The First Study of Mating Mistakes in Stoneflies (Plecoptera) from China, with Remarks on Their Biological Implications

Abstract

:Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Mating Attempts between Conspecific Males

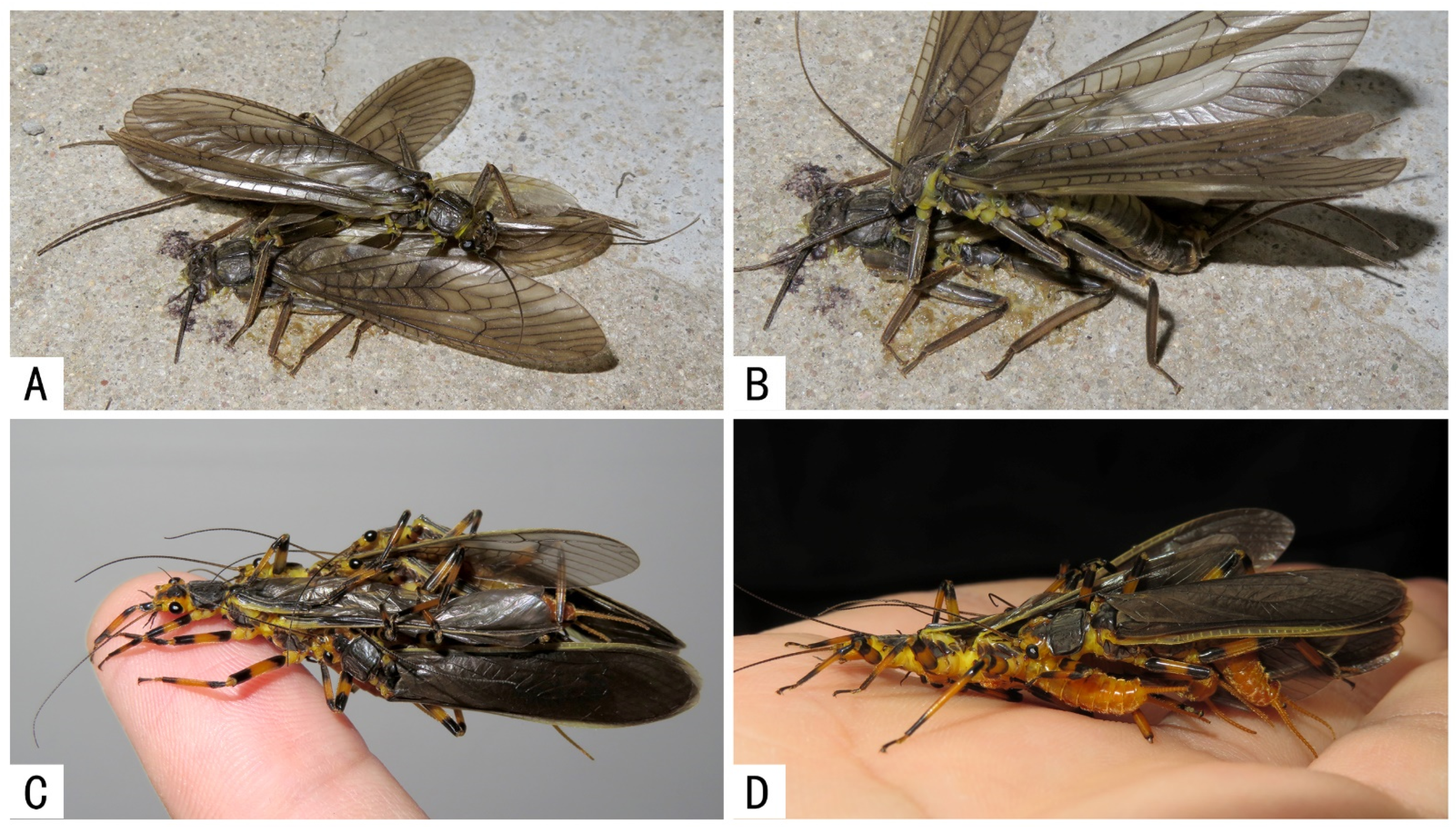

3.2. Mating Attempts between Different Taxa

3.3. Mating-Related Behaviors with Non-Living Objects

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- de Figueroa, J.M.T.; Luzón-Ortega, J.M.; López-Rodríguez, M.J. Drumming for Love: Mating Behavior in Stoneflies. In Aquatic Insects; Del-Claro, K., Guillermo, R., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 117–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rupprecht, R. Das trommeln der Plecopteren. Z. Für Vgl. Physiol. 1968, 59, 38–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, K.W. Vibrational communication in insects. Epitome in the language of stoneflies? Am. Entomol. 1997, 43, 81–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, K.W. Vibrational communication (drumming) and mate-searching behavior of stoneflies (Plecoptera); evolutionary considerations. In Trends in Research in Ephemeroptera and Plecoptera; Domínguez, E., Ed.; Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publisher: New York, NY, USA, 2001; pp. 217–225. [Google Scholar]

- Alexander, K.D.; Stewart, K.W. Description and theoretical considerations of mate finding and other adult behaviors in a Colorado population of Claasenia sabulosa (Plecoptera: Perlidae). Ann. Entomol. Soc. Am. 1996, 89, 290–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, K.W. Theoretical considerations of mate finding and other adult behaviors of Plecoptera. Aquatic Insects 1994, 16, 95–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rebora, M.; Tierno de Figueroa, J.M.; Piersanti, S. Antennal sensilla of the stonefly Dinocras cephalotes (Plecoptera: Perlidae). Arthropod Struct. Dev. 2016, 45, 552–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brinck, P. Studies on Swedish stoneflies. Opusc. Entomol. 1949, 11, 1–250. [Google Scholar]

- Khoo, S.G. Studies on the Biology of the Stoneflies. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Liverpool, Liverpool, UK, 1964; pp. 1–161. [Google Scholar]

