Abstract

Defining output specifications is a prerequisite for achieving Public-Private Partnership (PPP) procurement performance. Theoretically, user satisfaction is vital for output specifications, but it has received insufficient attention in theoretical research and practice. To explore the factors that influence the definition of output specifications, we took 6714 PPP projects as a sample and used the logit regression model to discuss the links between accountability and corruption in the definition of user satisfaction. We found the following: the stronger the accountability, the more emphasis the purchaser attaches to user satisfaction, whereas the higher the level of corruption, the less attention the purchaser places on user satisfaction. Robustness tests demonstrate the reliability of the effects of accountability and corruption on the attention paid to user satisfaction. The contributions of this study are as follows: (1) Theoretically, it provides a basis for user satisfaction as an important aspect of output specifications and new evidence on the impact of accountability and corruption on defining output specification; (2) institutionally, it provides advice for the optimization of output specifications in PPP procurement; and (3) practically, these findings are insightful for improving the definition of output specifications of PPP projects that can enhance performance in PPP projects.

1. Introduction

With the international promotion and application of Public-Private Partnerships (PPP) in recent years, how to realize their performance has become an important challenge faced by governments around the world and has increasingly attracted the attention of scholars [1,2]. As an important method of realizing performance [3,4,5], reducing transaction costs [3], promoting innovation and competition [6,7,8] and transferring procurement risks [9,10], Performance-based Procurement (PBP) has been widely used in jurisdictions such as the United States [11], the United Kingdom [12,13], the World Bank [14] and the African Development Bank [15]. This provides a route towards realizing PPP procurement performance. Specifically, as the core feature of PBP, output specification, which refers to defining performance goals based on outputs or outcomes [16], is crucial when it comes to realizing the performance of PPP procurement. In particular:

First, output specifications are the core of PBP [17]. Traditional procurement focuses on input specifications and tells the contractor how to execute the contract in detail. Instead, PBP focuses on output, outcome or quality. That is, the purchaser tells the contractor the expected results and gives them more freedom to decide what to do [18]. Thus, a core feature of PBP is to define specifications based on outputs or results, rather than inputs, activities and processes [17,19,20,21,22,23].

Second, output specifications are used as the premise to achieve performance in PPP procurement [24]. They are important documents for PPP project procurement and define which services/outputs are required and which performance objectives are to be achieved [16]. Many scholars have shown that output specification is an important factor affecting the success of PPP procurement [25,26]. Well-drafted output specifications are critical to the development of robust PPP contracts and the successful delivery of long-term services [27,28]. If the first stage of the procurement process, namely requirement specification, is not adequately carried out, other stages of the process, especially contract management, may become problematic [29]. In addition, output specifications also have a major impact on the tendering process and the cost as well as affordability of government agencies [30]. Furthermore, designing output-based specifications rather than input-based specifications in PPP projects encourages suppliers to adopt more innovative approaches in delivering projects [28], and meeting output specifications increases user satisfaction [26]. Additionally, the rules mandating the full implementation of budget performance management in general [31] and PPP performance management in China in particular [32] have laid a solid institutional foundation for the pursuit of performance in PPP procurement. This requires that procurement officials pursue performance in PPP procurement and define the project in terms of output specifications.

Therefore, it is very important and timely to study the issue of the definition of output specifications for PPP procurement.

Existing studies have already addressed certain aspects of the issue of the output specifications of PPP projects. Certain scholars have found that output specifications play an important role in the success of PPP procurement (e.g., Jefferies et al. [25], Osei-Kyei and Chan [26], Sanders and Lipson [27] and Lam and Javad [28]). Additionally, scholars have defined the output specifications of PPP projects from different perspectives. For example, Liang et al. (2019) [33], Hueskes et al. (2017) [23] and Akomea et al. (2022) [34] focused on the measurement of sustainable performance. Yuan et al. (2012) [35] identified 41 Key Performance Indicators (KPIs) to measure PPP performance, including stakeholder satisfaction indicators (e.g., public satisfaction and government satisfaction). Ahmad et al. (2021) [36] categorized a PPP project’s success in four dimensions, namely time, cost, objects and quality or stakeholder satisfaction, reporting that the last is the most significant. Ahmad et al. (2022) [37] developed a performance framework to evaluate the application of PPP projects based on 10 KPIs and 41 performance measures. Liyanage et al. (2015) [38] combined three perspectives including project management, stakeholder management and contract management into a holistic measure of the “overall” success of PPP transportation projects. Xiong et al. (2015) [39] and Yuan et al. (2018) [40] pointed out that the key contents of performance appraisal during the operational period of PPP projects should include project company management, daily maintenance safety and emergency management and public satisfaction.

To sum up, existing studies have found that output specifications play an important role in realizing PPP procurement performance, and stakeholder satisfaction is gradually being valued as an important element of output specification. These studies have laid a solid foundation for the study of output specifications, though the following gaps in knowledge can be noted: (1) It is still inconclusive as how to define the output specifications of PPP projects, especially in light of the observations that the public, as the main stakeholders of PPP projects, is faced with the dilemma of being marginalized in the process of PPP project advancement [41], and (2) existing studies have not paid enough attention to the factors that affect the definition of output specifications.

Given this context, this research aimed to fill these gaps by addressing the following questions:

1. How do you define the output specification of PPP projects, notably in terms of user satisfaction?

2. What factors influence the definition of output specifications?

To answer the above two questions, this study took the following two measures: (1) It defined important aspects of output specification through theoretical analysis, especially user satisfaction, and (2) for influencing factors, it analyzed the impact of procurement officials’ self-interest on the definition of output specifications from the two dimensions of corruption and accountability. The reason for this is that the definition of procurement specifications is a decision that is made by procurement officers who are usually self-interested when making decisions [42]. Taking into account the costs and benefits of the decisions, the procurement officer will make an evaluation, which plays a decisive role in explaining whether the officer engages in rule-breaking behavior [43]. Generally speaking, the costs include the likelihood of being discovered and the severity of sanctions, and benefits are usually monetary and may also include non-monetary factors [44]. The former is usually associated with accountability, while the latter is usually associated with corruption. In PPP procurement, these two factors are also particularly prominent. Specifically, on the one hand, PPP procurement regulations have placed constraints on the behavior of procurement officers, and to avert risk from accountability, officers are more inclined to contain their behavior under the constraints of rules [42]. On the other hand, corruption is also one of the main risks faced by PPP projects in developing countries [45], and the procurement sector is highly vulnerable to corruption [46]. In particular, based on the data of 6714 PPP projects in China, we used the Logit regression model to empirically analyze the impact of the two dimensions of accountability and corruption on the definition of output specifications.

The novelties of this paper are as follows: (1) it supplements the relevant research on PPP project output specifications from the perspective of user satisfaction, and (2) it provides the first empirical analysis of the factors influencing the definition of output specifications using data from PPP projects in China, which has become the world’s largest PPP market. This provides explanatory evidence for the factors that influence output specifications. These findings are insightful in the context of improving the definition of the output specifications of PPP projects, which can enhance performance in PPP projects.

This paper commences with a theoretical analysis and research assumptions to provide theoretical support. Then, the research design and empirical results are presented. Next, this paper discusses the results and certain policy implications. Finally, conclusions are presented.

