Evaluation of a Bi-Analyte Immunoblot as a Useful Tool for Diagnosing Dermatitis Herpetiformis

Abstract

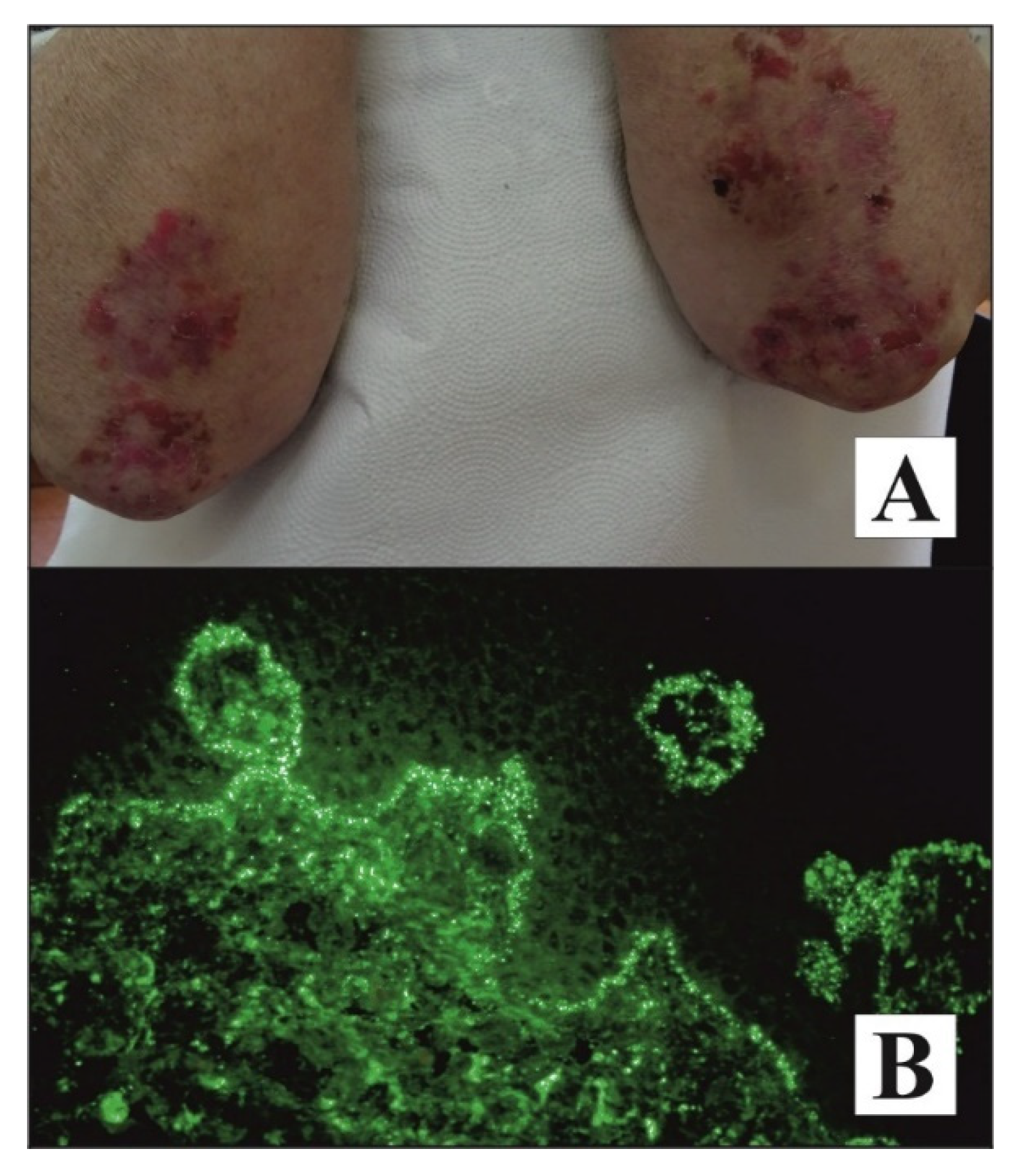

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Patients and Serum Samples

2.2. ELISA

2.3. Bi-Analyte Immunoblot Analysis

2.4. Direct Immunofluorescence and Microscopic Examination

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Szondy, Z.; Korponay-Szabó, I.; Kiraly, R.; Sarang, Z.; Tsay, G.J. Transglutaminase 2 in human diseases. BioMedicine 2017, 7, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kárpáti, S.; Sárdy, M.; Németh, K.; Mayer, B.; Smyth, N.; Paulsson, M.; Traupe, H. Transglutaminases in autoimmune and inherited skin diseases: The phenomena of epitope spreading and functional compensation. Exp. Dermatol. 2018, 27, 807–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lorand, L.; Iismaa, S.E. Transglutaminase diseases: From biochemistry to the bedside. FASEB J. 2019, 33, 4653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Kellems, R.E.; Xia, Y. Inflammation, Autoimmunity, and Hypertension: The Essential Role of Tissue Transglutaminase. Am. J. Hypertens. 2017, 30, 756–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ress, K.; Teesalu, K.; Annus, T.; Putnik, U.; Lepik, K.; Luts, K.; Uibo, O.; Uibo, R. Low prevalence of IgA anti-transglutaminase 1, 2, and 3 autoantibodies in children with atopic dermatitis. BMC Res. Notes 2014, 7, 310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Cascella, N.G.; Santora, D.; Gregory, P.; Kelly, D.L.; Fasano, A.; Eaton, W.W. Increased Prevalence of Transglutaminase 6 Antibodies in Sera from Schizophrenia Patients. Schizophr. Bull. 2012, 39, 867–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teshima, H.; Kato, M.; Tatsukawa, H.; Hitomi, K. Analysis of the expression of transglutaminases in the reconstructed human epidermis using a three-dimensional cell culture. Anal. Biochem. 