental fatigue, and regulating negative emotions [45], and then affecting the mental health of older adults.

4.3. Stratified Analysis

4.3.1. Differences in the Impact of Blue Spaces in Historical Environments on the Mental Health of Elderly People of Different Ages

The differences in the health effects of community blue space environments are further measured between different age groups. The ICCs of the null model for the age group from 60 to 70 years old and the age group above 70 years old are 0.279 and 0.173, respectively, indicating that the overall difference in the mental health level of the two age groups comes from the differences between communities to a certain extent.

Taking model 3 as the baseline model, the total effect of the blue space of the historical environment on the self-rated mental health of older adults was explored. In the blue space index, water contact, accessibility, hygiene conditions, and supporting facilities are significantly related to the self-evaluated mental health of the age group from 60 to 70 years old, while hygiene and supporting facilities are significantly correlated to the self-evaluated mental health of the age group above 70 years old. Models 3a~3d introduce human comfort, stress relief, physical activities, and social interaction. And the results show that the two paths of stress relief and physical activities play a mediating effect in the age group from 60 to 70 years old, and the coefficient of water contact is smaller than the coefficient of model 3. Among the age group above 70 years old, the three paths of stress relief, physical activities and social interaction play a mediating effect; meanwhile, the hygiene and supporting facilities in the social interaction path are both smaller than the coefficients of model 3.

The social interaction path (β = 0.57, p < 0.01) has a significant positive correlation with the mental health of the age group above 70 but does not exert a partial mediating effect on the age group from 60 to 70. The stress relief path has a significant positive correlation with the mental health of both the age group from 60 to 70 and the age group above 70, which has a higher mediating effect on the age group from 60 to 70 (β = 0.580, p < 0.01) than that on the age group above 70 (β = 0.247, p < 0.05). The physical activities path has a significant negative correlation with the mental health of both the age group from 60 to 70 and the age group above 70, which has a higher mediating effect on the age group above 70 (β = −1.240, p < 0.01) than that on the age group from 60 to 70 (β = −0.645, p < 0.01) (Table 5 and Table 6).

Table 5.

Analysis of the impact of blue space in historical environment on the mental health of older adults aged 60–70 years old.

Table 6.

Analysis of the impact of blue space in historical environment on the mental health of older adults over 70 years old.

The Sobel test is further used to test the mediating effect. In the age group from 60 to 70, stress relief plays a partial mediating effect impact in terms of water contact (Z = 2.276, p < 0.01) and supporting facilities (Z = 2.811, p < 0.01) on the mental health of older adults; meanwhile, the physical activities path plays a partial mediating effect impact in terms of water contact (Z = 2.299, p < 0.01) and supporting facilities (Z = 2.106, p < 0.01) on the mental health of older adults. Among the age group above 70, social interaction plays a partial mediating role in the impact in terms of hygiene (Z =2.626, p < 0.01) and supporting facilities (Z = 4.332, p < 0.01) on the mental health of older adults. Due to differences in physical and mental levels in different life stages, the age group from 60 to 70 has more physical strength and energy for leisure activities and social interactions in the water environment than the age group above 70, so waterfront activities are more frequent and longer. Compared with the age group above 70, at the same time, they prefer to go out independently to organize or participate in stress-relieving activities in a blue space environment. In the course of the research, it was learnt that this was due to some age-unfriendly risk factors that still exist in blue spaces or on the way to blue spaces, which may cause older adults to fall and get injured, thus causing a certain amount of stress relief and mood swings. Therefore, the age group above 70 are more reluctant to go out to a blue space, and they prefer to seek psychological relief at home by talking to their children or relatives.

4.3.2. Differences in the Impact of Blue Spaces in Historical Environments on the Mental Health of Elderly People with Different Incomes

According to the monthly income samples of 525,000 workers in Suzhou in 2019, the average monthly salary in Suzhou is about CNY 8088, and the median average salary is about CNY 5600, and the minimum wage standard in Suzhou is CNY 1370. Therefore, we select the value CNY <1370, CNY 1370–5600, and CNY >5600 as the classifying criteria for low, medium, and high income. Considering the sample size, the group with a monthly personal income higher than CNY 1370 is selected as the middle–high income group for stratified analysis to explore the differential impact of the blue space environment on the mental health of different income groups. The ICC of the null model for the low-income group and the middle–high income group are 0.298 and 0.120, respectively, indicating that the overall difference in mental health level of the two groups originated from differences between communities to a certain extent.

