Character-Defining Elements Comparison and Heritage Regeneration for the Former Command Posts of the Jinan Campaign—A Case of Chinese Rural Revolutionary Heritage

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Development Background

1.2. Research Background and Review

1.3. Research Aim

- (1)

- When renovating and protecting rural revolutionary heritage, the use of new materials and technologies often violates the principle of authenticity and integrity in architectural heritage protection. Such means can damage the traces of time and historical value that make these buildings significant to our history.

- (2)

- Rural revolutionary heritage sites are often repurposed as exhibition halls or memorial halls, with a focus on showcasing grand narratives of revolutionary history and important figures. However, such an approach can sometimes result in overlapping content between exhibitions and a lack of interactive participation with visitors [40].

1.4. Paper Overview

2. Materials and Methodology

- (1)

- Historical study: This included the history of Jinan Campaign, the history of the command posts, and the reasons for the location and relocation of the two command posts during the Jinan Campaign.

- (2)

- Field investigation: This included field visits to the command post buildings, the villages, and the surrounding environment. Then, the next steps included taking photographs, identifying important environmental elements, conducting surveys, and creating architectural drawings.

- (3)

- Oral interviews: This included interviews with veterans, war witnesses and their families, docents of Cultural Relics Protection Units, heritage owners and their descendants, and other elderly villagers. The purpose was to supplement the historical study, and to explore the changes in use and spatial layout of the two command post buildings.

- (4)

- GIS analysis: This included analysis of the topographical features of the two command posts, and analysis of the sight line. The aim was to analyze the reasons for site selection.

- (5)

- Comparative research: An index system of character-defining elements was constructed from the aspects of architectural heritage, environment, and community, and the character-defining elements of the two command posts were compared.

3. Case Description

3.1. History of Jinan Campaign

3.2. The First Command Post in Tangjiagou Village

3.3. The Second Command Post in Yinjiadian Village

4. Discussion

4.1. Character-Defining Elements Comparison

- (1)

- Authenticity: The spiritual significance of rural revolutionary heritage lies in its authenticity, which is conveyed through its regional architectural culture, age, and history. The authenticity of revolutionary heritage refers to its historical existence from formation to recognition as a protected object. Engaging in modernized renovations can potentially compromise the authenticity of the revolutionary heritage.

- (2)

- Integrity: Regarding the integrity of rural revolutionary heritage, various elements are encompassed such as ruins, architectural remnants, spatial layout, street systems, and natural landscapes. The location selection and operation of the heritage during the revolutionary period are also important aspects of integrity.

- (1)

- Architectural heritage:

- a.

- vernacular architectural structure, material, technology, and craftsmanship;

- b.

- spatial configuration and interior layout; and

- c.

- using status and functional features.

- (2)

- Environment and Community:

- a.

- reasons for site selection and the relationship between the historic place and its broader setting;

- b.

- military and revolutionary uses embodied in the site selection; and

- c.

- customs and traditions that were or continue to be associated with the heritage.

- (1)

- Tangjiagou command post retains the original vernacular architectural structure, materials, style, spatial configuration, and form. However, Yinjiadian command post does not reflect the characteristics of local vernacular architecture due to improper renovations in the later period.

- (2)

- Tangjiagou command post is currently abandoned and lacks close ties to the rural community. As a result, there is potential for its conservation and regeneration, considering its feasibility and potential for utilization. Meanwhile, Yinjiadian command post has been transformed into an exhibition hall and hosted several visits and festival activities. It has become integrated into the daily life of local residents.

4.2. Tangjiagou Command Post: Gradual Regeneration

4.2.1. Phase 1: Preservation

4.2.2. Phase 2: Reuse

4.2.3. Phase 3: Self-Renovation

4.3. Yinjiadian Command Post: Conservation Planning

4.4. Guidelines for Regeneration of Rural Revolutionary Heritage

- (1)

- To protect rural revolutionary heritage, it is important to improve the structural integrity of architectural heritage while preserving its historical value. For severely damaged sites, efforts should be made to rescue and reinforce building walls and roof truss structures in order to ensure their survival.

