Land Titling: A Catalyst for Enhancing China Rural Laborers’ Mobility Intentions?

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Policy Background

1.2. Literature Review

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Sources

2.2. Definition of Varibles

2.3. Modeling

3. Results

3.1. Benchmark Regression Results

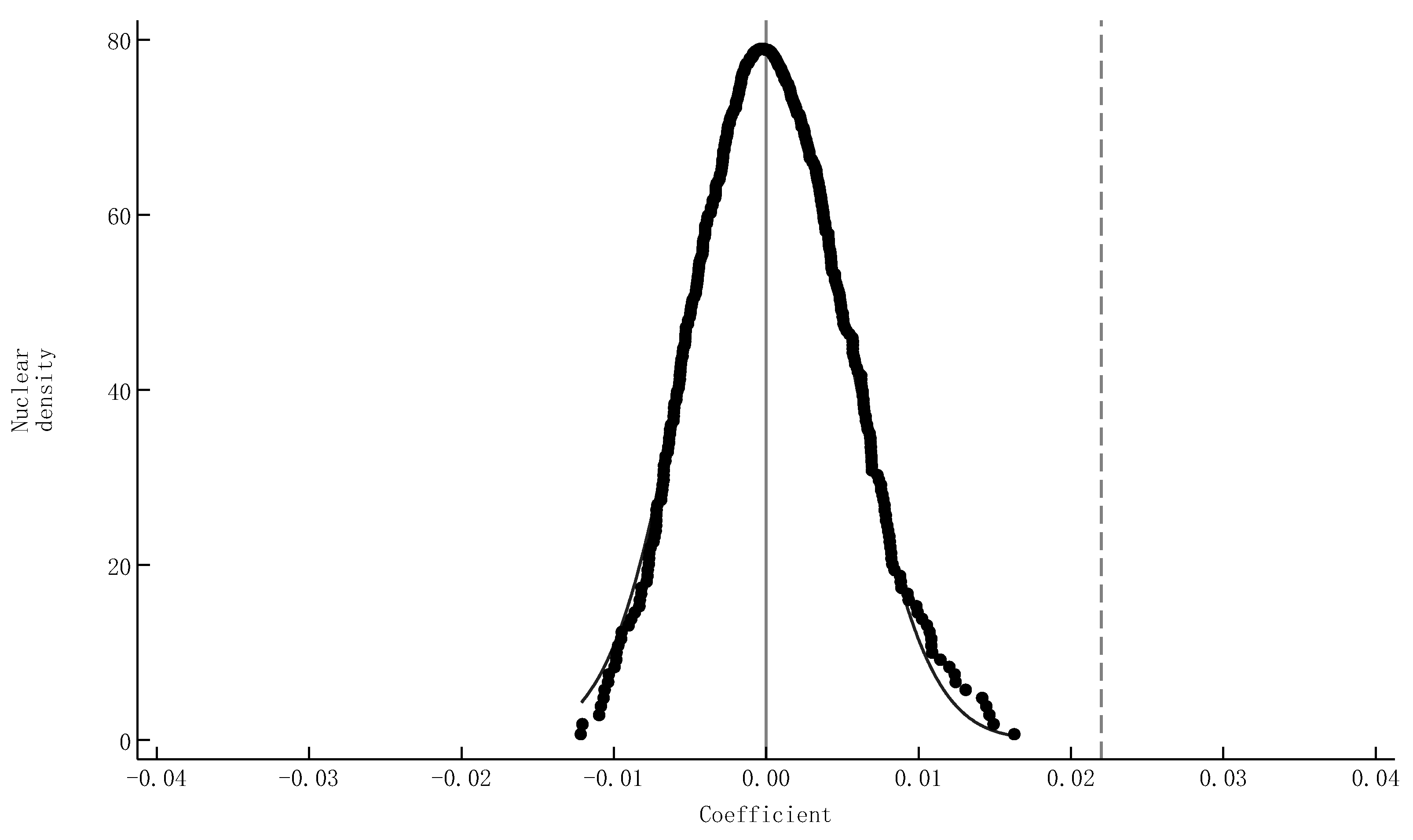

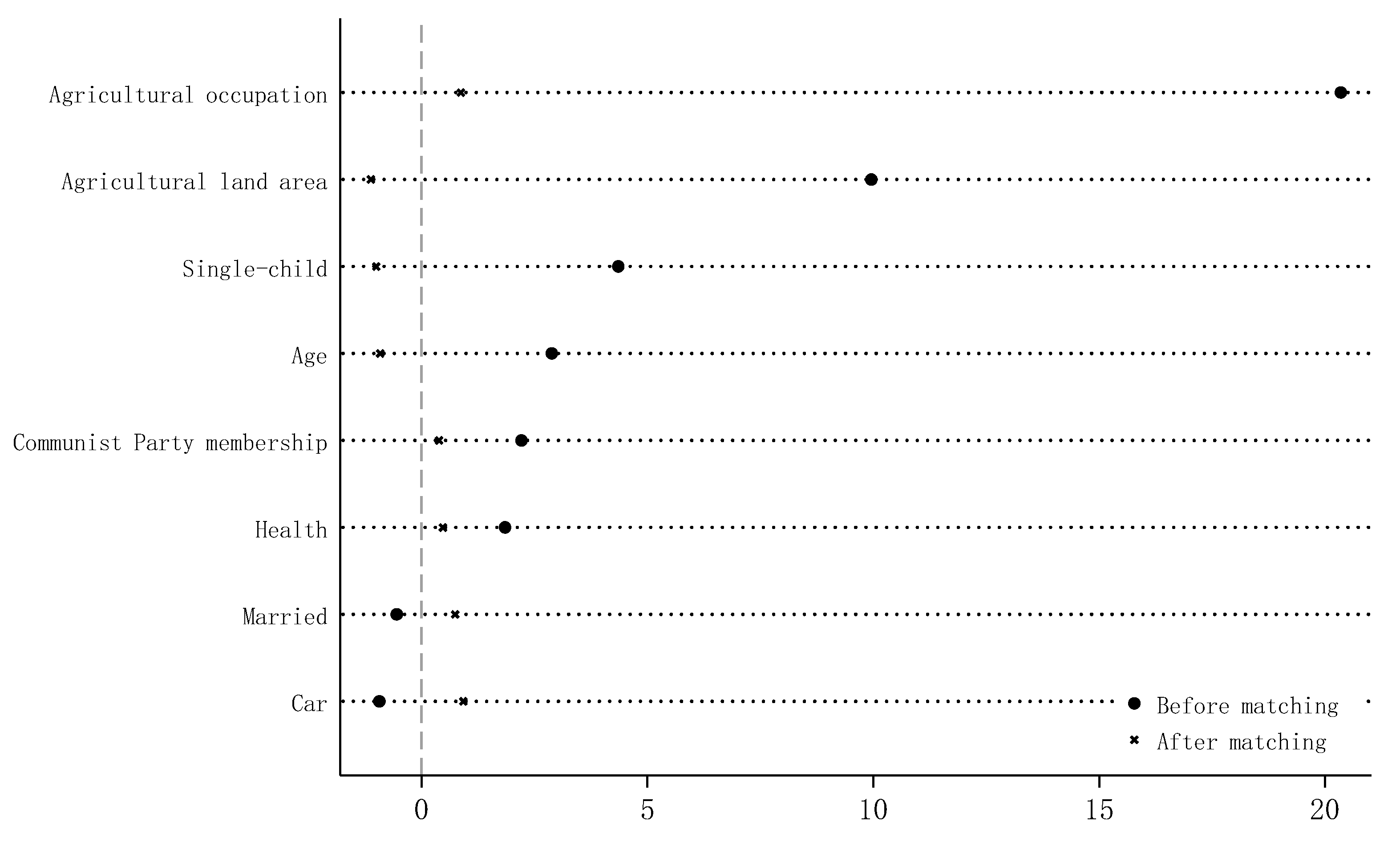

3.2. Robustness Tests

3.3. Mechanism Analysis

3.4. Heterogeneity Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Xiang, J.; Zhong, F.N. Rural Population Transfer, Industrialization, and Urbanization. Issues Agric. Econ. 2018, 12, 51–56. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, Y.; Ye, X.Q.; Jie, M.Y. Prominent Issues and Policy Recommendations for Citizenization of Agricultural Transfer Population. Econ. Horiz. 2023, 6, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Jia, X.J.; Cheng, M.W. Inter-provincial Transfer of Rural Labor Force in China (1978–2021): Quantitative Estimation and Spatiotemporal Characteristics. China Rural Econ. 2024, 6, 72–93. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, H.K.; Ye, X.Q.; Du, Z.X.; Qian, W.R.; Lu, Y.H. Accelerating the Construction of a New Development Pattern and Promoting High-quality Development of Agriculture and Rural Areas: In-depth Interpretation of the 20th National Congress of the Communist Party of China by Authoritative Experts. China Rural Econ. 2022, 12, 2–34. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, L.Y.; Li, Y.Y.; Qian, W.R. Has Land Titling Promoted Agricultural Scale Management in China? Empirical Analysis Based on CRHPS. China Econ. Q. 2023, 23, 447–463. [Google Scholar]

