Abstract

There is a growing recognition of the contribution that privately-owned land makes to conservation efforts, and governments are increasingly counting privately protected areas (PPAs) towards their international conservation commitments. The public availability of spatial data on countries’ conservation estates is important for broad-scale conservation planning and monitoring and for evaluating progress towards targets. Yet there has been limited consideration of how PPA data is reported to national and international protected area databases, particularly whether such reporting is transparent and fair (i.e., equitable) to the landholders involved. Here we consider PPA reporting procedures from three countries with high numbers of PPAs—Australia, South Africa, and the United States—illustrating the diversity within and between countries regarding what data is reported and the transparency with which it is reported. Noting a potential tension between landholder preferences for privacy and security of their property information and the benefit of sharing this information for broader conservation efforts, we identify the need to consider equity in PPA reporting processes. Unpacking potential considerations and tensions into distributional, procedural, and recognitional dimensions of equity, we propose a series of broad principles to foster transparent and fair reporting. Our approach for navigating the complexity and context-dependency of equity considerations will help strengthen PPA reporting and facilitate the transparent integration of PPAs into broader conservation efforts.

1. Introduction

Protected areas remain a core global strategy for curbing the current biodiversity extinction crisis [1]. Under the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD), signatory governments have committed to conserve at least 17% of their terrestrial and 10% of their marine environments by 2020 through “ecologically representative” protected area networks (Aichi Target 11) [2]. Despite significant expansion in the global protected area estate in the past two decades, many countries are predicted to fall short of this target, particularly in terms of ecological representation [3,4]. The majority of the world’s reported protected areas are owned and managed by governments [1], with their efficacy and extent constrained in many cases by limited governmental resources and competing priorities [5]. The capacity of these protected areas to protect representative samples of biodiversity is further limited by often historical biases in their locations towards higher elevations, steeper slopes, and less productive portions of the landscape [4,6]. In many countries, the majority of land is privately owned, particularly in highly productive areas, and some of these contain threatened and/or under-represented ecosystems [7,8,9,10]. Increasingly, privately protected areas (PPAs) are being used to conserve biodiversity on private land, complementing government-owned protected area estates [8,11,12,13,14]. The increase in the number of, and area covered by, PPAs around the world in recent decades [15,16] poses unique opportunities and challenges for monitoring, managing, and expanding the protected area estate.

The potential for PPAs to contribute to conservation has been emphasized by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) World Commission on Protected Areas (IUCN-WCPA) [17], and in some countries, PPAs are counted towards international conservation targets (e.g., Aichi Target 11 [15]). PPA information (e.g., geospatial data, property name, management authority) is included within some national and international protected area databases, such as the World Database on Protected Areas (WDPA) [16]. These databases provide information on the distribution of a country’s complete protected area estate, which is important for systematic conservation planning, monitoring, and evaluation [18,19] and enables transparent assessments of progress towards international conservation targets (e.g., [20]). While the inclusion of PPAs in national and international databases is beneficial from a conservation perspective, the public accessibility of many of these databases raises questions about whether current approaches of including PPA information are fair and transparent to the PPA owners.

Defined as protected areas under private governance [15], PPAs encompass a diverse set of private property conservation arrangements (e.g., conservation easements, conservation covenants, and land stewardship agreements). In many countries, PPAs are commonly owned by individuals or families (hereafter referred to as “landholders”), and in some instances these landholders live on and/or derive a primary income from their land [15]. These individual or family PPA landholders (as opposed to non-government organizations, NGOs, who own PPAs) are the focus of this paper. The capacity and motivation of these landholders for managing their PPAs can vary [21], as can their awareness of the obligations of owning protected land [22]. Whilst some PPAs are established and managed with public funding (e.g., incentives programs), others rely on private funding or independent action by landholders [23]. This diversity in landholder motivations, management approaches, and residential or financial dependence on PPAs suggests there may be potential differences in landholder preferences regarding the sharing of PPA information. Thus, the inclusion of PPA information in conservation databases warrants considerations beyond those required for protected areas on public land.

