Abstract

Accelerated urbanization has led to regional disruptions and exacerbated imbalances in spatial quality, social cohesion, and inequalities. Urban regeneration, as a mitigating strategy for these disruptions, faces significant social challenges, particularly at the community scale. This study addresses the existing research gap by comprehensively reviewing community regeneration (CR) from a socially sustainable perspective (SSP). Utilizing VOSviewer software, we synthesize and categorize relevant research trends and methods spanning from 2006 to 2023, retrieving 213 coded articles among 5002 relevant documents from Web of Science bibliometric datasets. The study explores the implementation trajectory of CR, considering novel scenario demands, emerging technologies, and new development paradigms and approaches. It delves into human-centric approaches to enhance the quality of life, precision, and diversification of community engagement and cultivate a sense of community equity and belonging. Moreover, the findings highlight densification as a synergistic and adaptive strategy for current regeneration actions. This scientometric review leverages new tools and innovative approaches for regeneration policy and planning decision-making, ultimately contributing to the improvement of livability. The study provides valuable insights into the challenges and opportunities associated with socially sustainable CR, offering a foundation for future research, and guiding practical urban planning and design interventions.

1. Introduction

The phenomenon of accelerated urbanization has resulted in regional disruptions, necessitating urban regeneration as a crucial driving force for revitalizing the built environments and achieving high-quality development. This involves optimizing subjective well-being, spatial quality, and urban configuration [1,2]. Notably, these means and objectives are consistent with the 11th Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) outlined in the 2030 UN Agenda, which is sustainable cities and communities, emphasizing the promotion of inclusivity, safety, resilience, and sustainability in urban and human settlements [3]. Against this backdrop, research on sustainable community development has emerged, encompassing various perspectives, such as policy formulation, planning and design intervention, community governance, public participation, and stakeholder interests [4]. These studies reflect the diversity and complexity within the regeneration field at the community level, arousing broader attention to optimal practices for enhancing urban sustainability and residents’ quality of life (QoL), to mediate the disruptions caused by rapid urbanization and align with the 11th SDG [5].

Indeed, the regeneration process has long been controversial, and the regeneration procedural aspects easily trigger societal fragmentation, gentrification, and various social inequalities [6]. To achieve the 11th SDG and mediate the disputes, social sustainability emerges as a perspective capable of comprehensively addressing these societal issues at the community level, placing considerable emphasis on resident engagement and providing equitable opportunities, enhancing the residential sense of belonging and improving QoL substantially [7,8]. These strategies are strategically positioned to tackle conflicts of interest among diverse stakeholders and confront the obstacles impeding physical spatial revitalization, which often fall short of meeting functional demands [9]. This includes reconciling the paradox of substandard community spaces through implementing multi-tiered, medium-scale green infrastructure initiatives, exemplified by community gardens and pocket parks [10]. Moreover, they encompass endeavors to redress disparities in community equity through the provision of top-tier public services, enhancement of infrastructure, bolstering community cultural initiatives, and fostering ongoing educational opportunities, among other interventions [11]. It does so by gauging the enduring willingness of the populace to reside and work within a community, continually elevating the demands for improvements in the living environment to enhance the overall QoL [12]. Therefore, a perspective rooted in social sustainability becomes particularly pivotal in evaluating the effectiveness of regeneration policies and planning strategies at the community level [13].

Notably, the literature has divergent perspectives on the evolution of sustainable community regeneration (SCR). As urban areas expand and population agglomeration intensifies, SCR has transcended resource-centric considerations [14]. The focus on sustainability has evolved to encompass a broader dimension, including community health, environmental quality, and spatial justice [15]. Social sustainability indicates the ability of a community to achieve long-term interactive collaboration and cultural development while meeting the diverse needs of different groups. Generally, socially sustainable communities can be defined as places where people want to live and work in the future [16]. The literature indicates that social sustainability is an open and dynamic concept, subject to change over time within a given locality [17]. Various disciplines within the social sciences, such as sociology, geography, anthropology, and urban studies, engage in discussions on this concept from different perspectives, including the relationship between democracy and fairness with social sustainability, and the link between urban development and social sustainability [18]. In recent years, scholars in global contexts have explored urban regeneration models with the community as the focal point and the aim of enhancing residents’ QoL. Cities such as London, Vancouver, and Adelaide have actively promoted social integration, improved community livability, and enhanced community service quality at the community level [19]. In this process, different theoretical foundations and assessment methods for social sustainability have gradually become more diversified [20]. Building upon this, some scholars have proposed a triple model of social sustainability, which includes “development sustainability,” addressing basic needs, fostering social capital, justice, and fairness; “bridging sustainability,” facilitating behavioral changes to achieve biophysical environmental goals; “maintaining sustainability,” maintaining or sustaining socio-cultural characteristics in the face of change, and the ways in which people actively accept or resist these changes [21]. In general, socially sustainable development requires support from both the environment and the economy. It should emphasize economic development and environmental protection while respecting and preserving cultural diversity. Additionally, through means such as equity and participation, it should promote the involvement and cooperation of members of society.

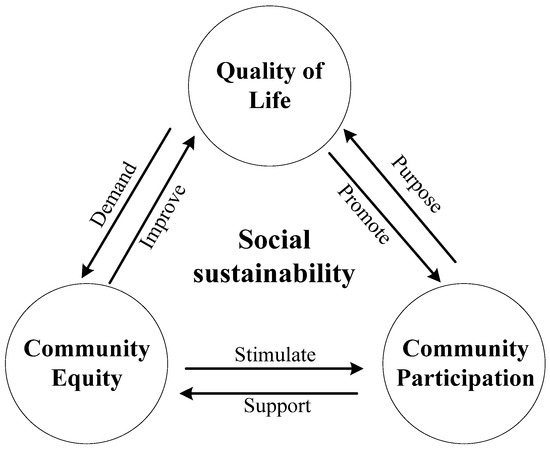

Based on the interpretation and literature synthesis ahead, the manifestation of social sustainability at the community scale can be summarized into three aspects: social equity, social capital, and social inclusion [22,23]. As defined by Caulfield, social sustainability encapsulates communities’ capacity to autonomously enhance and improve [24], representing a crucial strategy for urban regeneration [25]. Socially sustainable regeneration focuses on improving the QoL, enhancing social participation and equity, and promoting community development [13,16,26]. Scholars have delved into socially sustainable development’s nuanced characteristics and connotations, contending that its essence lies in cultivating “quality of life” within urban communities [27,28]. This involves a concerted effort to ameliorate community housing and the built environment by understanding residents’ needs and bolstering their engagement in community activities.

Although, community regeneration (CR) decision-making notices the importance of enhancing residents’ living standards, promoting social engagement, and assuring social equity [29]. However, it is still difficult to implement and achieve these objectives under current CR actions, as it transcends the mere physical upgrading of urban existing stock, and it also represents a multifaceted social engineering endeavor [30]. Addressing these challenges necessitates a comprehensive systematic review and bibliometric investigation of CR from the social sustainability perspective (SSP) [31,32]. Therefore, this paper aims to employ Visualizing Scientific Landscapes (VOSviewer) software to systematically analyze research conducted between 2006 and 2023 concerning CR from the SSP [33,34]. With a specific focus on QoL, social participation, and social equity, it intends to synthesize research content, methodologies, and implementation approaches and tools. Moreover, it aims to elucidate current research trends, providing insights and references for subsequent studies, thereby fostering a more profound and comprehensive understanding of CR from the SSP.

2. Methods and Data

VOSviewer is an open-source tool for visualizing and analyzing scientific literature. This tool allows users to explore key themes, authors, institutions, and other information within a literature database [34,35]. It converts a vast amount of literature data into a visual network map, aiding in identifying and analyzing research hotspots and trends. Moreover, by analyzing keywords in the literature, it clusters related topics and fields, assisting in identifying research hotspots and helping researchers better understand core issues and concepts within a specific field. This study used VOSviewer version 1.6.18 software, a visualization software developed by CWTS research institution at Leiden University in the Netherlands, which has certain advantages in topic mining, keyword co-citation, network density clustering, and other aspects, to conduct multidimensional clustering of research on CR from the SSP based on keywords, categories, and references.

Database searches were conducted using the keywords “social sustainability” and “community regeneration” to collect relevant publication data on community regeneration studies from the Web of Science (WoS). Considering that journal articles and book chapters are the most common publication types in the social sciences, the search encompassed journal articles, book chapters, and research papers containing the term “community regeneration” in their titles, abstracts, keyword lists, and full texts. This approach was taken to explore how concepts such as “community regeneration” are utilized not only in scientific articles but also in other formats, such as books and research papers. The study also considered papers containing the term “community regeneration.” All publications other than those in English, such as Spanish, Chinese, Japanese, and French, were excluded, and only English articles were selected for this bibliometric analysis. Additionally, journal indexing was not restricted to SCI Expanded, SSCI, CPCI-SSH, BKCI-SSH, or ESCI.

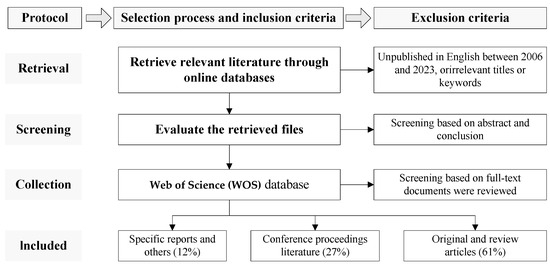

On this basis, the research data were obtained from searches conducted in the WoS core databases, covering papers published between 2006 and 2023. The primary literature type included documents categorized under the theme ‘article.’ The search keywords encompassed Community Regeneration (renewal), Neighborhood Regeneration (renewal), and Sustainability (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Literature search and selection process framework.

3. Results

3.1. Summary Information on the Selected Documents

Evaluate the Retrieved Files: Research Trends

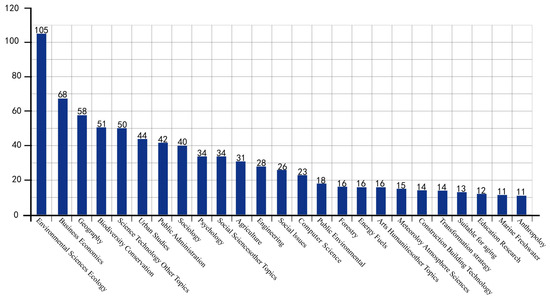

Research on CR globally is equally extensive. As depicted in Figure 2, there were a total of 5002 publications related to urban studies. These publications offer a rich array of research perspectives internationally regarding the CR. On this basis, a total of 213 code articles on CR and well-being from the SSP were screened based on the abstract and conclusion of 5002 related articles. This meticulous selection process aimed to ensure the inclusion of studies that directly addressed the intersection of CR and well-being within the realm of social sustainability.

Figure 2.

Schematic diagram of the relevant articles in the relevant fields.

According to the 213 coded papers on SCR, it was found that the journals published more papers on SCR, including Sustainability, Land Use Policy, Cities, Habitat International, Sustainable Cities and Society, Journal of Environmental Management, etc. As shown in Table 1, the journals with more than 1 paper in this direction were selected for presentation, and it shows the distribution of the 213 papers in different journals.

Table 1.

Overview of selected papers and the relevant journals.

3.2. Research Hotspot Analysis

3.2.1. Analysis of Top 10 Highly Cited Papers

In this study, we identified the top 10 highly cited papers in sustainable urban development and assessed their research focus. Notably, these articles garnered significant attention, with citation frequencies ranging from 19 to 229. The leading paper, authored by Power in 2008 and published in Energy Policy, delves into the intricate connections between urban land and sustainability, accumulating 229 citations. Another influential work by Hull’s article in Transport Policy, with 173 citations, critically examines sustainable transport solutions. Choosing highly cited articles serves to highlight the most representative and impactful research accomplishments within the field, facilitating readers in swiftly grasping its primary research directions and advancements. By delineating 10 highly cited articles, a spectrum of time can be encapsulated, elucidating the developmental trajectory and trends within the field. Simultaneously, considering the constrained length typical of review articles, selecting 10 highly cited articles enables a comprehensive exposition of research progress within the given spatial confines.