- Zeigler, D.D. Observations pertinent to the role of sexual selection in the stonefly Pteronarcella badia (Plecoptera: Pter-onarcyidae). Entomol. News 1990, 101, 283–287. [Google Scholar]

- Tierno de Figueroa, J.M. Biología Imaginal de los Plecópteros (Insecta, Plecoptera) de Sierra Nevada (Granada, España). Ph.D. Thesis, University of Granada, Granada, Spain, 1998; pp. 1–312. [Google Scholar]

- Boumans, L.; Tierno de Figueroa, J.M. Introgression and species demarcation in western European Leuctra fusca and L. digitata (Plecoptera, Leuctridae). Aquatic Insects 2016, 37, 115–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.F. The stoneflies of China (Order Plecoptera). Bull. Peking Soc. Nat. Hist. 1938, 13, 53–87. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, C.F. Results of the Zoologico-Botanical expedition to Southwest China, 1955–1957 (Plecoptera). Acta Entomol. Sin. 1962, 12, 139–153. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, C.F. New species of Chinese stoneflies (order Plecoptera). Acta Entomol. Sin. 1973, 16, 97–118. [Google Scholar]

- Du, Y.Z. A taxonomic study on Plecoptera from China. Ph.D. Thesis, Zhejiang University, Hangzhou, China, 1999; pp. 1–324, Unpublished. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, D.; Li, W.H.; Zhu, F. Fauna Sinica Insecta. Plecoptera Nemouroidea; Science Press: Beijing, China, 2015; Volume 58, pp. 1–503. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, D.; Li, W.H. Species Catalogue of China. Vols. 2 Animals, Insecta (III), Plecoptera; Science Press: Beijing, China, 2018; pp. 1–71. [Google Scholar]

- Li, W.H.; Murányi, D.; Kirill, M.O.; Uchida, S.; Wang, R.F. A new species of Sinacroneuria (Plecoptera: Perlidae) from Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region, southcentral China based on male adult, larva and drumming signals, and validation of the Japanese species of the genus. Zootaxa 2017, 4299, 95–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gwynne, D.T. Mating Behaviors. In Encyclopedia of Insects; Resh, V.H., Cardé, R.T., Eds.; Academic Press: Burlington, MA, USA, 2009; pp. 604–609. [Google Scholar]

