Abstract

With the intensification of global population aging, attention to the emotional health of the elderly continues to grow. Traditional interior architectural design primarily focuses on optimizing physical functionality; however, this approach is no longer sufficient to meet the increasingly complex emotional needs of the elderly. Integrating the Three-Level Theory of Emotional Design (TTED) into interior design provides a significant opportunity to systematically address the multidimensional needs of the elderly. However, existing research is often fragmented and lacks thematic literature reviews to summarize the key factors, characteristics, and design strategy frameworks of interior design. This study aims to evaluate the impact of interior design on the emotional experiences of the elderly and to construct a conceptual framework to address current research gaps. By establishing rigorous selection criteria, 39 high-quality studies were identified from the Scopus, Web of Science, and Mendeley databases. Using ATLAS.ti 9 for thematic analysis, five core themes were distilled: aesthetics, use and function, emotional reflection, design strategies, and emotional experience. The findings revealed that architectural interior design practices often paid limited attention to the emotional needs of older adults. Through a comprehensive literature review, 10 key design features were identified, including multi-sensory attributes, morphological characteristics, cultural elements, and natural components, alongside 17 related research directions. The study introduces a dynamic feedback mechanism within the framework of the proposed architectural interior design strategy, highlighting the importance of employing multiple strategies that balance and complement each other in practical applications. Additionally, the study clarifies future research directions, offering theoretical support and practical guidance for designers to address the complex needs of the elderly. This achievement provides a systematic reference for the future development of interior architectural design and has significant implications for improving the emotional experience of the elderly.

1. Introduction

According to data from the World Health Organization, the population aged 60 and above is growing faster than any other age group in nearly every country [1]. This trend has led to extensive research focused on improving the health and well-being of older adults [2]. As people age, they undergo physical, cognitive, and emotional changes, which require adaptive adjustments in the built environment [3]. While physical accessibility has traditionally been the primary focus of housing design for the elderly, growing evidence highlights the critical role of emotional comfort in residential environments in enhancing the well-being of older adults [4].

However, current interior design practices often prioritize structural upgrades and functional improvements while overlooking the subtle emotional and psychological needs of elderly residents [5]. Research indicates that older adults are more reliant on their living environments than younger individuals [6]. As people age and experience a decline in personal abilities, older adults face increasing pressure to adapt to the interior conditions of their homes. They increasingly require interior environments that support their daily lives, making such support essential [7]. Brasche and Bischof [8] found that individuals aged 65 and above spend an average of 19.5 h per day at home, more than any other age group, highlighting the neglect of their specific interior design needs. Therefore, there is an urgent need for tailored interior support spaces to meet the unique requirements of elderly residents. Interior design issues directly affect the physical health and well-being of older adults [9]. With physiological changes, many older adults often feel overwhelmed by their living environments and perceive their interior spaces as insufficiently comfortable. This sense of helplessness exacerbates emotional distress, underscoring the importance of incorporating emotional experience considerations into interior design for the elderly.

In this context, emotional design has gradually become a critical area of research. Norman [10] proposed the concept of emotional design, which centers on deliberately creating products and environments that evoke positive emotional responses, enhancing user experience and subtly influencing behavior [10,11,12,13]. The Three-Level Theory of Emotional Design (TTED) comprises visceral, behavioral, and reflective levels [12], offering an intuitive, comprehensive, and robust emotional analysis framework for design. This theory not only addresses the visceral and behavioral levels (such as aesthetic and functional factors) but also integrates profound considerations of human care at the reflective level. However, current architectural interior design remains predominantly technology-driven. While it emphasizes modernity in visual effects, it often neglects the emotional and psychological needs of users. This technology-centric approach shows significant limitations, particularly in addressing the diverse needs of people from different cultural and social backgrounds. The application of TTED not only effectively bridges the gap between human-centered care and interior design but also offers a structured and scalable framework for exploring multilayered emotional needs. Its universality and flexibility play a vital role in enhancing emotional well-being and happiness. It is precisely this adaptability that establishes TTED as the core theoretical foundation of this study.

Xu and Wu [14] categorized emotional needs into three levels—aesthetic, functional, and reflective—based on Norman’s emotional design theory. They also outlined corresponding interior environmental characteristics for each need. According to Maslow’s hierarchy of needs, emotional needs are hierarchical, with higher-level needs emerging once lower-level needs are met [15]. Therefore, when an indoor environment’s functional and aesthetic needs are fulfilled, it is essential to also address reflective needs. Functional needs encompass the usability and accessibility of space, which are critical considerations for older adults. Features such as non-slip flooring and ergonomically designed furniture play a key role in enhancing safety, comfort, and independence [16]. Aesthetic needs relate to the emotional satisfaction derived from the visual and sensory quality of the environment. The effective use of color schemes, textures, and harmonious spatial design can positively affect mood and well-being, promoting feelings of tranquility and connection to the environment [17]. Reflective needs involve identity, memory, and personal meaning and can be supported through design elements that evoke nostalgia, pride, and a sense of belonging—especially for older adults dealing with loneliness or loss. Personalizing spaces with meaningful objects, familiar materials, or culturally relevant designs can foster emotional comfort and satisfaction. This study argues that by deeply expanding and analyzing aesthetic, functional, and reflective needs, the key factors and characteristics influencing the emotional experiences of elderly individuals in architectural interior design can be systematically identified. This not only highlights promising research directions for future researchers but also offers valuable practical references for designers, contributing to the creation of interior environments that better support the emotional needs of the elderly.

While explicit needs can be relatively easily addressed through design, implicit needs remain difficult to quantify due to their complexity and subjectivity [18]. Designers need to deeply understand the unique physical and emotional challenges faced by older adults while comprehensively grasping their personal needs and preferences to create supportive interior environments [19]. In recent years, researchers have increasingly applied the TTED framework to better analyze emotional needs. For instance, Yang, et al. [20] used TTED to evaluate smart product systems. Xu and Wu [14], drawing on Norman’s emotional design theory, divided emotional needs into three levels: visceral, behavioral, and reflective. Similarly, Yu, et al. [21] employed TTED to assess children’s furniture design, categorizing needs into appearance, functionality, and emotional experience. Kongprasert and Butdee [22] proposed an emotion-driven design method for leather products, analyzing the features that make handbags appealing to users. Zheng, et al. [23] noted a lack of emotional design in children’s hospital environments, while Wang, et al. [24] addressed challenges in street facility design by categorizing user emotional needs using TTED and the Kano model. These studies highlight the potential of TTED as a robust framework for exploring and refining emotional needs. To identify emotional needs, researchers have adopted diverse methods such as interviews and the Kano model. While these varied approaches broaden the scope of inquiry, they also risk creating inconsistencies in how design features and influencing factors are understood. Furthermore, the diversity of application contexts and target user groups has made it difficult to systematically summarize design features and key influencing factors. A thematic review is, therefore, necessary to integrate these scattered findings and distill common design characteristics and critical factors.

In recent years, the impact of interior design on the emotional experiences of older adults has become a research focus, yet most studies remain limited to analyzing the relationship between single design factors and emotions. Jung, et al. [25] investigated the use of interior colors for older adults in Arab regions and explored their potential impact on depression. Similarly, Stevens, et al. [26] studied the design and color preferences of older adults in care facilities. Kosti, et al. [27] integrated emotion and aesthetics into the design of virtual reality (VR) social spaces, finding that this approach significantly stimulated positive cognition, emotional experiences, and memory recall in older adults. Meanwhile, Song [28] used AI-based robotic vision technology to study real-time emotion monitoring in nursing homes, providing positive emotional support, particularly for patients with mental health issues. The application of these technologies not only enhances the practical value of research but also offers efficient and convenient solutions for researchers. Hung, et al. [29] evaluated changes in the physical environment of a dining area in a nursing facility in Edmonton, Canada, identifying key factors for enhancing residents’ dining experiences, such as fostering independence and autonomy, creating familiar and pleasant environments, providing social spaces, and adapting to challenges of change. These findings offer valuable insights for designing dining areas in residential spaces. Raanaas, et al. [30] explored how residents in residential rehabilitation centers experienced landscapes through windows and indoor plants. Their research showed that natural landscapes and indoor plants enhanced residents’ reflective abilities, sense of meaning, and feelings of being cared for, thereby improving well-being and resilience to stress. This finding further underscores the positive role of natural elements in the emotional well-being of older adults. These studies provide a theoretical foundation for comprehensively analyzing the factors and characteristics that influence older adults’ emotional experiences. Through an in-depth literature review, the commonalities and core design characteristics of current research findings can be distilled, providing scientific evidence for subsequent design practices and aiding in the comprehensive fulfillment and optimization of older adults’ emotional needs.

In summary, this study aims to explore the significant impact of architectural interior design on the emotional experiences of older adults and systematically analyze the design factors and their characteristics that influence emotional needs. By integrating the TTED framework into interior design, this study incorporates the emotional needs of older adults into a holistic design approach. This approach aims to help designers gain a deeper understanding of the profound impact of interior design strategies on the emotional experiences of the elderly. Currently, this field lacks systematic thematic analysis. This review proposes a holistic design approach aimed at addressing existing academic gaps and promoting further development in this area. To achieve these objectives, this paper proposes and focuses on the following research questions:

- RQ1: What are the current trends in interior design related to the emotions of older adults?

- RQ2: How to formulate a new framework for interior design that supports the emotional experience of the elderly for the future direction of this strategy?

To provide greater clarity on the focus and structure of this study, the content is organized as follows: Section 2 introduces the research methodology, detailing the thematic analysis process using Mendeley and ATLAS.ti 9. Section 3 presents the results of the analysis, which are divided into quantitative and qualitative components. The quantitative analysis examines the literature data from a numerical perspective, while the qualitative analysis extracts five core themes through coding and summarizes their impact on emotional experiences. Section 4 proposes an architectural interior design strategy framework based on the results of the thematic analysis. Finally, Section 5 discusses the academic contributions, limitations, and directions for future research.