2020, 603, 113606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gornowicz-Porowska, J.; Bowszyc-Dmochowska, M.; Dmochowski, M. Autoimmunity-driven enzymatic remodeling of the dermal–epidermal junction in bullous pemphigoid and dermatitis herpetiformis. Autoimmunity 2011, 45, 71–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antiga, E.; Maglie, R.; Quintarelli, L.; Verdelli, A.; Bonciani, D.; Bonciolini, V.; Caproni, M. Dermatitis herpetiformis: Novel perspectives. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 1290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gornowicz-Porowska, J.; Bowszyc-Dmochowska, M.; Seraszek-Jaros, A.; Kaczmarek, E.; Dmochowski, M. Association between Levels of IgA Antibodies to Tissue Transglutaminase and Gliadin-Related Nonapeptides in Dermatitis Herpetiformis. Sci. World J. 2012, 2012, 363296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reunala, T.; Salmi, T.; Hervonen, K. Dermatitis Herpetiformis: Pathognomonic Transglutaminase IgA Deposits in the Skin and Excellent Prognosis on a Gluten-free Diet. Acta Derm. Venereol. 2015, 95, 917–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonciani, D.; Verdelli, A.; Bonciolini, V.; D’Errico, A.; Antiga, E.; Fabbri, P.; Caproni, M. Dermatitis Herpetiformis: From the Genetics to the Development of Skin Lesions. Clin. Dev. Immunol. 2012, 2012, 239691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koskinen, L.L.; Korponay-Szabo, I.R.; Viiri, K.; Juuti-Uusitalo, K.; Kaukinen, K.; Lindfors, K.; Mustalahti, K.; Kurppa, K.; Adány, R.; Pocsai, Z.; et al. Myosin IXB gene region and gluten intolerance: Linkage to coeliac disease and a putative dermatitis herpetiformis association. J. Med. Genet. 2008, 45, 222–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duś, M.; Gornowicz, J.; Dmochowski, M. Transient manifestation of dermatitis herpetiformis in a female with familial predisposition induced by propafenone. Postepy Dermatol. Alergol. 2009, 26, 239–242. [Google Scholar]