Model 4 is the baseline model, which explores the total effect of the blue space environment on the self-rated mental health of elderly groups with different incomes. The results show that the water contact, hygiene, and supporting facilities indicators of blue space are significantly related to the mental health level of low-income elderly people, while the hygiene conditions and supporting facilities indicators of blue space are significantly related to the mental health level of middle–high income elderly people. Model 4a introduces four mediating paths: human comfort, stress relief, physical activities, and social interaction. Among low-income and middle–high income groups, the three paths of stress relief, physical activities, and social interaction all play partial mediating effects. Among low-income groups, stress relief (β = 0.898, p < 0.01) is significantly positively correlated with older adults’ self-rated mental health, while physical activities (β = −0.816, p < 0.01) and social interaction (β = −1.230, p < 0.01) are significantly negatively correlated with it. Among the middle–high income groups, stress relief (β = 0.161, p < 0.05) is significantly positively correlated with older adults’ self-rated mental health, while physical activities (β = −0.828, p < 0.01), and social interaction (β = −0.159, p < 0.01) show a significant negative correlation. It indicates that for both low-income and middle–high income groups, promoting stress relief, physical activities and social interaction are the intermediate mechanisms through which blue space in historical environments affects the mental health of older adults (Table 7 and Table 8).

Table 7.

Analysis of the impact of blue space in historical environment on the mental health of low-income (<1370 CNY) elderly people.

Table 8.

Analysis of the impact of blue space in historical environment on the mental health of middle-high-income (>1370 CNY) elderly people.

The Sobel test is further used to test the mediating effect. Among low-income groups, the stress relief path exerts a partial mediating effect in terms of water contact (Z = 2.987, p < 0.01), hygiene (Z = 2.757, p < 0.01), and public facilities (Z = 3.113, p < 0.01); the physical activities path plays a partial mediating effect in terms of water contact (Z = 3.931, p < 0.01), hygiene (Z = 1.929, p < 0.01), and public facilities (Z = 2.071, p < 0.01); the social interaction path exerts a partial mediating effect in terms of public facilities (Z = −2.835, p < 0.01). Among middle–high income groups, the three paths of stress relief, physical activities, and social interaction all play a partial mediating effect on the mental health of older adults in terms of public facilities, and the Sobel test results are 2.792, 2.978 and 2.208, respectively. It illustrates that neighborhood blue space in the historical environment has a greater impact on the mental health of low-income elderly groups than that of middle–high-income elderly groups.

The good water accessibility, hygiene conditions, and public facilities of the neighborhood blue space provide a good place for older adults of the low-income group living in the historical environment to decompress outdoors. However, older adults of the middle–high-income groups are only limited by public facilities. This is because the daily life style and the scope of activities of middle–high-income groups are different from those of low-income groups. Affluent seniors usually choose some professional recuperation or scenic spots at a certain distance from home for leisure and relaxation, while for the blue spaces within the neighborhood, only some daily fitness will be carried out to reduce stress, so the degree of dependence on the community blue space is low.

5. Discussion

5.1. Summary of Findings

We believe that the current study is the first to examine older adults’ exposure to blue spaces, specifically freshwater environments, in relation to self-reports of mental health in a historic urban area. Also, as far as we know, this is the first study to explore these issues in an Asian context. Regarding the research question: blue space in declining historical urban areas has a significant positive correlation with the mental health of older adults, which can mitigate the negative impact on the health and well-being of older adults caused by the deterioration of physical spaces in historic urban areas, to a certain extent. This is generally consistent with findings published elsewhere. For example, studies in Ireland [27] and Scotland [19] find that exposure to both community freshwater and coastal blue spaces have a positive impact on the mental health of older adults. Meanwhile, a study in Hong Kong finds that viewing blue space from home is associated with older adults’ SRH satisfaction [26]. Experimental research in mainland China has found that the natural environment, especially blue space landscapes, can help recover from stress relief, which is beneficial to the mental health development of older adults [61].

