Abstract

Since the early 2010s, sub-divided flats have been proliferating in Hong Kong—one of the world’s most compact and expensive cities to live in. The growth of informal housing in the city has long been attributed to the shortage of housing supply. Apart from developing new land for housing, one possible approach to deal with the land supply constraint is to speed up the redevelopment of old buildings in the city centre in order to maximise the land use potential. Yet, this approach brings about many socio-economic issues that drive up the transaction costs for its implementation. To get around the hurdles of urban redevelopment, a land management technique called land readjustment (LR) has been recommended, but its use has never been institutionalised in the city. Using declassified archival documents and maps, this article argues that LR was already implemented—albeit informally—in Hong Kong during the 1960s–70s within the Kowloon Walled City. With the historical experience of the City of Darkness, the aim of this article is to shed light on the in situ resettlement of original site residents—very much at the heart of land readjustment—as a means to bring down the transaction costs of deep urban redevelopment.

1. Introduction

Hong Kong has been one of the most unaffordable cities in terms of house prices for almost the past two decades [1]. Over the twenty-year period between 2002 and 2021, house rent in the private rental sector increased by 115% [2]. The housing crisis in the city has become one of the most pressing issues of urban governance, leading to some other social problems [3,4]. On several occasions, key officials of China’s central government expressed their concerns about Hong Kong’s housing issues [5,6]. The housing problem has been ascribed to the structural imbalance between the housing supply and demand in the city [7,8]. The housing supply has remained irresponsive to the increasing demand for many years [9]. In fact, the new housing supply-to-stock ratio has been very low—less than 2% from 2009 to 2017 [9]. Moreover, the limited land supply for housing contributes to the intensification of development density [10], which in turn contributes further to soaring prices and rentals of living spaces in the metropolis. Although demand-side measures (e.g., special stamp duty, buyer’s stamp duty, and tightening mortgage terms) have been introduced by the Hong Kong government to stabilise the property market, supply-side measures (such as increasing the production of affordable housing) are still critical to tackling the housing crisis.

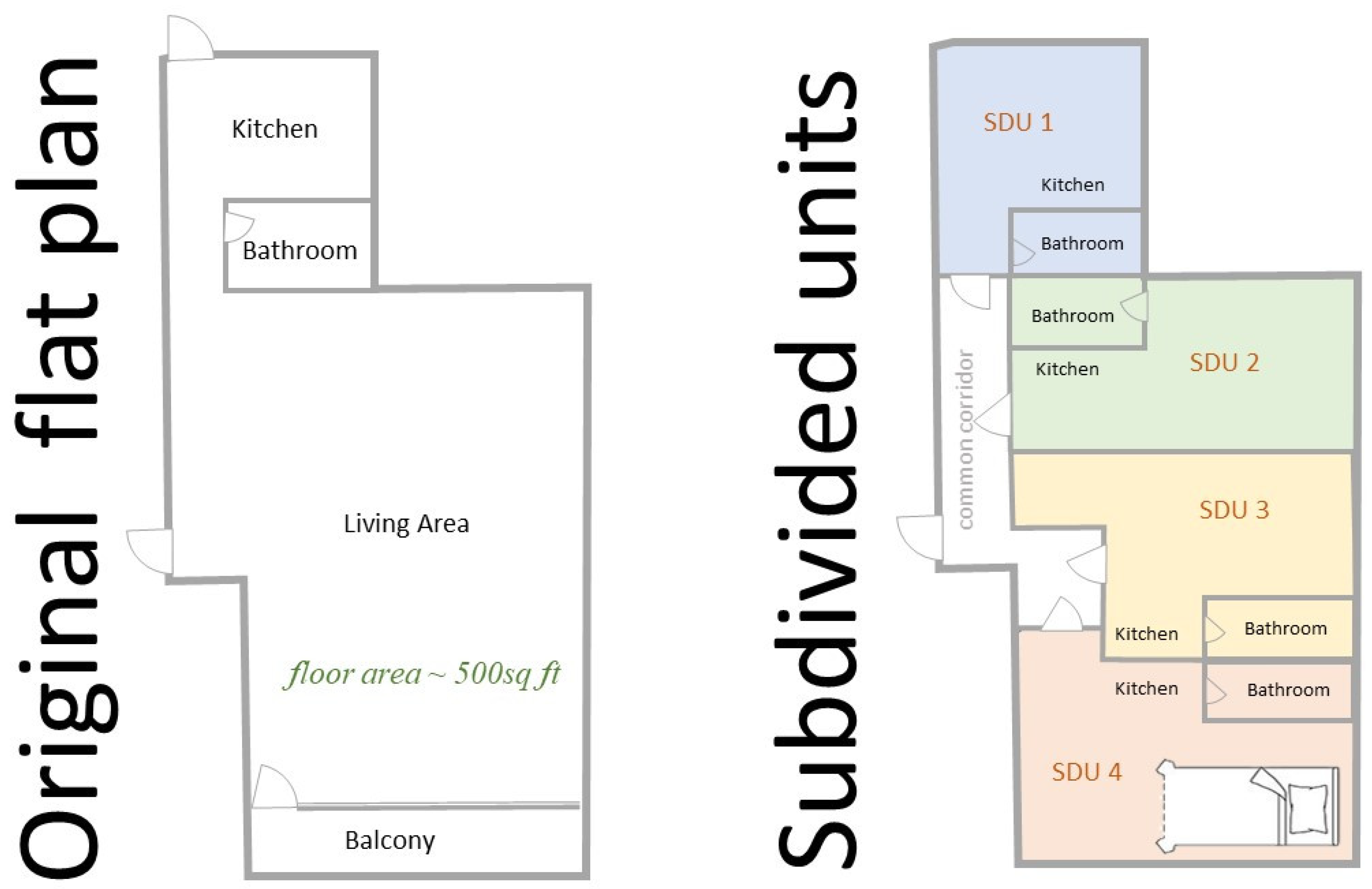

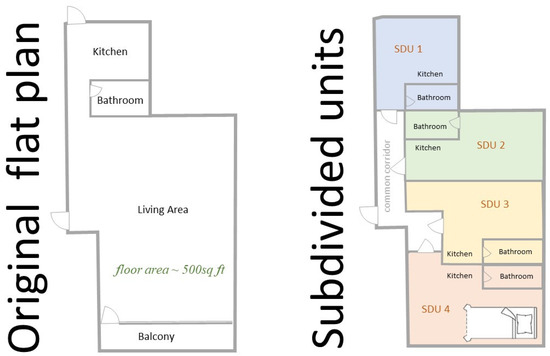

Nonetheless, the proliferation of the subdivided units (SDUs) since the early 2010s has demonstrated the increasing unaffordability of housing in the city [11,12]. SDUs generally refer to “individual living quarters having been subdivided into two or more smaller units for rental” [13] (p. 5). According to a reported survey [13], as early as 2013, 66,900 SDUs in the territory housed around 171,300 persons. Almost half of the respondents in the survey indicated high rental cost—second only to the proximity to work/study venues—as one of the main reasons for choosing to live in SDUs [13]. SDUs are notorious for their sub-human living and hygiene conditions. The majority of the units are within the range of 70 to 139 square feet (which is equivalent to about half the area of a parking space), but some were even smaller [13] (see Figure 1). In less than a decade, the number of SDUs jumped to around 101,000 in 2020 [14].

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram of an SDU in contrast to the original flat layout.

Having received from Beijing an ultimatum to remove the infamous subdivided flats by 2049, the Hong Kong government is trying different means to resettle residents from these “cage” houses to better housing conditions. Nevertheless, the crux of it all is primarily a lack of feasible land supply. In order to increase the land supply for housing development, options such as redeveloping brownfields, tapping private agricultural and recreational land, and near-shore reclamation, among others, have been explored and discussed within the community [15]. Historically, the government resorts to reclamation to avoid costly private property issues associated with land assembly [16], but this in itself brings along resistance from an environmental protection angle. Unlike cases abroad, where they are mostly vacant, brownfields in Hong Kong are still economically active, which may pose high transaction costs for the state to draw on [17].

