Prevalence and Characteristic of Oral Mucosa Lesions

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

6. Keypoints

- Clinicians should be familiar not only with distinctive features of OMLs, which sometimes may not be clear, but also with its population prevalence and with its frequency in connection to age and gender.

- In our study, oral lichen planus was the most frequent diagnosis.

- In our study, women were more frequently affected by different types of OMLs, apart from mucocele, hairy tongue, papilloma and hemangioma, which affected men more often.

- In our research, the age median was the highest in patients with xerostomia, burning mouth syndrome, angular cheilitis and oral candidiasis.

- The youngest median age was observed in patients with aphthae, mucocele and gingival enlargement.

- According to the types and lesions pattern, oral mucosa pathologies are observed in different sites of oral cavity, both in single or multiple localizations and both symmetrically and non-symmetrically.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mehrotra, V.; Devi, P.; Bhovi, T.V.; Jyoti, B.; Pradesh, U. Mouth as a Mirror of Systemic Diseases. Gomal J. Med. Sci. 2010, 8, 235–241. [Google Scholar]

- Suliman, N.M.; Johannessen, A.C.; Ali, R.W.; Salman, H.; Åstrøm, A.N. Influence of oral mucosal lesions and oral symptoms on oral health related quality of life in dermatological patients: A cross sectional study in Sudan. BMC Oral Health 2012, 12, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Silverman, S. Mucosal Lesions in Older Adults. J. Am. Dent. Assoc. 2007, 138, S41–S46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El-Hamd, M.; Aboeldahab, S. Clinicoepidemiological analysis of patients with oral mucosal lesions attending dermatology clinics. Egypt. J. Dermatol. Venerol. 2018, 38, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamath, V.; Setlur, K.; Yerlagudda, K. Oral lichenoid lesions-A review and update. Indian J. Dermatol. 2015, 60, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Splieth, C.; Sümning, W.; Bessel, F.; John, U.; Kocher, T. Prevalence of oral mucosal lesions in a representative population. Quintessence Int. 2007, 38, 23–29. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Patil, P.; Bathi, R.; Chaudhari, S. Prevalence of oral mucosal lesions in dental patients with tobacco smoking, chewing, and mixed habits: A cross-sectional study in South India. J. Fam. Community Med. 2013, 20, 130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Saraswathi, T.; Ranganathan, K.; Shanmugam, S.; Sowmya, R.; Narasimhan, P.; Gunaseelan, R. Prevalence of oral lesions in relation to habits: Cross-sectional study in South India. Indian J. Dent. Res. 2006, 17, 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, T.; Yap, T.; Wiesenfeld, D. Common causes of ‘swelling’ in the oral cavity. Aust. J. Gen. Pract. 2020, 49, 575–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daley, T.D.; Armstrong, J.E. Oral Manifestations of Gastrointestinal Diseases. Can. J. Gastroenterol. 2007, 21, 241–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ariyawardana, A. Traumatic Oral Mucosal Lesions: A Mini Review and Clinical Update. Trauma. Oral Mucosal Lesions A Mini Rev. Clin. Updat. 2014, 13, 254–259. [Google Scholar]

