Paralympics and Its Athletes Through the Lens of the New York Times

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Method

3. Results and Discussion

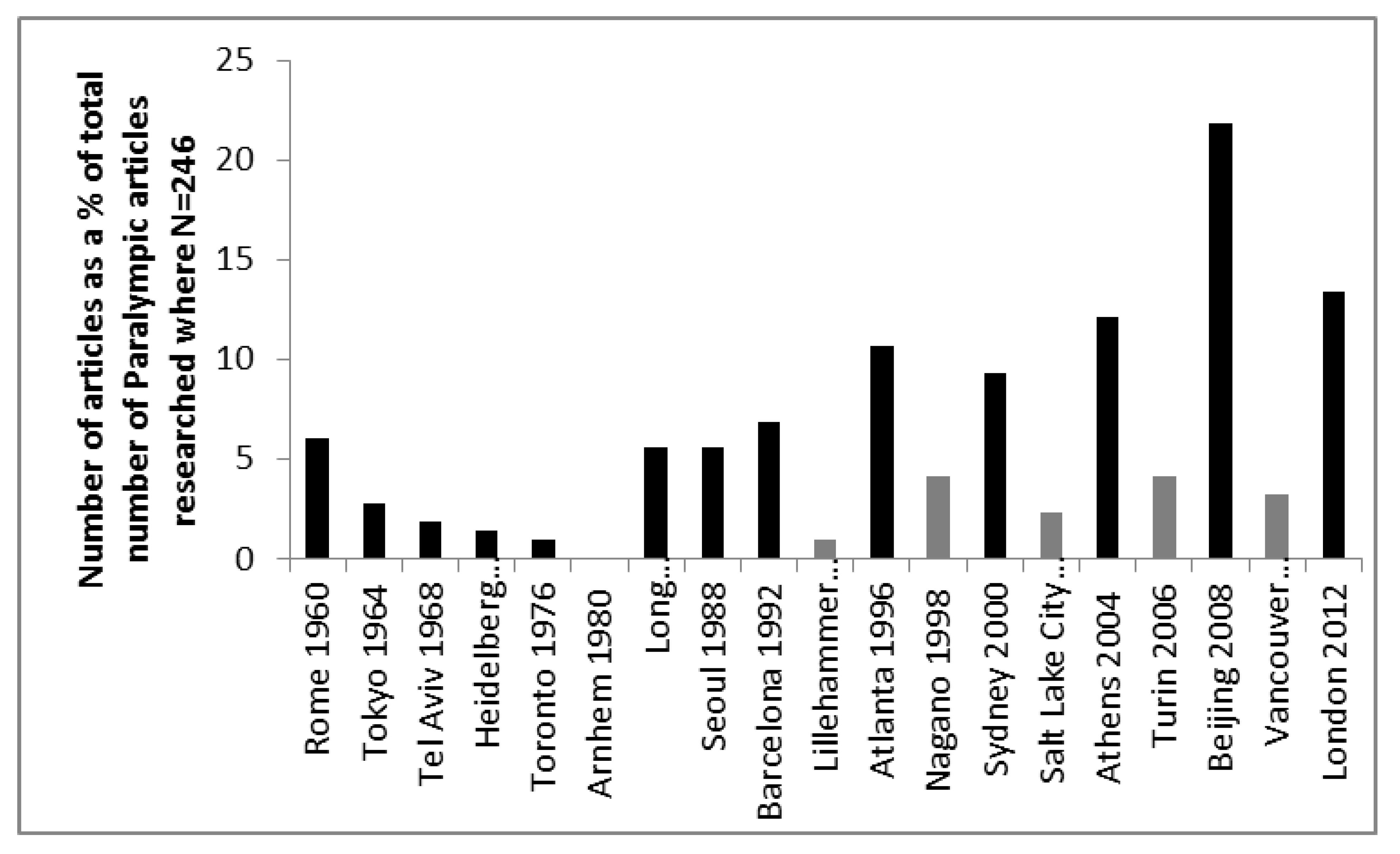

3.1. Visibility of the Paralympics versus the Olympics

| Event | 1955-1987 | 1988-2007 | 2008-2012 | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of articles covering the Paralympics | 49 | 115 | 82 | 246 |

