Intergenerational Judo: Synthesising Evidence- and Eminence-Based Knowledge on Judo across Ages

Abstract

1. Introduction

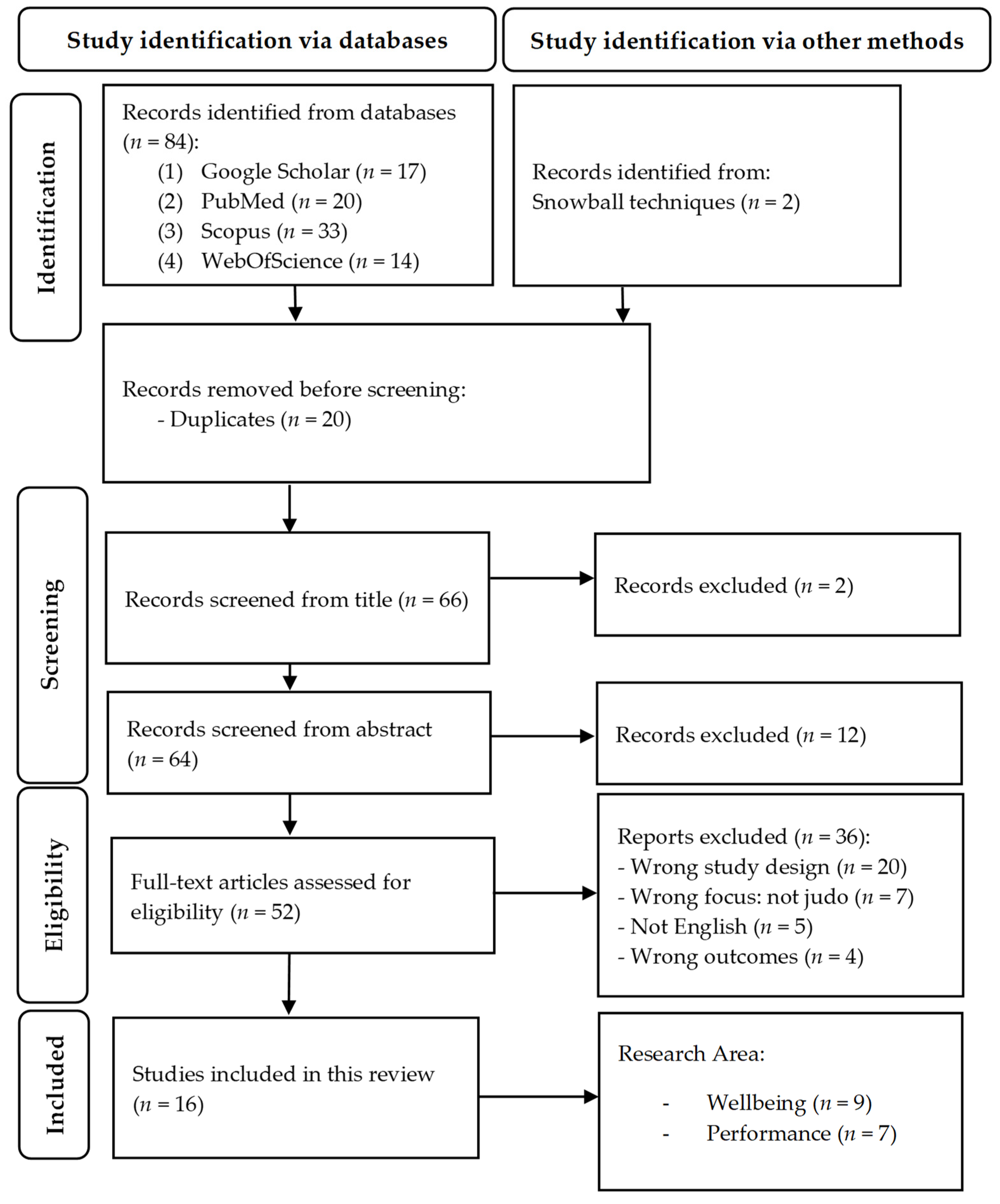

2. Methods

2.1. Design

2.2. Protocol and Registration

2.3. Eligibility (i.e., Inclusion and Exclusion) Criteria

2.4. Information Search and Study Selection Process

2.5. Data Extraction, Analysis, and Synthesis

2.6. Quality Assessment of Systematic Literature Reviews

2.7. Online Educational Courses for Judo Coaches

2.8. Analysis and Quality Assessment of Online Educational Courses for Judo Coaches

| Author (Year) | Country a | Research Area | Journal b | Quality Assessment | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Score | Evaluation Rating | ||||

| Barreto et al. (2024) [50] | Brazil | Performance | IDO | 7/8 | Excellent |

| Barreto et al. (2022) [51] | Brazil | Performance | Front Psychol | 8/8 | Excellent |