2. Theoretical Analysis and Research Assumptions

2.1. User Satisfaction: An Important Aspect of Output Specifications

User satisfaction is an important aspect of the output specifications of PPP procurement. The reasons are at least twofold:

- (1)

- Insisting on user satisfaction in PPP procurement is the basic requirement of performance-based procurement reform. The pursuit of user satisfaction is rooted in the concept of public-oriented government performance management. Since the 1990s, government governance has entered the “post-new public management era”, which expands the theory of new public management and takes “public orientation” as the basic concept of government performance evaluation. Public orientation is a further development of results orientation. Based on results orientation, it closely integrates results with stakeholder participation, demand expression and the provision of one-stop overall services, focusing on the needs and satisfaction of the public [47]. Public orientation reflects “citizen-orientation” and the pursuit of putting “public satisfaction first”. Its essence lies in: (a) listening to the public’s voice and responding to the public’s needs; (b) giving the public the right to choose; (c) realizing the public’s active participation in the whole process of public service (design, delivery and result evaluation, etc.); and (d) taking public satisfaction as the fundamental criterion for judging the quality of government work. It answers the question of “who is it for” in all government management activities and involves the ultimate goal and fundamental value choice of government management [48]. If administrators consistently focus on the results in terms of public satisfaction, the level of public service will improve [49]. In addition, user satisfaction is in line with the scientific development of the concept of “people-oriented” development and reflects the essential requirements of a service-oriented government in China. Since 2018, China has begun to vigorously promote the reform of performance management and adopted the full implementation of budget performance management in general, requiring that “government expenditure must be accountable for results and ineffectiveness must be held accountable.” For government procurement, the newly released Draft of the Government Procurement Law (2022) incorporates performance requirement as one of the basic legal principles, which provides a more solid legal ground for performance-based PPP procurement. Moreover, guidance issued by the Ministry of Finance (MoF) [41] has been specifically provided for the road map for PPP procurement performance management. Against this theoretical and institutional background, it can be argued that a primary goal of PPP procurement is to meet public needs, and the output specifications of PPP procurement is to be defined in terms of user satisfaction.

- (2)

- The emphasis on user satisfaction is the basic requirement of performance-based PPP procurement. Specifically, PPP refers to a partnership between the public and the private sector to provide public goods or services based on a franchise agreement [50]. Based on the theory of public goods, the starting point and foothold of PPP are publicness and the pursuit of public interests, and its primary goal is to provide public services to the public to meet public needs [51]. PPPs bring together the public and private sectors in a medium to long-term partnership, enabling each party to combine their particular skills to serve the needs and interests of the public [52]. Among them, the private sector assumes responsibilities related to the design, financing, construction and operation of facilities, while the public sector plays the main role in providing services to citizens [52]. In any PPP project, the main stakeholder of the public sector is the public. The government and its respective agencies, acting as agents of the public, need to meet the needs of the general public [52]. Studies such as those by Prefontaine et al. (2000) [53] and Henjewele et al. (2013) [41] have also pointed out that the public, as the main stakeholder of PPP projects, should move from the edge to the center in terms of basic decision-making, and the failure to manage stakeholders (especially key stakeholders) will lead to the failure of most projects. This supports the thesis of our paper. In addition, many studies have shown that the public satisfaction with a project is an important indicator of a project’s success [54,55,56]. Moreover, it should be noted that certain PPP-related policy documents [57] in China have also clarified that the maximization of public interests is the basic principle of PPP procurement. These have provided an important institutional basis for PPP procurement to pursue user satisfaction.

To sum up, this study takes user satisfaction as a key element of output specifications and explores the factors that influence the definition of output specifications.

2.2. Factors Influencing the Definition of Output Specifications

2.2.1. Accountability

The institutional environment is an important factor which affects PPP procurement performance [58]. In general, the continued growth and mobilization of private investment in infrastructure through PPP is largely dependent on a favorable institutional environment and regulatory conditions within a country [1]. Opara et al. (2017) [59] showed that a favorable policy environment is one of the prerequisites for the successful implementation of PPPs. Accountability, as a powerful measure to restrain actors in an institutional system, will affect the definition of procurement specifications. The reasons for this are twofold:

- (1)

- The procurement officer has discretion in defining the procurement specifications of the PPP project. Although there is a requirement [60] that procurement specifications are clear, specific and measurable, it is difficult to make uniform normative specifications due to the differences in procurement specifications for different PPP projects.

- (2)

- Officers inevitably have a risk aversion preference in the process of exercising discretion [42]. When accountability is strong, officers will tend to follow the rules, as explained by social-psychological theories. For example, in the norm activation model, there is often a tendency to study why people obey the law [61]. When the rules are easier to break and compliance is more challenging, people are more likely to break the rules. Conversely, when breaking the rules is more difficult and compliance is easier, people are more inclined to follow the rules. Furthermore, viewed from the perspective of cost and benefit evaluation, when sanctions are high, the cost of breaking the rules increases and people are more inclined to follow the rules [44].

PPP has been advancing rapidly in China since 2014; however, there have also been challenges such as the incorporation of PPPs into new financing platforms and an increase in hidden government debt risks [62]. As a result, ministries and commissions led by the MoF and the National Development and Reform Commission began to issue a series of rules with the purpose of: (1) Regulating the operation of PPP projects; (2) promoting the transformation of PPPs from high-speed development to high-quality development; and (3) improving the quality and efficiency of PPP projects, effectively improving the quality of public services [63]. Correspondingly, accountability has grown. Therefore, officers are more inclined to follow the rules and pay more attention to procurement quality and results to achieve public interests. In summary, we propose:

Hypothesis 1.

The stronger the accountability, the more attention the procurement officer attaches to user satisfaction when defining the output specifications of the PPP project.

2.2.2. Corruption

Corruption is one of the main obstacles to sustainable socioeconomic and political development in advanced, developing and emerging economies. It acts not only to increase inequality but also reduce efficiency [64]. The procurement sector has been identified as the most vulnerable to corrupt activities [46,65]. Specifically, in the procurement of PPP projects, corruption is an important factor affecting the success of PPP projects [66] and impacts on the entire life cycle of the project [67]. For example, in the project planning stage, procurement officials may tend to create environments in which there is poor and inaccurate oversight to discourage the detection of corrupt practices and define the projects in a way to favor a particular bidder.

In the procurement of PPP projects, corruption will affect the decision-making of the procurement officer and then affect the pursuit of user satisfaction in the definition of procurement specifications. Officers who commit corrupt practices often tend exclude public participation from decision-making. The reasons for this are as follows:

Theoretically, the participation of users will affect the corrupted collusion between purchasers and suppliers. According to the principal-agent theory, the principal and the agent each represent different interests. When the two interests conflict, the agent often chooses a behavior that is beneficial to him [52]. In an environment where corruption thrives, purchasers may exclude public participation in decision-making to serve their interests and reduce the possibility of corruption being detected. This is because public participation is an important way to curb corruption. With the continuous improvement of national governance, the supervision of public participation is playing an increasingly important role [68]. The people are the grassroots, and they are both victims of corruption and the most reliable force against corruption. Mobilizing the power of the public can detect corruption that infringes upon the interests of the public. Therefore, the active participation of the public is essential to curb corruption to the greatest extent possible [69]. In PPP projects, the public is the principal, the government is the agent, and the agent may make unpopular decisions in the PPP project by ignoring public complaints [52]. Moreover, the agent may have more or better-quality information than the principal in PPP procurement; thus, it is possible to take action against the principal without fear of being held accountable. For instance, it is known that under the guise of commercial sensitivity, requests for information on value for money can be rejected [70].

