Abstract

The establishment of new housing initiatives for older people begins with the participation of (future) residents. This study explored how participation is experienced by both facilitators and (future) residents and what lessons are learned regarding the facilitation of meaningful participation. Participation was studied through semi-structured interviews and focus group sessions from the perspective of 34 (future) residents and facilitators involved in participation processes in a diverse set of four housing projects from the Netherlands. The results focused on three phases: the initiation phase, the concepting and development phase, and the transition towards an established form of group housing. From the outset of such processes, it was important to involve all relevant stakeholders and to create a shared vision about the participation process. Discussions in small groups, the use of references, creative elements, and the creation of the right atmosphere were experienced as valuable during the concepting and design phase. In the third phase, the role of the organisation and residents needed to be discussed again. Participation should be a continuous process, during which trust, communication and having an open attitude are key. This study showed how innovative approaches can contribute to the creation of an environment in which older people can impact the actual design of housing, and make it more inclusive.

1. Introduction

An increasing number of older people are expected to age in place [1]. In the Netherlands, many residential care homes have been phased out in recent years, creating a gap between ageing in place and institutional care [2]. Most older people, particularly those who live independently, are not in need of continuous care and support. However, ageing in place may lead to isolation. A wide range of collective housing initiatives offer an alternative form of ageing in place [2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9]. A collective housing facility is a type of housing inside a larger building that has housing as its main function. It often consists of several housing units, whereby at least two households voluntarily share at least one living space, and, in addition, each have at least one private living space. In the coming years, the Dutch government expects more actions to be taken by municipalities, social housing associations, and market parties in the development of innovative forms of housing [10]. As stated by van Hoof et al. [11], there is a large set of guidelines, building codes, recommendations, and standards on how to design housing for an ageing population that constitute barriers and challenges for independent living. These documents often relate to home modifications and the anthropometric aspects and the layout of dwellings, but they often have a limited application range, as national building practices dictate the applicability and acceptance of the measures.

One way to account for the differences in the needs and attitudes of older people is by actively involving older people in participatory design activities that relate to their housing. Such an approach draws parallels with the participatory design of new technologies and other age-friendly developments, and it helps to overcome old-age exclusion [11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30]. In addition to being able to impact the actual design of collective housing, the success and acceptance of its core concept largely depends on the active participation of older people in concepting and designing these new housing facilities [21]. The World Health Organization (WHO) defined participation as

“a process by which people are enabled to become actively and genuinely involved in defining issues of concern to them, in making decisions about factors that affect their lives, in formulating and implementing policies, in planning, developing and delivering services and in taking action to achieve change” [31](p.11)

The participation of people in decision-making processes that are of concern to them can contribute to the legitimacy and democratic basis of the decisions that are being made, and people’s knowledge based on their personal experiences can be of value in shaping their social and built environment [29,32]. According to the WHO [31], the involvement and participation of older people in all decisions and processes is the single most important principle to facilitate the creation of age-friendly environments. Older people’s experiences should be a starting point for the development of initiatives:

“nothing about us without us!”.

The active involvement of all kinds of end-users in the development of new housing, urban planning, and much larger infrastructure projects [33,34,35,36] is increasingly being stimulated by government actions and international declarations. On an international scale, the Aarhus Convention empowers people with the rights to access information, to participate in decision making in environmental matters, and to seek justice [37]. The United Nations Economic Commission for Europe’s [38] recommendations on public participation aim to assist policymakers, legislators, and public authorities in their daily work of engaging the public in decision-making processes. At the Dutch national level, new legislation is under way to increase the level of participation of inhabitants in the preparation, execution, and evaluation of policies, for instance, on the municipal or provincial level. The goal of the new legislation is to use a so-called Participation Regulation (Dutch: participatieverordening) to stipulate how and in which phase inhabitants are involved in processes [39]. Moreover, the Dutch government is in the process of combining and simplifying the regulations for spatial projects through the new Environment and Planning Act, which is foreseen to come into effect from July 2022. This new act calls for the active participation of all citizens in spatial projects [21,40]. There has been criticism against these new plans, as the new act does not outline any obligations to the developers concerning true participation and does not give a proper definition of what being a participant entails or who needs to be involved (the act only speaks of ‘stakeholders’). Municipality cannot dictate how developers and initiators might organise participation. When applying for a building permit, developers need to explain whether the participation of stakeholders has been organised and what this entails. However, the inclusion of a marginal form of participation does not automatically lead to the refusal of a permit [41].

