3. Results

Pooling Set-up. We defined the following criteria for the test method to be developed: The method had to use inexpensive materials, including sterile, singly wrapped swabs and a sterile mixing container. The analytical procedure had to be based on a commercial, well established LFA system, and all steps had to be feasible without additional biochemical components and without the need for laboratory equipment. These criteria led to the system described here.

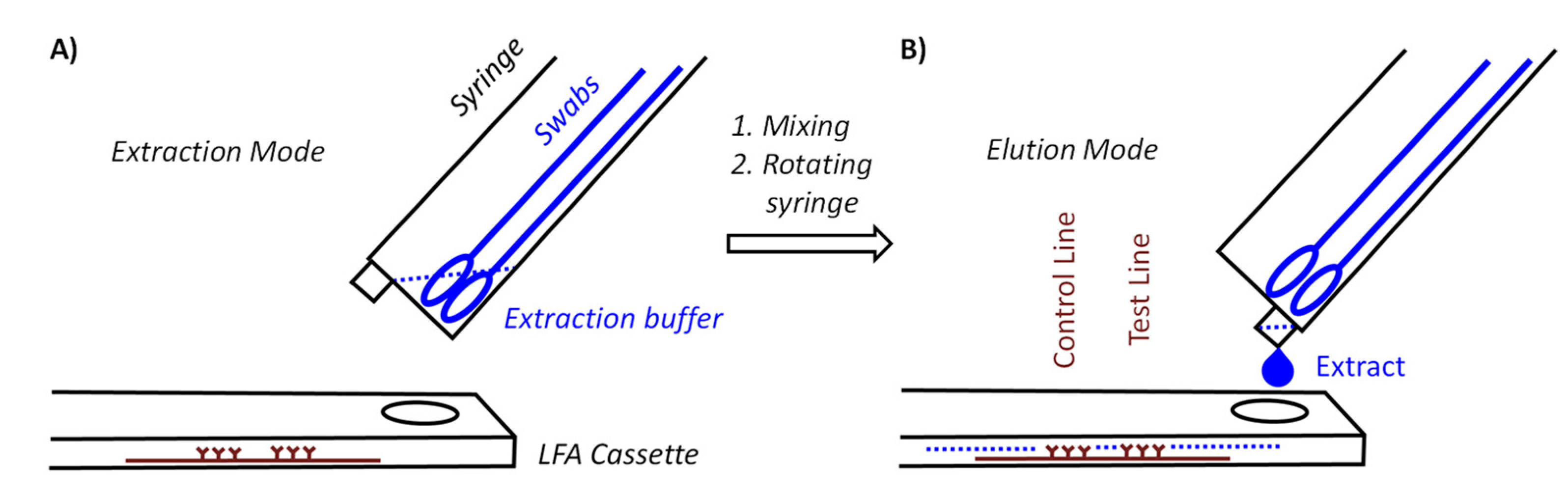

Figure 1 shows two core components of our device. One of those components is a syringe for medical use that functions as a container for the swabs and as vessel in which the mixing occurs. With the goal to achieve pooling for at least five specimens, we tested several syringe sizes and swabs and settled on 10 milliliter (mL) syringes with the central plunger removed as containers. They will hold approximately ten flocked nylon swabs of the type included in both the Abbott PanBio and the Roche rapid antigen tests or six conventional sterile flocked cotton swabs with wooden stem, without losing the mobility necessary for thorough mixing. The latter swabs cost a fraction of the nylon swabs, hold twice as much specimen, and are more pleasant when used in the mouth.