Another option is to resort to maximising the under-utilised land resources in the city’s urban centres through redevelopment. Urban renewal in a high-density city such as Hong Kong is considered inevitable for sustainable urban redevelopment and land use [18]. However, urban renewal, as commonly practised in Hong Kong, is dominantly driven by economic factors [19], which also leads to conflicts among stakeholders, especially with the original residents [18]. The displacement of the original residents during redevelopment poses no small hindrance to a smooth and equitable outcome in such programmes. To facilitate the redevelopment (getting around the problems such as forced relocation or displacement), land readjustment (LR) offers some hope in rejuvenating the pockets of under-utilised urban buildings. In fact, LR was extensively studied during the last review of the urban renewal strategy in Hong Kong [20] but it was not incorporated in the updated strategy. Aside from the developer-led LR project—the redevelopment of the Lai Sing Building—completed in 2009 [21], LR seems to be not used in the high-density city of Hong Kong. Using declassified archival colonial documents and old maps, this article aims to demonstrate that the practice of LR has already been applied in Hong Kong much earlier, during the 1960s and 1970s, within the Kowloon Walled City (KWC). With its peculiar politico-historical background, the KWC became “one of history’s great anomalies” [22] —a den of illegal activities that neither the colonial nor the then-present mainland government could effectively control. Fascinatingly, this “anomalous” KWC had an informal real estate market at its peak in the 1960s and 1970s [23,24]. In fact, the developers were so entrepreneurial that in 1972, the KWC had around 259 buildings higher than three storeys (see the City District Office Report of 1972). Furthermore, the KWC had an informal registry for property transactions facilitated by the Kaifong Welfare Promotion Association acting as a witness [23].

The aim of this research was to find historical evidence that LR has already been implemented in Hong Kong and to recommend how it can be better applied, mutatis mutandis, to address the city’s current housing supply crisis. In this article, we intend to trace some mechanisms and elements of LR found in the KWC at that time as documented in the declassified colonial government reports. As many cases of LR are normally backed up by the formal government (see examples in the works of De Souza et al. and Pradhan [25,26]), this historical account provides a good example of one in a context where a formal government barely exists. Moreover, policy recommendations would be made on how LR may be more effectively employed in an extremely compact city such as Hong Kong. The rest of the article is organised as follows: The second section of this article provides an overview of LR as a land management technique. It is then followed by an elucidation of the KWC case. Then, we discuss the LR mechanism in terms of our three hypotheses. In the last section, the article is concluded with some recommendations drawn from the historical experience.

2. Land Readjustment: A Brief Overview

LR is a development tool wherein landowners turn over their land parcels in a transitory manner to a developer, local authority, or association in order to redevelop the parcels into a place with greater value or development potential. Among the benefits of this technique are to improve the quality of the site in a more equitable and economical way and, at the same time, recover the costs and share the gains from the increase in land value with the landowners [27]. LR has a long history. The literature records its use in Europe (e.g., Germany, Netherlands, and Turkey) in the late 19th century [28,29]. Some of the earlier examples of LR include Japan [30,31], Bangkok [32], Perth [33], Seoul [34,35], Kaoshiong [35], Malaysia [36], and other places.

In the old days, LR was mainly used for rural land consolidation or the rebuilding of post-disaster cities. Later on, its potential for developing old city-centre settlement areas was explored [37,38]. By preserving the social capital and ownership rights of the original inhabitants, LR may lessen social resistance to many inner-city urban renewals, especially among residents in old city centre districts [39]. Even in a recession, LR may be a useful tool in regenerating “hardcore” brownfields by promoting land assembly and increasing its value through infrastructure [40]. In a manner of speaking, it is one of the least interventionist among the value capture tools in land redevelopment [41].

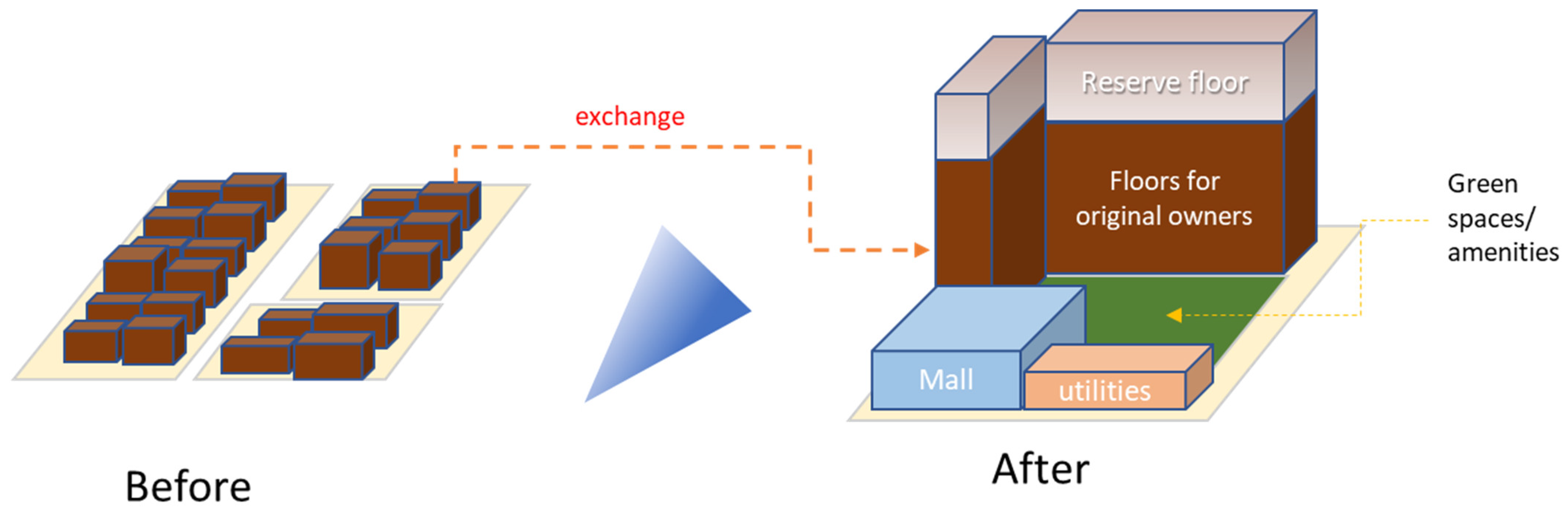

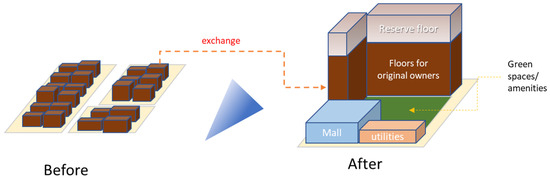

Figure 2 shows a schematic of an urban LR project before and after the readjustment. The original property owners pool their properties into a development scheme. After readjustment, some of the dedicated properties serve as a “reserve space” or “reserve floor”. The reserve floor or space will be sold to some other people so that the sale proceeds can be used for financing the redevelopment project (including costs incurred in the planning, administration, and construction) and the provision of communal green space, amenities, and utilities. Sometimes, the sale proceeds will also be used to cover the costs of the temporary rehousing of the affected owners/occupiers during the readjustment process. Some land may also be reserved for leasing purposes (such as building a shopping mall) so as to generate income for the long-term management and operation of the communal facilities. After deducting the properties dedicated for all these purposes, the remaining properties after redevelopment are redistributed to the contributing property owners in proportion to either the areas or the values of their original properties [42].

Figure 2.

Schematic of a hypothetical LR project in an urban setting.

Some LR projects are led and even decreed by the public authority [26,39]. In other cases, a non-profit urban planning firm can be commissioned to create the development plan for the LR project and/or administrate the project, such as what has been applied in the Indian city of Bhuj [43]. Private property owners may also initiate the LR [44]. In many cases, the private developers or builders may also be the ones initiating the LR, such as in the case in Mongolia [45] and in our case in Hong Kong, which will be shown later in this article. It is worth mentioning that LR does not always need formal land/property titles. For example, the proponents of a successful LR project in Huambo, Angola used the de facto land boundaries occupied by the informal settlers as the basis of their contribution to implementing the project [46].