| Ciaccioni et al. (2019) [52] | Italy | Wellbeing | JSCR | 7/8 | Excellent |

| Gutierrez-Garcia et al. (2018) [53] | Spain | Wellbeing | IDO | 5/8 | Good |

| Hlasho et al. (2023) [54] | South Africa | Performance | Heliyon | 4/8 | Fair |

| Lakicevic et al. (2020) [55] | Italy | Wellbeing | Nutrients | 7/8 | Excellent |

| Lakicevic et al. (2024) [56] | Italy | Wellbeing | ERAP | 5/8 | Good |

| Lockhart et al. (2022) [57] | UK | Wellbeing | IJERPH | 7/8 | Excellent |

| Mooren et al. (2023) [58] | Netherlands | Wellbeing | TSM | 8/8 | Excellent |

| Palumbo et al. (2023) [43] | Italy | Wellbeing | Sports | 6/8 | Good |

| Pečnikar et al. (2020) [59] | Slovenia | Wellbeing | AoB | 5/8 | Good |

| Pocecco et al. (2013) [60] | Austria | Wellbeing | BJSM | 3/8 | Fair |

| Rossi et al. (2022) [61] | Italy | Performance | IJERPH | 6/8 | Good |

| Schoof et al. (2024) [62] | Netherlands | Performance | IJSSC | 6/8 | Good |

| Sterkowicz et al. (2019) [63] | Poland | Performance | Sports | 5/8 | Good |

| Sterkowicz et al. (2014) [64] | Poland | Performance | JSCR | 3/8 | Fair |

3. Results

3.1. Study Selection and Data Collection

3.2. Review Characteristics

3.3. Judo Practitioners, Topics, and Results

3.4. Study Quality of the Included Reviews

3.5. Quality of Online Judo Courses

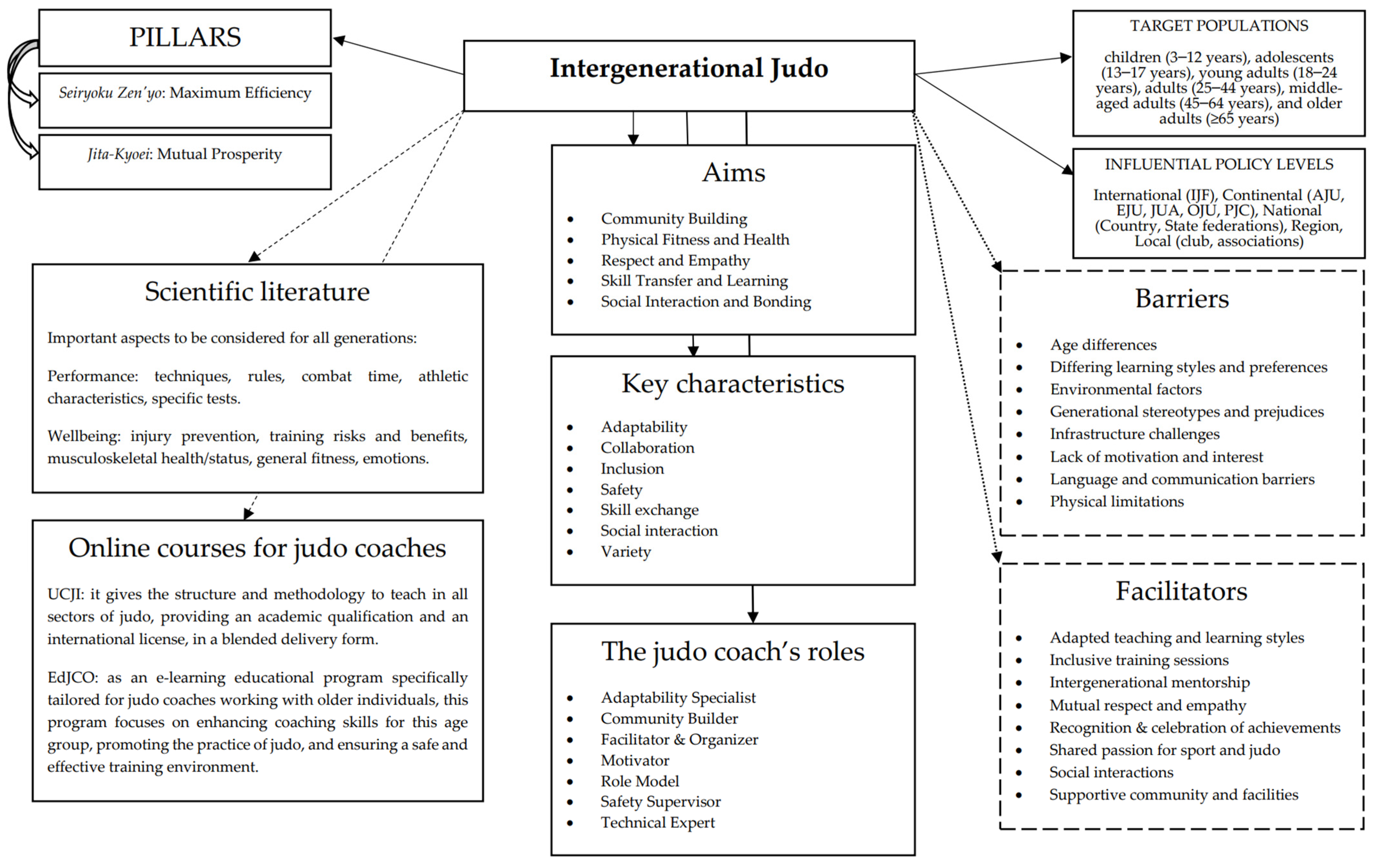

3.6. Novel Framework for Intergenerational Judo Activities including Recommended Online Courses for Judo Coaches

4. Discussion

Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- European Commission, D.-G.f.E. Youth, Sport and Culture. In Mapping Study on the Intergenerational Dimension of Sport—Final Report to the European Commission; Publications Office: North Point, Hong Kong, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Toffano Martini, E.; Zanato Orlandini, O. Ricostruire la reciprocità tra le generazioni a partire da bambini e anziani. Progett. Generazioni Bambini E Anziani Due Stagioni Della Vita A Confronto.-(Sci. Dell’educazione) 2012, 154, 241–253. [Google Scholar]

- Chiosso, G. Gli anziani depositari di memoria ed esperienza. Progett. Generazioni Bambini E Anziani Due Stagioni Della Vita A Confronto.-(Sci. Dell’educazione) 2012, 154, 55–60. [Google Scholar]

- Kolb, D.A. Experiential Learning: Experience as the Source of Learning and Development; FT Press: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Kuehne, V.S. The state of our art: Intergenerational program research and evaluation: Part one. J. Intergenerational Relatsh. 2003, 1, 145–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox, S.; Giles, H. Accommodating Intergenerational Contact—A Critique and Theoretical-Model. J. Aging Stud. 1993, 7, 423–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neugarten, B.; Havighurst, R.; Tobin, S. Personality and patterns of aging. In Middle Age and Aging; Neugarten, B., Ed.; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1968; pp. 173–177. [Google Scholar]

