Abstract

This research explores the development and validation activities of a bio-based façade system within the Basajaun H2020 project, focusing on enhancing the utilization of bio-based components within building envelopes to replace conventional solutions with eco-friendly alternatives. This paper reports the methodologies employed to detect requirements and outline the testing protocols undertaken to validate the façade system design devised within the project, focusing on the original façade components as the biocomposite profile. Vision and opaque façade modules are prototyped and tested following curtain wall standards for performance (EN 13830:2015) and acoustic assessments (EN ISO 717-1:2020) to showcase the efficacy of the developed solution. The conducted tests demonstrate the feasibility of integrating bio-based components as alternatives to conventional materials into building envelopes, aligning with project expectations and prevailing standards for curtain wall façade solutions. Notably, the designed façade system meets technical conditions and research objectives. Nevertheless, the paper underscores the need for further refinements to facilitate solution industrialization and explore broader market applicability focusing on the biocomposite profile.

1. Introduction

The construction sector contributes to 30% of raw material utilization, nearly 40% of greenhouse gas emissions [1,2], and up to 40% of solid waste generation [3]. Consequently, integrating bio-based materials into the construction industry has emerged as a focal objective within EU policies, aimed at fostering sustainable practices across the entire value chain [4,5] and throughout a building’s lifespan to reduce the carbon emissions [6,7] as well as contributing to reducing pollution and resource consumption [8,9,10,11,12].

The integration of bio-based components presents more than just an environmental advantage; it offers a gateway to reimagining building products through the synergy of bio-economy and circular economy concepts [13,14]. This approach has the potential to not only enhance environmental sustainability but also to optimize industrial-scale production value chains. Therefore, by investigating renewable and biodegradable resources, bio-based materials offer a compelling solution to mitigate the ecological footprint associated with building envelope façades [15].

The building envelope represents an important building component, since it serves as a multifaceted system tasked with delineating outdoor and indoor environments while meeting stringent criteria and integrating diverse technologies encompassing thermal, acoustic, and mechanical performance [16,17], ensuring indoor comfort [18] and energy performance [19]. The current benchmark for curtain wall façades is represented using aluminum components, glazed panels, and mineral wool as insulation, which is a mature technology within the market. The growing demand for bio-based materials in building envelopes stems from their versatility, compatibility with modern design, and ability to address technological requirements [20,21,22]. Moreover, the prefabrication process involved in curtain walls enhances the design of eco-conscious façade systems, contributing to sustainable buildings. Paramount considerations include factors such as disassembly, reuse, and recycling, as well as efficiency in manufacturing, waste production, and maintenance [23,24,25].

In this context, the Basajaun H2020 project (G.A. 862942) [26,27] represents a boost in the adoption of bio-based materials for the building envelope sector. It plays an important role in the research and innovation sector; indeed, its objectives are to integrate wood-based materials into building product systems, thereby fostering increased acceptance and utilization of biomaterials within the construction market. Within this activity, this paper presents the results of the prototyping and testing activities conducted in line with normative market requirements to validate the façade system modules developed within the Basajaun project in the designing phase. The research is also based on a previous VII Framework Programme project (Osirys—G.A.: 609067) [28,29] where a first version of the use of a biocomposite profile was developed and protected under a patent (EP3628790).

In addition, within the Basajaun H2020 project, the study highlighted the sustainability benefits of integrating bio-based solutions into façade systems, investigating their environmental impact through an Embodied Carbon Assessment (ECA). The results showcased reduced embodied emissions by substituting conventional materials with wood-based components and novel biocomposite frame profiles, which is particularly evident in the decreased carbon footprint associated with replacing aluminum frame profiles [30].

This article aims to demonstrate the effectiveness of using bio-based and alternative components as substitutes for conventional materials within prefabricated façade systems through iterative methodologies. Therefore, it investigates and reports multifaceted considerations and decision-making processes underlying the development and integration of environmentally sustainable products within façade system modules. In particular, this article’s objectives are to investigate and provide contributions in the scientific field in the validation of bio-based curtain wall façade systems, regarding the façade manufacturability and the normative compliance to testing in an accredited laboratory, focusing on the original façade components as the biocomposite profile. Indeed, the research validates the manufacturability of the biocomposite profile in pultrusion lines and the relative cutting and machining phase in Computer Numerical Control (CNC) machines. Moreover, the research aims to assess the manufacturing of bio-based façade system modules while defining the prototypes’ weak points and the industrialization issues in the off-site manufacturing process to meet industrial needs for a wide replication in the market.

The paper is structured as follows: Section 2 outlines the methodology applied and materials used for the validation and testing phase. Section 3 presents the outcomes from the manufacturing and testing activities of the components and the overall prototyping of the façade system modules. Section 4 reports the results obtained during the validation and testing phase, and defines the successful aspects of integrating bio-based and alternative components in the façade. In this section, the issues which emerged during the manufacturing stages and gaps identified due to research and test limitations are declared and reported. Section 5 summarizes the main achievements related to the paper’s goal of analyzing the opportunities for bio-based façade system modules.

2. Materials and Methods

The methods applied in the research comprise the following three stages:

- Identification of validation activities—based on designing validation and desk simulation conducted in the designing phase, a list of testing is defined to demonstrate the feasibility of manufacturability and integrability of the components in the façade system modules. Indeed, based on the research objectives and the defined test activities, the standards to be addressed were identified.

- Prototyping and testing activities—testing activities for manufacturing and normative validation of bio-based façade system modules are conducted to align with product requirements and expected outcomes to collect data and analyze the results achieved. Therefore, in this phase the test procedure and standard compliance for system validation is defined, focusing on the performance and acoustic tests. This stage allows to validate modules against requirements, identifying weaknesses, and implementing improvements. This step is divided into: (i) the test preparation phase—the norms and therefore the method statements, and the facilities for each test are defined; (ii) design and manufacturing—the Basajaun modules are designed for each test and manufactured; and (iii) tests and performances achieved—the tests are conducted, and the results collected.

- Analyze the obtained results—this stage aims at identifying weaknesses and opportunities for bio-based façade system modules based on the test results. Indeed, a specific focus is given to gaps and barriers to challenge for market introduction by identifying weak points and improvement opportunities for further activities.The materials for the research activity are:

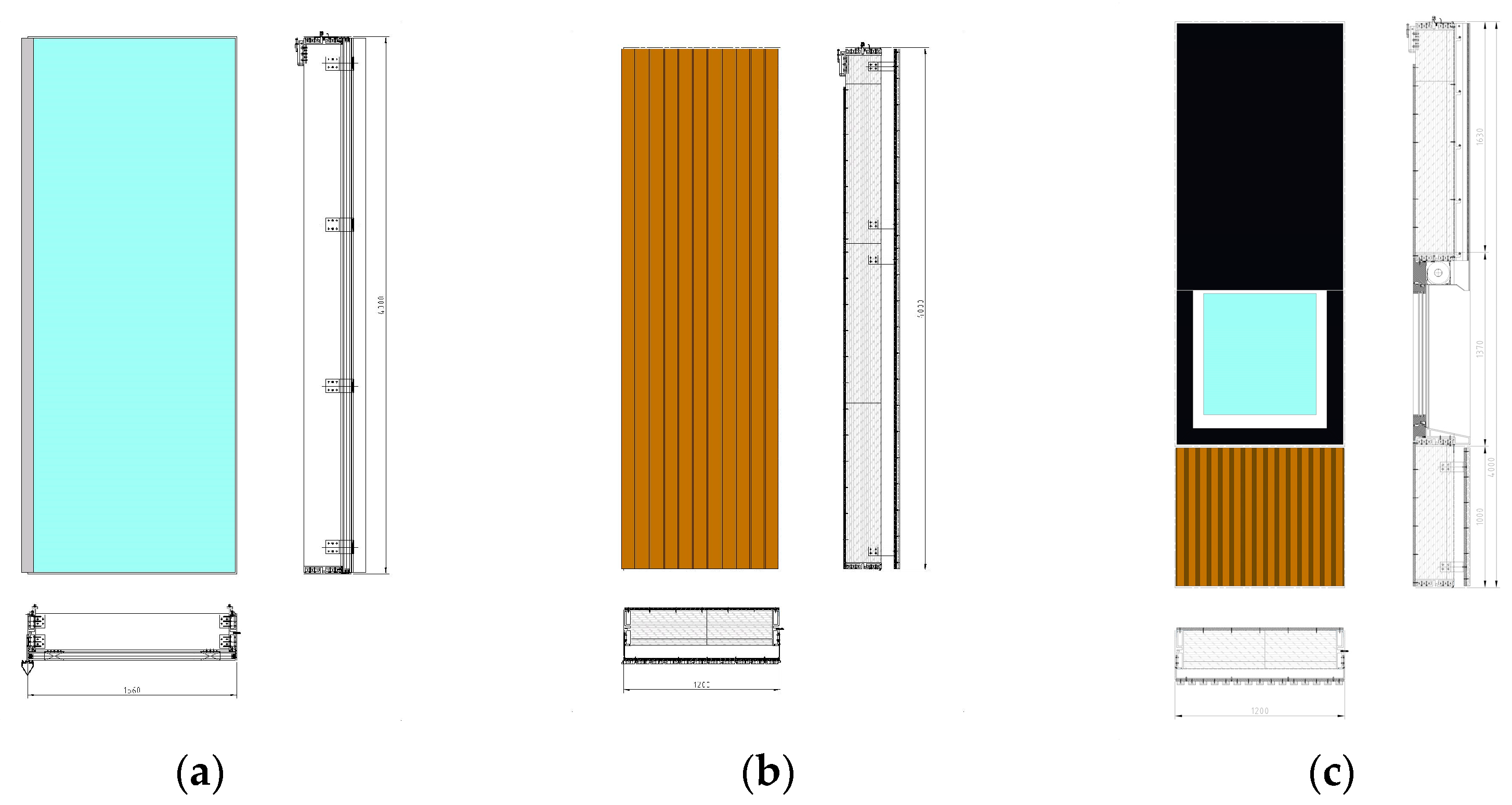

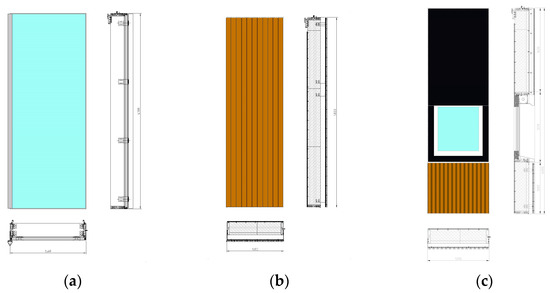

- Façade system design defined in Basajaun project—more detailed insights derived from the development of the Basajaun façade system are presented in Pracucci et al. [31] offering the methodology applied for the designing phase. Figure 1 shows the final design configuration of three façade typologies while Figure 2 depicts a zoomed in image of the horizontal section of the opaque façade module.

Figure 1. Drawings of façade modules (vision on the left, opaque in the middle and window modules on the right): vision façade module (a); opaque façade module (b); window façade module (c).

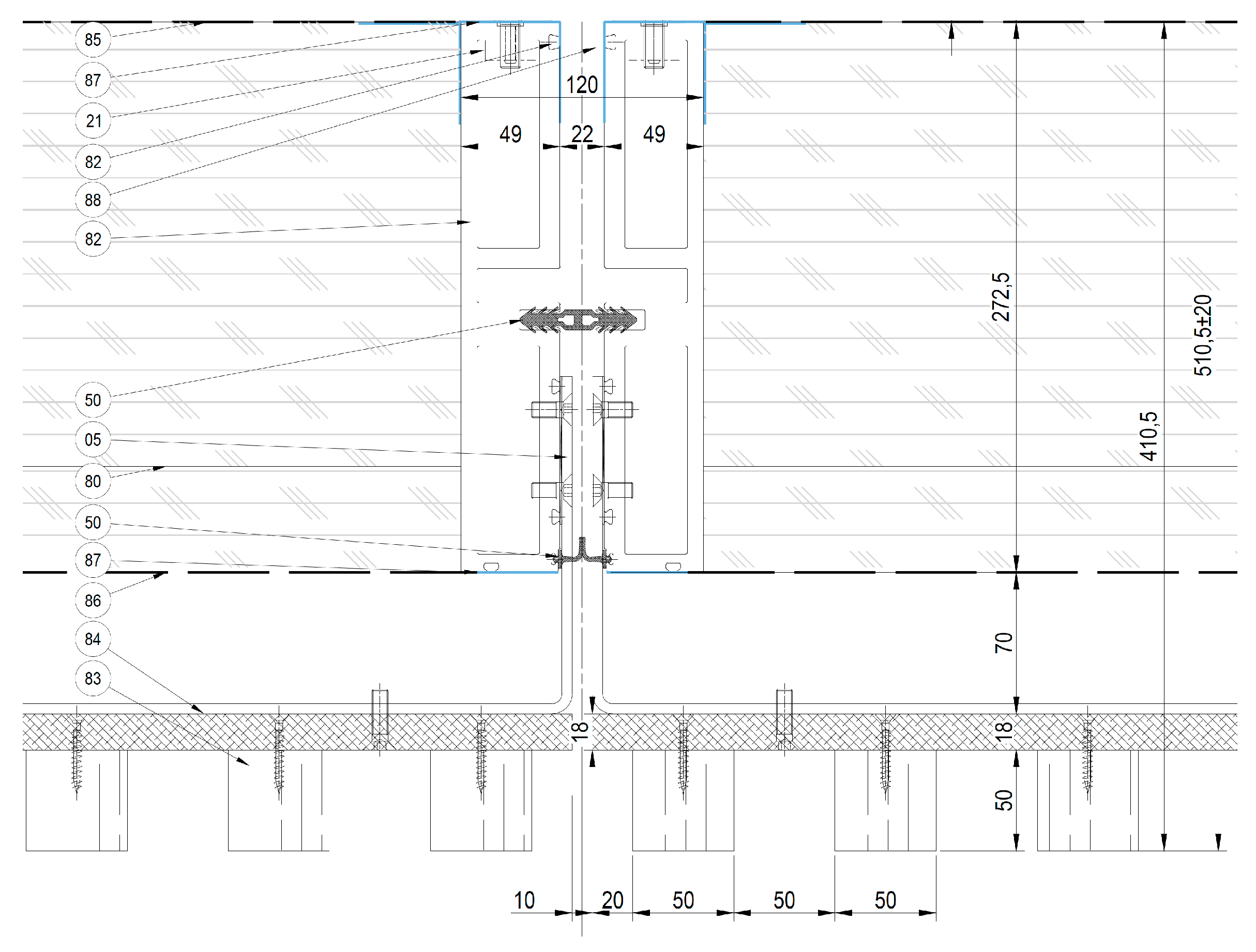

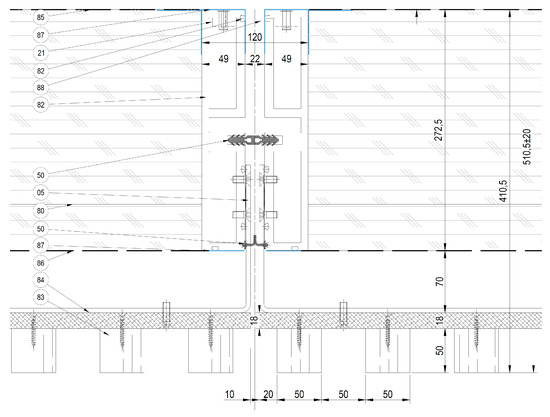

Figure 1. Drawings of façade modules (vision on the left, opaque in the middle and window modules on the right): vision façade module (a); opaque façade module (b); window façade module (c). Figure 2. Final solution: horizontal section of the Basajaun opaque façade module.

Figure 2. Final solution: horizontal section of the Basajaun opaque façade module.

Important to mention are the technologies integrated within the façade system to replace the standard components:

- ○

- Insulation—the conventional material in curtain wall façades is mineral or rock wool. In the Basajaun façade system, an insulation material of comparable thermal resistance composed of wooden fibers has been selected. The choice of wooden fibers over synthetic alternatives underscores a commitment to eco-friendly design [32] with the aim to demonstrate the balance between aesthetic, ecological, and technical performances. The selected insulation has a thickness of 220 mm and 50 mm, gross density of 55 kg/m3, and thermal conductivity of 0.038 W/(m2 × K).

- ○

- Frame profile—Biocomposite profiles feature a blend of components, primarily composed of a bio-based resin system and basalt fiber reinforcement. Within the material ratio, the reinforcement accounts for 55%, comprising endless roving fibers and various types of woven roving. The resin system, constituting 45% of the composite, is a complex amalgamation of elements. Notably, 30% of the base resin is bio-based, incorporating succinic acid instead of conventional orthophthalic or isophthalic acid and recycled components. The bio-based resin system is enriched with a range of additives, including a shrinkage reducer, internal mold release agent, accelerator, catalyst, color paste, and air bubble remover additive. Additionally, 3% of the resin system is comprised of wooden particles, all of which are bio-based.

- ○

- Membrane and tapes as tightness and wooden plywood as stiffness layers—these technologies replace the conventional aluminum sheets. The selected membrane is in aluminum/PE and glass fiber, with a thermal conductivity of 0.0007 W/(m*k), water impermeability Class W1, and fire classification (EN 13501-1 [33,34]) class A2-s1, d0. The stiffness layer supports the assembly structurally, distributing loads and resisting deformation. For the Basajaun façade, 18 mm-thick plywood panels are employed as a bio-based alternative in wood-based façade system modules.

- ○

- In the design, the selected insulation and tightness layer are on-market technologies, while the biocomposite profile is an original product developed within the project.

