Abstract

NFTs (non-fungible tokens) enable the commercialization of goods and services through blockchain technology, enhancing the security, transparency, and speed of transactions. The primary challenge NFTs face is their connection to the underlying asset, ensuring that transferring the token also means transferring the linked asset. This interdisciplinary article examines the technical and legal challenges of creating and linking a digital asset to an NFT. To explain the binding process, an NFT associated with a digital artwork was created, and relevant internal and uniform legal regulations were analyzed.

1. Introduction

NFTs (non-fungible tokens) are unique digital files that represent associated goods or services. This representation allows for their commercialization on the blockchain, providing security, immutability, and traceability to transactions, thus revolutionizing the exchange of goods and services. The tokenization of assets on the blockchain began on the Ethereum network, where the first smart contracts were implemented, enabling the emergence of tokens. NFTs have gained prominence in various sectors, including art, fashion, gaming, music, digital media, finance, and event ticketing1, gaining ground in complex areas such as real estate and airline tickets.

However, the increasing adoption of NFTs has raised a series of uncertainties that limit the confidence of those holding the rights to the token. These uncertainties stem from technical aspects such as the programming of the smart contract functions that create the token; the non-persistent storage of descriptive data linking the token to the artwork; and legal aspects such as the infringement of copyright, the transfer of intellectual property rights, and the establishment of a resale percentage of the NFT and its consequences regarding property rights, among other things.

Despite these concerns, the most significant challenge NFTs face is linking the token with the assets they represent. It is essential for the commercialization of NFTs on the blockchain that the technical linkage of an asset with the token has legal backing that recognizes the indissoluble relationship between the asset and the token representing it, ensuring that transferring the NFT also entails transferring the associated asset.

Given this context, the need to address the research problem from an interdisciplinary perspective was identified, allowing for an understanding of the phenomenon from its technical aspects to subsequently conduct a legal analysis. This approach enables the investigation to be tackled with methods and techniques from both engineering and law to achieve the study’s objective.

Therefore, the purpose of this work is to create an NFT associated with a digital artwork to identify the technical and legal challenges of linking the asset to the non-fungible token. To achieve this goal, the data structure of the created NFT was dissected, identifying its components to understand its functioning and determine if the analyzed technical standard genuinely supports the linkage of a digital asset. Subsequently, the current legal regulations were analyzed to determine if the technical linkage of the NFT with the asset has legal backing that allows the commercialization of the token to also mean the commercialization of the asset and its attached rights.

2. Methods

To achieve the stated objective, a structured methodology involving several critical stages was used from a technical perspective: creating a smart contract with predefined functionalities, deploying it on the Ethereum blockchain, and creating and storing the metadata file of the artwork in a decentralized storage system like IPFS. For legal matters, a qualitative method, dogmatic legal methodology, and documentary analysis were employed. The analysis focused on studying traditional internal norms and hard-law and soft-law legal bodies that concretely regulate this type of digital asset.

3. Approach to the Concept of Non-Fungible Token (NFT)

A token2 is a representation of an asset or a unit of value, which may exist outside the blockchain (casino or game tokens, and national currencies like the peso or the dollar) or within the blockchain (NFTs and cryptocurrencies), and is used for storage and transfer (Rath 2023).

The adoption of blockchain technology has generated two trends in assigning value to tokens. The first trend assigns value to “electronic records” not related to external rights; that is, economic value is given to a record in itself, without any linkage to assets or rights outside the blockchain. This is how cryptocurrencies arise. The second trend attributes value to electronic records by assigning them rights over external goods and services. This approach facilitates the transfer of rights over movable and immovable property, payment receivables, and other benefits (Uniform Commercial Code Amendments 2022a). Both trends are based on asset tokenization.

In this context, the meaning of a token is akin to a chip, understood from two perspectives: as a piece representing value and as a support for a set of metadata and data that can identify, inform, or classify something. Thus, a token can be both an asset in itself (as in Bitcoin) and the digital representation of another asset (an NFT of a digital artwork) (Zarifis and Cheng 2022; Bamakan et al. 2022).

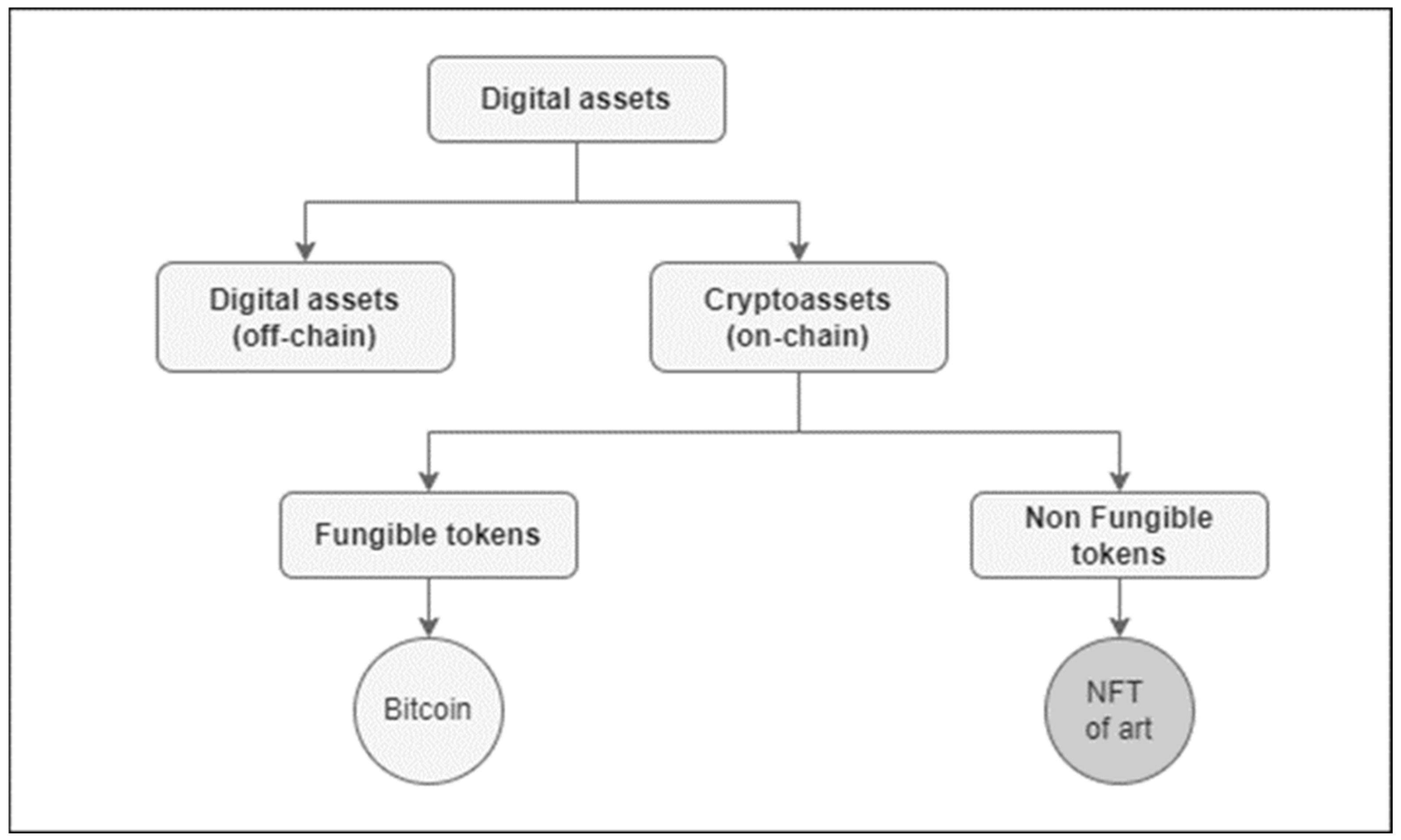

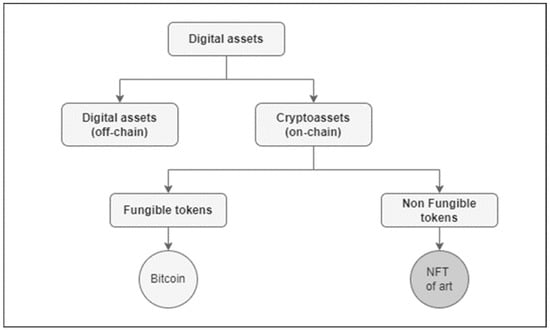

As shown in Figure 1, Bitcoin or any other cryptocurrency is a fungible token that is an asset in itself, or as defined by the Uniform Commercial Code of the United States, an electronic record with “inherent value”, since the market itself gives it value. On the other hand, an NFT is a token representing other goods or services, and, therefore, it is not an asset in itself but rather “evidence of the parties’ rights in a transaction” (Uniform Commercial Code Amendments 2022b, p. 233, Prefatory Note to Article 12), hence the importance of analyzing its linkage.

Figure 1.

Non-exhaustive taxonomy of digital assets from their relationship with the blockchain.

Tokens can represent utility, security, or equity in startups, providing investors with various rights and benefits (Tönnissen et al. 2020). They can also be used on various platforms, such as community-based ones like energy infrastructures or donation platforms, to incentivize participation and provide transaction transparency (Gong and Sun 2022; Karandikar et al. 2021). Tokens have thus become an integral part of blockchain-based business models, playing a strategic role in fundraising, ownership fractionalization, liquidity increase, and efficient transfer of assets and their rights, among many other uses.

The popularization of token creation on the blockchain occurred thanks to the Ethereum network3, which was the first to implement smart contracts4 enabling token creation using the ERC20 standard (Ethereum Request for Comments). This negated the need to establish a new network to create a token, accelerating their implementation and asset tokenization.

Tokenization is the process of representing real-world or digital assets5 in tokens recorded on the blockchain (Rath 2023). These tokens can be fungible, meaning that they can be exchanged for others of matching value, or non-fungible, meaning that they cannot be exchanged among themselves, as they are considered unique. Tokenization can also be used to grant temporary access rights and monetize private data, with blockchain technology ensuring secure and controlled access to sensitive information (Madine et al. 2022).