However, there has been limited consideration of PPA data reporting processes, and it remains unclear what PPA information is collated, who has access to this information, whether landholders are aware of reporting procedures, and how their perspectives are accounted for [24,25,26]. Examining these questions is timely given the current development of PPA best-practice guidelines by the IUCN (referred to in [16]) and the 2020 deadline for achieving the CBD Aichi Targets. The 2016 IUCN World Conservation Congress approved a resolution on supporting PPAs, which calls on IUCN members to “include privately protected areas that meet the requirements of IUCN Protected Area Standards when reporting about protected area coverage and other related information, including to the World Database on Protected Areas (WDPA) and to the CBD, in collaboration and agreement with the owners of such areas” (emphasis added) [17] (p. 2). A discussion on PPA data reporting is also timely given the General Data Protection Regulation that became enforceable in the European Union earlier this year (a region in which PPA numbers are increasing [14,27,28]).

Acknowledging the benefits of compiling PPA databases, we explore in this paper current international and several national procedures for reporting PPA data and the extent to which landholders are informed of these procedures. We focus on the three countries with the highest numbers of reported PPAs in the WDPA: Australia, South Africa, and the United States of America (USA) [16]. Given the apparent need for transparency and fairness in PPA reporting, particularly for PPAs owned by individuals (as opposed to NGOs), we apply an equity framework to identify the potential tensions and implications of including PPA data in publicly accessible databases. This broad framework leaves room for the diversity of contexts in which PPAs are administered. As such, our aim is to prompt reflection against equity principles in a manner that acknowledges this context diversity rather than offer a rigid tool for universal application. Finally, we synthesize the insights into a series of principles to help policy makers navigate potential issues and promote equitable reporting of PPA data. We emphasize the importance of navigating these issues to ensure effective integration of PPAs into conservation planning, management, and monitoring where agreed by the owners of such areas.

2. Current International and National PPA Data Management Procedures

Debate around providing access to personal or sensitive data spans many domains, including big data, e-health, and law enforcement (e.g., [29,30]). One prominent example within conservation is whether to publish the location of threatened species. Some researchers argue that location data should be kept confidential given the risks of poaching [31], while others promote open-access to enable effective conservation planning and management [32,33]. In the case of PPAs, the value of comprehensive protected area databases for conservation planning and management may come with risks to the landholders who make available their property information. For example, concerns have been raised by conservation organizations and landholders that publishing the location of a PPA may encourage trespassing or be used by property developers to identify undervalued land [24,26]. The need for the data owner’s consent to share their information is also a common feature in international data-sharing policies [34]. It is thus important to explore whether and how current international and national protected area reporting processes navigate these considerations.

