Frank Gehry’s Self-Twisting Uninterrupted Line: Gesture-Drawings as Indexes

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. The Single Uninterrupted Line in Frank Gehry’s Sketches

2.1. Towards a Straightforward Relationship between Gesture and Decision Making

2.2. Gehry’s Drawings as Snapshots of a Progressive Concretisation of His Design Ideas

2.3. Gehry’s Drawings as ‘Intrinsic Image-Acts’: Understanding Architecture in an Image

2.4. Promoting a Kinaesthetic Relationship between Action and Thought

3. Frank Gehry Vis-à-Vis the Art Scene in Los Angeles in the 1960s, 1970s and 1980s

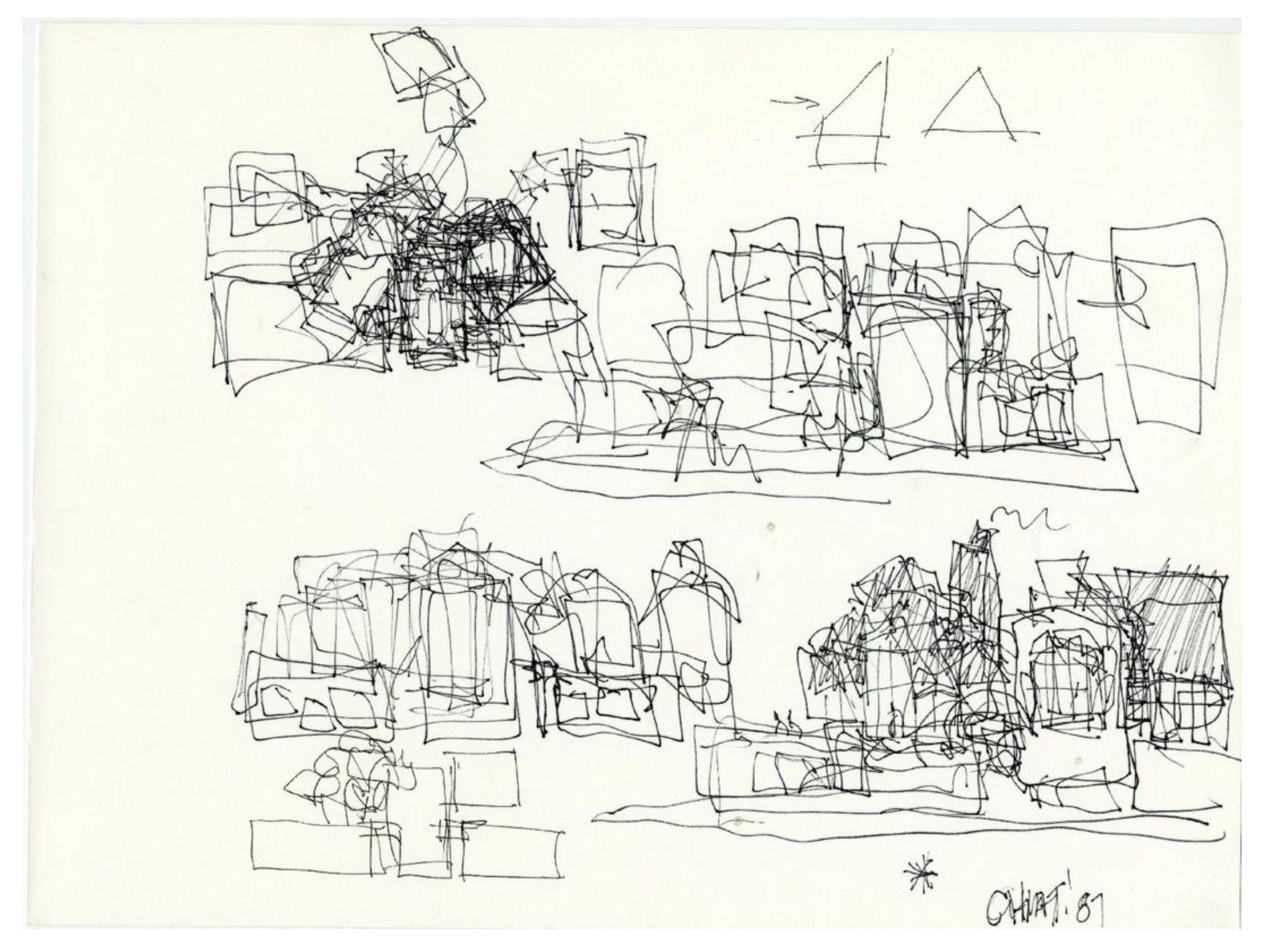

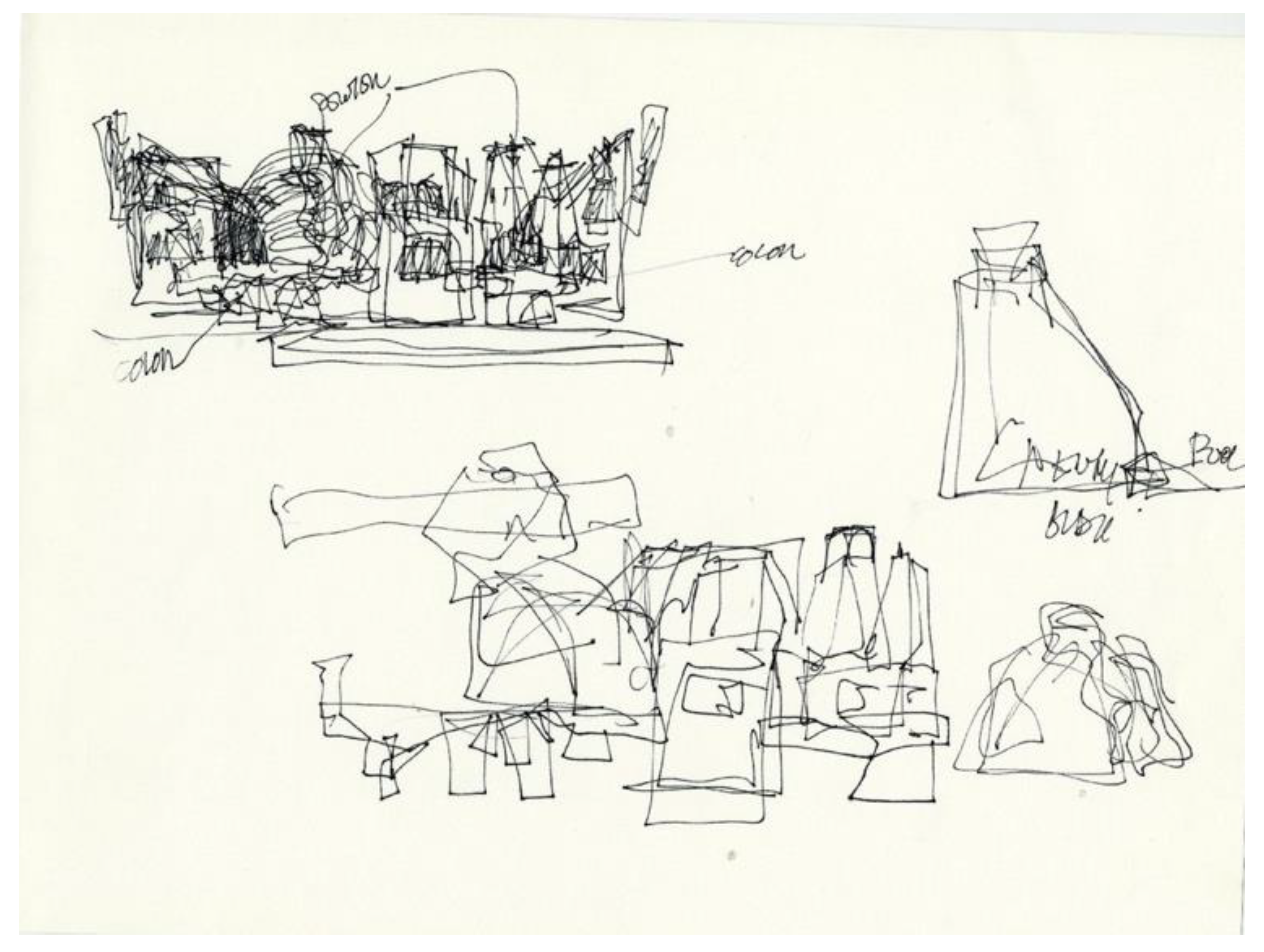

3.1. Juxtaposing the Different Drawings on the Same Sheet of Paper: Frank Gehry’s Sketches for Peter Lewis Residence, Jay Chiat Residence, and Winton Residence Guest House

