Abstract

The original Bohr-Sommerfeld theory of quantization did not give operators of transitions between quantum quantum states. This paper derives these operators, using the first principles of geometric quantization.

1. Introduction

Even though the Bohr–Sommerfeld theory was very successful in predicting some physical results, it was never accepted by physicists as a valid quantum theory in the same class as the Schrödinger theory or the Bargmann–Fock theory. The reason for this was that the original Bohr–Sommerfeld theory did not provide operators of transition between quantum states. The need for such operators in the Bohr–Sommerfeld quantization was already pointed out by Heisenberg [1]. The aim of this paper is to derive operators of transition between quantum states in the Bohr–Sommerfeld theory, which we call shifting operators, from the first principles of geometric quantization.

The first step of geometric quantization of a symplectic manifold is called prequantization. It consists of the construction of a complex line bundle with connection whose curvature form satisfies a prequantization condition relating it to the symplectic form . A comprehensive study of prequantization, from the point of view of representation theory, was given by Kostant in [2]. The work of Souriau [3] was aimed at quantization of physical systems, and studied a circle bundle over phase space. In Souriau’s work, the prequantization condition explicitly involved Planck’s constant . In [4], Blattner combined the approaches of Kostant and Souriau by using the complex line bundle with the prequantization condition involving Planck’s constant. Since then, geometric quantization has been an effective tool in quantum theory.

We find it convenient to deal with connection and curvature of complex line bundles using the theory of principal and associated bundles [5]. In this framework, the prequantization condition reads

where is the connection 1-form on the principal -bundle associated to the complex line bundle , and is the multiplicative group of nonzero complex numbers.

The aim of prequantization is to construct a representation of the Poisson algebra of on the space of sections of the line bundle L. Each Hamiltonian vector field on P lifts to a unique -invariant vector field on that preserves the principal connection on . If the vector field is complete, then it generates a 1-parameter group of symplectomorphisms of . Then, the vector field is complete and it generates a 1-parameter group of connection preserving diffeomorphisms of the bundle , called quantomorphisms, which cover the 1-parameter group . The term quantomorphism was introduced by Souriau [3] in the context of -principal bundles and discussed in detail in his book [6]. The construction discussed here follows [7], where the term quantomorphism was not used. In this case, and are 1-parameter groups of diffeomorphisms of P and , respectively. We refer to and as flows of and . Since L is an associated bundle of , the action , induces an action which gives rise to an action on smooth sections of L by push forwards, . Although may not be defined for all sections and all t, its derivative at is defined for all smooth sections. The prequantization operator

where is Planck’s constant divided by , is a symmetric operator on the Hilbert space of square integrable sections of L. The operator is self adjoint if is complete.

The whole analysis of prequantization is concerned with global Hamiltonian vector fields. Since every vector field on that preserves the symplectic form is locally Hamiltonian, it is of interest to understand how much of prequantization can be extended to this case. In particular, we are interested in the case where the locally Hamiltonian vector field is the vector field of the integer angle variable that is defined up to an additive term where For a globally Hamiltonian vector field ,

where is the horizontal transport of section by parameter t along integral curves of Replacing f by a multivalued function , defined up to an additive n, yields the multivalued expression

We observe that, for , Equation (3) gives a single valued expression

The shifting operator

is an operator on which shifts the support of by along the integral curve of . If the vector field is complete, then for every .

Our results provide an answer to Heisenberg’s criticism that in Bohr–Sommerfeld theory there are not enough operators to describe transitions between quantum states [1].

Superficially, the shifting operator , see Equation (5), appears to be a quantization of an angle . It depends on and has the factor considered by Dirac [8]. However, the factor , describing the parallel translation by along integral curves of makes it nonlocal in the phase space. Therefore, cannot satisfy local commutation relations with any local quantum variable that is described by a differential operator. Hence, it cannot be the canonical conjugate of the corresponding action operator, or any other operator, which is local in the phase space.

In our earlier papers [9,10,11,12], we followed an algebraic analysis, similar to that used by Dirac [8], supplemented by heuristic guesses about the behaviour of the shifting operators at the points of singularity of the polarization. In particular, we assumed that vanishes on the states concentrated on a set of limit points of as In the present paper, we derive shifting operators in the framework of geometric quantization, and extend our result to cases with a variable rank polarization.

The second stage in geometric quantization consists of the choice of a polarization, which is an involutive complex Lagrangian distribution F on the phase space. Suppose that P is the cotangent bundle space of the configuration space. In this case, the choice of F containing the vertical directions, leads the quantum mechanics of Schrödinger. If F leads to complex analytic structure on P, we have the Bargmann–Fock theory. If F is spanned by the Hamiltonian vector fields of a completely integrable system, we have Bohr–Sommerfeld theory. Each of these theories have specific structure, which is helpful in formulation and solving problems. In the following, we restrict our investigation to the Bohr–Sommerfeld theory in order to emphasize its membership in the class of quantum theories corresponding to different polarization.

A common problem in arising in quantum theories is occurrence of singularities. Usually, one studies the geometric structure of the theory in the language of differential geometry of smooth manifolds, and then investigates the structure of singularities separately. The theory of differential spaces, introduced by Sikorski [13,14], is a powerful tool in the study of the geometry of spaces with singularities [15]. The main singularity encountered here corresponds to the fact that the polarization F spanned by the Hamiltonian vector fields of a completely integrable system does not have constant rank. This singularity is so well known that we do not have to use the language of differential spaces to get results. It should be noted that the results in [9,11] rely on the theory of differential spaces.

In conclusion, it should be mentioned that the scientists, who used visual presentation of the Bohr–Sommerfeld spectra in terms of dots on the space of the action variables, are familiar with handling shifting operators. The line segments joining two dots corresponding to quantum states represent the shifting operators between these states.

To make the paper more accessible to the reader, we have provided an introductory section with a comprehensive review of geometric quantization. Experts may omit this section and proceed directly to the next section on Bohr–Sommerfeld theory.

2. Elements of Geometric Quantization

Let be a symplectic manifold. Geometric quantization can be divided into three steps: prequantization, polarization, and unitarization.

2.1. Principal Line Bundles with a Connection

We begin with a brief review of connections on complex line bundles.

Let denote the multiplicative group of nonzero complex numbers. Its Lie algebra is isomorphic to the abelian Lie algebra of complex numbers. Different choices of the isomorphism lead to different factors in various expressions. Here, to each we associate the 1-parameter subgroup of . In other words, we take

The prequantization structure for consists of a principal bundle and a -valued -invariant connection 1-form satisfying

where h is Planck’s constant. The prequantization condition requires that the cohomology class is integral, that is, it lies in , otherwise the principal bundle would not exist.

Let be the vector field on generating the action of on . In other words, the 1-parameter group of diffeomorphisms of generated by is

The connection 1-form is normalized by the requirement

For each , the vector field, spans the vertical distribution tangent to the fibers of . The horizontal distribution on is the kernel of the connection 1-form , that is,

The vertical and horizontal distributions of give rise to the direct sum , which is used to decompose any vector field Z on into its vertical and horizontal components, . Here, the vertical component has range in and the horizontal component has range in .

If X is a vector field on P, the unique horizontal vector field on , which is -related to X, is called the horizontal lift of X and is denoted by . In other words, has range in the horizontal distribution and satisfies

Claim 1.

