Abstract

Memorial museums serve as a record of the past and provide evidence of the past; moreover, they are a place for remembering the past and healing the present. In particular, their architectural language, such as movement through space, is actively involved in fostering public memory that implies a shared understanding of the past. However, it is hardly explained how public memory is configured in memorial museums, and how it is experienced by the act of moving around within the places. This study, hence, aims to investigate the configurational relationship between public memory and movement through space throughout an in-depth case study using visibility graph analysis as one of space syntax techniques, and movement tracking analysis. By examining the War Memorial of Korea, which is dedicated to commemorate sacrifices during the Korean War in memorial halls and chronologically describes wars in the Korean Peninsula, it was found out that a memorial museum works in a bifurcated way. Its spatial layout leads to a locally focused experience along a strongly structured commemorative sequence. On the contrary, it allows globally dispersed spatial experiences to take place along the integration core, suggesting both specific and wide-ranging themes and contents throughout their various exhibitions. Therefore, the locally focused paths elicit a commemorative experience by adding depth, whereas the globally dispersed paths bring about informal itineraries that start from their integration cores. It concludes that spatial configurations, as a non-verbal language, plays a role in transmitting the public memory.

1. Introduction

Memorial museums operate in a bifurcated way. As truth-telling mechanisms, the main functions of memorial museums are “to serve as a record of the past and to reveal and preserve the truth about what happened” (p. 163, [1]). Similar to other museums such as history museums, which collect documents and artifacts; natural history museums, which collect and preserve specimens; and art museums, which store authentic works of art; memorial museums aim to preserve the past and its material remains. On the one hand, it said that remains serve as ‘evidence’ for what happened in the past. On the other hand, memorial museums are also a place of repair, remembrance, and healing of the present. In particular, they provide collective or public memories by highlighting the sufferings, sacrifices, and losses undergone by various actors, fomenting an ethic of “never again”. From this bifurcation, memorial museums are not only institutions that preserve material culture and remains of the past, but also symbolic places that shed light on the truth regarding the experiences of the present and future generations.

According to Blair et al., public memory is related to the present, but this relationship is highly dependent on context, available resources, representational choices, and framings via various techné [2]. Because public memory is “embodied in living societies”, it narrates or constructs ‘shared identities’ [3]. However, it should be noted that public memory is strongly associated with place or space. This is because a particular place is “an object of attention” and serves as “a marker of collective identity” (p. 25, [1]), which suggests that memory and place are both rhetorical. Memorial museums serve as memory places, and thus play an extensive role in shaping, articulating, and embracing public memory not only through means of architectural form, but also by particular ways of deploying spaces. Moreover, memorial museums are significant places for enunciating social ideas and highlighting the identities of communities and nations as repositories of knowledge and value, educating, refining, or eliciting social commitments.

Based upon the aforementioned aspects, Broudehoux and Cheli examined several memorial spaces devoted to mass crimes such as slavery, genocide, forced internment, and disappearances to find out the way architecture attempts to “communicate past events or experiences too harsh to otherwise describe” (p. 161, [4]). The authors studied leading international memorial museums by selecting the architectural elements that would elicit public memory; they identified that ‘siting’, ‘form’, ‘movement through space’, and ‘void’ were actively involved in generating meaning. For instance, said authors concluded the siting itself delineated what happened in the past on account of its geographical location, topography, and local context. In addition, as regards architectural form, various styles such as minimalism, abstraction, and anti-aestheticism, acting as non-representational media, deliver the horrors, fears, or victimhood of traumatic past events. Furthermore, the act of moving through space leads to the embodied experience undergone by visitors. Finally, voids are used substantially because they can represent the absence of invisible victims, loss, and despair.

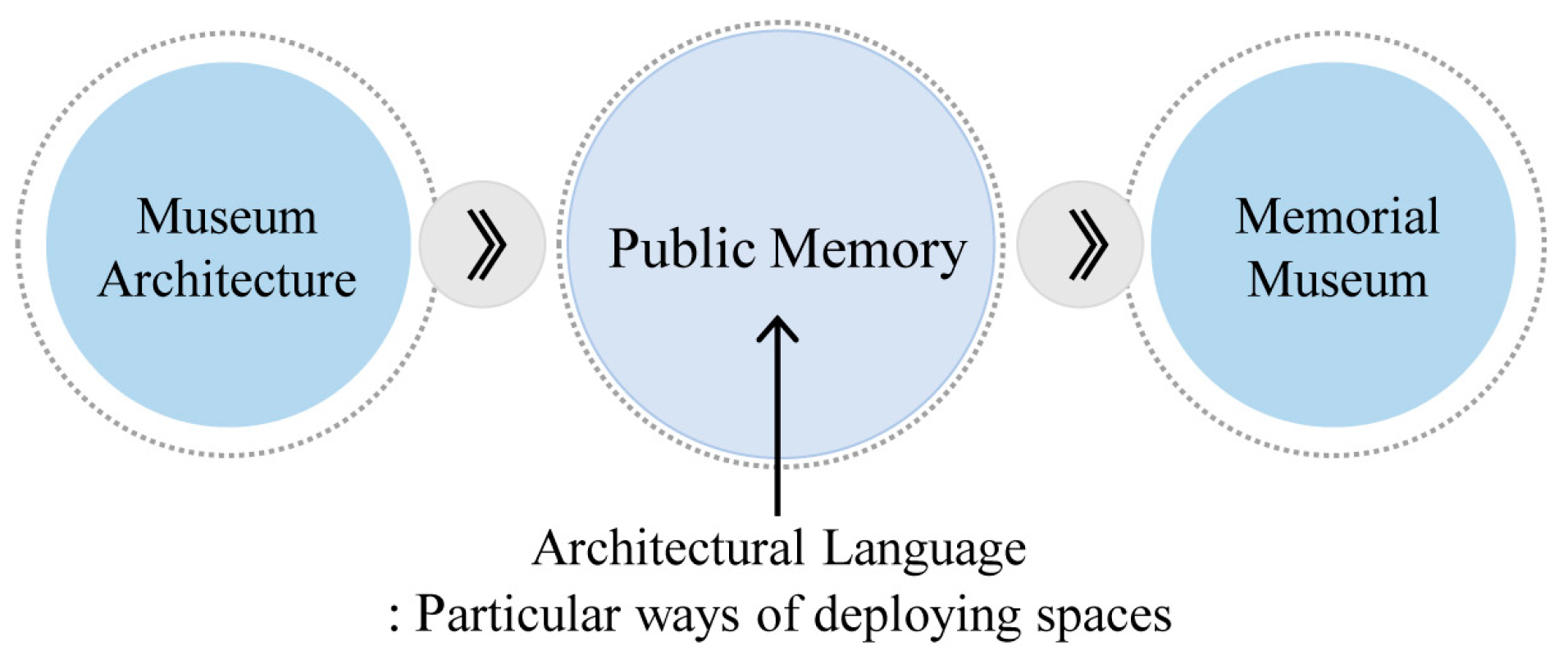

In particular, the concept of movement through space is the most significant architectural phenomenon in museum studies because it is strongly related to the understanding of disciplinary knowledge or underlying principles (Figure 1). Therefore, spatial experience in museums is influenced by ways of moving around, such as strong chronological sequences or matrix movement forms [5,6,7,8].

Figure 1.

Conceptual relationship among architecture, public memory, and spatial configuration.

Despite having been thoroughly discussed in fields such as the social sciences, museum studies, and built environments, the mechanisms through which memorial museums work are not clear, particularly when serving to heal the present. In other words, the fundamental question regarding the way public memory, which is shaped by architectural language, is delineated, and how visitors interact with it throughout the very activity of moving around the different spaces in memorial museums, has not yet been answered. Is there an intention behind spatial layouts? If so, how does the spatial configuration affect the spatial experience of the visitor? Hence, this study aims to identify the configurational relationships between public memory and architectural language through the in-depth study of a memorial museum and explore the degree to which public memory is directly related to spatial experience.

Architecture serves as a ‘non-verbal language’, and it can translate abstract meanings into material forms by using architectural language. Particularly, memorial museums embody implicit meanings. However, it is not clear how visitors would experience these intentions by the act of moving around. Therefore, this study aims to provide a comprehensive perspective in understanding how memorial museums work by investigate the process of delineating public memory using space syntax, and the visitor’s experience by movement tracking analysis.

To explain the relationship between architecture and public memory, we conducted a literature review encompassing the different symbolisms of public memory sites, memorial museum studies by memory scholars, and architectural attributes in the space syntax community. We selected the War Memorial of Korea as the case study, the historical background and important criteria of which have been described, and examined the primary functions and aims for erecting this architectural design. The following analysis will demonstrate how this design works from both commemorative and configurational viewpoints using the space syntax technique; it will also use movement-tracking data to identify the way architectural language affects the spatial experience of the visitor. This study concludes with a consideration of the substantial roles architectural language plays in embodying public memory as a memorial place, preserving and exhibiting material remains in a museum.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Public Memory Space

According to Blair et al., a shared understanding of the past is recognized as memory; this, however, is conceived in many different forms such as collective, social, popular, cultural, and public memories [2]. Despite its multiplicity, the concept of memory is embedded in “constituted audiences” with common interests, with profound political implications. Since remembering the past takes place in the form of public memory, it has been concluded that public memory is strongly related to the present because the main function of memory is “not to preserve the past, but to adapt it so as to enrich and manipulate the present” (p. 210, [9]).

