Abstract

Generational approaches to climate engagement among older adults remain limited. This study examines the evolution of eco-anxiety, environmental activism, and pro-environmental behavior from a life course perspective, focusing on older adults in Spain. A nationwide CATI survey of 3000 residents aged 18 and older was conducted, employing validated multidimensional scales for eco-anxiety, environmental activism, and pro-environmental behavior, each rescaled to a 0–10 range. Data were analyzed using descriptive statistics, analyses of variance, and hierarchical regression models to estimate linear and quadratic age effects beyond sex, education, and subjective social class. Results show that (1) eco-anxiety follows an inverted-U pattern, peaking at ages 45–49 and declining significantly after 60; (2) environmental activism remains high until the late sixties, while everyday pro-environmental behaviors sharply decline after retirement; and (3) eco-anxiety and environmental action in older adults are partially decoupled, reflecting the role of supportive personal and contextual factors beyond emotional concern. The findings challenge prevailing stereotypes of passive older adults by demonstrating that older age can constitute a significant period of climate engagement. Despite a slight decline in climate concern following retirement, the willingness to take action remains notably resilient. Older adults maintain consistent involvement in environmental volunteering and activism, often motivated by a desire to leave a lasting legacy and shaped by personal experiences of past crises and collective struggles. However, pro-environmental behaviors show a marked decrease in older adults, not due to diminished interest but likely as a result of structural constraints such as declining health, limited income, and inadequate housing conditions. This study suggests that, in the context of liquid modernity marked by rapid change and uncertainty, older adults may serve as societal anchors—preserving narratives, emotional bonds, and civic networks. Through policies that address structural barriers, this anchor role can be supported, empowering older adults to improve their well-being and strengthening community resilience in the face of climate change.

1. Introduction

The climate crisis has ceased to be a distant prospect and has become a daily reality that permeates family conversations, news broadcasts, and increasingly, the psychological well-being of individuals. In this context, recent literature has identified eco-anxiety as a specific form of psychological distress linked to the perception of environmental threats, characterized by chronic worry, rumination, and a certain degree of dysfunction in daily life [1]. Although eco-anxiety has been the focus of growing scholarly attention, particularly among adolescents and young adults [2], the relative scarcity of research addressing its manifestation across the adult life course—and especially among older adults—is both notable and, arguably, problematic [3]. This gap is especially paradoxical given that population aging and climate change are simultaneous processes that are reshaping the public agenda of the 21st century.

The life course is not merely a biological sequence; it also involves social trajectories, shared historical milestones, and culturally embedded repertoires of meaning that shape how individuals at different life stages perceive and respond to environmental threats [4]. As Bauman [5] suggests, we inhabit a condition of liquid modernity, in which frameworks of meaning and social certainties are increasingly fragile. These conditions influence how people perceive environmental risks and engage with sustainability issues, shaping eco-anxiety, environmental activism, and pro-environmental behavior. In this context, generational interpretations of environmental risk take on particular importance, especially as traditional ways of understanding humanity’s relationship with nature and the viability of a shared future become increasingly fragile and contested. Individuals socialized prior to the so-called “CO2 era” may exhibit comparatively lower levels of climate anxiety not necessarily due to apathy or disengagement—but because their cognitive and affective frameworks were formed in a historical context in which environmental threats were neither named nor framed with the urgency that characterizes current discourse. However, qualitative research conducted with Australian farmers [6], older Israeli adults [7], and rural activists in the United Kingdom [8] reveals that older individuals are not immune to climate-related distress. On the contrary, they experience unique combinations of nostalgia for lost landscapes, solastalgia—the distress caused by environmental change in one’s home environment—and profound moral concern about the environmental legacy they will leave to future generations. In this context, it is also important to note that experiencing eco-anxiety does not inherently translate into greater environmental engagement. In some cases, the emotional intensity associated with climate-related concern may lead to what has been described as eco-paralysis—a state of psychological exhaustion that inhibits proactive behavior [9]. In other instances, the same emotional response may serve as a catalyst for environmental activism, manifesting through practices such as digital advocacy, critical consumption, or participation in public demonstrations [10,11]. Whether eco-anxiety leads to mobilization or inaction is contingent upon a constellation of mediating factors, including perceived self-efficacy, community support, and the availability of culturally meaningful “scripts” for effective action [12]. In older adults, these variables are further shaped by age-specific conditions—such as retirement, declining health, and income constraints—as well as by a generational imperative: the moral drive to ensure a livable planet for children and grandchildren [13].

In Spain, empirical evidence on the relationship between eco-anxiety, environmental activism, and pro-environmental behavior across the life course remains limited in the context of climate change. Spain provides a pertinent context for examining aging and climate engagement, given its rapidly aging population, recurrent heatwaves and droughts, and strong tradition of local civic participation. These characteristics make the country particularly informative for studying how these phenomena manifest across the adult life course, with a focus on older adults. The present study—based on a CATI survey of 3000 residents aged 18 and older—aims to address this gap by exploring the evolution of eco-anxiety, environmental activism, and pro-environmental behavior from a life course perspective. Although the survey includes adults of all ages, the primary analytic focus is on older adults (aged ≥65 years), with particular emphasis on the later life segment. Our ultimate goal is to inform climate health and ecological transition policies that include—rather than merely protect—older adults, while strengthening community resilience in the face of climate change.

2. Theoretical Framework

2.1. Eco-Anxiety Across the Life Course

The Hogg Eco-Anxiety Scale (HEAS) operationalizes eco-anxiety through four closely interrelated facets: affective symptoms (e.g., restlessness, sadness), cognitive rumination, functional impairment, and anxiety specifically focused on one’s personal environmental footprint [1]. This structure reflects the notion that climate concern is not a singular emotional state, but rather a complex web of experiences ranging from constant monitoring of environmental news to a subjective sense of responsibility for harm to the planet. Cross-sectional studies—mainly with European and North American samples—identify peaks in eco-anxiety during early adulthood, followed by subsequent declines [2]. However, this pattern may result from an overlap between cohort effects and life course dynamics. From a developmental perspective, generations born from the 1990s onward have internalized climate risk as a central element of their socialization, whereas older adults incorporated it later and may therefore express it in less catastrophic terms [4].