- Also included is the method statement for testing activities conducted in a laboratory environment to validate façade system modules, based on EN 13830:2015 [35] and EN 14019:2016 [36] for curtain walling—impact resistance—and performance requirements and local norms for thermal behavior. These European standards specify the requirements for lightweight façades intended for use in the building envelope to provide weather protection, safety in use, energy savings, and heat retention. The performance test sequence is reported in Table 9. In addition, for the acoustic validation, the tests are performed by following the EN ISO 717-1:2020 (IN-OUT test) standards [37].

3. Results

The Basajaun façade system is defined based on requirements and market standards for both vision and opaque typologies of curtain wall façade systems. Applying the Basajaun façade in demonstration buildings serves as the initial validation in real-world settings with stakeholders. The target for each demo is to have an innovative product that complies with all the requested outcomes for the façade. The EN 13830:2005 standard is used as the norm of reference for the testing activities and the requirements to be achieved, while also complying with those defined by the demo buildings and those to be further described.

Additionally, particular emphasis is placed on validating the implementation of biocomposite materials within the Basajaun façade system. While curtain façade technology with aluminum profiles is well-established in the market, the utilization of pultrusion materials constitutes a novel contribution to building envelopes, necessitating careful consideration of specific requirements. The research explores the feasibility of incorporating pultruded bio-based components by testing their performances and characteristics.

The following paragraphs present the validation of the final design of the bio-based façade system resulting from the previous evolutions, requirements, and considerations.

3.1. Identification of Validation Activities

Based on the identified requirements during the designing phase of the project, a set of validation tests during the integration of the components have been defined at different stages of the development of the façade systems. Table 1 reports an outline of the activities deployed for validation.

Table 1.

Testing activities to validate the integration of alternative components into curtain wall façade.

3.2. Façade Prototyping and Testing Phase

The following chapter reports the tests conducted to validate the developed façade system design. It begins with the validation of the properties and characteristics of the biocomposite profile. Subsequently, adhesion and compatibility tests were conducted among the biocomposite profile and façade components to ensure proper integration. Finally, the façade systems were manufactured, and performance and acoustic tests were conducted.

3.2.1. Bio-Based Profile Testing

The bio-component pultruded profile for the façade module system has undergone various tests to ensure its suitability for inclusion in the system. It is important to note that this material, although based on wood, has been configured as a composite by mixing resins and fibers to create a plastic composite. Through an iterative manufacturing process involving adjustments to the pultrusion process velocity and curing temperature, the results obtained align with the expected profile design. Figure 3 shows the first pultruded profile demonstrating the effectiveness of the material properties and the design. Indeed, these tests confirm the compatibility of the material and its configuration within the system.

Figure 3.

Image of the bio-based pultruded profile tested.

Based on the standard “EN 13706-2:2002 Reinforced plastics composites—Specifications for pultruded profiles—Part 2: Methods of test and general requirements” [38], the first tests were conducted, and the results were compared with the values tabulated in the UNE-EN 13706-3 standard [39] (Table 2), obtaining the highest classification you can have.

Table 2.

Minimum properties regarding EN 13706-2:2002.

Table 3 shows the tests conducted by each specific standard, and demonstrates the good properties obtained for this bio-component pultruded profile for the façade module system. The tests that do not appear were not made for the dimensions of the profile and therefore cannot provide standard test specimens.

Table 3.

Properties of bio-based profile according to specifications EN13706-2:2002.

In order to increase the performance of the profile and, above all, to assess how it could behave against aggressive agents, the Table 3 shows the results of mechanical tests carried out in addition to those described above and physical tests to evaluate its properties (Table 4).

Table 4.

Mechanical tests.

Based on these results, including tensile properties before and after aging tests, it can be confirmed that crucial mechanical properties such as tensile properties remain unaffected by aging. The material maintains its rigidity (27.1 GPa before aging and 28 Gpa after), tensile stress (409 MPa before aging and 388 MPa after), and tensile strain of 1.7% compared to 1.4%. These values are consistent, considering the standard deviation shown in each test. Moreover, the latest test conducted on the profiles indicates improved flexural properties compared to previous ones, with a 25% increase in elasticity modulus and a 35% increase in flexural strength, as shown in Table 5. As a result, the performance of both the profiles and the system surpasses the expectations set by the mechanical calculations.

Table 5.

Improvement of the flexural strength and the flexural modules with the last tests conducted on the material.

Regarding the physical assets (Table 6), a battery of tests was conducted to validate the properties and compare them with commercial profiles. Table 6 reports all the results which are very promising, showing a performance equal to or superior to commercial profiles in some tests.

Table 6.

Physical and optical properties.

Beyond the specific results about bio-component pultruded profiles, tests were conducted to validate the compatibility between the biocomposite profile and other façade materials. In particular, the following tests were conducted:

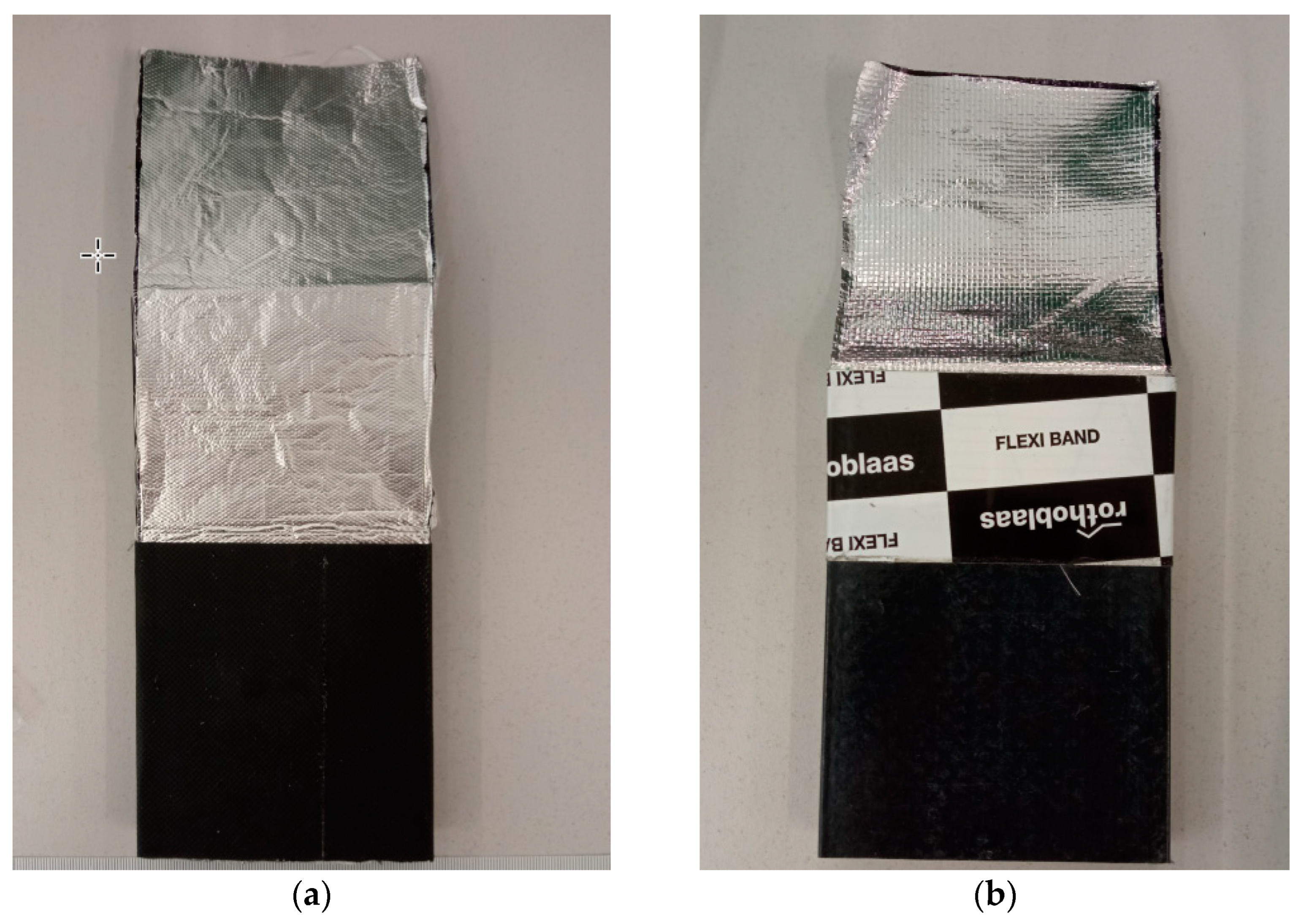

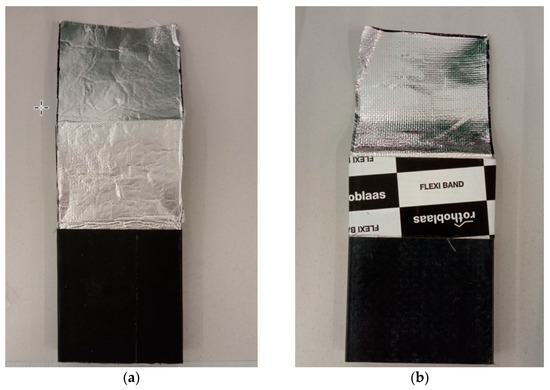

- The opaque façade’s technological systems (Figure 4) were tested for exposure to damp heat, water spray, and a salt mix under ISO 4611:2011 [53] to assess:

Figure 4. Samples for opaque façade technological system tests: air, water tightness, and wind load-resistant technological system (external side) (a); vapor barrier technological system (internal side) (b).

