Abstract

Accumulating interest from academia and industry, the part of quality assurance in metal additive manufacturing (AM) is achieving incremental recognition owing to its distinct advantages over conventional manufacturing methods. In this paper, we introduced a convolutional neural network, YOLOv8 approach toward robust metallographic image quality inspection. Metallographic images accommodate key information relating to metal properties, such as structural strength, ductility, toughness, and defects, which are employed to select suitable materials for multiple engineering execution. Therefore, by comprehending the microstructures, one can understand insights into the behavior of a metal component and make predictive assessments of failure under specific conditions. Deep learning-based image segmentation is a robust technique for the detection of microstructural defects like cracks, inclusion, and gas porosity. Therefore, we improvise the YOLOv8 with dilated convolution mechanisms to acquire automatic micro-structure defect characterization. More specifically, for the first time, the YOLOv8 algorithm was proposed in the metallography dataset from additive manufacturing of steels (Metal DAM) to identify defects like cracks and porosity as a novel approach. A total of 414 images from ArcelorMittal engineers were used as an open-access database. The experimental results demonstrated that the YOLOv8 model successfully detected and identified cracks and porosity in the metal AM dataset, achieving an improved defect detection accuracy of up to 96% within just 0.5 h compared to previous automatic defect recognition processes.

1. Introduction

During the metal additive manufacturing (AM) process, the control parameters, like laser power, scanning speed, powder feed rate, and the excellence of the powder feedstock, significantly affect the formation of the parts, resulting in previous researchers being mostly focused on process parameters and performance optimization of AM parts to reduce the presence of the defects [1,2,3]. However, manually adjusting these multiple parameters to find the best process parameter is extremely labor-intensive and time-consuming, which can be solved by viable alternative automatic defect detection using AI deep learning algorithm [4,5]. The typical defects that exist in the AM process are gas porosity and cracks due to lack-of-fusion (LoF), which have adversely affected the properties of laser metal deposition fabricated parts [6]. Reichardt et al. attempted to fabricate gradient specimens transitioning to Ti6Al4V from AISI 304L stainless steel(s); however, the build process was interrupted as a result of cracks [7]. Similar observations were made by Huang [8] and Cui [9], where cracks in the deposited material occurred prior to analysis. Gas porosity, resulting from gas entrapment within the powder feed system present in the powder particles, has also been identified as a contributing factor [10,11]. This type of porosity has the potential to manifest at various specific locations and typically exhibits a nearly spherical shape. Gas porosities are considered intensely undesirable in the context of fatigue resistance and mechanical strength. The noticeable impact of porosity was observed by Sun, revealing that a gas porosity content of 3.3% in the AM of steel resulted in a significant decrease in ductility by 92.4% compared to the annealed counterpart [11,12]. In situations where insufficient energy is present in the melt pool, the inadequate melting of powder particles gives rise to lack-of-fusion (LoF) defects between layers [13]. These defects substantially contribute to variations in the mechanical properties of each deposition, thereby serving as a primary impediment to the widespread adoption of metal additive manufacturing (AM) technology, requiring meticulous quality inspection.

To reduce the mentioned metal AM defects, the AI deep learning-based defect inspection method has been continuously improving as a current research topic. Barua et al. employed the deviation of the melt-pool gradient temperature from a defect-free curve as a predictive measure for gas porosity in the laser metal deposition (LMD) process [14]. In another study, the application of Gaussian pyramid decomposition, along with low-resolution processing and center-surround operation, was utilized for the detection of defects in steel strips. Nevertheless, it may result in the loss of important image information [15]. Based on artificial neural networks, LeCun et al. introduced the LeNet model, which incorporated convolution and pooling layers for the purpose of digits recognition [16]. However, the progress of convolutional neural networks (CNNs) was hindered for a significant period of time due to limitations in the computation performance of both the graphics processing unit (GPU) and central processing unit (CPU). With the utilization of GPU acceleration, Krizhevsky et al. introduced the AlexNet model [17], which resulted in significant improvements in both accuracy and computational efficiency for ImageNet dataset classification using Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs). The utilization of CNN-based methods in additive manufacturing (AM) holds significant importance as it has the potential to drive the paradigm shift towards real-time monitoring and quality inspection of additive build parts. Due to the complexity of the AM process, it is challenging to predict the whole additive process via analytical methods [18].

In recent years, AI deep learning has seen remarkable advancements, particularly in the field of computer vision, where “You Only Look Once” (YOLO) has emerged as a state-of-the-art approach in terms of accuracy and robustness for various tasks, including object detection, image classification and segmentation [19]. The major objective of this research is to explore an effective YOLO-based architecture along with its parameters for the robust inspection of metal direct additive manufacturing (DAM) specimens. Specifically, the focus will be on discussing the model training process, followed by a comprehensive failure analysis and performance evaluation. The failure mechanisms observed in Metal-DAM metallographic images of steel commonly stem from a variety of contributing factors, as depicted in Figure 1. These factors, encompassing the defects identified within our proposed model, have been instrumental in providing a comprehensive understanding of the existing research problem.