- (2)

- It is crucial to prioritize the comprehensive preservation of rural revolutionary heritage along with their surrounding environments. The placement of many rural revolutionary heritage sites is contingent upon their surroundings, which exhibit traits such as defensibility, concealment, ease of transportation, and military observation. To ensure effective protection planning, research should be conducted to fully understand the heritage resources.

- (3)

- To effectively reuse rural revolutionary heritage, the unique local characteristics of the heritage sites should be considered. The correlation between heritage ontology and events, people, or historical facts should be examined as a prerequisite for rational reuse. By utilizing activities, forms, and exhibition methods that appeal to younger generations, cultural heritage can be passed down for future generations.

- (4)

- To renew the rural revolutionary heritage, it is of considerable significance to integrate local resources. This can be achieved through research that utilizes natural and human resources in rural areas. Further, immersive cultural experiences such as visiting revolutionary military parks, mountain expansion camps, and military lecture halls can be established.

- (5)

- To protect the rural revolutionary heritage, it is crucial to strike a balance between local government guidance and rural autonomy while also encouraging active participation from villagers. This can be accomplished by utilizing the industrial strengths of rural areas and integrating the preservation of heritage with development of unique industries. By adopting such an approach, focus can be gradually shifted from solely conserving rural revolutionary heritage to revitalizing these communities as a whole.

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Guide to the Protection and Utilization of the Former Revolutionary Site, 15 January 2019. Available online: http://www.gov.cn/guoqing/2014-07/21/content_2721159.htm (accessed on 15 May 2023).

- State Council of the People’s Republic of China. Interim Regulations on the Administration of Cultural Relics Protection. Bull. State Counc. People’s Repub. China 1961, 4, 76–79. [Google Scholar]

- Cultural Relics Protection Law of the People’s Republic of China, 19 November 1982. Available online: http://www.npc.gov.cn/zgrdw/wxzl/gongbao/2000-12/06/content_5004416.htm (accessed on 9 December 2022).

- Li, Y. Review and Prospect of the Chinese Revolutionary Memorial Hall (1). Chin. Mus. 1995, 2, 77–87. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y. Review and Prospect of the Chinese Revolutionary Memorial Hall (2). Chin. Mus. 1995, 4, 55–62. [Google Scholar]

- Brief Introduction to the China Old Liberated Area Construction Association. Rural. Pract. Eng. Technol. 1994, 10, 7.

- National Red Tourism Development Planning Outline (2004–2010), 19 December 2004. Available online: https://www.ndrc.gov.cn/fggz/fzzlgh/gjjzxgh/200709/P020191104623060035836.pdf (accessed on 15 May 2023).

- Liu, L.; Wu, X. Legal Protection of Red Tourism Resources. Hunan Soc. Sci. 2005, 5, 61–64. [Google Scholar]

- Research Management Department of the Party History Research Office of the Communist Party of China. Survey of National Important Revolutionary Sites; The Communist Party of China History Publishing House: Beijing, China, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Party History Research Office of Shandong Provincial Committee of the Communist Party of China. Survey of Important Revolutionary Sites in Shandong Province; Shandong People’s Publishing House: Jinan, China, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Party History Research Office of the Jinan Municipal Committee of the Communist Party of China. Overview of Jinan Revolutionary Site; The Communist Party of China History Publishing House: Beijing, China, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- List of the First Batch of Revolutionary Cultural Relics Protection and Utilization Areas, 18 March 2019. Available online: http://www.ncha.gov.cn/art/2019/3/18/art_722_154241.html (accessed on 15 May 2023).

- List of the Second Batch of Revolutionary Cultural Relics Protection and Utilization Areas, 1 June 2020. Available online: http://www.ncha.gov.cn/art/2019/3/18/art_722_154241.html (accessed on 15 May 2023).

