Abstract

Sports, apart from providing entertainment, can provide an escape from everyday troubles, a community to belong to, and an opportunity to connect to the wider world. As such, sports have contributed to the unification of people, the development of peace and tolerance, and the empowerment of women and young people globally. However, sports’ widespread popularity has also contributed to “big money” opportunities for sports organizations, sporting venues, athletes, and sponsors that have created an environment riddled with ethical dilemmas that make headlines, resulting in protests and violence, and often leave society more divided. A current ethical dilemma faced by agents associated with the Olympic games serves to demonstrate the magnitude and challenges related to resolving ethical dilemmas in the sport industry. A decision-making framework is applied to this current sport’s ethical dilemma, as an example of how better ethical decision making might be achieved.

1. Introduction

The global sports market wields tremendous influence over society [1]. Athletes, corporations, advertisers, and sport governing bodies have more opportunities to generate millions than ever before [2]. Fans are awestruck by their favourite athlete, team and sporting event, with athletes acknowledged as idols whose behaviours are mimicked by young and old persons alike. Researchers have shown that intense fan identification with a team impacts behavioural changes when people belong to an exclusive group andthis can lead to physiological responses when a favoured team wins or loses, including violent and destructive behaviours (e.g., riots) [3]. Furthermore, the massive audiences accompanying the Olympic and Paralympic games have moved the event from its intended goal of international peace to a highly politicized environment that includes boycotts, propaganda, and protests [4]. However, despite this, or because of this influence, sports have been identified as an important contributor to the United Nation’s 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Note: within the article, the term Olympics encompasses both the Olympic and Paralympic games.

From a financial perspective, the revenue of the global sports industry is equal to approximately 1% of global GDP [5]. Although revenue declined due to COVID-19 and the subsequent lockdown and travel restriction orders, sports revenues are projected to grow faster than GDP in the future [6]. Spectator sport’s revenue in the United States alone (comprising media rights 28%, ticket sales 27%, sponsorship 24%, and merchandising 20% in 2018) is expected to increase from USD 50 billion in 2010 to USD 83 billion by 2023 [7]. Monies generated by spectator sports benefit not only athletes and sports organizations but also businesses and local economies. For example, the 2021 Super Bowl generated almost USD 100 million in media value for its top five sponsors [8].

From a societal perspective, the United Nations have identified sports as a significant contributor to the advancement of the 17 SDGs: “We recognize the growing contribution of sport to the realization of development and peace in its promotion of tolerance and respect and the contributions it makes to the empowerment of women and young people, individuals and communities as well as to health, education and social inclusion objectives [9]”, referring to Appendix A Exhibit A Sport Contribution to SDG 1, which illustrates that sport is an essential enabler of sustainable development and providing detailed information on how sport contributes to one of the 17 SDGs.

On the other hand, the competitive drive to win and the financial gains attained can supersede respect for the rules of the game and the perceived spirit of fair play. Ethical challenges are widespread and can be found even at the elite world sports level. Examples include Major League Baseball’s (MLB) Houston Astros found guilty early in 2020 of an elaborate cheating scheme [10], the National Football League’s (NFL) New England Patriots “Spygate” and “Deflategate” scandals involving illegal video recordings of competing teams and deflation of game balls, respectively [11], and bullying and racism in the National Hockey League (NHL) [12], among many other incidents.

While the above infractions represent a clear set of wrong versus right decisions and, in most cases, illegal acts, many other unethical behaviours exhibited by the public, athletes, sport’s governing bodies, corporations, and governments in the past go unnoticed or are even accepted in today’s environment. For those shocked by the consensus in acceptance of some of these behaviours, the error may lie in the assumption that laws have a moral foundation. That is, when society deems something morally wrong, laws are passed to correct it. However, morality is a matter of interpretation [13]. Codes of moral and ethical conduct can be mutually exclusive from the law. As such, with situational context, moral conduct may indeed violate the law, moving right versus wrong dilemmas to a self-interpreted decision space of right versus right choices, or creating an ethical dilemma. In this space, acting outside of the law or weighing the law as less consequential may occur with the decision choice.

The significant financial implications, the deeply-rooted instincts to compete and succeed, the power of sport to unite a community, and the varying ethical interpretations of right and wrong immediately place many decisions surrounding sport in ethical dilemma territory. Additionally, the substantial and variable consequences from these decisions can either support or contradict sport’s ability to positively contribute to the UN’s 17 SDGs. The ability for sport to lean toward achieving these SDGs requires financial and legal judgments and excellent moral evaluations. Arguably, moral judgments, often the most difficult, should be prioritized. Given the many ethical dilemmas faced in sports today, there is an essential need for responsible leadership that includes excellent ethical decision-making skills. To this end, this paper first presents the contradicting ethical theories that place an action in the ethical dilemma space. Secondly, a guided step-by-step approach for resolving ethical dilemmas adapted from ethicist Rushworth M. Kidder [14] is introduced. This framework is then applied to a current ethical dilemma surrounding the 2022 Beijing Winter Olympic Games to illustrate how careful analysis may help with better thinking and outcomes. This outline is followed by a conclusion.

2. Defining Ethical Dilemmas

The ethical decision-making process is influenced in some part by an individual’s perception of the situation-specific issue, i.e., the moral intensity of the situation. In their review, Lehnert et al. [15], found research that directly relates moral intensity to fear of consequences [16], guilt [17], and other outcomes (e.g., whistleblowing). An additional factor influencing moral intensity is the psychological or emotional closeness the decision maker feels for those affected by the decision [15]. The social consensus, or the extent that members of a society agree that an act is good or bad, also affects the moral intensity of the situation.

In addition to the moral intensity of the situation, two differing philosophical theories—deontological and teleological—might help us arrive at different decision outcomes. Deontological theories state that ethical dilemmas should be resolved by applying the universal standard or code of justice that everyone must follow. Kantian and Rawlsian ethics are examples of deontological ethical theories. Although this perspective appears black and white, the “universal standards or codes of justice” will vary depending on societal norms dictated by timing, geography, and predominant social and cultural influences. As such, the rules applied can differ from country to country, across time and from person to person,

On the other hand, teleological approaches require that ethical decisions result in the most significant benefit for the largest number of people. This theory requires us to maximize the well-being of all people on the planet. There should be no constraint placed on maximizing this well-being, and teleological approaches require impartial benevolence on the part of the decision maker [18].

Consider Robin Hood, who robbed the rich for the benefit of the poor [19]. Would you turn him in to the authorities? If you chose to do so, the money would be returned to those who need it less. From a deontological perspective, you would turn him in; the rule about stealing is apparent. However, from a teleological perspective, you could provide a compelling moral case that helping the needy is more important than returning money back to the wealthy. Now, the ethical lens used could vary depending on your stakes in the situation (moral intensity)—one may respond differently depending on whether they were the person who was robbed or the beneficiary of the stolen funds.

To complicate matters further, these two broad-based theories (deontology and teleology) have several variations of ethical thought. For example, the traditional teleological objectivist uses objective, independent measures of right and wrong, i.e., choosing actions that achieve the greater good, contained/conducted within a moral framework. Utilitarians and egoists, however, may use more subjective, internal tests of right and wrong [20]. For example, utilitarianism, a form of consequentialism, requires a cost-benefit analysis to determine who will be hurt and who will benefit.

