Abstract

In this paper, we present some modified relaxed CQ algorithms with different kinds of step size and perturbation to solve the Multiple-sets Split Feasibility Problem (MSSFP). Under mild assumptions, we establish weak convergence and prove the bounded perturbation resilience of the proposed algorithms in Hilbert spaces. Treating appropriate inertial terms as bounded perturbations, we construct the inertial acceleration versions of the corresponding algorithms. Finally, for the LASSO problem and three experimental examples, numerical computations are given to demonstrate the efficiency of the proposed algorithms and the validity of the inertial perturbation.

Keywords:

multiple-sets split feasibility problem; CQ algorithm; bounded perturbation; armijo-line search; self-adaptive step size MSC:

47J20; 47J25; 49J40

1. Introduction

In this paper, we focus on the Multiple-sets Split Feasibility Problem (MSSFP), which is formulated as follows.

where is a bounded and linear operator, , and are nonempty closed and convex sets, and and are Hilbert spaces. When , it is the Split Feasibility Problem (SFP). Byrne in [1,2] introduced the following CQ algorithm to solve the SFP,

where . It is proven that the iterates converge to a solution of the SFP. When and have explicit expressions, the CQ algorithm is easy to carry out. However, and have no explicit formulas in general; thus the computation of and is itself an optimization problem.

To avoid the computation of and , Yang [3] proposed the relaxed CQ algorithm in finite dimensional spaces. The algorithm is

where , and are sequences of closed half spaces containing C and Q, respectively.

As for the MSSFP (1), Censor et al. in [4] proposed the following algorithm,

where is an auxiliary closed subset, and is a function to measure the distance from a point to all the sets and ,

where for every i and j, and , , . The convergence of the algorithm (4) is proved in finite dimensional spaces.

Later, He et al. [5] introduced a relaxed self-adaptive CQ algorithm,

where the sequence , , , where the closed convex sets and are level sets of some convex functions containing and , and self-adaptive step size . They proved that the sequence generated by algorithm (6) converges in norm to , where S is the solution set of the MSSFP.

In order to improve the rate of convergence, many scholars have investigated the choice of the step size of the algorithms. Based on the CQ algorithm (2), Yang [6] proposed the step size

where is a sequence of positive real numbers satisfying and , and . Assuming that Q is bounded and A is a matrix with full column rank, Yang proved the convergence of the underlying algorithm in finite dimensional spaces. In 2012, López et al. [7] introduced another choice of the step size sequence in the algorithm (3) as follows

where , , and they proved the weak convergence of the iteration sequence in Hilbert spaces. The advantage of this choice of the step size lies in the fact that neither prior information about the matrix norm A nor any other conditions on Q and A are required. Recently, Gibali et al. [8] and Chen et al. [9] used step size determined by Armijo-line search and proved the convergence of the algorithm. For more information on the relaxed CQ algorithm and the selection of step size, please refer to references [10,11,12].

On the other hand, in order to make the algorithms converge faster, specific perturbations have been introduced into the iterative format, since the perturbations guide the iteration to a lower objective function value without losing the overall convergence. So far, bounded perturbation recovery has been used in many problems.

Consider the usage of the bounded perturbation for the non-smooth optimization problems, , where f and g are proper lower semicontinuous convex functions in real Hilbert spaces, f is differentiable, g is not necessarily differentiable, and is L-Lipschitz continuous. One of the classic algorithms is the proximal gradient (PG) algorithm, based on which Guo et al. [13] proposed the following PG algorithm with perturbations,

Assume that (i) D is a bounded linear operator, (ii) , (iii) satisfies , and (iv) satisfies . They asserted that the generated sequence converges weakly to a solution. Later, Guo and Cui [14] proposed the modified PG algorithm for solving this problem,

where , h is a -contractive operator. They proved that the sequence generated by the algorithm (8) converges strongly to a solution . In 2020, Pakkaranang et al. [15] considered PG algorithm combined with inertial technique

and they proved its strong convergence under suitable conditions.

For the convex minimization problem, , where is a nonempty closed convex subset in finite dimensional space and the objective function f is convex, Jin et al. [16] presented the following projected scaled gradient (PSG) algorithm with errors

Assume that (i) is a sequence of diagonal scaling matrices, and that (ii) (iii) (iv) are the same as the conditions in algorithm (7); then the generated sequence converges weakly to a solution.