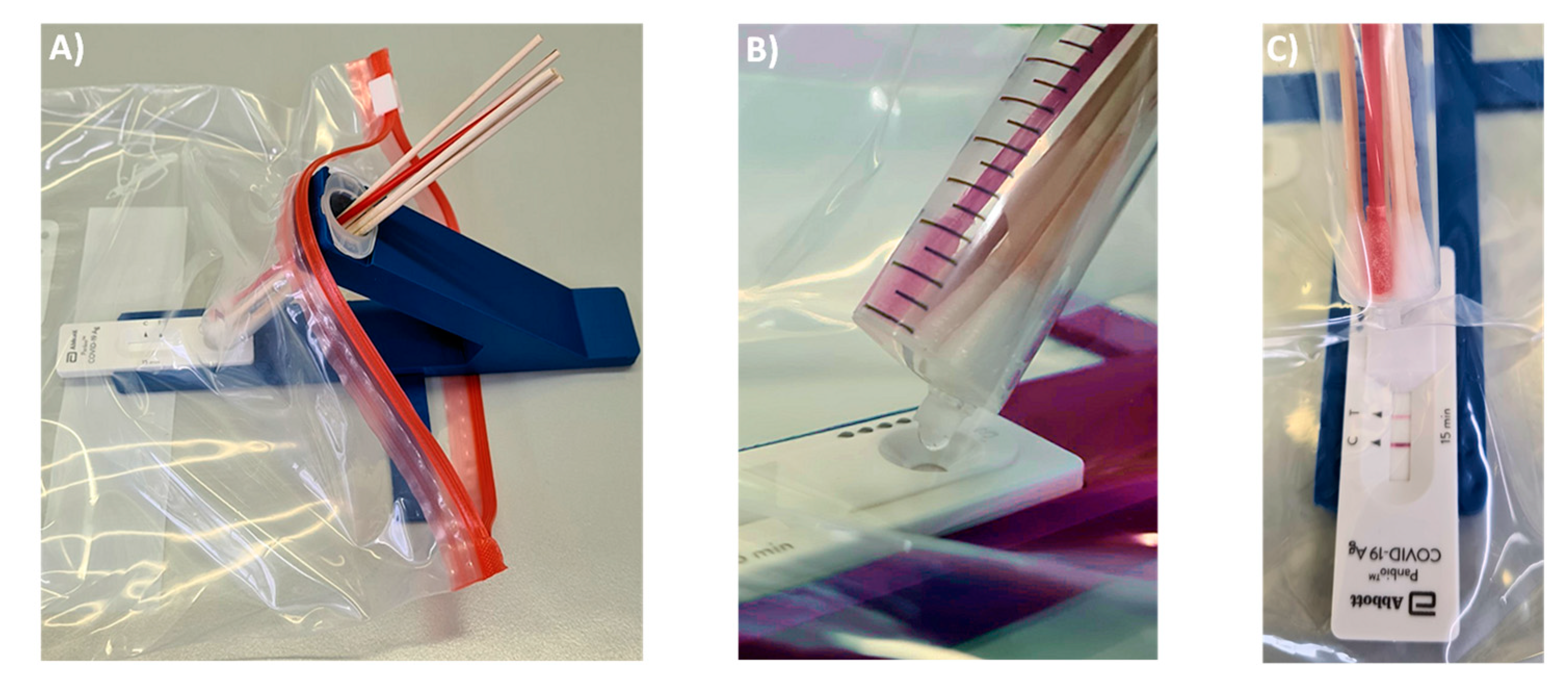

Figure 2 shows the holder of the device and the final form of the syringe, as employed in our current procedure. The holder shown in

Figure 2A has an arm with a circular opening for the syringe and indentations next to this opening that arrest the syringe in extraction or elution mode. The base of the holder has another indentation, where the LFA cassette is held in place. Further, there is a small indentation at the center bottom of the base plate, into which a stabilizing bar is pushed to provide mechanical stability to the assembly and to prevent it from tipping over during the extraction and elution steps. While initial prototypes were made of solid PVC, both the main holder and the stabilizing bar are now produced by us by 3D printing in an inexpensive printer. In our currently preferred method for testing, the holder is disinfected and recycled when the test outcome is negative but is disposed of when a test is positive. Our cost of the material for printing both holder and stabilizing bar is currently 1.54 €, so that the method is inexpensive, even if the holder is treated as a disposable item in each test with swab pooling.