A vector field Z on is invariant under the action of on if and only if the horizontal component of Z is the horizontal lift of its projection X to P, that is, and there is a smooth function such that on .

Proof.

Since the direct sum is invariant under the action on , it follows that the vector field Z is invariant under the action of if and only if and are -invariant. However, is invariant if for some vector field X on P, that is, . However, this holds by definition. On the other hand, the vertical distribution is spanned by the vector fields for . Hence, is -invariant if and only if for every fiber the restriction of to coincides with the restriction of to for some , that is, there is a smooth complex valued function on P such that . □

Let U be an open subset of P. A local smooth section of the bundle gives rise to a diffeomorphism

where is the unique complex number such that . In the general theory of principal bundles the structure group of the principal bundle acts on the right. In the theory of principal bundles, elements of are considered to be one-dimensional frames, which are usually written on the right, see [2]. The diffeomorphism is called a trivialization of . It intertwines the action of on the principal bundle with the right action of on , given by multiplication in . If a local section of is nowhere zero, then it determines a trivialization . Conversely, a local smooth section such that is a trivialization of may be considered as a local nowhere zero section of L.

In particular, for every , which is identified with the Lie algebra of , Equation (7) gives . Differentiating with respect to t and then setting gives

For every smooth complex valued function , consider the vertical vector field such that for every . The vector field is complete and the 1-parameter group of diffeomorphisms it generates is

For every smooth section of the bundle , we have so that

Let X be a vector field on P and let be its horizontal lift to . The local 1-parameter group of local diffeomorphisms of generated by commutes with the action of on . For every , is called parallel transport of along the integral curve of X starting at . For every the map sends the fiber to the fiber .

There are several equivalent definitions of covariant derivative of a smooth section of the bundle in the direction of a vector field X on P. We use the following one. The covariant derivative of the smooth section of the bundle in the direction X is

Claim 2.

The covariant derivative of a smooth local section of the bundle in the direction X is given by

2.2. Associated Line Bundles

The complex line bundle associated to the principal bundle is defined in terms of the action of on given by

Since the action is free and proper, its orbit space is a smooth manifold. A point is the orbit through , namely,

The left action of on gives rise to the left action

which is well defined because for every , every a, and every . The projection map induces the projection map

Claim 3.

A local smooth section of the complex line bundle corresponds to a unique mapping such that for every and every

which is -equivariant, that is, .

Proof.

Given there exists such that . Since the action of on is free and transitive, it follows that the orbit is the graph of a smooth function from to , which we denote by . In particular, so that . As p varies over U we get a map

which satisfies Equation (20). For every , Equations (18) and (20) imply that

Hence, . Thus, the function is -equivariant. □

If is a local smooth section of the bundle , then for every we have or suppressing the argument p. The function is the coordinate representation of the section in terms of the trivialization .

Let Z be a -invariant vector field on . Then, Z is -related to a vector field X on P, that is, . We denote by and the local 1-parameter groups of local diffeomorphisms of P and generated by X and Z, respectively. Because the vector fields X and Z are -related, we obtain . In other words, the flow of Z covers the flow of X. The local group of automorphisms of the principal bundle act on the associated line bundle L by

which holds for all for which is defined.

Lemma 1.

The map is a local 1-parameter group of local automorphisms of the line bundle L, which covers the local 1-parameter group of the vector field X on P.

Proof.

We compute. For we have

Hence, is a local 1-parameter group of local diffeomorphisms. Moreover,

while

This shows that covers . Finally, for every and every

since Z is a -invariant vector field on . Therefore,

This shows that is a local group of automorphisms of the line bundle . □

If , then is parallel transport of along the integral curve of X starting at . Similarly, if , then

is parallel transport of along the integral curve of X starting at p. The covariant derivative of a section of the bundle in the direction of the vector field X on P is

Since maps onto , Equations (22) and (23) are consistent with the definitions in [5].

Theorem 1.

Let σ be a smooth section of the complex line bundle and let X be a vector field on P. For every

Here, is the Lie derivative with respect to the vector field X.

2.3. Prequantization

Let be the complex line bundle associated to the principal bundle . The space of smooth sections of is the representation space of prequantization. Since , we may identify with the complement of the zero section in L. With this identification, if is a local smooth section of , which is nowhere vanishing, then it is a section of the bundle .

Theorem 2.

A -invariant vector field Z on preserves the connection 1-form β, on if and only if there is a function such that

where is Planck’s constant.

Proof.

The vector field Z on preserves the connection 1-form, that is, , which is equivalent to

Since , it follows that . The -invariance of Z and imply the -invariance of . Hence, pushes forward to a function . Thus, the right hand side of Equation (27) reads

By definition , for every . This implies

Thus, the left hand side of Equation (27) reads

The quantization condition (7) together with (28) and (29) allow us to rewrite Equation (27) in the form

Equation (30) shows that X is the Hamiltonian vector field of the smooth function

on P. We write . This implies that

We still have to determine the vertical component of the vector field Z. For each there is a such that . Since is tangent to the fibers of the principal bundle , the element c of depends only on . Therefore,

by Equation (31). In other words, for every point we have , where . Thus, we have shown that

Reversing the steps in the above argument proves the converse. □

To each , we associate a prequantization operator

where is the action of on L, see (22). Note that the definition of covariant derivative in Equation (23) is defined in terms of the pull back of the section by , while the prequantization operator in (34) is defined using the push forward of by .

Theorem 3.

For every and each

Proof.

Since the horizontal distribution on is -invariant and the vector field generates multiplication on each fiber of by , it follows that . Since f is constant along integral curves of ,

and

Since , Equation (23) gives

Since , where is the identity map on P, it follows that

Let be a smooth local section of , then . Thus, for every

since for every , and . It follows that

Therefore,

Since

Equations (37), (38) and (41) imply Equation (35). □

A Hermitian scalar product on the fibers of L that is invariant under parallel transport gives rise to a Hermitian scalar product on the space of smooth sections of L. Since the dimension of is , the scalar product of the smooth sections and of L is

The completion of the space of smooth sections of L with compact support with respect to the norm is the Hilbert space of the prequantization representation.

Claim 4.

The prequantization operator is a symmetric operator on the Hilbert space of square integrable sections of the line bundle and satisfies Dirac’s quantization commutation relations

for every f, . Moreover, the operator is self adjoint if the vector field on is complete.

Proof.

We only verify that the commutation relations (43) hold. Let f, and let . We compute.

The quantization condition

yields

However, . Thus, . Since , it follows that

Consequently, . Thus,

□

2.4. Polarization

Prequantization is only the first step of geometric quantization. The prequantization operators do not satisfy Heisenberg’s uncertainty relations. In the case of Lie groups, the prequantization representation fails to be irreducible. These apparently unrelated shortcomings lead to the next step of geometric quantization: the introduction of a polarization.

A complex distribution on a symplectic manifold is Lagrangian if for every , the restriction of the symplectic form to the subspace vanishes identically, and . If F is a complex distribution on P, let be its complex conjugate. Let

A polarization of is an involutive complex Lagrangian distribution F on P such that D and E are involutive distributions on P. Let be the space of smooth complex valued functions of P that are constant along F, that is,

The polarization F is strongly admissible if the spaces and of integral manifolds of D and E, respectively, are smooth manifolds and the natural projection is a submersion. A strongly admissible polarization F is locally spanned by Hamiltonian vector fields of functions in . A polarization F is positive if for every . A positive polarization F is semi-definite if for implies that .