- Barton, H. Effects of an intergenerational program on the attitudes of emotionally disturbed youth toward the elderly. Educ. Gerontol. 1999, 25, 623–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.; Kim, J.; Lee, J.-M.; Seo, D.-C.; Jung, H.C. Intergenerational Taekwondo Program: A Narrative Review and Practical Intervention Proposal. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 5247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaplan, M.S. International programs in schools: Considerations of form and function. Int. Rev. Educ. 2002, 48, 305–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatton-Yeo, A.; Ohsako, T. Intergenerational Programmes: Public Policy and Research Implications—An International Perspective; UNESCO Institute for Education: Hamburg, Germany, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Ellis, S.W.; Granville, G. Developing Theory into Practice: Researching Intergenerational Exchange. Educ. Ageing 1999, 14, 231–248. [Google Scholar]

- Rosebrook, V. Intergenerational connections enhance the personal/social development of young children. Int. J. Early Child. 2002, 34, 30–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, F.; Zhang, H.; Wang, H.Y.; Liu, L.F.; Zhang, X.G. Barriers and facilitators to older adult participation in intergenerational physical activity program: A systematic review. Aging Clin. Exp. Res. 2024, 36, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, F.; Sousa, H.; Gouveia, E.R.; Lopes, H.; Peralta, M.; Martins, J.; Murawska-Cialowicz, E.; Zurek, G.; Marques, A. School-Based Family-Oriented Health Interventions to Promote Physical Activity in Children and Adolescents: A Systematic Review. Am. J. Health Promot. 2023, 37, 243–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciaccioni, S.; Castro, O.; Bahrami, F.; Tomporowski, P.D.; Capranica, L.; Biddle, S.J.H.; Vergeer, I.; Pesce, C. Martial arts, combat sports, and mental health in adults: A systematic review. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2024, 70, 102556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Tabeshian, R.; Mustafa, H.; Zehr, E.P. Using Martial Arts Training as Exercise Therapy Can Benefit All Ages. Exerc. Sport Sci. Rev. 2024, 52, 23–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salgado, V.C.; Jauregui, Z.G. People with disabilities and martial arts: A systematic review of the literature between 1990 and 2020. Agora Para La Educ. Fis. Y El Deporte 2022, 24, 278–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jesus, G.B.d.; Impolcetto, F.M. Academic production in the field of combat sports: The case of judo and the studies of the principles and values of the sport. Mot. Rev. Educ. Física 2022, 28, e10220011422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shishida, F.; Sakaguchi, M.; Satoh, T.; Kawakami, Y. Technical principles of atemi-waza in the first technique of the itsutsu-no-kata in judo: From a viewpoint of jujutsu like atemi-waza. a broad perspective of application in honoured self-defence training. Arch. Budo 2017, 13, 255–269. [Google Scholar]

