Abstract

We conducted a series of column experiments on tailing heap samples from the Picacho mine in California to determine the ability of the native Gram-negative bacteria, Alcaligenes faecalis, to leach gold. To mimic heap leaching using our technique, unprocessed and unsorted tailings of mixed grain sizes were placed into columns and leached for three weeks with four treatments: (1) deionized water, (2) bacteria, (3) NaCN by bacteria and (4) NaCN. In all of the experimental runs, the total Au (mg) recovered from the columns treated with A. faecalis and NaCN followed by A. faecalis yielded gold amounts that were higher than those from the deionized water control, and lower than the columns treated with cyanide. However, the total yields were variable across runs, which we attribute to the inherent heterogeneity of gold distribution in the samples. Statistical tests show that the yields from the treatments employing bacteria and/or cyanide were different from those that employed deionized water alone. Our results support previous studies that showed that exudates of A faecalis promoted reduction of Au3+, catalyzing extracellular Au0 particles under alkaline conditions. We propose that A. faecalis is a possible novel alternative to cyanide treatment for recovering Au from mine tailings, and recommend optimization of the method.

1. Introduction

Many inactive mines contain extractable gold in tailings and remaining ore that could constitute a profitable resource in today’s gold market. Re-opening these mines is expensive, often faces regulatory challenges, and may result in new environmental concerns [1]. One way to minimize the costs associated with renewed mining operations is through biomining techniques. Biomining was pioneered in the 1950s and has been growing in popularity as a more economical and environmentally friendly approach to mineral resource extraction. In gold mines, biomining uses bacteria and other biological systems such as BIOX™ and BIOPRO™ (e.g., [2,3]) to recover refractory gold from low-grade ores (mines with less than 0.2 mg kg−1 gold). However, much of that gold is strongly adsorbed to sulfides, silicates, carbonates and sulfates [4], and is therefore resistant to cyanide extraction.

In recent years, the natural microbiome has been leveraged to solubilize gold from ores without the added step of adapting bacteria to ore conditions [5]. In this study, we evaluated the ability of the microorganism Alcaligenes faecalis, isolated from the wastewaters of a spent mine in Picacho, CA, to mobilize gold associated with pyrite and alteration products [6]. A. faecalis is a heterotroph found in many soils. The organism has been employed to degrade cyanide in contaminated soils. However, it has not been previously used as a biolixiviant. A. faecalis has been shown to produce gold nanoparticles by reducing gold (Au3+) ions [7]. This suggests that A. faecalis could also metabolize and produce gold nanoparticles from mine tailings. We compared the recovery yield from leaching of a low-grade ore with A. faecalis to the yields from conventional cyanide treatment in a series of column experiments. We report the results of analysis of the tailings and effluents obtained by atomic absorption spectroscopy (AAS) and discuss the suitability of using a bacteria species native to the mine as an alternative or complement to conventional cyanide treatment. We will show that despite limitations due to particle size, A faecalis is a promising alternative to cyanidation without adversely impacting the environment.

Background

Gold [Au] is a noble, malleable and precious metal characterized by an opaque yellow coloration and metallic luster. Gold forms alloys with common metals, and has high electrical and thermal conductivity. Gold has six oxidation states (+1, +2, +3, +4, +5, and +7) which provide it with a low reactivity with most anions [8]. However, the most common states of gold are aurous (+1) and auric (+3). Although auric compounds are more stable than aurous compounds, the aurous state is more prevalent in fluids that form ores [8].

Primary gold refers to gold that is precipitated by chemical reactions in hydrothermal solutions to form chloride, thiosulfate, bisulfide and sulfide complexes. Secondary gold is formed from the chemical and mechanical weathering of primary gold particles, and may be the result of microbial weathering [9]. In gold complexes, microbes such as sulfate-reducing bacteria (SRB) excrete metabolites, such as thiosulfate, amino acids and cyanide, which mobilize gold [10]. Microbes have adapted to precipitate otherwise toxic Au complexes as intra- and extracellular metabolic products, e.g., sulfide minerals. Bio-assimilation and solubilization rates depend on factors such as climate, soil geochemistry and the quality of the substrate [8].

The recovery of primary gold is expensive and harmful to the environment. Open-pit mining causes land degradation, produces poisonous gases and pollutes waterways [11]. Chemical leaching with cyanide (CN−) produces toxic effluents that can reach waterways (groundwater, river systems), potentially killing organisms [12]. Despite the environmental risks, the use of gold cyanidation is widespread in high-grade ores because it is economical and has a high recovery rate. Cyanide leaching is less effective in low grade ores, since colloidal gold is often associated with sulfide and sparingly soluble minerals. Additionally, cyanide reacts with carbonaceous matter (known as “preg-robbing”) and may be scavenged by clay minerals, micas, pyrite and ferrihydrite [13], rendering it unavailable to react with gold. The presence of copper minerals such as azurite and malachite in ore can also inhibit gold recovery that uses cyanidation [13].