- Alexander, R.D.; Marshall, D.C.; Cooley, J.R. Evolutionary perspectives on insect mating. In The Evolution of Mating Systems in Insects and Arachnids; Choe, J.C., Crespi, B.J., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1997; pp. 4–31. [Google Scholar]

- Thornhill, R.; Alcock, J. In The Evolution of Insect Mating Systems; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA; London, UK, 1983; pp. 1–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gröning, J.; Hochkirch, A. Reproductive interference between animal species. Q. Rev. Biol. 2008, 83, 257–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tierno de Figueroa, J.M.; Luzón-Ortega, J.M.; López-Rodríguez, M.J. Mating balls in stoneflies (Insecta, Plecoptera). Zoo-Log. Baetica 2006, 17, 93–96. [Google Scholar]

- Shine, R.; Olsson, M.M.; Moore, I.T.; Lemaster, M.P.; Greene, M.; Mason, R.T. Body size enhances mating success in male garter snakes. Anim. Behav. 2000, 59, F4–F11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tierno de Figueroa, J.M. Mate guarding and displacement attempts in stoneflies (Insecta, Plecoptera). Biologia 2003, 58, 925–928. [Google Scholar]

- Emlen, D.J. Reproductive contests and the evolution of extreme weaponry. In The Evolution of Insects Mating Systems; Shuker, D.M., Simmons, L.W., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2014; pp. 92–105. [Google Scholar]

- Newell, R.L.; Baumann, R.W. Stonefly sex gone awry: An attempted mating by a Perlinodes aureus (Smith) male with a Pteronarcys californica Newport male. Illiesia 2012, 8, 152–157. [Google Scholar]

- Rebora, M.; Piersanti, S.; Frati, F.; Salerno, G. Antennal responses to volatile organic compounds in a stonefly. J. Insect Physiol. 2017, 98, 231–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orci, K.M.; Murányi, D. Female answer specificity to male drumming calls in three closely related species of the stonefly genus Zwicknia (Plecoptera: Capniidae). Insect Sci. 2020, 28, 215–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanson, J.F. A case of hybridization in Plecoptera. Bull. Brooklyn Entomol. Soc. 1960, 55, 25–34. [Google Scholar]

- Young, M.K.; Smith, R.J.; Pilgrim, K.L.; Fairchild, M.P.; Schwartz, M.K. Integrative taxonomy refutes a species hypothesis: The asymmetric hybrid origin of Arsapnia arapahoe (Plecoptera, Capniidae). Ecol. Evol. 2019, 9, 1364–1377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Abbott, R.; Albach, D.; Ansell, S.; Arntzen, J.W.; Baird, S.J.; Bierne, N.; Boughman, J.; Brelsford, A.; Buerkle, C.A.; Buggs, R.; et al. Hybridization and speciation. J. Evol. Biol. 2013, 26, 229–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Huo, Q.B.; Chen, Z.N.; Kong, X.B.; Du, Y.Z. New records and a confirmation of three perlodid species in China, with additional notes and images of Rauserodes epiproctalis (Zwick, 1997) (Plecoptera: Perlodidae). Zootaxa 2020, 4808, 455–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huo, Q.B.; Du, Y.Z.; Zhu, B.Q.; Yu, L. Notes on Neoperla sinensis Chu, 1928 and Neoperla anjiensis Yang & Yang, 1998, with descriptions of new species of Neoperla from China (Plecoptera: Perlidae). Zootaxa 2021, 5004, 288–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huo, Q.B.; Du, Y.Z.; Zwick, P.; Murányi, D. Notes on Perlodinella Klapálek, 1912 (Plecoptera: Perlodidae) with a new species and a new synonym. Zootaxa 2022, 5162, 378–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.T.; Jiang, C.; Li, Y.S.Y. DNA barcodes of Plecoptera from China: The preliminary dataset and its performance in species delimitation. Zootaxa 2020, 4751, 345–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinojosa, J.C.; Dapporto, L.; Pitteloud, C.; Koubínová, D.; Hernández-Roldán, J.; Vicente, J.C.; Alvarez, N.; Vila, R. Hy-bridization fuelled diversification in Spialia butterflies. Mol. Ecol. 2022, 31, 2951–2967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, S.A.; Larson, E.L. Insights from genomes into the evolutionary importance and prevalence of hybridization in nature. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 2019, 3, 170–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larson, E.L.; Tinghitella, R.M.; Taylor, S.A. Insect hybridization and climate change. Front. Ecol. Evol. 2019, 7, 348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ottenburghs, J. The genic view of hybridization in the Anthropocene. Evol. Appl. 2021, 14, 2342–2360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valdés, L.R.A.; Guillén, R.A.S. The evolutionary outcomes of climate change-induced hybridization in insect populations. Curr. Opin. Insect Sci. 2022, 54, 100966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Individual Attempting to Mate | Individual Targeted by Mating Attempts | Observation Data |