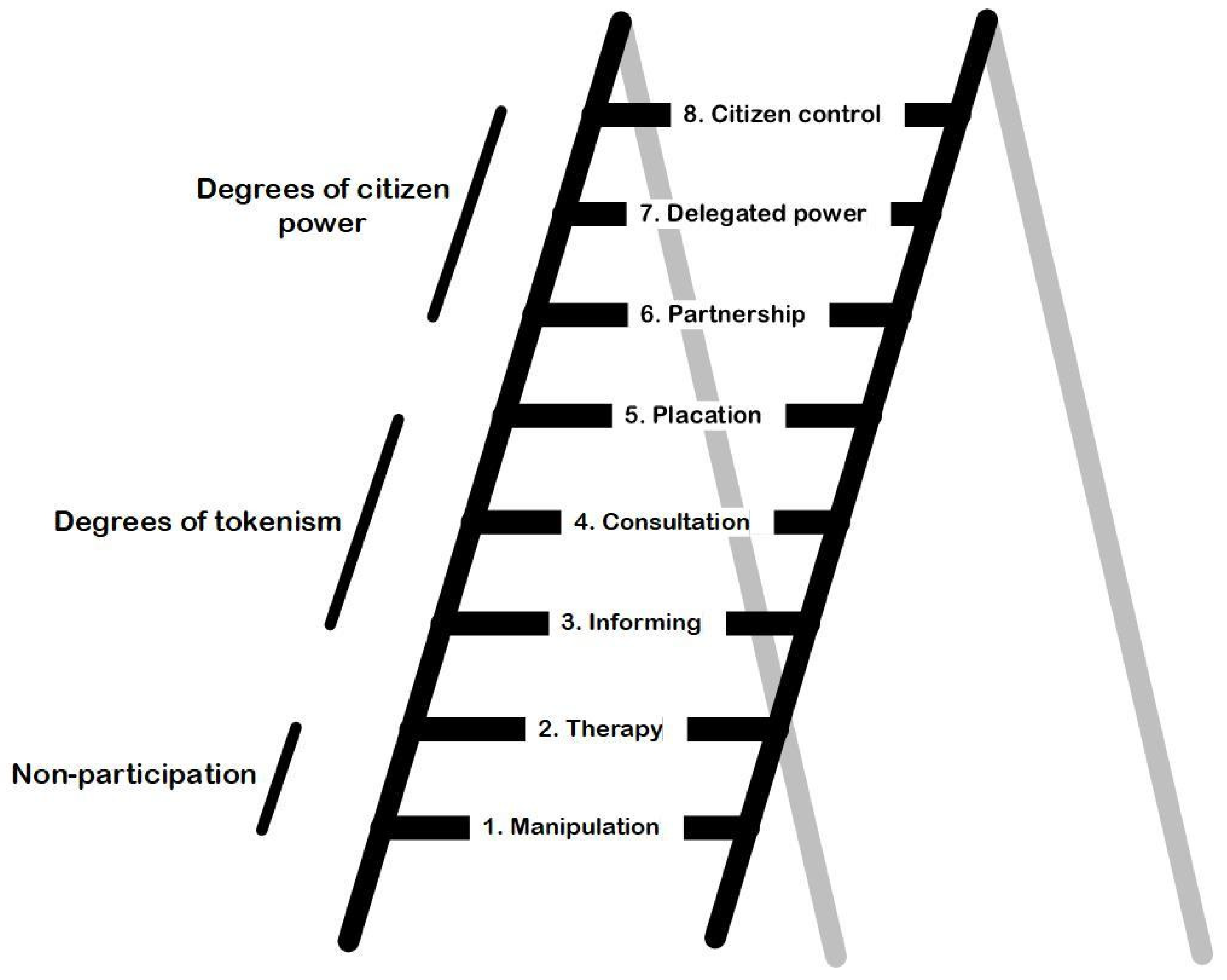

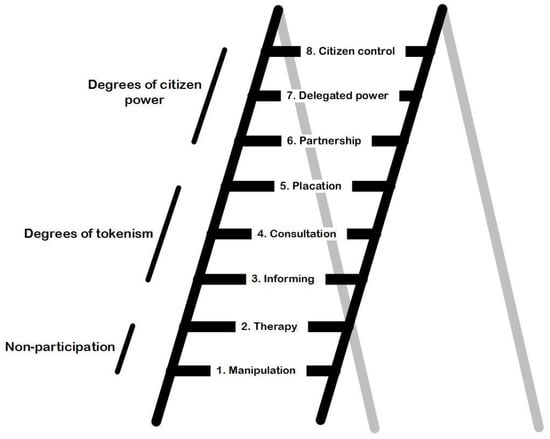

In participation, there is a risk of “tokenism”, where stakeholders have the intention to give older people a voice, or say they have, but in practice, there is no place for the wishes and needs of the people involved or they are overruled by professionals or directors [21]. The widely used ladder of citizen participation by Arnstein [42] (Figure 1) was presented as a potential starting point in shaping the various roles that residents could play in new housing initiatives [21]. As is seen in the figure, the rungs on the ladder show the level of influence participants have. The higher a group is on the ladder, the more power the group has in determining the end product. Van Hoof et al. [21] showed that it should not be a goal in itself to be as high on the ladder as possible. There is no ideal form of participation that is suitable for all situations; the level of participation deemed desirable by different stakeholders can depend on the goals, wishes, and expertise of those involved. However, the use of the participation ladder is valuable, as it can demonstrate where the power and control lie in a project. This is also important because of the bias that exists for existing structures, and this can help prevent certain forms of participation from being overlooked [21].

Figure 1.

The eight rungs of the ladder of citizen participation [21], adapted from Arnstein [42] (p. 217) and taken from van Hoof et al. [21].

In Dutch real-estate development, a shift from ‘no participation’ towards ‘informing’ and ‘consultation’ has steadily taken place in recent years. For instance, panels of end-users are invited to provide feedback in various phases. This often results in tokenistic participation [21]. From Ulbig [43], we learn that having a voice in the proceedings of the political arena may not be enough, and that “a voice that is perceived to have no influence can be more detrimental than not perceiving a voice at all”. Concerning attitudes toward municipal government, perceptions of voice and influence have an impact on feelings of trust and satisfaction, only when citizens have both increased voice and influence. In the case of meaningful participation, the perspectives of people involved are of influence in the decision-making process [44].

Despite the ever-louder calls in society for the participation of potential end-users in the design phases of housing, the appropriateness and actual contribution of the applied methodologies to the final design is still understudied [21]. Collective housing initiatives for older people provide a specific context for participation, and this context can have a particular influence on the process. First of all, older people are involved in the development of a type of home in which they come to live themselves. Secondly, they become part of a group that is characterised by its own dynamics. In addition, life events that are relevant for older people, such as becoming dependent on the care of others and having more free time after retirement, could come into play. A further exploration of the participation process within this particular context is, therefore, of additional value [21]. In relation to housing, van Hoof et al. [21] identified many dos and don’ts regarding the participation of older people in the design and planning phases of new housing. For instance, taking consideration of the specific needs of participants and the provision of regular feedback about the process are advised to facilitate the process of participation [21,45,46]. Brookfield et al. [12] stated that exercises in participatory design could help ensure that environments are better able to facilitate healthy ageing, but at the same time, such engagement can be challenging. The scholars provided critical perspectives on eight “less traditional” engagement techniques, discussing the strengths and limitations of these techniques. De Boer et al. [24] discussed the co-creation of an alternative nursing home model in The Netherlands, for which a conceptual framework was made through co-creation with researchers, practitioners, and older people following an iterative process. The model shows how residential care facilities can take the needs and requirements of older citizens into consideration [24].

Building on the work of van Hoof et al. [21] and Brookfield et al. [12], this study explored different examples in the Netherlands of how older people participate in the development of new housing concepts, varying from the initiation phase, the concepting and design phase, and the phase of the transition to living together. It looked into what their participation added with regard to the overall quality of the process and the end-products, and thus focused on meaningful participation. This study explored how the participation of older people is experienced by both facilitators and (future) residents and determined what lessons were learned about the facilitation of meaningful participation. The joint perspectives of both residents and facilitators within particular settings have not been studied in great detail before. This approach, however, offers a valuable perspective of the participation process, since participation is a situational and interactive process [44].

2. Methodology

The study used a qualitative approach, combining semi-structured, in-depth interviews with focus groups. Studying participation from perspectives of both facilitators and (future) residents added richness to the data and enabled the researchers to conduct a study concerning the challenges and benefits that the participants experienced.

2.1. Sampling: Respondents and Settings

The first cluster of respondents included an initiator, a director, and several staff members of social housing associations who facilitated the participation process (Table 1). Here, this group is referred to as facilitators. The second cluster of respondents included (future) residents who were involved in the development of new housing facilities for older people (Table 1). Purposeful sampling was applied as a technique in the selection of respondents from different housing facilities. This technique is widely used in qualitative research for the identification and selection of information-rich cases [47]. A selection of four collective housing initiatives for older people in The Netherlands was made (shown as Letters A–D in Table 1), in which (future) residents were involved in the development in ways that seemed to go beyond tokenistic involvement. Respondents were recruited from these housing facilities (shown as Letters A–D in Table 1), which varied according to the development phase (initiation, concepting and design, or established) and the methods used to facilitate participation.

Table 1.

Overview of the respondents.

The selected settings provided a broad sample that reflects the current landscape of collective housing initiatives in the Netherlands. There was variation in those who initiated the development of the housing facility (from initiative from a housing association to residents themselves), in the location of the housing facility (varying from rural to urban areas), and in the socio-economic status and ethnic or cultural backgrounds of the residents. In the participation process, often, one or two facilitators were involved alongside a larger group of (future) residents. This is reflected in the number of respondents included in both groups.

Within the selected housing facilities, respondents were recruited by first contacting the initiators of the participation process. This would often lead to contact with an active resident or a member of a resident committee. After this, the snowball sampling method was used. Even though sampling took place within the rather small communities of the selected living groups, where the population was relatively homogeneous, the use of snowballing as a sampling method posed the risk of selecting a homogeneous group of respondents [48]. In order to reduce this risk, residents were asked whether they knew any persons within their setting who might have had different experiences with regard to participation or who perhaps had little involvement in the process. Respondents with varying levels of participation were selected, ranging from members of the resident committee to residents who were minimally involved. Within the living groups, most respondents knew each other or had different pathways of knowing different people. For example, they could contact residents they met during the participation process, or they could contact residents who live in the same corridor, thus providing an entrance to different groups. Using snowballing in this way could even provide access to hard-to-reach respondents [49], making use of the social network in the living facility, for example, in a corridor where people know all their neighbours, even those who might be less active in the community.

