The Meaning of the Snake in the Ancient Greek World

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Methodological Notes

3. Snakes and the Status Quo

3.1. A Topography of the Sacred

water symbolizes the whole of potentiality; it is fons et origo, the source of all possible existence. […] Principle of what is formless and potential, basis of every cosmic manifestation, container of all seeds, water symbolizes the primal substance from which all forms come and to which they will return either by their own regression or in a cataclysm.

3.2. The Aftermath

3.3. Destruction and Integration

when Apollo and Artemis had killed Python, they came to Aigialeia to obtain purification. Dread coming upon them at the place now named Fear, they turned aside to Karmanor in Krete, and the people of Aigialeia were smitten by a plague.(Paus. 2.7.7)

was that a sacred snake that my spear impaled when on the way from Sidon’s gates I planted in the earth those viper-teeth, those unheard-of seeds?’.(Ov. Met. 4.571–74)

4. A Snake on the Acropolis

They were anxious to get everything out safely because they wished to obey the oracle, and also not least because of this: the Athenians say that a great snake lives in the sacred precinct guarding the Acropolis. They say this and even put out monthly offerings for it as if it really existed. The monthly offering is a honey-cake. In all the time before this the honey-cake had been consumed, but this time it was untouched. When the priestess interpreted the significance of this, the Athenians were all the more eager to abandon the city since the goddess had deserted the Acropolis.(Hdt. 8.41.2–3)

5. Snakes on the Threshold

6. Snakes and Divine Healers

7. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ASL | Antikenmuseum und Sammlung Ludwig, Basel. |

| BAPD | Beazley Archive Pottery Database; avail online: http://www.beazley.ox.ac.uk/xdb/ASP/default.asp. |

| BM | The British Museum, London. |

| CdM | Cabinet des Medailles, Paris. |

| CUAM | Colorado University Art Museum, Boulder. |

| CVA | Corpus Vasorum Antiquorum. |

| DAM | Delos Archaeological Museum, Delos. |

| Getty | J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles. |

| KAM | Krannert Art Museum, Champaign-Urbana. |

| LIMC | Lexicon Iconographicum Mythologiae Classicae. |

| Louvre | Musée du Louvre, Paris. |

| MAN | Museo Archeologico Nazionale, Naples. |

| MCA | Museo Civico Archeologico, Bologna. |

| MFA | Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. |

| MFAR | Museum of Fine Arts, Richmond. |

| MGEV | Museo Gregoriano Etrusco Vaticano. |

| MMA | The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. |

| NAM | National Archaeological Museum, Athens. |

| SAM | Staatliche Antikensammlungen, Munich. |

| SHM | State Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg. |

| SMB | Antikensammlung, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin. |

| WAM | The Walters Art Museum, Baltimore. |

References

- Aston, Emma. 2011. Mixanthropoi. Animal-Human Hybrid Deities in Greek Religion. Liège: Presses Universitaires de Liège. [Google Scholar]

- Bettini, Maurizio. 2013. Women and Weasels. Mythologies of Birth in Ancient Greece and Rome. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Boardman, John. 1980. The Greeks Overseas. London: Thames and Hudson. [Google Scholar]

- Boardman, John. 1995. Greek Sculpture: The Late Classical Period and Sculpture in Colonies and Overseas. London: Thames and Hudson. [Google Scholar]

- Bodson, Liliane. 1978. ἱερὰ ζῷα. Contribution à l’étude de la place de l’animal dans la religion grecque ancienne. Brussels: Académie royal de Belgique. [Google Scholar]

- Bodson, Liliane. 1981. Les Grecs et leurs serpents. Premiers résultats de l’étude taxonomique des sources anciennes. L’Antiquité Classique 50: 63–67. [Google Scholar]

- Bonnechere, Pierre. 2003. Trophonios de Lébadée. Cultes et mythes d’une cité béotienne au miroir de la mentalité antique. Leiden: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Boyce, George. 1937. Corpus of the Lararia of Pompeii. Rome: American Academy in Rome. [Google Scholar]

