Abstract

Background: Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) is a key therapeutic procedure in diseases of the pancreas or bile ducts. The understanding and effective management of the risks associated with the procedure, especially in the context of possible infectious complications, is crucial for patients’ safety. The aim of this review was to analyze the results of studies on antibiotic prophylaxis for infectious complications of ERCP, pancreatoscopy, and cholangioscopy. Methods: This study is a review of the articles available in PubMed, Medline, and Embase published in the last 30 years. Results: Nineteen studies and six sets of guidelines on antibiotic prophylaxis before ERCP were retrieved. Conclusions: Based on the available studies and recommendations, it can be concluded that antibiotic prophylaxis before ERCP is beneficial for immunocompromised patients or those at risk of bacterial endocarditis. In other groups of patients, antibiotic prophylaxis reduces the risk post-ERCP bacteremia but does not significantly reduce the risk of cholangitis and infectious complications. The effectiveness of antibiotic prophylaxis in patients at risk of incomplete biliary drainage needs to be verified in further studies.

1. Introduction

Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) is an advanced endoscopic procedure the aim of which is to treat diseases of the bile ducts or pancreatic ducts. The incidence of complications after ERCP ranges from 1% to around 19–20% [1,2,3]. The most common are cholangitis and acute pancreatitis, which occur in 3% and 5.5% of patients, respectively [3]. Other, rare complications are bleeding-, perforation-, and sedation-related. Infections after ERCP are a consequence of the bacterial contamination of physiologically sterile bile and the subsequent translocation of bacteria into the main bloodstream. In healthy humans, there are mechanisms that protect bile from bacterial contamination. These include sphincter of Oddi tension, which is a gate keeper that prevents the entry of bacteria into the intestinal lumen, and tight junctions between hepatocytes, which prevent the entry of bacteria from bile into the bloodstream [1]. Additional mechanisms include the secretion of immunoglobulin IgA, which regulates the immune response and the antiseptic properties of bile salts, into bile. An equally important mechanism in preventing bile contamination is the normal flow of bile in the bile ducts [1,4]. There are two main routes by which bacteria translocate into the bile: blood-borne [1,3,5] and retrograde from the intestinal lumen [1,6]. In the first scenario, bacteria from the gastrointestinal tract migrate through the intestinal wall into the mesenteric veins and further portal vein to the liver and are then transported into the sinuses of the liver and the Disse space and directly into the bile [1,7]. In the case of the retrograde route, bacteria migrate via the papilla of Vater from the duodenum into the common bile duct, directly into the biliary tree, and cause bacteriobilia [1,8]. The ascending route is more prevalent for the bacterial colonization of the bile and biliary tree than the blood-borne route (Table 1). Bacteriobilia can lead to clinically significant bacteremia and therefore septic complications. Transient bacteremia itself does not trigger infection and septic complications in every case. Everyday activities such as tooth brushing (20% to 60%) or flossing (20–40%) are also associated with the occurrence of transient bacteremia [9,10,11]. The risk of clinically significant bacteremia is related to the type of biliary pathology and comorbidities [1]. In patients with malignant lesions, bacteremia is observed in 35% of cases; in patients with bile duct stones, in 70–80% of cases; and in 90% of patients with Vater’s papilla dysfunction. In ERCP patients who do not have biliary obstruction, the risk of bacteremia is approximately 6%, whereas for patients with risk factors, the estimated risk of bacteremia is 18% [10].

Table 1.

Prevalence of individual bacterial strains in bile according to available studies.

Mortality in severe post-ERCP cholangitis ranges from 10 to 16% [1]. In a study by Bilbao Mk. et al. covering 10,000 patients, mortality due to severe cholangitis was approximately 10% [16], while mortality in the pediatric population is relatively low [17].

The spectrum of bacteria that most commonly cause post-ERCP infectious complications mostly overlaps with the bacteria that cause transient bacteremia. These are Gram-negative bacteria of the groups E. coli, Klebsiella spp., and Pseudomonas spp., Gram-positive Enterococci species, anaerobic Bacteroides spp., and Clostridium spp. (Table 1) [5,9]. The aim of this review was to determine the actual indications for antibiotic prophylaxis prior to ERCP and to verify whether antibiotics prophylaxis has a real impact on the risk of complications after ERCP.

2. Methods

The PubMed (National Library of Medicine, Bethesda, MD, USA), Medline, and Embase databases were searched using the following keywords: ERCP, cholangioscopy, pancreatoscopy, sepsis, cholangitis, infection, antibiotic(s), prophylaxis, adult, pediatric. For the purposes of this review, randomized controlled trials [RCTs], retrospective studies, guidelines, and scientific society recommendations from 1994 to October 2024 were selected.