In order to provide further insight into the population, an overview of the different settings is provided. The selected cases are all housing initiatives that find themselves in between the extremes of living in an institutionalised setting and independent living [2,50]. The first two settings, A and B, were initiated by a social housing association. In the Netherlands, there is a long tradition of social housing, encapsulating social housing associations which provide housing to people with limited financial resources. Social housing associations own approximately one third of the total housing stock in the Netherlands. Social housing associations are private, non-profit enterprises that work towards achieving their societal mission. Some social housing associations specialise in providing housing for older people [51]. With many residential care homes in the Netherlands being phased out, these social housing associations face a risk of vacant real estate and associated financial losses. Settings A and B are both housing initiatives from the same social housing association. This social housing association is rejuvenating buildings by transforming former residential care homes into collective housing initiatives. Setting A is an intergenerational living community with around 100 apartments, in which older people and students live together. The initiative is located in a city with over 100,000 residents. Setting B is part of the same housing association and consists of a group of around 70 residents living in a town with over 3000 inhabitants. These housing units are mostly social housing units. The selection of both settings A and B provided the opportunity to study the application of the same methods of participation in two different cases with different older people.

In these settings, the participation process occurred in close collaboration with the local community and older people. Future residents and the local community were involved from the very beginning of the process, and they were invited for a kick-off meeting where an open exploration was held. Within this process, regular meetings are held every eight weeks, and the process is rather iterative. In these meetings, wishes are gathered, feedback is provided, and participants are able to ask what is being done with the input they provide. This methodology revolves around a positive and shared working goal among all of the interested stakeholders. The participation process has become structured and embedded within the organisation, and a separate team of employees is now responsible for the transformation and participation process.

A growing number of innovative housing concepts in the Netherlands are initiated by social entrepreneurs, by active members of the community, or by older people themselves. This process often takes several years [2]. In setting C, a collective housing initiative was begun by individuals who are active in their community of older people of Moroccan descent. This collective housing initiative is located in one of the larger cities, and it is targeted at older people of Moroccan descent. This is one of the most prominent groups of migrants in The Netherlands [52]. The housing initiative is still in the process of being realised, and it would house approximately 40 residents within the domain of social housing for people with limited financial resources. Individuals started a foundation to meet the needs of older people within their own community, who were difficult to reach via other support organisations. The foundation organises activities and support. The initiators of the foundation noticed the need for a collective housing initiative, where older people could live together within their own neighbourhood and started the initiative on behalf of themselves. They involved older people and their community themselves, mostly through the use of informal networks. A developer is in the process of purchasing a plot of land from the municipality. There is no budget that would enable the initiators to hire support from a real-estate agency, but they do receive voluntary support from a foundation specialised in collective housing initiatives. Initiators and volunteers involve future residents through informal contact, by collecting their wishes through different methods, and by organising gatherings.

In setting D, a group of older people themselves contacted a social housing association to establish a new collective housing initiative. They live in one of the largest cities in the country. The housing initiative consists of social housing units in a group of around 30 residents. A small group of older people initiated the project and found potential future residents who would also want to live in their community. In the first few years, they explored the field of collective housing. They contacted the social housing association and municipality, and the group received additional funding. Members of the group regularly came together in different meetings to discuss plans and ideas with the different stakeholders. The process was guided by a facilitator. Workgroups were formed to explore various themes with future residents, for example, on how to live together. These future residents visited other reference sites, attended courses, and used more creative methods, for example, by making drawings of their ideal housing situation.

Studying the participation processes of these four diverse settings with the shared context of group housing for older people, provided the opportunity to draw lessons learned that could be valuable for similar projects with the same context (i.e., group housing for older people) that wish to engage with potential end-users.

2.2. Data Collection

Semi-structured interviews (n = 20) were held through online video calls using Skype, Microsoft Teams, or by telephone, depending on the preference of the respondent (Table 1). Interviews were held between March and December 2020 during the height of the COVID-19 pandemic, during which the national government of the Netherlands enacted restrictions regarding social distancing and working from home. All interviews were recorded and transcribed verbatim. The interviews lasted for approximately 90 min each.

Interviews were conducted based on a topic list. The themes of the topic lists were derived from a literature study, including the work of Dedding and Slager [44], van Hoof et al. [21], and Rusinovic et al. [2]. There were two topic lists, one for facilitators and one for residents (Appendix A and Appendix B). The topic list contained topics grouped around a number of main themes: (i) processes/phases in which participation took place, (ii) methods of participation, (iii) the degree of participation, (iv) the revenues/results of participation, and preconditions. The topic list allowed us to gain insight into the respondents’ perceptions and experiences regarding participation.

Three focus groups with older people (n = 16, of which two persons had also been interviewed) were held between December 2020 and June 2021 (Table 1). The sessions were organised in two of the housing facilities (A and D) and in a community centre (C), because this last project was still in an exploratory phase. One researcher moderated the semi-structured focus groups based on a topic list (Appendix C), and the main researcher made fieldnotes. Before each focus group, the topic list was adjusted by both researchers to fit the specific situation. In the focus group with women of Moroccan descent, the session was supported by an interpreter. Each focus group lasted 90 min. The interactive discussion between respondents with different experiences and preferences led to additional information.

2.3. Data Analysis

The interviews and focus groups were anonymised, elaborated, and analysed thematically. For this thematic analysis, a qualitative analysis software package (Atlas.ti 9) was used. In line with the ‘abductive analysis’ approach developed by Tavory and Timmermans [53], the analysis consisted of an iterative process of working with the empirical materials in relation to the literature on participation. This approach included both deductive and inductive reasoning. Based on the existing literature, codes were used, such as ‘level of participation’ and ‘method for participation’, but some codes were generated inductively, for instance, regarding the different lessons learned by respondents, such as embedding an open attitude within the organisation.

2.4. Rigour

To reinforce the credibility of the research, the topic list was validated within the project team of five researchers and, in addition, by five experts working in the field of co-housing for older people, including small- and medium-sized enterprises and stakeholder associations. The researcher who moderated the focus groups and the researcher who made fieldnotes discussed the first impressions of the focus group within three days. During the process, the research team came together to discuss the findings of the interviews and focus groups. In order to maximise the credibility of the analysis, a member check interview using the synthesised data was carried out individually with four respondents through online video calls using Microsoft Teams or by telephone [54]. After the data analysis, the codes and conclusions were discussed with respondents, which provided an opportunity to check and nuance the findings.

2.5. Ethical Considerations

During the data collection, data cleaning, and dissemination, confidentiality was addressed. Informed consent was obtained from all of the respondents. At the beginning of the interviews that were conducted by telephone, Skype, or Microsoft Teams, the researcher read the informed consent statement, and the respondent could state their informed consent. After the interview, the informed consent form was signed and sent to the researcher. During the focus groups, respondents were asked to read and sign the informed consent statement at the beginning of the focus group. After the data were collected, a ‘clean’ data set was created, which did not contain details regarding names or addresses. A limited case description of the chosen housing initiatives was given, and details were left out. It was explicitly considered, while using quotations, whether this could be traced back to one of the respondents via deductive disclosure. We removed additional details in the quotations. The quotations included in this article can only be traced by the researchers.

