The Effectiveness of Mesh-Less Pectopexy in the Treatment of Vaginal Apical Prolapse—A Prospective Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

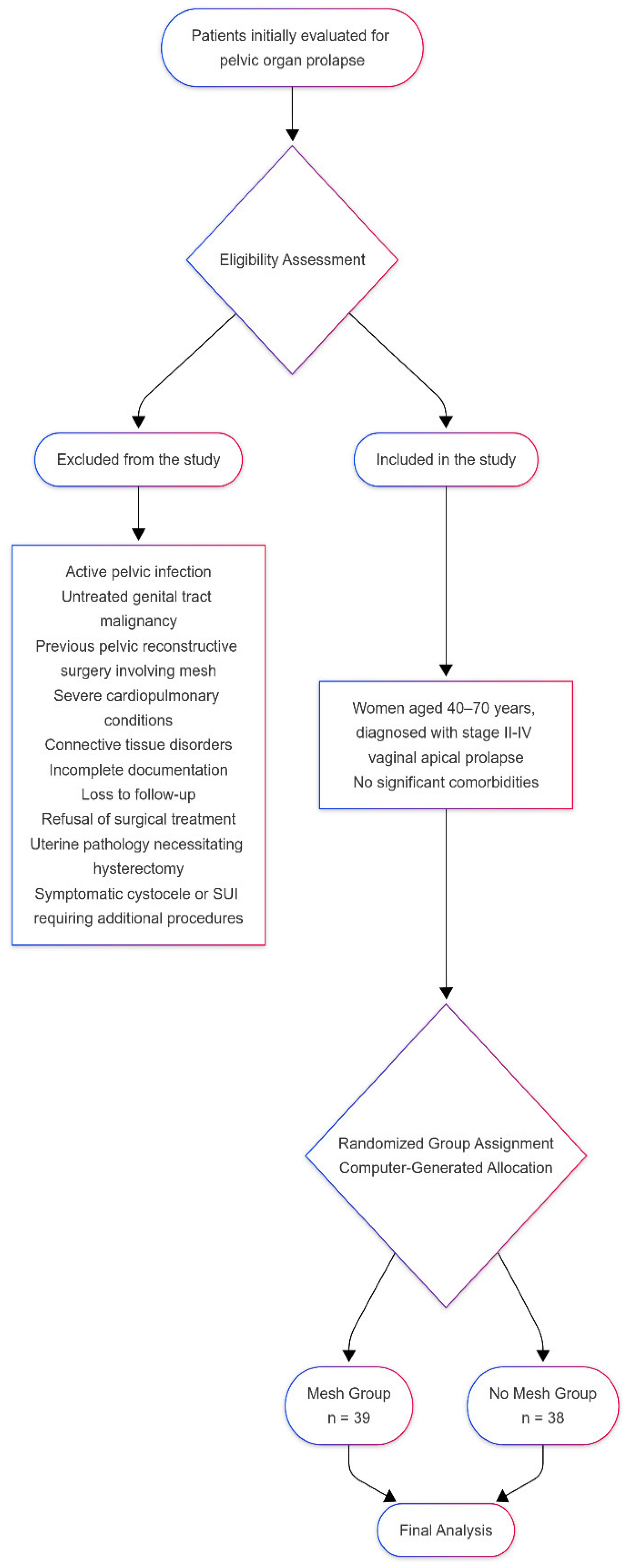

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Patient Selection and Inclusion, Exclusion Criteria