Olszewski’s framework [3] adds nuance by proposing a U-shaped curve: in youth, moral urgency and intense media narratives heighten concern; in middle adulthood, work and family responsibilities temporarily shift attention elsewhere; and, finally, in old age, eco-anxiety resurges alongside increased physical vulnerability and greater exposure to extreme events. Indeed, the literature on climate-related disasters highlights that direct experience of persistent heatwaves, floods, or wildfires modulates the intensity of emotional responses in older adults [5]. The combination of physiological fragility, reduced support networks, and perceived socio-territorial dependence renders this group a sensitive barometer of the psychosocial effects of climate change. At the same time, the life course equips many older individuals with intergenerational coping strategies—such as storytelling, humor, and collective memory—that can mitigate or reframe eco-anxiety. This dynamic interplay between vulnerability and resilience has become an emerging focus in the psychology of climate aging. These emotional responses can serve as a powerful impetus for collective action, a topic we explore in the following section on environmental activism.

2.2. Environmental Activism in Old Age

Environmental activism takes on a wide range of forms, including signing digital petitions, participating in climate strikes, boycotting polluting companies, restoring local ecosystems, and engaging in strategic litigation. Far from the stereotypical image of activism as exclusively youth-driven, ethnographic studies confirm that older adults assume diverse roles within these struggles. The social movement “Knitting Nannas Against Gas and Greed” in Australia illustrates how protest can literally be “woven”—with needles and yarn—into communities of mutual care and popular pedagogy [14]. Similarly, the “River Guardians” described in the United Kingdom organize their activism around the defense of riverbanks, the transmission of ecological knowledge, and a strong sense of territorial belonging [8].

These expressions are closely linked to the Activity Theory of Aging, which holds that as people age, they can continue engaging in social and physical activities by adapting their life experiences and available resources—potentially giving rise to a motivation to leave a meaningful legacy for future generations [15]. This motivation is not limited to biological descendants; it encompasses a symbolic commitment to the community and the landscape that sustains it. In this way, environmental defense becomes an exercise in identity and biographical continuity, aligning with the Values–Beliefs–Norms (VBN) model, which posits that internalized biospheric values activate personal norms of moral obligation that, in turn, predict collective participation [16]. In practice, this value convergence grants older adults unique narrative capital: their life stories serve as testimony to long-term environmental change and as an ethical call for intergenerational action.

However, participation in protests is not without obstacles. Physical limitations, the digital divide, and the lack of sustainable transportation networks can restrict older adults’ presence at large-scale events. Even so, many overcome these barriers through forms of “proximity activism”: mentoring young activists, providing logistical support, disseminating accurate information, and applying political pressure through retirees’ organizations. These modes illustrate that older adult activism does not necessarily replicate youth repertoires but rather complements them with affective, temporal, and social resources specific to older adults. Beyond formal activism, these motivations and resources also shape a wide range of everyday pro-environmental behaviors.

2.3. Pro-Environmental Behavior in Older Adults

Pro-environmental behavior ranges from low-cost, straightforward symbolic behaviors—such as recycling, reducing plastic use, or adjusting the thermostat—to high-cost structural behaviors including adopting low-meat diets, installing solar panels, or investing in ethical funds [17]. Symbolic behaviors generally have a smaller direct environmental impact than structural behaviors, but can produce indirect effects through norm signaling and diffusion, and may serve social or identity functions. Comparative analyses reveal that age-related patterns are far from linear: older adults tend to excel in sustainable household practices and routines, while younger individuals are more likely to engage in active sustainable mobility and the consumption of “green” products [18]. This diversity calls for the refinement of existing theoretical frameworks.

The Theory of Planned Behavior [19] places perceived control at its core; in older adults, this perception may be weakened by fixed incomes, mobility limitations, or technological barriers. From a generational perspective, older adult pro-environmental behavior is often interpreted as an expression of legacy and moral responsibility toward descendants, which helps explain the persistence of conservationist habits even as physical capacities decline. However, it is important to recognize that other factors also influence behavior, as ideological and cultural variability, along with personal experiences, can also significantly influence how individuals from this cohort relate to environmental issues, adding a layer of complexity to the phenomenon [20]. In addition to these factors, research has shown that concern for the environment does not automatically lead to pro-environmental action. Other mediating factors—such as age, personal resources, and contextual conditions—play a critical role in shaping behavior [17]. Depending on these factors, eco-anxiety may either motivate action or fail to trigger it. Coates et al. [21] found that, in financial decision-making, individuals with moderate climate anxiety value sustainability as much as economic return—unlike those at the extremes, who tend to fall into either eco-paralysis or skepticism. In everyday practice, these logics intersect. For example, an older adult with moderate eco-anxiety and high self-efficacy may choose to engage in high-cost structural behaviors, such as installing solar panels—an action with a high initial cost but tangible long-term benefits. In contrast, another individual with high anxiety but low perceived control may limit their contribution to low-cost symbolic behaviors, while a third person, experiencing minimal anxiety, might see no need for any behavioral change. This behavioral spectrum underscores the importance of tailored interventions based on emotional profiles and the life resources available to each individual.

Taken together, these frameworks provide a coherent understanding of climate engagement in older adults. The Activity Theory of Aging highlights how participation in meaningful activities reinforces identity and well-being, the VBN model emphasizes moral and value-driven motivations, and the Theory of Planned Behavior focuses on attitudes, norms, and perceived control. From an environmental justice perspective, infrastructural inequalities—such as limited access to digital technologies or transportation—can further constrain opportunities to act [22]. Together, these frameworks illustrate how psychological, moral, social, and structural factors interact to shape eco-anxiety, environmental activism, and pro-environmental behavior across the adult life course.

2.4. Study Hypotheses

Systematic reviews emphasize the scarcity of longitudinal studies that integrate emotional and behavioral variables related to climate change in older adults [12]. This gap prevents researchers from determining whether eco-anxiety decreases, remains stable, or intensifies with age, and hinders the assessment of bidirectional causation between emotion and action. Additionally, psychometric adaptations of the HEAS rarely report age-disaggregated norms, limiting cross-cultural comparability and the identification of at-risk cohorts [20]. In the realm of activism, the prevailing narrative of “youth leadership” has rendered older adult contributions largely invisible, despite studies on climate strikes demonstrating their significant presence [10]. Finally, the methodological tendency to collapse pro-environmental behaviors into global indices persists, overlooking the behavioral selectivity that stems from the specific opportunities and constraints associated with different stages of life [18].

