Prognostic Utility of the Modified Systemic Inflammation Score for Patients Undergoing Oral Cavity Cancer Surgery

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Cohort

2.2. Data Collection

2.3. Treatment Protocol

2.4. Laboratory Measurements

2.5. Follow-Up and Study Endpoints

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Patient Characteristics

3.2. Association Between Clinicopathological Characteristics and mSIS

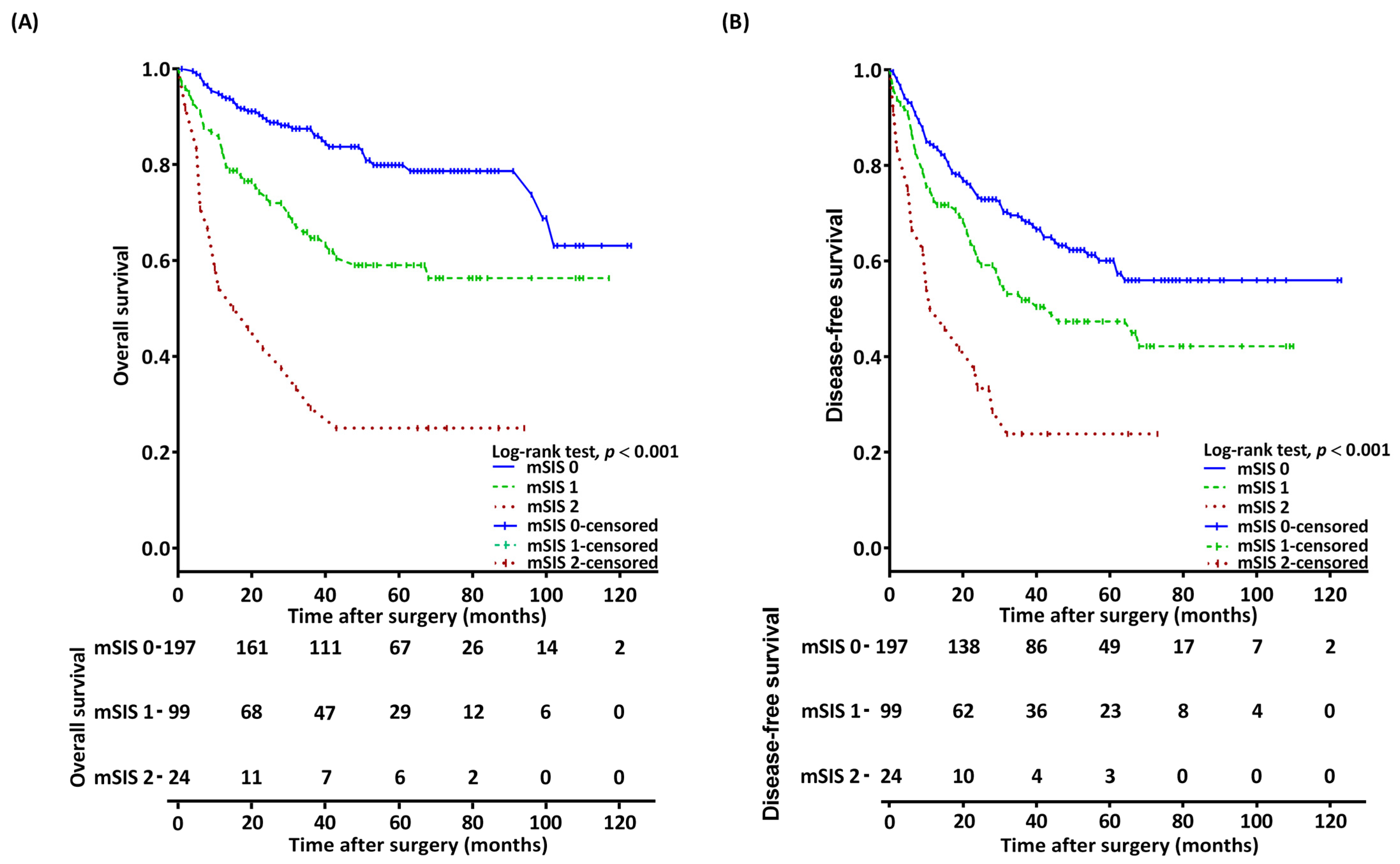

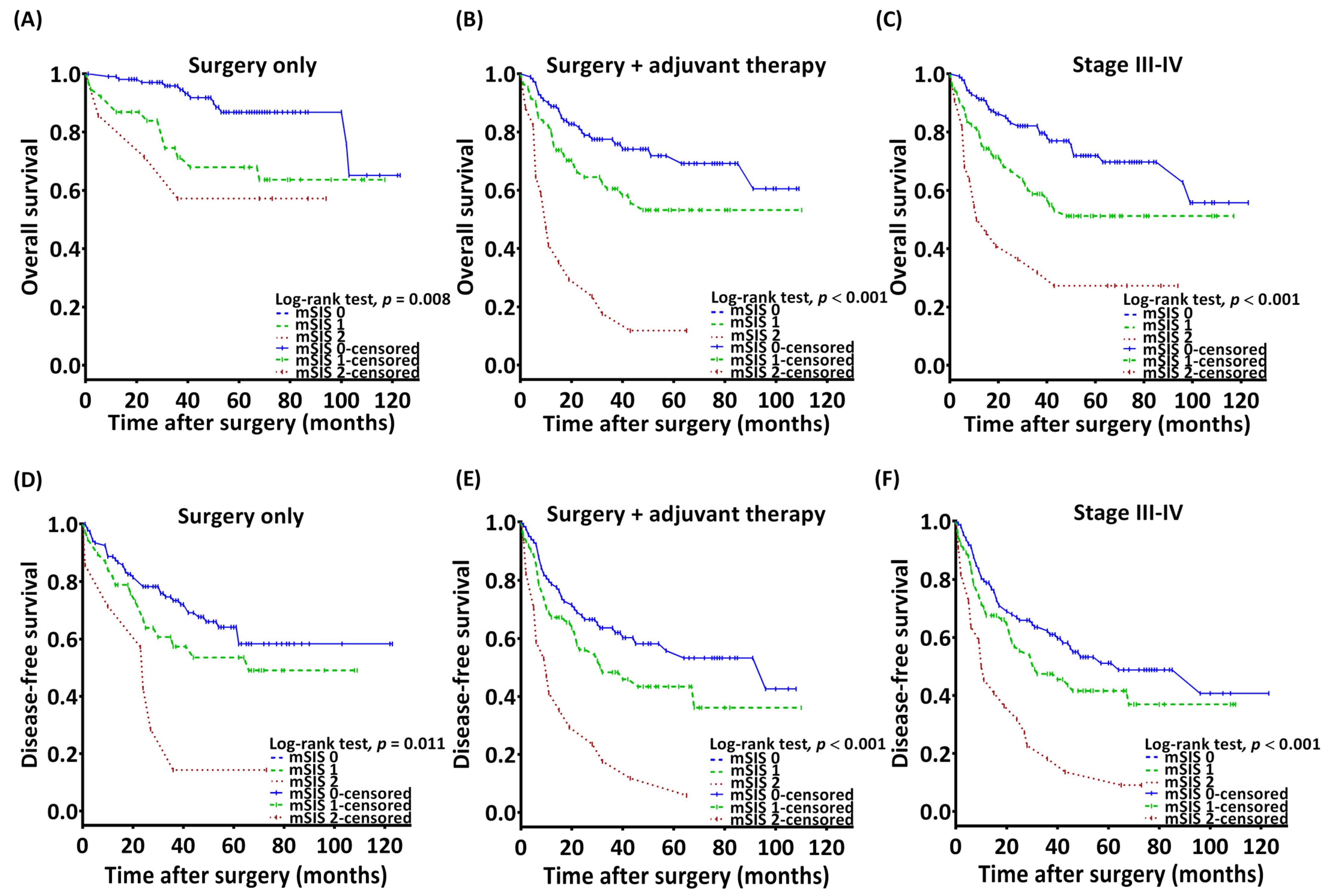

3.3. Association Between mSIS and OS

3.4. Association Between mSIS and DFS

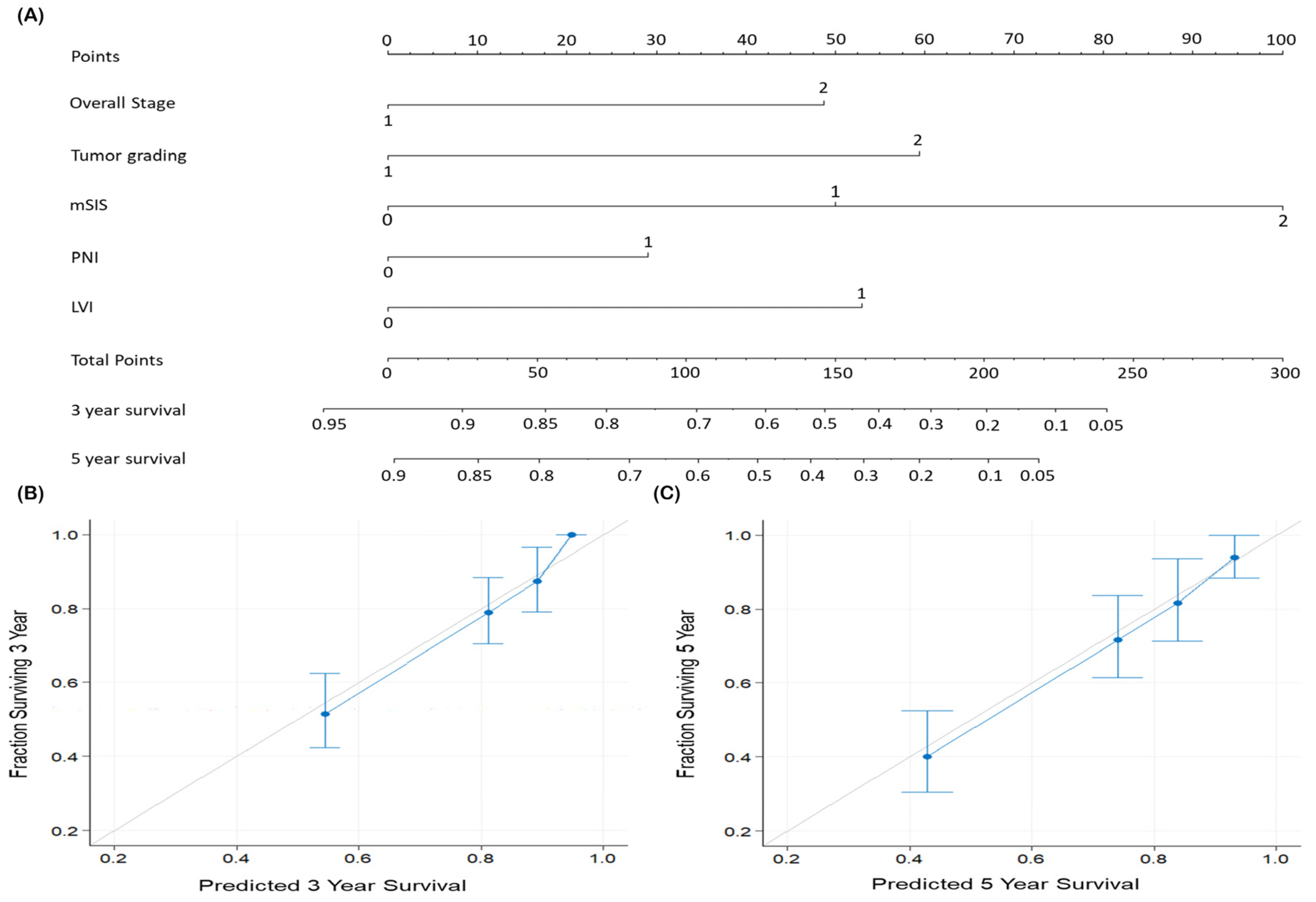

3.5. Predictive Nomogram

