Abstract

Rangeland restoration in southern Africa faces complex challenges that require the involvement of diverse social groups to ensure both ecological and social sustainability. This systematic review focuses on the role of social inclusion in rangeland restoration across multiple countries in the region, specifically examining the engagement of marginalized groups such as women, youth, and indigenous communities. We conducted a comprehensive search using the PRISMA approach, utilizing Scopus and other literature sources. Initially, we found 853 articles published between 2000 and 2024, which were subsequently screened down to 20 studies that met stringent inclusion criteria. This review identifies key strategies and outcomes associated with social inclusion in restoration efforts. Our findings reveal that participatory planning, gender-inclusive strategies, indigenous engagement, and capacity building are crucial for gaining community support, promoting social equity, and enhancing ecological resilience. However, challenges such as power dynamics, cultural norms, and resource constraints often impede the full realization of these inclusive practices. Despite these barriers, integrating local and indigenous knowledge and empowering marginalized groups significantly strengthens governance structures and leads to more sustainable restoration outcomes. Our review highlights the necessity of adopting holistic and inclusive approaches in rangeland restoration where social inclusion is not just a component but a central pillar of successful ecological management. It emphasizes the importance of social inclusion in the restoration of communal rangelands in southern Africa and provides insights into the approaches used, challenges faced, and outcomes achieved in incorporating social inclusion in rangeland restoration efforts. Our findings underscore the significance of collaborative efforts and social inclusion among local communities, policymakers, and stakeholders to achieve the sustainable restoration of communal rangelands in southern Africa.

1. Introduction

Communal rangelands are critical to the livelihoods of millions of people in southern Africa, providing essential resources for livestock grazing, fuelwood, and traditional medicine [1,2]. However, these rangelands face significant challenges, including land degradation, overgrazing, and climate change, which threaten their ecological integrity and the well-being of the communities that depend on them [3,4]. The restoration of these rangelands is not only a matter of ecological necessity but also a social imperative, as the process directly impacts the lives and livelihoods of the people who live and work on these lands [5,6,7]. Social inclusion is increasingly recognized as a key component in successful environmental restoration initiatives. Social inclusion involves actively engaging local communities, considering their knowledge and perspectives, and ensuring their participation in decision-making processes [8,9]. Inclusive approaches ensure that the diverse voices and needs of all community members, especially marginalized groups such as women, youth, and indigenous populations, are considered and integrated into the planning and implementation of restoration activities [10,11]. In the context of communal rangelands, where land tenure and access rights are often complex and contested, social inclusion can play a pivotal role in achieving equitable and sustainable outcomes [12,13].

Despite the acknowledged importance of social inclusion, there is a limited understanding of how it is practically implemented in rangeland restoration projects across southern Africa and what impact it has on the success and sustainability of these initiatives. The existing literature tends to focus more on the technical and ecological aspects of restoration with less attention given to the social dynamics that underpin these efforts [1,14]. This knowledge gap is critical, as the success of restoration initiatives is often contingent on the active participation and support of local communities [15,16]. This systematic review aims to address this gap by critically examining the role of social inclusion in the restoration of communal rangelands in southern Africa. The review will explore various approaches to social inclusion, identify the challenges encountered, and assess the outcomes of these practices in terms of both social equity and ecological resilience. By synthesizing evidence from across the region, this review seeks to provide insights into best practices for integrating social inclusion into rangeland restoration and to highlight areas where further research is needed.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Framework

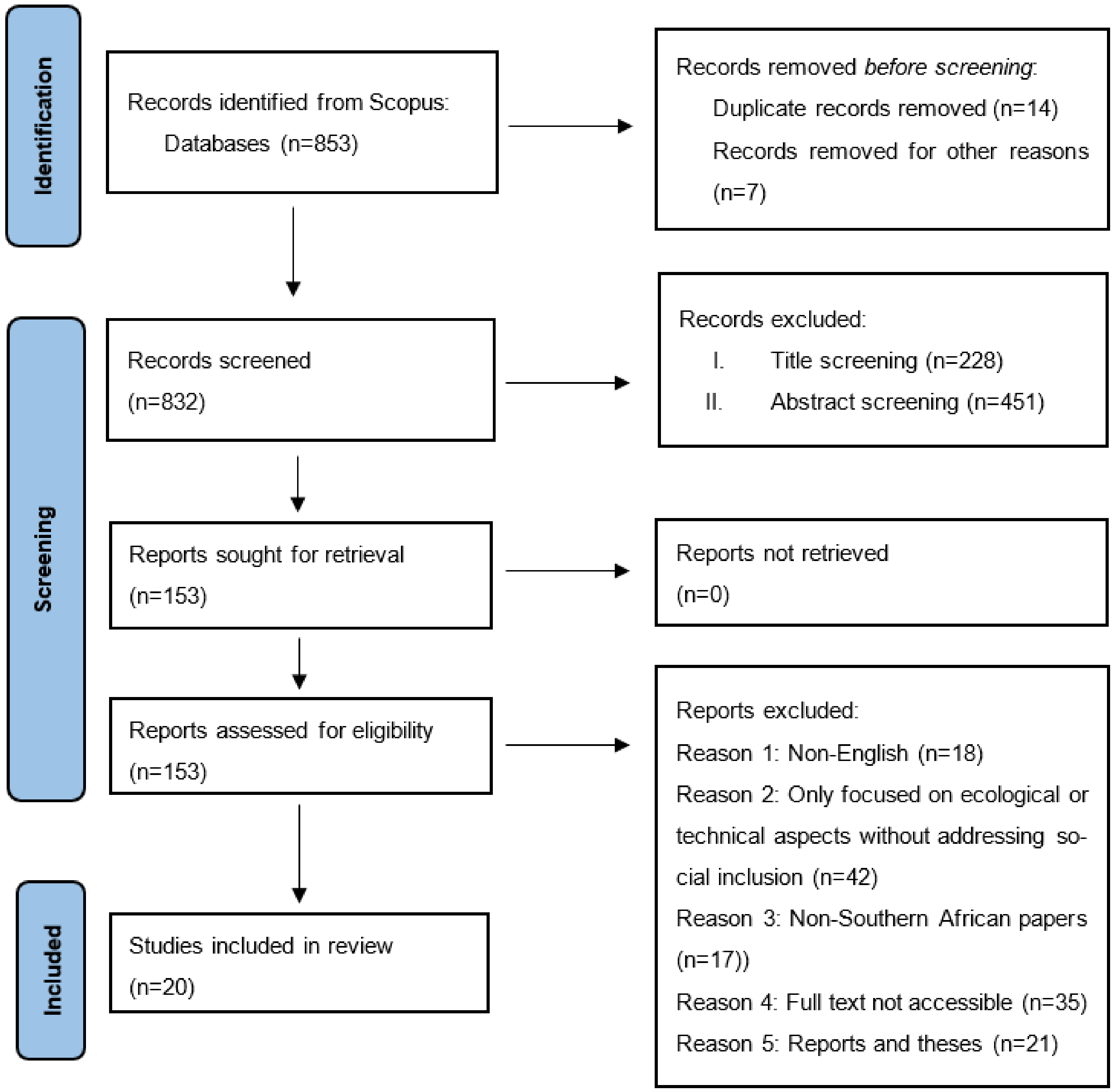

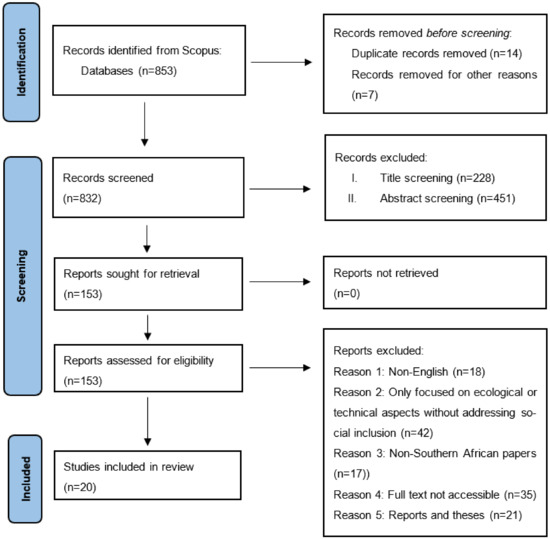

This systematic review followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines. A PRISMA flow diagram (Figure 1) was included to illustrate the study selection process. Additionally, a complete PRISMA checklist was used to ensure a comprehensive and transparent review process. Although the review was not registered in a public database like PROSPERO, we made every effort to maintain the highest standards of systematic review methodology. By adopting the PRISMA framework, the research process became more transparent, accurate, and replicable, as supported by previous studies [17,18]. The review consisted of two main stages: systematic searching and selection of relevant literature, and careful management, coding, and analysis of the data extracted from the selected studies. This structured methodology ensured a thorough review and provided a foundation for future research to replicate and expand upon the findings. The review will focus on studies that explore the role of social inclusion in the restoration of communal rangelands in southern Africa. It encompassed various approaches, outcomes, and challenges reported across different contexts within the region.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram for literature search (n = number of articles included at each stage).