An NFT (non-fungible token) is a unique digital file representing rights to the associated assets, enabling various transactions with them. Since NFTs are unique files, the concept of rarity is introduced in the digital realm, allowing ownership and trade of digital assets that previously did not possess exclusivity or rivalry characteristics (Valeonti et al. 2021). This uniqueness is achieved through a unique identifier obtained via its associated smart contract (Putnings 2022), creating “a singularity that can be demonstrated and verified using the blockchain” (Gámez and Corredor 2023, p. 529). For this reason, they are used to support or prove rights to the linked asset or service (Wang et al. 2021; Guidi and Michienzi 2023). NFTs are being used to tokenize a wide range of assets, such as stocks, funds, debt, real estate, intellectual property (Bamakan et al. 2022), artworks6, music, photographs, and concert tickets, among other things.

Creating an NFT on a network like Ethereum can only occur through a smart contract7. Smart contracts define the characteristics, automate functions, and establish the transactional rules of the tokens (Tönnissen et al. 2020). Thus, the existence of the NFT, the number of tokens, the linkage with the asset, and aspects related to its transfer, being defined in the smart contract, produce an indissoluble relationship between them.

In summary, an NFT is a unique digital file on the blockchain associated with a file representing assets within or outside the blockchain, with characteristics and functionalities programmed into a smart contract.

4. Technical Description of an NFT

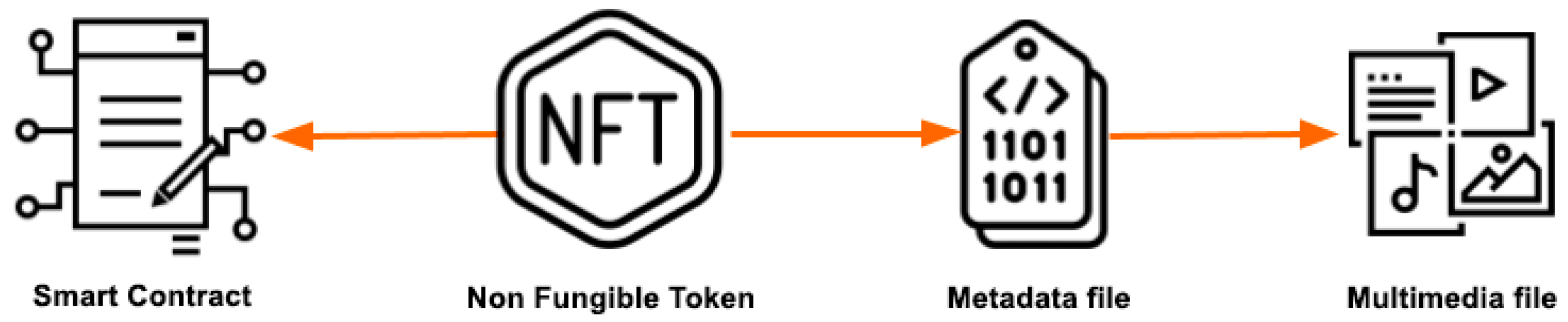

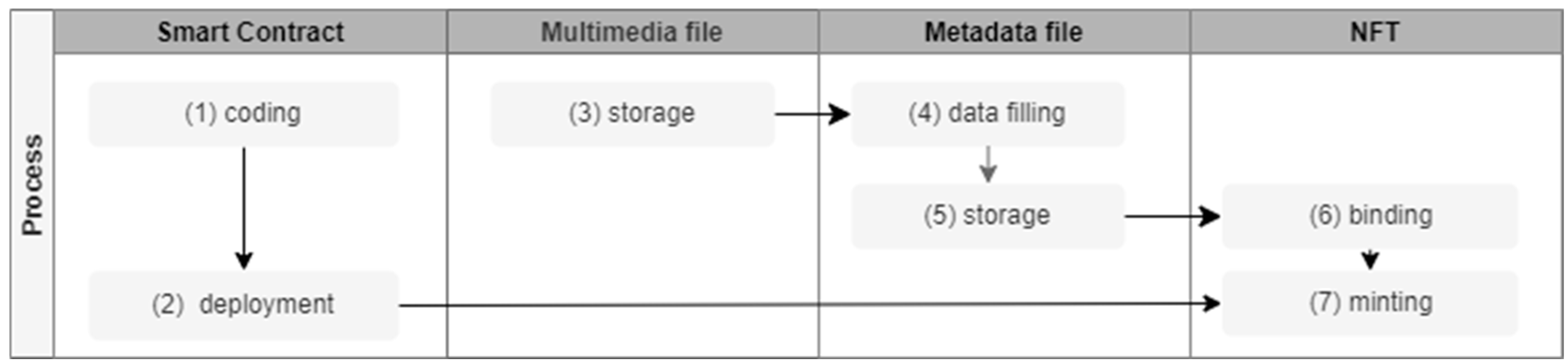

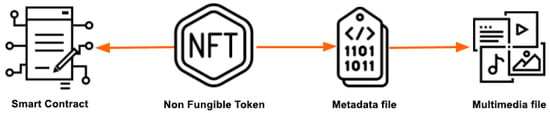

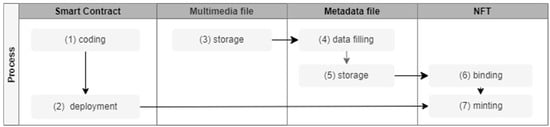

In summary, the creation of an NFT for a digital artwork followed these stages: First, a smart contract with predefined functionalities was developed. Second, the smart contract was deployed on the blockchain. Third, the metadata file of the artwork was created and stored, along with the multimedia file, in a decentralized storage system. Finally, the NFT was minted by executing the smart contract. Both are closely linked, as the smart contract defines the NFT’s functionalities. Figure 2 shows the elements associated with the NFT.

Figure 2.

Items associated with an NFT.

As seen in Figure 2, creating the NFT required a smart contract, the metadata file, the NFT, and the multimedia file. Each of these components is detailed here further.

4.1. The Smart Contract

From a technical perspective, a smart contract is defined as a set of self-executing terms of an agreement written in computer code (Valeonti et al. 2021). The smart contract was used to create this NFT and to define the characteristics and functionalities of the token to be minted.

To mint the token, a “Token Standard” was followed8. In the case of Ethereum, the primary standard for creating non-fungible tokens is ERC-721 (Entriken et al. 2018), also known as the “NFT standard”. This standard established the basic functionalities and properties of the NFT, allowing for interoperability and compatibility across different platforms and applications (Wang et al. 2021).

The smart contract generated a unique identifier for the NFT, which enabled an association with the contract under which it was created. The smart contract can be modified and adjusted to the logic of each business, for example, to generate an NFT collection and define how many or who can mint them.

Subsequently, the execution stage followed. For the smart contract to execute9, that is, to perform tasks such as minting the NFT, of facilitating transfers, it first had to be complied10 and deployed11 on a blockchain through a transaction. In this case, it was deployed on the Coinbase Base12network.

Once this process was completed, both the smart contract and the minted NFT could be consulted on the blockchain using the unique identifiers of each transaction. An explorer was used for this13.

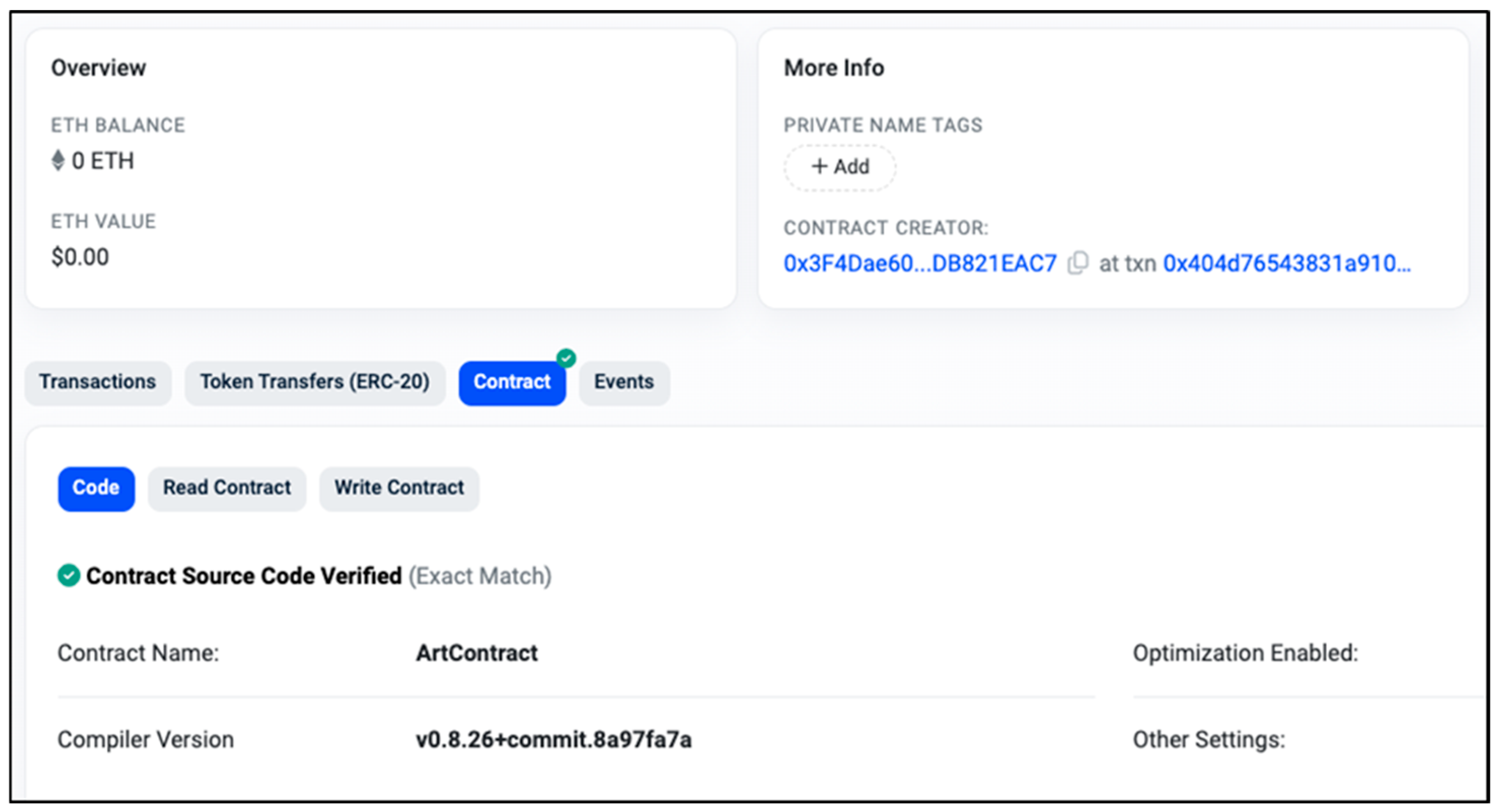

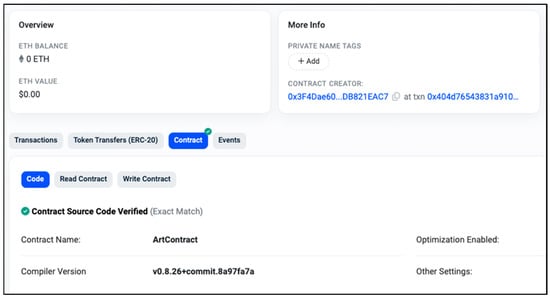

Figure 3.

