The Creation of “Sacred Place” through the “Sense of Place” of the Daci’en Wooden Buddhist Temple, Xi’an, China

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Wooden Materials

2.2. Sense of Place

2.3. Sacred Space and Buddhist Temples

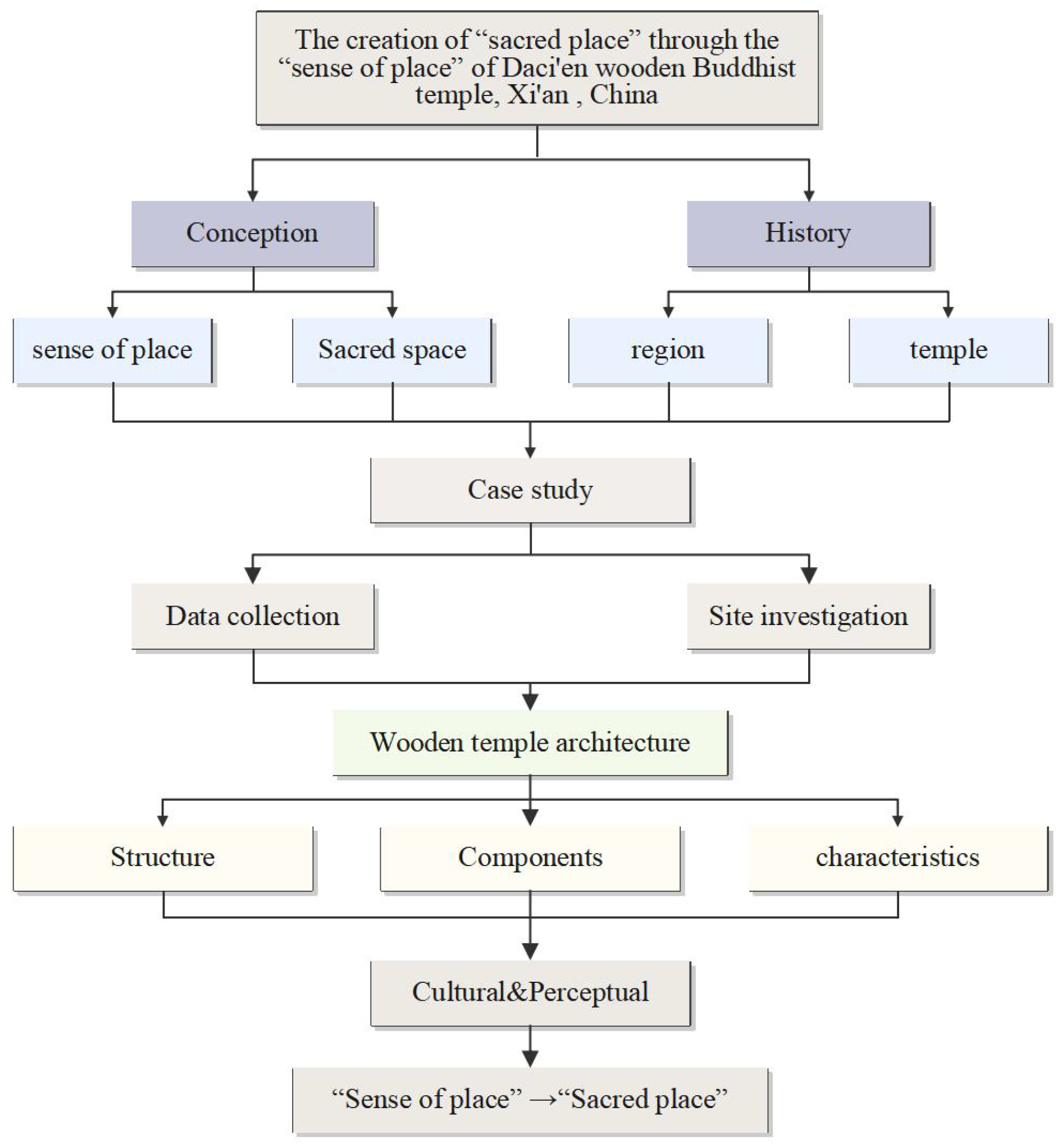

3. Research Methodology

- Through exploring the cultural metaphors and characteristic symbols of wooden architectural structures and components, we show the inheritance of the historical context of architecture and the “sense of place” cultural narrative of architectural heritage and sacred symbols.

- From the perspective of the perceptual characteristics of wooden materials, we explore the wooden expression of Buddhist temples’ sacred atmosphere and culture at the visual, tactile, olfactory, and auditory levels.