2.2. Literature Search Strategy

The literature search for this systematic review used Scopus, a comprehensive multidisciplinary database, to find studies on the role of social inclusion in restoring communal rangelands in southern Africa. To ensure a structured and thorough approach, the search strategy was developed using the Population, Exposure, and Outcomes (PEO) framework. The population of interest included communities living in and dependent on communal rangelands across southern Africa. To find relevant studies, keywords such as “Communal rangelands”, “Pastoralists”, “Agropastoralists”, “Local communities”, “Indigenous communities”, and the specific names of countries within southern Africa were used. These terms were chosen to reflect the diverse groups and regions within southern Africa that are important to the study. The exposure referred to social inclusion practices and interventions aimed at restoring communal rangelands. Keywords related to various aspects of social inclusion and restoration practices were used, including “Social inclusion”, “Community participation”, “Gender equity”, “Indigenous knowledge”, “Participatory planning”, “Stakeholder engagement”, and “Rangeland restoration”. These terms helped identify studies that explored how social dynamics and inclusive approaches are integrated into rangeland restoration efforts. The outcomes of interest focused on the social and ecological impacts resulting from the integration of social inclusion in rangeland restoration initiatives. Keywords such as “Social equity”, “Community empowerment”, “Ecological resilience”, “Restoration success”, “Sustainable land management”, and “Livelihood improvement” were used. These keywords aimed to capture the wide range of results that social inclusion could have in the context of rangeland restoration. Boolean operators (AND, OR) were used to carefully combine the search terms, ensuring precision and relevance in the search results. We used the following search string to investigate the topic:

TITLE-ABS-KEY ((“rangeland restoration” OR “communal rangelands” OR “degraded rangelands” OR “rangeland management”) AND (“social inclusion” OR “community involvement” OR “participatory management” OR “inclusive management”) AND (“Southern Africa” OR “South Africa” OR “Namibia” OR “Botswana” OR “Lesotho” OR “Eswatini” OR “Zimbabwe” OR “Mozambique”) AND (“land degradation” OR “sustainable land management” OR “land rehabilitation” OR “ecosystem restoration”)).

This approach allowed for a broad yet focused search, capturing studies that addressed the key themes of the review. The search included publications from the past years (until 30 June 2024) to ensure the inclusion of recent developments and trends.

2.3. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

As reflected in Table 1, studies were included if they met the following criteria: they focused on communal rangelands in southern Africa, addressed social inclusion in the context of rangeland restoration, reported on approaches, challenges, or outcomes related to social inclusion, and were published in English. Studies were excluded if they did not focus on southern Africa, did not consider social inclusion as a primary or significant component, were not related to rangeland restoration (e.g., focused solely on ecological or technical aspects), or were opinion pieces, editorials, or lacked empirical evidence.

Table 1.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria for the review articles in the order of selection.

2.4. Selection of Studies and Data Extraction

Figure 1 illustrates the two stages of the study selection process. In the first stage, two independent reviewers (Mhlangabezi Slayi and John Moyo Mahajana) screened the titles and abstracts of all retrieved studies using the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Any disagreements were resolved through discussion, and a 92% level agreement was reached. The second stage involved assessing the full-text articles of the selected studies to ensure they met the inclusion criteria. Any discrepancies between reviewers during this stage were discussed until a consensus was reached. To collect relevant information from each included study, a standardized data extraction form was used. This form covered various aspects, including study characteristics (such as author, year, location, and study design), population and community characteristics (e.g., demographic details, social groups involved), descriptions of social inclusion practices (e.g., participatory approaches, stakeholder engagement), outcomes related to social inclusion (e.g., social equity, community empowerment, restoration success), and challenges encountered (e.g., social barriers, institutional constraints). This systematic approach ensured the accurate capture and analysis of all relevant data, providing a solid foundation for the findings of the review.

2.5. Data Analysis

The systematic review used a thematic approach to analyze the data, aiming to identify recurring themes and patterns in the selected studies. This approach allowed for a comprehensive examination of how social inclusion contributes to the restoration of communal rangelands in southern Africa. It focused on the different approaches used, challenges faced, and outcomes achieved. To gain a deeper understanding of the field, a bibliometric analysis was conducted using the Bibliometrix R package (Aria and Cuccurullo, 2017; R Core Team, 2021) [19]. This powerful tool enabled the exploration of scientific domains through network analysis, including multiple correspondence analyses on keywords, titles, and abstracts of the articles. The analysis revealed the relationships and trends within the research on social inclusion and rangeland restoration. A word cloud was generated to visualize the most frequently cited words in the abstracts of the selected studies. Only words with a frequency threshold of 30% were included in the word cloud, which presented the 29 most common terms. This visual representation provided an overview of the key themes and concepts discussed in the literature and ensured the relevance and accuracy of the search terms used in the systematic review. Additionally, a co-occurrence network and link analysis were performed to explore the relationships between different knowledge areas based on the keywords extracted from the abstracts [20]. The size of the label and circle representing each term in this analysis was determined by its weight, corresponding to the frequency of its usage in the articles [21]. The links between terms indicated the relationships between various concepts, with closer proximity indicating stronger connections between knowledge areas. The combination of bibliometric and thematic analysis provided a comprehensive understanding of the research landscape on social inclusion in rangeland restoration. It identified key areas of focus, interconnections between different themes, and gaps in the existing literature. These insights are valuable for future research, policy implementing, and policy-making in this field.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Overview of Included Studies

As shown in Table 2, a total of 20 studies were included in this systematic review after the initial search and screening process. These studies were conducted in various countries within southern Africa, including South Africa, Namibia, Botswana, Zimbabwe, and others. The studies used different methodologies, such as qualitative case studies, mixed-methods research, and community-based participatory research. They were published between 2007 and 2024, reflecting recent interest and developments in the field of social inclusion and rangeland restoration. Most studies focused on community-based rangeland management projects, while others examined broader land management policies that incorporated social inclusion elements. Overall, these studies highlight the importance of social inclusion in the restoration of communal rangelands in southern Africa. Through various methodologies, from qualitative case studies to mixed-methods and ethnographic research, they provide strong evidence that involving marginalized groups such as women, youth, indigenous communities, and pastoralists significantly enhances both the social and ecological outcomes of restoration projects. For example, Finca et al. [22] and Heita et al. [23] emphasize how the inclusion of women and indigenous groups leads to improved rangeland management and social equity. This is consistent with literature suggesting that marginalized groups often possess unique knowledge and perspectives that are crucial for sustainable land management practices [12]. The empowerment of these groups through participatory approaches not only fosters a sense of ownership but also ensures that restoration strategies are culturally and contextually appropriate, increasing their likelihood of success [24]. Similarly, studies by Moyo et al. [25] and Mashinini et al. [16] demonstrate that involving youth in decision-making processes contributes to the long-term sustainability of restoration efforts. Youth engagement is particularly vital in the context of southern Africa, where younger generations are often more open to adopting innovative practices and technologies that can enhance restoration outcomes [26].

Moreover, capacity-building initiatives that target marginalized groups, as highlighted by McGranahan [27], not only improve the sustainability of these projects but also contribute to broader community development goals, reinforcing the interconnectedness of social and environmental well-being [10]. The importance of integrating indigenous knowledge into restoration practices, as noted by Stringer et al. [14], Allsopp et al. [28], and Ngwenya et al. [3], is also well documented in the literature. Indigenous communities often have a deep understanding of local ecosystems and have developed sustainable land use practices over generations. Incorporating this knowledge into modern restoration efforts can enhance ecological resilience and ensure that interventions are more attuned to local environmental conditions [7]. This is particularly important in the face of climate change, where traditional practices can offer valuable insights into adaptation strategies [29]. However, the studies also reveal significant challenges in achieving effective social inclusion. Power dynamics, as discussed in studies like Peel and Stalman [11] and Basupi et al. [30], often hinder the equitable participation of all community members, particularly women and the elderly. These findings align with broader research indicating that social hierarchies and cultural norms can limit the involvement of marginalized groups, ultimately undermining the effectiveness of restoration efforts [31,32]. Addressing these challenges requires deliberate strategies to dismantle barriers to participation and to create inclusive decision-making processes that genuinely reflect the needs and aspirations of all community members [17,33,34]. In summary, the evidence from these studies strongly supports the argument that social inclusion is not just a supplementary component but a fundamental prerequisite for the successful restoration of communal rangelands in southern Africa. The findings suggest that restoration projects that actively engage marginalized groups are more likely to achieve sustainable outcomes both socially and ecologically. This highlights the need for policies and interventions that prioritize social equity and inclusivity as central pillars of environmental restoration initiatives.