One modification was made to the commercial 10 mL syringes used as container. Their LUER fit tip was pruned to avoid retention of a significant fraction of the extract in the form of the void volume of the device. Fully removing the tip led to uncontrolled elution and very large drops. Leaving the LUER opening unchanged retained too much of the valuable extract. The best performance was achieved with tips pruned to a length of 4 mm, as shown in

Figure 2B. With this size opening, the volume of 100 µL, which is required for the lateral flow assay to function properly, elute in three large drops that can be visually observed, even if the entire set-up is encapsulated in a transparent polypropylene bag (

Figure 3). We do the pruning of the tip with the blade of a carpet cutter, previously treated with disinfectant, while the syringe is in a steel holder (see

Supplementary Material), but pruning may also be performed in a simpler, hand-held fashion.

The syringe acting as container is held at a 40° angle to the LFA cassette. There are two positions for the syringe. In extraction mode, the LUER fit opening at the tip of the syringe is at its highest position to prevent premature leaking of the extract. Our preferred procedure involves self-sampling under the supervision of a medically trained member of the team (‘superuser’) undergoing pooled testing. The superuser sets up the device, drips the necessary volume of extraction buffer into the syringe, places the set-up in the transparent bag and supervises the collection of the specimens. Sampling occurs in a fume hood or well-ventilated area with a minimum distance of 3 m between individual team members and superuser. The members of the team enter their swabs into the container, one by one, wearing an inexpensive polyethylene glove on the hand with which they handle the swab, and the superuser, wearing medical-grade gloves and a surgical mask or FFP2 mask, then closes the bag and sprays it down with disinfectant from the outside. After a brief interval to allow for evaporation of the alcohol-based disinfectant, the superuser performs the extraction, elution and analysis while the entire set-up is inside the closed bag (

Figure 3).

Figure 3A shows how the extraction set-up is inserted into the sealable, transparent polyethylene bag of sufficient mechanical stability and optical transparency. Mixing is achieved by rotating and laterally moving the swabs immersed in the buffer for 3 min. This step requires some dexterity and experience to ensure that the extract is as homogeneous as possible. It is easier to perform this step with more liquid, but dilution lowers the concentration of the antigen and is therefore undesirable. After mixing, the syringe is switched into elution mode by rotating it 180°, so that the LUER fit is in its lowest position, allowing the extract to drip into the specimen well of the cassette. To ensure that the necessary volume is liberated, the swabs should be slightly moved up to avoid blockage of the exit port, and the swabs should be gently squeezed against the wall of the syringe. Again, this calls for dexterity and may be rehearsed without potentially infectious material first by operators new to the extraction device. It is also critical to perform the elution with close visual inspection to ensure that the necessary number of drops is applied.

Extraction and Analytical Assay. Pooling is expected to increase the total volume of the extract. To minimize the resulting loss in signal, the concentration of the antigen should be kept as high as possible. To achieve this, the analytical procedure was optimized. First, we gravimetrically determined the volume absorbed by swabs upon immersion in water for 5 s, with the aid of an analytical balance. We found that the NFS-1 flocked style nylon swabs provided with the Abbott test kit absorb 56.7 ± 3.0 µL under those conditions. Given the uncertainty of the viscosity of the real specimen, we refer to these swabs as ‘50 µL swabs’, assuming that they will take up approximately 50 µL specimen. The less expensive 5 mm cotton wool swabs with wooden stem take up 101.3 ± 4.1 µL of water under the same conditions, and we refer to those swabs as ‘100 µL swabs’.

We assumed that thorough mixing after pooling of the swabs produces a homogeneous liquid as extract. The total volume of this extract will be the sum of the volume of the extraction buffer employed and the volume entered with the specimens. Again, for simplicity, we assumed that the latter volume is either 50 µL or 100 µL per person participating in the pooled test. The standard protocol, as described in the user manual for the Abbott Panbio COVID-19 Ag Rapid Test, calls for 300 µL extraction buffer. The bottle provided with the test kit (25 tests) contains 9 mL or 360 µL per test. Assuming that leaving no more than a small residual volume in the buffer bottle is not critical, we used up to 350 µL extraction buffer per pooled test. We determined that this equals 13 drops from the Abbott bottle. Unless otherwise noted, one positive control swab was included in all laboratory assays as a constant source of antigen to be detected.

