Abstract

In the setting of Minkowski set-valued operations, we study generalizations of the difference for (multidimensional) compact convex sets and for fuzzy sets on metric vector spaces, extending the Hukuhara difference. The proposed difference always exists and allows defining Pompeiu-Hausdorff distance for the space of compact convex sets in terms of a pseudo-norm, i.e., the magnitude of the difference set. A computational procedure for two dimensional sets is outlined and some examples of the new difference are given.

1. Introduction

It is well-known that in interval and set-valued arithmetic, the standard addition is not an invertible operation and in particular the algebraic difference is such that . The interval case has been analyzed and solved by several authors since the 1970s, in the setting of interval analysis. In particular, S. Markov proposed an extended interval arithmetic, including a difference (inner difference ) with the basic property that and a division (inner division ) such that (see [1,2,3,4]).

The same problem applies to the general case of (nonempty) compact convex sets in : finding a difference operation as an inverse of Minkowski addition of compact convex sets has been a field of long interest; well-known and largely used examples are: the Hukuhara difference, proposed in [5], but it exists only in specific cases; the geometric Pontryagin difference, proposed in [6], but it may be the empty set; the Demyanov difference, introduced in the setting of subdifferential calculus and nonsmooth analysis (see, e.g., [7,8,9,10,11]).

The Hukuhara difference has been recently generalized in [12], in the setting of fuzzy arithmetic, with applications to differentiability of fuzzy-valued functions of a single variable (see [13,14,15]) and multiple variables (see [16]).

Two other approaches have been proposed in the setting of set-valued analysis: in [17,18,19,20]) directed sets are used; and in [21], the difference of A and B is expressed in terms of minimal pairs of compact convex sets such that (using the Radstrom embedding theorem [22,23]).

On the other hand, inversion of addition is important in set-valued and fuzzy arithmetic and analysis, with many applications e.g., in solving equations and differential equations (for recent results and other references to the fuzzy case, see e.g., [13,14,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34]).

Extending the results in [12,14], we define a generalized difference for general compact convex sets and we extend it to fuzzy sets with compact and convex -cuts. The multidimensional fuzzy case has been addressed only occasionally and by very few papers in the literature; some basic results on the gH-difference for multidimensional intervals (boxes) were obtained in [12] and recently used by [35] in the study of fuzzy vector-valued functions.

The new proposed difference, as we will see, is not unique in the general case; but this is not necessarily a negative aspect: we can add specific requirements to select particular difference sets with additional properties, depending on the application at hand, or we can take the union (or the convexified union) of the existing difference sets obtaining a set with the same properties.

For the convex case, efficient computational procedures are suggested and illustrated for convex sets in . Some of the results contained in this paper have been presented at the 2016 Joint Mathematics Meetings of the AMS Mathematical Association of America (January 6–9, 2016, Seattle, WA). Procedures for the approximation of the new difference in are presented in [36].

The paper is organized as follows. Section 2 introduces some preliminary concepts for compact convex sets and fuzzy sets. Section 3 introduces the new generalized difference for compact convex sets and analyses some of its basic properties. Section 4 presents computational methods and examples in two dimensions. In Section 5 we extend the new difference to the fuzzy case and in Section 6 we conclude with an outline of possible applications.

2. The Space of Compact Convex Sets

Consider the metric vector space , , of real vectors, equipped with standard addition and scalar multiplication operations. Following Diamond and Kloeden (see [37], with applications in [38,39]), denote by the space of nonempty compact convex sets of .

Given two subsets and , Minkowski addition and scalar multiplication are defined by and and it is well-known that addition is associative and commutative and with neutral element . The following properties are well-known ([40]):

For brevity, we will indicate by 0 the neutral element .

A subtraction for two sets can be defined, according to standard Minkowski operations, by and, in general, even when the cancellation law is valid, addition/subtraction simplification is not valid, i.e., and .

For sets in a normed space , the Pompeiu-Hausdorff distance is defined as usual by

where

We denote .

The metric space is complete and separable (see [37,38]).

As is a (real) Hilbert space with internal product and associated norm , we will denote by the unit sphere of .

The support function of a compact convex set is defined by

and the following properties are well-known (see [40]):

Proposition 1.

The support function is positively homogeneous: , and sub-additive: ; we have

and for all ; with respect to Minkowski operations, we have , , .

We can consider the restriction of the support function on the unit sphere and we have

It is possible to see that ([37]))

If is a measure on such that , a distance is defined by

For the sets , we denote

The metric space is complete and separable.

Definition 1.

For a set , the Steiner point is defined by

and . We have that and for all and for all .

The usual properties of the distances apply, e.g., for all :

- P1.

- ;

- P1.

- ;

- P3.

- .

Various attempts to define a difference for compact convex sets, have been proposed in the literature, following different approaches.

Definition 2.

(Hukuhara difference) Given , the Hukuhara difference (H-difference for short) is the set , if it exists, such that ([5]):

Proposition 2.

we have that and ; if it exists, H-difference is unique, but a necessary condition for to exist is that A contains a translate of B. Except for special cases, .

The attempt to generalize the H-difference and in particular to define it such that it exists (and possibly it is unique) for any pair of elements has been extensively studied in the literature. The interval case has been analyzed and solved by several authors since the 1970s, in the setting of interval analysis. In particular, S. Markov proposed an interval extended difference (inner difference) in [1,2,4,41]. The inner-difference, denoted with the symbol “”, is defined by first introducing the inner-sum of A and B

and the following definition is given:

Definition 3.

(Inner difference) Given , the inner difference is the set , if it exists, defined by

An analogous definition has been proposed in [12,42], which includes the multidimensional real intervals and the fuzzy case:

Definition 4.

(generalized Hukuhara difference) Let ; the generalized Hukuhara difference (gH-difference for short) of A and B is the set such that

It is possible that the gH-difference of , as defined by (14), does not exist (see [12] for examples). It is not difficult to see that ; in fact, means i.e., case of (14), or i.e., case of (14). In case of (14) the gH-difference is coincident with the H-difference. Thus the gH-difference, or the inner-difference, is a generalization of the H-difference.

Some properties of are the following (see [12]).

Proposition 3.

The gH-difference , if it exists, is unique and has the following properties:

(1) if and only if ;

(2) (a) ; (b) ;

(3) exists if and only if exists; and ;

(4) if and only if ; and if and only if ;

(5) If exists then at least one of the following equalities or holds true;

(6) If exists, then for all .

We can express the gH-difference of compact convex sets by the use of the support functions. Consider with as defined in (14); let , , and be the support functions of A, B, C, and respectively. In case we have and in case we have . So,

An interesting property relates to and and to the Steiner points of A and B.

Proposition 4.

([12]) If exists, then and . It follows that (for and ). If and are the Steiner points of and C respectively, then . For we have .

The following definition gives a well-known equivalence relation between pairs of compact convex sets (see [17,18,21,23]). Observe first that for any there always exist such that

For example, and give the obvious identity for all . We will denote by the Cartesian product space .

Definition 5.

For pairs and in , the following relation

is an equivalence in . Given , the corresponding equivalence class will be denoted by

Consider the set of all pairs satisfying (16), i.e.,

Proposition 5.

For all , the equivalence class is a nonempty, closed and convex subset of .

Remark 1.

If , from , the Steiner points satisfy ; it follows that

Proposition 6.

Let ; the gH-difference exists if and only if there exists such that or .

Proof.

Consider satisfying . If we have so that . If we have so that . Vice versa, if exists according to (14), then one of the two equalities holds

In case (i), set and ; in case (ii) set and . ☐

Definition 6.

(Radstrom embedding difference) Let ; the difference of A and B can be considered as the equivalence class , i.e.

The pairs of compact convex sets are embedded into the group of the classes associated with the equivalence (17); is endowed with the addition , and the additive inverse of is the class . The difference is and for all ; for all is the zero element in the quotient space .

The Banach space of directed sets in has been introduced in [17,18]; is embedded into by a positively linear map (see [17,18] for details) and the directed difference is defined as follows:

Definition 7.

(Directed difference) Let and let , be the corresponding embedded images of A and B. The directed difference of A and B is defined as the element

From a general point of view, the embedded-based differences are important, but the visualization of the resulting set appears to be difficult and not intuitive.

A second series of constructions is based on a geometric approach in the fields of Convex Geometry, Mathematical Morphology and Set-Valued Analysis; they include Pontryagin-Minkowski difference ([6,11,40,43]). It is possible that the corresponding differences result in the empty set.

Definition 8.

Geometric (Pontryagin) difference: Let ; the geometric difference (also called star difference) of A and B is the set, if not empty,

We have , but it is possible that with and may be empty; its main properties are (see [40])

Definition 9.

(Markov difference [41]): Let ; the inner difference can be obtained in terms of geometric differences (here, or are allowed) as

where or .

In the setting of Non-smooth Analysis and quasi-differential calculus, the following difference of convex compact sets is constructed by using the support functions of A and B (see [7], Chapter III):

Definition 10.