The top 10 papers predominantly focus on diverse aspects of sustainable urban development, including environmental viability, policy integration, community-based regeneration, socio-cultural ecosystem services, and social justice. Interestingly, there is evidence of a surge in attention to these topics after 2008, as reflected in the absence of highly cited papers published before that year. Moreover, the publications are distributed across various journals, showcasing the interdisciplinary nature of sustainable urban development research, including Energy Policy, Transport Policy, Sustainability, and more (Table 2).

Table 2.

Top 10 highly cited papers in relevant research.

3.2.2. Social Sustainability as a Cornerstone for CR

Social sustainability represents a multidimensional concept [17], closely intertwined with issues within society, such as economic inequality, social disparities, immigrant settlement, and livability [36,37]. In the CR domain, the boundaries and definition of social sustainability have sparked debates due to its encompassment of various dimensions, including theory, policy, and practice. Over the past decade, numerous scholars have explored social sustainability from diverse perspectives. Some have examined it from a policy standpoint, discussing the relationship between democracy, fairness, and social sustainability [20,38]. Others have focused on the developmental aspects, emphasizing the linkage between community spatial environments and social sustainability [39]. Additionally, viewpoints that underscore participatory entities have brought attention to the societal consequences of community engagement, delving into the social dimensions inherent in urban sustainable transformations [40,41,42]. However, a comprehensive exploration of social sustainability at the community scale remains lacking [25].

In light of the aforementioned discourse, this research organizes representative expositions by global scholars on CR from the SSP, as depicted in Table 1. Early studies concentrated on discussions of social fairness and justice within the community households, with a particular focus on the social interaction and sense of belonging [43]. As urbanization progressed, scholars gradually shifted their attention toward the urban scale of social sustainability, emphasizing public participation and urban governance [44]. Further refinement of social justice research proposed fostering social sustainability through diversification and democratization means [45]. Simultaneously, attention was directed toward individual efforts in pursuing spatial democratization and equalization [46], aiming to enhance residents’ identification with urban culture and thereby augmenting the social sustainability of the revitalization process [47].

In terms of implementation pathways, there has been a growing focus on residents’ QoL, implementation mechanisms, exploring the realization of social fairness and justice from different dimensions, and investigating critical dimensions and strategic approaches to institutional development [26]. These progressively in-depth studies indicate the significance of the SSP in strengthening community revitalization and collaborative governance, enhancing residents’ proactive engagement [48], advocating the development of mixed-use community residence models, promoting multi-level social interactions, and upholding community fairness, inclusivity, and cohesion [49] (Table 3).

Table 3.

Representative academic expositions on CR from the SSP.

In summary, contemporary trends in scholars’ research on CR from the SSP emphasize key aspects, such as community participation, social justice, cultural preservation, fairness, residents’ well-being, and social interactions. By recognizing communities as crucial units, there is a growing consensus that they should prioritize institutional development and implement mechanisms to achieve multidimensional social sustainable development. In essence, the insights derived from this research provide a guideline for policymakers, urban planners, and community leaders to strategically drive social integration and regional synergy. Recognizing the interconnectedness of communities and their influence on broader social dynamics is crucial for fostering sustainable development that transcends individual boundaries and contributes to the overall well-being.

3.3. Bibliometric Networks

3.3.1. Lexical Network

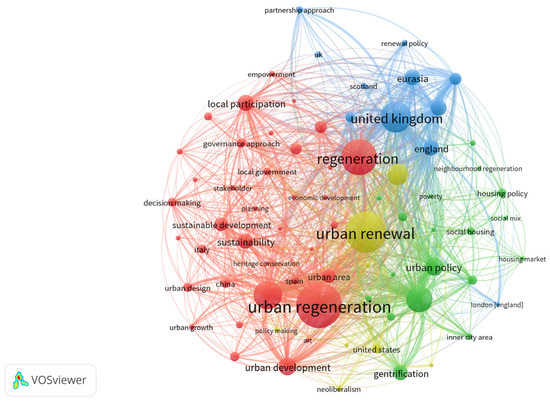

Utilizing VOSviewer software, a vocabulary network was systematically constructed for 213 articles filtered from the Web of Science database based on their keywords and terms. In the keyword co-occurrence analysis, 134 keywords meeting the predefined threshold (minimum co-occurrence frequency of a keyword ≥ 10) were identified out of a total of 916 keywords. The resulting network of keywords and terms was then categorized into four distinct clusters, as illustrated in Figure 3. Each cluster encompasses a curated list of keywords, delineating diverse dimensions and influential factors related to CR. This methodological approach enhances the ability to discern and analyze intricate relationships among key concepts in the field of CR.

Figure 3.

Network of the co-occurrence of literature keywords. Source: WoS datasets, 2024.

Each cluster encompasses a keyword list detailing the determinants influencing community regeneration through the lens of social sustainability. These clusters are distinguished by various colors. In red are pivotal terms central to CR, such as urban design, urban regeneration, urban development, sustainable development, government decision-making, regeneration, local participation, and economic development. In green are keywords related to social sustainability, such as neighborhood regeneration and housing policies, social mix, social welfare housing, poverty, inner-city areas, etc. Light blue denotes keywords associated with community regeneration within social sustainability across different regions, such as the United Kingdom, Eurasia, and Scotland. Yellow represents terms related to urban regeneration, neoliberalism, policy-making, and other relevant concepts.

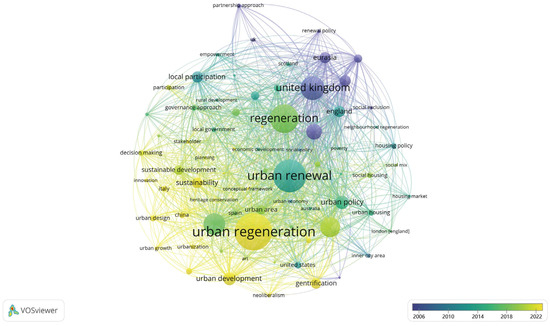

Based on this, using VOSviewer to visually represent the selected literature, where the size of keywords represents their frequency—larger blocks indicate higher frequency—and the color gradient from green to yellow indicates the recency of occurrence, Figure 4 shows the time network of keywords related to community renewal research from the perspective of social sustainability between 2006 and 2023, with most of the research on this topic occurring around 2015–2020.

Figure 4.

Network of the co-occurrence of keywords in the literature from 2006 to 2023. Source: WoS datasets, 2024.

The differentiated analysis of keyword colors and sizes revealed core keywords in recent years, including urban regeneration, projects, life, quality, sustainability, health, and more. Moreover, analyzing the color differentiation between keywords indicated a trend toward a more detailed scale in research related to CR. Urban regeneration based on cities as the fundamental research unit is gradually shifting toward transforming old communities at a micro-community level. Research directions have evolved from age-friendliness and healthy cities to sustainability in CR processes, reshaping spatial vitality and enhancing public service facilities. This indicates an increasing depth of attention from international researchers toward issues in CR, shifting the focus from the urban scale toward the community level, emphasizing sustainability in CR, and enhancing residents’ QoL.

Research on CR has concentrated on key elements, such as QoL, community participation, and community equity. With the continuous emergence and iteration of new technologies and data, the connotations of these three key elements have also expanded to meet the demands of current new scenarios, technologies, and developments [54].

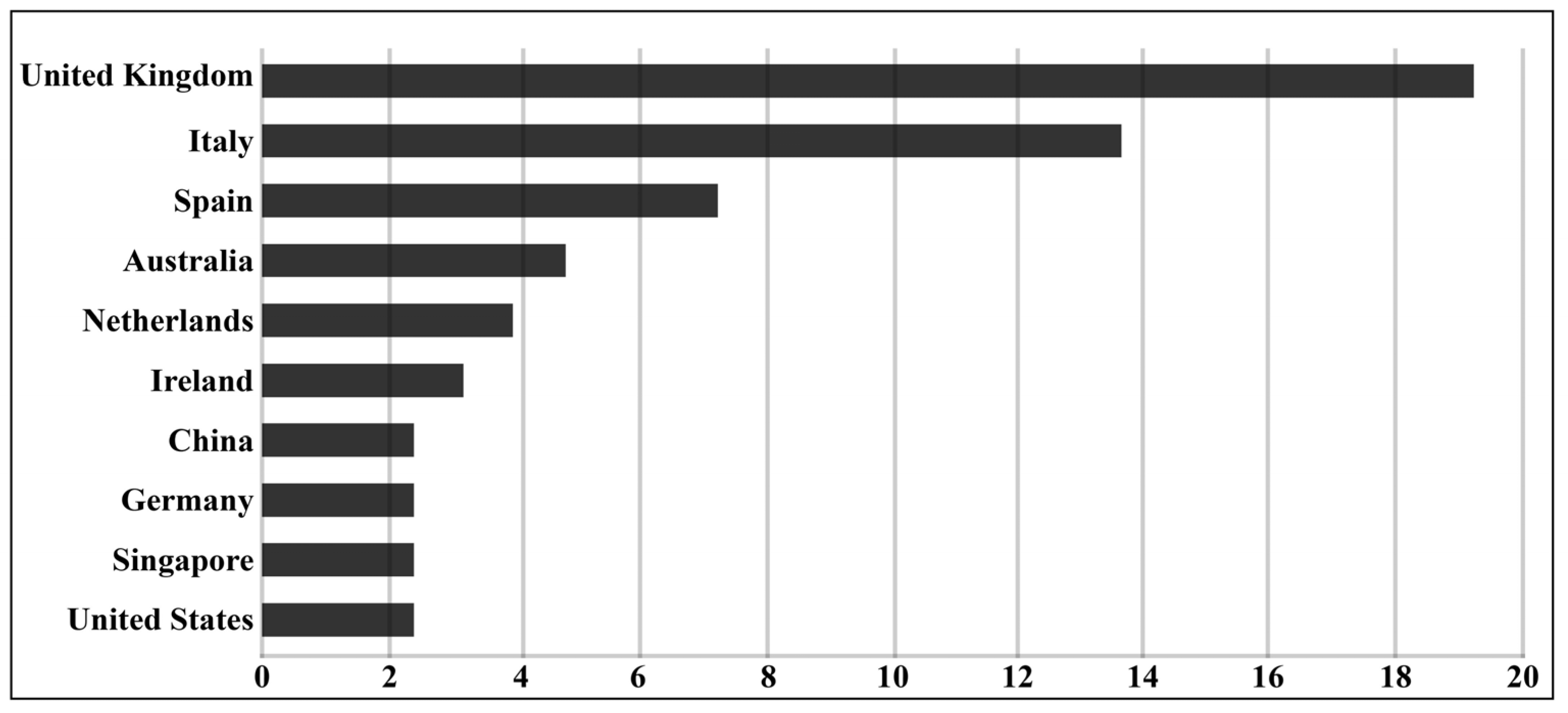

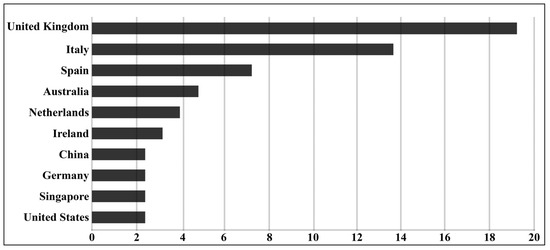

3.3.2. Spatial Network

The spatial network illustrates the geographical connections among the authors of the articles. Among 62 countries, 22 reached the spatial network threshold, defined as having at least 15 documents and zero citations. Figure 5 highlights the top-ten ranking countries. The vertical axis (y) in the figure represents countries, while the horizontal axis (x) represents the percentage of publications from the public sector. The United Kingdom makes the most substantial research contribution to CR from the SSP, accounting for approximately 19.2% of publications. Following closely, Italy ranks second in publication output, contributing 13.8% (see Figure 6).