| Number of articles covering the Olympics | 1,296 | 7,100 | 2,091 | 10,487 |

3.2. Visibility of Different Paralympic Sport Disciplines

| Sport | Number of Articles |

|---|---|

| Basketball | 70 |

| Athletics | 53 |

| Skiing | 48 |

| Table tennis | 30 |

| Archery | 24 |

| Shot put | 23 |

| Discus | 22 |

| Javelin | 20 |

| Cycling | 19 |

| Tennis | 16 |

| Soccer | 13 |

| Rugby | 11 |

| Weight lifting | 11 |

| Swimming | 11 |

| Slalom | 9 |

| Shooting | 8 |

| Fencing | 7 |

| Yachting | 6 |

| Volleyball | 6 |

| Sledge hockey | 5 |

| Sailing | 5 |

| Pentathlon | 4 |

| Darts | 3 |

| Tandem cycling | 3 |

| Triathlon | 3 |

| Equestrian | 3 |

| Snooker | 2 |

| Club throwing | 2 |

| Heptathlon | 2 |

| Darchery | 2 |

| Judo | 2 |

| Ping-pong | 1 |

| Bowling | 1 |

3.2. Visibility of Paralympians

| Paralympian | Number of articles |

|---|---|

| *Oscar Pistorius | 32 |

| *Natalie du Toit | 10 |

| *Marla Runyan | 7 |

| Jessica Long | 7 |

| Marlon Shirley | 6 |

| Dennis Oehler | 6 |

| Erin Popovich | 5 |

| *Neroli Fairhall | 4 |

| Kortney Clemons | 4 |

| Aimee Mullins | 4 |

| Alonzo Wilkins | 3 |

| Brian McKeever | 3 |

| *Natalya Partyka | 3 |

| Nick Scandone | 3 |

| Alan Oliveira | 3 |

| Melissa Stockwell | 3 |

| Chris Waddell | 3 |

| Bill Demby | 3 |

| Helene Hines | 3 |

| Tony Iniguez | 3 |

| *George Eyser | 2 |

| Mark Zupan | 2 |

| Scott Hogsett | 2 |

| Andy Cohn | 2 |

| Jeff Skiba | 2 |

| *Todd Schaffhauser | 2 |

| John Register | 2 |

| Casey Martin | 2 |

| David Weir | 2 |

| Jerome Singleton | 2 |

| Brian Frasure | 2 |

| Korie Homan | 2 |

| Esther Vergreer | 2 |

| Sharon Walraven | 2 |

| Jiske Griffioen | 2 |

| Paul Schulte | 2 |

| Jerrod Fields | 2 |

| Amy Palmiero-Winters | 2 |

| Damian Lopez Alfonzo | 2 |

| Jackie Joyner-Kersee | 2 |

| Jim Bob Bizzell | 2 |

3.4. Visibility of Disabilities

| Number of Articles | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Disability | 1955-1987 | 1988-2007 | 2008-2012 | Total |

| amput* | 2 | 27 | 30 | 59 |

| paralyz* | 10 | 13 | 7 | 30 |

| blind | 1 | 13 | 8 | 22 |

| parapleg* | 7 | 8 | 4 | 19 |

| polio | 6 | 5 | 3 | 14 |

| cerebral palsy | - | 5 | 3 | 8 |

| spinal cord injur* | - | 4 | 2 | 6 |

| deaf | - | 4 | 1 | 5 |

| Stargardt’s | - | 2 | 3 | 5 |

| visual*/vision impair* | - | 1 | 4 | 5 |

| intellectual* disab* | - | 2 | 3 | 5 |

| paralys* | 1 | - | 4 | 5 |

| quadrapleg*/quadripleg* | - | 4 | - | 4 |

| (develop)mental* disab* | - | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| autism | - | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| hearing impair* | 1 | - | 1 | 2 |

| dwarfism | - | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| multiple sclerosis | - | - | 2 | 2 |