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mody, M.D.; Rocco, J.W.; Yom, S.S.; Haddad, R.I.; Saba, N.F. Head and neck cancer. Lancet 2021, 398, 2289–2299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alshami, M.L.; Al-Maliky, M.A.; Alsagban, A.A.; Alshaeli, A.J. Epidemiology and incidence of oral squamous cell carcinoma in the Iraqi population over 5 years (2014–2018). Health Sci. Rep. 2023, 6, e1205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, S.W.; Hsu, C.M.; Tsai, Y.H.; Chang, G.H.; Tsai, M.S.; Huang, E.I.; Tsai, Y.T. Prognostic Value of Third Cervical Vertebra Skeletal Muscle Index in Oral Cavity Cancer: A Retrospective Study. Laryngoscope 2021, 131, E2257–E2265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kao, H.K.; Löfstrand, J.; Loh, C.Y.Y.; Lao, W.W.K.; Yi, J.S.; Chang, Y.L.; Chang, K.P. Nomogram based on albumin and neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio for predicting the prognosis of patients with oral cavity squamous cell carcinoma. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 13081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raj, L.S.M.; Boaz, K.; Natarajan, S. Prognostic Significance of Lymph Node Pattern in Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma (OSCC). J. Clin. Diagn. Res. 2014, 8, 232–235. [Google Scholar]