Figure 5.

Percentage distribution of publications by country. Source: WoS datasets, 2024.

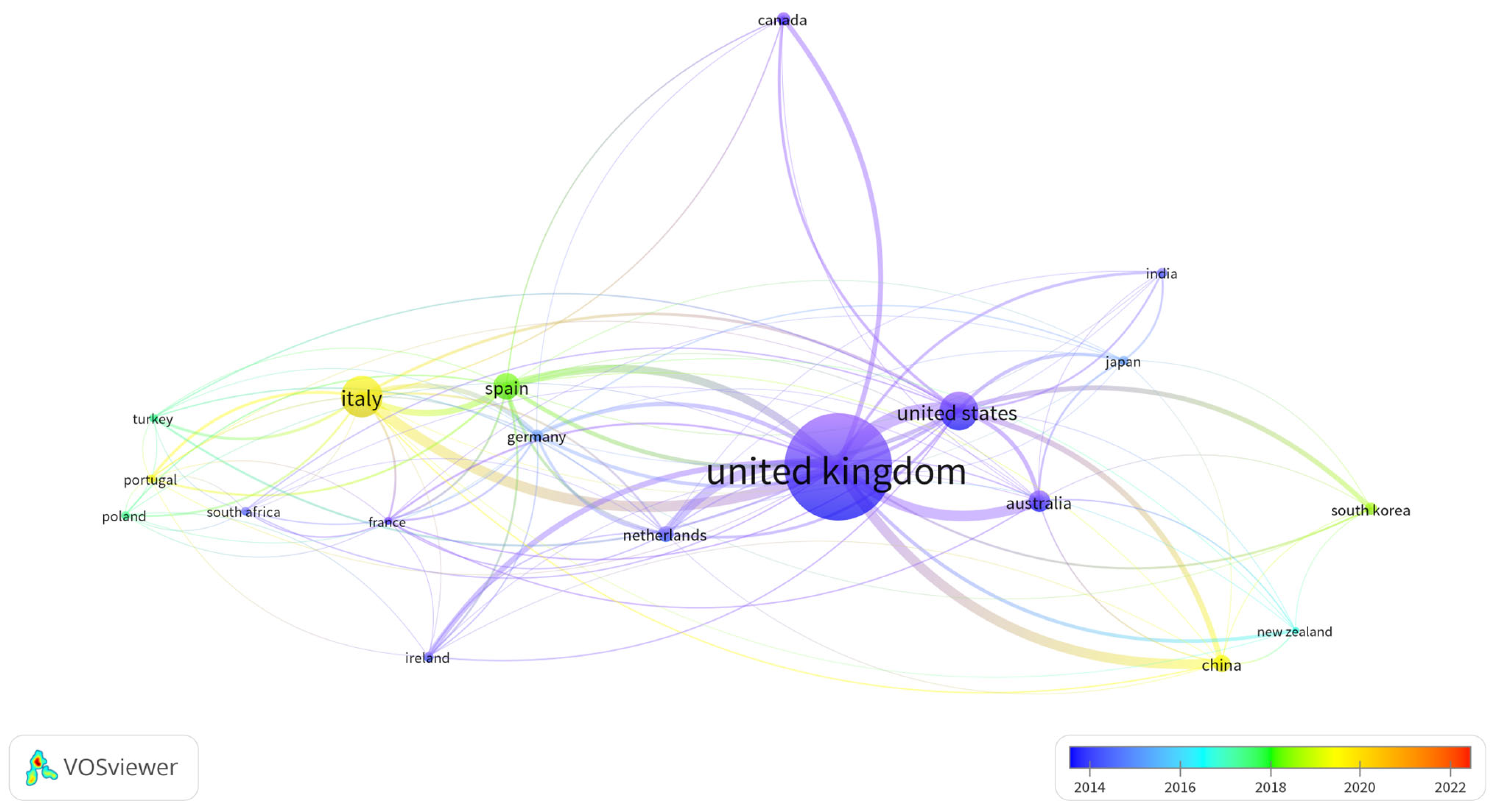

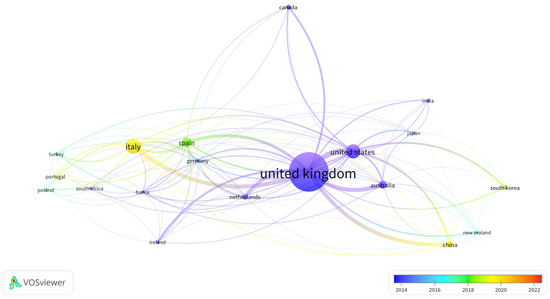

Figure 6.

Temporal network based on number of publications (2014–2023). Source: WoS 2024.

On the flip side, the temporal network analysis presented in Figure 6 delineates the leading nations in CR research from the SSP during the period spanning 2014 to 2022 (with each country contributing a minimum of 10 publications). In this context, the size of nodes corresponds to the frequency of documents originating from each respective country, with larger nodes denoting higher publication frequencies. Nodes, differentiated by color, represent distinct periods over time. Figure 7 reveals that, up until 2014, the leading nations in CR research from the SSP included the United Kingdom, the United States, Japan, Australia, and Canada. Following closely behind were Spain, South Africa, and Turkey, during the period from 2016 to 2018. The visualized network indicates extensive research on CR from the SSP in China post-2018. The thickness of the links in the graph highlights the close connections between China, the United Kingdom, Australia, Italy, the United States, and Spain.

Figure 7.

Citation source network based on the number of publications colored by clusters. Source: WoS 2024.

According to the spatial and temporal networks depicted in Figure 6, it is evident that countries and cities have followed distinct developmental trajectories in CR research. For instance, in the United Kingdom, urbanization and community regeneration processes commenced early, leading to an initial emphasis on community participation and the establishment of resident communities from a social sustainability perspective. Similarly, cities such as Rome and Milan in Italy have played significant roles in CR research, benefiting from their rich historical and cultural traditions, which provide a conducive environment for academic development. In Italy, community regeneration efforts have focused more on land use, community participation, and community management. Furthermore, cities such as Beijing, Shanghai, and Shenzhen in China have emerged as prominent players in the field of CR research in recent years. With increasing research investment and international collaboration, China has become a significant participant in global CR research.

