Abstract

The following paper is devoted to research on the types of forms of skyscrapers built in Warsaw from 1989 to 2022. The research focuses on defining the architectural typology of such forms as elements of the image of the city. The research was carried out in the following stages: defining the character of international examples of skyscrapers, research on types of forms of high-rise buildings realized in Warsaw and their formal classification, determination of typological features of twenty-four high-rise buildings under study, and their changes over time. The characteristic elements of the image of the city and urban composition related to the examined buildings were determined. As a result of the research, it was determined that the most common types of forms found in the study group were free forms—41.6%, polygonal forms—25%, and obelisk forms—20.8%. In individual cases, there are tapered, aerodynamic, and regional forms. The research showed a trend in the latest projects, dating back to the last five years, consisting of an increase in the number of buildings constructed, an increase their scale, a lowering of their slenderness, and a tendency to implement polygonal forms more often than free forms. High-rise buildings are landmarks in the urban composition and the image of Warsaw. Most often, they designate paths and nodes with which they are associated. The types of forms of high-rise buildings in Warsaw vary; there is no uniform type of form of high-rise building implemented in the period. For this reason, the research should be updated and carried out using the methodology presented in the paper.

1. Introduction

1.1. Topic

A special feature of the image of Warsaw, which developed in the period between 1989 and 2022, is the large number of completed skyscrapers. This distinguishes it from the buildings of other Central European capitals [1]. Therefore, this situation is the subject of scientific research. In this respect, the analysis of Warsaw’s high-rise buildings has been the subject of scientific work related to the presence of tall and high-rise buildings as elements of the urban and spatial structure [2,3,4], or forms indicating the shift of the center of Warsaw towards the Wola district, which is marked by skyscrapers buildings [5]. Research has also been conducted on the relationship between high-rise buildings and nearby public spaces [6].

The topic of the paper is the analysis of the types of the form of high-rise buildings built in Warsaw in the years 1989–2022. The year 1989 was chosen as the turning point for new opportunities, combined with access to techniques and methods of building high-rise buildings, which is related to the beginning of the political transformation in Poland. The scale of the buildings was defined as a minimum of one hundred meters in height. This is the height that is recognized in the literature as meaning buildings called skyscrapers [7,8]. This scale was adopted due to its characteristic significant impact on the city, which takes place both on the program level (due to a large number of users of these buildings) and a spatial level, as elements determining the features of the city’s image, e.g., roads, edges, areas, nodes, landmarks [9,10] or urban markers, lines, border lanes, and streets [11].

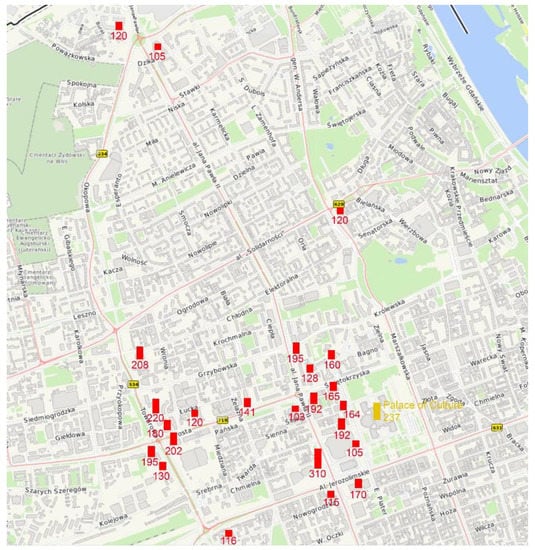

In the period analyzed—the years 1989–2022—a total number of 24 buildings exceeding a height of one hundred meters were completed in Warsaw. These are grouped mainly in the central area of Warsaw—Śródmieście—and in the western part of the Wola district, with individual cases of implementation in the Żoliborz district. The locations of the studied objects are shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Location of the examined high-rise buildings. Their total height is given under the building symbols. Source: author’s study.

1.2. Research Purpose

During the period analyzed, the city implemented a procedure for examining the influence of the above skyscrapers on the city’s silhouette. The adoption of this procedure was related to the intention to protect the view of the Old Town in Warsaw, which is inscribed on the UNESCO World Heritage List [12,13]. Although the location and scale of the buildings have been the subject of research and consultations, the buildings constructed in Warsaw have never been studied in terms of the types of forms used in the projects. Thus, it can be seen that there is a gap in the research on high-rise buildings carried out in Warsaw, which this paper attempts to fill. The goal of the study is to answer the question of whether there is a specific type of form of skyscraper building that has been built in Warsaw since 1989. The answer to this question is related to the current discussion in the community of Varsovian city planners and architects, during which, hypotheses related to a specific pattern of high-rise buildings that is supposed to be characteristic of Warsaw are often made. Among Varsovian decision-makers, designers, and publicists, the most common view is that the skyscraper characteristic of Warsaw has an orthogonal form, with a minimal or no podium. Many voices indicate that this form of the building is a local characteristic of a high-rise building in Warsaw. In the author’s opinion, this discussion should be conducted on the basis of thorough analysis and research.

The following research questions guided the creation of this work:

- -

- Are the forms in Warsaw unique, compared to the typical forms of skyscrapers built globally, e.g., due to regional features?

- -

- What types of forms are most often built among Varsovian skyscrapers? Is there any dominant type? Has there been variation in the construction of certain types of forms and can there be a change of trend in this respect?

- -

- What parameters of forms among the types of forms are most often used in Warsaw? For example, a building with a podium, characteristic slenderness, height?

The author’s working thesis, which was the basis of the work, is that there are common, dominant parameters of the skyscrapers built in Warsaw that should be distinguished, but that the form of the Varsovian skyscraper does not differ from global experience.

The aim of the following research is consequently to assess the occurrence of common parameters of forms that can be considered characteristic of the group of tested skyscrapers. An additional goal of the work is to develop a methodology for assessing the types of forms of high-rise buildings that can be used universally: for groups of buildings located in other places or for future examining or updating of the typology of skyscrapers built in Warsaw over time.

1.3. The Form of a High-Rise Building in the Image of the City

A skyscraper has a significant impact on the city, both functionally and visually. Both of these factors are related to the scale of the building. The first one is associated with a large number of users who use these buildings, which generates traffic in the public space and provides a large amount of space for various purposes—from service, e.g., offices, hotels, and retail to residential; the second is role that high-rise buildings play in creating the image of the city. Al-Kodmany K. [14,15] points to the unique potential of high-rise buildings in creating places (placemaking) that are recognizable, due to both of the above factors, in the scale of the entire metropolis.

Musiał R. defines the role of a high-rise building in the multidimensional shaping of the city landscape [2] as (1) an element of an urban composition, (2) an element of a spatial structure acting directly on the observer through its strong form, (3) as a characteristic sign, and (4) as an element of the urban environment. The location and exposition of the object, as well as its form—its scale and type of form—play a major role in this process.

High-rise buildings play a special role in shaping the image of the city skyline, which, thanks to them, is often a recognizable landmark of the metropolis. Many scientific studies have been devoted to this role [16,17,18,19]. The role of skyscraper form in this respect depends primarily on the factors related to the location of the buildings. The location of buildings may determine the panorama in selected areas of the city, e.g., central, designated districts, or places distinguished in terms of urban planning. Recognition of the form of skyscrapers in the panorama depends on the distance of panorama observation (from further perspectives, the details of the form are indistinguishable and the height plays a key role) and the mutual location of buildings in relation to each other (high-rise buildings located close to each other visually merge into one object in further perspectives).

According to theories relating to the legibility and imagery of the urban environment—Lynch K. [9,10] and Wejchert K. [11]—high-rise buildings have a natural potential to determine the components of a city’s image and urban composition. According to the studies of Gyurkovich J. [20,21,22,23], tall buildings, including high-rise buildings, are naturally strong forms that are important for the legibility of complex spatial structures. Readability and scale are features of high-rise buildings that, from various vantage points, help users create mental maps of the city [16].

Apart from the above-mentioned influence of high-rise buildings on the image of the city, Jasiński A. [24] points to the symbolic role of high-rise buildings, which may refer to the prestige, economic vitality, and aspirations of the metropolis, and even—in the case of the new WTC completed in New York City—its memory.

Lynch’s theory of the potential of high-rise buildings as landmarks was continued in the empirical work of Appleyard [25,26] and Evans et al. [27] The research shows that apart from scale, shape plays a significant role in creating the imageability of a high-rise building. The condition for a high-rise building is to create a visible element of the image of a city. Buildings that can be observed as a whole have a chance to exist more strongly in the mental map of the city’s inhabitants. Similarly, there is a difference in the perception of high-rise buildings with a podium, often connected with neighboring buildings in a row of buildings, and without this podium. Buildings without a podium more easily become noticeable landmarks, especially in locations where such buildings are visible and placed amongst existing buildings. The feature of a podium and its possible connection with the neighboring buildings is one of the ways of adjusting the form of a high-rise building to the context in which it is created, as the podium is often made at a scale that refers to the height of the neighboring buildings.

1.4. Typological Features of High-Rise Buildings Influencing Their Reception

The typological features that are the basis for the classification of this paper are architectural and urban types. Their selection is focused on defining a typology serving to categorize building forms in terms of their operation as objects involved in shaping the image of the city and urban composition, in line with the theories of Lynch K. [9,10] and Wejchert K. [11]. According to studies by Appleyard [25,26] and Evans et. al. [27], the following factors related to the form of a building, affecting its perception, can be distinguished:

- -

- Contour: clarity of the outline of the building;

- -

- Size: building scale;

- -

- Shape: shape complexity.

According to the above study, shape is the basic factor influencing the typological categorization of buildings and has a crucial impact on remembering buildings.

Other criteria of this study, not related to the form of the building, are:

- -

- Movement: number of people entering and walking around the building;

- -

- Intensity of use: the number of people using the building;

- -

- Singularity of use: multi-functionality of the facility;

- -

- Significance: cultural, historical, political, etc. meaning of the building;

- -

- Quality: degree of wear, maintenance of the facility.

According to the study Monograph on Planning and Design of Tall Buildings [28], three basic formal factors can be distinguished that affect the visual perception of high-rise buildings:

- -

- Form and profile;

- -

- Proportion and scale;

- -

- Color and texture.

Based on the above studies, an analysis of the basic factors influencing the reception and conceptualization of high-rise buildings in the city was adopted in the research: the scale of the building, its shape and its complexity, proportions of the tower part, form, and contour in typological terms. All these features are of primary importance in the perception of high-rise buildings as distinguishing the basic elements of the city’s image. First of all, they play a significant role in the perception of skyscrapers as landmarks, and influence high-rise buildings as key elements shaping the image of the city: regions, borders, and paths.

The following text is devoted to the analysis of architectural and urban typological forms and the abovementioned typological features of high-rise buildings in Warsaw.

2. Materials and Methods

The research methods were as follows:

- -

- Analysis of the literature on the subject of research in global projects;

- -

- Study of the implementation of Warsaw high-rise buildings based on materials collected from building managers, measurements, photographs, and map services of city offices.