- Brückner, Alfred. 1891. Zur Lekythos Tafel 4. Jahrbuch des Kaiserlich Deutschen Archäologischen Instituts 6: 197–200. [Google Scholar]

- Brulé, Pierre. 1987. La religión des filles à Athènes à l’èpoque classique. Mythes, cultes et société. Paris: Les Belles Lettres. [Google Scholar]

- Burkert, Walter. 1972. Homo necans. Interpretationen altgriechischer Opferriten und Mythen. Berlin: De Gruyter. [Google Scholar]

- Burkert, Walter. 1985. Greek Religion. Harvard: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Casanova Surroca, Eudaldo, Larumbe Gorraitz, and María Ángeles. 2005. La serpiente vencida. Sobre los orígenes de la misoginia en lo sobrenatural. Zaragoza: Prensas universitarias de Zaragoza. [Google Scholar]

- Conan, Michael. 2007. Sacred Gardens and Landscapes. Ritual and Agency. Washington, DC: Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection. [Google Scholar]

- Cusack, Carole M. 2011. The Sacred Tree: Ancient and Medieval Manifestations. Newcastle: Cambridge Scholars Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Davies, Malcom. 1987. The Ancient Greeks on Why Mankind Does Not Live Forever. Museum Helveticum: Revue Suisse pur l’étude de l’Antiquité Classique 44: 65–75. [Google Scholar]

- Detienne, Marcel. 1998. Apollon le couteau à la main: Une approche expérimentale du polythéisme grec. Paris: Gallimard. [Google Scholar]

- Deubner, Ludwig. 1932. Attische Feste. Berlin: H. Keller. [Google Scholar]

- Douglas, Mary. 1990. The Pangolin Revisited: A New Approach to Animal Symbolism. In Signifying Animals: Human Meaning in the Natural World. Edited by Roy Willis. London and New York: Routledge, pp. 25–36. [Google Scholar]

- Egli, Hans. 1982. Das Schlangensymbol. Geschichte, Märchen, Mythos. Düsseldorf: Patmos. [Google Scholar]

- Eliade, Mircea. 1958. Patterns in Comparative Religion. New York: Sheed and Ward. [Google Scholar]

- Elsner, Jas. 1995. Art and the Roman Viewer: The Transformation of Art from the Pagan World to Christianity. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Evans, Arthur. 1935. The Palace of Minos: A Comparative Account of the Successive Stages of the Early Cretan Civilization as Illustrated by the Discoveries at Knossos. London: Macmillan, vol. 4.1. [Google Scholar]

- Foss, Pedar. 1997. Watchful Lares: Roman Household Organization and the Rituals of Cooking and Eating. In Domestic Space in the Roman World: Pompeii and Beyond. Edited by Ray Laurence and Andrew Wallace-Hadrill. Portsmouth: JRA, pp. 197–218. [Google Scholar]

- Fröhlich, Thomas. 1991. Lararien- und Fassadenbilder in den Vesuvstädten. Untersuchungen zur ‚volkstümlichen, pompejanischen Malerei. Mainz: von Zabern. [Google Scholar]

- García Gual, Carlos. 1981. Mitos, Viajes, Héroes. Madrid: Taurus. [Google Scholar]

- Giacobello, Federica. 2008. Larari Pompeiani: Iconografia e culto dei Lari in Ámbito Domestico. Milan: LED. [Google Scholar]

- Gil, Luis. 2004. Therapeia. La medicina popular en el mundo clásico. San Sebastian: Triacastela. [Google Scholar]

- Gilhus, Ingvild Sælid. 2006. Animals, Gods and Humans: Changing Attitudes to Animals in Greek, Roman and Early Christian Thought. London and New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Golsin, Owen. 2010. Hesiod’s Typhonomachy and the Ordering of Sound. Transactions of the American Philological Association 140: 351–73. [Google Scholar]

- Gourmelen, Laurent. 2004. Kékrops, le roi-serpent. Imaginaire Athénien, Representations de l’humain et de l’animalité en Grèce ancienne. Paris: Les Belles Lettres. [Google Scholar]