From a practical point of view, the experience of building a clean government in Hong Kong, Singapore and other places has shown that public participation in supervision has played an important role in the effective governance of corruption [71]. The Chinese government has always emphasized the role of public participation in the socialist democratic political system, especially in the areas of anti-corruption and state supervision. In addition, corruption is also an important topic of public concern. Every exposure of corruption will be accompanied by public discussion and criticism, and many people are willing to participate in anti-corruption [72]. In particular, in PPP projects, the question of how to balance the economic and social benefits, immediate interests and long-term interests as well as local interests and overall interests, generally receives strong attention from society [73]. In PPP procurement, the payment of fees is linked to user satisfaction once the procurement officer defines user satisfaction in the output specifications. As a result, the government and the private sector pay more attention to the quality of projects in the process of cooperation, and the public are able to play a supervisory role, thereby curbing corruption.

To summarize, considering the important role of the public in detecting and controlling corruption, procurement officials will try to avoid public participation in decision-making to avoid public scrutiny. Therefore, we propose:

Hypothesis 2.

The higher the degree of corruption, the less attention the procurement officer attaches to user satisfaction when defining the output specifications of PPP projects.

3. Research Design

3.1. Sample Data and Sources

This study depended on the data set constructed from China’s mega PPP project database. According to the data of the project database of the PPP Center of the MoF of China, from 1 January 2009 to 21 March 2021, the number of projects reached 10,081, and the number of procurement documents is 9591. To identify PPP projects with user satisfaction in the procurement specifications, the Nvivo software was used to analyze the text content of procurement documents, and word frequency queries on procurement documents that contain “satisfactory” were conducted. A total of 8008 reference points were acquired. Then, to more accurately screen out the procurement documents that define user satisfaction, we manually read each reference point and selected the procurement documents that define “user (public) satisfaction” in performance indicators. Furthermore, duplicate projects were removed. As a result of this process, a data set of 6714 valid PPP projects were obtained. Among them, 1478 PPP projects paid attention to user satisfaction, and 5236 PPP projects did not. The data of PPP project procurement documents are from the official website of the PPP Center of the MoF.

3.2. Model

The dependent variable is whether user satisfaction is included in the performance indicators of procurement documents. It is a dichotomous variable, so the logit regression model was used for estimation [74]. When user satisfaction is included in the performance indicator, the value is 1. If not, the value is 0.

The independent variables are divided into two aspects: accountability and corruption. Among them, accountability refers to the strength of PPP procurement rules to regulate performance-based PPP procurement; corruption refers to the degree of corruption of local government officials. The specific indicators and data sources are as follows:

In the accountability dimension, the release time of Caibanjin (2017) 92 [75] is used to distinguish the strength of accountability. On 10 November 2017, the MoF issued the Caibanjin (2017) No. 92, which requires each provincial finance department to conduct a centralized review of their project management database. The centralized review of project databases is a comprehensive check of PPP projects. Its purpose is to release the vitality of the real PPP model, so that the PPP project can be standardized and implemented smoothly. The issuance of this document has encouraged the regulation of the development of PPPs, and accountability has also become stronger. Therefore, the accountability of PPP projects initiated before 10 November 2017 is relatively weak and is recorded as 0; the accountability of PPP projects initiated after 10 November 2017 is relatively strong and is recorded as 1. The project initiation time data were obtained from the Wind database.

For corruption, the number of crimes of corruption and malfeasance is used as the measure. The reasons for this are as follows: Raymond and Roberta (2002) [76] used the number of civil servants convicted of abuse of power as a measure of the level of corruption in the United States and obtained satisfactory results, with them pointing out that the crime rate of the abuse of power by civil servants is a reasonable indicator of the true level of corruption. Zhou and Tao (2009) [77] used the total number of corruption cases in the region as an indicator of the degree of corruption. This study drew on the above research and used the number of indictments filed by the procuratorate for crimes of corruption and malfeasance in the province as an indicator to measure the degree of corruption. The data were obtained from the PKULAW database.

In addition, referring to studies such as those by Cao and Wang (2022) [42] and Wang et al. (2019) [78], this study mainly determined the impact of project characteristics on procurement officials’ decision-making. These project characteristics include: project investment, duration, return model, region and demonstration type. The model takes into account most of the characteristics of a PPP project. There may be other factors related to the definition of output specifications, but due to data limitations, this study could not include all possible factors. In this model, when observing the influence of an explanatory variable on the explained variable, other variables in the model are control variables. The above data were obtained from the Wind database.

The regression model is as follows:

The data set comprised a set of observations of the dichotomous dependent variable, user satisfaction, , where i = 1, …, 6714, and a set of K independent and control variables X. The data were from a set of m provinces (m < i) and the measure of corruption varies across provinces but is a single value for each province. is the intercept term and is the residual. There were 34 provinces. To determine multicollinearity, a Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) test was performed. We found that the VIF values of all variables are less than 2, which indicates that the model does not have serious multicollinearity problems. Additionally, to alleviate endogenous findings, the following two measures were taken: (1) the full sample of PPP projects in China was used as the analysis object to sample selection bias, and (2) as many control variables as possible were added to the model to mitigate omitted variable bias.

Table 1.

Description of variables.