- Kons, R.L.; Athayde, M.S.D.; Ceylan, B.; Franchini, E.; Detanico, D. Analysis of video review during official judo matches: Effects on referee’s decision and match results. Int. J. Perform. Anal. Sport 2021, 21, 555–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutierrez-Santiago, A.; Gutierrez-Santiago, J.A.; Prieto-Lage, I.; Parames-Gonzalez, A.; Suarez-Iglesias, D.; Ayan, C. A Scoping Review on Para Judo. Am. J. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2023, 102, 931–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borkowski, L.; Faff, J.; Starczewska-Czapowska, J. Evaluation of the aerobic and anaerobic fitness in judoists from the Polish National Team. Biol. Sport 2001, 18, 107–117. [Google Scholar]

- Klimczak, J.; Krzemieniecki, L.A.; Mosler, D. Martial arts bibliotherapy—The possibility of compensating the negative effects of the continuous education for aggression by electronic media and the aggressive interpersonal relationship of children and adults. Arch. Budo 2015, 11, 395–401. [Google Scholar]

- Kano, J. Kodokan Judo: The Essential Guide to Judo by Its Founder Jigoro Kano; Kodansha International: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Shishida, F. Judo’s techniques performed from a distance: The origin of Jigoro Kano’s concept and its actualization by Kenji Tomiki. Arch. Budo 2010, 6, 165–171. [Google Scholar]

- Maslinski, J.; Piepiora, P.; Cieslinski, W.; Witkowski, K. Original methods and tools used for studies on the body balance disturbation tolerance skills of the Polish judo athletes from 1976 to 2016. Arch. Budo 2017, 13, 285–296. [Google Scholar]

- Torres-Luque, G.; Hernandez-Garcia, R.; Escobar-Molina, R.; Garatachea, N.; Nikolaidis, P.T. Physical and Physiological Characteristics of Judo Athletes: An Update. Sports 2016, 4, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Franchini, E.; Del Vecchio, F.B.; Matsushigue, K.A.; Artioli, G.G. Physiological profiles of elite judo athletes. Sports Med. 2011, 41, 147–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowalczyk, M.; Zgorzalewicz-Stachowiak, M.; Blach, W.; Kostrzewa, M. Principles of Judo Training as an Organised Form of Physical Activity for Children. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 1929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Crée, C. Kōdōkan Jūdō’s three orphaned forms of counter techniques—Part 1: The gonosen-no-kata—“Forms of post-attack initiative counter throws”. Arch. Budo 2015, 11, 93–123. [Google Scholar]

- De Crée, C. Kōdōkan jūdō’s three orphaned forms of counter techniques—Part 3: The katame-waza ura-no-kata—“forms of reversing controlling techniques”. Arch. Budo 2015, 11, 155–171. [Google Scholar]

- De Crée, C. Kōdōkan Jūdō’s three orphaned forms of counter techniques—Part 2: The nage-waza ura-no-kata—“Forms of reversing throwing techniques”. Arch. Budo 2015, 11, 125–154. [Google Scholar]

- Kalina, R.M.; Witkowski, K. Brigadier Josef Herzog, 8th dan judo (1928–2016), the ambassador of Jigoro Kano’s universal mission „Judo in the Mind”. Arch. Budo 2022, 18, 363–368. [Google Scholar]

- Magnanini, A. Jigoro Kano tra judo e educazione: Un dialogo per la formazione degli uomini. Ric. Pedagog. 2013, 190, 19–26. [Google Scholar]

- Arkkukangas, M.; Strömqvist Bååthe, K.; Ekholm, A.; Tonkonogi, M. High Challenge Exercise and Learning Safe Landing Strategies among Community-Dwelling Older Adults: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 7370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jadczak, A.D.; Verma, M.; Headland, M.; Tucker, G.; Visvanathan, R. A Judo-Based Exercise Program to Reduce Falls and Frailty Risk in Community-Dwelling Older Adults: A Feasibility Study. J. Frailty Aging 2023, 13, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciaccioni, S.; Guidotti, F.; Palumbo, F.; Forte, R.; Galea, E.; Sacripanti, A.; Lampe, N.; Lampe, S.; Jelusic, T.; Bradic, S.; et al. Development of a Sustainable Educational Programme for Judo Coaches of Older Practitioners: A Transnational European Partnership Endeavor. Sustainability 2024, 16, 1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palumbo, F.C.S.; Guidotti, F.; Forte, R.; Galea, E.; Sacripanti, A.; Lampe, N.; Lampe, S.; Jelusic, T.; Bradic, S.; Lascau, M.L.; et al. Need of Education for Coaching Judo for Older Adults: The EdJCO Focus Groups. Sports 2023, 11, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Judo Federation. International Judo Federation Academy. Available online: https://academy.ijf.org/ (accessed on 19 April 2024).