Table 2.

Characteristics of included studies.

Table 2.

Characteristics of included studies.

| Study ID | Authors | Year | Country | Methodology | Social Groups Focused | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Finca et al. [22] | 2023 | South Africa | Qualitative Case Study | Women, Indigenous groups | Improved participation of marginalized groups led to enhanced rangeland management. |

| 2 | Heita et al. [23] | 2024 | Namibia | Mixed Methods | Youth, Pastoralists | Youth involvement in decision making improved long-term sustainability. |

| 3 | Mbaiwa et al. [12] | 2019 | Botswana | Participatory Research | Women, Farmers | Gender inclusion strategies increased social equity and restoration success. |

| 4 | Moyo et al. [25] | 2013 | Zimbabwe | Qualitative Interviews | Indigenous communities | Inclusion of traditional knowledge improved ecological outcomes and community resilience. |

| 5 | Mashinini & De Villiers [16] | 2004 | Lesotho | Case Study | Women, Elderly | Social inclusion practices led to increased community cohesion and better restoration outcomes. |

| 6 | Vetter [26] | 2013 | South Africa | Mixed Methods | Youth, Women | Capacity-building initiatives empowered marginalized groups and improved project sustainability. |

| 7 | McGranahan [27] | 2008 | Zambia | Focus Group Discussions | Indigenous groups, Youth | Engagement of local communities enhanced ownership and the success of restoration initiatives. |

| 8 | Nyahunda & Tirivangasi [10] | 2021 | Zimbabwe | Participatory Action Research | Women, Small-scale farmers | Participation of women in leadership roles positively impacted restoration and social equity. |

| 9 | Stringer et al. [14] | 2007 | Eswatini | Survey and Interviews | Pastoralists, Women | The inclusion of pastoralist knowledge contributed to better rangeland management practices. |

| 10 | Allsopp et al. [28] | 2007 | Namibia | Ethnographic Study | Indigenous groups | The use of indigenous practices in restoration fostered stronger ecological resilience. |

| 11 | Ngwenya et al. [3] | 2017 | Botswana | Mixed Methods | Farmers, Women | Farmer-led initiatives with a focus on women’s participation led to sustainable land use practices. |

| 12 | Siangulube et al. [7] | 2023 | Zambia | Case Study | Youth, Community leaders | Youth engagement in restoration projects resulted in increased community involvement and awareness. |

| 13 | Moyo & Ravhuhali [29] | 2022 | South Africa | Participatory Research | Women, Indigenous groups | Strategies to include marginalized communities improved social justice and ecological restoration. |

| 14 | Peel & Stalmans [11] | 2018 | Zimbabwe | Qualitative Case Study | Women, Elderly | Social inclusion promoted better resource allocation and management in restoration efforts. |

| 15 | Basupi et al. [30] | 2019 | Botswana | Participatory Workshops | Indigenous groups, Youth | Participatory workshops increased knowledge exchange and community-driven restoration. |

| 16 | Gwimbi [31] | 2013 | Lesotho | Focus Group Discussions | Pastoralists, Women | Collaborative approaches with a focus on pastoralist knowledge enhanced restoration success. |

| 17 | Ndhlovu [33] | 2022 | Zimbabwe | Case Study | Youth, Smallholder farmers | Inclusion of youth in decision-making processes led to innovative and sustainable restoration practices. |

| 18 | Djenontin et al. [17] | 2022 | Malawi | Mixed Methods | Women, Indigenous groups | Integration of indigenous practices with modern techniques resulted in improved rangeland restoration. |

| 19 | Rasch et al. [32] | 2017 | South Africa | Qualitative Interviews | Youth, Women | Empowerment of women and youth through targeted programs increased community resilience and cohesion. |

| 20 | Nyirenda et al. [34] | 2010 | Zambia | Ethnographic Study | Indigenous communities | Ethnographic insights into community-led initiatives revealed critical factors for successful restoration. |

3.2. Approaches to Restoration in Communal Rangelands

Table 3 outlines several approaches to social inclusion in the restoration of communal rangelands in southern Africa and their associated outcomes. These approaches highlight the diverse strategies used to engage communities and enhance the effectiveness of restoration efforts. Participatory planning, which involves community members in decision-making processes, has been widely reported to increase community buy-in and ownership of restoration projects. This approach has been implemented in studies such as those by Senda et al. [8], Rohde et al. [35], Siangulube et al. [7], and Rasch et al. [32]. These studies demonstrate that when communities are actively involved in planning, they are more likely to support and sustain restoration efforts. This aligns with the broader literature, which emphasizes that participatory approaches lead to more sustainable outcomes because they are rooted in local knowledge and values [1]. By ensuring that community members have a stake in the planning process, the likelihood of long-term success is significantly increased [16]. Gender-inclusive strategies focus on increasing the participation of women in restoration activities. Studies by Nyirenda et al. [34], Mashinini and De Villiers [16], Heita et al. [23], Finca et al. [22], and Basupi et al. [30] report that these strategies enhance social equity and lead to better restoration outcomes. The inclusion of women in decision-making roles has been shown to not only improve leadership representation but also to bring diverse perspectives that enrich the restoration process. The literature supports this by showing that gender diversity in environmental management leads to more comprehensive and effective solutions [36]. Furthermore, empowering women contributes to broader social benefits, such as improved family and community well-being [25].

The inclusion of indigenous knowledge and practices is another critical approach, as demonstrated in studies by Djenontin et al. [17], Bennet et al. [37], Nyirenda et al. [34], Reed et al. [6], and Robinson et al. [38]. These studies highlight the importance of adopting traditional knowledge, which sometimes offers time-tested and ecologically sound practices for managing rangelands. Indigenous engagement is crucial for ecological resilience and adaptation strategies, as it incorporates local expertise that is often overlooked in conventional scientific approaches [39]. By respecting and integrating indigenous practices, restoration efforts are more likely to be culturally relevant and supported by local communities. Capacity building involves training and empowering local institutions to sustain restoration efforts. Studies by Perkins et al. [9], Stringer et al. [14], Teketay et al. [40], Simba et al. [41], and Senda et al. [8] report that this approach leads to strengthened governance structures and enhanced community resilience. Building local capacity ensures that communities have the necessary skills and knowledge to manage restoration projects effectively over the long term. This approach is supported by literature that emphasizes the importance of local capacity for the sustainability of environmental management initiatives [17]. Strong local institutions are better equipped to handle challenges and adapt to changing conditions, making restoration efforts more robust and durable [42]. Engaging youth in restoration activities and decision making is crucial for ensuring long-term sustainability. Studies by Ngwenya et al. [3], Mairomi et al. [13], Homewood [43], Gwimbi [31], Bekele et al. [39], and Atsbha et al. [44] show that involving young people brings innovative ideas and energy to restoration projects as well as increasing community awareness and engagement. Youth engagement is vital for intergenerational knowledge transfer and for fostering a sense of stewardship among the next generation [45]. By including youth, communities can ensure that restoration efforts continue into the future, driven by a generation that values and understands the importance of sustainable land management.

Collaborative governance involves establishing inclusive and representative structures that bring together diverse stakeholders. Studies by Arntzen [46], Basupi et al. [30], Hailu [47], Herrera and Davies [15], and Ndhlovu [33] report that such governance structures improve coordination and stakeholder collaboration, leading to more successful project outcomes. The literature supports this by suggesting that inclusive governance models are more effective in managing complex environmental issues because they draw on a wide range of knowledge and experiences [9]. Collaborative governance fosters transparency and accountability, which are essential for the legitimacy and success of restoration initiatives [6]. Empowering local communities to lead restoration efforts is another approach that has shown significant benefits. Studies by Ngwenya et al. [3], Nyirenda et al. [34], Rasch et al. [32], Safari et al. [48], and Selolwane [49] indicate that when communities take the lead, there is greater ownership of the projects, which translates into sustained ecological benefits and increased community cohesion. The literature on community-based natural resource management (CBNRM) supports this, showing that when communities have control over their resources, they are more likely to manage them sustainably [48]. Community-led initiatives also empower individuals and groups, fostering a sense of pride and responsibility that is crucial for the long-term success of restoration efforts. Facilitating the exchange of knowledge between different community groups enhances restoration strategies and improves social cohesion. Studies by Senda et al. [8], Twyman [50], Vetter [26], Mogome-Ntsatsi and Adeola [51], Adams [52], and Basupi et al. [30] demonstrate that knowledge exchange allows for the integration of diverse perspectives, leading to more comprehensive and effective restoration practices. This approach is supported by literature that highlights the value of co-learning and participatory research methods in environmental management [6]. By creating spaces for dialogue and shared learning, communities can build on each other’s strengths and address challenges more collaboratively.