(Demyanov difference) Let ; the Demyanov difference is defined to be the compact convex set C with support function

The Demyanov difference is properly defined for any pair of elements and

Demyanov difference may result in a “big” set (with respect to A and B) and it is not continuous (as an operator) in the Pompeiu-Hausdorff metric (see [39]).

3. A General Difference of Compact Convex Sets

Given , we can associate to A a family of compact intervals that characterize it. For , the support function is defined by

As a dual for the support function we can consider defined by

The following properties of are similar to well-known properties of the support function .

Proposition 7.

The following properties of defined by hold true:

(i)

(ii) and

(iii) i.e., is of Lipschitz type;

(iv) If then for all ;

(v)

(vi)

Proof.

(i) The proof of (i) is obvious since

(ii) follows from the remark that if , then , and consequently,

(iii) follows from (ii) and the Lipschitz property of Indeed,

(iv) If then and then .

(v) Since , from (iv) the required conclusion follows.

(vi) follows easily from (ii) and from Equation (6). ☐

Proposition 8.

The dual support function is positive homogeneous and super additive i.e.,

(i) , ;

(ii) ,

Proof.

(i) For we have

(ii) If then

☐

The homogeneity property of function allows considering its restriction to the unit sphere. The fundamental property of the support function is to uniquely be associated with the set We can get a similar property for

Proposition 9.

For every continuous super additive homogeneous function there exists a unique non-empty compact convex set A such that

Proof.

We can write

and the proposition follows from the similar property of the support function. ☐

We define for each , the compact intervals

We will show in what follows that the family of intervals characterizes (uniquely) any given set .

Proposition 10.

Let ; then

and, consequently,

Proof.

Consider and the intervals and associated with A and B respectively; we know that is equivalent to and , i.e., to . ☐

Lemma 1.

Let . Then, the interval-valued function is continuous and has the following properties:

1. for all and all (homogeneity);

2. for all (sub additivity).

Proof.

Since both and are continuous, and since continuity of interval valued functions in the Pompeiu-Hausdorff distance is the same as continuity of the functions giving the endpoint of the function, the continuity of follows. If then

Also,

Finally combining these results we obtain homogeneity for any The super-additivity of , combined with the sub-additivity of , leads to

which implies . ☐

Homogeneity with respect to all the variables is a plus compared with the classical theories involving only the support function.

Corollary 1.

Let ; then,

(i) , .

(ii) For any and for all

Proof.

(i) We have

(ii) follows from (i) and homogeneity. ☐

The fundamental property of the support interval is

Theorem 1.

The family of intervals such that I is a continuous, homogeneous and sub-additive interval-valued function, uniquely determines the compact convex set

Proof.

Let for ; given I homogeneous and sub-additive, we obtain that the functions are continuous and positively homogeneous. Also, l is super-additive and s is sub-additive Then l determines a compact convex set and s determines the compact convex set . Since I is homogeneous it follows that i.e., that is . Then we can easily see that is equivalent with i.e., . We conclude

☐

The following gH-differences for intervals are well defined

and we have

In midpoint notation, we can write

where and are the midpoint and the radius of interval (similarly for and ).

We will use the interval-valued function defined above throughout the paper. Its first property is given by the following result.

Lemma 2.

For any and for all , the following inclusions are true

Proof.

Let be fixed; from the definition of gH-difference between real intervals, we have that one of the two cases (a) or (b) is true. In case (a), we obtain and from we conclude that for all also and ; we conclude that in case (a), we have

With a similar reasoning, we can see that if (b) is true, then we deduce and

From (a) and (b) we conclude the proof. ☐

Lemma 3.

For any we have

Proof.

The proof is immediate. ☐

Lemma 4.

Let and consider the set

for any the set is closed and convex.

Proof.

is closed because each is closed. To show that is convex, let be such that (and ); then, for all we have ; it follows that and . ☐

Consider now the following set, based on the interval-valued function :

Clearly, may be the empty set, if the closed convex sets do not intersect for different values of (they intersect pairwise, but intersection of three of them may be empty). In any case, has the following property:

Proposition 11.

Let ; the convex (possibly empty) set

is compact and such that , for all sets with

Proof.

If is empty, then obviously . Suppose that is a nonempty closed convex set. To see that it is compact, consider that the interval-valued function is uniformly bounded; in fact its norm is bounded by . In terms of support functions, we have and , i.e., and ; on the other hand, for all , the support function of is such that and from it follows that and consequently . ☐

Corollary 2.

A similar result is true for the interval-valued function ; it defines the convex compact set (it may be empty)

such that and for all nonempty compact convex sets C with and .

Proof.

It is easy to prove that ; indeed, we have so that means ; it follows that i.e., . Analogously, if we also have . The rest of the proof is immediate from Proposition 11. ☐

The set (and similarly ) does not satisfy, in general, the two inequalities in (38); but we can see that the gH-difference , if it exists, satisfies (38):

Proposition 12.

Let and suppose that the gH-difference exists; then we have and ; furthermore we have that

Proof.

We consider only ; for the difference the proof is analogous. From the definition of gH-difference, we have (i) or (ii) . In case (i), consider any ; there exist and such that so that ; in case (ii), consider any ; there exist and such that so that . It follows that C satisfies (38) and so . To complete the proof, it remains to show that also . In case (i), from and , using the properties of the support functions and inverse support functions, we have , and , ; then , and , ; it follows that and the interval-valued function is given by ; we conclude that in case (i), also the inclusion holds and . In case (ii), from and , due to the properties of support and inverse-support functions, we have , and , ; then , and , ; it follows that and the interval-valued function is given by ; we conclude that also in case (ii), . ☐

From the results above, we can conclude the following facts:

Theorem 2.

Let ; the gH-difference exists if and only if there exists a set such that the following inclusions are valid

and the set C is such that

Furthermore, the set C is unique and

The New Difference

The proposed construction of a generalized difference for compact convex sets, when the gH-difference does not exist, is essentially based on the characterization of the gH-difference expressed by Theorem 2.

Lemma 5.

Let ; then

Proof.

We have, in terms of support and dual support ,

and

the two conditions are equivalent to and , i.e., to . ☐

Definition 11.

The new generalized difference will be defined as an element of the family , by requiring appropriate additional conditions. Firstly, observe a convexity property of .

Proposition 13.

For any , the set is a convex subset of , in the sense that and we have .

Proof.

It is immediate that ; we have , , , (equivalently, , ). Then, from , :

, and

, ; from the property , we get

,

and from the convexity of , we deduce , so that , . Equivalently, we can show that ; we have and so that . The conclusion follows. ☐

Example 1.

As an example in , let and so that B is the diagonal of A connecting point to point . It is easy to see that and are elements of ; then, all the sets , , belong to .

Theorem 3.

Given , let be any pair of sets such that ; then i.e., the difference set is the same for all the pairs equivalent to .

Proof.

From we have . If we have , so that and , i.e., and ; applying the cancellation rule we obtain and . Equivalently, from the properties of the support functions, we have , and . It follows that . ☐

Each element of has properties analogous to the gH-difference and, when exists, we have that contains only one element; but for general sets , there exist an infinite number of such “differences”.

To reduce the cardinality of , we have to add some restricting conditions, such as “minimality” requirements.

The first minimality condition is based on set inclusion.

Definition 12.

We say that is minimal with respect to set inclusion (inclusion-minimal for short) if no exists with .

The set of all elements of with the inclusion-minimality property will be denoted by ; it is immediate that .

Remark 2.

By Theorem 3, if and are equivalent pairs, then

Remark 3.

If , we always have that also is an element of ; indeed, we obtain and and .

It follows that unions (or convex hulls of unions) of elements of cannot belong to itself, producing a first reduction of elements with respect to .

The second minimality condition is based on set pseudo-norm (Pompeiu-Hausdorff distance to origin, also called the magnitude of X)

Definition 13.

We say that is minimal with respect to set magnitude (norm-minimal for short) if no exists with .

The set of all elements of with the norm-minimality property will be denoted by . It is immediate that .

Furthermore, there exists a real number , depending only on A and B, such that

clearly, , because .

Remark 4.

By Theorem 3, if and are equivalent pairs, then

Remark 5.

An analogous norm-minimality condition can be given by considering a different distance on , e.g., , or others, depending on the application at hand. A possibly different construction can be obtained by requiring minimality with respect to the diameter of the elements of ; the diameter of C is defined by

( is usually called the difference body of C).

Example 2.

If A, B and , , are as in Example 1, then . Also the 2d-segment where , is an element of and . This is a case where the gH-difference does not exist, and contains several elements.

An interesting property of is that it inherits the convexity from .

Proposition 14.

For any , the set is a convex subset of .

Proof.

Let and . We know that and it remains to show that is H-norm-minimal. We have and for all with . For it is , but strict inequality is not possible because is defined by H-norm minimality (if then and are not minimal). It follows that for all , i.e., is convex. ☐

A very interesting property of norm-minimality is related to the definition of in Equation (45) as the common magnitude of all the elements of ; an interpretation of is that is a convex subset of the “sphere” in of radius (and it coincides with the origin if , i.e., when ).