In 2017, Xu [17] applied the superiorization techniques to the relaxed PSG. The iterative form is

where is a sequence in , and is a diagonal scaling matrix. He established weak convergence of the above algorithm under appropriate conditions imposed on and .

For the variational inequality problem (VIP for short) , where F is a nonlinear operator, Dong et al. [18] considered the external gradient algorithm with perturbations

where with the smallest non-negative integer such that

Assume that F is monotonous and L-Lipschitz is continuous and that the error sequence is summable; the sequence generated by the algorithm converges weakly to a solution of the VIP.

For the split variational inclusion problem, Duan and Zheng [19] in 2020 proposed the following algorithm

where A is a bounded linear operator, and are maximal monotone operators. Assuming that , , , and , they proved that the sequence strongly converges to a solution of the split variational inclusion problem, which is also the unique solution of some variational inequality problem.

For the convex feasibility problem, Censor and Zaslavski [20] considered the perturbation resilience and convergence of dynamic string-averaging projection method.

Adding an inertial term can improve the convergence rate, which is also a perturbation. Recently, for a common solution of the split minimization problem and the fixed point problem, Kaewyong and Sitthithakerngkiet [21] combined the proximal algorithm and a modified Mann’s iterative method with the inertial extrapolation and improved related results. Shehu et al. [22] and Li et al. [23] added alternated inertial perturbation to the algorithms for solving the SFP and improved the convergence rate.

At present, the (multiple-sets) split feasibility problem is widely used in application fields, such as CT tomography, image restoration, and image reconstruction, etc. There are many related literatures on the iterative algorithms for solving the (multiple-sets) split feasibility problem. However, there are relatively fewer documents studying the algorithms of the (multiple-sets) split feasibility problem with perturbations, especially with self-adaptive step size. In fact, the latter also has a bounded disturbance recovery property. Motivated by [9,18], we focus on the modified relaxed CQ algorithms to solve the MSSFP (1) in real Hilbert spaces and assert that the proposed algorithms are also bounded-perturbation-resilient.

The rest of the paper is arranged as follows. In Section 2, definitions and notions that will be useful for our analysis are presented. In Section 3, we present our algorithms and prove their weak convergence. In Section 4, we prove that the proposed algorithms have bounded perturbation resilience and construct the inertial modification of the algorithms. Furthermore, finally, in Section 5, we present some numerical simulations to show the validity of the proposed algorithms.

2. Preliminaries

In this section, we first define some symbols and then review some definitions and basic results that will be used in this paper.

Throughout this paper, denotes a real Hilbert space endowed with an inner product and its deduced norm , and I is the identity operator on . We denote by S the solution set of the MSSFP (1). Moreover, represents that the sequence converges strongly (weakly) to x. Finally, we denote by all the weak cluster points of .

An operator is said to be nonexpansive if for all ,

is said to be firmly nonexpansive if for all ,

or equivalently

It is well known that T is firmly nonexpansive if and only if is firmly nonexpansive.

Let C be a nonempty closed convex subset of . Then the metric projection from onto C is defined as

The metric projection is a firmly nonexpansive operator.

Definition 1

([24]). A function is said to be weakly lower semicontinuous at if converges weakly to implies

Definition 2.

If is a convex function, the subdifferential of φ at x is defined as

Lemma 1

([24]). Let C be a nonempty closed and convex subset of ; then for any , the following assertions hold:

- (i)

- (ii)

- (iii)

- (iv)

- .

Lemma 2

([25]). Assume that is a sequence of nonnegative real numbers such that

where the nonnegative sequences and satisfies and , respectively. Then exists.

Lemma 3

([25]). Let S be a nonempty closed and convex subset of and be a sequence in that satisfies the following properties:

- (i)

- ;

- (ii)

Then converges weakly to a point in S.

Definition 3.

An algorithmic operator P is said to be bounded perturbations resilient if the iteration and all converge, where is a sequence of nonnegative real numbers, is a sequence in , and and satisfies

3. Algorithms and Their Convergence

In this section, we introduce two algorithms of the MSSFP (1) and prove their weak convergence. First assume that the following four assumptions hold.

(A1) The solution set S of the MSSFP (1) is nonempty.