In response to these gaps in the academic literature, our study formulates the following hypotheses. H1: Eco-anxiety follows a curvilinear trajectory across the life course, peaking in midlife and rising again slightly in old age. H2: Environmental activism remains relatively high until approximately age sixty, after which it declines moderately. H3: Pro-environmental behavior follows a curvilinear trajectory across the life course, increasing through midlife and declining in older age, possibly due to the increasing influence of practical barriers (e.g., health, income, mobility, and digital barriers). Additionally, we formulate a fourth hypothesis to articulate the expected associations between these constructs. H4: The three key constructs—eco-anxiety, environmental activism, and pro-environmental behavior—are positively associated with one another: H4a. Eco-anxiety is positively associated with environmental activism; H4b. Eco-anxiety is positively associated with pro-environmental behavior, though this association is weaker than for activism (partial decoupling); and H4c. Environmental activism is positively associated with pro-environmental behavior. Through this approach, the analytical framework seeks to position older adults not merely as vulnerable recipients of climate impacts, but as key—and often underestimated—actors in the ecological transition.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Sampling Strategy and Data Collection

This study employed a structured telephone survey using Likert-type scales, administered through the Computer-Assisted Telephone Interviewing (CATI) method via both landlines and mobile phones (September and October 2024). A stratified random sample of 3000 residents aged 18 and older was drawn using census data from the Spanish National Institute of Statistics (www.ine.es, accessed on 10 September 2024) as the sampling frame. The sample was stratified by sex, five-year age group, and 19 regions (17 Autonomous Communities and 2 Autonomous Cities) to ensure coverage across key demographic and geographic subgroups. A disproportional stratified sampling approach was used to ensure sufficient sample sizes in each age/sex/region cell, and population weights were applied in the analyses to reflect the distribution of gender, age, and region in the Spanish population. To achieve the final sample of 3000 completed interviews, a total of 23,614 telephone numbers were contacted, yielding a response rate of 12.7%. The majority of non-completions were due to non-contacts (61.8% no answer), while refusals represented 2.8% of all calls. These outcomes are consistent with response patterns commonly observed in large-scale telephone surveys. The sample size provides a margin of error of ±1.79% at a 95% confidence level, assuming a population proportion of 50%. Each interview lasted approximately 25 min.

3.2. Survey Instruments: Development, Adaptation, and Scales Overview

The survey was designed to collect standardized data, enabling replication and extension of the findings in future research phases. Prior to implementation, the instrument’s reliability was assessed through a pilot test conducted with a small, socio-demographically diverse sample. Subsequently, the instrument underwent external review by three expert researchers. Ethical guidelines were rigorously observed throughout the process, and all datasets, coding schemes, and protocols related to the scales are available upon request.

The scales were administered following a strict protocol that included obtaining informed consent from participants and ensuring their anonymity. Each instrument was presented in a translated and culturally adapted version, thereby confirming its cultural validity. Linguistic adaptations followed established translation guidelines, including a rigorous back-translation process conducted by our research team and subsequently validated by bilingual Spanish-English speakers. All methodological decisions aimed to guarantee the reliability and reproducibility of the collected data.

Three primary scales were employed in this study, each adapted to a 0-to-10 response range to enhance practicality and facilitate visual analysis:

- Eco-Anxiety Scale. Our approach was based on the multidimensional instrument developed by Hogg et al. [23], designed to capture worry, nervous tension, and functional impairments experienced when reflecting on the climate crisis. The scale includes thirteen items addressing symptoms such as nervousness, intrusive thoughts about climate change, and difficulties sleeping or maintaining a relaxed social life due to climate-related anxiety.

- Environmental Activism Scale. This 5-item scale draws inspiration from Alisat and Riemer’s Environmental Action Scale [24] and aims to assess individuals’ participation in campaigns, social movements, and online spaces promoting lifestyles centered on reduced consumption and degrowth. The scale includes questions about attendance at awareness events, involvement in citizen initiatives, and engagement in forums or groups advocating environmental care (Appendix A).

- Pro-Environmental Behavior Scale. Comprising six items, this scale measures routine behaviors intended to minimize one’s ecological footprint. The items are based on the conceptualizations of Alisat and Riemer [24], as well as Drews and van den Bergh [25]. The scale covers aspects such as seeking information on ecological practices through social media, reducing personal emissions, and supporting initiatives focused on degrowth or environmental protection (Appendix A).

Table 1 confirms the metric robustness of the three instruments following their rescaling from 1–7 to 0–10. The uniform 0–10 range was chosen for consistency and ease of use, and while this may affect direct comparisons with original scales, the instruments’ psychometric properties remained robust, ensuring their validity for this study. For the Eco-Anxiety Scale (Table 1), the thirteen items yielded a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.948—a value approaching the upper limit of internal consistency, suggesting that all items converge on a single latent continuum. However, such high homogeneity warrants attention to potential semantic redundancies in future revisions. The mean score of 46.13 (SD = 18.31) corresponds to 3.55 points per item—a moderate level of climate concern—while the high standard deviation indicates interindividual heterogeneity, which is expected in a sample diverse in age and environmental experiences. Item-total correlations ranged from 0.68 to 0.80, supporting the decision to retain the adapted item matrix in its original form.

Table 1.

Summary of psychometric properties of the scales.

The Environmental Activism Scale shows similarly strong psychometric properties (Table 1). Despite comprising only five items, it achieved a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.946—nearly identical to the previous instrument, despite its brevity. The mean score of 13.81 (SD = 8.49)—approximately 2.8 per item—indicates that activist engagement is present but far from widespread; the level of dispersion suggests the coexistence of highly committed minorities alongside less active segments. Item-total correlations, all above 0.82, indicate that each item is essential for capturing the logic of activism, which is typically characterized by behaviors involving high symbolic and logistical costs.

Regarding the Pro-Environmental Behavior Scale (Table 1), reliability remains high (α = 0.881), though slightly lower—a finding consistent with the natural diversity of everyday practices included, ranging from recycling to reducing meat consumption. The mean score of 21.87 (SD = 8.98), or 3.64 points per item, is slightly higher than that of activism and aligns with the hypothesis that lower-cost behaviors are more widely distributed across the population. Here, item-total correlations range from 0.46 to 0.83, suggesting that certain activities—likely those more socially embedded—align more closely with the overall construct than others that are more situationally constrained. Overall, the high consistency of the three scales, combined with sufficient score variance, ensures both precision and analytical sensitivity—qualities that strengthen confidence in the explanatory models that will later explore the links between climate-related emotion, perceived efficacy, and environmental engagement across the life course.