- Chernina, E.; Dower, P.C.; Markevich, A. Property Rights, Land Liquidity, and Internal Migration. J. Dev. Econ. 2014, 110, 191–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valsecchi, M. Land Property Rights and International Migration: Evidence from Mexico. J. Dev. Econ. 2014, 110, 276–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.B.; Liu, S.Y. The Impact of Land Titling on Rural Labor Transfer Employment: Evidence from CHARLS. Popul. Econ. 2019, 5, 41–52. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, M.J.; Shen, X.L. Land Titling and Rural Labor Employment Choices: Empirical Analysis Based on CLDS Data. S. China Popul. 2021, 36, 37–51. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, W.K.; Bai, C.E.; Xie, P.C. The Impact of Household Registration System Reform on Rural Labor Mobility in China. Econ. Res. J. 2011, 46, 28–41. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, L.G.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, Z.B. Has Land Titling Promoted Rural Land Transfer in China? Manag. World 2016, 1, 88–98. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, F.; Xing, X.C.; Li, H.X. A Review of Urban-Rural Labor Mobility: Theories and Empirical Evidence from China. China Popul. Resour. Environ. 2015, 25, 163–170. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Z.H.; Du, X.J. Do Rural Land Institutions Hinder Migrant Workers’ Citizenization? An Extended Todaro Model and Empirical Analysis of Yiwu City. China Land Sci. 2014, 28, 31–38. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Y.H.; Fan, G.Z. The Impact of Land Titling on Farmers’ Non-agricultural Employment: Analysis Based on Rural Land System and Financial Environment. J. Agrotech. Econ. 2020, 5, 93–106. [Google Scholar]