3. Results

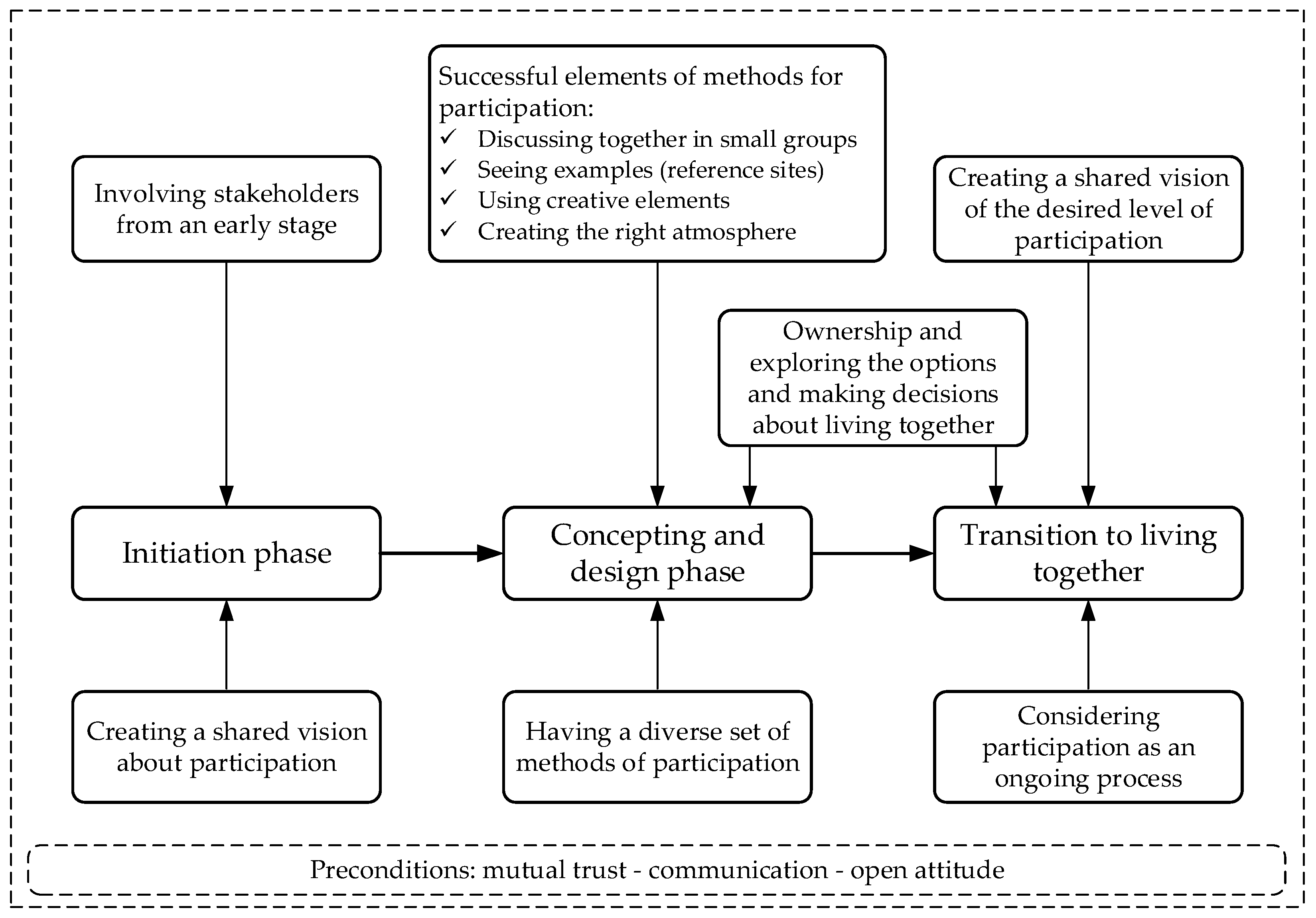

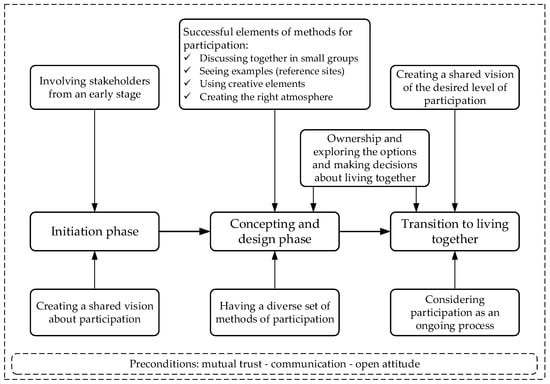

In order to illustrate (1) how the participation of older people in the development of new housing facilities is experienced by both facilitators of the participation process and (future) residents, and (2) how meaningful participation can be facilitated, the process of the development is discussed chronologically, moving from (1) the initiation phase, to (2) the concepting and development phase, to (3) the point where the transition is made to an established form of group housing. For each phase, the main results are presented. Figure 2 provides an overview of lessons learned for each phase, which are discussed in the following sections. This does not mean that phases are mutually exclusive, as development is often an iterative process which involves an overlap between each of the phases.

Figure 2.

Lessons learned from experienced methods to facilitate meaningful participation.

3.1. Initiation Phase

At the start of a new project, there are two important organisational elements that require attention: (1) the involvement of (future) residents from an early phase and (2) the creation of a shared vision about the actual involvement of (future) residents.

3.1.1. Involvement from an Early Phase

According to facilitators, participation entails more than asking for feedback in a later phase of development. It should ideally set out with an open exploration of the wishes of future residents at the start. As one employee from a social housing facility stated:

“This is a very important topic for me: involvement right from the very start. It shouldn’t be like: “OK, we will start with renovation works. Here is the plan, now you can share your feedback”. It is all about involving residents right from the start, about developing the plan together”(Facilitator, Setting A and B)

“During the first meeting, which took place in the building that was going to be renovated, we asked three open questions: (1) How do you want to live when you get older? (2) What do you need in order to do so? (3) What will you do to get there? Residents could write their answers down on sticky notes, and they were stuck onto festival flags that were attached to a big garland. The most important starting point is: What do they <the residents> want? It’s about them.”(Facilitator, Setting A and B)

“[It is a] tabula rasa: We start with an open exploration, and then you’ll see what follows”(Facilitator, Setting A and B)

According to the facilitators, early involvement provides space for the inclusion of the wishes and needs of future residents. In one of the cases (A), this led to the creation of an intergenerational living community, as the idea was raised by residents at the start during a round of open exploration. Residents also emphasised early involvement. In their perception, this could contribute to a feeling of involvement in, and enthusiasm and pride for, the project. As one of the residents explained:

“I have to say, we built this together. Together, right from the start. And I have to say that you can only conclude that it is ideal, for us, for someone who is older! … Yes, I do feel proud!”(Resident, Setting D)

As stated by residents, this does not mean that every (future) resident would like to be involved from the start. Nevertheless, residents stated that being provided with the opportunity for participation and getting feedback about what is being done with the input of people who are involved in the participation process can contribute to a deeper involvement further on in the project or the feeling of being content with the living group in a later phase. As one resident explained:

“Right before the renovation, [the existing building] really looked like a nursing home. So, because I have seen the changes that were made together during the process, I sometimes turn a blind eye for the little things. Those things that people who enter the building after the renovation for the first time really feel irritated about. […] I think the house looks amazing, whereas new people may complain.”(Resident, Setting A)

Apart from involving residents, involving different relevant stakeholders from the start was mentioned by both facilitators and residents. In two of the cases (setting A and B) in which a transformation of existing property took place, problems in a later phase related to the interaction between care professionals and residents. For instance, in case A, the manager of the care organisation was involved from an early phase, but nurses who already worked in the building were not involved in the process. Some residents felt that problems that were experienced while living together could have been prevented if nurses had also been involved in an earlier phase. With their participation, they could have shared (practical) knowledge about what living together with more dependent people entails according to residents. In addition, their involvement could have contributed to a feeling of shared ownership.

In order to be able to involve people, facilitators found it important to gain insight at an early phase into who the future residents would be and to learn more about their backgrounds and the local community. Having an eye for diversity, also within seemingly homogeneous groups, was advised. Furthermore, a more informal and personal approach was also mentioned to be essential. Within setting C—the initiative for older people of Moroccan descent—this was of particular importance as stated by the initiator. As the initiator explained:

“In order to get to know people—and I know that sounds easier than it is—I believe you first have to broaden your view and have to do a preliminary investigation so to say. […] By visiting organisations, people, key-figures in the neighbourhood. First, you need to invest in having good relationships and find out who the people really are, and what are their needs. And you need to be aware of diversity. Don’t think you are dealing with a homogeneous group.”(Facilitator, Setting C)

As is shown in cases A and B, creating a sense of urgency among potential residents, as well as experimenting with innovative or provocative approaches in reaching people, were reported to be important. The following statement of a director exemplifies this:

“The first time the organisation hosted a kick-off meeting, almost no-one showed up for the session. That makes you wonder. So, we tried a more radical approach, and put a sign in front of the building saying “Due to a lack of interest: building will be demolished”. The next time we organised the meeting the whole hall was full with people.”(Facilitator, Setting A and B)

Overall, both groups of respondents, those involved in the organisation of participation and (future) residents themselves, saw clear benefits in the involvement of (future) residents and other stakeholders from the outset.

