Abstract

To guarantee the right to adequate housing is crucial worldwide, and even more so in Spain, where there is an accumulated delay in public housing policies compared to other European countries. This situation has led to an increase in Catalonia of cooperative housing under a grant-of-use (GoU) model based on collective ownership, and the intention of people to live together, sharing daily life, and collectivizing risks and care-based work. These characteristics may impact on people’s health, but evidence is yet limited. Our study aims to explore the mechanisms that explain the relationship between cooperative housing under a GoU model and health in Catalonia. A descriptive−exploratory qualitative study was carried out. A total of 26 participants from 11 housing cooperatives were interviewed. Our results indicate that the impact of cooperative housing on people’s health is mainly explained by these components: (1) living aligned with their political motivations; (2) legal and economic aspects; (3) communal living; (4) governance, decision-making and participation; and (5) material aspects of the dwelling. Despite having health benefits, the lack of clarity in the Spanish legal framework and public funding makes universal access difficult, but it is a step forward in breaking with the speculative housing dynamics that exist in our context.

1. Introduction

One of the main political and social challenges in many cities around the world is to guarantee the right to adequate housing. The global housing crisis, rooted in capitalism, has meant that housing is not considered as a human right, but a market good and a financial asset [1,2,3].This lack of access and affordability is very evident in the Spanish state, mainly in two ways: (1) the promotion of ownership as the “ideal” tenure, based on cultural and historical aspects [4,5]; and (2) the accumulated delay in public housing policies with respect to other European countries, with a proportion of social housing of just 1.1%, well below the European average [6,7].

Moreover, housing has been recognized as a social determinant of health through different factors: economic and legal aspects; the emotional and social meaning of home; the material conditions of the dwelling; and the physical and social environment of the neighborhood where it is located. In turn, these factors are determined by each country’s housing system, as well as by other macroeconomic and social policies. In addition, the health impacts of housing are modulated by the different axes of social inequality, such as gender, social class, and whether the person is racialized, among other aspects [8,9,10].

In fact, women and nonbinary people have more difficulties in accessing adequate housing [11,12,13]. This vulnerability is explained by the worse economic situation resulting from inequalities in professional opportunity, limited access to or control over economic resources, and disproportionate exposure to gender-based violence [14,15]. Moreover, women are often forced to reduce their working day or even give up their jobs in order to care for dependent people (i.e., children, elderly people, sick people) [16]. Sometimes this reproductive/care-based work is provided by contracting (often in a precarious way) another person, who usually is also a woman, in most occasions a migrant/racialized and/or poor woman, accentuating this precarity [17]. In general, this situation leads women and nonbinary people to suffer from more housing insecurity and homelessness compared with men [18]. On the other hand, it is important to keep in mind that housing is the place where the first relationships between genders develop [19,20]. In this line, the traditional type of house built for decades is not neutral and takes for granted certain characteristics of the hierarchical structure of the nuclear family, reducing and invisibilizing the spaces dedicated for reproductive work [21]. For instance, it favors some activities, giving value to the spaces where these activities happen (for example, the living room, related to rest after productive work outside the home), while it undervalues and hinders the activities linked to reproductive work (for example, half-hidden clotheslines that are difficult to access, narrow kitchens without good natural lighting). In this sense, traditional housing perpetuates the sexual division of labor, is rigid and does not consider the real and changing needs of the people. For all these reasons, it is necessary to generate accessible housing models that consider the sustainability of all lives, putting care at the center [16,21,22,23].

In recent decades, new forms of citizen organizations have emerged that fight for the right to adequate housing, proposing new models of tenure and cohabitation, some of them incorporating feminism-based perspectives [24,25]. Among the different alternatives that are being promoted, cooperative housing under the grant-of-use model stands out. This model takes as a reference the Andel model as well as other consolidated experiences in European and Latin American countries [26,27,28,29,30,31].

1.1. Cooperative Housing: The Grant-of-Use Model

In the cooperative housing under the grant-of-use model (GoU), a group of people organize themselves through a nonprofit cooperative to provide affordable and inclusive housing for the cooperative’s members [32,33,34,35]. The model has three key features: (1) the collective ownership of the housing, which is vested in the cooperative, hindering speculation practices at the individual level; (2) the assignment of grant-of-use as a tenure regime (legal form) where the cooperative grants the use of the housing indefinitely or for a long period of time to the members. The right of use is generally acquired by paying an entry fee that will be returned if (and when) the tenant leaves the cooperative, and is kept by paying an affordable and adaptable monthly fee that is intended to cover the cost of the debt contracted for the construction and subsequent maintenance of the building and the cooperative; and (3) people intentionally choose to live together in community, sharing daily life, and collectivizing risks and care work [32,36,37].

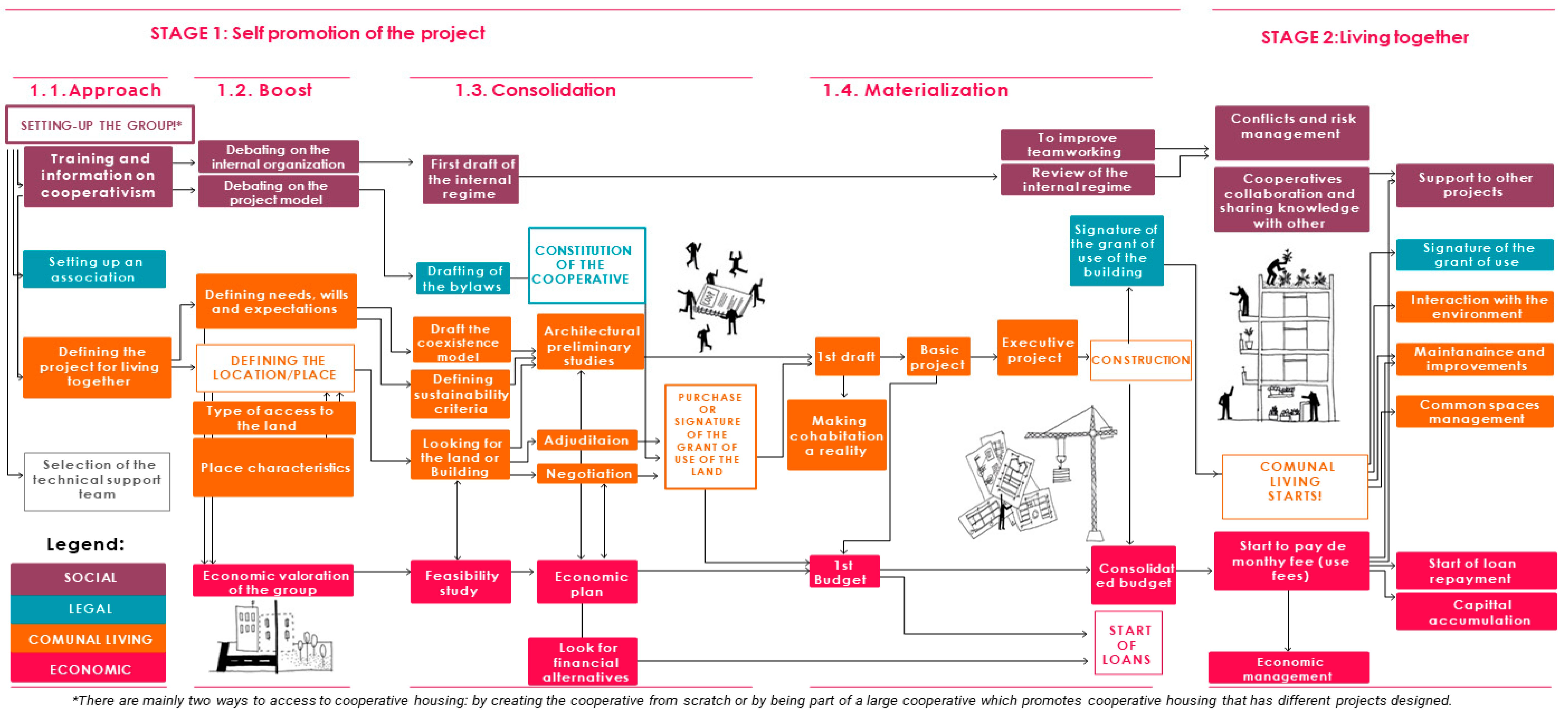

Cooperative housing under the GoU model has two stages: (1) self-promotion of the project (lasting from 4 to 7 years); and (2) living together (currently the grant-of-use is between 30 and 100 years or more). The self-promotion stage triggers a long and exhausting process with different steps that overlap. Figure 1 summarizes these two stages with the different processes and steps involved.