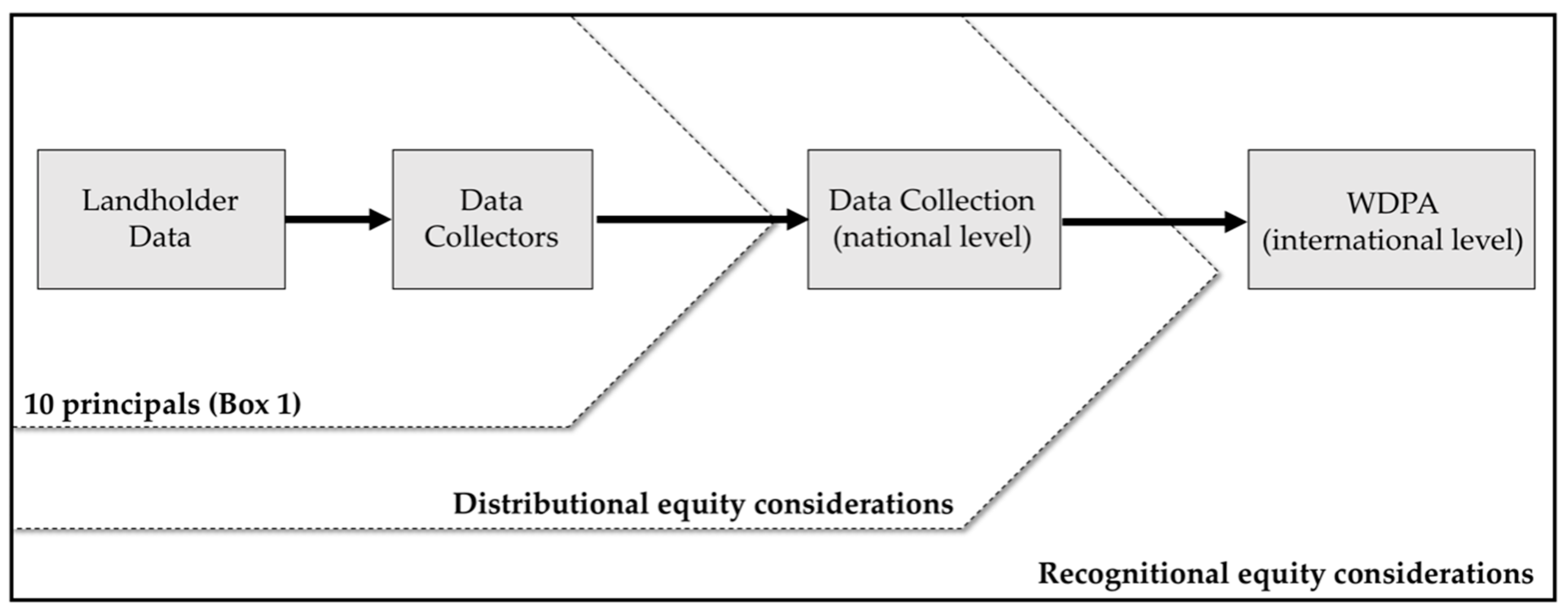

The importance of international collaboration between state and private actors for successful conservation initiatives, including protected areas, is increasingly discussed [35,36,37]. In reporting protected area data, this collaboration typically takes the form of national governments collating protected area (including in some instances PPA) information from a variety of sources (e.g., national and subnational government agencies, NGOs) and reporting this information to the United Nations Environmental Program-World Conservation Monitoring Centre, which curates the WDPA [38] (Figure 1). NGOs can also submit protected area data directly to the WDPA subsequent to data verification by the WCPA [16]. Unless otherwise specified, this data is made freely available online where it is used for a variety of purposes, including conservation research, the development of conservation indicators and targets (e.g., Sustainable Development Goals Indicator 15.1.2 and Aichi Target 11), and reporting on conservation progress (e.g., Protected Planet Report) [38]. The WDPA also accepts data with restrictions on use and dissemination. If PPA data is considered sensitive by the data provider, it can be used by WDPA managers for analyses but not shared further [16]. The WDPA requires, at a minimum, the protected area name, management authority, and geographic location [38]. Ideally, management plans and geospatial data of protected area boundaries are also provided. Data is only accepted into the WDPA after the provider has signed a contributor agreement, stipulating whether the data can be shared publicly and verifying that the “relevant stakeholders and rights-holders” have agreed to the provision of the data [38] (p. 60). However, for PPA data provided to the WDPA, there is limited information regarding the extent to which relevant landholders are aware of, and agree with, the inclusion of their data [16]. There is therefore a need to examine how PPA data is collected, managed, and reported within countries (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Conceptual flow of privately protected area (PPA) data from local (landholder) to international (World Database on Protected Areas; WDPA) reporting levels. Recognitional equity considerations are important at all levels, while distributional and procedural equity considerations are most applicable to the PPA data collection and collation decisions, rules, and responsibilities established within a country (Table 1). The ten principles described in Box 1 are intended to guide equitable data collection by the local, state, or regional organizations that oversee the PPA agreements.

In their recent review of 17 countries, Stolton et al. (2014) [15] found that 12 countries had national databases of their PPA estates, though the majority were incomplete. Here we illustrate the diversity in PPA reporting using three examples: Australia, South Africa, and the USA. These three countries currently report the greatest number of PPAs to the WDPA (together accounting for 87% of all PPAs in the WDPA in 2017 [16]), and therefore represent good examples for considering reporting procedures across three diverse continents. These are not intended to be in-depth case studies but are rather illustrations of current PPA reporting issues.