3.1.2. Creating a Shared Vision about Participation Together with (Future) Residents

In most cases, a plan for the participation process was formed during the process itself. Facilitators experimented with different methods of participation during the process and did not articulate ideas about what topics to involve residents in, nor about the limits and the level of participation in advance. In cases A and B, however, there was a vision within the organisation about the participation process before it began. Facilitators considered this to be a success factor, as it created a shared goal to work towards as well as a direction. This vision, however, was not always shared with all of the (future) residents and was not co-designed with (future) residents. Some residents, when looking back, felt that they would have liked to know more about this vision right from the beginning, as this could have helped them stay involved during the process.

“I would have liked to know beforehand what the process looked like and the general idea behind it. I heard about it, after everything was finished. For this reason, I sometimes lost my interest.”(Resident, Setting A)

In the discussions that took place after the focus groups and interviews, some residents also mentioned that this was the first time that they talked about the actual participation process. They stated that they would have liked a discussion about participation before the start of the process, as they thought this could have helped shape the participation process to match their needs and could have made clearer what could be expected from the facilitators and the end-product.

3.2. Concepting and Design Phase

For the involvement of older people in the concepting and design phase, some methods for participation were experienced as more suitable to stimulate thinking about how one would like to live in the future. After an overview of the methods used in the cases studied, the following aspects are discussed in the subsections below: discussion together in small groups, seeing examples of possibilities for group housing, and the use of creative elements. A range of methods was used to facilitate participation. An overview of the methods for the facilitation of participation that were used in the cases is given in Table 2.

Table 2.

Overview of methods used to initiate participation in the concepting and design phase.

Thinking about growing older and how people want to live when they grow old can be a difficult experience according to facilitators and (future) residents. Some people do not actively think about their future; some aspects of getting older and a potential future loss of independence may even be a sensitive topic. Other aspects are simply too abstract and hard to imagine if the actual event has not yet taken shape, for example, how living in a new housing initiative is experienced when using a wheeled walker or wheelchair. Methods that were reported to be the most successful in this phase included the following aspects: (1) discussion together in small groups, (2) seeing examples of possibilities for group housing, and (3) the use of creative elements. In addition, (4) the creation of the right atmosphere was also reported to be a success factor during the concepting and design phase.

3.2.1. Discussing Together in Small Groups

Both facilitators and residents within all settings believed that small-group discussions were a beneficial method for participation. Groups of six to eight people seemed to be the most fitting, as this scale provided sufficient space for everyone to talk.

“We see that when we organise a plenary meeting, that no one speaks up, or only a very few people. And then we came up with the idea to form groups of six to eight persons. That really means something for the organisation of the meeting, because you need a moderator for every table. We had three sessions with 100 to 150 people in one day, that means a large number of tables and a huge time investment. So, we wondered if should we really do that? But in the end, it felt right to do it like this and the effort really paid off. So, the next time, we did it again. We want to facilitate as many people as possible to have their say.”(Facilitator, Setting A and B)

Facilitators mentioned that small-group discussions were also beneficial, as they created an environment where residents could explore their housing project together. Themes that were explored together in this phase also included talking about how to live together in the future.

“They all have their own apartment, but they also have shared spaces and activities which they need to discuss. Such as, ‘what do we want, and why?’ Because if you don’t discuss these things in advance, it is likely that problems will arise later on. When you discuss this together, in a relaxed and playful manner, then it is often a lot easier than when you discuss it after problems have arisen.”(Facilitator, Setting C)

Small-group sessions can contribute to community building, even before living together, according to both facilitators and residents. For example, one of the residents in setting C said that discussing the future of their living group in small groups together facilitated a connection between the residents and made the process even more motivating.

Facilitators also mentioned the benefits small-group discussions can have in being confronted with—in their view—unrealistic recurring ideas or recurring themes, such as residents who expected to have the same amount of space as they had in their former dwellings. During a small-group session, such expectations and desires could be discussed together instead of repeatedly in individual conversations. Small groups were found to have advantages over a single, larger group, in which it was found that a negative atmosphere could easily arise.

Furthermore, facilitators mentioned the practical advantages of small-group discussions as well, as, according to facilitators in cases A and B, larger groups could have an impact on the inclusion of older people with hearing impairments.

“Ten people in a group already is too much. Some older people have hearing impairments, so you have to work in small groups so they can hear everything as well.”(Facilitator, Setting A and B)

Advice on other practical measures in relation to this was also given by facilitators. The use of a microphone when chairing such sessions with several smaller groups was mentioned as a solution.

3.2.2. Seeing Examples of Group Housing

Seeing real-life examples of group housing was experienced to be a successful method of gaining knowledge about wishes for the future held by both facilitators and residents. This could provide insight into the possibilities of group housing, which were sometimes difficult to imagine. A good example of this was seen when groups in different settings visited reference sites. Visiting these established group housing facilities provided insight into the possibilities of group housing regarding both (1) the architectural design and (2) how living together might be arranged. The groups were also able to see what might be needed in the future when people grow older. As one resident explained:

“We saw that the hallways had to be very broad in order to provide enough space, for example, in case someone would need to use a wheelchair in the future…We hadn’t thought of that at all.”(Resident, Setting D)

“At least eight of [these reference sites] we visited in a group of 10 to 12 people. The co-housing facilities were all so different in how they were designed and how the ownership was arranged. […] So that’s how we got insight into what could work for us, what would be our own ideal.”(Facilitator, Setting C)

Particular attention should be given to architectural design, how to socially arrange living together, and what might be needed in the future when people grow older. In order to construct a plan based on the impressions made during the visit, a group discussion of the findings and conclusions from the visit was considered valuable by residents. In one of the cases (D), the residents made a list of positive and negative aspects based on the experience of the visit to a reference site and translated these into a set of (design) requirements. This set was later presented to the social housing association involved in the project.

Participants stressed the value of visiting reference sites when people were not familiar with the possibilities of group housing. The participants of setting C stressed the importance and value of seeing real-life examples. Some older people of Moroccan descent did not plan to stay in the Netherlands when they grow old and, according to the facilitator of setting C, accordingly, were not always familiar with the possibilities of group housing in the Netherlands. The element of visiting reference sites can contribute to a more inclusive approach.

3.2.3. Using Creative Elements

Another element that seemed to stimulate people to explore their wishes for future housing and to facilitate participation was the use of creative elements. The importance of this element was highlighted by both facilitators and residents in all settings. Creative elements can be used in different ways, for example, through the use of photographs, the construction of mini housing models, and by making drawings in group meetings in order to help imagine an ideal future home, something that can be hard to imagine by just talking and thinking about it. As one resident explained:

“It helps you to explore in a more creative way. To use your imagination if I may say so. When making drawings, and seeing the drawings of others… It helps you think outside of the box.”(Resident, Setting D)

Most residents reported that creative elements could help in imagining their ideal future, and it was something that contributed to creating an atmosphere in which people can get to know each other. Different residents, however, had different preferences for a particular method of engagement, which could even differ between phases. Some residents mentioned that they would not participate if only formal methods would be applied, such as information meetings or discussing formal documents. Other residents preferred these methods. Some of the residents experienced a connection between their preference for a given method (and that of others) and their professional background, education, or specific characteristics such as having good verbal skills.