(A2) The level sets of convex functions can be expressed by

where and are weakly lower semicontinuous and convex functions.

(A3) For any and , at least one subgradient and can be calculated. The subdifferential and are bounded on the bounded sets.

(A4) The sequences of perturbations is summable, i.e.,

Define two sets at point by

and

where and . Define the function by

where . Then it is easy to verify that the function is convex and differentiable with gradient

and the L-Lipschitz constant of is .

We see that and are half spaces such that for all . We now present Algorithm 1 with Armijo-line search step size.

| Algorithm 1 (The relaxed CQ algorithm with Armijo-line search and perturbation) |

| Given constant , , . Let be arbitrarily chosen, for compute

where and with the smallest non-negative integer such that Construct the next iterate by |

Lemma 4

([6]). The Armijo-line search terminates after a finite number of steps. In addition,

where .

The weak convergence of Algorithm 1 is established below.

Theorem 1.

Let be the sequence generated by Algorithm 1, and the assumptions (A1)∼(A4) hold. Then converges weakly to a solution of the MSSFP (1).

Proof.

Let be a solution of the MSSFP. Note that , , , , , so and , and thus and .

First, we prove that is bounded. Following Lemma 1 (ii), we have

From Lemma 1 (iii), we have that

Since is firmly nonexpensive, , and Lemma 4, we get that

Based on the definition of and Lemma 1 (i), we know that

From assumption (A4), we know that , and thus , it holds that for . We can therefore assume and for , where . Hence, from (24), we get that

Organizing the above formula we know that

Since for , we get

This together with (27) shows that

Using Lemma 2 and assumption (A4), we know the existence of and the boundedness of .

We therefore have

Thus, by taking in the inequality , we have

From (30), we also know

Hence for every we have

Since is bounded, the set is nonempty. Let ; then there exists a subsequence of such that . Next, we show that is a solution of the MSSFP (1), which will show that . In fact, since , then by the definition of , we have

where . For every choose a subsequence such that , then

Following the assumption (A3) on the boundedness of and (32), there exists such that

From the weak lower semicontinuity of the convex function , we deduce from (37) that , i.e., .

Noting the fact that is nonexpansive, together with (31), (34), and A being a bounded and linear operator, we get that

Since , we have

where . From the boundedness assumption (A3), (38), and (39), there exists such that

Then , thus , and therefore . Using Lemma 3, we conclude that the sequence converges weakly to a solution of the MSSFP (1). □

Now, we present Algorithm 2 in which the step size is given by the self-adaptive method and prove its weak convergence.

| Algorithm 2 (The relaxed CQ algorithm with self-adaptive step size and perturbation) |

| Take arbitrarily the initial guess , and calculate

|

The convergence result of Algorithm 2 is stated in the next theorem.

Theorem 2.

Let be the sequence generated by Algorithm 2. Assumptions (A1)∼(A4) hold and satisfies . Then converges weakly to a solution of the MSSFP (1).

Proof.

First, we prove is bounded. Let . Following Lemma 1 (ii), we have

From Lemma 1 (iii), it follows

Similar with (22), it holds that

From Lemma 1 (iv), one has

Organizing the above formula, we obtain that

From assumption (A4), we know that , so we can assume without loss of generality that , , then

So (47) can be reduced as

Using Lemma 2, we get the existence of and the boundedness of .

From (47), we know

then the fact that asserts that . Since is Lipschitz continuity and , we get that

This implies that is bounded, and thus (50) yields . Hence for every we have

4. The Bounded Perturbation Resilience

4.1. Bounded Perturbation Resilience of the Algorithms

In this subsection, we consider the bounded perturbation algorithms of Algorithms 1 and 2. Based on Definition 3, in Algorithm 1, let . The original algorithm is

where is obtained by Armijo-line search step size such that , where . The generated iteration sequence is weakly convergent, which is proved as a special case in Section 3. The algorithm with the bounded perturbation of (53) is that

where and with the smallest non-negative integer such that

The following theorem shows that the algorithm (53) is bounded perturbation-resilient.

Theorem 3.

Proof.