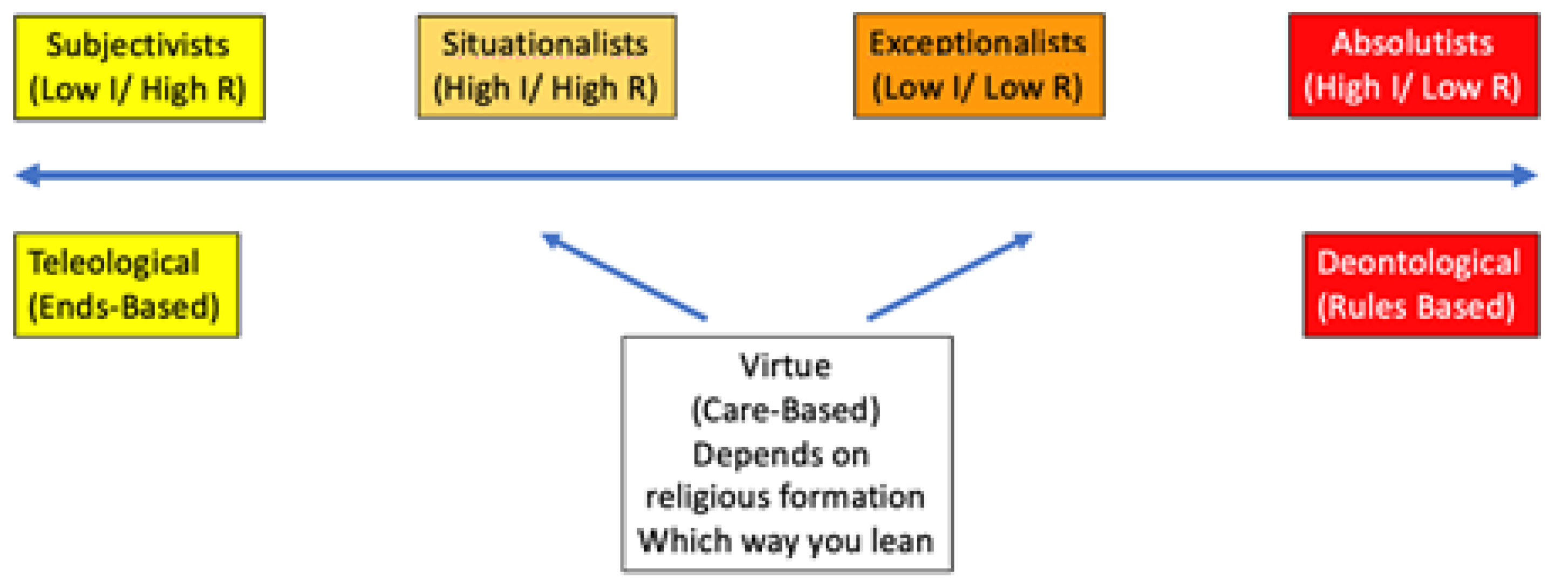

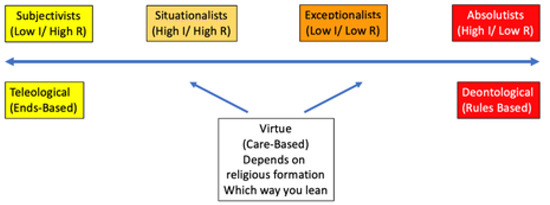

Kidder [14] describes another principle from the traditions of moral philosophy: care-based thinking. That is, putting love for others first as the guiding principle for both action taken and consequences weighed, stating that this principle can potentially stand in the middle of the two theories (deontological and teleological) and lean in different directions depending on the religious/moral formation of the individual.

Deontology and teleology are similar to the concepts introduced by Forsyth [21] of relativism and idealism. Forsyth demonstrates the orthogonality of idealistic and relativistic variables and introduces four dimensions of ethical orientation based on the degree of idealism and relativism in subject responses (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Four ethical orientations based on Forsythe’s Ethics Position Questionnaire (EPQ) scale.

Figure 1 positions Forsyth’s four ethical orientations onto the ethical theory continuum defined by deontological and teleological theories to better understand their theoretical intersections.

Figure 1.

Positions Subjectivists, Situationalists, Expectionalists, Absolutists, Deontological, Teleological and Care-based ethical theories on an ethical orientation continuum.

Depending on the situation, the stakeholders and ethical lens employed, decisions will vary.

3. A Pressing Dilemma: The 2022 Beijing Olympics

The 2022 winter games scheduled to take place in Beijing is a pandora’s box of ethical dilemmas, with some front and centre and others ready to rear their heads at unsuspecting moments. Decisions in this space are not easy and difficult to navigate. Sound ethical decision making requires rational minds that can think quickly. Although we do not know the full extent of what caused these dilemmas in the first place or the direct consequences for the actions taken, this does not imply that we cannot have a logical approach to ethical decision making. Ethicist Rushworth M. Kidder offers a guided step-by-step approach to resolving ethical dilemmas in his book, entitled How Good People Make Tough Choices [14]. We chose to apply this approach to the current ethical dilemma faced by many actors given the International Olympic Committee’s (IOC) choice to host the 2022 games in China. In this article, we demonstrate the framework in action and offer recommendations for what decisions may be made to solve this dilemma.

3.1. The Nine-Check Points of Ethical Decision-Making

- Step 1.

- To recognize that this is an ethical dilemma with evidence on both sides of the argument, suggesting that each decision may be an ethical one;

- Step 2.

- Determine the actors involved. Who is responsible and accountable for the decision? Who will the decision impact?—In this case, athletes, vulnerable populations, sports organizations, countries, sponsors, media, audiences, etc.;

- Step 3.

- Identify the relevant facts. What are the relevant facts? Why did it happen and what has been done?;

- Step 4.

- Test for right versus wrong issues. For example, do the actions taken involve any wrongdoing?;

- Step 5.

- Test right versus right paradigms. If the issue and actions taken pass the right versus wrong tests, what type of dilemma are we facing? The purpose of this step is to ensure that it is a true dilemma with two core values in contradiction with each other;

- Step 6.

- Apply the various ethical approaches, both deontological and teleological, among others. What solutions emerge given the ethical lens applied?;

- Step 7.

- Investigate the “trilemma option”. Kidder suggests that this step can occur at any time throughout the decision-making process. Is there a completely different path that can help resolve this issue? [14];

- Step 8.

- Arrive at a decision and develop a risk mitigation plan to anticipate and address consequences;

- Step 9.

- After the decision has been implemented, track the outcomes, and apply this lesson moving forward.

3.2. Current Ethical Dilemma: The 2022 Bejing Winter Olympic Games

3.2.1. Step 1—Is There an Ethical Issue That Potentially Needs Resolution?

Beijing, China, was selected by the IOC to host the 2022 Winter Olympic games. Immediately following this announcement, over 180 organizations called governments to boycott the games over China’s alleged human rights violations. Although China is not listed as the worst abuser of human rights ranking lower than Burma, Equatorial Guinea, Eritrea, Libya, North Korea, and Sudan [22], Human Rights Watch and Amnesty International have described the Chinese government’s human rights violations as widespread. These two organizations highlighted the systematic repression of minority groups. China’s response to these reports has been that these violations are justified as “anti-separatism” or “counter-terrorism”, particularly in the regions of Xinjiang and Tibet. More recently, the government has received international condemnation for what has been described as efforts to erase the unique identity of Uyghurs and other Turkic Muslims [23]. Chinese President Xi Jinping stressed, “that the Beijing Winter Olympics and Paralympics are the feast of all countries and a stage of fair competition for all athletes” [24]. IOC President Thomas Bach said, “the IOC opposes politicizing the Olympic movement, stands ready to continue close cooperation with China and fully supports China in hosting the Winter Olympics and Paralympics in Beijing as scheduled” [24].