Figure 1.

(a) Metal DAM microstructural properties from metallographs. (b) Surface defects classification; crack-porosity observed in our proposed experiment on the MetalDAM–steel dataset.

The proposed method was evaluated using the publicly available Metal DAM dataset [20]. The significant contributions of this work are demonstrated below.

- (1)

- An end-to-end architecture for microstructural defect detection using YOLOv8 models was proposed where the input images to the models vary in terms of color space.

- (2)

- The proposed method achieved adequate results while evaluated on a publicly available metallographic dataset.

The paper is planned as follows: Section 2, as related work, surveys AI deep learning methods proposed by other scientific researchers of metallographic images. Section 3 is the research methodology of our proposed approach, and Section 4 analyzes the experimental results. Finally, Section 5 presents some concluding remarks pertaining to this work.

2. Related Work

Segmentation of metallographic microstructural images is deemed a strenuous task in the setting of real-time defect detection. The emergence of AI deep learning has spurred extensive research in recent times. Lin et al. [20] introduced a 3D convolutional-based segmentation network, CNN, for the precise casting defects detection and extracting microstructural properties through a single pipeline. Although deep learning heavily relies on a vast quantity of manually annotated data, its methodology is intricately designed to address various challenges and yield cutting-edge outcomes. Later on, Jin et al. [21] introduced a novel Dynamic Line-Image Shearing Interferometer (DL-ISI), and CNN approach, in combination with deep learning techniques, enabling the detection of crack initiation, showcasing the potential of big-data experiments paired with deep learning for detailed material characterization. Roberts et al. [22] proposed a dense-based U-Net model for identifying crystallographic defects in structural alloys. Through supervised training on a small set of high-quality steel defect images, the model achieved significant pixel-wise accuracy of 91% and 98% for dislocations and voids, respectively.

In addition, Ma et al. [23] used the popular Deeplab-based segmentation network considering binary mask image patches to evaluate the Al alloy defect identification. Besides, Barik et al. [24] study aimed to optimize the process parameters of wire arc AM for ER70S6 steel and to build a machine-learning (ML)-based support vector regression (SVR) model with tensile testing and metallography to predict the defect properties like porosity of deposited specimens. Moreover, the research articles [22,25] provide a clear insight into this domain with relatively simpler but effective methodologies. However, the majority of existing methods fail to leverage the potential of accurate predictions to exploit the complementary information from multiple steps, leading to suboptimal segmented masks.

Rosenberger et al. [26] introduced a deep learning-based methodology aimed at segmenting fracture surfaces to measure initial crack sizes and enhance reproducibility in fracture mechanics assessment. Through the implementation of semi-supervised learning, they successfully trained robust models requiring six times fewer labeled images, even achieving less than a 1% mean deviation, highlighting the significant potential of this approach in fracture mechanics assessment.

Later, Mutiargo et al. [27] utilized U-Net architecture to develop a deep learning system for detecting pores in additively manufactured XCT images. Their findings demonstrated that data augmentation greatly enhances detectability when employing the U-Net model, leading to a substantial reduction in required post-processing time and improved detection accuracy compared to traditional image processing techniques.

Neuhauser et al. [28] employed a camera for extrusion profiling, utilizing the YOLOv5 network to distinguish between flawless surface defects and other surface anomalies. This method allowed for rapid detection and accurate classification of defect surfaces, effectively meeting the requirements of industrial production equipment for surface defect detection.

Additionally, Redmon et al. [29] proposed a target detection system called the YOLO network, which transformed the target detection problem into a regression problem. By inferring the target’s frame and classification directly from multiple positions within the input image, this approach streamlined the detection process using a single neural network.

Currently, the YOLO object detector has gained significant popularity for its real-time capabilities, effective feature fusion methods, lightweight architecture, and improved detection accuracy. In terms of present uses, YOLOv5 and v7 are considered the most efficient and widely recognized deep learning algorithms for achieving real-time object detection. The YOLOv5 model implements the CSP (Cross-Stage Partial) network architecture, which reduces redundant computations and enhances computational efficiency. However, there are still limitations in YOLOv5 when it comes to detecting small and complex objects, particularly in additive manufacturing composite specimens, where further improvements are required.

YOLOv7 introduced a novel strategy of Trainable Bag of Freebies (TBoF) to enhance the real-time object detector performance. This innovative approach significantly improves the accuracy and generalization capability of object detection by implementing TBoF in three distinct object detector models (YOLOV3, SSD, and RetinaNet). However, it is important to note that YOLOv7’s performance in accurately segmenting metallographic defects in our CFRP model is hindered by limitations in training data, model structure, and hyperparameters.