However, not all LR projects are successful; there are also failure stories, such as one in Turkey due to disputes regarding the allocation calculation rules, a lack of competent technical personnel, and low-quality cadastral [47]. Aside from these, a low degree of landowner participation due to some political, social, and financing concerns also drives up the transaction costs for LR implementation [48]. Table 1 lists some possible advantages LR can contribute to urban redevelopment projects. They are categorised according to the criteria used for evaluating institutional process outcomes [49].

Table 1.

Some potential benefits of LR application in urban renewal.

In Hong Kong, one landmark LR project was the redevelopment of the Lai Sing Building in Tai Hang [21]. What differentiates this project from other redevelopment schemes was the low initial costs for the developer and the in situ reallocations of the original owners of the old building in the new development. In remunerating the original owners who participated in the LR project, the developer followed a flat-for-flat model, wherein a specific flat owner in the old building is given the same flat on the same floor of the new and taller building after redevelopment [21].

3. Materials and Methods

This study drew from a piece of archival research. Despite its obvious limitations, this method seemed to be the most feasible for this study’s purpose. One significant reason is that the KWC has been demolished for almost thirty years now and is currently a public park. Moreover, the former residents of the KWC have been dispersed for the last three decades. Fortunately, the colonial government records on the site are still mostly intact, which made archival work the most direct way to obtain information about that time. Formerly confidential (but now open) government reports stored in the Hong Kong Public Records Office were employed as the main materials for the investigation. This office holds records dating back to as early as the mid-1800s. At the beginning of the search, the keywords “Kowloon Walled City” and “Kowloon City” were used. One of the dossiers found is entitled “Development of Buildings: Kowloon Walled City (HKRS 396-1-4).” It includes, among other documents, exchanges of memos between the City District Office (Kowloon City) and the Secretary for Security regarding the buildings built or being built, which were deemed to exceed the Airport Height Clearance in 1973–1975. The dossier covers site reports and surveys conducted by the police officers in the vicinity. Another dossier entitled “Kowloon Walled City: Implementation of Ad Hoc Committee Reports (HKRS 163-9-233)” contains “a short study of multi-storey buildings in and around the Walled City”, dated 7 November 1972, describing the situation of these structures, and giving a historical overview of the said phenomenon. Although the archival information mentioned above was not originally meant to be exactly about LR, it fortunately fits our purpose. With proper adaptation, these non-tailor-made data are useful to make valid inferences to answer our research questions in a more feasible and less costly manner [50,51]. These reports are dated from the 1970s, which coincides with the time when the development of multi-storey buildings was on the rise. When studying LR, records on the redevelopment of the KWC are needed and providentially available in the records.

Furthermore, police investigation reports were also used to tabulate the changes in the number of building floors over some months in 1975. These figures give an appraisal of how active the real estate redevelopment was during the year. Lastly, old maps and aerial photos available from the Lands Department’s Survey and Mapping Office were also inspected to supplement the accounts described in the archives.

4. Case of the Kowloon Walled City

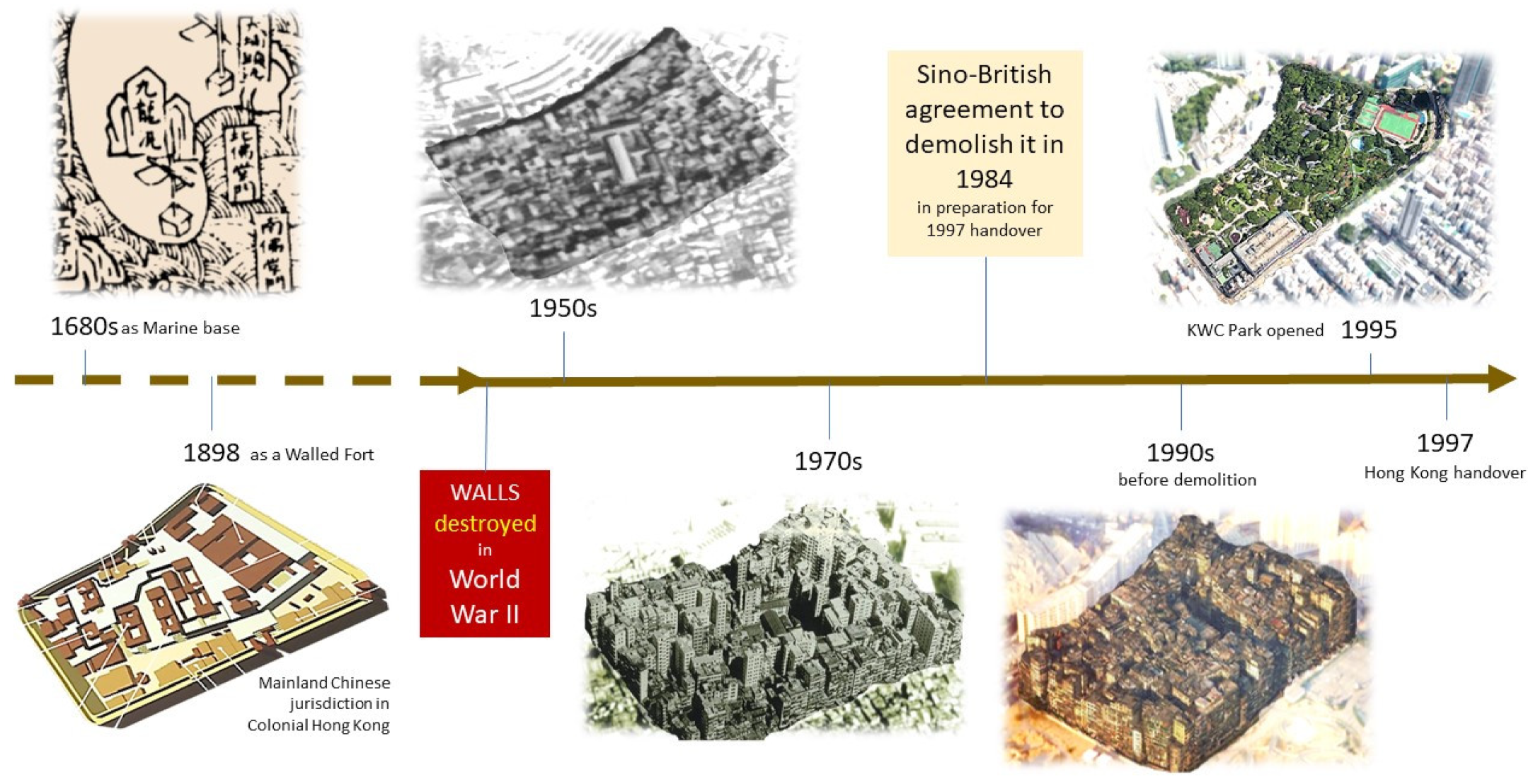

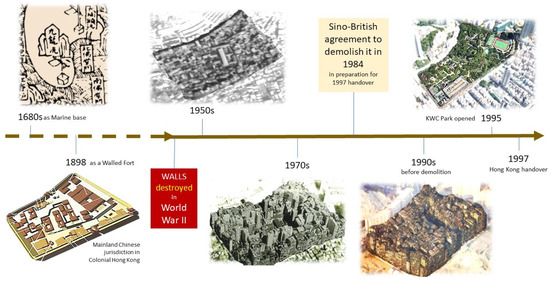

After the First Opium war, the place now known as the KWC was reinforced with walls as a Chinese fort in the Kowloon peninsula to protect the then-San On County from possible British incursion [52]. Presently, it is a Chinese Jiangnan-style garden park containing the old Yamen building and archaeological remnants of the fortress’ old south gate. When the colonial government leased the land now called the New Territories in 1898 in the Convention of Peking, the agreement contained a caveat that the land inside the fort (and the pier near it) is to remain under Chinese jurisdiction [22]. Being physically in the middle of the then British colony of Hong Kong gave the colonial government many political and juridical worries. After World War II, this was further aggravated by the increase in the population of the colony, including informal settlers inside the boundaries of the, by then, “wall-stripped” KWC. From this situation, the concrete block of multi-storey buildings arose “interstitially” [53], which is the focus of our study. Figure 3 is a simplified timeline of the history of the KWC.

Figure 3.