The research material was then ordered and analyzed, and the results were presented in tabular form. The results were analyzed in terms of typological features and common features of buildings, and possible features distinguishing buildings from the typology of world projects were examined.

- -

- Conclusions were formulated in the final stage.

Before the research was carried out, a research plan was prepared.

2.1. Research Plan

- Determining an integrated list of types of forms of contemporary skyscraper buildings built globally:

As the first step, the integrated list of types of forms of high-rise buildings present in global projects was developed. The determination of the set of types of forms appearing in international precedents aims to define a typological base to which the Varsovian examples can be compared. Based on the results of this comparison, it will be possible to:

- -

- determine whether the types of forms of Varsovian skyscrapers are unique, new, or regional;

- -

- determine which types of forms occur most often, examining the occurrence of various types of forms over time, and thus determining possible trends in the future.

- b.

- The collection of data is necessary to define the types of forms of high-rise buildings in Warsaw:

This phase of research consisted of obtaining a set of data concerning the subject of research, which then was analyzed and ordered in a tabular and graphical form. The data was collected based on town-planning inventories, photographs, geodetic services, and interviews with designers, managers, and developers.

- c.

- Performing analysis of the basic parameters of types of forms of high-rise buildings in Warsaw:

Analysis of the structure and proportions of the building form includes the following.

2.2. Analysis of the Structure of the Form and Its Components: Tower, Podium

This analysis is aimed at examining one of the basic parameters of the form of skyscrapers, which is building of the tower part connected to the podium, or the building of the tower as a free-standing one. It is an important feature related to the reference of the form of a high-rise building to the existing urban context. The analysis is aimed at examining the trend in the building of Varsovian skyscrapers.

This is the basic distinction between the formal features of high-rise buildings implemented in an urban context.

2.3. Analysis of Parameters of the Height, Width, and Proportions of the Tower Part of the Building

The aim of this analysis is to recognize and define the basic parameters—the height and width of the tower part of the building—and to determine the building’s slenderness in order to check whether there are values of these parameters that are characteristic of Warsaw. The analysis will also allow the author to study changes in these parameters over time in order to determine trends in the implementation of the forms of high-rise buildings built from 1989 to 1922.

2.4. Analysis of Parameters of the Location of the Building in Relation to the Boundaries of Public Space

This analysis is aimed at determining whether the tower part of the building is connected to public space.

The parameter consisting in whether or not the tower part should be built as situated on the border of public space is important due to the perception of the tower form as directly involved in shaping the frontage of public spaces. Towers that constitute the boundaries of the public space, even those connected to a podium, are more legible than at the level of a passerby. The forms implemented in this way take a greater part in shaping the image of the city and creating its mental maps.

2.5. Analysis of Parameters Related to Reference to the Context: The Relation of the Form to the Nearest Surrounding Buildings

This analysis is aimed at determining whether, in the case of using a part of the podium in the forms of buildings, this part relates to the location and height of the previously existing local urban development and whether in the architecture of buildings form, elevation drawing, and formal solutions refer to the existing context.

The examined parameter—consisting of referring to the surrounding buildings by height—allows the author to determine whether such a tendency is dominant among the forms of high-rise buildings with a podium implemented in Warsaw.

- Analysis of determining the types of forms of high-rise buildings in Warsaw:

The examined buildings will be analyzed in terms of their form belonging to one of the types of forms of an integrated list of forms of skyscrapers built globally defined at the initial stage of the research. Each Varsovian building will be assigned a parameter of a type of form recognized globally. If it is not possible to assign building forms to global examples, buildings will be examined for the possibility of distinguishing new, local types. This analysis will allow the author to identify trends in the implementation of the types of forms of skyscrapers in Warsaw.

- b.

- Identification of the most characteristic features for the form of a high-rise building in Warsaw:

As a summary of the research, an examination will be carried out, firstly, on whether there are common features in the types of forms of high-rise buildings implemented in Warsaw and to what extent. Secondly, an investigation will be made whether any of the distinguished types are characteristic of projects completed in Warsaw. Conclusions from the analysis of the parameters specified above will be collected The research will also determine the possible variability over time of the types of buildings under construction and their typological features.

3. Results

3.1. Determining the Integrated List of Types of Forms of Skyscrapers Built Globally

Research on the typology of high-rise buildings in global projects was conducted based on the analysis and review of specialist publications: books, articles, and conference speeches on the subject. As a result, leading definitions of types of forms were distinguished to define categories of forms of high-rise buildings.

The study aims to distinguish a global classification of forms of high-rise buildings. Since the number of high-rise buildings in the world exceeds 22,000, the analysis of forms of the skyscrapers built globally must be based on research papers on the types of characteristic forms in order to integrate them into a coherent list. The classifications of research on high-rise buildings selected for the investigation are global, not taking into account the geographical location; in terms of the time of implementation, they mainly take into account buildings built in the second half of the twentieth century and in the twenty-first century. In the next step, research on high-rise buildings built in Warsaw was planned. The developed integrated classification of global forms serves as a comparative reference for the forms of Warsaw skyscrapers.

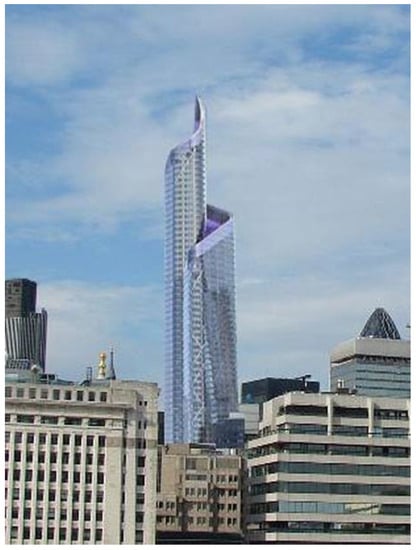

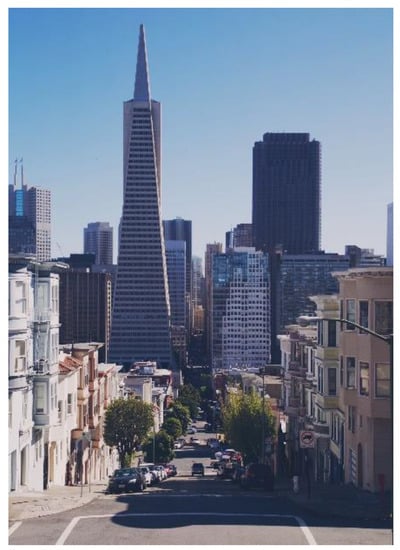

The first type of list of types of forms of skyscrapers coherent (relating to global implementations) is given in the article by Musiał R., The Game of Associations: The Shape of a Tall Building [29]; four types of forms of contemporary high-rise buildings were distinguished: a spiral form, e.g., the concept of Bishopsgate Tower in London, designed by KPF (Figure 2); a form of a pyramid, e.g., The San Francisco Transamerica, designed by W.L. Pereira (Figure 3); an obelisk, e.g., Trump World Tower in New York, designed by C. Condylis (Figure 4); and a gate and a triumphal arch, e.g., La Grande Arche de La Défense in Paris, designed by J.O. von Spreckelsen (Figure 5).

Figure 2.

Spiral form of a skyscraper—Bishopsgate, London, concept design by KFP, 2008. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

Figure 3.

Pyramid form of a skyscraper—Transamerica in San Francisco, design by W.L. Pereira, 1972. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

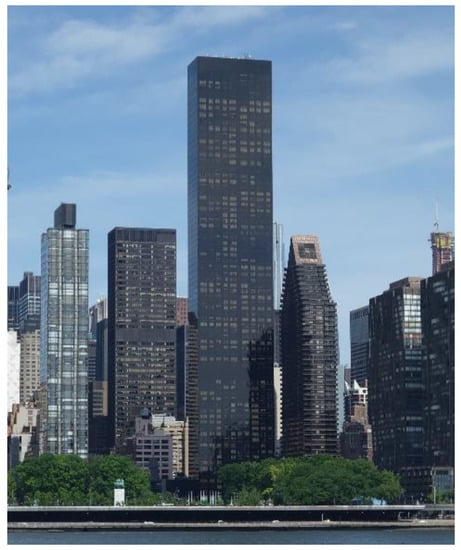

Figure 4.

Obelisk form of a skyscraper—Trump World Tower in New York, design C. Condylis; 2001. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

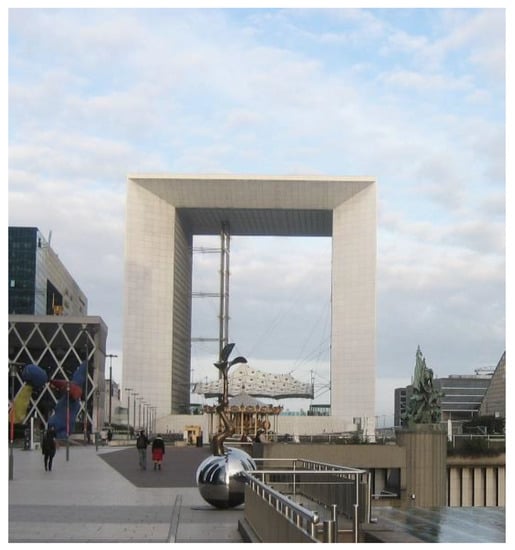

Figure 5.

Gate/triumphal arch form of a skyscraper—La Grande Arche in Paris, design by J.O. von Spreckelsen, 1989. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