Figure 4. Samples for opaque façade technological system tests: air, water tightness, and wind load-resistant technological system (external side) (a); vapor barrier technological system (internal side) (b).- ○

- The internal vapor barrier technological system composed of tape, membrane, double tape, and the biocomposite profile.

- ○

- The external wind-air tightness and wind load resistant technological system composed of tape, membrane, double tape, and the biocomposite profile.

- The vision façade system, particularly the technological system composed of structural silicone and biocomposite profile, was tested for adhesion and compatibility.

For both systems, peel and shear tests were performed before and after aging in specific conditions. Peel tests were performed based on UNE EN 12316-2:2013 [54] with specimens with a width of 91 mm. Shear tests were performed based on UNE EN 12317-2:2011 [55] with specimens with a width of 91 mm and a total length of 200 mm, with a width of the joint in the middle of the specimen of 50 mm. The tests performed in each system were:

- Internal technological system:

- ○

- Shear test of the reference (procedure based on UNE EN 12317-2:2011)

- ○

- Peel test of the reference (procedure based on UNE EN 12316-2:2013)

- ○

- Shear test of the samples after an aging of 168 h at 50 °C and 70% RH

- ○

- Peel test of the samples after an aging of 168 h at 50 °C and 70% RH

- External technological system:

- ○

- Shear test of the reference (procedure based on UNE EN 12317-2:2011)

- ○

- Peel test of the reference (procedure based on UNE EN 12316-2:2013)

- ○

- Shear test of the samples after aging of 14 days at (23 ± 2) °C/(50 ± 10)% RH + 4 days at (70 ± 2) °C + 24 h at (23 ± 2) °C−(50 ± 10)% RH + UV aging according to Annex C UNE EN 13859-2:2014 [56] (336 h of UV cycle phase)

- ○

- Peel test of the samples after aging of 14 days at (23 ± 2) °C/(50 ± 10)% RH + 4 days at (70 ± 2) °C + 24 h at (23 ± 2) °C−(50 ± 10) % RH + UV aging according to Annex C UNE EN 13859-2:2014 (336 h of UV cycle phase, a total of 403 h)

Results of the peel tests are reported in Table 7.

Table 7.

Results of the peel tests.

Results of the shear tests are reported in Table 8.

Table 8.

Results of the shear tests.

Structural silicone (test description)—as mentioned above, a series of tests were conducted to guarantee the compatibility and adhesion behavior between the biocomposite profile with structural silicone and other sealants to be used in façade manufacturing (vision façade module) and in the installation stage (tightness sealing for the curtain wall façade) by the silicone supplier.

- Compatibility—performed in accordance with the adapted ASTM C1087 [57] and ETAG002 paragraph 5.1.4.2.5 [58]. Seven test pieces were produced and conditioned at a temperature of (60 ± 2) °C and (95 ± 5)% relative humidity, five for 28 days and the remaining two for 56 days.

- Adhesion—performed in accordance with the adapted ASTM C794 [59] or ETAG 002 Paragraph 8.3.2.4(6) [58]. The test assessed three pieces in immersion in water (95 ± 2) °C for 24 h, three test pieces in immersion in water at (23 ± 2) °C for 7 days, and three test pieces in an oven at (100 ± 2) °C for 7 days. The pieces were then conditioned for (48 ± 4) hours at a temperature of (23 ± 2) °C and (50 ± 5)% relative humidity. The conditioned test pieces were then subjected to tensile tests to rupture.

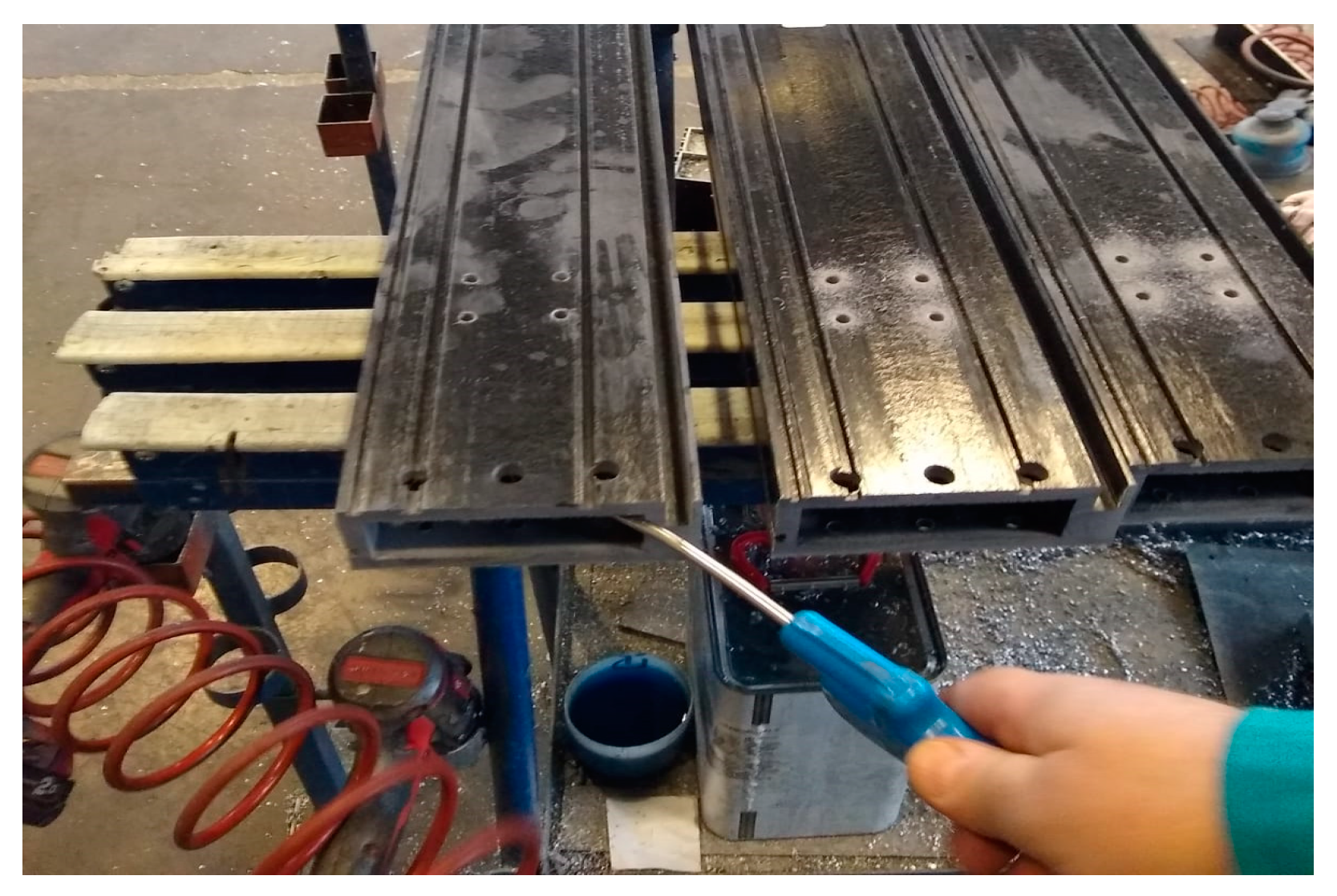

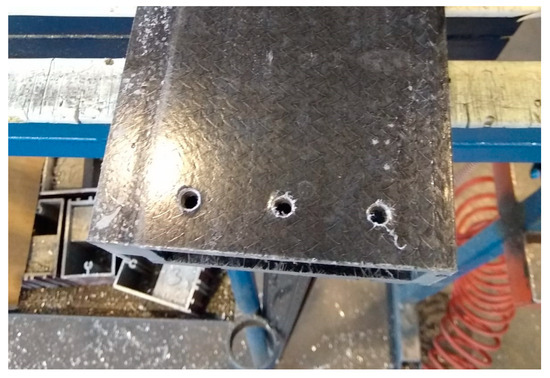

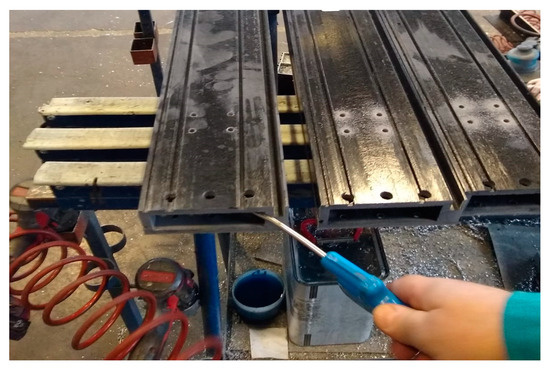

Cutting and machining—an important phase is the cutting and machining, which involves the precision cutting and shaping of the biocomposite profile to meet specific design requirements. This process typically includes tasks such as sawing, milling, drilling, and tapping to create precise dimensions and features. Overall, the cutting and machining phase is essential for transforming raw profiles bars into functional components ready for assembly in the production line. Preliminary tests were conducted on the biocomposite profile sample for cutting and machining activities with the aim to investigate its behavior, and to identify the best equipment to use to identify the most suitable tool for the biocomposite material (Figure 5). The tests revealed good properties for cutting, allowing the operation to take place without provoking any cracks or damage. However, the standard equipment used for aluminum is not suitable for the biocomposite due to the hard properties of basalt fibers, which ruined the machining during the activities. Therefore, different tools and systems need to be used. Moreover, due to the amount of resin included in biocomposite materials, a fully equipped vacuum system is needed for the generated dusts, as illustrated in Figure 6.