2. Materials and Methods

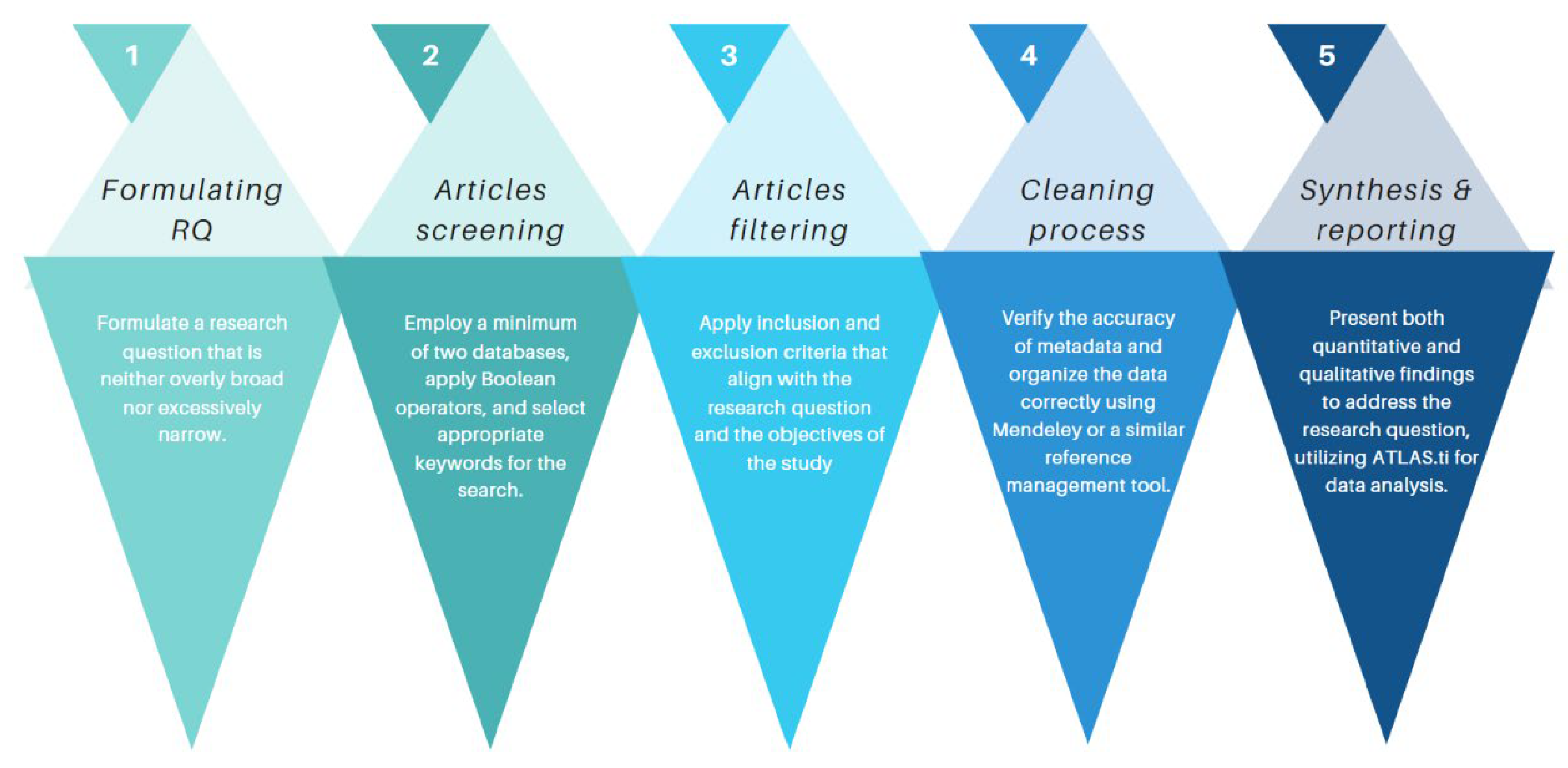

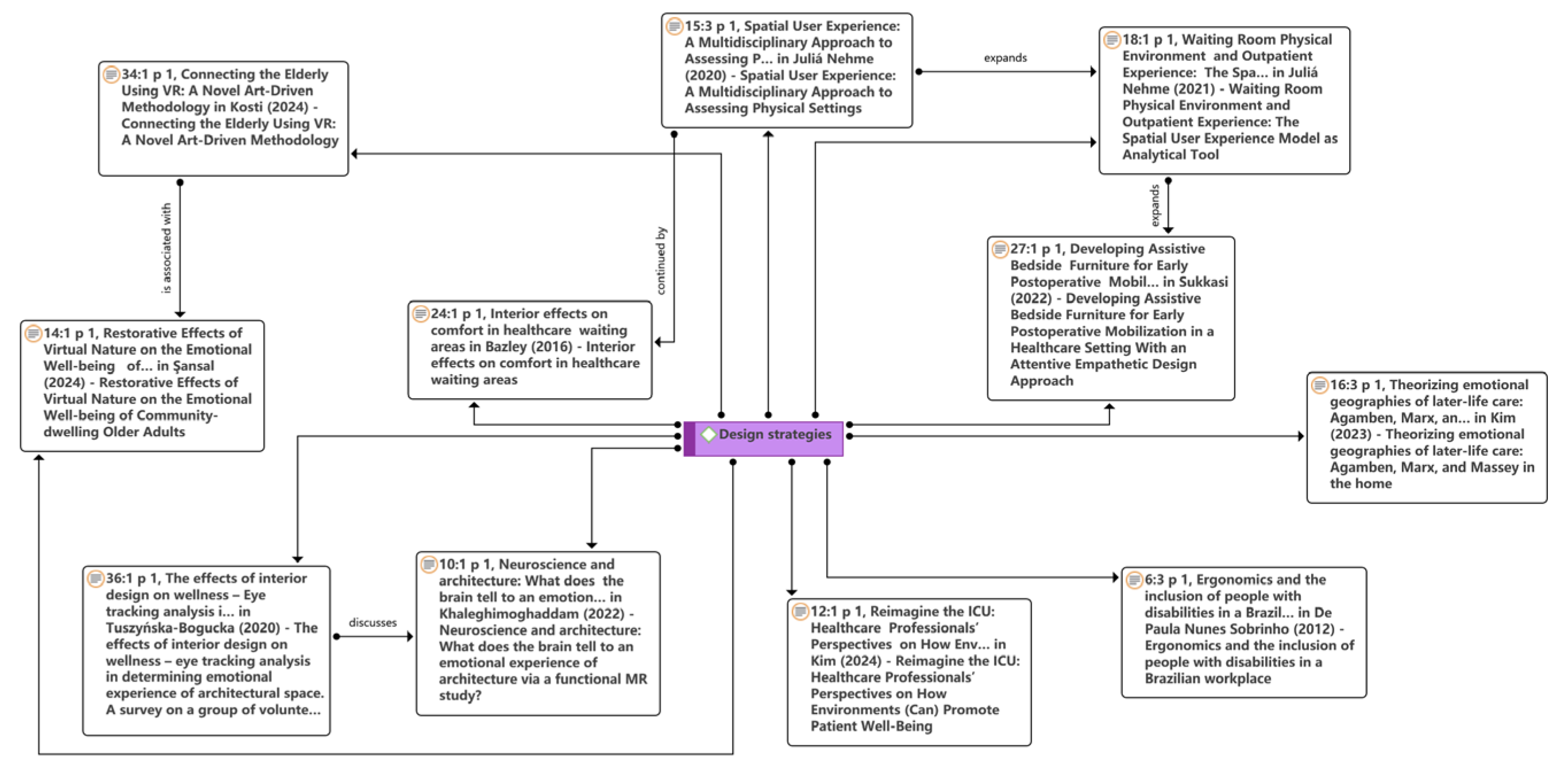

In this study, we used the ATLAS.ti 9 software to conduct a thematic review, systematically identifying, analyzing, and integrating key themes and patterns from the literature [31]. Thematic review (TR) is a literature review method that aims to identify and construct meaningful themes through a systematic analysis of existing research [32]. We chose the TR method because it allows for an organized and rigorous approach to analyzing literature, following standardized thematic analysis procedures [31,33,34] (see Figure 1). This approach enables researchers to gain an in-depth understanding of key themes in the existing literature, identify research gaps, and provide direction for future studies. Braun and Clarke [35] highlighted that a thematic review involves recognizing patterns and constructing themes based on a comprehensive reading of relevant research data.

Figure 1.

Thematic review methodology step [31,33,34].

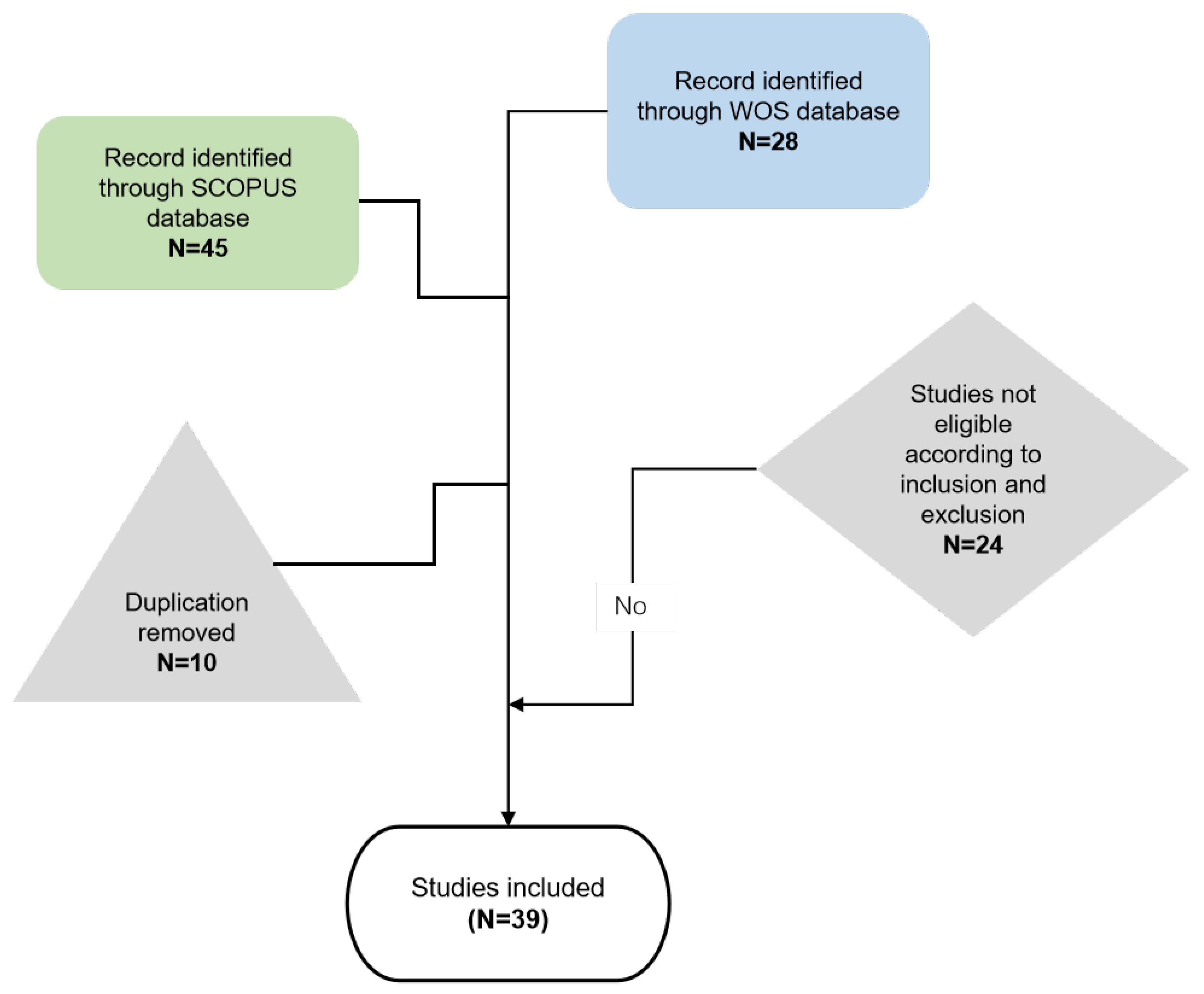

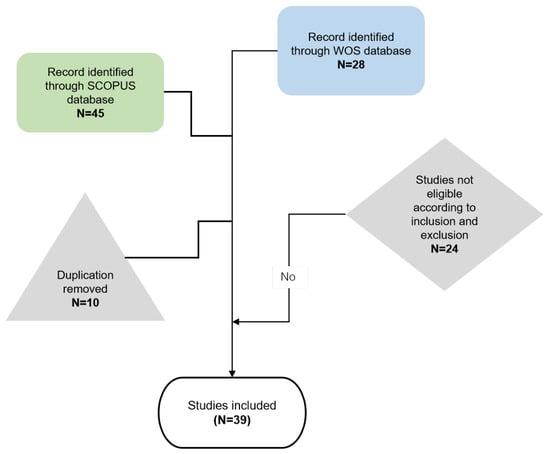

This study primarily retrieved data from the SCOPUS and Web of Science (WOS) databases. The Web of Science Core Collection is a widely recognized citation index that tracks relationships between publications, offering valuable insights into key literature and research trends [36]. Scopus was selected for its extensive coverage of peer-reviewed articles, while Web of Science was chosen for its inclusion of all indexed journals in the Journal Citation Reports (JCR) with impact factors [37]. Many peer-reviewed articles in Scopus and Web of Science can also be found in other databases like Google Scholar. Therefore, these two databases were deemed to provide a comprehensive coverage of relevant literature on indoor environments for the elderly. In Scopus, filters were applied to titles, abstracts, and keywords, restricting the selection to articles and reviews in English. Similar criteria were used for the WOS database, resulting in the identification of 45 articles from Scopus and 28 from WOS (see Table 1). The study employed the exclusion criteria proposed by Zairul [38] to screen the records. After merging the search results from both databases, duplicate entries were removed, leaving unique records for analysis. A total of 10 duplicates were identified and excluded, followed by the removal of 24 articles that did not align with the research focus (see Figure 2).

Table 1.

Search strings from Scopus and WoS.

Figure 2.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria using thematic review method.