Let F be a strongly admissible polarization on . The space of smooth sections of L that are covariantly constant along F is the quantum space of states corresponding to the polarization F.

The space of smooth functions on P, whose Hamiltonian vector field preserves the polarization F, is a Poisson subalgebra of . Quantization in terms of the polarization F leads to quantization map , which is the restriction of the prequantization map

to the domain and the codomain . In other words,

Quantization in terms of positive strongly admissible polarizations such that lead to unitary representations. For other types of polarizations, unitarity may require additional structure.

3. Bohr–Sommerfeld Theory

3.1. Historical Background

Consider the cotangent bundle of a manifold Q. Let be the cotangent bundle projection map. The Liouville 1-form on is defined as follows. For each , and ,

The exterior derivative of is the canonical symplectic form on .

Let . A Hamiltonian system on with Hamiltonian is completely integrable if there exists a collection of functions , which are integrals of , that is, for , such that for i, . Assume that the functions are independent on a dense open subset of . For each , let be the orbit of the family of Hamiltonian vector fields passing through p. This orbit is the largest connected immersed submanifold in with tangent space equal to . The integral curve of starting at p is contained in . Hence, knowledge of the family of orbits provides information on the evolution of the Hamiltonian system with Hamiltonian .

Bohr–Sommerfeld theory, see [16,17], asserts that the quantum states of the completely integrable system are concentrated on the orbits , which satisfy the

Bohr–Sommerfeld Condition:For every closed loop , there exists an integer n such that

where h is Planck’s constant.

This theory applied to the bounded states of the relativistic hydrogen atom yields results that agree exactly with the experimental data [17]. Attempts to apply Bohr–Sommerfeld theory to the helium atom, which is not completely integrable, failed to provide useful results. In his 1925 paper [1], Heisenberg criticized Bohr–Sommerfeld theory for not providing transition operators between different states. At present, the Bohr–Sommerfeld theory is remembered by physicists only for its agreement with the quasi-classical limit of Schrödinger theory. Quantum chemists have never stopped using it to describe the spectra of molecules.

3.2. Geometric Quantization in a Toric Polarization

To interpret Bohr–Sommerfeld theory in terms of geometric quantization, we consider a set consisting of points where are linearly independent and the orbit of the family of Hamiltonian vector fields on is diffeomorphic to the k torus . We assume that P is a -dimensional smooth manifold and that the set is a quotient manifold of P with smooth projection map . This implies that the symplectic form on restricts to a symplectic form on P, which we denote by . Let D be the distribution on P spanned by the Hamiltonian vector fields . Since for i, , it follows that D is an involutive Lagrangian distribution on . Moreover, is a strongly admissible polarization of .

Since the symplectic form on is exact, we may choose a trivial prequantization line bundle

with connection 1-form . Let be the restriction of to P and let be the 1-form on P, which is the restriction of to P, that is, . Then, is a principal bundle over P with projection map

and connection 1-form . The complex line bundle

associated to the principal bundle is also trivial. Prequantization of this system is obtained by adapting the results of Section 2.

Since integral manifolds of the polarization D are k-tori, we have to determine which of them admit nonzero covariantly constant sections of L.

Theorem 4.

An integral manifold M of the distribution D admits a section σ of the complex line bundle L, which is nowhere zero when restricted to M, if and only if it satisfies the Bohr–Sommerfeld condition (47).

Proof.

Suppose that an integral manifold M of D admits a nowhere zero section of . Since is nowhere zero, it is a section of . Let be a loop in M. For each , let be the tangent vector to at t. Since is covariantly constant along M, Claim 2 applied to the section

gives

for every and every . Taking and gives

Since and , we get

Hence, Equation (48) is equivalent to

which integrated from 0 to gives

If bounds a surface , then Stokes’ theorem together with Equation (47) and the quantization condition (7) yield

because M is a Lagrangian submanifold of . Thus, , which implies that the nowhere zero section is parallel along . If does not bound a surface in M, but does satisfy the Bohr–Sommerfeld condition (47) with replaced by its pull back to P, then

so that

Hence, and the nowhere zero section is parallel along . □

Note that the manifolds M that satisfy Bohr–Sommerfeld conditions (47) are k-dimensional toric submanifolds of We call them Bohr–Sommerfeld tori. Since Bohr–Sommerfeld tori have dimension , there is no non-zero smooth section that is covariantly constant along D. However, for each Bohr–Sommerfeld torus M, Theorem 4 guarantees the existence of a non-zero, covariantly constant along smooth section , where denotes the restriction of L to M.

Let be the set of Bohr–Sommerfeld tori in P. For each , there exists a non-zero, covariantly constant along smooth section of L restricted to M determined up to a factor in . The direct sum

is the the space of quantum states of the Bohr–Sommerfeld theory. Thus, each Bohr–Sommerfeld torus M represents a 1-dimensional subspace of quantum states. Moreover, if because Bohr–Sommerfeld tori are mutually disjoint. Hence, the collection is a basis of

For our toral polarization , the space of smooth functions on P that are constant along F, see Equation (44), is , see Lemma A3. For each , the Hamiltonian vector field is in D, that is, for every basic state . Hence, the prequantization and quantization operators act on the basic states by multiplication by f, that is,

Note that is a constant because . For a general quantum state

We see that, for every function , each basic quantum state is an eigenstate of corresponding to the eigenvalue . Since eigenstates corresponding to different eigenvalues of the same symmetric operator are mutually orthogonal, it follows that the basis of is orthogonal. This is the only information we have about scalar product in . Our results do not depend on other details about the scalar product in .

3.3. Shifting Operators

3.3.1. The Simplest Case

We begin by assuming that with canonical coordinates where, for each , is the canonical angular coordinate on the torus and is the conjugate momentum. The symplectic form is

In this case, action–angle coordinates are obtained by rescaling the canonical coordinates so that, for every we have and . Moreover, the rescaled angle coordinate is interpreted as a multi-valued real function, the symplectic form

and the toric polarization of is given by

In terms of action–angle coordinates, the Bohr–Sommerfeld tori in are given by equation

where . For each , we denote by the corresponding Bohr–Sommerfeld torus in . If is the connection form in the principal line bundle , then sections

form a basis in the space of quantum states.

For each the vector field is transverse to D and , so that is the Hamiltonian vector field of . In the following, we write

to describe the actual vector field without referring to its relation to the action angle coordinates . Equation (36) in Section 2.1, for is multi-valued because the phase factor is multi-valued, and

Claim 5.

If , then

is well defined.

Proof.

For every , consider an open interval in such that . Let

Since the action–angle coordinates are continuous, W is an open subset of P. Let be a unique representative of with values in . With this notation,

The restriction to W of the vector field is the genuinely Hamiltonian vector field of , namely,

The vector field

is well defined. Equation (36) yields . Hence,

If we make another choice of intervals in such that and let . Then, with values in differs from by an integer, so that , and, in , we have

Moreover, , so that

Since we can cover P by open contractible sets defined in Equation (57), we conclude that is well defined by Equation (56) and depends only on the vector field □

Consequently, there exists a connection preserving automorphism such that, if , where is given by Equation (57), then

Claim 6.