Published in 2023, YOLOv8 set out to integrate the most effective algorithm of various real-time object detectors. Building upon the concepts of the CSP (Cross-Stage Partial) architecture introduced in YOLOv5 [30], the PANFPN feature fusion method [31,32], and the SPPF module, YOLOv8 sought to leverage these proven techniques to enhance its own object detection performance. In order to meet our project’s requirement, it also designed varying scales based on the scaling coefficient similar to YOLOv5. The major enhancements of this system encompassed the introduction of a state-of-the-art (SOTA) model, BCE (Binary Cross Entropy) loss for classification [33] incorporating object detection networks with resolutions of P5 640 and P6 1280, as well as YOLACT instance segmentation [34].

The regression loss used in the study comprised the CIOU (Complete Intersection over Union) loss and DFL (Distance-IoU Loss), while the VFL (Variable Feature Location) introduced an asymmetric weighting operation [35] resulting, this neural network promptly prioritized the localization distribution in close proximity to the object location, aiming to maximize the probability density at that specific location. Notably, YOLOv8 offers a highly extensible framework, enabling seamless support for previous versions of YOLO and facilitating easy performance comparison across different iterations.

The YOLOv8 backbone architecture is strongly reminiscent of YOLOv5, although it incorporates the C2f module in place of the C3 module. Inspired by the CSP concept and leveraging the ideas of ELAN (Ensemble Learning with Attention Networks) from YOLOv7, the C2f module brings further advancements to the backbone architecture [35]. By integrating C3 and ELAN, the C2f module in YOLOv8 not only ensures lightweightness but also enhances the flow of gradient information, thereby providing more comprehensive representation learning capabilities. Furthermore, the widely-used SPPF module is still employed at the end of the backbone. This involves three consecutive Maxpools of size 5 × 5, followed by a concatenation of each layer, enabling YOLOv8 to accurately handle objects of varying scales without sacrificing computational efficiency.

In the neck part, YOLOv8 continues the utilization of the PAN-FPN technique as its feature fusion method, which effectively enhances the integration and exploitation of feature layer information across multiple scales. The neck module in YOLOv8 is constructed from the idea of decoupling head architecture in YOLOx by combining multiple C2f modules, allowing YOLOv8 to achieve a higher level of accuracy by effectively combining confidence and regression boxes. The utilization of this approach in the last part of the neck module contributes to the improved performance and precision of YOLOv8.

In essence, a key attribute of YOLOv8 is its remarkable extensibility, enabling comprehensive compatibility with all YOLO variants while allowing convenient switching between different versions. This highly advantageous quality offers significant benefits to researchers involved in YOLO projects, affording enhanced flexibility and facilitating broader avenues of exploration. Due to its advantageous features, YOLOv8 was chosen as the baseline. Notably, YOLOv8 demonstrates excellent flexibility as it can be deployed on both CPU and GPU hardware platforms. Consequently, it is regarded as the most precise detector available currently. To date, aiming at 100% accuracy in quick succession of time, intensive efforts have been devoted, and an algorithm for Metal DAM defect detection based on online convolutional neural network YOLOv8 outperformed other versions [36,37,38,39]; more importantly, This architecture provides a feasible solution for the accurate detection in various Metal DAM defect structure like porosity, dent, crack and enhance the efficiency of defect classification, we integrate the concept of early identification of critical defects, yolo v8 object detection (see Figure 2).

Figure 2.

The structure diagram of YOLOv8 architecture that was used in our proposed experiment.

3. Research Methodology

In this paper, a deep-learning approach using YOLOv8 for surface defect detection on Metal DAM was proposed. The methodology section of the paper presents a comprehensive explanation of the procedures undertaken to execute the research. A schematic experimental closed-loop flowchart of the research approach is illustrated below in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Schematic experimental closed-loop flowchart of the research approach.

3.1. Dataset Preparation

The proposed method was evaluated using a publicly available metallography dataset from additive manufacturing of steels called Metal DAM [40]. All images were kindly provided by ArcelorMittal engineers as an open-access database. This dataset contains 414 images taken from a scanning electron microscope with resolutions 1280 × 895 and 1024 × 703. LabelImg is used for annotating the Metal DAM steel surface defects called cracks and porosity. The annotated images were split into sets of training, valid, and test purposes. The training set is used to train the exact experimental requirements of the deep learning approach, while the validation is employed to choose the best model based on its performance on the validation set. The testing set was used to evaluate the overall performance of the selected model. A well-prepared dataset preparation is an essential step in deep machine learning research for accurate validation. Here is a step-by-step approach to how the dataset was prepared for this study.