Article 1 of the United Nations Declaration of Human Rights states, “All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights” [25]. Given that these rights are foundational to freedom, justice, and peace globally, would allowing China to host the Olympics ignore the issues at hand and condone a country for its bad behaviour? Is China’s desire to hold the Olympic games a clear case of sportswashing?—a nation’s attempt to improve its reputation by directing our attention away from its poor human rights record? If so, choosing China to host the games and attending the event may place many actors at the centre of an ethical dilemma.

3.2.2. Step 2—Determine the Actors Involved. Who Is Affected by the Issue? Who Is Responsible and Accountable for Solving the Dilemma?

The actors include the oppressed, IOC, the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), countries participating in the Olympic games, human rights defenders (HRDs) the athletes, and sponsors.

The Oppressed

Since 2014, under the CCP’s rule, there have been allegedly over one million Muslims (the majority of them Uyghurs) held in secret internment camps with no access to legal representation. This represents the largest detention of ethnic and religious minorities since the Holocaust of WW2 [26].

Tibetans also face restrictions of freedom of religion, belief, and association. Allegedly, they have been arbitrarily arrested, tortured, and subjected to forced abortion and sterilization [27]. Tibet’s media is controlled by the CCP, making it difficult to determine the scope of these human rights abuses accurately.

The CCP has revoked the rights of many Hong Kong citizens, which were previously protected by the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights and the Sino-British Joint Declaration which include “freedoms of speech, the press and assembly” [28].

The IOC

President Thomas Bach of the IOC claims that the games are not politicized, saying, “We are not a super-world government where the IOC could solve or even address issues for which not the U.N. security council, no G7, no G20 has solutions” [29]. However, while the IOC claims that the Olympics are a nonpolitical event, history informs us this is not the case [30]. Many people do not forget the impact of the 1972 Munich Olympics, when 11 Israeli athletes were taken hostage and killed in protest of detained Palestinian prisoners in Israel [31]. Furthermore, the IOC continues to hold observer status at the United Nations and has officially announced its attempts and successes in helping to reunite the two Koreas at the 2018 Winter Olympics in PyeongChang, South Korea [32].

The IOC has stepped away from the boycott question, stating, “The Games are not Chinese Games, the Games are the IOC Games. Therefore, you are not boycotting China; you are boycotting the IOC” [29].

The Chinese Communist Party

In support of the IOC decision, China announced that any boycott by another country of the pending Olympic games would be politically motivated. Chinese Foreign minister spokesperson Zhao Lijian announced that “China rejects the politicization of sports and opposes using human rights issues to interfere in other countries’ internal affairs,” and stated that a boycott “is doomed to failure” [29].

Participating Countries (HRDs)

All countries have the duty of promoting and protecting human rights under international law and the United Nations Charter [33]. Human Rights Defenders (HRDs) can also be any person or group of people who take action to protect human rights peacefully by calling attention to violations or abuses by governments, businesses, individuals, or groups [34].

The United Nations have also identified the role of sports as a human rights defender (HRD), stating, “Sport can be used as a platform to speak out for the realization of human rights, including the right to an adequate standard of living, the right to social security and the equal rights of women in economic life, which have direct impacts on the goal to end poverty. Sport can also be used as a platform to campaign for socio-economic progress and raise funds to alleviate poverty” [35].

Countries such as Canada have clear guidelines for supporting and protecting human rights. These include The Universal Declaration of Human Rights, The Core Human Rights Instruments, and The Declaration on Human Rights Defenders [34].

Dorjee Tseten, executive director at Students for a Free Tibet, warns, “If we don’t stand now, it will be impossible to make China accountable. When we call for a boycott, it has to be a coordinated boycott led by democratic countries who are now accepting that the genocide is happening” [36].

The Athletes

The athletes undoubtedly would be disappointed with the boycott (much like the athletes faced when COVID-19 postponed the 2020 Summer Games [37]). Several athletes spoke out for and against the 1980 Olympic game boycott [38]. Dean Matthews stated, “When I first heard about it, I was pretty reactionary: ‘Why me?’ But I thought about it, and when I was on a run the next day, I decided that if everybody feels that’s the right thing to do, we should do it”. Garry Bjorklund stated, “I don’t like having my livelihood wasted”. Runner Carl Hatfield stated, “the Olympics, is one of the few events that’s conflict-free. It’s a step in a positive direction. Take away that step and you’re further down that continuum that leads to war”. Perhaps the wisest answer came from Margaret Gross in an interview from Runner’s World, “I think it should be up to the individual” [39]. However, an athlete who has trained for several years leading up to the Olympics, unlike the 19 IOC international board members, has no input or influence over where those games eventually occur. Although an athlete may feel accountable and take action to highlight a political infraction on behalf of the host country, history would suggest that without other supporters, this action has little impact, except on the athlete themselves. For example, during the 1968 Olympics held in Mexico, American athletes Tommie Smith and John Carlos were expelled from the games for giving the “black power” salute from the winner’s podium [30]. Furthermore, athletes who speak out could risk losing their sponsorships or receive backlash from the CCP once they are on Chinese soil.

The Sponsors

Sponsors of the Olympics pay over USD 5 billion dollarso the IOC: Funding information posted on the IOC’s website shows that over 90% of the IOC’s funding of 5.7 billion USD comes from broadcast rights (73%) and top program marketing rights (18%) [40]. Additionally, these same sponsors and others pay to have their brands showcased by the athletes. Global brands gain high exposure and a good return on investment at the Olympics due to the massive global audience that watch for the duration of the event. Although sponsors want the Olympic connection, they could risk damaging their reputation because of China’s reported human rights issues.

Protests by athletes put sponsorship opportunities at risk and increase personal safety concerns on Chinese soil. Individual countries that recognize international laws and have signed the Universal Declaration of Human Rights charter are both, directly and indirectly, responsible as protectors of human rights. Unfortunately, athletes are at the centre of the ‘boycott’ debate, offering their livelihoods up as levers in hope of changes to host country policies or to make a statement about the boycotting country’s stance on human rights issues. Furthermore, China’s ability to flex its economic muscle and penalize countries who depend on exports to or imports from China adds an extra dimension to the boycott decision. The IOC, as a sports organization that chooses the host country, certainly has some responsibility. However, corporate sponsors have the most power over the IOC and potentially have the economic weight to direct a different host country outcome. They are also the least exposed to Chinese retaliation. Sadly though, the country where the sponsoring companies reside may be the actual recipients of the CCP’s wrath. This is a great dilemma.