The connection preserving automorphism , defined by Equation (62) depends only on the vector field and not the original choice of the action–angle coordinates.

Proof.

If is another set of action–angle coordinates then

where the matrices and lie in and . In the new coordinates,

Clearly,

To compare the phase factor entering Equation (55), we consider an open contractible set . As before, for each choose a single-valued representative of . Then,

where each is an integer and thus is also an integer. Hence,

where are integers. Since l is constant,

Therefore,

which shows that the automorphism depends on the vector field and not on the action angle coordinates in which it is computed. □

Claim 7.

For each , the symplectomorphism where h is Planck’s constant, preserves the set of Bohr–Sommerfeld tori in P.

Proof.

Since is complete, is a 1-parameter group of symplectomorphisms of . Hence, is well defined. By Equation (52), for every Bohr–Sommerfeld torus , where .

Since ,

This implies that, for every , and . Therefore, if , then , if , and if . This implies that is a Bohr–Sommerfeld torus. □

We denote by the action of on L. The automorphism acts on sections of L by pull back and push forward, namely,

Since is a connection preserving automorphism, it follows that, if satisfies the Bohr–Sommerfeld conditions, then and also satisfy the Bohr–Sommerfeld conditions. In other words, and preserve the space of quantum states. The shifting operators and corresponding to are the restrictions to of and respectively. For every Equations (53) and (56) yield

For each , . In addition, the operators , for , generate an abelian group of linear transformations of into itself, which acts transitively on the space of one-dimensional subspaces of .

Given a non-zero section supported on a Bohr–Sommerfeld torus, the family of sections

is a linear basis of invariant under the action of Since is abelian, there exists a positive, definite Hermitian scalar product on , which is invariant under the action of , and such that the basis in (71) is orthonormal. It is defined up to a constant positive factor. The completion of with respect to this scalar product yields a Hilbert space of quantum states in the Bohr–Sommerfeld quantization of . Elements of extend to unitary operators on .

3.3.2. General Case of Toral Polarization

Hilbert Space and Operators

Let be a symplectic manifold with toroidal polarization D and a covering by domains of action–angle coordinates. If U and are the domain of the angle-action coordinates and , respectively, and then in we have

where the matrices and lie in and .

Consider a complete locally Hamiltonian vector field X on such that, for each angle-action coordinates with domain U,

for some . Equation (72) shows that in , we have

where , for As in the preceding section, Equation (36) with , which is multi-valued, gives

which is multivalued, because the phase factor is multi-valued. As before, if we set , we would get a single-valued expression because . This would work along all integral curves for which are contained in U.

Now, consider the case when, for , and there exists such that , where U and are domains of action–angle variables and respectively. Moreover, assume that for and for Using the multi-index notation, for , we write

Let W be a neighborhood of in P such that and are contractible. For each let be a single-valued representative of as in the proof of Claim 5. Similarly, we denote by a single-valued representative of . Equation (73) shows that in , the functions and are local Hamiltonians of the vector field X and are constant along the integral curve of . Hence, we have to make the choice of representatives and so that

With this choice, , and

is well defined. It does not depend on the choice of the intermediate point in .

In the case when , action–angle coordinate charts with domains are needed to reach from ; we choose and end with . At each intermediate point we repeat the the argument of the preceding paragraph. We conclude that there is a connection preserving automorphism well defined by the procedure given here, and it depends only on the complete locally Hamiltonian vector field X satisfying condition (73). The automorphism of the principal bundle leads to an automorphism of the associated line bundle L. As in Equation (69), the shifting operators corresponded to the complete locally Hamiltonian vector field X are

In absence of monodromy, if we have k independent, complete, locally Hamiltonian vector fields on that satisfy the conditions leading to Equation (73), then the operators , for generate an abelian group of linear transformations of . If the local lattice of Bohr–Sommerfeld tori is regular, then acts transitively on the space of one-dimensional subspaces of . This enables us to construct an -invariant Hermitian scalar product on , which is unique up to an arbitrary positive constant. The completion of with respect to this scalar product yields a Hilbert space of quantum states in the Bohr–Sommerfeld quantization of .

Local Lattice Structure

The above discussion does not address the question of labeling the basic sections in by the quantum numbers associated to the Bohr–Sommerfeld k-torus , the support of .

These quantum numbers do depend on the choice of action angle coordinates. If is another choice of action angle coordinates in the trivializing chart , where , then the quantum numbers of T in coordinates are related to the quantum numbers of T in coordinates by a matrix such that , because by Claim A2 in Appendix A on the action coordinates is related to the action coordinate j by a constant matrix . Let . Then, is the local lattice structure of the Bohr–Sommerfeld tori , which lie in the action angle chart . If and are action angle charts, then the set of Bohr–Sommerfeld tori in are compatible. More precisely, on the local lattices and are compatible if there is a matrix such that . Let be a good covering of P, that is, every finite intersection of elements of is either contractible or empty, such that for each we have a trivializing chart for action angle coordinates for the toral bundle . Then, is a collection of pairwise compatible local lattice structures for the collection of Bohr–Sommerfeld tori on P. We say that has a local lattice structure.

The next result shows how the operator of Section 3.3 affects the quantum numbers of the Bohr–Sommerfeld torus .

Claim 8.

Let be a chart in for action angle coordinates . For every Bohr–Sommerfeld torus in U with quantum numbers , the torus is also a Bohr–Sommerfeld torus , where .

Proof.

For simplicity, we assume that . Suppose that the image of the curve lies in , where . For and we have

and . Since has action angle coordinates in U, the point has action angle coordinates . In particular, the point has action angle coordinates . Thus,

and for . Since T is the Bohr–Sommerfeld torus , we have . Then,

Thus, the torus is a Bohr–Sommerfeld torus with .

Now, consider the case when the image of the curve is not contained in V. This means that , where , does not contain the torus T. Since is a 1-parameter group of symplectomorphisms of , for every , the functions , with and are action angle coordinates on . Choose so that . Suppose that , where . Observe that for the action angle coordinates in U satisfy

Hence, and

because is constant. Moreover,

Similarly,

because T is a Bohr–Sommerfeld torus with quantum numbers . Thus, is a Bohr–Sommerfeld torus corresponding to the quantum numbers . This argument may be extended to cover the case where for any positive integer k and . □

3.4. Singularity of Toral Polarization in Completely Integrable Hamiltonian Systems

A completely integrable Hamiltonian system on a symplectic manifold of dimension is given by k functions which Poisson commute with each other, and are independent on the open dense subset of We assume that, for every and each , the maximal integral curve of through x is periodic with period The complement of in P is the set of singular points of the real polarization of

Applying the arguments of Section 3.1 and the beginning of Section 3.2, we obtain the set of Bohr–Sommerfeld tori M in P. Each M is an integral manifold of D, which admits a covariantly constant section . The section is determined up to a non-zero constant. The direct sum

is the space of quantum states of the Bohr–Sommerfeld theory. Each Bohr–Sommerfeld torus M represents a one-dimensional subspace of quantum states. The collection is a basis of , and

Let be the set of the Bohr–Sommerfeld tori in . Then,

is the space of quantum states of the system, which are described by the Bohr–Sommerfeld quantization of . The collection is a basis of , and

for every

The restriction of D to is a toral polarization of discussed earlier. The functions , which define the system, give rise to action–angle coordinates on , where for each and is the multivalued angle coordinate corresponding to . Since we deal with the single set of action–angle coordinates, most of the analysis of Section 3.3.1 applies to this problem. As in Section 3.3.2, Equation (54), for we introduce the notation

Each is a locally Hamiltonian vector field on . However, since , we cannot assume that the vector field is complete.