- Mantovani, A.; Allavena, P.; Sica, A.; Balkwill, F. Cancer-related inflammation. Nature 2008, 454, 436–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siddhartha, R.; Garg, M. Interplay Between Extracellular Matrix Remodeling and Angiogenesis in Tumor Ecosystem. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2023, 22, 291–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fang, K.H.; Chang, S.W.; Lee, Y.C.; Huang, E.I.; Lai, C.H.; Chang, G.H.; Tsai, M.S.; Hsu, C.M.; Tsai, Y.T. Preoperative prognostic nutritional index predicts prognosis of patients with oral cavity cancer. Oral Dis. 2022, 28, 1816–1830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McMillan, D.C. An inflammation-based prognostic score and its role in the nutrition-based management of patients with cancer. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 2008, 67, 257–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMillan, D.C. The systemic inflammation-based Glasgow Prognostic Score: A decade of experience in patients with cancer. Cancer Treat. Rev. 2013, 39, 534–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grimm, M.; Rieth, J.; Hoefert, S.; Krimmel, M.; Rieth, S.; Teriete, P.; Kluba, S.; Biegner, T.; Munz, A.; Reinert, S. Standardized pretreatment inflammatory laboratory markers and calculated ratios in patients with oral squamous cell carcinoma. Eur. Arch. Otorhinolaryngol. 2016, 273, 3371–3384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keller, U. Nutritional Laboratory Markers in Malnutrition. J. Clin. Med. 2019, 8, 775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Danan, D.; Shonka, D.C.; Selman, Y.; Chow, Z.; Smolkin, M.E.; Jameson, M.J. Prognostic value of albumin in patients with head and neck cancer. Laryngoscope 2016, 126, 1567–1571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eltohami, Y.I.; Kao, H.K.; Lao, W.W.K.; Huang, Y.L.; Abdelrahman, M.; Liao, C.T.; Yen, T.C.; Chang, K.P. The Prediction Value of the Systemic Inflammation Score for Oral Cavity Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2018, 158, 1042–1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, J.X.; Lin, J.P.; Xie, J.W.; Wang, J.B.; Lu, J.; Chen, Q.Y.; Cao, L.L.; Lin, M.; Tu, R.H.; Zheng, C.H.; et al. Prognostic importance of the preoperative modified systemic inflammation score for patients with gastric cancer. Gastric Cancer 2019, 22, 403–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ataş, H.; Korukluoğlu, B.; Özdemir, B.A.; Yakşi, N.; Saylam, B.; Tez, M. Diagnostic value of modified systemic inflammation score for prediction of malignancy in patients with indeterminate thyroid nodules. Am. J. Surg. 2021, 221, 117–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, F.; Chen, L.; Wang, Z.; Xu, Q.; Huang, H.; Wang, H.; Li, X.; Yu, M.; Chen, J.; Lin, F.; et al. Prognostic value of the modified systemic inflammation score in non-small-cell lung cancer with brain metastasis. Cancer Cell Int. 2022, 22, 320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolffe, A.P.; Brown, D.D. Developmental regulation of two 5S ribosomal RNA genes. Science 1988, 241, 1626–1632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bannay, A.; Chaignot, C.; Blotière, P.O.; Basson, M.; Weill, A.; Ricordeau, P.; Alla, F. The Best Use of the Charlson Comorbidity Index with Electronic Health Care Database to Predict Mortality. Med. Care 2016, 54, 188–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.Y.; Fan, K.H.; Lee, L.Y.; Hsueh, C.; Yang, L.Y.; Ng, S.H.; Wang, H.M.; Hsieh, C.H.; Lin, C.H.; Tsao, C.K.; et al. Precision Adjuvant Therapy Based on Detailed Pathologic Risk Factors for Resected Oral Cavity Squamous Cell Carcinoma: Long-Term Outcome Comparison of CGMH and NCCN Guidelines. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2020, 106, 916–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Z.; Kattan, M.W. Drawing Nomograms with R: Applications to categorical outcome and survival data. Ann. Transl. Med. 2017, 5, 211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Molinero, J.; Migueláñez-Medrán, B.D.C.; Puente-Gutiérrez, C.; Delgado-Somolinos, E.; Carreras-Presas, C.M.; Fernández-Farhall, J.; López-Sánchez, A.F. Association between Oral Cancer and Diet: An Update. Nutrients 2021, 13, 1299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moeckelmann, N.; Ebrahimi, A.; Tou, Y.K.; Gupta, R.; Low, T.H.H.; Ashford, B.; Ch’ng, S.; Palme, C.E.; Clark, J.R. Prognostic implications of the 8th edition American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) staging system in oral cavity squamous cell carcinoma. Oral Oncol. 2018, 85, 82–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bao, X.; Liu, F.; Lin, J.; Chen, Q.; Chen, L.; Chen, F.; Wang, J.; Qiu, Y.; Shi, B.; Pan, L.; et al. Nutritional assessment and prognosis of oral cancer patients: A large-scale prospective study. BMC Cancer 2020, 20, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, C.; Wang, M.; Zhang, H.; Li, C.; Zhang, T.; Liu, H.; Zhu, S.; Chen, J. Tumor microenvironment and immunotherapy of oral cancer. Eur. J. Med. Res. 2022, 27, 198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hasegawa, T.; Iga, T.; Takeda, D.; Amano, R.; Saito, I.; Kakei, Y.; Kusumoto, J.; Kimoto, A.; Sakakibara, A.; Akashi, M. Neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio associated with poor prognosis in oral cancer: A retrospective study. BMC Cancer 2020, 20, 568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galizia, G.; Lieto, E.; Zamboli, A.; De