3.5. Portrayal of the Paralympics and Paralympic Games

3.6. Portrayal of Paralympians.

| Number of Terms | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Term | 1955-1987 | 1988-2007 | 2008-2012 | Total |

| injur* | 2 | 12 | 30 | 44 |

| handicap | 14 | 18 | 8 | 40 |

| limit* | 2 | 11 | 16 | 29 |

| disease | 2 | 5 | 20 | 27 |

| impair* | 2 | 11 | 9 | 22 |

| severe | - | 6 | 7 | 13 |

| (ab)normal | - | 5 | 6 | 11 |

| victim | 5 | 5 | - | 10 |

| health* | 2 | 5 | 3 | 10 |

| defect | - | 3 | 6 | 9 |

| bound | 1 | 3 | 5 | 9 |

| cripple* | 6 | 3 | - | 9 |

| participant | 2 | 4 | 2 | 8 |

| confine* | 3 | 3 | - | 6 |

| unusual | 2 | 2 | 2 | 6 |

| charit* | - | 6 | - | 6 |

| affect* | 1 | 1 | 4 | 6 |

| ill* | 1 | 3 | 1 | 5 |

| devastat* | - | 1 | 4 | 5 |

| trauma | - | 3 | 1 | 4 |

| disadvant* | - | 2 | 2 | 4 |

| afflict* | - | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| (physically)challenged | 1 | - | 2 | 3 |

| disadvantage* | - | 2 | 1 | 3 |

| hardship | 1 | - | 1 | 2 |

| Number of Terms | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Term | 1955-1987 | 1988-2007 | 2008-2012 | Total |

| able-bod* | 3 | 27 | 46 | 76 |

| victor* | 20 | 20 | 8 | 48 |

| beat | 2 | 31 | 9 | 42 |

| defeat* | 4 | 20 | 11 | 35 |

| special | 3 | 14 | 10 | 27 |

| achievement | - | 8 | 8 | 16 |

| inspir* | - | 7 | 9 | 16 |

| courag* | 2 | 7 | 3 | 12 |

| hero* | 2 | 5 | 6 | 13 |

| extraordinary | 1 | 4 | 6 | 11 |

| amaz* | 2 | 3 | 6 | 11 |

| overcome/overcame | 1 | 3 | 2 | 6 |

| pure/purity | - | 1 | 5 | 6 |

| warrior | - | 2 | 3 | 5 |

| brav* | - | 2 | 1 | 3 |

| freedom | - | - | 3 | 3 |

| conquer* | 1 | - | 1 | 2 |

3.7. Vision and Hopes of Paralympians

3.8. Portrayal of Assistive Devices

4. Conclusion

Acknowledgments

References and Notes

- Canadian Parks and Recreation Association (CPRA) Benefits of Parks and Recreation Home Page. 1997. Available online: http://www.cpra.ca/main.php?action=cms.initBeneParksRec (accessed on 23 September 2012).

- International ParalympicCommittee (IPC) and Rehabilitation International (RI). Disability Right Toolkit, International Paralympic Committee (IPC) and Rehabilitation International (RI), 2008.

- European Parliament, Situation of disabled people in the enlarged European Union: the European Action Plan 2006–2007. INI/2006/2105. 2006.

- Lundberg, N.R.; Groff, D.G.; Zabriskie, R.B. Psychological Need Satisfaction through Sports Participation among International Athletes with Cerebral Palsy. Annals of Leisure Research 2010, 13, 102–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, E.; Jones, G. Psychological well–being in wheelchair sport participants and nonparticipants. APAQ 1994, 11, 404–415. [Google Scholar]

- Vliet, P.V.; Biesen, D.V.; Vanlandewijck, Y.C. Athletic identity and self–esteem in Flemish athletes with a disability. European Journal of Adapted Physical Activity 2011, 1, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira, J.P.; Fox, K.R. Self–perceptions and exercise in groups with special needs. In Physical Activity and promotion of Mental Health; Ferreira J., P., Gaspar, C., Fontes Ribeiro , A.M., Senra, C., Eds.; Portugal: Faculdade de Ciências do Desporto e Educação Física – Universidade de Coimbra, Coimbra, 2004; pp. 33–40. [Google Scholar]

- Kew, F. Sport: Social problems and issues; Butterworth, Heinemann: Oxford, UK, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Brittain, I. Perception of disability and their impact upon involvement in sports for people with disabilities at all levels. Journal of Sports & Social Issues 2004, 28, 429–452. [Google Scholar]

- Morris, J. Former swimmer hopes to bring athlete's view to job as Paralympic assistant chef; Former Paralympic swimmer named assistant chef. The Canadian Press, Toronto 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Hannon, F. Promoting the Participation of People with Disabilities in Physical Activity and Sport in Ireland. National Disability Authority, Ireland. 2005. Available online: http://www.nda.ie/cntmgmtnew.nsf/0/7020D28F7F65773A802570F30057F05E/$File/Promoting_Participation_Sport.pdf (accessed on 23 September 2012).