Figure 5.

Preliminary drilling activities.

Figure 6.

Dust removal after the machining phase.

The Basajaun biocomposite profiles after the cutting and machining process are depicted in Figure 5.

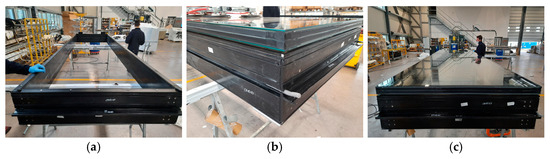

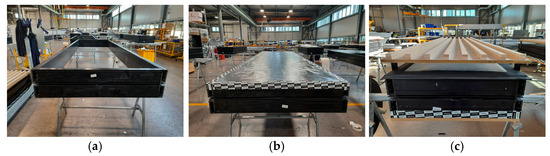

3.2.2. Façade Manufacturing

The manufacturing of prototypes for the Basajaun façade involves both vision and opaque modules. This comprehensive approach aims to showcase the design’s effectiveness and test the entire façade system. The primary objectives are to demonstrate the façade system design effectiveness and to identify potential weak points, aiming to provide valuable insights for enhancement. Therefore, the testing phase not only serves to validate the Basajaun façade system but also aligns with the norms set by the curtain wall façade (EN 13830). This demonstration emphasizes the correct design and manufacturing processes for the module, ensuring compliance with industry standards. Below, a sequence of manufacturing processes is reported; Figure 7 for vision modules and Figure 8 for opaque modules, while Figure 9 shows the three components which replaced conventional technologies: biocomposite profiles (a), membrane and tape application (b), and wooden fiber integration with the façade (c).

Figure 7.

Vision façade module prototype manufacturing: biocomposite profile frame and aluminum plate assembly (a); glass detail (b); glass on the biocomposite profile frame before the sealing (c).

Figure 8.

Opaque façade module prototype manufacturing: biocomposite profile frame assembly (a); membrane and tape positioning (b); and cladding installation (c).

Figure 9.

Bio-based profile preparation for façade prototypes after cutting and machining phase (a); membrane and tape application within the façade; (b) and wooden fiber insulation integration (c).

3.2.3. Performance Test

The Basajaun PMU has been designed considering the most relevant unit typologies and the material used in the demo buildings. Therefore, the units have been positioned on two different floors to be able to test all the possible junctions. For this reason, the n°3 vision module was positioned on the ground floor, while on the first floor two opaque units (n.1 with wooden cladding for the French demo and n.1 with the one for the Finnish demo) with a n°1 window typology were positioned. The Basajaun façade constitutes a unitized system, necessitating validation of its performances in accordance with EN 13830 standards for curtain wall façades. The conducted test, specific to this technological product, entails a comprehensive analysis of norms to discern the extent to which this façade facilitates elevated building performances. Accredited testing facilities, authorized to furnish official test reports for the acquisition of CE certification under EN 13830, have executed the test. The method statement delineating the testing procedures has been meticulously defined, and the sequential arrangement of the tests has been stipulated as follows:

- Air permeability, water penetration resistance, and wind resistance test sequence.

- External and internal impact test sequence for impact with the double tires.

- Deflection gauge verification—based on façade mechanical simulation, the correspondence between the value from the simulation and the one from the test is compared to confirm the theoretical component. The complete list of conducted tests is in Table 9.

Table 9. Method statement of laboratory environment tests—performance tests.

Table 9. Method statement of laboratory environment tests—performance tests.

Figure 10 shows the façade installed, three vision modules on the ground floor, and three opaque modules on the first floor (a), and one of the impact tests performed with the double tire on a glass surface (b).

Figure 10.

Performance mockup test: mockup installed in lab environment before testing activity (a); impact test against vison façade module (b).

The result achieved by the PMU test accomplished all the requirements according to the EN ISO 13830:2005, as shown in Table 10.

Table 10.

Results achieved during EN 13830 testing activities.

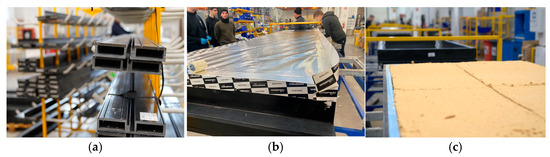

3.2.4. Acoustic Test

The purpose of the acoustic mock-up was to demonstrate the Basajaun façade acoustic insulation performance under the norm EN ISO 717-1:2020 (IN-OUT test). The acoustic mock-up has been designed by considering the dimensions of the acoustic chamber set up in the Tecnalia laboratory where the test was conducted. Four façade modules, each 800 × 2760 mm, were installed into a prefabricated concrete frame 40 cm thick with interior dimensions of 2800 mm high by 3600 mm long, with a surface of wood cladding oriented to the source test room. The gap, in the lateral part, between the acoustic chamber frame and the façade modules was filled by a brick wall with gypsum plasterboard and mineral wool lining on both sides. The test mock-up was mechanically fixed to the perimeter by means of a steel profile and the gap was sealed mainly by mineral wool and joint sealing. Figure 11 shows the vision module acoustic chamber while Figure 12 shows the opaque modules.

Figure 11.

Vision façade picture of test specimen in the test rooms.

Figure 12.

Opaque façade pictures of the test specimen in the test rooms.

The test was conducted in horizontal transmission rooms, which consisted of a source room and a receiving room. The receiving room comprised two separate concrete boxes, each with a thickness of twenty and ten centimeters respectively, designed for acoustic isolation. Conversely, the source room was constructed with a double box featuring a metal frame and gypsum board, also for acoustic isolation. The mobility of the source room facilitated the positioning of the test specimen externally, as well as its subsequent installation between the test rooms. The test’s objective was to obtain the rating according to EN ISO 717-1:2020. Therefore, it was necessary to obtain the sound reduction index, R, for the one-third-octave band from 100 Hz to 5 kHz, according to EN ISO 10140-2:2021 [66]:

R = L1 − L2 + 10 × Log S/A where S: test specimen area; A = 0.16 × V/T

- The average sound pressure level in the source and receiving room, L1 and L2, were measured using a moving microphone with a sweep radius of 1 m and a traverse period of 16 s during 32 s of measure. Background noise in the receiving room was measured according to the same measurement process of the sound field in the receiving room.

- The equivalent sound absorption area, A, in the receiving room was evaluated from the reverberation time measured in the receiving room, T, and from the receiving room volume, V. Reverberation time was determined by using two positions of the sound source and three fixed microphone positions for each source position distributed at 120° in the microphone path. The measurement chain was verified just before and after the execution of the test.

- The rating according to EN ISO 717-1:2020 was calculated from the sound reduction index curve obtained according to EN ISO 10140-2:2021.

- For the vision modules the test was conducted following the EN ISO 10140-2:2021, and the results obtained are (rating according to EN ISO 717-1:2020):

- Rw (C; Ctr): 42 (−2; −6) dB.

- RA = Rw + C100–5000: 41 dB.

- RA, tr = Rw + Ctr,100–5000: 36 dB

- While for the opaque modules the results obtained are (rating according to EN ISO 717-1:2020):

- Rw (C; Ctr): 44 (−2; −7) dB.

- RA = Rw + C100–5000: 43 dB.