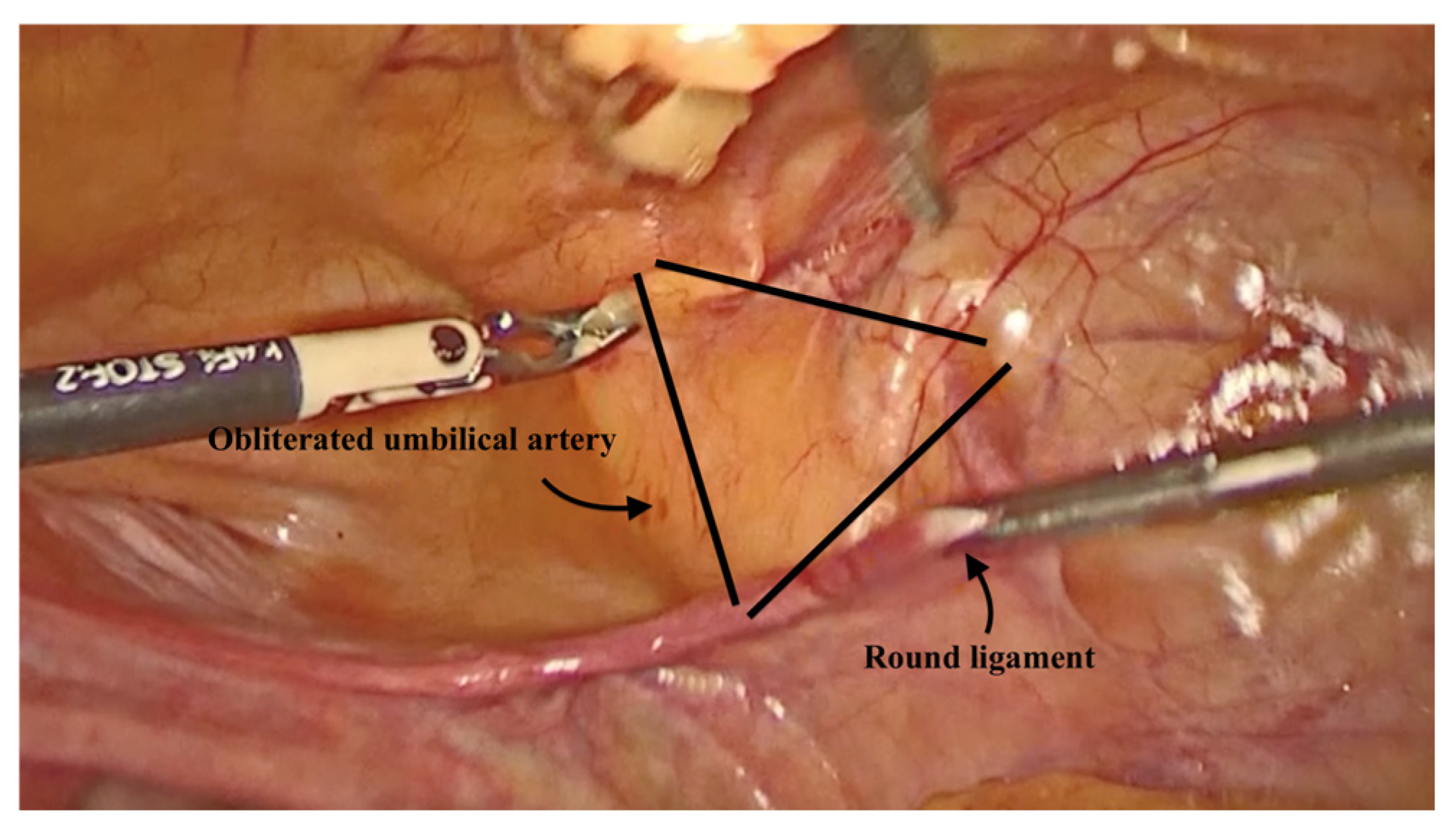

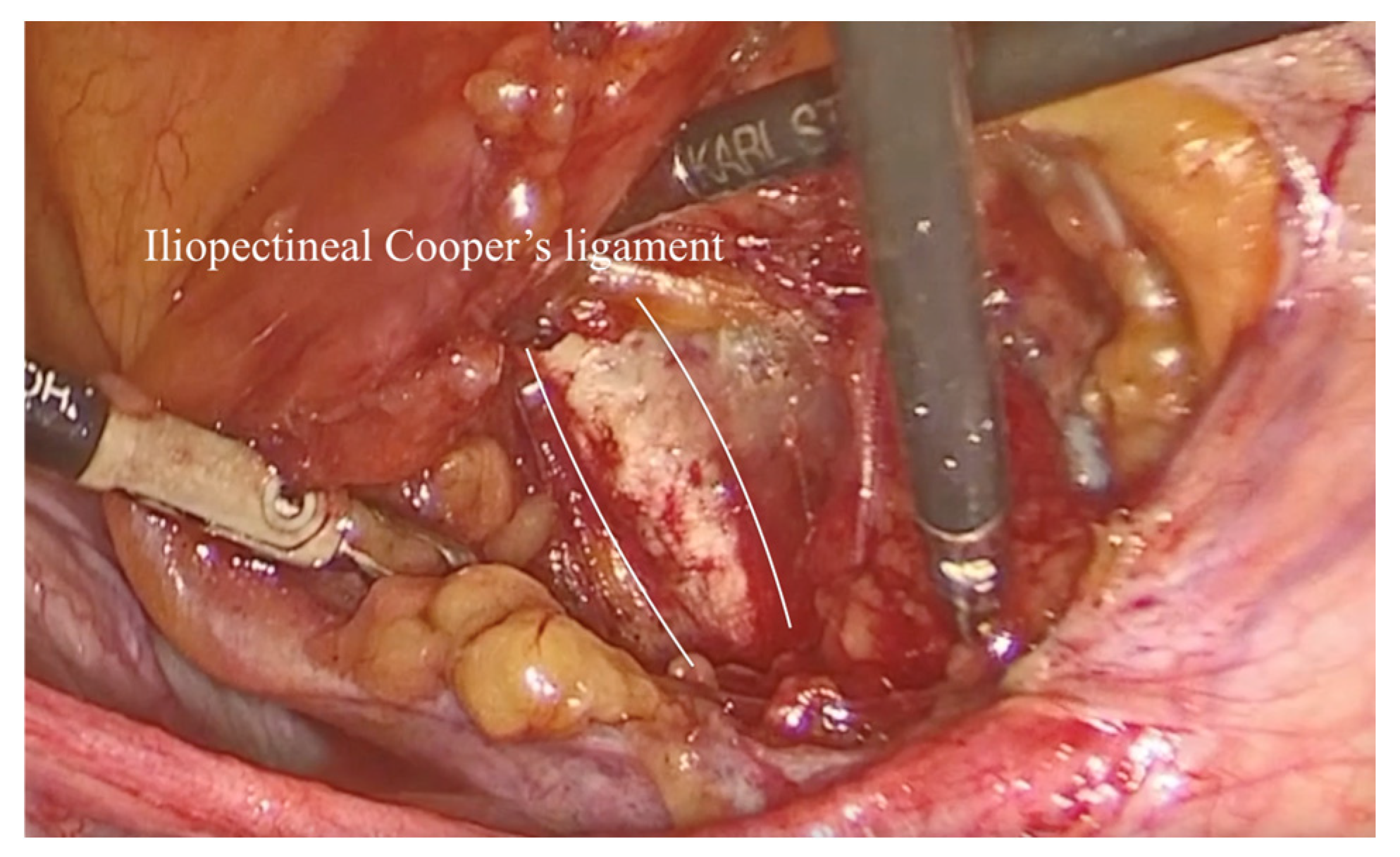

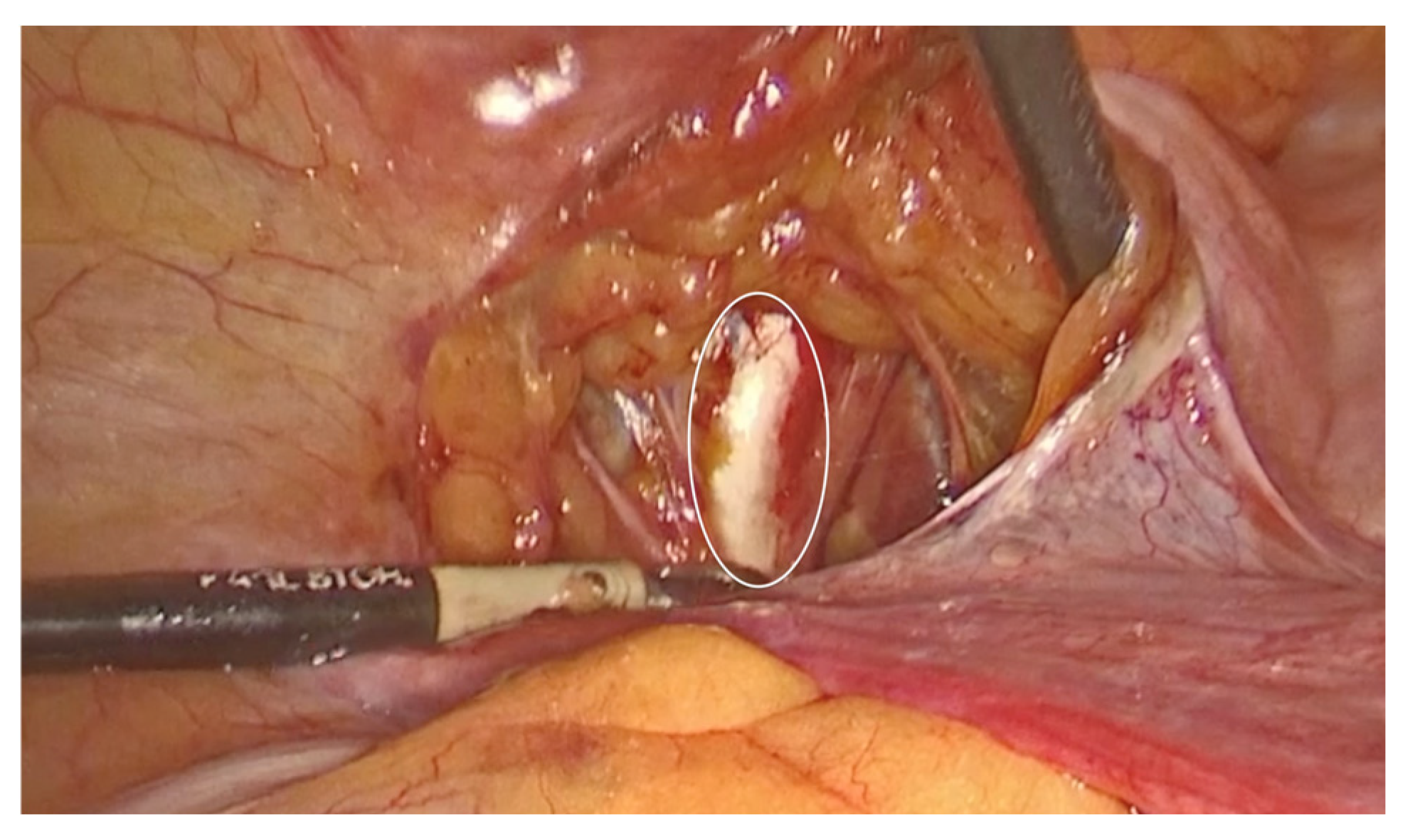

2.2. Technique Description for Laparoscopic Pectopexy with Mesh

2.3. Technique Description for Laparoscopic Pectopexy with Thread

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Cure Rate

4.2. Recurrence Rate

4.3. Mild Asymptomatic Cystocele

4.4. Chronic Pain and Dyspareunia

4.5. Intraoperative Complications

4.6. Risk Factors for Recurrence

4.7. FDA Recommendations on Mesh

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Barber, M.D.; Maher, C. Maher: Epidemiology and outcome assessment of pelvic organ prolapse. Int. Urogynecol. J. 2013, 24, 1783–1790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szymczak, P.; Grzybowska, M.E.; Sawicki, S.; Wydra, D.G. Laparoscopic Pectopexy—CUSUM Learning Curve and Perioperative Complications Analysis. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aboseif, C.; Liu, P. Pelvic Organ Prolapse; StatPearls Publishing: St. Petersburg, FL, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Le, N.B.; Rogo-Gupta, L.; Raz, S. Surgical Options for Apical Prolapse Repair. Women’s Health 2012, 8, 557–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noé, K.G.; Schiermeier, S.; Alkatout, I.; Anapolski, M. Laparoscopic pectopexy: A