3. Results

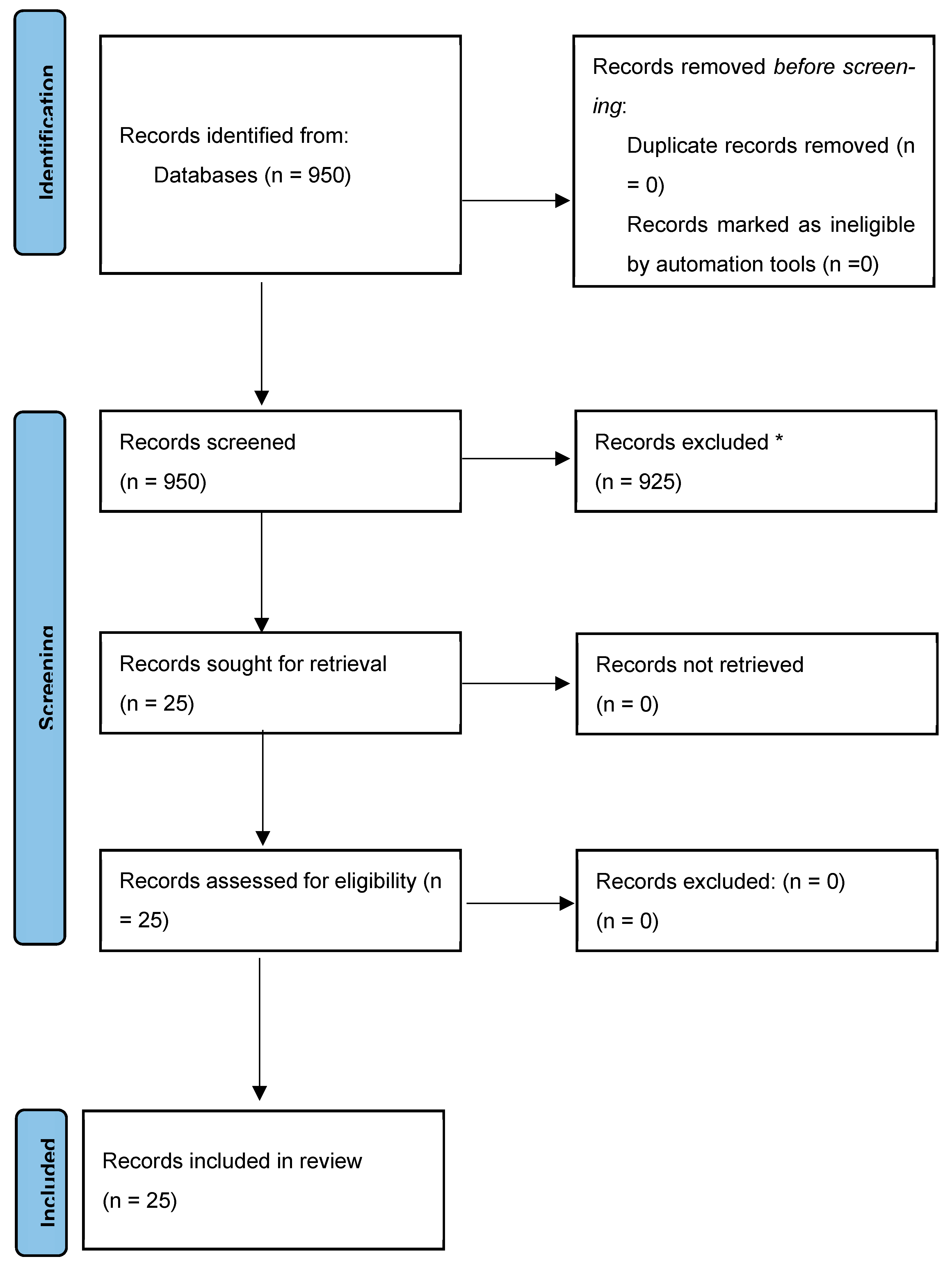

An initial search identified 950 studies, 25 of which met the criteria for this narrative review. The PRISMA plot is presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Infection prevention in endoscopic biliary and pancreatic procedures (PRISMA). * Reasons for excluding records or full-text articles were as follows: articles not dealing with antibiotic prophylaxis in ERCP, reviews, articles in a language other than English, single case reports.

Based on the search strategy, 25 publications were identified, including 16 RCTs, 3 retrospective studies, and 6 sets of guidelines/recommendations.

3.1. RCTs and Retrospective Studies

Among the twenty-five publications, two studies— a randomized study by Norouzi et al. [18] and a retrospective study by Gustaffson [19]—covered homogenous groups of patients, while the other concerned heterogenous groups of indications for ERCP (Table 2). Norouzi et al. [18] examined the effect of gentamicin added to the contrast medium on the rate of post-ERCP cholangitis in patients with non-calculous obstructive jaundice. There was no significant difference in the incidence of cholangitis between the group receiving gentamicin versus the group without antibiotics. Niederau et al. evaluated the effectiveness of 2 g cefotaxime versus no antibiotic [20]. They found that bacteremia and cholangitis occurred in eight patients and only in the group without prophylaxis (in four cases, ERCP had failed to decompress the biliary system completely). Ratanachu et al. tried to determine the influence of ciprofloxacin on cholangitis rates in cholestatic patients with adequate biliary drainage [21]. Of 48 patients who received 200 mg ciprofloxacin iv before ERCP, 24 continued it for the next 48 h after the procedure. The continual use of ciprofloxacin in patients with cholestasis after adequate biliary drainage procedures had no effect on cholangitis reduction. Finkelstein et al. evaluated the effectiveness of 1 g cefonicid versus no antibiotic and found that the rates of bacteriemia and cholangitis were similar in both groups [22]. Lorenz et al. prospectively assessed the effectiveness of a single prophylactic dose of 1500 mg iv cefuroxime [23]. The septicemia rate was 6.1% in the antibiotic group versus 10% in the group without an antibiotic. Similarly, Raty et al. evaluated the effectiveness of a single dose of 2 g of ceftazidime iv. before ERCP and found that a single dose of the antibiotic reduced the risk of cholangitis after the procedure (0 patients with cholangitis in antibiotic group versus 7 in the control group) [24]. Similar conclusions were reached in a study by Leem et al., who compared the administration of 1 g intravenous cefoxitin versus placebo [25]. Bacteremia was found in four patients in the antibiotic group versus eleven in the placebo group, and cholangitis in three patients in the antibiotic group versus eleven in the placebo. They concluded that antibiotic prophylaxis before ERCP in patients with biliary obstruction resulted in a significantly lower risk of infectious complications, especially cholangitis. In contrast, Spicak et al. did not confirm that the use of antibiotic prophylaxis before therapeutic ERCP reduced the risk of cholangitis or affected bacteremia [26]. Llach et al., who examined 600 mg of clindamycin and 80 mg of gentamycin, both given intramuscularly before ERCP, obtained similar results [27]. These authors stated that the prophylactic administration of clindamycin plus gentamycin reduced the incidence of neither bacteremia nor cholangitis. Smith et al. evaluated the efficacy of a 3 day course of oral amoxicillin with clavulanic acid after a single dose of ticarcillin with clavulanic acid in the prevention of ERCP-related sepsis [28]. Sepsis occurred in 10% of patients with a single dose of the antibiotic before ERCP and in 3% of individuals in the group that received the antibiotic for the additional 3 days. The study’s conclusion was that the performance of sphincterotomy and the presence of stones in the common bile duct were significant risk factors for infectious complications, and the administration of an additional dose of antibiotic may be justified in these cases. In a study by Hazel et al., patients with bile duct stones or biliary stenosis received piperacillin as prophylaxis [29]. There was no reduction in infections despite antibiotic administration. In a randomized, double-blind study, Baudouin et al. showed that piperacillin with tazobactam at a dose of 4 g 30 min before ERCP [30] reduced the infectious complication rate in patients with suspected biliary obstruction.