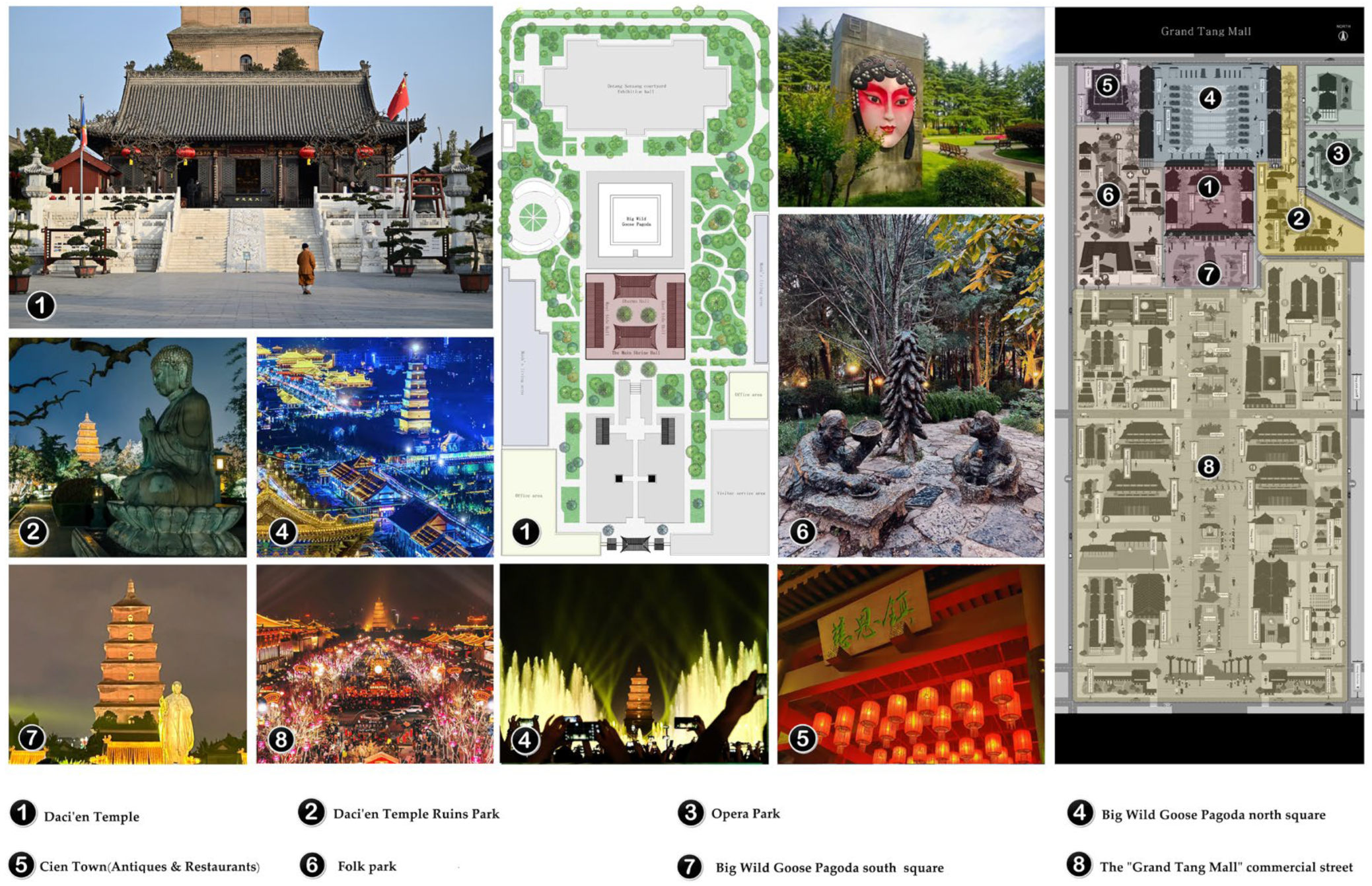

4. Case Study

5. Findings and Discussion

5.1. “Sense of Place” and “Sacred Places” from the Perspective of Architectural Elements

5.1.1. Ritual Culture and Metaphorical Symbols

- (1)

- Roof: The roof reflects the philosophy of harmony between humans and nature and the hierarchy of priority and inferiority. Different styles of roofs in China represent the hierarchy of architecture [53]. According to antiquity, the flying eaves reflect people’s reverence and yearning for “God”, and the roof curve seems to merge with the sky. This form expresses the Chinese people’s pursuit of “transcendence”, “nirvana and rebirth”, and “harmony between man and nature” of Confucianism, Buddhism, and Taoism [54]. The two main halls on the central axis of Daci’en Temple are built with higher-level Xieshan roofs, and the Side Halls on both sides are built with lower-level hanging Xuanshan roofs, as shown in Figure 7. The Xieshan roof purlins face the mountain side of the construction of the “人” sealing plate and are nailed with plum blossom nails, which are a symbol of the Royal Temple class; in ancient times, the ordinary people were called “no nails”, and their architecture was not allowed to use the plum blossom nails decoratively [55]. The unique flower ridge brick carvings of the Guanzhong Plain are used on the Xieshan roof of the Main Shrine Hall to emphasize the regional characteristics of Xi’an. In the “hanging fish” position on the roof of Xieshan, the male and female fishes among the Eight Treasures of Buddhism are used as metaphorical symbols of Buddhism to symbolize the transcendence of time of resurrection, immortality, and regeneration, as well as the free and open-minded wisdom of fish in the water.