Vita, F.; Castellano, P.; Romano, C.; Auricchio, A.; Cardella, F.; De Stefano, L.; Orditura, M. Neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio is a strong predictor of tumor recurrence in early colon cancers: A propensity score-matched analysis. Surgery 2015, 158, 112–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suzuki, Y.; Okabayashi, K.; Hasegawa, H.; Tsuruta, M.; Shigeta, K.; Kondo, T.; Kitagawa, Y. Comparison of Preoperative Inflammation-based Prognostic Scores in Patients with Colorectal Cancer. Ann. Surg. 2018, 267, 527–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, J.; Kang, W.; Ma, F.; Liu, H.; Ma, S.; Li, Y.; Jin, P.; Hu, H.; Tian, Y. Modified Systemic Inflammation Score Is an Independent Predictor of Long-Term Outcome in Patients Undergoing Surgery for Adenocarcinoma of the Esophagogastric Junction. Front. Surg. 2021, 8, 622821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanda, M.; Koike, M.; Tanaka, C.; Kobayashi, D.; Hattori, N.; Hayashi, M.; Yamada, S.; Omae, K.; Fujiwara, M.; Kodera, Y. Modified Systemic Inflammation Score is Useful for Risk Stratification After Radical Resection of Squamous Cell Carcinoma of the Esophagus. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2019, 26, 4773–4781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fridman, W.H.; Zitvogel, L.; Sautès-Fridman, C.; Kroemer, G. The immune contexture in cancer prognosis and treatment. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2017, 14, 717–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farhood, B.; Najafi, M.; Mortezaee, K. CD8(+) cytotoxic T lymphocytes in cancer immunotherapy: A review. J. Cell. Physiol. 2019, 234, 8509–8521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, W.; Li, X.; Wang, H.; Nie, K.; Meng, Q.; He, J.; Zheng, C. Puerarin: A Potential Therapeutic for SARS-CoV-2 and Hantavirus Co-Infection. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 892350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thommen, D.S.; Schreiner, J.; Müller, P.; Herzig, P.; Roller, A.; Belousov, A.; Umana, P.; Pisa, P.; Klein, C.; Bacac, M.; et al. Progression of Lung Cancer Is Associated with Increased Dysfunction of T Cells Defined by Coexpression of Multiple Inhibitory Receptors. Cancer Immunol. Res. 2015, 3, 1344–1355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olingy, C.E.; Dinh, H.Q.; Hedrick, C.C. Monocyte heterogeneity and functions in cancer. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2019, 106, 309–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porrello, A.; Leslie, P.L.; Harrison, E.B.; Gorentla, B.K.; Kattula, S.; Ghosh, S.K.; Azam, S.H.; Holtzhausen, A.; Chao, Y.L.; Hayward, M.C.; et al. Factor XIIIA-expressing inflammatory monocytes promote lung squamous cancer through fibrin cross-linking. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 1988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yona, S.; Kim, K.W.; Wolf, Y.; Mildner, A.; Varol, D.; Breker, M.; Strauss-Ayali, D.; Viukov, S.; Guilliams, M.; Misharin, A.; et al. Fate mapping reveals origins and dynamics of monocytes and tissue macrophages under homeostasis. Immunity 2013, 38, 79–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wan, L.; Wu, C.; Luo, S.; Xie, X. Prognostic Value of Lymphocyte-to-Monocyte Ratio (LMR) in Cancer Patients Undergoing Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors. Dis. Markers 2022, 2022, 3610038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arroyo, V.; Garcia-Martinez, R.; Salvatella, X. Human serum albumin, systemic inflammation, and cirrhosis. J. Hepatol. 2014, 61, 396–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, S.; Guelrud, M.; Plaut, A. Odynophagia after upper endoscopy: An unusual finding. Gastroenterology 2013, 145, 913–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seaton, K. Albumin concentration controls cancer. J. Natl. Med. Assoc. 2001, 93, 490–493. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Wiedermann, C.J. Hypoalbuminemia as Surrogate and Culprit of Infections. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 4496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsai, Y.T.; Lai, C.H.; Huang, T.H.; Hsieh, C.C.; Huang, E.I.; Lee, Y.C.; Yeh, H.K.; Tsai, M.S.; Chang, G.H.; Hsu, C.M. Association of malnutrition with postoperative complication risk after curative surgery for oral cancer: Observational study. Medicine 2020, 99, e23860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, M.H.; Chuang, H.C.; Lin, Y.T.; Lu, H.; Chen, W.C.; Fang, F.M.; Chien, C.Y. Clinical impact of albumin in advanced head and neck cancer patients with free flap reconstruction—A retrospective study. PeerJ 2018, 6, e4490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, S.; Kim, D.W.; Kwon, S.; Kim, H.J.; Cha, I.H.; Nam, W. Prognostic value of systemic inflammatory markers for oral cancer patients based on the 8th edition of AJCC staging system. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 12111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vano, Y.A.; Oudard, S.; By, M.A.; Têtu, P.; Thibault, C.; Aboudagga, H.; Scotté, F.; Elaidi, R. Optimal cut-off for neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio: Fact or Fantasy? A prospective cohort study in metastatic cancer patients. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0195042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variable | Total, n (%) | mSIS 0 (n = 197) | mSIS 1 (n = 99) | mSIS 2 (n =24) | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 0.500 a | ||||

