~25 Ma Ruby Mineralization in the Mogok Stone Tract, Myanmar: New Evidence from SIMS U–Pb Dating of Coexisting Titanite

Abstract

1. Introduction

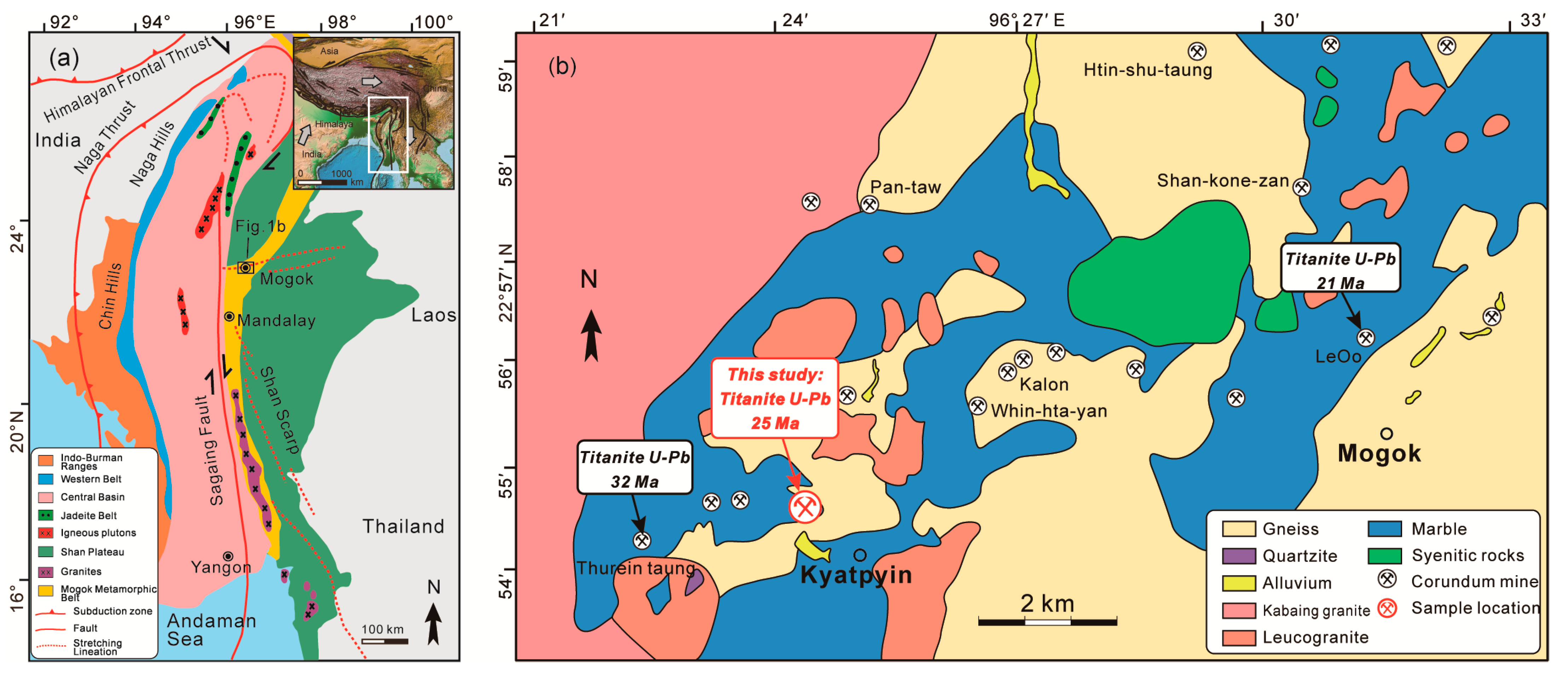

2. Geological Setting and Sample Description

3. Analytical Methods

3.1. Whole-Rock Major and Trace Elements

3.2. Major and Minor Elements of Minerals

3.3. Trace Elements of Minerals

3.4. Titanite U–Pb Dating

4. Results

4.1. Whole-Rock Compositions

4.2. Mineral Chemistry

4.3. Titanite U–Pb Geochronology

5. Discussion

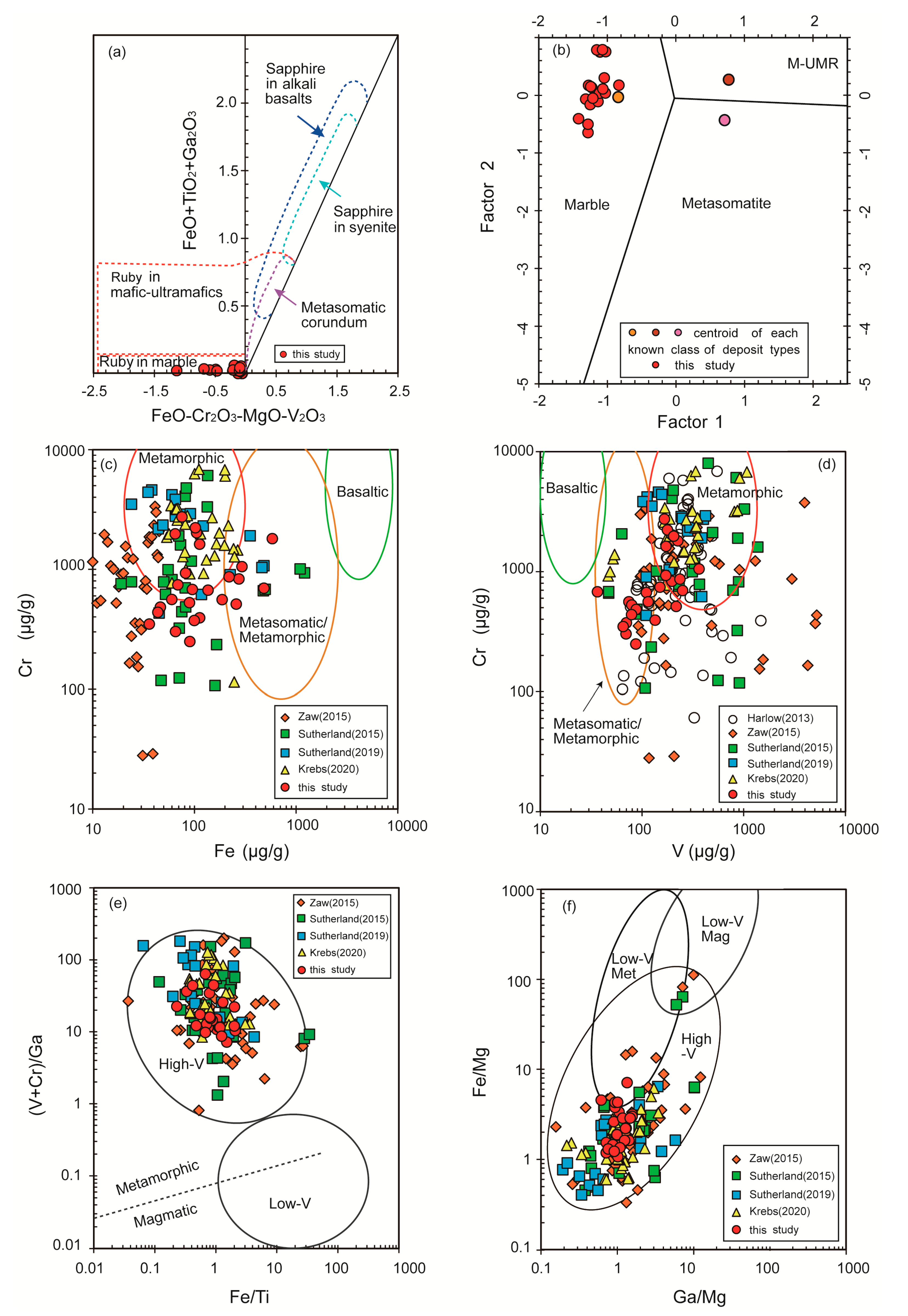

5.1. Chemical Characteristics of the Studied Ruby

5.2. Chemical Characteristics of the Studied Titanite

5.3. Ruby Formation Age in the MMB

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Balmer, W.A.; Hauzenberger, C.A.; Fritz, H.; Sutthirat, C. Marble–hosted ruby deposits of the Morogoro Region, Tanzania. J. Afr. Earth Sci. 2017, 134, 626–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giuliani, G.; Groat, L.; Fallick, A.; Pignatelli, I.; Pardieu, V. Ruby deposits: A review and geological classification. Minerals 2020, 10, 597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sotheby’s Magnificient Jewels and Noble Jewels, Auction 502. 2005. Available online: http://www.sothebys.com (accessed on 28 July 2020).