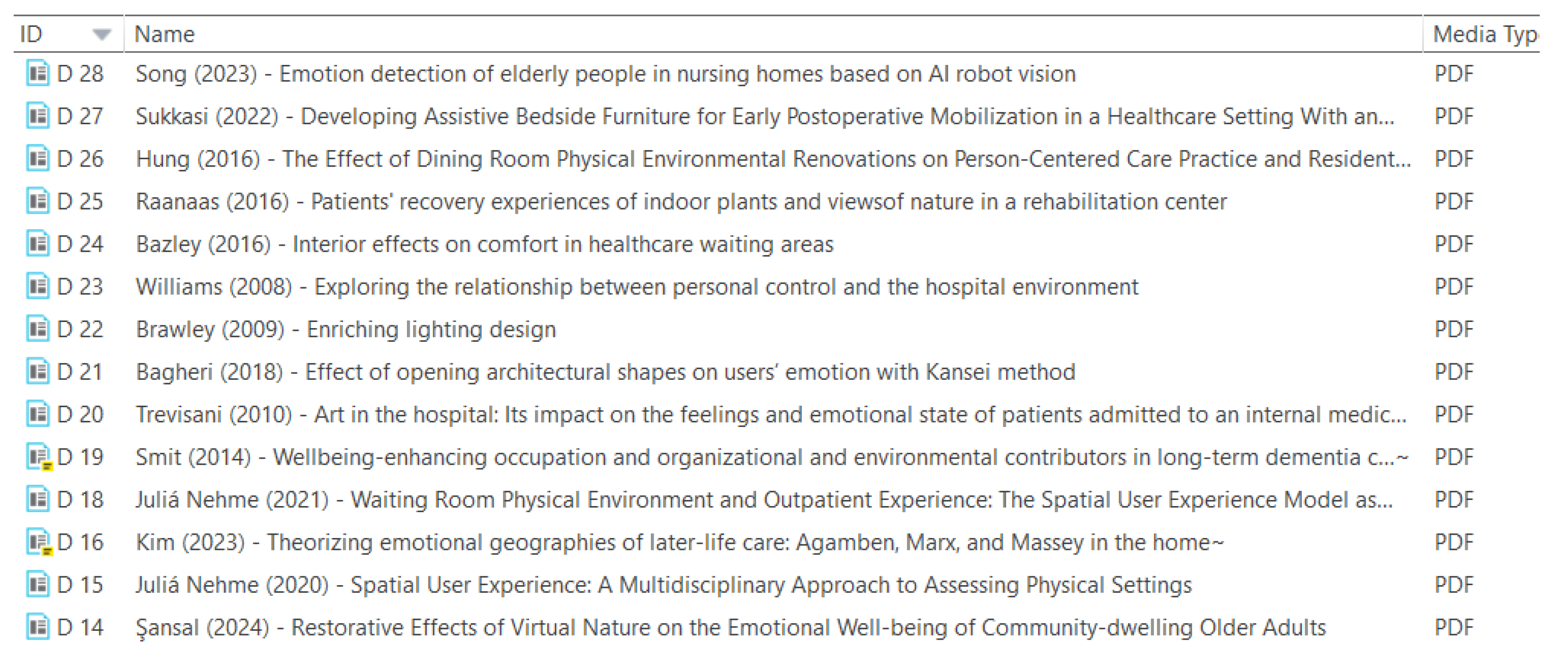

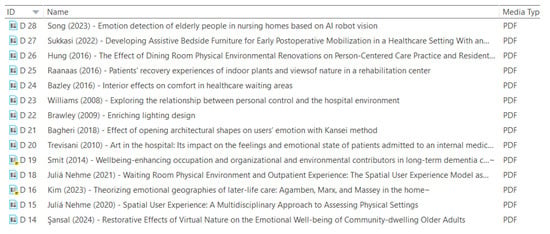

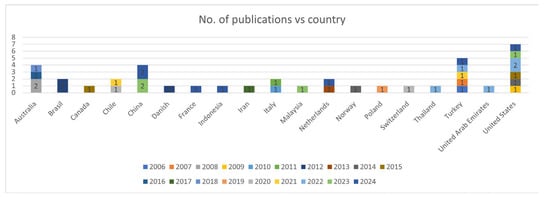

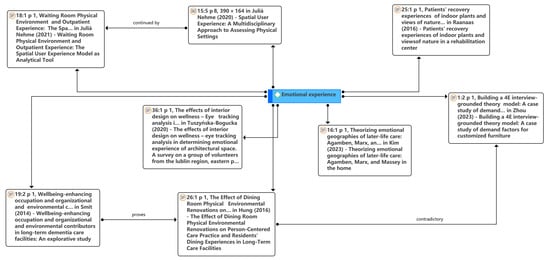

The remaining articles were uploaded to Mendeley for data processing, which included removing duplicates, verifying author names, and ensuring all metadata—such as publication dates and journal names—were accurate. A total of 39 articles were then exported to ATLAS.ti 9 for analysis. Various bibliometric data were extracted from the documents, including article titles, publication years, author affiliations, author countries, journal names, key terms, and thematic areas (see Figure 3). The findings of this study include both quantitative and qualitative components. The quantitative analysis presents numerical data, while the qualitative analysis identifies themes within the selected articles. Together, these components help construct a conceptual framework for integrating emotional design principles into architectural interior design.

Figure 3.

Metadata generated in ATLAS.ti 9.

3. Results

This section presents the key findings from the thematic review, evaluated through both quantitative and qualitative analyses. The quantitative analysis examines the data from a numerical perspective, while the qualitative analysis identifies themes within the selected literature. Together, these components contribute practical insights into designing emotionally supportive interior environments for the elderly, adding to the existing body of knowledge.

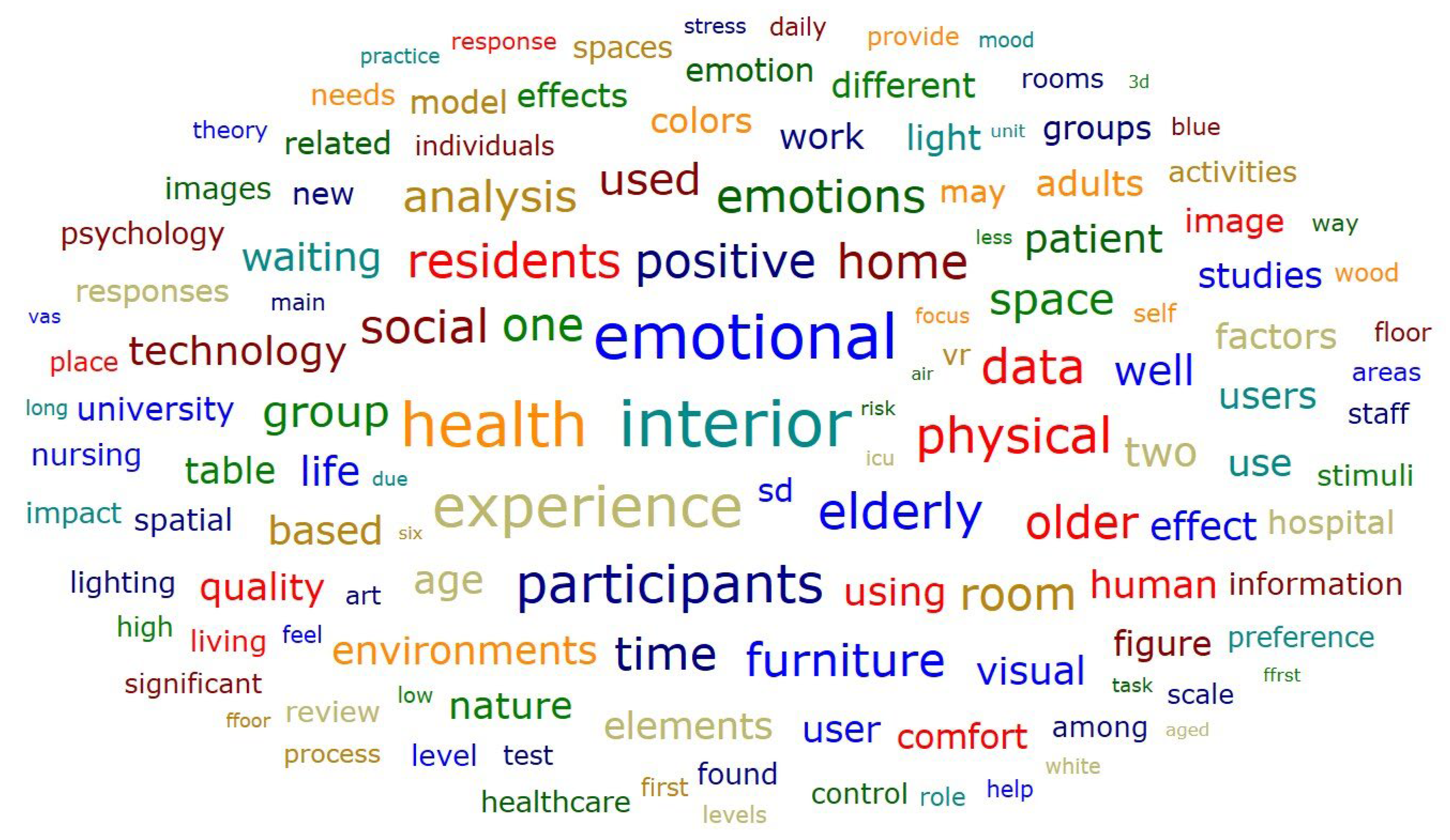

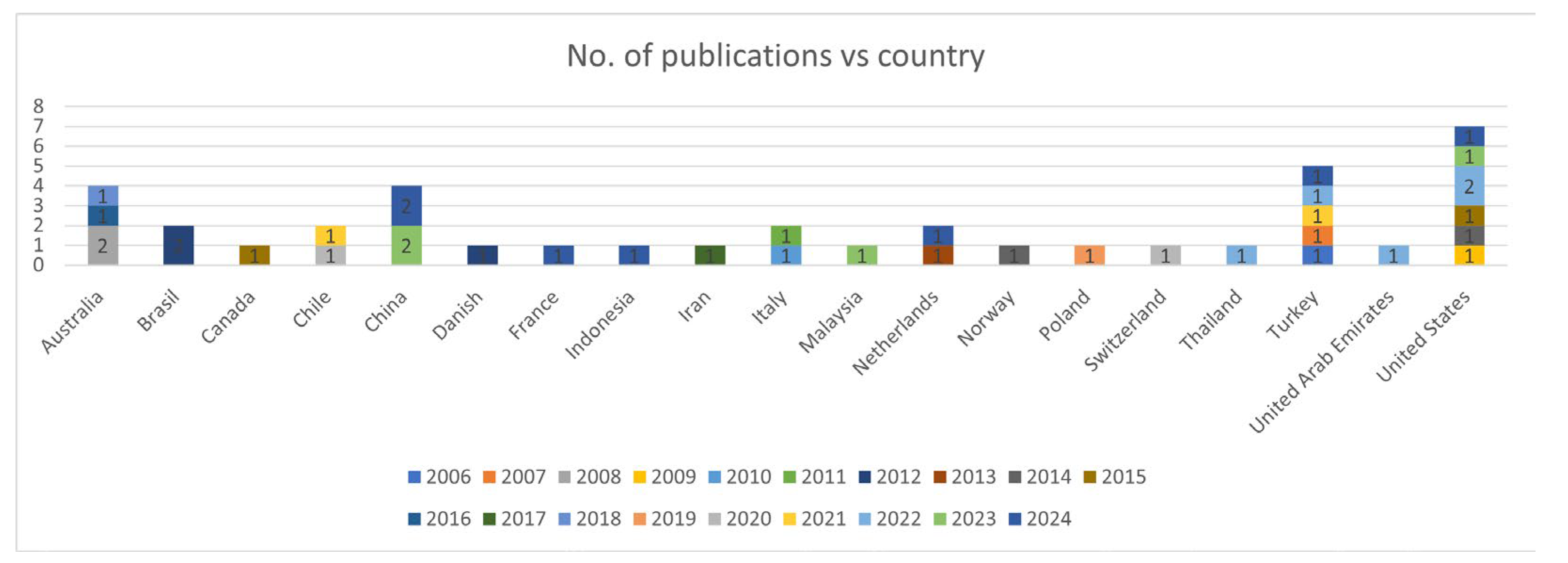

The quantitative analysis supports the thematic evaluation in the qualitative component. The first research question (RQ1) is addressed through quantitative analysis, while the second research question (RQ2) is explored using qualitative analysis. Based on the analysis of 39 core articles, a word cloud was generated to visually represent the frequency of key terms. “Interior” and “emotional” were the most prominent, with 655 and 622 mentions, respectively. Other frequently mentioned terms include “health” (604 mentions) and “experience” (565 mentions), emphasizing the study’s focus on interior design related to the emotional well-being of the elderly (see Figure 4). The number of publications has shown a general increase over the years, with no relevant literature published before 2006. Since then, there has been a notable rise in publications in key years, including 2022 (five publications) and 2024 (seven publications so far). Given the limited number of studies retrieved, the authors chose not to impose a time restriction on the search, ensuring a comprehensive coverage of relevant content for the research questions.

Figure 4.

Word cloud on word frequencies from 36 documents.

3.1. Quantitative Findings

The analysis shows that architectural researchers, interior design professionals, and healthcare scientists have published in a diverse range of journals. Among these, Work, Environments Research and Design Journal and Journal of Interior Design are the most popular (see Table 2). The study found a strong link between design elements and the emotional experience of the elderly, suggesting significant potential for future research. Notably, there has been an increase in articles using the term “emotion-related architectural interior design for the elderly” in 2024, indicating a growing interest in this subject. However, the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic continues to influence the future spatial needs of the elderly.

Table 2.

Number of articles according to periodicals and papers reviewed by year.

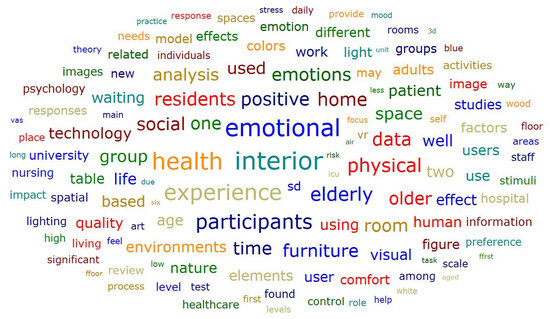

From a geographical perspective, research on architectural interior design and elderly emotional well-being has increased significantly in developed countries, particularly in the United States, which has published the highest number of studies. These studies mainly explore the impact of interior design on emotions, health, and comfort, focusing on healthcare and elderly care environments. For example, Mirkia, et al. [39] analyzed biotic and abiotic spaces in the United States and their effects on emotions. Brawley [40] highlighted the importance of lighting design in supporting the daily activities of the elderly and reducing fall risks, especially through appropriate light intensity and color temperature. Bazley, et al. [41] studied the comfort design of medical waiting areas in the southern United States, incorporating spatial perception and ergonomics from both Eastern and Western perspectives, emphasizing “sense of place” and “sense of balance”. Kim, et al. [42] suggested that monitoring elderly individuals’ daily activities can enhance their health and well-being.

