Next Generation Sequencing (NGS) Target Approach for Undiagnosed Dysglycaemia

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Cases Used for Validation

Sequencing

2.2. NGS Ampliseq Protocol

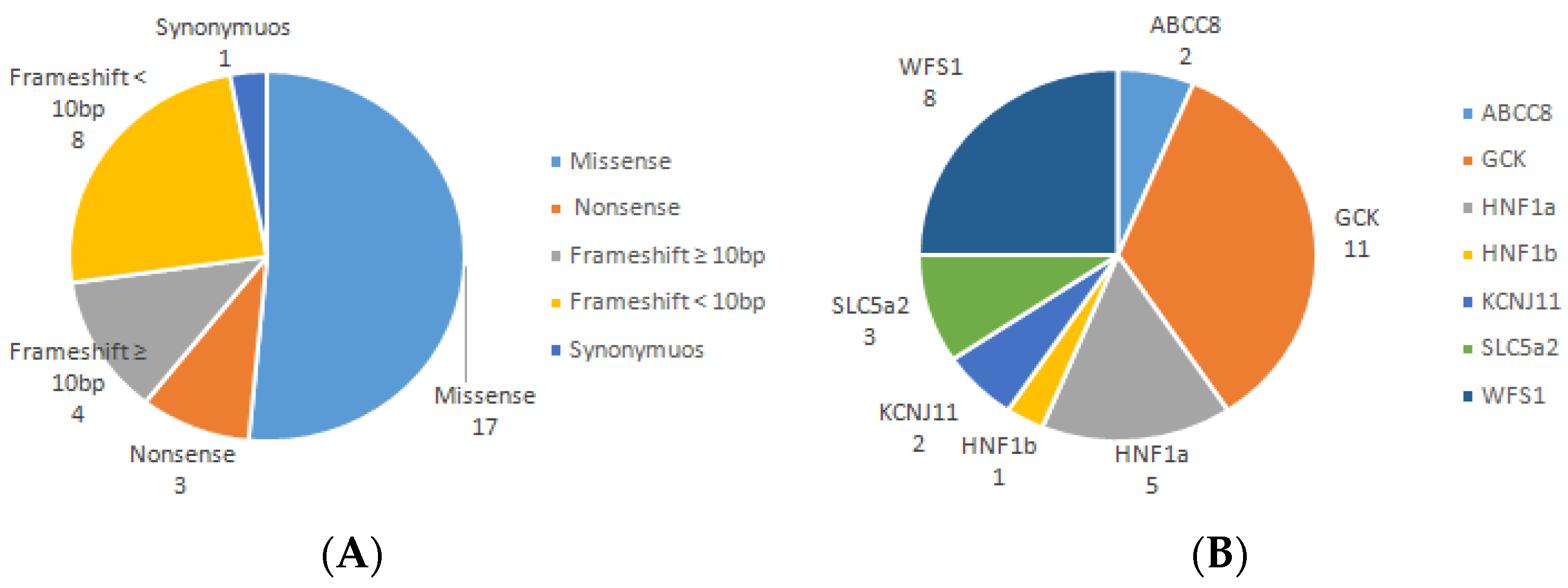

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hattersley, A.T.; Greeley, S.A.W.; Polak, M.; Rubio-Cabezas, O.; Njølstad, P.R.; Mlynarski, W.; Castano, L.; Carlsson, A.; Raile, K.; Chi, D.V.; et al. ISPAD Clinical Practice Consensus Guidelines 2018: The diagnosis and management of monogenic diabetes in children and adolescents. Pediatr. Diabetes 2018, 19, 47–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kleinberger, J.W.; Pollin, T.I. Undiagnosed MODY: Time for Action. Curr. Diab. Rep. 2015, 12, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanyoura, M.; Philipson, L.H.; Naylor, R. Monogenic Diabetes in Children and Adolescents: Recognition and Treatment Options. Curr. Diab. Rep. 2018, 8, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Urrutia, I.; Martínez, R.; Rica, I.; Martínez de LaPiscina, I.; García-Castaño, A.; Aguayo, A.; Calvo, B.; Castaño, L. Negative autoimmunity in a Spanish pediatric cohort suspected of type 1 diabetes, could it be monogenic diabetes? PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0220634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gandica, R.G.; Chung, W.K.; Deng, L.; Goland, R.; Gallagher, M.P. Identifying monogenic diabetes in a pediatric cohort with presumed type 1 diabetes. Pediatr. Diabetes 2015, 16, 227–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Miao, D.; Babu, S.; Yu, J.; Barker, J.; Klingensmith, G.; Rewers, M.; Eisenbarth, G.S.; Yu, L. Prevalence of autoantibody-negative diabetes is not rare at all ages and increases with older age and obesity. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2007, 99, 88–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shepherd, M.; Shields, B.; Hammersley, S.; Hudson, M.; McDonald, T.J.; Colclough, K.; Oram, R.A.; Knight, B.; Hyde, C.; Cox, J.; et al. Systematic Population Screening, Using Biomarkers and Genetic Testing, Identifies 2.5% of the U.K. Pediatric Diabetes Population With Monogenic Diabetes. Diabetes Care 2016, 39, 1879–1888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yohe, S.; Thyagarajan, B. Review of Clinical Next-Generation Sequencing. Arch. Pathol. Lab. Med. 2017, 141, 1544–1557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez-Marmiesse, A.; Gouveia, S.; Couce, M.L. NGS Technologies as a Turning Point in Rare Disease Research, Diagnosis and treatment. Curr. Med. Chem. 2018, 25, 404–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehder, C.; Bean, L.J.H.; Bick, D.; Chao, E.; Chung, W.; Das, S.; O’Daniel, J.; Rehm, H.; Shashi, V.; Vincent, L.M.; et al. Next-generation sequencing for constitutional variants in the clinical laboratory, 2021 revision: A technical standard of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (ACMG). Genet. Med. 2021, 8, 1399–1415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Yang, Y.; Huang, L.; Kong, M.; Yang, Z. A novel compound heterozygous mutation in SLC5A2 contributes to familial renal glucosuria in a Chinese family, and a review of the relevant literature. Mol. Med. Rep. 2019, 19, 4364–4376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Astuti, D.; Sabir, A.; Fulton, P.; Zatyka, M.; Williams, D.; Hardy, C.; Milan, G.; Favaretto, F.; Yu-Wai-Man, P.; Rohayem, J.; et al. Monogenic diabetes syndromes: Locus-specific databases for Alström, Wolfram, and Thiamine-responsivemegaloblastic anemia. Hum. Mutat. 