- (2)

- Doors and windows: The two main halls on the central axis of Daci’en Temple are decorated with the highest-grade royal “San jiao liu wan” rhombus, and the Side Halls on both sides are decorated with lower-grade “lantern brocade” patterns for the wooden doors and windows, as shown in Figure 8. “San jiao liu wan” usually uses three lattice bars to intersect at one point, and a small metal nail is nailed on this gathering point, thus forming a six-petal rhombus flower at the intersection. This pattern belongs to the highest grade for doors and windows. The “San jiao liu wan” rhombus patterns are complex, connoting heaven and earth and implying the four directions. It symbolizes the intersection of heaven and earth and the birth of all things [56]. The “lantern brocade” features in the East and West Side Halls. A common window pattern in ancient times, it symbolizes brightness and auspiciousness. Like roofs, doors and windows still reflect the hierarchical etiquette system of ancient Chinese architecture and convey the hope of beautiful and auspicious celebrations [57]. As decorative enclosure interfaces, doors and windows not only meet the basic requirements for opening windows but also create subtle changes in light and shadow, satisfying artistic and sacred aesthetic needs. These strictly differentiated ritual-grade decorative components invite people to admire the openness and equality of contemporary life. The extensive use of royal-level architecture in the temple highlights the sacred status of Buddhism. As the Tang Dynasty’s capital, Xi’an witnessed a prosperous and glorious period for Buddhism. Its prosperous economy and developed culture attracted people from all over the world. The high-level decorative components in Daci’en Temple silently tell the story of Xi’an as the national Buddhist center in the Tang Dynasty, like a crown jewel shining for thousands of years.

- (3)

- Beam: The decorative paintings on the beams in the temple are divided into three types: (a) Gilt wood carving of the “Hexi” structure, (b) Pure wood carving of the “Hexi” structure, (c) Xuanzi color painting. The characteristics are shown in Table 2. Daci’en Temple is a thousand-year-old temple. Due to historical changes and wars, it has been rebuilt in every dynasty since the Sui and Tang dynasties. The predecessor of the current Main Hall was rebuilt in the Ming and Qing dynasties [58]. Based on the provisions of Article 14 of the Cultural Relics Protection Law, when repairing, rebuilding, constructing, or relocating key cultural relics, protection units, and other important cultural relics across the country, their original historical appearance must be retained as much as possible to ensure that the restored buildings still conform to their historical characteristics. Therefore, the restored Main Shrine Hall continues to use a Qing-style architectural structure. In order to retain the Daci’en Temple’s splendor, which is attributed to but better than the Tang, the Main Shrine Hall on the central axis was built with pure Indonesian pineapple lattice wood, echoing the magnificent historical culture and architectural colors of the Tang Dynasty. Moreover, the colorful paintings on the architectural beams of the main hall took advantage of wood and carved pure wood colors, replacing the rich colors of Qing-style paintings to highlight the characteristics of Tang Dynasty culture. As the highest-level architecture, the Main Shrine Hall adopts the “hexi” color painting composition form, with wood carvings of golden dragons and Buddhist lecture pictures, and it is gilded. The Dharma Hall is the sub-high level, using dragon patterns with the original color of pure wood. The halls on both sides were painted with sub-lower-level “Xuan zi” colored paintings. In addition, a large number of metaphorical decorative patterns were painted on the beams and “Suifang” at different positions.

5.1.2. Special Performance of Temple Components

- (1)

- The “Tao jian Liang”: The two main halls on the temple’s central axis are decorated with dragon heads in the positions of the “Tao Jianliang”, parts of all government-style wooden structures, and with the wooden Buddha statue in the position of “Baotou Liang”. The structure and position are shown Figure 10. “Tao Jianliang” is used on top of the column head “Dougong”, the beam that carries the house’s eaves. The typical official style for this component is for its structural form to be exposed without any other decoration. Daci’en Temple was decorated with a wooden round dragon head sculpture, which not only has a long-cherished wish to prevent fires and eliminate disasters, according to tradition, but also, more importantly, uses eye-catching wooden dragon head symbols to reflect the ancient cultural background of the divine right of kings and the integration of politics and religion. It shows the interdependence between imperial power politics and the development of Buddhism. Through the material carrier of Buddhist temples, people can recall the Tang Dynasty’s prosperity and the country’s rise and fall a thousand years ago. Daci’en Temple is built around the World Heritage “Big Wild Goose Pagoda”. These aspects of Buddhist temple architecture represent the cultural imprint of Buddhism’s peak development in the Tang Dynasty. According to the records, when Xuanzang returned to the eastern land of Tang, the emperor who founded the reign of Zhenguan, Emperor Taizong, welcomed him into the temple with formal specifications second only to the state banquet [60]. In order to store the retrieved scriptures, Xuanzang personally designed and organized the construction of the “Big Wild Goose Pagoda”, which has stood for thousands of years. From then on, he devoted his life to translating Buddhist scriptures. Therefore, Daci’en Temple became China’s highest school of Buddhist studies during the Tang Dynasty. It is also the ancestral home of the Chinese Buddhist Consciousness-Only Sect [50]. Architecture uses its unique artistic language to continue describing the great history of the past, and these spiritual metaphors expressed through architecture will unconsciously influence people’s emotional experiences. The temple has long been associated with the collective memory of the nation. It is also a glowing statement of the place spirit of Xi’an. It is a “sense of place” and culture preserved by architectural heritage.