Simplified timeline of the KWC’s history.

Given its unique juridical status, the colonial government found it difficult to manage the KWC, but the Chinese government also did not play an active role in governing it [22,54]. Illegal activities from drugs to unregistered dentists filled the premises of the KWC [54]. The population of the KWC swelled, with around 33,000 living on a 2.6-hectare piece of land at some point [55].

As described above, those formerly confidential government reports used in this study are not strictly a study of the land redevelopment in the KWC but more about monitoring the building height limits, police intelligence, and pre-demolition studies. Interestingly, the reports show some glimpse of many redevelopment schemes amid the illegal—better still, “non-legal”—status of the built environment. In order to systematically determine if the KWC experienced some form of LR, we had to find the evidence to debunk the following null hypotheses below. These null hypotheses were formulated as such because refuting each of them determined the minimum requirement to establish the existence of LR in the situation of our case study.

Hypothesis 1.

There was no ownership rights system in KWC. This is fundamental because it is impossible to define a scheme as LR without any initial form of a functioning property rights system, no matter how rudimentary (e.g., the case of Angola [46]). Given the popular reputation of the KWC as a lawless place, many may easily assume that a form of ownership system was non-existent there.

Hypothesis 2.

Original landowners were evicted to other places. Essential to LR is some form or at least a choice of in situ rehousing for the original owners. Without this feature, it might be difficult to rule in the existence of LR. The KWC was viewed as a den of illegal activities, so it may not have been far from the popular perception that landowners were evicted by powerful triads.

Hypothesis 3.

There is no evidence of an increase in the value of the property after redevelopment. What drives the successful implementation of LR in many instances is the windfall after the redevelopment project. If no added value is observed in the case, the reason for the development may be far from the ideal LR we are expecting to find.

As a sub-null-hypothesis of Hypothesis 3, there was only one de facto developer monopolising the KWC, which rules out market-based LR. Market-based competition is relevant because it strengthens the evidence that there is incentive to acquire the added value foreseen in these redevelopments, and it may lessen the possibility of non-economic motivation for such behaviour. This also allowed us to draw some conclusions without the need to find out the internal state of the monopolistic syndicate if it was the case, which is far beyond what our archival research method could provide.

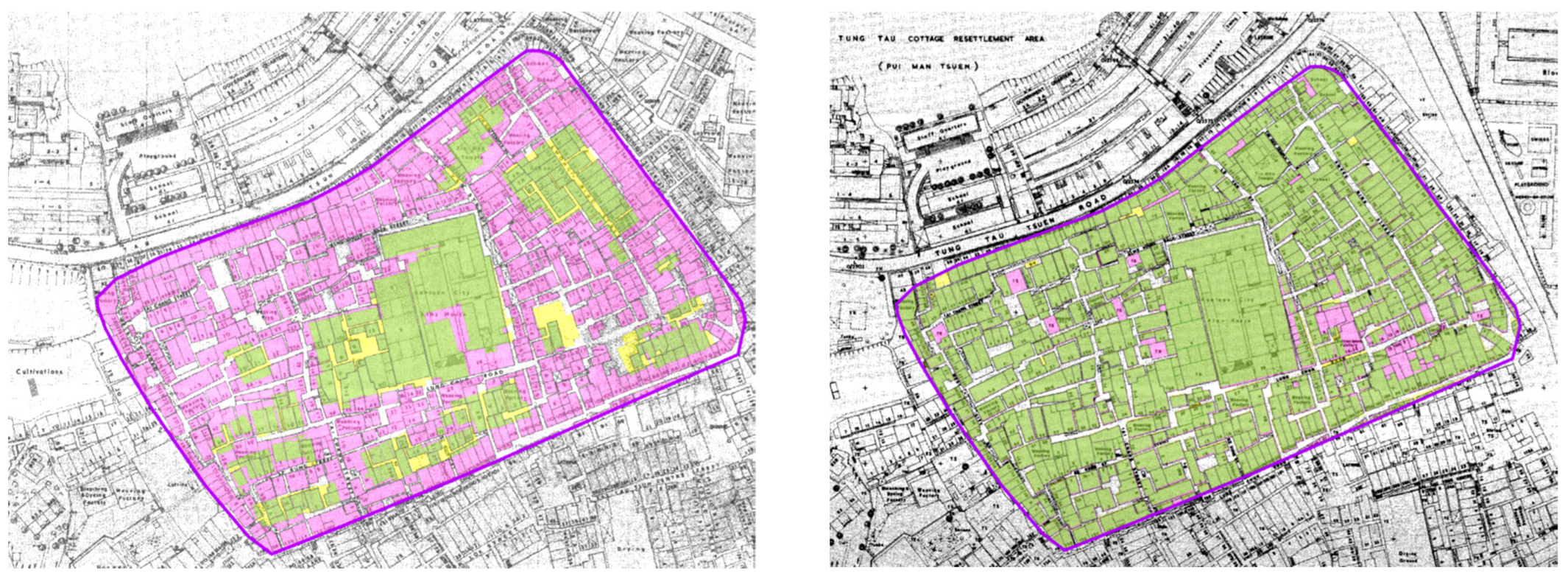

4.1. Stable Lot Boundaries

From its Walled Fort days between 1922 and 1961, the KWC’s built-up area changed substantially, while its footprint afterwards remained stable from 1961 to 1968 and beyond until the 1980s. Figure 4 illustrates such a change, inferring that the footprint of the lots amid the limited space has been stable enough for redevelopment transactions, which paved the way for the multi-storey buildings. The stable lot boundaries may have also facilitated the LR transactions between the landowners and the developers. In fact, a more detailed examination of the lots revealed that some were consolidated but more or less retained the shapes of the original lots.

Figure 4.

In pink, changes in property boundaries (footprint) between 1922–1961 (left) and 1961–80s (right) within KWC (adopted from the work of Lai et al. [23]).

Furthermore, Lai and others [23] conducted a study of the informal land registry system coordinated by the Kowloon Walled City Kaifong Welfare Promotion Association. This informal transaction system alludes to the existence of a proper—albeit informal and less secure—ownership rights system.

4.2. In Situ Rehousing

Essential to LR is the mechanism of the in situ rehousing of the original owners. In the same reports from the archive, it has been described how a site was assembled with a system of in situ housing for some original owners.

“4. There is not much eviden[ce] to suggest that the village-type house owners had been pressurised by “strong arm” tactics into v[a]cating their houses for redevelopment. Developers, it is known offer very favourable terms which fall along the following lines: the owner of the site is promised, in order to impart confidence upon others, is always given, the first 5 storeys of the new building should it extend to 10 storeys or more, proportionately less if it is lower. In the case of joint ownership, the 5 storeys are shared pro capita. Tenants are compensated by the payment of an amount equivalent to the total rent he would have had to pay in 5 years.”(Source: City District Office Royal Hong Kong Police report 1972 HKRS 163 9-233.)

In the above report, it is quite apparent that these arrangements seem similar to LR’s in situ rehousing mechanism. It is reasonable to infer that the allotment of the first 5 storeys to the original owners allowed the redevelopment to peacefully proceed with less resistance from the original owners. Although LR in general is not limited to a mere vertical redistribution of windfall shares, this approach has been a logical course of action for our case given the high density, small area, and social-political status of the KWC. The authors do not discount other possible redevelopment mechanisms, such as joint ventures between the site owner and the developer. Nevertheless, one may already begin to infer from this general account some traces of LR amid the supposedly “lawlessness” of the City of Darkness.

In 1975, police reports were kept on demolishing parts of the multi-storey buildings that exceeded the height limit stipulated by the prevailing Airport (Control of Obstructions) Ordinance. The following are some specific examples wherein it was mentioned there that the original owner was given some form of in situ rehousing after the redevelopment.

