Pelvic Exenteration in Advanced, Recurrent or Synchronous Cancers—Last Resort or Therapeutic Option?

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Preoperative Management of Patients

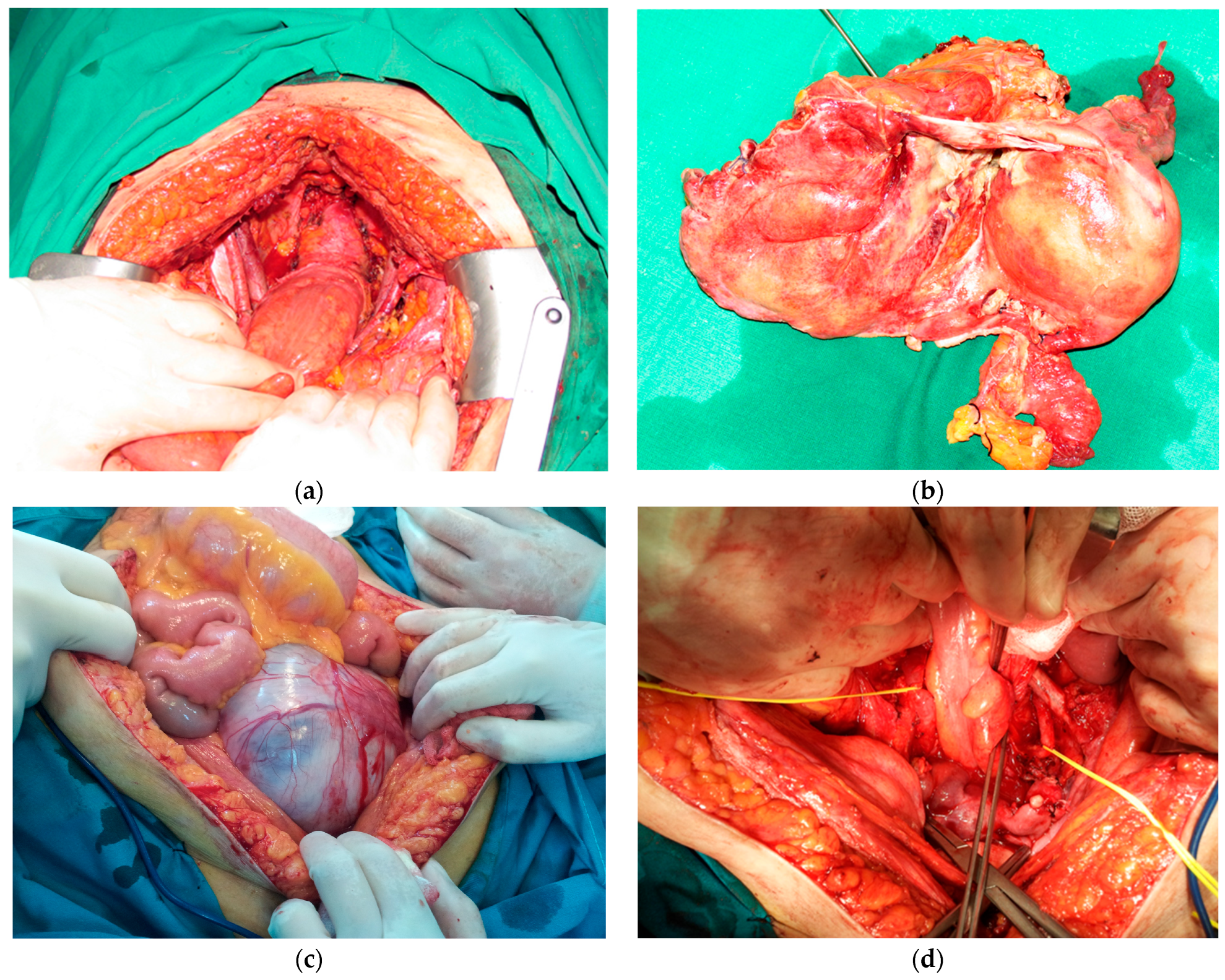

2.2. Surgery

2.3. Postoperative Follow-Up

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

Strengths, Limitations and Future Directions of Study

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Brunschwig, A. Complete excision of pelvic viscera for advanced carcinoma.A one-stage abdominoperineal operation with end colostomy and bilateral ureteral implantation into the colon above the colostomy. Cancer 1948, 1, 177–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, J.E.; Howe, C.W. Complete Pelvic Evisceration in the Male for Complicated Carcinoma of the Rectum. N. Engl. J. Med. 1950, 242, 83–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simion, L.; Rotaru, V.; Cirimbei, C.; Gales, L.; Stefan, D.-C.; Ionescu, S.-O.; Luca, D.; Doran, H.; Chitoran, E. Inequities in Screening and HPV Vaccination Programs and Their Impact on Cervical Cancer Statistics in Romania. Diagnostics 2023, 13, 2776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Gregorio, N.; de Gregorio, A.; Ebner, F.; Friedl, T.W.P.; Huober, J.; Hefty, R.; Wittau, M.; Janni, W.; Widschwendter, P. Pelvic exenteration as ultimate ratio for gynecologic cancers: Single-center analyses of 37 cases. Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 2019, 300, 161–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bacalbasa, N.; Balescu, I.; Vilcu, M.; Neacsu, A.; Dima, S.; Croitoru, A.; Brezean, I. Pelvic Exenteration for Locally Advanced and Relapsed Pelvic Malignancies—An Analysis of 100 Cases. In Vivo 2019, 33, 2205–2210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spratt, J.S.; Watson, F.R.; Pratt, J.L. Characteristics of Variants of Colorectal Carcinoma That Do Not Metastasize to Lymph Nodes. Dis. Colon Rectum 1970, 13, 243–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bricker, E.M. Bladder Substitution After Pelvic Evisceration. Surg. Clin. N. Am. 1950, 30, 1511–1521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voinea, S.C.; Bordea, C.I.; Chitoran, E.; Rotaru, V.; Andrei, R.I.; Ionescu, S.-O.; Luca, D.; Savu, N.M.; Capsa, C.M.; Alecu, M.; et al. Why Is Surgery Still Done after Concurrent Chemoradiotherapy in Locally Advanced Cervical Cancer in Romania? Cancers 2024, 16, 425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gerard, J.-P.; Romestaing, P.; Chapet, O. Radiotherapy alone in the curative treatment of rectal carcinoma. Lancet Oncol. 2003, 4, 158–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, C.; Cummings, B.J.; Brierley, J.D.; Catton, C.N.; McLean, M.; Catton, P.; Hao, Y. Treatment of locally recurrent rectal carcinoma—Results and prognostic factors. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. 1998, 40, 427–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugiyama, T.; Yakushiji, M.; Noda, K.; Ikeda, M.; Kudoh, R.; Yajima, A.; Tomoda, Y.; Terashima, Y.; Takeuchi, S.; Hiura, M.; et al. Phase II Study of Irinotecan and Cisplatin as First-Line Chemotherapy in Advanced or Recurrent Cervical Cancer. Oncology 2000, 58, 31–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuhrt, M.P.; Chokshi, R.J.; Arrese, D.; Martin, E.W., Jr. Retrospective review of pelvic malignancies undergoing total pelvic exenteration. World J. Surg. Oncol. 