3.3. Data Analysis

Data analysis was conducted using SPSS (v30). The dataset was first examined for missing values, which were addressed and harmonized as appropriate. Selected variables were then recoded and standardized to ensure comparability across measurement scales. Descriptive statistics were computed for each item within five-year age brackets. Bivariate correlations were computed to examine zero-order associations among eco-anxiety, environmental activism, and pro-environmental behavior, and their robustness was checked with Spearman’s and Kendall’s coefficients. Generational differences were assessed using analyses of variance (ANOVA), and a focused comparison of eco-anxiety, environmental activism, and pro-environmental behavior was performed based on an age-based dichotomy (≥65 years vs. <65 years). To control for family-wise error, we applied the Holm–Bonferroni correction to all p-values derived from ANOVAs and t-tests. Finally, hierarchical regression models were applied to evaluate the relative contributions of gender, education, and subjective social class (measured via a five-point self-placement scale), followed by the incremental influence of age—entered as both a linear and a quadratic term—on eco-anxiety, environmental activism, and pro-environmental behavior. We verified standard assumptions, including homoscedasticity and normality of residuals, and residual plots suggested no serious departures from these conditions. Therefore, no transformations of the variables were necessary to meet these assumptions. In addition, we conducted diagnostic checks for multicollinearity, with all Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) values falling below the conventional threshold of 5, indicating that the predictor variables were not excessively correlated. Cases with missing data on the variables included in the models were excluded, resulting in a total of 92 cases removed from the analysis (n = 2908 valid cases). This approach allowed us to assess not only whether age exerted an independent effect beyond other sociodemographic variables, but also whether its influence followed a non-linear trajectory across the life course.

4. Results

4.1. Description of Eco-Anxiety, Activism, and Environmental Behavior Across the Life Course

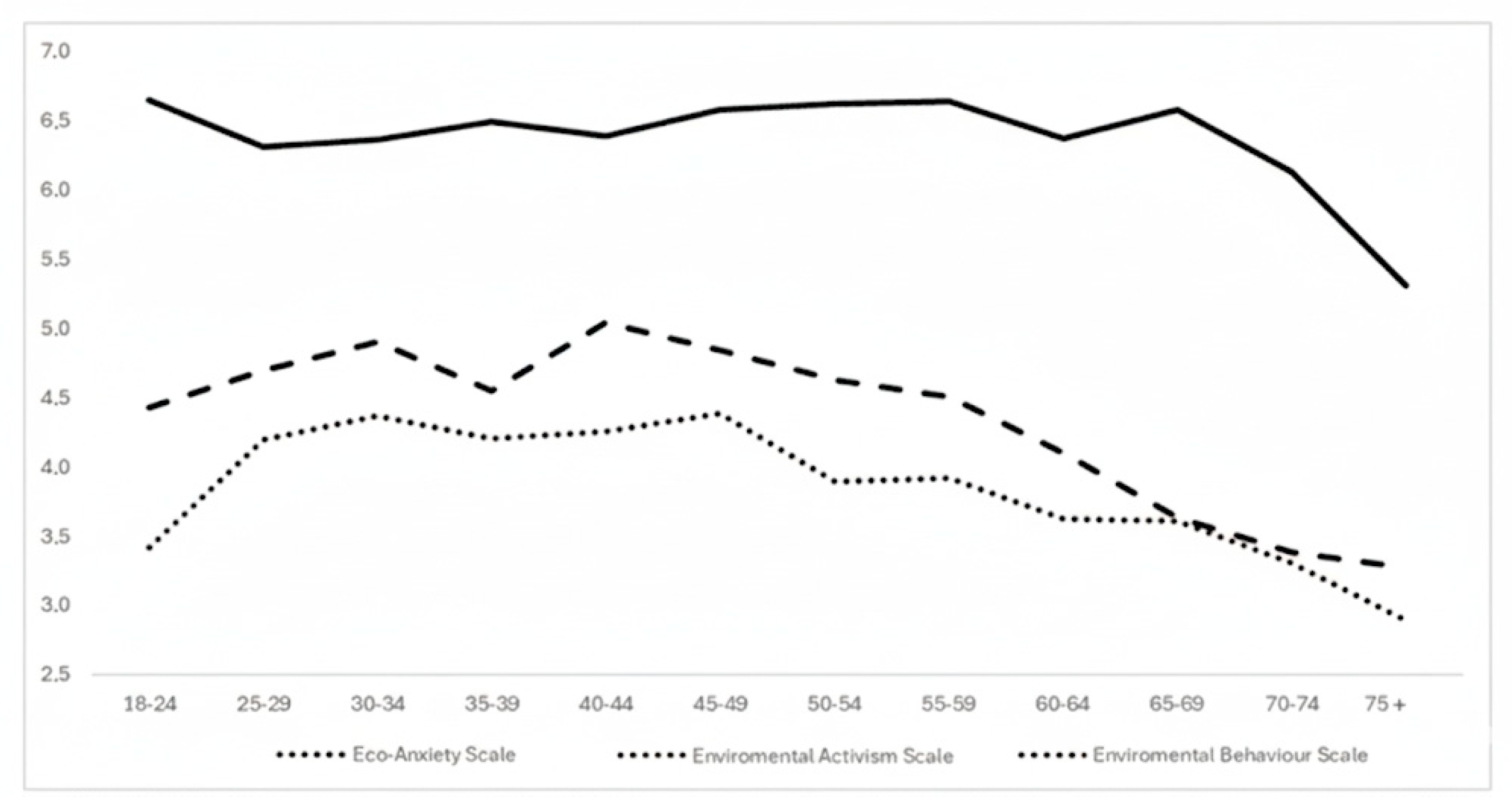

To examine the distribution of the three constructs across the life course, responses were grouped into five-year age brackets ranging from 18 to 75 years and older. The mean scores for each scale—already normalized to a 0–10 range—are presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Evolution of eco-anxiety, environmental activism, and pro-environmental behavior by age group.

Eco-anxiety exhibits an inverted U-shaped trajectory: it starts at a relatively low level among the youngest cohort (3.42), rises steadily to a peak in midlife (4.38 among those aged 45–49), and then declines almost linearly from age 60 onward, reaching 2.89 in the 75+ group (Figure 1). This pattern partially confirms Hypothesis H1. The older adults’ rebound reported in some studies is not observed in this sample, which may be interpreted through two non-mutually exclusive explanations: emotional adaptation through life experience or a shift in priorities toward more immediate health concerns.

Environmental activism shows a high and surprisingly stable plateau: all age groups up to age 70 exceeding the 6-point threshold (Figure 1). The highest score appears in the 18–24 age group (6.65), with a secondary peak in the 55–59 bracket (6.64). A more pronounced decline emerges only from age 75 onward (5.31), likely reflecting physical limitations and a contraction of activist networks. This intergenerational persistence largely supports Hypothesis H2: activism does not sharply decline with age, although a downturn is evident in advanced old age.

Pro-environmental behavior displays a more irregular trajectory (Figure 1). It gradually increases from youth to a peak among those aged 40–44 (5.04), a stage that coincides with peak purchasing power and, possibly, a greater capacity to adopt moderately costly behaviors (e.g., sustainable home practices or energy-efficient renovations). From age 50 onward, a steady decline begins, which becomes more pronounced among those over 65, who score below 3.4. This trajectory aligns with Hypothesis H3, suggesting that pro-environmental behavior increases through midlife before declining in older age. The contrast with the stability of activism suggests that everyday practices—more sensitive to economic resources, health, and housing context—are more affected by aging than symbolic civic participation.

