Wing Morphometrics of Aedes Mosquitoes from North-Eastern France

Abstract

:Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Mosquito Collection and Identification

3.2. Error Measurement

3.3. Mean Shapes

3.4. Allometric Regression

3.5. Canonical Variate Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lazzarini, L.; Barzon, L.; Foglia, F.; Manfrin, V.; Pacenti, M.; Pavan, G.; Rassu, M.; Capelli, G.; Montarsi, F.; Martini, S.; et al. First autochthonous dengue outbreak in Italy, August 2020. Eurosurveill. Bull. Eur. Sur Les Mal. Transm. Eur. Commun. Dis. Bull. 2020, 25, 2–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaffner, F.; Mathieu, B. Identifier un moustique: Morphologie classique et nouvelles techniques moléculaires associées pour une taxonomie intégrée. Rev. Francoph. Des. Lab. 2020, 2020, 24–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaffner, E.A.G.; Bernard, G.; Jean-Paul, H.; Rhaiem, A.; Jacques, B. The Mosquitoes of Europe: An Identification and Training Programme; IRD, EID, Eds.; IRD: Paris, France, 2001; ISBN 2-7099-1485-9. [Google Scholar]

- Ung, V.; Dubus, G.; Zaragueta-Bagils, R.; Vignes-Lebbe, R. Xper2: Introducing e-taxonomy. Bioinformatics 2010, 26, 703–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gunay, F.P.M.; Robert, V. MosKeyTool, an Interactive Identification Key for Mosquitoes of Euro-Mediterranean, Version 2.1. 2018. Available online: https://www.medilabsecure.com/moskeytool (accessed on 12 April 2021).