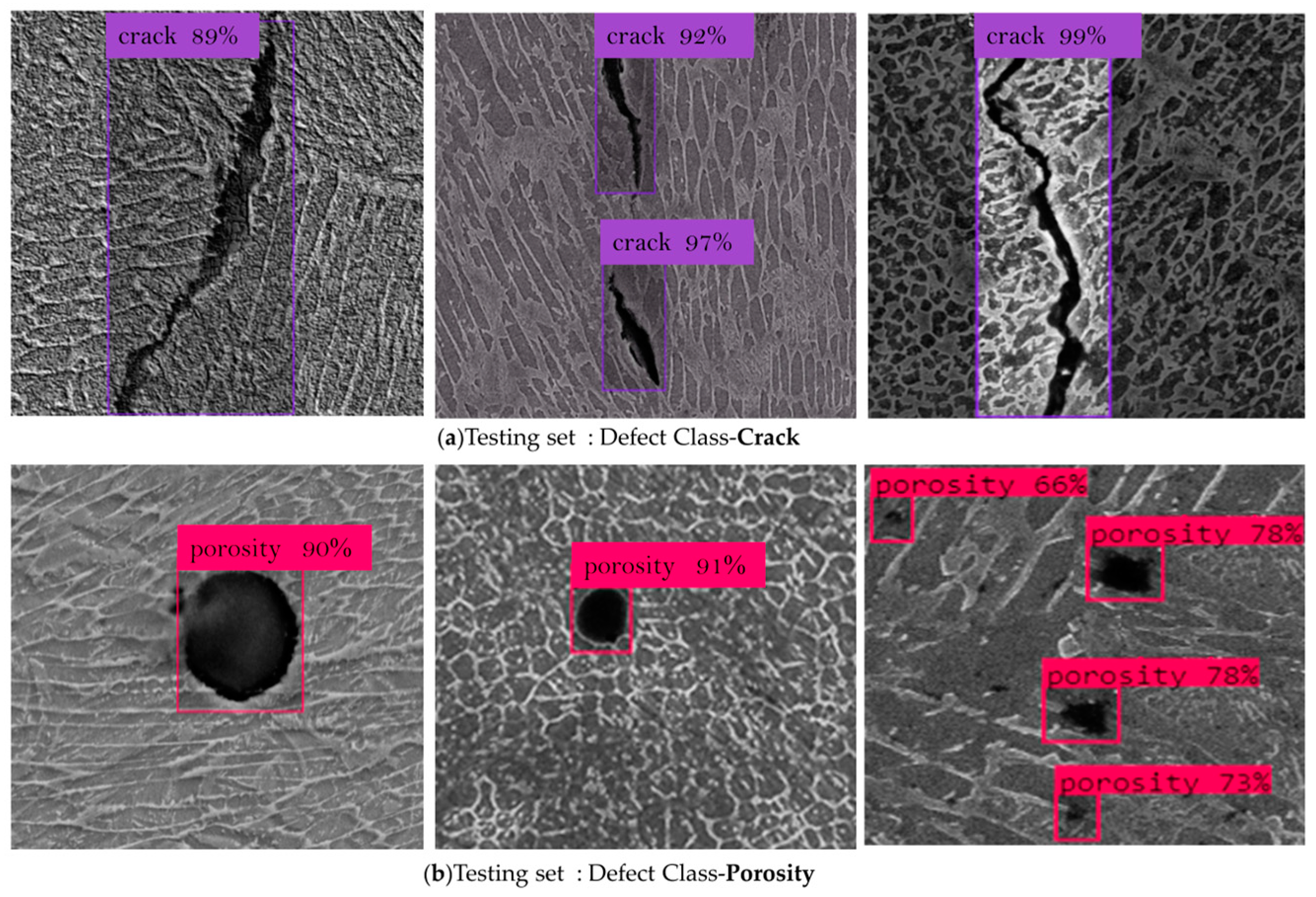

3.2. Dataset Annotation

The second step in dataset preparation is annotation. Annotation involves the manual labeling of the images to identify the regions of interest. In this study, the surface defects on the Metal DAM metallographic images were annotated using a bounding box. The annotations were done manually by drawing a bounding box around each surface defect region in the image using Python software with LabelImg coding. Specifically, within the dataset, the red square markings denote areas of porosity, while the purple squares signify cracks (refer to Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Sample splitting the dataset into train, validation, and testing sets.

3.3. Data Augmentation

The third step in dataset preparation is data augmentation which involves creating additional training samples from the original dataset by applying several transformations to the images. Data augmentation is necessary to increase the number of datasets and make the deep learning model more robust. In this study, data augmentation was performed by applying random rotations, brightness, flipping to the original images, and converting 200 images up to 400 images for better training.