Addressing and managing conflicts arising from competing land use interests is essential for the success of restoration projects. Studies by Arntzen [46], Bennet et al. [37], Finca et al. [22], Gxasheka et al. [2], Mbaiwa et al. [12], and Milton et al. [36] report that conflict resolution strategies lead to reduced conflicts, improved social relations, and more effective implementation of restoration practices. The literature suggests that conflicts over land and resources are common in communal areas, and effective conflict resolution is key to maintaining the social cohesion necessary for successful restoration [40]. By addressing conflicts early and involving all stakeholders in the process, communities can prevent disputes from derailing restoration efforts. Developing systems to track the progress and impact of restoration efforts is crucial for ensuring project accountability and adaptive management. Studies by Moyo and Ravhuhali [29], Perkins et al. [9], Robinson et al. [38], Senda et al. [8], and Reed et al. [1] highlight the importance of monitoring and evaluation in understanding the outcomes of restoration projects and making necessary adjustments. The literature supports the idea that ongoing monitoring and evaluation are essential for adaptive management, allowing for the continuous improvement of strategies based on real-time feedback [35]. Effective monitoring systems also help build trust and credibility, as they provide transparent evidence of progress and challenges. In summary, these approaches to social inclusion in the restoration of communal rangelands in southern Africa underscore the importance of community involvement, gender equity, indigenous knowledge, capacity building, and collaborative governance. The outcomes reported in the studies reflect the positive impact of these strategies, which are supported by the broader literature. By integrating these approaches, restoration projects can achieve not only ecological resilience but also social equity, community empowerment, and long-term sustainability.

Table 3.

Approaches to social inclusion in rangeland restoration.

Table 3.

Approaches to social inclusion in rangeland restoration.

| Approach | Description | Studies Implementing This Approach | Outcomes Reported |

|---|---|---|---|

| Participatory Planning | Involvement of communities in planning processes | [7,8,32,35] | Increased community buy-in and ownership, leading to more sustainable restoration efforts. |

| Gender-Inclusive Strategies | Focus on increasing women’s participation | [16,22,23,30,34] | Enhanced social equity, improved restoration outcomes, and increased leadership roles for women. |

| Indigenous Engagement | Inclusion of indigenous knowledge and practices | [6,17,37,38] | Utilization of traditional knowledge, improved ecological resilience, and better adaptation strategies. |

| Capacity Building | Training and empowering local institutions | [8,9,14,40,41] | Strengthened governance structures, sustained restoration efforts, and enhanced community resilience. |

| Youth Engagement | Involvement of youth in decision-making and restoration activities | [3,13,31,39,43,44] | Improved long-term sustainability, increased community awareness, and innovative restoration practices. |

| Collaborative Governance | Establishing inclusive and representative governance structures | [15,30,33,46,47] | Better coordination, increased stakeholder collaboration, and enhanced project success. |

| Community-Led Initiatives | Empowering local communities to take the lead in restoration efforts | [3,32,34,48,49] | Greater ownership of projects, sustained ecological benefits, and increased community cohesion. |

| Knowledge Exchange | Facilitating the sharing of knowledge between different community groups | [8,26,30,50,51,52] | Enhanced restoration strategies, integration of diverse perspectives, and improved social cohesion. |

| Conflict Resolution | Addressing and managing conflicts arising from competing land use interests | [2,12,22,36,37,46] | Reduction in conflicts, improved social relations, and more effective implementation of restoration practices. |

| Monitoring and Evaluation | Developing systems to track the progress and impact of restoration efforts | [1,8,9,29,38] | Improved project accountability, adaptive management practices, and better understanding of project outcomes. |

3.3. Challenges in Social Inclusion and Governance

Table 4 outlines key challenges to social inclusion in communal rangeland restoration efforts across southern Africa. These challenges impact the effectiveness of restoration projects by limiting participation, perpetuating inequalities, and reducing overall project success. Power dynamics refer to social hierarchies and power imbalances that can hinder equitable participation in restoration projects. Studies such as Basupi et al. [30], Djenontin et al. [17], Dougill and Reed [53], and Gwimbi [31] report that marginalized groups often face exclusion from decision-making processes due to these dynamics. This marginalization can lead to the overlooking of important perspectives and needs, reducing the effectiveness of restoration efforts. The literature supports this by emphasizing that power imbalances often result in the dominance of elite groups, who may prioritize their interests over communal benefits [27]. Addressing power dynamics is crucial to ensuring that all community members, especially the most vulnerable, have a voice in restoration efforts [13]. Cultural norms, including gender roles and traditional practices, can limit the participation of certain groups, particularly women and marginalized communities. Studies by Rohde et al. [35], Safari et al. [48], Simba et al. [41], and Mashinini and De Villiers [16] highlight how these cultural barriers lead to imbalanced outcomes and perpetuate existing inequalities. This issue is well documented in the literature, where it is noted that deeply entrenched gender norms often restrict women’s access to resources and decision-making opportunities [53]. Overcoming these cultural barriers requires targeted interventions that challenge and change the underlying social norms [47].

Resource constraints, including limited financial, technical, and human resources, significantly hinder the effective implementation of restoration projects. Studies by Abdulahi et al. [54], Gxasheka et al. [2], Heita et al. [23], McGranahan and Kirkman [27], and Ndhlovu [33] report that these limitations lead to inadequate support for inclusion and challenges in sustaining projects. The literature supports these findings, emphasizing that resource constraints often result in underfunded and poorly supported initiatives that struggle to achieve their goals [15]. Adequate resources are essential to provide the necessary training, tools, and ongoing support to ensure the long-term success of restoration projects [3]. Weak governance structures, lack of legal frameworks, and bureaucratic inefficiencies are significant institutional barriers to social inclusion. Studies by Reed et al. [6], Mbaiwa et al. [12], Basupi et al. [30], and Arntzen [46] highlight how these barriers lead to a gap between policy and practice, resulting in the ineffective implementation of social inclusion strategies. This aligns with the literature, which argues that strong institutions and supportive policies are critical for enabling inclusive and sustainable environmental management [10]. Without effective governance, well-intentioned restoration projects may falter due to a lack of enforcement and coordination [6,55].

Social conflicts arising from competing land use interests and different stakeholder goals can disrupt restoration efforts. Bennet and Barreti [37], Dougill and Reed [53], Finca et al. [22], and Moyo et al. [25] report that such conflicts lead to delays in project timelines and erode trust among stakeholders. The literature also emphasizes that conflicts are common in communal land settings, where diverse interests and needs must be balanced [56]. Effective conflict resolution mechanisms are necessary to manage these disputes and ensure that restoration efforts can proceed smoothly [38]. Knowledge gaps refer to the limited understanding or awareness of the importance of social inclusion in restoration. Studies by Herrera and Davies [15], Milton et al. [36], Moyo and Ravhuhali [29], Nyirenda et al. [34], and Reed et al. [6] indicate that these gaps result in ineffective restoration strategies and missed opportunities for community engagement. The literature supports the idea that knowledge is a critical component of successful restoration efforts with knowledge gaps often leading to suboptimal outcomes [1]. Bridging these gaps through education and capacity-building initiatives is essential for improving the effectiveness and inclusivity of restoration projects [35]. Environmental variability, including unpredictable weather patterns and the effects of climate change, poses significant challenges to restoration projects. Safari et al. [48], Mlaza et al. [57], Kwaza et al. [58], and Mashinini and De Villiers [16] report that such variability increases the vulnerability of projects and makes it difficult to maintain ecological stability. The literature highlights that climate change exacerbates the challenges of land degradation and restoration, making adaptive management strategies essential [32]. Restoration projects must be resilient and flexible to cope with these environmental uncertainties [48].

The lack of long-term commitment from stakeholders, often due to short-term project funding, is another significant challenge. Ngwenya et al. [3], Senda et al. [8], Stringer et al. [14], and Vetter [26] note that this lack of sustained engagement reduces the impact and sustainability of restoration efforts. The literature on project sustainability emphasizes that long-term commitment is crucial for achieving lasting outcomes, as short-term interventions often fail to address the root causes of degradation [9]. Securing long-term funding and commitment from all stakeholders is essential for the success of restoration projects [25]. Technological barriers, including limited access to or knowledge of modern restoration techniques and tools, hinder the implementation of effective restoration practices. Studies by Abdulahi et al. [54], Mureithi et al. [4], Mureithi et al. [45], and Bestelmeyer et al. [59] report that these barriers lead to reliance on outdated methods and reduced innovation. The literature suggests that access to appropriate technology is critical for enhancing the efficiency and effectiveness of restoration efforts [58]. Providing communities with the tools and training they need to adopt modern techniques is essential for overcoming these barriers [22]. The insufficient development of local leadership capacities to drive restoration initiatives is another challenge highlighted by Moyo and Ravhuhali [29], Atsbha et al. [44], Ngwenya et al. [3], and Perkins et al. [9]. This lack of leadership results in lowered project effectiveness, a lack of local ownership, and decreased long-term sustainability. The literature supports the importance of strong local leadership in environmental management, as it fosters accountability, local ownership, and sustained engagement [17,60]. Developing local leadership capacities is crucial for ensuring that restoration projects are community-driven and supported over the long term [24]. In summary, these challenges underscore the complex and multifaceted nature of social inclusion in rangeland restoration. Addressing these challenges requires a comprehensive approach that includes strengthening governance structures, building local capacities, securing long-term funding, and fostering inclusive participation across all levels of society. By tackling these obstacles, restoration efforts can become more effective, equitable, and sustainable, ultimately leading to healthier rangelands and more resilient communities.