- (2)

- The “Baotou Liang”: On the “Baotou Liang” of the Main Shrine Hall, which is the position of the pillar head, the front of the hall is decorated with four “Ran deng Buddhas” carved in the round. The back row is carved with the four Bodhisattvas “Wenshu”, “Puxian”, “Dizang”, and “Guanyin”. At the four corners are “Guan Yu” and “Wei Tuo” Dharma Protector Bodhisattva, and a strong man is used to decorate the “Corner God”. These components are shown in Figure 11. Functionally, the “Baotou Liang” is the interspersed structure between the beams and columns formed by the increased space of large-scale wooden architecture in the form of lifting beams. The “Corner God” is located on top of the corner “Dougong”, supported by the flat disk “Dougong”, and the top of this supports the corner beam [61]. In traditional official-style architecture, the column head of “Baotou Liang” is generally matched with the colorful paintings of “Liang Fang”, and there are also very few important palaces designed with dragon carvings. The decoration of “Baotou Liang” also strictly follows the traditional Chinese etiquette system to reflect the status of the owner of the architecture. The “Baotou Liang” decoration in Daci’en Temple shows the lofty architectural status of the royal Buddhist temple. The exquisite gilt Buddha statues are special decorative symbols, different from ordinary wooden palace buildings. This kind of decoration has a strong religious meaning, and its artistic connotation is more significant than its architectural or structural function. The “Baotou Liang” and “Corner God” in Daci’en Temple construct the supreme wisdom of the Buddhist world. They contain the Buddhist philosophy of mindfulness and perfect practice, touching the sacred perception of worshipers. Moreover, the artistic decoration of the architecture stimulates the religious consciousness and imagination of believers. In addition, some of the wooden statues of Buddha have a unique Western style in terms of tone, a metaphor for the historical event of Xuanzang masters in the West seeking the law and spirit of perseverance and determination, but it also demonstrates China’s national spirit of being compatible with and accepting of foreign cultures and full of confidence in not being assimilated.

5.2. “Sense of Place” and “Sacred Places” from Material Characteristics

6. Conclusions

- In wooden Buddhist temples, the authenticity of materials expresses the exquisite skills and philosophical culture of architecture, and it will also become a key part of the inheritance of architectural heritage in the future.

- Architectural heritage is a physical carrier of a “sense of place” and witness to history. Wooden Buddhist temple architectural structures and components are reflected with locally specific social ethics, religious status, philosophical ideas, and national spirit.

- Wooden Buddhist temples represent a specific historical process and religious culture through their unique architectural language and metaphorical symbolism. This architectural language can awaken people’s religious consciousness, collective memory, local identity, and national self-confidence, all of which contribute to the core meaning of the architectural narrative.

- In wooden Buddhist temples, the natural properties of wooden materials can form multi-dimensional sensory stimulations, including vision, hearing, touch, and smell, gradually evoking spiritual perceptions of comfort, safety, acceptance, and redemption. It is helpful to form a sense of sacred belonging and place attachment.

- The positive impact of wooden Buddhist temples on society is reflected in many aspects, from environmental protection and physical and mental health to cultural inheritance and even social harmony and stability. As a spiritual “sacred place”, such temples can provide spiritual comfort and stress relief, thereby reducing social conflict, and can enhance community cohesion and cultural identity, contributing to the overall well-being and sustainable development of society.

- In this study, the creation of “sacred place” through the “sense of place” in Buddhist temple architecture is found to be based on the advantages of wooden materials. In developing and protecting Buddhist temple heritage, other architectural elements must also be considered to sufficiently maintain the local context and enhance the emotional experience of the sacred space.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhang, H. Illustration of Ancient Chinese Architecture: Fifty Years’ Notes of an Architectural Historian; Times Culture Publishing: Jilin, China, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Watson, S.; Wells, K. Spaces of nostalgia: The hollowing out of a London market. Soc. Cult. Geogr. 2005, 6, 17–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X. Consideration on the urban spatial morphology and operation of Taiyuan, China from the religious building perspective. Front. Archit. Res. 2022, 11, 239–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caan, S. Rethinking Design and Interiors: Human Beings in the Built Environment; Hachette UK: Paris, France, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Tostões, A. Modern built heritage conservation policies: How to keep authenticity and emotion in the age of digital culture. Built Herit. 2018, 2, 17–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harun, S.N. Heritage building conservation in Malaysia: Experience and challenges. Procedia Eng. 2011, 20, 41–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rong, W.; Bahauddin, A. Heritage and Rehabilitation Strategies for Confucian Courtyard Architecture: A Case Study in Liaocheng, China. Buildings 2023, 13, 599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X. A brief analysis of the ideological reasons for the continuous inheritance of the wooden structure system of ancient Chinese buildings. Huazhong Archit. 2005, 6, 16–17+22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Leeuw, G. Phänomenologie der Religion; J.C.B. Mohr Publishing: Groningen, The Netherlands, 1933. [Google Scholar]

- Mendonça, J.T. Sacred Contemporary Year LVII, Number 166, January–April 2022. Available online: https://www.torrossa.com/en/resources/an/5310230 (accessed on 1 January 2023).