- Lakowski, T.; Long, T. Proceedings: Physical Activity and Sport for People with Disabilities. Washington, DC: Georgetown University Center for Child and Human Development Home Page. Available online: http://www.gucchdgeorgetown.net/ucedd/documents/athletic_equity/Physical_Activity_Proceedings.pdf (accessed on 23 September 2012).

- International Paralympic Committee (IPC) Vision, Mission & Values. International Paralympic Committee (IPC) Home Page. Available online: http://www.paralympic.org/IPC/Vision_Mission_Values.html (accessed on 23 September 2012).

- Nord, D.P. A Republican Literature: A Study of Magazine Reading and Readers in Late Eighteenth–Century New York. American Quarterly 1988, 40, 42–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiner, B.I. The Americanization and Periodical Publication, 1750–1810. Cercles 2009, 19, 102–113. [Google Scholar]

- Weinstock Netanel, N. Copyright and a Democratic Civil Society. Yale Law Journal 1996, 106, 292–392. [Google Scholar]

- Wallack, L. Mass media and health promotion: Promise, problem and challenge. In Mass communication and public health: Complexities and conflicts; Atkins, C., Wallack, L., Eds.; Sage: Newbury Park, CA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Burns, A.S. Banks: Restricted reading, rehabilitation and prisoners' first amendment rights. Journal of Law and Policy 2007, 15, 1225–1270. [Google Scholar]

- Kellner, D. Media culture: Cultural studies, identity and politics between the modern and the postmodern; Psychology Press: London, UK, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Noelle–Neumann, E. Wirkung der Massenmedien auf die Meinungsbildung. Fischer Lexikon Publizistik Massenkommunikation 1994, 5, 518–570. [Google Scholar]

- Schantz, O.J.; Gilbert, K. An ideal misconstrued: newspaper coverage of the Atlanta Paralympic Games in France and Germany. Sociology of Sport Journal 2001, 18, 69–94. [Google Scholar]

- Brisenden, S. Independent Living and the Medical Model of Disability. Disability & Society 1986, 1, 173–178. [Google Scholar]

- Learned, W.S. The American Public Library And The Diffusion Of Knowledge; Carnegie Foundation: New York, 1924. [Google Scholar]

- Lazarsfeld, P.F.; Merton, R.K. Mass communication, popular taste and organized social action. Media Studies: A Reader, 2nd edn. (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1999) 1971, 18–30. [Google Scholar]

- Duffy, J.; Yeargeau, M. Editors' Introduction. Disability Studies Quarterly 2011, 31, 3. [Google Scholar]

- Barnes, C. Disabling imagery and the media: An exploration of the principles for media representations of disabled people; BCODP: London, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Goggin, G.; Newell, C. Crippling paralympics?: Media, disability and olympism. Media International Australia, Incorporating Culture & Policy 2000, 97, 71. [Google Scholar]

- Myers Hardin, M.; Hardin, B. The 'Supercrip' in sport media: Wheelchair athletes discuss hegemony's disabled hero. Sociology of Sport Online 2004, 7, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Howe, P.D. From Inside the Newsroom. International Review for the Sociology of Sport 2008, 43, 135–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howe, P.D. Cyborg and Supercrip: The Paralympics Technology and the (Dis) empowerment of Disabled Athletes. Sociology 2011, 45, 868–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacDonald, M. 6 Media and the Paralympic Games. The Paralympic Games: Empowerment Or Side Show? 2009, 1, 68. [Google Scholar]

- Stein, J.U. US media where were you during the 1988 Paralympics? Palaestra, Summer 1989, 45–52. [Google Scholar]

- Darcy, S. The politics of disability and access: the Sydney 2000 Games experience. Disability & Society 2003, 18, 737–757. [Google Scholar]

- Fay, T.; Burton, R.; Grevemberg, D. A marketing analysis of the 2000 Paralympic Games: are the components in place to build an emerging global brand? CSSS Staff Presentations. Paper 2 Home Page. Available online: http://iris.lib.neu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1001&context=sport_staff_pres (accessed on 23 September 2012).

- Wickman, K. Bending mainstream definitions of sport, gender and ability: Representations of wheelchair racers. (doctoral dissertation), Department of Education, Umeå University, Sweden Home Page. Available online: http://umu.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:141458/FULLTEXT01 (accessed on 23 September 2012).