- Liu, J.; Han, Y. Discrimination and Analysis of Related Concepts of Red Cultural Heritage. J. Ningbo Vocat. Tech. Coll. 2006, 10, 64–66. [Google Scholar]

- Notice on Submitting the List of Revolutionary Cultural Relics, 19 October 2018. Available online: http://www.gov.cn/xinwen/2018-10/19/content_5332523.htm (accessed on 15 May 2023).

- Qin, A.; Chen, Y. Realistic Value and Overall Protection of the Cultural Relics of the Long March. Theory Contemp. 2017, 7, 9–11. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, H.; Wu, L.; Meng, Q. Summary of Revolutionary Sites in Jilin Province. Herit. World 2021, 8, 25–28. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, G. Research on the Protection and Utilization of Revolutionary Sites in Shandong Province. Master’s Thesis, Zhejiang Sci-Tech University, Hangzhou, China, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, X. Protection and Utilization of Heritage of War of Resistance Against Japan based on Region—Taking Chongqing as an Example. J. West. Hum. Settl. 2013, 4, 24–31. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J. Investigation, Protection and Utilization of Relics of War of Resistance against Japan in Western China; Guangxi Normal University Press: Guilin, China, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Gu, J. Research on the Protection and Utilization of Battlefield Sites. Master’s Thesis, Zhejiang University, Hangzhou, China, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- You, L. Preliminary Study on the Protection of Modern War Memorial Sites in China. Master’s Thesis, Chongqing University, Chongqing, China, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, X.; Yao, L.; Li, Z.; Guo, X. The Evolution and Development Trend of Interpretation of War Heritage. J. West. Hum. Settl. 2017, 2, 57–62. [Google Scholar]

- Pan, Y. Research on the Modern War Heritage from Chinese and Foreign Perspectives. China Anc. City 2020, 1, 32–40. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, Y.; Cai, K.; Zhang, J.; Guo, X. “Event” and Protection Planning of “Revolutionary Sites” Cultural Relics Protection Units—Protection Planning of National Key Cultural Relics Protection Units from the Perspective of Red Tourism Development. Archit. J. 2006, 12, 48–51. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, Y.; Zhou, X.; Wang, T. Composition of Protection Objects and Protection Planning Strategies of Cultural Relics of “Revolutionary Martyrs Memorial Building”—Also on the Protection Model of Battlefield. Archit. J. 2010, S2, 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, Y.; Zhou, X. “Event” and others—Methods on the Protection and Planning of Modern Cultural Relics. Archit. J. 2013, 12, 60–61. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Y. Research on Identification of Modern War Cultural Heritage in China. Master’s Thesis, Chongqing University, Chongqing, China, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Guidelines for the Protection of Cultural Relics and Historic Sites in China. 2015. Available online: http://www.icomoschina.org.cn/uploads/download/20150422100909_download.pdf (accessed on 15 May 2023).

- Wan, S. Analysis on the Value of Red Cultural Resources in Shaanxi. Theor. Guide 2010, 4, 79–81. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, H. Red Heritage: An Effective Resource of Contemporary Ideological and Political Education. J. Tianshui Norm. Univ. 2017, 11, 113–116. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, Z.; Ren, Y.; Qi, S. Strategies for the Development of Red Tourism in Yimeng Mountain Area. J. Shandong Norm. Univ. 2006, 9, 116–119. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, W. The Development and Utilization of Red Cultural Resources in Yimeng Area. Compr. Util. Chin. Resour. 2015, 3, 60–63. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Y. Research on the Development and Utilization of Red Cultural Resources in Yimeng Area. Compr. Util. Chin. Resour. 2015, 7, 39–42. [Google Scholar]