The relationship between the past and the present, as Blair et al. argue, is highly “variable and depends on context, available rhetorical resources, representational choices, and the framing provided by various techné” [2]. Public memory is invented in a sense by means of “selectivity” and/or “creativity” in order to represent interests or needs of the present, to establish continuity with the past, or to highlight the difference of the present from the past. In addition, public memory narrates “shared identities”, and offers a “sense of belonging” to society. As a result, it imbues “affect” for “particular audiences in particular situations”. However, public memory is partially and frequently contested because of its “dense set of layered discourses, events, objects, and practices” (Ibid). This is why it relies on material or symbolic supports such as languages, ritual performances, communication techniques, objects, and places.

Landsberg pointed out that public memory has been transformed into a new form of memory. This is because public memory is no longer trans-historical but is “historically and culturally specific”. In other words, “it has meant different things to people and cultures at different times and has been instrumentalized in the service of diverse cultural practices” (p. 3, [10]). From this perspective, she suggests a notion of “prosthetic memory”, emerging at “the interface” between a person and a historical narrative about the past by, for instance, reading a book, and also at “an experiential site” by visiting a movie theater or museum. These mass-mediated representations provide “the occasion for individual spectators to suture themselves into history” (p. 15, [10]). Therefore, memories are not authentic or natural but are derived from engaging with mediated representations, and they can be interchangeable and exchangeable into different forms in an age of mass culture.

Dickinson et al. go further on discussing the role of ‘place’ in the understanding of public memory because places such as museums, preservation sites, battlefields, or memorials lead to memory formation in the audiences. In other words, it is itself an “object of attention” not only on account of “its status as a place”, but also “its self-nomination as a site of significant memory of and for a collective”. In addition, the place is an “object of desire” due to “its claim to represent, inspire, instruct, remind, admonish, exemplify, and/or offer the opportunity for affiliation and public identification” (pp. 25–26, [2]). Memory places have a specific “place-ness”, they produce specific relationships between the present and past, which lead people to experience this relationship and traverse it. In particular, memory places contain objects, installations, memorabilia, and historic artifacts, and they “prescribe” paths encompassing entry, traversal, and exit. Therefore, memory places are carefully designed; in particular, spatial layout is strongly correlated to the way in which visitors interact with the relationship as a whole.

Here, it should be noted that public memory arises in many different forms: when considered as a monument, it “tends to use less explanation” but “signifies victory” so that it always leads to remembrance. On the contrary, when considered as a memorial, it “refers to the life or lives sacrificed for a particular set of values” because it “tends to emphasize texts or lists of the dead”, so that it embodies grief, loss, tribute, and obligation (p. 120, [11]). As a public memory place, a memorial demands specific contents such as the Vietnam Veterans Memorial in Washington, D.C., where the names of individuals have been etched onto the black granite wall to remember those who were lost in the war. Therefore, public memory form refers not to a monument, but to a memorial.

In summary, public memory is a shared understanding of the past. It is not trans-historical but rather effective for certain people at a particular time. Public memory places attain cultural importance and become part of the experience from the perspective of departure. A specific relationship between the past and present is encountered in these memory places. Therefore, places play a role not only in articulating shared understandings, but also by spatially embodying affect from a particular perspective.

2.2. Memorial Architecture

Memory scholars have focused on the public role of memory; thus, they have examined how objects carry and embody public memory [2,3,9]. In addition, recent studies have attempted to identify the spatialization of public memory from spatial, architectural, and territorial perspectives, and to understand the transformative role of memorial architecture and design in our society. However, the contribution of memorial architecture to constructing “shared meaning” and articulating “collective memory” is still unknown.

From these comprehensive deficits, Broudehoux and Cheli considered memorial architecture as examples of memory places, and investigated how architecture would act as a “non-verbal language” suitable not only to communicate past events or experiences like slavery, genocide, forced internment, and disappearances in European Cities, but also to translate these memories into architectural forms and spatial configurations [4]. To answer these questions, they conducted several case studies of the following memorial sites: the Memorial to the Martyrs of Deportation in Paris, opened in 1962; the Memorial to the Abolition of Slavery in Nantes, opened in 2012; the Budapest Holocaust Memorial Center, opened in 2004; the Jewish Museum in Berlin, opened in 1999; and the Paris’ Shoah Memorial, opened in 2005.

By studying these cases, they contend that siting, form, material, and path are primarily concerned with generating meaning. For instance, siting itself contributes to generating meaning on account of its specific context and credibility. Access to the site is also important because it leads visitors to think of “what they are about to experience”, and awakens them to “what lies inside”. Explicitly, memorial architecture is characterized by “minimalism” and “abstraction”. This peculiar tendency is derived from the idea that minimalism leads visitors to “see more” beyond the visual imagery [4]. It is widely accepted that “aestheticization” could reduce the value of public memory or undermine its historical significance, and as a result, an abstract form is strongly brought into architecture to symbolize all types of human mass tragedies. Similar to abstract forms, the materials used in memorial architecture are regarded as an effective means of reinforcing the symbolic content of public memory. Sometimes, rough and cold concrete is applied to memorial architecture to highlight oppressive and harsh situations, whereas polished, reflective materials are intentionally employed to bring the present to the past. The path is a key attribute in the spatial layout of memorials such that the act of traversing memorial spaces is “part of embodied experience that visitors partake in” (p. 168, [4]). A globally prescribed path across the layout is suggested to deliver museum narratives by selecting or sequencing events, selecting a particular sequence to be followed by stepping upward or downward, or by moving through a thin or sparsely lit passageway. Movement through spaces plays a significant role not only in representing public memory, but also in transmitting it to the visitors.

These comprehensive studies shed light on the role of memorial spaces in eliciting public memory of mass atrocities and the positive effects of architectural language on collective healing and historic reparations. However, these studies did not investigate the performance of the architecture itself. In other words, we should examine the architectural mechanism used for constructing public memory and the way by which the visitors experience it. Therefore, this is one of the main objectives of this study.

3. Case and Research Methodologies

3.1. Case

Memorial museums are understood not only as truth-telling institutions but also as symbolic places that depict suffering, sacrifices, and losses. Memorial museums reflect a new approach to remembering and educating people about what happened in the past. To look into these theoretical and empirical questions, we selected the War Memorial of Korea (“WMoK”) as our case study.

The WMoK was opened in 1994 in the Yongsan district. Originally, it aimed to systematically collect and preserve materials and remnants of the Korean War for clarifying how this war started and to describe the shear amount of sacrifice by the UN veterans and Koreans. However, one of the challenging issues at the time of its opening was defining the role of a memorial museum. There were controversial debates such as whether it would serve as a memorial museum only for the Korean War or as an extensive museum that would include the history of the struggles against foreign forces. Through many talks and discussions, it was decided that this memorial museum should showcase the entire history of the war that had developed in Korea by then. As a comprehensive war museum, it fosters commemoration of Korean and UN losses, the collection and research of materials and remains, and the teaching of a “never again” ethic and contributes to the peaceful unification of the country, as the War has not ended. On account of these multivocal characteristics, the WMoK was selected as an appropriate case for this study.

We need to determine whether a single case study is sufficient for exploring how public memory is represented or perceived. The reason for conducting a case study was that identifying appropriate cases in Korea is difficult. Of course, there are several memorial museums and spaces, but most of them are focused on particular people who dedicated their lives to the liberation and independence of the country, or specific subjects such as the Korean War abductees or the peasant revolution. This is why their floor area is relatively small; therefore, the whole spatial structure is easy to understand at once. They also focus on narrating events rather than collecting and preserving materials and remains. In contrast, the WMoK is sufficiently large to secure and exhibit artifacts and remains about all the wars that took place in Korea (i.e., the original role of the museum), serving as a storytelling building and a healing place for the present and future generations (i.e., for commemorating sacrifices and losses). Therefore, the WMoK, which acts as a comprehensive museum, is a suitable case for this study.