Apart from the United States, Turkey contributed five articles, while Australia and China each published four. In Australia, Smith [43] investigated the impact of color on human psychological responses and environmental perception. In Turkey, Şansal, et al. [44] examined the effects of virtual reality natural scenes, such as VR videos and images, on emotional recovery in elderly individuals living in urbanized areas. In Asia, China has begun applying relevant research findings to improve the living environments of older adults. For example, studies have explored the effects of furniture design on the emotions and health of elderly individuals [45,46]. Additionally, Song [28] highlighted the potential of artificial intelligence (AI) vision technology to detect the emotional states of elderly individuals. The disparity in contributions can be attributed to varying levels of research infrastructure and focus. Countries like the United States and Australia have long-standing traditions of investing in research on aging populations, supported by abundant resources and well-established interdisciplinary frameworks. Additionally, these nations face advanced stages of population aging, driving a stronger emphasis on innovative solutions. On the other hand, China, despite ranking third globally in terms of international contributions to this field, has only recently accelerated its research efforts. Most of its studies were conducted within the past three years, reflecting a nascent but growing interest driven by the rapid aging of its population and the unique challenges faced by developing countries. This recent surge highlights China’s increasing recognition of the need for context-specific research to address its aging-related challenges, even as it works to build a more robust research infrastructure (see Figure 5).

Figure 5.

The number of publications vs. country.

A broad definition of the intersection between architectural interior design and elderly emotional well-being was used to identify key focus areas within academia. Through a comprehensive review of the literature, 46 items were coded, and five core themes were identified, which will be discussed in detail in the qualitative section. Overall, this section addresses Research Question 1 (RQ1).

3.2. Qualitative Results

In the qualitative section, this paper will explore in detail the themes derived to address the research questions. Following a comprehensive review of the relevant literature, qualitative analysis was conducted to clarify the key themes related to elderly emotional well-being and architectural interior environments. Each selected article was coded to identify the theories and concepts extensively studied by scholars in this field. Based on this analysis, five themes were identified: T1 (Aesthetics), T2 (Use and Function), T3 (Emotional Reflection), T4 (Design Strategies), and T5 (Emotional Experience). These themes are interconnected, and some articles may involve multiple themes, which is a common occurrence (see Table 3).

Table 3.

Authors according to the themes.

Table 3.

Authors according to the themes.

| Reference | Aesthetic | Design Strategies | Emotional Experience | Emotional Reflection | Function and Use |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [46] | √ | √ | |||

| [47] | √ | √ | |||

| [48] | √ | ||||

| [43] | √ | ||||

| [49] | √ | ||||

| [50] | √ | ||||

| [19] | √ | ||||

| [51] | √ | ||||

| [52] | √ | √ | |||

| [39] | √ | ||||

| [53] | √ | √ | |||

| [54] | √ | ||||

| [44] | √ | √ | |||

| [55] | √ | √ | √ | ||

| [56] | √ | √ | |||

| [57] | √ | √ | |||

| [58] | √ | √ | |||

| [59] | √ | ||||

| [18] | √ | √ | |||

| [40] | √ | ||||

| [60] | √ | ||||

| [41] | √ | √ | √ | ||

| [30] | √ | √ | |||

| [29] | √ | ||||

| [61] | √ | √ | |||

| [28] | √ | ||||

| [62] | √ | ||||

| [63] | √ | ||||

| [26] | √ | ||||

| [64] | √ | ||||

| [65] | √ | ||||

| [27] | √ | √ | |||

| [45] | √ | ||||

| [66] | √ | √ | √ | ||

| [3] | √ | ||||

| [25] | √ | √ | |||

| [42] | √ | ||||

| [67] | √ | ||||

| [68] | √ |

The next section will discuss these themes individually and provide an in-depth exploration to answer Research Question 2: How to formulate a new framework for interior design that supports the emotional experience of the elderly for the future direction of this strategy? This discussion will be followed by the development of a conceptual framework.

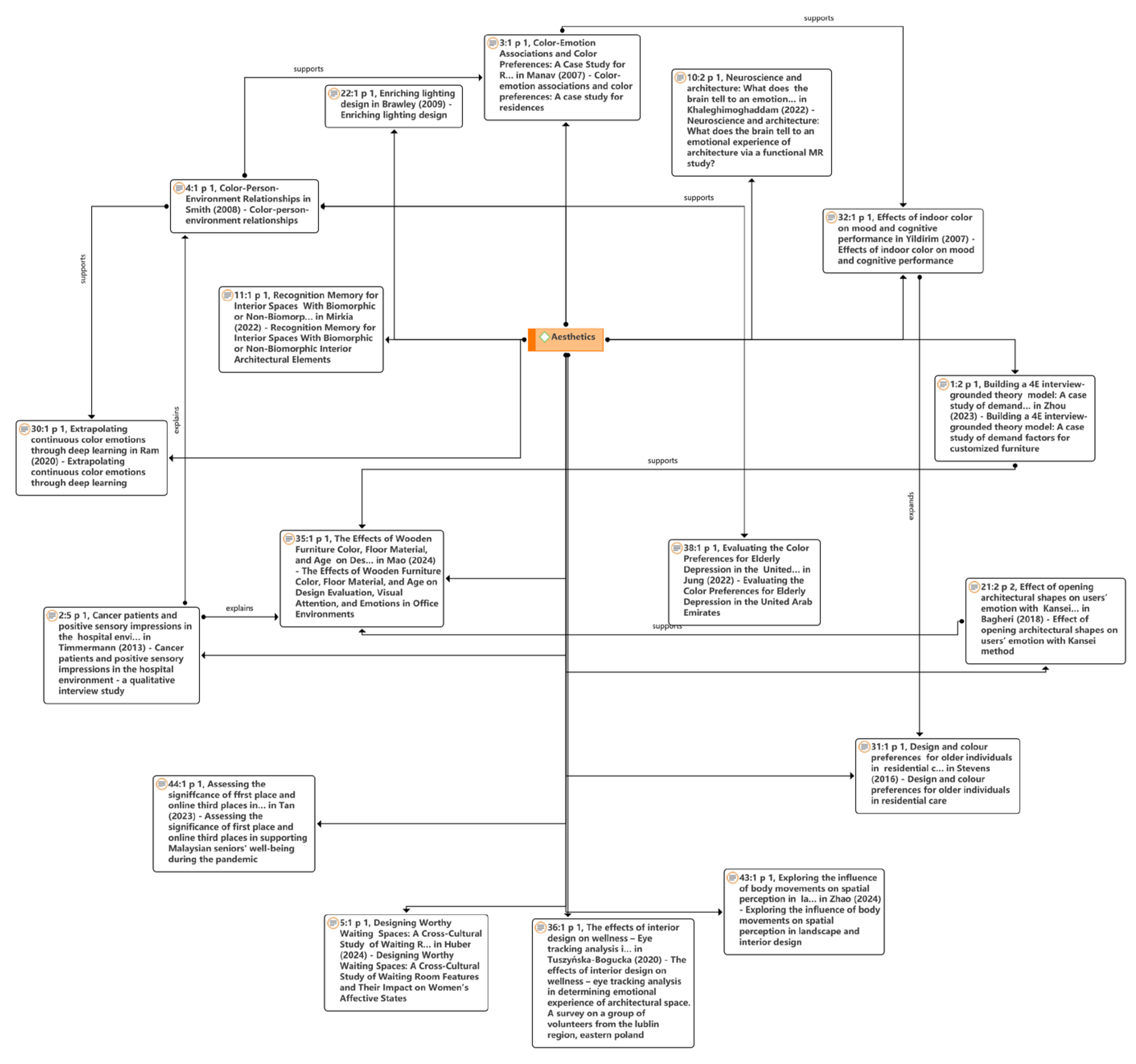

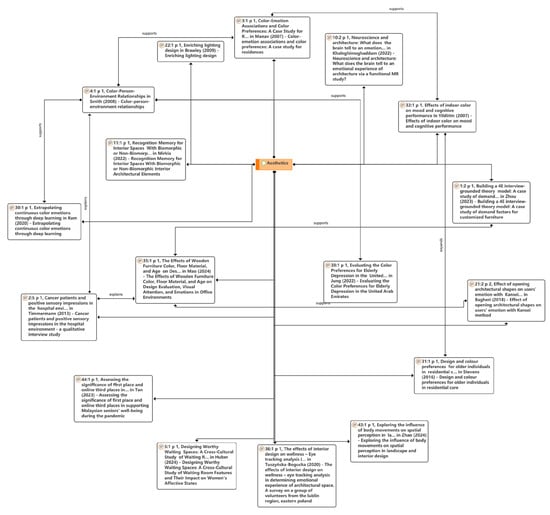

3.2.1. Aesthetics

Numerous studies have shown that aesthetic experiences rely on multiple sensory inputs. Vision, hearing, touch, smell, and taste are the primary ways humans interact with their environment, with vision being the dominant sense responsible for about 80% of emotional experiences [66]. Sensory characteristics, such as color, light, scent, sound, and texture, directly influence the perception of beauty and sensory enjoyment in architecture [52]. Positive sensory impressions have also been found to help reduce pain and stress in patients [47,69].

Color plays a significant role in visual aesthetics [63]. Jaglarz [70] suggested that the use of color in architecture and interior design played a critical role in the health of older adults, influencing their spatial perception, behavior, and activities. Smith [43] noted that color enhances the relationship between individuals and their environment, while Manav [48] explored color as a means of communication to meet residential needs. The effects of interior color use, gender, and age on emotional and cognitive responses are also noteworthy [25,64,71]. Stevens, Fröis, Masal, Winder and Bechtold [26] found that creating a comfortable and cozy environment helps reduce negative emotions, while familiar colors and patterns can evoke positive memories among the elderly.

Indoor lighting is another essential element that can compensate for sensory deficiencies. Brawley [40] emphasized that individuals with physical and mental impairments often rely heavily on their environment to compensate for sensory limitations, such as impaired vision, which affects their daily and social activities. Typical lighting in many care environments fails to meet the visual and circadian rhythm needs of elderly individuals, impacting their sleep and increasing susceptibility to depression. Additionally, Jaglarz and Chrzanowski [72] argued that lighting is a particularly important aspect of spatial design for older adults, and proper lighting can enhance their quality of life by (1) positively impacting their well-being, (2) promoting their engagement in activities, and (3) ensuring health and safety. For instance, adequate lighting can help older adults avoid falls.

Furniture also holds multiple layers of sensory implications. Vision is the primary means of perceiving furniture, influencing how people view its appearance, color, and texture. People’s responses to furniture are shaped by the combined attractions of touch, hearing, and smell [46]. Mao, Li and Hao [45] investigated the effects of wooden furniture color, flooring materials, and age on emotional responses in office environments. Their findings indicated that the combination of wooden flooring and brown furniture elicited the strongest emotional responses, including pleasure, admiration, and fascination. Elderly individuals particularly showed a preference for the texture of wood.

The morphological characteristics of interior spaces, such as shapes and geometric configurations, also play a significant role in aesthetics and emotions. Features like volume, proportion, height, and geometric shapes contribute to the visual composition of a space and evoke emotional responses [52]. Streamlined designs with circular and curved forms are often associated with comfort, while sharp lines and angles can evoke tension [73]. Bagheri and Shahroudi [18] explored the impact of open architectural forms on emotions, finding that arched openings were more effective in evoking religious sentiments, whereas rectangular openings were linked to economic settings. Mirkia, Nelson, Abercrombie, Thorleifsdottir, Sangari and Assadi [39] showed that biomorphic elements in interior spaces positively influence spatial memory and visual attention, creating a more pleasant experience. Furthermore, Wang, Cho and Hong [68] explored the impact of interior environmental elements on attention and creativity in his research. Zhao [67] found that vertical elements, such as walls, have a stronger impact on attention.

Cultural and artistic elements also play an important role in fulfilling aesthetic and emotional needs. Using specific cultural symbols or artistic styles can evoke a sense of identity and belonging. Decorative elements with historical or regional characteristics enhance emotional connections to a space, fostering a sense of familiarity and safety [74]. Integrating culture and emotions in design not only adds aesthetic value but also fulfills deeper emotional needs. Huber and Bailey [49] explored a cross-cultural study on waiting room characteristics and their effects on women’s emotional states.

Visual aesthetics is an important consideration in architectural interior design. Elements such as color, texture, lighting, materials, scent, furniture, as well as morphological and cultural elements, collectively contribute to creating a rich visual experience that influences emotions (see Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Network on the aesthetics theme.