- Zhan, Z.; Cenci, J.; Zhang, J. Frontier of Rural Revitalization in China: A Spatial Analysis of National Rural Tourist Towns. Land 2022, 11, 812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y.; Meng, X.; Cenci, J.; Zhang, J. Spatial Pattern and Formation Mechanism of Rural Tourism Resources in China: Evidence from 1470 National Leisure Villages. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2022, 11, 455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y. Research on Protection and Development Strategy of the Red Heritage of Dabie Mountains based on GIS. In Sharing and Quality, Proceedings of the China Urban Planning Annual Conference in 2018, Hangzhou, China, 24–26 November 2018; China Urban Planning Society, Ed.; China Architecture Publishing & Media Co., Ltd.: Beijing, China, 2018; pp. 1247–1258. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, P. “Full Life-Cycle” Protection of Dabie Mountain Red Cultural Heritage based on GIS. In Digital Technology and Building Life-Cycle, Proceedings of the National Conference on Teaching and Research of Architectural Digital Technology in 2018, Xi’an, China, 15–16 September 2018; China College Architecture Professional Steering Committee, Ed.; China Architecture Publishing & Media Co., Ltd.: Beijing, China, 2018; pp. 119–126. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Xu, D. Creative Design and Planning Strategies of Red Landscape from the Perspective of “Field”—Taking Yimeng Red Landscape as an Example. Shandong Soc. Sci. 2019, 1, 129–135. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, P. Discussion on the Reasons for the Duplication of the Contents of the Revolutionary Memorial Hall and the Ways to Solve the Duplication Problem. In Anthology of Museology, Proceedings of the Founding Conference of Hunan Museum Society and the First Academic Symposium, Hengyang, China, 25–28 June 1982; Hunan Museum Society, Ed.; Hunan Museum Society: Changsha, China, 1982; pp. 37–40. [Google Scholar]

- List of the First Batch of Revolutionary Cultural Relics in Shandong Province, 31 December 2020. Available online: http://whhly.shandong.gov.cn/art/2020/12/31/art_100579_10270202.html?xxgkhide=1 (accessed on 9 December 2022).

- Standards and Guidelines for the Conservation of Historic Places in Canada. 2010. Available online: https://heritagebc.ca/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/Standards-and-Guidelines_Parks-Canada.pdf (accessed on 16 June 2023).

- Canadian Register of Historic Places: Writing Statements of Significance. 2006. Available online: https://www.historicplaces.ca/media/5422/sosguideen.pdf (accessed on 13 June 2023).

- The Historical Data Collection and Research Committee of Shandong Provincial Committee of the Communist Party of China. Jinan Campaign; Shandong People’s Publishing House: Jinan, China, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Committee for Compilation and Review of Historical Data of the Chinese People’s Liberation Army. Jinan Campaign; People’s Liberation Army Publishing House: Beijing, China, 2004; pp. 118–119. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, M. Jinan Southern Mountainous Region Looks Forward to the Development of Red Cultural Tourism. Dazhong Dly. 2022, 1, 12. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, M. Unpublished Work of Interview Record of Xu Yuanchuan, the Former Guard of the East China Field Army of the Chinese People’s Liberation Army; Shandong Jianzhu University: Jinan, China, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, M. Unpublished Work of Interview Record of Xu Ruyi, The Son of Xu Shengzhu, a Volunteer Migrant Worker at the Front Line of Jinan Campaign; Shandong Jianzhu University: Jinan, China, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, M. Unpublished Work of Interview Record of Zhou Xuetian, the Docent of the Command Post Building of Chinese People’s Liberation Army in Jinan Campaign in Yinjiadian Village; Shandong Jianzhu University: Jinan, China, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Fonzo, S. A Documentary and Landscape Analysis of the Buckland Mills Battlefield; Buckland Preservation Society: Gainesville, VA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- The Operational Guidelines for the Implementation of the World Heritage Convention by Unesco, 31 July 2021. Available online: https://whc.unesco.org/archive/opguide77a.pdf (accessed on 26 April 2023).