Regarding the second research question, we find that after controlling for key sociodemographic factors such as gender, age, marital status, education level, income level, and length of residence, the environmental quality factors such as water contact, hygiene, and supporting facilities of blue space exposure are significantly and positively associated with older adults’ self-reported mental health and well-being. For the impact of the objective attributes of blue space in Suzhou’s historic city on the mental health of older adults, due to the unique and dense water grid layout of the ancient city [49], compared with the general residents of inland cities, the residents of ancient cities are more likely to be exposed to the blue space environment in different forms (accidental exposure, indirect exposure, direct exposure). Therefore, the impact of NDWI and walking distance to the nearest blue space on the mental health outcomes of older adults is not significant. However, due to the unique river alley spatial texture pattern of the ancient city of Suzhou, different water–land relationships such as “one river and two alleys”, “one river and one alley”, “river without alley “ will provide residents with different levels of openness and sharing (Table 9). This is also consistent to a certain extent with the latest experimental results based in Guangzhou, China, which prove that being close to a water body but not being able to contact the water has no significant impact on the mental health of older adults [33]. As for the subjective perception characteristics of blue spaces in Suzhou’s historic urban areas, because most of the blue spaces in Suzhou’s ancient city are in the form of long and narrow rivers, and the water flow is gentle, older people have less worries about safety when exposed to blue spaces. However, due to the narrowness of the river channel in the ancient city, it is inconvenient to use large-scale mechanical desilting facilities, resulting in increasing silt at the bottom of the river, increasing pollution in the river, and the emergence of unpleasant odors in some parts of rivers [62]. Therefore, the water quality and hygiene conditions of rivers have a certain impact on the frequency of visits to blue spaces by older adults. At the same time, the strict implementation of the ancient city style protection strategy in the past thirty years has resulted in a lack of daily maintenance and improvement in the waterfront coastline, aging infrastructure, and lack of updating of public service facilities [63]. However, in recent years, with the upsurge of urban regeneration gradually sweeping the ancient city, such as Pingjiang Road Historic District Community, Changmen Community, Daoqian Community and Dinghui Temple Community have all undergone more systematic urban regeneration and transformation [64,65], which have better facilities and riverside landscapes. During the survey process, older adults in these communities have more preferences for choosing blue spaces when going out for leisure activities. Additionally, previous research has also shown that high-quality facilities are a key driver of blue space visits for older adults [26].

Table 9.

Analysis of spatial factors affecting water contact of the blue space in the ancient city.

As for our last research question, we find that blue space in historical environments mainly improves the mental health of older adults through three pathways: reducing stress, promoting physical activities, and social interaction. Among them, in the stress relief path, water contact, hygiene and facilities of the blue space are positively correlated with the mental health of older adults. Interview data with older adults in the Vancouver area of Canada indicate that older adults have expressed widespread appreciation for the tranquility of blue spaces, particularly as places for relaxation, contemplation, and spiritual connection with relatives [66]. In the physical activities path, the hygiene of blue spaces becomes the main factor that determines whether to encourage or inhibit older adults from going out for leisure activities. In the study of Hong Kong, the hygiene situation does not have an impact on the willingness to visit blue spaces. This may be related to the difference in the overall public environmental hygiene level between the declining ancient city and metropolis. In the path of social interaction, the availability of public facilities in blue space is an important factor in determining the willingness of older adults to engage in social interaction. The importance of facility quality in nature access has also been shown in previous research [26]. In addition, human comfort does not show a significant mediating effect on the mental health of older adults, which may be due to the small size of the ancient city of Suzhou, where the effect of water on the local microenvironment does not differ significantly across the region.

5.2. Limitations and Prospects

Firstly, the significant correlation obtained based only on cross-sectional data may not fully reveal the causal relationship between the variables. Future research can combine follow-up survey data. Secondly, the mediating variables (fitness duration, stress relief level, and social interaction level) and mental health level used in this article are self-evaluation indicators. Future research can use instruments such as pedometers, handheld GPSs, and psychological instruments to collect objective data on these mediating variables. Nonetheless, our findings complement research findings on the health benefits associated with blue space exposure, providing experimental evidence that infers the beneficial effects of blue space on mental health in older adults. Thirdly, the accessibility data in this study uses Euclidean distance to reflect the average distance at the community level. Due to ethical restrictions on older adults’ respondents, the application of wearable GPS instruments to a group of older adults has not been realized. Future research can consider other alternative methods to obtain the actual distance of older adults to the blue space. Fourthly, the influence of factors such as personal eating habits, genetic constitution, and behavioral preferences, as well as the cultural and personal life experience factors of blue space in the historical environment, are not considered. Future research can include relevant factors in the questionnaire survey.

6. Conclusions

In summary, blue spaces in historical environments, such as the ancient city of Suzhou, are significantly related to the mental health of older adults; neighborhood blue spaces improve the mental health of older adults by reducing stress and promoting physical activities and social interaction; the mental health effects of blue spaces vary among elderly groups of different age groups and income groups, and have a greater impact on the mental health of younger and lower-income elderly groups. Our findings suggest that blue spaces should figure more prominently in health policy and urban planning discourses regarding older people. Therefore, we combine the experimental results, starting from the repair force pathway (reducing stress) and the constructive pathway (promoting physical activities and social interaction), and summarize the development goals of blue space to promote the mental health of older adults, then propose the planning strategies of blue space in historical urban areas to achieve the health goals of older adults.