Biomining is a general term for mining techniques that use microbes to disassociate economically relevant metals from other minerals such as insoluble sulfides and oxides [14,15]. Biomining is used to recover valuable metals from low-grade ores, and it is also used as a pretreatment of low-grade ores to release metals from insoluble matrices. The bioleaching pretreatment of refractory Au ore has been shown to improve recovery yields from cyanidation from 50% to more than 95% [16]. Advances in biomining have allowed the technique to emerge as a viable hydrometallurgical and chemical process for recovering base metals [14]. Chemolithotrophic organisms, such as Acidithiobacillus thiooxidans, Acidithiobacillus ferrooxidans, and Leptospirillum ferrooxidans, have been successfully employed in extracting refractory gold [10,15,17,18]. In addition, organisms that are native to cyanide-contaminated environments have adapted to oxidize cyanide [6], particularly those from the genera Acidithiobacillus, Arthrobacter, Alcaligenes, Actinomyces, Bacillus, Micrococcus, Neisseria, Paracoccus and Pseudomonas [19]. The bacteria we employed in this study, A. faecalis is a heavy-metal-resistant cyanide oxidizer [20] belonging to this group, and has been shown to successfully produce stable extracellular silver and gold nanoparticles [7,21]. Therefore, we hypothesize that A. faecalis is a viable organism for the bioleaching of cyanide-contaminated spent ore.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Site and Sample Collection

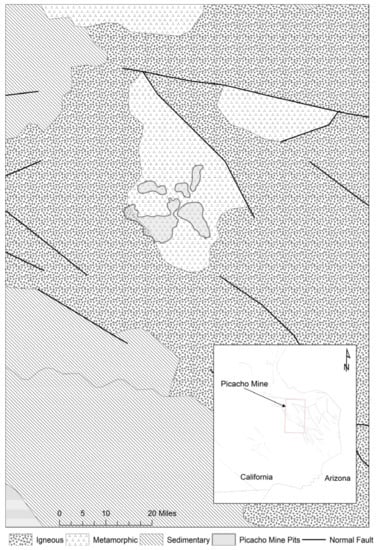

The Picacho gold mine is located in Winterhaven, Imperial County, California, near the Arizona border, less than 16 km northwest from the Little Picacho Wilderness Area and 29 km north of Yuma (Figure 1). The ore was discovered in 1862, and the area was operated as a mine until 2002. The mine has produced an estimated 18.6 Mt of Au [4].

Figure 1.

Map showing the location of the Picacho mine. Data from [22].

The Picacho mine contains low-grade gold characterized by a gold–arsenic–antimony geochemical signature [4]. The gold ore is found only in association with pyrite, and is therefore considered mineralogically simple [4]. Picacho is an orogenic deposit that mineralizes when alkaline hydrothermal fluids carrying gold as a sulfur ligand mixed with an oxidizing hematite-precipitating fluid. The granite–gneissic–silicic sedimentary protolith was metasomatically altered to an albite–chlorite–calcite metasomatic assemblage with secondary pyrite, quartz, hematite, barite and gypsum [4]. The major minerals are albite, quartz and members of the clay family.

Mine tailings were collected from Heap 5 in the Picacho mine, between 2008 and 2010, and stored in lidded, 5-gallon (19 L) high-density polyethylene (HDPE) buckets (Figure S1). The tailings were pink-white in color, and consisted of poorly sorted angular fragments. Grain sizes in the tailings ranged from coarse silt to very coarse pebble. The Au concentration was measured by Atomic Absorption Spectroscopy at American Assay Laboratories (Sparks, Nevada), and ranged from 34 ppb to 1543 ppb (mean Au = 297 ppb; n = 84).

2.2. Bacteria

A bacterium isolated from mining wastewaters at the Picacho mine was obtained as a live culture and preserved in glycerol at −80 °C. Genetic sequencing of the first 500 16S base pairs from rRNA was conducted by Charles River Laboratories (Newark, Delaware), which identified the isolate as Alcaligenes faecalis subsp. phenolicus (NCBI Taxonomy ID: 232846). The sequencing report with confidence scores showing species-level confidence is included in the Supplementary Materials. A. faecalis bacteria is a heterotrophic species found in soil, water and in the intestinal tract of vertebrates. It is a Gram-negative, rod-shaped organism that moves with the aid of flagella. The bacterium is aerobic and uses oxygen as the terminal electron acceptor; however, some strains use anaerobic respiration when they are surrounded by nitrate or nitrite. They grow optimally in a temperature between 30 °C and 37 °C and have a fruity odor [23]. A. faecalis is also a cyanide oxidizer [20]; therefore, it is adapted to the toxic conditions found in the Picacho mine.