In terms of action–angle coordinates on the Bohr–Sommerfeld tori in are given by equation

where . For ,

denotes the Bohr–Sommerfeld torus in corresponding to the eigenvalue of If is not in the spectrum of , then In a trivialization of the complex line bundle L restricted to , for each we can choose

form a basis in the space of quantum states in .

Claim 5 implies the following

Corollary 1.

If, for every and each Planck constant is in the domain of the maximal integral curve of starting at x, then is well defined.

Under the assumptions of Corollary 1, we may follow the arguments of Section 3.3.1 leading to Equation (70). Applied to the case under consideration, it may be rewritten as follows. For every such that one has

if , and

if .

It remains to extend the action of and given above to all states in This involves a study of the integral curves of on P, which originate or end at points in the singular set .

Suppose we manage to extend the action of the shifting operators to all states in Monodromy occurs when, there exist loops in the local lattice of Bohr–Sommerfeld tori such that for some the mapping

need not be the identity on . In this case shifting operators are multivalued, and there exists a phase factor such that

Given a non-zero section supported on a Bohr–Sommerfeld torus Any maximal family

of sections in , such that no two sections in B are supported on the same Bohr–Sommerfeld torus, is a linear base of . We can define a scalar product on as follows. First, assume that basic sections supported on different Bohr–Sommerfeld tori are perpendicular to each other. Then, assume that for every ,

This definition works even in the presence of monodromy. The completion of with respect to this scalar product yields a Hilbert space of quantum states in the Bohr–Sommerfeld quantization of the completely integrable Hamiltonian system under consideration.

Example: The 2-d Harmonic Oscillator

We consider the harmonic oscillator with 2 degrees of freedom, see [9]. Its configuration space is with coordinates . Its phase space has coordinates with symplectic form . The 2-d harmonic oscillator is completely integrable with integrals the Hamiltonian with and the angular momentum with .

The change of variables

is symplectic, that is, , preserves the diagonal form of the Hamiltonian , and diagonalizes the angular momentum . The functions

are action variables for the two-dimensional harmonic oscillator. The corresponding angle variables are and , respectively. In the variables the symplectic form is . The rescaled action angle coordinates , used previously, are given by

The Bohr–Sommerfeld tori are parameterized by two integers The corresponding basic sections are

see Equation (80). Equations (83) yield

Hence, the quantum operators and act on as follows.

where and

The regular part of is

The singular part of consists of three strata

is the origin of , while and are cylinders parameterized by and respectively.

As before, for we consider the locally Hamiltonian vector fields

The conditions of Corollary 1 are satisfied. Hence, in , we get shifting operators

Next, we have to consider limits as integral curves of . Note that the integral curve of originating at after time reaches . Moreover, the integral curve of originating at for after time reaches and after time reaches the origin Similarly, the integral curve of originating at after time reaches and after time it reaches for every . This argument also applies to . It enlarges the above table of shifting operators as follows.

Since is unbounded as , it is not possible to discuss integral curves of starting at points in . However, for ,

Thus, shifts in the opposite direction to . Similarly, shifts in the opposite direction to It is natural to extend these relations to the boundary and assume that

The actions of the lowering operators on states and on states not defined, but they never occur in the theory. Therefore, we may assume that

3.5. Monodromy

Suppose that is a good covering of P such that for every the chart is the domain of a local trivialization of the toral bundle , associated to the fibrating toral polarization D of P, given by the local action angle coordinates

with . We suppose that the set of Bohr–Sommerfeld tori on P has the local lattice structure of Section 3.3.

Let p and and let be a smooth curve joining p to . We can choose a finite good subcovering of such that , where and . Using the fact that the local lattices are compatible, we can extend the local action functions on to a local action function on . Thus, using the connection (see Corollary A1), we may parallel transport a Bohr–Sommerfeld torus along the curve to a Bohr–Sommerfeld torus (see Claim 7). The action function at , in general depends on the path . If the holonomy group of the connection on the bundle consists only of the identity element in , then this extension process does not depend on the path . Thus, we have shown

Claim 9.

If D is a fibrating toral polarization of with fibration and B is simply connected, then there are global action angle coordinates on P and the Bohr–Sommerfeld tori have a unique quantum number . Thus, the local lattice structure of is the lattice .

If the holonomy of the connection on P is not the identity element, then the set of Bohr–Sommerfeld tori is not a lattice and it is not possible to assign a global labeling by quantum numbers to all the tori in . This difficulty in assigning quantum numbers to Bohr–Sommerfeld tori has been known to chemists since the early 1920s. Modern papers illustrating it can be found in [18,19]. We give a concrete example where the connection has nontrivial holonomy, namely, the spherical pendulum.

Example: Spherical Pendulum

The spherical pendulum is a completely integrable Hamiltonian system , where is the cotangent bundle of the 2-sphere with the Euclidean inner product on , see [20]. The Hamiltonian is

where and the -component of angular momentum is

The energy momentum map of the spherical pendulum is

Here, is the closure in of the set R of regular values of the integral map . The point is an isolated critical value of . Thus, the set R has the homotopy type of and is not simply connected. Every fiber of

over a point is a smooth 2-torus , see chapter V of [21]. At every point of there are local action angle coordinates . The actions are and . Here,

where and , and

while the angles are and , where

and

where t is the time parameter of the integral curves of the vector field on the 2-torus , which are periodic of period , see Section 2.4 of [20]. The action map

is a homeomorphism of onto , which is a real analytic diffeomorphism of onto , see Fact 2.4 in [20].