In Australia, conservation covenants and private reserves owned by NGOs are the key mechanisms for establishing PPAs [25,39]. Conservation covenants are binding agreements between landholders and an authorized agency (e.g., state-level government, NGOs), established to protect natural features in perpetuity, sometimes incentivized through the provision of financial support or management guidance [25]. The PPA estate in Australia has seen impressive expansion in recent years, increasing the biodiversity representation and connectivity of the National Reserve System [19,25]. While Australia has a publicly available national protected area database that has shown good progress in its inclusion of PPAs (Collaborative Australian Protected Area Database; CAPAD), covenants are designated under state legislation and only some states and agencies provide data to the national database [25]. Factors impeding covenant reporting include privacy concerns about revealing property locations and a lack of coordination among stakeholders (e.g., state governments versus the Australian government) [25,40]. While many interviewed landholders viewed inclusion of their covenanted land in the national database positively, others had a negative perspective towards inclusion due to concerns that their contribution may lessen the government’s responsibility for meeting national protected area targets on publicly-owned land (i.e., additionality does not take place through state protected area expansion because governments count PPAs that were being conserved anyway towards their targets) [41]. For some PPAs, there is transparency that landholders’ property information will be included in national databases upon signing agreements (e.g., new PPAs purchased by NGOs with funds from the Australian Government’s National Reserve System Program and new covenants signed under the Tasmanian Private Forest Reserve Program in exchange for financial incentives) [25]. For other conservation covenants that are currently reported nationally, it is unclear whether landholders are made aware that information about their properties may be included as PPAs in national and international databases. We are aware that some programs have not sought explicit permission to include this data in the CAPAD.

In South Africa, the Department of Environmental Affairs has a legislative mandate to maintain a publicly available register of South Africa’s conservation estate [42] and an advanced legislative system for formally recognizing PPAs, which have become the focus of protected area expansion efforts [43]. South Africa’s primary tool for expanding its estate of protected areas on privately owned land is the national biodiversity stewardship initiative [44]. Biodiversity Stewardship Agreements are established through a contract between the landholder and the provincial conservation agency, and data-reporting policies are not evident in the national contract template [45]. However, the establishment of a formal PPA requires a public gazettal process [45], suggesting landholders are likely to be aware of the public availability of their property’s name, land use, and geospatial data.

The establishment of most private conservation areas in the USA is negotiated by organizations that either purchase land directly or specialize in conservation easements (agreements between landholders and organizations regarding land use restrictions to achieve conservation in exchange for payment, tax benefits, or development permits [23]). The publicly accessible National Conservation Easement Database has successfully aggregated data on easements held by thousands of conservation organizations (NGOs, state and federal governments), but many organizations have declined to provide data [26]. Concern for landholder privacy is reported as a primary deterrent for those not reporting as well as prior agreements with landholders not to share locations and fear that this data could be used by developers to identify undervalued properties [24,26]. Although the USA does not formally recognize a unified national protected area system and has no PPA definition, an impressive 8731 USA PPAs are reported in the WDPA—the most of any country [46].

These examples highlight some of the diversity both within and between countries in the extent of, processes associated with, and transparency regarding the reporting of PPA data. This diversity reflects complex governance and legislative arrangements involving landholders, NGOs, and governmental agencies that operate at local through to national scales. Based on the examples above, it is not always clear whether affected landholders are made aware of data management policies and whether they are provided the opportunity to state their preference regarding being labeled as a PPA and included in national and international databases and towards conservation targets. While some landholders viewed inclusion in national protected area systems positively [41], several studies have noted landholder concerns regarding the public sharing of their information ranging from privacy risks to a reluctance to negate governments of their conservation responsibilities [26,41]. The lack of reporting transparency and landholder concerns around PPA data sharing are not specific to the three focal countries. During the compilation of a PPA database for Mexico, for example, concerns were raised by some landholders that the misuse of their PPA information by others could lead to instances of blackmail [16,47]. When these concerns are weighed against the importance of sharing this information for broader societal benefits, such as effective conservation planning, potential tensions emerge between private and public good [24]. These tensions need to be navigated fairly and transparently.