Table 4.

Challenges to social inclusion.

Table 4.

Challenges to social inclusion.

| Challenge | Description | Studies Reporting This Challenge | Impact on Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Power Dynamics | Social hierarchies and power imbalances that hinder equitable participation | [3,17,30,31,34,36,53] | Marginalization of less powerful groups, resulting in their exclusion from decision-making processes and reduced effectiveness of restoration efforts. |

| Cultural Norms | Gender and cultural barriers limiting the participation of certain groups | [16,35,41,48] | Reduced participation of women and marginalized groups, leading to imbalanced outcomes and perpetuation of existing inequalities. |

| Resource Constraints | Limited financial, technical, and human resources hindering effective implementation of restoration projects | [2,10,23,27,33,54] | Inadequate support for inclusion, challenges in sustaining projects, and compromised restoration outcomes due to lack of resources. |

| Institutional Barriers | Weak governance structures, lack of legal frameworks, and bureaucratic inefficiencies | [6,12,30,46] | Ineffective implementation of social inclusion strategies, leading to a gap between policy and practice, and diminished project success. |

| Social Conflicts | Conflicts arising from competing land use interests and different stakeholder goals | [3,22,25,37,53] | Disruption of restoration efforts, delays in project timelines, and erosion of trust among stakeholders. |

| Knowledge Gaps | Limited understanding or awareness of the importance of social inclusion in restoration | [6,11,15,29,36] | Ineffective restoration strategies, missed opportunities for community engagement, and suboptimal ecological outcomes. |

| Environmental Variability | Challenges posed by unpredictable weather patterns and climate change effects | [16,48,57,58] | Increased vulnerability of restoration projects, difficulty in maintaining ecological stability, and increased risk of project failure. |

| Lack of Long-Term Commitment | Short-term project funding and lack of sustained engagement from stakeholders | [3,8,14,26] | Reduced impact and sustainability of restoration efforts, with projects often losing momentum once initial funding ends. |

| Technological Barriers | Limited access to or knowledge of modern restoration techniques and tools | [4,45,54,59] | Hindered implementation of effective restoration practices, reliance on outdated methods, and reduced innovation. |

| Lack of Local Leadership | Insufficient development of local leadership capacities to drive restoration initiatives | [3,9,29,44] | Lowered project effectiveness, lack of local ownership, and decreased long-term sustainability of restoration projects. |

3.4. Impact of Social Inclusion Projects on Ecological Resilience and Human Well-Being

Restoration projects play a crucial role in enhancing the resilience and functionality of both human and ecological systems. Ecologically, these projects contribute to the recovery and maintenance of vital ecosystem services such as soil fertility, water regulation, and biodiversity. By restoring degraded rangelands, we support the re-establishment of native vegetation and wildlife, which in turn improves ecosystem stability and resilience to environmental stressors. Human systems also benefit significantly from restoration efforts. Improved ecological conditions lead to enhanced livelihoods through increased agricultural productivity, better access to natural resources, and reduced vulnerability to climate change. Restoration projects often provide economic opportunities and support community well-being by fostering sustainable land management practices and strengthening local governance structures. Table 5 outlines the outcomes of social inclusion in rangeland restoration, highlighting the multifaceted benefits that arise from engaging communities in these efforts. These outcomes include ecological resilience, social equity, community empowerment, strengthened governance, and more, each supported by relevant studies and examples. Ecological resilience refers to the capacity of an ecosystem to recover from disturbances and maintain its functions. Studies by Basupi et al. [30], Djnontin et al. [17], Ngwenya et al. [3], and Nyirenda et al. [34] show that social inclusion in rangeland restoration leads to improved vegetation cover, soil health, and biodiversity. These improvements contribute to a more stable and sustainable ecosystem. For example, the restoration of native plant species and reduction in soil erosion enhance the land’s ability to withstand environmental stressors. The literature supports the idea that diverse ecosystems are more resilient to changes, such as those caused by climate variability, and are better equipped to provide essential services like water filtration and carbon sequestration [53]. Social equity involves ensuring fair access to resources and decision-making processes, especially for marginalized groups. The studies by Kwaza et al. [58], Dube et al. [61], Dreber et al. [42], Finca et al. [22], and Gwimbi [31] report that inclusive restoration practices lead to a greater representation of women and marginalized groups in leadership roles, promoting fairness and inclusivity. For instance, equitable resource distribution and increased social justice are key outcomes of these efforts. The literature emphasizes that social equity is not only a moral imperative but also crucial for the sustainability of environmental projects, as it fosters broader community support and reduces resistance [30,62].

Table 5.

Outcomes of social inclusion in rangeland restoration.

Community empowerment refers to the process of increasing the capacity, agency, and self-determination of local communities in managing and sustaining restoration projects. Herrera and Davies [15], Mairomi and Kimengsi [13], Milton et al. [36], Moyo et al. [25], Ngwenya et al. [3], and Perkins et al. [9] demonstrate that when communities take ownership of restoration projects, they lead local initiatives and develop self-sustaining practices. This empowerment is crucial for the long-term success of restoration efforts, as it ensures that the community remains engaged and invested in the project’s outcomes. The literature supports this by highlighting that community-driven projects are more likely to be sustained over time, as they align with the local population’s values and priorities [59]. Strengthened governance refers to the development of inclusive and representative governance structures that ensure the participation of all community members in decision making. Studies by Reed et al. [6], McGranahan and Kirkman [27], Herrera and Davies [15], and Abdulahi et al. [54] highlight the formation of community councils and better coordination among stakeholders as key outcomes of inclusive governance. These structures improve transparency in project management and enhance the effectiveness of restoration efforts. The literature emphasizes that good governance is critical for the success of environmental projects, as it ensures accountability, transparency, and stakeholder engagement [44]. Knowledge exchange involves the effective integration and utilization of local and indigenous knowledge in restoration practices. Studies by Simba et al. [41], Safari et al. [48], Rohde et al. [35], and Stringer et al. [14] demonstrate that such integration leads to more culturally and ecologically appropriate outcomes. For example, the use of traditional grazing practices and adaptation of indigenous land management strategies have been shown to improve restoration success. The literature supports this by emphasizing the value of indigenous knowledge in enhancing the resilience and sustainability of environmental practices [36].

Increased biodiversity is a direct outcome of effective rangeland restoration, which contributes to a balanced ecosystem. Studies by Teketay et al. [40], Siangulube et al. [7], Vetter [21], Reed et al. [1], and Perkins et al. [9] report the reintroduction of native species, preservation of endangered species, and improvement in habitat diversity. Biodiversity is crucial for ecosystem stability and function, providing resilience against environmental changes and contributing to the overall health of the ecosystem [4]. The literature further supports that diverse ecosystems are better able to provide a range of services that benefit both nature and human communities [3]. Enhanced livelihoods refer to the improved economic and social well-being of local communities through the sustainable use of rangelands. Herrera and Davies [15], Mairomi and Kimengsi [13], Milton et al. [36], and Moyo et al. [25] highlight how restoration activities can lead to increased income from sustainable land use practices, the diversification of livelihoods, and reduced vulnerability to climate change. The literature underscores that environmental restoration projects that are inclusive and community-driven can lead to economic benefits, such as improved agricultural productivity and new income-generating opportunities [9]. Increased social cohesion involves strengthening social ties and collaboration within and between communities, leading to more effective collective action. Basupi et al. [30], Djnontin et al. [17], Ngwenya et al. [3], Moyo and Ravhuhali [29], and Atsbha et al. [44] report that social inclusion in restoration projects fosters community-driven initiatives, collaborative decision making, and reduced conflict over land use and resource allocation. Social cohesion is essential for the success of communal projects, as it facilitates cooperation, trust, and mutual support among community members [15,32].