Visualization of the ArtContract smart contract in the blockchain explorer.

As seen in the previous figure, the smart contract for creating the NFT included the following metadata:

- Contract (contract address): A hexadecimal number that serves to identify the contract on the network.

- Contract creator: Corresponds to the public address of the account with which the smart contract was deployed on the blockchain. The public address defines who owns the contract and grants control to the holder of the corresponding private key of the account.

- Token Name: Facilitates the memorization and search of the contract in the explorer. It consists of two parts, the full name and an abbreviation. In this case: UTADEONFT (UTD).

- Contract Name: In this case, the name of the contract is ArtContract.

- Compiler Version: Helps maintain compatibility and ensure code reproducibility since, once the smart contract is deployed on the blockchain, it becomes immutable.

As can be seen, the smart contract is the foundation for creating NFTs and their subsequent identification as unique tokens on the blockchain. This highlights the close relationship between the smart contract and the NFT.

4.2. The Metadata File

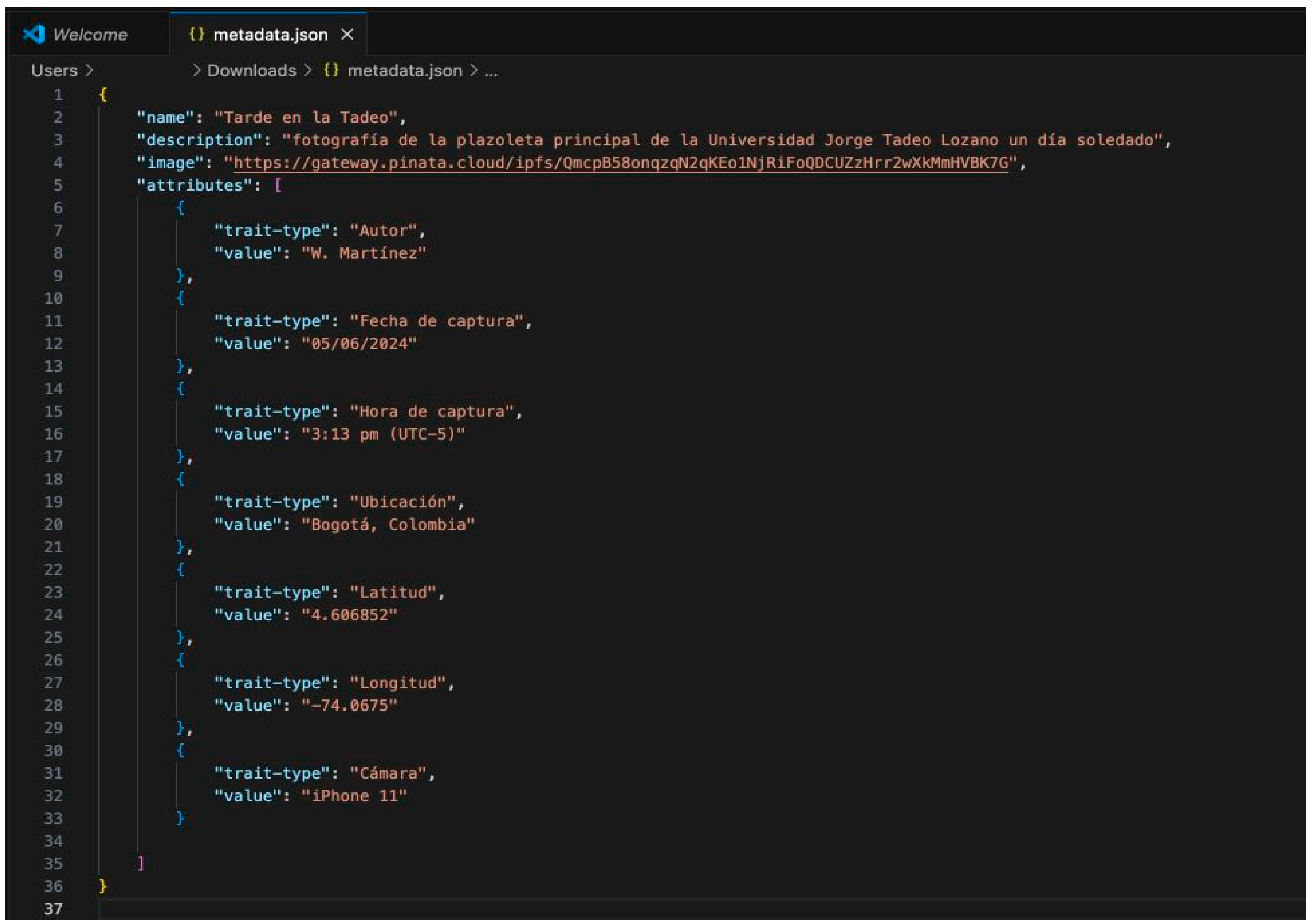

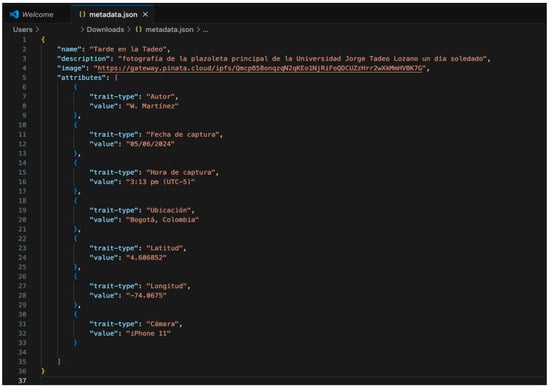

The second item associated with an NFT is the metadata file. With the contract deployed, the NFT could start being minted, but as previously mentioned, it is essential to have a metadata file that serves as a bridge between the NFT and the multimedia file (image and video) representing the asset, as it allows for its unequivocal identification. This metadata file contains descriptive and locational data of the asset, among other things. Below are the data and metadata used to describe the digital asset, which, in this case, is a photograph:

- Name: Tarde en la Tadeo.

- Description: Photograph of the main square of Jorge Tadeo Lozano University on a sunny day.

- Author: W. Martínez.

- Capture Date: 05/06/2024.

- Capture Time: 3:13 pm (UTC-5).

- Format: Landscape.

- Size: 1600 × 900 px.

- Location: Bogotá, Colombia.

- Latitude: 4.606852.

- Longitude: −74.0675.

For the NFT in this project, a metadata file was generated with the following structure in JSON format, as reflected in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Metadata file.

As seen in the previous image, the NFT metadata file contains the following data:

- Description: Corresponds to the brief description of the multimedia file associated with the NFT. In the case of a digital artwork, it refers to its description.

- External_url: A multi-purpose field that allows users to add a link to a webpage to complement information about the asset, the creator, and the collection, among other things.

- Image: A reference or link to the image, video, or other multimedia file associated with the asset (Shah et al. 2023).

- Name: The name or title of the NFT.

- Attributes: NFTs can have additional attributes or properties that provide specific information about the asset (Shah et al. 2023). Different types of traits and their corresponding values can be added here to describe the NFT (OpenSea 2023). These attributes can be predefined or customizable and may include traits such as color, rarity, edition number, or other unique characteristics of a work or asset.

4.3. The Multimedia File

The multimedia file represents the work or asset associated with the NFT. This representation is made through a file that can contain an image, photo, video, and audio, among other things. In this case, a JPG image was used.

The image storage is usually performed off-chain to limit transactional costs, and this was the case here, as the image was placed on the Pinata.cloud platform15.

The multimedia file is linked to the NFT through the URL contained in the metadata file, allowing digital token trading platforms to display the visual representation of the asset associated with the NFT. Like the metadata file, this file must be stored in its final location before the NFT is minted.

4.4. The NFT

After programming and deploying the smart contract on the blockchain, to create an NFT, it was necessary to first store both the multimedia file and the metadata file in an online repository (the types of storage for the different items associated with the NFT are addressed later). Then, it was necessary to execute the smart contract to link the metadata file to the NFT and complete the minting process, as shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Synthesis of the process of creating an NFT organized by items.