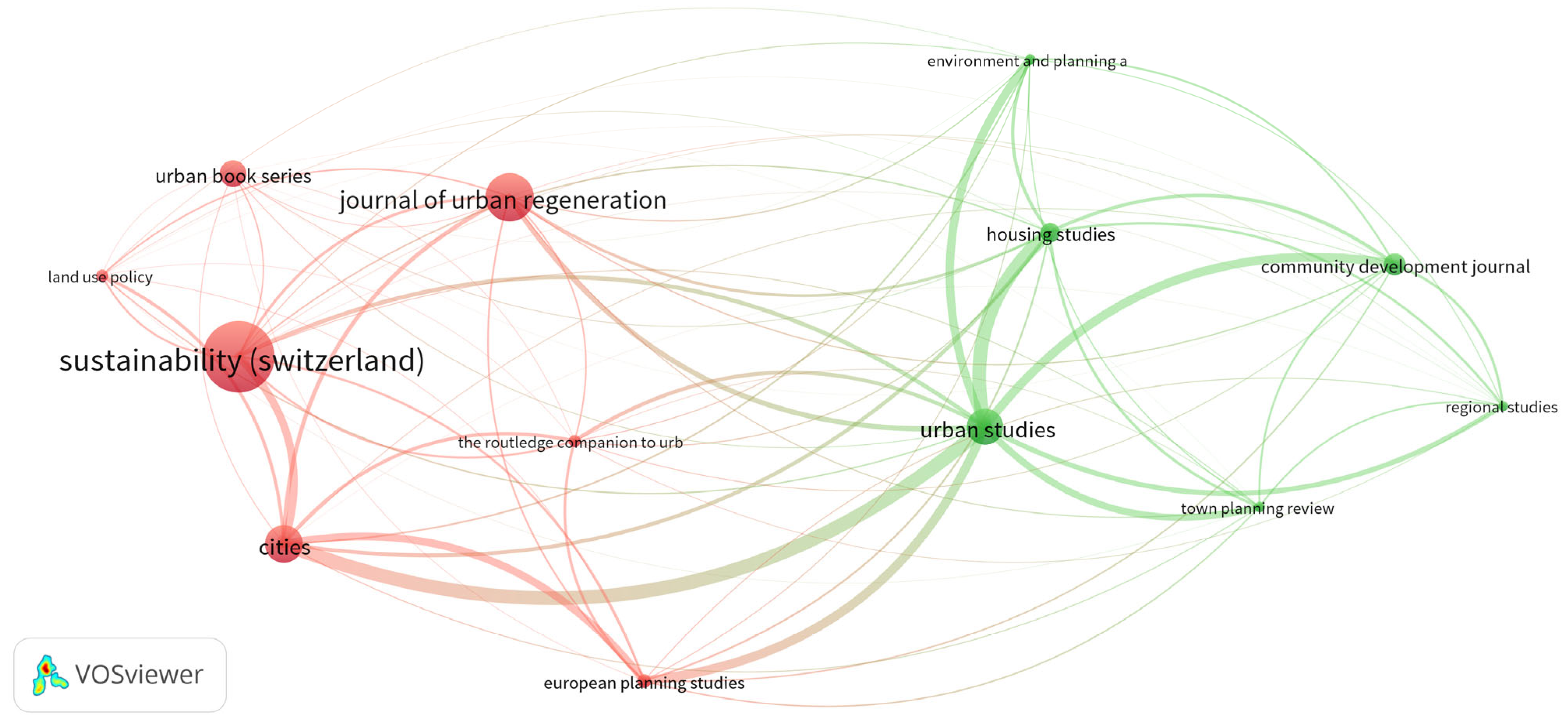

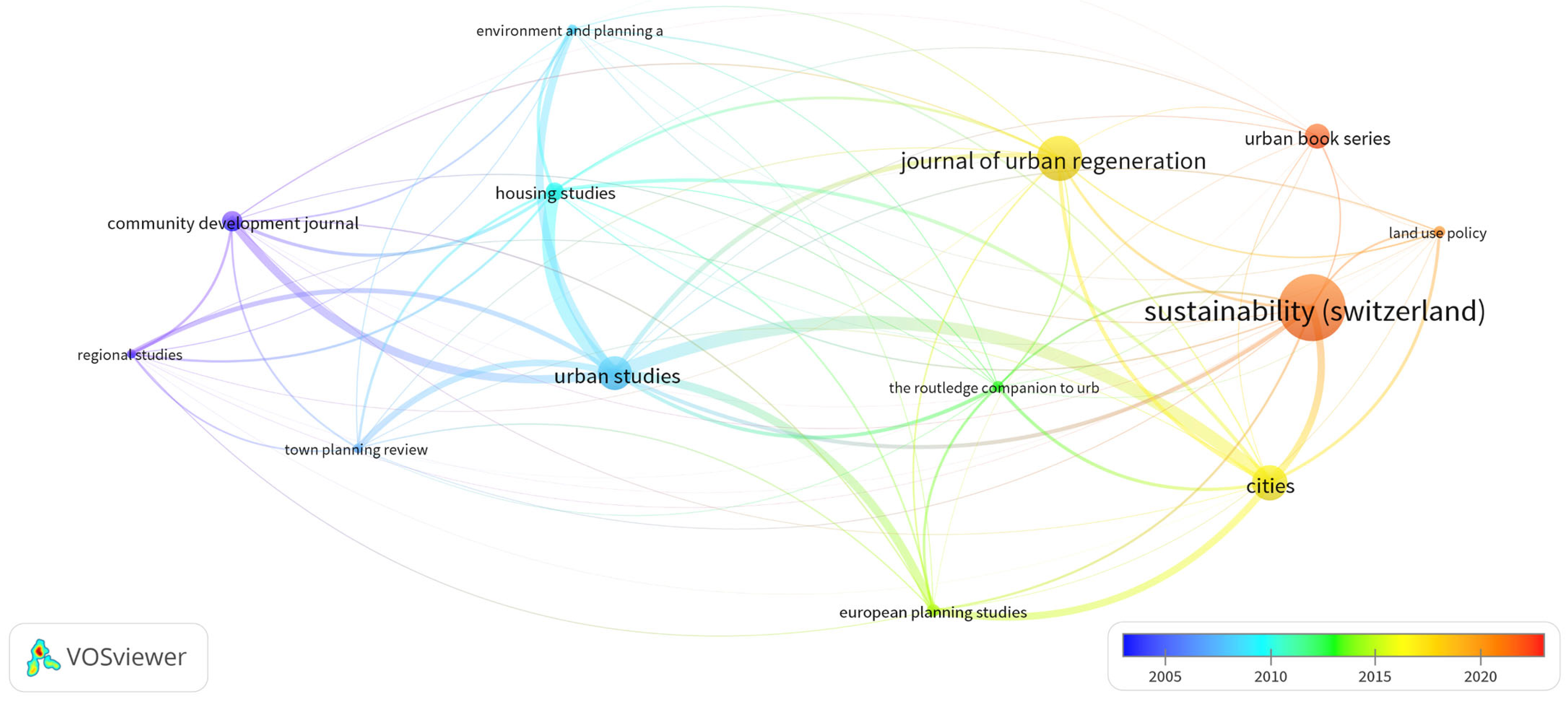

3.3.3. Citation Source Network

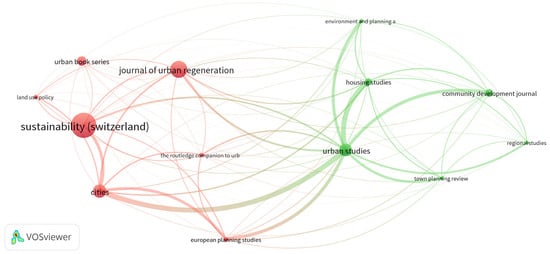

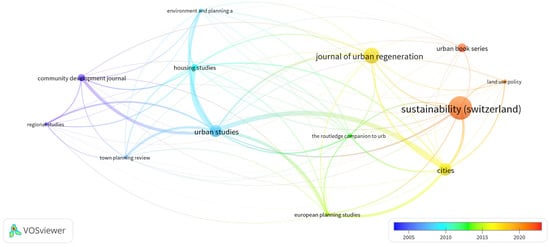

The citation source network forms distinct clusters representing major sources that predominantly cite other literature. In the analysis of the citation source network, out of 210 sources, 12 met the defined threshold (with a minimum of 10 documents and 0 citations for each source). Figure 8 illustrates this network, with results categorized into two groups. The journal map generated based on the literature keywords has been divided into two clusters. Journals within each cluster exhibit similarity in their research related to CR from a SSP. This suggests that these journals typically cover similar research domains and topics, and they have strong interactivity among them. Additionally, these journals hold significant authority or influence in specific fields and disciplines, such as urban studies and urban design. Therefore, they form two distinct dense clusters within the map.

Figure 8.

Citation source network based on the number of publications (2005–2020). Source: WoS 2024.

In the red cluster, there are journals such as “Sustainability,” “Journal of Urban Regeneration,” “Land Use Policy,” “Cities,” “European Planning Studies,” and the “Urban Book Series.”

The green cluster includes journals such as “Urban Studies,” “Housing Studies,” “Environment and Planning A,” “Community Development Journal,” and “Regional Studies.” The visualization in Figure 8 effectively delineates the distinct clusters of citation sources in the field.

On the other hand, the temporal analysis of sources indicates how research on CR from the SSP has evolved through distinct domains. The temporal network illustrated in Figure 8 demonstrates that journals such as “Community Development Journal” and “Regional Studies” made initial contributions to research in CR from the SSP. Subsequently, during the period from 2010 to 2015, journals such as “Urban Studies,” “Housing Studies,” and “Environment and Planning A” followed suit. In the years 2016 to 2022, journals such as “Sustainability,” “Cities,” and “Land Use Policy” played a significant role in advancing this area of study. The temporal analysis also revealed that after 2016, the journal “Journal of Urban Regeneration and Renewal” began contributing to research on CR from the SSP.

4. Emerging Prospects of CR toward the Social Sustainability

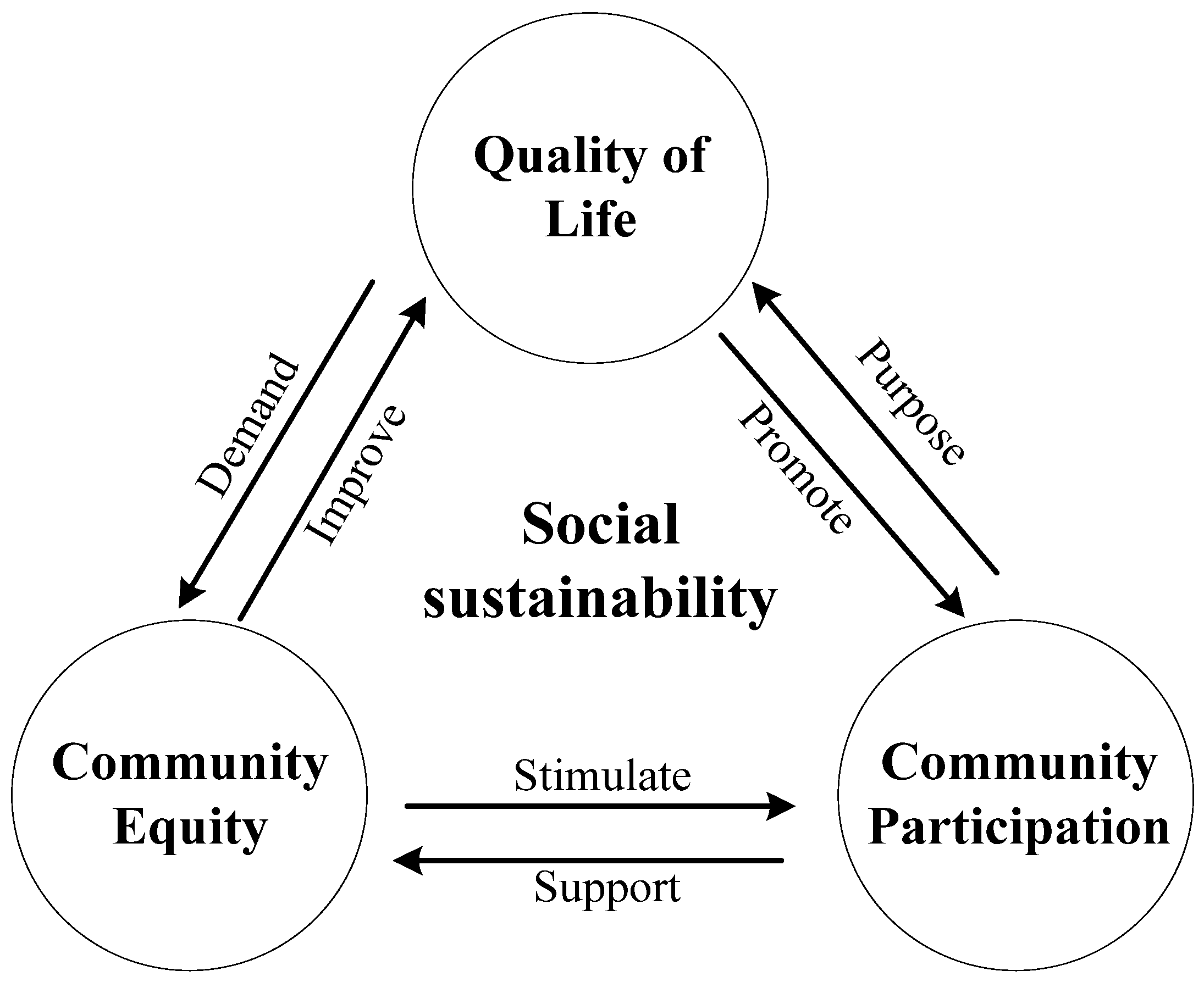

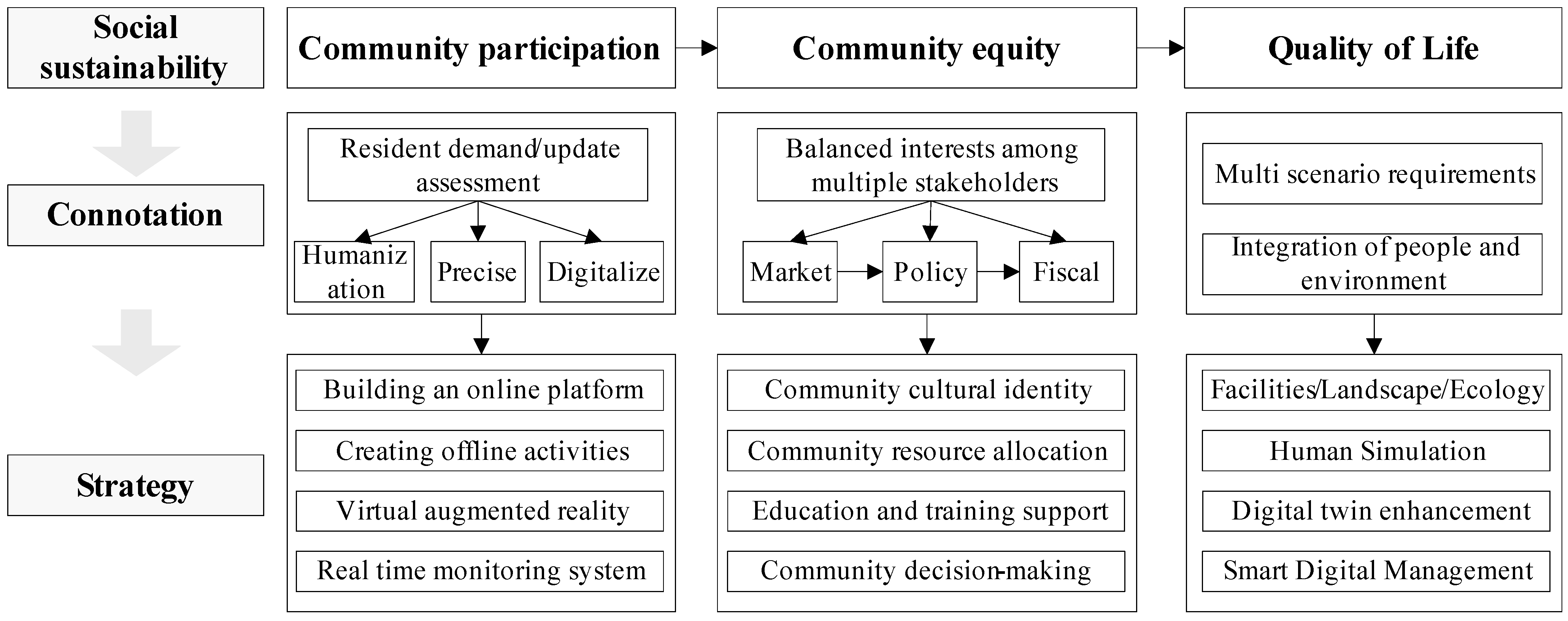

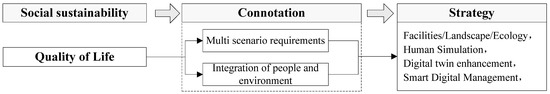

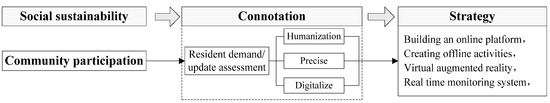

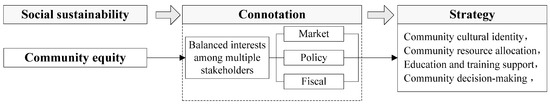

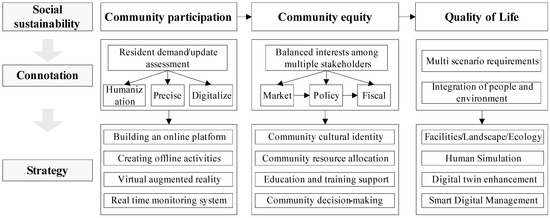

Amidst the current phase of urban regeneration, guiding principles for achieving socially sustainable development in CR have become increasingly crucial. These principles necessitate a comprehensive consideration of the connotations and interconnections among the key elements of QoL, community participation, and community equity (Figure 9). Simultaneously, they should evolve in tandem with the emerging scenarios, technological advancements, and the demands and characteristics of new developmental ideologies of this era. Enhancing the relevant content of each element and building a multi-dimensional, adaptable, comprehensive implementation pathway around ‘QoL–community participation–community equity’ becomes imperative. This initiative aims to propel research and practice in this field forward.