- Ciaccioni, S.; Palumbo, F.; Forte, R.; Galea, E.; Kozsla, T.; Sacripanti, A.; Milne, A.; Lampe, N.; Lampe, S.; Jelušić, T.; et al. Educating Judo Coaches For Older Practitioners. Arts Sci. Judo 2022, 2, 63–66. [Google Scholar]

- Ciaccioni, S.; Guidotti, F.; Palumbo, F.; Forte, R.; Galea, E.; Sacripanti, A.; Lampe, N.; Lampe, S.; Jelusic, T.; Bradic, S.; et al. Judo for older adults: The coaches’ knowledge and needs of education. Front. Sports Act. Living 2024, 6, 1375814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palumbo, F.; Ciaccioni, S.; Guidotti, F.; Forte, R.; Sacripanti, A.; Capranica, L.; Tessitore, A. Risks and Benefits of Judo Training for Middle-Aged and Older People: A Systematic Review. Sports 2023, 11, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonald, K.; Callan, M. The British Judo Coach Education Programme: Introducing Judo to an Older Population-for Safer Falling and Ageing well. In Proceedings of the European Judo Union Scientific and Professional Conference: “Applicable Research in Judo”, Porec, Croatia, 19–20 June 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Int. J. Surg. 2021, 88, 105906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollock, M.; Fernandes, R.M.; Pieper, D.; Tricco, A.C.; Gates, M.; Gates, A.; Hartling, L. Preferred Reporting Items for Overviews of Reviews (PRIOR): A protocol for development of a reporting guideline for overviews of reviews of healthcare interventions. Syst. Rev. 2019, 8, 335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spirduso, W.F.K.; MacRae, P.G. Physical Dimensions of Aging, 2nd ed.; Human Kinetics: Champaign, IL, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Shraim, K. Quality Standards in Online Education The ISO/IEC 40180 Framework. Int. J. Emerg. Technol. 2020, 15, 22–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minnesota State Board of Assessors. Online Course Development Checklist; Minnesota State Board of Assessors: St. Paul, MN, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Barreto, L.B.M.; Duarte, T.S.; Ahmedov, F.; Aedo-munoz, E.A.; Martins, F.J.A.; Soto, D.A.S.; Miarka, B.; Brito, C.J. Combat Time in International Female Judo: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Ido Mov. Cult.-J. Martial Arts Anthropol. 2024, 24, 39–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barreto, L.B.M.; Santos, M.A.; Fernandes Da Costa, L.O.; Valenzuela, D.; Martins, F.J.; Slimani, M.; Bragazzi, N.L.; Miarka, B.; Brito, C.J. Combat Time in International Male Judo Competitions: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 817210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ciaccioni, S.; Condello, G.; Guidotti, F.; Capranica, L. Effects of Judo Training on Bones: A Systematic Literature Review. J. Strength. Cond. Res. 2019, 33, 2882–2896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gutierrez-Garcia, C.; Astrain, I.; Izquierdo, E.; Gomez-Alonso, M.T.; Yague, J.M. Effects of judo participation in children: A systematic review. Ido Mov. Cult.-J. Martial Arts Anthropol. 2018, 18, 63–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hlasho, T.S.; Thaane, T.; Mathunjwa, M.L.; Shaw, B.S.; Shandu, N.M.; Shaw, I. Past, Present and Future of Judo: A Systematic Review. Heliyon 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakicevic, N.; Roklicer, R.; Bianco, A.; Mani, D.; Paoli, A.; Trivic, T.; Ostojic, S.M.; Milovancev, A.; Maksimovic, N.; Drid, P. Effects of Rapid Weight Loss on Judo Athletes: A Systematic Review. Nutrients 2020, 12, 1220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lakicevic, N.; Thomas, E.; Isacco, L.; Tcymbal, A.; Pettersson, S.; Roklicer, R.; Tubic, T.; Paoli, A.; Bianco, A.; Drid, P. Rapid weight loss and mood states in judo athletes: A systematic review. Eur. Rev. Appl. Psychol.-Rev. Eur. De Psychol. Appl. 2024, 74, 100933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lockhart, R.; Blach, W.; Angioi, M.; Ambrozy, T.; Rydzik, L.; Malliaropoulos, N. A Systematic Review on the Biomechanics of Breakfall Technique (Ukemi) in Relation to Injury in Judo within the Adult Judoka Population. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 4259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mooren, J.; von Gerhardt, A.L.; Hendriks, I.T.J.; Tol, J.L.; Koëter, S. Epidemiology of Injuries during Judo Tournaments. Transl. Sports Med. 2023, 2023, 2713614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pečnikar Oblak, V.; Karpljuk, D.; Vodičar, J.; Simenko, J. Inclusion of people with intellectual disabilities in judo: A systematic review of literature. Arch. Budo 2020, 16, 245–260. [Google Scholar]