2017, 38, 764–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, M.; Gong, S.; Han, X.; Zhang, S.; Ren, Q.; Cai, X.; Luo, Y.; Zhou, L.; Zhang, R.; Liu, W.; et al. Genetic variants of ABCC8 and phenotypic features in Chinese early onset diabetes. J. Diabetes 2021, 13, 542–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qian, X.; Qin, L.; Xing, G.; Cao, X. Phenotype Prediction of Pathogenic Nonsynonymous Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms in WFS1. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 14731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colosimo, A.; Guida, V.; Rigoli, L.; Di Bella, C.; De Luca, A.; Briuglia, S.; Stuppia, L.; Salpietro, D.C.; Dallapiccola, B. Molecular Detection of Novel WFS1 Mutations in Patients with Wolfram Syndrome by a DHPLC-Based Assay. Hum. Mutat. 2003, 21, 622–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavić, T.; Juszczak, A.; Medvidović, E.P.; Burrows, C.; Šekerija, M.; Bennett, A.J.; Knežević, J.Ć.; Gloyn, A.L.; Lauc, G.; McCarthy, M.I.; et al. Maturity onset diabetes of the young due to HNF1A variants in Croatia. Biochem. Med. 2018, 28, 020703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colclough, K.; Ellard, S.; Hattersley, A.; Patel, K. Syndromic Monogenic Diabetes Genes Should Be Tested in Patients with a Clinical Suspicion of Maturity-Onset Diabetes of the Young. Diabetes 2022, 71, 530–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Philippe, J.; Derhourhi, M.; Durand, E.; Vaillant, E.; Dechaume, A.; Rabearivelo, I.; Dhennin, V.; Vaxillaire, M.; De Graeve, F.; Sand, O.; et al. What Is the Best NGS Enrichment Method for the Molecular Diagnosis of Monogenic Diabetes and Obesity? PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0143373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, M.R. Review of current status of molecular diagnosis and characterization of monogenic diabetes mellitus: A focus on next-generation sequencing. Expert Rev. Mol. Diagn. 2020, 20, 413–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zmysłowska, A.; Bodalski, J.; Młynarski, W. The rare syndromic forms of monogenic diabetes in childhood [abstract]. Pediatr. Endrocrinol. Diabetes Metab. 2008, 14, 41–43. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, X.; Shao, Y.; Tian, L.; Flasch, D.A.; Mulder, H.L.; Edmonson, M.N.; Liu, Y.; Chen, X.; Newman, S.; Nakitandwe, J.; et al. Analysis of error profiles in deep next-generation sequencing data. Genome Biol. 2019, 20, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pfeiffer, F.; Gröber, C.; Blank, M.; Händler, K.; Beyer, M.; Schultze, J.L.; Mayer, G. Systematic evaluation of error rates and causes in short samples in next-generation sequencing. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 10950. [Google Scholar]