For every , the Bohr–Sommerfeld tori are

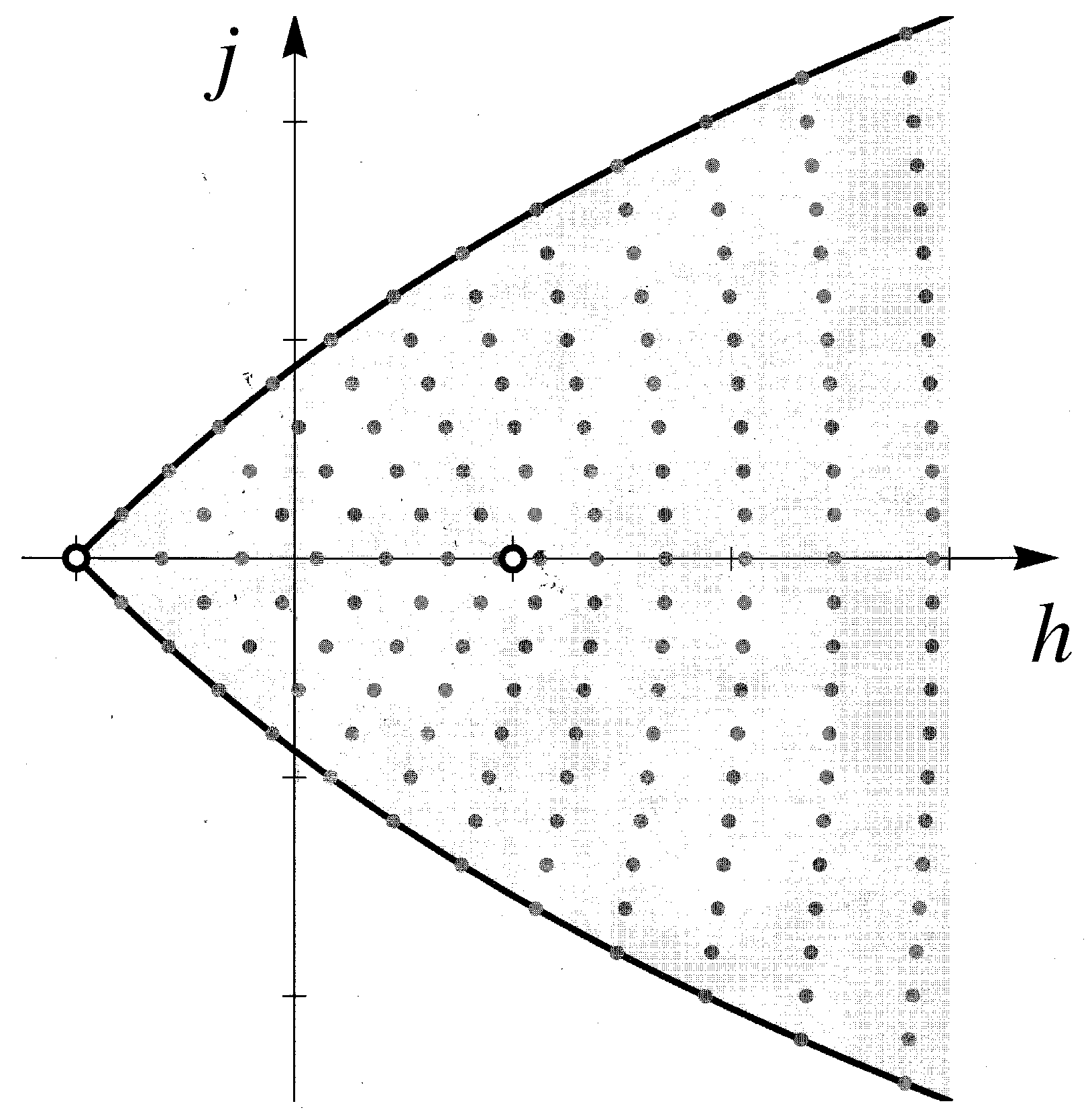

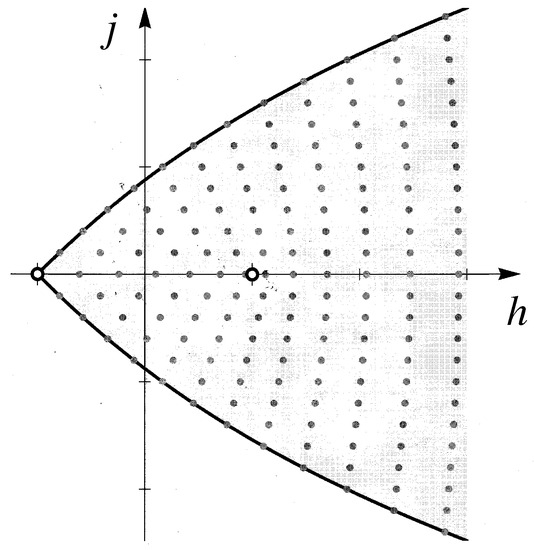

The fibers of corresponding to the dark points in Figure 1 are the Bohr–Sommerfeld tori.

Figure 1.

The Bohr–Sommerfeld quantum states of the spherical pendulum in .

The basic sections of the quantum line bundle are

The family of sections forms a basis of quantum states of the Bohr–Sommerfeld theory of the spherical pendulum. Let be the Hilbert space of quantum states for

which is an orthogonal basis. The Bohr–Sommerfeld energy momentum spectrum of the spherical pendulum is the range of the map

are the quantum numbers of the spherical pendulum.

In terms of actions and , we may write . Hence, the quantum operators and act on the basic sections as follows

and

The regular part of is

The singular part of consists of six strata:

The stratum is the point ; while the stratum is the point . The stratum is the subset of , where and , which is a cylinder parameterized by ; while is the subset where and , which is a cylinder parameterized by . The stratum is the subset of where and , which is a cylinder parameterized by ; while is the subset where and , which is a cylinder parameterized by .

The conditions of Corollary 1 are satisfied. For let . In the regular stratum we get the shifting operators

Arguing as in the example of the 2-d harmonic oscillator, we can extend the above relations to