- Daelemans, B. Healing Space: The Synaesthetic Quality of Church Architecture. Religions 2020, 11, 635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, D. Research on Buddhist Temple Architecture in Xi’an Area. Ph.D. Thesis, Tianjin University, Tianjin, China, 2013. Available online: https://kns.cnki.net/kcms2/article/abstract?v=ipUboLYjcOXcYFtcKVSA4c08aT-K7x_B0UnI4uqj5HViBlmb_KEWMnBDFWbgMvBBNDow4uV4pmFvNto-0FKP-mboFtB4pq5Y4qCQfhjGMZxnwcaFdE2X9dK_93WtFMUZ89lNdE9L7BeHdo7o7Zre7g==&uniplatform=NZKPT&language=CHS (accessed on 1 January 2023).

- Overvliet, K.E.; Soto-Faraco, S. I can’t believe this isn’t wood! An investigation in the perception of naturalness. Acta Psychol. 2011, 136, 95–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J. Analysis of Semiotic Thinking of Materials. Ph.D. Thesis, Tianjin University, Tianjin, China, 2011. Available online: https://kns.cnki.net/kcms2/article/abstract?v=ipUboLYjcOUl9pGgM4vOFZGzmxYYqssU-r9In5jeYzMPHzz9DC_NtyWKmTjuqnEAp5e03eNmtwIkSaurfceub_APFuonOp6Vu9NTMtVuVvIP3CIGK3Qn-xXvffa8RR6y2fNtF3uOH_5YMENeVSerrA==&uniplatform=NZKPT&language=CHS (accessed on 1 July 2023).

- Hadjiphilippou, P. The Contribution of the Five Human Senses Towards the Perception of Space; Department of Architecture, University of Nicosia: Nicosia, Cyprus, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, S. Contemporary Expressions of Traditional Building Material Expressions. Master’s Thesis, Xi’an University of Architecture and Technology, Xi’an, China, 2012. Available online: https://kns.cnki.net/kcms2/article/abstract?v=ipUboLYjcOWS0BIcGvkFnaYF7ppicdQpCdvDnTycLv74qG9kl4v22mHgwFo6WXE9KwVKA5xs-JH61rptosmjSpX8qv9cN12Ml2JTqmi3SN1j0i3pjxTxJW12PqlPljwPhvwSy19lzlOFTCcFgAoyyg==&uniplatform=NZKPT&language=CHS (accessed on 20 July 2023).

- Stone, S. UnDoing Buildings: Adaptive Reuse and Cultural Memory; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, Z.; Zhen, Z. Traditional expression of wooden architecture under modern technology. Huazhong Archit. 2008, 5, 60–63. Available online: https://kns.cnki.net/kcms2/article/abstract?v=tc18asgQl7R6FnjSkAqHHqpXBoTAnIBY5xa82bK8_lQqB52EscU7i4qSqkWvTrRig4uJJo270SrVWZfo8AlfEKbLDwkxl_FmVlMwZuip2wcPamp5MLnAwZi3vr0wXDqMuxt0Wq6LNj8=&uniplatform=NZKPT&language=CHS (accessed on 8 October 2023).

- Zheng, Y. Analysis on the application and technology of the five elements in Chinese ancient buildings. For. Chem. Rev. 2022, 10, 1260–1268. [Google Scholar]

- Lewicka, M. Place attachment: How far have we come in the last 40 years? J. Environ. Psychol. 2011, 31, 207–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norberg-Schulz, C. Genius loci: Towards a phenomenology of architecture (1979). Hist. Cities Issues Urban Conserv. 2019, 8, 31. [Google Scholar]

- Mazumdar, S.; Mazumdar, S.; Docuyanan, F.; McLaughlin, C.M. Creating a sense of place: The Vietnamese-Americans and Little Saigon. J. Environ. Psychol. 2000, 20, 319–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Counted, V. The role of spirituality in promoting sense of place among foreigners of African background in The Netherlands. Ecopsychology 2019, 11, 101–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tumimbang, T.N.; Van Rate, J. Pura Kaja Segara Nirmala. Analogi Semiotik. J. Arsit. DASENG 2018, 7, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Mazumdar, S.; Mazumdar, S. Religion and place attachment: A study of sacred places. J. Environ. Psychol. 2004, 24, 385–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scannell, L.; Williams, E.; Gifford, R.; Sarich, C. Parallels between interpersonal and place attachment: An update. In Place Attachment; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2020; pp. 45–60. [Google Scholar]