- Harlow, G.E.; Bender, W. A study of ruby (corundum) compositions from the Mogok Belt, Myanmar: Searching for chemical fingerprints. Am. Miner. 2013, 98, 1120–1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Themelis, T. Gems and Mines of Mogok; A&T Pub.: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Garnier, V.; Maluski, H.; Giuliani, G.; Ohnenstetter, D.; Schwarz, D. Ar–Ar and U–Pb ages of marble–hosted ruby deposits from central and southeast Asia. Can. J. Earth Sci. 2006, 43, 509–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phyo, M.M.; Wang, H.A.O.; Guillong, M.; Berger, A.; Franz, L.; Balmer, W.A.; Krzemnicki, M.S. U–Pb dating of zircon and zirconolite inclusions in marble–hosted gem–quality ruby and spinel from Mogok, Myanmar. Minerals 2020, 10, 195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Searle, M.P.; Garber, J.M.; Hacker, B.R.; Htun, K.; Gardiner, N.J.; Waters, D.J.; Robb, L.J. Timing of syenite–charnockite magmatism and ruby and sapphire metamorphism in the Mogok valley region, Myanmar. Tectonics 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.B.; Zheng, Y.F.; Zhao, Z.F.; Gong, B.; Liu, X.M.; Wu, F.Y. U–Pb, Hf and O isotope evidence for two episodes of fluid–assisted zircon growth in marble–hosted eclogites from the Dabie orogen. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 2006, 70, 3743–3761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaw, K.; Sutherland, F.L.; Graham, I.T.; McGee, B. Dating zircon inclusions in gem corundums from placer deposits, as a guide to their origin. In Proceedings of the 33rd International Geological Congress (IGC), Oslo, Norway, 5–14 August 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Zaw, K.; Sutherland, F.L.; Graham, I.T.; Meffre, S.; Thu, K. Dating zircon inclusions in gem corundum deposits and genetic implications. In Proceedings of the 13th Quadrennial IAGOD Symposium, Adelaide, Australia, 5–10 April 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Sutherland, F.L.; Zaw, K.; Mere, S.; Thompson, J.; Goemann, K.; Thu, K.; Nu, T.; Zin, M.; Harris, S. Diversity in ruby geochemistry and its inclusions: Intra– and inter–continental comparisons from Myanmar and Eastern Australia. Minerals 2019, 9, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belley, P.M.; Dzikowski, T.J.; Fagan, A.; Cempírek, J.; Groat, L.A.; Mortensen, J.K.; Fayek, M.; Giuliani, G.; Fallick, A.E.; Gertzbein, P. Origin of scapolite–hosted sapphire (corundum) near Kimmirut, Baffin Island, Nunavut, Canada. Can. Miner. 2017, 55, 669–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohn, M. Titanite petrochronology. Rev. Miner. Geochem. 2017, 83, 419–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aleinikoff, J.N.; Wintsch, R.P.; Fanning, C.M.; Dorais, M.J. U–Pb geochronology of zircon and polygenetic titanite from the Glastonbury Complex, Connecticut, USA: An integrated SEM, EMPA, TIMS, and SHRIMP study. Chem. Geol. 2002, 188, 125–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Storey, C.D.; Jeffries, T.E.; Smith, M. Common lead–corrected laser ablation ICP–MS U–Pb systematics and geochronology of titanite. Chem. Geol. 2006, 227, 37–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willigers, B.; Baker, J.A.; Krogstad, E.J.; Peate, D.W. Precise and accurate in situ Pb–Pb dating of apatite, monazite, and sphene by laser ablation multiple–collector ICP–MS. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 2002, 66, 1051–1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frost, B.R.; Chamberlain, K.R.; Schumacher, J.C. Sphene (titanite): Phase relations and role as a geochronometer. Chem. Geol. 2000, 172, 131–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spencer, K.J.; Hacker, B.R.; Kylander Clark, A.R.C.; Andersen, T.B.; Cottle, J.M.; Stearns, M.A.; Poletti, J.E.; Seward, G.G.E. Campaign–style titanite U–Pb dating by laser–ablation ICP: Implications for crustal flow, phase transformations and titanite closure. Chem Geol. 2013, 341, 84–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zhou, H.W.; Li, Q.L.; Xiang, H.; Zhong, Z.Q.; Brouwer, F.M. Palaeozoic polymetamorphism in the North Qinling orogenic belt, Central China: Insights from petrology and in situ titanite and zircon U–Pb geochronology. J. Asian Earth Sci. 2014, 92, 77–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasmussen, B.; Fletcher, I.R.; Muhling, J.R. Dating deposition and low–grade metamorphism by in situ U–Pb geochronology of titanite in the Paleoproterozoic Timeball Hill Formation, southern Africa. Chem. Geol. 2013, 351, 29–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling, X.X.; Schmädicke, E.; Li, Q.L.; Gose, J.; Wu, R.H.; Wang, S.Q.; Liu, Y.; Tang, G.Q.; Li, X.H. Age determination of nephrite by in–situ SIMS U–Pb dating syngenetic titanite: A case study of the nephrite deposit from Luanchuan, Henan, China. Lithos 2015, 220–223, 289–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garnier, V.; Giuliani, G.; Ohnenstetter, D.; Fallick, A.E.; Dubessy, J.; Banks, D.; Hoàng, Q.V.; Lhomme, T.; Maluski, H.; Pêcher, A.; et al. Marble–hosted ruby deposits from central and southeast Asia: Towards a new genetic model. Ore Geol. Rev. 2008, 34, 169–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, A.H.G. Cretaceous–Cenozoic tectonic events in the western Myanmar (Burma)–Assam region. J. Geol. Soc. Lond. 1993, 150, 1089–1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, A.H.G.; Htay, M.T.; Htun, K.M.; Win, M.N.; Oo, T.; Hlaing, T. Rock relationships in the Mogok metamorphic belt, Tatkon to Mandalay, central Myanmar. J. Asian Earth Sci. 2007, 29, 891–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Searle, M.P.; Noble, S.R.; Cottle, J.M.; Waters, D.J.; Mitchell, A.H.G.; Hlaing, T.; Horstwood, M.S.A. Tectonic evolution of the Mogok metamorphic belt, Burma (Myanmar) constrained by U–Th–Pb dating of metamorphic and magmatic rocks. Tectonics 2007, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertrand, G.; Rangin, C. Tectonics of the western margin of the Shan plateau (central Myanmar): Implication for the India–Indochina Oblique convergence since the Oligocene. J. Asian Earth Sci. 2003, 21, 1139–1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.Z.; Chung, S.J.; Wu, F.Y.; Zhang, C.; Xu, Y.; Wang, J.G.; Chen, Y.; Guo, S. Tethyan suturing in Southeast Asia: Zircon U–Pb and Hf–O isotopic constraints from Myanmar ophiolites. Geology 2016, 44, 311–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barley, M.E.; Pickard, A.L.; Zaw, K.; Rak, P.; Doyle, M.G. Jurassic to Miocene magmatism and metamorphism in the Mogok metamorphic belt and the India–Eurasia collision in Myanmar. Tectonics 2003, 22, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, S.; Chen, Y.; Liu, C.Z.; Wang, J.G.; Su, B.; Gao, Y.J.; Wu, F.Y.; Sein, K.; Yang, Y.H.; Mao, Q. Scheelite and coexisting F–rich zoned garnet, vesuvianite, fluorite, and apatite in calc–silicate rocks from the Mogok metamorphic belt, Myanmar: Implications for metasomatism in marble and the role of halogens in W mobilization and mineralization. J. Asian Earth Sci. 2016, 117, 82–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, A.; Chung, S.L.; Oo, T.; Lin, T.H.; Hung, C.H. Zircon U–Pb ages in Myanmar: Magmatic–metamorphic events and the closure of a neo–Tethys ocean? J. Asian Earth Sci. 2012, 56, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Searle, M.P.; Waters, D.J.; Morley, C.K.; Gardiner, N.J.; Htun, U.K.; Nu, T.T.; Robb, L.J. Chapter 12 Tectonic evolution of the Mogok metamorphic and Jade mines belts and ophiolitic terranes of Burma (Myanmar). In Myanmar: Geology, Resources and Tectonics; Barber, A.J., Zaw, K., Crow, M.J., Eds.; Geological Society: London, UK, 2017; Volume 48, pp. 261–293. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, S.; Chen, Y.; Li, Y.B.; Su, B.; Zhang, Q.H.; Aung, M.M.; Sein, K. Cenozoic ultrahigh–temperature metamorphism in metapelitic granulites from the Mogok metamorphic belt, Myanmar. Sci. China Earth Sci. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamont, T.N.; Searle, M.P.; Hacker, B.R.; Htun, K.; Htun, K.M.; Morley, C.K.; Waters, D.J.; White, R.W. Late Eocene–Oligocene granulite facies garnet–sillimanite migmatites from the Mogok metamorphic belt, Myanmar, and implications for timing of slip along the Sagaing Fault. Lithos 2021, 386–387, 106027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, S.; Chu, X.; Hermann, J.; Chen, Y.; Li, Q.L.; Wu, F.Y.; Liu, C.Z.; Sein, K. Multiple episodes of fluid infiltration along a single metasomatic channel in metacarbonates (Mogok metamorphic belt, Myanmar) and implications for CO2 release in orogenic belts. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 2021, 126, e2020JB020988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Win, M.M.; Enami, M.; Kato, T. Metamorphic conditions and CHIME monazite ages of Late Eocene to Late Oligocene high–temperature Mogok metamorphic rocks in central Myanmar. J. Asian Earth Sci. 2016, 117, 304–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thu, Y.K.; Enami, M.; Kato, T.; Tsuboi, M. Granulite facies paragneisses from the middle segment of the Mogok metamorphic belt, central Myanmar. J. Miner. Petrol. Sci. 2017, 112, 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Thu, Y.K.; Win, M.M.; Enami, M.; Tsuboi, M. Ti–rich biotite in spinel and quartz–bearing paragneiss and related rocks from the Mogok metamorphic belt, central Myanmar. J. Miner. Petrol. Sci. 2016, 111, 270–282. [Google Scholar]