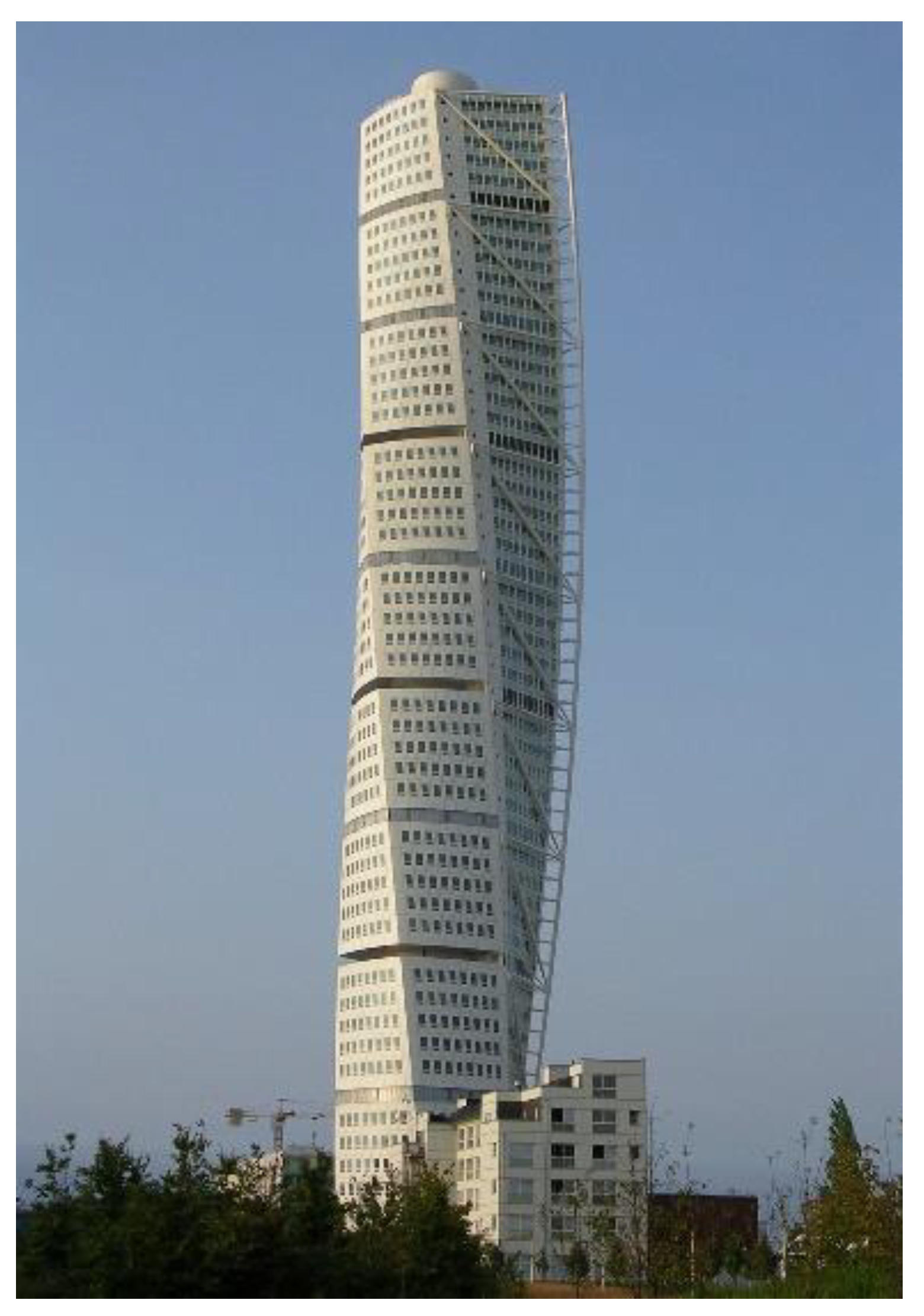

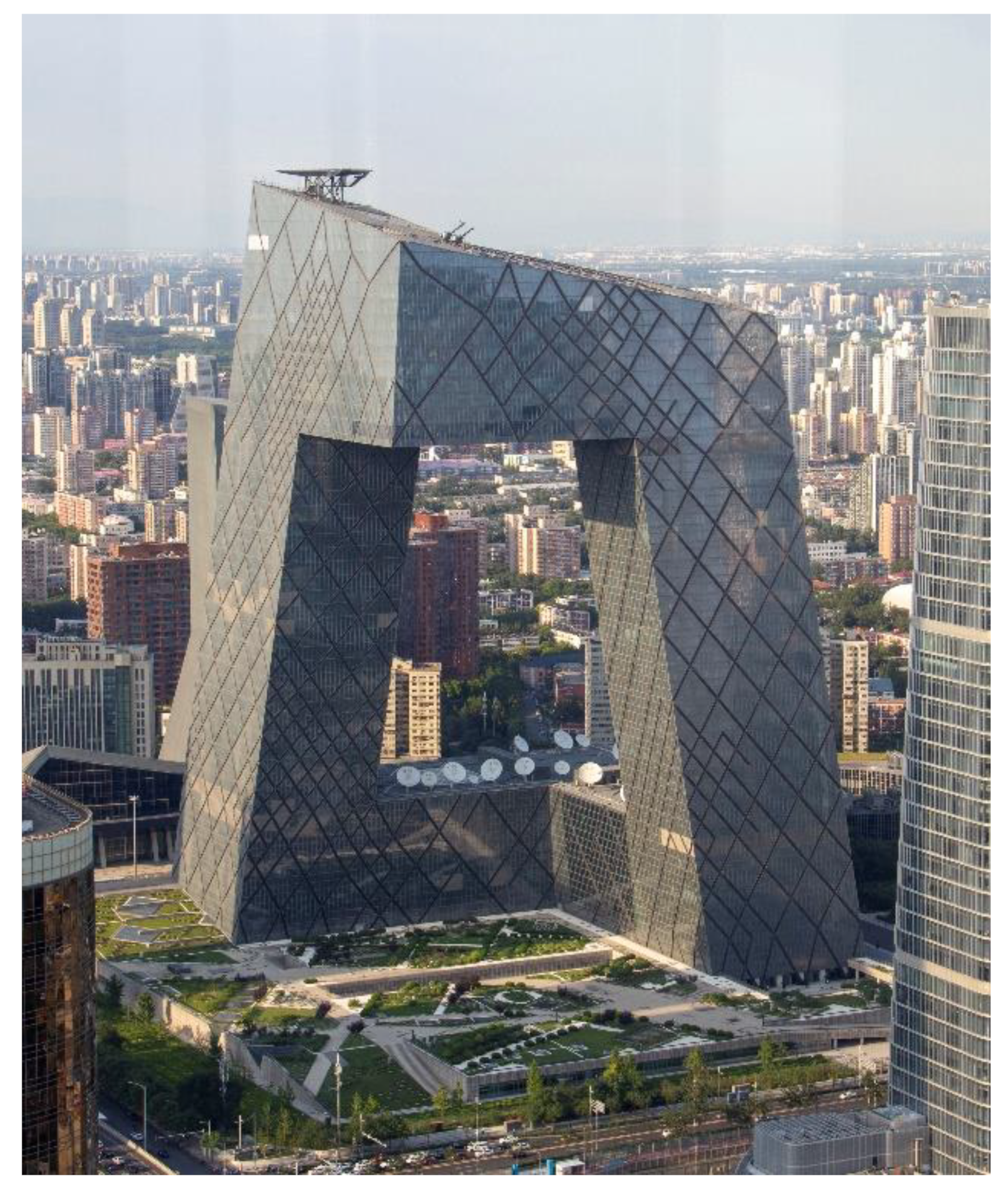

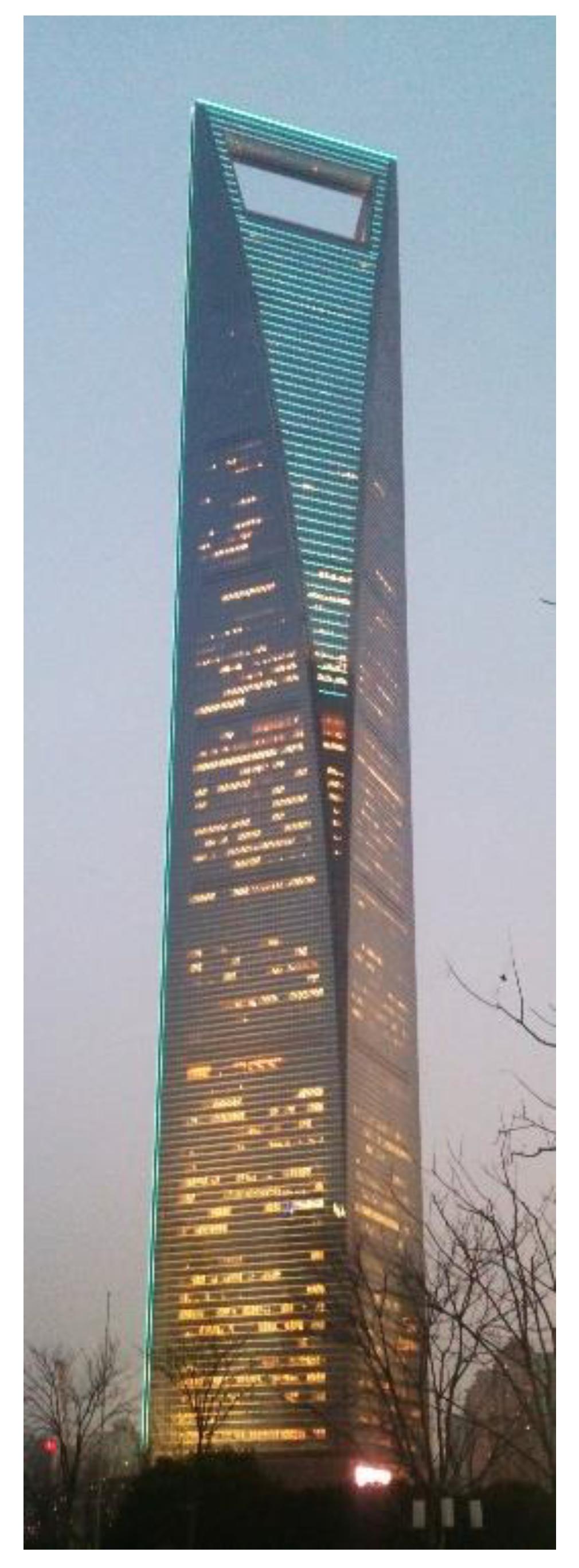

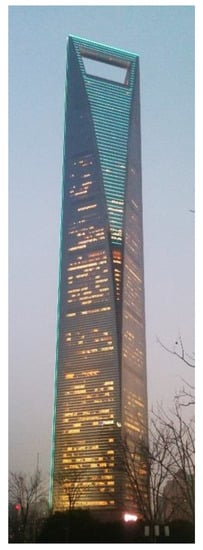

An extended classification of forms of high-rise buildings in comparison with the study by R. Musiał can be found in the study Integration of Architectural Design with Structural Form in Non-Orthogonal High-Rise Buildings [30]. The classification of non-orthogonal forms of high-rise buildings was developed and given as follows: pyramidal forms, e.g., Transamerica Building in San Francisco (Figure 3); leaning forms, e.g., The Gate Of Europe in Madrid, designed by P. Johnson (Figure 6); twisted forms, e.g., Turning Torso in Malmo, designed by S. Calatrava (Figure 7); free forms, e.g., CCTV Tower in Beijing, designed by OMA project (Figure 8); dynamic forms, e.g., the Dynamic Tower concept in Dubai, designed by D. Fisher; aerodynamic forms, e.g., Shanghai World Financial Center, designed by Kohn Pedersen Fox (Figure 9); and regional forms, e.g., Jin Mao Tower, designed by SOM in Shanghai (Figure 10).

Figure 6.

Inclined form of a skyscraper—The Gate of Europe in Madrid, design by P. Johnson, 1989. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

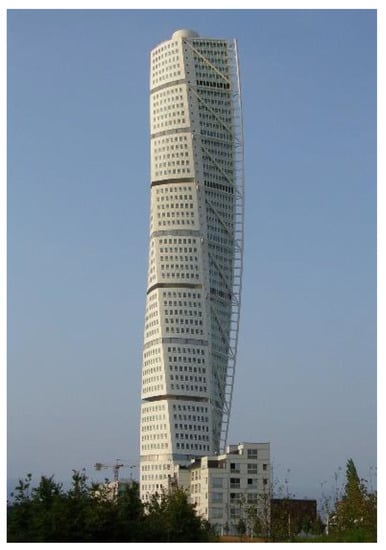

Figure 7.