3.2. Research Methodologies

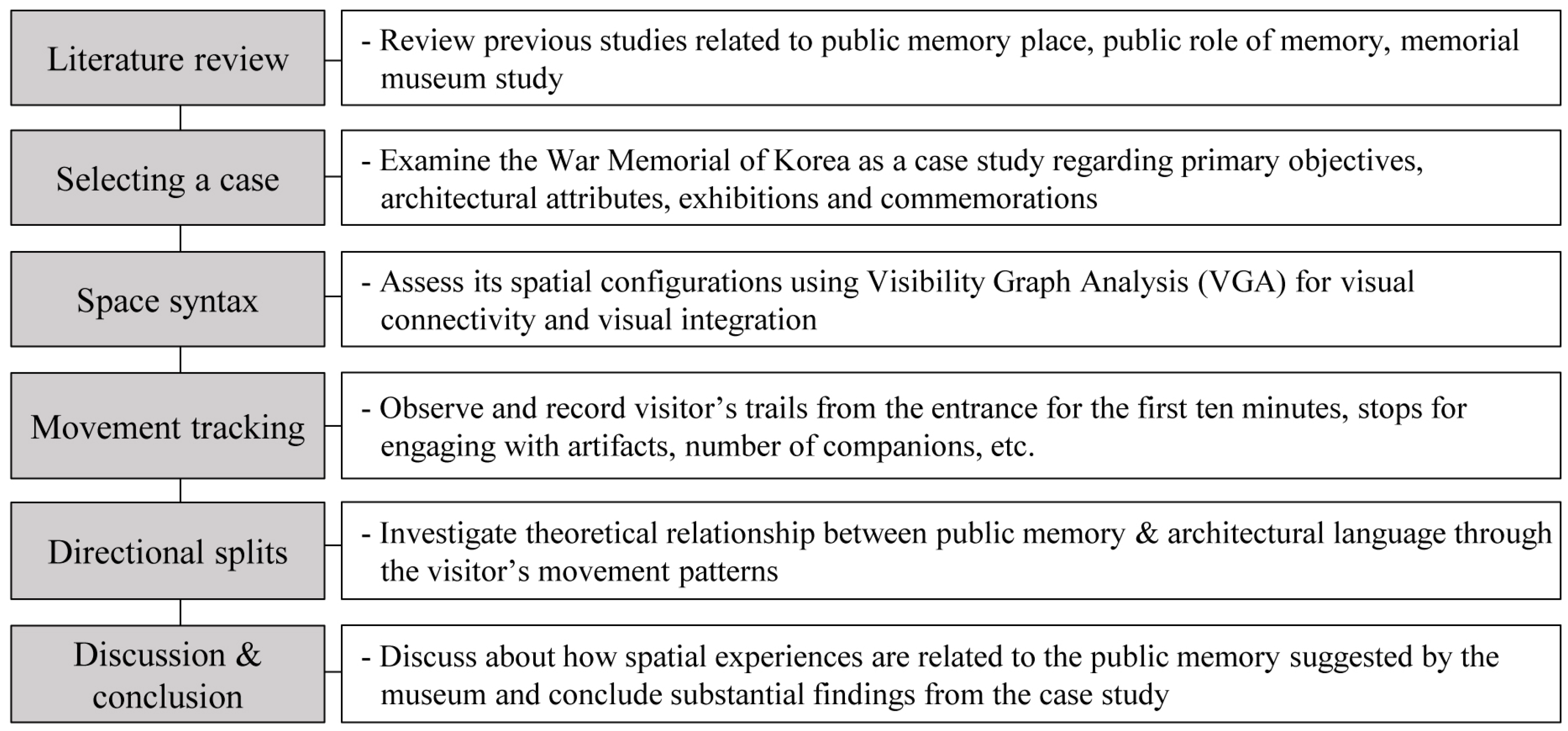

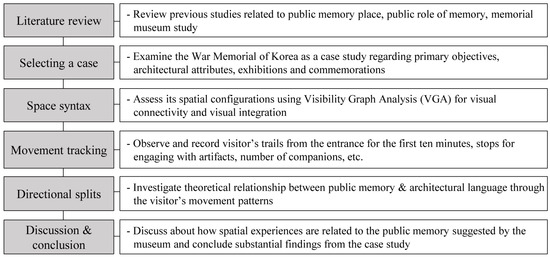

The case was analyzed by the following methodologies: a literature review about architectural approaches, design strategies, exhibition contents, and intents; the use of space syntax to identify the configurational features of its spatial layout in terms of connectivity at a local level, integration at a global level, and intelligibility in terms of the degree to which the whole spatial structure can be easily understood; movement tracking, which was conducted to investigate how visitors move across the building; and exploration of all information and data, to determine whether there is a configurational relationship between architectural language and public memory (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Flow chart of research methods.

Regarding space syntax methodology, there are four ways of looking into space layout: convex space, axial line, isovist, and visibility graph. First, space can be understood as a convex space where no line is drawn between any two points; in particular, this space forces people to interact with each other. Second, buildings are represented as a set of axial lines by drawing the longest lines across convex spaces, which are closely related to the idea of moving through spaces [12,13]. Isovist, in contrast, refers to the set of all points visible from a certain vantage point in space; it is used as a theoretical method to quantify the amount of information that can be obtained or, conversely, to assess how easily the vantage point can be read by the surroundings [14]. However, assessing the entire spatial structure of buildings is difficult because their geometric properties (e.g., isovist area, perimeter, or shape) are purely local viewpoint features. To overcome this problem, visibility graph analysis (“VGA”) has been suggested by the space syntax community. The VGA is a method of measuring all the isovist properties of every viewpoint divided by a grid system [15].

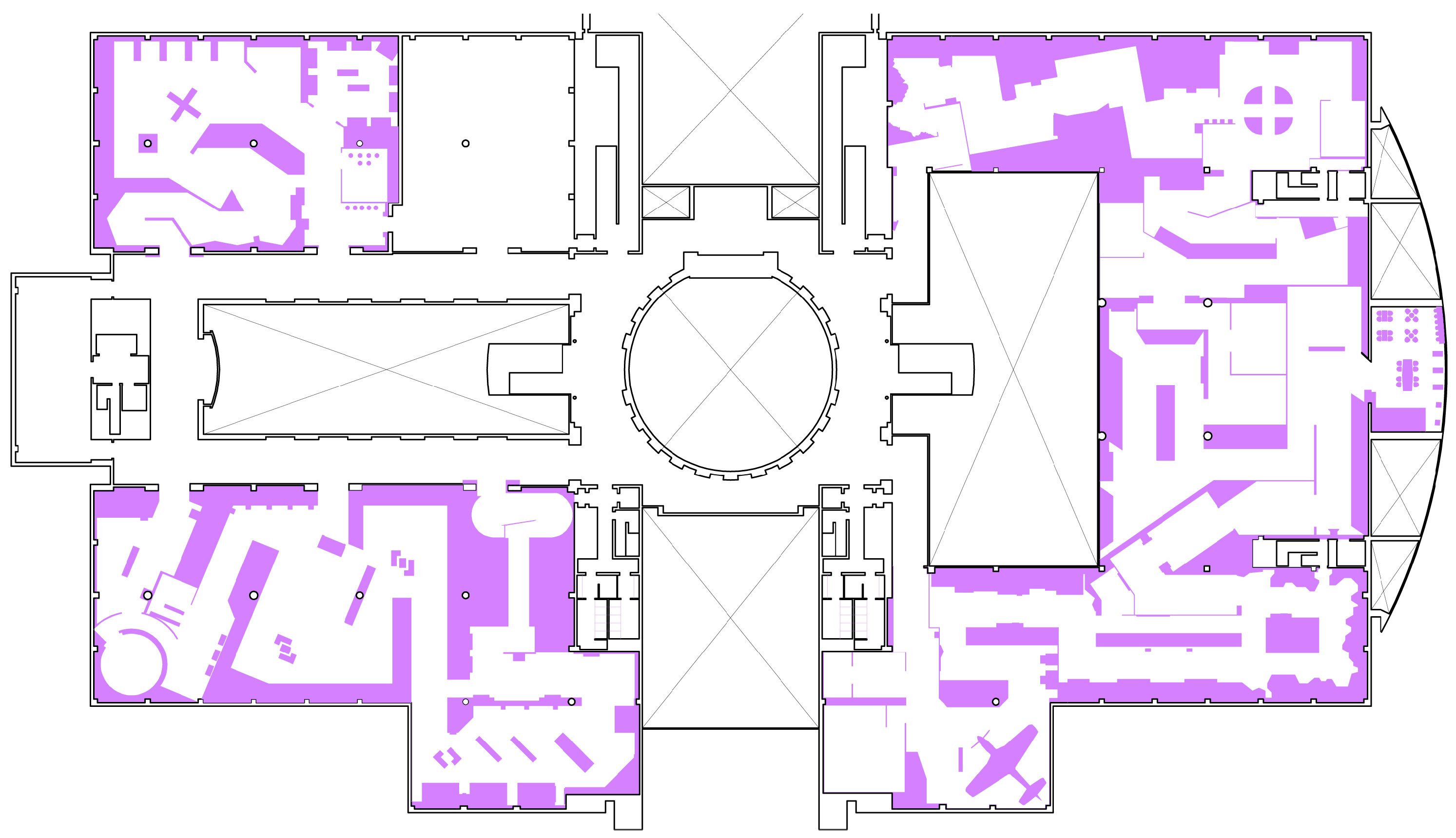

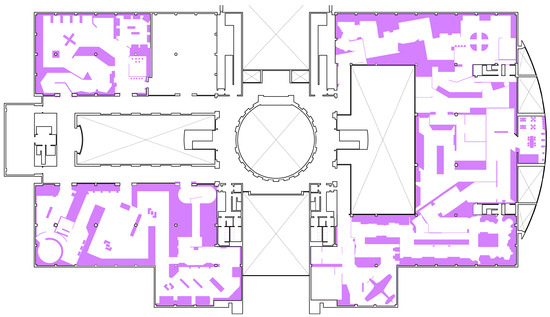

These syntactical techniques are quite useful in examining spatial layouts and their relationships with various social phenomena, but VGA is used to explore the configurational features of the case. Generally, museums consist of a small number of spaces for exhibitions, corridors, and ancillary facilities, such as cafes, restaurants, or museum shops. However, museum exhibitions are often fragmented or divided into several sections or areas to convey expert knowledge and curatorial intent to visitors. For instance, let us look at the exhibition layouts of the WMoK on the third floor (Figure 3): we can identify that the exhibition layout aims at conveying disciplinary knowledge through “interaction with the labels” as well as “the pre-defined sequences” [16,17,18]. Therefore, analyzing the spatial layout of museum architecture using both convex space and axial line techniques is quite difficult; rather, VGA is an appropriate method for studying museums. For VGA analysis, the depthmap X program (depthmapX-0.8.0_win64version) was used.