| <65 | 203 (63.4%) | 129 (65.5%) | 61 (61.6%) | 13 (54.2%) | |

| ≥65 | 117 (36.6%) | 68 (34.5%) | 38 (38.4%) | 11 (45.8%) | |

| Sex | 0.197 a | ||||

| Men | 289 (90.3%) | 178 (90.4%) | 87 (87.9%) | 24 (100.0%) | |

| Women | 31 (9.7%) | 19 (9.6%) | 12 (12.1%) | 0 (0.0%) | |

| Tumor location | 0.079 a | ||||

| Tongue | 125 (39.1%) | 85 (43.1%) | 31 (31.3%) | 9 (37.5%) | |

| Buccal mucosa | 102 (31.9%) | 61 (31.0%) | 30 (30.3%) | 11 (45.8%) | |

| Gingiva | 42 (13.1%) | 21 (10.7%) | 20 (20.2%) | 1 (4.2%) | |

| Retromolar trigone | 19 (5.9%) | 12 (6.1%) | 5 (5.1%) | 2 (8.3%) | |

| Lip | 13 (4.1%) | 6 (3.0%) | 7 (7.1%) | 0 (0.0%) | |

| Mouth floor | 13 (4.1%) | 6 (3.0%) | 6 (6.1%) | 1 (4.2%) | |

| Hard palate | 6 (1.9%) | 6 (3.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | |

| Personal Habits * | 0.130 a | ||||

| No exposure | 38 (11.9%) | 27 (13.7%) | 11 (11.1%) | 0 (0.0%) | |

| One exposure | 18 (5.6%) | 8 (4.1%) | 9 (9.1%) | 1 (4.2%) | |

| Two or all exposure | 264 (82.5%) | 162 (82.2%) | 79 (79.8%) | 23 (95.8%) | |

| AJCC stage | <0.001 a | ||||

| I–II | 110 (34.4%) | 83 (42.1%) | 25 (25.3%) | 2 (8.3%) | |

| III–IV | 210 (65.6%) | 114 (57.9%) | 74 (74.7%) | 22 (91.7%) | |

| T status | <0.001 a | ||||

| T1–T2 | 144 (45.0%) | 107 (54.3%) | 32 (32.3%) | 5 (20.8%) | |

| T3–T4 | 176 (55.0%) | 90 (45.7%) | 67 (67.7%) | 19 (79.2%) | |

| N status | 0.019 a | ||||

| N0 | 206 (64.4%) | 136 (69.0%) | 60 (60.6%) | 10 (41.7%) | |

| N+ | 114 (35.6%) | 61 (31.0%) | 39 (39.4%) | 14 (58.3%) | |

| Presence of PNI | 0.614 a | ||||

| No | 241 (75.3%) | 152 (77.2%) | 72 (72.7%) | 17 (70.8%) | |

| Yes | 79 (24.7%) | 45 (22.8%) | 27 (27.3%) | 7 (29.2%) | |

| Presence of ENE | 0.040 a | ||||

| No | 255 (79.7%) | 164 (83.2%) | 76 (76.8%) | 15 (62.5%) | |

| Yes | 65 (20.3%) | 33 (16.8%) | 23 (23.2%) | 9 (37.5%) | |

| Presence of LVI | 0.050 a | ||||

| No | 298 (93.1%) | 188 (95.4%) | 90 (90.9%) | 20 (83.3%) | |

| Yes | 22 (6.9%) | 9 (4.6%) | 9 (9.1%) | 4 (16.7%) | |

| Tumor grading | 0.540 a | ||||

| W–D/M–D | 283 (88.4%) | 177 (89.8%) | 86 (86.9%) | 20 (83.3%) | |

| P–D | 37 (11.6%) | 20 (10.2%) | 13 (13.1%) | 4 (16.7%) | |

| Closest resection margin | 0.867 a | ||||

| ≥5 mm | 234 (73.1%) | 55 (27.9%) | 25 (25.3%) | 6 (25.0%) | |

| <5 mm | 86 (26.9%) | 142 (72.1%) | 74 (74.7%) | 18 (75.0%) | |

| DOI ≥ 10 mm | <0.001 a | ||||

| No | 168 (52.5%) | 123 (62.4%) | 39 (39.4%) | 6 (25.0%) | |

| Yes | 152 (47.5%) | 74 (37.6%) | 60 (60.6%) | 18 (75.0%) | |

| Treatment modality | 0.001 a | ||||

| Surgery only | 152 (47.5%) | 107 (54.3%) | 38 (38.4%) | 7 (29.2%) | |

| Surgery then RT | 44 (13.8%) | 27 (13.7%) | 17 (17.2%) | 0 (0.0%) | |

| Surgery then CRT | 124 (38.8%) | 63 (32.0%) | 44 (44.4%) | 17 (70.8%) | |

| CCI | 0.255 a | ||||

| 0 | 171 (53.4%) | 109 (55.3%) | 53 (53.5%) | 9 (37.5%) | |

| ≥1 | 149 (46.6%) | 88 (44.7%) | 46 (46.5%) | 15 (62.5%) | |

| WBC (×103/μL), median (IQR) | 7.8 (6.3–9.7) | 7.5 (6.2–9.2) | 8.8 (6.4–10.6) | 9.9 (7.8–11.9) | 0.093 b |

| Lymphocyte (×10 3/μL), median (IQR) | 2.03 (1.59–2.59) | 2.30 (1.85–2.83) | 1.78 (1.37–2.09) | 1.57 (1.10–2.03) | <0.001 b |

| Monocyte (×10 3/μL), median (IQR) | 435.1 (340.8–580.7) | 388.8 (322.2–490.9) | 560.9 (386.9-678.6) | 595.7 (447.3–752.1) | <0.001 b |

| Albumin (g/L), median (IQR) | 44.3 (41.8–46.7) | 45.70 (43.7–47.2) | 42.01 (38.0–45.0) | 35.85 (31.3–38.2) | <0.001 b |

| LMR, median (IQR) | 4.50 (3.3–6.1) | 5.40 (4.5–6.8) | 3.10 (2.6–3.9) | 2.70 (2.1–3.1) | <0.001 b |

| Variables | Univariable Analysis | Multivariable Analysis | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI) | p-Value | HR (95% CI) | p-Value | ||