3.2.3. Step 3—Identify the Relevant Facts

Hosting the Summer or Winter Olympic games brings many of the world’s greatest athletes, the largest audience viewership, and copious amounts of media. It is an opportunity for a country to be centre stage, yet so few countries are willing to submit a bid, and for many countries that do, their citizens eventually vote for the country to withdraw. The dwindling list of host candidates is frequently accredited to the economic costs associated with hosting the event. The 1976 Summer Olympics in Montreal illustrates the fiscal risks associated with hosting the games. The price was in the billions, well above the projected cost of CAD 124 million. The city’s taxpayers were held accountable for more than CAD 1.5 billion in debt, which took close to 30 years to settle [41]. Two significant studies (Table 2) examined the magnitude of the cost over-run experienced by host cities around the world. Flyvbjerg, Budzier, and Lunn [42] examined cost over-runs at the Olympics from 1960–2016. Preub, Andreff, and Weitzmann [43] examined cost over-runs from 2000–2019. By using different methodologies, both studies reported substantial cost over-runs since 2001. In one study, local organizing committees [43] either broke even or turned a profit when subsidies were included. However, both reported that they were uncertain whether hosting the Olympics is beneficial to the overall host country’s economy. Several economists have noted little impact on GDP, employment, or income for the chosen city [44,45].

Table 2.

Both studies report severe cost over-runs at the Olympics since 2000.

The process and expectations for submitting a bid to the IOC can also be blamed for many countries either refusing to bid or dropping out. Before being considered as a host, cities must invest millions of dollars. “The cost of planning, hiring consultants, organizing events, and the necessary travel consistently falls between $50 million and $100 million. Tokyo spent as much as $150 million on its failed 2016 bid, and about half that much for its successful 2020 bid, while Toronto decided it could not afford the $60 million it would have needed for a 2024 bid” [41,45].

The IOC announced on November 2013 that the following six cities had applied to host the 2022 winter games: Krakow, Poland; Lviv, Ukraine; Stockholm, Sweden; Oslo, Norway; Almaty, Kazakhstan and Beijing, China. By 14 October 2014, four countries had withdrawn from the running, leaving two remaining cities: Almaty and Beijing. Both remaining countries are accused of violating human rights laws. Beijing won by 4 votes.

The decision to boycott the games is a difficult one. There is a long history of boycotts spanning the length of the modern Olympic movement [30]. For example, Ireland and Spain boycotted the Berlin games in 1936. In 1956, Egypt, Iraq, Cambodia, and Lebanon boycotted the Melbourne Olympics to protest the Suez crisis. Additionally, the Netherlands, Sweden and Spain boycotted these same Olympics due to the Soviet Union’s invasion of Hungary. The People’s Republic of China was also a no-show in response to the inclusion of Taiwan. The IOC first banned South Africa from the 1964 Olympics in Tokyo, and that ban was upheld until 1992 in response to the oppressive apartheid regime. The 1980 Olympic Games in Moscow saw several high-profile nations (e.g., United States, Canada) boycott the games due to the Soviet Union’s invasion of Afghanistan. Although each country’s Olympic Committee Charter requires the committee to “resist all pressures of any kind whatsoever, whether of a political, religious or economic nature,” for the 1980 games, a total of 62 countries, including the U.S., West Germany and Japan, refused to attend. However, boycotts have not successfully changed host country government policies historically [39]. In 1976, 26 African countries boycotted Montreal in response to New Zealand’s participation, claiming racial injustice issues surrounding a previous event held in segregated Africa; this may have been a call to have the host country bar New Zealand from the games. However, several other countries would need to be barred on these same grounds. This boycott, in hindsight, represented a statement about the African countries’ position on racial injustice rather than a call to action. In 1980, Russia did not consider pulling out of Afghanistan and went on to win 195 gold medals [46]. IOC member Dick Pound agreed that a boycott of the 2022 Beijing Games would be “a gesture that we know will have no impact whatsoever” [47]. Outside of the Olympic games, global power governments’ responses to human rights violations are somewhat disappointing. The lack of accountability by countries sends a message that the behaviour is acceptable and that we have a general disregard for human life beyond our borders [22], or that human rights concerns may not trump economic and geopolitical interests. In 2020, China had the second-largest economy worldwide, with a nominal GDP of $14.3 trillion, growing at 6.1%, representing 16.3% of the global economy. They have the largest purchasing power worldwide (PPP) and as a net exporter [48] wield a tremendous amount of influence over other economies [49,50,51,52]. For example, China is Canada’s second-largest national two-way trade partner after the U.S. China is also Canada’s second-largest export market [53].

However, a country such as Canada may wish to consider its diverse population in its decision making [54]. Canada represents several ethnicities whose direct relations are impacted by human rights violations in various countries worldwide. Approximately 70% of the population surveyed in Canada stated that their roots are other than Canadian [55].

China’s economic position gives them great power to penalize any country that either blocks their Olympic bids or chooses to boycott the 2022 Beijing Winter Olympic Games or future games. Governments face potential retaliation and unrest in their own countries for attending; however, they also have their trained athletes’ livelihoods to consider.

3.2.4. Step 4—Test Right and Wrong Consequences for Possible Outcomes

Kidder [14] identified five right and wrong tests that can be applied to any ethical dilemma to determine whether the issue goes beyond the different ethical orientations of the actors to include actual wrongdoings. We can use these tests for countries that have considered attending the Olympics and the IOC’s selection of a host country for the Olympics in violation of human rights laws.

The Legal Test: It is not illegal to attend the Olympics in China or for the IOC to select a host country that violates human rights laws. Governments, the IOC organization, competing athletes, and those in supporting roles do not face criminal charges or fines for participating in the Olympic games hosted by countries that violate these laws.

The Regulation Test: This is a grey area for many countries. A perceived contradiction of regulations established to avoid human rights violations has motivated many countries to boycott the Olympics in the past. The IOC implicitly admitted prior failings of the regulation test, specifically when introducing the revised Host Country Contract in 2017 [56] that now included elements of the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human rights (UNGP). This revised contract was created by a “coalition of leading human rights organizations, sports groups, and trade unions, including UNI World Athletes, FIFPro, the world football players’ union, Football Supporters Europe, Human Rights Watch, the International Trade Union Confederation, UNI Global Union, Terre des Hommes, Transparency International Germany, Amnesty International Netherlands, and Amnesty International United Kingdom.” [56]. The contract explicitly references the UNGP, requiring all host countries to sign an agreement that holds the host accountable to human rights responsibilities and anticorruption standards [56] while hosting the Olympics. The revised contract enables the IOC to pass the regulation test, and for many countries deciding to attend, this may be enough to pass their own standard for the regulation test.