- Pocecco, E.; Ruedl, G.; Stankovic, N.; Sterkowicz, S.; Del Vecchio, F.B.; Gutierrez-Garcia, C.; Rousseau, R.; Wolf, M.; Kopp, M.; Miarka, B.; et al. Injuries in judo: A systematic literature review including suggestions for prevention. Br. J. Sports Med. 2013, 47, 1139–1143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rossi, C.; Roklicer, R.; Tubic, T.; Bianco, A.; Gentile, A.; Manojlovic, M.; Maksimovic, N.; Trivic, T.; Drid, P. The Role of Psychological Factors in Judo: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 2093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoof, S.; Sliedrecht, F.; Elferink-Gemser, M.T. Throwing it out there: Grip on multidimensional performance characteristics of judoka—A systematic review. Int. J. Sports Sci. Coach. 2024, 19, 908–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sterkowicz-Przybycien, K.; Fukuda, D.H.; Franchini, E. Meta-Analysis to Determine Normative Values for the Special Judo Fitness Test in Male Athletes: 20+ Years of Sport-Specific Data and the Lasting Legacy of Stanislaw Sterkowicz. Sports 2019, 7, 194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sterkowicz-Przybycien, K.L.; Fukuda, D.H. Establishing normative data for the special judo fitness test in female athletes using systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2014, 28, 3585–3593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kujach, S.; Chroboczek, M.; Jaworska, J.; Sawicka, A.; Smaruj, M.; Winklewski, P.; Laskowski, R. Judo training program improves brain and muscle function and elevates the peripheral BDNF concentration among the elderly. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 13900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ludyga, S.; Mücke, M.; Leuenberger, R.; Bruggisser, F.; Pühse, U.; Gerber, M.; Capone-Mori, A.; Keutler, C.; Brotzmann, M.; Weber, P. Behavioral and neurocognitive effects of judo training on working memory capacity in children with ADHD: A randomized controlled trial. Neuroimage Clin. 2022, 36, 103156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ludyga, S.; Tränkner, S.; Gerber, M.; Pühse, U. Effects of Judo on Neurocognitive Indices of Response Inhibition in Preadolescent Children: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2021, 53, 1648–1655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hong, H.J.; Hong, S.H. Fighting for Olympic dreams and life beyond: Olympian judokas on striving for glory and tackling post-athletic challenges. Front. Psychol. 2023, 14, 1269174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miarka, B.; Marques, J.B.; Franchini, E. Reinterpreting the history of women’s judo in Japan. Int. J. Hist. Sport 2011, 28, 1016–1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciaccioni, S.; Pesce, C.; Forte, R.; Presta, V.; Di Baldassarre, A.; Capranica, L.; Condello, G. The Interlink among Age, Functional Fitness, and Perception of Health and Quality of Life: A Mediation Analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 6850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chan, U.; Ayliffe, L.; Visvanathan, R.; Headland, M.; Verma, M.; Jadczak, A.D. Judo-based exercise programs to improve health outcomes in middle-aged and older adults with no judo experience: A scoping review. Geriatr. Gerontol. Int. 2023, 23, 163–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ciaccioni, S.; Capranica, L.; Forte, R.; Chaabene, H.; Pesce, C.; Condello, G. Effects of a Judo Training on Functional Fitness, Anthropometric, and Psychological Variables in Old Novice Practitioners. J. Aging Phys. Act. 2019, 27, 831–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ciaccioni, S.; Capranica, L.; Forte, R.; Pesce, C.; Condello, G. Effects of a 4-month judo program on gait performance in older adults. J. Sports Med. Phys. Fit. 2020, 60, 685–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciaccioni, S.; Pesce, C.; Capranica, L.; Condello, G. Effects of a judo training program on falling performance, fear of falling and exercise motivation in older novice judoka. Ido Mov. Culture. J. Martial Arts Anthropol. 2021, 21, 9–17. [Google Scholar]