3.4. Splitting the Dataset

The fourth step in dataset preparation is splitting the dataset into train, validation, and testing categories to evaluate the final performance of the selected model. In this study, the dataset was randomly split into 70% for the training set, 20% for the validation, and 10% for the testing set to avoid overfitting.

3.5. Pre-Processing

The preprocessing involves transforming the raw data into a suitable format for training the deep learning model. In this study, the images were resized to a fixed size of 640 × 640 pixels, and the pixel values of the images were standardized by normalizing to have a mean of 0 and 1 as a standard deviation.

Overall, the dataset preparation process involves collecting, cleaning, annotating, splitting, augmenting, and pre-processing the images to create a high-quality dataset that is suitable for training a deep machine learning model. Each step is critical to ensure that the dataset is representative of the real-world data and that the machine learning model can learn to detect surface defects on the Metal DAM specimen accurately.

3.6. Training Process and Performance Evaluation

The experimental platform initialization details for the experiment are presented in Table 1. After completing the model training, the average precision (AP) is employed as the evaluation metric for metal AM defect detection in this experiment, while the mean average precision (mAP) is used to evaluate the overall performance of the model. In defect detection, IoU (Intersection Over Union) quantifies overlap between two boxes, evaluating ground truth and prediction region overlap in object detection and segmentation. It measures the algorithm’s performance by comparing the intersection of predicted and ground truth bounding boxes to their union, with a value of 1 signifying perfect overlap and 0 indicating no overlap. A predicted bounding box is deemed ‘correct’ if its IoU score surpasses a specified threshold. The mathematical equations for IoU, precision, AP, and mA [41] are illustrated below.

Table 1.

Software and hardware parameters of the experimental platform.