- Zhu, C. Praise for the Future—Zhu Chengshan’s Research on Peace Studies; Xinhua Publishing House: Beijing, China, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, D. New Cultural History, Micro-History and Popular Culture History—Related Western Achievements and Their Influence on the Study of Chinese History. Mod. Hist. Res. 2009, 1, 127–140. [Google Scholar]

- Licheng County Annals Compilation Committee in Shandong. Licheng County Chronicle; Jinan Press: Jinan, China, 1990; p. 2. [Google Scholar]

- Morris, R. The Archaelogy of Conflict. Conserv. Bull. 2003, 44, 2–3. [Google Scholar]

- Ranjan, A.; Priya, C. Digital Technologies and the Intangible Cultural Heritage of the Rural Destination. In Disruptive Innovation and Emerging Technologies for Business Excellence in the Service Sector; Nadda, V., Tyagi, P., Singh, M., Tyagi, P., Eds.; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2022; pp. 196–218. [Google Scholar]

- Gonçalves, A.R.; Dorsch, L.L.P.; Figueiredo, M. Digital Tourism: An Alternative View on Cultural Intangible Heritage and Sustainability in Tavira, Portugal. Sustainability 2022, 14, 2912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svensson, M. Evolving and Contested Cultural Heritage in China: The Rural Heritage Scape. In Reconsidering Cultural Heritage in East Asia, 1st ed.; Matsuda, A., Mengoni, L., Eds.; Ubiquity Press: London, UK, 2016; pp. 31–46. [Google Scholar]

- ICOFORT Triennial Plan 2019–2022. 2019. Available online: https://www.icofort.org/triennial-plan-icofort (accessed on 7 December 2022).

- Opinions on the Implementation of the Rural Revitalization Strategy, 2 January 2018. Available online: http://www.gov.cn/zhengce/2018-02/04/content_5263807.htm (accessed on 15 May 2023).

- Zhang, J.; Cenci, J.; Becue, V.; Koutra, S. The Overview of the Conservation and Renewal of the Industrial Belgian Heritage as a Vector for Cultural Regeneration. Information 2021, 12, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Phase | Time | Characteristic | Reason | Important Documents |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1949 to mid-1990s | Standardization process for registering and protecting revolutionary heritage | Revolutionary commemoration for politics, publicity, and education purposes | List of National Key Cultural Relics Protection Units (1961, 1982, 1988) |

| 2 | Mid-1990s to end of 2010s | Development of old revolutionary areas and red tourism | Tourism economic development based on rural poverty alleviation | National Red Tourism Development Planning Outline (2004–2010) |

| 3 | End of 2010s to present day | Comprehensive and cross-regional conservation | Overall survey, investigation, and protection of cultural heritage in the new era | List of the First Batch of Revolutionary Cultural Relics Protection and Utilization Areas (2019, 2020) |

| Concept | Time | Relevant Document | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Revolutionary Site and Revolutionary Memorial Building | 1982 | Law of the People’s Republic of China on the Protection of Cultural Relics | Associated with significant modern historical events, revolutionary movements, famous individuals |

| Red Cultural Heritage | 2004 | National Red Tourism Development Plan | Tangible and intangible heritage formed during the revolutionary time led by the CPC |

| Immovable Revolutionary Cultural Relic | 2020 | Notice on Submitting the List of Revolutionary Cultural Relics | Physical remains that reflect China’s modern revolution |

| Tangjiagou Command Post | Yinjiadian Command Post | |

|---|---|---|

| Identity |  Ungraded Immovable Revolutionary Cultural Relic (2021) |  Provincial Cultural Relics Protection Units in Shandong Province (2013) |

| Current situation | Retains the original vernacular architectural character | Undergone improper renovations 4 times |

| Structure | Original vernacular adobe walls and wood truss | Brick wall, wood truss, and girder truss |

| Material | Local limestone shale, adobe, and wood | Common brick and wood |

| Craftsmanship | Traditional adobe wall technology | Imitates the craft of the past |

| Spatial configuration | Vernacular courtyard house southeast gate and southwest circle pattern | Vernacular courtyard house orientated north and south |

| Interior layout | Dailiness | Exhibition |

| Use status | Inhabited before 2021 abandoned from 2021 to present | A private school before 1949 exhibition hall for Jinan Campaign since 1979 |