The Front-page newspaper test: Although newspapers are no longer the avant-garde method for receiving news, the test applies to any media source. What is the fallout from either the IOC or a specific country being chastised in the news for choosing a host country that violates human rights treaties and charters or sends their athletes to these same countries? This has already happened. On 6 April 2021, CNBC reported analysts from the political risk consultancy Eurasia Group concluding that, “Western governments and firms face mounting pressure from human rights advocates and political critics of China to boycott the Beijing 2022 Winter Olympics,” and “If a company does not boycott the Games, it risks reputational damage with Western consumers…” [57]. In Canada, CBC reported on 17 May 2020, “Groups call for a full boycott of 2022 Beijing Olympics” [58]. On 9 September 2020, the CBS News headline read, “Human rights groups urge IOC to move the 2022 Olympics out of China” [59]. Although these news stories shed poor light on countries sending athletes and the IOC, news stories published in response are equally damaging. “China will punish countries that boycott the games with political sanctions and commercial retaliation, but with much greater severity in the athletic boycott scenario,’ [Eurasia Group analysts] said in a report published Thursday” [57]. When interviewed by the media, Canadian athlete Matt Dunstone, who is scheduled to compete in 2022, said, “I would have a very difficult time either boycotting them myself or being on board with that decision. The Olympics is a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity. People work 4, 8, 12 years putting everything they’ve got into it, their life on hold, to go. If the Olympics were tomorrow and I was told we were Team Canada, I would be hopping on that plane instantly” [60]. Neither the IOC nor the countries sending athletes pass the newspaper test. Regardless of the side you choose—boycott or not—the media does not provide a good story. The results of newspaper tests are inconclusive.

The Stench Test: Does the chosen action stink? As we move through life, we often face inner turmoil; there is tension between our inner and outer self. We may have taken a direction that does not align with our core values, and it does not feel right. For the IOC, who embody Olympism, as stated on their website, the idea of choosing a country to host the Olympics that violates human rights may fail this test when held up against those values.

“Olympism is a philosophy of life, exalting and combining in a balanced whole the qualities of body, will and mind. Blending sport with culture and education, Olympism seeks to create a way of life based on the joy of effort, the educational value of a good example, social responsibility and respect for universal fundamental ethical principles” [61].

Similarly, for countries such as Canada whose “diverse, multi-cultural democracy enjoys a global reputation as a defender of human rights and has a strong record on core civil and political rights protections that are guaranteed by the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms” [62], sending athletes or attending the Olympics in China may conflict with the country’s stance and may also fail the stench test.

The Mom Test: This is a relatively simple test, but with no easy answer. It asks us to consider what mom would say. Of course, moms would have many different perspectives, depending on which side of the argument they settle on. If I am the mother of the athlete, or the mother of a country leader who is sending athletes to China, or the mother of a child that received a job in China at the games, or the mother whose child is the victim of human rights violation, the response would mostly likely be different. The inability to develop a unifying answer from all moms would further confirm the decision space peculiar to an ethical dilemma. Contrast this to a discussion with moms on whether drinking and driving is bad. Whether you are the mother of the child caught drinking and driving or the mother whose child was injured by a drunk driver, most would agree that drinking and driving is bad.

When solving tough ethical dilemmas, moms encourage their children to take inspiration from moral exemplars. ”Seek out good role models and break free of bad ones to help navigate complex moral terrain” [63]. The IOC claims to be just that, “the educational value of a good example” [64]. Mom might say, “If countries can bar other countries from attending the Olympics, and countries can choose to boycott the Olympics, why can’t the IOC use better ethical decision-making criteria when deciding where to host the games to minimize political agendas and allow the games to proceed as intended?”.

For the most part, we have passed the right versus wrong tests and therefore advance to Step 5, where we sharpen our focus on what type of ethical dilemma we are facing.

3.2.5. Step 5—The Right versus Right Dilemma

Kidder highlights how right versus right dilemmas are “at the heart of our toughest choices” [14]. He further identifies four right versus right paradigms, truth versus loyalty, short-term versus long-term, individual versus community, and justice versus mercy. Certainly, it is right to protect the citizens of the world, but at the same time, it is right to protect the interests of one’s own country. Boycotting the games while making a statement about the political injustices in China may jeopardize the well-being of one’s community economically (e.g., through Chinese retaliation) and that of the athletes who have been trained for this opportunity their entire lives. Recognizing that the decision falls within one or more of the four aforementioned paradigms helps establish the issue as a true ethical dilemma, where two sets of core values are in direct opposition to each other. In this case, athletes may be facing an individual versus community dilemma, participating countries may face a truth versus loyalty dilemma, the IOC may be facing a short-term versus long-term dilemma, and, although a stretch, China may perceive the issue as a justice versus mercy dilemma.

3.2.6. Step 6—Apply the Various Ethical Orientations

The deontological approach informs one to “follow your highest sense of principle” (rules-based) [14]. The teleological approach prescribes one to ‘do what’s best for the greatest number of people’ [14], and the care-base thinking approach advises one to ‘do what you want others to do to you’ [14].

Therefore, applying the deontological orientation, the action to minimize crimes against humanity is considered the moral good because the act in itself is right, regardless of the consequences for human welfare. There are rules, laws, and regulations that must be followed. Participating countries in the games, governments, athletes, and sponsors should boycott the Olympics as China is violating established international norms and laws. Considering this view, the IOC should not have accepted a bid from China nor in 2008 due to similar humanitarian concerns over Tibet [65]. Although this ethical lens aids decision making, not understanding or considering the consequences of these actions for others would be short-sighted.

A teleologic approach would argue that we should judge whether an act is good or bad by weighing its consequences. There are compelling moral reasons that may arise for supporting the Olympics in China, and these reasons vary depending on the actor.

For example, from the participating countries’ point of view:

- 1.

- There has been great political unrest and divide among countries globally, magnified by COVID-19. At the World Economic Forum annual meeting (January 2021), the theme was Creating a Shared Future in a Fractured World—an assessment of the state of the world and an important call to action. The Olympics provides an important connection that brings people together, both across and within countries. The Olympic games are intended to cross political divides and could broker better relationships between China and other nations;

- 2.

- The economic backlash imposed by China for countries that publicly denounce China for violating human rights laws through boycotts could have social welfare impacts on the boycotting nation;

- 3.

- Athletes have trained all their lives in preparation for the Olympics. The competition is not political, and by participating, the athletes demonstrate good sportsmanship between nations that are otherwise politically divided;

- 4.

- Boycotting has never been successful in the past;

In addition to the reasons above the IOC would add:

- 5.

- The cost to host an Olympic game for many countries is cost-prohibitive. Citizens of democratic nations refuse to pay the cost. China in 2008 has proven (through their self-reported figures) that they had the least budget overage of any other nation since 2000 (see Table 2) At the time of the IOC choice of a host for the 2022 Beijing Games, there were only two countries to choose from. Both countries were in violation of human rights laws; Sponsors of the Olympics pay money to the IOC;

- 6.

- Cancelling or selecting a less economically sound location has economic consequences for the IOC;

- 7.

- China has already proven that they can host a successful game as seen in 2008;

Sponsors would add:

- 8.

- The Olympic games are a significant opportunity for brand awareness and building brand equity to massive international audiences;

- 9.

- There is a risk of reputational damage due to spillover from human rights violations media coverage associated with these Olympic games;

Human rights defenders would add:

- 10.

- Minorities in China are oppressed and suffering. We must uphold their values and do whatever we can to defend human rights.

- 11.

- China’s bid for the Olympics may be a form of “sportswashing”, an attempt to build a country’s reputation and take attention away from unethical behaviours. Attending the Olympics in China is condoning the CCP’s human rights violations.

- 12.

- This is about human suffering, not economic loss. China should not be rewarded for throwing around its economic muscle. Countries should stand up collectively to this;

Sport organizing committees and federations would add:

- 13.

- Advancement of the 17 UN SDGs. “Sport can be used as a platform to speak out for the realization of human rights, including the right to an adequate standard of living, the right to social security and the equal rights of women in economic life, which directly impact the goal to end poverty. Sport can also be used as a platform to campaign for socio-economic progress and raise funds to alleviate poverty” [9].