- Golden, A. An analysis of the dissimilar coverage of the 2002 Olympics and Paralympics: Frenzied pack journalism versus the empty press room. Disability Studies Quarterly 2003, 23, 3–4. [Google Scholar]

- Ellis, K. Beyond the Aww Factor: Human interest Profiles of Paralympians and the media navigation of physical difference and social stigma. Asia Pacific Media Educator 2008, 19, 23. [Google Scholar]

- The New York Times Company About the Company: Pulitzer Prizes. New York Times Company Home Page. Available online: http://www.nytco.com/company/awards/pulitzer_prizes.html (accessed on 23 September 2012).

- Althaus, S.L.; Tewksbury, D. Agenda setting and the Ç£new ÇØ news patterns of issue importance among readers of the paper and online versions of the New York Times. Communication Research 2002, 29, 180–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iyengar, S.; Kinder, D.R. News that matters: Television and American opinion; University of Chicago Press, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- The, A.P. Without a Physical Director. New York Times(1923–Current file) 1894, 3. [Google Scholar]

- Associated Press British Olympic Plans Are Delayed for Lack of Funds. New York Times 1920, 14.

- Rusk, H. Sports Competition a Boon To Health of Handicapped. New York Times 1952, 47. [Google Scholar]

- 11 Fly to Paralympics. New York Times (1923-Current file) 1955, 36.

- Smothers, R. Welcoming the Disabled, Atlanta Lets the Games Begin, Again. New York Times 1996, 25. [Google Scholar]

- Ridgley, G. The media and the Paralympics Home Page. Available online: http://www.bl.uk/sportandsociety/exploresocsci/sportsoc/media/articles/paramedia.html (accessed on 23 September 2012).

- Peers, D. (Dis) empowering Paralympic histories: absent athletes and disabling discourses. Disability & Society 2009, 24, 653–665. [Google Scholar]

- Wolbring, G. Oscar Pistorius and the Future Nature of Olympic, Paralympic and Other Sports. SCRIPTed – A Journal of Law, Technology & Society 2008, 5, 139–160. [Google Scholar]

- The, A.P. Pistorius Sprints to Gold in First of His Three Races. New York Times 2008, D6. [Google Scholar]

- Vecsey, G. Strides, Often Painful,, but Always, Always Forward. New York Times 2010, D5. [Google Scholar]

- Schwarz, A. A Severely Injured Soldier Re-emerges as a Sprinter. New York Times 2009, B9. [Google Scholar]

- The, A.P. Pistorius Upset in 200 Meters. New York Times 2012, D4. [Google Scholar]

- Sarah, M.N. Paralympians' Equipment Raises Debate on Fairness. New York Times 2012, SP8. [Google Scholar]

- Longman, J. Embracing the Equality of Opportunity. New York Times 2008, D1. [Google Scholar]

- The, A.P. China Back On Global Sports Stage. New York Times 2008, SP12. [Google Scholar]

- The, A.P. After Olympic Disappointment, Gold at Paralympics. New York Times 2008, D6. [Google Scholar]

- The, A.P. South African Swimmer Wins Her Fourth Gold Medal. New York Times 2008, D6. [Google Scholar]

- Longman, J. Debate on Amputee Sprinter: Is He Disabled or Too-Abled? New York Times 2007, A1. [Google Scholar]

- Longman, J. It's all in the timing. New York Times 1995, B8. [Google Scholar]

- Vecsey, G. The Amateur Ideal: Voters Know a Star When They See One. New York Times 2007, H3. [Google Scholar]

- Dajani, K. Other Research--What's in a Name? Terms Used to Refer to People With Disabilities. Disability Studies Quarterly 2001, 21, 3. [Google Scholar]

- The, A.P. Paralympic Group Orders Suspensions. New York Times 2001, D7. [Google Scholar]

- Special to The New York Times Money Troubles Eased in Wheelchair Games. New York Times (1923-Current file) 1984, 1.

- By The New York Times Safety of the Summer Games Still Worrying Organizers. New York Times (1923-Current file) 1996, 29.