Figure 1.

Stages of the cooperative housing under a GoU model.

The management of the housing cooperative requires good internal organization and a high degree of participation and commitment. Decisions are made democratically through working committees and general meetings. This organization helps the group to become empowered and jointly responsible for the project [34].

According to the Observatory of Cooperative Housing, there are a total of 36 housing cooperatives under the GoU model in Catalonia, which are in different stages of development. Some of them groups are already living together, although most of them are in the first stages. In addition, there are several projects that explicitly incorporate a feminist perspective [38]. As an example, there is the project “Dones Cohabitant” (Women co-living), that for some years has been developed in Catalonia with a feminism-based perspective. The main objectives of this project are: (1) to use everyday life to analyze the role of space in the environment, giving equal value to all spheres of life (i.e., productive, reproductive, community and personal); (2) to recognize the social value of unpaid work and promote a more equitable division between spheres; (3) to break down the public−private divide, between the private sphere of the home and the public sphere, bringing domestic and care work into the public sphere in order to understand it as a social responsibility; (4) to understand that this daily organization has implications for urban design, health and well-being that influence people’s aspirations and expectations; (5) to contribute to democratizing housing policies so that the active participation of women is central to the search for affordable and more equitable housing solutions; and (6) to generate a new cooperative housing market in an already built environment by rehabilitating the current situation through a new form of social organization. There are similar projects run by women in other contexts, such as Mujeda in Uruguay or Frauenwohnprojekt Ro*sa in Vienna.

1.2. Cooperative Housing and Health: What Is Known?

Despite the increase in the number of cooperative housing projects, research on the health effects of these models is still scarce. Most of the available studies have focused primarily on cooperative housing but not specifically on the GoU model. A recent literature review concludes that cooperative housing can improve the health and quality of life of people residing in them mainly due to factors such as: a greater sense of community; increased social support; reduced isolation; and increased physical, emotional, and economic security [39].

The rise of cooperative housing under the GoU model projects and the lack of evidence on the impact on health and quality of life of this model justifies the need for our study. Thus, using qualitative methods and a feminist approach, we aim to explore the mechanisms that explain the relationship between cooperative housing under a GoU model and health and quality of life in Catalonia.

2. Methods

2.1. Design and Theoretical Approach

A descriptive−exploratory qualitative study using face-to-face individual or group semi-structured interviews was undertaken. We used a feminist phenomenological approach as we were interested on the meanings that people built through their subjective experiences in their everyday life, but considering that those are constrained by ideology, politics, language, and power structures [40].

2.2. Recruitment and Sampling

Our sampling design followed a theoretical, conceptual plan that determined the typologies or profiles of the sample unit.

We applied the following criteria:

- (1)

- At the cooperative level: we contacted housing cooperatives from Barcelona and Catalonia that were in different phases (i.e., (1) self-promotion: approach; (2) self-promotion: boost; (3) self-promotion: consolidation; (4) self-promotion: materialization and (5) living together) as we wanted to reflect the impact of the process on health and quality of life. In addition, we also considered the different characteristics of the projects (i.e., urban/rural, number of people involved in the project). A steering committee with expertise in cooperative housing oversaw this project. The members gave us the contact of housing cooperatives they knew. We contacted 13 housing cooperatives that were in different stages. Of the 13 cooperatives contacted, only 2 did not reply to our mail and calls.

- (2)

- At the individual level, once contact with the cooperative was made, the cooperatives explained to their members our research project and decided who was going to participate. They also decided if the interviews would be individual or in a group. To guarantee that different profiles of people were interviewed, we asked them specifically if they knew someone who met some of the characteristics that may have impact on the experience, such as gender, age, household composition, time in the cooperative, and work status (maximum variation sampling). Once the interview was done, we asked the interviewee if they knew other persons who would be interested in participating in an interview (snowball sampling). Only one of the persons contacted through one participant declined to be interviewed because of lack of time, but she referred us to another one.

2.3. Data Collection and Participants

The interview guide was developed ad hoc and was piloted by one person already living in a cooperative housing and one person who was in the beginning of the process (i.e., self-promoting approach). The interview guide is available in Appendix A. Interviews were audio or videorecorded, fully transcribed, and anonymized.

Fieldwork started in February 2020 and finished in November 2020. Interviews were conducted in a place of convenience for the participant by AF or AR. A total of 17 interviews (individual or group) were carried out, involving a total of 26 people from 11 cooperative housing projects. Interviews lasted from 36 to 85 min. Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, most of the interviews were conducted by video conference. Thematic saturation (i.e., no new information supplied in the data) was achieved at interview 13, but we conducted 4 additional interviews with people who presented some characteristics that where not present in the previous interviews. These 4 interviews did not add new information.

Table 1 shows a summary of the characteristics of the cooperative housing projects and Table 2 the main characteristics of the participants.

Table 1.

Summary of the characteristics of the cooperative housing under GoU model projects (elaborated by authors 2022).

Table 2.

Description of main characteristics of the participants (elaborated by the authors 2022).