A major challenge with the teleological approach is that it can be very subjective- depending on who is making the decisions. The values associated with each choice can vary. For example, the IOC could select Beijing as the host city because in the past, this city came closest to reaching their budget targets for hosting the games (see Table 2). They could also rationalize that Beijing was the lesser of the two evils in terms of human rights violations. They could state that the Olympics is not political and instead crosses political divides. They could also rationalize that the Beijing choice was the most lucrative deal for the IOC itself. Due to the subjective nature of this approach, it is here where the potential for ethical lapses is at its greatest [20].

Care-based ethics, i.e., “do unto others as you would have them do unto you”, might be the most appropriate ethical lens to apply to this current dilemma and falls between the deontological and teleological orientations.

3.2.7. Step 7—The Trilemma (Is There Another Way Out?)

Deciding whether to attend the games, boycott the Olympics, or retract the host status from China is incredibly challenging with far-reaching and severe consequences for many stakeholders. Through this process, is it possible to see a third way out of this dilemma? Two actors move to the forefront that have political weight with the least amount of consequences to make a difference using care-based ethics: the IOC and the sponsors. As Dick Pound emphasized, “This is NOT the Chinese Olympic Games this is the IOC Olympic Games” [29].

The 2022 Olympics may be an opportunity for the IOC to embrace its “Olympism” and its “philosophy of life—seeking to create a way of life based on the joy of effort, the educational value of a good example, social responsibility and respect for universal fundamental ethical principles.” [59]. For example, given this statement, an Olympian can leverage the power of sport to achieve the UN SDG Goal 1 toward ending poverty in all forms everywhere. Host countries can be selected based on economic need, benefiting most from the GDP growth gained from hosting; this would require a completely different host country selection criteria, potentially where participating countries contribute financially (needs-based) to the host country. Sponsors should be wary about how they choose to showcase their wares at the Beijing Olympics, as they could be accused of associating with and supporting a political party believed by the consensus to be violating human right laws. As ‘Olympian’ sponsors, the current and future call would be to invest in deserving communities, i.e., education and local sports programs, HRD organizations and eventually investments in sustainable infrastructure for the future host country, based on this newly proposed IOC’s enlightened host country selection criteria.

3.2.8. Step 8—Make a Decision

Kidder challenges us to be bold and decide, highlighting that this step is missed altogether in many cases. People spend an inordinate amount of time analyzing a dilemma but never arrive at a conclusion. In order to avoid falling into this trap, we offer recommendations for the short- and long-terms.

In the short-term, we recommend that the IOC uphold their contract with Beijing as the host country for the 2022 games. The integrity of the organization and the potential backlash from China for cancelling the games would have serious consequences. Sponsors should find more effective ways to advertise during these games to lift those who are marginalized and oppressed. Countries and their athletes should decide for themselves to boycott or not. We further recommend that leading up to the games, the IOC should use their seat at the UN council in conjunction with other UN members to develop a host country selection process and criteria that allows the games and sports to uphold its Olympian values and to continue pushing forward the UN 17 SDGs and the 2030 agenda. By choosing host countries that consistently violate human rights laws, the IOC asks countries who send their athletes to turn a blind eye, thus condoning their infractions and allowing these countries to profit and gain notoriety on a world stage for reasons other than their crimes against humanity.

In the long-term, we recommend the IOC conduct a third-party audit of their current structure and decision-making processes for publication, identifying areas that require a change or additional governance to uphold its promise to society as a carrier of the “Olympian” flag.

3.2.9. Step 9—Look Back and Reflect

After any execution, it is the responsibility of the IOC, sponsors and the entire Olympic community to look back, reflect and revise.

4. Discussion and Conclusions

As noted in the Introduction, the sports market wields tremendous influence both economically and socially over our societies worldwide; this influence has the potential to make this world a better place, helping to accomplish the UN 17 SDGs and achieve the 2030 agenda. If the IOC, in conjunction with other UN members, were to develop a host country selection process and criteria, it would help accomplish these goals and uphold its Olympic values. As Thomas Bach, the IOC president, stated, “sport is not just physical activity; it promotes health and helps prevent, or even cure, the diseases of modern civilization. It also is an educational tool which fosters cognitive development; teaches social behaviour; and helps to integrate communities” [66].

Hosting the Olympic Games is also viewed as a rite of passage for emerging economies, particularly with Brazil (2016), Russia (2014), and China (2008) all hosting the games in recent years [66]. However, the economic opportunities offered by sports to athletes, countries, corporations, and sports organizations are immense and can lead to significant ethical dilemmas and, depending on the actions taken, could have severe and devastating consequences. The world takes notice of both the positive and negative aspects. Gorge Mariscal, the chief investment officer for emerging markets at UBS claims, “Countries host them largely as a very costly publicity exercise… it’s a double-edged sword” [67]. Factors such as long-term GDP growth, short-term improvement of political rights, experience in hosting world championships, and rotation among countries have identified factors that influence the IOC’s decision [68]. Currently, out of 200 National Olympic Committees (NOCs) eligible to bid for the 2020 Olympic Games, only a handful have bid [69]. The research also indicates that countries characterized by nondemocratic regimes with restrictive political and civil rights more often bid on the games [69]. Thus, reviewing IOC procedures with the objective of increasing the number of developing countries selected to host the Games would in many ways push forward the UN SDGs. Conversely, this would also increase the likelihood of other human rights dilemmas similar to those analyzed in this paper. The costs of hosting the games and thus the limited number of cities applying to host should be addressed in future research.

During the writing of this paper, the Tokyo Olympics were about to begin amongst a global pandemic. While the host nation and the IOC came together in 2020 to agree on postponing the games, no such decision was made in 2021 as the pandemic raged on. Mike Wise provides a different approach to the dilemma of postponing the games again in his essay in the Washington Post:

“The proper thing would have been to move everything back an additional year … But the IOC, network heads and Japanese officials are focused on income. And when they weighed those billions against the possibility of residents and athletes contracting COVID and much of the host country wishing they’d pick real-life ethics over professional gain, humanity never stood a chance.”.[70]

As we noted, the financial, economic and political power associated with the global sport industry has continued to increase in modern times. The increasingly complex nature of the sports industry also demonstrates the essential need for responsible leadership that includes an educated, ethical approach to resolving complex problems. Therefore, in this paper we presented a guided step-by-step approach to resolve ethical dilemmas. We applied this process to the current ethical dilemma surrounding the 2022 Beijing Winter Olympic and Paralympic Games to illustrate how careful analysis may help with the best thought process and, ultimately, the potential for improved outcomes for future hosting decisions. This paper has provided a compelling reason why there are ethical dilemmas in the sports industry, and the need for ethical leadership within the industry.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, K.R., L.H., L.F. and A.P.; methodology, K.R.; validation, L.H., L.F. and A.P.; formal analysis, K.R.; investigation, L.H., L.F. and A.P.; writing—original draft preparation, K.R., L.H., L.F. and A.P.; writing—review and editing, K.R., L.H., L.F. and A.P.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A. Exhibit A: Sport Contribution to SDG 1

Goal 1: End Poverty in all forms everywhere [56] (In particular, targets: 1.1, 1.2, 1.a)

- Sport values such as fairness and respect can serve as examples for an economic system that builds on fair competition and supports an equal sharing of resources. Reinforcing competencies and values such as teamwork, cooperation, fair play and goal-setting, sport can teach and practice transferable employment skills which can support employment readiness, productivity and income-generating activities.