- RA, tr = Rw + Ctr,100–5000: 37 dB

4. Discussion

This section synthesizes the key discussions and interconnections regarding the Basajaun project objectives outlined in Section 1. The results obtained during the validation phase revealed that the façade system design aligns with the research objective and expectations mentioned in the introduction. These results demonstrate the effectiveness of implementing various façade typologies, industrialized manufacturing processes, and the use of biocomposites, which converge to create sustainable and innovative building envelope solutions. Regarding the biocomposite profile developments:

- All the conducted tests confirmed a successful outcome—the profile could be a valuable alternative to conventional materials such as aluminum in curtain wall façades. Indeed, considering the production process of the frame profiles, pultrusion consumes less energy per unit weight compared to aluminum profile extrusion, with the biocomposite reducing energy consumption by about 70%. However, Basajaun pultruded profiles weigh nearly twice as much as aluminum profiles with comparable structural properties. At the same time, the assembly of the façades did not show significant variations during the analysis. More detailed insights derived from the sustainability analysis of the façade systems are presented in Morganti et al. [30], offering indicators toward circular, environmentally conscious, and bio-composed building envelopes.

- For the adhesion test between the sealants and biocomposite profile, the aim was to use structural silicone in direct contact with the biocomposite profile to reduce the number of system components. While the test did not fail, for safety reasons and for future building lifespans, the manufacturing has been conducted with an aluminum profile integrated with the bio-component profile to have certainness of the adhesion of structural silicone with glass.

- For the adhesion test between the membrane and biocomposite profiles, the results confirm that the solution may be considered valuable for utilization in the façade, not having achieved failure mode. Conducting durability tests on these systems over an extended period, considering the diverse support structures to which they were affixed, has been a fundamental step. Such evaluations are crucial for ascertaining the long-term effectiveness of these systems as well as their suitability for practical implementation.

- Cutting and machining—due to their characteristics, the biocomposite profiles can be cut and machined by changing the equipment tool, in comparison to the aluminum profiles. However, for further developments a substantial weight reduction needs to be considered to enhance overall economic efficiency.

Regarding the development of bio-based curtain wall façade:

- The Basajaun system tests confirm successful outcomes, including manufacturability of panels, validation of design accuracy with minor adjustments, definition of possible performance levels, adherence to current curtain wall façade standards, and demonstration of the effectiveness of the Basajaun systems in addressing prefabrication challenges while meeting high-performance standards.

- The performance test (PMU) demonstrates that the façade can support the wind load in pressure and suction, and guarantees air permeability and watertightness based on tests according to the standard provided. Table 11 reports the results obtained and the result analysis.

Table 11. Discussion of test results.

Table 11. Discussion of test results. - AMU—The results of the acoustic mock-up are useful to define the acoustic insulation provided by the Basajaun project. Both typologies were validated by in situ tests. Table 12 shows a comparison of the obtained results.

Table 12. Comparison among the results obtained for acoustic tests in different phases.

Table 12. Comparison among the results obtained for acoustic tests in different phases. - The results of the acoustic mock-up, according to EN ISO 717-1:2020, Rw; C; Ctr; C100–5000; Ctr,100–5000, are necessary to estimate the acoustic behavior of the rooms of a building, R’w. Once the building is executed, an in situ test is carried out to validate R’w against the established requirement. Table 11 shows that the in situ measured results improve the simulation results and are much higher than the requested requirements.

- It is very important to have reliable data of enclosures, especially in new systems, to obtain adequate estimation data and be able to satisfy the established requirements.

However, further activities need to be conducted with the aim to investigate additional characteristics and implement the façade system:

- Sealant test—once defined, the finishing of the window (architectural choice ongoing by UNSTUDIO and demo partner); a final approval on dark finish (T17 EBANO) for the wooden frame is pending.

- Implementation of Basajaun façade typologies—the activities conducted during the Basajaun façade system demonstrate that the system could be adapted for different façade module typologies to be used in a demo building. The next activities regarding the Basajaun façade will be to develop the demo detail design and Basajaun façade manufacturing. In addition, to have the possibility to install the system in the demo building in France (Bordeaux), it was requested by the local architects to fulfill an ATEx procedure (Appreciation Technique d’experimentation) of the entire façade system. All these tests were used as part of this validation process conducted by the CSTB (Centre Scientifique et Technique du Bâtiment) with reference number: 3047_V1.

- Prefabrication process industrialization—the goal of advancing the prefabrication manufacturing process lies in its industrialization to address the construction industry’s needs. This segment looks into assessing the benefits of factory-based manufacturing, encompassing aspects such as cost efficiency, quality control, and scalability. One aim is to decrease both the weight and thickness of the façade system with a targeted approach towards optimizing biocomposite profiles, resulting in improved resource efficiency and cost savings. Indeed, Basajaun pultruded profiles weigh nearly twice as much as aluminum profiles with comparable structural properties.

5. Conclusions

The above-mentioned activities demonstrated that the Basajaun façade system design is successfully aligned with the stipulated objectives and requirements of the research, demonstrating accomplishments in several key areas. The validation phase highlights that the designed Basajaun façade system is in line with current building envelope standards for curtain wall façade solutions. Indeed, the results obtained addressed all the assessing criteria defined by the curtain wall standards, demonstrating the feasibility of replacing standard components with bio-based ones. These results represent an important achievement in taking a step further in the introduction of bio-based materials in the construction sector.

Moreover, the focus on industrialization allows for off-site manufacturing, with on-site installation limited to brackets and base profiles, ensuring scalability and reproducibility as well as reducing the construction site time and costs.

The prototyping and testing activities validated these outcomes and explored the broader applicability of the Basajaun façade within wood-based products in the construction value chain.

Beyond the achievements obtained by the Basajaun façade system, further steps could be made with the aim to improve the façade system and its marketability:

- To further validate the Basajaun façade system design and demonstrate its applicability in pilot buildings (located in France and Finland), we will develop the pilot detail design to investigate its impact on real-case manufacturing,

- To tackle all the defined weak points,

- To enhance the proportion of bio-based components in the profiles, with a specific emphasis on the resin content, to contribute to a more sustainable and environmentally friendly product,

- To develop the market validation which is missing and should be conducted once the bio-based profile is able to reduce its manufacturing costs.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.P. and L.V.; methodology, A.P., L.V. and J.A.L.; validation, A.P., L.V., J.A.L. and A.N.M.; formal analysis, A.P., L.V. and A.N.M.; investigation, A.P., L.V. and A.N.M.; resources, L.V., A.N.M. and S.L.d.A.E.; data curation, S.L.d.A.E., L.V. and A.N.M.; writing—original draft preparation, A.P. and L.V.; writing—review and editing, L.V., A.P., S.L.d.A.E., A.N.M. and J.A.L.; visualization, L.V., S.L.d.A.E. and A.N.M.; supervision, A.P. and J.A.L.; project administration A.P. and J.A.L.; funding acquisition, A.P. and J.A.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the European Project H2020 “BASAJAUN” under grant agreement no. 862942.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study that are not cited in the reference section are available upon request from the corresponding author, with the permission of third parties. The data are not publicly available due to third parties’ privacy regulations.

Acknowledgments

The results and the study described here are part of the results obtained in the BASAJAUN project: “Building a Sustainable Joint between Rural and Urban Areas through Circular and Innovative Wood Construction Value Chains” (2019–2024). This information reflects only the authors’ views and neither the Agency nor the Commission are responsible for any use that may be made of the information contained therein. The EC CORDIS website is https://cordis.europa.eu/project/id/862942 (accessed on 29 January 2024). The authors express their gratitude to Michelangelo Strocchi for his invaluable support and dedication to the design and validation of the Basajaun façade system during his tenure at Focchi S.p.A. Unipersonale.

Conflicts of Interest

This information only reflects the authors’ views and neither the Agency nor the Commission are responsible for any use that may be made of the information contained herein. The authors declare that they have no financial interests or personal relationships that could have influenced the work presented in this article.

References

- United Nations Environment Programme. 2022 Global Status Report for Building and Construction. 2022. Available online: https://www.unep.org/resources/publication/2022-global-status-report-buildings-and-construction (accessed on 26 February 2024).

- Buildings and Construction—European Commission. Available online: https://single-market-economy.ec.europa.eu/industry/sustainability/buildings-and-construction_en (accessed on 8 March 2024).

- Malabi Eberhardt, L.C.; Rønholt, J.; Birkved, M.; Birgisdottir, H. Circular Economy Potential within the Building Stock—Mapping the Embodied Greenhouse Gas Emissions of Four Danish Examples. J. Build. Eng. 2021, 33, 101845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. The European Green Deal—Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the European Council, the Council, the European Economic and Social Commitee and the Committe of the Regions 2019. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=COM%3A2019%3A640%3AFIN (accessed on 21 March 2024).

- Biomaterials Technology and Policies in the Building Sector: A Review|Environmental Chemistry Letters. Available online: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10311-023-01689-w (accessed on 8 March 2024).

- Yadav, M.; Agarwal, M. Biobased Building Materials for Sustainable Future: An Overview. Mater. Today Proc. 2021, 43, 2895–2902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pörtner, H.-O.; Roberts, D.; Tignor, M.; Poloczanska, E.; Mintenbeck, K.; Alegría, A.; Craig, M.; Langsdorf, S.; Löschke, S.; Möller, V.; et al. Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability Working Group II Contribution to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. 2022. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/362431678_Climate_Change_2022_Impacts_Adaptation_and_Vulnerability_Working_Group_II_Contribution_to_the_Sixth_Assessment_Report_of_the_Intergovernmental_Panel_on_Climate_Change (accessed on 21 March 2024).