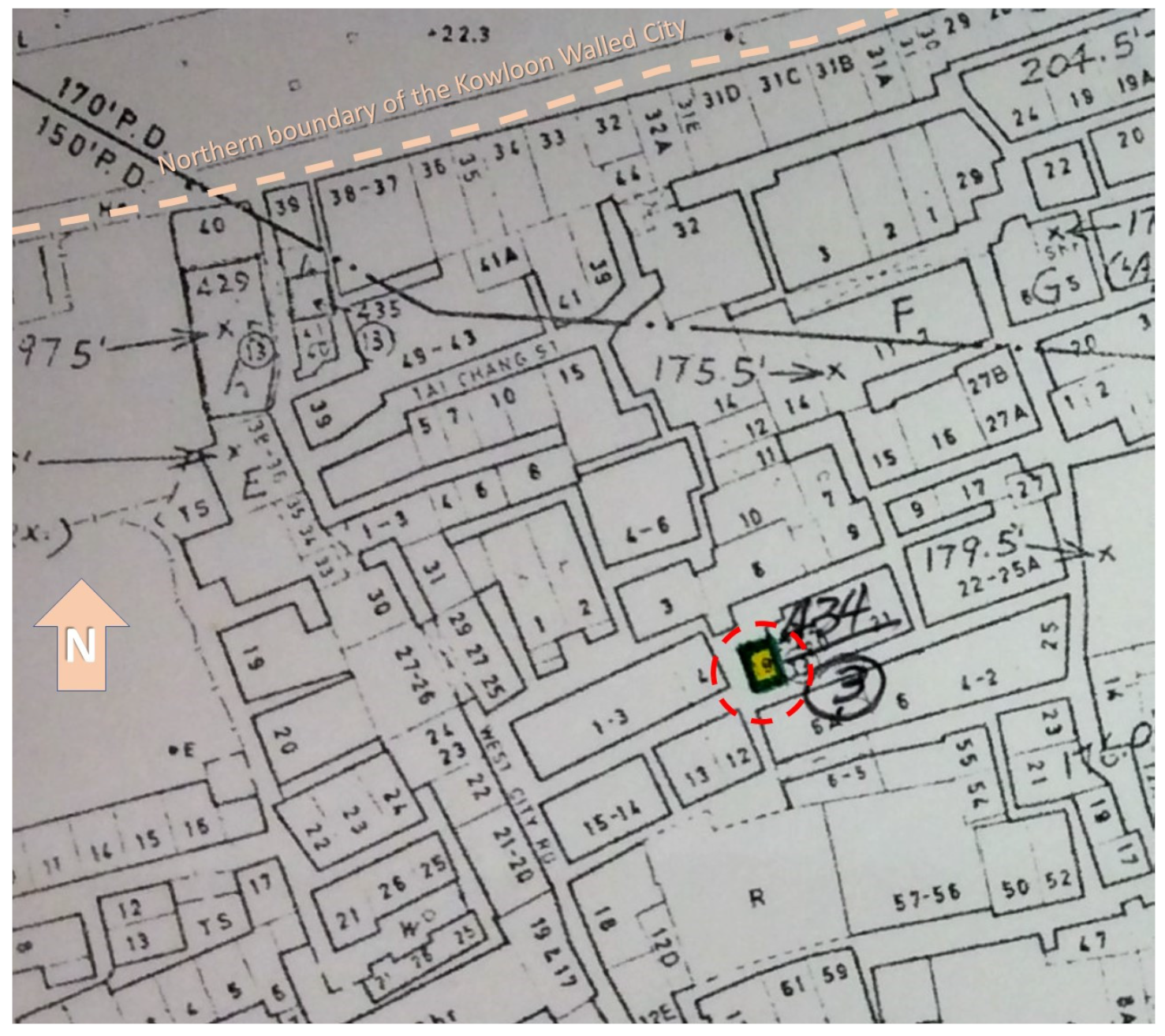

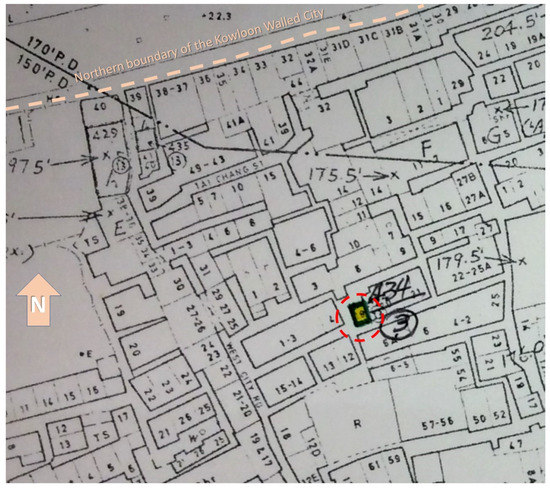

As shown in Figure 5, building No.19 on Shung Yee Lane is a building west of the old Yamen, right in the middle of the KWC. It allegedly exceeded the airport height limit by 11 feet 6 inches and its developers volunteered to reduce its height on their own. In the course of the account of the occupied units in the building, the police reported that “one of these is thought to be occupied by the original landowner who has been given a flat in return for the land.” (Source: 12 December 1975 report. Buildings in KWC (1975) HKRS 396-1-4 No. 179.)

Figure 5.

No.19 Shung Yee Lane (highlighted in the red broken-line circle) on a 1975 report map.