- Thu, K. The Igneous Rocks of the Mogok Stone Tract: Their Distribution, Petrography, Petrochemistry Sequence, Geochronology and Economic Geology. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Yangon, Yangon, Myanmar, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Gardiner, N.J.; Robb, L.J.; Morely, C.K.; Searle, M.P.; Cawood, P.A.; Whitehouse, M.J.; Kirkland, C.L.; Roberts, N.M.W.; Myint, T.A. The tectonic and metallogenic framework of Myanmar: A Tethyan mineral system. Ore Geol. Rev. 2016, 79, 26–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaw, K. Geological evolution of selected granitic pegmatites in Myanmar (Burma): Constraints from regional setting, lithology, and fluid–inclusion studies. Int. Geol. Rev. 1998, 40, 647–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thein, M. Modes of occurrence and origin of precious gemstone deposits of the Mogok Stone Tract. J. Myanmar Geosci. Soc. 2008, 1, 75–84. [Google Scholar]

- Zaw, K.; Sutherland, F.L.; Yui, T.F.; Mere, S.; Thu, K. Vanadium–rich ruby and sapphire within Mogok Gemfield, Myanmar: Implications for gem color and genesis. Miner. Depos. 2015, 50, 25–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitney, D.L.; Evans, B.W. Abbreviations for names of rock–forming minerals. Am. Miner. 2010, 95, 185–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrade, S.; Hypolito, R.; Ulbrich, H.H.; Silva, M.L. Iron (II) oxide determination in rocks and minerals. Chem. Geol. 2002, 182, 85–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.L.; Zhao, L.; Zhang, Y.B.; Yang, J.H.; Kin, J.N.; Han, R.H. Zircon–titanite–rutile U–Pb system from metamorphic rocks of Jungshan “Group” in Korea: Implications of tectono–thermal events from Paleoproterozoic to Mesozoic. Acta Petrol. Sin. 2016, 32, 3019–3032. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, Q.; Evans, N.J.; Ling, X.X.; Yang, J.H.; Wu, F.Y.; Zhao, Z.D.; Yang, Y.H. Natural titanite reference materials for in situ U–Pb and Sm–Nd isotopic measurements by LA–(MC)–ICP–MS. Geostand. Geoanal. Res. 2019, 43, 355–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ludwig, K.R. User’s Manual for Isoplot/Ex Rev. 2.49; Berkeley Geochronology Centre Special Publication: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2001; p. 56. [Google Scholar]