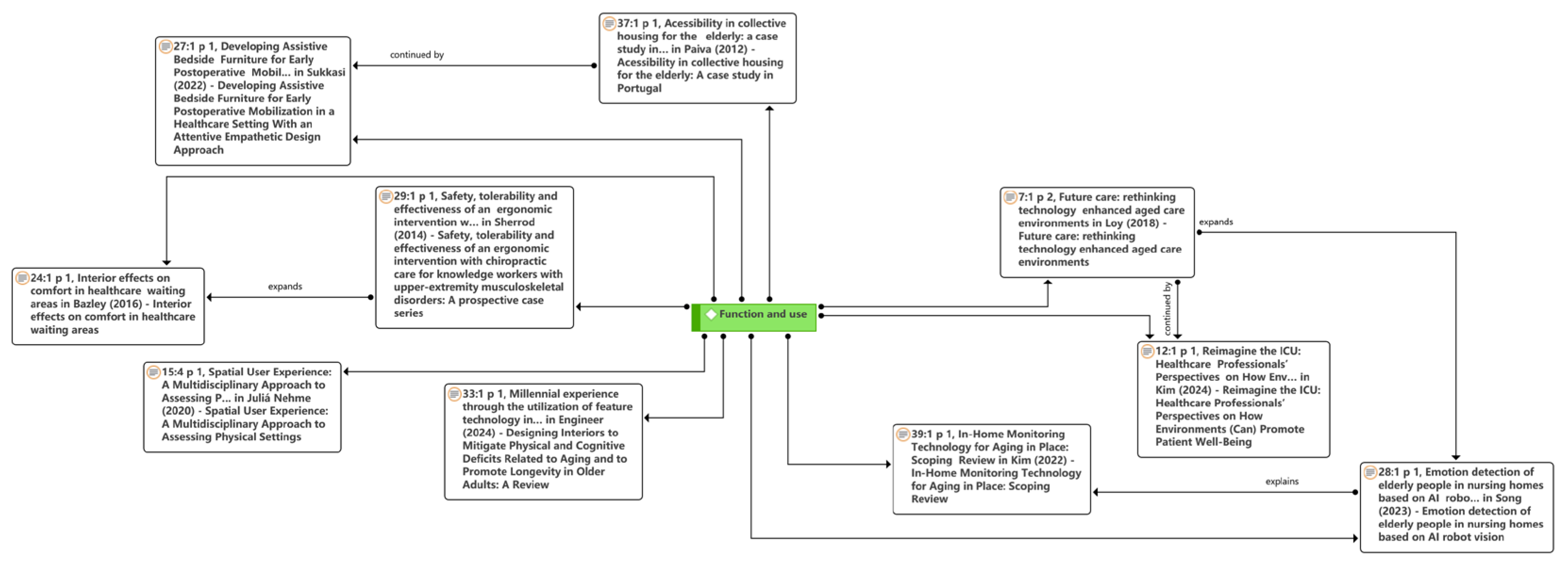

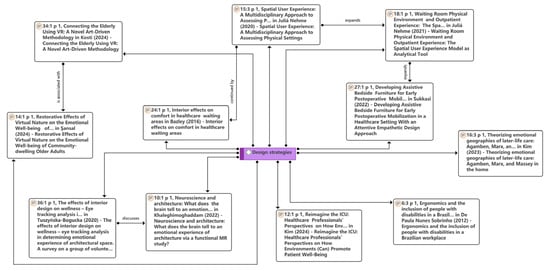

3.2.2. Use and Function

The function and use of architecture are closely linked to the application of ergonomics, which not only enhances functionality but also significantly impacts the emotional experiences of users, particularly the elderly. As people age, physical flexibility, strength, and sensory acuity decline, making ergonomic design essential for improving comfort and safety in daily life [3,65]. Juliá Nehme, Rodríguez and Yoon [55] summarized the Spatial User Experience (SUE) model, in which ergonomics is a major dimension encompassing spatial cognition, physical compatibility, and environmental compatibility. Sukkasi, Tunnukit and Lerspalungsanti [61] highlighted the importance of empathy in ergonomic design, developing bedside assistive furniture to reduce the physical burden on elderly patients and assist in safe movement. Ergonomic designs that enhance autonomy, such as accessible environments, significantly contribute to the psychological satisfaction and sense of dignity of elderly users. Villarouco [75] proposed the Ergonomics Method for the Built Environment (EMBE) as a framework to optimize physical infrastructure for elderly needs. Additionally, Sherrod, Johnson and Chester [62] demonstrated that ergonomic interventions improved both the work experience and productivity of individuals with disabilities or mobility impairments. Collectively, these studies highlighted the important role of ergonomics in improving the functionality of interior design, as well as alleviating anxiety in older adults.

Modern technology also plays a role in improving the functionality and efficiency of buildings, enabling elderly individuals to live more independently. Loy and Haskell [19] suggested reconsidering the role of technology in enhancing future care environments for the elderly. Advancements in artificial intelligence (AI) have introduced new design approaches for monitoring psychological changes and alleviating negative emotions in the elderly. For example, Song [28] developed an AI monitoring system designed to detect negative emotions and enhance quality of life, sleep, activity levels, and emotional experiences. The study’s findings revealed that the AI-driven emotion detection system was more effective than manual interventions in eliciting positive emotions and improving mood among older adults. These intelligent devices adapt to the habits and needs of older adults, enhancing autonomy and comfort [28,76].

Home monitoring technology has become a new strategy for modifying homes to support aging-in-place. Monitoring daily activities positively affects the health and well-being of elderly individuals [42]. Interactive immersive projection technology expands the content of physical surfaces, creating dynamic visual stimuli that adjust to the changing emotional needs of patients [53,77]. Kim, der Heide, van Rompay and Ludden [53] proposed four strategies for therapeutic environments: making clinical processes visible to patients, fostering connections with family, creating calming wake-up and sleep experiences, and personalizing positive sensory interventions.

The spatial layout of architectural interiors affects not only usability but also safety for the elderly. Iyendo, et al. [78] found that open layouts, natural lighting, and soft color schemes reduce stress and enhance relaxation—factors especially important in aging-in-place environments. Open circulation designs minimize obstacles, reduce fall risks, and improve psychological safety for older adults [79]. Spatial fluidity and harmony with the environment are key factors influencing comfort [41]. As the needs of older adults evolve with age, interior design must focus on aesthetics, functionality, accessibility, and creating a dynamic experience throughout the aging process (see Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Network on the use and function theme.

However, while the appropriate use of smart technologies enhances the functionality and usability of indoor environments, benefiting both workers and users, their applicability is not universal, particularly in environments where social resources and cultural contexts differ significantly. To address these variations, this study emphasizes that the proposed design strategies and approaches should not be considered in isolation. Instead, they must be integrated with other design features, strategies, or approaches to ensure adaptability. When a specific design factor cannot be applied to a particular environment, it should be complemented by alternative design strategies to achieve the intended outcomes.

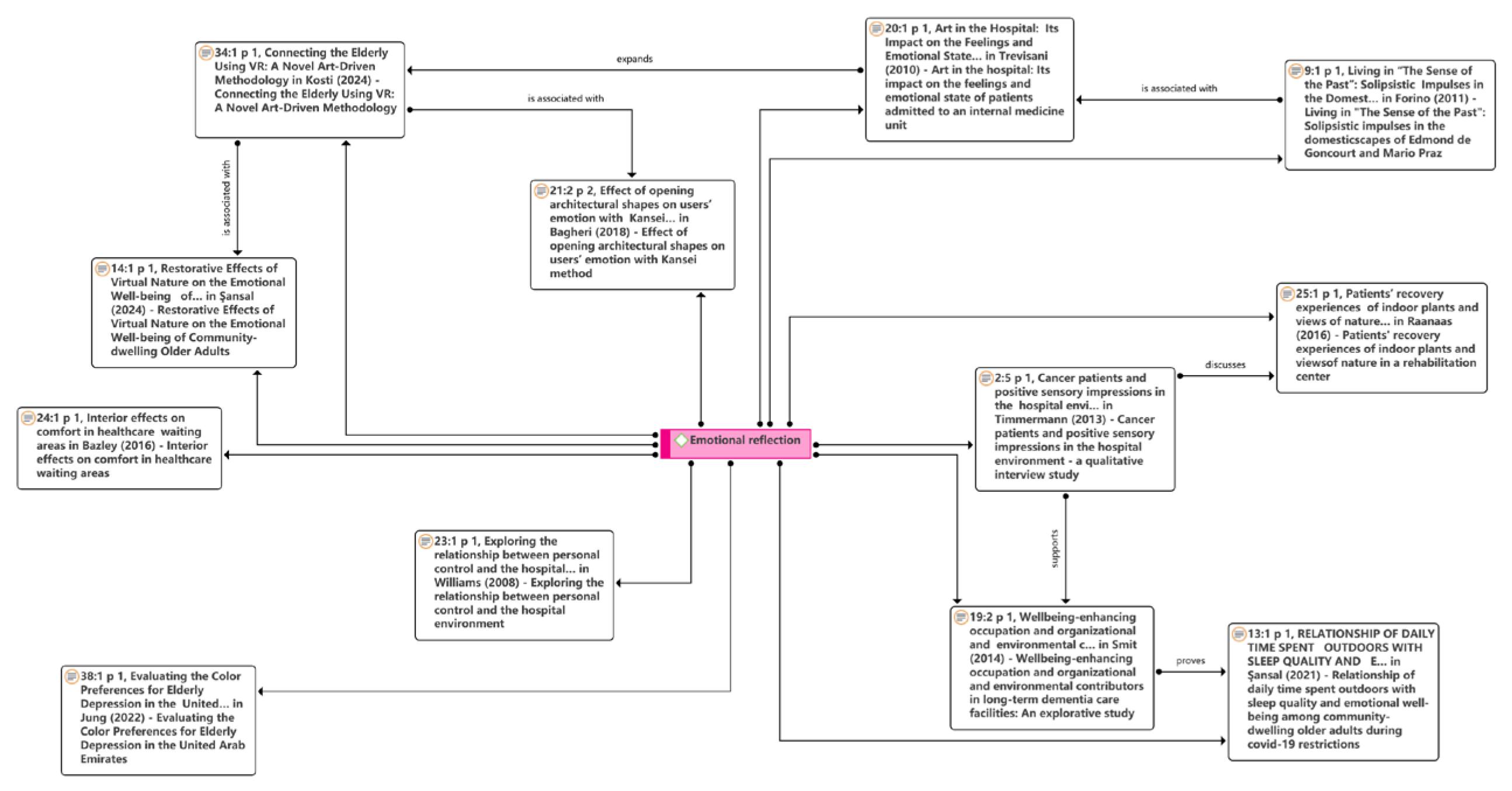

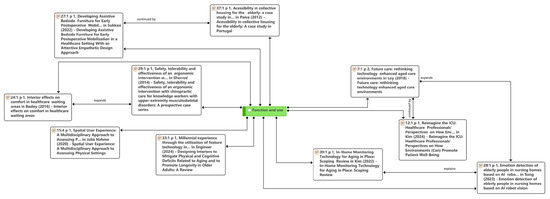

3.2.3. Emotional Reflection

Emotional reflection is a process that allows elderly individuals to explore and revisit their life journeys, reassessing both achievements and regrets. This reflection involves self-exploration, fulfilling needs for identity, self-worth, memory, and personal meaning by incorporating elements into design that mirror users’ values, cultural significance, or life experiences. Such design elements can evoke nostalgia, pride, or a sense of belonging (see Figure 8). Personalized sensory design is one effective strategy to foster positive reflective experiences. For example, plants in indoor environments can provide meaningful opportunities for reflection. In a study conducted at a Norwegian rehabilitation center, residents reported that indoor plants and views of nature promoted relaxation and positive feelings, aiding in reflection and contemplation [30]. Views through windows and the presence of indoor plants also fostered a sense of meaning and care, contributing to overall well-being and helping individuals cope with life stress [30]. For those living in high-density urban environments, virtual nature has been shown to effectively restore emotional well-being [44]. Similarly, art used to beautify therapeutic spaces has been found to positively impact elderly well-being, with studies demonstrating that photographs in clinical spaces enhance patients’ adaptation to hospitalization [59]. Direct contact with nature also plays a key role in improving mental health [44,54].

Figure 8.

Network on the emotional reflection theme.

Emotional reflection helps elderly individuals maintain a connection to their past and sustain a sense of purpose. Viewing natural scenes, for example, can help elderly individuals recall significant memories from childhood or other meaningful periods, contributing to their sense of identity and providing a foundation for creating meaning in life [47]. Reminiscing has been shown to enhance overall well-being [58]. Natural landscapes, in particular, provide a temporary escape from negative emotions, especially for those experiencing challenging health conditions [47,54]. For some, these connections with nature evoke positive memories and personal life experiences, aiding in rediscovering a sense of identity. Kosti, Benayoun, Georgakopoulou, Diplaris, Pistola, Xefteris, Tsanousa, Valsamidou, Koulali and Shekhawat [27] argued that, for elderly individuals, symbolic experiences that combine historical facts with memory restoration can create deeper emotional connections, promoting harmony with their values and identity. Moreover, studies have found that virtual navigation can enhance memory, improving both source memory and episodic recall.

The process of emotional reflection not only alleviates anxiety during life transitions but also helps build a positive self-perception. According to Erikson’s theory of psychosocial development, late adulthood is characterized by a conflict between “ego integrity” and “despair”. Reflecting on past experiences allows elderly individuals to cultivate a sense of integrity, reducing fears related to death and the future [80]. The study in [60,81] found that allowing elderly individuals to control their surroundings in care facilities significantly improves their physical and mental health. Similarly, Crocker and Park [82] emphasized that a sense of personal control fosters emotional comfort, reducing anxiety and enhancing self-worth.