3. Issues of Equity around PPA Data Inclusion in Publicly Accessible Databases

Questions of fairness and transparency in PPA reporting suggest the need to engage with the concept of equity, which is broadly defined as the fair and just treatment of individuals or groups within society [48]. The consideration of equity in conservation can be regarded as both fundamental (i.e., it is inherently right) and outcome-based (i.e., it can assist in achieving effective long-term conservation) [49]. For example, perceptions of unfairness amongst communities affected by conservation policies can lead to increased costs for conservation programs [50]. There is increasing recognition that conservation policy has often neglected issues of equity regarding people affected by policy prescriptions [51]. Equity brings a focus to questions of legitimate process, participant buy-in, increased accountability, and transparent compliance for conservation [50,51].

The importance of equitable processes in the establishment and management of protected areas is emphasized by the CBD under Aichi Target 11, which states that indigenous and local communities “should equitably share in the benefits arising from protected areas and should not bear inequitable costs” [2]. Here we highlight the relevance of equity issues beyond protected area establishment and management to protected area data reporting when private landholders are involved. This is particularly relevant considering that a new post-2020 global Strategic Plan for Biodiversity will be negotiated over the coming years and new targets will be set that will require equity considerations. Following from recent work on equity in conservation contexts [48,49,50], we use three dimensions of equity—procedural, distributional, and recognitional—to unpack potential fairness considerations and tensions associated with including PPAs in publicly accessible databases. We frame these considerations as a series of questions to facilitate reflection on reporting processes for different organizations (Table 1). We include questions that are (1) most relevant to the organizations that engage with landholders, facilitate PPA agreements, and collect PPA information, and (2) also relevant to organizations that collate this information at a national level (see Figure 1). The questions listed are not intended to be prescriptive, nor do we assume they are all-encompassing given the likely range of equity issues in different PPA contexts. The questions offer prompts for considering how organizations can respond to the issues raised in a manner that is applicable to their context and governance arrangements.

Table 1.

Considerations of three dimensions of equity [48,49,50] in the inclusion of privately protected area (PPA) data (e.g., geospatial data, property name, management authority) in publicly available databases and towards national and international conservation targets. These considerations are relevant to the organizations that engage directly with landholders, facilitate PPA agreements, and collect PPA data (‘data collectors’; Figure 1). Some considerations are also relevant to the national organizations that collate this information and decide whether to contribute it to international databases.

Procedural equity refers to the equitable involvement and inclusion of all stakeholder groups in rule-making and decisions [48]. Questions of procedural equity for PPA data reporting relate to how decisions are made regarding whether to include PPAs in publicly accessible databases and towards international targets and the extent to which different landholders can participate in these decisions (Table 1). Distributional equity refers to the equitable distribution of costs, benefits, rights, responsibilities, and risk within and among groups from present and future generations [48] and is thus associated with how the benefits and costs for public and private stakeholders involved in PPA reporting processes are distributed (Table 1). Finally, recognitional equity relates to the equitable respect for knowledge systems, values, social norms, and rights of all stakeholders and consideration of the diversity of institutional and political settings [48], calling for consideration of the diversity of PPA landholders and the environments in which PPAs operate (Table 1). Questions of distributional, procedural, and recognitional equity are likely to be important for guiding decisions, rules, and responsibilities established by organizations collecting, managing, and sharing PPA data within a country (Figure 1). In addition, the relevance of recognitional equity considerations may extend to the international organizations aggregating and sharing this data (Figure 1).

5. Conclusions

Considerations of equity are gaining increasing attention in conservation, including protected area establishment and management [58]. Here we have illustrated that such considerations need to extend to protected area data reporting processes when private landholders are involved. It is important to consider procedural, distributional, and recognitional dimensions of equity, including questions of landholder consent regarding data-sharing, the distribution of costs and benefits of data-sharing between private individuals and the public good, and recognition of diverse landholder motivations and tenure arrangements (Table 1). We have offered a set of ten broad principles to help organizations navigate the complexity and context-dependency of equity considerations for PPA data reporting (Box 1). With the growing number and extent of PPAs around the world, there is increasing recognition that conservation planning, management, monitoring, and evaluation would greatly benefit from the inclusion of these privately-owned properties. Wherever the reporting of PPA data is required, and deemed appropriate, we stress the importance of providing fair and transparent reporting processes. This will facilitate effective and integrated conservation efforts and rigorous assessments of progress at national and international levels.