Twisted form of a skyscraper—Turning Torso in Malmo, design by S. Calatrava, 2001. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

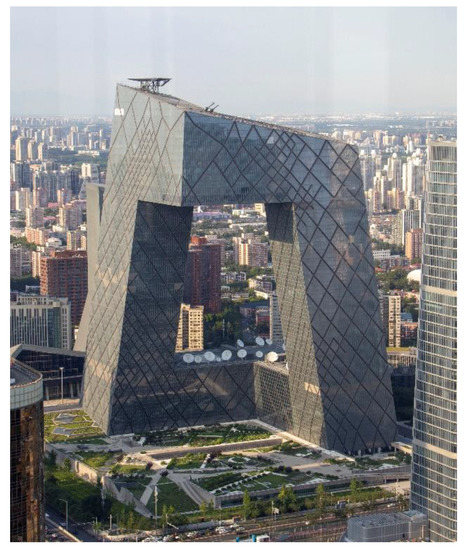

Figure 8.

Free form of a skyscraper—CCTV in Beijing, design by OMA, 2004. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

Figure 9.

Aerodynamic form of a skyscraper—Shanghai World Financial Center, design by KPF, 1997. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

Figure 10.

Regional form of a skyscraper—Jin Mao Tower in Shanghai, design by SOM, 1994. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

Another classification of forms of skyscrapers is given by Ch. Jencks [31]. It includes skyprickers (a word coined by Ch. Jencks)—buildings derived from the forms of obelisks, pyramids, and spiers, e.g., the Chrysler Building, designed by W. van Allen, Reinhard, Hofmeister, and Walquist in New York; skyscrapers—rectangular, with rectangular projections, e.g., John Hancock Tower in Boston, designed by I.M. Pei; and skycities—groups of forms shaping the structures of high-rise buildings, e.g., WTC in New York, designed by M. Yamasaki. This classification coincides with the newer, previously mentioned, and does not include inventoried forms that are present today—free, spiral, and regional forms.

The group of skyscrapers, whose forms illustrate the diversity of high-rise building shapes, are contemporary buildings exceeding a height of 300 m, referred to as supertall. Buildings of such heights and very high visibility from many points of the city are designed with regard to the role of form in perception and architectural expression. The latest classification of the forms of this type of skyscraper is given by E. Ilgin [32] as:

- -

- Prismatic forms: buildings whose two ends are similar, equal, and parallel figures, whose sides are identical, and whose axles are fully vertical;

- -

- Setback forms: buildings with recessed horizontal sections through the height of the building;

- -

- Tapered forms: buildings with a tapering effect through reduced floor plans and surface areas through the height into linear or non-linear profiles;

- -

- Twisted forms: the buildings with progressively rotating floors or façades as they multiply upward along an axis by inputting a twist angle;

- -

- Leaning/tilted forms: buildings with an inclined form;

- -

- Free forms: all other forms not previously mentioned.

The above classification partially coincides with that of R. Musiał [29] and of Sev A., Tuğrul F [30], but it lacks the indication of regional forms as existing in high-rise buildings.

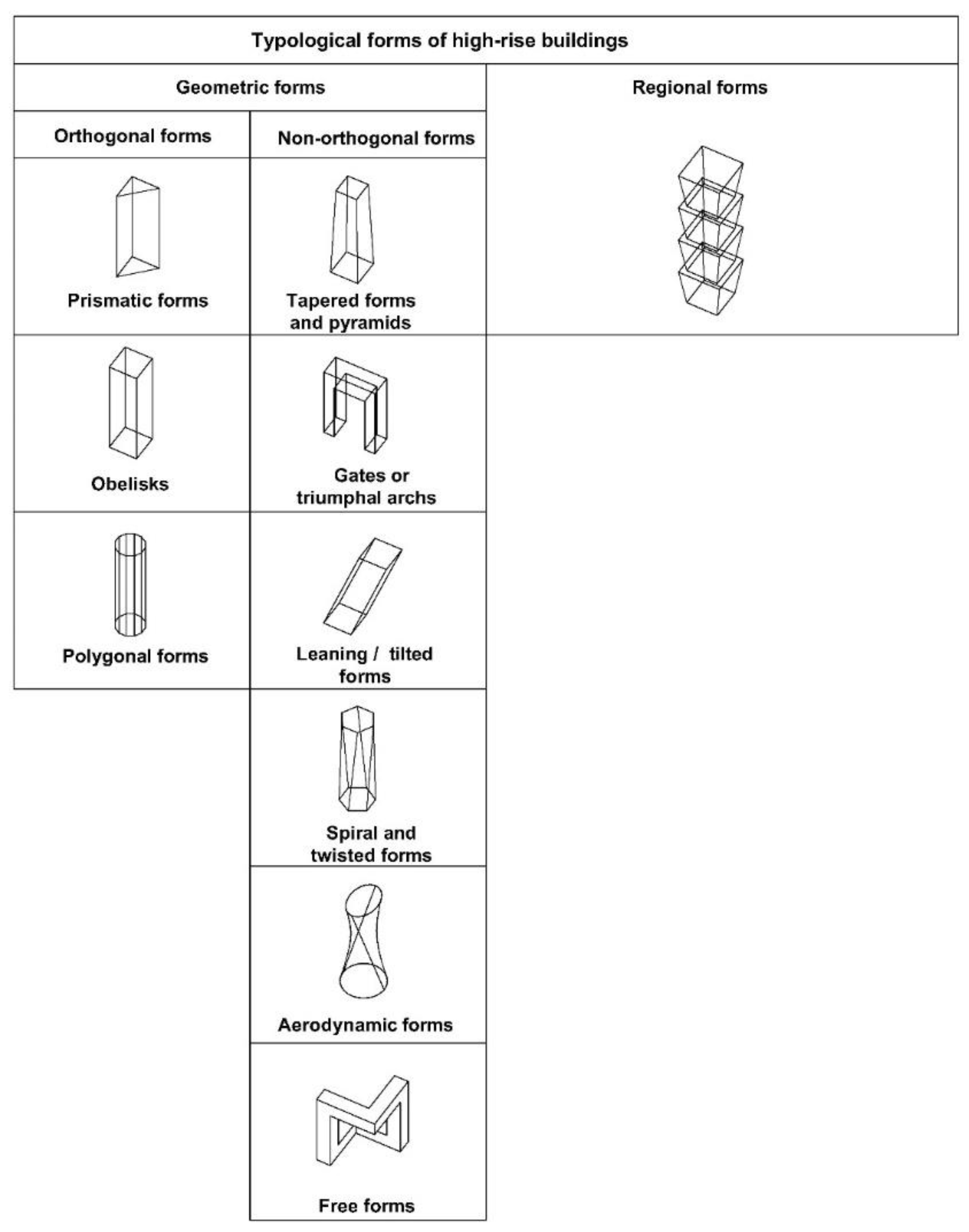

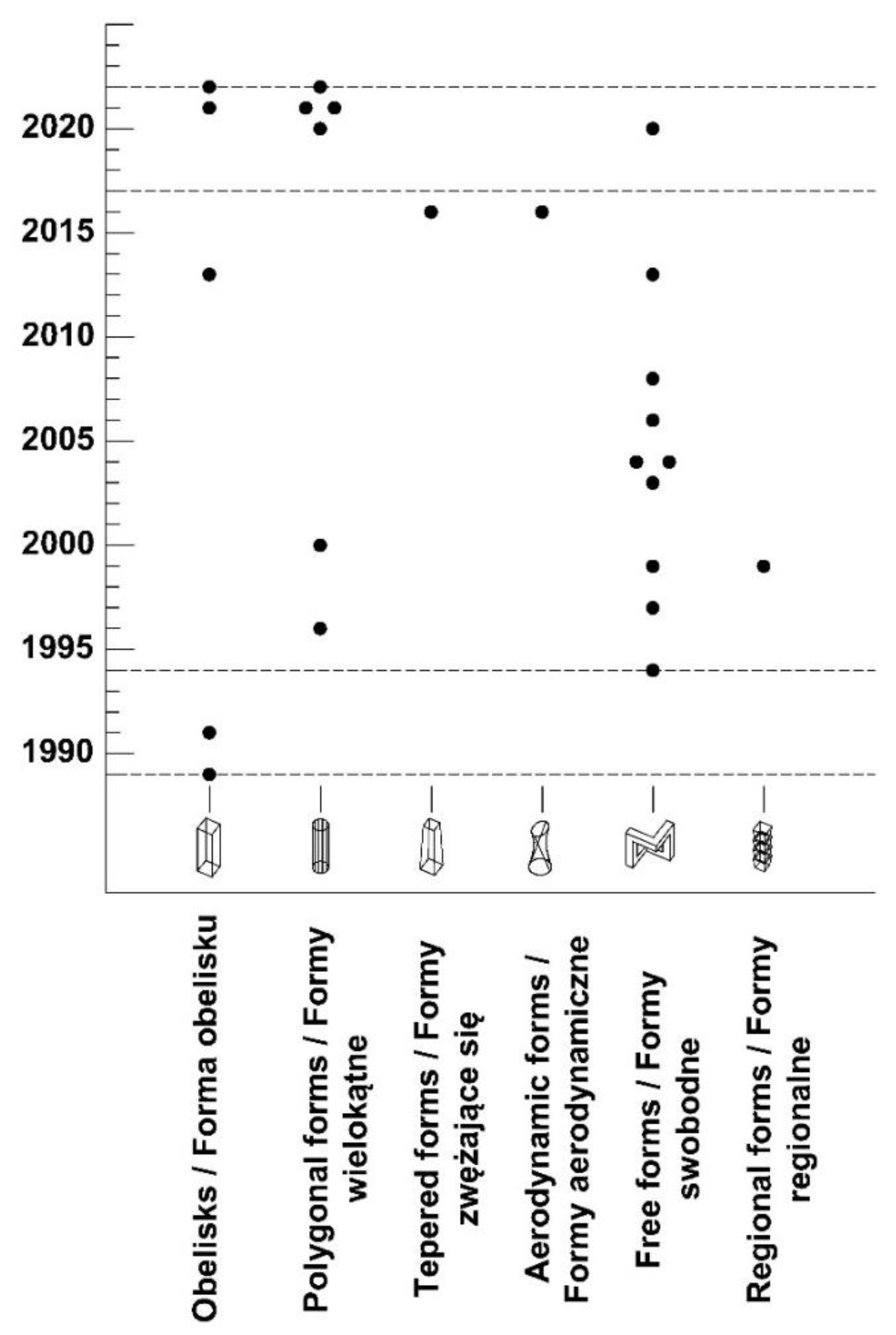

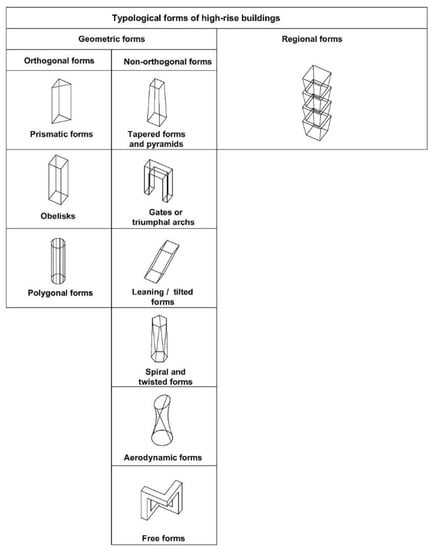

The merging of the above views on the types of forms of high-rise buildings in order to develop a set of types covering the widest possible range of world implementations is shown in Figure 11.