- De Janvry, A.; Emerick, K.; Gonzalez, M.; Sadoulet, E. Delinking Land Rights from Land Use: Certification and Migration in Mexico. Am. Econ. Rev. 2015, 105, 3125–3149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, C.L.; Zhang, Y. Land Titling and Rural Labor Migration: Evidence from Provincial Panel Data. Resour. Sci. 2022, 44, 647–659. [Google Scholar]

- Hong, W.J.; Hu, X.Y. How Land Tenure Security Affects Rural Labor Non-agricultural Transfer: Analysis Based on Extended Todaro Model. Financ. Trade Res. 2019, 30, 60–70. [Google Scholar]

- Li, L.; Zhang, Y.Y.; Zhang, A.L. The Impact of Land Titling on Migrant Workers’ Citizenization: Empirical Analysis and Verification. China Popul. Resour. Environ. 2023, 33, 153–164. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, C.; Luo, M.Z.; Zhang, W.K. How Does Land Titling Mode Affect Agricultural Population’s Willingness for Citizenization? Agric. Econ. Manag. 2020, 3, 53–63. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, S.; Ma, S.; Yin, L.; Zhu, J. Land Titling, Human Capital Misallocation, and Agricultural Productivity in China. J. Dev. Econ. 2023, 165, 103165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, T.W.; Luo, B.L. Does Farmland Adjustment Inhibit Rural Labor Non-agricultural Transfer? China Rural Surv. 2017, 4, 57–71. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, L.; Jiang, Y.; Ye, J.P.; Zhu, K.L. Farmers’ Attitudes in the Institutional Change of Rural Land Adjustment in China: Empirical Analysis Based on 17 Provinces’ Surveys from 1999 to 2010. Manag. World 2013, 7, 44–58. [Google Scholar]