Firstly, the occurrence of the repair force pathway utility is more dependent on the water contact behavior of older adults. Water itself has diverse spiritual symbols and aesthetic forms for human beings. Whether it is a majestic river or a quiet and clear lake, it can have a spiritual healing effect. Therefore, improving the cultural service capabilities of blue space does not focus on the form and method of shaping water landscapes, while the main development strategy is how to improve the convenience for the older adult groups to see, listen to, and touch the water. The key points are on the aging-friendly design of urban water contact spaces and the barrier-free design of pedestrian facilities and landscape facilities, including barrier-free walking, viewing, and water playing. The barrier-free traffic environment and walking accessibility of the waterfront space can be improved by supplementing transportation connections, wheelchair ramps, and barrier-free vertical elevators. Visual corridors for viewing the water can be ensured and the system of barrier-free viewing facilities can be improved. By optimizing the waterfront interface at the macro level and restricting the height of waterfront buildings and landscapes at the micro level, the chances of older adults group encountering the water landscapes can effectively increase. The service radius and fairness of landscape facilities can also increase, by connecting the 15 min walking life circle of the community, arranging key water contact spaces in different zones, and connecting the trail junctions between the main waterfront areas and urban areas.

Secondly, the occurrence of the constructive path mainly depends on the occurrence of physical activities such as sports, recreation, as well as neighborhood interaction activities. According to the theory of environmental behavior, stimulation in specific places can awaken people’s sensory responses, thereby producing specific behaviors. Therefore, the creation of waterfront space in Suzhou’s ancient city should focus on how to establish a waterfront space structure system that adapts to older adults’ travel methods, activity types, environmental concerns, etc., including the construction of a transportation structure based on trails, the establishment of a community life-oriented functional structure and the construction of a landscape structure guaranteed by safe activities. The horizontal connection with surrounding functional areas and service facilities should be strengthened, and a quick connection between senior residences and waterfront spaces should be established. The walking and visual accessibility of the water environment should also be enhanced, by integrating a slow-traffic system that runs through the historic city. Through the renewal of the historic city, fitness facilities, rest facilities, hygiene facilities, and signage guidance facilities, etc., are provided, which strengthen the diversity and rational layout of waterfront public space service facilities, create a safer, more comfortable, and pleasant walking environment, and meet the needs of older adults for jogging, walking, Tai Chi, square dancing, and other fitness activities, as well as community public affairs, gatherings, and other social interaction activities. A service network among nearby communities should be developed, integrating some cultural, sports, entertainment, health care, and rehabilitation service functions with waterfront spaces, so that the geographical scope of the community conforms to the travel habits of older adults and satisfies the needs of nearby activities.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Z.Y.; methodology, Z.Y.; validation, J.Y. and Z.Y.; formal analysis, Z.Y. and S.C.; investigation, Z.Y.; resources, Z.Y. and S.C.; data curation, S.C.; writing—original draft preparation, Z.Y.; writing—review and editing, J.Y.; visualization, S.C.; supervision, J.Y.; project administration, J.Y.; funding acquisition, J.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research has been supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of 14th Five-Year Plan of the Ministry of Science and Technology (Grant No. 2022YFC3800302) and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 52278049).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

Author Shenglan Chen was employed by the company Architects & Engineers Co., Ltd. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Interview form.

Table A1.

Interview form.

| Interview Form |

| This study aims to investigate the neighborhood effect of blue space on the mental health of older adults in the historical environment. If you agree to participate in this study, you need to participate in a questionnaire survey of about 20 minutes. We guarantee that the information of this survey will only be used for research needs, all materials are confidential, and your information will not be disclosed to any organization or individual. Thank you very much for your cooperation! 1. Your gender is A. Male B. Female 2. Your age is A. 60–70years old B. 71–80 years old C. Above 80 years old 3. Your current marital status A. Unmarried B. Married C. Divorced/Widowed 4. Your education level is A. None/Preschool education B. Primary school C. Middle school (including technical secondary school) D. University (including junior college) E. Postgraduate 5. Your monthly income range A. Below 1370 CNY B. 1370–5600 CNY C. Above 5600 CNY 6. How long have you lived in the neighbourhood? A. Less than 6 months B. 6 months–3 years C. 3–10 years D. More than 10 years 7. You can’t concentrate on doing things A. Always B. Often C. Sometimes D. Rarely E. Never 8. You suffer from insomnia due to anxiety A. Always B. Often C. Sometimes D. Rarely E. Never 9. You don’t feel that you have played a role in things A. Always B. Often C. Sometimes D. Rarely E. Never 10. You feel nervous A. Always B. Often C. Sometimes D. Rarely E. Never 11. You feel unhappy and depressed A. Always B. Often C. Sometimes D. Rarely E. Never 12. You think you are a worthless person A. Always B. Often C. Sometimes D. Rarely E. Never 13. You can’t feel happy in general A. Always B. Often C. Sometimes D. Rarely E. Never 14. The water environment near you is safe A. Strongly agree B. Agree C. Indifferent D. Disagree E. Strongly disagree 15. The water quality near you is good (clear and odorless) A. Strongly agree B. Agree C. Indifferent D. Disagree E. Strongly disagree 16. The water environment near you has good facilities (e.g. parking lots, sidewalks, toilets, barrier-free facilities, etc.) A. Strongly agree B. Agree C. Indifferent D. Disagree E. Strongly disagree 17. Have you felt the influence of stress in your work and daily activities in the past month? A. No B. Rarely C. Sometimes D. Often E. Always 18. Have you encountered emotional problems in the past month? A. No B. Rarely C. Sometimes D. Often E. Always 19. Have you been unable to concentrate on anything you do in the past month? A. No B. Rarely C. Sometimes D. Often E. Always 20. Your average daily fitness time (including walking) 21. Have you made new friends when you are in contact with water environment? A. Strongly agree B. Agree C. Indifferent D. Disagree E. Strongly disagree 22. Have you participated in public social activities around water environment? A. Strongly agree B. Agree C. Indifferent D. Disagree E. Strongly disagree 23. Do you know many people in the community? A. Strongly agree B. Agree C. Indifferent D. Disagree E. Strongly disagree 24. Do you get along well with people in the community? A. Strongly agree B. Agree C. Indifferent D. Disagree E. Strongly disagree 25. Is your community cohesive? A. Strongly agree B. Agree C. Indifferent D. Disagree E. Strongly disagree |

