Can Employee Training Stabilise the Workforce of Frontline Workers in Construction Firms? An Empirical Analysis of Turnover Intentions

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review and Hypothesis

3. Materials and Method

3.1. Questionnaire Design

3.2. Participants and Procedure

3.3. Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling

3.3.1. Evaluation Criteria for Measurement Models

3.3.2. Evaluation Criteria for Structural Models

4. Results

4.1. Common Method Variance

4.2. Measurement Model Assessment

4.2.1. Convergent Validity

4.2.2. Discriminant Validity

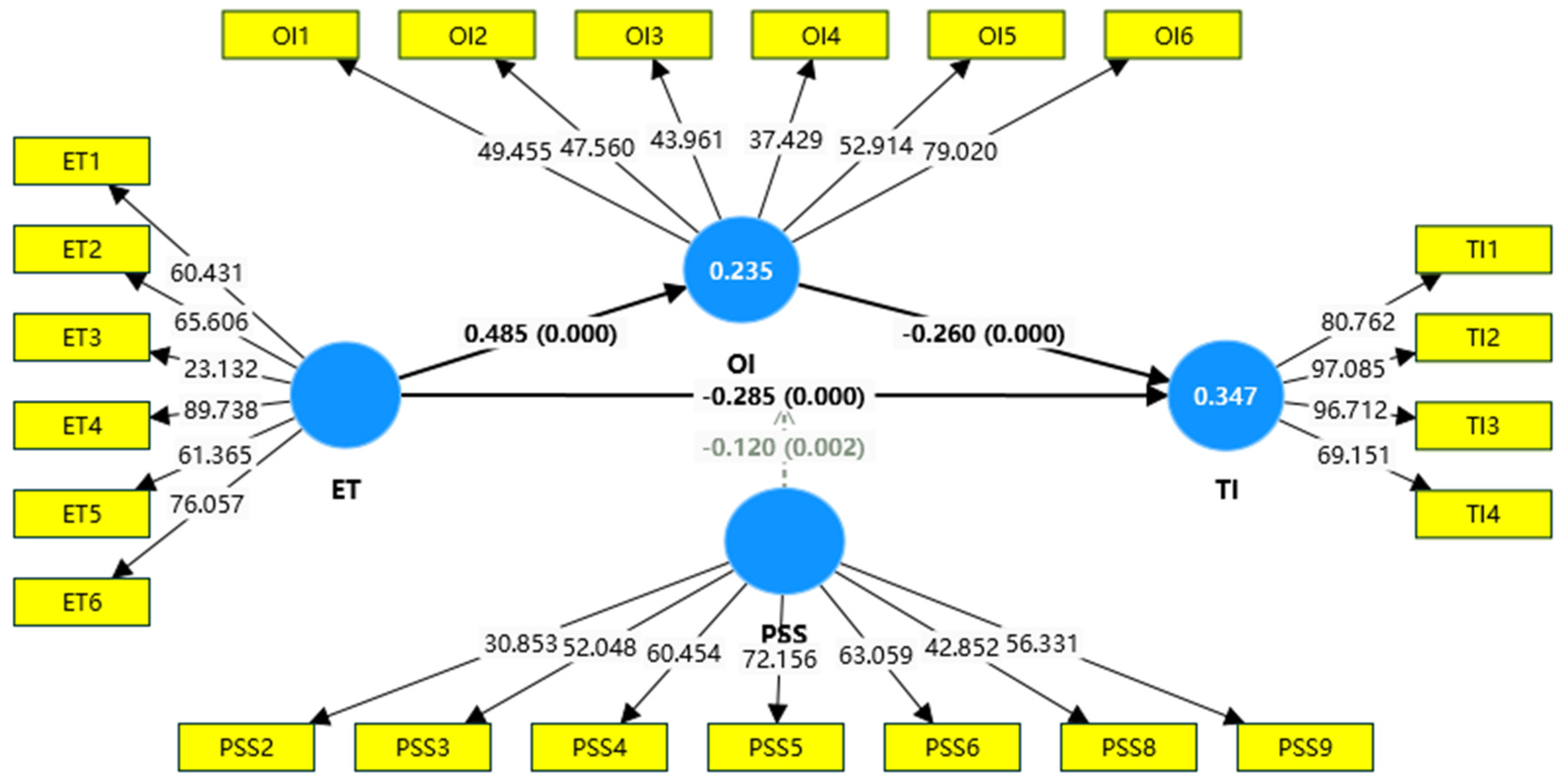

4.3. Final Path Coefficients

4.4. Effect Size and Predictive Power of the Model

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhao, L.; Liu, R. Analysis of the industrial linkage effect of China’s construction industry. In Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Engineering Management and Information Science, EMIS 2023, Chengdu, China, 24–26 February 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z.; Hu, T.; Liu, J.; Xia, B.; Chileshe, N. Spatial differences, evolutionary characteristics and driving factors on economic resilience of the construction industry: Evidence from China. Eng. Constr. Archit. Manag. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, H.; Zhang, Y. Trend analysis of the labor supply and demand in China’s construction industry: 2016–2025. In Proceedings of the 21st International Symposium on Advancement of Construction Management and Real Estate, Hongkong, China, 14–17 December 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Chan, A.P.C.; Chiang, Y.-H.; Wong, F.K.-W.; Liang, S.; Abidoye, F.A. Work–life balance for construction manual workers. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2020, 146, 04020031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minooei, F.; Goodrum, P.M.; Taylor, T.R. Young talent motivations to pursue craft careers in construction: The theory of planned behavior. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2020, 146, 04020082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimi, H.; Taylor, T.R.; Dadi, G.B.; Goodrum, P.M.; Srinivasan, C. Impact of skilled labor availability on construction project cost performance. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2018, 144, 04018057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poon, Y.H. Research on the Development of Construction Safety Liability Insurance Based on Evolutionary Game. Master′s Thesis, Shandong University of Architecture, Jinan, China, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Procore. Construction Safety Statistics. Procore Library. Available online: https://www.procore.com/library/construction-safety-statistics (accessed on 29 December 2024).