- Guidotti, F.; Demarie, S.; Ciaccioni, S.; Capranica, L. Relevant Sport Management Knowledge, Competencies, and Skills: An Umbrella Review. Sustainability 2023, 15, 9515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guidotti, F.; Demarie, S.; Ciaccioni, S.; Capranica, L. Knowledge, Competencies, and Skills for a Sustainable Sport Management Growth: A Systematic Review. Sustainability 2023, 15, 7061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guidotti, F.; Demarie, S.; Ciaccioni, S.; Capranica, L. Sports Management Knowledge, Competencies, and Skills: Focus Groups and Women Sports Managers’ Perceptions. Sustainability 2023, 15, 10335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perazzetti, A.; Dopsaj, M.; Nedeljkovic, A.; Mazic, S.; Tessitore, A. Survey on Coaching Philosophies and Training Methodologies of Water Polo Head Coaches from Three Different European National Schools. Kinesiology 2023, 55, 49–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Author (Year) | Judo Practitioners a | Topic | Results | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (Years) | Sex (%) | Level | Sample | |||

| Barreto et al. (2024) [50] | Adolescents to young adults | F = 100 M = 0 | International | 1485 | Following each rule change (2010, 2013, 2015, 2017, and 2018), the CT changed towards homogeneity by weight divisions and increased Golden Score occurrence. | |

| Combat time (CT) | ||||||

| Barreto et al. (2020) [51] | Adolescents to young adults | F = 0 M = 100 | International | 2562 | Combat time (CT) | Following each rule change (2010, 2013, 2017, and 2018), the CT changed towards homogeneity by weight divisions and increased Golden Score occurrence. |

| Ciaccioni et al. (2019) [52] | Children to older people (55.0 ± 41.3) | F only = 38.2 M only = 20.6 Both = 32.4 NR = 8.8 | Novice to international | 1865 | Bones | Positive association between judo and bone health/status emerged, with site-specific BMD accrual in judoka across the lifespan, bone turnover markers revealing a hypermetabolic status in high-level judo athletes, and fall techniques seemingly reducing bone impact force and velocity with respect to “natural” falls. |

| Gutierrez-Garcia et al. (2018) [53] | Children (5 to 10) | F = 20 M = 80 | NR | 602 | Psychophysical effects | Young judoka showed improved fitness (arm bone density, flexibility, muscular endurance, agility) and reduced subcutaneous fat levels, similar to other sports, but also higher levels of anger than their peers. |

| Hlasho et al. (2023) [54] | NA | NA | NA | NA | Athlete success | Whilst volunteer-led federations seem inefficient and unsustainable for successfully planning an athlete’s international success pathway, professionalism and commercialization (e.g., financial resources, clear long-term plan, and full-time coaching and administration staff) appear central to improving athlete’s performance, participation, and efficacy in the athlete’s management systems. |

| Lakicevic et al. (2020) [55] | Young adults (20.5 ± 3.2) | NR | Competitive | 1103 | Rapid weight loss (RWL) | Inconsistent physiological data and biomarkers in athletes emerged, with psychological wellbeing parameters being more reliable. RWL increased tension, anger, and fatigue, while vigour decreased. The impact of RWL on performance was unclear. More research is needed to ensure athletes’ health, fairness, and sport benefits. |

| Lakicevic et al. (2024) [56] | Adolescents to young adults | F = 20 M = 80 | Competitive | 172 | Rapid weight loss (RWL) | RWL leads to a significant rise in tension and a notable decrease in vigour. When judo athletes experience a weekly RWL of ≥5%, their mood states worsen significantly, regardless of gender. |

| Lockhart et al. (2022) [57] | Adults (24 ± NR; range: 18–65) | F = 6 M = 94 | Novice to elite | 158 | Ukemi (breakfall techniques) and injury | Ukemi reduces kinematics compared to direct occipital contact, preventing head and neck injuries, with novice judoka showing larger hip, knee, and trunk flexion angles. A weak link exists between neck strength and improved ukemi, but fatigue negatively impacts breakfall skill. |

| Mooren et al. (2023) [58] | Adolescents to adults (range: 15–47) | NR | Competitive | 361581 | Injuries | Injury rates in judo tournaments vary, with 2.5–72.5% requiring medical evaluation and 1.1–4.1% causing game discontinuation. Common injury locations are the head, hand, knee, elbow, and shoulder, with sprains being the most frequent type, followed by contusions, skin lacerations, strains, and fractures. Injuries occur more often during standing fights. |

| Palumbo et al. (2023) [43] | Middle-aged and older people (63 ± 12) | F = 47 M = 53 | Novice to expert | 1392 | Risks and benefits | On average, judo training later in life involves 2 ± 1 sessions per week, each lasting 61 ± 17 min, over a period of 7 ± 6 months. In the literature, health, functional fitness, and psychosocial aspects are key themes of judo training exposure and outcomes. Despite some methodological flaws, the current data suggest that judo training has positive effects as age advances. |