|---|---|---|

| Claassenia magna ♂ | Claassenia magna ♂ | Fujian: Wuyishan, 2021-V |

| Claassenia sp. ♂ | Claassenia sp. ♂ (alive/dead) | Shaanxi: Xi’an, 2021-V |

| Perlodinella epiproctalis ♂ | Perlodinella epiproctalis ♂ | Qinghai: Menyuan, 2021-VII |

| Togoperla tricolor ♂ | Togoperla tricolor ♂ | Fujian: Wuyishan, 2021-V |

| Individual Attempting to Mate | Individual Targeted by Mating Attempts | Observation Data |

|---|---|---|

| Flavoperla biocellata ♂ | Kiotina sp. ♀ | Fujian: Wuyishan, 2021-V |

| Kamimuria sp. ♂ | Claassenia sp. ♂ | Shaanxi: Xi’an, 2021-V |

| Neoperla sinensis ♂ | Hemacroneuria violacea ♂♀ | Fujian: Wuyishan, 2021-IV |

| Neoperla sinensis ♂ | Kamimuria tienmushanensis ♂ | Fujian: Wuyishan, 2021-IV |

| Neoperla sinensis ♂ | Styloperla inae ♂ | Fujian: Wuyishan, 2021-V |

| Togoperla perpicta ♂ | Togoperla totanigra ♀ | Anhui: Huangshan, 2020-IV |

| Individual Performing Mating-Related Behaviors | Non-Living Objects | Observation Data |

|---|---|---|

| Claassenia magna ♂ | Tissue paper | Fujian: Wuyishan, 2021-V |

| Claassenia sp. ♂ | Tissue paper | Shaanxi: Xi’an, 2021-V |

| Perlodinella epiproctalis ♂ | Tissue paper; bottle | Qinghai: Menyuan, 2021-VII |

| Togoperla tricolor ♂ | Tissue paper | Fujian: Wuyishan, 2021-V |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Huo, Q.-B.; Zhu, B.-Q.; Murányi, D.; Tierno de Figueroa, J.M.; Zhao, M.-Y.; Xiang, Y.-N.; Yang, Y.-B.; Du, Y.-Z. The First Study of Mating Mistakes in Stoneflies (Plecoptera) from China, with Remarks on Their Biological Implications. Insects 2022, 13, 1102. https://doi.org/10.3390/insects13121102

Huo Q-B, Zhu B-Q, Murányi D, Tierno de Figueroa JM, Zhao M-Y, Xiang Y-N, Yang Y-B, Du Y-Z. The First Study of Mating Mistakes in Stoneflies (Plecoptera) from China, with Remarks on Their Biological Implications. Insects. 2022; 13(12):1102. https://doi.org/10.3390/insects13121102

Chicago/Turabian StyleHuo, Qing-Bo, Bin-Qing Zhu, Dávid Murányi, José Manuel Tierno de Figueroa, Meng-Yuan Zhao, Ya-Nan Xiang, Yu-Ben Yang, and Yu-Zhou Du. 2022. "The First Study of Mating Mistakes in Stoneflies (Plecoptera) from China, with Remarks on Their Biological Implications" Insects 13, no. 12: 1102. https://doi.org/10.3390/insects13121102