Some researchers have argued that positive emotional reflection can encourage users to embrace cultural values. Incorporating elements that reflect users’ cultural backgrounds in design helps foster emotional connections and enhance a sense of belonging. Day, et al. [83] examined the influence of cultural relevance on elderly individuals in care environments and found that design elements resonating with their cultural backgrounds—such as traditional artworks or cultural symbols—can evoke a “collective memory” [51], aiding the elderly in adapting to new surroundings. Older adults tend to prefer colors associated with their cultural backgrounds, whereas younger individuals select colors based on varying perspectives, trends, and emotions [25,84]. Cultural backgrounds and cognitive responses significantly influence color preferences [25]. Bagheri and Shahroudi [18] found that arched openings are linked to religious culture and a sense of trust, while rectangular openings are associated with stability. These findings suggest that cultural elements can evoke a sense of belonging and identity, thereby enhancing emotional connections to space. This cultural identity is particularly crucial for maintaining mental health and emotional stability, especially in long-term residency or high-stress environments. Bazley, Vink, Montgomery and Hedge [41] applied Eastern Feng Shui principles to create a sense of place and balance in comfortable architectural design.

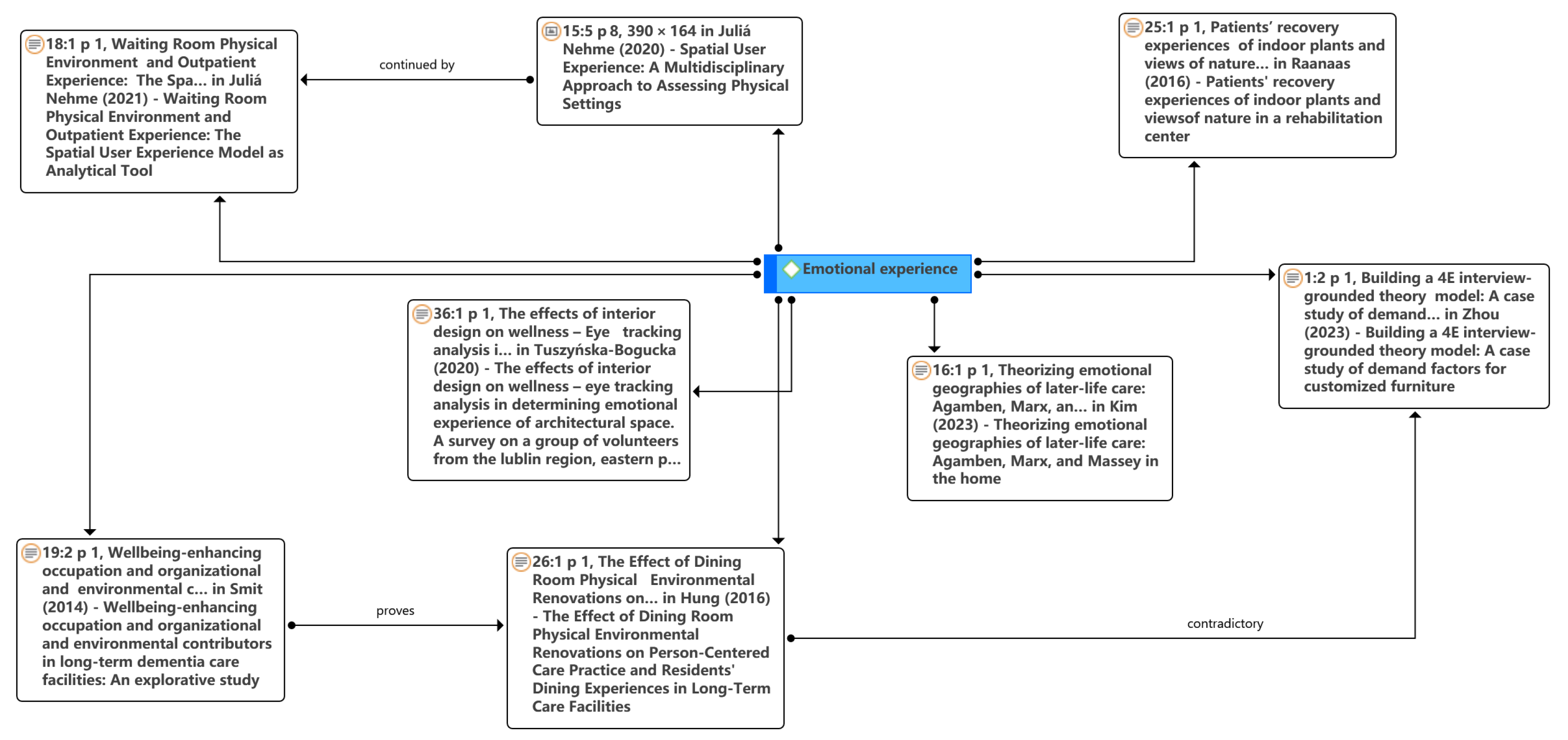

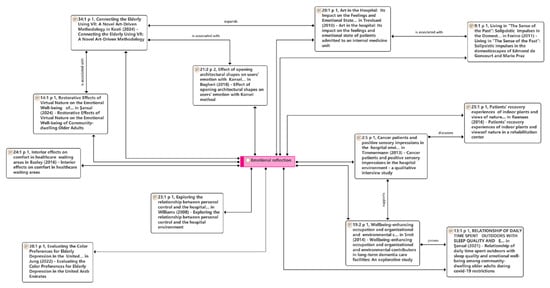

3.2.4. Design Strategies

Adaptive resource strategies aim to enhance the positive emotional experiences of elderly individuals by effectively utilizing existing resources. By optimizing resource allocation through technology, interior spaces can achieve both emotional appeal and functionality. Khaleghimoghaddam, Bala, Özmen and Öztürk [52] used functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) to capture emotional responses to architectural environments, while Tuszyńska-Bogucka, Kwiatkowski, Chmielewska, Dzieńkowski, Kocki, Pełka, Przesmycka, Bogucki and Galkowski [66] employed eye-tracking technology to evaluate the emotional impact of interior design on users, demonstrating how design elements can promote emotional well-being. These studies highlight that the flexible application of technology and the dynamic optimization of design approaches can better address the diverse emotional needs of the elderly. Virtual reality (VR) technology presents new opportunities to support emotional health in older adults. Kosti, Benayoun, Georgakopoulou, Diplaris, Pistola, Xefteris, Tsanousa, Valsamidou, Koulali and Shekhawat [27] proposed an innovative approach that integrates artists and creative thinkers to explore the quality, emotional characteristics, and functional applicability of age-friendly environments. Their research utilized art-driven VR experiences to alleviate feelings of loneliness and isolation among elderly individuals and their families, fostering social connections. Similarly, Şansal, Şimşek, Aktan, Özbey and Paksoy [44] introduced virtual nature technologies to increase opportunities for elderly individuals in urban environments to connect with nature, providing a fresh perspective for creating emotionally enriched urban spaces.

Further research has explored enhancing emotional experiences through multidisciplinary integration (see Figure 9). Juliá Nehme, Rodríguez and Yoon [55] and Bazley, Vink, Montgomery and Hedge [41] showed that combining ergonomics with emotional considerations can improve the usability of spaces. Juliá Nehme, Torres Irribarra, Cumsille and Yoon [57] further examined the design of medical waiting areas, demonstrating that optimizing spatial layouts can enhance comfort and reduce patient anxiety. These studies illustrated how user experience models can balance functionality with emotional support. However, the complexity of these models presents challenges for designers, who must integrate knowledge from various fields and meet diverse needs with limited resources. Moreover, Kim [56] studied emotional experiences in elderly care, combining concepts such as Marx’s theory of alienation, Agamben’s idea of bare life, and Massey’s spatial politics. Additionally, Kim, der Heide, van Rompay and Ludden [53] used evidence-based design (EBD) to examine how curved and straight elements in interior spaces influence visual preferences. Overall, effective design strategies should integrate technology, functionality, cultural context, and scientific evidence to better meet users’ diverse needs.

Figure 9.

Network on the design strategy’s theme.

Some studies have explored design strategies that combine ergonomics with other design theories. Sukkasi, Tunnukit and Lerspalungsanti [61] highlighted the importance of empathy in ergonomic design by developing a bedside assistive furniture piece that reduces the physical burden on elderly patients and helps them move safely. By addressing users’ emotional, psychological, and sociocultural needs, this design integrates emotional and functional aspects, enhancing patients’ independence and confidence while reducing reliance on caregivers and improving their rehabilitation experience. de paula Nunes Sobrinho and de Lucena [50] examined how ergonomics can support the integration of people with disabilities into workplaces in Brazil. Although their study focused on work environments, the insights are valuable for inclusive design in elderly-friendly architecture. Inclusive design aims to adapt tasks and environments to suit the abilities and needs of disabled individuals while ensuring their health, safety, and quality of life.

This study highlighted the positive impact of sustainability-driven strategies on enhancing the emotional experiences of elderly individuals. The use of natural materials such as wood and bamboo can significantly increase the warmth and comfort of interior spaces [85]. Research has shown that incorporating natural light has a profound effect on improving the emotional state and cognitive function of older adults [78,86]. Jaglarz [70] emphasized the importance of considering the influence of color on the surrounding environment as well as on individual physiological and psychological well-being when designing sustainable living environments for the elderly. The study suggested drawing inspiration from nature to optimize color design. For instance, strategies such as incorporating large windows, creating seamless transitions between indoor and outdoor spaces, offering scenic views, enhancing greenery, implementing efficient lighting designs, and adjusting brightness and spaciousness can effectively enhance the functionality of colors and the overall appeal of the environment. Moreover, the integration of intelligent interactive technologies with sustainable materials is a promising area for future exploration. This combination could provide elderly individuals with dynamic and emotionally adaptive interior environments.

In addition, this study emphasized that these methods are components of a broader research strategy rather than stand-alone solutions and that multiple methods are needed to complement each other when resource conditions do not apply.

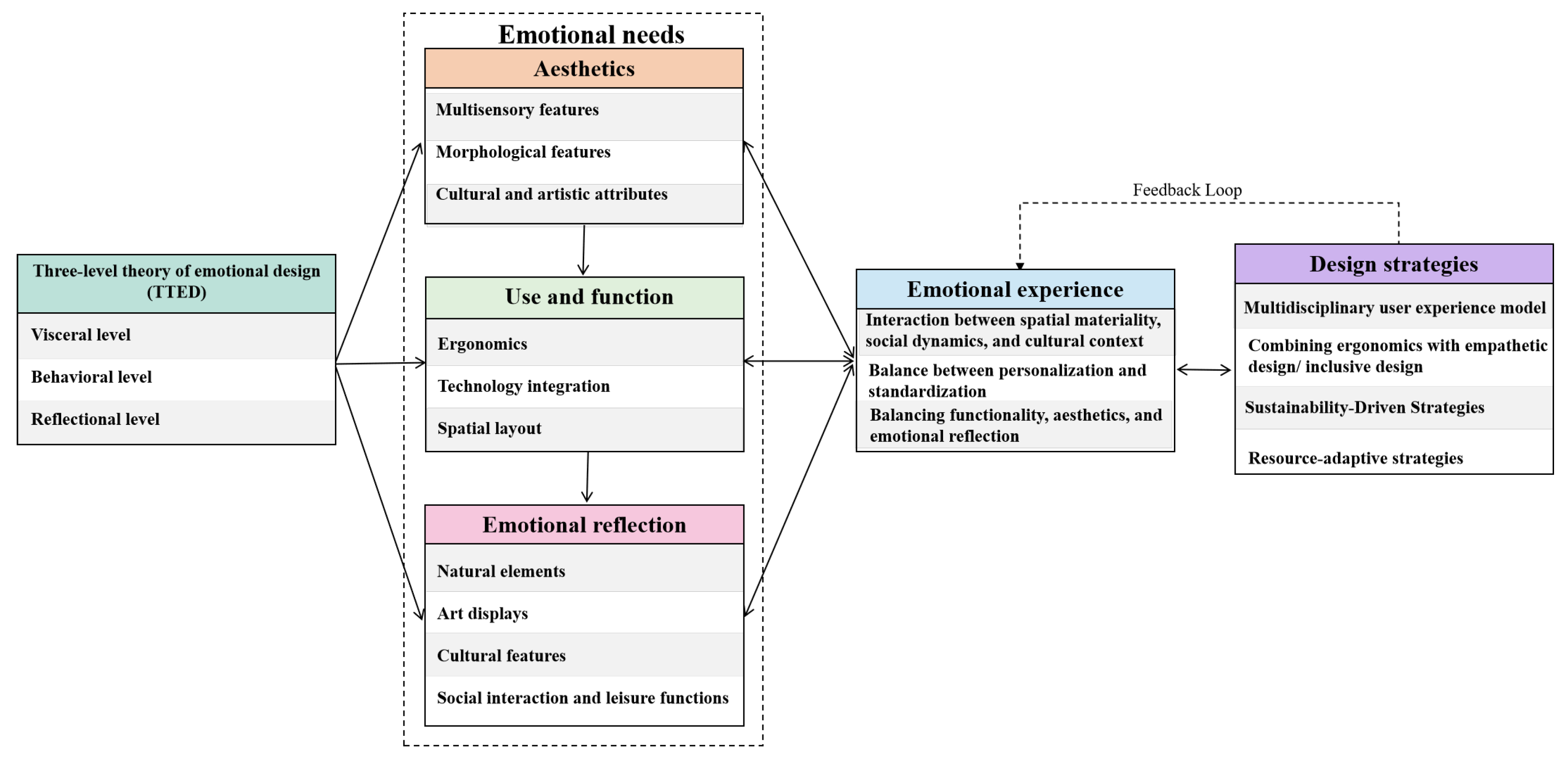

3.2.5. Emotional Experience

Some studies have investigated how the physical environment impacts emotional experiences, especially in medical settings. And Juliá Nehme, Rodríguez and Yoon [55] examined outpatient facilities and their effect on patient experiences, later proposing a spatial user experience model to evaluate outpatient care quality. However, Hung, Chaudhury and Rust [29] and Smit, Willemse, de Lange and Pot [58] stressed the need for standardized solutions in institutional environments to ensure safety and efficiency. In contrast, Zhou, Gu, Luo and Kaner [46] advocated for personalized design, suggesting that incorporating personal elements can evoke stronger positive emotions. This raises the challenge of balancing personalized design with the needs of public care environments.