Figure 4 shows results from laboratory assays performed with our device, and

Table 1 lists the corresponding data numerically. The numerical values for signal intensities of the test (SARS-CoV-2 antigen) and control lines were obtained by analyzing photographs taken with the camera of a smartphone with the free software ImageJ, available from the National Institutes of Health, as detailed in the

Supplementary Information. The plots below each photograph of the read-out window of the test cassettes in

Figure 4 are the results of the integration of the gray value data calculated with ImageJ.

For the conventional, single-swab assay, run with the positive control swab alone, as recommended in the user manual of the Panbio Abbott test, the intensity of the test line was 86% of that found for the control line after 15 min assay time (

Figure 4A and entry 1 of

Table 1). Next, five 50 µL swabs with specimens from healthy volunteers among the authors plus the dry positive control swab were extracted with 350 µL of the extraction buffer (600 µL total volume, Vtot), a signal corresponding to 55% of that for the individual test was measured (entry 2 of

Table 1). This is the expected value, based on the approximately two-fold dilution.

We then performed an individual test with the Roche test, and found less signal (entry 3 of

Table 1). Visual inspection indicated an increase in intensity for the test line of the Roche test when allowed to develop longer than 15 min. This prompted us to collect a series of images over time in order to obtain the kinetics of colloid binding to the test line. The results for the Abbott and the Roche test are shown in

Figure 5. The signal for the SARS-CoV-2 antigen did indeed rise more slowly for the latter assay, and even after 30 min (the upper time limit for read-out specified by the manufacturer), the value was below that for the PanBio test (entry 4,

Table 1). Since rapid testing is desirable, we decided to focus on the Abbott test in all subsequent work.

We next studied how dilution affects the signal in the lateral flow test. For this, we switched to the 100 µL swabs, which have a larger capacity and thus the potential to compensate for dilution. Only the positive control swab was left unchanged, as no larger volume version of this was available to us. In the first set of experiments, we used wet 100 µL swabs, pre-hydrated with sterile water and an extraction buffer diluted two-fold with the same water. This gave 37% of the control signal, i.e., considerably more than the 27% expected based on the estimated dilution factor but was not pursued further over concerns that the dilution may change the characteristics of the extraction medium [

10] and that the extra cost (and effort) to provide individual sterile vials with dilution water to each participant would become prohibitive. Still, it is an interesting finding, as it suggests stronger binding of the antigen-loaded gold nanoparticles to the surface-immobilized antibodies in medium with lower ionic strength than in standard medium. Our previous studies with DNA-coated gold nanoparticles on other surfaces [

18,

19] gave the opposite effect when lowering the salt concentration, which may be due to the different biopolymers involved and characteristics of the corresponding molecular recognition events. There was also the possibility that the signal may not increase linearly with concentration due to multivalency effects, [

20] which motivated dilution experiments (vide infra).

In experiments performed with dry 100 µL swabs, we noted that incomplete hydration during sample collection occasionally led to difficulties in obtaining sufficient extract to apply to the test cassette. Therefore, we adopted a procedure starting with wetting the swabs with saliva for 30 s, followed by oro- and nasopharyngeal sampling. The saliva makes nasopharyngeal sampling less painful and avoids that partially wetted swabs take up too much of the buffer solution. The combined oro- and nasopharyngeal sampling is similar to what is typically done with smaller, dry swabs when collecting specimen for PCR tests. Our procedure that involves saliva plus specimen collected by swabbing is in agreement with the recommendations of a study with 659 patients that employed the Panbio test and that showed high sensitivity for the combination of saliva and nasal sampling [

21]. The ability to detect infections with saliva was also confirmed by others [

22,

23]. Using this approach for sampling, combined with the 350 µL of extraction buffer available from the test kit, the 100 µL extract necessary for running the lateral flow assay was obtained without the need for any additional fluid. We considered this the optimal procedure under our conditions and opted for six-fold pooling with 100 µL swabs as our preferred mode of performing pooled tests.