Table A2.

Descriptive statistics of the variables.

Table A2.

Descriptive statistics of the variables.

| Variable Type | Variable Hierarchy | Variable Name | Descriptions | Mean | S.D. | Min | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Independent variables ) | Community level | NDWI | Continuous variable | 0.041 | 0.033 | 0.002 | 0.108 |

| Community level | Water contact | 1961.253 | 1129.805 | 494.376 | 4363.757 | ||

| Community level | Accessibility | 234.733 | 89.315 | 64.330 | 376.330 | ||

| Individual level | Safety | Measured on a scale from 1‘strongly disagree’ to 5 ‘strongly agree’ | 3.823 | 0.650 | 2.000 | 5.000 | |

| Individual level | Hygiene | 3.468 | 0.880 | 2.000 | 4.000 | ||

| Individual level | Facilities | 3.278 | 0.983 | 1.000 | 4.000 | ||

| Dependent variables ) | Individual level | Mental health | Measured on a scale from 1‘never’ to 5 ‘all the time’ | 2.476 | 0.423 | 1.570 | 4.290 |

| Mediating variable ) | Community level | Human comfort | Continuous variable | 90.327 | 3.856 | 83.200 | 95.300 |

| Individual level | Stress relief | Measured on a scale from 1‘never’ to 5 ‘always’ | 1.690 | 0.596 | 1.000 | 3.333 | |

| Individual level | Physical activities | Continuous variable | 0.583 | 0.600 | 0.000 | 4.000 | |

| Individual level | Social interaction | Measured on a scale from 1‘strongly disagree’ to 5 ‘Strongly agree’ | 3.531 | 0.468 | 1.600 | 4.400 | |

| Control variables ) | Individual level | Gender | Dummy: 1 = male, 2 = female | 1.514 | 0.500 | 1 | 2 |

| Individual level | Age | Dummy: 1 = 60–70 years old, 2 = 71–80 years old, 3 = Above 80 years old | 1.653 | 0.705 | 1 | 3 | |

| Individual level | Marital status | Dummy: 1 = Unmarried, 2 = Married, 3 = Divorced/Widowed | 2.113 | 0.560 | 1 | 3 | |

| Individual level | Education level | Dummy: 1 = None/Preschool education, 2 = Primary school, 3 = Middle school (including technical secondary school), 4 = University (including junior college), 5 = Postgraduate | 2.615 | 0.905 | 1 | 4 | |

| Individual level | Income (CNY/month) | Dummy: 1 = Below 1370 CNY, 2 = 1370–5600 CNY, 3 = Above 5600 CNY | 1.704 | 0.758 | 1 | 3 | |

| Individual level | Length of residence | Dummy: 1 = Less than 6 months, 2 = 6 months-3 years, 3 = 3–10 years, 4 = More than 10 years | 2.656 | 1.182 | 1 | 4 |

References

- WHO. Assessment of Aging and Health in China; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Larraz, B.; García-Gómez, E. Depopulation of Toledo’s historical centre in Spain? Challenge for local politics in world heritage cities. Cities 2020, 105, 102841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanini, S. Tourism pressures and depopulation in Cannaregio: Effects of mass tourism on Venetian cultural heritage. J. Cult. Herit. Manag. Sustain. Dev. 2017, 7, 164–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Picascia, S.; Romano, A.; Teobaldi, M. The airification of cities: Making sense of the impact of peer to peer short term letting on urban functions and economy. In Proceedings of the Annual Congress of the Association of European Schools of Planning, Lisbon, Portugal, 11–14 July 2017; pp. 2212–2223. [Google Scholar]