| Pečnikar et al. (2020) [59] | Children to adults | NR | Recreational to competitive | NR | Adapted judo | Increasingly used therapeutically, recreationally, and competitively, judo can be applied to people with special conditions (e.g., autism, ADHD, Down syndrome, intellectual and behavioural disorders), focusing on quality of life, motor skills, hyperactivity, health promotion, match analysis, and psychosocial effects. Low sample sizes and diverse research types limit the results’ generalisability. |

| Pocecco et al. (2013) [60] | Children to adults | NR | Competitive | NR | Injuries | 11–12% injury risk (2008–2012 Olympic Games). Common: sprains, strains, and contusions (knee, shoulder, and fingers). Rare: brain and spine. Chronic: finger joints, lower back, and ears. Sex differences: inconsistent. Potential links: nutrition, hydration, weight cycling, psychological factors. |

| Rossi et al. (2022) [61] | Adolescents to adults | F = 34 M = 66 | Regional to elite | 850 | Psychology of performance | ↑ Tension, anger, anxiety, and nervousness in athletes facing defeat. ↓ Tension, anger, anxiety, and nervousness and ↑ motivation in athletes experiencing better performance. |

| Schoof et al. (2024) [62] | Adolescents to young adults | NR | Semi-elite to world-class elite | NR | Performance characteristics | Among the studied anthropometrical, physiological, technical, tactical, and psychological aspects, a broad set of physiological characteristics is needed to manage the demands of judo combats. Grip fighting-related characteristics discriminate between judoka of different performance levels. |

| Sterkowicz et al. (2019) [63] | Adolescents to young adults | M = 100 | Novice to elite | 724: 515 seniors & 209 juniors | Special Judo Fitness Test (SJFT) | Senior athletes (>21 years old) show a higher total number of throws and heart rate (HR) immediately after the SJFT, with limited differences for HR one minute after the SJFT between groups. Compared to juniors (<21 years old), more advanced athletes present a lower SJFT index and thus a better overall performance. |

| Sterkowicz et al. (2014) [64] | Adolescents to young adults | F = 100 | Regional to international | 161: 96 seniors & 65 juniors | Special Judo Fitness Test (SJFT) | According to the meta-analysis, the SJFT index shows a large effect size between ages, with seniors completing more throws than juniors. The smaller effect of HR immediately after and 1 min after the SJFT results in the throw number being a more significant factor in the differences between age categories. |

| Course | Aim and Typology | Modules | NSQOL Evaluation Criteria (Pt.) and Overall Rating | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | B | C | D | E | F | G | Rating | |||

| UCJI | Training instructors for youth and beginner athletes, combining theory and practical coaching, as well as judo techniques, fostering ongoing learning within and outside the IJF Academy - Mandatory | 1. History of Judo 2. Classification of Judo—1 3. Culture of Judo 4. About IJF 5. Classification of Judo—2 6. Role of Instructor 7. Exercise Physiology I. 8. Classification of Judo—3 9. First Aid and Safety 10. Classification of Judo—4 11. LTAD Stages 12. Nage no Kata 13. Refereeing Rules 14. Practical Session | 14 | 18 | 24 | 13 | 12 | 8 | 7 | 96/111 - Good |

| EdJCO | Empowering judo coaches with proper knowledge, skills, and attitudes for teaching and training older practitioners - Vocational | 1. Organization and Environment 2. Aging Process 3. Safety and First Aid 4. Physiology and fitness 5. Psychology and Mental Health 6. Teaching and Training | 15 | 16 | 19 | 11 | 12 | 7 | 7 | 87/111 - Good |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ciaccioni, S.; Perazzetti, A.; Magnanini, A.; Kozsla, T.; Capranica, L.; Doupona, M. Intergenerational Judo: Synthesising Evidence- and Eminence-Based Knowledge on Judo across Ages. Sports 2024, 12, 177. https://doi.org/10.3390/sports12070177

Ciaccioni S, Perazzetti A, Magnanini A, Kozsla T, Capranica L, Doupona M. Intergenerational Judo: Synthesising Evidence- and Eminence-Based Knowledge on Judo across Ages. Sports. 2024; 12(7):177. https://doi.org/10.3390/sports12070177

Chicago/Turabian StyleCiaccioni, Simone, Andrea Perazzetti, Angela Magnanini, Tibor Kozsla, Laura Capranica, and Mojca Doupona. 2024. "Intergenerational Judo: Synthesising Evidence- and Eminence-Based Knowledge on Judo across Ages" Sports 12, no. 7: 177. https://doi.org/10.3390/sports12070177

APA StyleCiaccioni, S., Perazzetti, A., Magnanini, A., Kozsla, T., Capranica, L., & Doupona, M. (2024). Intergenerational Judo: Synthesising Evidence- and Eminence-Based Knowledge on Judo across Ages. Sports, 12(7), 177. https://doi.org/10.3390/sports12070177