Bacteria for the bioleaching experiment were cultivated by inoculating 4 L of proprietary growth media with stock cultures, and incubating these at room temperature (~25 °C) for 2 days to reach a late stationary phase prior to the start of each leaching experiment. The live cultures were confirmed via phase contrast microscopy. The formula for the growth media was a glucose-free broth developed by Pintail Systems, Inc. (Aurora, CO, USA) to enhance gold production. The broth contains NH4Cl, MgCl2, MgSO4, KH2PO4, K2HPO4, FeCl3, Na2S2O3, yeast extract, 30 mL of heavy metal solution (1.5 g EDTA, 0.2 g FeSO4, 0.1 g ZnSO4, 0.2 g MnCl2 in 1000 mL Milli-Q Type 1 deionized water), and bromothymol blue to monitor the pH. This proprietary media was shown by Thompson [19] to catalyze the partial bio-oxidation of trace sulfides and gangue minerals, and produce surfactants that improve the wettability of the ore. All in vitro experiments using bacteria in growth media developed significant bioslime in the 5 days of incubation. The NaCN solution was prepared by dissolving crystalline NaCN (CAS 143-33-9, Alfa Aesar, Tewksbury, MA, USA) in deionized (Type-1) water to a concentration of 200 ppm.

2.3. Microchamber Experiment Setup

We conducted microscale studies of the interaction between microbial biomass and minerals from the Picacho tailings, in order to directly examine how the bacteria acted on the mineral surfaces to release gold. The microchambers used consisted of representative clasts of ore cemented onto a chamber. The ore clasts were selected based on representative mineral grains encountered in the ore (e.g., silicates, carbonates). The clasts were affixed with epoxy to polystyrene microchambers, treated at three time intervals—2 days, 5 days and 10 days, and imaged by electron microscopy before and after treatment with the biolixiviant.

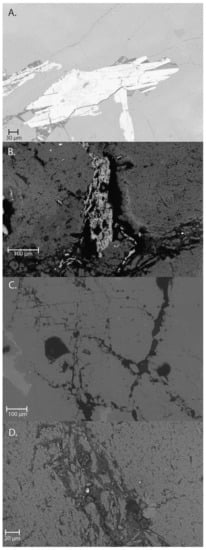

The effect of the biolixiviant on the ore was evaluated by obtaining images of the ore minerals before and after interaction with the bacteria by employing a Zeiss Supra 55 V scanning electron microscope (SEM) equipped with energy dispersive X-ray analyzer (EDS) operating at a 15 kV accelerating voltage and 15 nA beam current with a spot size of 1 μm. Images were obtained of the polished sections to determine the mechanism by which the bacteria create conditions that mobilize gold from encapsulated minerals. Figure 2 shows the bioslime disaggregating an iron-rich mineral and invading minerals along microfractures.

Figure 2.

Scanning electron micrographs of biolixiviant reacting with minerals in Picacho tailings. (A) Shows a bright mineral (Fe-rich) surrounded by a lighter gray mineral (feldspar). (B) Fe-rich grain is disaggregated and invaded by a bioslime. (C) Network of cracks invaded by bioslime. (D) Bioslime fracture showing bright spots corresponding to heavy metals.

2.4. Column Experiment Setup

Four 1 kg subsamples of unsorted ore were transferred into Chromaflex standard chromatography columns (Kimble Chromaflex Borosilicate Glass, 30 × 4.8 cm) equipped with PTFE endcaps housing a 20 µm fritted glass filter. The resulting columns were non-uniform with respect to grain size; smaller grains accumulated in large pore spaces and at the base of the column.

The Picacho tailings were leached by four different sequences of lixiviants: (1) deionized (Milli-Q Type 1) water; (2) bacteria in growth media; (3) cyanide followed by bacteria; and (4) cyanide alone. Typically, bioleaching is employed as a pretreatment for cyanide. In sequence (3), we chose to run NaCN followed by bacteria to mobilize non-refractory gold, in order to compare with the results of Column 2 (bacteria only) and Column 4 (cyanide only) in the Week 3 recoveries. The pH of the cyanide and media solutions at the start of the experiment were 11.5 and 12.5, respectively, and the pH of the effluent at the end of the experiments was 9.37 for cyanide and 8.02 for the biolixiviant. The minimum pH reached for any of the experiments employing cyanide or bacteria was 7.82. Each three-week experiment (one week = 5 days) was performed in triplicate, and included a 1-week flush of deionized water between lixiviant treatments. The full treatment schedule is shown in Table 1. In total, 200 mL of lixiviant/day was pumped into packed columns by a peristaltic pump (Masterflex Model HV-07523-70, Radnor, PA, USA) with size 14 Norprene® tubing (Masterflex, Radnor, PA, USA) at a constant rate of 0.3 mL/min. To prevent pumping air into the columns, the peristaltic pump was connected to a timer that automatically paused pumping after 200 mL was administered (11 h, 7 min). All effluents, including the water flushes (Week 2), were collected from each column in 20 mL fractions (Spectra/Chrom CF-1, Repligen Corporation, Waltham, MA, USA) and transferred to pre-sterilized 50 mL HDPE centrifuge tubes for storage prior to analysis, in order to determine the total gold recovered.