| Tangjiagou Command Post | Yinjiadian Command Post | |

|---|---|---|

| Reasons for site selection |  In the wooded mountainous area with security and concealment |  Close to the ancient post road and Nantai Hill with convenient transportation |

| Sight line analysis |  Low visual accessibility |  High visual accessibility |

| Military uses | Security and concealment | Military observation |

| customs and traditions | No heritage-based customs and activities | Intermittent visits and commemorative events |

| Pattern 1: Homestay on the Wing-Rooms | Pattern 2: Homestay on the Second Floor | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spatial layout |  |  |  |  | |

| Pattern 1: plan | Pattern 1: axonometric | Pattern 2: plan | Pattern 2: axonomet-ric | ||

| Room layout |  |  |   |  | |

| Single bedroom and courtyard | Double bedroom | Double bedroom | Suite | Shared space | |

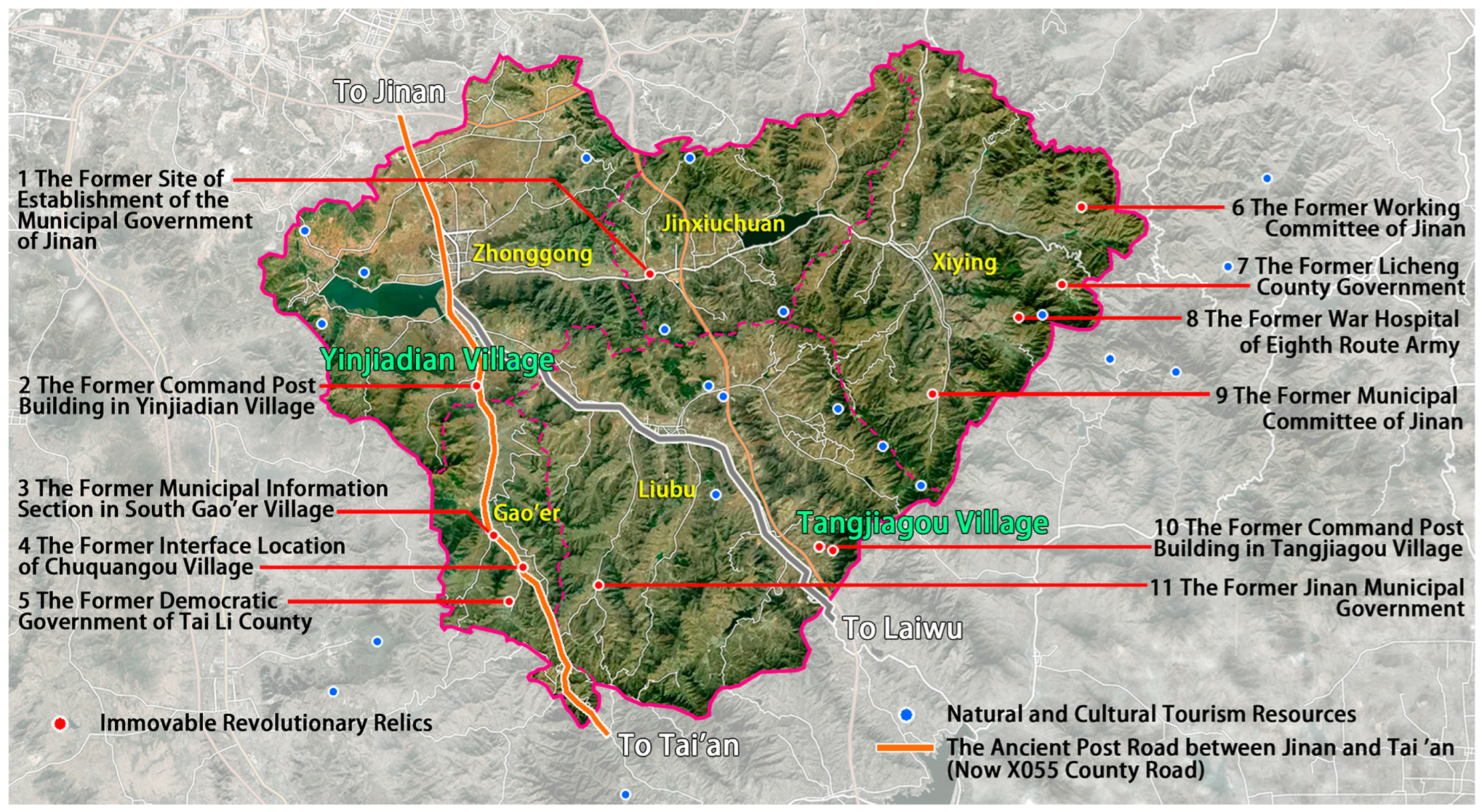

| Name | Identity | Function | Use Condition | Building Condition | Photo | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | The Former Site of Establishment of the Municipal Government of Jinan | Ungraded Immovable Revolutionary Relics | Exhibition | Closed | Recently preserved and renovated |  |

| 2 | The Former Command Post of Jinan Campaign in Yinjiadian Village | Provincial-level Cultural Relic Protection Unit | Exhibition | Closed on weekdays and open on festivals and holidays | Recently preserved and renovated |  |

| 3 | The Former Municipal Information Section in South Gao’er Village | Ungraded Immovable Revolutionary Relics | - | Abandoned | Serious damage |  |

| 4 | The Former Interface Location of Chuquangou Village | Ungraded Immovable Revolutionary Relics | - | Abandoned | Serious damage |  |

| 5 | The Former Democratic Government of Taili County | Ungraded Immovable Revolutionary Relics | Exhibition | Closed on weekdays and open on festivals and holidays | Recently preserved and renovated |  |

| 6 | The Former Working Committee of Jinan | County-level Cultural Relic Protection Unit | - | Abandoned | General damage |  |