Three studies compared the effectiveness of two different antibiotics for prophylaxis. Mehal I et al. compared the efficacy of oral ciprofloxacin and intravenous cefuroxime [31]. The administration of ciprofloxacin was found to be as effective in the prevention of infectious complications after ERCP and was cheaper than cefuroxime. Davis et al. compared the efficacy of periprocedural oral 750 mg ciprofloxacin with 1 g iv. cefazolin in the prevention of septic complications in a group of patients with gallstones and in individuals with benign or malignant strictures [32]. There were no significant differences in the efficacy of the two antibiotics. Kim et al. compared the effectiveness of 400 mg intravenous moxifloxacin to 2 g ceftriaxone administered 90 min before ERCP [33]. The frequency of cholangitis and septicemia was comparable in both groups.

Thompson et al. retrospectively analyzed the effect of biliary pathology and antibiotic prophylaxis on the risk of cholangitis after ERCP [34]. In a group of ninety patients who had not received prophylaxis, cholangitis only occurred in three patients.

In a retrospective study, Gustaffson et al. analyzed a homogeneous group of 2144 patients with primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC) treated with ERCP. A total of 1407 patients received antibiotic prophylaxis and 737 patients did not. The infection rate was 3.3% in the antibiotic group in comparison to 4.5% in the control group [19]. Pohl et al. examined the efficacy of ciprofloxacin in patients with PSC and biliary stenosis treated with ERCP [35]. Bacteria were found in the bile of ten out of twelve patients; therefore, it was concluded that short-term antibiotic treatment was not effective in bacteria eradication from the biliary tract.

Olsson et al. performed a registry study based on the Swedish Registry of Gallstone Surgery and ERCP (covering more than 22,000 ERCP procedures). The use of antibiotic prophylaxis reduced the number of septic complications by 15%. It also reduced the risk of overall post-ERCP adverse events by 24%, especially in patients with mechanical jaundice and stones in the bile ducts [36].

In the aforementioned study by Gustaffson et al., 3.4% of patients on antibiotic prophylaxis had an infection after cholangioscopy, versus 3.7% in the group without an antibiotic [19]. In a retrospective study, Turowski et al. evaluated 206 patients examined with cholangioscopy [37]. In their study, cholangitis occurred in 1% of patients who received antibiotics versus 12.8% in the group without antibiotics.

No studies on antibiotic prophylaxis in pancreatoscopy were found. Similarly, no studies on antibiotic prophylaxis before ERCP, cholangioscopy, or pancreatoscopy in children were retrieved.

Table 2.

Studies on antibiotic prophylaxis before pancreatobiliary endoscopy.

Table 2.

Studies on antibiotic prophylaxis before pancreatobiliary endoscopy.

| Author | Type of Study | Indications | Intervention | Bacteremia (n/N) * | Cholangitis (n/N) | Authors’ Conclusion |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Niederau et al., 1994 [20] | RCT | diagnostic or therapeutic ERCP | cefotaxime 2 g iv. 15 min before ERCP | antibiotic: 0/50 control: 4/50 | antibiotic: 0/50 control: 4/50 | Cefotaxime can reduce the incidence of bacteremia and sepsis. |

| Byl et al., 1995 [30] | RCT | diagnostic or therapeutic ERCP | piperacillin 4 g iv. | antibiotic: 2/34 control: 7/34 | antibiotic: 2/34 control:5/34 | Antimicrobial prophylaxis significantly reduces the incidence of septic complications after therapeutic ERCP among patients presenting with cholestasis. |

| Mehal et al., 1995 [31] | RCT | radiological evidence of biliary obstruction | 1.ciprofloxacin 750 mg po. 2.cefuroxime 1.5 g iv. | antibiotic 1:1/100 antibiotic 2:1/100 | antibiotic 1:1/100 antibiotic 2:1/100 | A pre- and post-ERCP oral ciprofloxacin regime is safe and provides effective prophylaxis against ERCP-induced cholangitis and septicemia in high-risk patients. It is also more economical than a regime of intravenous cefuroxime and does not require nursing staff with training in intravenous techniques. |

| Davis et al., 1998 [32] | RCT | radiological evidence of biliary obstruction | 1.ciprofloxacin po 750 mg 2.cephazolin 1 g iv. | antibiotic: 10/77 antibiotic 2: 2/72 | antibiotic 1: 0/77 antibiotic 2: 3/72 | Oral ciprofloxacin is a cost-effective prophylactic agent for high-risk ERCP. |

| Ratanachu et al., 2007 [21] | RCT | therapeutic ERCP | ciprofloxacin 200 mg iv. | not covered | antibiotic: 1/22 control: 2/26 | Continual use of ciprofloxacin in patients with cholestasis after adequate biliary drainage procedures plays no role in reducing cholangitis. |