- Tera, F.; Wasserburg, G.J. U–Th–Pb systematics in three Apollo 14 basalts and the problem of initial Pb in lunar rocks. Earth Planet Sci. Lett. 1972, 14, 281–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutherland, L.; Zaw, K.; Meffre, S.; Yui, T.–F.; Thu, K. Advances in trace element “Fingerprinting” of gem corundum, ruby and sapphire, Mogok Area, Myanmar. Minerals 2015, 5, 61–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krebs, M.Y.; Hardman, M.F.; Pearson, D.G.; Luo, Y.; Fagan, A.J.; Sarkar, C. An evaluation of the potential for determination of the geographic origin of ruby and sapphire using an expanded trace element suite plus Sr–Pb isotope compositions. Minerals 2020, 10, 447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palke, A.C. Coexisting rubies and blue sapphires from major world deposits: A brief review of their mineralogical properties. Minerals 2020, 10, 472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giuliani, G.; Caumon, G.; Rakotosamizanany, S.; Ohnenstetter, D.; Rakotondrazafy, A.F.M. Classification chimique des corindons par analyse factorielle discriminante: Application à la typologie des gisements de rubis et saphirs. Rev. Gemmol. 2014, 188, 14–22. [Google Scholar]

- Uher, P.; Giuliani, G.; Szakall, S.; Fallick, A.E.; Strunga, V.; Vaculovic, T.; Ozdin, D.; Greganova, M. Sapphires related to alkali basalts from the Cerová Highlands, Western Carpathians (southern Slovakia): Composition and origin. Geol. Carp. 2012, 63, 71–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pryce, M.H.L.; Runciman, W.A. The absorption spectrum of corundum. Discuss Faraday Soc. 1958, 26, 34–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutherland, F.L.; Abduriyim, A. geographic typing of gem corundum: A test case from Australia. J. Gemmol. 2009, 31, 203–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calligaro, T.; Poirot, J.P.; Querré, G. Trace element fingerprinting of jewelry rubies by external beam PIXE. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. B 1999, 150, 628–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oberti, R.; Smith, D.C.; Rossi, G.; Caucia, F. The crystal chemistry of high–aluminium titanites. Eur. J. Miner. 1991, 3, 777–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oberti, R.; Rossi, G.; Smith, D.C. X–ray crystal structure refinement studies of the TiO ⇊ Al (OH, F) exchange in high aluminium sphenes. Terra Cogn. 1985, 5, 428. [Google Scholar]

- Higgins, J.B.; Ribbe, P.H. The crystal chemistry and space groups of natural and synthetic titanites. Am. Miner. 1976, 61, 878–888. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, X.Y.; Zheng, Y.F.; Chen, Y.X.; Guo, J. Geochemical and U–Pb age constraints on the occurrence of polygenetic titanites in UHP metagranite in the Dabie orogen. Lithos 2012, 136–139, 93–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, P.; Yang, K.F.; Fan, H.R.; Liu, X.; Cai, Y.C.; Yang, Y.H. Titanite–scale insights into multi–stage magma mixing in Early Cretaceous of NW Jiaodong terrane, North China Craton. Lithos 2016, 258–259, 197–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.W.; Deng, X.D.; Zhou, M.F.; Liu, Y.S.; Zhao, X.F.; Guo, J.L. Laser ablation ICP–MS titanite U–Th–Pb dating of hydrothermal ore deposits: A case study of the Tonglushan Cu–Fe–Au skarn deposit, SE Hubei Province, China. Chem. Geol. 2010, 270, 56–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Y.Y.; Niu, Y.L.; Zhang, H.F.; Wang, K.L.; Lizuka, Y.; Lin, J.Y.; Tan, Y.L.; Xu, Y.J. Effects of decarbonation on elemental behaviors during subduction–zone metamorphism: Evidence from a titanite–rich contact between eclogite–facies marble and omphacitite. J. Asian Earth Sci. 2017, 135, 338–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Horstwood, M.S.A.; Foster, G.L.; Parrish, R.R.; Noble, S.R.; Nowell, G.M. Common–Pb corrected in situ U–Pb accessory mineral geochronology by LA–MC–ICP–MS. J. Anal. At. Spectrom. 2003, 18, 837–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simonetti, A.; Heaman, L.M.; Chacko, T.; Banerjee, N.R. In situ petrographic thin section U–Pb dating of zircon, monazite, and titanite using laser ablation–MC–ICPMS. Int. J. Mass Spectrom. 2006, 253, 87–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, M.J.; Qin, K.Z.; Evans, N.J.; Li, G.M.; Ling, X.X.; Mcinnes, B.I.A.; Zhao, J.X. Titanite in situ SIMS U–Pb geochronology, elemental and Nd isotopic signatures record mineralization and fluid characteristics at the Pusangguo skarn deposit, Tibet. MD. Miner. Depos. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stacey, J.S.; Kramers, J.D. Approximation of terrestrial lead isotope evolution by a two–stage model. Earth Planet Sci. Lett. 1975, 26, 207–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertrand, G.; Rangin, C.; Maluski, H.; Bellon, H. Diachronous cooling along the Mogok metamorphic belt (Shan scarp, Myanmar): The trace of the northward migration of the Indian syntaxis. J. Asian Earth Sci. 2001, 19, 649–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iyer, L.A.N. The Geology and Gem–Stones of the Mogok Stone Tract, Burma. Memoirs of the Geological Survey of India; Calcutta: Delhi, India, 1953; Volume 82. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell, A. Chapter 7 Mogok Metamorphic Belt. In Geological Belts, Plate Boundaries, and Mineral Deposits in Myanmar; Elsevier: Amesterdam, The Netherland, 2018; pp. 235–236. [Google Scholar]