3.2. Challenging the Dichotomy between Morphological and Functionalist Aspects

Solving all the functional problems is an intellectual exercise […] And I make a value out of solving all those problems. Dealing with the context and he client and finding my moment of truth after I understand the problem. If you look at our process […] you see models that show the pragmatic solution to the building without architecture. Then you see the study models that go through leading to the final scheme. We start with shapes, sculptural forma. Then we work into the technical stuff (Rappolt and Violette 2004, p. 52; Knight 2000)

4. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Agamben, Giorgio. 2006. Che cos’è un dispositivo? Milan: Notte Tempo. [Google Scholar]

- Alberti, Leon Battista. 1988. On the Art of Building in Ten Books. Translated by Joseph Rykwert, Neil Leach, and Robert William Tavernor. Cambridge: The MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Arnell, Peter, and Ted Bickford, eds. 1985. Frank Gehry, Buildings and Projects. New York: Rizzoli. [Google Scholar]

- Bechtler, Christina, ed. 1999. Frank Gehry-Kurt Forster [Art and Architecture in Discussion]. Ostfildern: Cantz. [Google Scholar]

- Benjamin, Walter. 1999. Rigorous Study of Art. In Selected Writings, 1927–34. Edited by Michael W. Jennings, Howard Eiland and Gary Smith. Translated by Thomas Y. Levin. Cambridge: Belknap Press, pp. 669–70. [Google Scholar]

- Bettley, Alison, David Mayle, and Tarek Tantoush, eds. 2005. Operations Management: A Strategic Approach. London: Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Bletter, Rosemarie Haag, Henry N. Cobb, Coosje van Bruggen, Mildred Friedman, Joseph Giovannini, Thomas S. Hines, Pilar Viladas, and Frank Gehry. 1986. The Architecture of Frank Gehry. New York: Rizzoli. [Google Scholar]

- Bredekamp, Horst. 2004. Frank Gehry and the Art of Drawing. In Gehry Draws. Edited by Mark Rappolt and Robert Violette. Cambridge: MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bredekamp, Horst. 2017. Image Acts: A Systematic Approach to Visual Agency. Boston and Berlin: De Gruyter. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, Bill. 2020. Re-Assemblage (Theory, Practice, Mode). Critical Inquiry 46: 259–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charitonidou, Marianna. 2020. Architecture’s Addressees: Drawing as Investigating Device. Villardjournal 2: 91–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cecchetti, Maurizio. 2011. For Sensitive Skin: On the Transformation of Architecture into Design. Annali d’Italianistica, Italian Critical Theory 29: 237–52. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, Jean-Louis. 2001. Frankly Urban: Gehry from Billboards to Bilbao. In Frank Gehry, Architect. Edited by J. Fiona Ragheb. New York: Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, pp. 322–36. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, Jean-Louis. 2020. Frank Gehry Catalogue Raisonné of the Drawings Volume One, 1954–78. Paris: Cahiers d’art/Staffan Ahrenberg. [Google Scholar]

- Connah, Roger. 2001. How Architecture Got Its Hump. Cambridge: The MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Dawkins, Roger. 2020. From the perspective of the object in semiotics: Deleuze and Peirce. Semiotica 233: 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deleuze, Gilles. 1983. Cinéma 1, L’image-Mouvement. Paris: Les éditions de Minuit. [Google Scholar]

- Deleuze, Gilles. 1985. Cinéma 2, L’image-Temps. Paris: Les éditions de Minuit. [Google Scholar]

- Deleuze, Gilles. 1986. Cinema I: The Movement-Image. Translated by Hugh Tomlinson, and Barbara Habberjam. London and New York: Bloomsburry Academic. [Google Scholar]