2012, 10, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, K.G.; Solomon, M.J.; Koh, C.E. Pelvic exenteration surgery: The evolution of radical surgical techniques for advanced and recurrent pelvic malignancy. Dis. Colon Rectum 2017, 60, 745–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Höckel, M.; Dornhöfer, N. Pelvic exenteration for gynaecological tumours: Achievements and unanswered questions. Lancet Oncol. 2006, 7, 837–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Höckel, M. Ultra-radical compartmentalized surgery in gynaecological oncology. Eur. J. Surg. Oncol. (EJSO) 2006, 32, 859–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burns, E.M.; Quyn, A.; Al Kadhi, O.; Angelopoulos, G.; Armitage, J.; Baker, R.; Barton, D.; Beekharry, R.; Beggs, A.; Blades, R. The ‘Pelvic exenteration lexicon’: Creating a common language for complex pelvic cancer surgery. Color. Dis. 2023, 25, 888–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kroon, H.M.; Dudi-Venkata, N.; Bedrikovetski, S.; Thomas, M.; Kelly, M.; Aalbers, A.; Aziz, N.A.; Abraham-Nordling, M.; Akiyoshi, T.; Alberda, W.; et al. Palliative pelvic exenteration: A systematic review of patient-centered outcomes. Eur. J. Surg. Oncol. (EJSO) 2019, 45, 1787–1795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PelvEx Collaborative. Factors affecting outcomes following pelvic exenteration for locally recurrent rectal cancer. Br. J. Surg. 2018, 105, 650–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- PelvEx Collaborative. Changing outcomes following pelvic exenteration for locally advanced and recurrent rectal cancer. BJS Open 2019, 3, 516–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PelvEx Collaborative. Minimally invasive surgery techniques in pelvic exenteration: A systematic and meta-analysis review. Surg. Endosc. 2018, 32, 4707–4715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, M.E.; Glynn, R.; Aalbers, A.G.J.; Alberda, W.; Antoniou, A.; Austin, K.K.; Beets, G.L.; Beynon, J.; Bosman, S.J.; Brunner, M.; et al. Surgical and Survival Outcomes Following Pelvic Exenteration for Locally Advanced Primary Rectal Cancer: Results from an International Collaboration. Ann. Surg. 2019, 269, 315–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chitoran, E.; Rotaru, V.; Mitroiu, M.-N.; Durdu, C.-E.; Bohiltea, R.-E.; Ionescu, S.-O.; Gelal, A.; Cirimbei, C.; Alecu, M.; Simion, L. Navigating Fertility Preservation Options in Gynecological Cancers: A Comprehensive Review. Cancers 2024, 16, 2214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simion, L.; Ionescu, S.; Chitoran, E.; Rotaru, V.; Cirimbei, C.; Madge, O.-L.; Nicolescu, A.C.; Tanase, B.; Dicu-Andreescu, I.-G.; Dinu, D.M.; et al. Indocyanine Green (ICG) and Colorectal Surgery: A Literature Review on Qualitative and Quantitative Methods of Usage. Medicina 2023, 59, 1530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rausa, E.; Kelly, M.E.; Bonavina, L.; O’Connell, P.R.; Winter, D.C. A systematic review examining quality of life following pelvic exenteration for locally advanced and recurrent rectal cancer. Color. Dis. 2017, 19, 430–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKigney, N.; Houston, F.; Ross, E.; Velikova, G.; Brown, J.; Harji, D.P. Systematic Review of Patient-Reported Outcome Measures in Locally Recurrent Rectal Cancer. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2023, 30, 3969–3986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clavien, P.A.; Barkun, J.; de Oliveira, M.L.; Vauthey, J.N.; Dindo, D.; Schulick, R.D.; de Santibañes, E.; Pekolj, J.; Slankamenac, K.; Bassi, C.; et al. The Clavien-Dindo Classification of Surgical Complications. Ann. Surg. 2009, 250, 187–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, A.L.; Sinha, S.; Peres, L.C.; Hakam, A.; Chon, H.S.; Hoffman, M.S.; Shahzad, M.M.; Wenham, R.M.; Chern, J.-Y. The impact of distance to closest negative margin on survival after pelvic exenteration. Gynecol. Oncol. 2022, 165, 514–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nielsen, M.B.; Rasmussen, P.C.; Lindegaard, J.C.; Laurberg, S. A 10-year experience of total pelvic exenteration for primary advanced and locally recurrent rectal cancer based on a prospective database. Color. Dis. 2012, 14, 1076–1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhangu, A.; Ali, S.M.; Brown, G.; Nicholls, R.J.; Tekkis, P. Indications and Outcome of Pelvic Exenteration for Locally Advanced Primary and Recurrent Rectal Cancer. Ann. Surg. 2014, 259, 315–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radwan, R.W.; Jones, H.G.; Rawat, N.; Davies, M.; Evans, M.D.; Harris, D.A.; Beynon, J.; McGregor, A.D.; Morgan, A.R.; Freites, O.; et al. Determinants of survival following pelvic exenteration for primary rectal cancer. Br. J. Surg. 2015, 102, 1278–1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, J.D.; Nash, G.M.; Weiser, M.R.; Temple, L.K.; Guillem, J.G.; Paty, P.B. Multivisceral resections for rectal cancer. Br. J. Surg. 2012, 99, 1137–1143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harris, D.A.; Davies, M.; Lucas, M.G.; Drew, P.; Carr, N.D.; Beynon, J. Multivisceral resection for primary locally advanced rectal carcinoma. Br. J. Surg. 2011, 98, 582–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Solomon, M.J.; Brown, K.G.M.; Koh, C.E.; Lee, P.; Austin, K.K.S.; Masya, L. Lateral pelvic compartment excision during pelvic exenteration. Br. J. Surg. 2015, 102, 1710–1717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, K.G.M.; Solomon, M.J.; Lau, Y.C.; Steffens, D.; Austin, K.K.S.; Lee, P.J. Sciatic and Femoral Nerve Resection during Extended Radical Surgery for Advanced Pelvic Tumours: Long-Term Survival, Functional, and Quality-of-life Outcomes. Ann. Surg. 2021, 273, 982–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, K.G.M.; Koh, C.E.; Solomon, M.J.; Qasabian, R.; Robinson, D.; Dubenec, S. Outcomes after en Bloc Iliac Vessel Excision and Reconstruction during Pelvic Exenteration. Dis. Colon Rectum 2015, 58, 850–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cirimbei, C.; Rotaru, V.; Chitoran, E.; Cirimbei, S. Laparoscopic Approach in Abdominal Oncologic Pathology. In Proceedings of the 35th Balkan Medical Week, Athens, Greece, 25–27 September 2018; pp. 260–265. Available online: https://www.webofscience.com/wos/woscc/full-record/WOS:000471903700043 (accessed on 20 July 2023).