Similar studies, including those by Hung, Chaudhury and Rust [29] and Tuszyńska-Bogucka, Kwiatkowski, Chmielewska, Dzieńkowski, Kocki, Pełka, Przesmycka, Bogucki and Galkowski [66], have highlighted the significance of environmental factors. However, Juliá Nehme, Torres Irribarra, Cumsille and Yoon [57] and Kim [56] argued that physical changes must be accompanied by social and cultural practices to foster emotional well-being. Simply changing the physical space without considering interpersonal interactions may have limited effects on emotional health. Additionally, Tuszyńska-Bogucka, Kwiatkowski, Chmielewska, Dzieńkowski, Kocki, Pełka, Przesmycka, Bogucki and Galkowski [66] used eye-tracking technology to study how interior design elements impact emotional health, finding that certain design features can elicit positive emotional responses that enhance well-being. This raises questions about whether emotional responses seen in experimental settings can be directly applied to real-life contexts. Furthermore, emotional experiences can vary widely depending on individual circumstances, making it challenging to generalize results from controlled experiments.

The complexity of emotional experiences poses challenges for designers and researchers (see Figure 10). Emotional experiences are shaped not only by the physical environment but also by social interactions and cultural contexts. Therefore, design strategies should consider the combined influence of these factors rather than focusing solely on physical changes. For example, Raanaas, Patil and Alve [30] found that incorporating natural elements in rehabilitation centers improved emotional experiences and increased patients’ sense of belonging. This suggests that combining natural elements with social interaction in design can effectively enhance emotional well-being.

Figure 10.

Network on the Emotional experience theme.

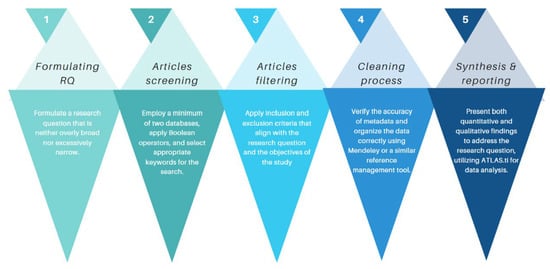

4. A Proposed Framework for Interior Design Strategies Aimed at Enhancing the Emotional Experience of Older Adults

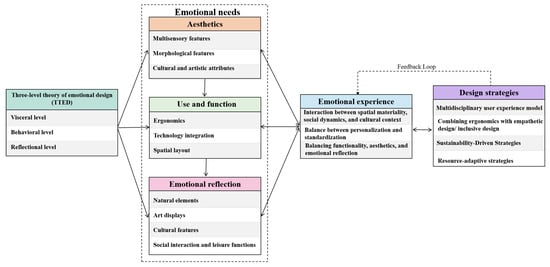

Based on a systematic literature review, recommendations for further research are proposed to deepen the understanding of this field. These recommendations are derived from an in-depth analysis of existing studies and are illustrated using the conceptual framework presented in Figure 11. Figure 11 summarizes 17 research directions aimed at enhancing the emotional experience of the elderly through interior design, providing practical guidance for designers and policymakers. Future studies can be clustered into:

Figure 11.

A proposed framework for interior design strategies aimed at enhancing the emotional experience of older adults.

Aesthetics: Future research should explore the role of multisensory experiences in interior design, focusing on the interaction of elements such as color, lighting, materials, sound, texture, and furniture, as well as the forms of geometric shapes, open architectural layouts, and natural and artificial features. Incorporating cultural and artistic decorative elements (e.g., regional culture and artistic styles) is essential for creating emotionally meaningful spaces. Further exploration of aesthetics will help enhance the overall emotional experience of the elderly.

Use and Function: The application of ergonomics is crucial to ensuring the safety and comfort of the elderly, covering spatial cognition, physical and environmental compatibility, and a multidimensional analysis of ergonomics. Optimizing spatial layout, including open and fluid circulation paths, is key to enhancing the elderly’s sense of security. Future research should also focus on integrating smart monitoring technologies and visual digital tools to maximize the functionality and convenience of interior spaces.

Emotional Reflection: Stimulating emotional reflection in the elderly through natural, artistic, and cultural elements is a promising area of research. Future studies should explore how natural elements (e.g., plants and window views), artwork (improving mental health through beautification), and cultural contexts (e.g., religion, feng shui, and traditional arts) promote identity and positive emotional memories for the elderly. Additionally, research should focus on enhancing opportunities for social interaction and recreation within spaces to cultivate a positive self-image among older individuals.

Design Strategies: Future design strategies should prioritize the development of multidisciplinary user experience models by integrating psychology, ergonomics, and architecture to create innovative solutions. They should also explore combining ergonomics with empathy and inclusive design principles to address the diverse needs of older adults, including those with cognitive and physical disabilities. Adaptive resource strategies should focus on improving the effectiveness of emotional experiences by aligning methods and technologies with available resources. Additionally, sustainability-driven strategies should advocate for the integration of renewable energy systems and sustainable materials, promoting designs that support emotional well-being and environmental stewardship.

Emotional Experience: Future research should systematically explore the interaction between the physical attributes of space, social interaction, and cultural background, with an emphasis on balancing functionality, aesthetics, and emotion. Balancing personalization and standardization is also key to enhancing design responsiveness. In residential environments for the elderly, integrating functional and emotional needs is a long-term goal for advancing emotional design.

To ensure the framework’s flexibility and adaptability, this study incorporated a dynamic feedback mechanism to effectively address potential discrepancies between expected outcomes and actual results. Functioning as a dynamic closed-loop process, this mechanism continuously evaluates and adjusts design strategies to fulfill the emotional and health needs of elderly users. Specifically, the feedback mechanism spans multiple modules of the framework, with its core functionalities, including (1) Validation of Emotional Experience, using users’ emotional responses as critical metrics for assessing strategy effectiveness, and prompting adjustments when needs are unmet; (2) Reapplication of Optimized Strategies, reintegrating improved strategies into practice with continuous testing to ensure applicability and effectiveness; (3) Dynamic Validation of Modules, continuously refining the impact of submodules such as ergonomics, cultural elements, and sensory features; and (4) Cross-Module Data Interaction, integrating feedback data across modules to guide overall process improvements. By leveraging this dynamic feedback mechanism, the framework achieves continuous optimization, maintaining adaptability and effectiveness across diverse scenarios and providing comprehensive support for the emotional and health needs of the elderly.

5. Conclusions

This study’s primary contribution is a thematic review of literature that emphasizes the critical role of interior design in addressing the emotional needs of the elderly. By synthesizing diverse design concepts, the research refines existing methodologies and proposes innovative approaches to emotional design, ultimately aiming to improve the quality of elderly living environments. The findings underscore the necessity of balancing emotional and psychological well-being with functional optimization in interior design, providing actionable insights for architects and interior designers.

A key outcome of this research was the development of a thematic framework based on the TTED model, which offers practical guidance for creating inclusive environments that support emotional health. This framework bridges theoretical exploration and practical application, equipping professionals with a structured approach to design solutions tailored to aging populations. Additionally, the study calls for the integration of emotional considerations into housing policies and regulatory frameworks to mitigate the negative psychological impacts often experienced by the elderly, thereby addressing a pressing societal challenge.

The analysis draws from 39 peer-reviewed articles sourced from Scopus and Web of Science, employing ATLAS.ti 9 for rigorous data extraction and thematic analysis. While achieving data saturation ensures comprehensive thematic coverage, the study acknowledges limitations such as potential interpretive biases and restricted database scope.

For practitioners, this research provides a robust evidence base to inform design decisions that enhance the emotional well-being of elderly users. For educators, it offers a valuable reference for integrating emotional design principles into architecture and interior design curricula, fostering a new generation of professionals attuned to the evolving needs of aging societies. Future research should expand the scope by incorporating authoritative databases, conducting field studies, and employing multimodal data collection methods and dynamic scenario simulations. Such efforts, particularly in cross-cultural contexts, will further validate and refine the proposed framework, ensuring its applicability across diverse settings.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.L.; methodology, L.L.; software, S.W.; validation, S.W.; formal analysis, L.L.; investigation, S.W.; resources, J.X.; writing—original draft preparation, L.L.; writing—review and editing, A.A. and N.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Gu, D.; Andreev, K.; Dupre, M.E. Major trends in population growth around the world. China CDC Wkly. 2021, 3, 604–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rudnicka, E.; Napierała, P.; Podfigurna, A.; Męczekalski, B.; Smolarczyk, R.; Grymowicz, M. The World Health Organization (WHO) approach to healthy ageing. Maturitas 2020, 139, 6–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paiva, M.M.B.; Villarouco, V. Acessibility in collective housing for the elderly: A case study in Portugal. Work 2012, 41, 4174–4179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mouratidis, K. Urban planning and quality of life: A review of pathways linking the built environment to subjective well-being. Cities 2021, 115, 103229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felix, E.; De Haan, H.; Vaandrager, L.; Koelen, M. Beyond thresholds: The everyday lived experience of the house by older people. J. Hous. Elder. 2015, 29, 329–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Hoof, J.; Marston, H.R.; Kazak, J.K.; Buffel, T. Ten questions concerning age-friendly cities and communities and the built environment. Build. Environ. 2021, 199, 107922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bigonnesse, C.; Chaudhury, H. Ageing in place processes in the neighbourhood environment: A proposed conceptual framework from a capability approach. Eur. J. Ageing 2021, 19, 63–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brasche, S.; Bischof, W. Daily time spent indoors in German homes–baseline data for the assessment of indoor exposure of German occupants. Int. J. Hyg. Environ. Health 2005, 208, 247–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oswald, F.; Wahl, H.-W. Housing and health in later life. Rev. Environ. Health 2004, 19, 223–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norman, D. Emotional Design: Why We Love (or Hate) Everyday Things; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Tonetto, L.M.; da Costa, F.C.X. Emotional Design: Concepts, approaches and research perspectives. Strateg. Des. Res. J. 2011, 4, 132–140. [Google Scholar]