Figure 11.

Adopted integrated list of forms of skyscrapers built globally. Source: author’s study.

The above integrated list of forms as characteristic of global skyscrapers is an open set. Along with the development of design and implementation techniques and the changes in design paradigms, it will undoubtedly be supplemented in the future with new types following changes. There are already single projects of high-rise buildings appearing that are the harbingers of new types of forms of high-rise buildings.

For example, as a new type of form of high-rise buildings, the latest literature gives super-slender buildings with proportions on the order of 1:20 [33,34], e.g., 111 West 57 Street in New York, designed by SHoP Architects; eco-skyscrapers [35,36], e.g., Bosco Verticale in Milan, designed by S. Boeri; and hybrids [37,38,39], e.g., Marina City Complex in Chicago, designed by B. Goldberg. The shift in design paradigms and the emergence of new typologies of skyscrapers is an on-going process that can be observed contemporaneously [16,17,18].

Nevertheless, for the purposes of this paper, it was assumed that buildings of these forms, such as prototypical and individual, will not be included in the integrated list of the most characteristic world forms as indicated in Figure 11, to which Varsovian high-rise buildings will be compared.

3.2. Collection of Data and Analysis of the Typology of the Form of High-Rise Buildings in Warsaw

After collecting data on the forms and locations of high-rise buildings, analyses of buildings constructed in Warsaw in the years 1989–2022 were carried out.

These forms have been investigated on the basis of the following criteria, which will make it possible to distinguish in quantitative terms the dominant formal solutions in the analyzed period:

- -

- The presence of a podium, combined with the tower part:

This criterion was accepted as important due to the reception of the form of a high-rise building in the city space. Examination of this parameter will determine whether the preferred form of construction is a free-standing tower or a tower connected to the lower part of a podium;

- -

- The existence of formal references to the surrounding context:

This criterion will allow the determination of whether the existing context influenced the form of the skyscraper. The impact may relate to the characteristic parameters of the surrounding buildings, e.g., height, which affects the height of the podium, or stylistic solutions, e.g., divisions of facades, materials, etc., which may be reflected in the formal solutions of the high-rise building;

- -

- Slenderness:

Examination of this criterion will allow the determination of one of the most characteristic parameters of the form of a high-rise building, and to determine what slenderness of skyscrapers is the dominant solution in Warsaw;

- -

- The location of the tower portion in relation to the border of the public space:

The location of the main mass of the tower of a building—when using a podium or in the construction of a tower portion without a podium—directly at the border of public space has a significant impact on the visibility of the tower. Such projects make the shape of the tower a direct determinant of the street space, making it a characteristic element of the perception of the city’s public space from the perspective of pedestrians. The examination of this criterion will allow the determination of whether such a solution is characteristic of Warsaw;

- -

- The type of form compared to the developed integrated set of forms of high-rise buildings built worldwide:

This criterion will allow the author to determine whether the forms of skyscrapers implemented in Warsaw coincide with the types of forms of skyscrapers implemented globally. The comparison will show how often the regional form is implemented, or how it is different than forms occurring worldwide. In such a case, it will be possible to speak of a local type of form other than the typical global forms. At the same time, the study will allow the determination the type of form most often used in the studied period in Warsaw and the frequency of its use, as well as the possible variability of the preferred type of form over time;

- -

- Primary function:

This criterion will allow the author to determine the typological background for the implementation of the form of a high-rise and to recognize whether there is a correlation between the function of the building and the preferred type of form.

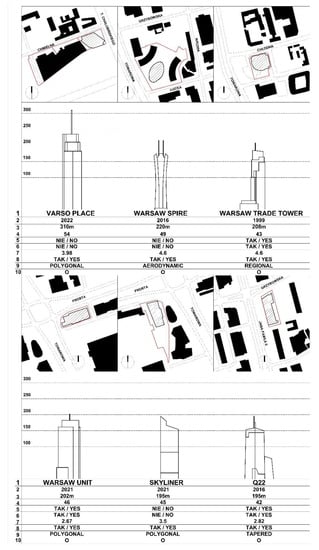

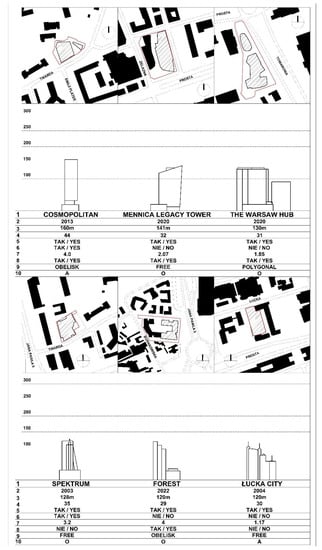

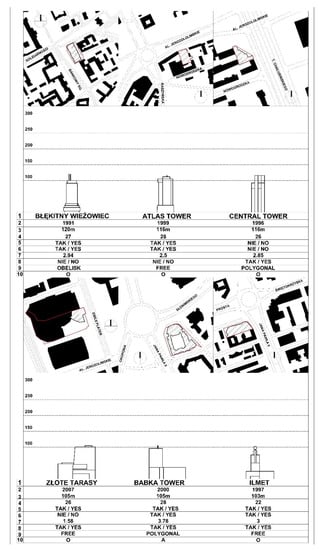

Figure 12.

Typology of forms of high-rise buildings in Warsaw, Part 1. Legend: 1—name of the building; 2—year of construction; 3—total height, 4—number of stories; 5—presence of a podium, 6—formal references to the context; 7—slenderness; 8—location of the tower part within the boundary of public space; 9—form type; 10—primary function: O—office, A—apartments, H—hotel. Source: author’s study.

Figure 13.

Typology of forms of high-rise buildings in Warsaw, Part 2. Legend: 1—name of the building; 2—year of construction; 3—total height, 4—number of stories; 5—presence of a podium; 6—formal references to the context; 7—slenderness; 8—location of the tower part within the boundary of public space; 9—form type; 10—primary function: O—office, A—apartments, H—hotel. Source: author’s study.

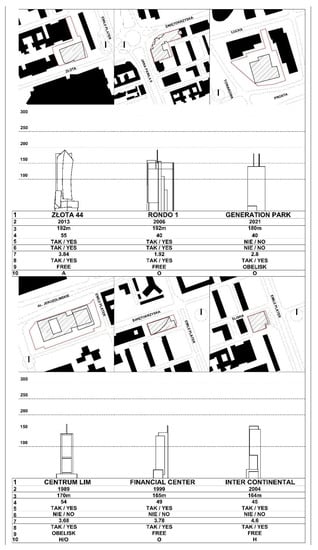

Figure 14.

Typology of forms of high-rise buildings in Warsaw, Part 3. Legend: 1—name of the building; 2—year of construction; 3—total height; 4—number of stories; 5—presence of a podium; 6—formal references to the context; 7—slenderness; 8—location of the tower part within the boundary of public space; 9—form type; 10—primary function: O—office, A—apartments, H—hotel. Source: author’s study.

Figure 15.

Typology of forms of high-rise buildings in Warsaw, Part 4. Legend: 1—name of the building; 2—year of construction; 3—total height; 4—number of stories; 5—presence of a podium; 6—formal references to the context; 7—slenderness; 8—location of the tower part within the boundary of public space; 9—form type; 10—primary function: O—office, A—apartments, H—hotel. Source: author’s study.

3.3. Summary of the Results of Investigation on the Forms of Skyscrapers Present in Warsaw

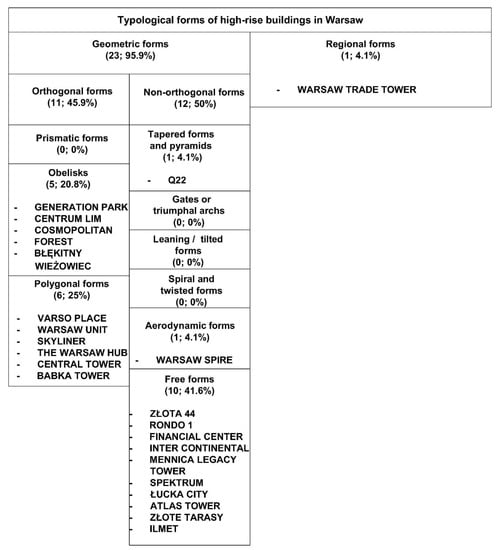

Figure 16 shows the collective results of the analysis. A comparison of the forms of skyscrapers present in Warsaw with the characteristic forms occurring globally is presented in Figure 11.

Figure 16.

List of typological forms of high-rise buildings in Warsaw. Source: Author’s study.

The above summary shows, that the most common form among skyscrapers built in Warsaw from 1989 to 2022 was the free form, which was present in 41.6% of buildings. Therefore, it should be recognized that this type of form is currently the dominant, characteristic type of Varsovian skyscrapers. Another common type was the polygonal form, which was seen amongst 25% of the buildings, followed by the obelisk form, which was found in 20.8% of the cases. The above three types of forms, the most common in Warsaw, are those that occur globally. Aerodynamic, tapering, pyramid, and regional forms occurred; each occurred only once. There were no prismatic, gate, spiral, twisted, or inclined forms found.

The absence of these forms is related to the following reasons:

- -

- Low efficiency and commercialization difficulties related to the geometry of projections of prismatic forms;

- -

- The lack of coherent planning of the construction of high-rise buildings [6], which is necessary for the location of buildings in the form of gates or triumphal arches;

- -

- Greater technological requirements—design and implementation related to the construction of inclined, twisted, and spiral forms and higher cost of their construction.

Among the three most common forms, the average height of the buildings was the highest amongst polygonal forms, at 176 m high, followed by the obelisk forms, at 150 m high, and free forms, at 142.6 m high.

3.4. Identification of the Most Characteristic Parameters of Types of Forms Occurring in Warsaw

A characteristic feature is that most of the buildings have a podium, constituting 79% (19 cases). The use of the podium in combination with the tower part is a globally applied procedure, but the frequency of this solution is significant in Warsaw. The reason for this is the intention to maximize the potential of the area. The factor related to the urban composition, consisting in the realization of the mass of the building as having a podium that is formally adapted to the scale of the surrounding buildings, is present, but not strongly dominant. Only in a slight majority of these buildings—10 cases—does the height of the podium refer to the surrounding buildings.