| Sex | Men vs. Women | 1.546 (0.713–3.351) | 0.270 | ||

| Age (years) | ≥65 vs. <65 | 0.788 (0.510–1.218) | 0.284 | ||

| cancer stage | III–IV vs. I–II | 3.310 (1.904–5.756) | <0.001 | 2.066 (1.142–3.738) | 0.016 |

| Presence of PNI | Yes vs. no | 2.344 (1.538–3.572) | <0.001 | ||

| Presence of LVI | Yes vs. no | 3.827 (2.112–6.936) | <0.001 | 2.281 (1.191–4.369) | 0.013 |

| Tumor grading | P–D vs. W–D/M–D | 2.934 (1.782–4.831) | <0.001 | 2.417 (1.424–4.043) | 0.001 |

| Closest margin (mm) | <5 vs. ≥5 | 1.445 (0.940–2.220) | 0.093 | ||

| CCI | ≥1 vs. 0 | 1.406 (0.934–2.116) | 0.102 | ||

| mSIS | 1 vs. 0 | 2.310 (1.462–3.617) | <0.001 | 2.021 (1.275–3.204) | 0.003 |

| mSIS | 2 vs. 0 | 6.398 (3.627–11.284) | <0.001 | 5.095 (2.804–9.258) | <0.001 |

| Variables | Univariable Analysis | Multivariable Analysis | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI) | p-Value | HR (95% CI) | p-Value | ||

| Sex | Men vs. Women | 1.442 (0.793–2.621) | 0.232 | ||

| Age (years) | ≥65 vs. <65 | 0.716 (0.505–1.017) | 0.162 | ||

| AJCC stage | III–IV vs. I–II | 2.066 (1.412–3.025) | <0.001 | 1.712 (1.137–2.578) | 0.011 |

| Presence of PNI | Yes vs. no | 1.385 (0.962–1.996) | 0.081 | ||

| Presence of LVI | Yes vs. no | 1.994 (1.124–3.538) | 0.018 | ||

| Tumor grading | P–D vs. W–D/M–D | 2.094 (1.348–3.254) | 0.001 | 2.024 (1.291–3.174) | 0.002 |

| Closest margin (mm) | <5 vs. ≥5 | 1.311 (0.925–1.857) | 0.128 | ||

| CCI | ≥1 vs. 0 | 1.064 (0.691–1.640) | 0.776 | ||

| mSIS | 1 vs. 0 | 1.489 (1.039–2.135) | 0.030 | ||

| mSIS | 2 vs. 0 | 3.904 (2.417–6.307) | <0.001 | 3.590 (2.167–5.947) | <0.001 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Fang, K.-H.; Lo, S.-W.; Kudva, A.; De Vito, A.; Tsai, Y.-H.; Hsu, C.-M.; Chang, G.-H.; Huang, E.I.; Tsai, M.-S.; Lai, C.-H.; et al. Prognostic Utility of the Modified Systemic Inflammation Score for Patients Undergoing Oral Cavity Cancer Surgery. Diagnostics 2024, 14, 2856. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics14242856

Fang K-H, Lo S-W, Kudva A, De Vito A, Tsai Y-H, Hsu C-M, Chang G-H, Huang EI, Tsai M-S, Lai C-H, et al. Prognostic Utility of the Modified Systemic Inflammation Score for Patients Undergoing Oral Cavity Cancer Surgery. Diagnostics. 2024; 14(24):2856. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics14242856

Chicago/Turabian StyleFang, Ku-Hao, Sheng-Wei Lo, Adarsh Kudva, Andrea De Vito, Yuan-Hsiung Tsai, Cheng-Ming Hsu, Geng-He Chang, Ethan I. Huang, Ming-Shao Tsai, Chia-Hsuan Lai, and et al. 2024. "Prognostic Utility of the Modified Systemic Inflammation Score for Patients Undergoing Oral Cavity Cancer Surgery" Diagnostics 14, no. 24: 2856. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics14242856

APA StyleFang, K.-H., Lo, S.-W., Kudva, A., De Vito, A., Tsai, Y.-H., Hsu, C.-M., Chang, G.-H., Huang, E. I., Tsai, M.-S., Lai, C.-H., Tsai, M.-H., Liao, C.-T., Kang, C.-J., & Tsai, Y.-T. (2024). Prognostic Utility of the Modified Systemic Inflammation Score for Patients Undergoing Oral Cavity Cancer Surgery. Diagnostics, 14(24), 2856. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics14242856