- Scannell, L.; Gifford, R. Place attachment enhances psychological need satisfaction. Environ. Behav. 2017, 49, 359–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahauddin, A.; Prihatmanti, R. ‘Sense of Place’ on Sacred Cultural and Architectural Heritage: St. Peter’s Church of Melaka. Interiority 2022, 5, 53–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Z.; Huang, M. Cultural maladjustment, organizational reengineering and rural construction—Starting from Liang Shuming’s “Rural Construction Theory”. J. China Agric. Univ. Soc. Sci. Ed. 2021, 38, 83–96. [Google Scholar]

- Lian, C. Research on Regional Design of Contemporary Residential Buildings in Xi’an. Master’s Thesis, Xi’an University of Architecture and Technology, Xi’an, China, 2015. Available online: https://kns.cnki.net/kcms2/article/abstract?v=ipUboLYjcOWIT2usN3rvfORU9rT208rzQuCSSNrPNX9F3mxjd_FXTQjbkOde50RaEBXnCIsdKk1-EmuhzkUDxMbBbiGMhGOofn2Pqt1qGDMgB3Y9vE89Rv-cJT3nRyEeGHn2R2VYITdTGra-qIPROw==&uniplatform=NZKPT&language=CHS (accessed on 20 August 2023).

- Sinclair, B.R. Spirituality and the City. In The Routledge International Handbook of Spirituality in Society and the Professions; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2019; pp. 93–102. [Google Scholar]

- Lois González, R.C.; Lopez, L. Liminality wanted. Liminal landscapes and literary spaces: The way of St. James. Tour. Geogr. 2020, 22, 433–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, Z.; Song, Y. The sacred power of beauty: Examining the perceptual effect of buddhist symbols on happiness and life satisfaction in China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 2551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vásquez, M.A. More than Belief: A Materialist Theory of Religion; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Ryff, C.D. Spirituality and well-being: Theory, science, and the nature connection. Religions 2021, 12, 914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhen, Q. Decoration and Color of Religious Buildings and Its Application in Lhasa Region of Tibet. Master’s Thesis, Chongqing University, Chongqing, China, 2003. Available online: https://kns.cnki.net/kcms2/article/abstract?v=tc18asgQl7SgLgVOVZo7EV_QjJ0PoOJx7A9z0DuEX4Eqdb4Y2QmPfZNGrhxiZ2RwkGKEepVX2jMvOm2QZRCfiro4fYwND2U4j7AwFEJtSMrpzSuMkIskJVZyyt_oPCg8OAdiN-eyqL0LBZx5fLmFVw==&uniplatform=NZKPT&language=CHS (accessed on 2 August 2023).

- Wu, H. Telling the Beijing Story of the Chineseization of Religion with a “Small Cut” in Architecture. Beijing Daily, 3 September 2018; 002. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, J.; Zhang, X.; Zhi, Y. Research on the Revitalization and Utilization of Ancient Buildings at Qinglian Temple in Jincheng. City Build. 2023, 20, 1–4+8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, G.; Yuan, C.; Cao, J. Research on the color evolution of Chinese historical buildings. Constr. Technol. 2023, 2, 50–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, Z.; Li, X. A preliminary study on the layout of early Buddhist temples in North Bactria—Also discussing the connection with ancient Buddhist temples in the Western Regions. Dunhuang Stud. 2023, 1, 46–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asadi, S. Taj Mahal is the Crystallization of Iranian Architecture and a Symbol of God’s Throne on Earth. Acad. Res. Community Publ. 2023, 1, 34–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rod-Ari, M. Thailand: The Symbolic Center of the Theravada Buddhist World; Center for Southeast Asian Studies, University of Hawai’i at Manoa: Honolulu, HI, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Gamache, G. Spiritual Space or Theme Park? A Case of Postmodern Simulated Experience. KEMANUSIAAN Asian J. Humanit. 2017, 24, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, X. Research on the architectural form of temples in Tang Dynasty. Pop. Lit. Art 2018, 3, 93–95. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, B.; Sun, W.; Cui, Q. The first round of Xi’an City Chronicle The beginning and end of compilation (Part 1). Shaanxi Hist. Rec. 2006, 2, 23–30. [Google Scholar]

- Song, L. Xi’an Ancient Temple Big Wild Goose Pagoda. Chin. Newsp. Ind. 2023, 4, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Che, X. Humanistic Buddhism and Charity. Buddh. Dharma Sound 2014, 10, 24–27. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, X.; Tian, P. A Series of Books on the Eight Major Sects of Chinese Han Buddhism and Their Ancestral Court; Xi’an University of Electronic Science and Technology Press: Xi’an, China, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, W.; Zhou, M. Chang’an Buddhist Temple. New West 2014, 9, 18–20. [Google Scholar]

- Jing, P. The Historical Evolution and Cultural Utilization of Daci’en Temple. For. Steles Forum 2019, 4, 128–136. Available online: https://kns.cnki.net/kcms2/article/abstract?v=xBNwvqFr00I-N9UcJr0V4cLQ3ijztae2RrOZyakEiIume3FkC5TarxvhLkB_1Qaup5clk9_pnfi7opaWkjLU_Q3Rrj6_MiCfXdIP3I0Ge_znBbescn5YNz8aPLX-sCDeZZejVWHsflA=&uniplatform=NZKPT&language=CHS (accessed on 20 December 2022).