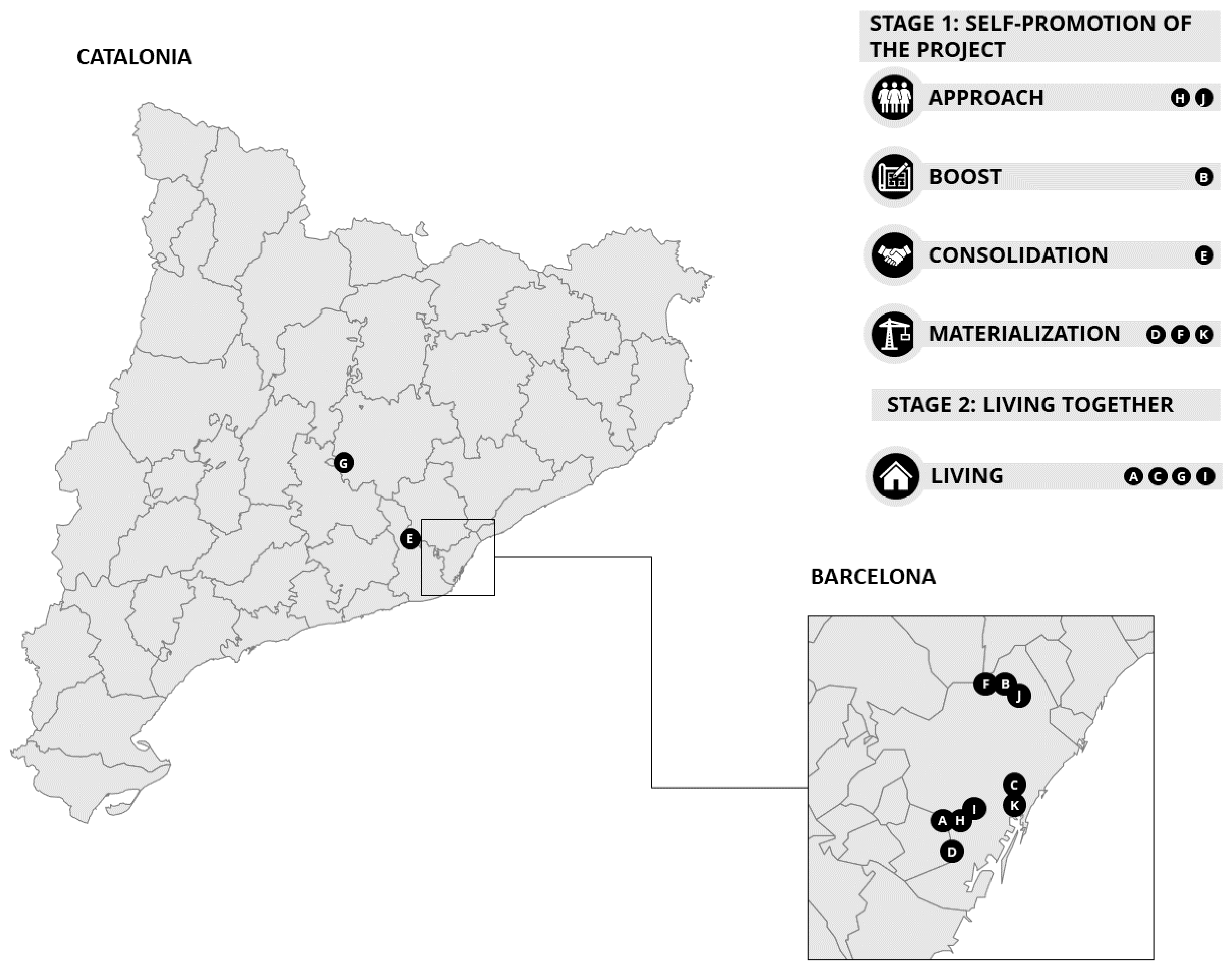

Nine out of the 11 cooperatives were in Barcelona (urban area), and 2 in a rural area in Catalonia. The cooperatives were at different stages of development: 2 cooperatives were in the phase of self-promotion: approach (3 interviewees), 1 cooperative was in self-promotion: boost (3 interviewees), 1 cooperative was in self-promotion: consolidation (1 interview), 3 cooperatives were already in the stage of materialization (6 interviewees) and finally in 4 cooperatives participants were already living together (13 interviewees). The length of time the interviewees had been living in the cooperatives ranged from 4 months to 13 years. Figure 2 shows the location of the GoU housing cooperative projects in Barcelona and Catalonia.

Figure 2.

Cooperative housing under the GoU model in Catalonia and Barcelona.

Regarding the 26 participants, 18 identified themselves as women and 8 as men. The age of the participants ranged from 23 to 64 years old and 11 of the participants lived or will live alone (10 out of the 11 were women). All participants gave informed consent, and the study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Parc de Salut Mar (ref. 2020/9372).

3. Results

From the discourse of the participants, five major components were identified, which are further subdivided into categories that can explain the impact of cooperative housing under the GoU model on health and quality of life. These components are: (1) political motivations; (2) legal and economic aspects; (3) communal living; (4) governance, decision-making and participation; and (5) material aspects of the dwelling. Table 3 summarizes the results.

Table 3.

Summary of the main results (elaborated by the authors 2022).

3.1. Aspects Related to the Political Motivations of the Participants

The participants referred to previous political experiences related to cooperativism, to the right to adequate housing, to the environment or feminism. In this sense, they considered that it was important to be coherent and to live aligned with their principles and values, embodying politics in their daily lives. This would generate greater well-being and satisfaction:

At the beginning it was more of a motivational, political, and ideological idea of saying, “Fuck, that’s cool, right?”. Something that goes through something as personal as housing, but that can also have a certain transformation when it comes to politics and the way of understanding what housing is.(P1, woman, 45 years old, currently living in “A”).

3.2. Aspects Related to the Legal and Economic Form

3.2.1. The Stability Fostered by the Grant-of-Use Model

The stability generated by the grant-of-use allowed participants to develop a stable life project in the same place. This generated feelings of rootedness, of belonging, and made it easier to feel part of a community. This security was related to feelings of peace and tranquility and a decrease in the anxiety that would be generated by not having a stable place. This feeling of rootedness generated greater emotional well-being:

(…) for me the most significant word is stability, security, and accompaniment; that is, you feel safe because the owner is not going to come and tell you that your contract is over, “Go away”(P3 woman, 65 years old, currently living in “C”).

In contrast, among the young people interviewed, the fact of committing for such a long time was perceived as a feeling of anxiety

(…) a disadvantage is the fact of being young and not having a very stable life project… and it is difficult to say that you will live in a city for so many years and from then on, as a cooperative is a very long-term project (...) it conditions you a lot (...)(P11, man, 24 years old, currently living in “A”).

However, the participants mentioned that one characteristic of the model was its flexibility, since it allowed the inhabitants to disengage from the project by renouncing the right of use, recovering their initial contribution, or by taking a leave of absence if for personal reasons it was necessary to leave the project just for a specific period.

3.2.2. Initial Capital Contribution (Entry Fee)

In general, the participants agreed that access to cooperative housing was restricted to those who could afford to pay an initial contribution that was still high (between EUR 5000 and 30,000 depending on the project), although lower than the contribution in the free market. This barrier related to access generates contradictions and emotional discomfort in some participants, as they felt that they were not being consistent with the model by privileging some groups over others:

(…) cooperative housing as it exists now is not seen as a solution for housing (...) in a certain way we have a privileged position, (...) well, I am going to say it in a very caricatural way: it is a middle-class project and we leave the poor classes with their housing problems, right?(P24, man, 40 years old, not living in but currently designing “H”).

On the other hand, if the project became more expensive as it progressed, and the initial contribution increased, it could generate discouragement and anguish, even causing some people to have to leave the project for economic reasons, which generated frustration and discomfort in the group, as well as an increase in stress due to the impact on the project if a person left (i.e., looking for a new person, doubts about the feasibility of the project).

Even so, some projects developed internal mechanisms to help pay the initial contribution for those who were unable to do so. This generated satisfaction and reinforced commitment to the project.

3.2.3. Monthly Fee

The fact that the monthly fee was in most of the projects below the market fee generated peace of mind as it provided financial security:

You feel safe because you know that you pay a right of use that it is not going to change too much... and every five years, you don’t have to make a contract... you feel good... .... I live alone(P3, woman, 64 years old, currently living in “C”).

In addition, the fact that the monthly payments were more affordable allowed people to reduce their productive time (i.e., working hours) and be able to dedicate more time to leisure, social life or non-productive projects outside the capitalist system which would lead to a better quality of life and well-being:

One of the things that will allow me to live in a building like this will be that I will not have to pay such a high rent. I will be able to work less on things that I don’t want and more on things that make me happy. Yes, I will have less money, but I will be able to dedicate my time to things that really interest me and I will not be subject to a wheel, to the system that makes you feel like a mouse(P26, women, 48 years old, under construction in “K”).

3.3. Communal Living

This component was the most present in the participants’ discourse. This was expressed at two different levels: (1) at the internal level, which implied the relationship with the members of the cooperative; and (2) at the external level, which implied the relationship with the environment and people living in the neighborhood.