When the optimized team test was performed eight times with samples from volunteers among the authors, we obtained a signal intensity of 43 ± 6% (mean ± one SD) of that for the single swab standard procedure (entry No. 6,

Table 1). A negative control swab or six specimen-holding swabs from healthy, negatively tested volunteers gave no detectable signal (entry 7 of

Table 1). We then performed exploratory experiments to determine the limit of detection. For this, the extract from an assay performed as for entry 6 of

Table 1, was diluted with extraction buffer in 1:2 dilution steps, resulting in extracts with 2-, 4-, 8-, 16-, and 32-fold lower antigen concentration (entries 8–12,

Table 1). Even for the most dilute extract, a positive result was detectable when using image analysis after photography, with a signal-to-noise ratio of approximately 2:1 (

Figure 4F). Zooming in on the baseline of the negative control assay did not show maxima of similar intensity (

Figure 4G).

A quantitative analysis of the results of the kinetics study with a monoexponential model, using the software Origin Pro, version 8.0, gave the numerical data presented in the boxes of

Figure 5. Except for the control line of the Abbott test, where almost full signal intensity had been reached at the starting point of data collection, satisfactory fits were obtained with this simplified model of colloid binding (R

2 values > 0.97). The apparent rate constant of binding (k

app) was found to be approximately 2.5-fold larger for the Abbott test than for the Roche test. The absolute value of the maximum signal intensity was found to be 1.17-fold higher for the Abbott test versus the Roche test. The calculated relative signal intensity (test versus control line) at infinite time was determined as 0.79 for the Abbott test and 0.63 for the Roche test, confirming the conclusions from the initial qualitative analysis mentioned above.

We then asked whether the effect of dilution is predictable. For this, we decided to plot the relative signal (test versus control strip) from the dilution series against the relative concentration of the antigen. The relative concentration was calculated from the total volume of the initial extract and subsequent dilution steps and expressed as a percentage of the concentration in the standard extract of the positive control swab. A linear correlation with an R

2 value of 0.98 was found (

Figure 6).