- Li, M. A review of Xuanzang research from the perspective of archeology. Relig. Stud. 2019, 4, 139–143. Available online: https://kns.cnki.net/kcms2/article/abstract?v=tc18asgQl7R1GpKszA3mD-Bfhz669ddxqMZuBN7rW_AUfYLKGXEJzilfxLbfqcbeRZzEgpPINHVBp8VeCWOp4rfff0Nexq9O_rCT8YWxp_0Te-qyjZq1KPofU6XEbZ1K467IJ7rC_xCL6wA5Lx6tFQ==&uniplatform=NZKPT&language=CHS (accessed on 2 December 2023).

- Xie, S. Research on the Rise and Fall of Buddhism in the Tang Dynasty. Ph.D. Thesis, Henan University, Zhengzhou, China, 2014. Available online: https://kns.cnki.net/kcms2/article/abstract?v=_AqZbjAWWJRSdJKrJRkmf1K5cuch-NXOLtGqqseYwNVBV_R8tViMvk-m8aF6HDzWxSXg9j5h5kenWRR8mj0wC80-68oMFVwhokX9vHa1OjuWEa7hgbpBElmjVieWvTNxidRp4H7P8_MFLkVot7UHqA==&uniplatform=NZKPT&language=CHS (accessed on 20 July 2023).

- Wang, Q. Research on Decorative Art and Cultural Connotation in Ancient Chinese Architecture. Master’s Thesis, Jilin University, Changchun, China, 2012. Available online: https://kns.cnki.net/kcms2/article/abstract?v=_AqZbjAWWJS2o7TaMwAxQafLuddgaFgbnjVr3fqw1qgU0v2KqHz0YU4g5QNw0xK6vh3Md2RkUJBwlwPq1IYGSUTGbz0xdfyZogY_EUVmgZdy-nX1jgL_DHGJUCc82a1zWXYhTV_HRKMryVQl4-S8XQ==&uniplatform=NZKPT&language=CHS (accessed on 20 July 2023).

- Liu, Y.; Li, X. A brief analysis of the roof art of Chinese classical architecture. Art Des. 2018, 2, 63–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F. On the decorative characteristics of ancient Chinese buildings. J. Northwest. Inst. Archit. Eng. 2002, 4, 37–40. Available online: https://kns.cnki.net/kcms2/article/abstract?v=_AqZbjAWWJQH3JRWeT02-_32JM0ZPjRpMXNaeuSrHFPyCWVNvfvm8MsU0Fw4OlY_gwx5VdKtUFdL0CgOyFM0qmd0FGB0qI7aV-CmeQPr8f4JZZLzoPxxX8Y1ONuv4w1pajN4sncjZCU=&uniplatform=NZKPT&language=CHS (accessed on 6 July 2023).

- Feng, X.; Cheng, K.; Wang, Y. Parametric study on geometric patterns of door and window lattices in ancient Chinese buildings. China Resid. Facil. 2022, 6, 47–49. Available online: https://kns.cnki.net/kcms2/article/abstract?v=_AqZbjAWWJQQ5YcWEG-wZhiblMqELrsfVPpp33wxtP_d96x4P5SVqOMymVi6YjDhbY4qAIygkfaMFq5wjPv4UK2J8jO0obfsC0MV3FaOJqw4gxLSyzaJGvHbxAGc2Z_wFX9YRO2FNAVbxdRkLjDKkw==&uniplatform=NZKPT&language=CHS (accessed on 20 August 2023).

- Ou, X. An analysis of the decorative art of ancient Chinese buildings. Mod. Decor. 2014, 4, 41–42. Available online: https://kns.cnki.net/kcms2/article/abstract?v=_AqZbjAWWJQ-41a0ziVeDcNc01Leu_9UHCxH2s4rHwlPyLTGjLtHVkLnkfkJ4cgslOgCQ6AU0O6HV5IkB-uvkTr3Y0mmDG9NBqQOYujwQUcVy-UnDBgyluiL93bEyJ-J_lZ6ghj0Qmc=&uniplatform=NZKPT&language=CHS (accessed on 1 August 2022).

- Chen, F. Chronicles of Daci’en Temple; Sanqin Publishing House: Xi’an, China, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y. On the integrated thinking method and its application in architectural creation. J. Hunan Univ. 2004, 1, 108–112. Available online: https://kns.cnki.net/kcms2/article/abstract?v=xBNwvqFr00JfOjBfKoq1VWM02xWQNVA9ZYXmSrWkgOezpcjVhgG3tgvJQy7Pjx-MfqOi4o-TDjqtyDUQuJ6FcqhDeKNdwzlJn-kZwyaswXlg5CU10g3vXSbm3Wv8omOF8-04sARJQxM=&uniplatform=NZKPT&language=CHS (accessed on 2 December 2023).