- Dmochowski, M.; Gornowicz-Porowska, J.; Bowszyc-Dmochowska, M. An update on direct immunofluorescence for diagnosing dermatitis herpetiformis. Adv. Dermatol. Allergol. 2019, 36, 655–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bresler, S.C.; Granter, S.R. Utility of Direct Immunofluorescence Testing for IgA in Patients with High and Low Clinical Suspicion for Dermatitis Herpetiformis. Am. J. Clin. Pathol. 2015, 144, 880–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hull, C.; Liddle, M.; Hansen, N.; Meyer, L.; Schmidt, L.; Taylor, T.; Jaskowski, T.; Hill, H.; Zone, J. Elevation of IgA anti-epidermal transglutaminase antibodies in dermatitis herpetiformis. Br. J. Dermatol. 2008, 159, 120–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valencia-Guerrero, A.; Dresser, K.; Cornejo, K.M. The utility of tissue and epidermal transglutaminase immunohistochemistry in dermatitis herpetiformis. Indian J. Dermatopath Diagn Dermatol. 2018, 5, 97. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, V.; Jarzabek-Chorzelska, M.; Sulej, J.; Rajadhyaksha, M.; Jablonska, S. Tissue transglutaminase and endomysial antibodies-diagnostic markers of gluten-sensitive enteropathy in dermatitis herpetiformis. Clin. Immunol. 2001, 98, 378–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sankari, H.; Hietikko, M.; Kurppa, K.; Kaukinen, K.; Mansikka, E.; Huhtala, H.; Laurila, K.; Reunala, T.; Hervonen, K.; Salmi, T.; et al. Intestinal TG3- and TG2-Specific Plasma Cell Responses in Dermatitis Herpetiformis Patients Undergoing a Gluten Challenge. Nutrients 2020, 12, 467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, C.; Dieterich, W.; Bröcker, E.-B.; Schuppan, D.; Zillikens, D. Circulating autoantibodies to tissue transglutaminase differentiate patients with dermatitis herpetiformis from those with linear IgA disease. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 1999, 41, 957–961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salmi, T.T. Dermatitis herpetiformis. Clin. Exp. Dermatol. 2019, 44, 728–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasperkiewicz, M.; Dähnrich, C.; Probst, C.; Komorowski, L.; Stöcker, W.; Schlumberger, W.; Zillikens, D.; Rose, C. Novel assay for detecting celiac disease-associated autoantibodies in dermatitis herpetiformis using deamidated gliadin-analogous fusion peptides. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2012, 66, 583–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GGornowicz-Porowska, J.; Seraszek-Jaros, A.; Bowszyc-Dmochowska, M.; Kaczmarek, E.; Pietkiewicz, P.; Bartkiewicz, P.; Dmochowski, M. Accuracy of molecular diagnostics in pemphigus and bullous pemphigoid: Comparison of commercial and modified mosaic indirect immunofluorescence tests as well as enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays. Adv. Dermatol. Allergol. 2017, 34, 21–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrell, J.; Rubio, X.B.; Nielson, C.; Hsu, S.; Motaparthi, K. Advances in the diagnosis of autoimmune bullous dermatoses. Clin. Dermatol. 2019, 37, 692–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, A.L.; Dhanapala, L.; Kankanamage, R.N.T.; Kumar, C.V.; Rusling, J.F. Multiplexed Immunosensors and Immunoarrays. Anal. Chem. 2020, 92, 345–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heyman, M.; Ménard, S. Pathways of Gliadin Transport in Celiac Disease. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2009, 1165, 274–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gornowicz-Porowska, J.; Seraszek-Jaros, A.; Bowszyc-Dmochowska, M.; Kaczmarek, E.; Dmochowski, M. Immunoexpression of IgA receptors (CD89, CD71) in dermatitis herpetiformis. Folia Histochem. Cytobiol. 2018, 55, 212–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gornowicz-Porowska, J.; Seraszek-Jaros, A.; Bowszyc-Dmochowska, M.; Kaczmarek, E.; Pietkiewicz, P.; Bartkiewicz, P.; Dmochowski, M. A comparative study of expression of Fc receptors in relation to the autoantibody-mediated immune response and neutrophil elastase expression in autoimmune blistering dermatoses. Pol. J. Pathol. 2017, 2, 109–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonciolini, V.; Bonciani, D.; Verdelli, A.; D’Errico, A.; Antiga, E.; Fabbri, P.; Caproni, M. Newly described clinical and immunopathological feature of dermatitis herpetiformis. Clin. Dev. Immunol. 2012, 2012, 967974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antiga, E.; Bonciolini, V.; Cazzaniga, S.; Alaibac, M.; Calabrò, A.S.; Cardinali, C.; Cozzani, E.; Marzano, A.V.; Micali, G.; Not, T.; et al. Female Patients with Dermatitis Herpetiformis Show a Reduced Diagnostic Delay and Have Higher Sensitivity Rates at Autoantibody Testing for Celiac Disease. BioMed Res. Int. 2019, 2019, 6307035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gasparini, G.; Cozzani, E.; Caproni, M.; Antiga, E.; Signori, A.; Parodi, A. Could anti-glycan antibodies be useful in dermatitis herpetiformis? Eur. J. Dermatol. 2019, 29, 322–323. [Google Scholar]