A strong characteristic of all the examined buildings is that the tower part of the building, even in the presence of a podium, touches the level of public space, constituting its spatial limitation. This is present in 83% of buildings (20 examined cases).

The collected data covers the period of 33 years of construction of high-rise buildings in Warsaw. This is a wide range of time, in some cases covering the lifetime of the building; for example, the 103-m-high Ilmet building constructed in 1997 is to be replaced by a taller facility with a similar office function. This makes it possible to define possible changes in time related to the forms of high-rise buildings, which will allow for the recognition of possible changes in the trends of the implementation of free forms at a given time.

For the analyzed projects, the average construction year was 2008. In the analyzed period of 33 years, on average, 0.72 of buildings were commissioned per year. The average height of the buildings was 161 m tall and average slenderness was 3.15.

To determine the distribution of types of forms of buildings completed over the years, it is possible to determine the average year of completion of individual types of buildings over time. The average age of each type of form is as follows:

- -

- The only building with a tapered form was completed in 2016 (4.1% of cases);

- -

- The only building with an aerodynamic form was completed in 2016 (4.1% of cases);

- -

- The average year of construction of polygonal buildings (25% of cases) is 2013;

- -

- The average year of construction of buildings in the form of an obelisk (20.8% of cases) is 2007;

- -

- The average year of construction of free-form buildings (41.6% of cases) is 2004;

- -

- The only building with a regional form was completed in 1999 (4.1% of cases).

This is a statistical result covering 33 years of implementation, but it is clear that the most common free form buildings are among the oldest ones implemented in Warsaw.

Against the abovementioned background of the average data for the 23-year period, forms present among the buildings erected in the last 5 years were distinguished and examined to determine the trends present in the latest projects.

Such an investigation shows that:

- -

- The average number of buildings under construction per year is 1.4 buildings, which indicates the current quantitative acceleration of the construction of high-rise buildings;

- -

- The average height of the building is 183 m, which indicates an increase in the height of the buildings currently under construction.

Over the last 5 years, there has been a quantitative departure from the implementation of free-form objects, the most typical over the entire period of 33 years, towards more rational polygonal forms. The most frequently implemented forms recently were: polygonal forms—57% of buildings (4), and obelisk forms—29% of buildings (2). The obelisk forms were built in the last 5 years. Only 14% of buildings (1) constructed in the last 5 years were free form.

- -

- The average slenderness of the building is 2.97, which indicates a growing tendency to build buildings with more massive and cost-effective projections.

- -

- Four buildings (57%) have a podium and only one refers to the immediate context, which indicates a decline in the implementation of both these previously characteristic features of buildings.

- -

- All tower parts (100%) are built on the border of public space, which indicates that this characteristic feature of the form of high-rise buildings in Warsaw has been preserved in the latest projects.

4. Discussion

4.1. Forms of High-Rise Buildings in the Landscape of Warsaw

High-rise buildings are perceived by city users from several perspectives. In the farthest, up to several kilometers away, buildings form a silhouette characteristic of a city [16], which is often a symbol of the metropolis. From a distance, the silhouettes of buildings are unrecognizable in detail; the main role is played by the scale and slenderness of the tower parts, the mutual distances between the buildings, and the planning decisions affecting the shaping of the silhouette due to location parameters.

The forms of buildings begin to be visible at medium distances, lower than 5 km long, where the observer can already recognize the individual shapes and profiles of buildings. In Warsaw, such views are primarily provided by the observation of the city silhouette from the bridges connecting the banks of the Vistula River. Some of the bridges are located farther away, allowing the view of the entire city silhouette; some of the bridges are located at medium distances from the cluster of skyscrapers, where individual buildings are already distinguishable. From such perspectives, due to the distinction of individual forms, city users can recognize the location of areas, public places, and regions in the city structure where the buildings are located [40,41].

Close perspectives from a distance of less than a few kilometers are views of high-rise buildings from the level of public space of streets and squares, in which high-rise buildings are primary elements of the urban composition and objects that co-shape the image of the city. Separate research [6] has shown that in most cases in Warsaw, in terms of the urban composition and the image of the city, the location of high-rise buildings in Warsaw are determinants of spaces of streets and paths (65%), and a significant number (21.7%) are determinants of a transport node. Only two buildings—the Cosmopolitan and Błękitny Wieżowiec (the Blue Skyscraper)—are located on a city square.

Due to the reception of the form from the public space, the significant width of streets with high-rise buildings and their locations at transport junctions allow passers-by to see the entire body of the building from the level of public spaces without having to look up, at an angle of visibility convenient for passers-by [40,41]. This means that the strong forms of high-rise buildings in Warsaw are mostly recognizable landmarks, perceived by the city’s inhabitants. This is evidenced by, for example, vivid comments and names given to some skyscrapers by the public that circulate among the inhabitants of Warsaw; e.g., Atlas Tower is commonly called “Toi” (Porta Potty), Łucka City is “the ugliest building in the city”, and Błekitny Wieżowiec, due to its characteristic color, is named “Blue Skyscraper”.

The full visibility of a form of Warsaw’s skyscrapers is different only for the Spektrum building, which is located on a narrow street in the vicinity of higher residential and service buildings in such a way that the full visibility of its entire form is low and the perception of the building by passers-by is limited mainly to the podium.

The conducted research does not show any dependence or correlation between the location of buildings in terms of city elements—streets or squares—and the form of buildings. Buildings of both the free form and the obelisk form are located next to squares, and all types of forms are located by streets.

A comparison of the forms of skyscrapers built in Warsaw over the studied period with the developed catalog of types of forms of skyscrapers built around the world shows that Varsovian high-rise buildings do not have clear local or regional features. In Warsaw, the existing local factors that affect the form of high-rise buildings do not determine the emergence of specific types of forms on a global scale. Their influence leads to the use of solutions and forms already known around the world. These factors and their impact can be grouped as follows:

- Planning factors based on the policy of protecting the skyline of Warsaw from the side of the Vistula River. The heights of the buildings are limited so that they do not dominate the historical buildings included in the UNESCO heritage list visible from the side of the river. This policy leads to the grouping of high-rise buildings in the center of Warsaw, in locations surrounded by downtown buildings. As a result of this:

- -

- the skyscrapers are located on relatively small investment plots, which leads to the frequent construction of the tower part as directly adjacent to the public space because, even in the case of a podium, its surface projection is small;

- -

- there is a frequent implementation of the podium as an element that can increase the building area, with a simultaneous tendency to implement the height of the podium referring to the existing context;

- Factors related to the provisions of insolation and blocking development, which consists of the necessity to provide 1.5 h of sunlight to apartments and the construction of high-rise buildings at a minimum distance of 17.5 m from the existing buildings in the downtown Warsaw. In some cases, these regulations provoke the implementation of free or narrowing forms that are adapted to the insolation diagrams of the surrounding buildings. Examples of forms resulting from the application of these regulations are the free form of the Inter-Continental Hotel or the tapered form of the Q22 office building.

Warsaw’s entry into the trend of implementing globally recognized forms can be explained by the construction of high-rise buildings primarily by investors with foreign capital, and the desire to build forms that are recognized worldwide. In this situation, experiments or formal novelties are not desirable. The reliability associated with taking from a reservoir of proven, world forms of high-rise buildings is more appealing. Nevertheless, it is possible to distinguish a dominant type in the forms of skyscrapers in Warsaw and to trace the variability of the use of a certain type of form in time.

4.2. Representative Examples of Types of Forms of High-Rise Buildings in Warsaw

- -

- A characteristic example of a building with a free form:

Free forms are the most common type among the projects of Warsaw high-rise buildings in the analyzed period 1989–2022; they account for 41.6% of all projects. These are forms that fit into the global type of high-rise buildings and their local distinguishing feature, typical of Warsaw, is their dominance among the completed buildings. The building which, due to its scale and formal solutions, represents this type of form is the Inter Continental, shown in Figure 17.

Figure 17.

Inter Continental in Warsaw, designed by T. Spychała, 2004—an example of free form; view from the north. Source: author’s study.

This building was built in 2004 according to the design of T. Spychała’s office. The height of the building is 164 m and the slenderness of the tower part is 4.5. The tower part is a frontage of public space. The building has a podium, but it does not correspond to the height of the surrounding buildings. Its basic function is a hotel with service spaces located in the podium. The total area of the building in the above-ground part is approximately 57,000 m2 [6]. The form of the tower part of the building is a cuboid whose lower half has been cut by a monumental clearance. The whole building is placed on a three-story podium that, in its scale and means of expression, does not refer to the previously existing context. The form of the building results from the necessity to provide adequate lighting to the existing residential buildings, as required by Polish law [42]; this is the purpose of the characteristic cut-out that transmits the sun’s rays towards the existing building, so as to provide it with the required 1.5 h of sunlight. The shape of the building is characteristic; it marks the course of Emilii Plater Street on a city scale. The role of the building in shaping the city’s image is to define a path and create a landmark.

- -

- A characteristic example of a building with a polygonal form:

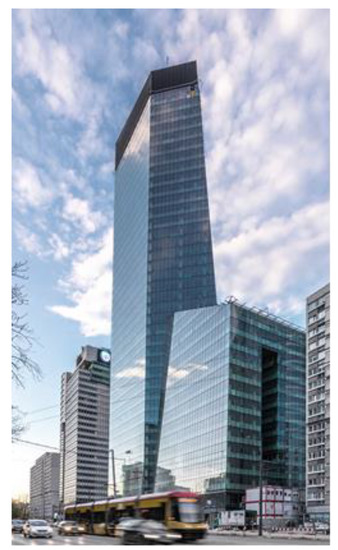

Polygonal forms are the second most common type among Warsaw high-rise buildings in the analyzed period 1989–2022; they cover 25% of all projects. Comparing them with similar types of forms realized around the world, no characteristic local features can be seen. The building that, due to its scale and formal solutions, represents this type of form is the Warsaw Unit, shown on Figure 18.

Figure 18.

Warsaw Unit in Warsaw, designed by Polish-Belgian Architecture Studio, 2021—an example of polygonal form; view from the north-west. Source: author’s study.

The skyscraper was built in 2021 according to the design of the Polish-Belgian Architecture Studio. The height of the building is 202 m and the slenderness of the tower part is 2.67. The tower part is a frontage of public space. The building has a podium referring to the height of the surrounding buildings. Its primary function is offices. The total area of the building in the above-ground part is approximately 78,800 m2. In the podium part of the building, there are small service areas in its scale and a multi-story overground car park [6]. The elevation of the podium part is covered with a kinetic facade system that reacts and reflects gusts of wind. The height of the podium is similar to the existing buildings. The form of the tower part reaches the base of the building, constituting a distinctive facade of the public space. The polygonal form of the tower part results from the contour of the building following the with the shape of the plot to the maximum extent; it therefore results from the intention to maximize the use of the plot area for development, i.e., primarily economic factors. The whole complex is topped with a black rectangular block representing technical spaces. In the image of the city, the building is a recognizable landmark defining the Daszyńskiego roundabout node.