- Qian, N. Cultural Ambassador Xuanzang. Lit. Hist. Spring Autumn Period 2021, 12, 64. Available online: https://kns.cnki.net/kcms2/article/abstract?v=xBNwvqFr00IpD3utd7KspO5Q0J7gifLD25z0XetEhxhBn1HNK_OjnaVujlgqHMRYsECIN51iDCZvUulAPHQ4VPGSZ65b978Wzr9Q8VC_04mSMxEtGOucwOFiC1ns8gCvFKkAilfx_kRGHK0edoT-7g==&uniplatform=NZKPT&language=CHS (accessed on 1 September 2023).

- Cong, X. Research on the construction of large timber as mortise and tenon joints in Qing Dynasty architecture. Shanxi Archit. 2012, 38, 10–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, T.; Zheng, X. Understanding how multi-sensory spatial experience influences atmosphere, affective city image and behavioural intention. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2021, 89, 106595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Li, J.; Wang, M. Analysis of visual environmental characteristics of wood surfaceⅠ. The relationship between visual physical quantities and visual psychological quantities on the surface of wood. Wood Ind. 1995, 2, 14–17+30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Kuang, Y.; Zhu, S.; Burgert, I.; Keplinger, T.; Gong, A.; Li, T.; Berglund, L.; Eichhorn, S.J.; Hu, L. Structure–property–function relationships of natural and engineered wood. Nat. Rev. Mater. 2020, 5, 642–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, H.; Graça, J.; Rodrigues, J.C. Wood chemistry in relation to quality. Wood Qual. Its Biol. Basis 2003, 3, 53–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pacini, G. Arboreal attachments: Interacting with trees in early nineteenth-century France. Configurations 2016, 24, 173–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cloke, P.; Jones, O. Tree Cultures: The Place of Trees and Trees in Their Place; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Asdrubali, F.; Ferracuti, B.; Lombardi, L.; Guattari, C.; Evangelisti, L.; Grazieschi, G. A review of structural, thermo-physical, acoustical, and environmental properties of wooden materials for building applications. Build. Environ. 2017, 114, 307–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; He, L.; Liang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, H.; Zhou, J.; Cui, H.; Li, M.; Miao, Y.; Liu, Z. Modulating the Acoustic Vibration Performance of Wood by Introducing a Periodic Annular Groove Structure. Forests 2023, 14, 2360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pallasmaa, J. The Eyes of the Skin: Architecture and the Senses; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Shepherd, G.M. Smell images and the flavour system in the human brain. Nature 2006, 444, 316–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mencagli, M.; Nieri, M. The Secret Therapy of Trees: Harness the Healing Energy of Forest Bathing and Natural Landscapes; Rodale Books: Emmaus, PA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Engen, T. The Perception of Odors; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Canniford, R.; Riach, K.; Hill, T. Nosenography: How smell constitutes meaning, identity and temporal experience in spatial assemblages. Mark. Theory 2018, 18, 234–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.; Chung, H.-J.; Kim, K.-H. A Study on the Haptic-Visual Phenomena in Peter Zumthor’s Architecture. J. Archit. Inst. Korea Plan. Des. 2015, 31, 193–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Selection Criteria | DCE | DXS | GR | WL | JF |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Located in the main urban area | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ |

| Temple is a Han-style royal temple and is relatively large in scale | √ | √ | √ | √ | |

| Temple has a rich historical and cultural background in the Sui and Tang dynasties | √ | √ | √ | ||

| One of the three major translation centers | √ | √ | √ | ||

| The main hall is made of wood | √ | √ | |||

| One of the eight major ancestral temples | √ | √ | |||

| The temple contains a World Heritage Site | √ | ||||

| Selection result | √ |

| Style | Characteristic | Rank | Photo |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gilt, dragon pattern, Buddhist lecture pictures | Highest level Royal main architecture |   |

| No gilding, dragon pattern | Sub-high level Royal main architecture |  |

| “Xuanzi” pattern, no dragon pattern | Sub-lower level Royal secondary architecture (Side Halls) |  |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zou, M.; Bahauddin, A. The Creation of “Sacred Place” through the “Sense of Place” of the Daci’en Wooden Buddhist Temple, Xi’an, China. Buildings 2024, 14, 481. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings14020481

Zou M, Bahauddin A. The Creation of “Sacred Place” through the “Sense of Place” of the Daci’en Wooden Buddhist Temple, Xi’an, China. Buildings. 2024; 14(2):481. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings14020481

Chicago/Turabian StyleZou, Minglan, and Azizi Bahauddin. 2024. "The Creation of “Sacred Place” through the “Sense of Place” of the Daci’en Wooden Buddhist Temple, Xi’an, China" Buildings 14, no. 2: 481. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings14020481

APA StyleZou, M., & Bahauddin, A. (2024). The Creation of “Sacred Place” through the “Sense of Place” of the Daci’en Wooden Buddhist Temple, Xi’an, China. Buildings, 14(2), 481. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings14020481