3.3.1. Sharing Daily Life and Mutual Support

This was related to the explicit intention to live in community, sharing daily life, and generating a chosen family that supported each other and shared resources. Participants related this to feelings of security, trust, reduced feelings of loneliness, and tranquility. This idea was especially important among women living alone and/or outside the normative family model:

For me, being able to live together and share my day-to-day life with the people I love is the part that most excites me. I think that almost all of us are from abroad and here we haven’t created a heteronormative nuclear family. You must bear in mind that we are a feminist cooperative and most of us are lesbians and transgender people. Moreover, we are at an age when we are losing the traditional families of origin, as many of them are dying. So, we need to create an alternative, valid, transformative family network that is really here(P2, woman, 43 years old, currently designing “B”).

In addition, having a network of people with whom you live and that supports you can have a positive impact on reducing the use of health services, as one participant told us:

I have a mental health problem. There are people who know about it and when they see that I am decompensating they let me know. This means that I can get care earlier and avoid hospitalization(P16 woman, 55 years old, currently living in “G”).

3.3.2. Collectivization of Care Work and Risks

Closely related to the sharing of daily life and the creation of mutual support networks was the explicit decision by the members of the cooperative to collectivize risks and care work. This generates feelings of security, tranquility, a sense of belonging to a community, reduced the feeling of loneliness and isolation, and improved emotional well-being:

If I become dependent in an environment where I have people I trust and where people take care of each other, it reassures me to think that there will be someone who will look after me, or that there will be someone who will come to knock on the door to see how I am or even that if at any given moment I have mobility needs that do not correspond to my apartment, there is a certain flexibility in being able to change apartments within the same dwelling. So, I think this creates a lot of peace of mind(P25, woman, 31 years old, currently designing “J”).

As we have already commented, this collectivization of the reproductive work was especially important for people who had chosen to live alone, outside of normative family models or LGBTIQ+ people:

(…) there is also the motivation of not having to go back into the closet as we get older, you know? I mean, not having to go to a nursing home … this would be difficult, isn’t it? Because nursing homes are not friendly for LGTBIQ+ people, (…) the care provided there is in the normative way (…) we want to go forward, we want to become old together and in our homes(P9, woman, 40 years old, currently designing “B”).

Another aspect related to the collectivization of care was found in shared “parenting”, where not only parents or legal guardians participated, but the whole community. An example of this was “la escoleta”, (the “tiny school”) a space that was established in the cooperative housing “A” during the COVID-19 pandemic to respond to the needs of children:

(…) the community does this, doesn’t it? That you can, that you can share, that in the face of certain needs you can find joint solutions, no? Collective solutions. There have also been people who are not parents and who have also participated in this Escoleta, no? Because they had time due to personal circumstances, work, etcetera. (…) This is the sense of community, which is the one that costs a lot to take place in a normal building(P3, man, 60 years old, living in “A”).

In any case, the participants explained that it was also important to make it very clear what the child-rearing guidelines and limits were, in order to avoid conflicts.

On the other hand, the collectivization of economic risk—establishing internal solidarity mechanisms such as collective funds—was pointed out as one of the mechanisms that could have the greatest positive impact on emotional health. An example of this can be found in cooperative “A”, where during the pandemic, as some of the inhabitants were fired from their jobs, the resistance box was activated:

The Commission of Economy, before anyone said anything, sent a message: “If someone has problems to pay the rent…” informing us that there was the collective fund that was made for those moments…In what world happens that they tell you before saying anything, “If you have problems with the rent, not to be worried! There is the collective fund! We can support you” (…) this is also mental health(P4, two men, 23 and 24 years old, currently living in” A”).

3.3.3. Common Spaces

Common areas were perceived as facilitators of social interaction:

(…) the common spaces are like the town square, they facilitate interaction: sometimes you go there just to gossip, sometimes you have very interesting conversations with someone, and, sometimes, decisions are made”(P7,woman, 34 years old, currently under rehabilitation in “E”).

Common areas were also spaces where things could happen that promoted healthy behaviours. The participants identified both physical spaces (i.e., bicycle parking, collective kitchens, coworking, multipurpose rooms, urban gardens, care rooms where there may have been saunas, bathtubs, etc.) and non-physical spaces (i.e., sustainable consumption groups, ecological baskets). Participants also explained that the shared activities and social interaction produced in these spaces were related to feelings of companionship, security, and protection, avoiding feelings of loneliness, and generating well-being and happiness.

The visibility of care and reproductive work could also be seen in some of the communal spaces, such as the shared washing machine area. Sharing these spaces also generated a sense of pride, as it was related to political motivations that broke with heteropatriarchal logics:

Sharing the washing machine...my aunt says to me, “What are you doing, sharing the washing machine”, and I replied, “Well it’s people like me, young people, nothing happens”, (…) this makes me think that sharing a washing machine, is a...political fact, it’s funny isn’t it?(P21, women, 32 years old, currently under construction in “F”).

However, in those projects with a high degree of communalism, participants reported that it may have had a negative impact on health, related to the ease of transmission of some diseases (they commented on flu and gastrointestinal viruses) but also related to the loss of privacy:

A very clear issue is that if you want to have sex with yourself or with someone else, it must be at a certain time, at a certain place...(laughs). Now, for instance, when I stay alone at home, my sexuality comes out, you know… but I am not sure nobody will come through the door(P14 man, 48 years old, currently living in “G”).

3.3.4. Relationship with the Neighborhood Community Where the Dwelling Is Located

The participants believed that the community network created with the environment improved the feelings of belonging to a place and of rootedness, increasing security related to the perception of the environment and decreasing the fear of suffering violence. All this generated feelings of tranquility:

(…) of not feeling isolated, of not feeling that if something happens to me and I shout in the middle of the square because I’m going to be mugged or assaulted, nobody is going to come out on the street to defend anybody, you know? That people know what is happening to the other person and they care, right? That sense of community, that you care about the space where you live and you care about the people you live with. I think that for me that connection with the neighborhood gives me peace of mind… feeling a sense of community again(P9, woman, 40 years old, currently designing “B”).

In addition, thinking beyond the building itself, generating networks with the rest of the neighbors, social entities, other cooperatives, and social movements in the territory, could be a driving force for other changes. In fact, some projects gave up spaces in the cooperative to recover community spaces for the neighbors—spaces that could become health assets benefiting both the member of the cooperatives and the neighbors of the surrounding area.

3.4. Aspects Related to Governance, Decision-Making, and Participation

3.4.1. Governance and Participation

The people interviewed express that the self-organization of the cooperative and the collective decision-making process requires time and learning. Participation is articulated through different spaces where decisions are made collectively and democratically. There are general meetings where all the members participate and where the strategic lines of the cooperative-which will change according to the different moments-are set. In addition, operative working groups were generated to respond to these strategic lines (e.g., architecture, care, economy). Participating in these spaces made it easier for people to bond with the project, generating feelings of belonging, excitement, happiness, as they felt that they were creating together the space where they were going to live. It also helped the groups to get to know each other, developing bonds of collective trust. On the other hand, it also generated fatigue, frustration, conflicts when expectations or opinions were very different, and discomfort that led to greater stress, especially in the early stages, when the group was less mature and the uncertainty related to the project was greater:

There are times when you can be a bit stressed or overwhelmed because you say, “I already have a lot of things in my life and on top of that, this is added”. Maybe it means once a week or every two weeks having a meeting, preparing work, doing the general assembly on Saturday, right? But on the other hand, this process is also good because, in the end, all these people that are working on the project will be the ones who will go to live there and therefore it gives you the time to get to know the people, to accept them(P22, woman, 35 years old, currently designing “H”).

3.4.2. Inequalities, Roles, and Attitudes in Participation

The people interviewed pointed out that not all people had the same chance to participate in decision-making, either due to lack of time or lack of knowledge. This increased stress and discomfort, generating the feeling of not being sufficiently involved in the project and of not being up to the task. However, to facilitate the participation of all the people, different mechanisms were implemented taking into account both the capabilities and skills of people and reproductive work (i.e., planning meetings at different times, generating a rotating group for taking care of the children, documenting the agreements in writing so that they could be informed despite not having participated in the meeting, training so that all the people have the same knowledge).