- Hermann, P.; Beck, A.; Fábián, G.; Fejérdy, P.; Fábián, T.K. Salivary defense proteins: Their network and role in innate and acquired oral immunity. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2012, 13, 4295–4320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavičić, D.K.; Braut, A.; Pezelj-Ribarić, S.; Glažar, I.; Lajnert, V.; Mišković, I.; Muhvić-Urek, M. Predictors of oral mucosal lesions among removable prosthesis wearers. Period. Biol. 2017, 119, 181–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocha Gusmão, J.M.; Ferreira Dos Santos, S.S.; Piero Neisser, M.; Cardoso Jorge, A.O.; Ivan Faria, M. Correlation between factors associated with the removable partial dentures use and Candida spp. in saliva. Gerodontology 2011, 28, 283–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tadin, A.; Gavic, L.; Zeravica, A.; Ugrin, K.; Galic, N.; Zeljezic, D. Assessment of cytotoxic and genotoxic effects of conventional and whitening kinds of toothpaste on oral mucosa cells. Acta Odontol. Scand. 2018, 76, 64–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arunkumar, S.; Kalappanavar, A.N.; Annigeri, R.G.; Shakunthala, G.K. Adverse Oral Manifestations of Cardiovascular Drugs. IOSR J. Dent. Med. Sci. 2013, 7, 64–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinna, R.; Cocco, F.; Campus, G.; Conti, G.; Milia, E.; Sardella, A.; Cagetti, M.G. Genetic and developmental disorders of the oral mucosa: Epidemiology; molecular mechanisms; diagnostic criteria; management. Periodontology 2000 2019, 80, 12–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlosser, B.J.; Pirigyi, M.; Mirowski, G.W. Oral Manifestations of Hematologic and Nutritional Diseases. Otolaryngol. Clin. N. Am. 2011, 44, 183–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Wayli, H.; Khalid Rashed, B.A.W.; Kumar, A.; Rastogi, S. The Prevalence of Oral Mucosal Lesions among Saudi Females Visiting a Tertiary Dental Health Center in Riyadh Region, Saudi Arabia. J. Int. Oral Heal. 2016, 8, 675–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohan, R.P.S.; Verma, S.; Singh, U.; Agarwal, N. Acute primary herpetic gingivostomatitis. Case Rep. 2013, 2013, bcr2013200074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mravak-Stipetić, M.; Sabol, I.; Kranjčić, J.; Knežević, M.; Grce, M. Human Papillomavirus in the Lesions of the Oral Mucosa According to Topography. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e69736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- D’Souza, G.; Agrawal, Y.; Halpern, J.; Bodison, S.; Gillison, M.L. Oral sexual behaviors associated with prevalent oral human papillomavirus infection. J. Infect. Dis. 2009, 199, 1263–1269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Kusiak, A.; Jereczek-Fossa, B.A.; Cichońska, D.; Alterio, D. Oncological-Therapy Related Oral Mucositis as an Interdisciplinary Problem—Literature Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 2464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Hong, C.H.L.; Dean, D.R.; Hull, K.; Hu, S.J.; Sim, Y.F.; Nadeau, C.; Gonçalves, S.; Lodi, G.; Hodgson, T.A. World Workshop on Oral Medicine VII: Relative frequency of oral mucosal lesions in children, a scoping review. Oral Dis. 2019, 25, 193–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrozzo, M.; Porter, S.; Mercadante, V.; Fedele, S. Oral Lichen Planus: A Disease or a Spectrum of Tissue Reactions? Types, Causes, Diagnostic Algorhythms, Prognosis, Management Strategies. Periodontology 2000, 80, 105–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karagöz, G.; Bektaş Kayhan, K.; Ünür, M. Desquamative Gingivitis: A Review. J. Istanb. Univ. Fac. Dent. 2016, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alshayeb, M.; Mathew, A.; Varma, S.; Elkaseh, A.; Kuduruthullah, S.; Ashekhi, A.; Habbal, A.W.A.L. Prevalence and distribution of oral mucosal lesions associated with tobacco use in patients visiting a dental school in Ajman. Onkol. I Radioter. 2019, 46, 29–33. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, S.; Suhag, A.; Narwal, A.; Kolay, S.; Konidena, A.; Sachdev, A. Oral mucosal disorder-A demographic study. J. Fam. Med. Prim. Care 2020, 9, 755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pratik, P.; Desai, V. Prevalence of habits and oral mucosal lesions in Jaipur, Rajasthan. Indian J. Dent. Res. 2015, 26, 196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.C.; Corbet, E.F.; Lo, E.C.M. Oral Mucosal Lesions in Adult Chinese. J. Dent. Res. 2001, 80, 1486–1490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- van der Waal, I. Diseases of the oral mucosa in the aged patient. Int. Dent. J. 1983, 33, 319–324. Available online: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/6581127 (accessed on 27 November 2021). [PubMed]