| 7 | The Former Licheng County Government | County-level Cultural Relic Protection Unit | Residence | Occasional habitation | General damage |  |

| 8 | The Former War Hospital of Eighth Route Army | County-level Cultural Relic Protection Unit | - | Abandoned | General damage |  |

| 9 | The Former Municipal Committee of Jinan | Ungraded Immovable Revolutionary Relics | Exhibition | Closed on weekdays and open on festivals and holidays | Recently preserved and renovated |  |

| 10 | The Former Command Post of Jinan Campaign in Tangjiagou Village | Ungraded Immovable Revolutionary Relics | - | Abandoned | Serious damage |  |

| 11 | The Former Municipal Government of Jinan | Ungraded Immovable Revolutionary Relics | Exhibition | Open from Monday to Sunday | Recently preserved and renovated |  |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chen, M.; Zhao, B.; Zhao, H.; Jiang, Q.; Zhou, Q.; Tong, H. Character-Defining Elements Comparison and Heritage Regeneration for the Former Command Posts of the Jinan Campaign—A Case of Chinese Rural Revolutionary Heritage. Buildings 2023, 13, 1923. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings13081923

Chen M, Zhao B, Zhao H, Jiang Q, Zhou Q, Tong H. Character-Defining Elements Comparison and Heritage Regeneration for the Former Command Posts of the Jinan Campaign—A Case of Chinese Rural Revolutionary Heritage. Buildings. 2023; 13(8):1923. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings13081923

Chicago/Turabian StyleChen, Meng, Bin Zhao, Hu Zhao, Qiaochu Jiang, Qi Zhou, and Hui Tong. 2023. "Character-Defining Elements Comparison and Heritage Regeneration for the Former Command Posts of the Jinan Campaign—A Case of Chinese Rural Revolutionary Heritage" Buildings 13, no. 8: 1923. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings13081923

APA StyleChen, M., Zhao, B., Zhao, H., Jiang, Q., Zhou, Q., & Tong, H. (2023). Character-Defining Elements Comparison and Heritage Regeneration for the Former Command Posts of the Jinan Campaign—A Case of Chinese Rural Revolutionary Heritage. Buildings, 13(8), 1923. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings13081923