- Deleuze, Gilles. 1989a. Cinema II: The Time-Image. Translated by Hugh Tomlinson, and Robert Galeta. London and New York: Bloomsburry Academic. [Google Scholar]

- Deleuze, Gilles. 1989b. Qu’est-ce qu’un dispositif ? In Michel Foucault philosophe: Rencontre internationale Paris 9, 10, 1 Janvier 1988. Paris: Éditions du Seuil. [Google Scholar]

- Deleuze, Gilles. 1992. What is a Dispositif? In Michel Foucault, Philosopher. Edited by Timothy J. Armstrong. Hemel Hempstead: Harvester Wheatsheaf. [Google Scholar]

- Drohojowska-Philp, Hunter. 2011. Rebels in Paradise. The Los Angeles Art Scene and the 1960s. New York: Holt & Co. [Google Scholar]

- Dürer, Albrech. 1525. Underweysung Der Messung. Nuremburg: Hieronymus Andreas Formschneider. [Google Scholar]

- Edwards, Brian. 2008. Understanding Architecture through Drawing. New York: Taylor and Francis. [Google Scholar]

- Elkins, James. 2003. What Does Pierce’s Sign Theory Have to Say to Art History? Culture, Theory and Critique 44: 5–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emmons, Paul. 2019. Drawing Imagining Building: Embodiment in Architectural Design Practices. London and New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Fallon, Michael. 2014. Creating the Future: Art and Los Angeles in the 1970s. Berkeley: Counterpoint Press. [Google Scholar]

- Foster, Hal. 2002. Design and Crime: (and Other Diatribes. London and New York: Verso. [Google Scholar]

- Foucault, Michel. 1994. Dits et écrits. 1954–1988, vol. III: 1976–1979. Paris: Éditions Gallimard. [Google Scholar]

- Frascari, Marco. 2009. Lines as Architectural Thinking. Architectural Theory Review 14: 200–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frascari, Marco. 2011. Eleven Exercises in the Art of Architectural Drawing: Slow Food for the Architect’s Imagination. London and New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Friedman, Mildr. 2013. Frank Gehry: The Houses. New York: Rizzoli. [Google Scholar]

- Gänshirt, Christian. 2007. Tools for Ideas: Introduction to Architectural Design. Basel, Boston and Berlin: Birkhäuser. [Google Scholar]

- Goldberger, Paul. 2015. Building Art; the Life and Work of Frank Gehry. New York: Alfred A. [Google Scholar]

- Guattari, Felix, and Gilles Deleuze. 1980. Capitalisme et Schizophrénie II: Mille Plateaux. Paris: Les éditions de Minuit. [Google Scholar]

- Guattari, Felix, and Gilles Deleuze. 2004. Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia. Translation and Forward by Brian Massumi. London and New York: Continuum. [Google Scholar]

- Guattari, Felix, and Gilles Deleuze. 2007. A Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia. Translation and Forward by Brian Massumi. London and Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hackman, William. 2015. Out of Sight: The Los Angeles Art Scene of the Sixties. New York: Other Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hartoonian, Gevork. 2012. Architecture and Spectacle: A Critique. London: Ashgate. [Google Scholar]

- Isenberg, Barbara, ed. 2009. Conversations with Frank Gehry. New York: Knopf. [Google Scholar]

- Klee, Paul. 1953. Pedagogical Sketchbook. Translated by Sibyl Moholy-Nagy. New York: Frederick A. Praeger. [Google Scholar]

- Knight, Christopher. 2000. Full of Generosity. In Frank Gehry, Frank O. Gehry: The Architect’s Studio. Seattle: Henry Art Gallery. [Google Scholar]

- Krauss, Rosalind. 1977. Notes on the Index. October 3: 68–81. [Google Scholar]

- Leja, Michael. 2000. Peirce, Visuality, and Art. Representations 72: 97–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemonier, Aurélien, and Frédéric Migayrou, eds. 2015. Frank Gehry. Los Angeles: LACMA. [Google Scholar]

- Lindsey, Bruce. 2001. Digital Gehry: Material Resistance Digital Construction. Basel, Boston and Berlin: Birkhäuser. [Google Scholar]