| Sample/ | [U] | [Th] | Th/U | 238U | ±s | 207Pb | ±s | 207Pb-corr | ±s | f206% |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spot # | μg/g | μg/g | 206Pb | % | 206Pb | % | age (Ma) | (Ma) | ||

| 13MK79-1 | 1159 | 897 | 0.8 | 228 | 1.9 | 0.134 | 0.8 | 25.04 | 0.53 | {11.35} |

| 13MK79-2 | 1433 | 279 | 0.2 | 248 | 1.9 | 0.085 | 1.0 | 24.72 | 0.48 | {5.46} |

| 13MK79-3 | 1141 | 170 | 0.1 | 239 | 2.0 | 0.096 | 1.1 | 25.22 | 0.50 | {7.46} |

| 13MK79-4 | 1192 | 279 | 0.2 | 241 | 1.9 | 0.089 | 1.0 | 25.25 | 0.50 | {5.53} |

| 13MK79-5 | 1136 | 290 | 0.3 | 243 | 1.9 | 0.093 | 1.2 | 24.86 | 0.48 | {7.32} |

| 13MK79-6 | 1155 | 252 | 0.2 | 240 | 1.9 | 0.089 | 1.0 | 25.38 | 0.49 | {5.97} |

| 13MK79-7 | 629 | 197 | 0.3 | 230 | 1.9 | 0.127 | 1.1 | 25.14 | 0.51 | {11.45} |

| 13MK79-8 | 1027 | 622 | 0.6 | 238 | 1.9 | 0.096 | 1.0 | 25.38 | 0.49 | {7.80} |

| 13MK79-9 | 1211 | 180 | 0.1 | 240 | 1.9 | 0.090 | 1.0 | 25.36 | 0.49 | {6.03} |

| 13MK79-10 | 1108 | 530 | 0.5 | 240 | 1.9 | 0.090 | 1.1 | 25.37 | 0.49 | {5.89} |

| 13MK79-11 | 900 | 569 | 0.6 | 239 | 1.9 | 0.108 | 1.1 | 24.82 | 0.49 | {7.21} |

| 13MK79-12 | 1224 | 575 | 0.5 | 245 | 1.9 | 0.093 | 1.0 | 24.75 | 0.48 | {6.44} |

| 13MK79-13 | 1229 | 419 | 0.3 | 243 | 1.9 | 0.082 | 1.0 | 25.30 | 0.48 | {4.96} |

| 13MK79-14 | 1208 | 397 | 0.3 | 242 | 1.9 | 0.086 | 1.2 | 25.27 | 0.49 | {4.31} |

| 13MK79-15 | 578 | 396 | 0.7 | 231 | 1.9 | 0.119 | 1.6 | 25.31 | 0.51 | {10.69} |

| 13MK80-1 | 1305 | 222 | 0.2 | 241 | 1.9 | 0.087 | 1.2 | 25.28 | 0.49 | {5.63} |

| 13MK80-2 | 1217 | 399 | 0.3 | 243 | 1.9 | 0.091 | 1.0 | 24.98 | 0.48 | {5.65} |

| 13MK80-3 | 1412 | 163 | 0.1 | 245 | 1.9 | 0.090 | 1.0 | 24.78 | 0.48 | {6.75} |

| 13MK80-4 | 1858 | 451 | 0.2 | 248 | 2.0 | 0.075 | 0.9 | 24.97 | 0.49 | {3.95} |

| 13MK80-5 | 1323 | 275 | 0.2 | 241 | 2.0 | 0.084 | 1.1 | 25.37 | 0.50 | {5.31} |

| 13MK80-6 | 1233 | 263 | 0.2 | 243 | 1.9 | 0.090 | 1.0 | 25.01 | 0.48 | {6.82} |

| 13MK80-7 | 1122 | 399 | 0.4 | 243 | 1.9 | 0.087 | 1.2 | 25.07 | 0.48 | {4.65} |

| 13MK80-8 | 1223 | 764 | 0.6 | 234 | 1.9 | 0.115 | 0.9 | 25.08 | 0.51 | {8.29} |