Figure 3.

Exhibition layouts of the WMoK on the third floor (purple represents the layout of exhibitions).

Regarding movement tracking, the subjects were followed for the first 10 min from the main entrance without being told in order to avoid intentional movements or behaviors during their journey. Previous studies have shown that this short timescale covers well-distributed movement patterns across buildings, such as those conducted in the Tate Britain, the Natural History Museum, and the Science Museum in London [18,19]. Subjects were randomly selected at the entry point, and 55 subjects were unobtrusively followed. When following subjects, demographic profiles (e.g., foreigners, natives, the number of companions, and the number of children), paths, and stops for engaging with objects were recorded on a sheet of floor plan.

A directional split technique was used to determine identical movement patterns from the movement-tracking data. This technique aims to understand the position to which the visitors travel from the entrance to the interior of the building. In particular, it is an effective method to explore how visitors move in response to the architectural intent of a memorial museum. In addition, this allows us to examine the degree to which the directional split results correspond to syntactical properties, particularly to the integration core. ANOVA and a box and whisker plot were performed to find out how these movement patterns are significantly distinctive from one another.

4. Understanding the War Memorial of Korea

4.1. Formation of the WMoK and Its Primary Objectives

The need for a War Memorial for the Korean War was raised in the 1960s, but the actual plan was accelerated by the will of the then-President Roh Tae-Woo after the Seoul Olympics in 1988. A task force team at the Ministry of Defense was promptly organized, and the team suggested three substantial meanings for constructing the war memorial: first, the Koreans finally got space to commemorate those who gave their lives to Korea; second, this space facilitates the preservation, management, research, exhibition, and education of war-related historical materials and relics; and finally, through this we can learn how miserable war can be and how precious peace is to us (pp. 16–17, [20]).

Based on this concern and willingness, the War Memorial of Korea Association Act was enacted and promulgated in 1989. According to this act, the primary role of the association is to construct the WMoK and operate it successfully, develop and maintain a national collection of historical materials related to the Korean War and major historical wars, assist curatorial activities, continue research on Korean military war history, educate visitors, publicize commemorative activities, and projects in both print and electronic formats.

Within the association, a number of advisory committees had been formed on areas such as military history, literacy, architecture, exhibition, policy, and operation, all of which addressed the issue of where to erect this museum, what to exhibit, how to emphasize the importance of ‘better safe than sorry’, and in what way wars have affected our daily lives from different viewpoints such as politics, economy, culture, and society. Based on the committee’s talks, a preliminary plan for the WMok was suggested; it comprised two parts, a memorial monument and memorial architecture, which must be preserved permanently without any alterations. The memorial monument stands out as an urban landmark. The memorial architecture is further composed of two sections: a memorial hall that aims to remember the sacrifices and commemorates the national spirit, and the exhibition hall, which focuses on the history of war from the prehistoric period to the Korean War via the Three States era, Joseon Dynasty, Korean Empire era, and Japanese Colonial period. In particular, exhibitions should include the participation of the United Nations (“UN”) and its impact on the world. Beyond the wars in Korea, the exhibition extends to the dispatch of the Republic of Korea (“ROK”) forces to Vietnam and highlights the development of the ROK armed forces. Moreover, the committees mentioned additional facilities such as research centers, archives, management offices, food and beverages, parking lots, gardens, and outdoor exhibitions.

As mentioned above, the primary objectives of this memorial museum are to facilitate commemoration, exhibition, research, and education. In particular, commemoration is directly related to the sacrifice and loss that occurred during the Korean War. This means that the remembering is specified as an event that resulted in over seven hundred thousand casualties in the Korean army and UN forces, whereas the other programs of the exhibition, research, and education expand to the entire history of Korea. Therefore, it is concluded that this memorial museum represents the Korean War.

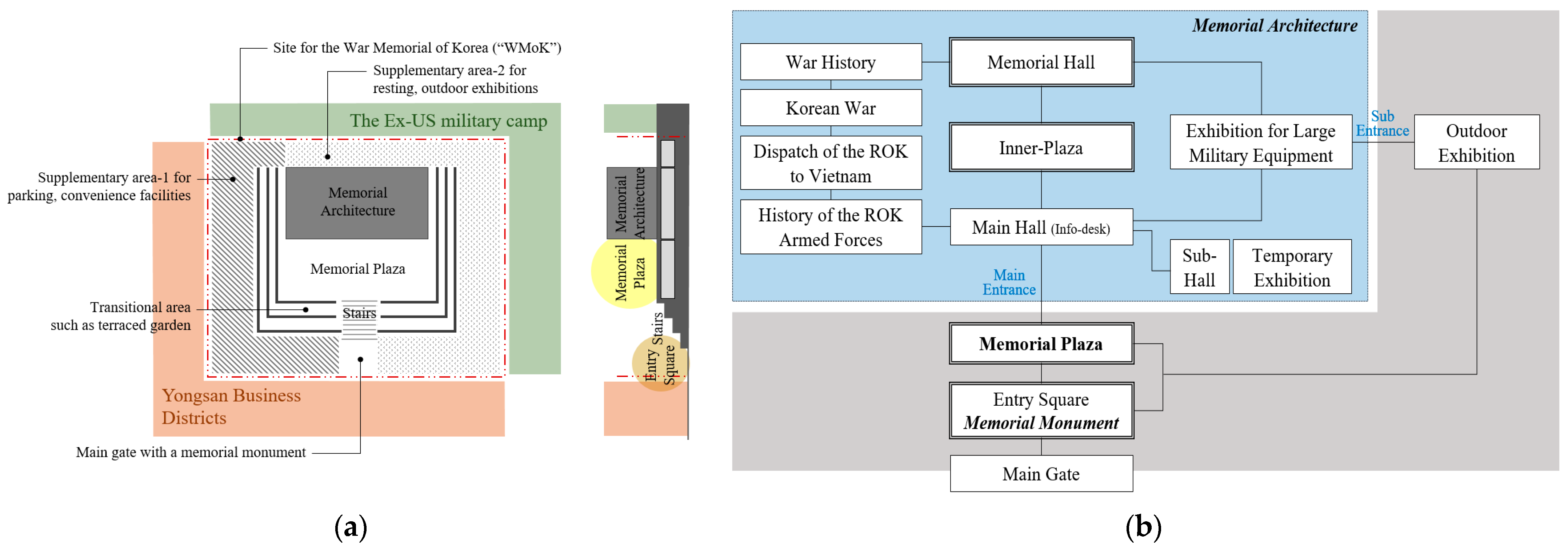

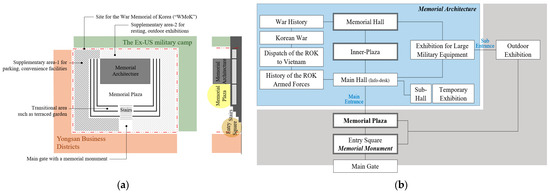

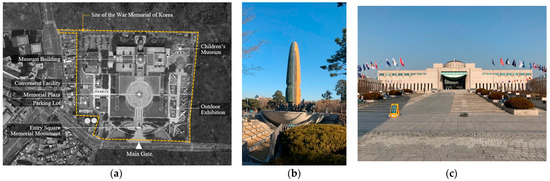

The site is located at the boundary between the Yongsan business district and a former US military base (which was relocated to Pyungtaek). In other words, they are surrounded by distinctive urban conditions. Therefore, weakening or redefining these urban disconnections is an important criteria. For this, the site is intentionally divided into two areas (Figure 4): the area adjacent to the former US military base for resting and outdoor exhibitions, and another area next to the Yongsan business district for parking or convenient facilities. The main gate is placed on the southern side of the site, and a memorial monument is placed at the gate to stand out as one of the most meaningful landmarks and one of the places to remember. Moreover, the area for memorial architecture was elevated by employing terraced gardens and stairs to create an independent territory compared to other areas. This means that architecture is relatively significant because it is the place to remember the tragedy of the war and commemorate the sacrifices of relatives. Therefore, the site gradually moves upward from the gate to the memorial architecture via gardens and stairs.

Figure 4.

Diagrams of the preliminary concept of the WMoK: (a) conceptual diagram of the site plan; (b) primary programs and their relationships.

Three different paths were suggested for the layout of space and exhibitions. In Figure 5, the central path begins at the main entrance of the memorial architecture and leads directly to the Memorial Hall via the Inner Plaza. Therefore, it can be said that this is a commemorative path. The other paths also begin at the Main Hall, but they are bifurcated either at the Main Hall or Memorial Hall on both sides: the left side enables experiencing wars from pre-historical times to the present through the ‘War History’, ‘Korean War’, ‘Dispatch of the ROK to Vietnam’, and ‘History of the ROK Armed Forces’ exhibitions; the right side leads to the ‘Large Military Equipment’ exhibition hall. Hence, they can be considered as disciplinary paths. Interestingly, the central path is strongly structured in the proposed spatial layout; this means that it is part of the journey from the main gate to the Memorial Hall via the Entry Square with the memorial monument, Memorial Plaza, and Inner Plaza. In other words, it is placed at the apex for remembering and commemorating.