Author Contributions

All authors contributed to the following: Conceptualization, Writing—Original Draft Preparation, and Writing—Review & Editing.

Funding

This research was funded by a Claude Leon Fellowship (HC); Australian Postgraduate Awards (CA, JG); the Australian Research Council Centre of Excellence for Environmental Decisions grant number CE11001000104, funded by the Australian Government (CA, MH, MS); and The Nature Conservancy (JF).

Acknowledgments

We thank Brent Mitchell and two anonymous reviewers for valuable feedback on an earlier version of this paper.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- UNEP-WCMC; IUCN. Protected Planet Report 2016; UNEP-WCMC: Cambridge, UK; Gland, Switzerland, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- CBD. Convention on Biological Diversity’s Strategic Plan for 2020; CBD: Montreal, QC, Canada, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Butchart, S.H.M.; Clarke, M.; Smith, R.J.; Sykes, R.E.; Scharlemann, J.P.W.; Harfoot, M.; Buchanan, G.M.; Angulo, A.; Balmford, A.; Bertzky, B.; et al. Shortfalls and solutions for meeting national and global conservation area targets. Conserv. Lett. 2015, 8, 329–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venter, O.; Magrach, A.; Outram, N.; Klein, C.J.; Marco, M.D.; Watson, J.E.M. Bias in protected-area location and its effects on long-term aspirations of biodiversity conventions. Conserv. Biol. 2018, 32, 127–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watson, J.E.M.; Dudley, N.; Segan, D.B.; Hockings, M. The performance and potential of protected areas. Nature 2014, 515, 67–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joppa, L.N.; Pfaff, A. High and far: Biases in the location of protected areas. PLoS ONE 2009, 4, e8273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Norton, D.A. Conservation biology and private land: Shifting the focus. Conserv. Biol. 2000, 14, 1221–1223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallo, J.A.; Pasquini, L.; Reyers, B.; Cowling, R.M. The role of private conservation areas in biodiversity representation and target achievement within the Little Karoo region, South Africa. Biol. Conserv. 2009, 142, 446–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitzsimons, J.; Wescott, G. The role and contribution of private land in Victoria to biodiversity conservation and the protected area system. Aust. J. Environ. Manag. 2001, 8, 142–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knight, A.T. Private lands: The neglected geography. Conserv. Biol. 1999, 13, 223–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanee, S.; Shanee, N.; Monteferri, B.; Allgas, N.; Pardo, A.A.; Horwich, R.H. Protected area coverage of threatened vertebrates and ecoregions in Peru: Comparison of communal, private and state reserves. J. Environ. Manag. 2017, 202, 12–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pegas, F.D.V.; Castley, J.G. Private reserves in Brazil: Distribution patterns, logistical challenges, and conservation contributions. J. Nat. Conserv. 2016, 29, 14–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Von Hase, A.; Rouget, M.; Cowling, R.M. Evaluating private land conservation in the Cape lowlands, South Africa. Conserv. Biol. 2010, 24, 1182–1189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manolache, S.; Nita, A.; Ciocanea, C.M.; Popescu, V.D.; Rozylowicz, L. Power, influence and structure in Natura 2000 governance networks. A comparative analysis of two protected areas in Romania. J. Environ. Manag. 2018, 212, 54–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stolton, S.; Redford, K.H.; Dudley, N. The Futures of Privately Protected Areas; IUCN: Gland, Switzerland, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Bingham, H.; Fitzsimons, J.A.; Redford, K.H.; Mitchell, B.A.; Bezaury-Creel, J.; Cumming, T.L. Privately protected areas: Advances and challenges in guidance, policy and documentation. Parks 2017, 23.1, 13–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IUCN. WCC-2016-Res-036-EN Supporting Privately Protected Areas; IUCN: Gland, Switzerland, 2016; Available online: https://portals.iucn.org/library/node/46453 (accessed on 12 August 2018).