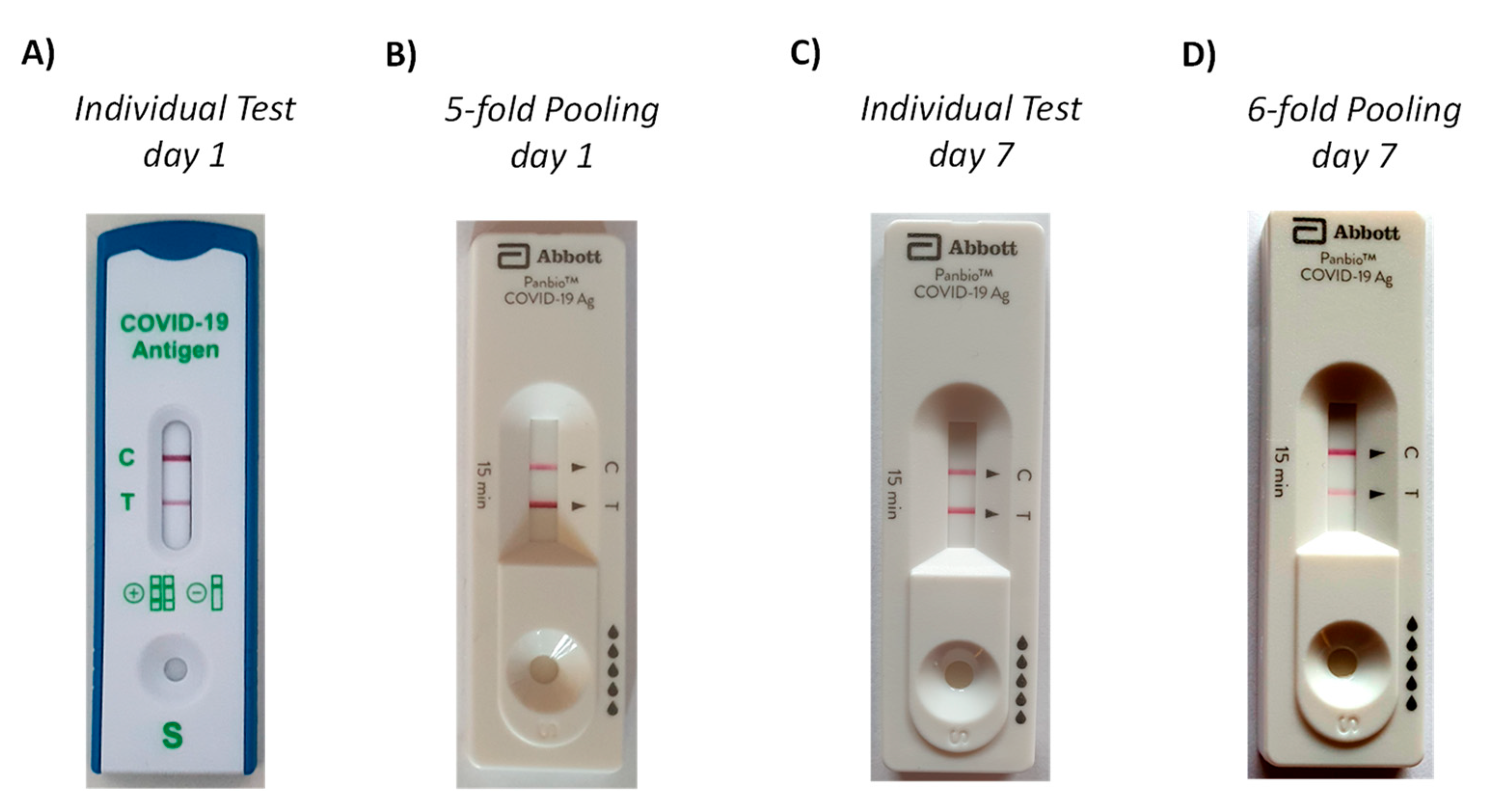

A full clinical validation was beyond the scope of our study. However, a SARS-CoV-2 infection among the authors (unrelated to our experiments) provided the data for a case study. Upon onset of symptoms, a commercial rapid antigen test (Lyher Covid-19 Antigen Rapid test) was performed that gave a positive result (

Figure 7A). While the symptoms were increasing, a test with 5-fold pooling (four from a healthy volunteer among the authors, one from the patient) was then run approximately 5 h after the initial test. This test employed the Abbott PanBio cassette and our extraction device and gave a strong positive signal, despite the pooling (

Figure 7B). The patient underwent PCR testing with NSP swab collection of specimens by health care professionals on the subsequent day, confirming the COVID-19 diagnosis. Seven days after the onset of symptoms and the first rapid antigen tests, a second set of tests was run. This time, both the individual and the pooled test employed the Abbott Panbio system. Both specimens were taken from the same nostril, with the first swab for the individual test being applied immediately prior to that for the pooled test, which employed five swabs from the same healthy volunteer as in the 5-fold pooling assay run earlier. As expected, the individual test (

Figure 7C) gave a stronger signal than the pooled test (

Figure 7D), and a clear positive signal was obtained in either case. The patient was free of symptoms after ten days, and an individual test run at this time point with another commercial test gave little signal. All photographs were taken at the point of care, without an attempt to control the illumination of the test cassettes, unlike the laboratory experiments described above. As expected for different tests systems and regimes of this ad hoc validation, there are quantitative differences between individual and pooled tests. Importantly, unambiguously positive signals were obtained in either of the tests with swab pooling.

Finally, we performed a pilot project in a laboratory course at the University of Stuttgart. For this, groups of five or six persons were assigned, including students (master program) and teaching assistants and/or faculty members. Written consent was obtained from all participants, and each team performed two tests per week for the duration of the three-week course. Each participant was issued one swab on the day of testing. All tests used the settings of entry 6 of

Table 1. The results are compiled in chapter 4 of the

Supplementary Material. No false positive results were obtained, and the protocol was deemed suitable for practical courses at institutions of higher learning by the participants.