Cross-analysis of the three constructs reveals notable interactions. Table 2 summarizes the relationship among the three constructs: eco-anxiety, environmental activism, and pro-environmental behavior through the life course. A general observation is that between ages 25 and 49, increases in eco-anxiety parallel rises in both activism and pro-environmental behavior, suggesting a potential mobilizing effect of moderate anxiety. However, in the 60–69 age range, eco-anxiety declines sharply while activism remains stable or even increases, indicating that motivation to act may persist despite reduced emotional distress, possibly due to a strong sense of generational responsibility.

Table 2.

Summary of eco-anxiety, environmental activism, and pro-environmental behavior across the life course and their interrelationships.

4.2. Bivariate Relationships Between Eco-Anxiety, Environmental Activism, and Pro-Environmental Behavior

Bivariate correlations (Table 3) show no significant association between eco-anxiety and activism (r = 0.01; p = 0.47), a small association between eco-anxiety and pro-environmental behavior (r = 0.12; p < 0.001), and a moderate association between environmental activism and pro-environmental behavior (r = 0.36; p < 0.001). This structure is consistent with a “partial decoupling” between emotion and action: while activism and everyday behaviors tend to move together, eco-anxiety does not directly translate into protest at the whole-sample level. These patterns, which are robust to Spearman’s and Kendall’s coefficients, support H4b–H4c and suggest that H4a is not supported in bivariate terms—activism among older adults appears to be sustained by resources and identities beyond emotional distress. Taken together, these results are consistent with the view that eco-anxiety is not a sufficient condition for triggering action—and that the absence of anxiety does not necessarily imply passivity—and provide empirical support for the role of eco-anxiety as catalyst/inhibitor.

Table 3.

Bivariate correlations among eco-anxiety, environmental activism, and pro-environmental behavior reported using Pearson’s r, two-tailed significance (p), and pairwise (N).

4.3. Generational Differences in Eco-Anxiety, Environmental Activism, and Pro-Environmental Behavior

The data confirms that age is a significant differentiating factor across all three constructs analyzed (see Table 4). First, regarding eco-anxiety, a difference of 0.76 points is observed: adults under 65 score, on average, above 4 out of 10, whereas older adults average 3.27 out of 10 (Table 4). This downward trajectory supports the inverted U-shape outlined in the previous section. Two interpretations emerge: (i) a possible process of emotional adaptation resulting from accumulated coping strategies, and (ii) a prioritization of health and family concerns that relegates climate change to the background.

Table 4.

Comparative summary of eco-anxiety, environmental activism, and pro-environmental behavior by age group (<65 vs. ≥65 years).

As for environmental activism, the average remains notably high in both groups, although the slight decrease of 0.42 points after age 65 is statistically significant (η2 = 0.037) (Table 4). This moderate reduction supports Hypothesis H2 but also calls for nuance: older adults, far from withdrawing from collective action, maintain levels of engagement close to the overall mean (6.00/10). This finding aligns with the Activity Theory of Aging and its emphasis on intergenerational legacy.

Everyday pro-environmental behavior shows the largest age-related gap (Δ = 1.20) (Table 4). The decline in sustainable household practices among those aged ≥ 65 is consistent with literature highlighting the influence of physical limitations, fixed incomes, and contextual barriers. The effect size (η2 = 0.053; Table 4) suggests that while aging may not diminish the subjective value placed on sustainability, it does reduce the capacity to translate that value into concrete behaviors—consistent with H3, which posits that practical barriers increasingly may limit pro-environmental behavior in older adults.

From a methodological perspective, the age-based dichotomy used (≥65 vs. <65) proved effective in isolating the overall effect of aging on the three variables, reducing the complexity of the original age brackets without sacrificing statistical power. The significance of the F-tests and the η2 values—modest but consistent—support the appropriateness of the cutoff. However, nonlinearity deviation analyses suggest that the relationship is not strictly linear, indicating the need to explore specific curvatures or inflection points in future analyses.

4.4. Hierarchical Models: Incremental Contribution of Age in the Three Climate-Related Dimensions

The hierarchical models show that, when age is introduced—first as a linear term and then as a quadratic component—it contributes substantive information not captured by gender, education, or subjective social class. Although modest in absolute terms, this added variance significantly refines the interpretation of how individuals experience the climate crisis emotionally and behaviorally.

In the case of eco-anxiety, the additional explanatory power is small in numerical terms—accounting for just three percent of the total variance—but carries significant interpretive value (see Table 5). The positive slope of the linear age term, combined with the negative coefficient for squared age, produces the anticipated inverted U-shaped curve: concern increases from youth to midlife and then begins to diminish. This finding partially supports Hypothesis H1. The effect remains even after controlling for subjective social class, which, notably, retains its influence in the expected direction: individuals in higher social positions report lower levels of climate anxiety. Neither gender nor education level has a meaningful effect once age is taken into account.

Table 5.

Summary of hierarchical regression models for eco-anxiety, environmental activism, and. pro-environmental behavior.

The pattern for environmental activism is different. Here, linear age alone introduces minimal variation, but the curvature does (Table 5). We observe a remarkably stable level of activism from the twenties through the sixties, followed by a gentle decline—a trajectory consistent with Hypothesis H2 on the resilience of ecological engagement up to the threshold of old age. Being female and, especially, having higher education continue to show positive effects, suggesting that certain cultural resources facilitate civic involvement across all cohorts.

Everyday pro-environmental behavior tells a different story. Here, age carries much greater weight: the proportion of explained variance nearly triples when age terms are included (Table 5). Once again, an inverted U-shaped curve emerges—but this time more sharply defined: sustainable household practices increase up to midlife—likely when stable income and family responsibility coincide—and drop rapidly after age sixty-five. This finding reinforces the behavioral dimension of Hypothesis H3: although older adults may retain activist motivations, they engage in fewer daily actions, possibly due to lower perceived efficacy or physical and economic barriers.

It is also worth highlighting the underlying sociodemographic dynamics. Being female increases both activism and behavior, but does not heighten eco-anxiety. Education has a strong effect on activism but fades when it comes to household routines, while subjective social class exerts opposing forces: it dampens anxiety but boosts action. The emerging picture is therefore one of partial “decoupling”: emotion, protest, and habits do not always move in sync over the life course.

Taken together, the models show that age does not operate as a simple upward or downward trend. Rather, it functions as a parabola that helps identify the points in the life course where climate concern, political mobilization, and sustainable routines align—and where by contrast, they diverge.