Figure 5.

The War Memorial of Korea: (a) site plan; (b) memorial monument; (c) memorial architecture.

4.2. Architectural Attributes

The actual building of the WMoK was completed in 1994, based on the preliminary conception of spatial experiences and exhibition layouts (Figure 4). Similar to the schematic design, visitors move along the main axis, which spans from the main gate to the Memorial Hall on the second floor via the entry square, the memorial monument, and the memorial plaza. Outdoor exhibitions and children’s museums are located on the right side, and convenient facilities, such as cafes, restaurants, and restrooms, are on the left side of the main axis. The exterior design and façade are characterized by firmness, stability, and massiveness that result from the use of granite as construction material, geometric composition, and symmetric shape.

One of the remarkable architectural attributes of the WMoK is its four-way frontability. This means that the elevations respond to the surrounding conditions; for example, the front elevation is strongly related to the urban context, memorial plaza, and entry square, whereas the others are related to Yongsan Park on the eastern and northern sides and the low-density land use on the western side. This four-way frontality emphasizes its monumental characteristics and makes visitors recognize its commemorative role in the Korean War history within urban context.

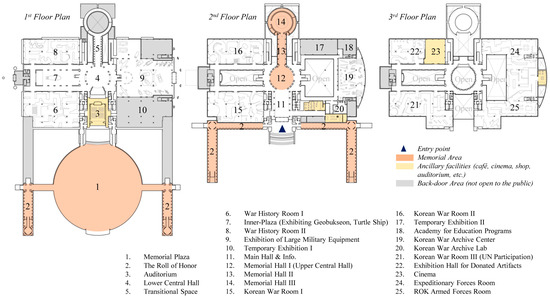

4.3. Exhibitions and Commemorations

On the first floor in Figure 6, there are three permanent exhibitions, ‘War History Room I’, ‘War History Room II’, and ‘Exhibition of Large Military Equipment’; a temporary exhibition; an auditorium; a lower central hall; and a transitional space. These exhibitions focus on delivering the overall war history in a chronological manner: starting with tools in the prehistoric period, and moving on to a series of pivotal battles, clashes, wars, and foreign invasions. In particular, the inner plaza between the two war history rooms exhibits Geobukseon, that had been played the most important role in Joseon Dynasty.

Figure 6.

Floor plans in 2022: (left) first floor plan; (center) second floor plan at the entry level; (right) third floor plan.

On the second floor as an entry level, there are two permanent exhibitions, such as ‘Korean War Room I’ and ‘Korean War Room II’; a series of memorial halls, ‘Memorial Hall I’, ‘Memorial Hall II’, and ‘Memorial Hall III’; two archives, ‘Korean War Archive Lab’ and ‘Korean War Archive Center’; two temporary exhibition halls; and other facilities like a café, a museum shop, and an info-desk. Also, there are two voids placed on the both sides of the building. These exhibitions comprise the consecutive events of the Korean War, which explain the political situations; the presence of governments with different systems on the Korean Peninsula; and how the Korean War began and how the world reacted to the invasion. Particularly, the memorial halls, starting from the main hall, are used as a place to honor and commemorative the outstanding achievements of those who devoted themselves to the country in this war with a book of the Korean Army and the UN Forces Casualty Lists. This commemorative trail extends to the transitional space on the first floor. From an aspect of public memory, this commemorative space, therefore, represents the relationship between the past and the present, and it acts as a specific place-ness in this memorial museum.

With a cinema, the third floor has a total of four exhibitions, such as ‘Korean War Room III’, ‘Exhibition Hall for Donated Artifacts’, ‘Expeditionary Forces Room’, and ‘ROK Armed Forces Room’; and a cinema. This floor is especially designed for telling variant stories which were directly or indirectly involved in the war and its aftermath. Also, it represents significant supports of the ROK Forces to the world.

In summary, the first floor represents the history of war took placed in Korea Peninsula; the second floor exclusively speaks of the Korean War with conveying facts and commemorating sacrifices or losses; and the third floor tells us about the peace by describing what the UN had done during the Korean War, and how the ROK army has developed it and dedicated it to the world.

5. Syntactic Analysis and Movement Tracking

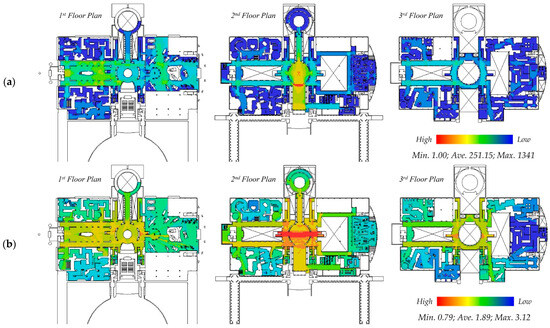

5.1. Syntactic Analysis

Figure 7 depicts the syntactical results at two different scales. In the visual connectivity at a local scale, we can recognize there is a strong pattern in terms of spatial connectedness. That is, the main hall and memory halls colored in red and yellow have a higher number of direct connections; in particular, the main hall is the most connected space in this connectivity analysis. Similarly, the gathering spaces on other floors (e.g., the Central Hall, Inner Plaza, Large Military Equipment Exhibition on the first floor, and corridors along the voids on the third floor) are relatively well connected. In contrast, there are fewer exhibition spaces across the building. From this, we can understand that gathering spaces, such as the Main Hall, Inner plaza, and corridors, locally construct a number of viewpoints that offer an opportunity for social interactions on account of their greater total number of direct connections to other spaces. In particular, direct connections are formed in distinctive ways. On the first floor, the three large spaces of the Inner Plaza, the Lower Central Hall, and the exhibition of Large Military Equipment are well connected, so that it is hard to escape the longitudinal axis along the east–west direction. However, on the second floor, the main hall and memory halls (the most commemorative experience in this building) are closely articulated so that there is a strong visual connection from the front to the deepest space of the building. Hence, it can be said that visual connectivity works distinctively: it constructs the commemorative sequence of spaces with adding depths, and conversely, it constitutes the spectacular sequence of spaces with the compressed representation of war.

Figure 7.

Syntactical results of VGAs: (a) the visual connectivity at a local level; (b) the visual integration at a global level.

Looking at the visual integration graph, it is clear that the Memory Hall I is the most integrated place, and this high integration value extends to the stairs, thus leading to the vertical opening of the voids. This integration core leads to two important voids: one representing the Korean War and the other representing Geobukseon, due to its innovative design, achievement, and contribution to protecting the country.

Regarding visual connectivity and the visual integration, there is a dynamic change at different levels: at a local level, spaces suggest distinctive sequences that focus on commemoration and spectacle, whereas on a global level, spaces enable us to understand the whole spatial structure. In particular, the memory hall, formed in a rotunda, works in different ways: it leads to a commemorative sequence by maximizing depths, and serves as a perambulation space by minimizing depth.

5.2. Movement Tracking Analysis

Movement tracking was conducted in February 2023. Subjects were randomly selected at the entry point, and 55 subjects were unobtrusively followed for the first 10 min without being told that they were being observed, to avoid any intentional movement or activity.