- Fujita, S.; Masago, K.; Okuda, C.; Hata, A.; Kaji, R.; Katakami, N.; Hirata, Y. Single nucleotide variant sequencing errors in whole exome sequencing using the Ion Proton System. Biomed. Rep. 2017, 7, 17–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- López-Garrido, M.P.; Herranz-Antolín, S.; Alija-Merillas, M.J.; Giralt, P.; Escribanol, J. Co-inheritance of HNF1a and GCK mutations in a family with maturity-onset diabetes of the young (MODY): Implications for genetic testing. Clin. Endocrinol. 2013, 79, 342–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbetti, F.; Rapini, N.; Schiaffini, R.; Bizzarri, C.; Cianfarani, S. The application of precision medicine in monogenic diabetes. Expert Rev. Endocrinol. Metab. 2022, 17, 111–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Gene | Location | Phenotype | Phenotype MIM Number | Inheritance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ABCC8 | 11p15.1 | MODY, type 12 | 600509 | AD, AR |

| AIRE | 21q22.3 | Autoimmune polyendocrinopathy syndrome, type I, with or without reversible metaphyseal dysplasia | 240300 | AD, AR |

| ALMS1 | 2p13.1 | Alstrom syndrome | 203800 | AR |

| APPL1 | 3p14.3 | MODY, type 14 | 616511 | AD |

| AQP2 | 12q13.12 | Diabetes insipidus, nephrogenic, 2 | 125800 | AD, AR |

| AVPR2 | Xq28 | Diabetes insipidus, nephrogenic, 1 | 304800 | XLR |

| BBS1 | 11q13.2 | Bardet–Biedl syndrome 1 | 209900 | AR, DR |

| BLK | 8p23.1 | MODY, type 11 | 613375 | AD |

| CISD2 | 4q24 | Wolfram syndrome 2 | 604928 | AR |

| DIAPH1 | 5q31.3 | Deafness, autosomal dominant 1, with or without thrombocytopenia/Seizures, cortical blindness, microcephaly syndrome | 124900/616632 | AD/AR |

| GATA6 | 18q11.2 | Pancreatic agenesis and congenital heart defects | 600001 | AD |

| GCK | 7p13 | MODY, type 2 | 125851 | AD |

| GJB2 | 13q12.11 | Deafness, autosomal recessive 1A | 220290 | AR, AD |

| GLIS3 | 9p24.2 | Diabetes mellitus, neonatal, with congenital hypothyroidism | 610199 | AR |

| GLUD1 | 10q23.2 | Hyperinsulinism-hyperammonemia syndrome | 606762 | AD |

| HADH | 4q25 | 3-hydroxyacyl-CoA dehydrogenase deficiency/Hyperinsulinemic hypoglycemia, familial, 4 | 231530/609975 | AR/AR |

| HNF1a | 12q24.31 | MODY, type3 | 600496 | AD |

| HNF1b | 17q12 | MODY, type 5 Renal cysts, and diabetes syndrome | 137920 | AD |