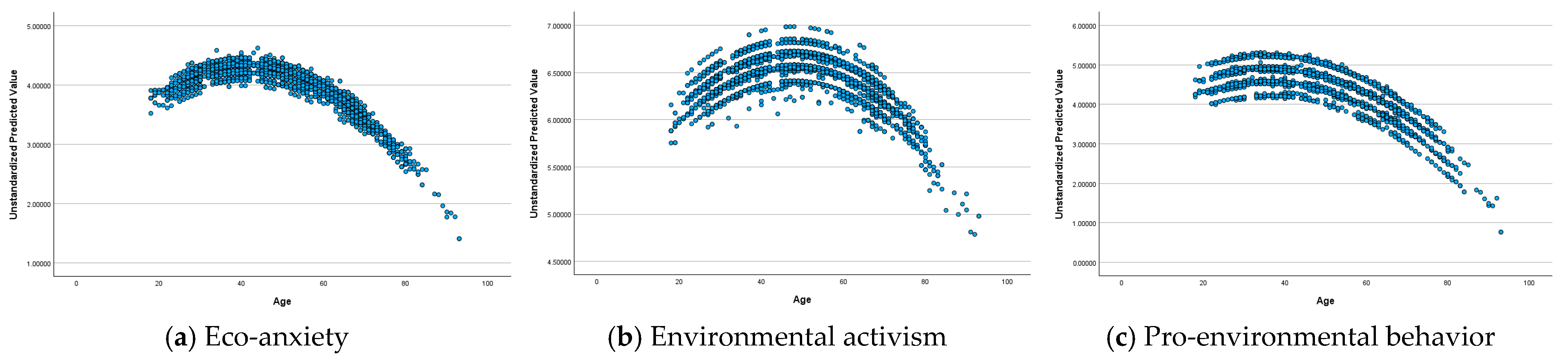

Figure 2a–c graphically display the age-adjusted trajectories for the three dependent variables, as estimated by the quadratic models presented in Table 5. All three dimensions exhibit a clear inverted U-shape, though with varying intensity. Eco-anxiety peaks between ages 40 and 50 and then progressively declines in old age. Environmental activism remains consistently high through midlife, with a milder inflection point, while pro-environmental behavior shows a sharper decline beginning around age 60. These visual representations reinforce the interpretation that age acts as a key moderating factor—not only in linear terms, but especially through its curvilinear dimension, as captured by the regression models.

Figure 2.

Age-trajectory patterns.

5. Discussion

This study examines eco-anxiety, environmental activism, and pro-environmental behavior from a life course perspective, with a particular focus on older adults in Spain. The findings both confirm and extend previous research, offering important implications for active aging programs and climate literacy strategies within the context of Bauman’s concept of liquid modernity [5].

5.1. H1: Eco-Anxiety and the Life Course: Between Vulnerability and Resilience

The inverted U-shaped trajectory of eco-anxiety—peaking in midlife and gradually declining after age 60—partially supports Hypothesis H1, and it offers a different pattern to Olszewski’s framework, which describes a U-shaped curve where eco-anxiety resurges in old age due to heightened physiological vulnerability and moral concern in older adults [3]. The older adults’ rebound observed in qualitative studies with Australian farmers [6] and older Israeli adults [7] is not clearly evident in our data. Instead, the findings might reflect processes of emotional adaptation or a reallocation of priorities toward other health-related concerns. This decline in eco-anxiety should not be interpreted as indifference, but rather as the result of coping strategies and a form of “pragmatic realism” shaped by previous life crises. From the perspective of liquid modernity, such adjustment may be seen as an attempt to “solidify” identity in a volatile world—through historical memory, spirituality, and family ties that serve to buffer anxiety.

5.2. H2: Older Adult Climate Activism in Action

The persistence of activism until around age 70 supports Hypothesis H2. Our quantitative findings extend this evidence: even as eco-anxiety declines, collective engagement remains stable, suggesting that such action is driven more by intergenerational values than by emotional intensity alone. This supports the notion that generational motivation functions as a civic driving force among older adults. Initiatives such as Australia’s “Knitting Nannas” [14] and the UK’s “River Guardians” [8] illustrate activism in older adults fueled by a sense of legacy. In this way, older adults construct “islands of stability” through community networks and care-based narratives that resist the institutional fragility characteristic of liquid modernity, linking personal well-being with social contribution.

5.3. H3: Everyday Pro-Environmental Behavior: Barriers and Levers

Pro-environmental behavior exhibits the most pronounced age-related gap, which confirms Hypothesis H3. The pattern observed reflects that, after age 60, the decline in everyday practices is largely shaped by specific barriers, including less energy-efficient housing, fixed incomes, mobility limitations, and the digital divide—factors previously identified in reviews on vulnerable populations [12]. Consistent with the Theory of Planned Behavior [19], reduced perceived control among older adults may further limit their capacity to translate environmental concern into action. Moreover, while older adults often maintain strong moral motivation and legacy-oriented intentions [18], these internal drivers may be insufficient to overcome practical constraints, resulting in lower engagement in high-cost structural behaviors. Consequently, everyday pro-environmental practices in this cohort tend to rely on low-cost, symbolic behaviors that can be maintained despite physical and economic limitations [17,20].

5.4. H4: Partial Decoupling Between Emotion and Action in Older Adults

Bivariate analyses provide partial support for Hypothesis H4. A moderate positive association between environmental activism and pro-environmental behavior confirms H4c, while the small association between eco-anxiety and pro-environmental behavior aligns with H4b, consistent with partial decoupling. Eco-anxiety shows no significant association with activism, failing to support H4a. Taken together, these results suggest that eco-anxiety is not a sufficient condition for action, nor does its absence imply passivity, highlighting its role as a potential catalyst or inhibitor, depending on individual resources and perceived control [17,21]. This pattern reflects a partial decoupling between emotional concern and civic action. As noted in Section 5.3, everyday behaviors are more sensitive to practical constraints, whereas activism remains robust due to social identity, generational values, and available resources rather than by emotional intensity alone [17,18]. These findings underscore the importance of considering both facilitators—such as self-efficacy and moderate eco-anxiety—and barriers—such as structural limitations—when designing interventions, in line with the Theory of Planned Behavior [19]. Tailoring strategies to individual emotional profiles and life-course conditions may help support continued participation in both civic activism and daily sustainable practices [20]. Future models incorporating mediators such as perceived behavioral control and opportunity structures could further clarify the mechanisms through which resources and identities sustain activism even when emotional distress is low.