- Esmailpoor, N.; Esmaeilpoor, F.; Rezaeian, F. Explaining the causes of population outflow from the historical fabric of Yazd city. Cities 2023, 137, 104318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casagrande, M. Heritage, tourism, and demography in the island city of Venice: Depopulation and heritagisation. Urban Island Studies 2016, 2, 121–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Tian, Y.S.; Xu, L.G.; He, Y.; Zhang, S.; Huang, H.; Yang, J.Q.; Li, J.S.; Ju, D.D.; Zhang, Y. How to reunite the fragmented historic urban areas? City Plan. Rev. 2023, 47, 25–31. [Google Scholar]

- Motoc, I.; Timmermans, E.J.; Deeg, D.; Penninx, B.W.J.H.; Huisman, M. Associations of neighbourhood sociodemographic characteristics with depressive and anxiety symptoms in older age: Results from a 5-wave study over 15 years. Health Place 2019, 59, 102172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gale, C.R.; Dennison, E.M.; Cooper, C.; Sayer, A.A. Neighbourhood environment and positive mental health in older people: The Hertfordshire Cohort Study. Health Place 2011, 17, 867–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burkart, K.; Meier, F.; Schneider, A.; Breitner, S.; Canario, P.; Alcoforado, M.J.; Scherer, D.; Endlicher, W. Modification of heat-related mortality in an elderly urban population by vegetation (urban green) and proximity to water (urban blue): Evidence from Lisbon, Portugal. Environ. Health Persp. 2016, 124, 927–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, M.P.; Pahl, S.; Ashbullby, K.; Herbert, S.; Depledge, M.H. Feelings of restoration from recent nature visits. J. Environ. Psychol. 2013, 35, 40–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elliott, L.R.; White, M.P.; Taylor, A.H.; Herbert, S. Energy expenditure on recreational visits to different natural environments. Soc. Sci. Med. 2015, 139, 53–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Vries, S.; Ten Have, M.; Van Dorsselaer, S.; Van Wezep, M.; Hermans, T.; De Graaf, R. Local availability of green and blue space and prevalence of common mental disorders in the Netherlands. BJPsych. Open 2016, 2, 366–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- White, M.P.; Wheeler, B.W.; Herbert, S.; Alcock, L.; Depledge, M.H. Coastal proximity and physical activity: Is the coast an under-appreciated public health resource? Prev. Med. 2014, 69, 135–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Bell, S.; Graham, H.; Jarvis, S.; White, P. The importance of nature in mediating social and psychological benefits associated with visits to freshwater blue space. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2017, 167, 118–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nutsford, D.; Pearson, A.L.; Kingham, S.; Reitsma, F. Residential exposure to visible blue space (but not green space) associated with lower psychological distress in a capital city. Health Place 2016, 39, 70–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonnett, J. Water: The epic struggle for wealth, power, and civilization. Nat. Cult. 2016, 11, 206–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez, M.L.; Intralawan, A.; Vazquez, G.; Perez-Maqueo, O.; Sutton, P.; Landgrave, R. The coasts of our world: Ecological, economic and social importance. Ecol. Econ. 2007, 63, 254–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mcdougall, C.W.; Hanley, N.; Quilliam, R.S.; Bartie, P.J.; Robertson, T.; Griffiths, M.; Oliver, D.M. Neighbourhood blue space and mental health: A nationwide ecological study of antidepressant medication prescribed to older adults. Landscape Urban Plan. 2021, 214, 104132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coleman, T.; Kearns, R. The role of bluespaces in experiencing place, aging and wellbeing: Insights from Waiheke Island, New Zealand. Health Place 2015, 35, 206–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Twohig-Bennett, C.; Jones, A. The health benefits of the great outdoors: A systematic review and meta- analysis of greenspace exposure and health outcomes. Environ. Res. 2018, 166, 628–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van den Bosch, M.; Sang, A.O. Urban natural environments as nature-based solutions for improved public health—A systematic review of reviews. Environ. Res. 2017, 158, 373–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Den Berg, M.; Wendel-Vos, W.; Van Poppel, M.; Kemper, H.; Van Mechelen, W.; Maas, J. Health benefits of green spaces in the living environment: A systematic review of epidemiological studies. Urban For. Urban Gree. 2015, 14, 806–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markevych, I.; Schoierer, J.; Hartig, T.; Chudnovsky, A.; Hystad, P.; Dzhambov, A.M.; de Vries, S.; Triguero-Mas, M.; Brauer, M.; Nieuwenhuijsen, M.J.; et al. Exploring pathways linking greenspace to health: Theoretical and methodological guidance. Environ. Res. 2017, 158, 301–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, T.J.; He, Q.X.; Tan, S.H. Research on Planning Paths for Urban Blue Spaces to Promote Elderly Health. South Archit. 2022, 5, 54–63. [Google Scholar]