- Gannon, C.J.; Zager, J.S.; Chang, G.J.; Feig, B.W.; Wood, C.G.; Skibber, J.M.; Rodriguez-Bigas, M.A. Pelvic Exenteration Affords Safe and Durable Treatment for Locally Advanced Rectal Carcinoma. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2007, 14, 1870–1877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vermaas, M.; Ferenschild, F.; Verhoef, C.; Nuyttens, J.; Marinelli, A.; Wiggers, T.; Kirkels, W.; Eggermont, A.; de Wilt, J. Total pelvic exenteration for primary locally advanced and locally recurrent rectal cancer. Eur. J. Surg. Oncol. (EJSO) 2007, 33, 452–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rottoli, M.; Vallicelli, C.; Boschi, L.; Poggioli, G. Outcomes of pelvic exenteration for recurrent and primary locally advanced rectal cancer. Int. J. Surg. 2017, 48, 69–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferenschild, F.T.J.; Vermaas, M.; Verhoef, C.; Ansink, A.C.; Kirkels, W.J.; Eggermont, A.M.M.; de Wilt, J.H.W. Total Pelvic Exenteration for Primary and Recurrent Malignancies. World J. Surg. 2009, 33, 1502–1508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zoucas, E.; Frederiksen, S.; Lydrup, M.; Månsson, W.; Gustafson, P.; Alberius, P. Pelvic exenteration for advanced and recurrent malignancy. World J. Surg. 2010, 34, 2177–2184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Candelaria, M.; Cetina, L.; Garcia-Arias, A.; Lopez-Graniel, C.; de la Garza, J.; Robles, E.; Duenas-Gonzalez, A. Radiation-sparing managements for cervical cancer: A developing countries perspective. World J. Surg. Oncol. 2006, 4, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Voinea, S.; Herghelegiu, C.G.; Sandru, A.; Ioan, R.G.; Bohilțea, R.E.; Bacalbașa, N.; Chivu, L.I.; Furtunescu, F.; Stanica, D.C.; Neacșu, A. Impact of histological subtype on the response to chemoradiation in locally advanced cervical cancer and the possible role of surgery. Exp. Ther. Med. 2021, 21, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pawlik, T.M.; Skibber, J.M.; Rodriguez-Bigas, M.A. Pelvic Exenteration for Advanced Pelvic Malignancies. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2006, 13, 612–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Age | <40 years | 11 (8.33%) |