More precisely, coincides with the Pompeiu-Hausdorff distance in .

Theorem 4.

For all we have

(1) ;

(2) if and only if ;

(3) ;

(4) .

Furthermore,

(5) .

Proof.

Clearly, validity of (5) will imply (1)–(4); but it is interesting to prove them independently of equality (5).

Non-negativity (1) is obvious.

For (2), is the unique element of and ; on the other hand, if then has and , with the consequence that and , i.e., .

The proof of (3) follows immediately from the equalities and .

To prove (4), let , and with

from and we obtain ; from and we obtain . It follows that

and . By the norm-minimality of , we then have

Now we prove (5). Consider the Pompeiu-Hausdorff distance; it is well-known that

where denotes the unit compact (convex) ball of . From the fact that , we have for all and consequently, by the norm minimality of ,

Finally, to prove the reverse inequality, consider the interval valued function defined by (33). It is obvious that for all (this is implied by the inclusion (42)); on the other hand, we have and it follows that is an upper bound for . ☐

With a small abuse of terminology, any element of the families or will be called a generalized difference of A and B, with the corresponding minimality property.

The following property of allows defining a unique set, by collecting all the elements of that belong to at least one set in ; such set will play the role of the total difference of A and B:

Proposition 15.

Let and let ; then .

Proof.

Lets denote for simplicity ; from , , we obtain

and from and we obtain

It follows that . On the other hand, we have and, from the properties of the Pompeiu-Hausdorff distance (see Section 1.8 in [40])

we obtain

from the minimality of X and Y it follows that and we conclude that . ☐

The closure of with respect to convex unions of its elements, combined with Theorem 4, allows the following definition:

Definition 14.

Let be given. The following convex set always exists and is unique

has the following basic properties:

(1) ;

(2) ;

(3) ;

(4) is norm-minimal with respect to ;

(5) if and only if ;

(6) ;

(7) if the gH-difference exists then ;

(8) the magnitude of coincides with the Pompeiu-Hausdorff distance, i.e., .

The set will be called the total gH-difference of A and B (t-difference for short).

From property (8) of the t-difference we also deduce its continuity with respect to Pompeiu-Hausdorff distance.

Proposition 16.

Let and be sequences in and let such that and in the Pompeiu-Hausdorff metric. Then, the following limit exists and

Proof.

For all we have

and

Then, and ; combining with inequality we have the existence of and the conclusion follows from property (8) of t-difference: and . ☐

Remark 6.

Considering the set of differences belonging to both and , we define the nonempty family

The elements satisfy the following five properties, with respect to the resolvability of equation “” with elements and :

G1a. , , such that , i.e., ;

G1b. , , such that , i.e., ;

G1c. , , such that , i.e., ;

G2. C has the inclusion-minimality property: no other exists with the properties G1a, G1b and G1c and .

G3. C has the magnitude-minimality property: no other exists with the properties G1a, G1b and G1c and .

The interpretation of the properties above is interesting: each set is a minimal set (in the sense of inclusion and magnitude) that allows obtaining all elements as for some pairs and all elements as for some pairs .

Remark 7.

As is seen in [12], a necessary and sufficient condition for the existence of gH-difference of multidimensional compact intervals (boxes) is that A contains a translate of B or B contains a translate of A; clearly, if exists for boxes, it is itself a box. It is interesting to observe that in general, the total difference of boxes is not a box. Consider, e.g., the two boxes as from Remark 2.7 in [35], and for which the gH-difference does not exist; it is easy to see that is a segment and not a box. On the other hand, both interval-valued gH-differences and exist (of different type). It is not difficult to prove that in general, for boxes and , the box where , , is the smallest box (in the sense of inclusion) such that . This suggests that for some applications, a t-difference can be defined with the requirement that it belongs to specific families of sets.

4. Computation of the New Difference

The final step of our proposal for a new difference of compact convex sets, is a way to determine or to approximate one of the elements of . First of all, observe that when H-difference exists (i.e., ) or gH-difference exists (i.e., or ), then the family has only one element. In other situations, there is no guarantee that contains only one element and the problem of determining one of them is important. It is also possible that is a singleton but gH-difference does not exist (see Example 1).

We can mention more that one possible approach:

(1) Chose any element ;

(2) Chose an element with minimal norm ;

(3) Chose an element such that for some , the quantity is minimal.

We have immediately a geometric interpretation of the generalized difference (as a family of sets) in terms of the family of the interval-valued functions . We can see that each is a sub-additive “envelope” of the interval-valued function . In particular, an homogeneous (so we can restrict its domain to the unit sphere of ) sub-additive envelope has a minimality property, similar to the property for the standard convex envelope.

Definition 15.

We say that a sub-additive homogeneous interval-valued function is a homogeneous sub-additive envelope of a homogeneous interval-valued function if and only if

(1) interval contains interval , for all ,

(2) there is no other with property (1) and with contained in for all

If J is sub-additive, then is its unique sub-additive envelope.

There always exists a sub-additive envelope of any homogeneous interval-valued function .

In general, the sub-additive envelope is not unique.

Proposition 17.

Let and consider the interval-valued function ; let be any continuous sub-additive envelope of the interval-valued function ; then, the compact convex set C defined by I is an element of , i.e., for some .

Proof.

Let for all . We have

the inclusion , in terms of support functions, is equivalent to and , i.e., to and and both are satisfied by the requirement that contains for all p; similarly, the inclusion is equivalent to and and both are satisfied. Finally, the inclusion-minimality of C is given by the second requirement for a sub-additive envelope. ☐

A computable solution, easy to implement for with small , is based on the following

Proposition 18.

Let and consider the difference family . Consider the set of nonnegative functions such that , for , is a support function (i.e., its homogeneous extension to is convex), and define the continuous functions

Then, the minimization problem

has a solution , and the compact convex set with support function is an element of the difference set .

Proof.

The feasible set of problem (P) is not empty, e.g., for is feasible and is the support function of the difference . For the same reason, problem (P) is bounded and an optimal solution exists by the continuity of the functional (or ). Consider that for all feasible functions we have that represents a distance between the support function and the function and problem (P) determines a continuous convex envelope of intervals (the corresponding dual support function at is ). The proof follows from Proposition 17. ☐

Definition 16.

Let ; the element corresponding to solution of problem (P) is called the generalized starred difference (-difference for short) of A and B, and will be denoted by . If the gH-difference (or H-difference) exists then (or ).

From a computational (and practical) point of view, we will determine an approximation of the -difference by solving problem (P) in a simplified form: the function to be determined is discretized on a finite number of points , , of the unit sphere ; correspondingly, the objective functional is approximated by and problem (P) becomes the following minimization

The -difference is then approximated by the compact convex set

It is immediate to see that is an element of ; when gH-difference (or H-difference) exists, then is an approximation of (or ).

Computing the Difference in

The conditions for to be points of a support function, become easy for compact convex sets in the plane ; if points are selected as with uniform , then the constraints (54) are linear equalities with respect to the and can be written (see [36] for details) as

where

The linear program (P) becomes the following (m equality constraints and m upper bound conditions on the variables )

Remark 8.

The minimization of in (P), in general, will not produce an element of ; to obtain an element of by solving (P), it is sufficient to add the equality constraint , i.e., the equivalent linear constraints

We present some examples, all produced by solving the linear programming problem (P) with (the choice for some k is motivated by the opportunity to have the same precision for the four quadrants of the plane).

We have tested the above procedure on several examples, many of them published in the literature (see [36] for additional examples).

We will show graphical representations giving the interval-valued functions , and the -difference . Computation of the support functions and solution of problem (P) is in general very simple; on a standard PC using Matlab it requires less than s (elapsed time) for the objective function and less than s for the objective .

A comparison with the directed difference is immediate; we remark that the difference based on directed sets (as proposed in [17,18,19]) do not satisfy in general the inclusions and ; essentially, it is based on appropriate visualization of the interval-valued function (and it coincides with our -difference only when itself is sub-additive). In all pictures below, we reproduce the set defined in Equation (36); in any case, .

In all the figures, the graphical portion at the top represents the interval-valued functions and ; remark that in any case we have with equality if and only if the gH-difference exists.