Let . Since and the sequence are bounded, we have

thus

So we can assume that , where , without loss of generality. Replacing with in (20) and using Lemma 1 (iii) show

Since is firmly nonexpensive, and Lemma 4, we get that

Based on the definition of and Lemma 1 (i), we know that

Based on (55), the following formulas holds

Lemma 1 (iii) reads that

Since , we get

This, together with (64), shows that

Using Lemma 2, we know the existence of and the boundedness of .

From (64), it follows that

Thus, we have , and . Hence,

and for every ,

Similarly to with Theorem 1, we conclude that the sequence converges weakly to a solution of the MSSFP (1). □

Remark 1.

When , , the MSSFP reduces to the SFP; thus Theorems 1 and 3 guarantee that algorithm (53) is bounded perturbation-resilient with Armijo-line search step size for the SFP.

Remark 2.

Replace in algorithm (53) by , and by , where , and , . The corresponding algorithm is also bounded perturbation-resilient.

Next, we will prove that Algorithm 2 with self-adaptive step size is bounded perturbation-resilient. Based on Definition 3, let in Algorithm 2. The original algorithm is

where . The iterative sequence converges weakly to a solution of the MSSFP (1); see [26]. Consider the algorithm with the bounded perturbation

where . The following theorem shows that the algorithm (70) is bounded-perturbation-resilient.

Theorem 4.

Proof.

Set , then (71) can be rewritten as , which is the form of Algorithm 2. According to Theorem 2, it suffices to prove that . Since is continuous, we write

where denotes the infinitesimal of the same order of . From the expression of , we obtain

Remark 3.

When , , the MSSFP reduces to the SFP; thus Theorems 2 and 4 guarantee that algorithm (70) is bounded-perturbation-resilient with the self-adaptive step size for the SFP.

4.2. Construction of the Inertial Algorithms by Bounded Perturbation Resilience

In this subsection, we consider algorithms with inertial terms as a special case of Algorithms 1 and 2. In Algorithm 1, letting , , we obtain

where the step size is obtained by Armijo-line search and

Theorem 5.

Proof.

Let , , where

Thus, we know that and satisfies assumption (A4). According to Theorem 1, we conclude that the sequence converges weakly to a solution of the MSSFP (1). □

Considering the algorithm with inertial bounded perturbation

where

According to Theorem 3, it is easy to know that the sequence converges weakly to a solution of the MSSFP (1). More relevant evidence can be found in reference [27].

Similarly, we can get Theorem 6, which asserts that Algorithm 2 with the inertial perturbation is weakly convergent.

Theorem 6.

Assume that (A1)∼(A3) are true; the scalar sequence satisfies , and , and satisfies . Then the sequence is generated by each of the following iterative scheme,

where is the same as (78) and is self-adaptive step size which is the same as in Algorithm 2, converges weakly to a solution of the MSSFP (1).

5. Numerical Experiments

In this section, we compare the asymptotic behavior of algorithms (53) (Chen et al. [9]), (77) (Algorithm 1), (70) (Wen et al. [26]) and (80) (Algorithm 2), denoted by NP1, HP1, NP2, and HP2, respectively. For the sake of convenience, we denote and , respectively. The codes are written in Matlab 2016a and run on Inter(R) Core(TM) i7-8550U CPU @ 1.80 GHz 2.00 GHz, RAM 8.00 GB. We present two kinds of experiments. One is a real-life problem called LASSO problem, the other kind is some numerical simulation including three examples of the MSSFP.

5.1. LASSO Problem

Let us consider the following LASSO problem [28]

where , , , and . The matrix A is generated from a standard normal distribution with mean zero and unit variance. The true sparse signal is generated from uniformly distribution in the interval with random p position nonzero, while the rest is kept zero. The sample data . For the considered MSSFP, let and , . The objective function is defined as .

We report the final error between the reconstructed signal and the true signal. Take as the stopping criterion, where is the true signal. We compare the algorithms NP1, HP1, NP2 and HP2 with Yang’s algorithm [3]. Let for all , , , , , , and of Yang’s algorithm [3].