- Schwarz, A. Court lets ruling stand in U.S.O.C. case; [Sports desk]. New York Times 2008, B20. [Google Scholar]

- Vecsey, G. Still Living on the Line. New York Times (1923-Current file) 1988, D19. [Google Scholar]

- Schwirtz, M. Disabled Athletes Defy an Unaccommodating City. New York Times 2010, A10. [Google Scholar]

- Lyall, S. At Paralympics, First Thing Judged Is Disability. New York Times 2012, A1. [Google Scholar]

- Schwarz, A. A Disabled Swimmer's Dream, a Mother's Fight. New York Times 2008, A1. [Google Scholar]

- Museler, C. Nick Scandone, 42, Winner Of Paralympics Sailing Gold. New York Times 2009, B7. [Google Scholar]

- Frosch, D. Warriors Forever. New York Times 2011, SP4. [Google Scholar]

- Schwarz, A. The Art and Science of Wheelchair Basketball. New York Times 2008, SP5. [Google Scholar]

- International Paralympic Committee IPC classification code and international standard. International Paralympic Committee Home Page. Available online: http://www.paralympic.org/sites/default/files/document/120201084329386_2008_2_Classification_Code6.pdf (accessed on 23 September 2012).

- Barnes, C. Discrimination: disabled people and the media. Contact 1991, 70, 15–19. [Google Scholar]

- Harnett, A. Escaping the ôevil avengerö and the ôsupercripö: images of disability in popular television. Irish Communications Review 2000, 8, 21–29. [Google Scholar]

- Kama, A. Supercrips versus the pitiful handicapped: Reception of disabling images by disabled audience members. Communications 2004, 29, 447–466. [Google Scholar]

- Meeuf, R. John Wayne as" Supercrip": Disabled Bodies and the Construction of" Hard" Masculinity in The Wings of Eagles. Cinema Journal 2009, 48, 88–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Booher, A.K. Docile bodies, supercrips and the plays of prosthetics. International Journal of Feminist Approaches to Bioethics 2010, 3, 63–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardin, M.; Hardin, B. How elite wheelchair athletes relate to sport media. The Paralympic Games: Empowerment or sideshow 2008, 25–33. [Google Scholar]

- The Associated Press, “Wheel Chair Unit a Victor in Sports: Polio Victims, All with Pan-American Airways, Tell of English Triumphs,”. New York Times 1955, 16.

- Vecsey, G. Other games headed to town. New York Times 2002, D1. [Google Scholar]

- Berger, R.J. Disability and the Dedicated Wheelchair Athlete. Journal of Contemporary Ethnography 2008, 37, 647–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherney, J.L.; Lindemann, K. Sporting Images of Disability. Examining identity in sports media 2009, 195, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Olenik, L.M.; Matthews, J.M.; Steadward, R.D. Women, Disability and Sport: Unheard Voices. Canadian Woman Studies 1995, 15, 4. [Google Scholar]

- Schell, L.A.; Duncan, M.C. A content analysis of CBS's coverage of the 1996 Paralympic Games. Adapted Physical Activity Quarterly 1999, 16, 27–47. [Google Scholar]

- Scott Hogsett as told do Dana Adam Shapiro Not One for the Sidelines. New York Times (1923-Current file) 2004, 140.

- Ellis, K. Beyond the Aww Factor: Human interest Profiles of Paralympians and the media navigation of physical difference and social stigma. Asia Pacific Media Educator 2009, 1, 23–36. [Google Scholar]

- By Tony Kornheiser Special to The New York Times Desire Spurs Top Athletes On Wheels. New York Times (1923-Current file) 1976, 39.

- Wilson, E. Model and Front-Runner. New York Times 2011, E1. [Google Scholar]

- Dewan, S. A long-ago refuge still tends to the needs of polio survivors. 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Howard, A.R. Paralyzed Athletes, With Big Victories Behind Them, Open Olympics This Week. New York Times (1923-Current file) 1960, 134. [Google Scholar]

- Purdue, D.E.J.; Howe, P.D. See the sport, not the disability: exploring the Paralympic paradox. Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health 2012, 4, 189–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trumbull, R. 369 to compete in Paralympics: wheelchair games due to open at Tokyo today. New York Times 1964, S2. [Google Scholar]

- Special to The New York Times Elite Athlete Chases More Than a Medal. New York Times 1991, B11.

- Litsky, F. A Blind Rider Races Into the Nationals. New York Times 1997, 31. [Google Scholar]

- On your own; One-Legged Runner Tries to Inspire Others. New York Times 1990, C10.