- Grabow, Eva. 1998. Schlangenbilder in der Griechischen Schwarzfigurigen Vasenkunst. Paderborn: Scriptorium. [Google Scholar]

- Harden, Alastair. 2014. Animals in Classical Art. In The Oxford Handbook of Animals in Classical thought and Life. Edited by Gordon Lindsay Campbell. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 24–60. [Google Scholar]

- Harrison, Jane. 1899. Delphica. (A) The Erinys. (B) The Omphalos. Journal of Hellenic Studies 19: 205–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, Jane. 1903. Prolegomena to the Study of Greek Religion. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Haspels, Caroline Henriette Emilie. 1936. Attic Black-Figured Lekythoi. Paris: Boccard. [Google Scholar]

- Hauser, Friedrich. 1893. Eine Tyrrhenische Amphora der Sammlung Bourguignon. Jahrbuch des deutschen archäologischen Institut 8: 93–103. [Google Scholar]

- Hodder, Ian. 2012. Entangled. An Archaeology of the Relationships between Humans and Things. Malden: Wiley-Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmann, Herbert. 1997. Sotades, Symbols of Immortality on Greek Vases. Oxford: Clarendon Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hurwitt, Jeffrey. 1999. The Athenian Acropolis: History, Mythology, and Archaeology from the Neolithic Era to the Present. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Iles Johnston, Sarah. 1999. Restless Dead: Encounters between the Living and the Dead in Ancient Greece. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Immerwahr, Sara. 1971. The Athenian Agora XIII: The Neolithic and Bronze Ages. Princeton: The American School of Classical Studies at Athens. [Google Scholar]

- Jameson, Michael, David Jordan, and Roy Kotanksy. 1993. A Lex Sacra from Selinous. Durham: Duke University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Jannoray, Jean. 1940. Nouvelles inscriptions de Lébadée. Bulletin de Correspondance Hellénique 64: 36–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Junge, Michael. 1983. Untersuchungen zur Ikonographie der Erinys in der griechischen Kunst. Kiel: Christian-Albrechts-Universität zu Kiel. [Google Scholar]

- Keller, Otto. 1909. Die antike Tierwelt. Leipzig: Engelmann. [Google Scholar]

- Knappett, Carl. 2005. Thinking through Material Culture. An Interdisciplinary Perspective. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kurtz, Donna, and John Boardman. 1971. Greek Burial Customs. London: Thames and Hudson. [Google Scholar]

- Küster, Erich. 1913. Die Schlange in der griechischen Kunst und Religion. Gießen: Töpelmann. [Google Scholar]

- Lalonde, Gerald. 2006. Horos Dios. An Athenian Shrine and Cult of Zeus. Leiden: Boston: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Lambert, Wilfred G. 2013. Babylonian Creation Myths. Winona Lake: Eisenbrauns. [Google Scholar]

- Lang-Auinger, Claudia, and Elisabeth Trinkl, eds. 2015. ΦϒТА ΚAΙ ΖΩΙA: Pflanzen und Tiere auf griechischen Vasen. (Akten des internationalen Symposiums an der Universität Graz, 26.-28. September 2013). Corpus vasorum antiquorum, Österreich, suppl. 2. Vienna: Österreichischen Akademie der Wissenschaften. [Google Scholar]

- Lévi-Strauss, Claude. 1962. Le totémisme aujourd’hui. Paris: Presses Universitaires de France. [Google Scholar]

- LiDonnici, Lynn. 1995. The Epidaurian Miracle Inscriptions: Text, Translation and Commentary. Atlanta: Scholars Press. [Google Scholar]

- Loraux, Nicole. 1990. Gloire du même, prestige de l’autre. Variations grecques sur l’origine. Le genre humain (les langues mégalomanes) 21: 115–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loraux, Nicole. 1993. The Children of Athena. Athenian Ideas about Citizenship and the Division between the Sexes. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lupu, Eran. 2003. Sacrifice at the Amphiareion and a Fragmentary Sacred Law from Oropos. Hesperia 72: 321–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mähly, Jacob. 1867. Die Schlange im Mythus und Cultus der classischen Völker. Basel: Schultze. [Google Scholar]