- Al-Mobeeriek, A.; AlDosari, A.M. Prevalence of oral lesions among Saudi dental patients. Ann. Saudi Med. 2009, 29, 365–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kansky, A.A.; Didanovic, V.; Dovsak, T.; Brzak, B.L.; Pelivan, I.; Terlevic, D. Epidemiology of oral mucosal lesions in Slovenia. Radiol. Oncol. 2018, 52, 263–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Kumar, S.; Narayanan, V.S.; Ananda, S.R.; Kavitha, A.P.; Krupashankar, R. Prevalence and risk indicators of oral mucosal lesions in adult population visiting primary health centers and community health centers in Kodagu district. J. Fam. Med. Prim. Care 2019, 8, 2337–2342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sholapurkar, A.; Vengal, M.; Mathew, A.; Pai, K. The prevalence of oral mucosal lesions in patients visiting a dental school in Southern India. Indian J. Dent. Res. 2008, 19, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatnagar, P.; Rai, S.; Bhatnagar, G.; Kaur, M.; Goel, S.; Prabhat, M. Prevalence study of oral mucosal lesions, mucosal variants, and treatment required for patients reporting to a dental school in North India: In accordance with WHO guidelines. J. Fam. Community Med. 2013, 20, 41–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cortés-Ramírez, D.A.; Rodríguez-Tojo, M.J.; Gainza-Cirauqui, M.L.; Martínez-Conde, R.; Aguirre-Urizar, J.M. Overexpression of cyclooxygenase-2 as a biomarker in different subtypes of the oral lichenoid disease. Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. Oral Radiol. Endodontology 2010, 110, 738–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovač-Kavčič, M.; Skalerič, U. The prevalence of oral mucosal lesions in a population in Ljubljana, Slovenia. J. Oral Pathol. Med. 2000, 29, 331–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tortorici, S.; Corrao, S.; Natoli, G.; Difalco, P. Prevalence and distribution of oral mucosal non-malignant lesions in the western Sicilian population. Minerva Stomatol. 2016, 65, 191–206. Available online: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27374359 (accessed on 27 November 2021).

- Oivio, U.M.; Pesonen, P.; Ylipalosaari, M.; Kullaa, A.; Salo, T. Prevalence of oral mucosal normal variations and lesions in a middle-aged population: A Northern Finland Birth Cohort 1966 study. BMC Oral Health 2020, 20, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Toum, S.; Cassia, A.; Bouchi, N.; Kassab, I. Prevalence and Distribution of Oral Mucosal Lesions by Sex and Age Categories: A Retrospective Study of Patients Attending Lebanese School of Dentistry. Int. J. Dent. 2018, 2018, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Babu, B.; Hallikeri, K. Reactive lesions of oral cavity: A retrospective study of 659 cases. J. Indian Soc. Periodontol. 2017, 21, 258–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar Srivastava, V. To Study the Prevalence of Premalignancies in Teenagers having Betel, Gutkha, Khaini, Tobacco Chewing, Beedi and Ganja Smoking Habit and Their Association with Social Class and Education Status. Int. J. Clin. Pediatr. Dent. 2014, 7, 86–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pontes, C.C.; Chikte, U.; Kimmie-dhansay, F.; Erasmus, R.T.; Kengne, A.P.; Matsha, T.E. Prevalence of oral mucosal lesions and relation to serum cotinine levels—findings from a cross- sectional study in South Africa. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kusiak, A.; Maj, A.; Cichońska, D.; Kochańska, B.; Cydejko, A.; Świetlik, D. The Analysis of the Frequency of Leukoplakia in Reference of Tobacco Smoking among Northern Polish Population. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 6919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivera, C.; Droguett, D.; Arenas-Márquez, M.-J. Oral mucosal lesions in a Chilean elderly population: A retrospective study with a systematic review from thirteen countries. J. Clin. Exp. Dent. 2017, 9, e276–e283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Number of Patients | Median Age [Years] | |

|---|---|---|

| Total | 2747 | 60 |

| Women | 1832 (66.7%) | 62 |

| Man | 915 (33.3%) | 63 |

| Oral Mucosa Lesions | 22 OMLs n = 2301 83.8% of the Whole Sample | Women n = 1546, 84.4% of the Whole Sample | Men n = 755, 82.5% of the Whole Sample | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | % of the Whole Sample | Age Median | No. | % of the Whole Sample | Age Median | No. | % of the Whole Sample | Age Median | |