| Finkelstein et al., 1996 [22] | RCT | diagnostic or therapeutic ERCP | cefonicid 1 g iv. | antibiotic: 3/88 control: 2/91 | antibiotic: 7/88 control: 2/91 | Infectious complications could not be prevented by cefonicid prophylaxis. |

| Lorenz at al., 1996 [23] | RCT | therapeutic eRCP | cefuroxime 1.5 g iv. | antibiotic: 3/49 control: 8/50 | not covered | The differences obtained between the two groups were not statistically different. |

| Van del Hazel et al., 1996 [29] | RCT | diagnostic or therapeutic ERCP | piperacillin 4 g iv. | not covered | antibiotic: 12/270 control: 17/281 | Single-dose prophylaxis with piperacillin is not associated with a clinically significant reduction in the incidence of acute cholangitis after ERCP. |

| Raty et al., 2001 [24] | RCT | diagnostic or therapeutic ERCP | ceftazidime 2 g iv. | not covered | antibiotic: 0/155 control 7/160 | Antibiotic prophylaxis effectively decreases the risk of cholangitis after ERCP. |

| Leem et al., 2024 [25] | RCT | biliary obstruction | cefoxitin 1 g iv. | antibiotic: 4/176 control: 11/176 | antibiotic: 3/76 control: 11/173 | Antibiotic prophylaxis before ERCP in patients with biliary obstruction resulted in a significantly lower risk of infectious complications, especially cholangitis, than placebo. |

| Spicak et al., 2002 [26] | RCT | biliary obstruction | amoxicillin with clavulanic acid 2.4 g iv. | antibiotic: 18/77 control: 24/88 | antibiotic: 4/77 control: 3/88 | Antibiotic therapy before therapeutic ERCP does not reduce the risk of complicating cholangitis and does not influence bacteremia. |

| Llach et al., 2006 [27] | RCT | diagnostic or therapeutic ERCP | clindamycin 600 mg and gentamicin 80 mg im. | antibiotic: 2/31 control: 2/30 | antibiotic: 1/31 control 1/30 | Clindamycin plus gentamicin does not reduce the incidence of bacteremia and cholangitis. |

| Sciume et al., 2004 [38] | RCT | ERCP with state implantation due to biliary obstruction | levofloxacin 500 mg | not covered | not covered | In patients in group 1, “stent patency in situ” was 50% longer than in group 2, with a lower incidence of cholangitis and hospital admittance. |

| Norouzi et al., 2013 [18] | RCT | non-calculous obstructive jaundice | gentamicin added to contrast during ERCP | not covered | antibiotic: 5/57 control: 5/57 | Adding gentamicin to contrast media had no significant effect on the incidence of post-ERCP cholangitis. |

| Kim et al., 2017 [33] | RCT | biliary obstruction | moxifloxacin 400 mg iv or ceftriaxone 2 g iv | antibiotic 1:1/43 antibiotic 2: 2/43 | antibiotic 1: 1/43 antibiotic 2: 1/43 | Intravenous moxifloxacin is not inferior to intravenous ceftriaxone for the prophylactic treatment of post-ERCP cholangitis and cholangitis-associated morbidity. |

| Smith et al., 1996 [28] | RCT | diagnostic or therapeutic ERCP | ticarcillin 1.6 g iv with clavulanic acid 1 h before ERCP or ticarcillin with clavulanic acid before ERCP and 3 days’ oral amoxycillin and clavulanic acid 1 g thereafter | not covered | not covered | Three days of oral amoxicillin and clavulanic acid after a single dose of intravenous antibiotics is recommended in patients at an increased risk of complications. |

| Gustafsson et al., 2023 [19] | Retrospective | primary sclerosing cholangitis | various antibiotics | not covered | not covered | Patients with PSC who undergo ERCP have the same frequency of adverse events regardless of whether antibiotics were used. |

| Thompson et al., 2002 [34] | Retrospective | diagnostic or therapeutic ERCP | various antibiotics | not covered | not covered | Single-dose antibiotic prophylaxis in the setting of presumed biliary obstruction to prevent ERCP-related cholangitis is a cost-saving strategy. |

| Olsson et al., 2015 [36] | Retrospective | diagnostic or therapeutic ERCP | various antibiotics | not covered | not covered | The use of prophylactic antibiotic therapy before ERCP for the three main indications of gallstones, tumors, and mechanical jaundice reduces the risk of septic complications by 15%. |

* n—numbers of patients with specified event; N—number of patients in the study group.

3.2. Guidelines and Recommendations

Six publications covering recommendations and guidelines were retrieved (Table 3). All societies recommend antibiotic prophylaxis before ERCP in patients at risk of incomplete biliary drainage. In the recommendations of five societies, antibiotic prophylaxis is advised for patients with PSC, malignancy, neutropenia (defined as <500 neutrophils/µL), and in patients after liver transplantation. According to four societies, advanced hematologic tumors are also an indication for antibiotic prophylaxis. Only three societies recommend prophylaxis in patients with pancreatic pseudocysts and in patients with synthetic vascular grafts (within 6 months after implantation).

Table 3.

Indications for antibiotic prophylaxis before biliary and pancreatic endoscopy according to guidelines and recommendations.

All societies do not recommend the use of antibiotic prophylaxis in patients without risk factors in whom the achievement of complete biliary drainage is expected.

The ESPHGAN guidelines [43] and ESGE [43] guidelines do not cover antibiotic prophylaxis before ERCP in the pediatric population.