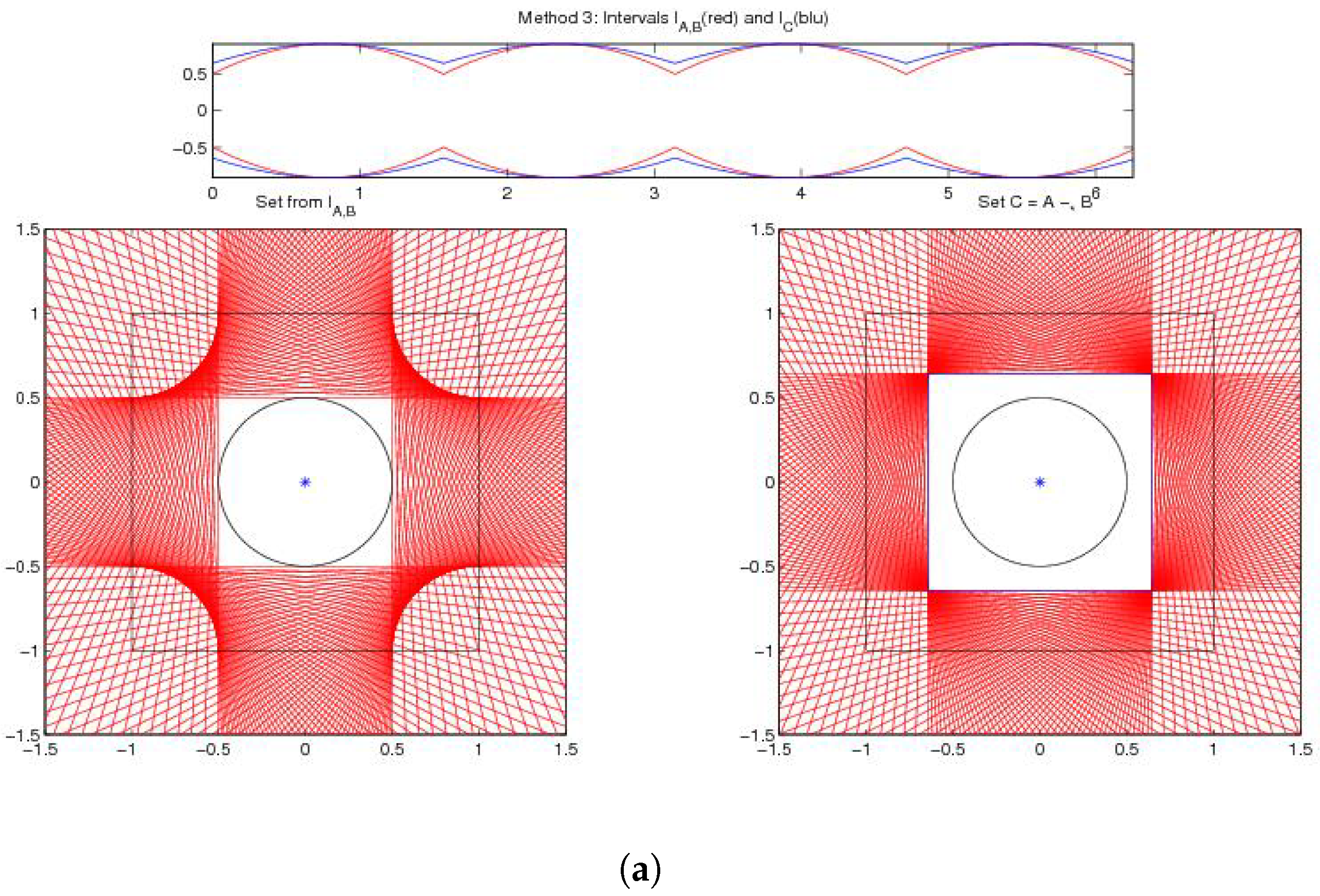

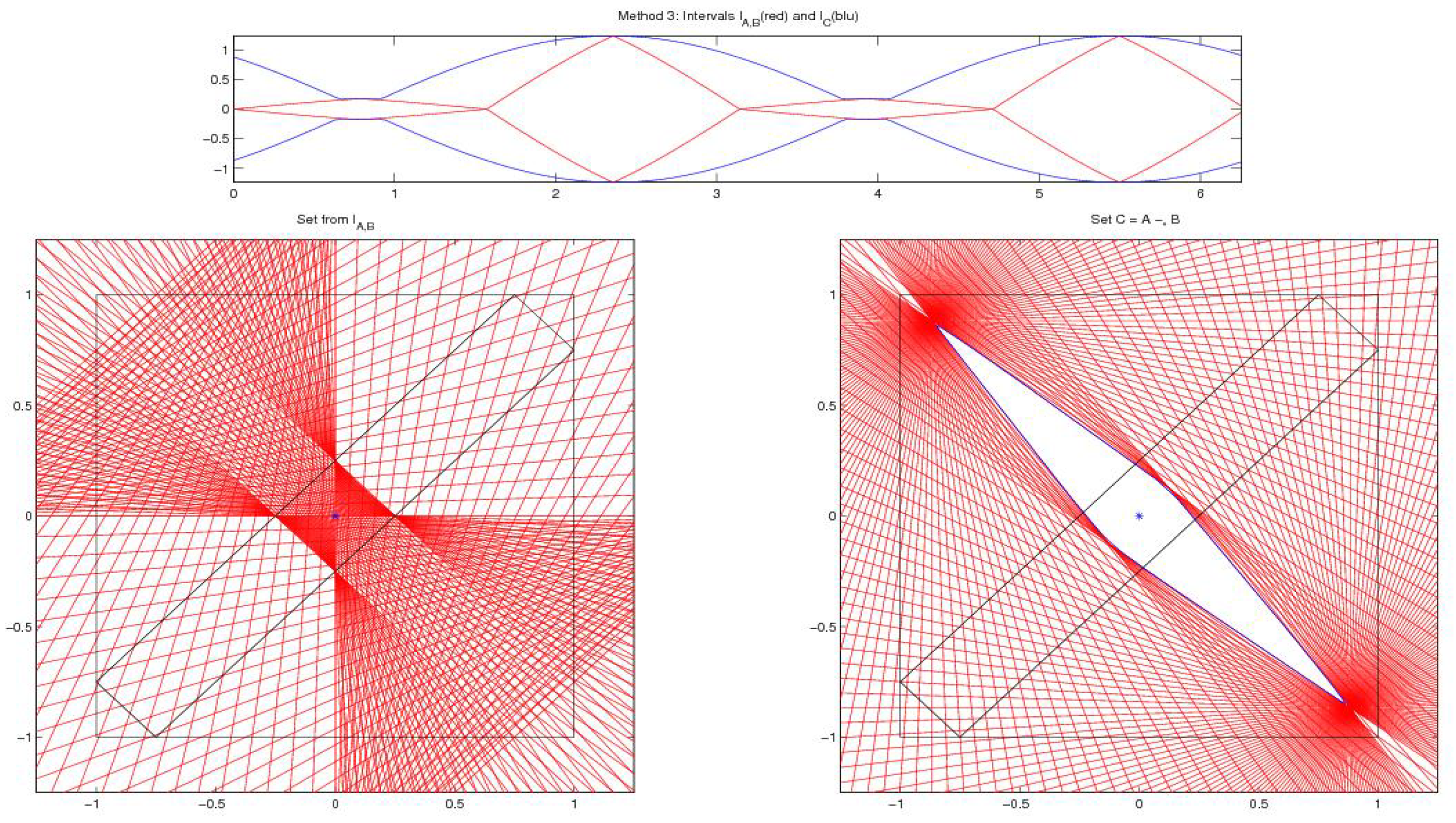

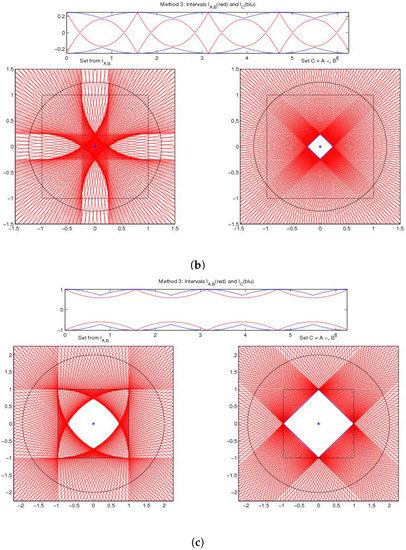

Example 1: This example is taken from [19]. The set A is the square and B is a circle with different values for the radius, . We consider the differences for three values of and , as in [19].

In the first case , the -difference is pictured on the right of Figure 1a; we obtain ; the geometric difference and the directed difference are well defined (not empty and proper, respectively) and pictured on the left of Figure 1a. Consider that and does not exist.

Figure 1.

Example 1. -difference for (a) top: , (b) middle: , (c) bottom: .

In the second case , the -difference is pictured on the right of Figure 1b; we obtain ; the geometric difference and set are empty, the directed difference is not proper and does not exist.

In the third case , the -difference is pictured on the right of Figure 1c; we obtain ; the geometric difference and the directed difference are well defined (not empty and proper, respectively) and pictured on the left of Figure 1c. Consider that and does not exist.