- Yao, Y. Induced Institutional Change under Collective Decision-Making: Empirical Analysis of the Evolution of Land Rights Stability in Rural China. China Rural Surv. 2000, 2, 11–19+80. [Google Scholar]

- Geng, P.P.; Luo, B.L. Balance Between “Constraint” and “Compensation”: How Land Adjustment Affects the Efficiency Determinants of Titling. China Rural Surv. 2021, 2, 61–80. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, L.L.; Yang, H.; Zheng, H.T. The Impact of Land Titling on Chinese Farmers’ Capital Investment: Micro Analysis Based on Heterogeneous Farmer Model. Econ. Res. J. 2020, 55, 156–173. [Google Scholar]

- Piza, C.; de Moura, M.J.S.B. The Effect of a Land Titling Programme on Households’ Access to Credit. J. Dev. Eff. 2016, 8, 129–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.Y. The Impact of Land Titling on Farmers’ Participation in Non-agricultural Labor. Econ. Sci. 2020, 1, 113–126. [Google Scholar]

- Weng, Y.Q.; Hu, X.Y. How Does Land Tenure Stability Affect Farmers’ Urban Migration Choices? Res. Financ. Econ. Issues 2023, 10, 44–52. [Google Scholar]

- Ferraro, P.J.; Hanauer, M.M. Advances in Quasi-Experimental Policy Impact Evaluation for Environmental and Resource Economics. Annu. Rev. Resour. Econ. 2023, 15, 291–315. [Google Scholar]

- Chetty, R.; Looney, A.; Kroft, K. Salience and Taxation: Theory and Evidence. Am. Econ. Rev. 2022, 99, 1145–1177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, K.R.; Jin, G. The Policy Effects of Local Government Environmental Governance in China: Research Based on the Evolution of “River Chief System”. Soc. Sci. China 2018, 5, 92–115+206. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, L.; Qian, W. The Impact of Land Certification on Cropland Abandonment: Evidence from Rural China. China Agric. Econ. Rev. 2021, 14, 509–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; He, W.; Liu, X.; Pei, L.; Li, Y.; Peng, X. Evaluation of the Implementation Effectiveness of Local Digital Economy Policies Based on PSM-DID. Mod. Inf. 2025, 45, 33–45. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, B.W.; Yang, F.X. The county-level economic growth effects of specialty agricultural development policy implementation: An evaluation based on China’s characteristic agricultural product advantage zones. China Rural Econ. 2024, 10, 132–152. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, C.; Zhang, W.D. The impact of new urbanization construction on regional economic development quality under the background of industrial structure upgrading: Evidence from PSM-DID empirical analysis. Ind. Econ. Res. 2018, 5, 78–88. [Google Scholar]

- Xia, Y.R.; Lu, M. “Mencius’ Mother Moving Three Times” Among Cities: Empirical Research on How Public Services Affect Labor Flow. Manag. World 2015, 10, 78–90. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, X.Y.; Zhang, L.X. Analysis of the Relationship Between Rural Land Property Rights Stability and Labor Transfer. China Rural Econ. 2008, 2, 29–39. [Google Scholar]