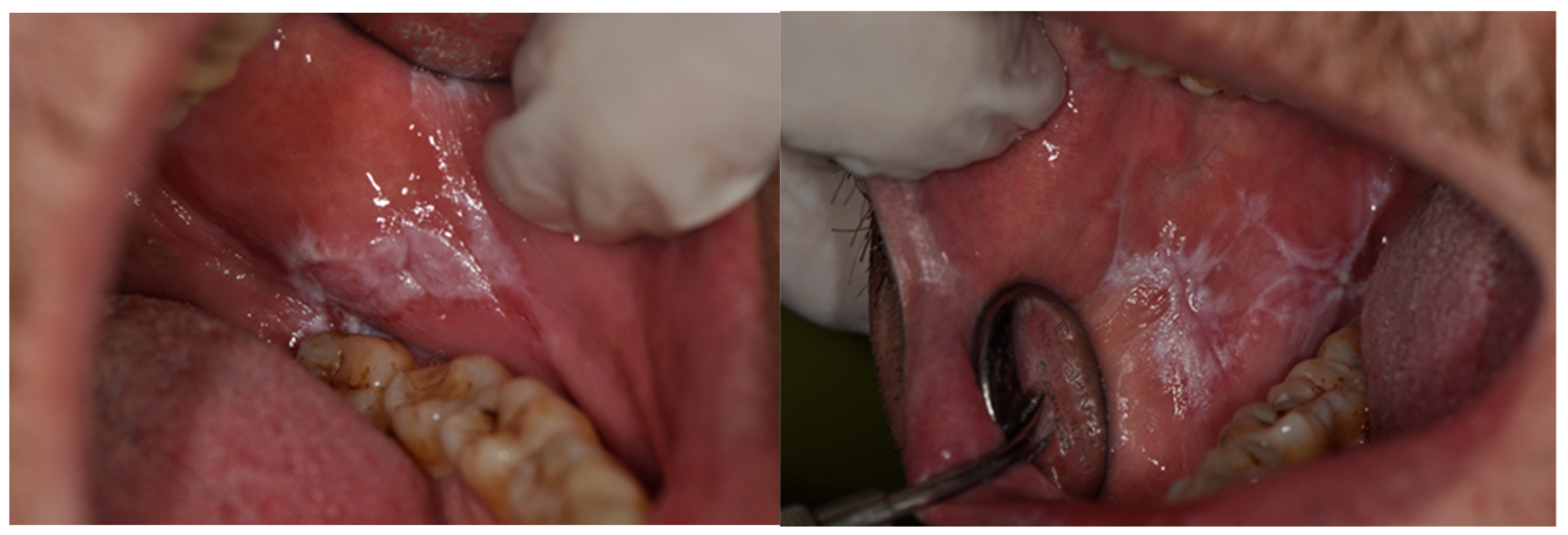

| OLP/OLL (white and white-atrophic forms) | 324 | 11.8 | 62.0 | 268 | 14.6 | 62.5 | 56 | 6.1 | 60.0 |

| Fibroma | 229 | 8.3 | 60.0 | 141 | 7.7 | 60.0 | 88 | 9.6 | 63.0 |

| Oral candidiasis | 183 | 6.7 | 67.0 | 140 | 7.6 | 67.0 | 43 | 4.7 | 63.0 |

| Leukoplakia | 176 | 6.4 | 54.5 | 111 | 6.1 | 57.0 | 65 | 7.1 | 51.0 |

| Traumatic lesions (ulcers, erosions) | 172 | 6.3 | 58.0 | 117 | 6.4 | 61.0 | 55 | 6.0 | 46.0 |