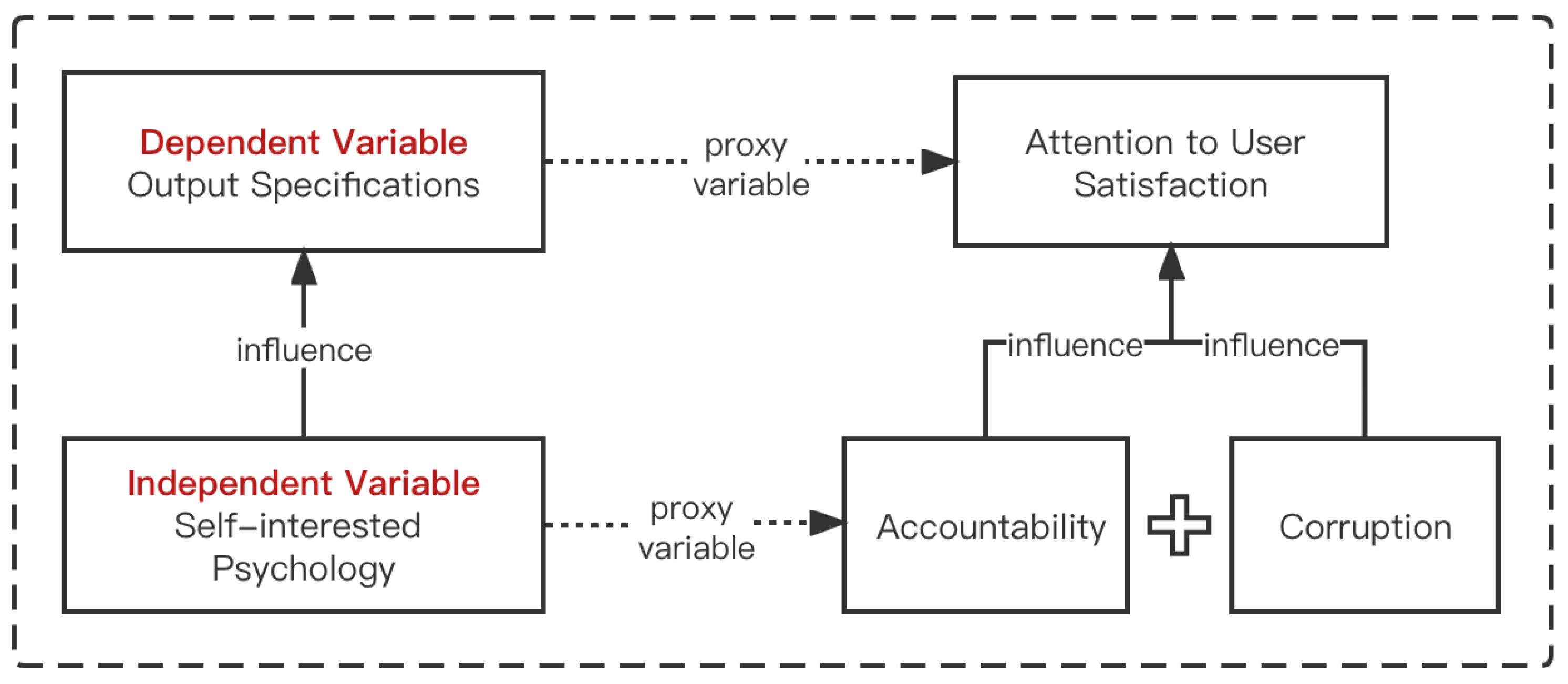

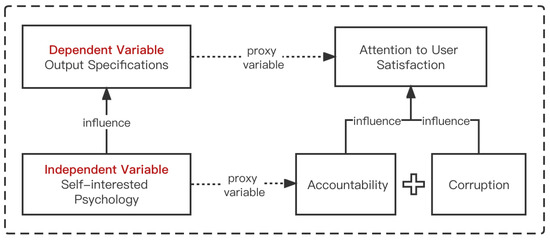

Figure 1.

Analysis framework.