- Margules, C.R.; Pressey, R.L. Systematic conservation planning. Nature 2000, 405, 243–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fitzsimons, J.A.; Wescott, G. The role of multi-tenure reserve networks in improving reserve design and connectivity. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2008, 85, 163–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tittensor, D.P.; Walpole, M.; Hill, S.L.L.; Boyce, D.G.; Britten, G.L.; Burgess, N.D.; Butchart, S.H.M.; Leadley, P.W.; Regan, E.C.; Alkemade, R.; et al. A mid-term analysis of progress toward international biodiversity targets. Science 2014, 346, 241–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fitzsimons, J.A.; Carr, C.B. Conservation covenants on private land: Issues with measuring and achieving biodiversity outcomes in Australia. Environ. Manag. 2014, 54, 606–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stroman, D.A.; Kreuter, U.P. Perpetual conservation easements and landowners: Evaluating easement knowledge, satisfaction and partner organization relationships. J. Environ. Manag. 2014, 146, 284–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamal, S.; Brown, G. Conservation on private land: A review of global strategies with a proposed classification system. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 2015, 58, 576–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olmsted, J.L. The invisible forest: Conservation easement databases and the end of clandestine conservation of natural lands. Law Contemp. Probl. 2011, 74, 51–82. [Google Scholar]

- Fitzsimons, J.A. Private protected areas in Australia: Current status and future directions. Nat. Conserv. 2015, 10, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rissman, A.R.; Owley, J.; L’Roe, A.W.; Morris, A.W.; Wardropper, C.B. Public access to spatial data on private-land conservation. Ecol. Soc. 2017, 22, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rafa, M. Spain. In The Futures of Privately Protected Areas; Stolton, S., Redford, K.H., Dudley, N., Eds.; IUCN: Gland, Switzerland, 2014; pp. 92–94. [Google Scholar]

- Heinonen, M. Finland. In The Futures of Private Protected Areas; Stolton, S., Redford, K.H., Dudley, N., Eds.; IUCN: Gland, Switzerland, 2014; pp. 70–74. [Google Scholar]

- Goldenfein, J. Police photography and privacy: Identity, stigma and reasonable expectation. UNSW Law J. 2013, 36, 256. [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman, S. Citizen science: The law and ethics of public access to medical big data. Berkeley Technol. Law J. 2015, 30, 1741–1806. [Google Scholar]

- Lindenmayer, D.B.; Scheele, B. Do not publish. Science 2017, 356, 800–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lowe, A.J.; Smyth, A.K.; Atkins, K.; Avery, R.; Belbin, L.; Brown, N.; Budden, A.E.; Guru, S.; Hardie, M.; Smits, J.; et al. Publish openly but responsibly. Science 2017, 357, 141–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tulloch, A.I.T.; Auerbach, N.; Avery-Gomm, S.; Bayraktarov, E.; Butt, N.; Dickman, C.R.; Ehmke, G.; Fisher, D.O.; Grantham, H.; Holden, M.H.; et al. A decision tree for assessing the risks and benefits of publishing biodiversity data. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 2018, 2, 1209–1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greenleaf, G. The influence of European data privacy standards outside Europe: Implications for globalization of Convention 108. Int. Data Priv. Law 2012, 2, 68–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemos, M.C.; Agrawal, A. Environmental governance. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2006, 31, 297–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nita, A.; Ciocanea, C.M.; Manolache, S.; Rozylowicz, L. A network approach for understanding opportunities and barriers to effective public participation in the management of protected areas. Soc. Netw. Anal. Min. 2018, 8, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodin, Ö. Collaborative environmental governance: Achieving collective action in social-ecological systems. Science 2017, 357, eaan1114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- UNEP-WCMC. World Database on Protected Areas User Manual 1.5; UNEP-WCMC: Cambridge, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Fitzsimons, J.A. Private Protected Areas? Assessing the suitability for incorporating conservation agreements over private land into the National Reserve System: A case study of Victoria. Environ. Plan. Law J. 2006, 23, 365–385. [Google Scholar]