| 13MK80-9 | 879 | 249 | 0.3 | 237 | 1.9 | 0.107 | 1.3 | 25.05 | 0.50 | {11.13} |

| 13MK80-10 | 1456 | 233 | 0.2 | 243 | 1.9 | 0.084 | 0.9 | 25.23 | 0.49 | {5.15} |

| 13MK80-11 | 1337 | 273 | 0.2 | 245 | 1.9 | 0.087 | 1.1 | 24.86 | 0.48 | {5.74} |

| 13MK80-12 | 1191 | 1004 | 0.8 | 230 | 1.9 | 0.119 | 0.9 | 25.35 | 0.51 | {9.75} |

| 13MK80-13 | 1384 | 303 | 0.2 | 245 | 1.9 | 0.089 | 1.0 | 24.80 | 0.49 | {5.56} |

| 13MK80-14 | 1219 | 579 | 0.5 | 242 | 1.9 | 0.093 | 1.0 | 25.00 | 0.48 | {6.46} |

| 13MK80-15 | 1160 | 506 | 0.4 | 242 | 1.9 | 0.093 | 1.0 | 25.04 | 0.49 | {7.73} |

| 13MK80-16 | 1328 | 257 | 0.2 | 246 | 2.0 | 0.084 | 1.2 | 24.90 | 0.50 | {6.18} |

| 13MK80-17 | 1160 | 807 | 0.7 | 226 | 1.9 | 0.148 | 1.3 | 24.82 | 0.53 | {13.80} |

| 13MK80-18 | 1122 | 317 | 0.3 | 239 | 1.9 | 0.094 | 1.4 | 25.32 | 0.49 | {6.62} |

| 13MK80-19 | 379 | 412 | 1.1 | 220 | 1.9 | 0.155 | 1.9 | 25.20 | 0.55 | {13.76} |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhang, D.; Guo, S.; Chen, Y.; Li, Q.; Ling, X.; Liu, C.; Sein, K. ~25 Ma Ruby Mineralization in the Mogok Stone Tract, Myanmar: New Evidence from SIMS U–Pb Dating of Coexisting Titanite. Minerals 2021, 11, 536. https://doi.org/10.3390/min11050536

Zhang D, Guo S, Chen Y, Li Q, Ling X, Liu C, Sein K. ~25 Ma Ruby Mineralization in the Mogok Stone Tract, Myanmar: New Evidence from SIMS U–Pb Dating of Coexisting Titanite. Minerals. 2021; 11(5):536. https://doi.org/10.3390/min11050536

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Di, Shun Guo, Yi Chen, Qiuli Li, Xiaoxiao Ling, Chuanzhou Liu, and Kyaing Sein. 2021. "~25 Ma Ruby Mineralization in the Mogok Stone Tract, Myanmar: New Evidence from SIMS U–Pb Dating of Coexisting Titanite" Minerals 11, no. 5: 536. https://doi.org/10.3390/min11050536

APA StyleZhang, D., Guo, S., Chen, Y., Li, Q., Ling, X., Liu, C., & Sein, K. (2021). ~25 Ma Ruby Mineralization in the Mogok Stone Tract, Myanmar: New Evidence from SIMS U–Pb Dating of Coexisting Titanite. Minerals, 11(5), 536. https://doi.org/10.3390/min11050536