Figure 9.

The research trend chart of CR from the SSP.

4.1. The Cultivation of Community QoL in New Scenario Demands

The creation of a high-quality living environment serves as the spatial carrier for socially sustainable urban regeneration processes, aiming to construct a livable community through the development of well-organized community facilities [55,56,57]. The research on the cultivation of QoL primarily focuses on analyzing the relationship between people and their environment, building an environment adaptable to diverse scenario demands centered around ‘people and nature’ and ‘people and space’ to achieve socially sustainable CR. Regarding the fusion between people and nature, ecological landscapes are highlighted within regional settings [58], enhancing spatial quality by establishing multi-level, mid-scale ecological infrastructure [10]. Enhancements in public spaces involve adopting multiple approaches to comprehensively understand residents’ multiple scenario demands for living spaces [59]. This involves participatory spatial workshops [60], aimed at targeted and precise shaping of community public spaces, such as the implementation of a community planner responsibility system in the Ghalam Gudeh CR project [61], and the utilization of spatial refinement measurements and design simulation methods in the Shuangjing CR project, which won the Sustainable Cities Pilot Community Award issued by UN-HABITAT [62].

At the implementation level, research considers the essence and requirements of cultivating QoL. Central to the core relationship of ‘people and nature’ and ‘people and space,’ efforts create scenarios where people and nature coexist symbiotically. This not only embodies the requirements for updated concepts and systems in new scenarios, but also requires planning and design practitioners to not limit themselves to the regeneration of infrastructure and public spaces [58]. It demands the promotion of multidimensional spatial enhancements, including residential spaces, public spaces, and service facilities. Practical explorations, such as participatory creation of community public spaces in high-density city settings and high-quality spatial creation through community gardens [63], aim to optimize attributes of community public spaces to meet the demands of new scenarios, enhance community QoL, and achieve socially sustainable CR.

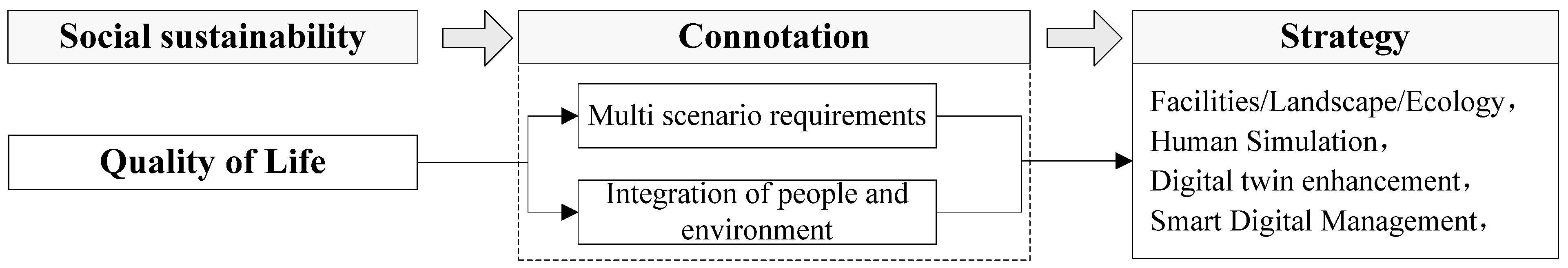

This multifaceted cultivation of QoL within diverse scenarios aligns with current policy directions, including well-organized commercial service facilities, holistic municipal supporting facilities, ample public activity spaces, comprehensive property management, and sound community management mechanisms [64,65,66]. Simultaneously, the cultivation of QoL in new scenario demands necessitates integration with the development of new technologies, including the use of artificial intelligence to simulate individual demands for usage scenarios, employing digital twin mappings, such as sensor technology and monitoring systems, to comprehensively record community environmental conditions, allowing spatial responses to be data-driven, achieving digital twinning and scenario simulation [67]. This requires intelligent digital management to enhance individuals’ perceptions of QoL (Figure 10).

Figure 10.

The cultivation of community QoL in new scenario demands.

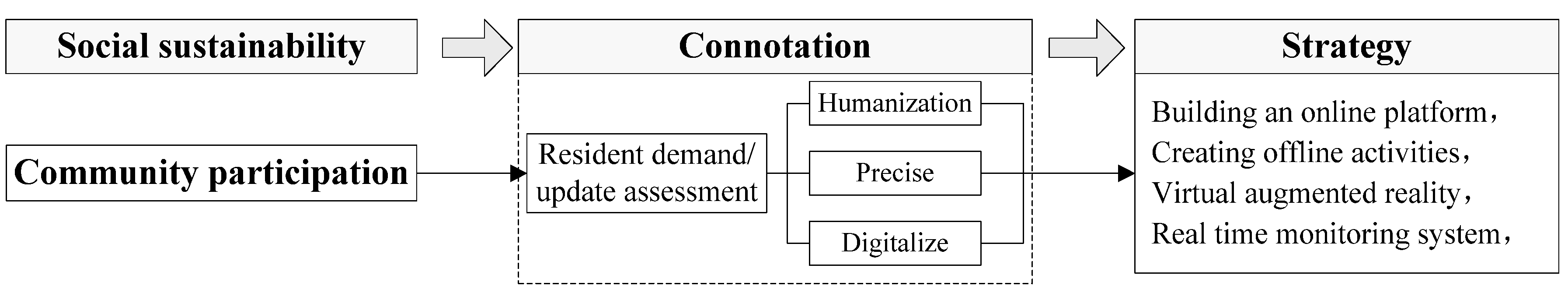

4.2. Community Participation via Emergence of New Technologies

With the emergence of new technologies, such as digitization, human-centered design, and precision techniques such as artificial intelligence and big data, new avenues have been opened for societal participation in CR [68]. Applying these technologies can unlock latent value within CR, enabling balanced participation from diverse stakeholders while enhancing efficiency and reducing regeneration costs. This includes the identification of spatial utilization efficiency, layout, facility selection, and scenario usage predictions through refined data collection, real-time monitoring, and virtual and augmented reality technologies [69,70,71].

Regarding decision-making support in regeneration initiatives, new technologies offer comprehensive possibilities for community participation. For instance, leveraging multi-source data analysis and Geographic Information Systems (GIS) uncovers the potential for CR, precisely identifying regeneration needs [72,73]. By analyzing community residents’ demands, social capital, environmental factors, and infrastructure conditions, targeted regeneration plans can be devised [74]. Furthermore, virtual and augmented reality technologies visualize CR plans, aiding community residents in better understanding and engaging in projects. Coupled with social media and online engagement platforms, establishing online community participation platforms enables residents to participate in regeneration decisions on a full-time and embodied basis [75].

In assessing regeneration efficiency, the emergence of new technologies has driven diversified and precise evaluations of societal participation. For instance, research methods, such as Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA), Social Impact Assessment (SIA), and Health Impact Assessment (HIA), are commonly applied in studies related to CR. EIA is typically used to identify the potential environmental impacts of proposed projects or policies, especially on biological and physical environments. On the other hand, SIA focuses on the societal feedback and impacts of CR, gradually shifting toward human-centered and precise studies at the level of individual community residents. For instance, Deakin proposed an assessment system centered on people and based on places [76]. Awad utilized the Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP) to extract planning elements of urban regeneration [77], or models such as structural equations [78] and regression were used to investigate residents’ well-being [79].

Moreover, the sources of assessment data have expanded from traditional field surveys, questionnaires, and photo interviews to spatiotemporal data such as GPS location data, and digital online platforms such as Twitter, Weibo, and TikTok [80]. Through acquiring social network data from various social media platforms, including geographical location information, textual data, and emotional sentiment, it becomes feasible to conduct large-scale, high-precision analysis of individual users, thereby enabling comprehensive people-centered analysis [81,82,83]. This combination of ‘big’ and ‘small’ data aids in cross-validating residents’ regeneration intentions, enhances the cognition and identification of community spaces, and improves the objectivity and precision of spatial recognition (Figure 11).

Figure 11.

Community participation via the emergence of new technologies.

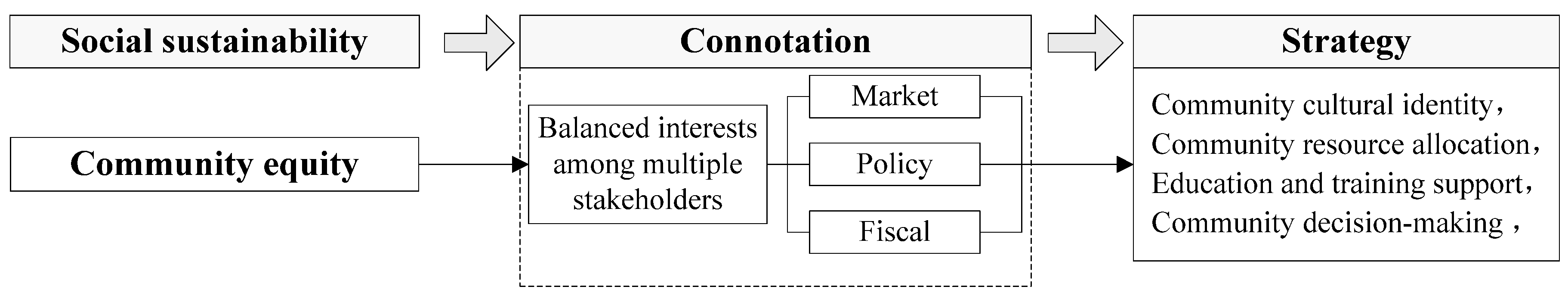

4.3. Community Equity under the New Developmental Paradigm

The new developmental paradigm emphasizes high-quality development, people’s sense of happiness, and social equity, viewing communities as the fundamental units of people’s lives, with particular attention to fairness within communities and residents’ sense of belonging [84]. Ensuring fairness in resource allocation and welfare distribution during CR is essential to avoid neglecting vulnerable groups [85,86,87].