| 57.4 years (range 24–78) | 40–49 years | 24 (18.18%) |

| 50–59 years | 29 (21.97%) | |

| 60–69 years | 35 (26.52%) | |

| ≥70 years | 33 (25.00%) | |

| Gender | Female | 87 (65.91%) |

| Male | 45 (34.09%) | |

| Provenience | Urban | 34 (25.76%) |

| Rural | 98 (74.24%) | |

| Comorbidities | Hypertension | 48 (36.36%) |

| Diabetes | 19 (14.39%) | |

| Chronic renal disease | 12 (9.09%) | |

| Chronic pulmonary disease | 9 (6.82%) |

| Indication for exenteration | Primary neoplasm | 86 (65.15%) |

| Recurrent cancer | 37 (28.03%) | |

| Synchronous primary cancers | 4 (3.03%) | |

| Benign indications * | 5 (3.79%) | |

| Origin of tumor | Cervical | 45 (35.43%) |

| Endometrial | 12 (9.45%) | |

| Ovarian | 9 (7.09%) | |

| Urinary bladder | 21 (16.53%) | |

| Colorectal (including anal) | 36 (28.35%) | |

| Other ** | 4 (3.15%) | |

| Histological type | Squamous cell carcinoma | 48 (36.36%) |

| Adenocarcinoma | 59 (44.70%) | |

| Sarcoma | 4 (3.03%) | |

| Urothelial carcinoma | 21 (15.91%) | |

| Differentiation degree | G1—well differentiated | 14 (10.61%) |

| G2—moderately differentiated | 56 (42.42%) | |

| G3—poorly differentiated | 62 (46.97%) | |

| Neoadjuvant therapy | Yes | 74 (56.06%) |

| No | 58 (43.94%) |

| Type of Pelvic Exenteration | |

| Total exenterations | 38 (28.79%) |

| Total without pelvic floor resection | 31 (23.49%) |

| Total infralevator | 7 (5.30%) |

| Partial exenterations | 94 (71.21%) |

| Anterior | 69 (52.27%) |

| Posterior | 25 (18.94%) |

| Curative Intent | |

| Radical | 97 (76.38%) |

| Palliative | 30 (23.62%) |

| Lymph node dissection | |

| Pelvic lymph node | 85 (66.93%) |

| Paraaortic lymph node | 21 (16.54%) |

| Inguinal lymph node | 2 (1.57%) |

| Resection of extra pelvic organs | |

| Yes | 22 (16.67%) |

| No | 110 (83.33%) |

| Digestive tract reconstructive procedures | 63 |

| Colorectal anastomosis | 19 (30.16%) |

| Terminal colostomy | 44 (69.84%) |

| Urinary reconstructive procedures | 107 |

| Cutaneous urostomy | 42 (39.25%) |

| Bricker procedure | 44 (41.12%) |

| Ileal neobladder | 21 (19.63%) |

| Median length of surgery (min) | 410 min (range 280–600 min) |

| Median blood loss (mL) | 850 mL (range 350–1400 mL) |

| Median intensive care unit stay (days) | 7 days (range 3–32 days) |

| Median stay in hospital (days) | 17 days (range 10–54 days) |

| Early morbidity and mortality | |

| Clavien–Dindo Grades 1–2 | 25 (18.94%) |

| Clavien–Dindo Grades 3–4 | 29 (21.69%) |

| Reinterventions | 17 (12.88%) |

| Causes of early reinterventions | occlusion, digestive/urinary fistulas, hemorrhagic shock, peritonitis/intraabdominal abscess, and acute ischemia of inferior limb |