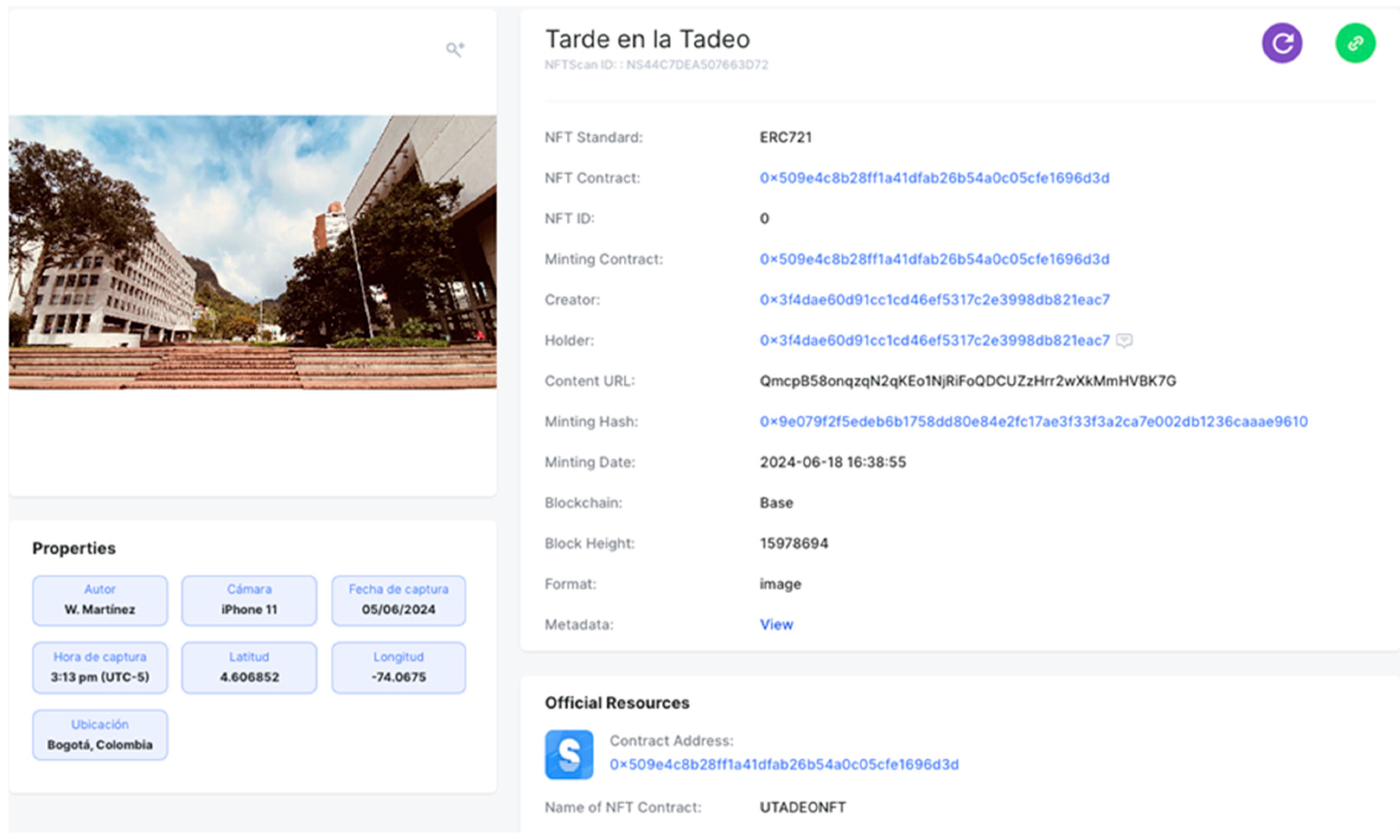

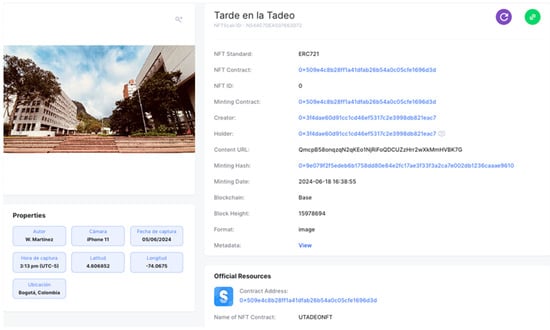

Once the NFT was minted, its creation could be validated on the blockchain16 through the contract address and its unique identifier (ID), as seen in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

Validation of the creation of the NFT.

As seen in the previous image, the data of the created NFT are as follows:

- Holder (owner): Corresponds to the public address of the NFT holder’s account. Ex.: 0x3F4Dae60d91cC1CD46Ef5317c2E3998DB821EAC7.

- Contract Address: Corresponds to the public address of the contract account with which the NFT was created. Ex.: 0x509e4c8b28ff1a41dfab26b54a0c05cfe1696d3d.

- Creator: Corresponds to the public address of the NFT creator. Ex.: 0x3F4Dae60d91cC1CD46Ef5317c2E3998DB821EAC7.

- NFT ID: Each NFT is assigned a consecutive number in the order of creation. However, to identify the NFT, this consecutive number must be associated with the contract identifier to which it belongs.

- NFT Standard: Ex. Model of the contract with which the contract was created, e.g., ERC-721. The standard allows importing a series of predefined functionalities for the minting and transfer of NFTs, as well as facilitating their visualization on different platforms.

What follows is an analysis of how the technical linkage between the token and the digital artwork is carried out to subsequently establish its legal recognition.

5. Linking the NFT to the Associated Asset

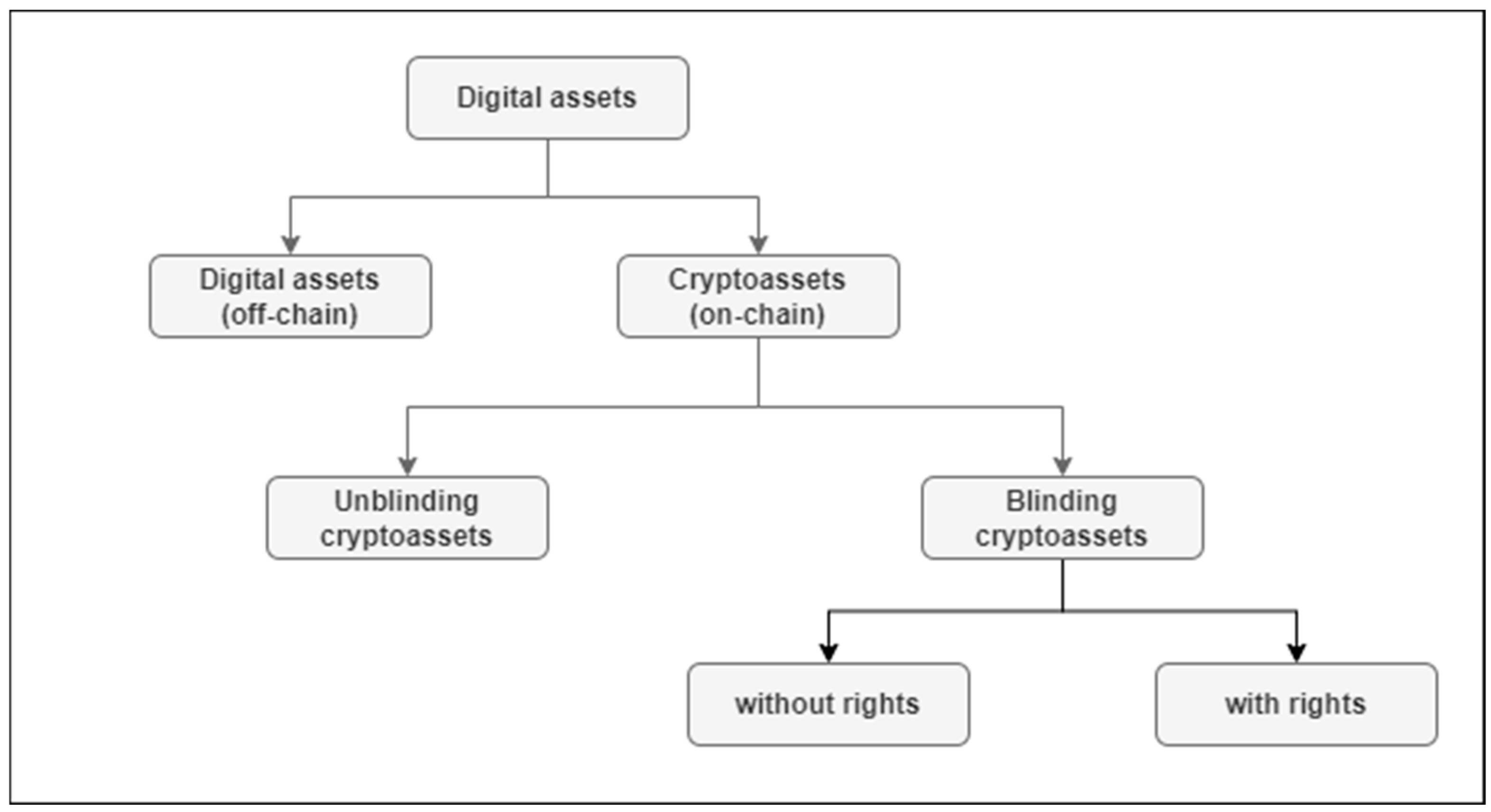

The first thing to clarify is that not all crypto-assets have an associated asset or service technically and legally. This is the case with cryptocurrencies, as they constitute an asset in themselves. However, some crypto-assets acquire value precisely because of their association with another asset, which can be digital or real-world. This linkage is made first from a technical perspective, but it requires legal validation to commercialize the goods and services backed by the blockchain.

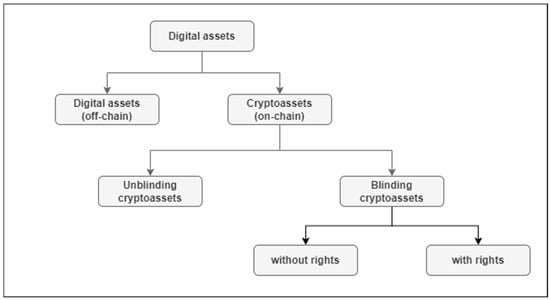

Therefore, it is essential to understand which crypto-assets have a linked asset and which are assets in themselves. To this end, a taxonomy of digital assets (see Figure 7) was created to make this distinction and subsequently analyze whether the holder of the asset also has rights over the linked assets.

Figure 7.

Taxonomy of digital assets.

As seen in Figure 7, there are digital assets outside the blockchain and others within it, known as crypto-assets. These types of digital assets can be associated with digital or real-world assets. Since the main objective of this article is to establish the challenges involved in linking an NFT to the associated asset (which for this study is a digital artwork), the following sections address the technical linkage to subsequently analyze its legal recognition.

5.1. Technical Linking of the Asset to the Non-Fungible Token (NFT)

An NFT is a unique electronic record associated with goods or services for commercialization. This capacity of NFTs to act as transactional objects arises, firstly, from the presence of a linked asset, and secondly, from the non-replaceable nature of the token, i.e., its non-fungibility. This characteristic “not only creates new commercial value but also very effectively protects the authenticity” (Dolganin 2021) of the incorporated asset.

Regarding linking, the first thing to clarify is the type of asset associated and its location. An NFT can have a digitally native asset or one from the real world associated with it. In both cases, the token establishes metadata fields to define the name, the description of the associated asset, the URL where a multimedia file representing the asset (if it is real-world), or the asset itself (if it is digital) that is hosted, as discussed in the previous section. This aspect is crucial for linking the asset with the token, as a detailed identification is required to avoid uncertainties about the asset and to legally satisfy the requirement for the determination of the object (nature and quantity) established in Article 1273 of the Spanish Civil Code17 and in many global legislations.