- Hardy, M.J.; Fitzsimons, J.A.; Bekessy, S.A.; Gordon, A. Exploring the permanence of conservation covenants. Conserv. Lett. 2017, 10, 221–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitzsimons, J.A.; Wescott, G. Perceptions and attitudes of land managers in multi-tenure reserve networks and the implications for conservation. J. Environ. Manag. 2007, 84, 38–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fourie, N. The South African database on Protected and Conserved areas (SAPAD)—Realising the objectives of the SDI Act and custodianship. In Geomatics Indaba Proceedings 2015—Stream 2; EE Publishers: Muldersdrift, South Africa, 2015; pp. 88–99. [Google Scholar]

- DEA; SANBI. National Protected Area Expansion Strategy for South Africa; DEA: Springfield, VA, USA, 2009.

- Mitchell, B.A.; Fitzsimons, J.A.; Stevens, C.M.D.; Wright, D.R. PPA or OECM? Differentiating between privately protected areas and other effective area-based conservation measures on private land. Parks 2018, 24, (SpecialIssue). 49–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DEA. Biodiversity Stewardship Guidelines; Department of Environmental Affairs: Pretoria, South Africa, 2009.

- IUCN & UNEP-WCMC. The World Database on Protected Areas (WDPA), September 2017; IUCN: Cambridge, UK, 2017; Available online: https://www.iucn.org/theme/protected-areas/our-work/world-database-protected-areas (accessed on 12 August 2018).

- Bezaury-Creel, J.E.; Ochoa-Ochoa, L.M.; Torres-Origel, J.F. Base de Datos Geográfica de las Reservas de Conservación Privadas y Comunitarias en México—Versión 2.1 Diciembre 31, 2012; The Nature Conservancy: Mexico City, Mexico, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- McDermott, M.; Mahanty, S.; Schreckenberg, K. Examining equity: A multidimensional framework for assessing equity in payments for ecosystem services. Environ. Sci. Policy 2013, 33, 416–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Law, E.A.; Bennett, N.J.; Ives, C.D.; Friedman, R.; Davis, K.J.; Archibald, C.; Wilson, K.A. Equity trade-offs in conservation decision making. Conserv. Biol. 2018, 32, 294–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pascual, U.; Phelps, J.; Garmendia, E.; Brown, K.; Corbera, E.; Martin, A.; Gomez-Baggethun, E.; Muradian, R. Social equity matters in payments for ecosystem services. BioScience 2014, 64, 1027–1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawson, N.; Martin, A.; Danielsen, F. Assessing equity in protected area governance: Approaches to promote just and effective conservation. Conserv. Lett. 2018, 11, e12388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torabi, N.; Mata, L.; Gordon, A.; Garrard, G.; Wescott, W.; Dettmann, P.; Bekessy, S.A. The money or the trees: What drives landholders’ participation in biodiverse carbon plantings? Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 2016, 7, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selinske, M.J.; Cooke, B.; Torabi, N.; Hardy, M.J.; Knight, A.T.; Bekessy, S.A. Locating financial incentives among diverse motivations for long-term private land conservation. Ecol. Soc. 2017, 22, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooke, B.; Moon, K. Aligning “public good” environmental stewardship with the landscape-scale: Adapting MBIs for private land conservation policy. Ecol. Econ. 2015, 114, 152–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooke, B.; Langford, W.T.; Gordon, A.; Bekessy, S. Social context and the role of collaborative policy making for private land conservation. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 2012, 55, 469–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selinske, M.J.; Coetzee, J.; Purnell, K.; Knight, A.T. Understanding the motivations, satisfaction, and retention of landowners in private land conservation programs. Conserv. Lett. 2015, 8, 282–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ICCA. Indigenous and Community Conserved Areas Registry. Available online: http://www.iccaregistry.org/ (accessed on 7 July 2018).

- Franks, P.; Booker, F.; Roe, D. Understanding and Assessing Equity in Protected Area Conservation; IEED Issue Paper; IEED: London, UK, 2018; ISBN 9781784315559. [Google Scholar]

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).