- Garrett, J.K.; White, M.P.; Huang, J.; Ng, S.; Hui, Z.; Leung, C.; Tse, L.A.; Fung, F.; Elliott, L.R.; Depledge, M.H.; et al. Urban blue space and health and wellbeing in Hong Kong: Results from a survey of older adults. Health Place 2019, 55, 100–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dempsey, S.; Devine, M.T.; Gillespie, T.; Lyons, S.; Nolan, A. Coastal blue space and depression in older adults. Health Place 2018, 54, 110–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vert, C.; Gascon, M.; Ranzani, O.; Márquez, S.; Triguero-Mas, M.; Carrasco-Turigas, G.; Arjona, L.; Koch, S.; Llopis, M.; Donaire-Gonzalez, D.; et al. Physical and mental health effects of repeated short walks in a blue space environment: A randomised crossover study. Environ. Res. 2020, 188, 109812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elliott, L.R.; White, M.P.; Grellier, J.; Garrett, J.K.; Cirach, M.; Wheeler, B.W.; Bratman, G.N.; van den Bosch, M.A.; Ojala, A.; Roiko, A.; et al. Research Note: Residential distance and recreational visits to coastal and inland blue spaces in eighteen countries. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2020, 198, 103800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labib, S.M.; Lindley, S.; Huck, J.J. Spatial dimensions of the influence of urban green-blue spaces on human health: A systematic review. Environ. Res. 2020, 180, 108869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gascon, M.; Zijlema, W.; Vert, C.; White, M.P.; Nieuwenhuijsen, M.J. Outdoor blue spaces, human health and well-being: A systematic review of quantitative studies. Int. J. Hyg. Envir. Health 2017, 220, 1207–1221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leng, H.; Yan, T.J.; Yuan, Q. Research progress on mental health effect of blue-green space and its enlightenments. Urban Plan. Int. 2022, 37, 34–43. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.J.; Yuan, Y.; Zhou, Y.Q.; Liu, Y. The neighborhood effect of exposure to green and blue space on the elderly’s health: A case study of Guangzhou, China. Sci. Geogr. Sin. 2020, 40, 1679–1687. [Google Scholar]

- Ekkel, E.D.; De Vries, S. Nearby green space and human health: Evaluating accessibility metrics. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2017, 157, 214–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaix, B.; Meline, J.; Duncan, S.; Merrien, C.; Karusisi, N.; Perchoux, C.; Lewin, A.; Labadi, K.; Kestens, Y. GPS tracking in neighborhood and health studies: A step forward for environmental exposure assessment, a step backward for causal inference? Health Place 2013, 21, 46–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Cheng, B.; Dong, L.; Zheng, T.; Wu, R. The moderating effect of social participation on the relationship between urban green space and the mental health of older adults: A case study in China. Land 2024, 13, 317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, T.; Leng, H.; Yuan, Q. The role of “nostalgia” in environmental restorative effects from the perspective of healthy aging: Taking Changchun parks as an example. Land 2023, 12, 1817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mcdougall, C.W.; Quilliam, R.S.; Hanley, N.; Oliver, D.M. Freshwater blue space and population health: An emerging research agenda. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 737, 140196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pasanen, T.P.; White, M.P.; Wheeler, B.W.; Garrett, J.K.; Elliott, L.R. Neighbourhood blue space, health and wellbeing: The mediating role of different types of physical activity. Environ. Int. 2019, 131, 105016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartig, T.; Mitchell, R.; de Vries, S.; Frumkin, H. Nature and health. Annu. Rev. Public Health 2014, 35, 207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gascon, M.; Sanchez-Benavides, G.; Dadvand, P.; Martinez, D.; Gramunt, N.; Gotsens, X.; Cirach, M.; Vert, C.; Molinuevo, J.L.; Crous-Bou, M.; et al. Long-term exposure to residential green and blue spaces and anxiety and depression in adults: A cross-sectional study. Environ. Res. 2018, 162, 231–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, B.; Chang, C.Y.; Sullivan, W.C. A dose of nature: Tree cover, stress reduction, and gender differences. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2014, 132, 26–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.R.; Sun, R.C.; Chen, X.; Qin, X.Z. Does extreme temperature exposure take a toll on mental health? Evidence from the China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study. Environ. Dev. Econ. 2023, 28, 486–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Z.W.; Yang, G.Y.; Zuo, S.D.; Jorgensen, G.; Koga, M.; Vejre, H. Critical review on the cooling effect of urban blue-green space: A threshold-size perspective. Urban For. Urban Gree. 2020, 49, 126630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, S. The restorative benefits of nature: Toward an integrative framework. J. Environ. Psychol. 1995, 15, 169–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulrich, R.S.; Simons, R.F.; Losito, B.D.; Fiorito, E.; Miles, M.A.; Zelson, M. Stress recovery during exposure to natural and urban environments. J. Environ. Psychol. 1991, 11, 201–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volker, S.; Kistemann, T. The Impact of Blue Space on Human Health and Well-being—Salutogenetic Health Effects of Inland Surface Waters: A Review. Int. J. Hyg. Envir. Health 2011, 214, 449–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lachowycz, K.; Jones, A.P. Towards a better understanding of the relationship between greenspace and health: Development of a theoretical framework. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2013, 118, 62–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wu, W.; Boelens, L. City profile: Suzhou, China—The interaction of water and city. Cities 2021, 112, 103119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statistics, S.M.B. The Seventh National Census Bulletin of Suzhou City. Available online: http://tjj.suzhou.gov.cn/sztjj/tjgb/202105/63f291317a62483ba1b6872b64b45b98.shtml (accessed on 31 May 2021).