- Hebert, P.D.; Cywinska, A.; Ball, S.L.; de Waard, J.R. Biological identifications through DNA barcodes. Proc. Biol. Sci. 2003, 270, 313–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cywinska, A.; Hunter, F.F.; Hebert, P.D. Identifying Canadian mosquito species through DNA barcodes. Med. Vet. Entomol. 2006, 20, 413–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ratnasingham, S.; Hebert, P.D. BOLD: The Barcode of Life Data System. Mol. Ecol. Notes 2007, 7, 355–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Bahnck, C.M.; Fonseca, D.M. Rapid assay to identify the two genetic forms of Culex (Culex) pipiens L. (Diptera: Culicidae) and hybrid populations. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2006, 75, 251–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Smith, J.L.; Fonseca, D.M. Rapid assays for identification of members of the Culex (Culex) pipiens complex, their hybrids, and other sibling species (Diptera: Culicidae). Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2004, 70, 339–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Higa, Y.T.T.; Tsuda, Y.; Miyagi, I. A multiplex PCR-based molecular identification of five morphologically related, medically important subgenus Stegomyia mosquitoes from the genus Aedes (Diptera: Culicidae) found in the Ryukyu Archipelago, Japan. Jpn. J. Infect. Dis. 2010, 63, 312–316. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Brosseau, L.; Udom, C.; Sukkanon, C.; Chareonviriyaphap, T.; Bangs, M.J.; Saeung, A.; Manguin, S. A multiplex PCR assay for the identification of five species of the Anopheles barbirostris complex in Thailand. Parasites Vectors 2019, 12, 223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bass, C.; Williamson, M.S.; Field, L.M. Development of a multiplex real-time PCR assay for identification of members of the Anopheles gambiae species complex. Acta Trop. 2008, 107, 50–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schenkel, C.D.; Kamber, T.; Schaffner, F.; Mathis, A.; Silaghi, C. Loop-mediated isothermal amplification (LAMP) for the identification of invasive Aedes mosquito species. Med. Vet. Entomol. 2019, 33, 345–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vega-Rua, A.; Pages, N.; Fontaine, A.; Nuccio, C.; Hery, L.; Goindin, D.; Gustave, J.; Almeras, L. Improvement of mosquito identification by MALDI-TOF MS biotyping using protein signatures from two body parts. Parasites Vectors 2018, 11, 574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yssouf, A.; Parola, P.; Lindstrom, A.; Lilja, T.; L’Ambert, G.; Bondesson, U.; Berenger, J.M.; Raoult, D.; Almeras, L. Identification of European mosquito species by MALDI-TOF MS. Parasitol. Res. 2014, 113, 2375–2378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niare, S.; Berenger, J.M.; Dieme, C.; Doumbo, O.; Raoult, D.; Parola, P.; Almeras, L. Identification of blood meal sources in the main African malaria mosquito vector by MALDI-TOF MS. Malar. J. 2016, 15, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Mitteroecker, P.; Gunz, P. Advances in geometric morphometrics. Evol. Biol. 2009, 36, 235–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wilke, A.B.; Christe Rde, O.; Multini, L.C.; Vidal, P.O.; Wilk-da-Silva, R.; de Carvalho, G.C.; Marrelli, M.T. Morphometric wing characters as a tool for mosquito identification. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0161643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, D.C.; Rohlf, F.J.; Slice, D.E. Geometric morphometrics: Ten years of progress following the ‘revolution’. Ital. J. Zool. 2004, 71, 5–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Utkualp, N.; Ercan, I. Anthropometric Measurements Usage in Medical Sciences. Biomed. Res. Int. 2015, 2015, 404261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Van der Niet, T.; Zollikofer, C.P.; Leon, M.S.; Johnson, S.D.; Linder, H.P. Three-dimensional geometric morphometrics for studying floral shape variation. Trends. Plant. Sci. 2010, 15, 423–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gharaibeh, W.S.; Rohlf, F.J.; Slice, D.E.; DeLisi, L.E. A geometric morphometric assessment of change in midline brain structural shape following a first episode of schizophrenia. Biol. Psychiatry 2000, 48, 398–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dujardin, J.-P. Morphometrics applied to medical entomology. Infect. Genet. Evol. J. Mol. Epidemiol. Evol. Genet. Infect. Dis. 2008, 8, 875–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorenz, C.; Marques, T.C.; Sallum, M.A.; Suesdek, L. Altitudinal population structure and microevolution of the malaria vector Anopheles cruzii (Diptera: Culicidae). Parasites Vectors 2014, 7, 581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hidalgo, K.; Dujardin, J.P.; Mouline, K.; Dabire, R.K.; Renault, D.; Simard, F. Seasonal variation in wing size and shape between geographic populations of the malaria vector, Anopheles coluzzii in Burkina Faso (West Africa). Acta Trop. 2015, 143, 79–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaiphongpachara, T.; Juijayen, N.; Chansukh, K.K. Wing geometry analysis of Aedes aegypti (Diptera, Culicidae), a Dengue virus vector, from multiple geographical locations of samut songkhram, Thailand. J. Arthropod. Borne Dis. 2018, 12, 351–360. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Wilk-da-Silva, R.; de Souza Leal Diniz, M.M.C.; Marrelli, M.T.; Wilke, A.B.B. Wing morphometric variability in Aedes aegypti (Diptera: Culicidae) from different urban built environments. Parasites Vectors 2018, 11, 561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phanitchat, T.; Apiwathnasorn, C.; Sungvornyothin, S.; Samung, Y.; Dujardin, S.; Dujardin, J.P.; Sumruayphol, S. Geometric morphometric analysis of the effect of temperature on wing size and shape in Aedes albopictus. Med. Vet. Entomol. 2019, 33, 476–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorenz, C.; Marques, T.C.; Sallum, M.A.; Suesdek, L. Morphometrical diagnosis of the malaria vectors Anopheles cruzii, An. homunculus and An. bellator. Parasites Vectors 2012, 5, 257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Borstler, J.; Luhken, R.; Rudolf, M.; Steinke, S.; Melaun, C.; Becker, S.; Garms, R.; Kruger, A. The use of morphometric wing characters to discriminate female Culex pipiens and Culex torrentium. J. Vector Ecol. J. Soc. Vector Ecol. 2014, 39, 204–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Souza, A.; Multini, L.C.; Marrelli, M.T.; Wilke, A.B.B. Wing geometric morphometrics for identification of mosquito species (Diptera: Culicidae) of neglected epidemiological importance. Acta Trop. 2020, 211, 105593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prudhomme, J.; Cassan, C.; Hide, M.; Toty, C.; Rahola, N.; Vergnes, B.; Dujardin, J.P.; Alten, B.; Sereno, D.; Banuls, A.L. Ecology and morphological variations in wings of Phlebotomus ariasi (Diptera: Psychodidae) in the region of Roquedur (Gard, France): A geometric morphometrics approach. Parasites Vectors 2016, 9, 578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hajd Henni, L.; Sauvage, F.; Ninio, C.; Depaquit, J.; Augot, D. Wing geometry as a tool for discrimination of obsoletus group (Diptera: Ceratopogonidae: Culicoides) in France. Infect. Genet. Evol. J. Mol. Epidemiol. Evol. Genet. Infect. Dis. 2014, 21, 110–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lourenco-de-Oliveira, R.; Mousson, L.; Vazeille, M.; Fuchs, S.; Yebakima, A.; Gustave, J.; Girod, R.; Dusfour, I.; Leparc-Goffart, I.; Vanlandingham, D.L.; et al. Chikungunya virus transmission potential by local Aedes mosquitoes in the Americas and Europe. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2015, 9, e0003780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jupille, H.; Seixas, G.; Mousson, L.; Sousa, C.A.; Failloux, A.B. Zika virus, a new threat for Europe? PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2016, 10, e0004901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Vega-Rua, A.; Zouache, K.; Caro, V.; Diancourt, L.; Delaunay, P.; Grandadam, M.; Failloux, A.B. High efficiency of temperate Aedes albopictus to transmit chikungunya and dengue viruses in the Southeast of France. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e59716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Balenghien, T.; Vazeille, M.; Grandadam, M.; Schaffner, F.; Zeller, H.; Reiter, P.; Sabatier, P.; Fouque, F.; Bicout, D.J. Vector competence of some French Culex and Aedes mosquitoes for West Nile virus. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2008, 8, 589–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinet, J.P.; Ferté, H.; Failloux, A.B.; Schaffner, F.; Depaquit, J. Mosquitoes of north-western europe as potential vectors of arboviruses: A review. Viruses 2019, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Möhrig, W. Die culiciden deutschlands. Untersuchungen zur taxonomie. Biologie und ökologie der einheimischen stechmücken. Int. Rev. Der Gesamten Hydrobiol. Hydrogr. 1970, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorenz, C.; Suesdek, L. Evaluation of chemical preparation on insect wing shape for geometric morphometrics. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2013, 89, 928–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hebert, P.D.; Penton, E.H.; Burns, J.M.; Janzen, D.H.; Hallwachs, W. Ten species in one: DNA barcoding reveals cryptic species in the neotropical skipper butterfly Astraptes fulgerator. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2004, 101, 14812–14817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Altschul, S.F.; Gish, W.; Miller, W.; Myers, E.W.; Lipman, D.J. Basic local alignment search tool. J. Mol. Biol. 1990, 215, 403–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rohlf, F. The tps series of software. Hystrix 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Team R. RStudio: Integrated Development Environment for R; RStudio, Inc.: Boston, MA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Adams, D.C.; Otárola-Castillo, E.; Paradis, E. geomorph: Anrpackage for the collection and analysis of geometric morphometric shape data. Methods Ecol. Evol. 2013, 4(4), 393–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klingenberg, C.P. MorphoJ: An integrated software package for geometric morphometrics. Mol. Ecol. Resour. 2011, 11, 353–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammer, Ø.; Harper, D.A.; Ryan, P.D. PAST: Paleontological statistics software package for education and data analysis. Palaeontol. Electron. 2001, 4, 9. [Google Scholar]