4. Results and Discussion

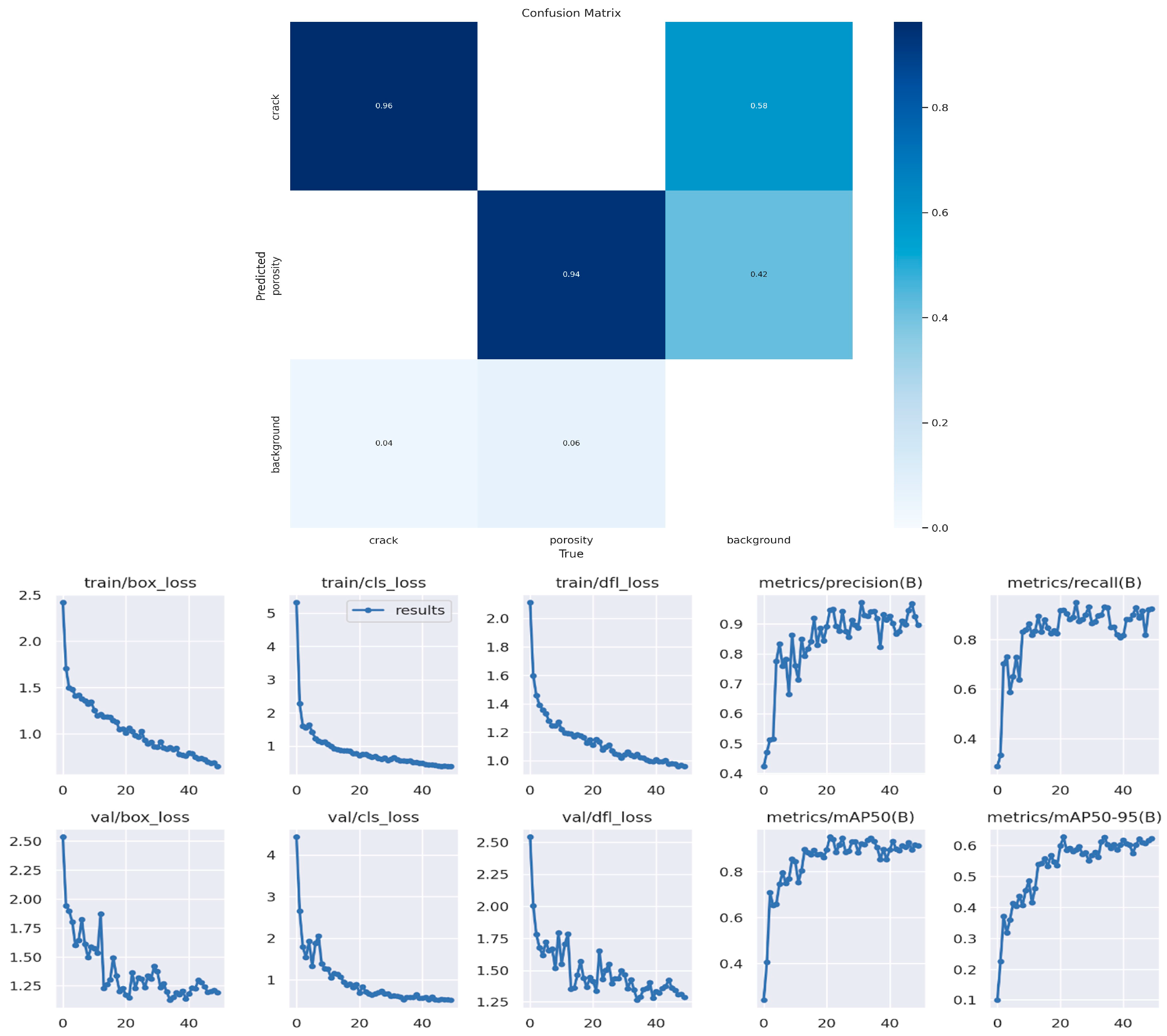

The proposed method (see Figure 5) was evaluated on a Metal DAM dataset of metallographic images with microstructural defects. The proposed method achieved a mAP (mean Average Precision) score of 0.96 and 0.94 for crack and porosity, respectively. Besides, the proposed model took 0.538 h for 85 epochs, 0.3 and 0.9 ms as pre-process and post-image process speed to recognize the complete automatic defect recognition process. Though we applied for 100 epochs for our training model, after 32 epochs where the value reached the highest, the next 50 epochs did not improve our model much, proving its early detection capability. The size estimation accuracy of the proposed method was also evaluated, and the results demonstrate that the size of microstructural surface defects can be estimated with an average error of less than 1%.

Figure 5.

Performance matrix, mAP, Recall, Precision graph of YOLOv8.

The evaluation graph accuracy reached up to 0.99, which was not only correctly identified metal DAM crack and porosity as a percentage of total metallographic samples but also proved the effectiveness of quick detection in a very short time. Precision is the percentage of correctly identified faulty surfaces in the total Metal DAM set that were all scored as positive. The recall metric is the percentage of correct predictions relative to the total number of valid predictions, which reached over 0.9 for our model. The F1 score takes into account both the accuracy and the number of correct predictions and has a maximum possible value of 1. Some faults in the Metal DAM sample were picked up by the YOLOv8 algorithm, but they can be ignored in consideration of 0.96 mAP results. Model performance and defect images are depicted in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

Final Metal DAM defect detection accuracy.

From the metallographic training model, validation assesses the performance of the YOLOv8 model on a separate dataset where it detects crack and porosity with an average value of 0.9. The validation set contains images that were not used during training. By evaluating the model on the validation set, we can assess its generalization ability and make adjustments to improve its performance. A detailed model test summary is illustrated in Table 2, where the precision value for crack and porosity reached up to 0.964 and 0.9, respectively, and the pixel size of the detected pictures is all 640 × 640.

Table 2.

Detailed model test results summary.

Overall, YOLOv8 Metal DAM detection accuracy in each layer performed as an excellent detector in terms of metallographic images. More importantly, for the first time, the YOLOv8 algorithm was proposed to identify metal DAM defects like cracks and porosity as a novel approach.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, the use of AI deep learning for the identification of Metal DAM defects is a relatively recent development that has gained momentum in the last few years. Early studies have shown the potential of AI deep learning for the automated detection and identification of AM steel surface defects, but recent studies have proposed novel methods for the detection of microstructural surface defects in 3D-printed Metal DAM, demonstrating the potential of AI deep learning inspection.

In this paper, our proposed model of YOLOv8 architecture and the experimental outcomes illustrated the effectiveness and perfections of the proposed method in detecting and measuring Metal DAM defects in steel specimens. The proposed model has the potential to improve the efficiency and accuracy of Metal DAM defect detection and contribute to the safety and reliability of Metal additive structures in various applications.

To be more precise, the final experimental results showed that the YOLOv8 model could effectively detect and identify cracks and porosity in the metal AM dataset, and compared with the previous automatic defect recognition process, the defect detection accuracy was improved up to 96% in just 0.5 h.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, supervision, funding acquisition, review and editing C.Z.; methodology, validation, image acquisition, software development, and formal analysis, M.H.Z.; review and editing, Y.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The authors are grateful for the financial support from the Innovation Group Project of Southern Marine Science and Engineering Guangdong Laboratory (Zhuhai) (No. 311021013). This work was also supported by the funding of the State Key Laboratory of Long-Life High-Temperature Materials (No. DTCC28EE190933), National Natural Science Foundation of China, grant number 51605287, and the Natural Science Foundation of Shanghai, grant number 16ZR1417100.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to confidentiality.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge Yawei He, School of Media and Communication, Shanghai Jiao Tong University, for YOLO experimental technology support and ArcelorMittal engineers for open-access database to conduct this research article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors whose names are mentioned certify that they have NO affiliations with or involvement in any organization or entity with any financial interest or professional relationships or affiliations in the subject matter discussed in this manuscript.