4. Empirical Results

4.1. Descriptive Statistics

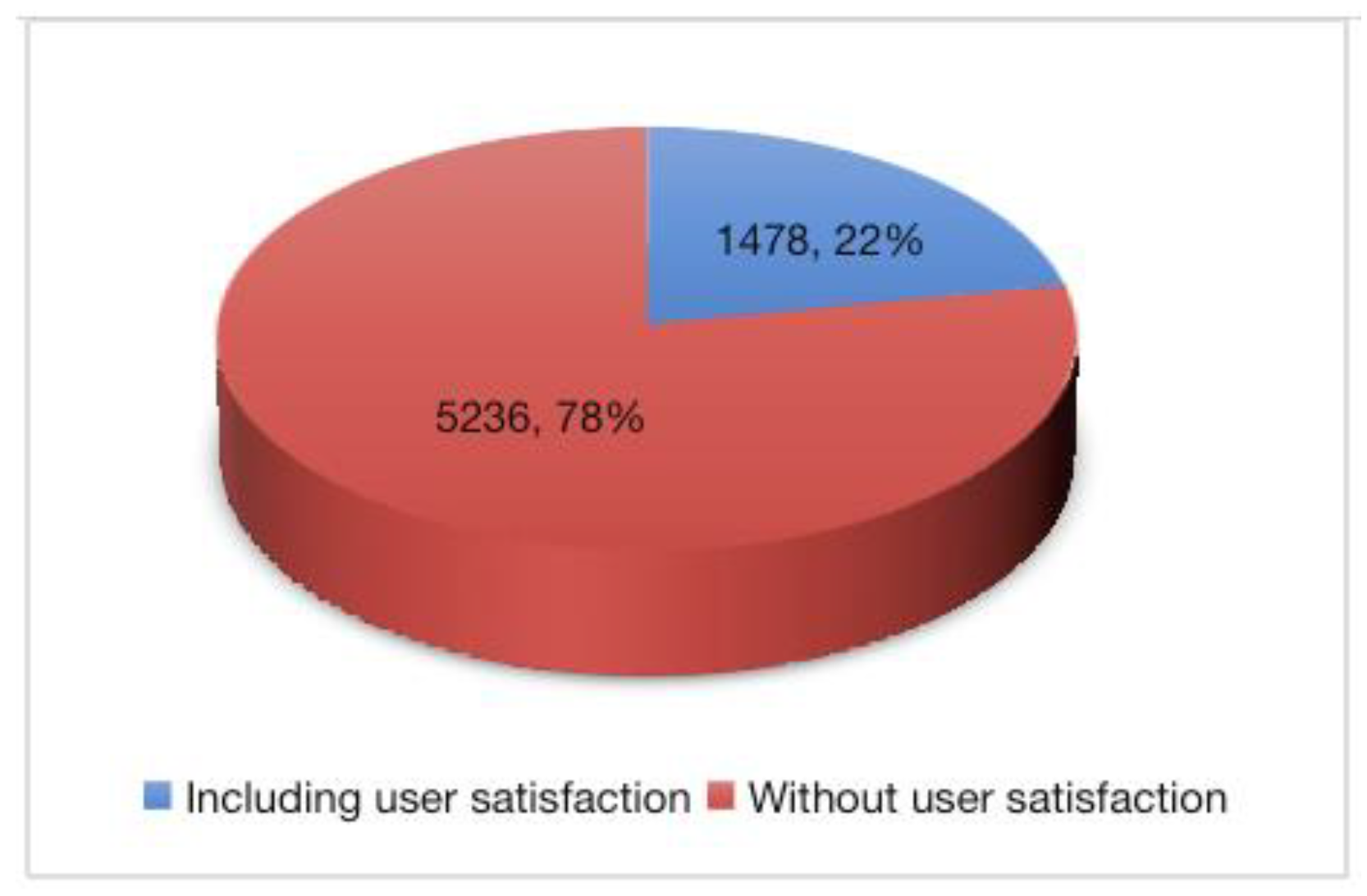

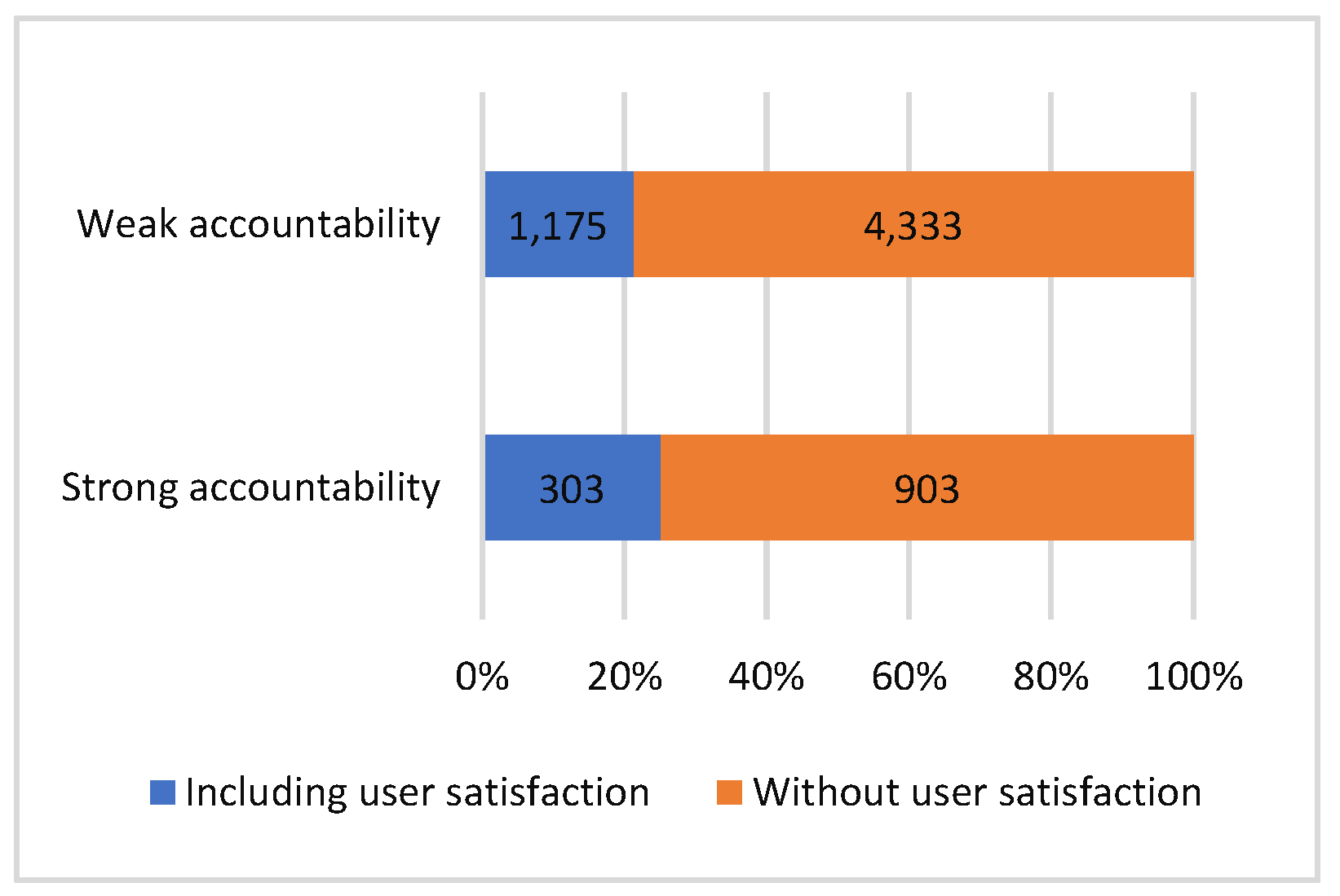

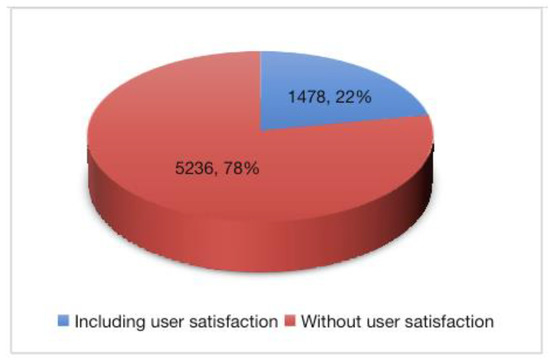

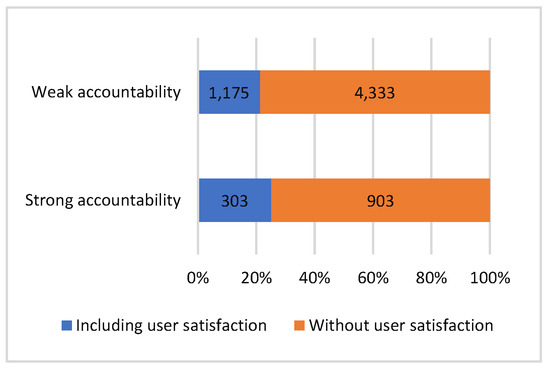

Figure 2 and Figure 3 report the distribution of user satisfaction in the PPP project performance indicators and the distribution of user satisfaction under different accountability levels. As can be seen from Figure 2, the number of PPP projects whose performance indicators include user satisfaction is relatively small, with these accounting for only 22%; the performance indicators of most PPP projects do not include user satisfaction, with these accounting for 78%. Figure 3 shows that compared with the situation of weak accountability, the proportion of user satisfaction in the PPP project performance indicators is higher when the accountability is stronger. Table 2 presents descriptive statistics of corruption levels. Notably, descriptive statistics is only a preliminary description of variables. To obtain an accurate relationship between the dependent variable and independent variables, it is necessary to carry out standardized regression.

Figure 2.

Distribution of the number of PPP projects on user satisfaction.

Figure 3.

Distribution of user satisfaction of PPP projects under different accountability levels.

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics of corruption level.

4.2. Regression Results

Table 3 reports the baseline regression result, which shows that:

Table 3.

Baseline regression result.

First, at the level of accountability, while controlling for other variables, the stronger the accountability, the more attention the procurement officer attaches to user satisfaction when defining the output specifications of the PPP project. Therefore, Hypothesis 1 is verified.

Second, for corruption, while controlling for other variables, the higher the degree of corruption, the less attention the procurement officer attaches to user satisfaction when defining the output specifications of PPP projects. Thus, Hypothesis 2 is verified.

4.3. Robustness Test

4.3.1. Robustness of Key Variables

To test the robustness of key variables, this study chose the method of replacing proxy variables and used the number of normative documents in the region before the project was initiated to replace the degree of accountability for regression. The reasons for this are as follows: Policy documents are the materialized form of government behavior and awareness, and the number of policy documents directly reflects the importance that leaders attach to related issues [79]. The greater the number of policy documents, the stronger the constraints on officers. Accordingly, officers are more likely to be held accountable. Therefore, the number of PPP-related normative documents in the region where the project was launched was selected as the proxy variable of accountability. The data were obtained from the PKULAW database. Table 4 shows that as the number of normative documents increases, the number of projects that define user satisfaction in procurement specifications increases. This confirms the robustness of the benchmark regression results.

Table 4.

Replacement proxy variable regression results.

4.3.2. Robustness of Regression Methods

To test the robustness of the estimation method, logit regression was replaced by Probit regression, and Table 5 could be obtained. The regression results are consistent with the conclusions drawn from the benchmark regression. This shows that the regression method used in this study is robust.

Table 5.

Regression results of alternative estimation methods.

4.3.3. Adding Control Variables

Furthermore, we added procurement method and industry type as control variables to test the robustness of the benchmark regression results. Table 6 reports the results, which are consistent with the benchmark regression results. This further confirms the robustness of the benchmark regression results.

Table 6.

Regression results after adding control variables.