On the other hand, they commented that sometimes sexist and paternalistic attitudes were shown that hindered the decision-making process. Although some projects integrated a feminist perspective, the interviewees pointed out that sometimes gender-based power dynamics were still evident. For instance, the working groups related to care work were still feminized and undervalued, while the more technical working groups (i.e., architecture or economics) were masculinized. A mechanism generated by some groups to solve this risk was that all the people rotated through the different working groups:

We have established criteria so that there is parity in the working groups, but it is just politically correct, because in the end it is always the same people who are in charge (...) the women who put a lot of work into the processes end up very burnt out, for example, one woman (name) who has a son and who has put a lot of work into the communication working group is now very burnt out, or this other woman (name) who is also very powerful, she is now on leave from working groups! It is true that in the long run women work a lot, they are very powerful and they are recognized, but they get tired sooner, and that means something: because as well as doing this very powerful work, they are doing seven more! (…) the men have a longer career because they only do this one work… however, from the outside our cooperative seems quite “correct”(P1-woman, 45 years old, currently living in “A”).

These attitudes and the reproduction of gender roles produced conflict, frustration, and emotional discomfort in the group.

Some projects had generated anti-sexist protocols that were applied in the daily life of the community.

3.4.3. Technical Support during the Process

As already mentioned, the development of the model required making many complex decisions. This reason, together with the lack of clear legal regulations and the fact that the housing development process required expert knowledge on different disciplines (i.e., architecture, legal, economic, conflict management), meant that most of the projects hired technical support. The participants pointed out that this technical support was essential, but it was expensive and should be assumed by the administration, if the model wanted to be publicly promoted. When technical support responded to the needs and expectations of the group, it generated trust and peace of mind, reducing fears:

We don’t have any worries (…) we feel super-supported…we are not suffering for technical aspects... we trust them [technical team] completely(P4 woman, 53 years old, under construction “D”).

Otherwise, it increased stress and insecurity among the people involved in the project.

3.5. Aspects Related to the Dwelling

3.5.1. Material Aspects of the Dwelling

In those cases where construction or renovation criteria related to energy efficiency had been considered, the dwellings had better ventilation and light, and people considered that their physical health had improved, if they were already living there, or would improve by reducing allergies, avoiding colds, improving pulmonary health, and reducing muscular pains:

In general, the cross ventilation will improve my lungs, for sure, I am convinced,(P21, female, 36 years old, in construction “F”).

However, the participants commented that even though the projects wanted to include these criteria, sometimes it was not possible because, although they recognized that in the long term they could reduce costs, in the short term they increased the initial monetary contribution and may not be affordable.

3.5.2. Location of the Dwelling

Other aspects that can have a negative impact were not related to the material aspects of building, but with its location.

Participants commented on some fears related to gentrifying the neighborhood, especially when the cooperative was in a disadvantaged area. This fear could generate stress and discomfort:

My greatest fear is to gentrify the neighborhood or that we become like a small and isolated island (…) although the community commission is working with the neighborhood, getting closer to the neighborhood, right? (…) But this is a neighborhood that has been historically impoverished (…) so let’s hope (...) that we don’t have a counterproductive effect(P9, woman, 40 years old, currently designing “B”).

One of the mechanisms to minimize this risk was to generate networks and synergies with neighborhood associations and other community-based projects that existed in the territory.

(...) on the ground floor, we have the premises... traditionally in the neighborhood they have always been occupied by bars and restaurants. We have decided not to rent it, something that other cooperatives have done, but in our case, as the gentrification and touristification in the neighborhood is so serious and so savage, we decided that we will make a space for the neighborhood, promoting cultural and artistic activities and projects that take place in the neighborhood(P26, women, 48 years old, currently under construction in “K”).

In addition, if the dwelling was far from where the person spent the most time or there were no nearby services, stress and fatigue could be generated.

(…) if you don’t spend time in the neighborhood because you work in other place, or whatever, then it is stressful, this coming and going, this tiredness with commuting(P2, woman, 43 years old, currently designing “B”).

Participants from projects located in a rural or semi-rural context highlighted that the proximity to green areas generated well-being, even though they were more isolated.

4. A Brief Reflection on the Impact of the Components According to the Different Stages of the Cooperative

These components differ in relevance and impact depending on the stage of the cooperative housing project. The participants explained that in the initial stage, especially when the project was being designed from scratch, the aspects related to “governance, decision-making and participation” as well as to “legal and economic” aspects were more relevant. This was the most critical and complex stage. The group was not very mature and had to face many uncertainties and complex decisions. It was a stressful stage where emotional support and mutual care were considered essential. When the construction and rehabilitation of the building began, many of the worries and discomforts disappeared, since the project was being “materialized”. This moment generated a lot of excitement and pride. The aspects related to “communal living” and “material aspects and location of the dwelling” were more important when the cooperative began to live together, since the health benefits of sharing the daily life and living in a “healthy” building appeared. The aspects related to “governance, decision-making, and participation” were still important, as new challenges related to coexistence and expectations appeared. However, the group was now more mature to face conflicts. It was also when the economic benefits (i.e., affordable monthly fee) and those related to stability began to materialize. The benefits derived from mutual support and the feeling of living in coherence with political principles would be present throughout the process.

5. Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study carried out in a South European country that examined the impact of a specific model of co-housing, cooperative housing under the GoU model, on health and quality of life in the general population, including participants who were at different stages of the project. Our results indicate that the impact of cooperative housing under a GoU model on health and quality of life would be reflected in the improvement of emotional and social health. According to the mental health components proposed by Waterman [41], this impact would be explained by: (1) an increase in emotional well-being through the affective domain by generating positive emotions; but also thought the cognitive domain, since people would be more satisfied by living in line with their political ideals and because of the feeling of ontological security produced by stability; (2) an increase in social well-being, by feeling part of a community and by the security generated by the support networks and mutual care that were established; and (3) by an increase in psychological well-being, by improving self-esteem, autonomy, personal development, and life purpose.

The mechanisms involved in this relationship were related with what has been called “soft infrastructure” that includes shared intentions, interpersonal relationships, shared governance, and collective work. Other mechanisms involved, such as legal and economic aspects and the material aspects of the dwelling, which have been called “hard infrastructure”, would also have an impact on health and quality of life [42].

Thus, our results are consistent with other studies that have indicated that the impact of cooperative housing on health and quality of life is explained by the increased trust, security, sense of community, motivation, opportunity for socialization, and the creation of friendships generated by communal living [43,44,45]. The benefits of collectivizing risks and care work, which in other studies is referred as “communal coping” [46], have also been shown in other studies, suggesting that it reduces stress, by generating a sense of security and a decrease in loneliness. On the other hand, communal living does not only imply establishing ties with the people from the cooperative, but also the intentionality of creating relationships with the environment. This relationship with the neighborhood or the environment is created by generating formal and informal social support networks and promoting social resources. This may reduce social isolation, facilitating rootedness to the neighborhood [47,48,49,50,51]. In fact, some projects, due to their location, may have a strong political and strategic component, having the intention to rehabilitate the area where they are located.

Aspects related to the legal form and the collective economic structure would also impact health, especially through the stability generated by the grant of use, and the economic affordability, especially when the monthly payment is lower than the market fee. The literature has systematically pointed out that the capacity for long-term projection, which in this study would be related to the legal form of the grant of use, has an impact on people’s well-being and quality of life [52].

On the other hand, the material aspects of the dwelling will have an impact depending on the type of rehabilitation or construction carried out. A recent study shows that in some cooperative housing under a GoU model there is lower energy consumption and greater thermal comfort at a lower energy cost, which impacts not only on health but also on the economic burden [53].