| BMS | 145 | 5.3 | 67.0 | 108 | 5.9 | 67.0 | 37 | 4.0 | 66.0 |

| Aphthae | 135 | 4.9 | 35.0 | 83 | 4.5 | 39.0 | 52 | 5.7 | 23.0 |

| Denture stomatitis | 112 | 4.1 | 69.0 | 73 | 4.0 | 71.0 | 39 | 4.3 | 65.0 |

| Mucocele | 105 | 3.8 | 36.0 | 51 | 2.8 | 39.0 | 54 | 5.9 | 30.0 |

| Geographic tongue | 101 | 3.7 | 57.0 | 64 | 3.5 | 59.0 | 37 | 4.0 | 50.0 |

| Hairy tongue | 95 | 3.4 | 53.0 | 45 | 2.5 | 58.0 | 50 | 5.5 | 45.0 |

| Morsicatio buccarum | 83 | 3.0 | 43.0 | 54 | 3.0 | 51.0 | 29 | 3.2 | 26.0 |

| Glossodynia | 66 | 2.4 | 63.0 | 47 | 2.6 | 63.0 | 19 | 2.1 | 68.0 |

| Epulis | 63 | 2.3 | 47.0 | 44 | 2.4 | 54.5 | 19 | 2.1 | 33.0 |

| OLP/OLL (erosive/bullous forms) | 62 | 2.2 | 66.0 | 47 | 2.6 | 67.0 | 15 | 1.6 | 65.0 |

| Papilloma | 52 | 1.9 | 47.5 | 24 | 1.3 | 58.5 | 28 | 3.1 | 43.0 |

| Gingival enlargement | 38 | 1.4 | 37.5 | 20 | 1.1 | 49.5 | 18 | 2.0 | 33.0 |

| Hemangioma | 36 | 1.3 | 64.5 | 16 | 0.9 | 64.5 | 20 | 2.2 | 64.5 |

| Xerostomia | 34 | 1.2 | 70.5 | 26 | 1.4 | 68.0 | 8 | 0.9 | 75.0 |

| Frictional hyperkeratosis | 32 | 1.2 | 59.5 | 23 | 1.3 | 57.0 | 9 | 1.0 | 62.0 |