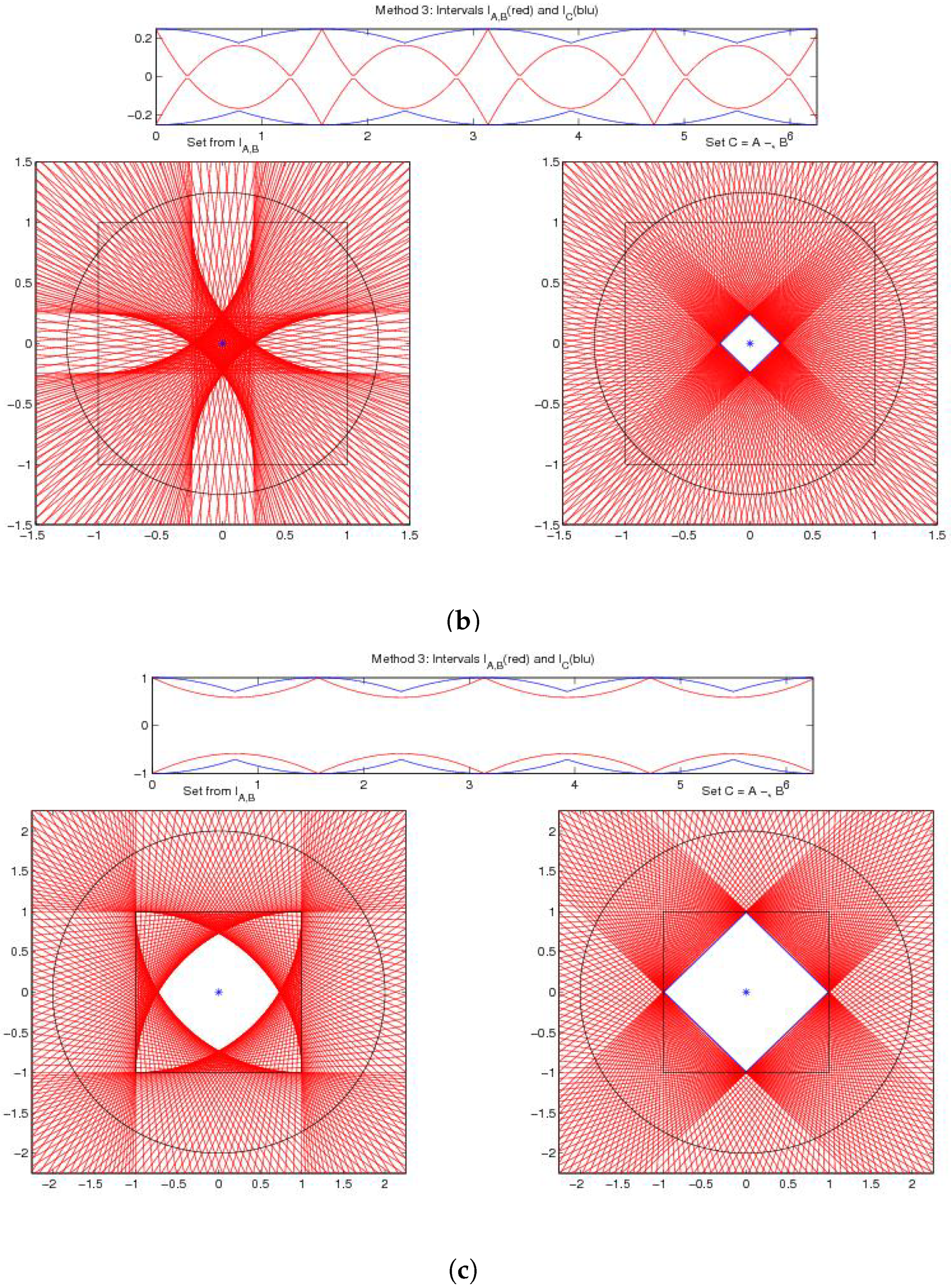

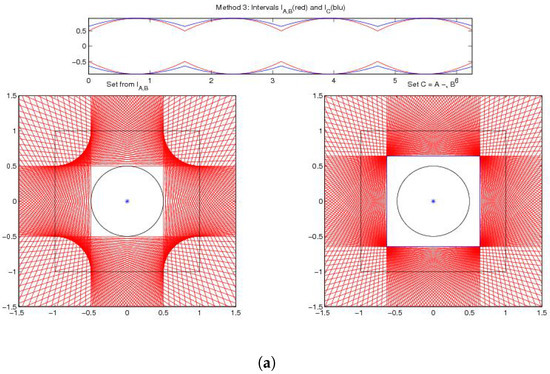

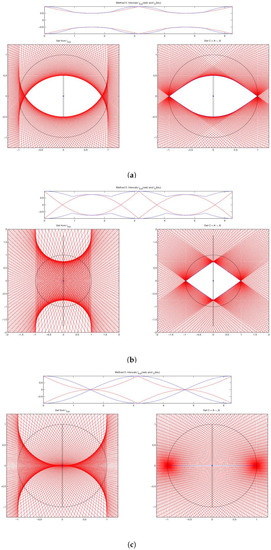

Example 2: This example is a modified version of the one given by Rubinov and Akhundov in [44]; is the unit circle and is a rectangle with a small base . In [44] the case is examined; we have chosen , to better visualize the construction; as in [44], the values are used.

In the first case and , the -difference is pictured on the right of Figure 2a; we obtain ; the geometric difference and the directed difference are well defined (not empty and proper, respectively) and pictured on the left of Figure 2a. Consider that and does not exist.

Figure 2.

Example 2. -difference for and (a) top: , (b) middle: , (c) bottom: .

In the second case and , the -difference is pictured on the right of Figure 2b; we obtain ; the geometric difference is empty, the directed difference is not proper and does not exist.

In the third case and , the -difference is pictured on the right of Figure 2c; also here we obtain ; the geometric difference is , the directed difference is not proper and does not exist.

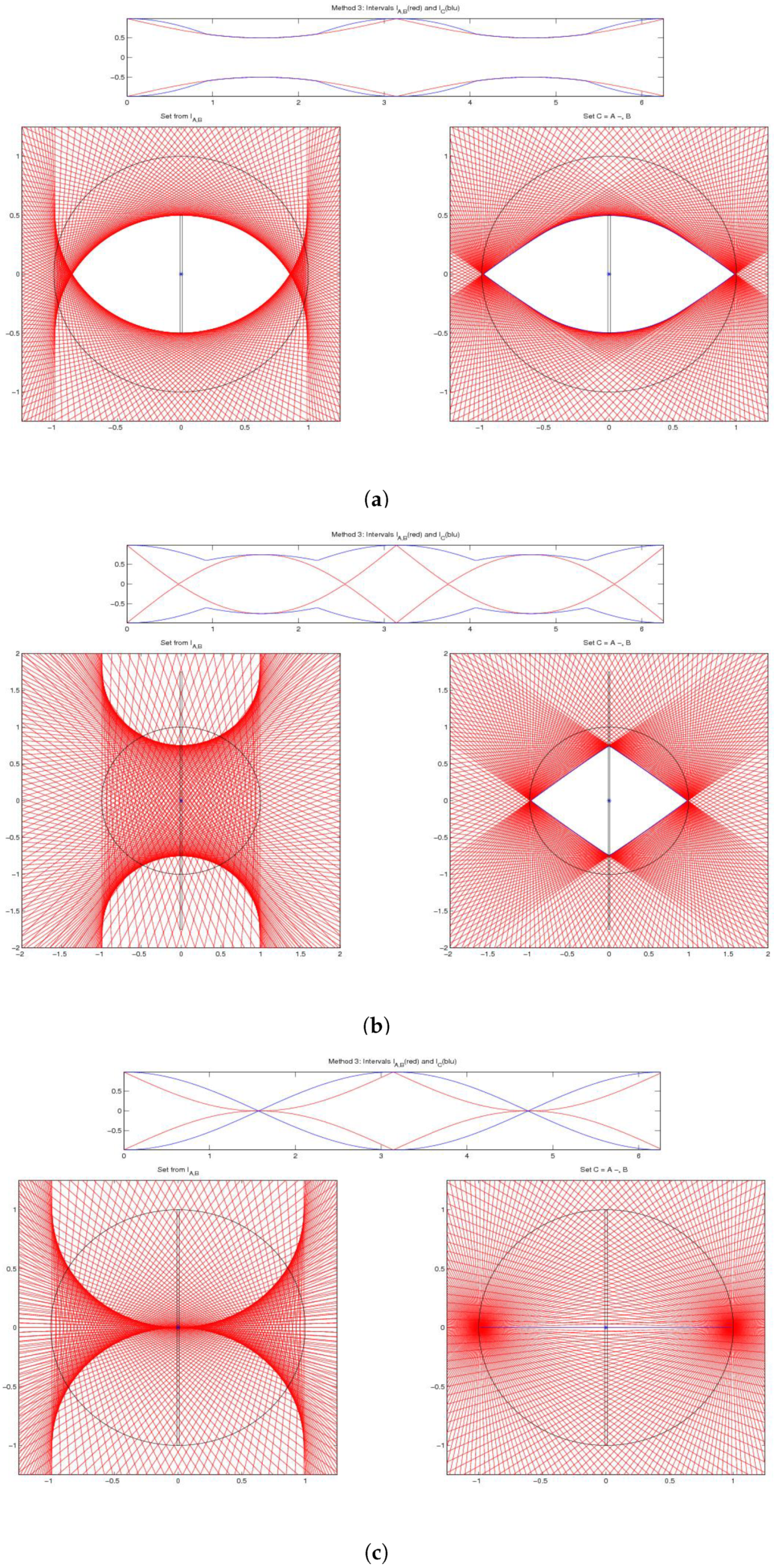

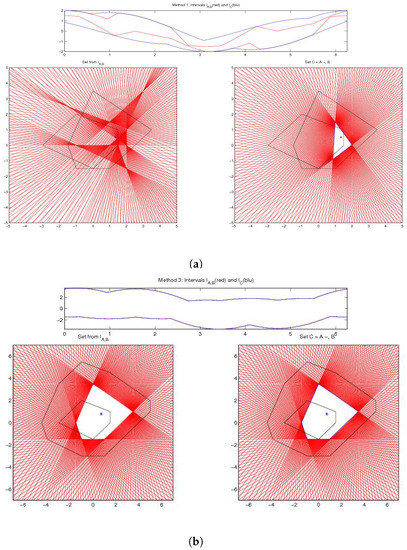

Example 3: This example works with polygons. Consider the two convex polygons

defined in terms of their vertices , , , , and , , , , . In the first case, we compute the difference for and . In the second case we use (the convex polygon obtained as the addition of the two polygons and ) and , so that B is a summand of A and , the classical Hukuhara difference, exists.