prospective, randomized, comparative clinical trial of standard laparoscopic sacral colpocervicopexy with the new laparoscopic pectopexy-postoperative results and intermediate-term follow-up in a pilot study. J. Endourol. 2015, 29, 210–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szymczak, P.; Grzybowska, M.E.; Sawicki, S.; Futyma, K.; Wydra, D.G. Perioperative and Long-Term Anatomical and Subjective Outcomes of Laparoscopic Pectopexy and Sacrospinous Ligament Suspension for POP-Q Stages II–IV Apical Prolapse. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 2215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Colombo, M.; Milani, R. Sacrospinous ligament fixation and modified McCall culdoplasty during vaginal hysterectomy for advanced uterovaginal prolapse. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 1998, 179, 13–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Banerjee, C.; Noé, K.G. Laparoscopic pectopexy: A new technique of prolapse surgery for obese patients. Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 2011, 284, 631–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brasoveanu, S.; Ilina, R.; Balulescu, L.; Pirtea, M.; Secosan, C.; Grigoraș, D.; Chiriac, D.; Bardan, R.; Margan, M.M.; Alexandru, A.; et al. Laparoscopic Pectopexy versus Vaginal Sacrospinous Ligament Fixation in the Treatment of Apical Prolapse. Life 2023, 13, 1951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, T.; Du, J.; Geng, J.; Li, L. Meta-analysis of the comparison of laparoscopic pectopexy and laparoscopic sacrocolpopexy in the treatment of pelvic organ prolapse. Int. J. Gynecol. Obstet. 2024, 168, 978–986. [Google Scholar]

- Noé, G.K.; Schiermeier, S.; Papathemelis, T.; Fuellers, U.; Khudyakovd, A.; Altmann, H.H.; Borowski, S.; Morawski, P.P.; Gantert, M.; De Vree, B.; et al. Prospective International Multicenter Pelvic Floor Study: Short-Term Follow-Up and Clinical Findings for Combined Pectopexy and Native Tissue Repair. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Astepe, B.S.; Karsli, A.; Köleli, I.; Aksakal, O.S.; Terzi, H.; Kale, A. Intermediate-term outcomes of laparoscopic pectopexy and vaginal sacrospinous fixation: A comparative study. Int. Braz. J. Urol. 2019, 45, 999–1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG). Management of Mesh and Graft Complications in Gynecologic Surgery; ACOG Committee Opinion: Washington, DC, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Vancaillie, T.; Tan, Y.; Chow, J.; Kite, L.; Howard, L. Pain after vaginal prolapse repair surgery with mesh is a post-surgical neuropathy which needs to be treated–and can possibly be prevented in some cases. Aust. New Zealand J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2018, 58, 696–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, P.; Li, M.; Sun, H. Function, quality-of-life and complications after sacrospinous ligament fixation using an antegrade reusable suturing device (ARSD-Ney) at 6 and 12 months: A retrospective cohort study. Ann. Transl. Med. 2022, 10, 582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Complications and Contraindications for Transvaginal Mesh in Pelvic Organ Prolapse Repair. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. Can. 2017, 39, 1085–1097. [CrossRef]

- Vergeldt, T.F.; Weemhoff, M.; IntHout, J.; Kluivers, K.B. Risk factors for pelvic organ prolapse and its recurrence: A systematic review. Int. Urogynecol. J. 2015, 26, 1559–1573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- U.S Food & Drug. Pelvic Organ Prolapse (POP): Surgical Mesh Considerations and Recommendations; U.S Food & Drug: Silver Spring, MD, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Favre-Inhofer, A.; Carbonnel, M.; Murtada, R.; Revaux, A.; Asmar, J.; Ayoubi, J.-M. Sacrospinous ligament fixation: Medium and long-term anatomical results, functional and quality of life results. BMC Women’s Health 2021, 21, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Age | ||