In addition, we may assume that

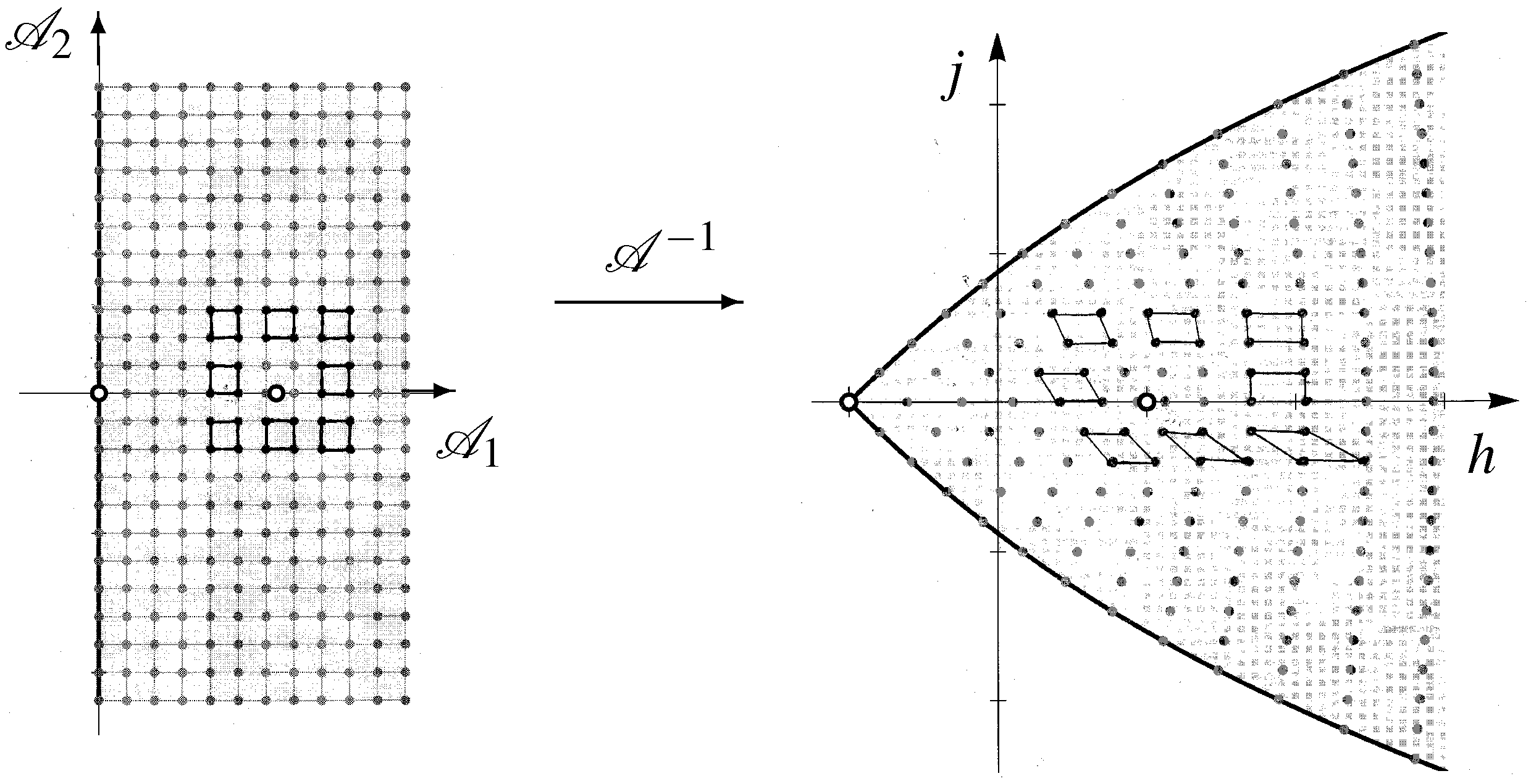

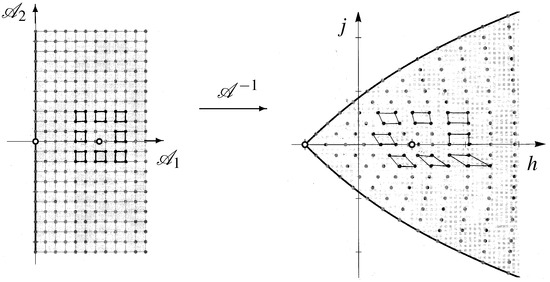

Since the are no global action angle coordinates, the action function on R is multi-valued. After encircling the point , the quantum number of the Bohr–Sommerfeld torus represented by the upper right hand vertex of the rectangle on the h-axis, see Figure 2, becomes the quantum number of the upper right hand vertex of the parallelogram formed by applying to the original rectangle, which is the transpose of the monodromy matrix M of the spherical pendulum.

Figure 2.

Using the shifting operators to show that the quantized spherical pendulum has monodromy.

The holonomy of the connection is called the monodromy of the fibrating toral polarization D on with fibration .

Corollary 2.

Let be the universal covering space of B with covering map . The monodromy map M, which is a nonidentity element holonomy group of the connection on the bundle ρ sends one sheet of the universal covering space to another sheet.

Proof.

Since the universal covering space of B is simply connected and we can pull back the symplectic manifold and the fibrating toral distribution D by the universal covering map to a symplectic manifold and a fibrating toral distribution with associated fibration . The connection on the bundle pulls back to a connection on the bundle . Let be a closed curve on B and let M be the holonomy of the connection on B along . Then, lifts to a curve on , which covers , that is, . Thus, parallel transport of a k-torus , which is an integral manifold of the distribution , along the curve gives a linear map M of the lattice defining the k-torus . The map M is the same as the linear map M of into itself given by parallel transporting T, using the connection , along the closed on B because the connection is the pull back of the connection by the covering map . The closed curve in B represents an element of the fundamental group of B, which acts as a covering transformation on the universal covering space that permutes the sheets (= fibers) of the universal covering map . □

In the spherical pendulum, the universal covering space of is . If we cut R by the line segment , then is simply connected and hence represents one sheet of the universal covering map of R. For more details on the universal covering map, see [22]. The curve chosen in the example has holonomy . It gives a map of into itself, which sends to the adjacent sheet of the covering map. Thus, we have a rule how the labelling of the Bohr–Sommerfeld torus , corresponding to , changes when we go to an adjacent sheet, which covers , namely, we apply the matrix M to the integer vector . Since our chosen curve generates the fundamental group of , we know what the quantum numbers of Bohr–Sommerfeld are for any closed curve in , which encircles the origin.

Author Contributions

The author R.C. conceptualized and wrote Section 2, the appendix, and the spherical pendulum example. The author J.Ś. conceptualized and wrote the rest. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This reasearch received no extenal funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

We return to study the symplectic geometry of a fibrating toral polarization D of the symplectic manifold in order to explain what we mean by its local integral affine structure, see [23].

We assume that the integral manifolds of the Lagrangian distribution D on P form a smooth manifold B such that the map

is a proper surjective submersion. If the distribution D has these properties we refer to it as a fibrating polarization of with associated fibration.

Lemma A1.

Suppose that D is a fibrating polarization of . Then, the associated fibration has an Ehresmann connection with parallel translation. Thus, the fibration is locally trivial bundle.

Proof.

We construct the Ehresmann connection as follows. For each let be a Darboux chart for . In other words, is the standard symplectic form on , where with . In more detail, for every there is a frame of P at u, whose image under is the frame of , where , such that

and

For , we see that is a Lagrangian subspace of the symplectic vector space . Let be a basis of with the corresponding dual basis of . Extend each covector by zero to a covector in , that is, extend the basis of to a basis of , where Since is a linear isomorphism with inverse for every , we see that the collection

of vectors in spans an k-dimensional subspace . We now show that is a Lagrangian subspace of . By definition

The last equality above follows because . To see this we note that

The Lagrangian subspace is complementary to the Lagrangian subspace , that is, for every .

Consequently, is a Lagrangian subspace of , which is complementary to the Lagrangian subspace . Since the mapping is smooth and has constant rank, it defines a Lagrangian distribution on U. Hence, we have a Lagrangian distribution on . Since is the tangent space to the fiber , the distribution defines the vertical Lagrangian distribution on P. Because , it follows that . Hence, the linear mapping is an isomorphism. Since for every and the mapping is an isomorphism for every , the distributions and on P define an Ehresmann connection for the Lagrangian fibration . □

Let X be a smooth complete vector field on B with flow . Because the linear mapping is bijective, there is a unique smooth vector field on P, called the horizontal lift of X, which is -related to X, that is, for every . Let be the flow of . Then, . Let be a smooth local section of the bundle . Define the covariant derivative of with respect to the vector field X by

for all . Because the bundle projection map is proper, parallel transport of each fiber of the bundle by the flow of is defined as long as the flow of X is defined. Because the Ehresmann connection has parallel transport, the bundle presented by is locally trivial, see pp. 378–379, [21].

Claim A1.

If D is a fibrating polarization of the symplectic manifold , then for every the integral manifold of D through p is a smooth Lagrangian submanifold of P, which is an k-torus T. In fact T is the fiber over of the associated fibration .

We say that D is a fibrating toral polarization of if it satisfies the hypotheses of Claim A1. The proof of Claim A1 requires several preparatory arguments.

Let . Then, . Let be the Hamiltonian vector field on with Hamiltonian . We have

Lemma A2.

Every fiber of the locally trivial bundle is an invariant manifold of the Hamiltonian vector field .

Proof.

We need only show that for every and every , we have . Let Y be a smooth vector field on the integral manifold with flow . Then,

since maps into itself. So

However, is a Lagrangian subspace of the symplectic vector space . Consequently, . □

Since the mapping is surjective and proper, for every the fiber is a smooth compact submanifold of P. Hence, the flow of the vector field is defined for all .

Lemma A3.

Let f, . Then, .

Proof.