For the first case with and , the -difference is pictured on the right of Figure 3a; we obtain ; the geometric difference is empty, the directed difference is not proper and does not exist.

Figure 3.

Example 3. -difference for (a) top: , (b) bottom: .

In the second case with and , the -difference , the geometric difference and the (proper) directed difference exist and coincide, as pictured on the left and the right sides of Figure 3b; we obtain .

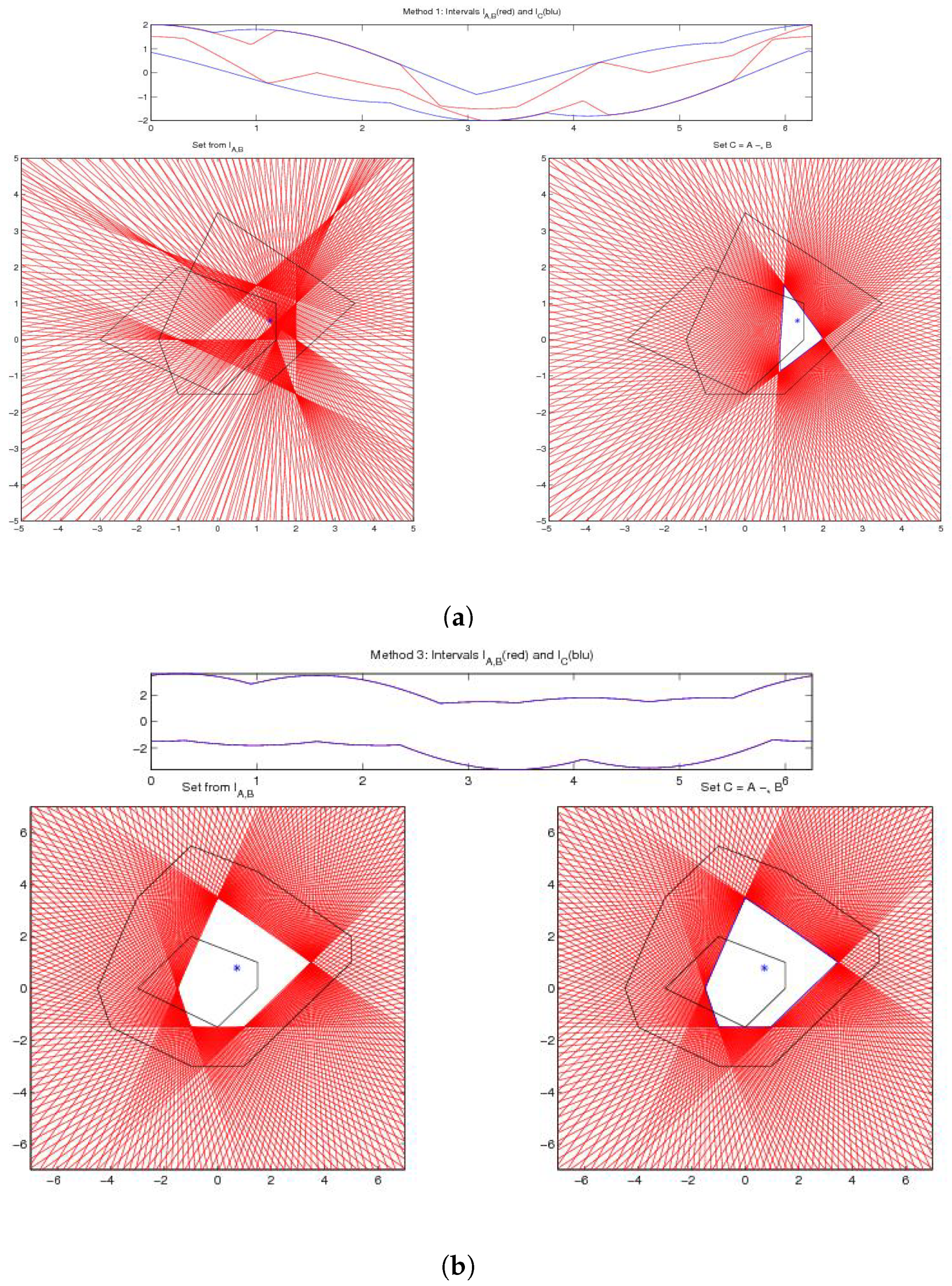

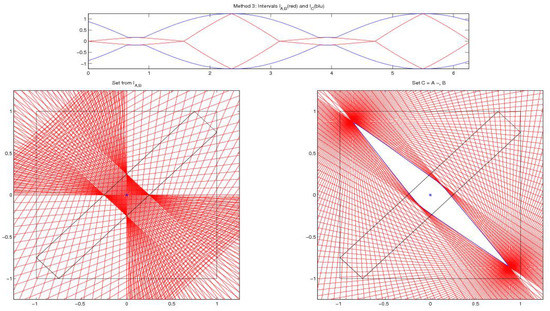

Example 4: In our last example is the unit square centered at the origin and B is an “inclined” rectangle formed around one of the diagonals of A and with four vertices , , , . In this case, the geometric difference is (only ) and the directed difference is not proper (left of Figure 4). We obtain (right of Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Example 4. -difference .

5. Extension to Convex Fuzzy Sets

A general fuzzy set over (the universe) is usually defined by its membership function and a fuzzy set u of is uniquely characterized by the pairs for each ; the value is the membership grade of x for a fuzzy set over (see [45,46] or [47] for the origins of Fuzzy Set Theory).

We will denote by the fuzzy sets and the corresponding membership functions, e.g., , will denote directly the membership grade of x, t.

The support of a fuzzy set u is the (crisp) subset of points of at which the membership grade is positive: , . For the level cut of u (or simply the ) is defined by and for (or ) by the closure of the support.

A particular class of fuzzy sets u is when the support and the are compact and convex set; equivalently, is quasi-concave and upper semi-continuous. We will also require that the membership function is normal, i.e., the core is compact and non-empty. Without ambiguity, 0 will denote the origin of or the crisp set

We will denote by the set of the fuzzy sets with the properties above (also called fuzzy quantities). The space is structured by an addition and a scalar multiplication, defined either by the level sets or, equivalently, by the Zadeh extension principle.

Let have membership functions and respectively. In the unidimensional case , we will denote by the compact intervals forming the and the fuzzy quantities will be called fuzzy numbers.

The addition and the scalar multiplication have level cuts

The H-difference exists if with ; the gH-difference for fuzzy numbers can be defined as follows ([12]):

Definition 17.

Given , the gH-difference is the fuzzy quantity , if it exists, such that

If and exist, ; if (i) and (ii) are satisfied simultaneously, then w is a crisp quantity. Also, .

An equivalent definition of can be obtained in terms of support functions in a way similar to Equation (15)

where for a fuzzy quantity u, the support functions are considered for each and defined to characterize the :

The gH-difference in the fuzzy context has been introduced in [12]; it is the fuzzy quantity with

where the gH-differences on the right, assuming they exist for all , are intended into by Equation (59).