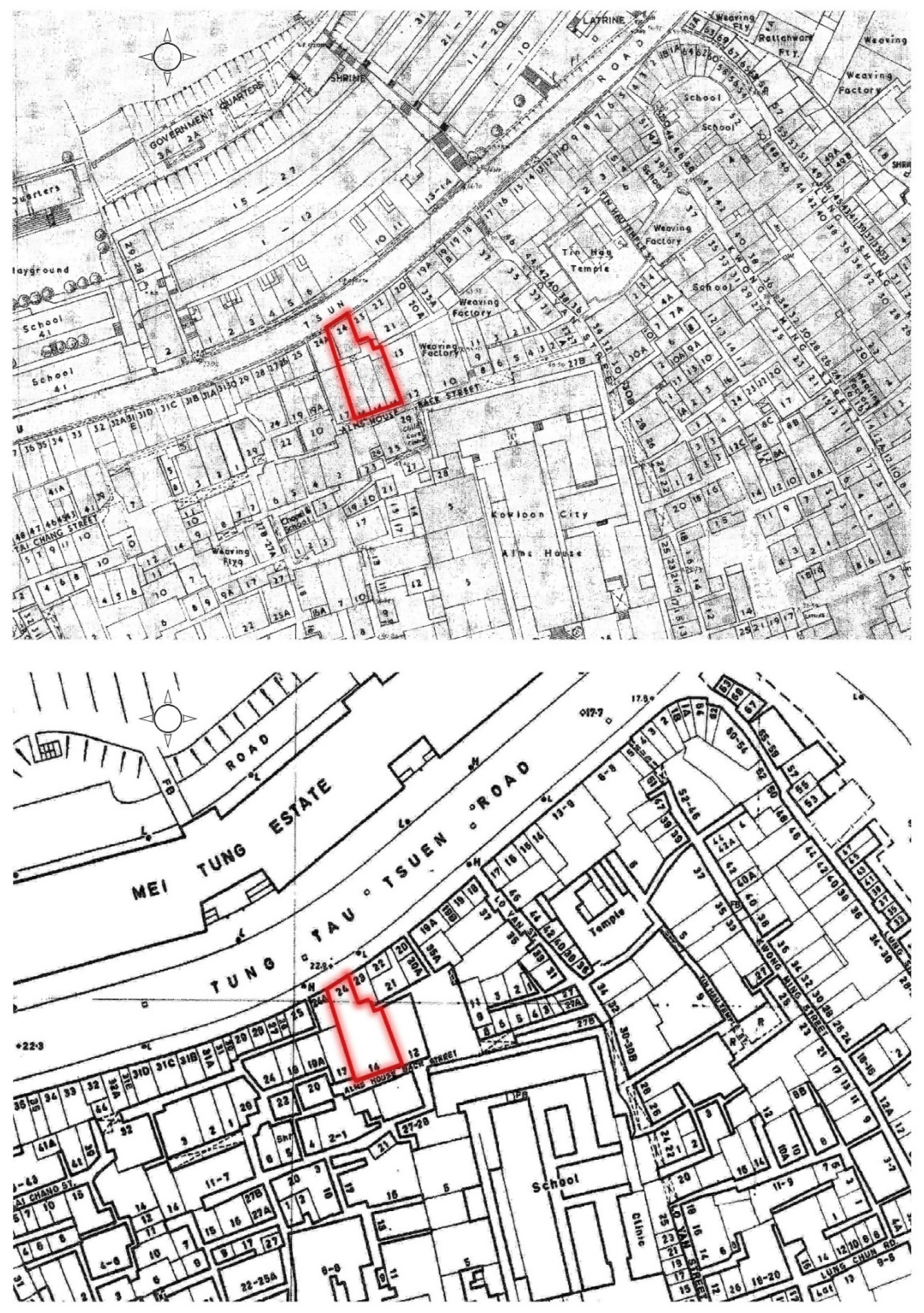

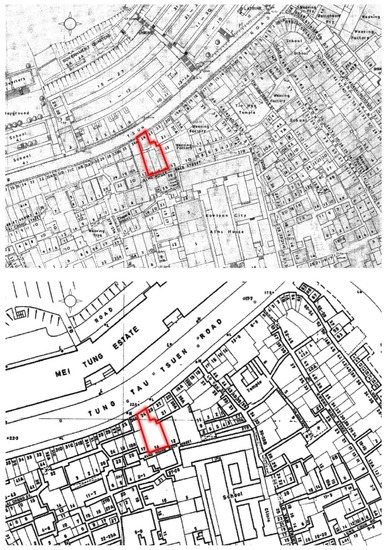

In another case in May 1975, the building in question was No. 24 Tau Tung Tsuen Road, located at the northern edge of the KWC, which makes it quite lucrative compared to the ones more central in the KWC. It can be seen in Figure 6 that the property was originally a smaller building in the 1960s and was later consolidated with lot No. 14 into a 3000-square-feet (approx.) site in January 1975. The report indicates that the original owner, Sun Kee Plastic Factory, received an amount of HKD 600,000 and was given the ground and first floors of the new building (Source: Buildings in KWC (1975) HKRS 396-1-4 No. 89). Apparently, the leaders of the 10-developer consortium were Chan Chun Kwong and Nga Sze Hing. Considering the whole project cost HKD 2 million and the land accounted for 30% of it, this apparent LR approach seemed to have lessened the initial capital expenditure of the project.

Figure 6.

Images of No. 24 Tau Tung Road in 1961 (above) and after the redevelopment in 1977 (below).

In 1973, there was another case in which a building was built in the so-called “sensitive zone”—an area immediately outside the perimeter of the original wall. Eventually, the building was demolished by the colonial government. Nevertheless, in spite of the demolition, the case was very well documented and had many interesting insights regarding the redevelopment practices at that time. The said 11-storey building was a consolidation of lot Nos. 57 and 59 along Tung Tsing Road (Source: Buildings in KWC (1975) HKRS 396-1-4, No. 1). Here, the original owners decided to consolidate their properties. Mr. Chan was the owner of the original two-storey building at No. 57, while Mr. Wong owned a single-storey building at No. 59. They compensated the two tenants at No. 57 and invited two other parties, Mr. Ngai (an architect and contractor) and another Mr. Wong (the financier), to participate in the redevelopment project. Their mutual agreement was that after the project completion, each party would have two floors, while the rest would be sold. (Source: Buildings in KWC (1975) HKRS 396-1-4, No. 43.)

An interesting repercussion of this project was the two tenants. One of them received HKD 16,000 as settlement, but he also made a down payment for one of the new flats. The other tenant was offered a flat in the new building. They had the contract of this agreement “stamp dutied”, that is, with a stamp duty of HKD 0.15 paid (Source: Buildings in KWC (1975) HKRS 396-1-4, No. 10).

4.3. Value Capture Incentive

The sharing of the increase in property value is normally an incentive for carrying out LR. For completing the picture of our inference, it may be beneficial to identify if this possible motive is at all likely by approximating the volume of redevelopment in the KWC. Fortunately for us, the Royal Hong Kong Police conducted a survey of the low-storey buildings that were being raised to multiple storeys in 1975 during the drama of the Airport Height restrictions. It can be seen in Table 2 below that a series of buildings had their heights increased. Assuming there was no monopolistic collusion among all the developers, it could be inferred that there was economic windfall in most projects, which encourages further redevelopment at such a scale. In 1975 alone, a total of 347 storeys or an average of eight storeys per building was attempted to be built in the KWC. Given that the prices of each flat (e.g., HKD 26,000 per unit) (Source: Buildings in KWC (1975) HKRS 396-1-4 No. 179) were around half of the prices in the other part of Kowloon, we may surmise that the amounts we can see were quite lucrative for the owners and developers inside the KWC. Eventually, some of these floors were torn down due to safety reasons, but the risk the developers took or were ready to take in order to have a share of the market can still be seen.

Table 2.

Summary of multi-storey buildings being raised in 1975 (Kowloon City District Office).

Furthermore, it was beneficial to find out that some form of competitive market environment was present, and the scenario was not an artificially controlled monopoly, so that we could validate the vibrant real estate development rush observed above. We then looked at the main players, who were the constructors/developers in the KWC back then. In the 1972 Royal Hong Kong Police Report on the multi-storey buildings in the Kowloon Walled City, ten developers or construction companies building up the 2.6-hectare KWC were identified. Table 3 lists these ten players.

Table 3.

List of developers identified from the Royal Hong Kong Police report in 1972 (City District Office 1972 HKRS 163 9-233).

The police investigation report said that they found no evidence of syndicate-type movement among the constructors, although there was a monopolistic advantage of the most significant four (City District Office 1972 HKRS 163 9-233). Furthermore, Lau and others [24] also identified more developers and their companies in an earlier study.

5. Discussion

The issue of multi-storey buildings and the airport height restriction in the KWC may have been a great headache for the colonial government at that time, but providential for later researchers, as this event provided the impetus to record detailed accounts, such as what can be seen above, that might well have been lost in time and remain as hearsay or urban legends.

Although no legal titles were assigned to the properties in the KWC, we noted the presence of an informal witnessing system facilitated by the neighbourhood association [23] and the relative stability of the building footprints in spite of the consolidation of some properties. This debunks our first null hypothesis about the absence of a minimum delineation of property rights, which overcomes a basic hurdle in establishing the historical LR in the KWC. Although seemingly very simplistic, this point is very relevant because a minimum delineation of property rights was necessary for these transactions—whether formal or informal—to take place [56].

In three separate instances, we found documented evidence that in some buildings, the original owners ended up being able to stay in the original site after the redevelopment. One of the documents, in fact, is a more general report about this phenomenon in the KWC by the Hong Kong Royal Police. This debunks our second null hypothesis. Despite not being able to conclude that it happened in all the cases, these findings allow us to conclude that at least a choice for the in situ rehousing of the original owners was present in the KWC’s redevelopments, which is essential to LR.

Thirdly, what drives LR in many instances is the windfall after a redevelopment project. If no added value is observed in the case, the reason for the development may be far from the ideal LR expected. In fact, we found documented evidence of robust market-driven real estate redevelopment in 1975. It was also found that there were a number of developers and there seemed to be no syndicate-like behaviour for most of them. Therefore, the third null hypothesis and its sub-null hypothesis are rejected.

The presence of LR elements in the informal setting of the KWC highlights an enigma of its absence in present-day Hong Kong. It may be due to the length of time (6–7 years) it takes for urban renewal projects to rehouse original residents in situ that many find it “unrealistic for owners to participate in it as they will have to pay for rented accommodation throughout the project construction period.” [57]. Whatever the reason, it appears that the “software” is feasible as seen from the KWC’s experience, but the legal framework to fit it in the city’s current situation is not yet ready. For instance, owner “demand-led” urban renewal projects, which are the closest we have to LR, do not readily enable in situ rehousing for affected owners. However, these types of projects may have the potential for LR if some legal framework is put in place. These adjustments in legislation may serve “to delimit threat positions (hence reducing contractual risks [between the original owners and the developers/government] that would otherwise deter exchange)” [58].