- Siddiqui, S. US Construction Worker Fall Accidents: Their Causes and Influential Factors. Master’s Thesis, Florida International University, Miami, FL, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, S. Identifying the Job Characteristics Affecting Construction Firm Employee Turnover Intention. In Proceedings of the Construction Research Congress, Des Moines, IA, USA, 20–23 March 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Ayodele, O.A.; Chang-Richards, Y.; González, V.A. A framework for addressing construction labour turnover in New Zealand. Eng. Constr. Archit. Manag. 2021, 29, 601–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayodele, O.A.; Chang-Richards, A.; González, V. Factors affecting workforce turnover in the construction sector: A systematic review. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2020, 146, 03119010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, D.Y. The Impact of Safety Education and Training on Construction Workers’ Safety Behavior. Master′s Thesis, Chongqing University, Chongqing, China, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dang, H.; Rajendran, S.; Gambatese, J.; Kime, M. Training Development for DEI and Psychological Safety in Construction. In Proceedings of the Construction Research Congress, Des Moines, IA, USA, 20–23 March 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Manresa, A.; Bikfalvi, A.; Simon, A. The impact of training and development practices on innovation and financial performance. Ind. Commer. Training 2019, 51, 421–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afsar, B.; Shahjehan, A.; Shah, S.I. Frontline employees’ high-performance work practices, trust in supervisor, job-embeddedness and turnover intentions in hospitality industry. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2018, 30, 1436–1452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langford, P.H. Measuring organisational climate and employee engagement: Evidence for a 7 Ps model of work practices and outcomes. Aust. J. Psychol. 2009, 61, 185–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shalini, P. A study on investigating the impact of training programs on employee performance and organizational success. Int. Sci. J. Eng. Manag. 2024, 3, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bresk, A. The Impact of Human Resource Training on Employee Turnover in London. J. Hum. Resour. Leadersh. 2023, 8, 36–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arici, A. Prevention of work accidents in construction projects: Strategies and applications. Justicia 2024, 12, 1857–8454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raeisinafchi, R.; Perry, L.A.; Bhandari, S.; Albert, A. Construction Safety Training: Engaging Techniques and Technology Adoption Perspectives. In Proceedings of the Construction Research Congress, Des Moines, IA, USA, 20–23 March 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, N.; Fields, Z.; Chukwuma, N.A. Training, Organisational Commitment and Turnover Intention among Nigerian Civil Servants. J. Econ. Behav. Stud. 2018, 10, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chukwuma, C.A.; Owusuaa-Konadu, C. Employees training and development on organizational performance. Int. J. Manag. Stud. Res. 2022, 3, 749–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siew, C.S.; Huang, S.M.; Mustafa, M.J. Developing employee proactivity in entrepreneurial ventures through training: An organisational identity approach. Eur. J. Train. Dev. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Panda, A.; Kumar Sahoo, C. Impact of human resource interventions on work-life balance: A study on Indian IT sector. Ind. Commer. Train. 