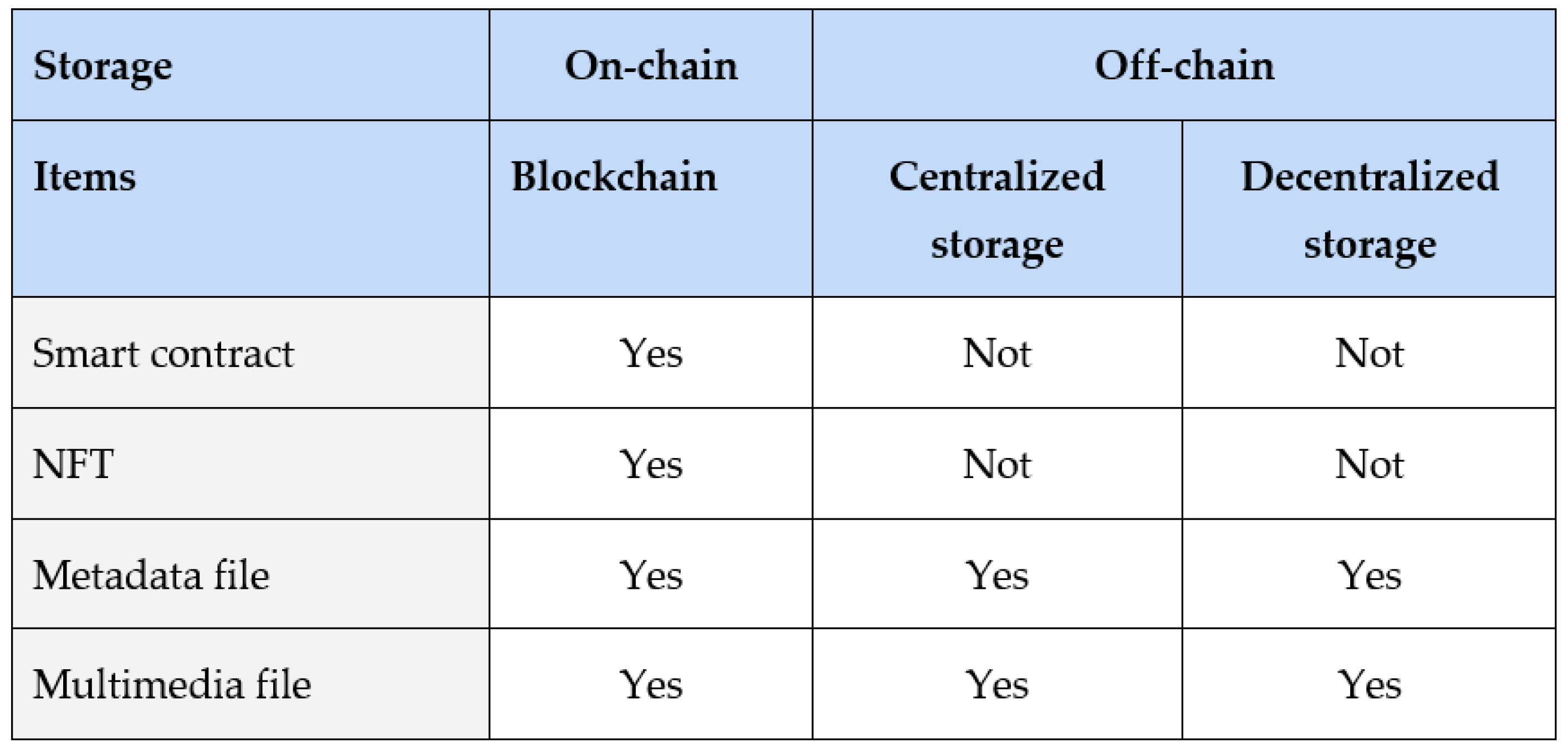

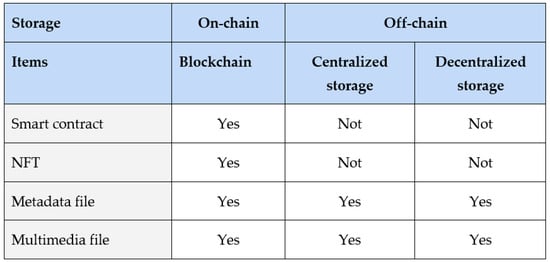

However, there is an ongoing debate about the reliability of linking assets with tokens, given that the data in these two files (metadata and multimedia) are not regularly found on the blockchain, where their persistence is guaranteed. Although these files can be stored directly on-chain, they are usually kept off-chain due to size limitations and transactional costs in most blockchains.

According to Balduf et al. (2022), the choice of storage impacts the immutability and persistence18 level of an NFT, causing more or less uncertainty for the acquirer depending on where the files are kept. This undoubtedly affects the commercialization of NFTs and their associated assets. Currently, the metadata file is usually stored externally, although it is technically viable to store it on-chain, as seen in Figure 8, if the creator is willing to pay the cost.

Figure 8.

Storage options for the different items of an NFT.

Thus, there are three types of storage: on-chain, off-chain centralized, and off-chain decentralized. Each is be analyzed below.

5.1.1. On-Chain Storage

In on-chain storage, the NFT’s metadata and multimedia file are directly recorded on the blockchain. The file’s integrity and availability are guaranteed as long as the underlying blockchain network remains intact and accessible. In this case, the work or asset is directly linked to the token, eliminating uncertainties about the removal or limitation of the use of the asset hosted off-chain since the digital element can continue to exist even if the original company no longer does (Fairfield 2022, p. 1283). The main drawback of this storage type is the high minting transaction costs, which currently discourage its use. Therefore, it is more common to store only the image metadata on the blockchain (Janesh s/o Rajkumar v Unknown person, 2022).

5.1.2. Off-Chain Decentralized Storage

In this option, the NFT’s metadata and multimedia file can be stored in a P2P19 network specialized in content distribution, such as Torrent. Networks like InterPlanetary File System (IPFS) and Arweave fall under this category (Balduf et al. 2022). Data storage, retrieval, and location are performed using their digital footprint (hash) instead of their name or location20. By using the hash as an identifier and locator simultaneously, it ensures that the file contents are unaltered because, if the content changes, the link is lost as the hash changes. This option is recommended for minting NFTs since it allows metadata and multimedia file storage without incurring significant registration costs and ensures their persistence.

5.1.3. Off-Chain Centralized Storage

This storage mode keeps the NFT’s metadata and multimedia file on traditional web servers or cloud hosting services like Amazon Web Services (AWS), Google Cloud Platform, or websites. The metadata file URL is included in the NFT’s blockchain information.

The problem with this type of storage is that the files linking the object are not inside the blockchain, so they can be deleted. This scenario could arise due to the cessation of the storage server company’s operations, server shutdown, data loss from cyberattacks, or the imposition of access restrictions by the server host. It could also be the case that the server host imposes restrictions on the NFT rights holder, preventing free access to the file. In such cases, there would be a token linked to a non-existent asset (when the asset is digitally native, like a digital artwork), or the data describing the object connected to the NFT would be unavailable (when it is a real-world object), thus losing all economic value and causing significant legal issues. This happened with NFTs minted by FTX when multimedia files became inaccessible (Reguerra 2022) after regulatory authorities blocked access to the website’s contents.

Of the three storage modes, on-chain storage clearly offers the most security for NFT acquirers since it does not rely on an external hosting service to maintain the acquired element. However, this practice is limited due to the small space and high cost of direct blockchain storage, and “only the smallest data bits can be stored and traded directly on the tokens” (Fairfield 2022).

In this project’s specific case, the metadata and multimedia files are stored using the off-chain decentralized service: Pinata.cloud.

5.2. Legal Linking of the Asset to the Non-Fungible Token (NFT)

As an NFT is a unique representation of a commercializable good or service on the blockchain, many legal challenges arise in this new form of exchange of goods and services. Indeed, significant aspects such as the copyright of digital artwork21, consumer protection22, the legal classification of the NFT, the transfer of the asset and its transferable rights, and the legal recognition of the smart contract, among others, pose substantial challenges for the law to address.

However, the primary legal challenge NFTs currently face is the legal recognition of the effects of the link between the token and the attached asset, as this is the only way any legal transaction with the NFT also affects the related object.

This legal effect of linking should be understood as broadly as possible. It includes the following statement: “any transaction with the digital asset affects the parties’ rights concerning the other asset and the effect of those transactions in case of insolvency” of one of the parties (UNIDROIT 2023).

This has economic significance because an NFT gains market value as it evidences the parties’ rights in a transaction or a person’s rights over an asset’s ownership. Therefore, it is necessary to differentiate the token from the rights incorporated in it. For instance, a Bitcoin has intrinsic value, but an NFT only has value as long as the person controlling the token also acquires the rights incorporated into it. Hence, the law must regulate the link between the token and the attached asset.

Thus, this section analyzes the legal challenges of linking the token to the attached assets (digital artwork), an issue of great importance, as it determines the legal viability of their commercialization.

Legal Recognition of the Link between the Asset and the Token

- Connecting Rights with Objects

The first complex scenario for understanding the link between the NFT and its underlying asset is the fact that the concept of ownership varies across different countries. Indeed, “When assessing views presented in different countries, it is important to note that legal systems differ considerably in terms of what is accepted as property, property right, or the object of property” (Kaisto et al. 2024, p. 4).

Therefore, the recognition of ownership contained in an NFT “depends on the characteristics of property in a given legal system and on crypto-assets matching those characteristics” (Kaisto et al. 2024, p. 4).

Despite this legal reality, the idea of connecting objects and rights involves nothing new as such. “Suffice it to refer to the history of various kinds of physical documents incorporating rights” (Rabinowitz 1956), such as securities or contracts. In this sense, “NFTs are merely a new technological medium” (Szostek 2019; Dutta 2020).

In any case, “if a token can be owned, then tokenisation, in the meaning discussed here, results in a kind of dualism”, since we have, on the one hand, the token and, on the other, the attached asset or right (Argelich 2022).

Some authors believe that the token should be separated from the attached rights, arguing that “owning a token must be systematically separated from the right represented by the token” (Argelich 2022; Savelyev 2018). However, given their close connection, we believe that an indissoluble relationship must be legally recognized.

This raises the following question: can the owner of a tangible thing link the ownership of the thing with an NFT so that the ownership of the thing belongs to the owner of the NFT?

The answer should be yes, as “if transfer of ownership is not subject to requirements of form, the owner of a thing is probably generally able to bring about transfer with the help of a token, so that ownership of the thing becomes acquired by the person who acquires ownership of the token” (Kaisto et al. 2024).