- Sport can be used as a platform to speak out for the realization of human rights, including the right to an adequate standard of living, the right to social security and the equal rights of women in economic life, which directly impact the goal to end poverty. Sport can also be used as a platform to campaign for socio-economic progress and raise funds to alleviate poverty.

- Sport initiatives can raise and generate funds for poverty programmes and assist in raising awareness and facilitating the mobilization of needed resources to alleviate poverty through partnerships with local and international bodies.

- Sport can promote personal well-being and encourage social inclusion, which may lead to more significant economic participation. It can help educate and empower individuals with social and life skills for a self-reliant and sustainable life.

- Sport programmes in refugee camps can help young people understand the need for cooperation as well as self-reliance. Involvement in sport programmes can provide stability and a safe environment for homeless individuals.

- Sport is itself a productive industry with the ability to lift people out of poverty through employment and contributing to local economies. Sport and sustainable sport tourism can promote livelihoods, including in host communities of sport events.

References

- Wenner, L.A. Media, sports, and society. In Research Handbook on Sports and Society; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- The Sports Market. Available online: https://www.kearney.com/communications-media-technology/article?/a/the-sports-market (accessed on 21 May 2021).

- Burch, L.; Frederick, E.; Pegoraro, A. Kissing in the Carnage: An Examination of Framing on Twitter during the Vancouver Riots. J. Broadcast. Electron. Media 2015, 59, 399–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 7 Significant Political Events at the Olympic Games. Available online: https://www.britannica.com/list/7-significant-political-events-at-the-olympic-games (accessed on 18 April 2021).

- Brightman Almagor Zohar & Co. Sports Tech Innovation in the Start-Up Nation; Deloitte Israel: Tel Aviv-Yafo, Israel, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Global Sports Market Report (2021 to 2030)-COVID-19 Impact and Recovery. Available online: https://www.globenewswire.com/fr/news-release/2021/03/18/2195540/28124/en/Global-Sports-Market-Report-2021-to-2030-COVID-19-Impact-and-Recovery.html (accessed on 19 May 2021).

- Gough, C. Sports Media Rights Total Revenue in North America 2006–2023 Statista. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/194225/sports-media-rights-revenue-in-north-america/ (accessed on 19 May 2021).

- Hunt, H. Super Bowl Generates $95.8 Million Media Value for Five Biggest NFL Sponsors. Available online: https://insidersport.com/2021/02/18/super-bowl-generates-95-8-million-media-value-for-five-biggest-nfl-sponsors/ (accessed on 19 May 2021).

- The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. Available online: https://www.un.org/en/development/desa/population/migration/generalassembly/docs/globalcompact/A_RES_70_1_E.pdf (accessed on 17 May 2021).

- Baseball Has a Problem, and the Astros Are Only a Symptom. Available online: https://www.washingtonpost.com/sports/mlb/baseball-has-a-problem-and-the-astros-are-only-a-symptom/2020/02/09/d2eef1a8-49f0-11ea-b4d9-29cc419287eb_story.html (accessed on 2 June 2021).

- Deflategate, Shmategate: Aren’t We All Cheaters Anyway? Available online: https://daily.jstor.org/deflategate/ (accessed on 14 April 2021).

- Black Hockey Players on Loving a Sport That Doesn’t Love Them Back. Available online: https://www.macleans.ca/sports/black-hockey-players-on-loving-a-sport-that-doesnt-love-them-back/ (accessed on 27 May 2021).

- Raz, J. Morality as Interpretation. Ethics 1991, 2, 392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kidder, R. How Good People Make Tough Choices: Resolving the Dilemmas of Ethical Living; Morrow: New York, NY, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Lehnert, K.; Park, Y.; Singh, N. Research Note and Review of the Empirical Ethical Decision-Making Literature: Boundary Conditions and Extensions. J. Bus. Ethics 2015, 129, 195–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lysonski, S.; Durvasula, S. Digital Piracy of MP3s: Consumer and Ethical Predispositions. J. Consum. Mark. 2008, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Steenhaut, S.; Van Kenhove, P. The Mediating Role of Anticipated Guilt in Consumers’ Ethical Decision-Making. J. Bus. Ethics 2006, 69, 269–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahane, G.; Everett, J.; Earp, B.D.; Caviola, L.; Faber, N.S.; Crockett, M.J.; Savulescu, J. Beyond sacrificial harm: A two-dimensional model of utilitarian psychology. Psychol. Rev. 2018, 125, 131–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robin Hood. Available online: https://www.historic-uk.com/HistoryUK/HistoryofEngland/Robin-Hood/ (accessed on 28 May 2021).

- Craft, J. A Review of the Empirical Ethical Decision- Making Literature: 2004–2011. J. Bus. Ethics 2013, 117, 221–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forsyth, D. A Taxonomy of Ethical Ideologies. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1980, 39, 175–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Top 3 Countries with the Worst Human Rights Violations. Available online: https://borgenproject.org/human-rights-violations/ (accessed on 18 April 2021).

- China Events of 2020. Available online: https://www.hrw.org/world-report/2021/country-chapters/china-and-tibet (accessed on 29 May 2021).

- China to Host Winter Olympics on Time; IOC Chief Opposes Politicization of Olympics. Available online: https://www.globaltimes.cn/page/202105/1222889.shtml (accessed on 7 May 2021).

- Universal Declaration of Human Rights. Available online: https://www.un.org/en/about-us/universal-declaration-of-human-rights (accessed on 16 June 2021).

- China Primer: Uyghurs. Available online: https://fas.org/sgp/crs/row/IF10281.pdf (accessed on 10 June 2021).

- Genocide in Tibet-Children of Despair-Introduction by Paul Ingram. Available online: https://web.archive.org/web/20120119081639/http:/www.crin.org/docs/resources/treaties/crc.12/China_CFT2_NGO_Report.pdf (accessed on 13 June 2021).

- Nearly 40 Nations Criticize China’s Human Rights Policies. Available online: https://apnews.com/article/virus-outbreak-race-and-ethnicity-tibet-hong-kong-united-states-a69609b46705f97bdec509e009577cb5 (accessed on 19 April 2021).

- What Boycotting the Beijing 2022 Winter Olympics Could Look Like. Available online: https://www.ctvnews.ca/sports/what-boycotting-the-beijing-2022-winter-olympics-could-look-like-1.5377667 (accessed on 30 May 2021).

- Olympic Games Boycotts and Political Events. Available online: https://www.topendsports.com/events/summer/boycotts.htm (accessed on 23 May 2021).

- Munich 1972 Summer Olympics. Available online: https://olympics.com/en/olympic-games/munich-1972 (accessed on 14 May 2021).

- Unified Korean Olympic Team to March at Olympic Winter Games PyeongChang 2018. Available online: https://olympics.com/ioc/news/unified-korean-olympic-team-to-march-at-olympic-winter-games-pyeongchang-2018 (accessed on 4 June 2021).