4. Discussion

In the latest guidelines of the American and British Gastroenterological Societies, endoscopic procedures at high risk for bacteremia, which include ERCP in selected conditions, are indications for antibiotic prophylaxis. The use of antibiotic prophylaxis prior to ERCP is largely dependent on the individual patient’s clinical situation, concomitant burdens, and in-house experience. Antibiotic prophylaxis is recommended for patients qualified for ERCP and belonging to high-risk groups. High-risk groups include patients with risk of incomplete biliary drainage, cirrhosis with ascites/gastrointestinal bleeding, liver transplant recipients, and patients with neutropenia or with vascular grafts within 6 months of implantation, as well as patients at risk of bacterial endocarditis [5,10]. For patients who do not belong to the aforementioned risk groups, the use of antibiotics is debatable and is claimed to not be associated with a reduction in infection risk.

In 1988, Siegman-Igra et al. published a retrospective study on 720 ERCPs and proved that the use of antibiotics was associated with a reduction in infectious complications from 4.3% to 0%; however, in about 60% of the analyzed cases, the reason for ERCP was not specified, and neither were data on the type of antibiotic prophylaxis used [30].

A review by Brand et al. reached the conclusion that prophylactic antibiotics reduce bacteriaemia and seem to prevent cholangitis and septicemia in patients treated with elective ERCP [44].

In a meta-analysis by Merchan et al., who compared the results from 10 randomized trials on antibiotic prophylaxis in ERCP involving a group of 1757 patients, prophylactic antibiotic use reduced the risk of bacteremia but did not reduce the risk of infectious complications [3]. The authors confirmed that the risk of complications such as cholangitis or sepsis after ERCP is mainly related to incomplete biliary drainage and that full drainage should be sought first.

Similar results were found by Allison et al., who prepared the guidelines on behalf of the endoscopy committee of the BSG [9]. Olsson et al. studied a national population-based study cohort (registered in the Swedish Registry of Gallstone Surgery and ERCP) and analyzed 22,000 ERCPs with the three most common indications for the procedure: cholelithiasis, mechanical jaundice, and tumor [36]. They found that the use of antibiotic prophylaxis in patients with gallstones reduces the risk of adverse events after the procedure by 23%. However, the scope of their cohort study did not cover the patients’ comorbidities; therefore, Olsson et al.’s results cannot be translated into universal guidelines [9].

In a review article by Subhani et al., who summarized the results of available randomized clinical trials on the efficacy of individual antibiotics in the prevention of infectious complications after ERCP, the conclusion was made that antibiotic prophylaxis before ERCP is recommended for patients at high risk of infective endocarditis, while for patients with incomplete biliary drainage, antibiotics should be started immediately after ERCP and continued until complete drainage is achieved [1].

Based on the available research results, it may be concluded that antibiotic prophylaxis should be used in patients at risk of incomplete biliary drainage. However, there is no clear definition of which precisely defined conditions the risk of incomplete drainage refers to. It may be assumed that patients with PSC, hilar tumors, retained bile stones, multiple liver metastases, or those with a history of recurrent cholangitis could form a group at high risk of incomplete biliary drainage. The completeness of biliary drainage can only be reliably assessed after ERCP; therefore, some patients who should receive prophylaxis before ERCP receive it just after the procedure. This mode of antibiotic administration cannot be equated with prophylaxis. According to the World Health Organization’s (WHO) Surgical Safety Checklist, antimicrobial prophylaxis should be given 60 min or less before the skin incision (which in the case of ERCP corresponds to duodenal papilla instrumentation) to achieve adequate antibiotic tissue concentration.

Only individual studies have evaluated indications for antibiotic prophylaxis in homogeneous groups of patients qualified for ERCP; moreover, the endpoints of the published results vary. Based on the retrieved publications, it was not possible to prove a clear advantage of antibiotic administration in the prevention of infectious complications after ERCP or ERCP with subsequent cholangioscopy or pancreatoscopy.

We did not find studies on antibiotic prophylaxis in pediatric patients. In a meta-analysis by Danielle et al., with a clinical database of more than 2600 patients, the authors found that the most common post-ERCP complications in the pediatric population are acute pancreatitis (4.7%), bleeding (0.6–1%), and infection (0.8%) [45]. Similar conclusions were reached in a study by Gomez et al. that analyzed case series of 30 children who underwent 65 ERCP procedures. The results showed that septic complications in the pediatric population are relatively rare (1.5%). In addition, the mortality rate was 0% in all studies reviewed. These results suggest that infectious complications after ERCP in the pediatric population are very rare [17].

Data on antibiotic prophylaxis before pancreatoscopy are too weak to draw reliable conclusions. Further studies on antibiotic prophylaxis efficacy in the population of patients at risk of incomplete biliary drainage are needed. Before the completion of such well-designed randomized clinical studies, it is not possible to make reliable grade A recommendations.