- Museler, C. Unforeseen Change of Course. New York Times 2008, 0-D. [Google Scholar]

- Wolbring, G. Paralympians outperforming Olympians: An increasing challenge for Olymp-ism and the Paralympic and Olympic movement. Sport, Ethics and Philosophy 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Wolbring, G.; Legg, D.; Stahnisch, F.W. Meaning of Inclusion throughout the History of the Paralympic Games and Movement. The International Journal of Sport & Society 2010, 1, 81–93. [Google Scholar]

- Howard, H. Park city center offers a new rush for athletes with disabilities. New York Times 2005, D2. [Google Scholar]

- Schwarz, A. The Art and Science of Wheelchair Basketball. New York Times 2008, SP2. [Google Scholar]

- El-Bashir, T. Amputee takes sheer speed and will to Atlanta. New York Times 1996, B13. [Google Scholar]

- Dicker, R. New equipment stirs division within wheelchair ranks. New York Times 2000, SP9. [Google Scholar]

- Vecsey, G. Sports of The Times; Still Living on the Line. New York Times 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Martin, D. After the olympics, games of another kind begin. New York Times 1988, A1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helou, P. Article 7 -- No title. New York Times 1991, L14. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan, B. It's Back to Barcelona: Let the Games Begin Once Again! New York Times 1992, CN1. [Google Scholar]

- Hirschberg, L. Hot wheels. New York Times 2005, 42–47. [Google Scholar]

- Holden, S. These Gladiators on Wheels Are Not Playing for a Hug. New York Times 2005, E8. [Google Scholar]

- Holden, S. These gladiators on wheels are not playing for a hug. 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Wheelchair games; Racing Off To New Athletic Titles. New York Times 1993, B18.

- Longman, J. New York City Marathon; Proceeding With Caution. New York Times 1995, B9. [Google Scholar]

- Longman, J. New York City Marathon; Proceeding With Caution. New York Times 1995, B9. [Google Scholar]

- Lindfelt, M. Elite sports in tension: making identification the core moral norm for professional sports in the future. Sport in Society: Cultures, Commerce, Media, Politics 2010, 13, 186–198. [Google Scholar]

- Billings, A.C. Talking Around Race: Stereotypes, Media and the Twenty-First Century Collegiate Athlete. Wake Forest JL & Pol'y 2012, 2, 199–533. [Google Scholar]

- Grainger, A.; Newman, J.I.; Andrews, D.L. Chapter 27-Sport, the Media and the Construction of Race. Routledge Online Studies on the Olympic and Paralympic Games 2012, 1, 482–504. [Google Scholar]

- Knight, J.L.; Giuliano, T.A. He's a Laker; she's a looker: The consequences of gender-stereotypical portrayals of male and female athletes by the print media. Sex Roles 2001, 45, 217–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polney, M.P. Gendered representations of college athletes: a content analysis of newspaper coverage of March Madness. 2012.

- Riebock, A. Sexualized Representation of Female Athletes in the Media: How Does it Affect Collegiate Female Athlete Body Perceptions? 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Hachman, M. Prosthetic Limbs Give Runner Unfair Advantage. Extremetech Magazine Home Page. Available online: http://www.extremetech.com/computing/80926-prosthetic-limbs-give-runner-unfair-advantage (accessed on 23 September 2012).

- Michaelis, V. Running down a dream: Leg amputee makes U.S. track team. USA Today Home Page. Available online: http://www.usatoday.com/sports/olympics/summer/track/2010-04-25-amputee-runner_N.htm (accessed on 23 September 2012).

- Seymour, W. Remaking the Body: Rehabilitation and Change, 1998.

© 2013 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open-access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/).

Share and Cite

Tynedal, J.; Wolbring, G. Paralympics and Its Athletes Through the Lens of the New York Times. Sports 2013, 1, 13-36. https://doi.org/10.3390/sports1010013

Tynedal J, Wolbring G. Paralympics and Its Athletes Through the Lens of the New York Times. Sports. 2013; 1(1):13-36. https://doi.org/10.3390/sports1010013

Chicago/Turabian StyleTynedal, Jeremy, and Gregor Wolbring. 2013. "Paralympics and Its Athletes Through the Lens of the New York Times" Sports 1, no. 1: 13-36. https://doi.org/10.3390/sports1010013

APA StyleTynedal, J., & Wolbring, G. (2013). Paralympics and Its Athletes Through the Lens of the New York Times. Sports, 1(1), 13-36. https://doi.org/10.3390/sports1010013