- Garcia, M.; Kim, S.; López, R. Urban Land Reform and Spatial Inequality: A Quasi-Experimental Analysis with Interactive Fixed Effects. Land Econ. 2022, 98, 567–589. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, T.H.; Tran, H.V. Tenure Security and Climate Adaptation: Evidence from Mekong Delta Land Titling Programs. World Dev. 2023, 161, 106112. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, L.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, Q. Land Titling and Rural Labor Mobility: Evidence from a Nationwide Panel in China. J. Dev. Econ. 2021, 152, 102686. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Z.M.; Qian, W.R. Research on Farmers’ Land Transfer Willingness Under Different Degrees of Part-time Farming: Based on Survey and Empirical Analysis in Zhejiang. Issues Agric. Econ. 2014, 35, 19–24+110. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Z.H.; Wang, Y.P.; Mairidan, T. Analysis of Farmers’ Cultivated Land Quality Conservation Investment Behavior and Influencing Factors: From the Perspective of Part-time Differentiation. China Popul. Resour. Environ. 2015, 25, 105–112. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, Z.C.; Liu, T.X.; Yan, Y. Can Labor Mobility Alleviate Farmers’ Liquidity Constraints? Empirical Analysis from the Perspective of Social Networks. China Rural Econ. 2021, 7, 65–83. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, L.Y.; Qian, W.R.; Liu, Q.; Guo, X.L. The Impact of New-round Land Titling on Cultivated Land Ecological Protection: Taking Fertilizer and Pesticide Application as Examples. China Rural Econ. 2021, 6, 76–93. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, T.M.; Guo, Y.N. New Round of Farmland Titling and Agricultural Productivity: A Perspective of New Agricultural Productive Forces. J. Financ. Res. 2025, 2, 50–66. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Q.; Li, W. Land Titling as Institutional Change: Evidence from China Labor Dynamics Survey. J. Shandong Univ. (Philos. Soc. Sci.) 2025, 1, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

| Variables | Definition | Mean | S.D. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rural laborer mobility intention | 1 = yes, 0 = no | 0.050 | 0.218 |

| Land titling | 1 = yes, 0 = no | 0.520 | 0.500 |

| Age | Years | 45.540 | 14.834 |

| Married | 1 = yes, 0 = no | 0.867 | 0.340 |

| Communist Party membership | 1 = yes, 0 = no | 0.054 | 0.226 |

| Health | Health status: 5 = very healthy, 4 = healthy, 3 = average, 2 = relatively unhealthy, 1 = very unhealthy | 3.581 | 1.029 |

| Car | 1 = yes, 0 = no | 0.170 | 0.376 |

| Single-child | 1 = yes, 0 = no | 0.075 | 0.263 |

| Agricultural occupation | 1 = yes, 0 = no | 0.706 | 0.456 |

| Agricultural land area | Total agricultural land area (acres) | 5683.154 | 7313.424 |

| Rural Laborer Mobility Intention | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | |

| Land titling | 0.014 *** (0.005) | 0.016 *** (0.005) | 0.022 *** (0.007) |

| Age | −0.000 (0.000) | −0.000 (0.000) | |

| Married | 0.005 (0.009) | 0.016 (0.015) | |

| Communist Party membership | 0.009 (0.012) | −0.001 (0.018) | |

| Health | −0.006 ** (0.002) | −0.003 (0.004) | |

| Car | −0.009 (0.007) | −0.021 ** (0.010) | |

| Single-child | −0.023 ** (0.009) | −0.015 (0.015) | |

| Agricultural occupation | 0.006 (0.006) | 0.001 (0.011) | |

| Agricultural land area | 0.001 (0.002) | −0.010 ** (0.005) | |

| Year fixed effect | No | No | Yes |

| Individual fixed effect | No | No | Yes |

| Observations | 8322 | 7168 | 5016 |

| Adjusted R-square | 0.001 | 0.004 | 0.555 |

| Rural Laborer Mobility Intention | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | |

| Land titling | 0.014 *** (0.005) | 0.017 *** (0.005) | 0.022 *** (0.007) |

| Control variable | No | Yes | Yes |

| Year fixed effect | No | No | Yes |

| Individual fixed effect | No | No | Yes |

| Observations | 8279 | 7125 | 4988 |

| Adjusted R-square | 0.001 | 0.004 | 0.556 |

| Rural Laborer Mobility Intention | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | |

| Land titling | 0.003 (0.005) | 0.005 (0.005) | 0.018 * (0.009) |

| Control variable | No | Yes | Yes |

| Year fixed effect | No | No | Yes |

| Individual fixed effect | No | No | Yes |

| Observations | 9942 | 8598 | 6668 |

| Adjusted R-square | 0.000 | 0.014 | 0.618 |

| Rural Laborer Mobility Intention | ||

|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | |

| Land titling | 0.017 *** (0.005) | 0.022 *** (0.008) |

| Gender | −0.009 * (0.005) | −0.008 (0.009) |

| Educational level | 0.001 (0.001) | 0.002 (0.001) |

| Control variable | Yes | Yes |

| Year fixed effect | No | Yes |

| Individual fixed effect | No | Yes |

| Observations | 7160 | 5008 |

| Adjusted R-square | 0.004 | 0.556 |

| Rural Laborer Mobility Intention | |

|---|---|

| (1) | |

| Land titling | 0.022 *** (0.008) |

| Control variable | Yes |

| Year fixed effect | Yes |

| Individual fixed effect | Yes |

| Observations | 4904 |

| Number of districts and counties clustering | 92 |

| Adjusted R-square | 0.555 |

| Rural Laborer Mobility Intention | ||

|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | |

| Land titling | 0.022 *** (0.007) | 0.022 *** (0.008) |

| Control variable | Yes | Yes |

| Year fixed effect | Yes | Yes |

| Individual fixed effect | Yes | Yes |

| City × year fixed effect | Yes | No |

| County × year fixed effect | No | Yes |

| Observations | 4898 | 4896 |

| Adjusted R-square | 0.565 | 0.566 |

| Land Reallocation | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | |

| Land titling | −0.054 *** (0.009) | −0.060 *** (0.009) | −0.137 ** (0.054) |

| Control variable | No | Yes | Yes |

| Year fixed effect | No | No | Yes |

| Individual fixed effect | No | No | Yes |

| Observations | 10,552 | 9321 | 7386 |

| Adjusted R-square | 0.004 | 0.013 | 0.613 |

| Agricultural Machinery Investment | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | |

| Land titling | 0.107 *** (0.007) | 0.091 *** (0.008) | 0.027 * (0.015) |

| Control variable | No | Yes | Yes |

| Year fixed effect | No | No | Yes |

| Individual fixed effect | No | No | Yes |

| Observations | 10,819 | 9370 | 7450 |

| Adjusted R-square | 0.021 | 0.061 | 0.822 |

| Degree of Part-Time Employment in the Village | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Pure Agricultural Villages | Agriculture-Dominant Villages | Non-Agriculture-Dominant Villages | |

| Land titling | 0.033 (0.022) | 0.021 ** (0.009) | 0.018 (0.039) |

| Control variable | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Year fixed effect | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Individual fixed effect | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Observations | 694 | 4252 | 398 |

| Adjusted R-square | 0.599 | 0.554 | 0.494 |

| Intergenerational Differences | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Young Laborers | Middle-Aged Laborers | Elderly Laborers | |

| Land titling | 0.025 (0.033) | 0.021 ** (0.009) | −0.074 ** (0.035) |

| Control variable | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Year fixed effect | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Individual fixed effect | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Observations | 366 | 4252 | 158 |

| Adjusted R-square | 0.503 | 0.554 | 0.714 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mou, S.; Zhu, Z. Land Titling: A Catalyst for Enhancing China Rural Laborers’ Mobility Intentions? Land 2025, 14, 867. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14040867

Mou S, Zhu Z. Land Titling: A Catalyst for Enhancing China Rural Laborers’ Mobility Intentions? Land. 2025; 14(4):867. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14040867

Chicago/Turabian StyleMou, Shanshan, and Zhongkun Zhu. 2025. "Land Titling: A Catalyst for Enhancing China Rural Laborers’ Mobility Intentions?" Land 14, no. 4: 867. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14040867

APA StyleMou, S., & Zhu, Z. (2025). Land Titling: A Catalyst for Enhancing China Rural Laborers’ Mobility Intentions? Land, 14(4), 867. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14040867