For every and every from Lemma A2 it follows that and lie in . Because is a Lagrangian submanifold of , we get

Since , we see that (A1) holds for every . □

Proof of Claim A1.

From Lemma A3 it follows that is an abelian subalgebra of the Poisson algebra . Since the bundle projection mapping is surjective and , the algebra has k generators, say, , whose differentials at q span for every and every . Using the flow of the Hamiltonian vector field on define the -action

Since and each fiber is connected, being an integral manifold of the distribution D, it follows that the -action is transitive on each fiber of the bundle . Thus, is diffeomorphic to , where is the isotropy group at q. If for some , then the fiber would be diffeomorphic to . However, this contradicts the fact the every fiber of the bundle is compact. Hence, for every . Since is diffeomorphic to , they have the same dimension, namely, k. Hence, is a zero dimensional Lie subgroup of . Thus, is a rank k lattice . Thus, the fiber is , which is an affinek-torus . □

We now apply the action angle theorem, see chapter IX of [21], to the fibrating toral Lagrangian polarization D of the symplectic manifold with associated toral bundle to obtain a more precise description of the Ehresmann connection constructed in Claim A1. For every there is an open neighborhood U of the fiber in P and a symplectic diffeomorphism

such that

is the momentum mapping of the Hamiltonian -action on . Here, . Thus, the bundle is locally a principal -bundle. Moreover, we have .

Corollary A1.

Using the chart for action angle coordinates , the Ehresmann connection gives an Ehresmann connection on the bundle defined by

Proof.

This follows because

for every . From the preceding equations for every we have and . Here, . □

Corollary A2.

The Ehresmann connection on the locally trivial toral Lagrangian bundle is flat, that is, for every smooth vector field X on B and every local section σ of .

Proof.

In action angle coordinates a local section section of the bundle is given by . Let for some with flow . Let be the horizontal lift of X with respect to the Ehresmann connection on the bundle . Thus, for every we have

This proves the corollary, since every vector field X on may be written as for some and the flow of on V pairwise commute. □

Claim A2.

Let be a locally trivial toral Lagrangian bundle, where is a smooth symplectic manifold. Then, the smooth manifold B has an integral affine structure. In other words, there is a good open covering of B such that the overlap maps of the coordinate charts given by

where , have derivative , which does not depend on .

Proof.

Cover P by , where is an action angle coordinate chart. Since every open covering of P has a good refinement, we may assume that is a good covering. Let . Then, is a good open covering of B and is a coordinate chart for B. By construction of action angle coordinates, in the overlap map sends the action coordinates in to the action coordinates in . The period lattices and are equal since for some we have and . Moreover, these lattices do not depend on the point p. Thus, the derivative sends the lattice spanned by into itself. Hence, for every the matrix of has integer entries, that is, it lies in and the map is continuous. However, is a discrete subgroup of the Lie group and is connected, since is a good covering. Thus, does not depend on . □

Corollary A3.

Let be a smooth closed curve in B. Let be parallel translation along γ using the Ehresmann connection on the bundle . Then, the holonomy group of the k-toral fiber is induced by the group of affine -linear maps of into itself.

References

- Heisenberg, W. Über die quantentheoretische Umdeutung kinematischer und mechanischer Beziehungen. Z. Phys. 1925, 33, 879–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kostant, B. Quantization and unitary representations. I. Prequantization. In Lectures in Modern Analysis and Applications III; Lecture Notes in Mathematics; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 1970; Volume 170, pp. 87–208. [Google Scholar]

- Souriau, J.-M. Quantification géométrique. In Physique Quantique et Géométrie; Hermann: Paris, France, 1988; pp. 141–193. [Google Scholar]

- Blattner, R.J. Quantization in representation theory, In Harmonic Analysis on Homogeneous Spaces; Taam, E.T., Ed.; American Mathematical Society: Providence, RI, USA, 1973; Volume 26, pp. 146–165. [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi, S.; Nomizu, K. Foundations of Differential Geometry; Interscience Publishers: New York, NY, USA, 1963; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Souriau, J.-M. Structure des Systèmes Dynamiques; Dunod: Paris, France, 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Śniatycki, J. Geometric Quantization and Quantum Mechanics; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Dirac, P.A.M. Elimination of the nodes in quantum mechanics. Proc. Roy. Soc. A 1926, 111, 281–305. [Google Scholar]

- Cushman, R.; Śniatycki, J. Bohr-Sommerfeld-Heisenberg quantization of the 2-dimensional harmonic oscillator. arXiv 2012, arXiv:1207.1477v2. [Google Scholar]

- Cushman, R.; Śniatycki, J. On Bohr-Sommerfeld-Heisenberg quantization. J. Geom. Symmetry Phys. 2014, 35, 11–19. [Google Scholar]

- Cushman, R.; Śniatycki, J. Bohr-Sommerfeld-Heisenberg quantization of the mathematical pendulum. J. Geom. Mech. 2018, 10, 419–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Śniatycki, J. Lectures on geometric quantization. In Proceedings of the Seventeenth International Conference on Geometry, Integrability and Quantization, Varna, Bulgaria, 5–10 June 2015; Mladenov, I., Meng, G., Yoshioka, A., Eds.; Institute of Biophysics and Biomedical Engineering, Bulgarian Academy of Sciences. Avangard Prima: Sofia, Bulgaria, 2016; pp. 95–129. [Google Scholar]

- Sikorski, R. Abstract covariant derivative. Coll. Math. 1967, 18, 252–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sikorski, R. Wstęp Do Geometrii Różniczkowej; PWN: Warszawa, Poland, 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Śniatycki, J. Differential Geometry of Singular Spaces and Reduction of Symmetry; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Bohr, N. On the constitution of atoms and molecules (Part I). Philos. Mag. 1913, 26, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sommerfeld, A. Zur Theorie der Balmerschen Serie. Sitzungberichte der Bayerischen Akademie der Wissenschaften (München). Mathe-Matisch-Physikalische Klasse 1915. pp. 425–458. Available online: https://www.zobodat.at/pdf/Sitz-Ber-Akad-Muenchen-math-Kl_1915_0425-0458.pdf (accessed on 21 September 2020).

- Winnewisser, M.; Winnewisser, B.P.; Medvedev, I.R.; De Lucia, F.C.; Ross, S.C.; Bates, L.M. The hidden kernel of molecular quasi-linearity: Quantum monodromy. J. Mol. Struct. 2006, 798, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cushman, R.H.; Dullin, H.R.; Giacobbe, A.; Holm, D.D.; Joyeux, M.; Lynch, P.; Sadovskií, D.A.; Zhilinskií, B.I. CO2 Molecule as a quantum realization of the 1:1:2 resonant swing-spring with monodromy. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2004, 93, 024302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cushman, R.; Śniatycki, J. Classical and quantum spherical pendulum. arXiv 2016, arXiv:1603.00966v1. [Google Scholar]

- Cushman, R.H.; Bates, L.M. Global Aspects of Classical Integrable Systems, 2nd ed.; Birkhauser: Basel, Switzerland; Springer: Basel, Switzerland, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Cushman, R.; Śniatycki, J. Globalization of a theorem of Horozov. Indag. Math. 2016, 26, 1030–1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lukina, O.V.; Takens, F.; Broer, H.W. Global properties of integrable Hamiltonian systems. Reg. Chaotic Dyn. 2008, 13, 602–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).