- Mason, Jim. 2007. Animals: From Souls and the Sacred in Prehistoric Times to Symbols and Salves in Antiquity. In A Cultural History of Animals in Antiquity. Edited by Linda Kalof. Oxford: Berg, pp. 17–46. [Google Scholar]

- Mitropoulou, Elpis. 1977. Deities and Heroes in the Form of Snakes. Athens: Pyli Editions. [Google Scholar]

- Mommsen, August. 1898. Feste der Stadt Athen im Altertum Geordnet nach Attischem Kalender. Leipzig: B. G. Teubner. [Google Scholar]

- Mundkur, Balaji. 1983. The Cult of the Serpent: An Interdisciplinary Survey of its Manifestations and Origins. Albany: State University of New York Press. [Google Scholar]

- Nilsson, Martin P. 1950. The Minoan-Mycenaean Religion and Its Survival in Greek Religion. Lund: Biblo and Tannen. [Google Scholar]

- Oberhelman, Steven M., ed. 2013. Dreams, Healing, and Medicine in Greece: From Antiquity to the Present. Farnham: Burlington: Ashgate. [Google Scholar]

- Ogden, Daniel. 2013. Drakōn: Dragon Myth and Serpent Cult in the Greek and Roman Worlds. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Orr, David. 1978. Roman Domestic Religion: A Study of the Roman Household Deities and their Shrines at Pompeii and Herculaneum. In Aufstieg and Niedergang der römischen Welt II.16.2. New York: De Gruyter. [Google Scholar]

- Parke, Herbert William. 1977. Festivals of the Athenians. London: Thames and Hudson. [Google Scholar]

- Parker, Robert. 1996. Athenian Religion: A History. Oxford: Clarendon Press. [Google Scholar]

- Parker, Robert. 2011. On Greek Religion. Ithaca: Cornell University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Pearson, Alfred Chilton, ed. 1917. The Fragments of Sophocles, 2. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Peifer, Egon. 1989. Eidola und andere mit dem Sterben verbundene Flügelwesen in der attischen Vasenmalerei in spätarchaischer und klassischer Zeit. Frankfurt am Main: Lang. [Google Scholar]

- Pieraccini, Lisa. 2016. Sacred Serpent Symbols: The Bearded Snakes of Etruria. Journal of Ancient Egyptian Interconnections 10: 92–102. [Google Scholar]

- Platt, Verity J. 2011. Facing the Gods: Epiphany and Representation in Graeco-Roman Art, Literature and Religion. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Pollitt, Jerome. 1972. Art and Experience in Classical Greece. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Propp, Vladimir. 1974. Las raíces históricas del cuento. Madrid: Fundamentos. [Google Scholar]

- Radermacher, Ludwig. 1903. Das Jenseits im Mythos der Hellenen: Untersuchungen über antiken Jenseitsglauben. Bonn: A. Marcus und E. Weber. [Google Scholar]

- Riaño, Daniel. 1999. Δράκων. Τῆς φιλίας τάδε δῶρα. Miscelánea léxica en memoria de Conchita Serrano, Manuales y anejos de Emerita 41: 171–186. [Google Scholar]

- Riethmüller, Jürgen. 2005. Asklepios: Heiligtümer und Kulte, 2 vols. Heidelberg: Verlag Archäologie und Geschichte. [Google Scholar]