In general, the fuzzy set defined by the union (61) is not convex; if a convex fuzzy set is required, then the compact sets are convexified (by convex hull), obtaining the convexified gH-difference

The fuzzy total t-difference and the fuzzy convexified total ct-difference can be defined in a similar way, in terms of the corresponding -cuts, for :

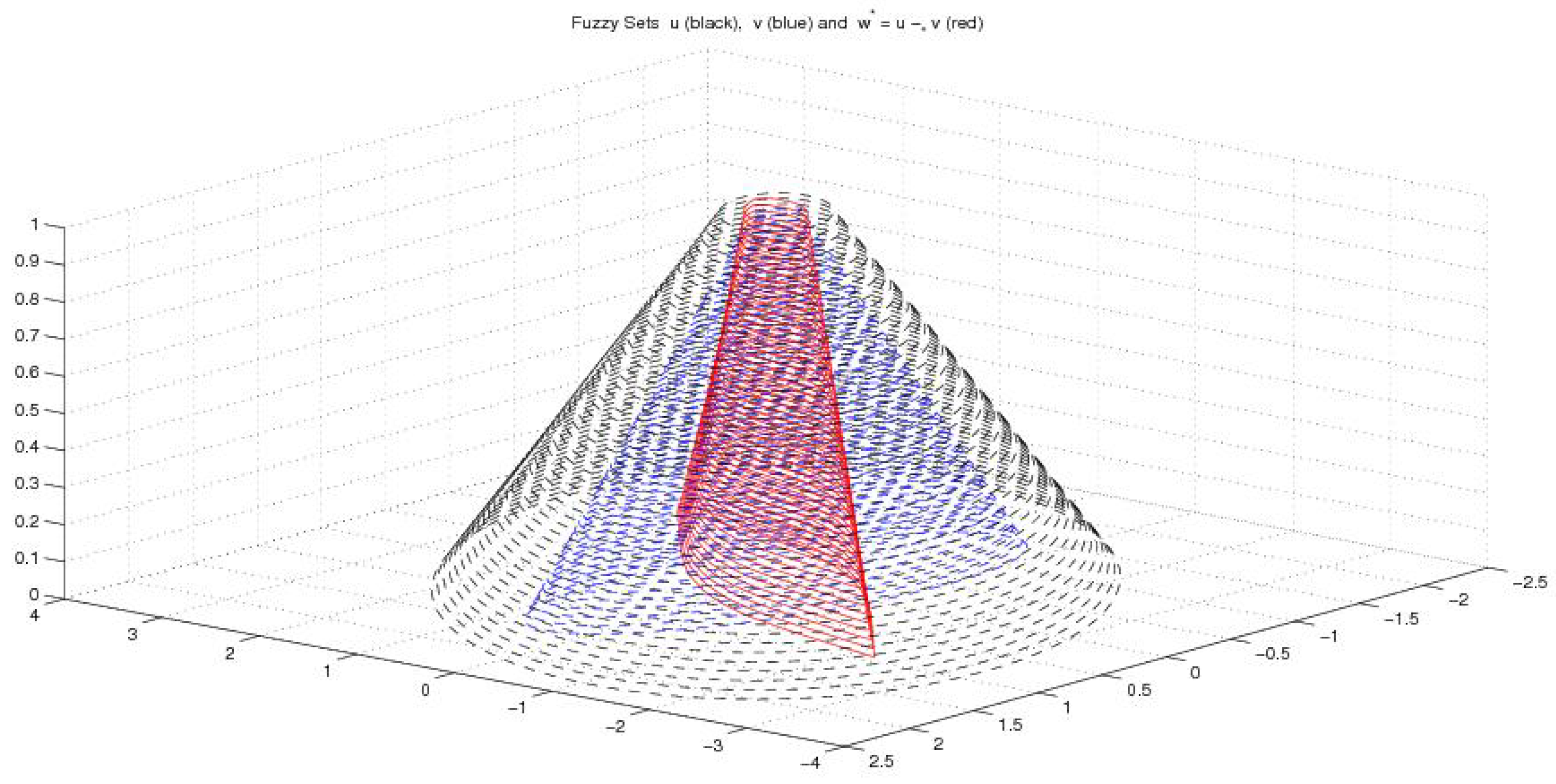

Fuzzy example 1: This example considers two convex (interacting) fuzzy sets with elliptic -cuts. To generate elliptic sets in we use the well-known property that given a positive definite matrix Q, the set

is convex and elliptic (centered at the origin) and its support function is

Starting with two elliptic sets U and V defined as in (64) by two positive definite matrices and , we construct the -cuts of u and v

where and are positive factors giving the supports , and the cores , of u and v, respectively. The used matrices are

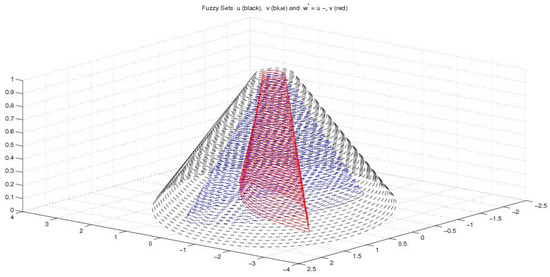

and, for all , the -cuts of u contain the -cuts of v. The ct-difference is pictured in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Fuzzy Example 1. Fuzzy sets u (black), v (blue) and fuzzy ct-difference (red).

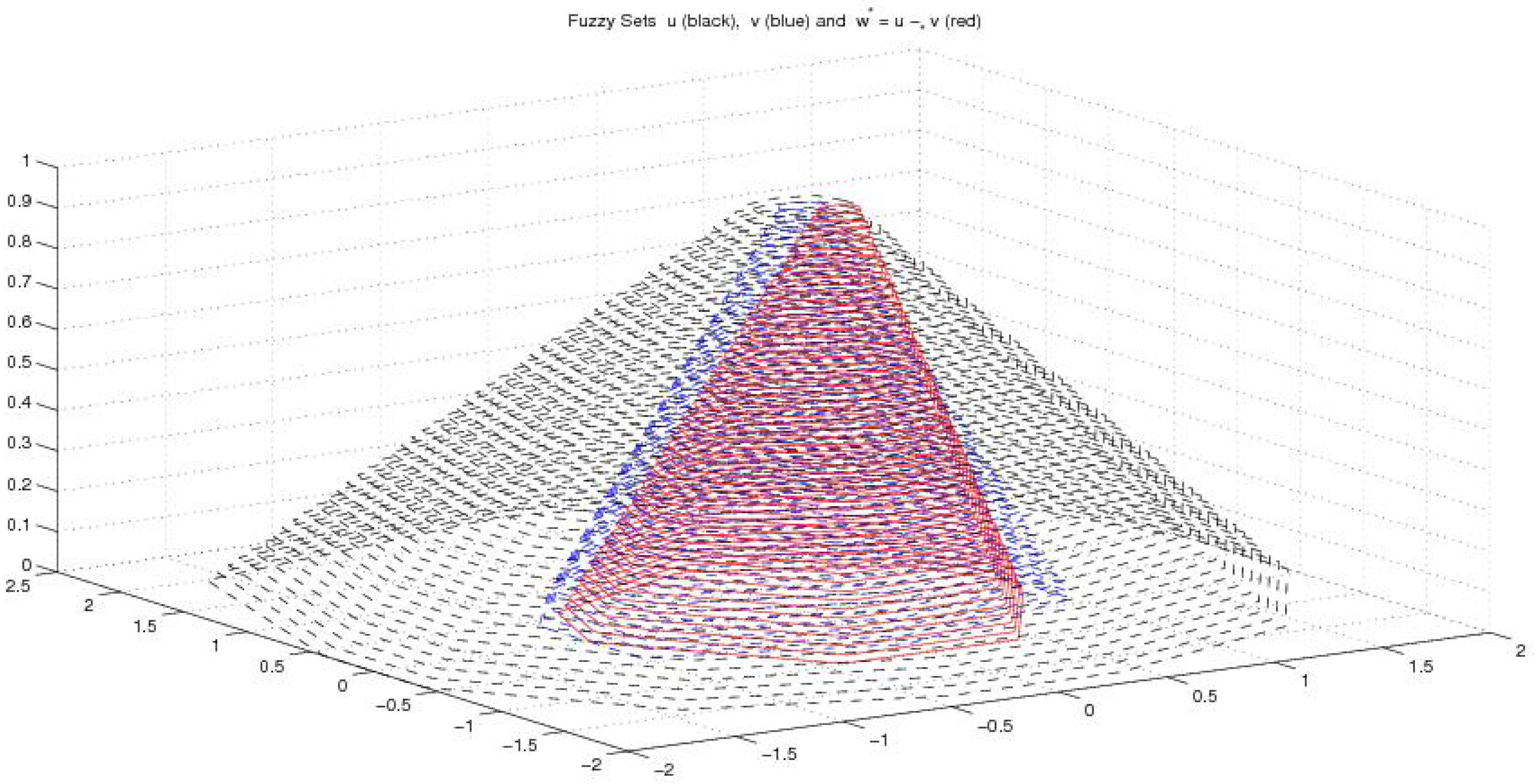

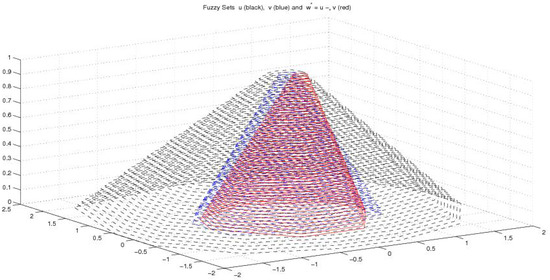

Fuzzy example 2: In this example, the -cuts of u and v are polygons

where U and V are polygons with the two sets of vertices:

for U—, , , , , , , , , , , and

for V—, , , , , , , .

The corresponding fuzzy ct-difference is pictured in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

Fuzzy Example 2. Fuzzy sets u (black), v (blue) and fuzzy ct-difference (red).