- Rezza, G. Aedes albopictus and the reemergence of Dengue. BMC Public Health 2012, 12, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Schaffner, F.; Vazeille, M.; Kaufmann, C.; Failloux, A.B.; Mathis, A. Vector competence of Aedes japonicus for chikungunya and dengue viruses. J. Eur. Mosq. Control. Assoc. 2011, 29, 141–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veronesi, E.; Paslaru, A.; Silaghi, C.; Tobler, K.; Glavinic, U.; Torgerson, P.; Mathis, A. Experimental evaluation of infection, dissemination, and transmission rates for two West Nile virus strains in European Aedes japonicus under a fluctuating temperature regime. Parasitol. Res. 2018, 117, 1925–1932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Jansen, S.; Heitmann, A.; Lühken, R.; Jöst, H.; Helms, M.; Vapalahti, O.; Schmidt-Chanasit, J.; Tannich, E. Experimental transmission of Zika virus by Aedes japonicus japonicus from southwestern Germany. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 2018, 7, 192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Abbo, S.R.; Visser, T.M.; Wang, H.; Goertz, G.P.; Fros, J.J.; Abma-Henkens, M.H.C.; Geertsema, C.; Vogels, C.B.F.; Koopmans, M.P.G.; Reusken, C.; et al. The invasive Asian bush mosquito Aedes japonicus found in the Netherlands can experimentally transmit Zika virus and Usutu virus. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2020, 14, e0008217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hubalek, Z.; Halouzka, J. West Nile fever-a reemerging mosquito-borne viral disease in Europe. Emerg. Infect. Dis 1999, 5, 643–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sauer, F.G.; Jaworski, L.; Erdbeer, L.; Heitmann, A.; Schmidt-Chanasit, J.; Kiel, E.; Luhken, R. Geometric morphometric wing analysis represents a robust tool to identify female mosquitoes (Diptera: Culicidae) in Germany. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 17613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