2017, 49, 329–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, N. The impact of organizational training and development on the organizational performance. Indian Sci. J. Res. Eng. Manag. 2024, 8, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashforth, B.E.; Mael, F. Social identity theory and the organization. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1989, 14, 20–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Dick, R.; Christ, O.; Stellmacher, J.; Wagner, U.; Ahlswede, O.; Grubba, C.; Tissington, P.A. Should I stay or should I go?: Explaining turnover intentions with organizational identification and job satisfaction. Br. J. Manag. 2004, 15, 351–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilginoğlu, E.; Yozgat, U. Retaining employees through organizational social climate, sense of belonging and workplace friendship: A research in the financial sector. Istanb. Bus. Res. 2023, 52, 67–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barattucci, M.; Teresi, M.; Pietroni, D.; Iacobucci, S.; Lo Presti, A.; Pagliaro, S. Ethical climate(s), distributed leadership, and work outcomes: The mediating role of organizational identification. Front. Psychol. 2021, 11, 564112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaikh, E.; Brahmi, M.; Thang, P.C.; Watto, W.A.; Trang, T.T.N.; Loan, N.T. Should I stay or should I go? explaining the turnover intentions with corporate social responsibility (CSR), organizational identification and organizational commitment. Sustainability 2022, 14, 6030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Giorgio, A.; Barattucci, M.; Teresi, M.; Raulli, G.; Ballone, C.; Ramaci, T.; Pagliaro, S. Organizational identification as a trigger for personal well-being: Associations with happiness and stress through job outcomes. J. Community Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2023, 33, 138–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hur, H.; Ha, H. The link between perceptions of fairness, job training opportunity and at-will employees’ work attitudes: Lessons from US Georgia state government. Eur. J. Train. Dev. 2019, 43, 375–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pradhan, G.M.; Shrestha, P. Impact of Human Resource Management Practices on Organizational Citizenship Behavior in Nepalese Financial Institutions. Nepal. J. Manag. Res. 2022, 2, 12–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dechawatanapaisal, D. Nurses′ turnover intention: The impact of leader-member exchange, organizational identification and job embeddedness. J. Adv. Nurs. 2018, 74, 1380–1391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eisenberger, R.; Stinglhamber, F.; Vandenberghe, C.; Sucharski, I.L.; Rhoades, L. Perceived Supervisor Support: Contributions to Perceived Organizational Support and Employee Retention. J. Appl. Psychol. 2002, 87, 565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nabawanuka, H.; Ekmekcioglu, E.B. Millennials in the workplace: Perceived supervisor support, work–life balance and employee well–being. Ind. Commer. Train. 2022, 54, 123–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenberger, R.; Huntington, R.; Hutchison, S.; Sowa, D. Perceived Organizational Support. J. Appl. Psychol. 1986, 71, 500–507. [Google Scholar]

- Sahu, S.; Pathardikar, A.; Kumar, A. Transformational leadership and turnover: Mediating effects of employee engagement, employer branding, and psychological attachment. Leadersh. Organ. Dev. J. 2018, 39, 82–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marwat, S.A.; Qureshi, M.I.; Ramay, M.I. The Impact of Training on Employee Performance: A Study of the Telecommunication Sector in Pakistan. Int. J. Educ. Manag. 2006, 20, 646–661. [Google Scholar]