6. Conclusions

In this paper we propose a general setting to define the difference sets of multidimensional compact convex sets (and convex fuzzy sets with bounded support) in terms of convex sets (the classical Minkowski operation) such that and , which always exist. In order to overcome the possible non unicity of such sets C, we suggest to select the difference sets among the sets C above that satisfy some minimality conditions (see Section 3) that allows, additionally, to express the Pompeiu-Hausdorff distance in terms of the norm of the difference, i.e., , using the standard norm in .

Application of the difference set to the fuzzy case is obtained by the levelwise approach based on the property that the level cuts are compact convex and characterize convex fuzzy sets uniquely.

The range of possible applications of the proposed difference(s) is quite extended, following the intense research published in set-valued analysis ([48,49]), in variational analysis ([7,9,10,50]), in set-valued differential equations, among other fields, by using set difference to define differentiability.

Following the computational procedures (based on linear programming) for the difference of compact convex sets in , as presented in Section 4 and Section 5, additional work is in preparation for the n-dimensional case, , in particular for special classes of convex sets, e.g., compact convex polytopes, zonoids (Minkowski sums of multidimensional segments with , ) and similar. Eventually, this may allow obtaining easily computable approximations of the difference set.

Author Contributions

The manuscript is the result of a joint research by the authors; the authors contributed equally to this work.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Markov, S. A non-standard subtraction of intervals. Serdica 1977, 3, 359–370. [Google Scholar]

- Markov, S. Extended interval arithmetic. Compt. Rend. Acad. Bulg. Sci. 1977, 30, 1239–1242. [Google Scholar]

- Markov, S. Calculus for interval functions of a real variable. Computing 1979, 22, 325–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markov, S. On the Algebra of Intervals and Convex Bodies. J. Univers. Comput. Sci. 1998, 4, 34–47. [Google Scholar]

- Hukuhara, M. Integration des applications measurables dont la valeur est un compact convexe. Funkcialaj Ekvacioj 1967, 10, 205–223. [Google Scholar]

- Pontryagin, L.S. On linear differential games, II. Sov. Math. Dokl. 1967, 8, 910–912. [Google Scholar]

- Demyanov, V.F.; Rubinov, A.M. Constructive Nonsmooth Analysis; Peter Lang: Frankfurt, Germany, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, Y. Demyanov difference of two sets and optimality conditions of Lagrange multiplier type for constrained quasidifferentiable optimization. J. Optim. Theory Appl. 2000, 104, 377–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mordukhovich, B.S. Variational Analysis and Generalized Differentiation I: Basic Theory; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Mordukhovich, B.S. Variational Analysis and Generalized Differentiation II: Applications; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Penot, J.-P. On the minimization of difference functions. J. Glob. Optim. 1998, 12, 373–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stefanini, L. A generalization of Hukuhara-difference and division for interval and fuzzy arithmetic. Fuzzy Sets Syst. 2010, 161, 1564–1584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bede, B. Mathematics of Fuzzy Sets and Fuzzy Logic; Studies in Fuzziness and Soft Computing Series n. 295; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Bede, B.; Stefanini, L. Generalized differentiability of fuzzy valued functions. Fuzzy Sets Syst. 2013, 230, 119–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stefanini, L.; Bede, B. Generalized fuzzy differentiability with LU-parametric representation. Fuzzy Sets Syst. 2014, 257, 184–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stefanini, L.; Arana-Jimenez, M. Karush-Kuhn-Tucker conditions for interval and fuzzy optimization in several variables under total and directional generalized differentiability. Fuzzy Sets Syst. 2019, 362, 1–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baier, R.; Farkhi, E. Differences of Convex Compact Sets in the Space of Directed Sets, Part I: The Space of Directed Sets. Set-Valued Anal. 2001, 9, 217–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baier, R.; Farkhi, E. Differences of Convex Compact Sets in the Space of Directed Sets, Part II: Visualization of Directed Sets. Set-Valued Anal. 2001, 9, 247–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baier, R.; Farkhi, E.; Roshchina, V. The directed and Rubinov subdifferentials of quasidifferentiable functions, Part I: Definition and examples. Nonlinear Anal. 2012, 75, 1074–1088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baier, R.; Farkhi, E.; Roshchina, V. The directed and Rubinov subdifferentials of quasidifferentiable functions, Part II: Calculus. Nonlinear Anal. 2012, 75, 1058–1073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pallaschke, D.; Urbanski, R. Pairs of Compact Convex Sets, Fractional Arithmetic with Convex Sets; Kluwer Academic Publishers: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Banks, H.T.; Jacobs, M.Q. A differential calculus for multifunctions. J. Math. Anal. Appl. 1970, 29, 246–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radstrom, H. An embedding theorem for spaces of convex sets. Proc. Am. Math. Soc. 1952, 3, 165–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bede, B.; Gal, S.G. Generalizations of the differentiability of fuzzy number valued functions with applications to fuzzy differential equations. Fuzzy Sets Syst. 2005, 151, 581–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bede, B.; Stefanini, L. Solution of fuzzy differential equations with generalized differentiability using LU-parametric representation. In Proceedings of the EUSFLAT/LFA 2011 Conference, Aix-Les-Bains, France, 18-22 July 2011; Galichet, S., Montero, J., Mauris, G., Eds.; Atlantis Press: Paris, France, 2011; Volume 1, pp. 785–790. [Google Scholar]

- Buckley, J.J.; Qu, Y. Solving linear and quadratic fuzzy equations. Fuzzy Sets Syst. 1990, 38, 43–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buckley, J.J.; Qu, Y. Solving fuzzy equations: A new solution concept. Fuzzy Sets Syst. 1991, 39, 291–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buckley, J.J.; Qu, Y. Solving systems of linear fuzzy equations. Fuzzy Sets Syst. 1991, 43, 33–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buckley, J.J. Solving fuzzy equations. Fuzzy Sets Sys. 1992, 50, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubois, D.; Prade, H. Fuzzy set-theoretic differences and inclusions and their use in the analysis of fuzzy equations. Control Cybern. 1984, 13, 129–146. [Google Scholar]

- Laksmikantham, V.; Mohapatra, R.N. Theory of Fuzzy Differential Equations and Inclusions; Taylor and Francis: New York, NY, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Malinowski, M.T. Bipartite Fuzzy Stochastic Differential Equations with Global Lipschitz Condition. Math. Probl. Eng. 2016, 2016, 3830529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stefanini, L.; Bede, B. Generalized Hukuhara differentiability of interval valued functions and interval differential equations. Nonlinear Anal. 2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stefanini, L.; Bede, B. Some Notes on Generalized Hukuhara Differentiability of Interval Valued Functions and Interval Differential Equations; EMS Working Paper Series; Faculty of Economics: Urbino, Italy, 2012; Available online: http://ideas.repec.org/f/pst233.html (accessed on 16 March 2019).

- Wang, C.; Agarwal, R.P.; O’Regan, D. Calculus of fuzzy vector-valued functions and almost periodic fuzzy vector-valued functions on time scales. Fuzzy Sets Syst. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stefanini, L. Computational Procedures for the Difference of Compact Convex Sets; EMS Working Paper Series; Faculty of Economics: Urbino, Italy, in preparation.

- Diamond, P.; Kloeden, P. Metric Spaces of Fuzzy Sets; World Scientific: Singapore, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Diamond, P.; Koerner, R. Extended fuzzy linear models and least squares estimates. Comput. Math. Appl. 1997, 33, 15–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diamond, P.; Kloeden, P.; Rubinov, A.; Vladimirov, A. Comparative properties of three metrics in the space of compact convex sets. Set-Valued Anal. 1997, 5, 267–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, R. Convex Bodies: The Brunn-Minkowski Theory; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Markov, S. On the algebraic properties of convex bodies and some applications. J. Convex Anal. 2000, 7, 129–166. [Google Scholar]

- Stefanini, L. On the generalized LU-fuzzy derivative and fuzzy differential equations. In Proceedings of the FUZZIEEE 2007 Conference, London, UK, 23–26 July 2007; Available online: http://ideas.repec.org/f/pst233.html (accessed on 16 March 2019). [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Legaz, J.-E.; Penot, J.-P. Regularization by erasement. Math. Scand. 2006, 98, 97–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Rubinov, A.M.; Akhundov, I.S. Difference of compact sets in the sense of Demyanov and its application to nonsmooth analysis. Optimization 1992, 23, 179–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zadeh, L.A. Fuzzy sets. Inf. Control 1965, 8, 338–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zadeh, L.A. Concept of a linguistic variable and its application to approximate reasoning, I. Inf. Sci. 1975, 8, 199–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zadeh, L.A. Fuzzy sets as a basis for a theory of possibility. Fuzzy Sets Syst. 1978, 1, 3–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aubin, J.P.; Frankowska, H. Set-Valued Analysis; Birkhauser-Verlag: Boston, MA, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Rockafellar, R.T. Convex Analysis; Princeton Univ. Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Rockafellar, R.T.; Wets, R.J.-B. Variational Analysis; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 1998. [Google Scholar]

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).