In recent years, studies on community equity in CR have focused on balancing the interests of diverse stakeholders. On the one hand, there is a concentration on fund procurement and interest distribution in the regeneration process. This includes discussions on community-based agricultural economic models [11], feasibility studies on action economics [88], the new economic attributes of communities, and studies on balancing community values [89]. These endeavors explore multidimensional approaches to establish new economic models within communities, seeking to enhance the value of community spaces and properties. On the other hand, attention is directed toward using current economic data collection methods to establish sustainable economic models promoting social equity in CR. This involves using on-site interviews, tracking surveys to analyze communities’ current economic development status, or utilizing new devices such as Web network hotspots [90] and Wi-Fi probes to collect community economic data. With the digital economy’s and society’s development, a bottom-up voluntary model for socially sustainable regeneration initiated by residents is gradually taking shape [91,92]. Through practical cooperation involving shared funding, residents, market forces, financial institutions, and policy frameworks collectively contribute to diversifying economic sustainability in the CR process and promoting social equity.

Under the new developmental paradigm, social equity not only involves the equitable distribution of resources, such as public services and cultural resources within and around communities, but also encompasses the participation rights of community residents in decision-making and management [93,94]. Social equity implies that there should not be significant disparities between different communities, and each community should have equal development opportunities, including fairness in land acquisition, protection of residents’ rights and interests, and equitable distribution of community services [95,96]. The path to achieving social equity includes the fair allocation of resources required by communities to provide high-quality public services and improve infrastructure, support for community culture, and education, providing residents with opportunities to participate in community affairs, decision-making, and management through initiatives such as community councils and resident representative elections [97,98]. Simultaneously, encouraging and supporting various cultural and social activities fosters interactions among residents and strengthens community belongingness, thus inspiring residents to actively engage in community affairs and contribute to community development (Figure 12).

Figure 12.

Community equity under the new developmental paradigm.

5. Implementation Path for CR toward Social Sustainability

Based on the above, the implementation pathway for socially sustainable regeneration of communities revolves around a multidimensional alignment of ‘QoL–community participation–community equity.’ It necessitates a foundation in diverse community involvement to thoroughly acquire intentions and demands for renovation and transformation [99]. Subsequently, while considering community equity as a prerequisite, it is imperative to factor in the interests of the majority in decision-making and funding procurement, particularly in addressing the demands of vulnerable groups. Ultimately, this combines people and the environment, carefully enhancing the community’s QoL.

As depicted in Figure 13, community participation demands researchers to humanize, make precise, and digitize residents’ needs and renovation assessments. This precision-oriented approach necessitates meticulous social research and involvement as its foundation [100]. Balancing diverse stakeholders’ interests requires comprehensive consideration of residents, tenants, and stakeholders, especially vulnerable groups, such as the elderly, disabled individuals, and low-income communities [101,102]. This constitutes the fundamental requirement for achieving community equity and is the primary prerequisite for balancing multiple stakeholder interests fairly. It forms a crucial basis for portraying precise individual profiles within the community, meeting the fusion of human and environmental needs in diverse scenarios, thus enhancing the QoL.

Figure 13.

Diagram illustrating the implementation pathway for CR from the SSP.

In this context, comprehensive coverage and precise integrated analysis of various elements, such as buildings, facilities, infrastructure, public amenities, historical resources, collective memory sites, etc., are essential. Utilizing digital intelligence to improve community governance, including constructing offline platforms and organizing offline activities, is pivotal [103,104]. Simultaneously, respecting various wishes from cultural identity, resource allocation, education and training, decision-making aspects, establishing clear rules for rights distribution, and promoting long-term localized operational models are crucial [105]. This fosters a sense of community belonging led by culture. Providing multi-scenario spatial development plans, employing artificial intelligence simulations, digital twinning, and other means, enhances the community’s QoL.

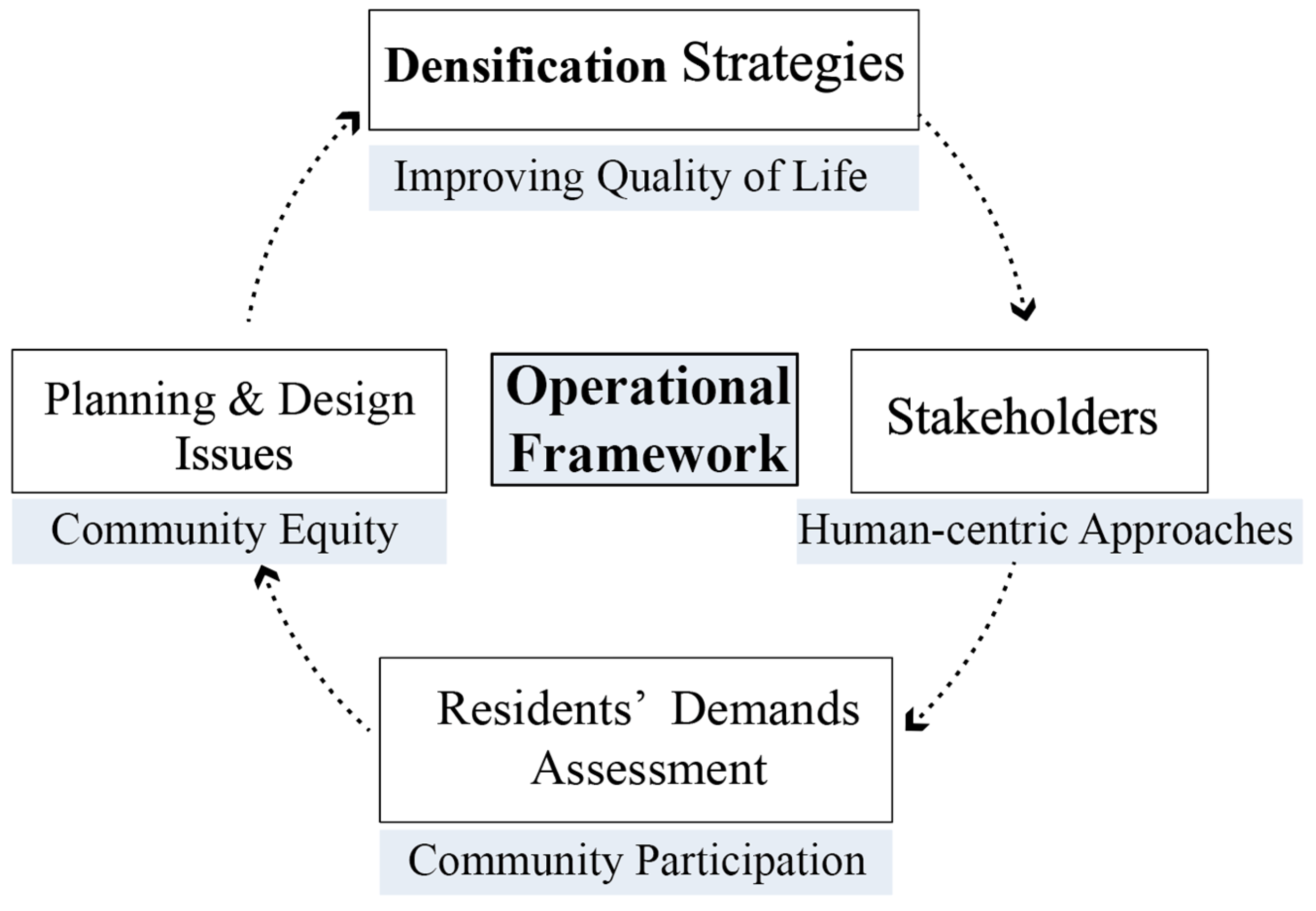

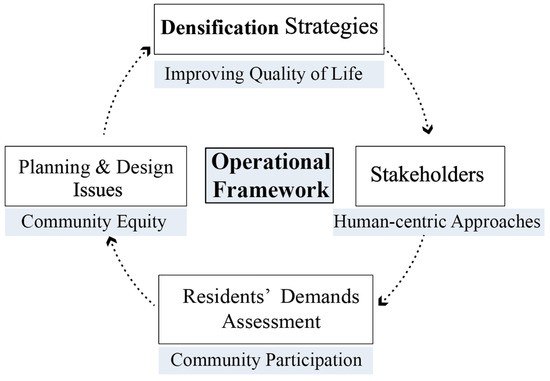

From the SSP, it is imperative to establish a systematic and diversified implementation path that reinforces the existing pattern. Previously, CR has predominantly centered on retaining, renovation, and rebuilding [106,107]. However, current research underscores the potential of densification as a more balanced strategy [108,109,110]. Densification is a recurrent process in the urbanization journey, emphasizing the interconnectedness of density with the environment and advocating for a context-driven approach. The benefits of densification extend to generating more vibrant infrastructure, public facilities, and open public spaces, allowing for maximal utilization [111,112]. The primary objective of densification is to address spatial deficiencies, fortify weak links, and infuse new vitality into the community. This signifies the adoption of a densification strategy for the community, encompassing the enhancement of community functions, the improvement of spatial utilization efficiency, and the facilitation of closer integration of internal and external resources [113]. Eventually, this comprehensive approach realizes the holistic rejuvenation of communities from a socially sustainable perspective.

Densification represents a pragmatic and sustainable approach to CR from the SSP and holds the potential for integrative and inclusive goals, ensuring the realization of social justice [114,115]. Simultaneously, through densification, the enhancement of interactions between residents and public spaces and the creation of appropriate public facilities and cultural spaces are facilitated, thereby supporting a vibrant community living environment [116,117]. Indeed, linking pathways, such as community engagement and social equity, to the implementation of densification requires a comprehensive operational framework that fundamentally associates individual stakeholders’ recognition of regeneration implementation (Figure 14): measuring resident needs, balancing various stakeholder demands, and fully considering various elements at the planning level, such as policy guidance and spatial design requirements. Synthesis of all these contents, formulating the co-related densification solutions and implementation strategies, can achieve appropriate and targeted improvement in community QoL [118,119]. Notably, with the continuous evolution of society, residents’ demands and expectations undergo constant changes. Once it is observed that the existing spatial environment and management approaches are no longer suitable, a progressive and dynamic CR guided by this operational framework should be initiated.

Figure 14.

Densification operational framework for social sustainable CR.

6. Conclusions

This study employed VOSviewer software to summarize and synthesize the research orientation of CR from the SSP. The research predominantly uncovered the implications and research directions of CR regarding QoL, social engagement, and social equity. It analyzed the focal points of global studies on CR and planning decision-making while exploring the implementation pathways from the perspective of new scenarios, technologies, and developmental paradigms in achieving social sustainability. Specifically, it delved into the humanization of QoL creation, precision and diversity in community participation, and the sense of belonging concerning social equity.

Regarding research trends, in recent years, research on CR from the SSP has been a popular topic. Overall, the research has attained a relatively in-depth level. The recent research method aligns with emerging new tools, such as multi-source big data, real-time monitoring systems, digital management technologies, etc.

Concerning research strategies, the CR necessitates a holistic consideration of combining densification with synergistic and augmented approaches to enhance QoL and promote social equity. Regarding long-term mechanisms, it is imperative to recognize that CR is not a conclusive blueprint-like transformation but a progressive optimization process. Alongside strengthening grassroots community governance, emphasis should be placed on continuous cultural empowerment throughout the entire cycle to enhance residents’ sense of belonging and happiness, thereby creating a positive loop of life satisfaction.

Within urban planning and design disciplines, exploring CR from the SSP signifies a shift from city-scale layout strategies to intricate micro-scale improvements at the community scale. It embodies enhancing spatial quality and an effective means of creating a high-quality living environment. Through skillful spatial densification decision-making and meticulous attention, maximizing resource utilization within limited spaces, communities can radiate newfound vitality amidst complex and high-density urban settings, thereby crafting more habitable living spaces for residents. These micro-level improvements collectively drive urban development, achieving established urban planning objectives while addressing the nuanced yet profoundly significant aspects of social sustainability within the city.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.C., J.H. and P.L.; methodology, P.L. and J.C.; software, P.L.; validation, J.C., J.H. and J.Y.; formal analysis, J.C. and P.L.; investigation, J.H., J.C., H.W. and P.L.; resources, J.C.; data curation, H.W. and P.L.; writing—original draft preparation, J.C., J.H. and P.L.; writing—review and editing, J.C., P.L. and H.W.; visualization, P.L.; supervision, J.C.; project administration, J.C., J.H. and J.Y.; funding acquisition, J.C., J.H. and J.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by [Advance Research Program of National Level Projects in Suzhou City University] grant number [2023SGY009]; The APC was funded by [2023SGY009].