References

- Caggiano, A.; Zhang, J.; Alfieri, V.; Caiazzo, F.; Gao, R.; Teti, R. Machine learning-based image processing for on-line defect recognition in additive manufacturing. CIRP Ann. 2019, 68, 451–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Åkerfeldt, P.; Antti, M.-L.; Pederson, R. Influence of microstructure on mechanical properties of laser metal wire-deposited Ti-6Al-4V. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2016, 674, 428–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, G.; Zhou, R.; Lu, J.; Mazumder, J. Evaluation of defect density, microstructure, residual stress, elastic modulus, hardness and strength of laser-deposited AISI 4340 steel. Acta Mater. 2015, 84, 172–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, S.S.; Sheikh, K.H.; Mahanty, A.; Mali, K.; Ghosh, A.; Sarkar, R. A harmony search-based wrapper-filter feature selection approach for microstructural image classification. Integr. Mater. Manuf. Innov. 2021, 10, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.H.; Sarkar, S.S.; Mali, K.; Sarkar, R. A genetic algorithm based feature selection approach for microstructural image classification. Exp. Tech. 2021, 46, 335–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taheri, H.; Shoaib MR, B.M.; Koester, L.W.; Bigelow, T.A.; Collins, P.C.; Bond, L.J. Powder-based additive manufacturing-a review of types of defects, generation mechanisms, detection, property evaluation and metrology. Int. J. Addit. Subtractive Mater. Manuf. 2017, 1, 172–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reichardt, A.; Dillon, R.P.; Borgonia, J.P.; Shapiro, A.A.; McEnerney, B.W.; Momose, T.; Hosemann, P. Development and characterization of Ti-6Al-4V to 304L stainless steel gradient components fabricated with laser deposition additive manufacturing. Mater. Des. 2016, 104, 404–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.; Zhang, Y.; Vilar, R.; Shen, J. Dry sliding wear behavior of laser clad TiVCrAlSi high entropy alloy coatings on Ti–6Al–4V substrate. Mater. Des. 2012, 41, 338–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, W.; Karnati, S.; Zhang, X.; Burns, E.; Liou, F. Fabrication of AlCoCrFeNi high-entropy alloy coating on an AISI 304 substrate via a CoFe2Ni intermediate layer. Entropy 2018, 21, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Ghazanfari, A.; McMillen, D.; Leu, M.C.; Hilmas, G.E.; Watts, J. Characterization of zirconia specimens fabricated by ceramic on-demand extrusion. Ceram. Int. 2018, 44, 12245–12252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahsan, M.N.; Pinkerton, A.J.; Moat, R.J.; Shackleton, J. A comparative study of laser direct metal deposition characteristics using gas and plasma-atomized Ti–6Al–4V powders. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2011, 528, 7648–7657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ackermann, M. Metal Additive Manufacturing Porosity Images. Figshare. Dataset. 2023. Available online: https://figshare.com/articles/dataset/Metal_additive_manufacturing_porosity_images/22324993 (accessed on 1 October 2022).