Long-term sustainability ensures the continued success and maintenance of restoration efforts beyond the initial project phase. Studies by Bennet and Barreti [37], Dougill and Reed [17], Finca et al. [22], Moyo et al. [25], and Ngwenya et al. [3] demonstrate that sustainable practices, ongoing monitoring and evaluation, and the creation of resilient systems are key outcomes of social inclusion in restoration projects. The literature emphasizes that long-term sustainability is achieved when projects are designed to be adaptive, resilient, and aligned with the community’s long-term goals and capacities [1]. Improved well-being refers to the holistic enhancement of the physical, social, and economic well-being of community members through restoration activities. Herrera and Davies [15], Milton et al. [36], Moyo and Ravhuhali [29], Nyirenda et al. [34], and Reed et al. [6] highlight outcomes such as improved health, increased access to clean water and food, and an overall better quality of life. The literature supports the idea that environmental restoration projects that are inclusive and community focused can lead to significant improvements in well-being, as they address both ecological and social determinants of health [38]. In conclusion, the outcomes of social inclusion in rangeland restoration are far-reaching and multifaceted, enhancing not only the ecological resilience of rangelands but also the social and economic well-being of local communities. These outcomes underscore the importance of inclusive practices in environmental restoration, as they contribute to the sustainability and success of restoration efforts while promoting equity and justice. By integrating local knowledge, fostering community empowerment, and ensuring long-term commitment, rangeland restoration projects can achieve significant and lasting positive impacts.

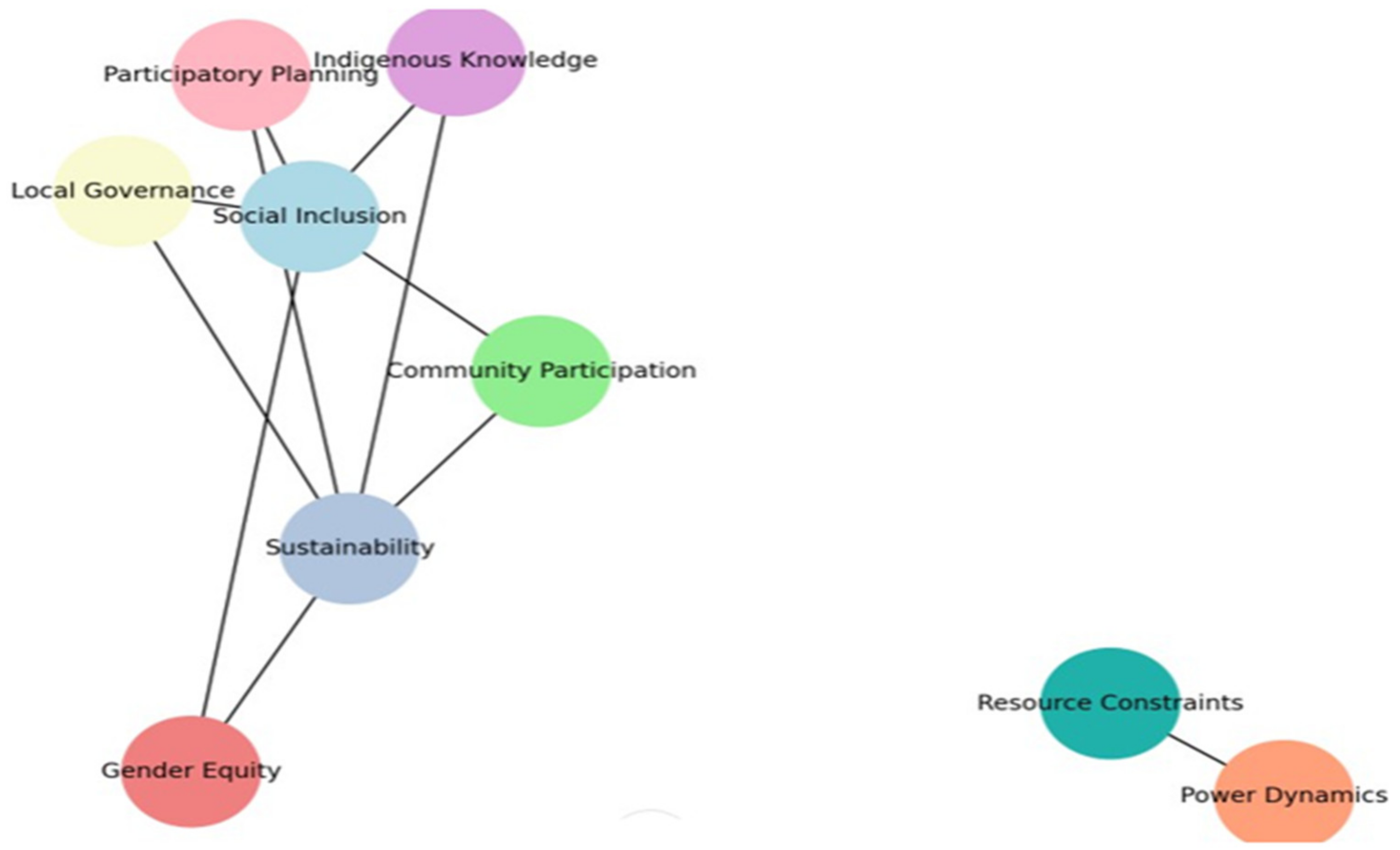

3.5. Key Themes Generated from the Word Cloud

The word cloud in Figure 2 highlights key themes of social inclusion in rangeland restoration. These themes include community participation, participatory planning, and local governance. These concepts are crucial for successful and sustainable rangeland restoration, especially when social dynamics and ecological challenges are interconnected. The word “Social Inclusion” is at the center of the cloud, emphasizing its critical role in involving all community members, particularly marginalized groups, in restoration projects. Social inclusion promotes equity, integrates diverse perspectives and knowledge systems, and is fundamental to effective and sustainable outcomes [15,39]. “Community Participation” reinforces the idea that the engagement of local communities in decision-making and implementation processes is vital for restoration success. Projects with strong community participation tend to be more sustainable and achieve better ecological outcomes because they foster a sense of ownership and responsibility among community members [12,64]. “Participatory Planning” and “Local Governance” are also important themes in the word cloud, reflecting the significance of collaboration in restoration projects. Participatory planning ensures that restoration efforts are culturally appropriate and locally relevant by involving stakeholders in the planning and management processes. This approach enhances project legitimacy and effectiveness by incorporating local knowledge and expertise [4,36].

Figure 2.

A word cloud was generated using the 29 most frequently used words in the abstracts of the 20 articles included in the review.

Strong local governance is crucial for the long-term sustainability of restoration projects. When local institutions are inclusive and representative, they can better manage resources, resolve conflicts, and adapt to changing conditions. The literature highlights that well-governed projects are more likely to succeed because they ensure transparency, accountability, and the equitable distribution of benefits [9,34]. The word cloud shows that “Gender Equity” and “Indigenous Knowledge” are important aspects to consider in restoration projects. Gender equity ensures that women, who play a significant role in natural resource management, have equal opportunities to participate and benefit from restoration efforts. This is crucial because gender-inclusive projects tend to have more holistic and inclusive outcomes [1,35]. Indigenous knowledge is also valuable in rangeland restoration, as it offers sustainable and culturally appropriate practices and insights. Integrating indigenous knowledge into restoration efforts can lead to more resilient and adaptable ecosystems as well as stronger community ties and cultural preservation [10,48]. The word cloud also includes terms like “Power Dynamics”, “Cultural Norms”, and “Resource Constraints”, which reflect the challenges in achieving social inclusion in rangeland restoration. Power dynamics and cultural norms can create barriers to participation for certain groups, particularly women and marginalized communities. Addressing these challenges requires a deliberate effort to build capacity, foster inclusive governance, and create supportive environments for all stakeholders [10,11]. In conclusion, the word cloud highlights the interrelated themes of social inclusion, community participation, participatory planning, and local governance as crucial components of successful rangeland restoration. Addressing challenges such as power dynamics and resource constraints while promoting gender equity and integrating indigenous knowledge are key to achieving sustainable and equitable restoration outcomes. These findings are supported by a growing body of literature that emphasizes the importance of inclusive and participatory approaches in environmental management and restoration.

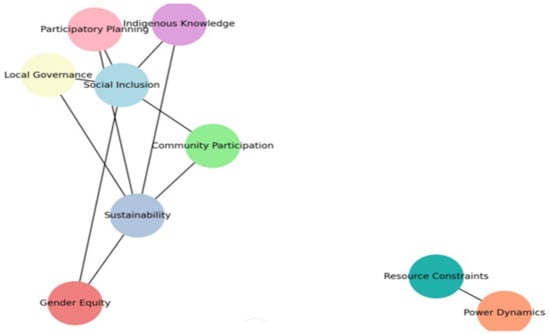

3.6. Key Themes Generation from the Co-Occurrence Networks

Figure 3 is a network graph that illustrates the connections between various concepts related to social inclusion and rangeland restoration. The positioning of these concepts, their proximity to one another, and the connections between them all provide insight into the relationships and influences among the different themes. At the heart of the network, we find “Social Inclusion” and “Community Participation” closely linked, which emphasizes the fundamental role that inclusive community engagement plays in effective rangeland restoration. Research has shown that inclusive participation leads to better project outcomes because it empowers local communities and ensures that their needs and knowledge are integrated into restoration strategies [1,16]. “Participatory Planning” and “Local Governance” are also positioned centrally, highlighting the importance of structured and inclusive decision-making processes. Participatory planning ensures that restoration efforts are guided by local knowledge and priorities, while strong local governance structures are crucial for sustaining these efforts and ensuring equity and transparency [3,7]. Meanwhile, “Capacity Building” and “Resource Constraints” are interrelated and situated slightly on the outskirts of the central concepts. This suggests that building local capacity is vital for overcoming resource constraints, which are often common challenges in rangeland restoration projects. Through capacity building, communities acquire the necessary skills and knowledge to effectively manage restoration efforts, while addressing resource constraints guarantees the feasibility and sustainability of these projects [2,64].