- Ritvo, Harriet. 2007. On the Animal Turn. Daedalus 136: 118–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez Pérez, Diana. 2008. Serpientes, dioses y heroes: El combate contra el monstruo en el arte y la literatura griega antigua. León: Universidad de León. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez Pérez, Diana. 2010a. The Snake in the Ancient Greek World: Myth, Rite, and Image. Ph.D. dissertation, Universidad de León, León. unpublished. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez Pérez, Diana. 2010b. ‘He took the Behaviour of the Snake as a Sign from the Heaven’: An Approach to Athenian Religion. Thetis. Mannheimer Beiträge zur Klassischen Archäologie und Geschichte Griechenlands und Zyperns 16/17: 29–39. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez Pérez, Diana. 2011. Mujeres, esclavos y niños en el culto de Zeus Miliquio: Análisis iconográfico de los relieves votivos. In Iconografía y sociedad en el mediterráneo antiguo. Homenaje a la Profesora Pilar González Serrano. Edited by Pilar Fernández Uriel and Isabel Rodríguez López. Madrid: Signifer. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez Pérez, Diana. 2013. Encounters at the Tomb: Visualizing the Invisible in Attic Vase Painting. In Daimonic Imagination: Uncanny Intelligence. Edited by Angela Voss and William Rowlandson. Cambridge: Cambridge Publishing Scholars, pp. 23–43. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez Pérez, Diana. 2015. Guardian Snakes and Combat Myths: An Iconographical Approach. In ΦϒТА ΚAΙ ΖΩΙA: Pflanzen und Tiere auf griechischen Vasen. Akten des Internationalen Symposiums an der Universität Graz, 26.-28. September 2013. Edited by Claudia Lang-Auinger and Elisabeth Trinkl. Vienna: Österreichische Akademie der Wissenschaften, pp. 147–54. [Google Scholar]

- Salapata, Gina. 2006. The tippling serpent in the art of Laconia and beyond. Hesperia 75: 541–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sancassano, Maria Lucia. 1996. Il lessico greco del serpente. Athenaeum 84: 49–70. [Google Scholar]

- Sancassano, Maria Lucia. 1997a. Il serpente e le sui immagini. Il motivo del serpente nel poesia greca dall’Iliade all’Orestea. Bibliotheca di Athenaeum 36. [Google Scholar]

- Sancassano, Maria Lucia. 1997b. Il misterio del serpente: Retrospettiva di studi e interpretazioni moderne. Athenaeum 85: 355–90. [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro, Harvey Alan. 1993. Personifications in Greek Art: The Representation of Abstract Concepts, 600–400 B.C. Zürich: Akanthus. [Google Scholar]

- Shepard, Paul. 1978. Thinking Animals: Animals and the Development of Human Intelligence. New York: Viking Press. [Google Scholar]

- Simon, Erika. 1983. Festivals of Attica. An Archaeological Commentary. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sineux, Pierre. 2007. Amphiaraos: Guerrier, devin et guérisseur. Paris: Les Belles Lettres. [Google Scholar]

- Taylour, William. 1971. The House with the Idols: Mycenae, and its Chronological Implications. American Journal of Archaeology 75: 266–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Todorov, Tzvetan. 1975. The Fantastic: A Structural Approach to a Literary Genre. Ithaca: Cornell University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Trumpf, Jürgen. 1958. Stadtgründung und Drachenkampf (Excurse zu Pindar, Pythien I). Hermes 86: 129–57. [Google Scholar]

- Tsingarida, Athena. 2009a. À la santé des dieux et des hommes. La phiale: Un base à boire au banquet athénien? Mètis 7: 91–109. [Google Scholar]

- Tsingarida, Athena. 2009b. Vases for Heroes and Gods: Early Red-figure Parade Cups and Large-scaled Phialai. In Shapes and Uses of Greek Vases (7th-4th Centuries B.C.). Edited by Athena Tsingarida. Brussels: Centre de Recherches en Archéologie et Patrimoine (CReA-Patrimoine), pp. 185–201. [Google Scholar]

- Turner, Victor W. 1979. Process, Performance, and Pilgrimage: A Study in Comparative Symbology. New Delhi: Concept. [Google Scholar]

- Van Gennep, Arnold. 1909. Les Rites de Passage. Paris: É. Nourry. [Google Scholar]

- Vázquez Hoys, Ana María, and Oscar Muñoz Martín. 1997. Diccionario de magia en el mundo antiguo. Madrid: Alderabán. [Google Scholar]