Data Availability Statement

All data obtained through the Web of Science database.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Atkinson, R. Discourses of Partnership and Empowerment in Contemporary British Urban Regeneration. Urban Stud. 1999, 36, 59–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, G.; Newman, G.; Jiang, B. Urban Regeneration: Community Engagement Process for Vacant Land in Declining Cities. Cities 2020, 102, 102730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raszkowski, A.; Bartniczak, B. On the Road to Sustainability: Implementation of the 2030 Agenda Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) in Poland. Sustainability 2019, 11, 366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Zhao, Y.; Gao, X.; Gao, B. Collaborative Decision-Making for Urban Regeneration: A Literature Review and Bibliometric Analysis. Land Use Policy 2021, 107, 105479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Z.; Jiang, C. Imitation, Reference, and Exploration—Development Path to Urban Renewal in China (1985-2017). J. Urban Hist. 2020, 46, 728–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Xu, Y.; Zhou, C.; Zou, Y. Governing regional inequality through regional cooperation? A case study of the Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macau Greater Bay area. Appl. Geogr. 2024, 162, 103135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Pellegrini, P.; Wang, H. Comparative Residents’ Satisfaction Evaluation for Socially Sustainable Regeneration—The Case of Two High-Density Communities in Suzhou. Land 2022, 11, 1483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Pellegrini, P.; Xu, Y.; Ma, G.; Wang, H.; An, Y.; Shi, Y.; Feng, X. Evaluating Residents’ Satisfaction before and after Regeneration. The Case of a High-Density Resettlement Neighbourhood in Suzhou, China. Cogent Soc. Sci. 2022, 8, 2144137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visa, I.; Duta, A.; Moldovan, M.; Burduhos, B.; Neagoe, M. Sustainable Communities. In Solar Energy Conversion Systems in the Built Environment; Green Energy and Technology; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 341–384. [Google Scholar]

- Tzoulas, K.; Korpela, K.; Venn, S.; Yli-Pelkonen, V.; Kaźmierczak, A.; Niemela, J.; James, P. Promoting Ecosystem and Human Health in Urban Areas Using Green Infrastructure: A Literature Review. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2007, 81, 167–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Sun, Y.; Luan, X. Regulation flexibility and legitimacy building in governing intercity railways: The polymorphous role of the Chinese provincial government. J. Urban Aff. 2023, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundelin, A. Reaching Social Sustainability in Residential Architecture. Master’s Thesis, Chalmers University of Technology, Gothenburg, Sweden, 2019; pp. 30–49. [Google Scholar]

- Bramley, G.; Dempdey, N.; Power, S.; Brown, C.; Watkins, D. Social Sustainability and Urban Form: Evidence from Five British Cities. Environ. Plan. A 2009, 41, 2125–2142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feenstra, G.W. Local Food Systems and Sustainable Communities. Am. J. Altern. Agric. 1997, 12, 28–36. [Google Scholar]

- Agyeman, J. Sustainable Communities and the Challenge of Environmental Justice. In Sustainable Communities and the Challenge of Environmental Justice; New York University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Ghahramanpouri, A.; Lamit, H.; Sedaghatnia, S. Urban Social Sustainability Trends in Research Literature. Asian Soc. Sci. 2013, 9, 185–193. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X.; Shen, J.; Sun, Y.; Zhou, C.; Yang, Y. Formation of city regions from bottom-up initiatives: Investigating coalitional developmentalism in the Pearl River Delta. Ann. Am. Assoc. Geogr. 2023, 113, 700–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eizenberg, E.; Jabareen, Y. Social Sustainability: A New Conceptual Framework. Sustainability 2017, 9, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharya, P.; Vahter, M.; Jarsjö, J.; Kumpiene, J.; Ahmad, A.; Sparrenbom, C.; Jacks, G.; Donselaar, M.E.; Bundschuh, J.; Naidu, R. Arsenic Research and Global Sustainability: Proceedings of the Sixth International Congress on Arsenic in the Environment (As2016), June 19–23, 2016, Stockholm, Sweden; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2016; ISBN 1315364131. [Google Scholar]

- Olakitan Atanda, J. Developing a Social Sustainability Assessment Framework. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2019, 44, 237–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallance, S.; Perkins, H.C.; Dixon, J.E. What Is Social Sustainability? A Clarification of Concepts. Geoforum 2011, 42, 342–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berg, P.G.; Nycander, G. Sustainable Neighbourhoods—A Qualitative Model for Resource Management in Communities. Landsc. Urban Plan. 1997, 39, 117–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- London, B.; Downey, G.; Bonica, C.; Paltin, I. Social Causes and Consequences of Rejection Sensitivity. J. Res. Adolesc. 2007, 17, 481–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caulfield, J.; Polèse, M.; Stren, R.; Polese, M. The Social Sustainability of Cities: Diversity and the Management of Change. Can. Public Policy Anal. Polit. 2001, 27, 381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magee, L.; Scerri, A.; James, P. Measuring Social Sustainability: A Community-Centred Approach. Appl. Res. Qual. Life 2012, 7, 239–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, W.; Timmermans, H.J.P. Residential satisfaction in renovated historic blocks in two Chinese cities. Prof. Geogr. 2021, 73, 333–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, S. International Encyclopedia of Housing and Home; Elsevier Science: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Hansmann, R.; Mieg, H.A.; Frischknecht, P. Principal sustainability components: Empirical analysis of synergies between the three pillars of sustainability. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. World Ecol. 2012, 19, 451–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Ye, C.; Liu, Y. From the Arrival Cities to Affordable Cities in China: Seeing through the Practices of Rural Migrants’ Participation in Guangzhou’s Urban Village Regeneration. Habitat Int. 2023, 138, 102872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moss, T. Utilities, Land-Use Change, and Urban Development: Brownfield Sites as ‘Cold-Spots’ of Infrastructure Networks in Berlin. Environ. Plan. A 2003, 35, 511–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arthurson, K. Neighbourhood Regeneration: Facilitating Community Involvement. Urban Policy Res. 2003, 21, 357–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pilogallo, A.; Saganeiti, L.; Fiorini, L.; Marucci, A. Ecosystem Services for Planning Impacts Assessment on Urban Settlement Development. In Computational Science and Its Applications—ICCSA 2022 Workshops, Proceedings of the International Conference on Computational Science and Its Applications, Malaga, Spain, 4–7 July 2022; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 241–253. [Google Scholar]

- Van Bortel, G.; Mullins, D. Critical Perspectives on Network Governance in Urban Regeneration, Community Involvement and Integration. J. Hous. Built Environ. 2009, 24, 203–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- dos Figueiredo, Y.D.S.; Prim, M.A.; Dandolini, G.A. Urban Regeneration in the Light of Social Innovation: A Systematic Integrative Literature Review. Land Use Policy 2022, 113, 105873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, N. The Role, Organisation and Contribution of Community Enterprise to Urban Regeneration Policy in the UK. Prog. Plann. 2012, 77, 1–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Xu, Y. Achieving Neighborhood-Level Collaborative Governance through Participatory Regeneration: Cases of Three Residential Heritage Neighborhoods in Shanghai. Sustainability 2024, 16, 2082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Tian, W.; Xu, K.; Pellegrini, P. Testing Small-Scale Vitality Measurement Based on 5D Model Assessment with Multi-Source Data: A Resettlement Community Case in Suzhou. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2022, 11, 626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abed, A.R. Assessment of Social Sustainability: A Comparative Analysis. Proc. Inst. Civ. Eng. Urban Des. Plan. 2017, 170, 72–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yolles, M. Sustainability Development: Part 2—Exploring the Dimensions of Sustainability Development. Int. J. Mark. Bus. Syst. 2018, 3, 257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, E.; Lee, G.K.L. Critical Factors for Improving Social Sustainability of Urban Renewal Projects. Soc. Indic. Res. 2008, 85, 243–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colantonio, A.; Dixon, T. Social Sustainability and Sustainable Communities: Towards a Conceptual Framework. In Urban Regeneration & Social Sustainability: Best Practice from European Cities; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2011; pp. 18–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bottero, M.; Mondini, G.; Datola, G. Decision-Making Tools for Urban Regeneration Processes: From Stakeholders Analysis to Stated Preference Methods. TEMA-J. L. Use Mobil. Environ. 2017, 10, 193–212. [Google Scholar]

- Rogerson, R.J. Quality of Life and City Competitiveness. Urban Stud. 1999, 36, 969–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, P.; Jennings, I. Cities as Sustainable Ecosystems: Principles and Practices; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2012; ISBN 1597267473. [Google Scholar]

- Buettner-Schmidt, K.; Lobo, M.L. Social Justice: A Concept Analysis. J. Adv. Nurs. 2012, 68, 948–958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dorsch, M.T.; Maarek, P. Democratization and the Conditional Dynamics of Income Distribution. Am. Polit. Sci. Rev. 2019, 113, 385–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, M.E. The Archaeological Study of Neighborhoods and Districts in Ancient Cities. J. Anthropol. Archaeol. 2010, 29, 137–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Shaw, D. The Complexity of High-Density Neighbourhood Development in China: Intensification, Deregulation and Social Sustainability Challenges. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2018, 43, 578–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhi, Y.; Jian, Z.; Ling, H.; Lin, W.; Zhengxin, L.; Yan, T.; Yujun, C. Community Building and Community Regeneration. China City Plan. Rev. 2021, 30, 6–19. [Google Scholar]

- Fainstein, S.S. The Just City. Int. J. Urban Sci. 2014, 18, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvey, D. Rebel Cities: From the Right to the City to the Urban Revolution; Verso Books: Brooklyn, NY, USA, 2012; ISBN 1844678822. [Google Scholar]

- Gu, Z.; Zhang, X. Framing Social Sustainability and Justice Claims in Urban Regeneration: A Comparative Analysis of Two Cases in Guangzhou. Land Use Policy 2021, 102, 105224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.; Yang, D. Urban Regeneration in China: Institutional Innovation in Guangzhou, Shenzhen, and Shanghai; Routledge: London, UK, 2021; ISBN 1000408051. [Google Scholar]