Figure 3.

Co-occurrence network of the words on the abstracts from the 20 articles included in the review.

On the other hand, “Marginalized Groups” and “Power Dynamics” are positioned further away from the core cluster, possibly indicating the difficulties associated with these factors in achieving social inclusion. Power dynamics frequently marginalize certain groups, preventing them from fully participating in restoration efforts. It is crucial to address these power imbalances to ensure that all community members, particularly those who are marginalized, can contribute to and benefit from restoration activities [44,54]. “Cultural Norms” and “Stakeholder Engagement” are also linked, suggesting that cultural contexts significantly influence how stakeholders engage with restoration projects. Respecting and integrating cultural norms into project planning can enhance stakeholder engagement and support the overall success of restoration initiatives [30,51]. “Ecological Resilience” and “Indigenous Knowledge” are clustered together, indicating that integrating indigenous knowledge can enhance the ecological resilience of rangelands. Indigenous practices often provide sustainable land management techniques that contribute to the restoration of degraded ecosystems, making them more resilient to environmental stressors [2,25].

3.7. Contribution to the Field and Potential Limitations

This review contributes to the existing literature by providing a comprehensive analysis of the role of social inclusion in restoring communal rangelands in southern Africa. While much of the prior research has focused on technical and ecological approaches to rangeland restoration, this study shifts the focus toward the social dimensions, particularly how marginalized communities can be included in the process. It highlights the significance of participatory governance, local knowledge, and stakeholder engagement as essential components of sustainable restoration. By examining diverse case studies, this review provides insights into the challenges faced by marginalized groups and explores how gender equity and cultural norms impact restoration efforts. When considering the potential limitations of the paper, several aspects come to light that may affect the overall robustness and generalizability of the findings. Firstly, the reliance on secondary data sources, particularly those extracted from existing literature, may limit the scope and depth of the analysis. This dependence on previously published studies may introduce biases inherent in those studies, such as sampling biases, methodological inconsistencies, or the influence of publication bias where only positive or significant results are reported. Consequently, the findings might reflect the limitations of the sources used rather than a fully comprehensive understanding of the topic. Secondly, the geographical focus of the paper, which centers on Sub-Saharan Africa, presents both strengths and limitations. While the regional focus allows for a detailed examination of local contexts and challenges, it also limits the generalizability of the findings to other regions with different socio-ecological dynamics. The unique environmental, cultural, and socio-economic conditions in Sub-Saharan Africa mean that the lessons learned and strategies proposed may not be directly applicable or effective in other regions, particularly in areas with different climatic conditions or socio-political structures.

Additionally, the use of systematic review methodology, while rigorous, can sometimes lead to the exclusion of relevant studies that do not fit the predefined criteria. For instance, qualitative studies or gray literature that provide valuable insights but do not adhere to traditional academic standards may be overlooked. This could result in an incomplete picture of the available evidence and potentially limit the paper’s conclusions. Another limitation could be the potential for subjectivity in the interpretation of qualitative data especially in the context of social inclusion and community participation. The paper’s analysis of social dynamics, such as power structures and cultural norms, is inherently complex and context specific. The subjective nature of these concepts means that different researchers might interpret the same data in different ways, potentially leading to varying conclusions. The paper may also face limitations related to the temporal scope of the studies reviewed. Many of the sources may reflect historical data or past case studies, which might not fully capture the current realities or recent developments in rangeland restoration and social inclusion practices. This temporal gap could affect the relevance of the findings, especially in the rapidly changing socio-political and environmental contexts of Sub-Saharan Africa. Lastly, there is the challenge of measuring and evaluating social outcomes, such as empowerment, equity, and social cohesion. These outcomes are often subjective and can be difficult to quantify or compare across different studies. The paper’s reliance on reported outcomes from various studies might therefore struggle to provide a consistent or universally applicable framework for assessing the success of social inclusion in rangeland restoration. In summary, while the paper provides valuable insights into the role of social inclusion in rangeland restoration, these potential limitations should be acknowledged. These include the reliance on secondary data, regional specificity, potential exclusion of relevant literature, subjectivity in qualitative analysis, temporal scope, and the challenges of measuring social outcomes. Recognizing these limitations is crucial for contextualizing the findings and understanding their applicability in broader or different contexts.

3.8. Identified Gaps in the Literature and Suggestions for Future Research

Despite significant progress in understanding the importance of social inclusion in rangeland restoration, several critical gaps remain that must be addressed to enhance the effectiveness and sustainability of these initiatives. One of the most persistent challenges is the entrenched power dynamics that hinder the full participation of marginalized groups. While research frequently acknowledges power imbalances, there is a need for more practical approaches that actively dismantle these barriers. Understanding the nuances of power relations within communities and integrating power-sensitive frameworks into restoration practices is crucial. Cultural norms and indigenous knowledge are recognized as key elements of successful restoration efforts, but their integration into mainstream restoration strategies remains limited. More empirical research is needed to document and validate indigenous practices alongside methodologies that effectively incorporate these practices into broader restoration frameworks. Additionally, many restoration projects face challenges in maintaining long-term community engagement, particularly after initial funding and external support ends. Resource constraints and insufficient capacity building often exacerbate these issues, underscoring the need for research on sustainable financing models and capacity development that ensure ongoing community involvement. While social equity is a desired outcome of social inclusion, there is limited research on the specific mechanisms for achieving equity in restoration projects. More studies are needed to explore how women and marginalized communities can gain equitable access to resources and decision-making processes. The role of modern technology in supporting social inclusion in rangeland restoration is also underexplored. Technological tools could enhance the communication, knowledge sharing, and monitoring of restoration efforts, but little research has examined how these tools can be made accessible and relevant to remote communities.

Future research should focus on interventions that address power imbalances in specific cultural and community contexts. Participatory action research that engages communities in identifying and overcoming power-related barriers to inclusion could be a productive approach. Collaborative research with indigenous communities is also necessary to co-create culturally appropriate and scientifically sound restoration strategies. This includes documenting successful indigenous practices, exploring their scalability, and creating policy frameworks that support their integration into formal restoration programs. Innovative models for sustaining community engagement, such as community-based financing, revolving funds, and public–private partnerships, require further exploration to ensure continuous support for restoration projects. Research should also examine the role of local leadership development in maintaining project momentum and ownership. Addressing social equity gaps requires the development of genuinely inclusive and representative governance structures. Future research should explore different models of participatory governance and evaluate their effectiveness in promoting equitable outcomes across social groups. Additionally, the role of digital tools, such as mobile applications, GIS mapping, and online platforms, should be investigated to assess their impact on community participation and knowledge sharing in restoration efforts. By addressing gaps in power dynamics, cultural integration, long-term engagement, social equity, and technological innovation, future research and practice can foster more inclusive and sustainable restoration outcomes. Ongoing commitment to these areas will ensure that rangeland restoration efforts are not only ecologically successful but also socially just and resilient.

Moreover, this review has revealed several gaps in the literature. There is a lack of studies focusing on the long-term socio-ecological impacts of restoration projects, particularly in communal lands. Most research emphasizes short-term ecological improvements, with limited exploration of how social inclusion contributes to community resilience and ecological sustainability over time. In addition, more in-depth research is needed on how power dynamics shape restoration outcomes, particularly the interactions between marginalized groups and dominant stakeholders, such as government bodies and NGOs. Geographic biases in existing research further limit our understanding. While there is substantial research from countries like South Africa and Namibia, regions with significant communal rangelands, such as Zimbabwe, Mozambique, and Botswana, are underrepresented. This geographical bias limits the generalizability of findings and leaves key ecosystems and social structures underexplored. Future research should address these gaps by conducting longitudinal studies on the socio-ecological impacts of communal rangeland restoration. Such research would provide valuable insights into the sustainability of restoration efforts and the long-term benefits for both human and ecological systems. Additionally, research should examine how power dynamics, gender equity, and resource allocation intersect, particularly in areas where local governance structures are weak or contested. There is also an opportunity to explore innovative restoration techniques that integrate modern ecological science with indigenous knowledge. Future studies should investigate how these hybrid approaches can be scaled to larger communal landscapes and how they can contribute to more resilient rangelands in the face of climate change and other environmental challenges. Finally, expanding the geographic scope of research is crucial for providing a more holistic understanding of communal rangeland restoration across southern Africa. Comparative studies across different countries and ecosystems will yield valuable lessons on what works in various socio-ecological contexts, informing policy and practice across the region.