- Ratiarisoa, R.; Magniont, C.; Ginestet, S.; Oms, C.; Escadeillas, G. Assessment of Distilled Lavender Stalks as Bioaggregate for Building Materials: Hygrothermal Properties, Mechanical Performance and Chemical Interactions with Mineral Pozzolanic Binder. Constr. Build. Mater. 2016, 124, 801–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinod, A.; Sanjay, M.; Suchart, S.; Jyotishkumar, P. Renewable and Sustainable Biobased Materials: An Assessment on Biofibers, Biofilms, Biopolymers and Biocomposites. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 258, 120978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, D.; Ormondroyd, G.O.; Curling, S.F.; Popescu, C.-M.; Popescu, M.-C. 2—Chemical Compositions of Natural Fibres. In Advanced High Strength Natural Fibre Composites in Construction; Fan, M., Fu, F., Eds.; Woodhead Publishing: Sawston, UK, 2017; pp. 23–58. ISBN 978-0-08-100411-1. [Google Scholar]

- Leszczyszyn, E.; Heräjärvi, H.; Verkasalo, E.; Garcia-Jaca, J.; Araya-Letelier, G.; Lanvin, J.-D.; Bidzińska, G.; Augustyniak-Wysocka, D.; Kies, U.; Calvillo, A.; et al. The Future of Wood Construction: Opportunities and Barriers Based on Surveys in Europe and Chile. Sustainability 2022, 14, 4358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carcassi, O.B.; Paoletti, I.; Malighetti, L.E. Reasoned Catalogue of Biogenic Products in Europe. An Anticipatory Vision between Technical Potentials and Availability. J. Technol. Archit. Environ. 2021, 63–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh, G. Circular Bio-Economy—Paradigm for the Future: Systematic Review of Scientific Journal Publications from 2015 to 2021. Circ. Econ. Sustain. 2022, 2, 231–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephenson, P.J.; Damerell, A. Bioeconomy and Circular Economy Approaches Need to Enhance the Focus on Biodiversity to Achieve Sustainability. Sustainability 2022, 14, 10643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galimshina, A.; Moustapha, M.; Hollberg, A.; Padey, P.; Lasvaux, S.; Sudret, B.; Habert, G. Bio-Based Materials as a Robust Solution for Building Renovation: A Case Study. Appl. Energy 2022, 316, 119102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pracucci, A.; Magnani, S.; Vandi, L.; Casadei, O.; Uriarte, A.; Bueno, B.; Vavallo, M. An Analytical Approach for the Selection of Technologies to Be Integrated in a Plug&play Façade Unit: The RenoZEB Case Study. In Proceedings of the 8th Annual International Sustainable Places Conference (SP2020), Online, 27–30 October 2020; p. 29. [Google Scholar]

- Shan, R.; Junghans, L. Multi-Objective Optimization for High-Performance Building Facade Design: A Systematic Literature Review. Sustainability 2023, 15, 15596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Košir, M. Adaptive Building Envelope: An Integral Approach to Indoor Environment Control in Buildings. In Automation and Control Trends; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2016; pp. 121–147. ISBN 978-953-51-2671-3. [Google Scholar]

- Ascione, F.; Bianco, N.; De Masi, R.F.; Mauro, G.M.; Vanoli, G.P. Design of the Building Envelope: A Novel Multi-Objective Approach for the Optimization of Energy Performance and Thermal Comfort. Sustainability 2015, 7, 10809–10836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Building Envelope Design Guide—Introduction|WBDG—Whole Building Design Guide. Available online: https://www.wbdg.org/guides-specifications/building-envelope-design-guide/building-envelope-design-guide-introduction (accessed on 8 March 2024).

- Sandak, A.; Sandak, J.; Brzezicki, M.; Kutnar, A. Biomaterials for Building Skins. In Bio-Based Building Skin; Sandak, A., Sandak, J., Brzezicki, M., Kutnar, A., Eds.; Environmental Footprints and Eco-design of Products and Processes; Springer: Singapore, 2019; pp. 27–64. ISBN 9789811337475. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, D. Introduction to the Performance of Bio-Based Building Materials. In Performance of Bio-Based Building Materials; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2017; pp. 1–19. ISBN 978-0-08-100982-6. [Google Scholar]

- Tam, V.; Hao, J. Prefabrication as a Mean of Minimizing Construction Waste on Site. Int. J. Constr. Manag. 2014, 14, 113–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernando, D.; Navaratnam, S.; Rajeev, P.; Sanjayan, J. Study of Technological Advancement and Challenges of Façade System for Sustainable Building: Current Design Practice. Sustainability 2023, 15, 14319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atsonios, I.; Katsigiannis, E.; Koklas, A.; Kolaitis, D.; Founti, M.; Mouzakis, C.; Tsoutis, C.; Adamovský, D.; Colom, J.; Philippen, D.; et al. Off-Site Prefabricated Hybrid Façade Systems: A Holistic Assessment. J. Facade Des. Eng. 2023, 11, 097–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BASAJAUN|Horizon. 2020. Available online: https://basajaun-horizon.eu/ (accessed on 8 March 2024).

- BASAJAUN—Building A Sustainable Joint between Rural and Urban Areas through Circular and Innovative Wood Construction Value Chains|BASAJAUN Project|Fact Sheet|H2020. Available online: https://cordis.europa.eu/project/id/862942/it (accessed on 11 January 2024).

- CZU OSIRIS. OSIRIS. Available online: https://osiris4r.eu/czuypard/ (accessed on 8 March 2024).

- Forest Based Composites for Facade and Interior Partitions to Improve Indoor Air Quality in New Builds and Restoration|Osirys Project. Available online: https://cordis.europa.eu/project/id/609067 (accessed on 11 January 2024).

- Morganti, L.; Vandi, L.; Astudillo Larraz, J.; García-Jaca, J.; Navarro Muedra, A.; Pracucci, A. A1–A5 Embodied Carbon Assessment to Evaluate Bio-Based Components in Façade System Modules. Sustainability 2024, 16, 1190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pracucci, A.; Vandi, L.; Morganti, L.; Fernández, A.G.; Diaz, M.N.; Muedra, A.N.; Győri, V.; Kouyoumji, J.-L.; Larraz, J.A. Design and Simulation for Technological Integration of Bio-Based Components in Façade System Modules 2024. Available online: https://www.preprints.org/manuscript/202403.1552/v1 (accessed on 26 March 2024).

- Pavatex Sa PAVAFLEX Flexible Woodfibre Insulation Material (EPD) 2014. Available online: https://www.lifepanels.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/2.-PAVAFLEX-PLUS-Environmental-Product-Declaration-EPD.pdf (accessed on 8 March 2024).

- EN 13501-1:2018; Fire Classification of Construction Products and Building Elements—Part 1: Classification Using Data from Reaction to Fire Tests. Available online: https://standards.iteh.ai/catalog/standards/cen/4badd874-3b6b-4c82-92b8-63184ae52b81/en-13501-1-2018 (accessed on 7 April 2024).

- EN 13830:2003; Curtain Walling—Product Standard. Available online: https://standards.iteh.ai/catalog/standards/cen/51c14384-e4c8-49ba-8658-6aac20f9ae1f/en-13830-2003 (accessed on 3 April 2024).

- EN 13830-2020; CEN—Comitè Europeen de Normalisation Curtain Walling. Products Standards. CEN: Brussels, Belgium, 2022.

- EN 14019:2016; Curtain Walling—Impact Resistance—Performance Requirements. Available online: https://standards.iteh.ai/catalog/standards/cen/1bfe4fa0-6bf4-4ae7-b2a2-0a87ced89e0d/en-14019-2016 (accessed on 12 February 2024).

- ISO 717-1:2020; Acoustics—Rating of Sound Insulation in Buildings and of Building Elements—Part 1: Airborne Sound Insulation. Available online: https://www.iso.org/obp/ui/#iso:std:iso:717:-1:ed-4:v1:en:tab:1 (accessed on 28 March 2024).

- EN 13706-2:2002; Reinforced Plastics Composites—Specifications for Pultruded Profiles—Part 2: Methods of Test and General Requirements. 2002. Available online: https://standards.iteh.ai/catalog/standards/cen/d140c1cb-a417-427d-b3d8-e3cd6329214c/en-13706-2-2002 (accessed on 7 April 2024).

- EN 13706-3:2002; Reinforced Plastics Composites—Specifications for Pultruded Profiles—Part 3: Specific Requirements. 2002. Available online: https://standards.iteh.ai/catalog/standards/cen/a9ce34d6-81c7-495e-8b69-fe4365448e6f/en-13706-3-2002 (accessed on 7 April 2024).