Table 1.

Treatment schedule for leaching experiments.

2.5. Determination of Au Concentration in Tailings and Effluents

After completing the leaching experiments, the ore in the packed columns was separated into thirds (top, middle and bottom) and air-dried. Then, 15 g of dry ore from each subsample was prepared for Au analysis using the nickel sulfide fire assay method, as described by Juvonen et al. [24]. The ore was finely ground, added to a nickel-sulfide flux, and fired to 1000 °C in a furnace to separate metals from siliceous minerals. The resulting NiS button was digested in 300 mL of 37% HCl, and the gold was precipitated as AuTe in a SnCl solution. The AuTe precipitate was dissolved in aqua regia for atomic absorption analysis (AAS) to determine the gold concentration.

To test whether the recoveries from the effluents following the various treatments (B—bacteria), CN-B = cyanide/bacteria, CN = cyanide) were statistically different from the water (W) effluent, Student’s t-test was performed based on the (one-tail) null hypothesis that the treatments were no better than the water treatment alone. The t-test results indicated that the Au recovered from the effluent in columns B and CN was greater than that recovered from W, for p < 5%. Specifically, the test for the B columns yielded a t-statistic of 2.85 and a p-value of 2.32, while the CN columns yielded a t-statistic of 3.24 and a p-value of 1.59. However, for CN-B, the t-test was less certain, with p > 5% (t-statistic = 1.47; p-value = 10.76%), due to a high variance in the Au concentration from effluent recoveries.

2.6. Atomic Absorption Spectrometry (AAS)

Dissolved Au from the tailings and effluent fractions was analyzed on a Thermo Electron Corporation atomic absorption spectrometer (AAS) M5 series in graphite furnace mode, in order to allow multiple samples to be analyzed without cross contamination. Samples and standards were analyzed in triplicate for 3 s, with a lamp current of 70%, wavelength of 242.8 nm and bandpass of 0.5 nm. Four calibration standards were run for each experiment. The limit of detection (6.2 ppb) and limit of quantification (19 ppb) were calculated from the mean of four runs (Figure S2). For effluent Runs 1 and 2 and tailings Runs 1, 2 and 3, calibration measurements were collected for 0, 25, 50, 75 and 100 ppb. After Runs 1 and 2 yielded low Au concentrations in the effluent, the calibration was adjusted to capture a lower range with standard concentrations at 0, 5, 10 and 20 ppb for the Run 3 effluent. All calibration standards were obtained with instrument auto-dilution of a 0.1 ppm stock Au standard. The calibration curve was obtained using a normal linear least squares fit.

2.7. X-ray Diffraction (XRD)

The mineralogy of the tailings was determined via X-ray powder diffraction (XRD). The samples were prepared through powdering in an agate mortar with methanol to form a slurry. Each sample was mounted on a glass slide and analyzed on a Malvern-Panalytical X’Pert Pro with Pixcel1D detector and a copper X-ray source operating at 40 kv tension and 40 mA current, with a 1° divergence slit on the incident beam and a 5.7 mm anti-scatter slit on the diffracted beam. The mineralogy was determined by processing XRD patterns with X’Pert HighScore Plus software, in order to obtain peak matches to the ICDD Powder Diffraction File database, and were found to be similar across all samples.

3. Results

3.1. Mineralogy of the Picacho Tailings

The results of X-ray diffraction analysis of the Heap 5 tailings consistently showed in the peak position (2θ angle) and relative intensity that chlorite was the predominant clay mineral, along with variable amounts of other phyllosilicates such as zeolite, muscovite and kaolinite. A representative XRD pattern is shown in Figure 3. The silicate minerals albite, potassium feldspar, microcline and quartz were also present in all of the samples used in the experiments. Other minerals, such as nontronite and hematite, were found in the samples, but with greater uncertainties due to peak overlaps with more abundant minerals.

Figure 3.

Representative X-ray diffraction pattern showing generalized mineralogy of tailings. Minerals present: clinochlore (L), zeolite (Z), albite (A), muscovite (M), feldspar (F), microcline (X), kaolinite (K) and quartz (Q).

3.2. Total Au Recoveries in Column Tailings and Effluents

The Au recovered from ore tailings in each column experimental run (4 treatments × 3 weeks) was equal to the average Au mass from each set of 3 subsamples (top, middle, bottom). The total Au recovery in column effluent (Aueff) is the product of the effluent concentration and volume (Equation (1)) of daily collections aggregated after five days.