- Mael, F.; Ashforth, B.E. Alumni and Their Alma Mater: A Partial Test of the Reformulated Model of Organizational Identification. J. Organ. Behav. 1992, 13, 103–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wayne, S.J.; Shore, L.M.; Liden, R.C. Perceived Organizational Support and Leader-Member Exchange: A Social Exchange Perspective. Acad. Manag. J. 1997, 40, 82–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.; Black, W.; Babin, B.; Anderson, R.E. Multivariate Data Analysis; Pearson Prentice Hall: Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Hult, G.T.M.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM), 2nd ed.; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Ringle, C.M.; Wende, S.; Becker, J.-M. SmartPLS 3; SmartPLS GmbH: Boenningstedt, Germany, 2015; Available online: https://www.smartpls.com (accessed on 19 November 2024).

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacKenzie, S.B.; Podsakoff, P.M. Common method bias in marketing: Causes, mechanisms, and procedural remedies. J. Retail. 2012, 88, 542–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garver, M.S.; Mentzer, J.T. Logistics research methods: Employing structural equation modeling to test for construct validity. J. Bus. Logist. 1999, 20, 33. [Google Scholar]

- Bagozzi, R.P.; Yi, Y. On the evaluation of structural equation models. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 1988, 16, 74–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hulland, J. Use of partial least squares (PLS) in strategic management research: A review of four recent studies. Strateg. Manag. J. 1999, 20, 195–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, W.W. The partial least squares approach to structural equation modeling. Mod. Methods Bus. Res. 1998, 295, 295–336. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mora, M.; Gelman, O. Variance-based structural equation modeling: Guidelines for using partial least squares in information systems research. In Research Methodologies, Innovations and Philosophies in Software Systems Engineering and Information Systems; Roldán, J.L., Sánchez-Franco, M.J., Eds.; IGI global: New York, NY, USA, 2012; pp. 193–221. [Google Scholar]

- Johnston, M.; Dixon, D.; Hart, J.; Glidewell, L.; Schröder, C.; Pollard, B. Discriminant content validity: A quantitative methodology for assessing content of theory-based measures, with illustrative applications. Br. J. Health Psychol. 2014, 19, 240–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rönkkö, M.; Cho, E. An updated guideline for assessing discriminant validity. Organ. Res. Methods 2022, 25, 6–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunnally, J.C. Psychometric Theory 3E; Tata McGraw-Hill Education: Noida, India, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Aidrous, A.H.M.; Shafiq, N.; Al-Ashmori, Y.Y.; Al-Mekhlafi, A.B.A.; Baarimah, A.O. Essential factors enhancing industrialized building implementation in Malaysian residential projects. Sustainability 2022, 14, 11711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ab Hamid, M.R.; Sami, W.; Sidek, M.M. Discriminant validity assessment: Use of Fornell & Larcker criterion versus HTMT criterion. J. Phys. 2017, 890, 012163. [Google Scholar]

- Alnehabi, M. Modeling the association between corporate reputation and turnover intention among banks employees in Saudi Arabia. Int. J. Adv. Appl. Sci. 2023, 10, 30–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Mekhlafi, A.B.A.; Othman, I.; Kineber, A.F.; Mousa, A.A.; Zamil, A.M. Modeling the impact of massive open online courses (MOOC) implementation factors on continuance intention of students: PLS-SEM approach. Sustainability 2022, 14, 5342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shmueli, G.; Koppius, O.R. Predictive analytics in information systems research. MIS Q. 2011, 35, 553–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences, 2nd ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 1988; pp. 20–26. [Google Scholar]

- Urbach, N.; Ahlemann, F. Structural equation modeling in information systems research using partial least squares. J. Inf. Technol. Theory Appl. 2010, 11, 5–40. [Google Scholar]

- Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.M.; Sinkovics, R.R. The Use of Partial Least Squares Path Modeling in International Marketing. Advances in International Marketing; Emerald Group Publishing Limited: Huddersfield, UK, 2009; pp. 277–319. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.; Hollingsworth, C.L.; Randolph, A.B.; Chong, A.Y.L. An updated and expanded assessment of PLS-SEM in information systems research. Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 2017, 117, 442–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.-t.; Bentler, P.M. Fit indices in covariance structure modeling: Sensitivity to under parameterized model misspecification. Psychol. Methods 1998, 3, 424–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumari, S.; Shah, S.; Mishra, N. The Impact of Training and Development on Employee Retention. Int. J. Sci. Res. Eng. Manag. 2022, 6, 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Latorre, F.; Guest, D.; Ramos, J.; Gracia, F.J. High commitment HR practices, the employment relationship and job performance: A test of a mediation model. Eur. Manag. J. 2016, 34, 328–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maulana, A. Peran Pelatihan Konvensional dalam Pengembangan Organisasi dan Dunia Industri. J. Ilm. Manaj. 2023, 14, 199–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, C. Linking frontline construction workers’ perceived abusive supervision to work engagement: Job insecurity as the game-changing mediation and job alternative as a moderator. Eng. Constr. Archit. Manag. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gadi, P.D.; Kee, D.M.H. Workplace bullying, human resource management practices, and turnover intention: The mediating effect of work engagement: Evidence of Nigeria. Am. J. Bus. 2021, 36, 62–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aburumman, O.; Salleh, A.; Omar, K.; Abadi, M. The impact of human resource management practices and career satisfaction on employee’s turnover intention. Manag. Sci. Lett. 2020, 10, 641–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Project | Option | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 463 | 86.9 |

| Female | 70 | 13.1 | |

| Age | Below 20 years | 35 | 6.6 |

| Between 21 and 30 years | 158 | 29.6 | |

| Between 31 and 40 years | 224 | 42.0 | |

| Between 41 and 50 years | 82 | 15.8 | |

| Above 51 years | 32 | 6.0 | |

| Marital Status | Single | 167 | 31.3 |

| Married | 343 | 64.4 | |

| Divorced | 23 | 4.3 | |

| Education Level | High school certificate | 78 | 14.6 |

| Technical certificate | 223 | 41.8 | |

| Diploma | 175 | 32.8 | |

| Degree | 53 | 9.9 | |

| Others | 4 | 0.8 | |

| Monthly income | 3000 yuan and below | 84 | 15.8 |

| 3001–4000 yuan | 190 | 35.6 | |

| 4001–5000 yuan | 125 | 23.5 | |

| 5001–6000 yuan | 63 | 11.89 | |

| 6001–7000 yuan | 41 | 7.7 | |

| Above 7000 yuan | 30 | 5.6 | |

| Years workingin the currentcompany | Below 1 year | 33 | 6.2 |

| Between 1 year and 3 years | 91 | 17.1 | |

| Between 3 years and 5 years | 41 | 7.7 | |

| More than 5 years | 368 | 69.0 |

| Constructs | Indicator | Abbreviation Indicator | Loading |

|---|---|---|---|

| Employee Training | My organization conducts extensive training programs for its employees in all aspects. | ET1 | 0.881 |

| I normally go through training programs every year. | ET2 | 0.886 | |

| In my organization, training needs are identified through a formal performance appraisal mechanism. | ET3 | 0.784 | |

| In my organization, there are formal training programs to teach new colleagues the skills they need to perform their jobs. | ET4 | 0.906 | |

| In my organization, there are formal training programs to teach new colleagues the skills they need to perform their jobs. | ET5 | 0.874 | |

| Training needs identified are realistic, useful and based on the business strategy of the organization. | ET6 | 0.899 | |

| Organizational Identification | When someone criticizes the organization I work for, it feels like a personal insult. | OI1 | 0.848 |

| I am very interested in what others think about the organization I work for. | OI2 | 0.855 | |

| When I talk about the organization I work for, I usually say ‘we’ rather than ‘they’. | OI3 | 0.838 | |

| The successes of the organization I work for are my successes. | OI4 | 0.826 | |

| When someone praises the organization I work for, it feels like a personal compliment. | OI5 | 0.861 | |