5. Discussion

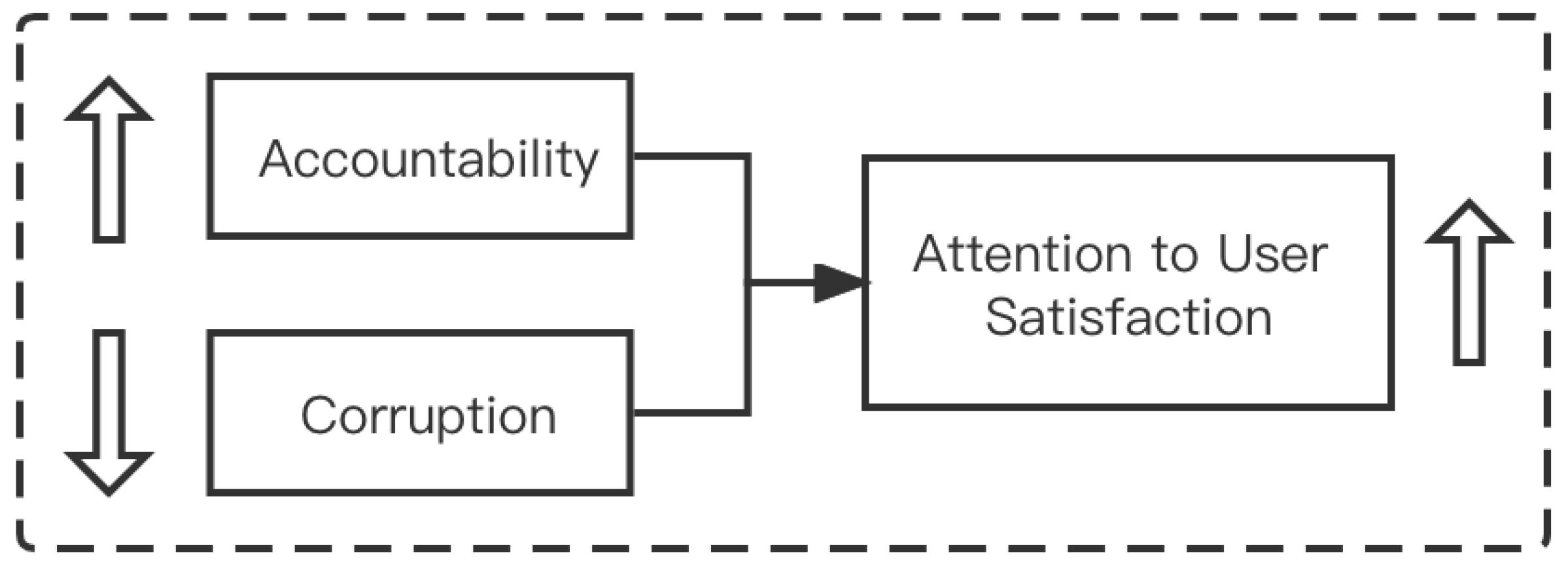

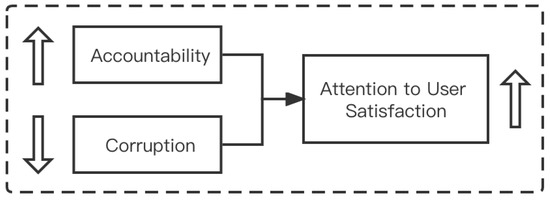

Through theoretical analysis, we argued that user satisfaction is a key aspect of output specification. However, practical observation shows that only 22% of PPP projects pay attention to user satisfaction in procurement specifications and 78% of PPP projects do not pay attention to user satisfaction in procurement specifications. Through further empirical analysis, this study found that the definition of user satisfaction is influenced by the degree of accountability and corruption. A schematic graphical presentation of the regression results is shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Schematic presentation of regression results.

On the one hand, the level of accountability affects the definition of user satisfaction in procurement specifications. The stronger the accountability, the more emphasis there is on user satisfaction in PPP procurement. This confirms the positive effect of an effective governance environment on the success of PPP projects from the perspective of procurement specifications and also confirms the views of Zhang et al. (2015) [58], Casady (2020) [1] and others. Admittedly, certain rules on standardizing the implementation of PPP projects have strengthened the emphasis on user satisfaction in PPP procurement, but the lack of attention paid to user satisfaction in PPP procurement practice raises reasonable doubt on the effectiveness of existing rules. For instance, the rules of the MoF [32] recommend paying attention to the satisfaction of the public sector, private sector and user, but it is not mandatory, which may result in a reduced guiding effect in practice. Only by adhering to user-oriented procurement can government procurement truly gain the trust and support of the public and gain momentum for sustainable development. Government procurement should be “user-oriented”, focused on user needs and be aimed towards user satisfaction. In government procurement, the purchaser, as the user’s agent, proposes procurement specifications on behalf of the user. These specifications should be designed according to the needs and the satisfaction of users. Therefore, it is necessary to further standardize the definition of PPP procurement specifications, pay attention to the importance of user satisfaction in output specifications and strengthen accountability measures for corresponding behaviors, thereby laying a solid foundation for achieving performance-oriented PPP procurement goals.

On the other hand, corruption also affects the definition of user satisfaction in procurement specifications. Regions with higher levels of corruption place less emphasis on user satisfaction. This result confirms the view of Owusu et al. (2017) [67] that procurement officials tend to create an unfavorable regulatory environment to suppress the exposure of corruption. The user is the direct service object of any PPP project, and the consideration of user satisfaction will undoubtedly increase the supervision of the behavior of government officials. This is also an important reason why regions with higher levels of corruption pay less attention to user satisfaction. Although some existing rules of PPP procurement provide routes for public participation in governance, public participation has not yet been paid enough attention in the definition of procurement specifications. Specifically, first, to protect the public’s right to know, PPP project information is legally disclosed on the PPP comprehensive information platform [80]. Second, the establishment of a comprehensive evaluation system in which the government and service users participate together and conduct performance evaluations on performance objectives including public satisfaction is required [57]. However, the above routes are mainly aimed at information disclosure and post-project performance evaluation, and there is no route in terms of regulation for public participation in the definition of procurement specifications. In addition, for the definition of specific procurement specifications, the rules [60] only stipulate that procurement projects involving public interests and high social concern, including public service projects provided by the government to the public, should carry out specification surveys. However, the specific method of investigation has not been further specified. The Caijin (2020) No. 13 [32] regulates the definition and management of PPP project performance objectives and indicators, but the definition of performance objectives and indicator systems is only for relevant departments and potential private sectors and the role of users has not been clearly defined. To sum up, none of the above rules mention the importance of public participation in the definition of procurement specifications. However, a socially engaged corruption governance system is an effective route to corruption governance [68]. Without the participation and cooperation of the public, many anti-corruption measures of the government may be in vain, the implementation costs of anti-corruption policies will increase sharply and the actual effect will be greatly reduced [71]. Moreover, as the direct audience of PPP projects, the public can potentially not only monitor corrupt behavior but also directly describe the specifications for PPP projects. Therefore, public participation should be strengthened in the process of defining procurement specifications to reduce the impact of corruption on procurement process.

6. Conclusions

Defining output specifications is a basic prerequisite for achieving PPP procurement performance. Referring back to the first research question, it can be seen from the theoretical analysis that user satisfaction is an important aspect of the output specifications of PPP procurement. However, theoretical research has not paid enough attention to this. Moreover, according to the practice of PPP procurement in China, we can see that PPP procurement does not pay enough attention to user satisfaction. Therefore, referring back to the second research question, based on the perspective of user satisfaction, this study empirically analyzed the factors that influence the definition of output specifications from the two dimensions of accountability and corruption with a sample of 6714 PPP projects in China. The study found that: (1) the stronger the accountability, the more attention the procurement officer of PPP project attaches to user satisfaction, and (2) the higher the level of corruption, the less attention is paid to user satisfaction by PPP project officials. The above findings validate the hypothesis of this study.

The contributions of this research are as follows: (1) Theoretically, it focused on the importance of user satisfaction in output specifications and analyzed the impact of accountability and corruption on the definition of output specifications through empirical research. This complements related research on user satisfaction in PPP procurement and explores the factors that influence the definition of output specifications. (2) Institutionally, the above findings also have important policy implications. The definition of PPP procurement specifications in China should be further standardized, and attention should be paid to the importance of user satisfaction in output specifications. In addition, public participation should be encouraged when defining procurement specifications to reduce the impact of corruption on the procurement process. (3) Practically, these findings are insightful in the context of improving the definition of the output specifications of PPP projects, which can enhance performance in PPP projects. They may also be valuable for decision-makers and authorities relevant to the PPP arrangement.

However, there are also some limitations to this study. First, (1) the study only focused on the aspect of user satisfaction and did not examine other components of output specifications. For example, a cooperation model that pursues mutual benefit and win–win results implies that the needs of other stakeholders should also be met. However, as an important aspect of output specifications, user satisfaction is more important. Second, (2) they study focused only on the impact of corruption and accountability on the definition of output specifications. In future research, important aspects and factors that influence output specifications should be explored from other perspectives.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, F.C. and C.W.; methodology, C.W.; software, C.W.; validation, F.C. and C.W.; formal analysis, F.C. and C.W.; data curation, C.W.; writing—original draft preparation, C.W.; writing—review and editing, F.C. and C.W.; supervision, F.C.; project administration, F.C.; funding acquisition, F.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Social Science Foundation of China, grant number 15ZDB174.

Data Availability Statement

All data presented are available upon request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Casady, C.B. Examining the institutional drivers of Public-Private Partnership (PPP) market performance: A fuzzy set Qualitative Comparative Analysis (fsQCA). Public Manag. Rev. 2020, 23, 981–1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delhi, V.S.K.; Mahalingam, A. Relating Institutions and Governance Strategies to Project Outcomes: Study on Public–Private Partnerships in Infrastructure Projects in India. J. Manag. Eng. 2020, 36, 04020076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchanan, N.; Klingner, D.E. Performance-based Contracting: Are We Following the Mandate? J. Public Procure. 2007, 7, 301–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doer, K.; Lewis, I.; Eaton, D.R. Measurement Issues in Performance-based Logistics. J. Public Procure. 2005, 5, 164–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J. The Performance of Performance-Based Contracting in Human Services: A Quasi-Experiment. J. Public Adm. Res. Theory 2015, 26, 277–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gooden, V. Contracting and Negotiation: Effective Practices of Successful Human Service Contract Managers. Public Adm. Rev. 1998, 58, 499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Straub, A. Cost savings from performance-based maintenance contracting. Int. J. Strat. Prop. Manag. 2009, 13, 205–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambaw, B.A. Performance-based contracting in public procurement of developing countries. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Twente, Enschede, The Netherlands, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Gruneberg, S.; Hughes, W.; Ancell, D. Risk under performance-based contracting in the UK construction sector. Constr. Manag. Econ. 2007, 25, 691–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tate, W.L.; Ellram, L.M.; Bals, L.; Hartman, E.; van der Valk, W. An Agency Theory Perspective on the Purchase of Marketing Services. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2010, 39, 806–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Office of Federal Procurement Policy/Office of Management and Budget (OFPP/OMB). A Guide to Best Practices for Performance-Based Service Contracting; OFPP/OMB: Washington, DC, USA, 1998.

- Morse, A. Outcome-based Payment Schemes: Government’s Use of Payment by Results: Report; National Audit Office: London, UK, 2015; p. 19.

- HM Government. Open Public Services White Paper; Cm 8145; The Stationery Office Limited: London, UK, 2011; Paragraphs 5.4.

- The World Bank. Procurement of Goods, Works, and Non-Consulting Services. Available online: http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/634571468152711050/pdf/586680BR0procu0IC0dislosed010170110.pdf (accessed on 26 August 2022).

- African Development Bank. Rules and Procedures for Procurement of Goods and Works; ADBG: Abidjan, Ivory Coast, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Yescombe, E.R. Public-Private Partnerships: Principles of Policy and Finance; Butterworth-Heinemann: Oxford, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Selviaridis, K.; Wynstra, F. Performance-based contracting: A literature review and future research directions. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2015, 53, 3505–3540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, L.L. Performance-Based Contracting for Human Services. Adm. Soc. Work. 2005, 29, 63–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Honore, P.A.; Simoes, E.J.; Moonesinghe, R.; Kirbey, H.C.; Renner, M. Applying Principles for Outcomes-basedContracting in a Public Health Program. Public Health Manag. Pract. 2004, 10, 451–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kashiwagi, D.T. The Development of the Performance-basedProcurement System (PBPS). J. Constr. Educ. 1999, 4, 196–206. [Google Scholar]

- Martin, L.L. Performance-based Contracting for Human Services: A Proposed Model. Public Adm. Q. 2007, 31, 130–151. [Google Scholar]

- Ssengooba, F.; McPake, B.; Palmer, N. Why performance-based contracting failed in Uganda – An “open-box” evaluation of a complex health system intervention. Soc. Sci. Med. 2012, 75, 377–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hueskes, M.; Verhoest, K.; Block, T. Governing public–private partnerships for sustainability: An analysis of procurement and governance practices of PPP infrastructure projects. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2017, 35, 1184–1195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javed, A.A. A Model of Output Specifications for Public-Private Partnership Projects. Ph.D. Thesis, Hong Kong Polytechnic University, Hong Kong, China, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Jefferies, M.; Gameson, R.; Rowlinson, S. Critical success factors of the BOOT procurement system: Reflections from the Stadium Australia case study. Eng. Constr. Archit. Manag. 2002, 9, 352–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osei-Kyei, R.; Chan, A.P.C. Comparative Analysis of the Success Criteria for Public–Private Partnership Projects in Ghana and Hong Kong. Proj. Manag. J. 2017, 48, 80–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanders, S.; Lipson, M. Output Specifications for PFI Projects: A 4P’s Guide for Schools; Public-Private Partnerships Programme (4Ps): London, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Lam, P.T.I.; Javed, A.A. Comparative Study on the Use of Output Specifications for Australian and U.K. PPP/PFI Projects. J. Perform. Constr. Facil. 2015, 29, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asadabadi, M.R.; Chang, E.; Zwikael, O.; Saberi, M.; Sharpe, K. Hidden fuzzy information: Requirement specification and measurement of project provider performance using the best worst method. Fuzzy Sets Syst. 2019, 383, 127–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, H.; Carrillo, P.; Anumba, C.J.; Patel, M. Governance & Knowledge Management for Public-Private Partnerships, 1st ed.; Wiley: Chichester, UK; Malden, MA, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- The State Councial. Available online: http://www.gov.cn/zhengce/2018-09/25/content_5325315.htm (accessed on 23 August 2022).

- China Public-Private Partnership Center. Available online: https://www.cpppc.org/czb/1591.jhtml (accessed on 26 August 2022).

- Liang, Y.; Wang, H. Sustainable Performance Measurements for Public–Private Partnership Projects: Empirical Evidence from China. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akomea-Frimpong, I.; Jin, X.; Osei-Kyei, R. Mapping Studies on Sustainability in the Performance Measurement of Public-Private Partnership Projects: A Systematic Review. Sustainability 2022, 14, 7174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, J.; Wang, C.; Skibniewski, M.J.; Li, Q. Developing Key Performance Indicators for Public-Private Partnership Projects: Questionnaire Survey and Analysis. J. Manag. Eng. 2012, 28, 252–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, U.; Waqas, H.; Akram, K. Relationship between project success and the success factors in public–private partnership projects: A structural equation model. Cogent Bus. Manag. 2021, 8, 1927468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, Z.; Mubin, S.; Masood, R.; Ullah, F.; Khalfan, M. Developing a Performance Evaluation Framework for Public Private Partnership Projects. Buildings 2022, 12, 1563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liyanage, C.; Villalba-Romero, F. Measuring Success of PPP Transport Projects: A Cross-Case Analysis of Toll Roads. Transp. Rev. 2015, 35, 140–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, W.; Yuan, J.-F.; Li, Q.; Skibniewski, M.J. Performance objective-based dynamic adjustment model to balance the stakeholders’ satisfaction in ppp projects. J. Civ. Eng. Manag. 2015, 21, 539–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, J.; Li, W.; Zheng, X.; Skibniewski, M.J. Improving Operation Performance of Public Rental Housing Delivery by PPPs in China. J. Manag. Eng. 2018, 34, 04018015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henjewele, C.; Fewings, P.; Rwelamila, P.D. De-marginalising the public in PPP projects through multi-stakeholders management. J. Financial Manag. Prop. Constr. 2013, 18, 210–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, F.; Wang, C. Factors Influencing Procurement Officers’ Preference for PPP Procurement Model: An Empirical Analysis of China. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 832617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, G.S. Crime and punishment: An economic approach. J. Political Econ. 1968, 169, 176–177. [Google Scholar]