- Beutner, E.H.; Baughman, R.D.; Austin, B.M.; Plunkett, R.W.; Binder, W.L. A case of dermatitis herpetiformis with IgA endomysial antibodies but negative direct immunofluorescence findings. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2000, 43, 329–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reunala, T.; Salmi, T.T.; Hervonen, K.; Kaukinen, K.; Collin, P. Dermatitis Herpetiformis: A Common Extraintestinal Manifestation of Coeliac Disease. Nutrients 2018, 10, 602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansikka, E.; Salmi, T.; Kaukinen, K.; Collin, P.; Huhtala, H.; Reunala, T.; Hervonen, K. Diagnostic Delay in Dermatitis Herpetiformis in a High-prevalence Area. Acta Derm. Venereol. 2018, 98, 195–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziberna, F.; Sblattero, D.; Lega, S.; Stefani, C.; Dal Ferro, M.; Marano, F.; Gaita, B.; De Leo, L.; Vatta, S.; Berti, I.; et al. A novel quantitative ELISA as accurate and reproducible tool to detect epidermal transglutaminase antibodies in patients with Dermatitis Herpetiformis. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2021, 35, e78–e80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marietta, E.V.; Camilleri, M.J.; Castro, L.A.; Krause, P.K.; Pittelkow, M.R.; Murray, J.A. Transglutaminase Autoantibodies in Dermatitis Herpetiformis and Celiac Sprue. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2008, 128, 332–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dieterich, W.; Schuppan, D.; Laag, E.; Bruckner-Tuderman, L.; Reunala, T.; Kárpáti, S.; Zágoni, T.; Riecken, E.O. Antibodies to Tissue Transglutaminase as Serologic Markers in Patients with Dermatitis Herpetiformis. J. Investig. Dermatol. 1999, 113, 133–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clarindo, M.V.; Possebon, A.T.; Soligo, E.M.; Uyeda, H.; Ruaro, R.T.; Empinotti, J.C. Dermatitis herpetiformis: Pathophysiology, clinical presentation, diagnosis and treatment. An. Bras. Dermatol. 2014, 89, 865–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Desai, A.M.; Krishnan, R.S.; Hsu, S. Medical Pearl: Using tissue transglutaminase antibodies to diagnose dermatitis herpetiformis. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2005, 53, 867–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendes, F.B.R.; Hissa-Elian, A.; De Abreu, M.A.M.M.; Gonçalves, V.S. Review: Dermatitis herpetiformis. An. Bras. Dermatol. 2013, 88, 594–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sousa, L.; Bajanca, R.; Cabral, J.; Fiadeiro, T. Dematitis herpetiformis: Should direct immunofluorescence be the only diagnostic criterion? Pediatr. Dermatol. 2002, 19, 336–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caproni, M.; Antiga, E.; Melani, L.; Fabbri, P.; The Italian Group for Cutaneous Immunopathology. Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of dermatitis herpetiformis. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2009, 23, 633–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lutkowska, A.; Pietkiewicz, P.; Sulczyńska-Gabor, J.; Gornowicz, J.; Bowszyc-Dmochowska, M.; Dmochowski, M. Gluteal skin is not an optimal biopsy site for direct immunofluorescence in diagnostics of dermatitis herpetiformis. A report of a case of dermatitis herpetiformis Cottini. Dermatol. Klin. 2009, 1, 31–33. [Google Scholar]

- Zone, J.J.; Meyer, L.J.; Petersen, M.J. Deposition of granular IgA relative to clinical lesions in dermatitis herpetiformis. Arch. Dermatol. 1996, 132, 912–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beutner, E.H.; Plunkett, R.W. Methods for diagnosing dermatitis herpetiformis. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2006, 55, 1112–1113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wojnarowska, F.; Delacroix, D.; Gengoux, P. Cutaneous IgA subclasses in dermatitis herpetiformis and linear IgA disease. J. Cutan. Pathol. 1988, 15, 272–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Antiga, E.; Maglie, R.; Lami, G.; Tozzi, A.; Bonciolini, V.; Calella, F.; Bianchi, B.; Bianco, E.; Renzi, D.; Mazzarese, E.; et al. Granular Deposits of IgA in the Skin of Coeliac Patients without Dermatitis Herpetiformis: A Prospective Multicentric Analysis. Acta Derm. Venereol. 2021, 101, adv00382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakazawa, H.; Makishima, H.; Ito, T.; Ota, H.; Momose, K.; Sekiguchi, N.; Yoshizawa, K.; Akamatsu, T.; Ishida, F. Screening Tests Using Serum Tissue Transglutaminase IgA May Facilitate the Identification of Undiagnosed Celiac Disease among Japanese Population. Int. J. Med. Sci. 2014, 11, 819–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Lerner, A.; Berthelot, L.; Jeremias, P.; Matthias, T.; Abbad, L.; Monteiro, R.C. Gluten, Transglutaminase, Celiac Disease and IgA Nephropathy. J. Clin. Cell. Immunol. 2017, 8, 499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antiga, E.; Caproni, M. The diagnosis and treatment of dermatitis herpetiformis. Clin. Cosmet. Investig. Dermatol. 2015, 8, 257–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skręta-Śliwińska, M.; Woźniacka, A.; Żebrowska, A. Haemorrhagic form of dermatitis herpetiformis. Dermatol. Rev. 2020, 107, 69–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verdelli, A.; Corrà, A.; Caproni, M. Reply letter to “An update on direct immunofluorescence for diagnosing dermatitis herpetiformis”. Could granular C3 deposits at the dermal epidermal junction be considered a marker of “cutaneous gluten sensitivity”? Postępy Dermatol. Alergol. 2021, 38, 346–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Görög, A.; Antiga, E.; Caproni, M.; Cianchini, G.; De, D.; Dmochowski, M.; Dolinsek, J.; Drenovska, K.; Feliciani, C.; Hervonen, K.; et al. S2k guidelines (consensus statement) for diagnosis and therapy of dermatitis herpetiformis initiated by the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology (EADV). J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2021, 35, 1251–1277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Parameter | DH Group | Control Group (Healthy Subjects) |