Regarding the laws in Finland, Kaisto et al. (2024) opine that it “is a plausible starting point, at least in Finland, for if transfer of ownership of an NFT includes intention to transfer ownership of a thing connected to the NFT, then this can be considered as a mode of transfer of ownership of the thing”.

This means that, undoubtedly, if the token is intended to be the technical and legal mechanism for transferring goods and rights, there must be legal recognition of the link between them. However, due to the diversity of legal systems, “it seems that creating a strong juridical connection between the ownership of an NFT and of a (material) thing would require special legislation in most legal systems” (Kaisto et al. 2024, p. 13).

Therefore, the link between the token and the assets is of particular interest in the transfer of rights, though there are other advantages that motivate the legal regulation of this connection. In the case of digital artworks, “the association with NFTs allows the authenticity of the issued copies to be certified and related exchanges to be tracked, as once registered, the tokens are immutable”. In this way, digital works are placed on the same level as physical or traditional artworks, “without the need for a third party to certify their origin and authenticity. Moreover, their transfer is facilitated in the same way as for tangible goods” (D’Alonzo 2024, p. 175).

Thus, NFTs are credited with introducing “the concepts of authenticity and effective digital ownership into the digital world and, particularly, into the blockchain system”, as it follows that “only a specific person can be deemed to be the owner” (D’Alonzo 2024, p. 175).

However, it should be noted that many NFTs incorporate intellectual property rights, and, therefore, acquiring the token does not necessarily grant proprietary rights over the work23, let alone the moral rights of the author24. Thus, the transfer of rights through the NFT25 “will involve a willingness of issuers to control strictly the use by buyers of any rights associated with an NFT” (D’Alonzo 2024, p. 175).

Ultimately, when ownership of an NFT over a work of art is transferred, “you can have possession of the object, but you might not have the copyright associated with that object. Copyright is not just a single right, but a collection of rights, and most of these rights are retained by the original creator of the work” (Mujević and Mujević 2023, p. 18).

- Linking the Asset and the Token

From a legal perspective, the NFT must have a direct link to the associated asset. Indeed, regardless of whether the object is tangible or intangible, there must be legal recognition linking the token to the asset, so the transfer of the former also implies a change in the ownership rights of the latter. This is known as the linking problem, addressing the extent to which a digital asset successfully embodies the “real-world” asset it represents, enabling various legally binding transactions with that asset (Allen et al. 2020). Therefore, it is crucial to understand and regulate the existence of the link, its requirements, and its legal effects (UNIDROIT 2023).

For this reason, the law must recognize (either through its regulation or through the autonomy of the parties) that the rights over the NFT and the linked asset are transferred synchronously. This is indeed “a common reason for linking a digital asset to another asset”, as this way, “transactions with the other asset are carried out by transferring the digital asset” (UNIDROIT 2023). This is one of the main objectives of asset tokenization, as it facilitates agile and secure commercialization of goods and services, allowing the “digital asset holder to alter a person’s rights concerning the other asset or concerning the person who issued it” (UNIDROIT 2023).

Thus, there are two main reasons for linking assets to the token: the first is to enable the token holder to alter a person’s rights with the linked asset, and the second is that the transfer of the token (NFT) must transfer the rights of the linked asset (UNIDROIT 2023).

Therefore, the relevant aspect of the legal effects of linking the token to the asset is precisely the “legal bridge between the token and its underlying asset” (Allen et al. 2020, p. 19). As most countries lack specific rules regulating this link, the analogy is made with figures such as negotiable instruments, public deeds of sale, and shares, among others. However, there are already legal bodies that directly regulate the creation, custody, and transfer of digital assets. Some address the link with the assets attached to the token, while others refer to internal regulations.

- Regulation of the Linkage in Domestic Laws

States must “ensure confidence in digital legal transactions, especially in the financial and economic sectors”. Additionally, they must protect users by providing “optimal framework conditions that are innovation-friendly and technologically neutral” (Liechtenstein Token and Trusted Technology Service Provider Act (TVTG), 2019). To achieve this, it is necessary to adopt modern legislation that regulates the creation, custody, and transfer of NFTs, as well as the representation of the rights incorporated into the token, the rights and obligations of service providers, and all civil law issues relating to tokens (Liechtenstein Token and Trusted Technology Service Provider Act (TVTG), 2019).

However, few states have internal regulations governing digital assets, including NFTs. Nonetheless, Liechtenstein, Malta, and Russia have enacted new laws that directly address the issue, while Japan and Switzerland have modified their existing regulations to ensure security in transactions with this new type of asset (Cavaller Vergés 2024).

- The Law Does Not Regulate the Linkage

Some specific regulations governing digital assets do not address the issue of linkage and refer the matter to another law. This is the case with Article 12 of the Uniform Commercial Code Amendments (Uniform Commercial Code Amendments 2022a), which states the following:

“Applicability of other law to the acquisition of rights. Except as provided in this section, a law other than that enshrined in this article determines whether a person acquires a right to a controllable electronic record and the right acquired by the person”.

Thus, another law will regulate the transfer of rights in an electronic record—in this case, an NFT—and this other law will define what acts must be performed to effect that transfer and the scope of the rights acquired (Uniform Commercial Code Amendments 2022a).

- The Law Addresses the Issue of Linkage

The state of Liechtenstein enacted the Token and VT Service Provider Act (TVTG) on 3 October 2019. Article 7 regulates the effects that the transfer of the token has on the associated rights or goods. This provision includes effects directly recognized by law and effects guaranteed by the person transferring the token. Both scenarios will be analyzed.

The main effect established by Liechtenstein law is the direct linkage between the token and the related asset, so any legal transaction carried out with the NFT will have an immediate effect on the linked asset. This is stipulated in Article 7.1: “Disposal over the Token results in the disposal over the right represented by the Token”.

This recognition provides legal certainty to the participants of any legal transaction involving the token, as there will be no doubts that the linked asset is also part of the negotiation, transferring the rights to the new holder.

However, Liechtenstein law warns that there are events where the law itself cannot recognize the linkage between the token and the associated asset, thus instituting the obligation of the token holder to guarantee such recognition through the autonomy of the will.

According to this, the first thing established is that the person obliged to transfer the token and its linked assets “must ensure, through suitable measures”, that “the disposal over a Token directly or indirectly results in the disposal over the represented right” (Liechtenstein Token and Trusted Technology Service Provider Act (TVTG), 2019).

These suitable measures referred to by the law involve the contractual recognition of such linkage, whereby the token holder guarantees that transferring the token implies transferring the asset and its linked rights by virtue of the party autonomy. However, it is recommended that this contractual manifestation be included in the metadata file, specifically in a file called the “rights file”, so that the proof of this manifestation is embedded in the smart contract (Liechtenstein Token and Trusted Technology Service Provider Act (TVTG), 2019).

Unfortunately, the direct recognition of the linkage between the token and the related asset has not been established in many internal regulations, despite the fact that—as mentioned above—there are already legal bodies that regulate NFTs, but for various reasons, they have not been established or taken a position regarding said link.

That is why, for states that have not yet regulated digital assets (specifically NFTs), or even those that have already regulated them but have not addressed the issue of tying, it is recommended that there be a direct and clear legal recognition between the token and the linked asset in such a way that, legally, one incorporates the other, thus allowing its commercialization in an agile and secure manner. However, it is clear that the linking of rights is different in many countries; such is the case of securities, or even the contracts themselves. That is why each state must recognize the legal link between the token and the asset according to its particularities, although it advocates broad recognition.

- Regulation of the Linkage in Uniform Laws

- -

- UNIDROIT Principles on Digital Assets

The UNIDROIT Principles on Digital Assets were created to increase predictability and certainty in private law matters related to digital assets (UNIDROIT 2023). They constitute a body of soft law since they do not originate from a proper legislative body and therefore “are not binding and do not have coercive force” (Cavaller Vergés 2024), but they are included in the agreement through the autonomy of the will of the parties.

Principle 4 addresses the issue of the linkage of the token with the asset as follows:

“The digital assets to which these Principles apply include a digital asset linked to another asset. The other asset may be tangible or intangible (including another digital asset). Other law applies to determine the existence of, requirements for, and legal effect of any link between the digital asset and the other asset, including the effect of a transfer of the digital asset on the other asset” (UNIDROIT 2023).

According to the above, Principle 4 acknowledges that there are native assets and others linked to another asset. However, it does not regulate the linkage or the legal effects of such linkage, as this is left to an internal law. This state law regulating the linkage may be a pre-existing rule or a modern law directly regulating digital assets, such as the already studied Liechtenstein law. The legal recognition of the linkage will vary depending on the applicable legislation (UNIDROIT 2023).

A key aspect clarified by the drafters of the Principles is that the parties involved in an NFT transaction “cannot confer any greater legal effect on the link than the other law of the State would allow” (UNIDROIT 2023). Therefore, the limit to the autonomy of the will regarding the linkage cannot contradict the national law governing the transaction with the token. Thus, if the internal law does not allow it, a contractual agreement may be insufficient to recognize that transferring the token means transferring the linked asset, as the internal law must necessarily endorse this agreement. This is because the Principles unfortunately do not establish a direct regulation of the linkage and leave it to another national law.

- -

- Regulation (EU) 2023/1114 on Markets in Crypto-Assets (MiCA)

On 31 May 2023, the European Regulation 2023/1114 concerning markets in crypto-assets, known as “MiCA” (Markets in Crypto-Assets), was officially adopted after years of intense debates over the regulation of crypto-assets in the European Union. This Regulation amends Regulations (EU) No. 1093/2010 and (EU) No. 1095/2010 and Directives 2013/36/EU and (EU) 2019/1937, marking a significant regulatory revolution as it pioneers the global regulation of crypto-assets.

The Regulation reflects “the efforts of lawmakers to regulate basic digital representants of value or rights that may be shared or stored electronically by the use of distributed ledger technology (‘DLT’) or any kind of analogy thereof” (Bočánek 2021, p. 40), like blockchain technology.

The primary aim of MiCA is to establish a comprehensive legal framework for crypto-assets within the EU, incorporating some of the best practices already present in financial market regulations and applying them to the cryptocurrency industry.

The core structure of the regulatory framework under MiCA corresponds to the four main objectives of the regulation: legal certainty and clarity, support for innovation and fair competition, consumer and investor protection, and market integrity and financial stability. “The main elements and tools of the framework are built around the unified notion of crypto-assets, the authorisation regime, and a new standard for consumer and investor protection in the sector” (Divissenko 2023, p. 673).