“Given my work experience, […] during my working life, well, I attended a lot of meetings. I can hold my own.”(Respondent, Setting B)

“Me? Going to an official meeting? That is something for educated people, and I am not one of them. I will not go to those meetings, too much talking. I do like to be involved in more informal activities, and think about how to create a nice community together.”(Resident, Setting B)

One of the residents in setting A mentioned he found the communication of the social housing association regarding the creative methods to be too jovial. It seemed to him that the communication was targeted at an inner crowd at the time, which kept him from going to the session. In setting A, one other resident mentioned that the creative elements used in his case were taken too far for his liking and were even hindering his feeling of being taken seriously. He already felt dissatisfied with the organisation, which could have affected his experience of the chosen method and how it was applied.

“We are no longer schoolchildren, Ms School Teacher! I need something more challenging.”(Resident, Setting A)

Offering a varied mix of methods could be used to include different participants and provide an opportunity for people to be included according to their preferences. The methods used and the way these methods are applied in the participation process should be aligned to wishes and needs of the participants at a given time.

3.2.4. Creating the Right Atmosphere

During the process of concepting and design, methods that contributed to the creation of the right atmosphere were reported to be successful by both facilitators and (future) residents in all four settings. According to (future) residents, the creation of the right atmosphere created a space for community building and allowed (future) residents to get to know each other. This also influenced the content of the conversations. As one of the residents explained:

“For example, how will we live together, how to resolve conflicts? […] When you stroll on the beach together, you have your mind set on the horizon, you feel relaxed. Well, then you talk so easily with each other and you really get to know one another.”(Resident, Setting D)

“With something to drink and eat on the table, I have to say, you quickly get different conversations”.(Resident, Setting B)

In addition, according to both facilitators and residents, coming together regularly and the creation of the right atmosphere could contribute to the involvement of residents over a longer period of time. As the realisation of new housing initiatives could take several years, attention to this aspect while organising methods for participation was advised by respondents in all four settings. In some of the cases, extra activities were organised for people to get together in more informal and festive ways. Figure 3 shows an example of a mix of discussions in small groups and the use of creative elements, and the atmosphere this could create.

Figure 3.

Example of participation in the concepting and design phase. Courtesy of Vastgoed zorgsector, Utrecht.

Discussions in small groups, visiting reference sites, and the use of creative elements could contribute to the creation of the right atmosphere for participation according to both facilitators and (future) residents.

3.3. Transition to Living Together

In the transition to living together, there are a few elements that require attention: (1) ownership and exploring options and making decisions about living together should be considered, (2) the desired level of participation in this phase should be considered, and (3) participation should be considered an ongoing process.

3.3.1. Ownership and Exploring Options and Making Decisions about Living Together

For most of the residents that were interviewed, it was very important that they could decide themselves on how to shape their community or how they would want to live together. Among the topics that were important to them were the creation of rules for living together, the organisation of activities, possibilities to gather in groups within the building, decisions about the creation of a residents’ association (in the form of a legal entity) or committees, and the selection of new residents. Facilitators acknowledged the importance of decisions regarding this phase for residents:

“What comes after that [the concepting and design phase] is often much more complicated. Then you start living together. You start thinking about how you are going to do that and there are many small conflicts because people are people. There are always small troubles. It is about how you want to organise the community, for instance, where are you going to drink coffee together? All those small things that are very big things for those involved, that is what we often discuss.”(Facilitator, Setting A and B)

All of the facilitators stressed the importance of creating ownership for residents regarding this topic, wherein they feel responsible for the living community and are taking actions accordingly. As one facilitator explained:

“This sense of ownership is important. For everything that happens in and around the living community, they feel responsible together as a group. They take care of the community and building accordingly. That is beautiful to see. They act like this is our building.”(Facilitator, Setting D)

Some facilitators tried to facilitate this by looking out for talent within the group of residents and encouraging residents to use their talents within the community. For instance, if someone used to be a journalist, they would be asked to be involved in communication with other residents. Residents also reported that when there was a variety of residents in the group with different expertise and talents, varying from financial expertise to having a feeling for organising activities, who could and would act accordingly in the group, this was a success factor.

Some facilitators stressed that in this process, it is important to let residents know and feel that they have ownership themselves within the living community.

“Residents sometimes say to us: you should be doing this or that. However, our response to this question is: what are you going to do, how will you contribute to the community? To raise this awareness is very important. They will have to do it themselves, eventually.”(Facilitator, Setting A and B)

Facilitators and residents mentioned that it was important for residents to already start to explore the options and make decisions about living together themselves in the concepting and design phase. By doing so, residents had time to deepen the discussion on the topic of how to live together well in advance, and ownership could grow. Additionally, decisions made about this topic could influence the design of the building significantly, for example, regarding how the communal spaces might be designed. The residents of setting D in particular, who initiated the group themselves, had a strong sense of community and shared ownership. One of the facilitators of setting D noticed a significant difference in the degree of ownership among the group members compared to other groups, for instance, in regard to the maintenance of the building and taking the initiative. According to one of the residents, the group was committed to the process of participation. Being actively involved right from the start enhanced the ownership they felt both individually and collectively.

3.3.2. Desired Level of Participation

Whereas most facilitators facilitated the participation process during the earlier phases, once the housing initiative had been established, the same facilitators mostly handed over control to the residents themselves. They found this to be an important step in transferring control. However, the desired level of participation in the phase of living together is something that was not decided together with residents in most of the housing initiatives studied.

Although residents liked to have ownership in decision making regarding how to live together, at the same time, not all of them liked to be given full control and power to decide everything themselves in the transition to living together. Because there were so many different voices and opinions that could all collide with one another, there was the occasional need for an external voice to decide. As the quotation below shows, having an outsider as a referee offers the benefit of being more objective on the one hand, and not influencing the relationships in the living group on the other. As a resident explained:

“Now that the organisation is less actively involved, it [a discussion] becomes really personal more quickly. Deciding everything for ourselves now is at the same time disadvantageous because at the end of the day we have to live together as well.”(Resident, Setting A)

So, residents might sometimes prefer a different level of participation than the level that facilitators often think is desirable during the phase of living together.

On an individual level, not all residents desired the same level of participation for themselves. Some people liked to be more involved than others. Sometimes, the level of influence also differed between topics; for instance, an individual might have liked to have full control in the selection of new residents but not in other topics. Additionally, sometimes, people liked to have influence but through less direct or in less active ways. As one of the students living in the intergeneration living community showed:

“We wanted to change the front yard. One of the eighty-year-olds, who did not want to be an active member of the workgroup that was responsible, said ‘but you [the members of the workgroup] don’t have a wheeled walker and that information has to be included too’. Then I thought, you have a point. And I said, you know what we will do, every time we have new ideas, we’ll present them to you first and ask your opinions. And they liked this solution.”(Resident, Setting A)

In this example, one of the oldest members of the group, seemingly less involved in the participation process, wanted to make sure the things that were important to her were represented in the decisions that were being made, and they found a way of doing so within the group.

In the intergenerational living community (Setting A), some of the residents linked the participation in less active ways to the actual age of the participants. According to these residents, the oldest people in the group did not feel the need to participate in more active decision-making processes at given times. However, there were many people of older age involved in active ways within the various other settings, both with and without physical impairments.

3.3.3. Considering Participation as an Ongoing Process

In the case of established housing initiatives, we found that the participation of residents can be seen as an ongoing process. When designing housing initiatives, situations during the design might differ from the situation in the future.

First of all, new residents come to live in the living groups as former residents move out or pass away. Decisions that are made during the design and concepting phase are not automatically supported by, or applicable to, all newcomers. This problem is partially caused by the lack of a collective memory. In one of the already established cases, for example, newcomers seem to have different needs than residents who were involved in the concepting and design phase when it comes to being a close community. As one resident explained:

“During those gatherings in an earlier phase we were really on the same page. That was a nice period. But those gatherings were attended by the people who were planning to live here back then. In this village however, people move quite often. Now there are many new people living here. So, what was created then, is not always applicable anymore.”(Resident, Setting A)

The location of the initiative can also be of influence in the level of continuity. For example, residents in setting A explain that within their local community people often relocate to other neighbourhoods or cities. Conversely, in setting C, the initiator emphasized the importance for people to grow old in their own neighbourhood and community.