- Yusa, I.M.M.; Ardhana, I.K.; Putra, I.N.D.; Pujaastawa, I.B.G. Emotional design: A review of theoretical foundations, methodologies, and applications. J. Aesthet. Des. Art Manag. 2023, 3, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tai, F.-C. Research on Urban and Rural Environment Design Concept in the Context of Emotional Care. In Proceedings of the 2020 3rd International Conference on e-Education, e-Business and Information Management (EEIM 2020), Taiyuan, China, 28–29 September 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Y.; Wu, S. Indoor Color and Space Humanized Design Based on Emotional Needs. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 926301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simons, J.; Irwin, D.; Drinnien, B. Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs. In Psychology—The Search for Understanding; West Publishing Company: New York, NY, USA, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Christenson, M.; Taira, E.D. Aging in the Designed Environment; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Jaglarz, A. Perception of color in architecture and urban space. Buildings 2023, 13, 2000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagheri, M.; Shahroudi, A. Effect of opening architectural shapes on users’ emotion with Kansei method. Intell. Build. Int. 2018, 10, 103–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loy, J.; Haskell, N. Future care: Rethinking technology enhanced aged care environments. J. Enabling Technol. 2018, 12, 91–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Wang, R.; Tang, C.; Luo, L.; Mo, X. Emotional design for smart product-service system: A case study on smart beds. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 298, 126823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, S.; Liu, M.; Chen, L.; Chen, Y.; Yao, L. Emotional Design and Evaluation of Children’s Furniture Based on AHP-TOPSIS. BioResources 2024, 19, 7418–7433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kongprasert, N.; Butdee, S. A methodology for leather goods design through the emotional design approach. J. Ind. Prod. Eng. 2017, 34, 170–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, H.; Liu, L.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, Y.; Wei, Y. Children’s Hospital Environment Design Based on AHP/QFD and Other Theoretical Models. Buildings 2024, 14, 1499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Han, C.; Yu, B.; Wei, K.; Li, Y.; Jin, S.; Bai, P. The Emotional Design of Street Furniture Based on Kano Modeling. Buildings 2024, 14, 3896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, C.; Mahmoud, N.S.A.; El Samanoudy, G.; Al Qassimi, N. Evaluating the color preferences for elderly depression in the United Arab Emirates. Buildings 2022, 12, 234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevens, K.; Fröis, T.; Masal, S.; Winder, A.; Bechtold, T. Design and colour preferences for older individuals in residential care. Res. J. Text. Appar. 2016, 20, 87–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosti, M.V.; Benayoun, M.; Georgakopoulou, N.; Diplaris, S.; Pistola, T.; Xefteris, V.-R.; Tsanousa, A.; Valsamidou, K.; Koulali, P.; Shekhawat, Y. Connecting the Elderly Using VR: A Novel Art-Driven Methodology. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 2217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, S. Emotion detection of elderly people in nursing homes based on AI robot vision. Soft Comput. 2023, 28, 13989–14002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hung, L.; Chaudhury, H.; Rust, T. The effect of dining room physical environmental renovations on person-centered care practice and residents’ dining experiences in long-term care facilities. J. Appl. Gerontol. 2016, 35, 1279–1301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raanaas, R.K.; Patil, G.; Alve, G. Patients’ recovery experiences of indoor plants and viewsof nature in a rehabilitation center. Work 2015, 53, 45–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zairul, M. The recent trends on prefabricated buildings with circular economy (CE) approach. Clean. Eng. Technol. 2021, 4, 100239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zairul, M.; Azli, M.; Azlan, A. Defying tradition or maintaining the status quo? Moving towards a new hybrid architecture studio education to support blended learning post-COVID-19. Archnet-IJAR Int. J. Archit. Res. 2023, 17, 554–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zairul, M. Opening the pandora’s box of issues in the Industrialised Building System (IBS) in Malaysia: A thematic review. J. Appl. Sci. Eng. 2021, 25, 297–310. [Google Scholar]

- Zairul, M. A thematic review on student-centred learning in the studio education. J. Crit. Rev. 2020, 7, 504–511. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Successful Qualitative Research: A Practical Guide for Beginners; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, V.K.; Singh, P.; Karmakar, M.; Leta, J.; Mayr, P. The journal coverage of Web of Science, Scopus and Dimensions: A comparative analysis. Scientometrics 2021, 126, 5113–5142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bucher, S. Bibliometric analysis of central European journals in the web of science and JCR social science edition. Malays. J. Libr. Inf. Sci. 2018, 23, 95–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zairul, M. Building a Sustainable Future: A Circular Economy–Based Leasing Model for Affordable Housing in Malaysia, Evaluated by Life Cycle Assessment. In Life Cycle Assessment & Circular Economy; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2023; pp. 69–85. [Google Scholar]

- Mirkia, H.; Nelson, M.S.; Abercrombie, H.C.; Thorleifsdottir, K.; Sangari, A.; Assadi, A. Recognition Memory for Interior Spaces with Biomorphic or Non–Biomorphic Interior Architectural Elements. J. Inter. Des. 2022, 47, 47–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brawley, E.C. Enriching lighting design. NeuroRehabilitation 2009, 25, 189–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bazley, C.; Vink, P.; Montgomery, J.; Hedge, A. Interior effects on comfort in healthcare waiting areas. Work 2016, 54, 791–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.; Bian, H.; Chang, C.K.; Dong, L.; Margrett, J. In-home monitoring technology for aging in place: Scoping review. Interact. J. Med. Res. 2022, 11, e39005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, D. Color-person-environment relationships. Color Res. Appl. 2008, 33, 312–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Şansal, K.E.; Şimşek, A.C.; Aktan, S.; Özbey, F.; Paksoy, A. Restorative Effects of Virtual Nature on the Emotional Well-being of Community-dwelling Older Adults. Eur. J. Geriatr. Gerontol. 2024, 6, 12–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, Y.; Li, P.; Hao, P. The Effects of Wooden Furniture Color, Floor Material, and Age on Design Evaluation, Visual Attention, and Emotions in Office Environments. Buildings 2024, 14, 1498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, C.; Gu, W.; Luo, X.; Kaner, J. Building a 4E interview-grounded theory model: A case study of demand factors for customized furniture. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0282956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timmermann, C.; Uhrenfeldt, L.; Birkelund, R. Cancer patients and positive sensory impressions in the hospital environment–a qualitative interview study. Eur. J. Cancer Care 2013, 22, 117–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manav, B. Color-emotion associations and color preferences: A case study for residences. Color Res. Appl. 2007, 32, 144–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huber, A.; Bailey, R. Designing Worthy Waiting Spaces: A Cross-Cultural Study of Waiting Room Features and Their Impact on Women’s Affective States. HERD Health Environ. Res. Des. J. 2024, 17, 112–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de paula Nunes Sobrinho, F.; de Lucena, U.F. Ergonomics and the inclusion of people with disabilities in a Brazilian workplace. Work 2012, 41, 4709–4715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forino, I. Living in “The Sense of the Past”: Solipsistic Impulses in the Domesticscapes of Edmond de Goncourt and Mario Praz. Interiors 2011, 2, 7–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khaleghimoghaddam, N.; Bala, H.A.; Özmen, G.; Öztürk, Ş. Neuroscience and architecture: What does the brain tell to an emotional experience of architecture via a functional MR study? Front. Archit. Res. 2022, 11, 877–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, C.M.; van der Heide, E.M.; van Rompay, T.J.; Ludden, G.D. Reimagine the ICU: Healthcare Professionals’ Perspectives on How Environments (Can) Promote Patient Well-Being. HERD Health Environ. Res. Des. J. 2024, 17, 97–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Şansal, K.E.; Balci, L.A.; Çinar, F.; Çoşkunsu, D.K.; Tanriöver, S.H.; Uluengin, M.B. Relationship of daily time spent outdoors with sleep quality and emotional well-being among community-dwelling older adults during COVID-19 restrictions. Turk. J. Geriatr. 2021, 24, 424–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juliá Nehme, B.; Rodríguez, E.; Yoon, S.Y. Spatial user experience: A multidisciplinary approach to assessing physical settings. J. Inter. Des. 2020, 45, 7–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, N. Theorizing emotional geographies of later-life care: Agamben, Marx, and Massey in the home. Soc. Sci. Humanit. Open 2023, 7, 100431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juliá Nehme, B.; Torres Irribarra, D.; Cumsille, P.; Yoon, S.Y. Waiting room physical environment and outpatient experience: The spatial user experience model as analytical tool. J. Inter. Des. 2021, 46, 27–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smit, D.; Willemse, B.; de Lange, J.; Pot, A.M. Wellbeing-enhancing occupation and organizational and environmental contributors in long-term dementia care facilities: An explorative study. Int. Psychogeriatr. 2014, 26, 69–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trevisani, F.; Casadio, R.; Romagnoli, F.; Zamagni, M.P.; Francesconi, C.; Tromellini, A.; Di Micoli, A.; Frigerio, M.; Farinelli, G.; Bernardi, M. Art in the hospital: Its impact on the feelings and emotional state of patients admitted to an internal medicine unit. J. Altern. Complement. Med. 2010, 16, 853–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, A.M.; Dawson, S.; Kristjanson, L.J. Exploring the relationship between personal control and the hospital environment. J. Clin. Nurs. 2008, 17, 1601–1609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sukkasi, S.; Tunnukit, P.; Lerspalungsanti, S. Developing Assistive Bedside Furniture for Early Postoperative Mobilization in a Healthcare Setting With an Attentive Empathetic Design Approach. HERD Health Environ. Res. Des. J. 2022, 15, 331–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherrod, C.; Johnson, D.; Chester, B. Safety, tolerability and effectiveness of an ergonomic intervention with chiropractic care for knowledge workers with upper-extremity musculoskeletal disorders: A prospective case series. Work 2014, 49, 641–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ram, V.; Schaposnik, L.P.; Konstantinou, N.; Volkan, E.; Papadatou-Pastou, M.; Manav, B.; Jonauskaite, D.; Mohr, C. Extrapolating continuous color emotions through deep learning. Phys. Rev. Res. 2020, 2, 033350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yildirim, K.; Akalin-Baskaya, A.; Hidayetoglu, M. Effects of indoor color on mood and cognitive performance. Build. Environ. 2007, 42, 3233–3240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engineer, A.; Sternberg, E.M.; Najafi, B. Designing interiors to mitigate physical and cognitive deficits related to aging and to promote longevity in older adults: A review. Gerontology 2018, 64, 612–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuszyńska-Bogucka, W.; Kwiatkowski, B.; Chmielewska, M.; Dzieńkowski, M.; Kocki, W.; Pełka, J.; Przesmycka, N.; Bogucki, J.; Galkowski, D. The effects of interior design on wellness–Eye tracking analysis in determining emotional experience of architectural space. A survey on a group of volunteers from the Lublin Region, Eastern Poland. Ann. Agric. Environ. Med. 2020, 27, 113–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, P. Exploring the influence of body movements on spatial perception in landscape and interior design. Mol. Cell. Biomech. 2024, 21, 434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.-Y.; Cho, J.Y.; Hong, Y.-K. Brain and Subjective Responses to Indoor Environments Related to Concentration and Creativity. Sensors 2024, 24, 7838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malenbaum, S.; Keefe, F.J.; Williams, A.C.d.C.; Ulrich, R.; Somers, T.J. Pain in its environmental context: Implications for designing environments to enhance pain control. Pain 2008, 134, 241–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaglarz, A. Color as a Key Factor in Creating Sustainable Living Spaces for Seniors. Sustainability 2024, 16, 10251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoxha, V.; Metin, H.; Hasani, I.; Pallaska, E.; Hoxha, J.; Hoxha, D. Gender differences of color preferences for interior spaces in the residential built environment in Prishtina, Kosovo. Facilities 2022, 41, 157–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaglarz, A.; Chrzanowski, S. The role of lighting in senior care facility design. Architectus 2023, 2, 87–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palumbo, L.; Rampone, G.; Bertamini, M.; Sinico, M.; Clarke, E.; Vartanian, O. Visual preference for abstract curvature and for interior spaces: Beyond undergraduate student samples. Psychol. Aesthet. Creat. Arts 2020, 16, 577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norberg-Schulz, C. Genius Loci: Towards a Phenomenology of Architecture; Rizzoli: New York, NY, USA, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Villarouco, V. Construindo uma Metodologia de Avaliação Ergonômica do Ambiente–AVEA. In Anais do 14º Congresso Brasileiro de Ergonomia; ABERGO: Porto Seguro, Brazil, 2008; Volume 13. [Google Scholar]

- Rogers, W.A.; Fisk, A.D. Toward a psychological science of advanced technology design for older adults. J. Gerontol. Ser. B Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 2010, 65, 645–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maltha, J. Philips Ambient Experience Solution at Children’s Medical Center Dallas Helps Calm Young Patients with Behavioral Health Issues. 2022. Available online: https://www.philips.com/a-w/about/news/media-library/20221011-philips-behavioral-health-experience-solution.html (accessed on 8 August 2024).

- Iyendo, T.O.; Uwajeh, P.C.; Ikenna, E.S. The therapeutic impacts of environmental design interventions on wellness in clinical settings: A narrative review. Complement. Ther. Clin. Pract. 2016, 24, 174–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, P.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, J.; Peng, K.; Pan, X.; Shen, Y.; Xiao, S.; Armstrong, E.; Er, Y.; Duan, L. Falls prevention interventions for community-dwelling older people living in mainland China: A narrative systematic review. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2020, 20, 808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sekowski, M. Attitude toward death from the perspective of Erik Erikson’s theory of psychosocial ego development: An unused potential. OMEGA-J. Death Dying 2022, 84, 935–957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Charras, K. Improving the Physical Environment of Care Homes. In Timely Psychosocial Interventions in Dementia Care: Evidence-Based Practice; Jessica Kingsley Publishers: London, UK, 2020; p. 220. [Google Scholar]

- Crocker, J.; Park, L.E. The costly pursuit of self-esteem. Psychol. Bull. 2004, 130, 392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Day, K.; Carreon, D.; Stump, C. The therapeutic design of environments for people with dementia: A review of the empirical research. Gerontologist 2000, 40, 397–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hurlbert, A.C.; Ling, Y. Biological components of sex differences in color preference. Curr. Biol. 2007, 17, R623–R625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coll-Planas, L.; Carbó-Cardeña, A.; Jansson, A.; Dostálová, V.; Bartova, A.; Rautiainen, L.; Kolster, A.; Masó-Aguado, M.; Briones-Buixassa, L.; Blancafort-Alias, S. Nature-based social interventions to address loneliness among vulnerable populations: A common study protocol for three related randomized controlled trials in Barcelona, Helsinki, and Prague within the RECETAS European project. BMC Public Health 2024, 24, 172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandita, D.; Choudhary, H. Biophilic designs: A solution for the psychological well-being and quality of life of older people. Work. Older People 2024, 28, 417–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).