- Li, S.; Ma, S.; Tong, D.; Jia, Z.; Li, P.; Long, Y. Associations between the Quality of Street Space and the Attributes of the Built Environment Using Large Volumes of Street View Pictures. Environ. Plan. B Urban Anal. City Sci. 2022, 49, 1197–1211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yıldız, S.; Kıvrak, S.; Gültekin, A.B.; Arslan, G. Built Environment Design-Social Sustainability Relation in Urban Renewal. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2020, 60, 102173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, H.H.; Hu, T.-S.; Fan, P. Social Sustainability of Urban Regeneration Led by Industrial Land Redevelopment in Taiwan. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2019, 27, 1245–1269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deakin, M.; Allwinkle, S. Urban Regeneration and Sustainable Communities: The Role of Networks, Innovation, and Creativity in Building Successful Partnerships. J. Urban Technol. 2007, 14, 77–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barton, H. Sustainable Communities: The Potential for Eco-Neighbourhoods; Earthscan: London, UK, 2000; ISBN 1853835137. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, J. Micro-Regeneration in Shanghai and the Public-Isation of Space. Habitat Int. 2023, 132, 102741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Zhang, F.; Hui, E.C.; Lang, W. Collaborative Workshop and Community Participation: A New Approach to Urban Regeneration in China. Cities 2020, 102, 102743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pourzakarya, M.; Bahramjerdi, S.F.N. Community-Led Regeneration Practice in Ghalam Gudeh District, Bandar Anzali, Iran: A Participatory Action Research (PAR) Project. Land Use Policy 2021, 105, 105416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Pan, J.; Qian, Y. Collaborative Governance for Participatory Regeneration Practices in Old Residential Communities within the Chinese Context: Cases from Beijing. Land 2023, 12, 1427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, S.; Wang, B.; Liu, W.; Zhou, H.; Wang, Y.; Li, S. Assessment of Street Space Quality and Subjective Well-Being Mismatch and Its Impact, Using Multi-Source Big Data. Cities 2024, 147, 104797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Y.; Hui, E.C.M.; Wen, H. The Housing Market Impacts of Human Activities in Public Spaces: The Case of the Square Dancing. Urban For. Urban Green. 2020, 54, 126769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Wang, J.; Kwan, M.-P.; Chai, Y. Reside Nearby, Behave Apart? Activity-Space-Based Segregation among Residents of Various Types of Housing in Beijing, China. Cities 2019, 88, 166–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Li, F. Daily Activity Space and Exposure: A Comparative Study of Hong Kong’s Public and Private Housing Residents’ Segregation in Daily Life. Cities 2016, 59, 148–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Deng, Q.; Guo, M.; Li, Y.; Lu, F.; Chen, J.; Sun, J.; Chang, J.; Hu, P.; Liu, N. Using street view imagery to examine the association between urban neighborhood disorder and the long-term recurrence risk of patients discharged with acute myocardial infarction in central Beijing, China. Cities 2023, 138, 104366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bassett, K. Urban Cultural Strategies and Urban Regeneration: A Case Study and Critique. Environ. Plan. A 1993, 25, 1773–1788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, F.; He, H.; Cui, W. A Review of Sustainable Urban Regeneration Approaches Based on Augmented Reality Technology: A Case of the Bund in Shanghai. Sustainability 2022, 14, 12869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanaeipoor, S.; Emami, K.H. Smart City: Exploring the Role of Augmented Reality in Placemaking. In Proceedings of the 2020 4th International Conference on Smart City, Internet of Things and Applications (SCIOT), Mashhad, Iran, 16–17 September 2020; pp. 91–98. [Google Scholar]

- Hunter, M.; Soro, A.; Brown, R. Enhancing Urban Conversations for Smarter Cities: Augmented Reality as an Enabler of Digital Civic Participation. Interact. Des. Archit. 2021, 48, 75–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Pellegrini, P.; Yang, Z.; Wang, H. Strategies for Sustainable Urban Renewal: Community-Scale GIS-Based Analysis for Densification Decision Making. Sustainability 2023, 15, 7901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiorini, L.; Falasca, F.; Marucci, A.; Saganeiti, L. Discretization of the Urban and Non-Urban Shape: Unsupervised Machine Learning Techniques for Territorial Planning. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 10439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Wang, H.; Yang, Z.; Li, P.; Ma, G.; Zhao, X. Comparative Spatial Vitality Evaluation of Traditional Settlements Based on SUF: Taking Anren Ancient Town’s Urban Design as an Example. Sustainability 2023, 15, 8178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyler, P.; Warnock, C.; Provins, A.; Lanz, B. Valuing the Benefits of Urban Regeneration. Urban Stud. 2013, 50, 169–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deakin, M. A Community-Based Approach to Sustainable Urban Regeneration. J. Urban Technol. 2009, 16, 91–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awad, J.; Jung, C. Extracting the Planning Elements for Sustainable Urban Regeneration in Dubai with AHP (Analytic Hierarchy Process). Sustain. Cities Soc. 2022, 76, 103496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Y.; He, J.; Han, H.; Zhang, W. Evaluating Residents’ Satisfaction with Market-Oriented Urban Village Transformation: A Case Study of Yangji Village in Guangzhou, China. Cities 2019, 95, 102394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gür, M.; Murat, D.; Sezer, F.Ş. The Effect of Housing and Neighborhood Satisfaction on Perception of Happiness in Bursa, Turkey. J. Hous. Built Environ. 2020, 35, 679–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, T.; Chang, H.; Liang, S.; Jones, P.; Chan, P.W.; Li, L.; Huang, J. Heat and Park Attendance: Evidence from “Small Data” and “Big Data” in Hong Kong. Build. Environ. 2023, 234, 110123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Cui, Y.; Li, L.; Guo, M.; Ho, H.C.; Lu, Y.; Webster, C. Re-Examining Jane Jacobs’ Doctrine Using New Urban Data in Hong Kong. Environ. Plan. B Urban Anal. City Sci. 2023, 50, 76–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Cui, Y.; Chang, H.; Obracht-Prondzyńska, H.; Kamrowska-Zaluska, D.; Li, L. A City Is Not a Tree: A Multi-City Study on Street Network and Urban Life. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2022, 226, 104469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, M.; Lin, Y.; Shyu, R.J.; Huang, J. Characterizing environmental pollution with civil complaints and social media data: A case of the Greater Taipei Area. J. Environ. Manag. 2023, 348, 119310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carpiano, R.M.; Hystad, P.W. “Sense of Community Belonging” in Health Surveys: What Social Capital Is It Measuring? Health Place 2011, 17, 606–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, A.F.; Russell, A.; Powers, J.R. The Sense of Belonging to a Neighbourhood: Can It Be Measured and Is It Related to Health and Well Being in Older Women? Soc. Sci. Med. 2004, 59, 2627–2637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanbar, L. Sense of Belonging and Commitment as Mediators of the Effect of Community Features on Active Involvement in the Community. City Community 2020, 19, 617–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herslund, L. Everyday Life as a Refugee in a Rural Setting–What Determines a Sense of Belonging and What Role Can the Local Community Play in Generating It? J. Rural Stud. 2021, 82, 233–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flint, R.W. Seeking Resiliency in the Development of Sustainable Communities. Hum. Ecol. Rev. 2010, 17, 44–57. [Google Scholar]

- Epple, D.; Platt, G.J. Equilibrium and Local Redistribution in an Urban Economy When Households Differ in Both Preferences and Incomes. J. Urban Econ. 1998, 43, 23–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojala, T.; Kukka, H.; Lindén, T.; Heikkinen, T.; Jurmu, M.; Hosio, S.; Kruger, F. UBI-Hotspot 1.0: Large-Scale Long-Term Deployment of Interactive Public Displays in a City Center. In Proceedings of the 2010 Fifth International Conference on Internet and Web Applications and Services, Barcelona, Spain, 9–15 May 2010; pp. 285–294. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Beeton, R.J.S.; Sigler, T.; Halog, A. Enhancing the Adaptive Capacity for Urban Sustainability: A Bottom-up Approach to Understanding the Urban Social System in China. J. Environ. Manag. 2019, 235, 51–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michaelides, M.; Laouris, Y. A Cascading Model of Stakeholder Engagement for Large-Scale Regional Development Using Structured Dialogical Design. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2024, 315, 307–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fontana, L.B.; Grugel, J. The Politics of Indigenous Participation through “Free Prior Informed Consent”: Reflections from the Bolivian Case. World Dev. 2016, 77, 249–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasoolimanesh, S.M.; Jaafar, M.; Ahmad, A.G.; Barghi, R. Community Participation in World Heritage Site Conservation and Tourism Development. Tour. Manag. 2017, 58, 142–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Logan, T.M.; Guikema, S.D. Reframing Resilience: Equitable Access to Essential Services. Risk Anal. 2020, 40, 1538–1553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mandarano, L.; Meenar, M. Equitable Distribution of Green Stormwater Infrastructure: A Capacity-Based Framework for Implementation in Disadvantaged Communities. Local Environ. 2017, 22, 1338–1357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frenkiel, E.; Lama-Rewal, S.T. The Redistribution of Representation through Participation: Participatory Budgeting in Chengdu and Delhi. Polit. Gov. 2019, 7, 112–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendriks, F.; Michels, A.; Callanan, M.; Loughlin, J. Citizen Involvement in Subnational Governance: Innovations, Trends and Questions. In A Research Agenda for Regional and Local Government; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Todd, S. Phoenix Rising: Working-Class Life and Urban Reconstruction, c. 1945–1967. J. Br. Stud. 2015, 54, 679–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vardhan, H.; Kumar, D. The Impact of AI-Enhanced Social Media Strategies on Entrepreneurial Performance. Int. J. Eng. Manag. Res. 2023, 13, 90–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dicks, B. Participatory Community Regeneration: A Discussion of Risks, Accountability and Crisis in Devolved Wales. Urban Stud. 2014, 51, 959–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armstrong, R. Sustainable Community Regeneration: Issues and Opportunities—A Background Discussion Paper Prepared for the State Sustainability Strategy. Master’s Thesis, Murdoch University, Perth, Australia, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, H. The Role of Online and Offline Features in Sustaining Virtual Communities: An Empirical Study. Internet Res. 2007, 17, 119–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cammaerts, B. Social Media and Activism. In The International Encyclopedia of Digital Communication and Society; Wiley-Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 2015; pp. 1027–1034. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J.; Zhang, X.; Lin, J.; Li, Y. Beyond Government-Led or Community-Based: Exploring the Governance Structure and Operating Models for Reconstructing China’s Hollowed Villages. J. Rural Stud. 2022, 93, 273–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egedy, T. Current Strategies and Socio-Economic Implications of Urban Regeneration in Hungary. Open House Int. 2010, 35, 29–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Couch, C.; Sykes, O.; Börstinghaus, W. Thirty Years of Urban Regeneration in Britain, Germany and France: The Importance of Context and Path Dependency. Prog. Plann. 2011, 75, 1–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quastel, N. Political Ecologies of Gentrification. Urban Geogr. 2009, 30, 694–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perić, A.; Hauller, S.; Kaufmann, D. Cooperative Planning under Pro-Development Urban Agenda? A Collage of Densification Practices in Zurich, Switzerland. Habitat Int. 2023, 140, 102922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Chen, Y.; Xu, Y.; Yue, W.; Tang, C. Does regional cooperation constrain urban sprawl? Evidence from the Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macao greater Bay area. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2023, 235, 104742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mualam, N.; Salinger, E.; Max, D. Increasing the Urban Mix through Vertical Allocations: Public Floorspace in Mixed Use Development. Cities 2019, 87, 131–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capeluto, I.G. Buildings’ Morphology, Solar Rights and Zero Energy in High Density Urban Areas. In Sustainable Energy Development and Innovation; Selected Papers from the World Renewable Energy Congress (WREC) 2020; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 351–356. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Q.; Zheng, L.; Wang, Y.; Wu, D.; Li, J. Spillover Effects of Urban Form on Urban Land Use Efficiency: Evidence from a Comparison between the Yangtze and Yellow Rivers of China. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 125816–125831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCarthy, J. Social Justice and Urban Regeneration Policy in Scotland. Urban Res. Pract. 2010, 3, 241–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, L.W.C.; Chau, K.W.; Cheung, P.A.C.W. Urban Renewal and Redevelopment: Social Justice and Property Rights with Reference to Hong Kong’s Constitutional Capitalism. Cities 2018, 74, 240–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, K.; Elands, B.; Buijs, A. Social Interactions in Urban Parks: Stimulating Social Cohesion? Urban For. Urban Green. 2010, 9, 93–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anttiroiko, A.-V. City-as-a-Platform: The Rise of Participatory Innovation Platforms in Finnish Cities. Sustainability 2016, 8, 922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debrunner, G.; Jonkman, A.; Gerber, J.-D. Planning for Social Sustainability: Mechanisms of Social Exclusion in Densification through Large-Scale Redevelopment Projects in Swiss Cities. Hous. Stud. 2022, 39, 146–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arifwidodo, S.D.; Perera, R. Quality of Life and Compact Development Policies in Bandung, Indonesia. Appl. Res. Qual. Life 2011, 6, 159–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).