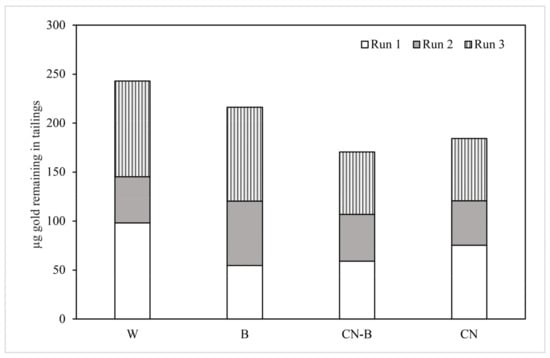

The mass of Au remaining in the tailings after each treatment in the three experimental iterations is shown on Table 2. The columns treated with water (W) contained the most gold in the ore, with a mean yield of 81.03 µg of Au after treatment. In contrast, tailings treated with A. faecalis (B) yielded a mean of 72.13 µg, 11.62% less than W, while the cyanide-treated columns (CN-B and CN) yielded smaller recoveries of 56.86 µg and 61.43 µg, respectively. The cumulative recoveries (in µg) for the columns and tailings are shown in Figure 4 and Figure 5, respectively.

Table 2.

Average Au mass recovered from tailings and effluents in experimental Runs 1, 2 and 3.

Figure 4.

Total Au remaining in column tailings in µg. Lixiviant treatments are noted as follows: W for deionized water; B for A. faecalis; CN-B for cyanide-bacteria; and CN for cyanide columns.

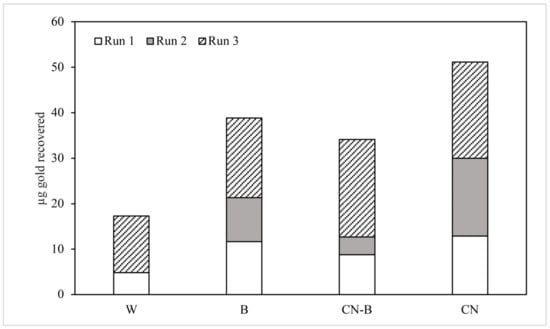

Figure 5.

Au recovered from column effluents, in µg. Symbology is the same as that used in Figure 4.

An initial review of gold recovered from column effluents indicates that CN treatment produced the highest yield, with a mean of 17.03 µg of Au extracted over 5 days. The next highest recovery was from column B effluents (12.94 µg), followed by columns CN-B (11.37 µg) and W (5.76 µg). The recovery from columns treated with bacteria was 27.29% less than the Au recovered from CN-treated columns, but 12.13% greater than that recovered from CN-B-treated columns.

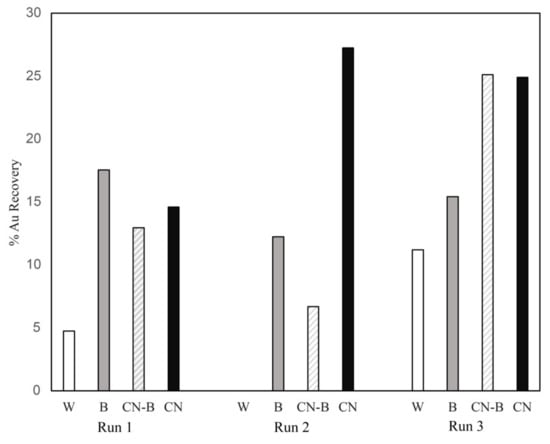

3.3. Effluent Au Recoveries by Experimental Run

In the first week, the Au yield from the effluent varied significantly in all the columns (Table 3). We attribute this variation to the heterogeneity in gold distribution inherent to the unsorted Heap 5 samples. The Run 2 yields from the W column for all three weeks, and from the B, CN-B and CN columns for Weeks 2 and 3, were lower than the detection limit of the instrument. The low Au mass recovered from the tailings after leaching indicates that the Au in the Run 2 samples was not accessible to the lixiviants beyond the first week of treatment. In Runs 1 and 3, the recoveries for Week 2 were similar for all treatments, with averages of 1.04 ± 0.39 (Run 1) and 9.90 ± 0.68 (Run 3).

Table 3.

Weekly Au recovered from effluents for the three experimental runs, in µg. The values shown below the detection limit of 25 ppb in Run 1 and Run 2, and 5 ppb in Run 3, are marked “–“.

The Au recoveries from the effluents as a percentage of total gold recovered (post-run tailings + effluent) are shown in Figure 6. Overall, the % recovery from the B column was comparable to the recoveries from the CN-B and CN columns. However, most of the Au was leached in Week 1. In Run 3, the % recovery was higher for all the columns than in the previous runs, possibly due to a higher starting concentration of Au in the Heap 5 subsample. This possibility is reflected in the remaining gold measured in the tailings after treatment with the lixiviants.

Figure 6.

Percent gold recovery for each of the three runs (100% × Total mass Au in effluents/Sum of Au in effluents + tailings after treatment). W = water; B = bacteria; CN-B and CN = cyanide.