- ISO 527-4:2021; Plastics — Determination of Tensile Properties — Part 4: Test Conditions for Isotropic and Orthotropic Fibre-Reinforced Plastic Composites. Available online: https://standards.iteh.ai/catalog/standards/iso/c08bf202-523f-49f0-9df7-3a7b7bdf241c/iso-527-4-2021 (accessed on 7 April 2024).

- EN ISO 14125:1998/A1:2011; Fibre-Reinforced Plastics Composites. Determination of Flexural Properties. Available online: https://standards.iteh.ai/catalog/standards/cen/d9fe41aa-2c62-481b-bd6a-f9b1e24e51af/en-iso-14125-1998-a1-2011 (accessed on 7 March 2024).

- ISO 14130:1999; Fibre-Reinforced Plastic Composites—Determination of Apparent Interlaminar Shear Strength by Short-Beam Method (ISO 14130:1997). Available online: https://standards.iteh.ai/catalog/standards/sist/b8dd8640-9d6f-4a34-9eee-fbbe46338ed6/sist-en-iso-14130-1999 (accessed on 7 March 2024).

- EN ISO 527-4:1997; Plastics—Determination of Tensile Properties—Part 4: Test Conditions for Isotropic and Orthotopic Fibre-reinforced Plastic Composites. Available online: https://standards.iteh.ai/catalog/standards/cen/e0399dfa-d7ee-45a1-bcc9-48036ff46aa0/en-iso-527-4-1997 (accessed on 7 April 2024).

- EN ISO 14125:1999/A1:2014; Fibre-Reinforced Plastic Composites—Determination of Flexural Properties—Amendment 1 (ISO 14125:1998/Amd 1:2011). Available online: https://standards.iteh.ai/catalog/standards/sist/bb07f8e0-cdd1-4741-bb23-5ef7d1b0af7e/sist-en-iso-14125-1999-a1-2014 (accessed on 7 March 2024).

- EN ISO 14126:2001 + AC:2002; Fibre-Reinforced Plastic Composites—Determination of Compressive Properties in the in-Plane Direction (ISO 14126:2023). Available online: https://standards.iteh.ai/catalog/standards/cen/0f0c3d17-b11e-4a9b-b939-4bde39ba5186/en-iso-14126-2023 (accessed on 7 March 2024).

- EN ISO 179-1:2011; Plastics—Determination of Charpy Impact Properties—Part 1: Non-instrumented impact test (ISO 179-1:2023). Available online: https://standards.iteh.ai/catalog/standards/cen/412dad73-2eb8-40e9-9284-a281d0627f5d/en-iso-179-1-2023 (accessed on 7 March 2024).

- EN ISO 1172:1999; Textile-Glass-Reinforced Plastics—Prepregs, Moulding Compounds and Laminates—Determination of the Textile-Glass and Mineral-Filler Content Using Calcination Methods (ISO 1172:2023). Available online: https://standards.iteh.ai/catalog/standards/cen/3ac7a016-1928-4c16-9689-7b19a713fc1e/en-iso-1172-2023 (accessed on 7 March 2024).

- EN ISO 11664-4:2020; Colorimetry—Part 4: CIE 1976 L*a*b* Colour Space (ISO 11664-4:2008). Available online: https://standards.iteh.ai/catalog/standards/cen/e5f1f2d6-55ff-4e12-90e3-b6765ed35f7d/en-iso-11664-4-2011 (accessed on 7 March 2024).

- ISO 11359-2:2021; Plastics—Thermomechanical Analysis (TMA)—Part 2: Determination of Coefficient of Linear Thermal Expansion and Glass Transition Temperature. Available online: https://standards.iteh.ai/catalog/standards/iso/1ceb0272-bb4f-4eab-bbb5-c6f4466dad03/iso-11359-2-2021 (accessed on 7 March 2024).

- EN 59:2016; Glass Reinforced Plastics—Determination of Indentation Hardness by Means of a Barcol Hardness Tester. Available online: https://standards.iteh.ai/catalog/standards/cen/6bf6881f-55de-4956-9f60-1bd12e82d160/en-59-2016 (accessed on 7 March 2024).

- EN ISO 175:2011; Plastics—Methods of Test for the Determination of the Effects of Immersion in Liquid Chemicals (ISO 175:2010). Available online: https://standards.iteh.ai/catalog/standards/sist/ff26c9ce-af43-4497-9167-cde7e2abaf21/sist-en-iso-175-2011 (accessed on 7 March 2024).

- EN ISO 1183-1:2019; Plastics—Methods for Determining the Density of Non-Cellular Plastics—Part 1: Immersion method, Liquid Pycnometer Method and Titration Method (ISO 1183-1:2019, Corrected version 2019-05). Available online: https://standards.iteh.ai/catalog/standards/cen/0700b7c3-ff8f-4538-bb89-d9f8c34aba7d/en-iso-1183-1-2019 (accessed on 7 March 2024).

- ISO 4611:2011; Plastics. Determination of the Effects Of Exposure to Damp Heat, Water Spray and Salt Mist (ISO 4611:2010). Available online: https://standards.iteh.ai/catalog/standards/iso/34644c9c-6a8e-4c64-bf64-60b41855c7b9/iso-4611-2010 (accessed on 7 March 2024).

- EN12316-2:2013; Flexible Sheets for Waterproofing—Determination of Peel Resistance of Joints—Part 2: Plastic and Rubber Sheets for Roof Waterproofing. Available online: https://standards.iteh.ai/catalog/standards/cen/dd325991-86f9-47ac-9ec7-b5c380367c4c/en-12316-2-2013 (accessed on 7 April 2024).

- EN 12317-2:2011; Flexible Sheets for Waterproofing—Determination of Shear Resistance of Joints—Part 2: Plastic and Rubber Sheets for Roof Waterproofing. Available online: https://standards.iteh.ai/catalog/standards/cen/1afa7b84-c683-4718-8f5b-c5da65834632/en-12317-2-2010 (accessed on 7 March 2024).

- EN 13859-2:2014; Flexible Sheets for Waterproofing—Definitions and Characteristics of Underlays—Part 2: Underlays for Walls. Available online: https://standards.iteh.ai/catalog/standards/cen/2f716e45-d2a9-4c73-9312-e24f43949552/en-13859-2-2014 (accessed on 7 April 2024).

- ASTM C1087; Standard Test Method for Determining Compatibility of Liquid-Applied Sealants with Accessories Used in Structural Glazing Systems. Available online: https://www.astm.org/c1087-16.html (accessed on 8 March 2024).

- European Organization for Technical Approvals Guideline for European Technical Approval for Structural Sealant and Glazing Kits (SSGK) 2012. Available online: https://standards.iteh.ai/catalog/standards/cen/ab460e27-bfd2-4f52-8fc3-9d46b595dc8c/en-13706-1-2002 (accessed on 8 March 2024).

- Standard Test Method for Adhesion-in-Peel of Elastomeric Joint Sealants. Available online: https://www.astm.org/c0794-18r22.html (accessed on 8 March 2024).

- EN 12153; Curtain Walling—Air Permeability—Test Method. Available online: https://standards.iteh.ai/catalog/standards/cen/f009e1a5-1cdf-476b-96e6-b6d5e310175e/en-12153-2023 (accessed on 7 March 2024).

- EN 12152; Curtain Walling—Air Permeability—Performance Requirements and Classification. Available online: https://standards.iteh.ai/catalog/standards/sist/88f492b7-2d45-4d48-8fa4-6a01e83b8d80/sist-en-12152-2023 (accessed on 7 March 2024).

- EN 12155; Curtain Walling—Watertightness—Laboratory Test under Static Pressure. Available online: https://standards.iteh.ai/catalog/standards/cen/0dcfdd01-d664-41f7-a1b5-b6ff773a7878/en-12155-2000 (accessed on 7 March 2024).

- EN 12154; Curtain Walling—Watertightness—Performance Requirements and Classification. Available online: https://standards.iteh.ai/catalog/standards/cen/16342422-5f8f-4cd0-be67-d4092058f426/en-12154-1999 (accessed on 7 March 2024).

- EN 12179; Curtain Walling—Resistance to Wind Load—Test Method. Available online: https://standards.iteh.ai/catalog/standards/cen/c0bd3670-98a2-4eb8-9764-5e970f97de83/en-12179-2000 (accessed on 7 March 2024).

- EN 13116; Curtain Walling—Resistance to Wind Load—Performance Requirements. Available online: https://standards.iteh.ai/catalog/standards/cen/2eff39ca-0b83-4d48-9bbd-4f902d3c0eb6/en-13116-2024 (accessed on 7 March 2024).

- EN ISO 10140-2:2021; Acoustics—Laboratory Measurement of Sound Insulation of Building Elements—Part 2: Measurement of Airborne Sound Insulation. Available online: https://standards.iteh.ai/catalog/standards/cen/c13c521e-fd0b-40bd-a323-f48ed7d3de55/en-iso-10140-2-2021 (accessed on 7 April 2024).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).