| Angular cheilitis | 29 | 1.0 | 67.0 | 23 | 1.3 | 67.0 | 6 | 0.7 | 68.0 |

| Desquamative gingivitis | 29 | 1.0 | 57.0 | 21 | 1.1 | 58.0 | 8 | 0.9 | 49.0 |

| 22 Most Frequent OMLs | Total 2301—100% | |

|---|---|---|

| Female 67.2% | Male 32.8% | |

| 1.OLP/OLL (white and white-atrophic forms) | 82.7% | 17.3% |

| 2.Fibroma | 61.6 | 38.4 |

| 3.Oral candidiasis | 76.5 | 23.5 |

| 4.Leukoplakia | 63.1 | 36.9 |

| 5.Traumatic lesions (ulcers, erosions) | 68.0 | 32.0 |

| 6.BMS | 74.5 | 25.5 |

| 7.Aphthae | 61.5 | 38.5 |

| 8.Denture stomatitis | 65.2 | 34.8 |

| 9.Mucocele | 48.6 | 51.4 |

| 10.Geographic tongue | 63.3 | 36.6 |

| 11.Hairy tongue | 47.4 | 52.6 |

| 12.Morsicatio buccarum | 65.1 | 34.9 |

| 13.Glossodynia | 71.2 | 28.8 |

| 14.Epulis | 69.8 | 30.2 |

| 15.OLP/OLL (erosive/bullous forms) | 75.8 | 24.2 |

| 16.Papilloma | 46.1 | 53.9 |

| 17.Gingival enlargement | 52.6 | 47.3 |

| 18.Hemangioma | 44.4 | 55.6 |

| 19.Xerostomia | 76.5 | 23.5 |

| 20.Frictional hyperkeratosis | 71.9 | 28.1 |

| 21.Angular cheilitis | 79.3 | 20.7 |

| 22.Desquamative gingivitis | 72.4 | 27.6 |

| Age of the Patients | OLP/OLL White | Fibroma | Oral Candidiasis | Leukoplakia | Traumatic Lesion | BMS | Aphthae | Denture St. | Mucocele | Geographic T. | Hairy T. | Morsicatio Bucc. | Glossodynia | Epulis | Erosive OLP/OLL | Papilloma | Gingival enlar. | Hemangioma | Xerostomia | Fric. Hyperkeratosis | Angular Cheilitis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fibroma | 0.03 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Oral candidiasis | 0.00 | 0.00 | |||||||||||||||||||

| Leukoplakia | 0.00 | 0.06 | 0.00 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Traumatic lesion | 0.01 | 0.49 | 0.00 | 0.72 | |||||||||||||||||

| BMS | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.76 | 0.00 | 0.00 | ||||||||||||||||

| Aphthae | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | |||||||||||||||

| Denture Stomatitis | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.03 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.09 | 0.00 | ||||||||||||||

| Mucocele | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.000 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.86 | 0.00 | |||||||||||||

| Geographic Tongue | 0.00 | 0.05 | 0.00 | 0.32 | 0.19 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | ||||||||||||

| Hairy Tongue | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.16 | 0.10 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.69 | |||||||||||

| Morsicatio Buccarum | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.09 | 0.00 | 0.06 | 0.03 | 0.10 | ||||||||||

| Glossodynia | 0.31 | 0.04 | 0.23 | 0.00 | 0.03 | 0.13 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | |||||||||

| Epulis | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.29 | 0.44 | 0.43 | 0.00 | ||||||||

| Erosive OLP/OLL | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.57 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.43 | 0.00 | 0.02 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.45 | 0.00 | |||||||

| Papilloma | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.12 | 0.06 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.46 | 0.69 | 0.38 | 0.00 | 0.84 | 0.00 | ||||||

| Gingival Enlargement | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.50 | 0.00 | 0.36 | 0.02 | 0.06 | 0.59 | 0.00 | 0.23 | 0.00 | 0.23 | |||||

| Hemangioma | 0.18 | 0.06 | 0.45 | 0.00 | 0.04 | 0.265 | 0.00 | 0.04 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.832 | 0.00 | 0.65 | 0.00 | 0.00 | ||||

| Xerostomia | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.08 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.144 | 0.00 | 0.65 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.02 | 0.00 | 0.06 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.06 | |||

| Frictional Hyperkeratosis | 0.02 | 0.23 | 0.00 | 0.97 | 0.87 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.82 | 0.42 | 0.03 | 0.04 | 0.13 | 0.00 | 0.20 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.00 | ||

| Angular Cheilitis | 0.15 | 0.13 | 0.45 | 0.05 | 0.19 | 0.47 | 0.00 | 0.06 | 0.00 | 0.03 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.99 | 0.01 | 0.72 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.95 | 0.07 | 0.03 | |

| Desquam. Gingivitis | 0.02 | 0.44 | 0.00 | 0.42 | 0.99 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.56 | 0.28 | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.08 | 0.00 | 0.16 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.00 | 0.84 | 0.06 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Radwan-Oczko, M.; Sokół, I.; Babuśka, K.; Owczarek-Drabińska, J.E. Prevalence and Characteristic of Oral Mucosa Lesions. Symmetry 2022, 14, 307. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym14020307

Radwan-Oczko M, Sokół I, Babuśka K, Owczarek-Drabińska JE. Prevalence and Characteristic of Oral Mucosa Lesions. Symmetry. 2022; 14(2):307. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym14020307

Chicago/Turabian StyleRadwan-Oczko, Małgorzata, Iga Sokół, Katarzyna Babuśka, and Joanna E. Owczarek-Drabińska. 2022. "Prevalence and Characteristic of Oral Mucosa Lesions" Symmetry 14, no. 2: 307. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym14020307