4. Discussion

Our experiments tested how well a new biolixiviant, containing live cultures of an organism native to the Picacho, CA spent mine, mobilizes gold from tailings that had been previously leached with cyanide. The results showed that in two of the three runs A. faecalis, alone or following cyanide treatment, recovered gold from the ore as well as or better than from cyanide treatment alone. This result is consistent with flask experiments employing Picacho ore that was pulverized to a uniform grain size (100 mesh) prior to treatment, and where more gold was recovered by A. faecalis than with NaCN in most but not in all iterations (L. Thompson, personal communication). A. faecalis is ubiquitous in soils, and is well adapted to a wide range of pH conditions [7]. The bacteria is known for its ability to oxidize cyanide [20]; therefore, it has the potential to resist and remediate mining byproducts [25,26] such as the ones that exist in the Picacho tailings.

The mechanism by which gold is mobilized by A. faecalis most likely involves a combination of surfactant bioproduction, an increase in mineral surface reactivity and accelerated weathering facilitated by bioslime peptides and protein stabilization of Au nanoparticles. Organisms such as A. faecalis produce surfactants that improve contact between the leach solution and ore [19]. These biosurfactants are known to cause desorption of carbon sources from minerals, which leads to greater bioavailability, and can stimulate bioslime contact with metals that leads to subsequent mobilization [27,28].

The resistance of A. faecalis to potentially toxic metals such as copper, cadmium, chromium and arsenic, as well as some antibiotics, is attributed to its ability to adapt its cell wall to metal stress through chelation with phosphates [29]. For example, A. faecalis strain VITSIM2 overexpresses specific proteins and peptides to increase peptidoglycan content in the cell walls to combat metal stress [29]. We propose that peptide production improves the reaction kinetics for mineral alteration, thereby facilitating gold dissolution and transport. In fact, El-Deeb et al. [7] showed that A. faecalis releases protein exudates to produce and stabilize Au nanoparticles (AuNP). They demonstrated that a pH of 3 encouraged nucleation, but modulating the pH from 5 to 10 resulted in larger NPs. We can expect that Au accumulated by sorption on tailing mineral surfaces was augmented by A. faecalis and the alkaline pH (12.5) of the biolixiviant.

It has been demonstrated that A. faecalis reduces Au3+ ions extracellularly, which eliminates the need for sonication of the tailings or additional surfactants to destroy the cell walls to release Au. It follows that the process by which A. faecalis mobilizes Au in our experiments may also be via reduction of gold through extracellular processes. Furthermore, peptides in the A. faecalis bioslime released in response to metal stressors may also accelerate the alteration of silicate minerals, as indicated by electron micrographs of microchamber tests (Figure 2). Block et al. [30] showed that peptides, such as those produced as microbial exudates, induce exfoliation of 2:1 layered clays, thus reducing crystallinity, akin to an acceleration of the weathering process to release encapsulated gold. Jorjani and Sabzkoohi [31] reviewed the mechanisms by which biolixiviants mobilize gold, including the ability for native heterotrophs such as Bacillus species and Pseudomonads to produce amino acids that form gold complexes. We hypothesize that this is the mechanism that A. faecalis employs to extract gold in our experiments, consistent with the research of El-Deeb et al. [5].

Typically, biolixiviants are employed as a pretreatment to cyanide leaching to help increase yields from gold mine tailings. However, the effectiveness of the treatment may be limited by the mineralogy of the ore, encapsulation of gold by pyrite and quartz, and the heterogeneities in the distribution of gold in the tailings [32,33,34,35]. Andrianandraina et al. [36] showed that the gold dissolution rate by cyanide was improved by reducing the grain size of gold sulfides during a bacterial oxidation pretreatment step. Furthermore, in their study of the effectiveness of gold bioleaching using the native organism, Thiobacillus ferrooxidans, Attia and El-Zeky [37] showed that bioleaching as a precursor to cyanide leaching removes the need for pulverization of the ore. Our use of cyanide followed by the biolixiviant did not yield a different result than that using only cyanide or only bacteria. Since A. faecalis can recover gold without employing cyanide, implementing a grinding step prior to treatment may enhance recovery without an increased risk to the environment from following biolixiviant pretreatment with cyanide. Curreli et al. [17] found that although grinding, roasting and cyanidation increased gold recovery by 85% compared to cyanidation alone, bioleaching pretreatment and grinding increased gold recovery by 77%, thereby suggesting that this procedure is a viable option, due to its lower cost and environmental impact than roasting. Although adding a pulverization step prior to bioleaching increases the cost of extraction, our results suggest that gold in the Picacho ore may be more effectively mobilized when more mineral surface area is available to the bacteria. The variability in gold recovery in our experimental runs, and the low Au recoveries after two weeks of leaching, is attributed in this study to the heterogeneity in gold distribution across the Heap 5 subsamples used in the columns, or to Au being occluded by minerals. This also suggests that in the Picacho tailings, where gold is encapsulated with pyrite or quartz or is associated with clay minerals, pulverization of the ore to a uniform fine sand grain size or smaller may facilitate gold extraction by all the lixiviants used in this study. However, a more uniform, smaller grain size would eliminate percolation or heap leaching as an option, and may instead require a tank reactor to maximize contact with the mineral surfaces.