Although the perceived impacts are mostly positive, it should be noted that it is a complex, time-consuming, and tiring process, which is more present in the initial stages. In fact, our findings about governance, decision-making, and participation agree with other studies that have pointed out the painstaking process of making decisions by consensus, describing long meetings and frustrating differences in vision for the community, individual desires, and interpersonal styles. Others described hurtful miscommunications, conflict-ridden social dynamics, and profoundly challenging decisions about community rules and guidelines [54]. On the other hand, participation in self-management and dwelling design generates greater satisfaction and well-being from the possibility of control over one’s own life. In addition, decision-making by consensus promotes a sense of belonging and shared values [34,55,56,57]. However, for this consensus to be achieved, there is a need for a high degree of participation and to have the skills to debate and engage in dialogue, being able to manage conflicts and reach agreements. This is one of the key aspects since interpersonal relationships are crossed by axes of power, which place people in asymmetrical positions. Thus, in our study we have seen how, even though many of the projects include a feminist perspective, we are still immersed in a heteropatriarchal, colonialist, and capitalist structure, which means that there are still discriminatory attitudes and behaviors that generate discomfort. The following situations illustrate this fact: that there were still more women than men carrying out the care or parenting commissions; men used to speak for a longer time during the meetings and commissions than women; although more women than men were involved in cooperative housing projects, more men were exercising the role of representatives of the cooperative; and women, due mainly to reproductive work, such as the care of children, were less able to participate in the meetings. This suggests that the transformative potential of the model, from this feminist perspective, will not be achieved if social reproduction policies are not explicitly addressed.

Actually, one of the major challenges is the fact that in the Spanish context there is not a clear and specific legal framework, or a clear political commitment related to the cooperative housing under the GoU model. This hinders the development of public policies to support the model and make it more affordable. In the interviews the lack of accessibility, mainly due to economic issues, was widely reported and coincided with the results of a report presented in the Catalan context that examines the economic affordability of cooperative housing. This report evidenced that currently the financing and economic affordability of the model is a structural element that makes it less inclusive and hampers universal access, mainly due to the initial contribution required [58]. This is consistent with the few successful experiences in low-income populations [59,60] since some of them were forced to abandon the project because of economic barriers [61]. In this sense, a greater involvement of public administrations to facilitate the implementation of the model is needed, but as we have already said, these policies must go beyond housing and incorporate other areas related to migration and labor policies, to name but a few. We have already commented in the introduction that there is a problem regarding adequate housing access, especially for women and people from more disadvantage positions. It is worth noting that, among the 26 participants in this study, 14 were people who did not fit into the heteropatriarchal normative family (women who decided to live alone and/or sexual dissidents), but these people were (except one) European, middle-class citizens that had a privileged position. Participants from different cooperatives explained to us that some of their colleagues in the project had to drop out for economic reasons, many of them were single women and some of them were migrant women or transgender people, who are in a very disadvantaged position socially and economically. To change people’s living conditions, to really put care at the center and to improve people’s quality of life, courageous policies are needed to build spaces that support new forms of social organization [62].

6. Strengths and Limitations

The study has the following strengths: it is the first study carried out in our context that examines the impact of cooperative housing under the GoU model on health and quality of life in the general population, including participants who were at different stages of the project. In addition, we have implemented quality criteria mechanisms such as: reflexivity; note-taking; recording and transcription of the interviews, which allowed auditing by any interested person; and validation of the results with the participants. Despite this, several limitations should be considered: first, we have only interviewed people from 11 cooperative housing projects developed in the Catalan context, so our results may not be generalizable. Moreover, most of the cooperatives interviewed (7 out of 11) were in the self-promotion (initial) stage. Although this reflects the Catalan context, it may have impacted in our results, emphasizing the negative aspects of the process. However, participants already living cooperatively also pointed out that the self-promotion stage was a critical and stressful moment. Second, the fieldwork was affected by the COVID-19 pandemic, which may have influenced participation, as well as the discourses of the people interviewed, who may have idealized what it means to live in community (especially those who are not yet living in community). Finally, it should be added that there could be a selection bias, as we have not interviewed people who have left the projects, nor the children. So, we are only reflecting the vision of the most motivated adults.

7. Future Research

Future studies could investigate if our results can be replicated in quantitative studies. It would also be interesting to know the impact that cooperative housing may have on the people living in the neighborhood where it is located; as well as the perception of the children who are living in these cooperatives. It would also be important to incorporate feminist perspectives in future analyses, studying the composition of the cooperative, and the uses of time and space in housing, according to gender. On the other hand, it would be important to delve deeper into how the different stages of the process impact on the health and quality of life of the participants, since the risks and the mechanisms for managing them differ, as well as the maturity of the group to deal with them.

8. Conclusions

In conclusion, cooperative housing under the GoU model can have a positive impact on people’s health and quality of life, mainly through the benefits derived from sharing daily life; collectivizing risks and care work; and through the security provided by the long-term grant of use. However, the lack of clarity of the Spanish legal framework and the lack of public funding make it difficult to enable universal access, although it represents a step forward as it breaks with the speculative dynamics related to housing that exist in our context. When public policies recognize and promote these new models, including public funding and support to facilitate their implementation and access, cooperative housing under the GoU model will become a truly inclusive and transformative model, which has the potential to generate healthier, more sustainable, more feminist and fairer communities.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.R., A.M.N., C.B., J.C., K.P., C.G, L.D. and A.F.; formal analysis, A.R. and A.F.; investigation, A.R. and A.F.; methodology, A.M.N., C.B., J.C., K.P. and A.F.; validation, A.R., A.M.N., C.B., J.C., K.P., C.G., L.D. and A.F.; writing—original draft, A.R. and A.F.; writing—review and editing, A.R., A.M.N., C.B., J.C., K.P., C.G., L.D. and A.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Carlos III Institute of Health, Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness (Spain), awarded in 2018 under the Health Strategy Action 2013–2016, within the National Research Program oriented to Societal Challenges, within the Technical, Scientific and Innovation Research National Plan 2013–2016, grant number PI18/01761, “Impacto en salud y bienestar de la vivienda cooperativa en cesión de uso” co-funded with European Union ERDF funds (European Regional Development Fund)”.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of Parc de Salut Mar (protocol code 2020/9372, 31 July 2020).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all the people who have shared their time with us, explaining their experiences, feelings, and desires, and the Housing and Health group of the Barcelona Public Health Agency, for their support and cooperation.

Conflicts of Interest

Some of the authors live in a cooperative housing under a grant-of-use model and/or are linked to a foundation that promotes this model. Specifically, C.G. is a technician at the LaCol foundation a cooperative of architects promoting cooperative housing and an inhabitant, L.D. is a technician at the LaDinamo Foundation for cooperative housing under the grant-of-use model and a future inhabitant, and C.B. is the president of the LaDinano Foundation.