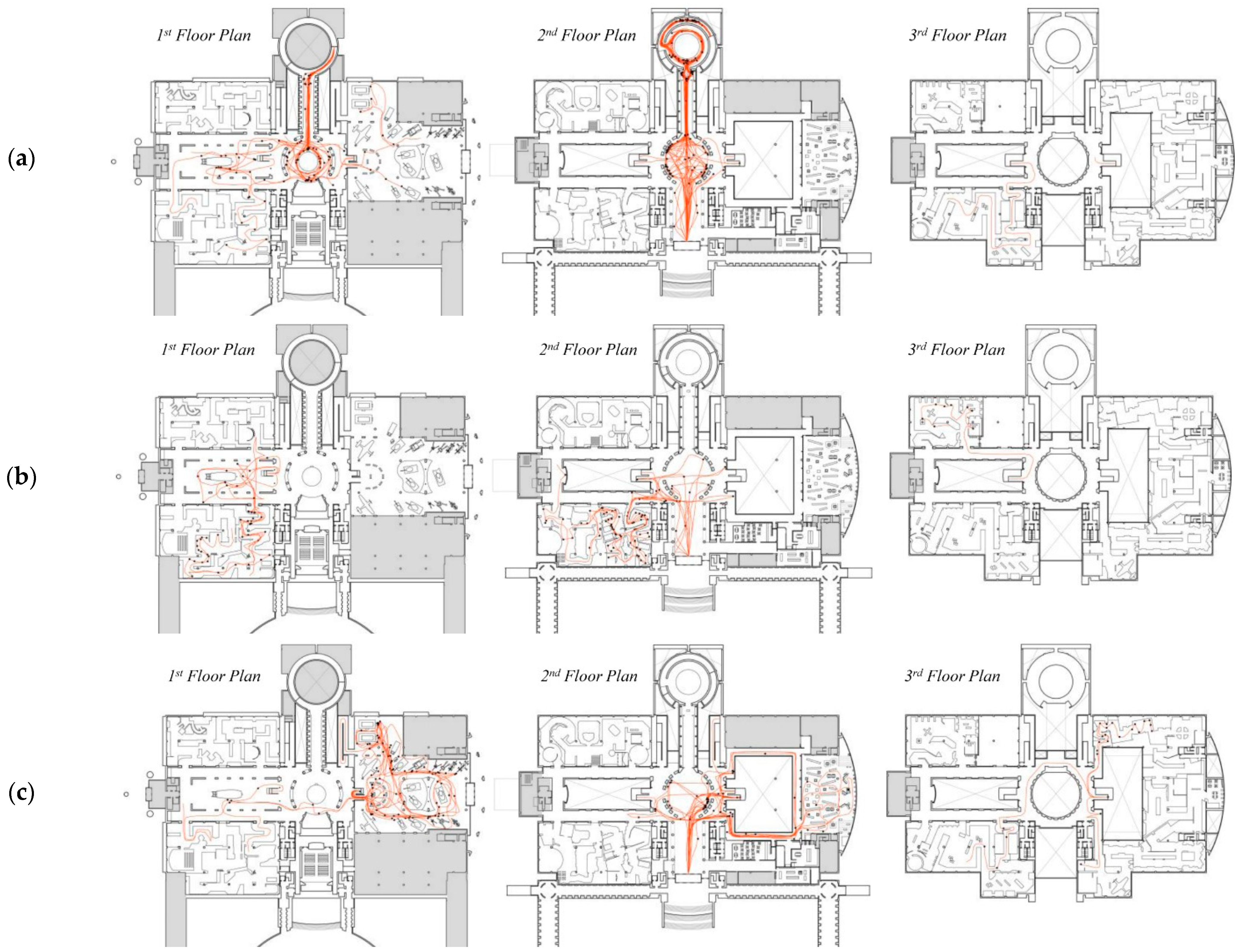

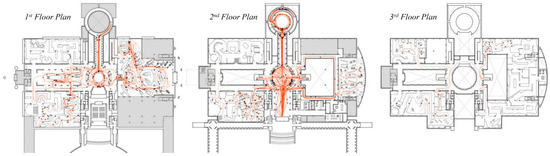

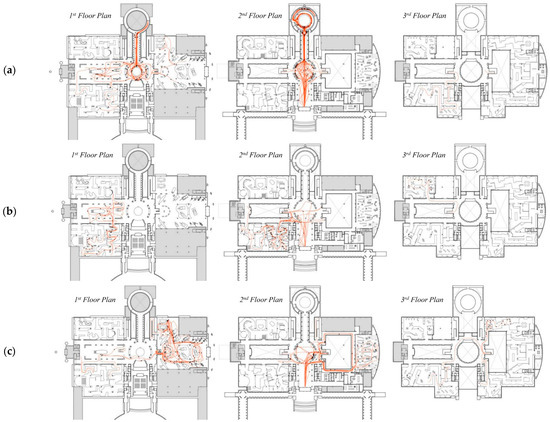

As listed in Table 1, about five-sixths of the total number of subjects (46 out of 55) were natives, whereas the remaining sixth (9 out of 55) were foreigners. Except for two individual participants, most of them came along with family members, including foreigners (the average number of companions was 2.8). Subjects walked approximately 256 m from the entrance for the first 10 min, and stopped 11 times on average to engage with artifacts and presentation panels. When we look at the movement tracking data (Figure 8), there are different movement patterns particular to each floor. On the second floor, subjects consistently move along the main axis, spanning from the entry point to the memory halls. On the first floor, however, subjects are likely dispersed at the lower central hall. It can be argued that, in general, the subjects move around differently depending on the floor.

Table 1.

Quantitative profiles of subjects and groups.

Figure 8.

Movement tracking results observed for the first 10 min from the entrance.

Now, we move on to the directional splits of the movement tracks to explore whether there would be substantial distinctive features among visitors, with the following questions, how visitors experience differences across the building and how their movement patterns are related to the configurational feature or the public memory, which is constructed and suggested by the museum itself.

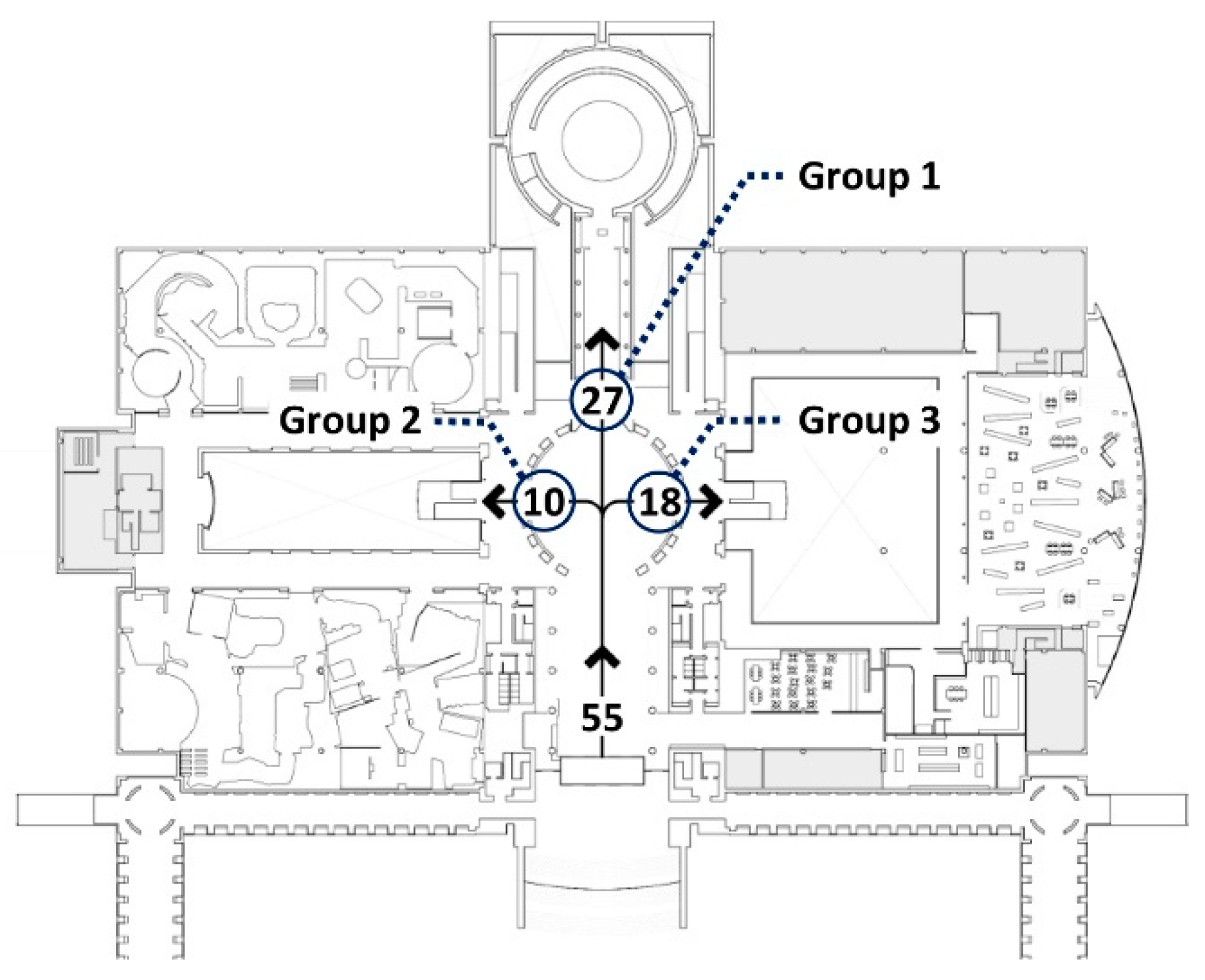

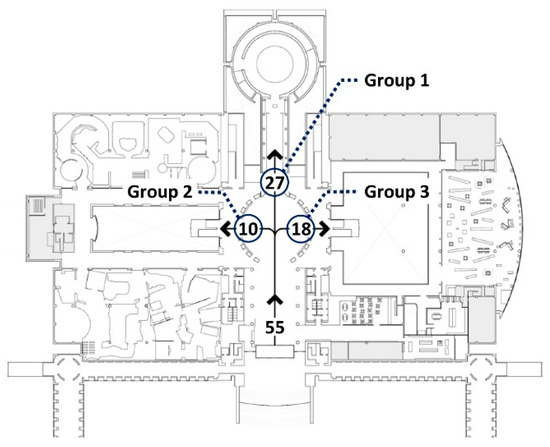

Table 1 and Figure 9 show the results of the directional splits: a total of 27 subjects took the straight forward direction from the entry point, these visitors were categorized as “Group 1”; 10 subjects made a left turn, these visitors were labeled as “Group 2”; the rest (18 out of 55) headed to the right side of the building, these visitors were labeled as “Group 3”. Approximately half of the subjects (27 out of 55) selected the cross-sectional direction (i.e., the north–south axis), whereas the rest (28 out of 55) selected the longitudinal direction on both sides of the building (i.e., the east–west axis).

Figure 9.

Analysis of directional splits derived from the movement tracking data. Numbers indicate total number of subjects in accordance with directions.