|---|---|---|

| No Mesh | Mesh | |

| Valid | 42 | 36 |

| Missing | 0 | 0 |

| Mean | 56.167 | 56.444 |

| Std. Deviation | 6.942 | 4.742 |

| Minimum | 42.000 | 45.000 |

| Maximum | 70.000 | 65.000 |

| Mesh | Complete Recidive | Normal | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No Mesh | Count | 0.000 | 42.000 | 42.000 |

| % within row | 0.000% | 100.000% | 100.000% | |

| % within column | 0.000% | 55.263% | 53.846% | |

| Mesh | Count | 2.000 | 34.000 | 36.000 |

| % within row | 5.556% | 94.444% | 100.000% | |

| % within column | 100.000% | 44.737% | 46.154% | |

| Total | Count | 2.000 | 76.000 | 78.000 |

| % within row | 2.564% | 97.436% | 100.000% | |

| % within column | 100.000% | 100.000% | 100.000% |

| Mild Asymptomatic Cystocele | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mesh | No | Yes | Total | |

| No Mesh | Count | 25.000 | 17.000 | 42.000 |

| % within row | 59.524% | 40.476% | 100.000% | |

| % within column | 58.140% | 48.571% | 53.846% | |

| Mesh | Count | 18.000 | 18.000 | 36.000 |

| % within row | 50.000% | 50.000% | 100.000% | |

| % within column | 41.860% | 51.429% | 46.154% | |

| Total | Count | 43.000 | 35.000 | 78.000 |

| % within row | 55.128% | 44.872% | 100.000% | |

| % within column | 100.000% | 100.000% | 100.000% | |

| Chronic Pain/Dispareunia | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mesh | No Pain | Chronic Pain | Total | |

| No Mesh | Count | 42.000 | 0.000 | 42.000 |

| % within row | 100.000% | 0.000% | 100.000% | |

| % within column | 56.757% | 0.000% | 53.846% | |

| Mesh | Count | 32.000 | 4.000 | 36.000 |

| % within row | 88.889% | 11.111% | 100.000% | |

| % within column | 43.243% | 100.000% | 46.154% | |

| Total | Count | 74.000 | 4.000 | 78.000 |

| % within row | 94.872% | 5.128% | 100.000% | |

| % within column | 100.000% | 100.000% | 100.000% | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pirtea, M.; Bălulescu, L.; Pirtea, L.; Brasoveanu, S.; Secosan, C.; Balan, L.; Olaru, F.; Dabica, A.; Margan, M.-M.; Navolan, D. The Effectiveness of Mesh-Less Pectopexy in the Treatment of Vaginal Apical Prolapse—A Prospective Study. Diagnostics 2025, 15, 526. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15050526

Pirtea M, Bălulescu L, Pirtea L, Brasoveanu S, Secosan C, Balan L, Olaru F, Dabica A, Margan M-M, Navolan D. The Effectiveness of Mesh-Less Pectopexy in the Treatment of Vaginal Apical Prolapse—A Prospective Study. Diagnostics. 2025; 15(5):526. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15050526

Chicago/Turabian StylePirtea, Marilena, Ligia Bălulescu, Laurentiu Pirtea, Simona Brasoveanu, Cristina Secosan, Lavinia Balan, Flavius Olaru, Alexandru Dabica, Mădălin-Marius Margan, and Dan Navolan. 2025. "The Effectiveness of Mesh-Less Pectopexy in the Treatment of Vaginal Apical Prolapse—A Prospective Study" Diagnostics 15, no. 5: 526. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15050526

APA StylePirtea, M., Bălulescu, L., Pirtea, L., Brasoveanu, S., Secosan, C., Balan, L., Olaru, F., Dabica, A., Margan, M.-M., & Navolan, D. (2025). The Effectiveness of Mesh-Less Pectopexy in the Treatment of Vaginal Apical Prolapse—A Prospective Study. Diagnostics, 15(5), 526. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15050526