Appendix A. Interview Guide

| Topics | Examples of Questions | |

| A. People Not Living (Self-Promotion Stage) | B. People Living | |

| Definition and process | How would you define cooperative housing? How was/is the process going? Did you know anyone? What aspects do you like the most? What aspects could be improved? How have you felt/are you feeling in the different stages of the process? How do you think this impacts on your health and quality of life? | |

| Main differences between traditional housing and cooperative housing under the GoU model | What do you think makes cooperative housing different from traditional housing? What are the main aspects that make it different? What are the most positive aspects? What aspects do you think that can be negative when compared to traditional housing? For example,, in your case that you are already living in, what has changed? | |

| Motivations/reasons: | What were your motivations? If it does not emerge in the discourse, ask directly about:

| |

| Risk management | What are your fears about this project? What risk management mechanisms have the cooperative considered? (Some tips that can help to elicit the discourse: what happens if someone cannot pay; what happens if someone has an accident and renovations have to be made to the dwelling; what happens if a couple breaks up; have you planned for the process of ageing?) What solidarity mechanisms do you have? | |

| Expectations on the impact of cooperative housing on their health. Mechanisms. | You have commented that the following differential aspects are positive (naming each one the aspects separately: How do you think this could impact on your health and well-being? (If it does not emerge in the discourse, ask directly about physical, emotional and social health.) You have commented that the following differential aspects are negative (naming each one the aspects separately: How do you think this could impact on your health and well-being? (If it does not emerge in the discourse, ask directly about physical, emotional and social health.) | |

| Perceived impacts on their health | Not applicable | Can you explain me how have your health and quality of life changed since you have been living here? Why do you think that this has happened? (If it does not emerge in the discourse, ask directly about physical, emotional and social health.) |

References

- García Pérez, E.; Janoschka, M. Derecho a La Vivienda y Crisis Económica: La Vivienda Como Problema En La Actual Crisis Económica. Ciudad. Y Territ. Estud. Territ. 2016, 48, 213–228. [Google Scholar]

- Harvey, D. Diecisiete Contradicciones y El Fin Del Capitalismo; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2014; Volume 53, ISBN 9788578110796. [Google Scholar]

- Peiró, I. La Crisis de Vivienda En Las Ciudades: Causas, Efectos y Respuestas; Instituto Municipal de la Vivienda y Rehabilitación de Barcelona: Barcelona, Spain, 2019; Available online: https://www.habitatge.barcelona/sites/default/files/dialegs_habitatge-es_web2.pdf (accessed on 20 September 2022).

- Observatori D’antropologia del Conflicte urbà De Proletarios a Propietarios, o Los Origines de La Lógica Espacial Del Urbanismo Neoliberal. Available online: https://observatoriconflicteurba.org/2016/05/23/de-proletarios-a-propietarios-o-los-origines-de-la-logica-espacial-del-urbanismo-neoliberal/ (accessed on 24 August 2022).

- Rodríguez, R. La Política de Vivienda En España En El Contexto Europeo: Deudas y Retos. Revista. Invi. 2010, 25, 125–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Housing Europe. Available online: https://www.housingeurope.eu/ (accessed on 26 June 2022).

- Pittini, A.; Laino, E. Housing Review: The Nuts and Bolts of European Social Housing Systems, Brussels. CECODHAS Hous. Eur. Obs. 2012, 1, 91. [Google Scholar]

- Borrell, C.; Malmusi, D.; Artazcoz, L.; Diez, E.; Rodríguez-Sanz, I.P.y.M.; Campos, P.; Merino, B.; Ramírez, R.; Benach, J.; Escolar, A.; et al. Propuesta de Políticas e Intervenciones Para Reducir Las Desigualdades Sociales En Salud En España. Gac. Sanit. 2012, 26, 182–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novoa, A.M.; Bosch, J.; Díaz, F.; Malmusi, D.; Darnell, M.; Trilla, C. El Impacto de La Crisis En La Relación Entre Vivienda y Salud. Políticas de Buenas Prácticas Para Reducir Las Desigualdades En Salud Asociadas Con Las Condiciones de Vivienda. Gac. Sanit. 2014, 28, 44–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vásquez-Vera, C.; Fernández, A.; Borrell, C. Gender-Based Inequalities in the Effects of Housing on Health: A Critical Review. SSM Popul. Health 2022, 17, 101068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glick, J.L.; Lopez, A.; Pollock, M.; Theall, K.P. “Housing Insecurity Seems to Almost Go Hand in Hand with Being Trans”: Housing Stress among Transgender and Gender Non-Conforming Individuals in New Orleans. J. Urban Health 2019, 96, 751–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reed, E.; Gupta, J.; Biradavolu, M.; Devireddy, V.; Blankenship, K.M. The Role of Housing in Determining HIV Risk among Female Sex Workers in Andhra Pradesh, India: Considering Women’s Life Contexts. Soc. Sci. Med. 2011, 72, 710–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilkinson, E.; Ortega-Alcázar, I. Stranger Danger? The Intersectional Impacts of Shared Housing on Young People’s Health & Wellbeing. Health Place 2019, 60, 102191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, S. Women and Housing or Feminist Housing Analysis? Hous. Stud. 1986, 1, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Somerville, P. Tenure, Gender and Household Structure. Hous Stud 1994, 9, 329–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Power, E.R.; Mee, K.J. Housing: An Infrastructure of Care. Hous. Stud. 2020, 35, 484–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orozco, A. Cadenas Globales de Cuidado. Serie Genero, Migración y Desarrollo. Documento de Trabajo 2. Santo Domingo: Naciones Unidas-Instraw Cuad. De Trab. 2007, pp. 1–9. Available online: https://trainingcentre.unwomen.org/instraw-library/2009-R-MIG-GLO-GLO-SP.pdf (accessed on 20 September 2022).

- Barbieri, D.; Huchet, M.; Janeckova, H.; Karu, M.; Luminari, D.; Madarova, Z.; Paats, M.; Reingarde, J. Poverty, Gender and Intersecting Inequalities in the EU: Review of the Implementation of Area A: Women and Poverty of the Beijing Platform for Action; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2016; pp. 1–2. Available online: https://eige.europa.eu/publications/poverty-gender-and-intersecting-inequalities-in-the-eu (accessed on 20 September 2022).

- Satsangi, M. Feminist Epistemologies and the Social Relations of Housing Provision. Hous. Theory Soc. 2011, 28, 398–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saarikangas, K. Model Houses for Model Families. In Gender, Ideology and the Modern Dwelling; The Type-Planned Houses of the 1940s in Finland; Helsinki: Suomen Historiallinen, Seura, 1993; 403 p (Studia Historica: 45). [Google Scholar]

- Col-lectiu Punt 6. Urbanismo Feminista. In Por Una Transformación Radical de Los Espacios de Vida; Virus Editorial i Distribuïdora: Barcelona, Spain, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Valdivia Gutiérrez, B. La Ciudad Cuidadora. Calidad de Vida Urbana Desde Una Perspectiva Feminista. Degree-Universidad Politécnica de Cataluña, Barcelona. 2021. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/10803/671506 (accessed on 20 September 2022).

- Mogollón García, I.; Fernández Cubero, A.; Arquitecturas Del Cuidado. Viviendas Colaborativas Para Personas Mayores. Un Acercamiento al Contexto Vasco y Las Realidades Europeas. 2016, p. 268. Available online: https://www.emakunde.euskadi.eus/contenidos/informacion/publicaciones_bekak/es_def/adjuntos/beca.2015.1.arquitecturas.del.cuidado.pdf (accessed on 20 September 2022).

- Hagbert, P.; Larsen, H.G.; Thörn, H.; Wasshede, C. Contemporary Co-Housing in Europe; Routledge: Oxon, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2019; ISBN 9780429450174. [Google Scholar]

- Communities over Commodities. 2018. Available online: https://homesforall.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/Communities-Over-Commodities_Full-Report.pdf (accessed on 20 September 2022).

- Bredenoord, J. Self-Managed Cooperative Housing by Mutual-Assistance as Introduced in Central America between 2004 and 2016 the Attractiveness of the ‘FUCVAM’ Model of Uruguay. J. Archit. Eng. Technol. 2017, 6, 188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabré, E.; Andrés, A. La Borda: A Case Study on the Implementation of Cooperative Housing in Catalonia. Int. J. Hous. Policy 2018, 18, 412–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Celobert SCCL. Estudi de Formes Alternatives d’accés i Tinença de l’habitatge. Consell Nacional de Joventut de Catalunya. 2014, pp. 1–64. Available online: https://celobert.coop/projecte/guia-alternatives-acces-habitatge/ (accessed on 20 September 2022).