5. Conclusions

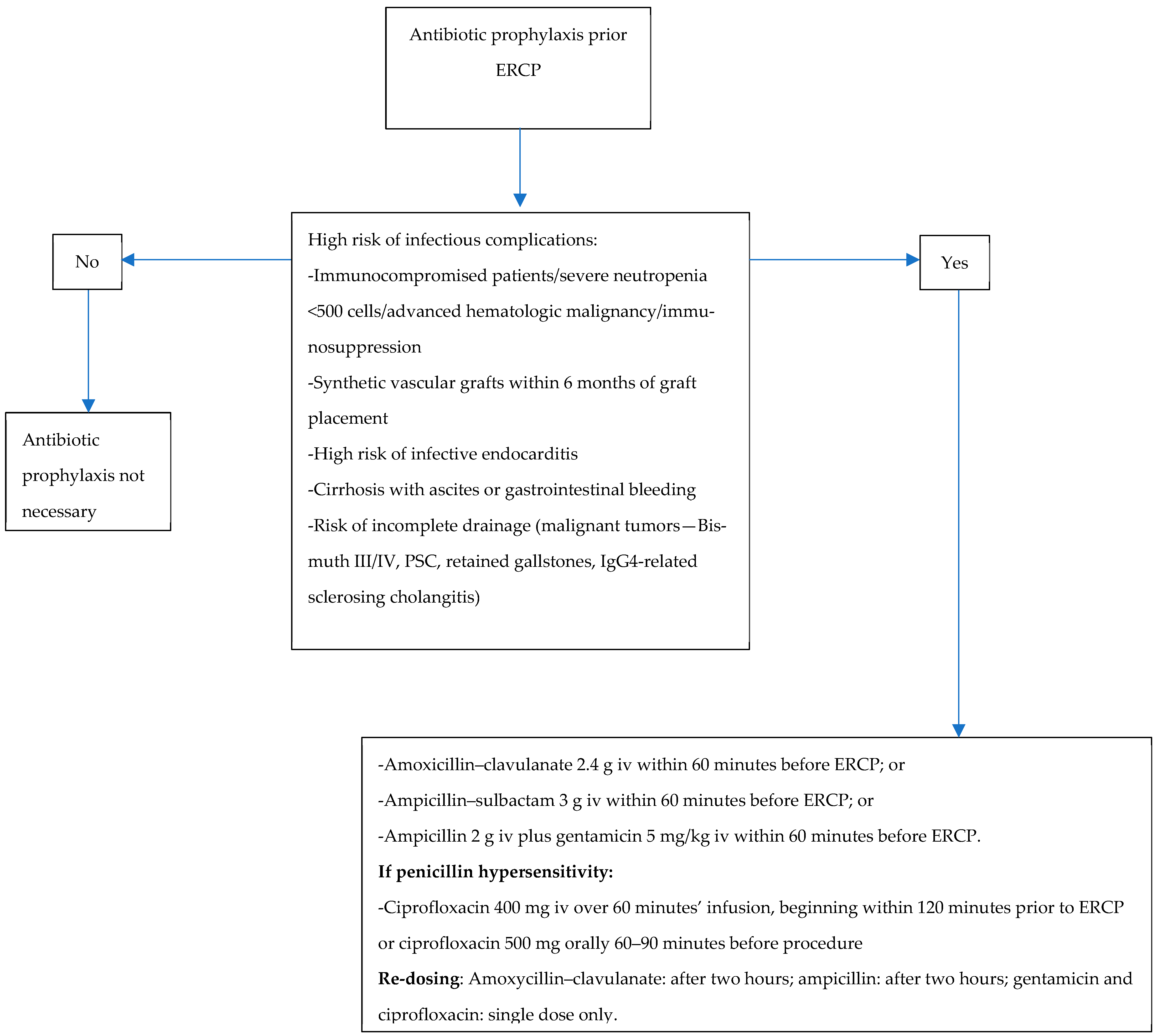

Based on expert opinions and the available clinical experience, antibiotic prophylaxis before ERCP, cholangioscopy, or pancreatoscopy is recommended for patients with risk factors for bacterial endocarditis, cirrhotic patients with ascites/gastrointestinal bleeding, liver transplant recipients, and patients with neutropenia or with vascular grafts within 6 months of implantation. In patients not belonging to these risk groups, the administration of antibiotics before ERCP reduces the risk of bacteremia but does not affect the risk of cholangitis. In individuals with risk factors for incomplete drainage, such as retained gallstones, PSC, primary or secondary tumors of the liver, and IgG4-related sclerosing cholangitis, antibiotic prophylaxis seems to be a reasonable approach. Alternatively, initial treatment (which is not prophylaxis) of biliary infection can be started during ERCP if complete biliary drainage has not been achieved. The proposed strategies need to be verified in clinical studies.

The choice of antibiotic for prophylaxis should follow the local epidemiology of microbial resistance and should cover the spectrum of the most common Gram-negative bacteria from the Enterobacteriaceae found in the bile. The proposed antibiotic prophylaxis is presented in Figure 2. In line with the European Medicine Agency’s opinion published in “Quinolone and fluoroquinolone Article-31 referral outcome” (EMA/175398/2019), we do not recommend ciprofloxacin as a first line in prophylaxis due to the risk of potentially irreversible adverse drug reactions related to the use of fluoroquinolones, as well as the risk of Clostridioides difficile infection [46]. In case of incomplete biliary drainage, antibiotics used for prophylaxis should be continued for three days. If there is no evidence of cholangitis, antibiotics may be discontinued.

Figure 2.

Antibiotic prophylaxis prior to ERCP.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization and methodology, M.K. and A.P.; data curation, M.K.; writing—original draft preparation, M.K.; writing—review and editing, M.K. and A.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