| If a story in the media criticized the organization I work for, I would feel embarrassed. | OI6 | 0.902 | |

| Perceived Supervisor Support | My immediate superior shows very little concern for me. (R) | PSS1 | 0.442 |

| My immediate superior strongly considers my goals and values. | PSS2 | 0.813 | |

| My immediate superior cares about my opinion. | PSS3 | 0.880 | |

| My immediate superior is willing to extend himself/herself to help me perform my job to the best of my ability. | PSS4 | 0.874 | |

| My immediate superior really cares about my well-being. | PSS5 | 0.879 | |

| My immediate superior cares about my general satisfaction at work. | PSS6 | 0.877 | |

| Even if I did the best job possible, my immediate superior would fail to notice. (R) | PSS7 | 0.479 | |

| Help is available from my immediate superior when I have a problem. | PSS8 | 0.813 | |

| My immediate superior takes pride in my accomplishments at work. | PSS9 | 0.875 | |

| Turnover Intention | I often think of quitting my job at this company. | TI1 | 0.907 |

| I am seriously thinking about quitting my job at this company. | TI2 | 0.902 | |

| I am actively looking for a job outside this company. | TI3 | 0.898 | |

| As soon as I can find a new job, I will leave this company. | TI4 | 0.900 | |

| I think I will be working at this company for 5 years from now. | TI5 | 0.388 |

| Constructs | Cronbach’s Alpha | CR | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|

| Employee Training | 0.937 | 0.943 | 0.761 |

| Organizational Identification | 0.926 | 0.929 | 0.731 |

| Perceived Supervisor Support | 0.942 | 0.943 | 0.742 |

| Turnover Intention | 0.923 | 0.924 | 0.813 |

| Constructs | Organizational Identification | Perceived Supervisor Support | Employee Training |

|---|---|---|---|

| Organizational Identification | |||

| Perceived Supervisor Support | 0.405 | ||

| Employee Training | 0.516 | 0.256 | |

| Turnover Intention | 0.481 | 0.432 | 0.489 |

| Hypotheses | Path | Path Coefficient (β) | Std. Dev. (STDEV) | T Values | p Values | Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1 | ET -> TI | −0.285 | 0.049 | 5.763 | 0.000 | Supported |

| H2 | ET -> OI | 0.485 | 0.043 | 11.320 | 0.000 | Supported |

| H3 | OI -> TI | −0.260 | 0.054 | 4.792 | 0.000 | Supported |

| H4 | ET -> TI | −0.126 | 0.032 | 3.991 | 0.000 | Supported |

| H5 | PSS × ET -> TI | −0.120 | 0.038 | 3.140 | 0.002 | Supported |

| Predictor | Outcomes | f2 | Q2 | Fitness of Model | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ET | -> OI | 0.235 | 0.307 | 0.168 | |

| ET | -> TI | 0.347 | 0.094 | 0.277 | SRMR = 0.085 NFI = 0.927 |

| OI | -> TI | 0.063 | |||

| PSS | -> TI | 0.067 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yao, W.; Anuar Arshad, M.; Yang, Q.; Tan, J. Can Employee Training Stabilise the Workforce of Frontline Workers in Construction Firms? An Empirical Analysis of Turnover Intentions. Buildings 2025, 15, 183. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15020183

Yao W, Anuar Arshad M, Yang Q, Tan J. Can Employee Training Stabilise the Workforce of Frontline Workers in Construction Firms? An Empirical Analysis of Turnover Intentions. Buildings. 2025; 15(2):183. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15020183

Chicago/Turabian StyleYao, Wenyan, Mohd Anuar Arshad, Qinjie Yang, and Jianping Tan. 2025. "Can Employee Training Stabilise the Workforce of Frontline Workers in Construction Firms? An Empirical Analysis of Turnover Intentions" Buildings 15, no. 2: 183. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15020183

APA StyleYao, W., Anuar Arshad, M., Yang, Q., & Tan, J. (2025). Can Employee Training Stabilise the Workforce of Frontline Workers in Construction Firms? An Empirical Analysis of Turnover Intentions. Buildings, 15(2), 183. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15020183