To properly understand this Regulation, it is necessary to clarify which types of digital assets it targets. MiCA provides an autonomous definition of crypto-assets in Article 3: “Crypto-asset means a digital representation of a value or of a right that is able to be transferred and stored electronically using distributed ledger technology or similar technology”.

- Digital Assets Included in MiCA

The new instrument establishes three types of crypto-assets that are broadly defined to encompass multiple options within each category (Patz and Wettlaufer 2022). However, the established classification is based on the premise that each type has distinct characteristics that differentiate them from one another. Notably, “the risk involved in their trading” is one of the primary aspects that characterize them. Additionally, this classification considers whether the crypto-assets “aim to stabilise their value by referencing the value of other assets” (Chiu 2021, pp. 19–21; Alvarado Herrera 2022; Pérez Marín 2023), as established in Recital 18 of MiCA.

The types of crypto-assets regulated by the Regulation are reduced to the following three:

- The first type consists of crypto-assets that aim to stabilize their value by referencing only one official currency. The function of such crypto-assets is very similar to the function of electronic money, as defined in Directive 2009/110/EC. Like electronic money, such crypto-assets are electronic surrogates for coins and banknotes and are likely to be used for making payments. Those crypto-assets should be defined in this Regulation as “e-money tokens”.

- The second type of crypto-assets refers to “asset-referenced tokens”, which are a type of crypto-asset that is not an electronic money token and that aims to maintain a stable value by referencing another security or right, or a combination thereof, including one or more official currencies. This second type covers all other crypto-assets, other than electronic money tokens, whose value is backed by assets, to prevent circumvention and make this Regulation future-proof (Bočánek 2021, p. 40).

- The third and final type consists of crypto-assets that differ from the aforementioned asset-referenced tokens and e-money tokens and encompasses a wide variety of crypto-assets, including utility tokens.

Next, we analyze whether NFTs are included in this classification.

- MiCA and NFTs

It is crucial to understand the scope of the three types of crypto-assets covered by the Regulation to answer the following question: are NFTs part of the crypto-assets regulated by MiCA?

The answer is complex, as NFTs are initially directly excluded from the scope of the regulation. However, there are some NFTs with specific characteristics that could be included under the Regulation. Indeed, although Article 3 provides a broad definition of crypto-assets that covers most existing digital assets, both Recital 10 of the Regulation and Article 2.3 unfortunately exclude non-fungible tokens (NFTs) from their scope. Recital 10 states the following:

“This Regulation should not apply to crypto-assets that are unique and not fungible with other crypto-assets, including digital art and collectibles. The value of such unique and non-fungible crypto-assets is attributable to each crypto-asset’s unique characteristics and the utility it gives to the holder of the token. Nor should this Regulation apply to crypto-assets representing services or physical assets that are unique and non-fungible, such as product guarantees or real estate”. “Such features limit the extent to which those crypto-assets can have a financial use, thus limiting risks to holders and the financial system and justifying their exclusion from the scope of this Regulation”.

This recital leaves no doubt that NFTs are indeed excluded from MiCA and explains the reasons for their exclusion from its scope.

Article 2.3 also states, “This Regulation does not apply to crypto-assets that are unique and not fungible with other crypto-assets”.

Thus, both Recital 10 and Article 2.3 of MiCA make it clear that NFTs, due to their unique characteristics, are not regulated by the Regulation. However, Recital 11 opens the door for some non-fungible tokens to be regulated under this Regulation:

“The fractional parts of a unique and non-fungible crypto-asset should not be considered unique and non-fungible. The issuance of crypto-assets as non-fungible tokens in a large series or collection should be considered an indicator of their fungibility. The mere attribution of a unique identifier to a crypto-asset is not, in and of itself, sufficient to classify it as unique and non-fungible. The assets or rights represented should also be unique and non-fungible in order for the crypto-asset to be considered unique and non-fungible”.

“The exclusion of crypto-assets that are unique and non-fungible from the scope of this Regulation is without prejudice to the qualification of such crypto-assets as financial instruments. This Regulation should also apply to crypto-assets that appear to be unique and non-fungible, but whose de facto features or whose features that are linked to their de facto uses would make them either fungible or not unique”.

According to these two recitals and Article 2.3, the following can be concluded:

- Unique and indivisible NFTs, such as the digital art analyzed in this article, will not be subject to MiCA regulation, as they are unique and not fungible with other crypto-assets and are directly excluded by the Regulation in its Article 2.3.

- Divisible NFTs, such as fractions of a unique and non-fungible crypto-asset, will not be considered non-fungible digital assets, given that their issuance as a series will be an indicator of their fungibility, like those representing fractional underlying assets. Therefore, this type of asset will be subject to MiCA regulation.

Despite the above, MiCA does not address the regulation of the link between NFTs (included within its scope) and their underlying asset, just as the UNIDROIT Principles on Digital Assets do not regulate this aspect either.

Therefore, MiCA is a significant step in regulating crypto-assets in the European Union, but it not only excludes the majority of NFTs but also fails to cover important legal aspects, such as the connection between the token and the underlying asset.

6. Conclusions

This project analyzes the technical and legal linkage of an NFT with its associated asset, aiming to create a more adaptable, secure, and efficient system for the transfer and management of rights through NFTs.

Implementing these improvements will make the smart contract not only technologically advanced and secure but also legally robust and adaptable to the various needs of linking assets to an NFT.

The main improvements that this article proposes regarding the smart contract are the following: (1) Establish in the metadata file the bridge between the token and the underlying asset through the correct identification of the attached asset. This identification is made with the inclusion of descriptive data and the location of the good. (2) It is recommended to attach a media file containing the image or video of the underlying asset. (3) This multimedia file should not be on the blockchain due to its high costs, but decentralized off-chain storage is recommended for the ideal protection of the information. (4) Add other relevant data in the “Attributes” section, such as features and values corresponding to the attached good, for example, color, rarity, edition number, or other unique characteristics of a work or good. (5) It is transcendental to include a rights file in the metadata file, where all relevant aspects of the NFT are established.

According to the above, it is essential that both technical innovations and legal considerations harmoniously integrate to ensure the project’s success and acceptance in an increasingly digitized and regulated environment.

Undoubtedly, the most important challenge posed by asset tokenization is the linkage of the token with the associated asset. This linkage implies that any legal transaction involving the NFT will have the same legal consequences concerning the linked asset. Currently, there is no widespread recognition of this linkage, but some internal and conventional legal norms address the issue. Therefore, states should be encouraged to make an autonomous legal recognition in their internal laws that includes at least the following aspects:

- The law must endorse that the transfer of tokens also entails the transfer of linked assets and rights (UNIDROIT 2023).

- This transfer must be enforceable against third parties, for example, in the case of an attachment in an executive process. In any case, for such enforceability to exist, the following requirements must be met: (a) if the transfer was activated in the system (blockchain) before the start of the judicial process; and (b) if activated after the start of the process “and was executed on the day the process was initiated, provided the accepting party demonstrates that they were unaware of the process initiation or would have remained unaware with the exercise of due diligence” (Liechtenstein Legal Gazette 2019).

- If the law does not recognize that the transfer of the token automatically results in the transfer of the linked asset, the person transferring the token must ensure such synchronous transfer. This must be expressly stated in the agreement.

- The person transferring the token must also guarantee that there is no other concurrent legal transaction with the same asset.

- The smart contract must identify who is obligated and who is the creditor of the obligation contained in the token. Therefore, the debtor will only be released when the performance established in the blockchain is executed in favor of the person identified in the system as the creditor (Liechtenstein Legal Gazette 2019).

- Ultimately, as suggested by the Liechtenstein Token and VT Service Provider Act (2019) on 3 October 2019, the law should consider that “the ‘token’ is a kind of ‘container’ in which a right is incorporated, so that transactions conducted with the token are considered to be conducted with the asset or rights associated with it”. This is established in article 7: “Disposal over the Token results in the disposal over the right represented by the Token”. Por tal motivo, esta ley debe servir de guía para futuras regulaciones sobre este aspecto.

Author Contributions

The authors (W.F.M.L., A.M.M.B. and E.J.R.D.) have contributed equally to the article in all the aspects considered. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Jorge Tadeo Lozano University.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article and the references.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Allen, Jason, Michel Rauchs, Apolline Blandin, and Keit Bear. 2020. Legal and Regulatory Considerations for Digital Assets. CCAF Publications, p. 20. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3712888 (accessed on 22 October 2023).

- Alvarado Herrera, Lucía. 2022. Los criptoactivos con función de pago: Criptomonedas estables y sistemas de pago a la luz de la propuesta del reglamento relativo a los mercados de criptoactivos (MICA). In Derecho Digital y Nuevas Tecnologías. Edited by Maria Jesús Blanco Sánchez y A. Madrid Parra. Cizur Menor: Thomsom-Reuters Aranzadi, pp. 857–88. [Google Scholar]

- Argelich, Cristina. 2022. Smart Property and Smart Contracts Under Spanish Law in the European Context, 30. European Review of Private Law 215: 226. [Google Scholar]

- Balduf, Leonhard, Martin Florian, and Björn Scheuermann. 2022. Dude, where’s my NFT? Distributed Infrastructures for Digital Art. Paper presented at 3rd International Workshop on Distributed Infrastructure for the Common Good (DICG’22), Quebec City, QC, Canada, November 8. [Google Scholar]

- Bamakan, Seyed, Nasim Nezhadsistani, Omid Bodaghi, and Qiang Qu. 2022. Patents and intellectual property assets as non-fungible tokens; Key technologies and challenges. Scientific Reports 12: 2178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bočánek, Marek. 2021. First draft of crypto-asset regulation (mica) with the European Union and potential implementation. Financial Law Review 22: 40. [Google Scholar]

- Cavaller Vergés, Misericordia. 2024. En Busca de un Marco Legal para los Activos Digitales: Los Principios Unidroit Sobre Activos Digitales y Derecho Privado. Madrid: Cuadernos de Derecho Transnacional, vol. 16, pp. 113–30. [Google Scholar]

- Chiu, Iris. 2021. Regulating the Cripto Economy. Business Transformation and Financialisation. Oxford: Hart Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- D’Alonzo, Claudio. 2024. Legal Issues About NFTs. Academic Journal of Interdisciplinary Studies 13: 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Divissenko, Nikita. 2023. Regulation of Crypto-assets in the EU: Future-proofing the Regulation of Innovation in Digital Finance. European Papers 8: 665–87. [Google Scholar]

- Dolganin, Alexander. 2021. Non-fungible tokens (NFT) and intellectual property: The triumph of the proprietary approach? Digital Law Journal 2: 46–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutta, Saurav. 2020. The Definitive Guide to Blockchain for Accounting and Business: Understanding the Revolutionary Technology. Bingley: Emerald Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Entriken, William, Dieter Shirley, Jacob Evans, and Nastassia Sachs. 2018. ERC-721: Non-Fungible Token Standard. Available online: https://eips.ethereum.org/EIPS/eip-721 (accessed on 14 July 2023).