|---|---|---|

| Number of patients | 31 | 24 |

| Sex | 17 F; 14 M | 15 F; 9 M |

| Mean age ± SD (min; max) | 40.00 ± 19.65 (9; 80) | 36.58 ± 10.12 (27; 65) |

| ELISA score (RU/mL) | ||

| Anti-tTG IgA (mean ± SD) | 134.99 ± 85.12 | 2.35 ± 1.58 |

| DH DIF-Positive Subgroup (n = 27) | DH DIF-Negative Subgroup (n = 4) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parameter | Results | ||||

| Positive (n) | Negative (n) | Positive (n) | Negative (n) | ||

| ELISA | anti-tTG IgA | 23 | 4 | 4 | 0 |

| Bi-analyte immunoblot | anti-tTG IgA | 17 | 10 | 4 | 0 |

| anti-npG IgA | 23 | 4 | 4 | 0 | |

| Parameters | Subjects (n) | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) | PPV (%) | NPV (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| tTG bi-analyte immunoblot vs. tTG ELISA | 55 | 78 | 100 | 100 | 82 |

| npG bi-analyte immunoblot vs. tTG ELISA | 55 | 93 | 93 | 93 | 93 |

| npG bi-analyte immunoblot vs. tTG bi-analyte immunoblot | 55 | 100 | 82 | 78 | 100 |

| Parameters | Cohen’s Kappa Values |

|---|---|

| tTG bi-analyte immunoblot vs. tTG ELISA | 0.78 |

| npG bi-analyte immunoblot vs. tTG ELISA | 0.85 |

| npG bi-analyte immunoblot vs. tTG bi-analyte immunoblot | 0.78 |

| Parameters | Cohen’s Kappa Values |

|---|---|

| tTG bi-analyte immunoblot vs. DIF | −0.23 |

| tTG ELISA vs. DIF | −0.15 |

| npGbi-analyte immunoblot vs. DIF | −0.15 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gornowicz-Porowska, J.; Seraszek-Jaros, A.; Jałowska, M.; Bowszyc-Dmochowska, M.; Kaczmarek, E.; Dmochowski, M. Evaluation of a Bi-Analyte Immunoblot as a Useful Tool for Diagnosing Dermatitis Herpetiformis. Diagnostics 2021, 11, 1414. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics11081414

Gornowicz-Porowska J, Seraszek-Jaros A, Jałowska M, Bowszyc-Dmochowska M, Kaczmarek E, Dmochowski M. Evaluation of a Bi-Analyte Immunoblot as a Useful Tool for Diagnosing Dermatitis Herpetiformis. Diagnostics. 2021; 11(8):1414. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics11081414

Chicago/Turabian StyleGornowicz-Porowska, Justyna, Agnieszka Seraszek-Jaros, Magdalena Jałowska, Monika Bowszyc-Dmochowska, Elżbieta Kaczmarek, and Marian Dmochowski. 2021. "Evaluation of a Bi-Analyte Immunoblot as a Useful Tool for Diagnosing Dermatitis Herpetiformis" Diagnostics 11, no. 8: 1414. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics11081414

APA StyleGornowicz-Porowska, J., Seraszek-Jaros, A., Jałowska, M., Bowszyc-Dmochowska, M., Kaczmarek, E., & Dmochowski, M. (2021). Evaluation of a Bi-Analyte Immunoblot as a Useful Tool for Diagnosing Dermatitis Herpetiformis. Diagnostics, 11(8), 1414. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics11081414