- Åkerfeldt, P.; Pederson, R.; Antti, M.-L. A fractographic study exploring the relationship between the low cycle fatigue and metallurgical properties of laser metal wire deposited Ti–6Al–4V. Int. J. Fatigue 2016, 87, 245–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barua, S.; Liou, F.; Newkirk, J.; Sparks, T. Vision-based defect detection in laser metal deposition process. Rapid Prototyp. J. 2014, 20, 77–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, S. Strip steel defect detection based on saliency map construction using Gaussian pyramid decomposition. ISIJ Int. 2015, 55, 1950–1955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LeCun, Y.; Bengio, Y.; Hinton, G. Deep learning. Nature 2015, 521, 436–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krizhevsky, A.; Sutskever, I.; Hinton, G. Imagenet classification with deep convolutional neural networks. Commun. ACM 2017, 60, 84–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, X.; Chen, G.; Li, Y.; Cheng, X.; Li, C. Applying neural-network-based machine learning to additive manufacturing: Current applications, challenges, and future perspectives. Engineering 2019, 5, 721–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.; Chen, F.; Huang, H.; Li, D.; Cheng, W. A new steel defect detection algorithm based on deep learning. Comput. Intell. Neurosci. 2021, 2021, 5592878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.; Ma, L.; Yao, Y. Segmentation of casting defect regions for the extraction of microstructural properties. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2019, 85, 150–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, H.; Jiao, T.; Clifton, R.J.; Kim, K.-S. Dynamic fracture of a bicontinuously nanostructured copolymer: A deep-learning analysis of big-data-generating experiment. J. Mech. Phys. Solids 2022, 164, 104898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, G.; Haile, S.Y.; Sainju, R.; Edwards, D.J.; Hutchinson, B.; Zhu, Y. Deep learning for semantic segmentation of defects in advanced STEM images of steels. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 12744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, B.; Ban, X.; Huang, H.; Chen, Y.; Liu, W.; Zhi, Y. Deep learning-based image segmentation for al-la alloy microscopic images. Symmetry 2018, 10, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barik, S.; Bhandari, R.; Mondal, M.K. Optimization of Wire Arc Additive Manufacturing Process Parameters for Low Carbon Steel and Properties Prediction by Support Vector Regression Model. Steel Res. Int. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, J.; Van, D.; Jang, H.; Baik, D.H.; Yoo, S.D.; Park, J.; Mhin, S.; Mazumder, J.; Lee, S.H. Residual neural network-based fully convolutional network for microstructure segmentation. Sci. Technol. Weld. Join. 2019, 25, 282–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenberger, J.; Tlatlik, J.; Münstermann, S. Deep learning based initial crack size measurements utilizing macroscale fracture surface segmentation. Eng. Fract. Mech. 2023, 293, 109686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mutiargo, B.; Pavlovic, M.; Malcolm, A.; Goh, B.; Krishnan, M.; Shota, T.; Shaista, H.; Jhinaoui, A.; Putro, M. Evaluation of X-Ray computed tomography (CT) images of additively manufactured components using deep learning. In Proceedings of the 3rd Singapore International Non-Destructive Testing Conference and Exhibition (SINCE2019), Singapore, 2–5 December 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Neuhauser, F.M.; Bachmann, G.; Hora, P. Surface defect classification and detection on extruded aluminum profiles using convolutional neural networks. Int. J. Mater. Form. 2020, 13, 591–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redmon, J.; Divvala, S.; Girshick, R.; Farhadi, A. You only look once: Unified, real-time object detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Las Vegas, NV, USA, 26 June–1 July 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C.-Y.; Liao, H.-Y.M.; Wu, Y.-H.; Chen, P.-Y.; Hsieh, J.-W.; Yeh, I.-H. CSPNet: A new backbone that can enhance learning capability of CNN. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition Workshops, Seattle, WA, USA, 14–19 June 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, T.-Y.; Dollár, P.; Girshick, R.; He, K.; Hariharan, B.; Belongie, S. Feature pyramid networks for object detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Honolulu, HI, USA, 21–26 July 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, S.; Qi, L.; Qin, H.; Shi, J.; Jia, J. Path aggregation network for instance segmentation. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 18–23 June 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C.-Y.; Bochkovskiy, A.; Liao, H.-Y.M. YOLOv7: Trainable bag-of-freebies sets new state-of-the-art for real-time object detectors. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 18–22 June 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Bolya, D.; Zhou, C.; Xiao, F.; Lee, Y.J. Yolact: Real-time instance segmentation. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, Seoul, Republic of Korea, 27 October–2 November 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, Y.; Chen, K.; Loy, C.C.; Lin, D. Prime sample attention in object detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Seattle, WA, USA, 13–19 June 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Tamang, S.; Sen, B.; Pradhan, A.; Sharma, K.; Singh, V.K. Enhancing COVID-19 Safety: Exploring YOLOv8 Object Detection for Accurate Face Mask Classification. Int. J. Intell. Syst. Appl. Eng. 2023, 11, 892–897. [Google Scholar]

- Hussain, M. YOLO-v1 to YOLO-v8, the Rise of YOLO and Its Complementary Nature toward Digital Manufacturing and Industrial Defect Detection. Machines 2023, 11, 677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, S.; Divekar, A.V.; Anilkumar, C.; Naik, I.; Kulkarni, V.; Pattabiraman, V. Comparative analysis of deep learning image detection algorithms. J. Big Data 2021, 8, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.-a.; Sung, J.-Y.; Park, S.-h. Comparison of Faster-RCNN, YOLO, and SSD for real-time vehicle type recognition. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE International Conference on Consumer Electronics-ASIA (ICCE-Asia), Seoul, Republic of Korea, 1–3 November 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Luengo, J.; Moreno, R.; Sevillano, I.; Charte, D.; Peláez-Vegas, A.; Fernández-Moreno, M.; Mesejo, P.; Herrera, F. A tutorial on the segmentation of metallographic images: Taxonomy, new MetalDAM dataset, deep learning-based ensemble model, experimental analysis and challenges. Inf. Fusion 2021, 78, 232–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.; Huang, H.; Li, D.; Chen, F.; Cheng, W. Pointer defect detection based on transfer learning and improved cascade-RCNN. Sensors 2020, 20, 4939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).