5.5. Implications for Active Aging Programs and Climate Literacy

The first implication is the integration of eco-anxiety as an indicator of mental health in older adults. Brief screenings using culturally adapted versions of the HEAS [23]—whose cross-generational reliability has been validated in various countries [1]—could help identify at-risk profiles and prompt coping interventions grounded in optimism and resilience [13].

The findings call for policies that counter the atomization of liquid modernity [5] by supporting community-based and intergenerational initiatives, which could provide older adults with the stable social context needed to translate concern into sustained action. Equally important is the need to strengthen pro-environmental self-efficacy through in-person or digital educational programs that integrate practical knowledge, older adult-led success stories, and intergenerational mentoring. The experiential activism embodied by Australia’s “Knitting Nannas” [14], together with the community-based support observed in the UK’s “River Guardians” [8], suggests that biographical storytelling and service learning can translate moderate concern into sustained action. The ecological memory of older adults can be mobilized to create spaces for “climate storytelling,” in which older adults share memories of landscapes and traditional practices—enhancing climate literacy among younger generations while simultaneously reinforcing older adults’ self-esteem. This approach aligns with frameworks on conscious consumption and “mindful buying,” which emphasize the interconnection between identity and sustainability [16]. To advance in this direction, it is essential to develop socially inclusive public policies for ecological transition that acknowledge and emphasize, among other factors, the active role of older adults. Consistent with this approach, the adoption of multiple integrated measures is necessary—such as the redesign of inclusive green infrastructure to ensure universal accessibility and improved public transportation, thereby helping to bridge the gap between symbolic activism and everyday pro-environmental behavior. Additionally, promoting local cooperatives and circular economy networks can foster sustainable social practices compatible with fixed-income budgets.

From a climate health policy perspective, these findings suggest the importance of integrating mental health screening, community resilience, and climate literacy into national and local adaptation plans. By recognizing eco-anxiety as both a health and social issue, policies can support preventive interventions and resource allocation that strengthen older adults’ agency. For community programs, the evidence underscores the value of intergenerational platforms where older adults contribute lived ecological knowledge, while also benefiting from peer support and collective efficacy. Finally, in terms of intergenerational engagement, structured mentorship schemes and climate storytelling initiatives can function as low-cost, high-impact strategies that not only foster pro-environmental behavior but also enhance well-being, social cohesion, and trust between generations.

5.6. Limitations and Future Research Directions

The cross-sectional nature of the survey data constrains our ability to establish causality and prevents a complete disentanglement of age, period, and cohort effects. Longitudinal designs would be required to examine these dimensions more systematically. To mitigate this limitation, we employed hierarchical regression models that estimate the incremental contribution of age once socio-demographic variables are controlled. While this strategy does not eliminate potential cohort effects, it reduces confounding and enhances the robustness of our life-course interpretations. The 0–10 rescaling of the instruments facilitates comparison but may affect psychometric properties in populations with low digital literacy—an issue that should be examined through invariance analyses [1]. Additionally, pro-environmental behavior was assessed via self-report, which is vulnerable to social desirability bias; future research should incorporate objective indicators such as energy consumption or mobility data [18]. Future research may benefit from combining this quantitative approach with qualitative methods, such as in-depth interviews or diary studies, to gain a deeper understanding of personal motivations and lived experiences. Integrating macro-level variables (e.g., heatwaves, air quality) and micro-level factors (e.g., health, social networks) into multilevel models would enable the capture of complex interactions. Finally, further research should explore how socioeconomic inequalities influence the age–climate relationship—particularly in contexts of energy poverty and unequal exposure to extreme events—and to compare Spain’s situation with that of other middle- and low-income countries, in order to develop a truly inclusive perspective on the ecological transition.

6. Conclusions

The study’s findings indicate that older age can serve as a meaningful stage of climate engagement. While eco-anxiety tends to decline slightly in older adults after retirement, their motivation for action frequently persists. This suggests that moderate levels of eco-anxiety, when coupled with a high sense of self-efficacy and supportive personal resources, may foster collective engagement—more clearly for activism and, to a lesser extent, for everyday pro-environmental behavior—without necessarily leading to eco-paralysis. Moreover, this study confirms that the consistent involvement of older adults in environmental volunteering and climate activism can often be motivated by a desire to leave a lasting legacy and by personal memories of past crises and collective struggles. Finally, this study underscores that everyday pro-environmental behaviors become increasingly constrained in older adults—not due to a lack of interest, but probably as a consequence of structural barriers, including inadequate housing, limited financial resources, and digital exclusion, which frequently hinder the ability to translate environmental concern into sustained action. Through the lens of Bauman’s concept of liquid modernity, these findings gain further resonance. In an era marked by rapid change and uncertainty, older adults can act as societal anchors—preserving narratives, emotional connections, and civic networks. This stabilizing role holds significant implications for climate resilience planning, civic inclusion, and public communication, as supporting older adults’ contributions can strengthen community-wide responses to climate disruption. Despite the insights gained, several limitations point to important avenues for future research. Longitudinal studies are needed to better understand how climate-related emotions and behaviors evolve over time in older populations. Incorporating objective measures—such as actual energy consumption data—would help mitigate biases associated with self-reported behaviors. Furthermore, comparative analyses between rural and urban settings, both within Spain and in other national contexts, could offer greater nuance regarding the structural and cultural factors that shape environmental engagement in older adults. Future research may also benefit from combining this quantitative approach with qualitative methods to capture complex interactions. Crucially, future research should continue to center the voices of older adults—those who have lived through socio-ecological transformations preceding the current climate crisis. Their perspectives offer not only empirical value but also a vital source of collective memory and resilience for addressing the uncertainties ahead.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.D.L.-R., A.L.-D., R.R.-P. and J.S.F.-P.; methodology, M.D.L.-R., A.L.-D., R.R.-P. and J.S.F.-P.; software, J.S.F.-P.; validation, J.S.F.-P.; formal analysis, J.S.F.-P.; investigation, M.D.L.-R., A.L.-D. and R.R.-P.; resources, M.D.L.-R.; data curation, M.D.L.-R.; writing—original draft preparation, R.R.-P. and J.S.F.-P.; writing—review and editing, M.D.L.-R. and A.L.-D.; visualization, J.S.F.-P.; supervision, M.D.L.-R.; project administration, M.D.L.-R.; funding acquisition, M.D.L.-R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was conducted with financial support from “La Caixa” Foundation within the call of The social impact of Climate Change in Spain in 2024 (FS23-2B171). MDLR acknowledges funding support through the Ramon y Cajal fellowship (RYC2023-045489-I) financed by MICIU/AEI/10.13039/501100011033 and by ESF+.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the University of Almería (UALBIO2024/035) on 11 July 2024).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study. CELESTE-TEL S.L. (NIF/CIF B96995469), C/Miramar, 43. Apartado de Correos 79, 46460 Silla (Valencia), certifies the informed consent of participants.