- Vian, Francis. 1963. Les origines de Thèbes: Cadmos et les Spartes. Paris: Klincksieck. [Google Scholar]

- von Ehrenheim, Hedvig. 2015. Greek Incubation Rituals in Classical and Hellenistic Times. Kernos suppl., 29. Liège: Presses Universitaires de Liège. [Google Scholar]

- Wakeman, Mary. 1973. God’s Battle with the Monster. Leiden: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Whittaker, Helne. 1997. Mycenaean Cult Buildings: A Study of Their Architecture and Function in the Context of the Aegean and the Eastern Mediterranean. Bergen: Norwegian Institute at Athens. [Google Scholar]

- Wide, Sam. 1901. Mykenische Götterbilder und Idole. Athenische Mitteilungen 26: 247–57. [Google Scholar]

- Willis, Roy. 1994. The Meaning of the Snake. In Signifying Animals: Human Meaning in the Natural World. Edited by Roy Willis. London and New York: Routledge, pp. 233–39. [Google Scholar]

| 1 | The concept of ‘affordances’ was latent in my doctoral work, but I failed to formulate it in those terms. I thank the ARTS reviewer who brought Bettini’s work to my attention. In material culture studies, the concept of affordances has also exerted influence in the notion that the properties of materials or things afford certain outcomes (e.g., Knappett 2005). It has recently been picked up by Ian Hodder in his work on entanglement (Hodder 2012, pp. 48–49). |

| 2 | Despite the abundance of mentions to snakes in modern scholarship, there are not many works exclusively devoted to this animal in the ancient Greek world. The first one was Mähly’s Die Schlange im Mythos und Cultus der classischen Völker in 1867 (Mähly 1867), followed by Küster’s 1913 Die Schlange in der griechischen Kunst und Religion (Küster 1913). With a more limited scope but equally comprehensive come Mitropolou’s Deities and Heroes in the Form of Snake (1977) and Grabow’s investigation of the depiction of snakes in Greek black-figure pottery (Grabow 1998). On the linguistic side, Sancassano’s contributions on the names of the snakes in ancient Greek (Sancassano 1996, 1997a, 1997b) must be noted as well as Liliane Bodson’s studies on ancient snake taxonomy (Bodson 1981) (and also her 1978 on animals in ancient Greek religion, Bodson 1978). Odgen’s Drakon book, published in 2013 claiming to be ‘the first survey in any language of the Graeco-Roman reflex of the dragon or the supernatural serpent’ investigates accounts of many dragons of myth and also the association of snakes in the cultic realm. Although not specifically focused in the ancient Greek world, Degli‘s Das Schlangensybmol. Geschichte, Märchen, Mythos is also worth mentioning. On particular snakes´ fields of action, see, for example, Fontenrose‘s Python book, on the Delphic myth and other fights against dragons and similar monsters, Trumpf’s study on foundational dragon myths (Trumpf 1958), Salapata’s contribution on ‘tippling snakes’ in the art of Lakonia and beyond (Salapata 2006), or Casanova and Larumbe’s persuasive gender reading of western snake symbolism in La serpiente vencida, in 2005 (Casanova Surroca et al. 2005). There are also a number of studies on deities linked to snakes, such as Trophonios, Asklepios, Meilichios, and Amphiaraos (Bonnechere 2003; Riethmüller 2005; Lalonde 2006; Sineux 2007), or Kekrops (Gourmelen 2004). Finally, I may also note my contributions to the subject, mainly my 2010 PhD The Snake in the Ancient World: Myth, Rite, and Image, and the early book on combat myths Serpientes, dioses y heroes. El combate contra el monstruo en el arte y la literatura griega antiguas (Rodríguez Pérez 2008), as well as several other related publications (Rodríguez Pérez 2010b, 2011, 2013, 2015). |

| 3 | On animals and plants in Greek vase painting, see Lang-Auinger and Trinkl (2015). |