- Lucas, Raymond. 2006. The Sketchbook as Collection: A Phenomenology of Sketching. In Recto Verso: Redefining the Sketchbook. Edited by Angela Bartram, Nader El-Bizri and Douglas Gittens. London and New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Lynn, Greg. 2017. Going Native: Notes on Selected Artifacts from Digital Architecture at the End of the Twentieth Century. In When Is the Digital in Architecture. Edited by Andrew Goodhouse. Berlin and Montreal: Sternberg Press/Canadian Centre for Architecture, pp. 279–334. [Google Scholar]

- Maclagan, David. 2014. Line Let Loose: Scribbling, Doodling and Automatic Drawing. London: Reaktion. [Google Scholar]

- Marshall, Alex. 2001. How to Make a Frank Gehry Building. New York Times, April 8, 64. [Google Scholar]

- McKenna, Kristine. 2009. The Ferus Gallery: A Place to Begin. Göttingen: Steidl. [Google Scholar]

- Mendini, Alessandro. 1980. Dear Frank Gehry. Domus 604: 1. [Google Scholar]

- Migayrou, Frédéric, ed. 2014. Frank Gehry. The Fondation Louis Vuitton. Orléans: Hyx. [Google Scholar]

- Morgenstern, Joseph. 1982. The Gehry Style. New York Times, May 16, 48. [Google Scholar]

- Morris, Sharon. 2013. Peirce: Re-Staging the Sign in the Work of Art. Recherches sémiotiques/Semiotic Inquiry 33: 177–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Orozco Esquivel, Jorge. 2017. Indexical Architecture: Prominent Positions, Applications and the Web. Ph.D. dissertation, ETH Zurich, Zurich, Switzerland. [Google Scholar]

- Peirce, Charles Sanders. 1958. Collected Writings (8 Vols.) (1931–58). Edited by Charles Hartshorne, Paul Weiss and Arthur W Burks. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ragheb, J. Fiona, ed. 2001. Frank Gehry, Architect. New York: Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum. [Google Scholar]

- Rappolt, Mark, and Robert Violette, eds. 2004. Gehry Draws. Cambridge: MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Rosand, David. 2013. Time Lines. In Moving Imagination: Explorations of Gesture and Inner Movement. Edited by Helena de Preester. Amsterdam and Philadelphia: John Benjamins Publishing Company. [Google Scholar]

- Sorkin, Michael. 1999. Frozen Light. In Gehry Talks: Architecture + Process. Edited by Mildred Friedman. New York: Rizzoli. [Google Scholar]

- Stierli, Martino. 2018. Montage and the Metropolis: Architecture and the Representation of Space. London and New Haven: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Szalapaj, Peter. 2014. Contemporary Architecture and the Digital Design Process. London and New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Tomkins, Calvin. 2005. Robert Rauschenberg’s New Life. The New Yorker, May 23, 76. [Google Scholar]

- Van Bruggen, Coosje. 1998. Frank O. Gehry: Guggenheim Museum Bilbao. New York: Guggenheim Museum Publications. [Google Scholar]

- ZaeraPolo, Alejandro. 2006. Frank. O. Gehry: Still Life. In Frank Gehry, 1987–2003. Edited by Fernando Márquez Cecilia and Richard C. Levene. Madrid: El Croquis. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Charitonidou, M. Frank Gehry’s Self-Twisting Uninterrupted Line: Gesture-Drawings as Indexes. Arts 2021, 10, 16. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts10010016

Charitonidou M. Frank Gehry’s Self-Twisting Uninterrupted Line: Gesture-Drawings as Indexes. Arts. 2021; 10(1):16. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts10010016

Chicago/Turabian StyleCharitonidou, Marianna. 2021. "Frank Gehry’s Self-Twisting Uninterrupted Line: Gesture-Drawings as Indexes" Arts 10, no. 1: 16. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts10010016

APA StyleCharitonidou, M. (2021). Frank Gehry’s Self-Twisting Uninterrupted Line: Gesture-Drawings as Indexes. Arts, 10(1), 16. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts10010016