- -

- A characteristic example of an obelisk-shaped building:

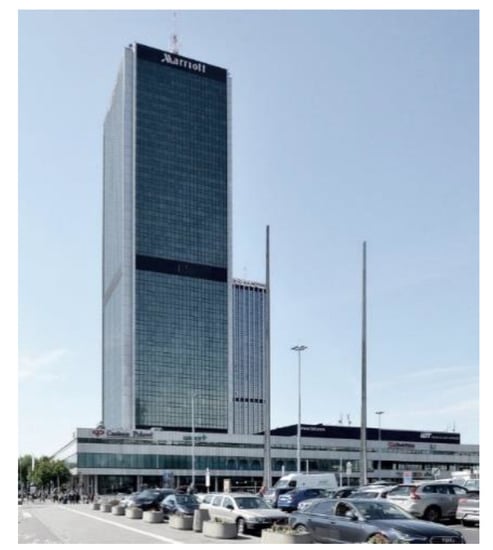

Buildings in the form of an obelisk are the third most frequent group in terms of the typology of form among the constructions of Varsovian skyscrapers in the analyzed period 1989–2022. Varsovian skyscrapers in the form of an obelisk are typical of other world projects. They cover 20.8% of all implementations. The building that, due to its scale and formal solutions, represents this type of form is Centrum Lim, shown on Figure 19.

Figure 19.

Lim Center in Warsaw, designed by J. Skrzypczak, 1989—an example of the obelisk form; view from the north. Source: author’s study.

The building was erected in 1989 according to the design of a team led by J. Skrzypczak. The height of the building is 170 m and the slenderness of the tower part is 3.68. The tower part is not a frontage of public space. The building has a podium, but it does not correspond to the height of the surrounding buildings. Its primary function is a hotel and offices. The total area of the building in the above-ground part is approximately 87,600 m2. In the podium part of the building, there are service and commercial spaces organized in the form of a gallery. It is the most multifunctional building among the developments in Warsaw’s high-rise buildings [6]. The podium is extensive—it covers the entire quarter of two buildings—and its height does not correspond to the surrounding buildings. The form of the building is a classic solution for modernist high-rise buildings, consisting of an obelisk tower placed on a larger, horizontal podium. In the image of the city, the building is a recognizable landmark that marks the course of an important street—Aleje Jerozolimskie.

- -

- The tapered-form building:

The only building with a narrowing form among the constructions of Warsaw high-rise buildings in the analyzed period 1989–2022 is Q22, shown on Figure 20. Its form is a local variation of the typical world form of a tapered building, despite the fact that its origin is due to local building regulations. The sharply cut shape of the tower and the podium in the projection is the result of analysis of the insolation of the surrounding residential buildings carried out during the preparation of the project. The form of Q22 is characteristic and highly recognizable in the landscape of Warsaw.

Figure 20.

Q22 in Warsaw, design by Kuryłowicz & Associates, 2016—an example of tapered form; view from the south. Source: author’s study.

The building was built in 2016 according to the design of the Kuryłowicz & Associates studio. The height of the building is 195.4 m and the slenderness of the tower part is 2.82. The tower part is a frontage of public space. The building has a podium referring to the height of the surrounding buildings. Its primary function is offices. The total area of the building in the above-ground part is approximately 69,000 m2. The building is connected to the podium part, which with its height refers to the surrounding buildings of the high residential blocks of the Osiedle za Żelazną Bramą [6] The tower part of the building connects at the base with the public space of the city, shaping its boundaries in a monumental way. In the image of the city, the building is a recognizable landmark that marks both a node—the intersection of Jana Pawła II and Grzybowska Streets—and the course of both streets.

- -

- The aerodynamic form building:

The only building with an aerodynamic form among Warsaw high-rise buildings constructed in the analyzed period 1989–2022 is Warsaw Spire, shown on Figure 21. The form represents the type of high-rise objects realized around the world; in its solutions, it does not show any features that might indicate specific, local properties.

Figure 21.

Warsaw Spire in Warsaw, designed by Jaspers & Eyers Partners, 2016—an example of the aerodynamic form; view from the south-west. Source: author’s study.

The mentioned building was constructed in 2016 according to a design by Jaspers & Eyers Partners. The height of the building is 220 m and the slenderness of the tower part is 4.6. The tower part is a frontage of public space. The building does not have a podium. Its primary function is offices. The total area of the building in the above-ground part is approximately 74,000 m2. The building has the form of a free-standing tower in the public space stretching around it, forming a square in the north-eastern part called Plac Europejski, whose elevations are lower office buildings. It was the only high-rise building in Warsaw designed and implemented together with a defined, legible public space [6]. The form of the building is distinctive—its base is an elliptical, variable-in-size floor plan located at an angle to the entire quarter, parallel to the directions of the prevailing winds and the flow of city users in the surrounding public spaces. The genesis of the form w a combination of striving to achieve a strong architectural expression based on rational action related to the structure of the building—resistance to horizontal forces generated by the wind—and the assumed four-way symmetry of the main part of the form. In the image of the city, the building is a recognizable landmark that marks both the nodes Plac Europejski and the course of Towarowa Street, with an exhibition towards the important communication node of Rondo Daszyńskiego.

- -

- The regional form building:

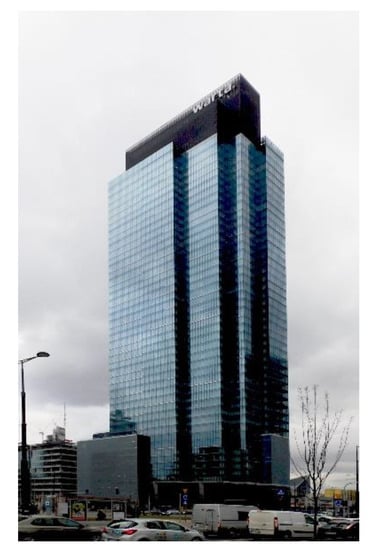

The only building with an regional form [43] among the construction of Warsaw high-rise buildings in the analyzed period of 1989–2022 is the Warsaw Trade Tower, shown on Figure 22.

Figure 22.

Warsaw Trade Tower in Warsaw, designed by RTKL and Wyszyński, Majewski, Hermanowicz, 1999—an example of a regional form; east view. Source: author’s study.

It is a special project among Warsaw skyscrapers because the local context is most clearly visible in it. It can be concluded that it is the only strong local modification of the forms existing globally, with the adopted architectural solutions related to shaping the form and facade of the building.

The above building was completed in 1999 according to the design of RTKL and Wyszyński, Majewski, Hermanowicz. The height of the building is 208 m and the slenderness of the tower part is 4.6. The tower part is a frontage of public space. The building has a podium referring to the height of the surrounding buildings. Its primary function is offices. The total area of the building in the above-ground part is approximately 54,800 m2. The form of the building consists of a tower connected to the podium with complementary functions—services and gastronomy. The tower part of the building connects to the public space [6]. The building was erected on a relatively large plot, in the dense development of the Wola district. In developing its shape, the issue of providing light to the existing buildings did not play a significant role. The form of the building and its architectural expression, according to the authors’ declaration, was to reflect the growth of Warsaw over time, and consists of differently shaped blocks with different facade solutions. This procedure, combined with the authors’ intentions, means that the form of the Warsaw Trade Tower can be classified as an example of a regional form in terms of typology. In the image of the city, the building is a recognizable landmark that marks the course of Towarowa Street.

4.3. Expected Changes over Time

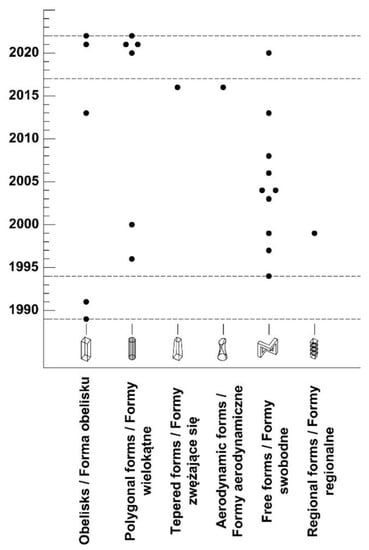

The research shows that during the analyzed period, there was a change in the frequency of the implementation of typological forms of high-rise buildings in Warsaw, which was presented on Figure 23.

Figure 23.

Changes in the implementation of typological forms of high-rise buildings in Warsaw over the years 1989–2022. Source: author’s study.

Statistically, throughout the analyzed period over the course of twenty-three years, the most frequently realized type of form was the free form. Nevertheless, it can be noticed that the dominant solution at the beginning of the analyzed period (1989–1994) was the form of the obelisk, the free form dominated in the middle part of the period studied, and in the last five years—2017–2022—polygonal forms dominated. Throughout this period, the forms of skyscrapers followed similar worldly examples, and the only strong local formal modification was the construction of the Warsaw Trade Tower skyscraper in 1999. This process resulted from the fact that its beginnings go back to the strong presence of the modernist style in the initial phase, combined with more modest technical possibilities of building high-rise buildings, which resulted in the implementation of the pioneering and simple-to-express forms of the obelisk in 1989–1994. Free forms dominated in the stylistic period focused on the implementation of architectural icons formally distinguished from the surrounding buildings (an example is the construction of the Złote Tarasy or Złota 44 buildings), and their implementation was associated with an increased inflow of capital and the development of implementation techniques of Polish contractors.

The transition to the implementation of mainly polygonal forms in the last five years can be explained by the maturity of the market and the desire to optimize functional solutions—a departure from non-orthogonal projections less conducive to the commercialization of buildings. This is evident, inter alia, by the increase in the size of layouts and the reduction of the slenderness of their mass. There is also a clear tendency towards an increase in the number of completed buildings per year and an increase in their scale—height and size. It can be assumed that these trends will continue in the near future.

A similarly characteristic feature of the objects—the construction of the tower part, especially in the case of forms connected with the podium, at the border of the public space—will be maintained. The reason for this is the decreasing number of available areas with a larger area on which high-rise buildings can be built. Smaller downtown investment plots on which high-rise buildings will be built will result in solutions where the maximum tower will fill the area; irregular shapes of plots and the need to provide additional lighting to the surrounding buildings will provoke the implementation of polygonal forms, or—as in the case of the Inter-Continental building—free forms. Therefore, there is no uniform typological pattern for the Warsaw projects in the analyzed period. The transition from the realization of free forms to polygonal forms proves the variability in the dominant type of constructed buildings. For this reason, research and determination of this variability should be continued in the future.

The lack of local evolution of the type of form, different from the global examples in the studied, long-term period of time, also suggests that in the future, the projects of high-rise buildings in Warsaw will be similar to the types of forms implemented worldwide, and buildings forms that stand out will be exceptions.

5. Conclusions

The paper presents research on types of forms of skyscrapers erected in Warsaw in the years 1989–2020. The scope of the conducted research included:

- -

- Preliminary research to define the typology of high-rise buildings in global projects:

Preliminary research allowed the definition of formal types of commonly constructed high-rise buildings. Geometric forms and regional forms were selected. Among the geometric forms, orthogonal forms were distinguished: prismatic, obelisk, and polygonal forms; and non-orthogonal forms: tapering and pyramid, triumphal arch and gate, inclined, spiral and twisted, aerodynamic, and free forms. This classification was developed for the purpose of comparative study of the analyzed Varsovian buildings.