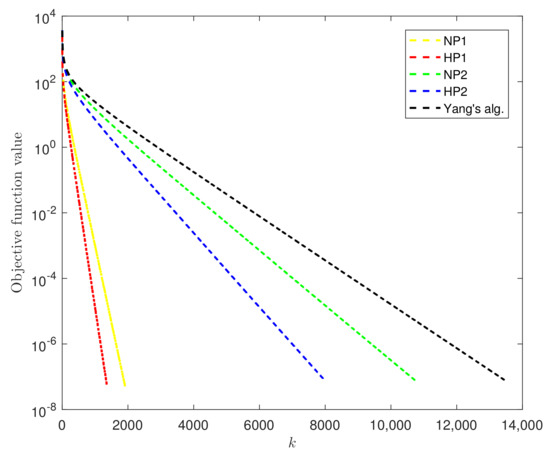

The results are reported in Table 1. Figure 1 shows the objective function value versus iteration numbers when .

Table 1.

Comparison of algorithms with different step size.

Figure 1.

The objective function value versus the iteration number.

From Table 1 and Figure 1, we know that the inertial perturbation can improve the convergence of the algorithms and that the algorithms with Armijo-line search or self-adaptive step size perform better than Yang’s algorithm [3].

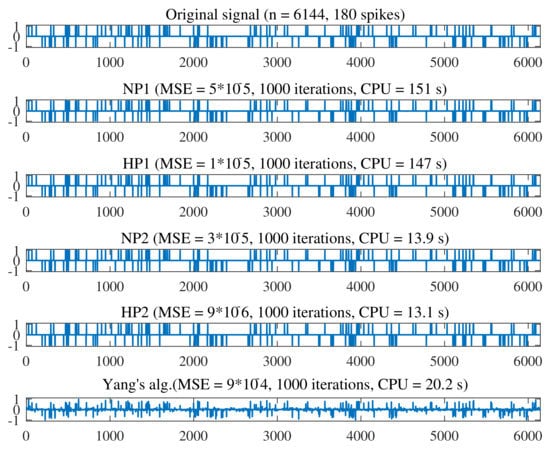

We also measure the restoration accuracy by means of the mean squared error, i.e., MSE , where is an estimated signal of x. Figure 2 shows a comparison of the accuracy of the recovered signals when . Given the same number of iterations, the recovered signals generated by algorithms in this paper outperform the one generated by Yang’s algorithm; NP1 needs more CPU time and presents lower accuracy; algorithms with self-adaptive step size perform better than the algorithms with step size determined by Armijo-line search in CPU time and imposing inertial perturbation accelerates the convergence rate and accuracy of signal recovery.

Figure 2.

Comparison of signal processing.

5.2. Three MSSFP Problems

Example 1

([5]). Take , , and for all , , , , . Define

and

The underlying MSSFP is to find such that .

We use inertial perturbation to accelerate the convergence of the algorithm. For the convenience of comparison, the initial values of the two inertial algorithms are set to be the same. Let . We use to measure the error of the k-th iterate. If , then the iteration process stops. We compare our proposed iteration methods HP1, HP2 with NP1, NP2 and Liu and Tang’s Algorithm 2 in [29]. Algorithm 2 is of the form , . We take , and , and the algorithm is referred to as LT alg.

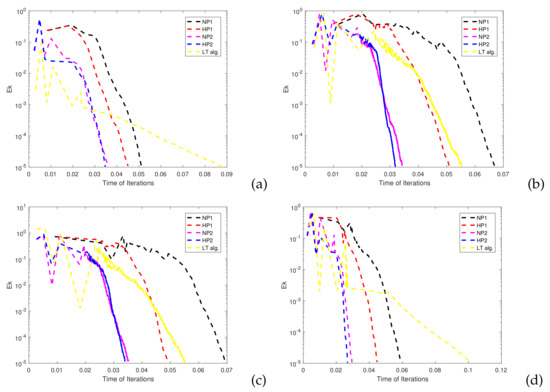

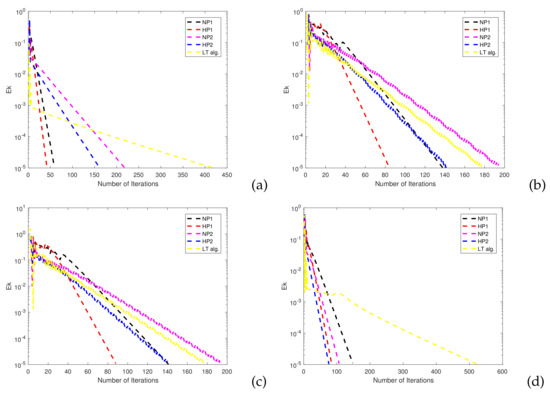

The convergence results and the CPU time of the five algorithms are shown in Table 2 and Figure 3. The errors are shown in Figure 4.