Regarding the quantitative profiles of the groups, two-thirds of the foreigners (6 out of 9) moved along the cross-sectional axis, whereas the rest (3 out of 9) selected either the right or left direction. Subjects in Group 2 covered smaller distances from the entry point (e.g., 236.2 m) when compared to the other groups (e.g., Group 1 and Group 3 walked 259.7 and 264.3 m, respectively), but Group 2 engaged with more objects (e.g., 13.8 times) than the rest (e.g., Group 1 and Group 3 stopped 11.0 and 10.1 times, respectively). Although there was no statistical significance among the groups, it could be argued that the subjects of Group 2, who headed to the exhibitions of the Korean War or War History first, made more stops to engage with artifacts and walked shorter distances. In contrast, the subjects of Groups 1 and 3, who headed to either the memory hall, archive center, or the large military equipment exhibition first, moved around faster and stopped less than Group 2.

Now, let us consider movement patterns (Figure 10). Regarding the movement patterns of Group 1, visitors, without any exception, moved along the structured route, which started from the memory halls to the lower central hall on the first floor in a transitional manner. In particular, they moved around in the first memory hall with a number of stops to read the contents of the exhibition board, which is also found in the lower central hall, where the movements of visitors are strongly influenced by the objects. From the lower central hall, they headed to either the exhibition of large military equipment or war history through the inner plaza. It is suggested that this direction embodies a ritual or commemorative experience until reaching the lower central hall.

Figure 10.

Grouped movement tracking data in accordance with the directional splits: (a) movement patterns in Group 1; (b) movement patterns in Group 2; (c) movement patterns in Group 3.

Concerning the movement patterns of Group 2, 4 out of 10 subjects directly headed to the Korean War exhibition on the second floor, five of them looked at Geobukseon in the inner plaza through the stairs, subsequently moving around in the adjacent spaces for a while, and thereafter moving toward the ‘History of War’ exhibition; only one subject went up to the third floor to see the donated artifacts. What is interesting is that their movements seem to be very confident such that they went directly to one of the exhibitions without hesitation. In other words, visitors constructed meaningful itineraries within an integration core. Therefore, we proposed that this direction is disciplinary.

How was Group 3? Did it behave differently in any meaningful way from the other groups? Let us examine the movement patterns depicted in Figure 10; they are strongly associated with the spectacular view, which is organized by large military equipment such as firefighters hanging from the ceiling, real-size tanks, or armored vehicles used in the Korean War, with a scenic view of a battlefield. Interestingly, all objects were placed in perspective so that the visitors could easily grasp the entire view from the stairs. In addition, the edges along the void (i.e., corridors) help visitors look over the military equipment, so that the spectacular scene is much more enhanced vertically. Therefore, we contend that this direction is an eye-catching or object-driven experience along the integration core.

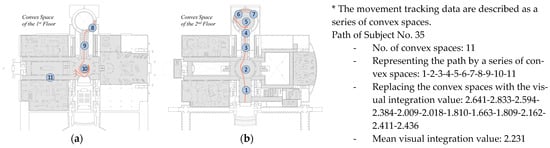

6. Discussion

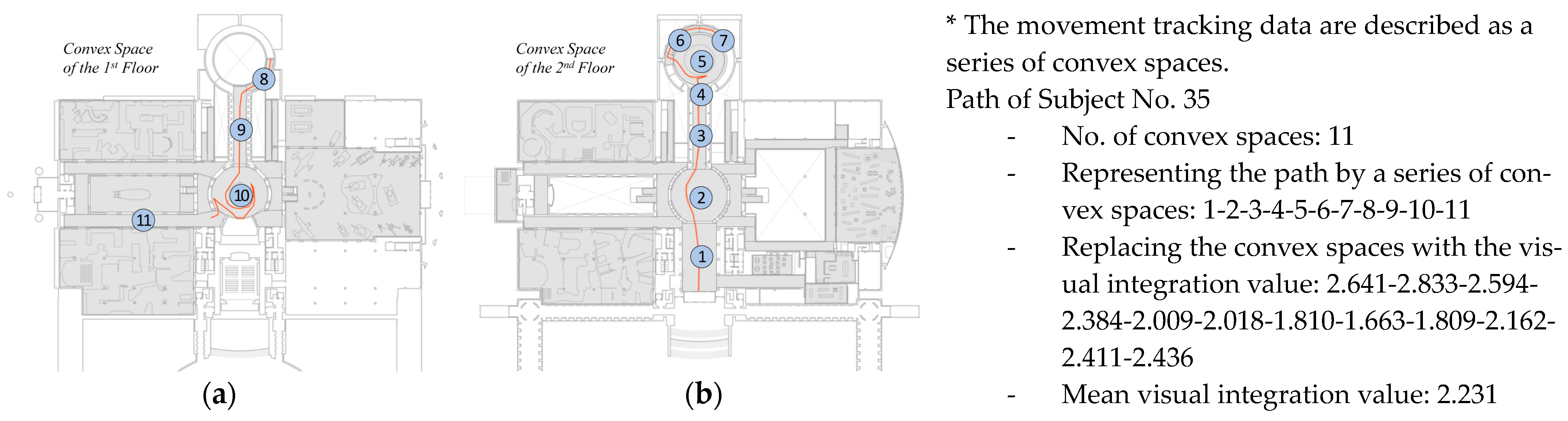

Let us move on the research question of how these movement patterns would be related to the configurational properties such as visual connectivity and integration values across the plan. In order to answer this question, the syntactical results obtained from the VGA analysis are superimposed into convex spaces as follows; firstly, convex spaces are created on the plans, and the visual connectivity and integration values are exported to the convex spaces. Each convex space has a unique attribute value derived from the VGAs, and, therefore, the movement tracks have their particular attribute values. In Figure 11, for instance, the trail taken by the subject no. 35 is described as a series of convex spaces like 1-2-3-4-5-6-7-8-9-10-11. These convex spaces can be represented by a string of the mean visual integration values such as 2.641-2.833-2.594-2.384-2.009-2.018-1.810-1.663-1.809-2.162-2.411-2.436, or by the mean number of these values like 2.231. Therefore, the trail performed by the subject no.35 is explained by the unique syntactical attribute value of 2.231.

Figure 11.

Example of representing the path with the visual integration value: (a) the movement track on the first floor by Subject no.35; (b) the movement track on the second floor by Subject no.35. * This is an example of a series of convex spaces for the path of Subject No. 35.

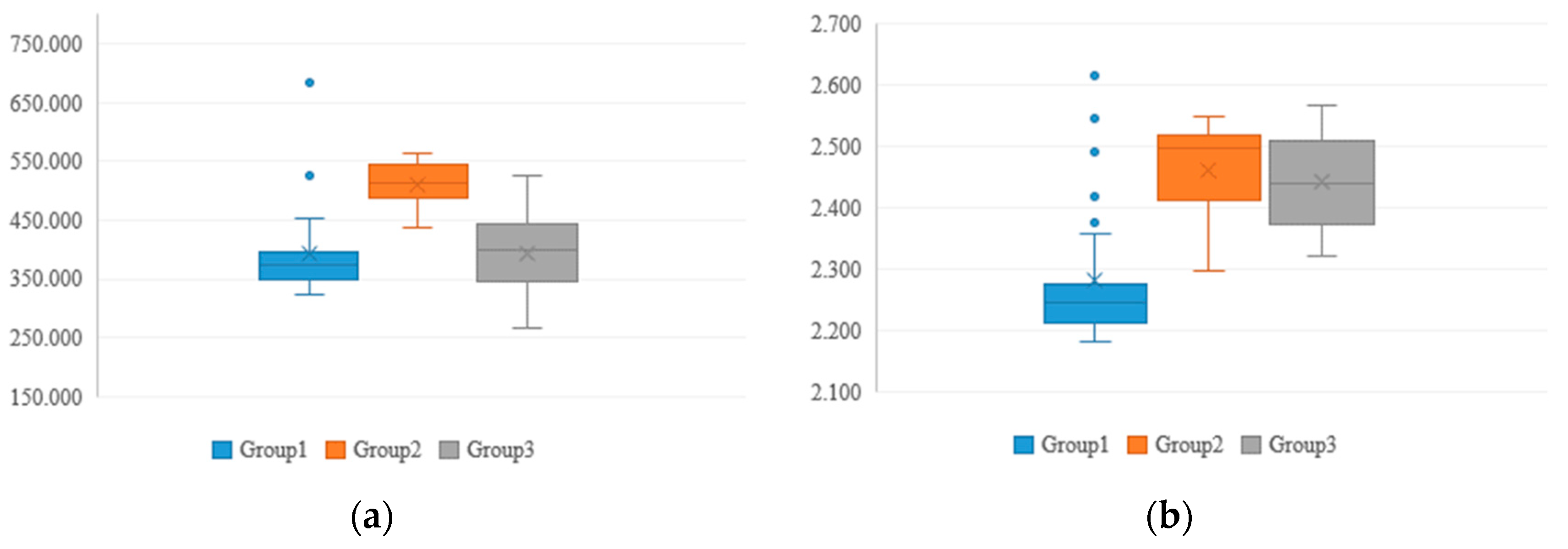

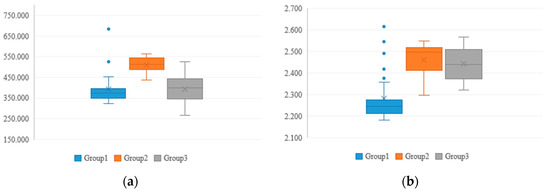

Table 2 shows the summary of syntactic properties of the movement tracks. Regarding the visual connectivity, on the one, the mean visual connectivity of group 2 (511.267) is relatively higher than those of group 1 (392.083) and group 3 (392.728). This means that the visitors in group 2 made their journey along directly connected convex spaces, whereas the others in group 1 and group 3 move along less directly connected convex spaces. Regarding the visual integration, on the other hand, the mean visual integration of group 1 (2.282) is relatively less than those of group 2 (2.459) and group 3 (2.442). It means that the movement pattern of group 1 is formed along the deep, segregated spaces. When we see the result of a box and whisker plot in Figure 12, it is quite clear that the paths of group 2 are strongly related to integrated spaces more than the others.