- Yuan, Y.; Chen, Y.; Liu, Y.; Ding, K. The neighborhood effect of residential greenery on residents’ self-rated health: A case study of Guangzhou, China. Acta Geogr. Sin. 2021, 76, 1965–1975. [Google Scholar]

- White, M.P.; Elliott, L.R.; Gascon, M.; Roberts, B.; Fleming, L.E. Blue space, health and well-being: A narrative overview and synthesis of potential benefits. Environ. Res. 2020, 191, 110169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart-Brown, S.; Tennant, A.; Tennant, R.; Platt, S.; Parkinson, J.; Weich, S. Internal construct validity of the Warwick-Edinburgh Mental Well-being Scale (WEMWBS): A Rasch analysis using data from the Scottish Health Education Population Survey. Health Qual. Life Out. 2009, 7, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steptoe, A.; Feldman, P.J. Neighborhood problems as sources of chronic stress: Development of a measure of neighborhood problems, and associations with socioeconomic status and health. Ann. Behav. Med. 2001, 23, 177–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guite, H.F.; Clark, C.; Ackrill, G. The impact of the physical and urban environment on mental well-being. Public Health 2006, 120, 1117–1126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fat, L.N.; Scholes, S.; Boniface, S.; Mindell, J.; Stewart-Brown, S. Evaluating and establishing national norms for mental wellbeing using the short Warwick-Edinburgh Mental Well-being Scale (SWEMWBS): Findings from the Health Survey for England. Qual. Life Res. 2017, 26, 1129–1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Yu, B.; Yao, K.M. Current status of research on human comfort and its development and application prospects. Meteorol. Sci. Technol. 2002, 1, 11–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.J.; Jiang, M.H.; Zou, Y.L. The influence of water environment microclimate on human comfort in Jiangnan classical gardens: Taking Suzhou Master of the Nets Garden as an example. Chin. Horiticulture Abstr. 2016, 32, 142–144. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, J.C.; Zhu, X.Y.; Li, G.M. Influence of waterfront area surrounding small-scale landscape water bodies in cities on human comfort. China Water Waste Water 2007, 23, 101–104. [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, F.; Xiao, J.; Lu, Y. Summer load characteristic analysis based on body comfort index. Jiangsu Electr. Eng. 2005, 24, 11–13. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.; Yuan, Y.; Zhou, Y. Exploring the Association between Neighborhood Blue Space and Self-Rated Health among Elderly Adults: Evidence from Guangzhou, China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 16342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, J.B.; Li, X.; Zhou, J.; Zhou, W. Application of cluster analysis and water quality identification index on Suzhou urban rivers. Environ. Eng. 2016, 34, 103–107. [Google Scholar]

- Ji, X.H.; Zhang, J.W. Upgrading the characteristics of streets and revealing the connotation of water city: The integration of traditional streets and local culture in Suzhou Ancient City. City Plan. Rev. 2014, 38, 46–49. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, J.; Lin, W.S. Residential satisfaction level and influencing factors of declining old town residents in Suzhou. Prog. Geogr. 2017, 36, 159–170. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, G.T.; Zhu, X.B. Research on the protection and planning of context of historical blocks: Analysis of the cultural heritage of Pingjiang Historical Block of Suzhou. Chin. Landsc. Archit. 2014, 30, 82–84. [Google Scholar]

- Finlay, J.; Franke, T.; Mckay, H.; Sims-Gould, J. Therapeutic landscapes and wellbeing in later life: Impacts of blue and green spaces for older adults. Health Place 2015, 34, 97–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).