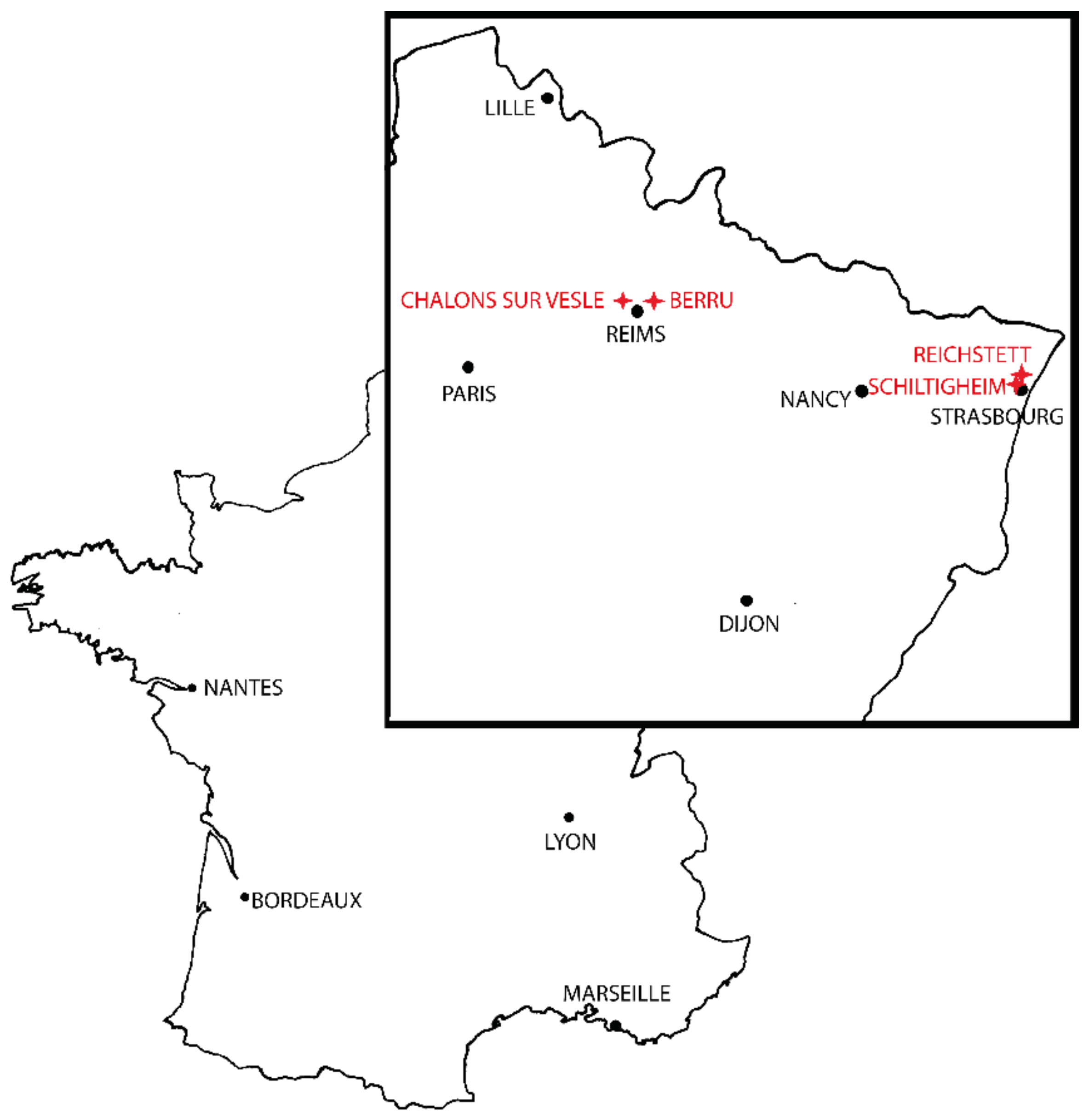

| Species | Collection Date | City | Latitude | Longitude | Number of Specimens |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aedes albopictus | 19 September 2019 | Shiltigheim | 48.603253 | 7.734191 | 31 |

| Aedes cantans | 24 April 2018 | Châlons/Vesle | 49.288187 | 3.924016 | 20 |

| Aedes cinereus | 29 June 2018 | Berru | 49.267750 | 4.133623 | 25 |

| Aedes sticticus | 29 June 2018 | Berru | 49.267750 | 4.133623 | 31 |

| Aedes japonicus | 1 October 2019 | Reichstett | 48.648827 | 7.757608 | 8 |

| Aedes rusticus | 23 May 2018 | Berru | 49.267750 | 4.133623 | 33 |

| Reclassification Test | Group 2 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aedes albopictus | Aedes cantans | Aedes cinereus | Aedes sticticus | Aedes japonicus | Aedes rusticus | ||

| Group 1 | Aedes albopictus | × | 100% | 100% | 100% | 75% | 100% |

| Aedes cantans | 97% | × | 100% | 94% | 100% | 100% | |

| Aedes cinereus | 100% | 95% | × | 100% | 100% | 100% | |

| Aedes sticticus | 97% | 100% | 100% | × | 100% | 100% | |

| Aedes japonicus | 90% | 100% | 96% | 100% | × | 100% | |

| Aedes rusticus | 100% | 100% | 100% | 97% | 100% | × | |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Martinet, J.-P.; Ferté, H.; Sientzoff, P.; Krupa, E.; Mathieu, B.; Depaquit, J. Wing Morphometrics of Aedes Mosquitoes from North-Eastern France. Insects 2021, 12, 341. https://doi.org/10.3390/insects12040341

Martinet J-P, Ferté H, Sientzoff P, Krupa E, Mathieu B, Depaquit J. Wing Morphometrics of Aedes Mosquitoes from North-Eastern France. Insects. 2021; 12(4):341. https://doi.org/10.3390/insects12040341

Chicago/Turabian StyleMartinet, Jean-Philippe, Hubert Ferté, Pacôme Sientzoff, Eva Krupa, Bruno Mathieu, and Jérôme Depaquit. 2021. "Wing Morphometrics of Aedes Mosquitoes from North-Eastern France" Insects 12, no. 4: 341. https://doi.org/10.3390/insects12040341