It also begs the question of why we need formal institutions if private contractual arrangements worked for LR in the KWC. Understandably, there are advantages to an informal property rights system in some cases [59,60,61] that a formal system may find more difficult to face. The special juridical situation of the KWC back then may have been more conducive for some long-term relational transactions rather than a more formal transaction involving an independent third party [61]. Nevertheless, looking back to the most classic example of private planning in Houston [62], the “primeval foundation” (land/property boundary delineation) provided by formal institutions was still necessary to allow for these private contractual arrangements to materialise [63]. In fact, the KWC depended on these “primeval” foundational institutions despite their pseudo-formal nature, in the form of the Kai Fong Association services and the formal court system outside the KWC premises.

Another reason is that the scale of the KWC was much smaller than the whole of Hong Kong, not to mention the skyrocketing real estate property prices now compared to then. Informal property rights systems become less advantageous as scarcity and value of land resources increase [64]. The number of owners involved in the redevelopment of an old tenement block today may even be higher than that in the KWC’s case. The transaction costs incurred in the initiation and implementation of the LR project would be higher. Included in this may be the degrading credibility of the developers in Hong Kong, perceived as “real estate hegemony” [65,66], which makes people less confident to rely solely on private contracts. They want institutions that are “more formal” to increase their certainty and protect their rights. Therefore, we may need some alternative institutional arrangements for lowering the transaction costs.

6. Conclusions and Policy Implications

The case study presented in this article suggests that private sector-led LR was practised in Hong Kong well before the Lai Sing Building project. It demonstrates that the LR technique is promising even in redeveloping properties without clear or formal property rights. Outside of Hong Kong, Cain and others [46] also reported something similar in Angola, wherein unclear land boundaries were used as a contribution basis for LR. In light of the historical lessons from the case study, below are some possible policy implications that may address the problems presented at the start of this article.

LR seems to show potential in increasing land for housing through the redevelopment of old building stock and hopefully easing the housing burden of the poor, such as those living in the SDUs. Nevertheless, in order to facilitate LR in the private sector in a more structured market such as present-day Hong Kong—where the dynamics are a bit different compared to the KWC in the 1960s–80s—some institutions may need to be emplaced.

One possible difficulty to implement LR in Hong Kong is the perceived general mistrust of developers [65,66,67]. Given the juridical circumstance of the KWC case, it is not unreasonable to assume that there also existed mistrust towards some developers back then. Nevertheless, as an unintentional safeguard for current tenants, developers or “owners” avoid forced evictions because they shun the bad publicity that this can cause for their future prospective buyers (City District Office Royal Hong Kong Police report 1972 HKRS 163 9-233). Another work also noted that no violence was recorded during land assemblies [23]. This reputation factor was similarly found in some informal land systems in mainland China [61] and the lower prices in the KWC seem to have augmented these uncertainties posed by a lack of formal authority back then. In the case of modern Hong Kong, the circumstances are different in some ways. The high value of property and the extent of the territory have increased the demand for certain formal institutions to support processes previously informally done [64]. The government may need to step in by putting some risk abatement measures or guarantees in place. For instance, some legal penalties may be needed to lessen, if not avoid, the incompletion of redevelopment projects.

Another possible support is a set of clear valuation standards for valuing the inputs and outputs of the readjustment process. One of the most significant reasons why LR is annulled in court is the disagreements over distribution allocation [47]. This was somehow lessened in the fuzzy juridical and informal situation in the KWC. In some cases, informal systems may provide lower transaction costs in handling a land dispute than formal ones [60], which may have been the case in the KWC in the 1970s. In the present-day scenario of the city, the cost of internalising these externalities may make it more sensible to formulate certain new institutions [68]. Without needing to go through the time-consuming and high-cost court hearings, a venue for arbitration for these sensitive bargaining discussions may well be most welcomed support from the state. For instance, a government-backed body may be set up that specialises in these redevelopment issues.

Understandably, the forensic archival research done here has limitations and gaps that can further be augmented by future research work. For instance, a more thorough, albeit tedious, three-dimensional computer reconstruction of the City of Darkness as the individual lots and buildings evolved from the 1960s to the 1980s may elucidate other archaic land use phenomena useful for today’s urban issues. In more modern times, it may also be worthwhile to research and survey small scale LR-like in situ rehousing strategies incorporated in different projects all over Hong Kong and other cities. In turn, these case studies may help elucidate how to effectively apply them on a broader scale.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.H.C. and Y.Y.; methodology, M.H.C.; validation, Y.Y.; formal analysis, Y.Y.; investigation, M.H.C.; resources, M.H.C.; data curation, M.H.C.; writing—original draft preparation, M.H.C.; writing—review and editing, Y.Y.; visualization, M.H.C.; supervision, Y.Y.; project administration, M.H.C.; funding acquisition Y.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The article processing charge of this article was funded by the Research Seed Fund of Lingnan University (Grant No.: 102393).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analysed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article. If readers would like to see the archival documents, please consult the General Correspondence Files (Confidential) in the Public Records Office: File No. HKRS163/9-233 and HKRS396/1-4.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge Lawrence W.C. Lai of the University of Hong Kong for the archival materials used in this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Cox, W. Demographia International Housing Affordability—2022 Edition; Urban Reform Institute: Houston, TX, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Private Domestic—Price Indices by Class (Territory-Wide) (from 1979). Available online: https://www.rvd.gov.hk/doc/en/statistics/his_data_4.xls (accessed on 13 April 2022).

- Forrest, R.; Xian, S. Accommodating discontent: Youth, conflict and the housing question in Hong Kong. Hous. Stud. 2018, 33, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dieter, H. Inequality and social problems in Hong Kong: The reasons for the broad support of the unrest. Aust. J. Int. Aff. 2020, 74, 341–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong Kong Property Giants Deny Beijing is Ramping Up Pressure on Industry to Fix City’s Housing Woes, Following Reports of Officials Losing Patience. Available online: https://www.scmp.com/news/hong-kong/hong-kong-economy/article/3149984/hong-kong-property-giants-deny-beijing-ramping (accessed on 13 April 2022).

- What’s Stopping Hong Kong from Fixing Its Housing Crisis? Available online: https://www.thinkchina.sg/whats-stopping-hong-kong-fixing-its-housing-crisis (accessed on 13 April 2022).

- International Monetary Fund. People’s Republic of China—Hong Kong Special Administrative Region; IMF Country Report No. 22/69; International Monetary Fund: Washington, DC, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Chong, T.T.L.; Li, X. The development of Hong Kong housing market: Past, present and future. Econ. Polit. Stud. 2020, 8, 21–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, C.K.Y.; Ng, J.C.Y.; Tang, E.C.H. What do we know about housing supply? The case of Hong Kong SAR. Econ. Polit. Stud. 2020, 8, 6–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, R.; Wheaton, W.C. Effects of restrictive land supply on housing in Hong Kong: An econometric analysis. J. Hous. Res. 1994, 5, 263–291. [Google Scholar]

- Yau, Y.; Lau, W.K. Big data approach as an institutional innovation to tackle Hong Kong’s illegal subdivided unit problem. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, K.M.; Yiu, C.Y.; Lai, K.K. Responsiveness of sub-divided unit tenants’ housing consumption to income: A study of Hong Kong informal housing. Hous. Stud. 2022, 37, 50–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Policy 21 Limited. Report on Survey on Subdivided Units in Hong Kong; Policy 21 Limited: Hong Kong, China, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Report of the Task Force for the Study on Tenancy Control of Subdivided Units (March 2021). Available online: https://www.legco.gov.hk/yr20-21/english/panels/hg/hg_th/papers/hg_th20210426cb1-820-1-e.pdf (accessed on 16 April 2022).

- Task Force on Land Supply. Striving for Multipronged Land Supply: Report of the Task Force on Land Supply; Task Force on Land Supply: Hong Kong, China, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Lai, L.W.C.; Lu, W.W.S.; Lorne, F.T. A catallactic framework of government land reclamation: The case of Hong Kong and Shenzhen. Habitat Int. 2014, 44, 62–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Legislative Council Brief: Government’s Response to Report of Task Force on Land Supply. Available online: https://www.devb.gov.hk/filemanager/en/content_1051/LegCo_Brief_TFLS_Report.pdf (accessed on 16 April 2022).