Research has shown that Warsaw has not developed a unique, new, or regional type of high-rise form in relation to the developed list of types of forms implemented globally. Only one of the examined buildings—Warsaw Trade Tower—has regional features, in the establishment of the façade and the stacking blocks of solids referring to the architecture of Warsaw.

The remaining buildings under study are part of the globally developed types of high-rise buildings. On the other hand, the forms and their parameters, although not unique, that are most common in Warsaw were identified, along with a trend in terms of their use.

- -

- The research included studies of twenty-four high-rise buildings erected in Warsaw in the adopted time range.

As a result, the surveyed buildings were classified into a previously defined typology. In addition to the typological classification, the formal features of the buildings under study were also examined: slenderness, the presence of a podium, the relationship of the form to the present context, and the position of the form in relation to the public space in the immediate vicinity. Research has shown that the typological forms present in Warsaw are obelisk, polygonal, tapering, aerodynamic, free, and regional. The most common of these are free forms—41.6%, polygonal forms—25%, and obelisk forms—20.8%.

- -

- On the basis of the conducted research, the most characteristic features of the analyzed buildings were distinguished. Among them, the most common were: the presence of a podium in the study group, frequent reference to the existing buildings in the vicinity with the height of the podium, and bringing the tower part of the form directly to the level of public space.

- -

- The variability of the implementation of the form over time was examined. A trend was distinguished in the projects consisting in moving away from the most common free forms to polygonal forms and obelisks, while increasing the scale of buildings and reducing their average slenderness.

The conducted research and its results were assessed in terms of the role of high-rise buildings in shaping the image of Warsaw. Basic visibility zoning plans, in which high-rise buildings are perceived from verified views, were discussed, including the farthest, distant, and close perspectives. The characteristic elements shaping the city’s image, which is co-defined by high-rise buildings, were recognized. Paths and nodes were indicated as the most common elements on which high-rise buildings acting as landmarks in Warsaw are located.

The presented research recognizes the types of forms and their characteristics for high-rise buildings erected in Warsaw up to 2022. At the same time, on the basis of a distinguished trend, the likely direction of future forms of high-rise buildings in Warsaw was determined.

Further realizations of high-rise buildings should be the subject of future research in terms of their typology. The emerging buildings should be monitored in terms of the possible development of typological forms in Warsaw, the implementation of world forms of buildings that do not exist yet in Warsaw, the introduction of possible local forms, and changes in the features of the types of building forms in terms of their scale, slenderness, and cooperation in creating the image of the city.

The typology presented in the text, together with the conclusions, should be updated. The methodology may serve this purpose and may be a universal basis for such activities in the future.

Funding

The author declares no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Fuhrmann, M. Spatial, social and economical dynamic of contemporary Warsaw–City profile. Cities 2019, 94, 286–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musiał, R. Budynki Wysokie w Przestrzeni Miasta Europejskiego: Analiza Wpływu na Czytelność i Obrazowość Środowiska Miejskiego. Ph.D. Dissertation, Wydział Architektury Politechnika Krakowska, Kraków, Poland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Jóźwik, R. Warunki kształtowania się nowego, zachodniego centrum Warszawy w okresie transformacji ustrojowej. In Centra i Peryferie w Okresie Transformacji Ustrojowej: XXVII Konwersatorium Wiedzy o Mieście; Wolaniuk, A., Ed.; Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Łódzkiego: Łódź, Poland, 2014; pp. 9–17. [Google Scholar]

- Jóźwik, R. Wieżowiec jako element struktury miasta. In Nowoczesność w Architekturze: Nowoczesne Miasto Policentryczne; Witeczek, J., Ed.; Wydział Architektury Politechniki Śląskiej w Gliwicach: Gliwice, Poland, 2009; pp. 193–200. [Google Scholar]

- Jóźwik, R. Znaczenie Nowych Realizacji Architektonicznych w Kształtowaniu Nowej Tożsamości Zachodniej Części Centrum Warszawy. Czasopismo Techniczne. A, Architektura. 2010. (z.7 A/2). pp. 136–140. Available online: https://repozytorium.biblos.pk.edu.pl/resources/33140 (accessed on 23 March 2022).

- Goncikowski, M. The Skyscraper as a Component of Public Space—The Case of Warsaw. Land 2022, 11, 491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pawłowski, A.Z.; Cała, I. Budynki Wysokie; Oficyna Wydawnicza Politechniki Warszawskie: Warsaw, Poland, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Ellis, P.G.; Torcellini, P.A. Simulating tall buildings using EnergyPlus. In Proceedings of the 9th International IBPSA Conference on Building Simulation, Montreal, QC, Canada, 15–18 August 2008; pp. 279–286. [Google Scholar]

- Lynch, K. The Image of the City; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1960. [Google Scholar]

- Lynch, K. Good City Form; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Wejchert, K. Elementy Kompozycji Urbanistycznej; Arkady: Warszawa, Poland, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Oleński, W. Cyfrowa Panorama Warszawy, Arcana GIS Spring 2012. Available online: https://architektura.um.warszawa.pl/documents/12025039/19008716/Olenski_Cyfrowa_panorama_Warszawy.pdf/ff07a726-f978-a4e1-7cc8-0fa55ea63aa2?t=1634497947983 (accessed on 15 March 2022).

- Oleński, W. Postrzeganie Krajobrazu Miasta w Warunkach Wertykalizacji Zabudowy. Doctoral Dissertation, Wydział Architektury Politechniki Krakowskiej, Kraków, Poland, 2014. Available online: http://www.pif.zut.edu.pl//images/pdf/pif-12_pdf/D-02%20Dabrowska-Budzilo.pdf (accessed on 5 March 2022).

- Al-Kodmany, K. Placemaking with Tall Buildings. Urban Des. Int. 2011, 16, 252–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Kodmany, K. Understanding Tall Buildings: A Theory of Placemaking; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Attoe, W. Skylines: Understanding and Molding Urban Silhouettes; Wiley & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Cooke, P. Future Shift for ‘Big Things’: From Starchitecture via Agritecture to Parkitecture. J. Open Innov. 2021, 7, 236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Kodmany, K. Skyscrapers in the Twenty-First Century City: A Global Snapshot. Buildings 2018, 8, 175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gehl, J. Life between Buildings: Using Public Space; Danish Architectural Press: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Gyurkovich, J. Znaczenie form Charakterystycznych dla Kształtowania i Percepcji Przestrzeni. Wybrane Zagadnienia Kompozycji w Architekturze i Urbanistyce; Wydawnictwo Politechniki Krakowskiej: Kraków, Poland, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Gyurkovich, J. Miejskość miasta. In Czasopismo Techniczne; z. 2-A/2007; Wydawnictwo Politechniki Krakowskiej: Kraków, Poland, 2007; pp. 105–118. [Google Scholar]

- Gyurkovich, J. Forma i kontekst. In Czasopismo Techniczne; z. 6-A/2007; Wydawnictwo Politechniki Krakowskiej: Kraków, Poland, 2007; pp. 56–61. [Google Scholar]

- Gyurkovich, J. Architektura w Przestrzeni Miasta. Wybrane Problemy; Wydawnictwo Politechniki Krakowskiej: Kraków, Poland, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Jasiński, A. Znaczenie budynków wysokich i wysokościowych we współczesnej urbanistyce. In Przestrzeń i Forma 10; Wydawnictwo PAN: Gdańsk, Poland, 2008; pp. 233–244. Available online: http://www.pif.zut.edu.pl/pl/pif10---2008/ (accessed on 13 February 2022).

- Appleyard, D. Why Buildings Are Known: A Predictive Tool for Architects and Planners. Environ. Behav. 1969, 1, 131–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appleyard, D. Planning a Pluralist City; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Evans, G.W.; Smith, C.; Pezdek, K. Cognitive Maps and Urban Form. J. Am. Plan. Assoc. 1982, 48, 232–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Council on Tall Buildings and Urban Habitat (CTBUH). Monograph on Planning and Design of Tall Buildings, Vol. Planning and Environmental Criteria for Tall Buildings; American Society of Civil Engineers: New York, NY, USA, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Musiał, R. Game of Associatons: The Shape of a Tall Building. Tech. Trans. Archit. 2015, 9-A, 219–223. [Google Scholar]

- Sev, A.; Tuğrul, F. Integration of Architectural Design with Structural Form in Non Orthogonal High-Rise Buildings. J. Sustain. Archit. Civ. Eng. 2014, 7, 31–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Jencks, C. Skyscrapers–Skyprickers–Skycities; Rizzoli: New York, NY, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Emre Ilgin, H. Space Efficiency in Contemporary Supertall Office Buildings. J. Archit. Eng. 2021, 27, 04021024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Generalova, E.M.; Generalov, V.P. Super-Slender Residential Skyscrapers in New York as a New Direction in High-Rise Buildings Typology. Urban Constr. Archit. 2016, 6, 85–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szołomicki, J.; Golasz-Szołomicka, H. Analysis of technical problems in modern super-slim high-rise residential Buildings. Budownictwo i Architektura 2020, 20, 83–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Kodmany, K. Green Retrofitting Skyscrapers: A Review. Buildings 2014, 4, 683–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeang, K. Ekoscyscrapers and Ecomimesis: New tall building typologies. In Proceedings of the CTBUH 2008 8th World Congress, Dubai, United Arab Emirates, 3–5 March 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Bagley, F. The Mixed- Use Supertall and Hybridization of Program. Int. J. High-Rise Build. 2018, 7, 65–73. [Google Scholar]

- Henn, M.; Fleischmann, M. Novel High-rise Typologies–Towards Vertical Urbanism. In Proceedings of the CTBUH 2015 New York Conference, New York, NY, USA, 26–30 October 2015; Available online: https://www.academia.edu/31608938/Title_Novel_High-rise_Typologies_Towards_Vertical_Urbanism?auto=download (accessed on 5 March 2022).

- Ilgin, H.E. A Search for a New Tall Building Typology: Structural Hybrids. In Proceedings of the LivenARCH 2021: OTHER ARCHITECT/URE(S), Trabzon, Turkey, 28 September 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Czyńska, K. Selected aspects of tall building visual perception–example of European cities. Space&Form 2021, 48, 243–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czyńska, K. Impact of Tall Buildings on Urban Views–the European Approach. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2019, 471, 092047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Techniczne, W. Warunki Techniczne, Jakim Powinny Odpowiadać Budynki i ich Usytuowanie; Dziennik Ustaw Rzeczypospolitej Polskiej: Warszawa, Poland, 2015; p. 1422. [Google Scholar]

- Zahiri, N.; Dezhdar, O.; Faroutam, M. Rethinking of Critical Regionalism in High-Rise Buildings. Buildings 2017, 7, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).