Table 2.

Numerical results of five algorithms for Example 1.

Figure 3.

Comparison of CPU times of the algorithms in Example 1: (a) Comparison for choice 1. (b) Comparison for choice 2. (c) Comparison for choice 3. (d) Comparison for choice 4.

Figure 4.

Comparison of iterations of the algorithms in Example 1: (a) Comparison for choice 1. (b) Comparison for choice 2. (c) Comparison for choice 3. (d) Comparison for choice 4.

The results show that (80) (HP2) outperforms (77) (HP1) for certain initial values. The main reason may be that the self-adaptive step size is more efficient than the one determined by the Armijo-line search. Comparison results of five algorithms and the convergence behavior show that in most cases, the convergence rate of the algorithm can be improved by adding an appropriate perturbation.

Example 2.

Take , , with generated randomly, , , where , , , are all generated randomly. Set and for all , , , , .

We consider using inertial perturbation to accelerate the convergence of the algorithm. If , then the iteration process stops. Let . We choose arbitrarily three different initial points and consider iterative steps of the four algorithms with being different values. See Table 3 for details.

Table 3.

Numerical results of the algorithms with and without perturbation for Example 2.

In this example, we found that the algorithm with Armijo-line search needs fewer iteration steps in relatively low-dimensional spaces. In the case of high-dimensional spaces, the algorithm with self-adaptive step size outperforms in time. Generally, the convergence is improved by inertial perturbations for both algorithms in our paper.

Example 3

([30]). Take , , with generated randomly, , , where , , , , and all elements of the matrix are all generated randomly in the interval (2,10). Set and for all , , , , .

We consider using inertial perturbation to accelerate the convergence of the algorithm. The stopping criterion is defined by . Let . The details are shown in Table 4.

Table 4.

Results of Armijo-line search and self-adaptive algorithms for Example 3.

We can see from Table 4 that the convergence rate is improved by inertial perturbations for both algorithms. In most cases, the algorithm with step size determined by Armijo-line search outperforms the one with self-adaptive step size in the number of iterations, whereas the latter outperforms the former in CPU time.

6. Conclusions

In this paper, for the MSSFP, we present two relaxed CQ algorithms with different kinds of self-adaptive step size and discuss their bounded perturbation resilience. Treating appropriate inertial terms as bounded perturbations, we construct the inertial acceleration versions of the corresponding algorithms. For the real-life LASSO problem and three experimental examples, we numerically compare the performance with or without inertial perturbation of the algorithms and also compare the performance of the proposed algorithms with Yang’s algorithm [3], and Liu and Tang’s algorithm [29]. The results show the efficiency of the proposed algorithms and the validity of the inertial perturbation.

Author Contributions

Both the authors contributed equally to this work. Both authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The authors was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation under Grant No. 61503385 and No. 11705279, and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities No. 3122018L004.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