| 4 | In the sense mentioned above (l. 128–129) of ‘a particular snake whose story is told in a particular myth, cult, or ritual, or whose function can be inferred from its role in that myth, cult, or ritual’. |

| 5 | For a lengthier treatment, see Rodríguez Pérez (2010a). |

| 6 | |

| 7 | Hom. Il. 2.780–84; Hes. Theog. 836–68; Pind. Pyth. 1.29; Aes. Prom. 351; SAM inv. no. 596 (Chalcidian black-figure hydria; BAPD no. 1004764; LIMC #2619); Küster (1913, pp. 87–89); Rodríguez Pérez (2008, pp. 23–48); Ogden (2013, pp. 69–79). |

| 8 | Ap. Rhod. Argon. 4.1390–421; Apollod. Bibl. 2.5.11; SMB inv. no. 3261 (Athenian black-figure lekythos; BAPD no. 330543; LIMC #21989); KAM inv. no. 70.8.4 (Athenian red-figure hydria; BAPD no. 5159; LIMC #20839); BM reg. no. 1875,0309.25 (Athenian red-figure hydria; BAPD no. 230491; LIMC #23383); MMA obj. no. 24.97.5 (Athenian red-figure hydria; BAPD no. 9525; LIMC #16820); Küster (1913, p. 93); Rodríguez Pérez (2008, pp. 131–32), 146, figs. 64, 65, 80; ead. (2015), p. 149, Figure 3; Ogden (2013, pp. 33–39). |

| 9 | Ap. Rhod. Argon. 4.87–88; Hyg. Fab. 22; Ov. Met. 7.35; Prop. 3.11.9–11; Sen. Med. 466; MMA obj. no. 34.11.7 (Athenian red-figure column-krater; BAPD no. 205910; LIMC #24466); MCA inv. no. 190 (Athenian red-figure column-krater; BAPD no. 205909; LIMC #36703); MGEV inv. no. 16545 (Athenian red-figure cup; BAPD no. 205162; LIMC #24439); SAM inv. no. 3268 (Apulian red-figure volute-krater; BAPD no. 9036838); SHM inv. no. 1718 (Apulian red-figure volute-krater); MAN inv. no. 82.126 (Paestan red-figure volute-krater); Rodríguez Pérez (2008, pp. 162, 177, figs. 84–85, 103); Ogden (2013). |

| 10 | Ov. Met. 3.26–49; Hyg. Fab. 178; Apollod. Bibl. 3.4; Paus. 9.5, 9.10, 9.12; Louvre inv. no. N3325 (M12) (Athenian red-figure hydria; BAPD no. 10851; LIMC #9885); MMA obj. no. 22.139.11 (Athenian red-figure bell-krater; BAPD no. 214545; LIMC #9883); Shapiro (1993, pp. 99–102, Figures 51–54); Rodríguez Pérez (2008, pp. 188–90, figs. 107–11); Ogden (2013, pp. 58–62). |

| 11 | Eur. Iph. Taur. 1234–57; Ap. Rhod. Argon. 2.705–7; Ov. Met. 1.434–47; Luc. 5.79–81; Stat. Theb. 6.8; Hyg. Fab. 140; CdM inv. no. 306 (Athenian black-figure lekythos; BAPD no. 330984; LIMC #13587); SMB inv. no. F2212 (Athenian red-figure lekythos; BAPD no. 208984; LIMC #16858); Grabow 1998, pl.18 (K84); Rodríguez Pérez (2008), p. 90, Figure 23; Ogden (2013, pp. 40–48). |

| 12 | Eur. Iph. Taur. 1234–57; Stat. Theb. 6.8. |

| 13 | LIMC Apollon 1001 a–c. |

| 14 | CdM inv. no. 306 (Athenian black-figure lekythos; BAPD no. 330984; LIMC #13587). |