In addition to this, as residents age, new situations emerge. According to residents in the focus groups, the change in situation over time and as future generations become involved, might call for flexibility in the established social structures. Residents highlighted the importance of involvement of younger residents for the continuity of active forms of engagement and activities within the group. When selecting new residents, this is something they found relevant.

Flexibility in the architectural structures is also needed according to some residents. For example, there may need to be flexibility in the possibility to combine two small, separate housing units to form one larger unit. This may also require practical adjustments and a flexible attitude of the owner of the building.

“So, when you move here, you move into an existing frame, both architectural and social. Apartments are 30 square metres, for example. But future generations who come to live here, and I myself already have this need actually, might have different wishes. It should be flexible in a sense, that residents would be able to say this is too small for my liking, why not combine two apartments. Structures, both architectural but also social structures, should be prepared for changes like this and be flexible in this sense.”(Resident, Setting A)

In the case of housing initiatives A and B, the organisation is aware of the change in situation over time. They are in the process of introducing a yearly evaluation with residents in established housing initiatives. The changes in situations and dynamics over time show that meaningful participation is a process of continuous participation and collaboration.

3.4. Preconditions for Facilitating Participation

Regarding the different phases in the development of new housing initiatives, the lessons learned were discussed. During the different phases, two preconditions for meaningful participation were identified, which require attention in all the phases: (1) trust and communication and (2) having an open attitude during the process.

3.4.1. Trust and Communication

Facilitators are aware that trust and good communication, including the provision of regular feedback, are important for the overall process of participation. The question of how to establish this during the entire process, however, is a challenge that many facilitators face, and can differ in various contexts.

In the setting with older people of Moroccan descent, the facilitator stressed the importance of building personal trust through informal and personal contact and getting to know people and their networks.

“What you see quite often in larger organisations, is that they sometimes try really hard to include people with a migration background. But what often happens, they treat everyone the same [in a stereotypical manner]. Like ‘we have this ethnic place’, with carpets on the wall, and then they expect people to come. But this is not how it works. You have to build trust. You have to get to know people and their networks.”(Facilitator, Setting C)

In the experience of residents, visibility and informal or personal contact was important for the experience of good communication and the building of trust.

“I think it would really make a difference if they would be at our location. Now [name of the social housing association] is just a name. When the organisation would be an actual person, you could ask questions, get answers and discuss things together. Before, everything was very personal, and now it is just a name. And if we don’t like something, we all get angry at the organisation. But when they were here, at our location, it was a person with a name.”(Resident, Setting A)

“I have sent them quite a sharp e-mail. It was not that there was bad communication, there wasn’t even communication! They do not respond to e-mails, yes ‘we are working on it’. Now there is a new employee [contact of the social housing association]. And he contacted me right away. He came to visit me, at our location. The thing was, he took the initiative to come and visit, and took the time to have a look himself. It was fantastic. And when he could not change the situation, it was fine you know, he explains it to us.”(Resident, Setting B)

According to both facilitators and residents, the provision of regular feedback about what is being done with the input of those involved is important. In cases A and B, they make sure to meet regularly during the concepting and design phase, every eight weeks, and they provide and ask for feedback regarding the process. However, residents mentioned that they do not always know what is being done with their input. The provision of feedback in different ways, at different moments, and through different media might help.

“In my experience you have to repeat things. And I still have moments that I think, didn’t I already say this three times? And then still residents ask me three times why they never heard this before. That is a recurring issue. Or maybe, you should visualise things more. We are used to working with texts, but now we try to work more with pictures. This works better, and the use of big letters.”(Facilitator, Setting A and B)

When communication and trust are lacking, this can have major consequences for the participation process. In setting B, informal walk-in meetings were organised, a method evaluated as valuable by residents and facilitators. However, a resident reported that they did not want to attend these meetings at that phase, because they lost faith that input would be taken seriously due to a lack of a response earlier in the process.

3.4.2. Keeping an Open Attitude towards Residents’ Ideas and Preferences

Facilitators stressed the importance of keeping an open attitude during the process and to not hold on to one’s own preconceived ideas.

“You don’t know what will be the end result in the beginning. Even do not try to secretly think about the direction you want the project to go beforehand. You have to be brave enough to let your own ideas go. It is not about us as an organisation. Often organisations say it is about the customer. But I would like to say, ok, if that is so, make it happen! And you will see, it will always work out!”(Facilitator, Setting A and B)

“We always have to battle for this within the organisation: “Don’t yet go to the drawing board [to draft a design]!” I do understand that you make calculations to check for feasibility in advance. But in construction, we are used to going directly to the drawing board, [go to] developers, and when designs are done, we still have to start [with the participation of residents]. But the drawings are basically done. A part of the organisation is used to this way of working. Then we have to say: ‘No this is not going to happen!’ Making calculations is fine, as you need to know what your boundary conditions are. But please be careful not to fill in plans!”(Facilitator, Setting A and B)

According to facilitators, this can lead to surprising and innovative results, tailored by and for residents themselves. In one of the cases (B), this led to the placement of a local library in the centre of the building. Another example of this can be seen in case A, where students are living together with older people in an intergenerational setting.

However, according to the facilitators, having an open and flexible attitude, does not mean that the ideas of residents always have to be followed. Gaining knowledge about the question behind the question (i.e., probing) is considered relevant. For example, if people ask for four rooms, it is important to find out why. In this case, people wanted an extra room for their children to be able to stay. This could also be arranged by creating an extra communal sleeping room for guests in the living group, or, as the following example shows:

“We had this situation where people wanted a swimming pool. OK, that’s fine, but it’s not going to happen. Yes, the construction of a swimming pool is possible, but running a swimming pool… that can’t be done. Then we asked “but why do you want a swimming pool?”. And then you learn: they want to go swimming. You might want to go swimming, but that does not mean you actually want a swimming pool in your house. Then you have to think: ok, so how can people find their way to a swimming pool? Otherwise, before you know it, you are the proud owner of a swimming pool.”(Facilitator, Setting A and B)

According to residents and facilitators, aiming for an open attitude does not mean this is always achieved. Sometimes, facilitators who find openness to be important do make decisions based on their own assumptions or organisational conveniences that may be in conflict with the wishes of some residents. For example, one organisation made the decision to not hire an architect for the garden, which was suggested by the residents, as it was more convenient for the organisation to work with the same architect that was hired an earlier phase. Additionally, they did decide to place small stairs due to technical considerations and to enable residents to exercise, while residents spoke out against placing the stairs. These situations are still being discussed by residents after several years of living in the community; therefore, it is clear that the residents perceive them as major decisions.

In order to facilitate participation processes and to create a space to maintain an open attitude within the structures of organisations and rules and regulations, a structured approach might be needed. In cases A and B, the participation process is structured and embedded within the organisation, which is a success factor according to facilitators. Within this social housing association, a separate team of employees is responsible for the transformation and participation process. Their facilitators work in duos on a transformation project. According to the facilitators, this is needed, as the process can be very demanding.

During an earlier phase, facilitators were temporarily placed outside the organisation and only had accountability towards the director. This, according to them, provided space to be open towards ideas from residents themselves that perhaps did not adhere to the regular procedures or ideas from within the organisation.