| HNF4a | 20q13.12 | MODY, type 1 | 125850 | AD |

| IL2RA | 10p15.1 | Diabetes mellitus, insulin-dependent, susceptibility to, 10/Immunodeficiency 41 with lymphoproliferation and autoimmunity | 601942/606367 | Nd/AR |

| INS | 11p15.5 | MODY, type 10 | 613370 | AD |

| INSR | 19p13.2 | Hyperinsulinemic hypoglycemia, familial, 5/Leprechaunism/ Rabson–Mendenhall syndrome/Diabetes mellitus, insulin-resistant, with acanthosis nigricans | 609968/246200/262190/ 610549 | AD/AR/AR/Nd |

| KCNJ11 | 11p15.1 | MODY, type 13 | 616329 | AD |

| KFL11 | 2p25.1 | MODY, type 7 | 610508 | AD |

| LRBA | 4q31.3 | Immunodeficiency, common variable, 8, with autoimmunity | 614700 | AR |

| MAGEL2 | 15q11.2 | Schaaf-Yang syndrome | 615547 | AD |

| NeuroD1 | 2q31.3 | MODY, type 6 Maturity-onset diabetes of the young 6 | 606394 | AD |

| OPA1 | 3q29 | Mitochondrial DNA depletion syndrome 14 (encephalocardiomyopathic type)/Behr syndrome/Optic atrophy 1/Optic atrophy plus syndrome/Glaucoma, normal tension, susceptibility | 616896/210000/165500/ 125250/606657 | AR/AR/AD/AD/Nd |

| OPA3 | 19q13.32 | 3-methylglutaconic aciduria, type III/Optic atrophy 3 with cataract | 258501/165300 | AR/ AD |

| PAX4 | 7q32.1 | MODY, type 9 | 612225 | AD |

| PAX6 | 11p13 | Coloboma of optic nerve/Coloboma, ocular/Morning glory disc anomaly/Aniridia/Anterior segment dysgenesis 5, multiple subtypes/Cataract with late-onset corneal dystrophy/Foveal hypoplasia 1/Keratitis/Optic nerve hypoplasia | 120430/120200/120430/ 106210/604229/106210/136520 /148190/165550 | AD/AD/AD/AD/AD/AD/AD/AD/AD |

| PDX1-IPF1 | 13q12.2 | MODY, type IV/Pancreatic agenesis 1/Diabetes mellitus, type II, susceptibility | 606392/260370/125853 | AD/AR/AD |

| POU3F4 | Xq21.1 | Deafness, X-linked 2 | 304400 | XLR |

| RFX6 | 6q22.1 | Mitchell–Riley syndrome | 615710 | AR |

| SEL1L | 14q31.1 | Branchial cleft syndrome involving hypertelorism, preauricular sinus, punctal pits, and deafness | 614187 | AD, AR |

| SH2B1 | 16p11.2 | Severe obesity, insulin resistance, and neurobehavioral abnormalities | 608937 | AD |

| SLC5A2 | 16p11.2 | Renal glucosuria | 233100 | AD, AR |

| SOX9 | 17q24.3 | Acampomelic campomelic dysplasia | 114290 | AD |

| SOX17 | 8q11.23 | Vesicoureteral reflux 3 | 613674 | AD |

| STAT1 | 2q32.2 | Immunodeficiency 31A, mycobacteriosis, autosomal dominant/Immunodeficiency 31B, mycobacterial and viral infections, autosomal recessive/Immunodeficiency 31C, chronic mucocutaneous candidiasis, autosomal dominant | 614892/613796/614162 | AD/AR/AD |

| STAT3 | 17q21.2 | Autoimmune disease, multisystem, infantile-onset, 1/Hyper-IgE recurrent infection syndrome | 615952/147060 | AD/AD |

| STAT5B | 17q21.2 | Growth hormone insensitivity with immune dysregulation 1, autosomal recessive/Growth hormone insensitivity with immune dysregulation 2, autosomal dominant | 245590/618985 | AR/AD |