Data Availability Statement

Data supporting the findings of this study are openly available in Mendeley Data (under embargo until June 2026) at López-Rodríguez, María D.; Lozano Díaz, Antonia; Rodríguez-Puertas, Rubén; Bellido Cáceres, Juan Manuel; Franco, Rosemberg; Fernández-Prados, Juan Sebastián (2025), “Attitudes towards to Degrowth and Climate Change”, Mendeley Data, V1. https://doi.org/10.17632/ssc47ksxf4.1 [26].

Acknowledgments

The authors are sincerely grateful to all individuals for their time and cooperation in responding to the survey.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

- Environmental Activism Scale (5 items):

- I participate in social movements or collectives that advocate adopting simpler, degrowth-oriented practices to change the course of climate change.

- I get involved in awareness-raising campaigns about adopting simpler, degrowth-oriented lifestyles.

- I get involved in awareness-raising campaigns on the climate crisis.

- I participate in online groups or forums to encourage others to adopt simpler, degrowth-oriented practices.

- I participate in online groups or forums to raise awareness about the importance and consequences of climate change.

- Pro-Environmental Behavior Scale (6 items):

- I actively seek to reduce my personal consumption of natural resources and goods.

- I try to reduce my carbon footprint (e.g., minimizing air travel and using renewables).

- I promote on my social networks events where climate change and its consequences are discussed.

- I promote on my social networks events related to adopting simple, degrowth-oriented lifestyles.

- I share or comment on social-media posts related to degrowth as a solution to climate change.

- I use social media and the internet to learn how to reduce my personal consumption of natural resources and goods.

References

- Spano, G.; Ricciardi, E.; Tinella, L.; Caffò, A.O.; Sanesi, G.; Bosco, A. Normative data and comprehensive psychometric evaluation of the Hogg Eco-Anxiety Scale in a large Italian sample. Heliyon 2025, 11, e41406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voltmer, K.; Harloff, L. Development and validation of the German Climate Anxiety Scale for Adolescents (GCAS-A). Prax. Kinderpsychol. Kinderpsychiatr. 2025, 74, 350–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olszewski, H. Climate and aging: Selected aspects from the psychological perspective. Oceanologia 2020, 62, 628–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pachana, N.A. Anxiety in later life and across the lifespan: Progress and future directions. GeroPsych 2024, 37, 63–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauman, Z. Modernidad Líquida; Scherer, A.G., Translator; Fondo de Cultura Económica: Ciudad de México, Mexico, 2003. (Originally published 2000). [Google Scholar]

- Ellis, N.R.; Albrecht, G.A. Climate change threats to family farmers’ sense of place and mental wellbeing. Soc. Sci. Med. 2017, 175, 161–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayalon, L.; Ulitsa, N.; AboJabel, H.; Engdau-Vanda, S. Perceptions of the changing climate in Israeli older persons. J. Appl. Gerontol. 2024, 43, 527–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gearey, M.; Ravenscroft, N. The nowtopia of the riverbank: Elder environmental activism. Environ. Plan. E 2019, 2, 451–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magruder, K.J.; Chipman, S.J. From eco-anxiety to eco-resilience: How ACT can counter environmental injustice. J. Hum. Rights Soc. Work 2025, 10, 294–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamponi, L.; Baukloh, A.C.; Bertuzzi, N.; Chironi, D.; della Porta, D.; Portos, M. The politicisation of lifestyle-centred action in youth climate strike participation. J. Youth Stud. 2022, 25, 854–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lozano-Díaz, A.; Fernández-Prados, J.S. Young Digital Citizenship in #FridaysForFuture. Rev. Educ. Pedagog. Cult. Stud. 2022, 44, 447–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, B.P.; Breakey, S.; Brown, M.J.; Smith, J.R.; Tarbet, A.; Nicholas, P.K.; Ros, A.M.V. Mental-health impacts of climate change among vulnerable populations globally. Ann. Glob. Health 2023, 89, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asiamah, N.; Mensah, H.K.; Ansah, E.W.; Eku, E.; Ansah, N.B.; Danquah, E.; Yarfi, C.; Aidoo, I.; Opuni, F.F.; Agyemang, S.M. Optimism, self-efficacy, and resilience with life engagement among older adults with severe climate anxiety. J. Affect. Disord. 2025, 380, 607–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Larri, L.J. Lifelong learning, well-being, and climate justice activism: Exploring social movement learning among Australia’s Knitting Nannas. Int. J. Popul. Stud. 2024, 10, 381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asiamah, N. Social Engagement and Physical Activity: Commentary on Why the Activity and Disengagement Theories of Ageing May Both Be Valid. Cogent Med. 2017, 4, 1289664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathur, A.; Moschis, G.P. Antecedents and outcome of mindful buying. J. Consum. Aff. 2023, 57, 1684–1713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kollmuss, A.; Agyeman, J. Mind the Gap: Why Do People Act Environmentally and What Are the Barriers to Pro Environmental Behavior? Environ. Educ. Res. 2002, 8, 239–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ágoston, C.; Balázs, B.; Mónus, F.; Varga, A. Age differences and profiles in pro-environmental behaviour and eco-emotions. Int. J. Behav. Dev. 2024, 48, 132–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The Theory of Planned Behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kryazh, I.; Baranov, V. Psychometric evaluation of the Ukrainian version of the Hogg Eco-Anxiety Scale. Insight 2025, 13, 117–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coates, Z.; Brown, S.; Kelly, M. Understanding the impacts of climate anxiety on financial decision making. Sustainability 2025, 17, 3815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlosberg, D. Reconceiving Environmental Justice: Global Movements and Political Theories. Environ. Politics 2004, 13, 517–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hogg, T.L.; Stanley, S.K.; O’Brien, L.V.; Wilson, M.S.; Watsford, C.R. The Hogg Eco-Anxiety Scale: Development and validation of a multidimensional scale. Glob. Environ. Change 2021, 71, 102391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alisat, S.; Riemer, M. The environmental action scale: Development and psychometric evaluation. J. Environ. Psychol. 2015, 43, 13–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drews, S.; van den Bergh, J.C.J.M. Public views on economic growth, the environment and prosperity: Results of a questionnaire survey. Glob. Environ. Change 2016, 1, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Rodríguez, M.D.; Lozano Díaz, A.; Rodríguez-Puertas, R.; Bellido Cáceres, J.M.; Franco, R.; Fernández-Prados, J.S. Attitudes towards to Degrowth and Climate Change [Dataset]. Mendeley Data, V1. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).