- Gorsira, M.; Denkers, A.; Huisman, W. Both Sides of the Coin: Motives for Corruption Among Public Officials and Business Employees. J. Bus. Ethics 2018, 151, 179–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khahro, S.; Ali, T.; Hassan, S.; Zainun, N.; Javed, Y.; Memon, S. Risk Severity Matrix for Sustainable Public-Private Partnership Projects in Developing Countries. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishnan, C. Tackling Corruption in the Construction. Available online: https://www.transparency.org.uk/wp-content/plugins/download-attachments/includes/download.php?id=1032⟩ (accessed on 11 October 2016).

- Cao, T.; Shi, Q. Analysis of the Evolution of Government Performance Evaluation Based on the Paradigm of Government Governance—Also on the Path Selection of the Development of Chinese Government Performance Evaluation. Public Financ. Res. 2018, 3, 24–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J. Local government performance management based on the concept of public orientation. Adm. Trib. 2015, 1, 58–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimock, M.E. Government by Merit: An Analysis of the Problem of Government Personnel. Lucius Wilmerding, Jr. Am. J. Sociol. 1936, 42, 292–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, H. Government Positioning in PPP Model. Law Sci. 2015, 11, 17–23. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, S. The public nature of PPP and its analysis of economic law. Law Sci. 2015, 11, 9–16. [Google Scholar]

- Rwelamila, P.D.; Fewings, P.; Henjewele, C. Addressing the Missing Link in PPP Projects: What Constitutes the Public? J. Manag. Eng. 2015, 31, 04014085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prefontaine L, Ricard L, Sicotte H, et al. New Models of Collaboration for Public Service Delivery. 2008. Available online: https://www.ctg.albany.edu/media/pubs/pdfs/new_models_wp.pdf (accessed on 25 April 2000).

- Ruuska, I.; Teigland, R. Ensuring project success through collective competence and creative conflict in public–private partnerships – A case study of Bygga Villa, a Swedish triple helix e-government initiative. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2009, 27, 323–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Lv, L.; Wang, L. Analysis of the influencing factors of public satisfaction of water environment governance PPP project based on SEM. China Rural. Water Hydropower 2019, 5, 95–100+106. [Google Scholar]

- Li, H.; Lv, L.; Zuo, J.; Bartsch, K.; Wang, L.; Xia, Q. Determinants of public satisfaction with an Urban Water environment treatment PPP project in Xuchang, China. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2020, 60, 102244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The State Council. Available online: http://www.gov.cn/zhengce/content/2015-05/22/content_9797.htm (accessed on 26 August 2022).

- Zhang, S.; Gao, Y.; Feng, Z.; Sun, W. PPP application in infrastructure development in China: Institutional analysis and implications. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2015, 33, 497–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Opara, M.; Elloumi, F.; Okafor, O.; Warsame, H. Effects of the institutional environment on public-private partnership (P3) projects: Evidence from Canada. Account. Forum 2017, 41, 77–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Ministry of Finance. Available online: http://www.gov.cn/zhengce/zhengceku/2021-05/10/content_5605643.htm (accessed on 26 August 2022).

- Steg, L.; Vlek, C. Encouraging pro-environmental behavior: An integrative review and research agenda. J. Environ. Psychol. 2009, 29, 309–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, G.; He, X. Analysis of the Legal Consequences of PPP Projects withdrawing from the Treasury. ECUPL J. 2020, 1, 73–84. [Google Scholar]

- Economic Daily. Standardized Operation Promotes High-Quality Development of PPP. Available online: https://www.cpppc.org/PPPyw/996853.jhtml (accessed on 26 August 2022).

- Chan, A.P.C.; Owusu, E.K. Corruption Forms in the Construction Industry: Literature Review. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2017, 143, 04017057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Transparency International (TI). Global Corruption Report-2005; Pluto Press: London, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Chan, A.P.C.; Yeung, J.F.Y.; Yu, C.C.; Wang, S.Q.; Ke, Y. Empirical Study of Risk Assessment and Allocation of Public-Private Partnership Projects in China. J. Manag. Eng. 2011, 27, 136–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owusu, E.K.; Chan, A.P.C.; Shan, M. Causal Factors of Corruption in Construction Project Management: An Overview. Sci. Eng. Ethic. 2017, 25, 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C. Optimization Analysis of China’s Corruption Governance System. Thinking 2019, 4, 97–103. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.; Si, W. Fragmentation and improvement of public participation in anti-corruption in my country. J. Beijing Norm. Univ. (Soc. Sci.) 2021, 3, 144–152. [Google Scholar]

- Henjewele, C.; Sun, M.; Fewings, P. Critical parameters influencing value for money variations in PFI projects in the healthcare and transport sectors. Constr. Manag. Econ. 2011, 29, 825–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, X.; Ma, Z. The Influencing Factors and Effective Governance of Regional Corruption Tolerance: An Empirical Study Based on 314 Prefecture-level Administrative Regions in China. J. South China Norm. Univ. (Soc. Sci. Ed.) 2021, 1, 100–116+196. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, R.; Chi, G.; Cheng, L. Research on the Influence of Public Participation on the Effect of Government Auditing Corruption Governance—An Empirical Analysis Based on the Perspective of National Governance. J. Audit. Econ. 2018, 2, 19–28. [Google Scholar]

- Peng, Y.; Zhong, W. Official Background Characteristics and PPP Project Risk: A New Research Framework Based on Advanced Theory. J. Huaqiao Univ. (Philos. Soc. Sci.) 2022, 3, 70–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q. Econometrics and STATA Applications; Higher Education Press: Beijing, China, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- China Public-Private Partnership Center. Available online: https://www.cpppc.org/czb/996052.jhtml (accessed on 26 August 2022).

- Fisman, R.; Gatti, R. Decentralization and Corruption: Evidence from U.S. Federal Transfer Programs. Public Choice 2002, 113, 25–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; Tao, J. Government Scale, Marketization and Regional Corruption Research. Econ. Res. J. 2009, 1, 57–69. [Google Scholar]

- Pu, W.; Xu, F.; Chen, R.; Marques, R.C. PPP project procurement model selection in China: Does it matter? Constr. Manag. Econ. 2019, 38, 126–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Yao, Y.; Ye, Z. Influencing factors and development paths of provincial government big data development level under the TOE framework: Empirical research based on fsQCA. J. Intell. 2022, 1, 200–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Ministry of Finance. Available online: http://www.gov.cn/zhengce/zhengceku/2021-12/31/content_5665826.htm (accessed on 26 August 2022).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).