| TMEM126A | 11q14.1 | Optical trophy 7 | 612989 | AR |

| WFS1 | 4p16.1 | Wolfram Syndrome 1 | 222300 | AR |

| Sample ID | Gene | Transcript | Mutation Detected by Sanger | Type of Mutation | Detected by NGS | ACMG | Additional Variants |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample 1 | WFS1 | NM_006005.3 | c.2389 G > A; p.Asp797Asn | Missense | Yes | P | |

| Sample 2 | GCK | NM_000162.3 | c.1279_1358delinsTTACA; p.Ser426_Ala454delinsLeuGln | Frameshift ≥ 10 bp | No | LP | PDX1: c.97C > T;p.Pro33Ser |

| Sample 3 | GCK | NM_000162.3 | c.1332_1333_dupGC; p.Ala378dup | Frameshift < 10 bp | Yes | LP | WFS1: c.2194C > T; p.Arg732Cys |

| Sample 4 | HNF1a | NM_000545.8 | c.1027_1029del2; p.Ser343fs74X | Frameshift < 10 bp | Yes | VUS | |

| Sample 5 | SLC5a2 | NM_003041.4 | c.1961A > G; p.Asn654Ser | Missense | Yes | VUS [11] | |

| Sample 7 | HNF1a | NM_000545.8 | c.872dupC;p.Pro291fsinsCys | Frameshift < 10 bp | No | P | |

| Sample 8 | KCNJ11 | NM_000525.3 | c.506 C > T; p.Met169Thr | Missense | Yes | P | |

| Sample 9 | ABCC8 | NM_000352.4 | c.4685delC; p.Pro1563del | Frameshift < 10 bp | Yes | LP | |

| Sample 11 | HNf1b | NM_000458.3 | c.226G > T; p.Gly76Cys (rs144425830) | Missense | Yes | B | |

| Sample 12 | GCK | NM_000162.3 | c.781G > A; p.Gly261Arg | Missense | Yes | P | |

| Sample 13 | GCK | NM_000162.3 | c.1379_*2del22; p.Ala460fs | Frameshift ≥ 10 bp | Yes | LP | |

| Sample 14 | WFS1 | NM_006005.3 | c.1338 C > A; p.Ser446Arg | Missense | Yes | VUS [12] | |

| Sample 16 | WFS1 | NM_006005.3 | c.319 G > C; p.Gly107Arg Hom | Missense | Yes | LP | |

| Sample 17 | ABCC8 | NM_000352.4 | c.916 C > T; p.Arg306Cys | Missense | Yes | VUS [13] | |

| Sample 18 | KCNJ11 | NM_000525.3 | c.601C > T; p.Arg201Cys | Missense | Yes | P | |

| Sample 20 | GCK | NM_000162.3 | c.579 G > T | Synonymous | Yes | LP | |

| Sample 21 | WFS1 | NM_006005.3 | c.1582 T > G; p. Tyr528Asp Hom | Missense | Yes | VUS [14] | |

| Sample 22 | WFS1 | NM_006005.3 | c.2106_2113del8nt; p.V644fs64X Hom | Frameshift < 10 bp | Yes | LP | HNF1a: c.481G > A; p.Ala161Thr |

| Sample 23 | WFS1 | NM_006005.3 | c.1523 A > G; p.Tyr508Cys Hom | Missense | Yes | LP | |

| Sample 25 | HNF1a | NM_000545.8 | c.262delG; p.Glu88fs | Frameshift < 10 bp | Yes | LP | |

| Sample 26 | SLC5a2 | NM_003041.4 | c.1261_1280dup19; p.Glu421_Arg427dup | Frameshift ≥ 10 bp | No | LP | |

| Sample 27 | GCK | NM_000162.3 | c.214G > A; p.Gly72Arg | Missense | c.214G > A; p.Gly72Arg | P | |

| Sample 28 | WFS1 | NM_006005.3 | c.1514G > A; p.Gys505Tyr c.1620_1622delGTG; p.Trp540_Cys541 | Missense Frameshift < 10 bp | c.1514G > A; p.Gys505Tyr c.1620_1622delGTG; p.Trp540_Cys541 | LP/ VUS [15] | |

| Sample 32 | GCK | NM_000162.3 | c.1234T > C; p.Ser412Pro | Missense | c.1234T > C; p.Ser412Pro | P | |