4. Conclusions

This paper highlights the importance of social inclusion in the restoration of rangelands, specifically in southern Africa. After examining the existing literature, it is evident that incorporating diverse community perspectives is vital for achieving ecological outcomes that are sustainable and resilient. This includes considering the viewpoints of marginalized groups such as women and indigenous peoples. The findings emphasize that participatory planning, gender-inclusive strategies, and the integration of indigenous knowledge are not just supplementary elements but rather essential pillars for successful restoration initiatives. Moreover, the paper demonstrates the interconnectedness between social equity, community empowerment, strengthened governance, ecological resilience, and improved livelihoods. These outcomes showcase the broader advantages that result from inclusive and participatory restoration efforts, fostering a sense of ownership and commitment among community members. However, the research also acknowledges the significant challenges that persist, such as power dynamics, cultural norms, resource limitations, and institutional barriers. These obstacles can impede effective social inclusion and, consequently, the success of restoration projects. Moving forward, it is crucial for future research and policy development to address these challenges by designing context-specific, flexible, and responsive strategies that consider the dynamic social and environmental landscapes of Sub-Saharan Africa. The focus should be on establishing robust frameworks for monitoring and evaluation to ensure that social outcomes are adequately measured and that restoration efforts remain adaptable to changing conditions. Additionally, sustained investment in capacity building, technological advancement, and the empowerment of local leadership is necessary to drive long-term sustainability.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: M.S., K.H.T., L.Z. and P.N.; data curation: M.S.; analysis: M.S.; visualization: M.S.; writing the original draft: M.S.; manuscript editing: L.Z., K.H.T. and P.N. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The authors acknowledge the financial support provided by the National Research Foundation, grant number TS64 (UID: 99787).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express their gratitude to their colleagues from the Centre for Global Change (CGC) and the Department of Livestock and Pasture Science at the University of Fort Hare for providing valuable feedback and assistance in the development of this manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no commercial or financial relationships that could be perceived as a potential conflict of interest in this research.

References

- Reed, M.S.; Stringer, L.C.; Dougill, A.J.; Perkins, J.S.; Atlhopheng, J.R.; Mulale, K.; Favretto, N. Reorienting land degradation towards sustainable land management: Linking sustainable livelihoods with ecosystem services in rangeland systems. J. Environ. Manag. 2015, 151, 472–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gxasheka, M.; Beyene, S.T.; Mlisa, N.L.; Lesoli, M. Farmers’ perceptions of vegetation change, rangeland condition and degradation in three communal grasslands of South Africa. Trop. Ecol. 2017, 58, 217–228. [Google Scholar]

- Ngwenya, B.N.; Thakadu, O.T.; Magole, L.; Chimbari, M.J. Memories of environmental change and local adaptations among molapo farming communities in the Okavango Delta, Botswana—A gender perspective. Acta Trop. 2017, 175, 31–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mureithi, S.M.; Verdoodt, A.; Van Ranst, E. Effects and implications of enclosures for rehabilitating degraded semi-arid rangelands: Critical lessons from Lake Baringo Basin, Kenya. In Land Degradation and Desertification: Assessment, Mitigation and Remediation; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2010; pp. 111–129. [Google Scholar]

- Slayi, M.; Zhou, L.; Dzvene, A.R.; Mpanyaro, Z. Drivers and Consequences of Land Degradation on Livestock Productivity in Sub-Saharan Africa: A Systematic Literature Review. Land 2024, 13, 1402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reed, M.S.; Dougill, A.J.; Taylor, M.J. Integrating local and scientific knowledge for adaptation to land degradation: Kalahari rangeland management options. Land Degrad. Dev. 2007, 18, 249–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siangulube, F.S.; Ros-Tonen, M.A.; Reed, J.; Bayala, E.R.C.; Sunderland, T. Spatial tools for inclusive landscape governance: Negotiating land use, land-cover change, and future landscape scenarios in two multistakeholder platforms in Zambia. Land 2023, 12, 804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senda, T.S.; Robinson, L.W.; Gachene, C.K.; Kironchi, G. Formalization of communal land tenure and expectations for pastoralist livelihoods. Land Use Policy 2022, 114, 105961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perkins, J.; Reed, M.; Akanyang, L.; Atlhopheng, J.; Chanda, R.; Magole, L.; Mphinyane, W.; Mulale, K.; Sebego, R.; Fleskens, L.; et al. Making land management more sustainable: Experience implementing a new methodological framework in Botswana. Land Degrad. Dev. 2013, 24, 463–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyahunda, L.; Tirivangasi, H.M. Harnessing of social capital as a determinant for climate change adaptation in Mazungunye communal lands in Bikita, Zimbabwe. Scientifica 2021, 2021, 8416410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peel, M.; Stalmans, M. The effect of Holistic Planned Grazing™ on African rangelands: A case study from Zimbabwe. Afr. J. Range Forage Sci. 2018, 35, 23–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mbaiwa, J.E.; Mbaiwa, T.; Siphambe, G. The community-based natural resource management programme in southern Africa–promise or peril?: The case of Botswana. In Positive Tourism in Africa; Routledge: London, UK, 2019; pp. 11–22. [Google Scholar]

- Mairomi, H.W.; Kimengsi, J.N. Community-based actors and participation in rangeland management. lessons from the western highlands of cameroon. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stringer, L.C.; Twyman, C.; Thomas, D.S. Combating land degradation through participatory means: The case of Swaziland. AMBIO A J. Hum. Environ. 2007, 36, 387–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrera, P.M.; Davies, J. Rebuilding pastoral governance: Lessons learnt and conclusions. In The Governance of Rangelands; Routledge: London, UK, 2014; pp. 258–281. [Google Scholar]

- Mashinini, V.; De Villiers, G. Community-based range resource management for sustainable agriculture in Lesotho: Implications for South Africa. Afr. Insight 2004, 34, 40–45. [Google Scholar]

- Djenontin, I.N.; Ligmann-Zielinska, A.; Zulu, L.C. Landscape-scale effects of farmers’ restoration decision making and investments in central Malawi: An agent-based modeling approach. J. Land Use Sci. 2022, 17, 281–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monroe, M.C.; Plate, R.R.; Oxarart, A.; Bowers, A.; Chaves, W.A. Identifying Effective Climate Change Education Strategies: A Systematic Review of the Research. Environ. Edu. Res. 2017, 25, 781–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2021; Available online: https://www.R.-project.org/ (accessed on 18 April 2024).

- Cobo, M.J.; López-Herrera, A.G.; Herrera-Viedma, E.; Herrera, F. An approach for detecting, quantifying, and visualizing the evolution of a research feld: A practical application to the Fuzzy Sets Theory feld. J. Inf. 2011, 5, 146–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Eck, N.J.; Waltman, L. Visualizing bibliometric networks. In Measuring Scholarly Impact: Methods and Practice; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2014; pp. 285–320. [Google Scholar]

- Finca, A.; Linnane, S.; Slinger, J.; Getty, D.; Samuels, M.I.; Timpong-Jones, E.C. Implications of the breakdown in the indigenous knowledge system for rangeland management and policy: A case study from the Eastern Cape in South Africa. Afr. J. Range Forage Sci. 2023, 40, 47–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heita, H.T.; Dressler, G.; Schwieger, D.A.M.; Mbidzo, M. Pastoralists’ perceptions on the future of cattle farming amidst rangeland degradation: A case study from Namibia’s semiarid communal areas. Rangelands 2024, 46, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pretty, J.; Smith, D. Social capital in biodiversity conservation and management. Conserv. Biol. 2004, 18, 631–638. [Google Scholar]

- Moyo, B.; Dube, S.; Moyo, P. Rangeland management and drought coping strategies for livestock farmers in the semi-arid savanna communal areas of Zimbabwe. J. Hum. Ecol. 2013, 44, 9–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vetter, S. Development and sustainable management of rangeland commons—Aligning policy with the realities of South Africa’s rural landscape. Afr. J. Range Forage Sci. 2013, 30, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGranahan, D.A.; Kirkman, K.P. Multifunctional rangeland in Southern Africa: Managing for production, conservation, and resilience with fire and grazing. Land 2013, 2, 176–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allsopp, N.; Laurent, C.; Debeaudoin, L.M.; Samuels, M.I. Environmental perceptions and practices of livestock keepers on the Namaqualand Commons challenge conventional rangeland management. J. Arid. Environ. 2007, 70, 740–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moyo, B.; Ravhuhali, K.E. Abandoned croplands: Drivers and secondary succession trajectories under livestock grazing in communal areas of South Africa. Sustainability 2022, 14, 6168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]