Our results showed that A. faecalis can perform as well as than CN and better than water as a lixiviant, and is most effective at mobilizing Au using A. faecalis when treatment is carried through two weeks, after which the recoveries sharply decrease.

5. Conclusions

The purpose of this study was to compare the recovery yield between leaching of a low-grade ore by Alcaligenes faecalis, deionized water, NaCN and bacteria combined, and NaCN treatments. We were able to show that using bacteria alone as treatment had very similar Au recovery yields to that of NaCN, indicating that the use of A. faecalis is an encouraging option for Au leaching of mine tailings.

In typical biomining applications, bacteria are monitored for various parameters that guarantee optimal oxidation rates and growth and survival of the bacteria during the leaching process. Since A. faecalis is not an organism that is typically used in mining operations, this information is not readily available in the literature. We recommend that future studies better define the mechanisms of the interaction by monitoring cyanide concentrations over the course of the experiments, with the goal of determining the ability of A. faecalis to remediate residual cyanide contamination while simultaneously biomineralizing gold. In addition, this new method can be optimized to achieve greater yields by reducing the grain size of the mine tailings, increasing the residence time of the bacteria, and modulating the timing of nutrient replenishment. Overall, the study shows that A. faecalis may be effective as a post-treatment or as an alternative to cyanidation alone.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/min13030410/s1, Figure S1: Bucket (19 L) of Heap 5 samples from the Picacho mine; Figure S2: Example Au calibration of AAS; Table S1: Au recovery from column tailings after lixiviant treatment; Charles River Laboratories sequencing report.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, K.A.B.-C., S.L.D. and N.C.S.; methodology, Y.S.P., S.L.D. and N.C.S.; formal analysis, Y.S.P. and K.A.B.-C.; resources, S.L.D. and N.C.S.; data curation, Y.S.P. and K.A.B.-C.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.S.P.; writing—review and editing, K.A.B.-C., S.L.D. and N.C.S.; visualization, K.A.B.-C. and S.L.D.; supervision, K.A.B.-C.; project administration, K.A.B.-C.; funding acquisition, N.C.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by G2 Bio, LLC award number 76560-0001 to the Research Foundation of the City University of New York.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge Jeffrey Steiner, who passed away in 2013, and contributed to the ideas presented here.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- McKinley, J. In New California Gold Rush, Old Mines Reopen. The New York Times, 10 February 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Dew, D.W.; Lawson, E.N.; Broadhurst, J.L. The BIOX® process for biooxidation of gold-bearing ores or concentrates. In Biomining; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1997; pp. 45–80. [Google Scholar]

- Logan, T.C.; Seal, T.; Brierley, J.A. Whole-ore heap biooxidation of sulfidic gold-bearing ores. In Biomining; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2007; pp. 113–138. [Google Scholar]

- Gasparrini, C. General Principles of Mineral Processing. In Gold and Other Precious Metals; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1993; pp. 63–83. [Google Scholar]

- Daibova, E.B.; Lushchaeva, I.V.; Sachkov, V.I.; Karakchieva, N.I.; Orlov, V.V.; Medvedev, R.O.; Nefedov, R.A.; Shplis, O.N.; Sodnam, N.I. Bioleaching of Au-containing ore slates and pyrite wastes. Minerals 2019, 9, 643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Losh, S.; Purvance, D.; Sherlock, R.; Jowett, E.C. Geologic and geochemical study of the Picacho gold mine, California: Gold in a low-angle normal fault environment. Miner. Depos. 2005, 40, 137–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Deeb, B.; Mostafa, N.Y.; Tork, S.; El-Memoni, N. Optimization of green synthesis of gold nanoparticles using bacterial strain Alcaligenes faecalis. Nanosci. Nanotechnol. Lett. 2014, 6, 372–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clemente, R. Gold. In Heavy Metals in Soils: Trace Metals and Metalloids in Soils and Their Bioavailability; Alloway, B.J., Ed.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2013; pp. 515–525. [Google Scholar]

- Southam, G.; Lengke, M.F.; Fairbrother, L.; Reith, F. The biogeochemistry of gold. Elements 2009, 5, 303–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lengke, M.; Southam, G. Bioaccumulation of gold by sulfate-reducing bacteria cultured in the presence of gold (I)-thiosulfate complex. Geochim. Et Cosmochim. Acta 2006, 70, 3646–3661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dudka, S.; Adriano, D.C. Environmental impacts of metal ore mining and processing: A review. J. Environ. Qual. 1997, 26, 590–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donato, D.B.; Nichols, O.; Possingham, H.; Moore, M.; Ricci, P.F.; Noller, B.N. A critical review of the effects of gold cyanide-bearing tailings solutions on wildlife. Environ. Int. 2007, 33, 974–984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venter, D.; Chryssoulis, S.L.; Mulpeter, T. Using mineralogy to optimize gold recovery by direct cyanidation. JOM 2004, 56, 53–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schippers, A.; Hedrich, S.; Vasters, J.; Drobe, M.; Sand, W.; Willscher, S. Biomining: Metal recovery from ores with microorganisms. Geobiotechnology I 2013, 141, 1–47. [Google Scholar]