| Sample 33 | HNF1a | NM_000545.8 | c.1342_1374del, p.Val448_Thr458del | Frameshift ≥ 10 bp | Nd | VUS | |

| Sample 34 | SLC5a2 | NM_003041.4 | c.1566C > A; p.Cys522* Hom | Nonsense | c.1566C > A; p.Cys522* Hom | LP | |

| Sample 35 | GCK | NM_000162.3 | c.490delC; p.Leu164Phefs*40 | Frameshift < 10 bp | c.490delC; p.Leu164Phefs*40 | P | |

| Sample 36 | WFS1 | NM_006005.3 | c.1558C > T; p.Gln520* Het | Nonsense | c.1558C > T; p.Gln520* Het | P | |

| Sample 40 | GCK | NM_000162.3 | c.1302C > A; p.Cys434* | Nonsense | c.1302C > A; p.Cys434* | P | |

| Sample 44 | HNF1a | NM_000545.8 | c.1544C > T; p.Thr515Met | Missense | c.1544C > T; p.Thr515Met | VUS [16] | |

| Sample 45 | GCK | NM_000162.3 | c.1174C > T; p.Arg392Cys | Missense | c.1174C > T; p.Arg392Cys | P | |

| Sample 46 | GCK | NM_000162.3 | c.1352T > C; p.Leu451Pro | Missense | c.1544C > T; p.Thr515Met | LP |

| Performance Metric | Value (%) | Approach |

|---|---|---|

| Clinical sensitivity Missense | 100 | 17/17 detected |

| Clinical sensitivity Nonsense | 100 | 3/3 detected |

| Clinical sensitivity Frameshift ≥ 10 bp | 25 | 1/4 detected |

| Clinical sensitivity Frameshift < 10 bp | 87.5 | 7/8 detected |

| Synonymous | 100 | 1/1 detected |

| Patient Code | Gene | Transcript | Variants | Status | ACMG | Clin Var | dbSNP | gnomAD | Polyphen | Sift | Mut Taster | HGMD | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample 2 | PDX1 | NM_000209.4 | c.97 C > T; p.Pro33Ser | Het | VUS | VUS | rs192902098 | 0.00005625 | Poss D | D | D | No | No |

| Sample 3 | WFS1 | NM_006005.3 | c.2194C > T; p.Arg732Cys | Het | LP | VUS | rs71526458 | 0.00006092 | Prob D | D | D | No | No |

| Sample 22 | HNF1a | NM_000545.8 | c.481G > A; p.Ala161Thr | Het | VUS | VUS | rs201095611 | 0.00009549 | Poss D | D | D | CM981897 | Chevre (1998) Diabetologia 41, 1017 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Aloi, C.; Salina, A.; Caroli, F.; Bocciardi, R.; Tappino, B.; Bassi, M.; Minuto, N.; d’Annunzio, G.; Maghnie, M. Next Generation Sequencing (NGS) Target Approach for Undiagnosed Dysglycaemia. Life 2023, 13, 1080. https://doi.org/10.3390/life13051080

Aloi C, Salina A, Caroli F, Bocciardi R, Tappino B, Bassi M, Minuto N, d’Annunzio G, Maghnie M. Next Generation Sequencing (NGS) Target Approach for Undiagnosed Dysglycaemia. Life. 2023; 13(5):1080. https://doi.org/10.3390/life13051080

Chicago/Turabian StyleAloi, Concetta, Alessandro Salina, Francesco Caroli, Renata Bocciardi, Barbara Tappino, Marta Bassi, Nicola Minuto, Giuseppe d’Annunzio, and Mohamad Maghnie. 2023. "Next Generation Sequencing (NGS) Target Approach for Undiagnosed Dysglycaemia" Life 13, no. 5: 1080. https://doi.org/10.3390/life13051080

APA StyleAloi, C., Salina, A., Caroli, F., Bocciardi, R., Tappino, B., Bassi, M., Minuto, N., d’Annunzio, G., & Maghnie, M. (2023). Next Generation Sequencing (NGS) Target Approach for Undiagnosed Dysglycaemia. Life, 13(5), 1080. https://doi.org/10.3390/life13051080