“You have to be able to walk off the beaten tracks.”(Facilitator, Setting A)

“When you have to bring about change, you have to be more disconnected from structures otherwise there is a risk of being sucked back in by those same structures.”(Facilitator, Setting A and B)

When residents came with the idea of an intergenerational living community, the importance of being placed outside the fixed structures became clear. As one of the facilitators explained:

“Don’t underestimate the reaction we received when residents posed the idea of students living in the building. The alarm bells were ringing. [Some colleagues said:] ‘What are you going to do? Renting apartments to students? We are a housing association for older people, we don’t have the experience, that is not even allowed.’ But we were able to back-up this initiative that came from residents themselves, because the estate was ours, it was our responsibility. The team made a plan and this was presented to the director. But we could not be summoned back by the organisation.”(Facilitator, Setting A and B)

Now, after several successful transformation projects, a shift in organisational culture has taken place. Facilitators are more included in the organisation again, which enables change to be brought about in the whole organisation, and these changes are now enacted faster.

The abovementioned preconditions show that although each of the three phases has its own challenges, there are also more general factors that should be taken into account during the entire process of participation.

4. Discussion

This study explored how the participation of older people in the development of group housing was experienced by both facilitators and (future) residents and what lessons were learned about the facilitation of this meaningful participation within four settings in the Netherlands. In this section, the main findings of our study are discussed, and it is explained how these results relate to the existing literature. The discussion sets out with the three main insights regarding (1) the facilitation of participation in different phases of the process, (2) similarities and differences between the perspectives of facilitators and residents, and (3) the need for innovative approaches. Thereafter, some limitations of this study are discussed.

4.1. Lessons Learned about Facilitating Participation in Different Phases

The meaningful participation of (future) residents is a laudable pursuit for many of the facilitators. It is valuable to differentiate between the various phases in project development, as shown in Figure 2. Following on from this figure, an important lesson learned in all four settings is that from the beginning of a project, it was experienced as essential to involve all the relevant stakeholders and residents who are going to work together during the course of the project and/or who are foreseen to live together in the particular group home. In order to prevent problems in a later phase, the various parties involved have to get to know each other by discussing plans for, and perspectives of, the new situation and their own roles during the development phase. This process endorsed feelings of shared ‘ownership’ among the parties involved. In the concepting and design phase, meaningful participation encompasses having a say in the design of housing units and communal spaces, but also in how to live together within those spaces. Future residents have to prepare themselves for their own roles in the process of living together from an early phase, for example, regarding how to form a residents’ association or residents’ organisation. Successful methods for use in this phase included the following aspects: discussions in smaller groups, seeing examples of group housing, and the use of creative elements. In the phase of living together, it was seen in settings A, B, and D, how the role of facilitators and residents had to be discussed again in terms of everybody’s influence in decision making, responsibility, and support. As newcomers may have differing wishes and preferences to those residents who have been involved right from the beginning, and as conditions may change, meaningful participation is a continuous and ongoing process.

Participation can take place in different ways in the consecutive phases of the development process, as was also outlined before by Durrett [9], and this is why it is important to keep an eye on the widely used participation ladder (Figure 1) [42]. In designing the participation process, facilitators and residents do not have to choose a single level of participation. They can decide what their desired level of participation would be for each phase and for each context. The lessons learned as presented here should not be read as a fixed blueprint for use in every situation. In each setting participation should be seen as a situational and interactive process [44]. The lessons outlined in the current paper, however, may be of relevance for parties engaging in public participation trajectories to take into account.

4.2. Comparison of Perspectives of Residents and Facilitators

Although much of the existing literature focuses on methods of participation and how to address the needs of future residents [12,21], the joint perspectives of both residents and facilitators within particular case studies have not been studied in great detail in times of both convergence and divergence. The current study showed that residents and facilitators may have different expectations and experiences regarding participation as a process. Overall, residents wished to be more involved in processes that concerned the basics of the participation process itself. However, generally, facilitators did not consider this to be important. Different parties involved often have different notions about goals, tasks, and responsibilities during the participation process, which can lead to misunderstandings, disappointments, or even conflicts. Therefore, a shared vision should be created from the outset in order to improve levels of participation in an ethical way [55]. Issues that need to be addressed are the levels of influence that are desirable during certain phases in the process and the topics that can be participated in. In addition, stakeholders may have different ideas about the preferred level of participation, particularly in the final phase of living together. In terms of Arnstein’s participation ladder [42], facilitators often liked to experience a degree of ‘citizen control’ (rung eight) in this phase, whereas residents sometimes preferred ‘partnership’ (rung six). For instance, residents preferred a shared responsibility with the founding organisation when it came to mediation between residents. Machielse et al. [56] showed that even though residents are often responsible for the social living environment, an activating and facilitating professional may be needed for community building and to make the outcomes of this process last. This professional could support in activating residents or could mediate in situations of conflict. For social housing associations, this would mean they would have to facilitate professionals in terms of time and means [56]. As stated previously, having a shared vision about the roles and the goals of participation should be established together [55], and this is an ongoing process, as the results of the current study confirm.

Furthermore, the results of this study show that facilitators and residents often reported divergent experiences regarding two essential elements of successful collaboration, namely communication and trust. Facilitators were often aware of the importance of these elements and mentioned that they try to act accordingly. Residents, however, sometimes experienced a lack of communication and trust, which impacted the overall process of participation and their willingness to participate adversely.

Finally, decisions that facilitators may see as relatively small and insignificant may turn out to be very important for residents [57]. Even though most of the facilitators are aware of the importance of keeping an open attitude during the participation process, seemingly minor decisions based on pre-existing assumptions or organisational conveniences may be in conflict with the wishes expressed by some or all of the residents. The intention to, and knowledge about how to facilitate meaningful participation is not a guarantee for success [58].

4.3. The Need for Innovative Approaches in the Domain of Housing for Older People

The results of this study show how innovative approaches can contribute to the creation of meaningful participation. In participation, there is often a limited number of people who actively participate, and they are not by definition representative of the larger group that wish to participate in a project [21,59]. Participation projects are often designed in a way that requires certain skills of participants, especially when entering the higher level of influence on the higher rungs of Arnstein’s participation ladder [42,60,61]. Methods often require participants to be able to articulate needs, to speak up in meetings, and read project plans or other formal documents, thus posing the risk of excluding certain groups and of mostly including highly educated, or even ‘professionalised’, participants [61,62].

In the context of older people, some people might be hindered in participating due to physical or mental limitations, or they might experience feelings of not wanting to complain while participating. However, this does not mean they do not have needs or ideas that they want to be taken seriously. Nor does it mean they cannot or do not want to participate in more active ways [21,63,64] or on the higher rungs of the participation ladder [42]. As the example of one of the older residents in the intergenerational living community (Setting A) showed, the older resident did not want to participate in the working group for designing the garden, but she did want to have influence in the final say and found a way to do so within the community. The limitations experienced by older people may require adapting the methods selected for participation. Furthermore, roles and routes through which older people can participate should be diversified, making room for different ways to participate and for flexibility during the project [65].

As can be seen in the results of this study, the employment of creative methods can be of value in the facilitation of meaningful participation, as it creates space for different people to be included. This is in line with research in the field of healthcare, technologies, and with developments in the field of sustainable urban development, where tools are being created and shared that show a creative approach [44,45,46,63,64,66,67]. As some residents in this study mentioned, they would not always have participated if there had only been formal meetings. This was sometimes linked by residents themselves to educational or professional backgrounds, Furthermore, creative elements, such as seeing examples of group housing seemed to be of particular importance in setting C because older people of Moroccan descent were not always familiar with the possibilities of group housing in the Netherlands or formal procedures of participation. A more inclusive approach in participation processes asks for adapting methods to the needs of people living in vulnerable circumstances [68]. In addition, creative methods can help people explore their wishes for the future, which can be challenging, as many people have difficulties thinking about events that may occur in later life, also in regard to ageing [69]. In addition, methods used are not neutral elements, and their effect lies in the specific context of a situation. Here, it is advised that methods of participation and the way they are used should be reflected on and realigned when needed [70].