4. Discussion

Our data indicate that swab pooling in a device is a valid option for routine monitoring in settings where the available resources limit the frequent use of individual lateral flow tests. We note that the results of

Table 1 should be regarded as the lower limit of the signal we expect for a positive specimen in real life monitoring set-ups. The positive control swab from Abbott is designed for an assay with 50 µL swabs, but 100 µL swabs are employed in our preferred tests with swab pooling. So, while the total volume has gone up approximately three-fold with six-fold pooling, the amount of specimen is increasing approximately two-fold over that of the standard swab, resulting in a numerical decrease in concentration of antigens by a factor of 1.5 only.

In our current testing regime, the operators of the team test obtained a 90 min in-person training by a health care professional on the use of rapid antigen tests (Roche). In house-training on the use of our device for pooling and analysis, as well as data analysis, took another 60 min. Instructing the team members without operator status and obtaining informed consent required approximately 30 min, so that the overall time effort is limited. The recommended conditions for testing (temperature, humidity etc.) are not different from those recommended by the manufacturer of the test cassette and should be obtained from the manuals of respective tests.

Even though only fluids intended by the original procedure are being used, a validation of the pooling in a full clinical study or field study is required. Assuming that this validation will confirm the results of our exploratory experiments, a ‘team test’ approach may facilitate surveillance for viral infections at approximately five-fold reduced costs at the six-fold pooling level. In an in-house validation, we experience better compliance with a twice weekly voluntary test regime when testing was performed as a team test than with individual tests requiring medical appointments. For ordinary team members, the time effort is well below 5 min per test, and the effort of the ‘superuser’ is approximately 30 min per team test, 15 min of which is waiting time for the test to develop. The ability to run the tests at the workplace with low set-up costs and minimized infection risk due to encapsulation, as well as the self-sampling option, contribute to the attractiveness of the pooling approach. Follow-up in positive cases should be done with more sensitive methods, such as RT-PCR, and negative results should not be the basis for medical decisions or a reduction or protective measures, such as mask wearing. In our laboratories, we agreed on the following measures. When a team test gives a positive result, all members of the team leave the premises and self-isolate until they have undergone individual tests at an official testing site or clinic. The encapsulated test set-up, including the holder, are thoroughly disinfected from the outside and disposed of as mandated by local regulations for infectious material.

The goal of monitoring is to detect infectious individuals early, using a process that is sustainable, both financially and in terms of the time effort involved. The manual of the Panbio test states that it has a detection limit of 2.5 × 101.8 TCID50 of SARS-CoV-2 and a sensitivity of 94.1% ‘with samples of Ct values ≤ 33’. Data from an early study [

7], as well as data from a more recent field study [

24], indicate that the Abbott Panbio rapid antigen test reliably detects ≥ 90% of individuals with a viral load corresponding to a Ct value of ≥ 28. A multicenter study found a sensitivity of 95.8% for Ct values below 25 when testing within the first 7 days after onset of symptoms [

25]. A viral load of Ct > 28 is at the upper limit of what is believed to make a person infectious [

7,

9,

26,

27]. Therefore, we have reason to believe that the approximately two-fold drop in sensitivity observed for six-fold pooling keeps the detection limit within the range that successfully identifies active spreaders of the SARS-CoV-2 virus, particularly when combined with the gain in sensitivity that can be achieved with image analysis. We expect the uncertainty associated with sampling by oro- and nasopharyngeal swab probing to be reduced when including saliva, as in our preferred procedure. The uncertainty may be reduced further with improvements over standard swabs [

28] or extraction buffer composition, as discussed for tests detecting nucleic acids [

29]. We note that our procedure deviates from that recommended by Abbott and that a clinical study is planned to obtain more robust data from outbreaks of COVID-19. With such data, it will be easier to provide more safety to families, work teams, musicians, and other groups threatened with the spread of viral infections through frequent testing with swab pooling.