| Mortality (Clavien-Dindo Grade 5) | 3 (2.72%) |

| Causes of early mortality | multiple system organ failure, acute cardiac complications |

| Tumor size | <5 cm | 38 (29.92%) |

| ≥5 cm | 89 (70.08%) | |

| Radicality | R0 | 97 (76.38%) |

| R1 | 27 (21.26%) | |

| R2 | 3 (2.36%) | |

| Lateral extension of tumor | Yes | 23 (18.11%) |

| No | 104 (81.89%) | |

| Positive regional lymph nodes | Yes | 95 (74.80%) |

| No | 32 (25.20%) | |

| Perineural invasion | Yes | 69 (54.33%) |

| No | 36 (28.35%) | |

| Not specified | 22 (17.32%) | |

| Lympho-vascular invasion | Yes | 78 (61.42%) |

| No | 42 (33.07%) | |

| Not specified | 7 (5.51%) |

| By Type of Exenteration | ||

| Total vs. partial 38 vs. 94 cases | Early-morbidity rate | 39.47% vs. 41.49% (p = 0.048) |

| Early-mortality rate | 2.63% vs. 2.13% (p = 0.238) | |

| RFS | 23.9 months vs. 23.0 months (p = 0.146) | |

| OS | 40.3 months vs. 42.7 months (p = 0.047) | |

| Radical vs. palliative (R0 vs. R1/R2 resections) 97 vs. 30 cases | Early-morbidity rate | 41.24% vs. 46.67% (p = 0.041) |

| Early-mortality rate | 2.06% vs. 3.33% (p = 0.034) | |

| RFS | 31.8 months vs. 0 months (p < 0.001) | |

| OS | 52.6 months vs. 14.8 months (p-value < 0.001) | |

| By Type of Tumor | ||

| Primary vs. recurrent | Early-morbidity rate | 35.56% vs. 62.86% (p < 0.001) |

| 90 vs. 37 cases | Early-mortality rate | 1.11% vs. 5.40% (p < 0.001) |

| RFS | 26.6 months vs. 18.7 months (p = 0.03) | |

| OS | 49.1 months vs. 32.8 months (p-value = 0.040) | |

| Colorectal vs. non-colorectal | Early-morbidity rate | 36.11% vs. 45.05% (p < 0.001) |

| 36 vs. 91 cases | Early-mortality rate | 2.78% vs. 2.19% (p = 0.187) |

| RFS | 28.2 months vs. 22.7 months (p = 0.024) | |

| OS | 48.6 months vs. 38.3 months (in gynecological cancers—p < 0.001) or 35.2 months (in urinary cancers—p < 0.001) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rotaru, V.; Chitoran, E.; Zob, D.-L.; Ionescu, S.-O.; Aisa, G.; Andra-Delia, P.; Serban, D.; Stefan, D.-C.; Simion, L. Pelvic Exenteration in Advanced, Recurrent or Synchronous Cancers—Last Resort or Therapeutic Option? Diagnostics 2024, 14, 1707. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics14161707

Rotaru V, Chitoran E, Zob D-L, Ionescu S-O, Aisa G, Andra-Delia P, Serban D, Stefan D-C, Simion L. Pelvic Exenteration in Advanced, Recurrent or Synchronous Cancers—Last Resort or Therapeutic Option? Diagnostics. 2024; 14(16):1707. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics14161707

Chicago/Turabian StyleRotaru, Vlad, Elena Chitoran, Daniela-Luminita Zob, Sinziana-Octavia Ionescu, Gelal Aisa, Prie Andra-Delia, Dragos Serban, Daniela-Cristina Stefan, and Laurentiu Simion. 2024. "Pelvic Exenteration in Advanced, Recurrent or Synchronous Cancers—Last Resort or Therapeutic Option?" Diagnostics 14, no. 16: 1707. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics14161707