Table 2.

Summary of syntactic properties of the movement tracks in three groups and one-way ANOVA result.

Figure 12.

Box and whisker plot for the syntactic properties of the movement tracks in three groups: (a) the visual connectivity; (b) the visual integration.

Therefore, two distinctive sequences are defined in this memorial museum: one of them is a commemorative sequence, leading directly to the consecutive memorial spaces but minimizing social potential because of its limited visibility; and the other one is a disciplinary one, allowing visitors to move around across the floors. The former acts in a conservative mode along the consecutive memorial halls, and the movement through these spaces plays a role in representing public memory and in transmitting it to the visitors as well. However, the latter acts in a generative mode, enabling visitors to construct their own knowledge along the integration core.

7. Conclusions

The Korean War is not over yet; it was provisionally stopped by the armistice agreement. There are still military conflicts between the two Koreas, and they have been competing with each other by developing armories, weapons, and military equipment for approximately seven decades. The demilitarized zone (DMZ) stands out for the very peculiar situation of having been divided until now. Therefore, the WMoK aims to facilitate a total record of the ongoing Korean War, to commemorate those who gave their lives for Korea, to share the collective understanding of the past, to educate how miserable war can be, and to give a clear message of ‘never again’ to future generations.

It should be noted that communicating what happened in the past to future generations is important because memory is partial and, as a result, it could be manipulated or mediated by certain interests or desires of the present. Because of its indefinite characteristics, public memory requires a place that offers a sustainable relationship between the past and present. Hence, the WMoK embodies public memory not only by narrating war experiences and exhibiting artifacts but also by remembering significant historical events and commemorating the national spirit. These propositions are realized by designing the site: the passageway from the main entrance to the memorial hall on the second floor of the building is gradually elevated by placing slopes and stairs; the site is carefully defined into meaningful areas, such as an entry square where the Korean War Monument stands, a grand memorial plaza with monuments for commemorating the participation and sacrifices of the UN forces, and the surrounding gallery with the roll of honor of those who lost their lives in the Korean War. Importantly, this axis works as a ritual sequence to the past from the present, and thus serves as a place of remembrance and commemoration.

However, museum buildings also articulate propositions. An in-depth investigation of syntactical features and movement patterns revealed that the spatial layout provided distinctive spatial experiences across floors. First, it is a locally focused spatial experience that leads directly to the most commemorative sequence, starting from the memorial halls to the lower central hall via the transitional space. This strongly organized walking sequence regulates visitor spatial behavior so that their spatial experience is identical. Second, there are globally dispersed spatial experiences present along the main stairs within the two voids. One is strongly related to the specific themes and content of the exhibitions, although there were some wanderings in the memorial hall on the second floor. The other is closely incorporated into the spectacular scene generated by full-scale military vehicles, armor, tanks, aircraft, and artillery. Interestingly, this journey produces a richer spatial structure through the voids.

A locally focused path is prescribed via movement through the halls or by adding depths. In contrast, globally dispersed paths were suggested by the integration core running from the first memorial hall to the stairs beside the voids, and spatial experiences are characterized not so much by restrictive and local movements, but by disciplinary knowledge and cross-referencing objects. Unlike the preliminary conception of the program relationships, the first memorial hall acts as both a ceremonial space for commemoration and a social space for gatherings.

Let us come back to the research questions of how architectural language, particularly the concept of movement through space, shapes the shared understanding of the past in a public memory place, how spatial configurations affect visitor’s movement patterns, and, lastly, how memorial museum works. Throughout an in-depth investigation of the case study, we conclude that the WMoK works as a memorial museum and dedicates itself to the remembrance and commemoration of the Korean War by means of locally separate spaces, which helps us ask questions about what happened during the war. It works as a war museum by collecting, conserving, interpreting, and exhibiting tangible and intangible heritage related to wars in the Korean Peninsula by means of globally integrated spaces. Based on these substantial results, architectural language represents and conveys the public memory of the Korean War, and the path is decisively used to serve and deal with the various roles and purposes of memorial museums. In addition, it should be noted that the space layout reflects the museum intentions very well.

According to James Young, historical inquiry is closely related with the issues of “what happened” and “how it is passed down”, and, in particular, the latter should be engaged with the act of memory [21]. This is because it is used to elicit collective identification, provide shared perspectives on understanding the past, and suggest a better way of looking at the future. Seventy years have passed since the Korean War began, and the war generation has been dramatically outnumbered by the postwar generation. This trend is expected to accelerate over the next decade. However, it is expected that the WMoK will serve as a cornerstone to conserve and represent collective memories through spatial configuration, and to provide a shared perspective on the past through distinctive spatial sequences.

This study specifically focused on exploring how the memorial museum works, and particularly how spatial configuration embodies the public memory and affects spatial experience by using space syntax theory and movement tracking. However, it is still deficient in many ways: firstly, only one case study has been performed. It means that a number of memorial museums should be examined in order to make sure whether the results are valid or not. Secondly, there is still doubt regarding to what degree visitors who took the commemorating sequence actually understand the given public memory. In addition, it should be investigated whether the visitor’s backgrounds, such as previous visits, frequency of visits, estimated length of staying, motivations, or (probably one of the most important profiles) war or postwar generations, would be related to the different spatial experience (particularly commemorating one). Therefore, follow-up studies should be carried out to entirely understand the configurational relationship between public memory and museum architecture.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

References

- Sodaro, A. Exhibiting Atrocity: Memorial Museums and the Politics of Past Violence; Rutgers University Press: New Brunswick, NJ, USA; London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Blair, C.; Dickinson, G.; Ott, B.L. Introduction: Rhetoric memory place. In Places of Public Memory; Dickinson, G., Blair, C., Ott, B.L., Eds.; The University of Alabama Press: Tuscaloosa, AL, USA, 2010; pp. 1–54. [Google Scholar]

- Nora, P. Realms of Memory: Rethinking the French Past; Lawrence, D.K., Ed.; Goldhammer, A., Translator; Columbia University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Broudehoux, A.; Cheli, G. Beyond starchitecture: The shared architectural language of urban memorial spaces. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2022, 30, 160–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markus, T.A. Buildings & Power: Freedom and Control in the Origin of Modern Building Types; Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Brawne, M. The New Museum: Architecture and Display; Frederick A. Praeger: Washington, DC, USA, 1965. [Google Scholar]

- Duncan, C.; Wallach, A. The museum of modern art as late capitalist ritual: An iconographic analysis. Marx. Perspect. 1978, 1, 28–51. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J.H.; Kim, Y.S. Rethinking art museum spaces and investigating how auxiliary paths work differently. Buildings 2022, 12, 248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowenthal, D. The Past is a Foreign Country; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Landsberg, A. Prosthetic Memory: The Transformation of American Remembrance in the Age of Mass Culture; Columbia University Press: New York, NY, USA; Chichester, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Sturken, M. The wall, the screen, and the image: The Vietnam Veterans Memorial. Representations 1991, 35, 118–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hillier, B.; Hanson, J. The Social Logic of Space; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Hillier, B.; Hanson, J.; Graham, H. Ideas are in things: An application of the space syntax method to discovering house genotypes. Environ. Plan. B Plan. Des. 1987, 14, 363–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benedikt, M. To take hold of space: Isovists and isovist fields. Environ. Plan. 1979, 6, 47–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, A.; Doxa, M.; O’Sullivan, D.; Penn, A. From isovists to visibility graphs: A methodology for the analysis of architectural space. Environ. Plan. B Plan. Des. 2001, 28, 103–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yanni, C. Nature’s Museum; The Athlone Press: London, UK, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Peponis, J.; Hedin, J. The Layout of theories in the Natural History Museum. 9H 1982, 3, 21–25. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J.H. The Impact of Maps on Spatial Experience in Museum Architecture. Ph.D. Thesis, The Bartlett UCL, London, UK, 28 October 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Hillier, B.; Major, M.D.; Desyllas, M.; Karimi, K.; Campos, B.; Stonor, T. Tate Gallery, Millbank: A Study of the Existing Layout and New Masterplan Proposal; UCL: London, UK, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Korea War-meemorial Organisation. The War Memorial of Korea: The Ten Years History; The War Memorial of Korea Press: Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Young, J. Daniel Libeskind’s Jewish Museum in Berlin: The uncanny arts of memorial architecture. Jew. Soc. Stud. 2000, 6, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).