The authors would also like to thank the editors and the reviewers for their constructive suggestions and comments, which greatly improved the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Byrne, C. Iterative oblique projection onto convex sets and the split feasibility problem. Inverse Probl. 2002, 18, 441–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, C. A unified treatment of some iterative algorithms in signal processing and image reconstruction. Inverse Probl. 2004, 20, 103–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.Z. The relaxed CQ algorithm solving the split feasibility problem. Inverse Probl. 2004, 20, 1261–1266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Censor, Y.; Elfving, T.; Kopf, N.; Bortfeld, T. The multiple-sets spilt feasibility problem and its applications for inverse problems. Inverse Probl. 2005, 21, 2071–2084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, S.N.; Zhao, Z.Y.; Luo, B. A relaxed self-adaptive CQ algorithm for the multiple-sets split feasibility problem. Optimization 2015, 64, 1907–1918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.Z. On variable-step relaxed projection algorithm for variational inequalities. J. Math. Anal. Appl. 2005, 302, 166–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López, G.; Martín-Márquez, V.; Wang, F.H.; Xu, H.K. Solving the split feasibility problem without prior knowledge of matrix norms. Inverse Probl. 2012, 28, 374–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibali, A.; Liu, L.W.; Tang, Y.C. Note on the the modified relaxation CQ algorithm for the split feasibility problem. Optim. Lett. 2018, 12, 817–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Guo, Y.; Yu, Y.; Chen, R. Self-adaptive and relaxed self-adaptive projection methods for solving the multiple-set split feasibility problem. Abstr. Appl. Anal. 2012, 2012, 958040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.K. Iterative methods for the split feasibility problem in infinite-dimensional Hilbert spaces. Inverse Probl. 2010, 26, 105018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.K. A variable Krasnosel’skii-Mann algorithm and the multiple-set split feasibility problem. Inverse Probl. 2006, 22, 2021–2034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Y.H.; Postolache, M.; Liou, Y.C. Strong convergence of a self-adaptive method for the split feasibility problem. Fixed Point Theory Appl. 2013, 2013, 201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.N.; Cui, W.; Guo, Y.S. Perturbation resilience of proximal gradient algorithm for composite objectives. J. Nonlinear Sci. Appl. 2017, 10, 5566–5575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Guo, Y.N.; Cui, W. Strong convergence and bounded perturbation resilience of a modified proximal gradient algorithm. J. Inequalities Appl. 2018, 2018, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pakkaranang, N.; Kumam, P.; Berinde, V.; Suleiman, Y.I. Superiorization methodology and perturbation resilience of inertial proximal gradient algorithm with application to signal recovery. J. Supercomput. 2020, 76, 9456–9477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, W.M.; Censor, Y.; Jiang, M. Bounded perturbation resilience of projected scaled gradient methods. Comput. Optim. Appl. 2016, 63, 365–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.K. Bound perturbation resilience and superiorization techniques for the projected scaled gradient method. Inverse Probl. 2017, 33, 044008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Q.L.; Gibali, A.; Jiang, D.; Tang, Y. Bounded perturbation resilience of extragradient-type methods and their applications. J. Inequalities Appl. 2017, 2017, 280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duan, P.C.; Zheng, X.B. Bounded perturbation resilience of generalized viscosity iterative algorithm for split variational inclusion problem. Appl. Set-Valued Anal. Optim. 2020, 2, 49–61. [Google Scholar]

- Censor, Y.; Zaslavski, A.J. Convergence and perturbation resilience of dynamic string-averaging projection methods. Comput. Optim. Appl. 2013, 54, 65–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaewyong, N.; Sitthithakerngkiet, K. A self-adaptive algorithm for the common solution of the split minimization problem and the fixed point problem. Axioms 2021, 10, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shehu, Y.; Dong, Q.L.; Liu, L.L. Global and linear convergence of alternated inertial methods for split feasibility problems. R. Acad. Sci. 2021, 115, 53. [Google Scholar]

- Li, H.Y.; Wu, Y.L.; Wang, F.H. New inertial relaxed CQ algorithms for solving split feasibility problems in Hilbert spaces. J. Math. 2021, 2021, 6624509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauschke, H.H.; Combettes, P.L. Convex Analysis and Monotone Operator Theory in Hilbert Space; Springer: London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Bauschke, H.H.; Combettes, P.L. A weak-to-strong convergence principle for Fejér-monntone methods in Hilbert spaces. Math. Oper. Res. 2001, 26, 248–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, M.; Peng, J.G.; Tang, Y.C. A cyclic and simultaneous iterative method for solving the multiple-sets split feasibility problem. J. Optim. Theory Appl. 2015, 166, 844–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Dang, Y.Z.; Xu, H.L. Inertial accelerated algorithms for solving a split feasibility problem. J. Ind. Manag. Optim. 2017, 13, 1383–1394. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, Y.C.; Zhu, C.X.; Yu, H. Iterative methods for solving the multiple-sets split feasibility problem with splitting self-adaptive step size. Fixed Point Theory Appl. 2015, 2015, 178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.W.; Tang, Y.C. Several iterative algorithms for solving the split common fixed point problem of directed operators with applications. Optim. A J. Math. Program. Oper. Res. 2016, 65, 53–65. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, J.L.; Yang, Q.Z. Self-adaptive projection methods for the multiple-sets split feasibility problem. Inverse Probl. 2011, 27, 035009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).