- Canada’s Approach to Advancing Human Rights. Available online: https://www.international.gc.ca/world-monde/issues_development-enjeux_developpement/human_rights-droits_homme/advancing_rights-promouvoir_droits.aspx?lang=eng (accessed on 28 May 2021).

- Voices at Risk: Canada’s Guidelines on Supporting Human Rights Defenders. Available online: https://www.international.gc.ca/world-monde/issues_development-enjeux_developpement/human_rights-droits_homme/rights_defenders_guide_defenseurs_droits.aspx?lang=eng (accessed on 28 May 2021).

- Sport and the Sustainable Development Goals. Available online: https://www.un.org/sport/sites/www.un.org.sport/files/ckfiles/files/Sport_for_SDGs_finalversion9.pdf (accessed on 28 May 2021).

- Explainer: Boycotting the Beijing 2022 Winter Olympics and Other Options. Available online: https://www.latimes.com/world-nation/story/2021-04-07/beijing-2022-winter-olympics-boycott-options (accessed on 16 April 2021).

- Olympic Athletes and Federations React to the Postponement of the Tokyo Olympics. Available online: https://www.latimes.com/sports/olympics/story/2020-03-24/olympic-athletes-and-federations-react-to-the-postponement-of-the-tokyo-olympics (accessed on 19 May 2021).

- Reaction to the 1980 Olympic Boycott Decision. Available online: https://www.runnersworld.com/advanced/a20826758/reaction-to-the-1980-olympic-boycott-decision/ (accessed on 13 June 2021).

- How the US Boycott of the 1980 Olympics Still Influences the Event Today. Available online: https://observer.com/2017/12/1980-olympic-boycott-effects-examined-in-lead-up-to-2018-winter-games/ (accessed on 17 April 2021).

- How the IOC Finances a Better World through Sport. Available online: https://olympics.com/ioc/funding (accessed on 9 June 2021).

- The Economics of Hosting the Olympic Games. Available online: https://www.cfr.org/backgrounder/economics-hosting-olympic-games (accessed on 30 April 2021).

- Flyvbjerg, B.; Budzier, A.; Lunn, D. Regression to the Tail: Why the Olympics Blow Up. Environ. Plan. A Econ. Space 2020, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preub, H.; Andreff, W.; Weitzmann, M. Cost and Revenue Overruns of the Olympic Games 2000–2018; Springer Gabler: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- The Unpredictable Financial Costs of Hosting the Olympic Games. Available online: https://www.playthegame.org/news/comments/2021/1014_the-unpredictable-financial-costs-of-hosting-the-olympic-games/ (accessed on 10 May 2021).

- Toronto Can’t Afford Cost of Bidding or Hosting Olympics, Councillors Say. Available online: https://www.theglobeandmail.com/news/toronto/toronto-cant-afford-to-host-olympics-in-2024-councillors-say/article26169119/ (accessed on 18 May 2021).

- Moscow 1980 Olympic Games. The Editors of Encyclopedia Britannica. Available online: https://www.britannica.com/event/Moscow-1980-Olympic-Games (accessed on 26 June 2021).

- Beijing 2022: Human Rights Groups Call for Winter Olympic Boycott. Dan Roan and Alex Chapstick. Available online: https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-55938034 (accessed on 26 June 2021).

- Which Countries Are Net Exporters & Importers? Available online: https://www.statista.com/chart/18356/net-importers-and-exporters/#:~:text=China%2C%20which%20exports%20electronics%20and,world%20by%20a%20large%2 (accessed on 17 April 2021).

- GDP (Current US$). Available online: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.MKTP.CD (accessed on 23 December 2020).

- GDP, PPP (Current International $). Available online: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.MKTP.PP.CD (accessed on 23 December 2020).

- GDP Growth (Annual %). Available online: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.MKTP.KD.ZG (accessed on 23 December 2020).

- GDP per Capita (Current US$). Available online: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.PCAP.CD (accessed on 23 December 2020).

- Canada and China. Available online: https://cafta.org/trade-agreements/canada-china-trade/ (accessed on 8 March 2021).

- Population and Demography Statistics. Available online: https://www.statcan.gc.ca/eng/subjects-start/population_and_demography (accessed on 24 May 2021).

- Canada: Ethnic Groups as of 2016. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/271215/ethnic-groups-in-canada/ (accessed on 13 June 2021).

- Olympics: Host City Contract Requires Human Rights. Available online: https://www.hrw.org/news/2017/02/28/olympics-host-city-contract-requires-human-rights (accessed on 2 May 2021).

- Calls Grow Louder to Boycott Beijing’s Olympics and Analysts Warn of Retaliation from China. Available online: https://www.cnbc.com/2021/04/06/beijing-olympics-calls-for-boycotts-grow-but-china-seen-retaliating.html (accessed on 16 April 2021).

- Groups Call for Full Boycott of 2022 Beijing Olympics. Available online: https://www.cbc.ca/sports/olympics/full-blown-boycott-pushed-beijing-olympics-1.6029337 (accessed on 29 May 2021).

- Human Rights Groups Urge IOC to Move 2022 Winter Olympics Out of China. Available online: https://www.cbsnews.com/news/china-olympics-human-rights-groups-urge-ioc-to-move-2022-winter-games-tibet-hong-kong-uighurs/ (accessed on 19 April 2021).

- Kamloops Athletes Respond to Discussion of Boycott of 2022 Olympic Winter Games in Beijing. Available online: https://www.kamloopsthisweek.com/sports/kamloops-athletes-respond-to-discussion-of-boycott-of-2022-olympic-winter-games-in-beijing-1.24307696 (accessed on 28 April 2021).

- IOC Principles. Available online: https://olympics.com/ioc/principles (accessed on 14 May 2021).

- Canada Events of 2019. Available online: https://www.hrw.org/world-report/2020/country-chapters/canada# (accessed on 16 June 2021).

- The Right Right Thing to Do. Available online: https://aeon.co/essays/how-should-you-choose-the-right-right-thing-to-do?utm_source=Aeon+Newsletter (accessed on 16 April 2021).

- Beyond the Games. 2021 International Olympic Committee. Available online: https://olympics.com/ioc/beyond-the-games (accessed on 26 June 2021).

- Olympic Official Calls Protest a ‘Crisis’. Available online: https://www.nytimes.com/2008/04/11/world/asia/11china.html (accessed on 8 June 2021).

- Peace and Development through Sport. Available online: https://olympics.com/ioc/peace-and-development (accessed on 17 May 2021).

- Olympics a Test for Ambitious Developing Countries. Available online: https://globalnews.ca/news/1151958/olympics-a-test-for-ambitious-developing-countries/ (accessed on 22 May 2021).

- Maenning, W.; Vierhaus, C. Winning the Olympic host city election: Key success factors. Appl. Econ. 2017, 49, 3086–3099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maenning, W.; Vierhaus, C. Which countries bid for the Olympic games? The role of economic, political, social, and sports determinants. Int. J. Sport Financ. 2019, 14, 110–129. [Google Scholar]

- Opinion: Holding the Tokyo Olympics Amid the Covid Pandemic Is about Corporate Revenue, Not the Athletes. Available online: https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/2021/07/11/holding-tokyo-olympics-amid-covid-pandemic-threat-is-about-corporate-revenue-not-athletes/ (accessed on 13 July 2021).

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).