- Fairfield, Joshua. 2022. Tokenized: The Law of Non-Fungible Tokens and Unique Digital Property. Indiana Law Journal 97: 1283. [Google Scholar]

- Gong, Eric, and Yu Sun. 2022. Computerbank: A community-based computer donation platform using machine learning and nft. Computer Science & Information Technology 12: 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guidi, Barbara, and Andrea Michienzi. 2023. From NFT 1.0 to NFT 2.0: A Review of the Evolution of Non-Fungible Tokens. Future Internet 15: 189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gámez, Maria, and Jorge Corredor. 2023. NFT (token no fungibles) y sus implicaciones en el mercado de valores. Derecho PUCP 90: 529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaisto, Janne, Teemu Juutilainen, and Joona Kauranen. 2024. Non-fungible tokens, tokenization, and ownership. Computer Law & Security Review 54: 105996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karandikar, Nikita, Antorweeb Chakravorty, and Chunming Rong. 2021. Blockchain based transaction system with fungible and non-fungible tokens for a community-based energy infrastructure. Sensors 21: 3822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liechtenstein Legal Gazette. 2019. Law of 03 October 2019 on Tokens and TT Service Providers (Token and TT Service Provider Act; TVTG). No. 301. Available online: https://www.regierung.li/files/medienarchiv/950-6-01-09-2021-en.pdf (accessed on 19 April 2024).

- Madine , Mohammad, Khaled Salah, Raja Jayaraman, Ammar Battah, Haya Hasan, and Ibrar Yaqoob. 2022. Blockchain and nfts for time-bound access and monetization of private data. IEEE Access 10: 94186–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malta Digital Innovation Authority Act. 2018. Chapter 59. Available online: https://legislation.mt/eli/cap/591/eng (accessed on 2 March 2024).

- Mujević, Belma, and Mersad Mujević. 2023. NFTs and copyright law. SCIENCE International Journal 2: 15–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OpenSea. 2023. Estándares de Metadatos. Available online: https://docs.opensea.io/docs/metadata-standards (accessed on 14 March 2024).

- Pacheco, Maria. 2019. De la tecnología blockchain a la economía del token. Revista de la Facultad de Derecho 83: 82. [Google Scholar]

- Patz, Anika. Y., and Jan Wettlaufer. 2022. E-Money Tokens, Stablecoins and Token Payment Services en Maume/Maute/Fromberger (Dirs.), The Law of Crypto Assets. A Handbook. München: Beck-Nomos-Hart, pp. 242–68. [Google Scholar]

- Putnings, Markus. 2022. Non-fungible token (nft) in the academic and open access publishing environment: Considerations towards science-friendly scenarios. The Journal of Electronic Publishing 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez Marín, Maria. 2023. El reglamento MiCA: Responsabilidad y sanción frente al incumplimiento de la regulación del mercado de criptoactivos. IUS ET SCIENTIA 9: 2. [Google Scholar]

- Rabinowitz, Jacob. 1956. The Origin of the Negotiable Promissory Note. University of Pennsylvania Law Review 104: 927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Rath, Ashish. 2023. Tokenization of Rental Real Estate Assets Using Blockchain Technology. Available online: https://www.researchsquare.com/article/rs-3004275/v1 (accessed on 23 July 2024).

- Reguerra, E. 2022. NFT Acuñados en FTX ya no son Visibles, lo que Saca a Relucir los Fallos del Alojamiento en la Web 2.0. Cointelegraph. Available online: https://es.cointelegraph.com/news/nfts-minted-on-ftx-break-highlighting-web2-hosting-flaws (accessed on 23 July 2024).

- Savelyev, Alexander. 2018. Some Risks of Tokenization and Blockchainizaition of Private Law. Computer Law & Security Review 34: 863. [Google Scholar]

- Shah, Kaushal, Uday Khokhariya, and Saumya Patel. 2023. Smart contract-based dynamic non-fungible tokens generation system. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szostek, Dariusz. 2019. Blockchain and the Law. Baden-Baden: Nomos Verlagsgesellschaft. [Google Scholar]

- Tönnissen, Stefan, Jan Beinke, and Frank Teuteberg. 2020. Understanding token-based ecosystems—A taxonomy of blockchain-based business models of start-ups. Electronic Markets 30: 307–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNIDROIT. 2023. Principles on Digital Assets and Private Law. Governing Council. p. 26. Available online: https://www.unidroit.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/01/Principles-on-Digital-Assets-and-Private-Law-linked.pdf (accessed on 2 May 2024).

- Uniform Commercial Code Amendments. 2022a. Uniform Law Commission and the American Law Institute, Controlable Electronic Records. Available online: https://www.restructuring-globalview.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/21/2023/10/UCC-Amendments_2022_Final-Act-with-Comments_8-1.pdf (accessed on 26 August 2024).

- Uniform Commercial Code Amendments. 2022b. Uniform Law Commission and the American Law Institute, Article 12, Controlable Electronic Records. Prefatory Note to Article 12, pg. 229–34. Available online: https://www.restructuring-globalview.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/21/2023/10/UCC-Amendments_2022_Final-Act-with-Comments_8-1.pdf (accessed on 26 August 2024).

- Valeonti, Foteini, Antonis Bikakis, Melissa Terras, Chris Speed, Andrew Hudson-Smith, and Konstantinos Chalkias. 2021. Crypto collectibles, museum funding and openglam: Challenges, opportunities and the potential of non-fungible tokens (NFTs). Applied Sciences 11: 9931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Qin, Rujia Li, Qi Wang, and Shiping Chen. 2021. Non-Fungible Token (NFT): Overview, Evaluation, Opportunities and Challenges. arXiv arXiv:2105.07447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarifis, Alex, and Xusen Cheng. 2022. The business models of NFTs and fan tokens and how they build trust. Journal of Electronic Business & Digital Economics 1: 138–51. [Google Scholar]

| 1 | See, Janesh s/o Rajkumar v Unknown person, 2022. |

| 2 | Tokens are defined by Article 2 of Law of 3 October 2019 on Tokens and TT Service Providers (Token and TT Service Provider Act; TVTG): “Token: a piece of information on a TT System which: 1. can represent claims or rights of memberships against a person, rights to property or other absolute or relative rights; and 2. is assigned to one or more TT Identifiers”. |

| 3 | “The Ethereum protocol was originally conceived as an improved version of the Bitcoin cryptocurrency, to overcome the limitations of its programming language, providing advanced features such as blockchain custody, withdrawal limits, financial contracts, gambling market and the like. through a very generalized programming language”, vid. (Pacheco 2019, p. 82). |

| 4 | Although the term “smart contract” seems linked to a legal notion, it is actually a misnamed technical concept that describes the automation of terms written in computer code, as will be seen later. |

| 5 | Real World Assets (RWAs). |

| 6 | NFTs have seen a notable increase in popularity in various fields, such as decentralized finance and the art world, thanks to trading platforms such as OpenSea, Rarible, and SuperRare, which have facilitated digital art transactions. |

| 7 | The Smart contract is defined by the (Malta Digital Innovation Authority Act 2018) as “innovative technology arrangement consisting of: (a) a computer protocol; and, or (b) an agreement concluded wholly or partly in an electronic form which is automatable and enforceable by execution of computer code, although some parts may require human input and control and which may be also enforceable by ordinary legal methods or by a mixture of both”. |

| 8 | A standard is a smart contract model; in this case, it is one that is used to create tokens. |

| 9 | Process of activating and carrying out the functions and logic programmed within the code. |

| 10 | Translated into machine language. |

| 11 | Publish and run code. |

| 12 | https://www.base.org/ (accessed on 18 May 2024). |

| 13 | A web page that allows you to consult information registered in the blockchain. |

| 14 | https://basescan.org/address/0x509e4c8B28fF1A41dfAb26b54a0C05CFE1696d3d (accessed on 21 May 2024). |

| 15 | https://www.pinata.cloud/ (accessed on 12 April 2024). |

| 16 | https://base.nftscan.com/0x509e4c8B28fF1A41dfAb26b54a0C05CFE1696d3d/0 (accessed on 5 April 2024). |

| 17 | “The subject matter of any contract shall be an object determined as to its species. The fact the amount is indeterminate shall not prevent the existence of a contract, provided that it is possible to determine it without the need for a new covenant with the contracting parties”. |

| 18 | In the digital context, persistence implies the quality of a file or set of digital data to remain constant and durable over time. |

| 19 | A P2P network, which stands for “Peer-to-Peer”, is a type of decentralized network in which individual nodes (or “peers”) have the ability to communicate directly with each other without depending on a central server. In a P2P network, each node has roles as both a provider and consumer of resources. |

| 20 | https://ipfs.tech/ (accessed on 20 May 2024). |

| 21 | The following sentences can be seen on this matter: Nike, Inc., v. StockX LLC de 1 September 2023; Yuga Labs, Inc., v. Ripps, 21 April 2023. |

| 22 | See Hermès International and Hermès of Paris, Inc., v. Mason Rothschild. “Defendant’s entire scheme here was to defraud consumers into believing, by his use of variations on Hermes’ trademarks that Hermes was endorsing his lucrative MetaBirkins NFTs”. |

| 23 | See Juventus F.C. v. plataforma de blockchain “Blockeras”. |

| 24 | Visual (Entidad de Gestión de Artistas Plásticos) v. Mango Group. “Converting a work of art into an NFT meant a modification of the work that could affect the rights of its author”. |

| 25 | Jeeun Friel, individually and on behalf of all others similarly situated, Plaintiff, v. Dapper Labs, Inc., and Roham Gharegozlou. “Southern District of New York Refuses to Dismiss Purported Class Action Lawsuit Against Blockchain Technology Company, Holding Non-Fungible Tokens Were Correctly Purported ‘Securities’”. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).