- Solanas Domínguez, M. Las Cooperativas de Vivienda Uruguayas Como Sistema de Producción Social Del Hábitat y Autogestión de Barrios Del Sueño de La Casa Apropiada a La Utopía de La Ciudad Apropiable. Degree-Universidad Pablo de Olavide, Sevilla. 2016. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/10433/2430 (accessed on 20 September 2022).

- Turmo, R. Andel: El Model Escandinau d’Accés a l’Habitatge. Finestra Oberta 2004, 39, 1–74. [Google Scholar]

- Barenstein, J.D.; Koch, P.; Sanjines, D.; Assandri, C.; Matonte, C.; Osorio, D.; Sarachu, G. Struggles for the Decommodification of Housing: The Politics of Housing Cooperatives in Uruguay and Switzerland. Hous. Stud. 2022, 37, 955–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sostre Civic, SCCL. Celobert. Les Claus de l’habitatge Cooperatiu En Cessió d’ús. 2017. Available online: https://sostrecivic.coop/biblio/biblio_5.pdf (accessed on 20 September 2022).

- Perviure SCCL, Celobert SCCL, Fil a l’Agulla. Cohabitatge Amb Cures i Atenció a Les Persones. 2019, 34. Available online: https://filalagulla.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/GuiaPerviureAmbCures.pdf (accessed on 20 September 2022).

- Girbés-Peco, S.; Foraster, M.J.; Mara, L.C.; Morlà-Folch, T. The Role of the Democratic Organization in the La Borda Housing Cooperative in Spain. Habitat Int. 2020, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arañó, I.B.; García, D.M.; Giménez, L.O.; Pascau, A.S. Els Habitatges Cooperatius. Sistema de Cessió d’ús.; Departament d’Empresa i Treball; Generalitat de Catalunya: Barcelona, Spain, 2008; ISBN 9788439379188. [Google Scholar]

- Vestro Urban, D. Living Together-Cohousing Ideas and Realities around the World; Division of Urban and Regional Studies, Royal Institute of Technology in Collaboration with Kollektivhus NU: Stockholm, Sweden, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- LaDinamo. Fundació per a L’habitatge Cooperatiu en Cessió d’ús. Available online: https://ladinamofundacio.org/ (accessed on 26 June 2022).

- Llargavista Observatori de l’Habitatge Cooperatiu. Available online: https://llargavista.coop/ (accessed on 27 June 2022).

- Carrere, J.; Reyes, A.; Oliveras, L.; Fernández, A.; Peralta, A.; Novoa, A.M.; Pérez, K.; Borrell, C. The Effects of Cohousing Model on People’s Health and Wellbeing: A Scoping Review. Public Health Rev. 2020, 41, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simms, E.-M.; Stawarska, B. Introduction: Concepts and Methods in Interdisciplinary Feminist Phenomenology. Janus Head 2014, 13, 6–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bornstein, M.H.; Davidson, L.; Keyes, C.M.L.; Moore, K.A. Dimensions of Well-Being and Mental Health in Adulthood: Corey L.M. Keyes and Mary Beth Waterman. In Well-Being; Psychology Press: East Sussex, UK, 2003; Volume 20AD, pp. 470–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarvis, H. Towards a Deeper Understanding of the Social Architecture of Co-Housing: Evidence from the UK, USA and Australia. Urban Res. Pract. 2015, 8, 93–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puplampu, V.; Matthews, E.; Puplampu, G.; Gross, M.; Pathak, S.; Peters, S. The Impact of Cohousing on Older Adults’ Quality of Life. Can. J. Aging 2020, 39, 406–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chum, K.; Fitzhenry, G.; Robinson, K.; Murphy, M.; Phan, D.; Alvarez, J.; Hand, C.; Laliberte Rudman, D.; McGrath, C. Examining Community-Based Housing Models to Support Aging in Place: A Scoping Review. Gerontologist 2020, 62, e178–e192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caldenby, C.; Hagbert, P.W.C. The Social Logic of Space. In Contempora; Hagbert, P., Larsen, H.G., Thörn, H., Wasshede, C., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Glass, A.P.; Vander Plaats, R.S. A Conceptual Model for Aging Better Together Intentionally. J. Aging Stud. 2013, 27, 428–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glass, A.P. Resident-Managed Elder Intentional Neighborhoods: Do They Promote Social Resources for Older Adults? J. Gerontol. Soc. Work 2016, 59, 554–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hudson, J.; Scanlon, K.; Fernández, M.; With, A.; Saeed, S. The Wider Benefits of Cohousing: The Case of Bridport; An LSE London Research Project for Bridport Cohousing Final Report; 2019. Available online: http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/id/eprint/106103 (accessed on 20 September 2022).

- Kehl, K.; Then, V. Community and Civil Society Returns of Multi-Generation Cohousing in Germany. J. Civ. Soc. 2013, 9, 41–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labit, A. Self-Managed Co-Housing in the Context of an Ageing Population in Europe. Urban Res. Pract. 2015, 8, 32–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiu, M.L. The Effects of Cohousing on the Social Housing System: The Case of the Threshold Centre. Neth. J. Hous. Built Environ. 2015, 30, 631–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dupuis, A.; Thorns, D.C. Home, Home Ownership and the Search for Ontological Security. Sociol. Rev. 1998, 46, 24–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soldado, J.M. Avaluació Energètica i de Qualitat de l’aire Interior En Projectes de Cohabitatge Cooperatiu a Catalunya [Treball Fi de Grau Universitat Politécnica de Catalunya]. Bachelor’s Thesis, Universitat Politècnica de Catalunya, Catalonia, Spain, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Markle, E.A.; Rodgers, R.; Sanchez, W.; Ballou, M. Social Support in the Cohousing Model of Community: A Mixed-Methods Analysis. Community Dev. 2015, 46, 616–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altus, D.E.; Mathews, R.M. Comparing the Satisfaction of Rural Seniors with Housing Co-Ops and Congregate Apartments: Is Home Ownership Important? J. Hous. Elder. 2002, 16, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, M.; Rodman, M.C. Accessibility and Quality of Life in Housing Cooperatives. Environ. Behav. 1994, 26, 49–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lubik, A.; Kosatsky, T. Public Health Should Promote Co-Operative Housing and Cohousing. Can. J. Public Health 2019, 110, 121–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fundaciócoop57; La Dinamo; Sostre Civic, Holon, Goteo, Coopdevs. Assequibilitat Econòmica de l’habitatge Cooperatiu En Cessió d’ús: Diagnosi, Reptes i Propostes. Barcelona: XES. 2021. Available online: https://xes.cat/2021/11/25/reptes-en-lassequibilitat-de-lhabitatge-cooperatiu-en-cessio-dus/ (accessed on 20 September 2022).

- Boyer, R. Grassroots Innovation for Urban Sustainability. Environ. Plan. A Econ. Space 2015, 45, 320–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatterton, P. Towards an Agenda for Post-Carbon Cities: Lessons from Lilac, the Uk’s First Ecological, Affordable Cohousing Community. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 2013, 37, 1654–1674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyer, R. Sociotechnical Transitions and Urban Planning: A Case Study of Eco-Cohousing in Tompkins County, New York. J. Plan Educ. Res. 2014, 34, 451–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iglesias Varela, B.; Sánchez Moya, A. Entrepatios, Ecofeminismos, En Construcción. In Economía Feminista, Políticas Públicas y Acción Comunitaria; Tirant lo Blanch: Barcelona, Spain, 2022; pp. 201–215. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).