- Wang, H.; Zhang, X.; Skitmore, M. Implications for sustainable land use in high-density cities: Evidence from Hong Kong. Habitat Int. 2015, 50, 23–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, E.H.W.; Lee, G.K.L. Contribution of urban design to economic sustainability of urban renewal projects in Hong Kong. Sustain. Dev. 2008, 16, 353–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Study Report for the Urban Renewal Strategy Review: Urban Renewal Policies in Asian Cities. Available online: https://www.ursreview.gov.hk/eng/doc/Policy%20Study%20Report%20in%20Asian%20Cities%20050509.pdf (accessed on 16 April 2022).

- Li, L.H.; Li, X. Land readjustment: An innovative urban experiment in China. Urban Stud. 2007, 44, 81–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinn, E. Kowloon Walled City: Its origin and early history. J. Hong Kong Branch R. Asiat. Soc. 1987, 27, 30–45. [Google Scholar]

- Lai, L.W.C.; Lorne, F.T.; Chau, K.W.; Ching, K.S. Informal land registration under unclear property rights: Witnessing contracts, redevelopment, and conferring property rights. Land Use Policy 2016, 50, 229–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lau, P.L.K.; Lai, L.W.C.; Ho, D.C.W. Quality of life in a “high-rise lawless slum”: A study of the “Kowloon Walled City”. Land Use Policy 2018, 76, 157–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Souza, F.F.; Ochi, T.; Hosono, A. Land Readjustment: Solving Urban Problems through Innovative Approach; Japan International Corporation Agency Research Institute: Tokyo, Japan, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Pradhan, T. Land Readjustment in Kathmandu: The Naya Bazar Project; Civil Engineer Urban Development Department: Kathmandu Metropolitan City, Nepal, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Archer, R. The possible use of urban land pooling/readjustment for the planned development of Bangkok. Third World Plan. Rev. 1987, 9, 235–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mittal, J. Extending land readjustment schemes to regional scale: A case study of regional ring road via Mosaicking neighborhood level. Real Estate Financ. 2013, 30, 62–73. [Google Scholar]

- Turk, S.S. Land readjustment: An examination of its application in Turkey. Cities 2005, 22, 29–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hewes, L.I. On the current readjustment of land tenure in Japan. Land Econ. 1949, 25, 246–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, R. Notes on the earthquake and reconstruction in Japan. Bull. Seismol. Soc. Am. 1925, 15, 100–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Archer, R.W. The use of the land-pooling/ readjustment technique to improve land development in Bangkok. Habitat Int. 1986, 10, 155–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Archer, R.W. Land pooling for planned urban development in Perth, Western Australia. Reg. Stud. 1978, 12, 397–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.H. Changes in urban planning policies and urban morphologies in Seoul, 1960s to 2000s. Archit. Res. 2013, 15, 133–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Schnidman, F. Land readjustment. Urban Land 1988, 2, 2–6. [Google Scholar]

- Agrawal, P. Urban land consolidation: A review of policy and procedures in Indonesia and other Asian countries. GeoJournal 1999, 49, 311–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsson, G. Land readjustment: A tool for urban development. Habitat Int. 1997, 21, 141–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yau, Y. Homeowner involvement, land readjustment, and sustainable urban regeneration in Hong Kong. J. Urban Technol. 2012, 19, 3–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turk, S.S.; Korthals Altes, W.K. Potential application of land readjustment method in urban renewal: Analysis for Turkey. J. Urban Plan. Dev. 2010, 137, 7–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixon, T.; Otsuka, N.; Abe, H. Critical success factors in urban brownfield regeneration: An analysis of ‘hardcore’ sites in Manchester and Osaka during the economic recession (2009–2010). Environ. Plan. A 2011, 43, 961–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alterman, R. Land use regulations and property values: The ‘windfalls capture’ idea revisited. In Oxford Handbook on Urban Economics and Planning; Brooks, N., Donanghy, K., Knapp, G.J., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2012; Chapter 33; pp. 755–786. [Google Scholar]

- Yau, Y.; Cheng, C.Y. Applicability of land readjustment in urban regeneration in Hong Kong. J. Urban Regen. Renew. 2010, 4, 19–32. [Google Scholar]

- Byahut, S. Post-earthquake reconstruction planning using land readjustment in Bhuj (India). J. Am. Plan. Assoc. 2014, 80, 440–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, T.C.; Ding, H.Y. Urban land readjustment in Taiwan. In Land Readjustment: Solving Urban Problems through Innovative Approach; De Souza, F.F., Ochi, T., Hosono, A., Eds.; Japan International Corporation Agency Research Institute: Tokyo, Japan, 2018; pp. 175–179. [Google Scholar]

- Bayartuvshin, G. Land readjustment in Mongolia. In Land Readjustment: Solving Urban Problems through Innovative Approach; De Souza, F.F., Ochi, T., Hosono, A., Eds.; Japan International Corporation Agency Research Institute: Tokyo, Japan, 2018; pp. 152–156. [Google Scholar]

- Cain, A.; Weber, B.; Festo, M. Community land readjustment in Huambo, Angola. In Global Experiences in Land Readjustment: Urban Legal Case Studies; Hong, Y.H., Tierny, J., Eds.; UN-Habitat: Nairobi, Kenya, 2018; Chapter 10; pp. 139–153. [Google Scholar]

- Turk, S.S.; Turk, C. The annulment of land readjustment projects: An analysis for Turkey. Town Plan. Rev. 2011, 82, 687–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çete, M. Turkish land readjustment: Good practice in urban development. J. Urban Plan. Dev. 2010, 136, 373–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostrom, E. Background on the institutional analysis and development framework. Policy Stud. J. 2011, 39, 7–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blumenstock, J.; Cadamuro, G.; On, R. Predicting poverty and wealth from mobile phone metadata. Science 2015, 350, 1073–1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazer, D.; Kennedy, R.; King, G.; Vespignani, A. The parable of Google Flu: Traps in big data analysis. Science 2014, 343, 1203–1205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, G. Jiulong Cheng Shi Lun Ji; Xian Chao Shu Shi: Hong Kong, China, 1987. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Blumenfeld, H. Theory of city form, past and present. J. Soc. Archit. Hist. 1949, 8, 7–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wesley-Smith, P. Unequal Treaty 1898–1997: China, Great Britain and Hong Kong’s New Territories; Oxford University Press: Hong Kong, China, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, G. The Kowloon City District and the clearance of the Kowloon Walled City: Personal recollections. J. R. Asiat. Soc. Hong Kong Branch 2011, 51, 257–278. [Google Scholar]

- Coase, R.H. The Federal Communications Commission. J. Law Econ. 1959, 2, 1–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urban Renewal Strategy Review, 21 September 2010. Available online: https://www.devb.gov.hk/filemanager/en/Content_3/LegCo%20Brief%20-%20URS%20Review%20(Eng).pdf (accessed on 22 April 2022).

- Williamson, O.E. The lens of contract: Private ordering. Am. Econ. Rev. 2002, 92, 438–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanjouw, J.O.; Levy, P.I. Untitled: A study of formal and informal property rights in urban Ecuador. Econ. J. 2002, 112, 986–1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murtazashvili, I.; Murtazashvili, J. The origins of private property rights: States or customary organizations? J. Inst. Econ. 2016, 12, 105–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; He, S. Informal property rights as relational and functional: Unravelling the relational contract in China‘s informal housing market. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 2020, 44, 967–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siegan, B.H. Non-zoning in Houston. J. Law Econ. 1970, 13, 71–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, L.W.C. “As planning is everything, it is good for something!”: A Coasian economic taxonomy of modes of planning. Plan. Theory 2016, 15, 255–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alston, L.J.; Mueller, B. Property rights and the state. In Handbook of New Institutional Economics; Menard, C., Shirley, M., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2008; pp. 573–590. [Google Scholar]

- Poon, A. Land and the Ruling Class; Alice Poon: Hong Kong, China, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Haila, A. Institutionalization of “the property mind”. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 2017, 41, 500–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, S.H.W. Real estate elite, economic development, and political conflicts in postcolonial Hong Kong. China Rev. 2015, 15, 1–38. [Google Scholar]

- Demsetz, H. Toward a theory of property rights. Am. Econ. Rev. 1967, 57, 347–359. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).