- Rohwerder, T.; Gehrke, T.; Kinzler, K.; Sand, W. Bioleaching review part A. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2003, 63, 239–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosecker, K. Bioleaching: Metal solubilization by microorganisms. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 1997, 20, 591–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curreli, L.; Loi, G.; Peretti, R.; Rossi, G.; Trois, P.; Zucca, A. Gold recovery enhancement from complex sulphide ores through combined bioleaching and cyanidation. Miner. Eng. 1997, 10, 567–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rawlings, D.E. Biomining: Theory, Microbes and Industrial Processes; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, L.C. Cyanide Biotreatment and Metal Biomineralization in Spent ore and Process Solutions. In Managing Environmental Problems at Inactive and Abandoned Metals Mine Sites; No EPA/625/R-95/007; EPA Seminar Publication: Washington, DC, USA, 1996; pp. 18–29. [Google Scholar]

- Buchanan, R.E.; Gibbons, N.E. Bergey’s Manual of Determinative Bacteriology, 8th ed.; The Williams and Wilkins Co.: Baltim, Egypt, 1974; Volume 1246, pp. 340–348. [Google Scholar]

- Abo-Amer, A.E.; El-Shanshoury, A.E.-R.R.; Alzahrani, O.M. Isolation and Molecular Characterization of Heavy Metal-Resistant Alcaligenes faecalis from Sewage Wastewater and Synthesis of Silver Nanoparticles. Geomicrobiol. J. 2015, 32, 836–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jennings, C.W.; Strand, R.G.; Rogers, T.H. Geologic Map of California: California Division of Mines and Geology, Scale 1:750,000; California Geological Survey Publications: Sacramento, CA, USA, 1977.

- Gonzalez, D.R. Alcaligenes faecalis: Identification and study of its antagonistic properties against Botrytis cinerea. Ph.D. Thesis, Brock University, St. Catharines, ON, Canada, October 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Juvonen, R.; Lakomaa, T.; Soikkeli, L. Determination of gold and the platinum group elements in geological samples by ICP-MS after nickel sulphide fire assay: Difficulties encountered with different types of geological samples. Talanta 2002, 58, 595–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson, G.L.; Ellis, P.J.; Kuhn, P.; Hille, R. Oxidation of arsenite by Alcaligenes faecalis. Environ. Chem. Arsen. 2001, 343–362. [Google Scholar]

- Andhale, M.S. Microbial Degradation of Cyanide Containing Effluent from a Dye Industry. In Biodeterioration 7; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1988; pp. 213–218. [Google Scholar]

- Ron, E.Z.; Rosenberg, E. Natural roles of biosurfactants. Environ. Microbiol. 2001, 3, 229–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cappelletti, M.; Presentato, A.; Piacenza, E.; Firrincieli, A.; Turner, R.J.; Zannoni, D. Biotechnology of Rhodococcus for the production of valuable compounds. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2020, 104, 8567–8594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matilda, S.C.; Shanthi, C. Metal induced changes in trivalent chromium resistant Alcaligenes faecalis VITSIM2. J. Basic Microbiol. 2017, 57, 402–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Block, K.A.; Trusiak, A.; Katz, A.; Alimova, A.; Wei, H.; Gottlieb, P.; Steiner, J.C. Exfoliation and intercalation of montmorillonite by small peptides. Appl. Clay Sci. 2015, 107, 173–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jorjani, E.; Askari Sabzkoohi, H. Gold leaching from ores using biogenic lixiviants–A review. Curr. Res. Biotechnol. 2022, 4, 10–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Addison, R. Gold and silver extraction from sulfide ores. Min. Congr. J. 1980, 66, 47–54. [Google Scholar]

- Attia, Y.; Litchfield, J.; Vaaler, L. Applications of biotechnology in the recovery of gold. Microbiol. Eff. Metall. Process. 1985, 30, 111–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruynesteyn, A.; Hackl, R.P. The biotankleach process for the treatment of refractory gold/silver concentrates. In Microbiological Effects on Metallurgical Processes; Clum, J.A., Haas, L.A., Eds.; Tms-AIME: New York, NY, USA, 1985; pp. 121–127. [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence, R.W.; Bruynesteyn, A. Biological preoxidation to enhance gold and silver recovery from refractory pyritic ores and concentrates. Can. Min. Metall. Bull. 1983, 76, 107–110. [Google Scholar]

- Andrianandraina, S.H.; Dionne, J.; Darvishi-Alamdari, H.; Blais, J.F. Effect of grain size on the bacterial oxidation of a refractory gold sulfide concentrate and its dissolution by cyanidation. Miner. Eng. 2022, 176, 107360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attia, Y.A.; El-Zeky, M. Bioleaching of gold pyrite tailings with adapted bacteria. Hydrometallurgy 1989, 22, 291–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).