All data are available in Pub-Med, Medline, and Embase.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Subhani, J.M.; Kibbler, C.; Dooley, J.S. Review article: Antibiotic prophylaxis for endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP). Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 1999, 13, 103–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ceyssens, C.; Frans, J.M.; Christiaens, P.S.; Van Steenbergen, W.; Peetermans, W.E. Recommendations for antibiotic prophylaxis before ERCP: Can we come to workable conclusions after review of the literature? Acta Clin. Belg. 2006, 61, 10–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Merchan, M.F.S.; de Moura, D.T.H.; de Oliveira, G.H.P.; Proença, I.M.; do Monte Junior, E.S.; Ide, E.; Moll, C.; Sánchez-Luna, S.A.; Bernardo, W.M.; de Moura, E.G.H. Antibiotic prophylaxis to prevent complications in endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. World J. Gastrointest. Endosc. 2022, 14, 718–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Csendes, A.; Fernandez, M.; Uribe, P. Bacteriology of the gallbladder bile in normal subjects. Am. J. Surg. 1975, 129, 629–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mani, V.; Cartwright, K.; Dooley, J.; Swarbrick, E.; Fairclough, P.; Oakley, C. Antibiotic prophylaxis in gastrointestinal endoscopy: A report by a Working Party for the British Society of Gastroenterology Endoscopy Committee. Endoscopy 1997, 29, 114–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dowidar, N.; Kolmos, H.J.; Lyon, H.; Matzen, P. Clogging of biliary endoprostheses. A morphologic and bacteriologic study. Scand. J. Gastroenterol. 1991, 26, 1137–1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hancke, E.; Marklein, G.; Helpap, B. Route of infection of the biliary tract: Experimental evidence for an enterohepaticobiliary bacterial cycle (author’s transl). Langenbecks Arch. Chir. 1980, 353, 121–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sand, J.; Airo, I.; Hiltunen, K.M.; Mattila, J.; Nordback, I. Changes in biliary bacteria after endoscopic cholangiography and sphincterotomy. Am. Surg. 1992, 58, 324–328. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Allison, M.C.; Sandoe, J.A.; Tighe, R.; Simpson, I.A.; Hall, R.J.; Elliott, T.S. Endoscopy Committee of the British Society of, G. Antibiotic prophylaxis in gastrointestinal endoscopy. Gut 2009, 58, 869–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khashab, M.A.; Chithadi, K.V.; Acosta, R.D.; Bruining, D.H.; Chandrasekhara, V.; Eloubeidi, M.A.; Fanelli, R.D.; Faulx, A.L.; Fonkalsrud, L.; Lightdale, J.R.; et al. Antibiotic prophylaxis for GI endoscopy. Gastrointest. Endosc. 2015, 81, 81–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, G.J. Dentists are innocent! "Everyday" bacteremia is the real culprit: A review and assessment of the evidence that dental surgical procedures are a principal cause of bacterial endocarditis in children. Pediatr. Cardiol. 1999, 20, 317–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maluenda, F.; Csendes, A.; Burdiles, P.; Diaz, J. Bacteriological study of choledochal bile in patients with common bile duct stones, with or without acute suppurative cholangitis. Hepatogastroenterology 1989, 36, 132–135. [Google Scholar]

- Pitt, H.A.; Postier, R.G.; Cameron, J.L. Biliary bacteria: Significance and alterations after antibiotic therapy. Arch. Surg. 1982, 117, 445–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leung, J.W.; Ling, T.K.; Chan, R.C.; Cheung, S.W.; Lai, C.W.; Sung, J.J.; Chung, S.C.; Cheng, A.F. Antibiotics, biliary sepsis, and bile duct stones. Gastrointest. Endosc. 1994, 40, 716–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meijer, W.S.; Schmitz, P.I. Prophylactic use of cefuroxime in biliary tract surgery: Randomized controlled trial of single versus multiple dose in high-risk patients. Galant Trial Study Group. Br. J. Surg. 1993, 80, 917–921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bilbao, M.K.; Dotter, C.T.; Lee, T.G.; Katon, R.M. Complications of endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP). A study of 10,000 cases. Gastroenterology 1976, 70, 314–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez, S.R.; Trujillo Ceballos, A.A.; Montaño Rozo, G.A., Sr.; Solano Mariño, J.; Carias Domínguez, A.M.; Vera Chamorro, J.F. Endoscopic Retrograde Cholangiopancreatography in Children: Nine Years’ Experience at Santa Fe Foundation in Bogota, Colombia. Cureus 2023, 15, e41835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Norouzi, A.; Khatibian, M.; Afroogh, R.; Chaharmahali, M.; Sotoudehmanesh, R. The effect of adding gentamicin to contrast media for prevention of cholangitis after biliary stenting for non-calculous biliary obstruction, a randomized controlled trial. Indian J. Gastroenterol. 2013, 32, 18–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gustafsson, A.; Enochsson, L.; Tingstedt, B.; Olsson, G. Antibiotic prophylaxis and its effect on postprocedural adverse events in endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography for primary sclerosing cholangitis. JGH Open 2023, 7, 24–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niederau, C.; Pohlmann, U.; Lübke, H.; Thomas, L. Prophylactic antibiotic treatment in therapeutic or complicated diagnostic ERCP: Results of a randomized controlled clinical study. Gastrointest. Endosc. 1994, 40, 533–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratanachu-ek, T.; Prajanphanit, P.; Leelawat, K.; Chantawibul, S.; Panpimanmas, S.; Subwongcharoen, S.; Wannaprasert, J. Role of ciprofloxacin in patients with cholestasis after endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography. World J. Gastroenterol. 2007, 13, 276–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finkelstein, R.; Yassin, K.; Suissa, A.; Lavy, A.; Eidelman, S. Failure of cefonicid prophylaxis for infectious complications related to endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography. Clin. Infect. Dis. 1996, 23, 378–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorenz, R.; Lehn, N.; Born, P.; Herrmann, M.; Neuhaus, H. Antibiotic prophylaxis using cefuroxime in bile duct endoscopy. Dtsch. Med. Wochenschr. 1996, 121, 223–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Räty, S.; Sand, J.; Pulkkinen, M.; Matikainen, M.; Nordback, I. Post-ERCP pancreatitis: Reduction by routine antibiotics. J. Gastrointest. Surg. 2001, 5, 339–345; discussion 345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leem, G.; Sung, M.J.; Park, J.H.; Kim, S.J.; Jo, J.H.; Lee, H.S.; Ku, N.S.; Park, J.Y.; Bang, S.; Park, S.W.; et al. Randomized Trial of Prophylactic Antibiotics for Endoscopic Retrograde Cholangiopancreatography in Patients With Biliary Obstruction. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2024, 119, 183–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spicak, J.; Stirand, P.; Zavoral, M.; Keil, R.; Zavada, F.; Drabek, J. Antibiotic prophylaxis of cholangitis complicating endoscopic management of biliary ebstruction. Gastrointest. Endosc. 2001, 55, 211–215. [Google Scholar]

- Llach, J.; Bordas, J.M.; Almela, M.; Pellisé, M.; Mata, A.; Soria, M.; Fernández-Esparrach, G.; Ginès, A.; Elizalde, J.I.; Feu, F.; et al. Prospective assessment of the role of antibiotic prophylaxis in ERCP. Hepatogastroenterology 2006, 53, 540–542. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, B.C.; Alqamish, J.R.; Watson, K.J.; Shaw, R.G.; Andrew, J.H.; Desmond, P.V. Preventing endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography related sepsis: A randomized controlled trial comparing two antibiotic regimes. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 1996, 11, 938–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van den Hazel, S.J.; Speelman, P.; Dankert, J.; Huibregtse, K.; Tytgat, G.N.; van Leeuwen, D.J. Piperacillin to prevent cholangitis after endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography. A randomized, controlled trial. Ann. Intern. Med. 1996, 125, 442–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Byl, B.; Deviere, J.; Struelens, M.J.; Roucloux, I.; De Coninck, A.; Thys, J.P.; Cremer, M. Antibiotic prophylaxis for infectious complications after therapeutic endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Clin. Infect. Dis. 1995, 20, 1236–1240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehal, W.Z.; Culshaw, K.D.; Tillotson, G.S.; Chapman, R.W. Antibiotic prophylaxis for ERCP: A randomized clinical trial comparing ciprofloxacin and cefuroxime in 200 patients at high risk of cholangitis. Eur. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 1995, 7, 841–845. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Davis, A.J.; Kolios, G.; Alveyn, C.G.; Robertson, D.A. Antibiotic prophylaxis for ERCP: A comparison of oral ciprofloxacin with intravenous cephazolin in the prophylaxis of high-risk patients. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 1998, 12, 207–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, N.H.; Kim, H.J.; Bang, K.B. Prospective comparison of prophylactic antibiotic use between intravenous moxifloxacin and ceftriaxone for high-risk patients with post-ERCP cholangitis. Hepatobiliary Pancreat. Dis. Int. 2017, 16, 512–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, B.F.; Arguedas, M.R.; Wilcox, C.M. Antibiotic prophylaxis prior to endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography in patients with obstructive jaundice: Is it worth the cost? Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2002, 16, 727–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Pohl, J.; Ring, A.; Stremmel, W.; Stiehl, A. The role of dominant stenoses in bacterial infections of bile ducts in primary sclerosing cholangitis. Eur. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2006, 18, 69–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olsson, G.; Arnelo, U.; Lundell, L.; Persson, G.; Törnqvist, B.; Enochsson, L. The role of antibiotic prophylaxis in routine endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography investigations as assessed prospectively in a nationwide study cohort. Scand. J. Gastroenterol. 2015, 50, 924–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turowski, F.; Hügle, U.; Dormann, A.; Bechtler, M.; Jakobs, R.; Gottschalk, U.; Nötzel, E.; Hartmann, D.; Lorenz, A.; Kolligs, F.; et al. Diagnostic and therapeutic single-operator cholangiopancreatoscopy with SpyGlassDS™: Results of a multicenter retrospective cohort study. Surg. Endosc. 2018, 32, 3981–3988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sciumè, C.; Geraci, G.; Pisello, F.; Facella, T.; Li Volsi, F.; Modica, G. Prevention of clogging of biliary stents by administration of levofloxacin and ursodeoxycholic acid. Chir. Ital. 2004, 56, 831–837. [Google Scholar]

- Marek, T.; Nowakowska-Duława, E.; Baniukiewicz, A.; Kurek, K.; Białek, A.; Milewski, J.; Pertkiewicz, J.; Reguła, J.; Smoczyński, M.; Kulig, J.; et al. Quality Indicators for Endoscopic Retrograde Cholangiopancreatography—Guidelines from the Polish Society of Gastroenterology and the Association of Polish Surgeons; Polish Society of Gastroenterology and the Association of Polish Surgeons: Warsaw, Poland, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- van Wanrooij, R.L.J.; Bronswijk, M.; Kunda, R.; Everett, S.M.; Lakhtakia, S.; Rimbas, M.; Hucl, T.; Badaoui, A.; Law, R.; Arcidiacono, P.G.; et al. Therapeutic endoscopic ultrasound: European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) Technical Review. Endoscopy 2022, 54, 310–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devlin, T.B. Canadian Association.of Gastroenterology Practice Guidelines: Antibiotic prophylaxis.for gastrointestinal endoscopy. Can. J. Gastroeneterol. 1999, 13, 819–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Kang, S.H.; Hyun, J.J. Preparation and patient evaluation for safe gastrointestinal endoscopy. Clin. Endosc. 2013, 46, 212–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tringali, A.; Thomson, M.; Dumonceau, J.M.; Tavares, M.; Tabbers, M.M.; Furlano, R.; Spaander, M.; Hassan, C.; Tzvinikos, C.; Ijsselstijn, H.; et al. Pediatric gastrointestinal endoscopy: European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) and European Society for Paediatric Gastroenterology Hepatology and Nutrition (ESPGHAN) Guideline Executive summary. Endoscopy 2017, 49, 83–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brand, M.; Bizos, D.; O’Farrell, P., Jr. Antibiotic prophylaxis for patients undergoing elective endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2010, cd007345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Usatin, D.; Fernandes, M.; Allen, I.E.; Perito, E.R.; Ostroff, J.; Heyman, M.B. Complications of Endoscopic Retrograde Cholangiopancreatography in Pediatric Patients; A Systematic Literature Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Pediatr. 2016, 179, 160–165.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazakova, S.V.; Baggs, J.; McDonald, L.C.; Yi, S.H.; Hatfield, K.M.; Guh, A.; Reddy, S.C.; Jernigan, J.A. Association Between Antibiotic Use and Hospital-onset Clostridioides difficile Infection in US Acute Care Hospitals, 2006–2012: An Ecologic Analysis. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2020, 70, 11–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).