| 15 | Hes. Theog. 216, 274, 334; Ov. Met. 4.627; Varro, Rust. 2.1; Diod. Sic. 4.26–27; Luc. 9.363; Hyg. Fab. 30.12. Atlas also features in scenes of the Garden of the Hesperides in vase painting and relief sculpture: e.g., Getty inv. no. 77.AE.11 (Athenian red-figure volute-krater; BAPD no. 201704); London, Market (Athenian red-figure bell-krater; BAPD 9035686); MAN inv. no. 81934 (Apulian red-figure volute-krater); Louvre inv. no. 716 and Olympia Museum inv. no. 79 (metope with Herakles holding up the sky, Athena, and Atlas with the apples. From the Temple of Zeus in Olympia). |

| 16 | Eur. Hipp. 746–750. |

| 17 | Hes. Theog. 213–216; Ap. Rhod. Argon. 2.1427–1428; Apollod. Bibl. 2.5,11. |

| 18 | Nonn. Dion. 1.389. |

| 19 | Apulian red-figure volute-krater (MAN inv. no. 81934). |

| 20 | The motif of the ‘swallowing snake’ is, according to Propp (1974, pp. 329–57), the oldest form of snake in traditional tales. The motif stands for the complete initiation of the hero, whose travel to the inside of the monster symbolises his stay in the underworld. It is one of the most visually compelling instances of the liminal phase of the initiation ritual. |

| 21 | Boardman (1980, p. 151) argued that the bearded snake entered Greek iconography via Egypt, where there were numerous images of bearded snakes, including some thirty snake gods. |

| 22 | Schol. Eur. Or. 479; Schol. Aischyl. Sept. 291.a; Schol. Aischyl. Sept. 381.c. |

| 23 | Ogden (2013, pp. 2–5), for his part, loosely employs ‘drakōn’ as synonym with ophis and serpens, and ultimately does not distinguish ‘snake’, ‘serpent’ or ‘dragon’. |

| 24 | A biological trait of snakes is undoubtedly behind this consideration: their lidless, unblinking eyes, which are protected only by a transparent scale. Either awake or asleep the eyes of the serpents always remain the same, as if in an eternal wakefulness. |

| 25 | |

| 26 | Pieraccini (2016) briefly reviewed the role of bearded snakes in Etruria and thinks that the beard signifies special underworld powers in that context, especially when in the hands of winged figures or guardians of the Underworld, whereas in ancient Greece the breaded snake would function predominantly in the world of myth, especially representing “monsters that are slain by a hero” (p. 94). While this is broadly true, there are many instances of bearded snakes in Etruscan context outside the realm of death. Likewise, bearded snakes appear in many other situations in Greek visual culture outside the realm of the combat myth, including in funerary contexts, in association with eagles, on fountain houses, or in connection with healing and chthonian deities. Probably, what joins all of these snakes is their fantastic nature and guardian role, and I believe this is where we should look at to fully understand the image of the bearded snake. |

| 27 | On the role of monsters, and in particular, of mixed creatures, as standing in for an older order, see (Aston 2011, pp. 339–44). |

| 28 | SHM inv. no. Gr-4488 (Athenian red-figure stamnos; BAPD no. 207407; LIMC#20120); Rodríguez Pérez (2008, p. 147, figs. 81–82). |

| 29 | For Jason as the paradigm of a hero who lost his happy ending, see García Gual (1981). |

| 30 | MMA acc. no. 07.286.66 (Athenian red-figure calyx-krater; BAPD no. 207136; LIMC#9882); supra n. 10. |

| 31 | NAM inv. no. 1281 (Athenian red-figure lekythos, BAPD no. 2569); MMA acc. no. 1922.139.11 (Athenian red-figure bell-krater, BAPD no. 214545); Louvre inv. no. M12 (Athenian red-figure hydria, BAPD no. 10851). |

| 32 | Pind. Pyth. 1.28–29; Aesch. Prom. 351; Ov. Ep. 15.11, Fast. 4.491. |

| 33 | Eur. Phoen. 818; Sen. Oed. 739; Ov. Met. 26–138. |

| 34 | Hyg. Poet. astr. 2.3; Arat. Phaen. 45. Ladon is depicted in this manner on a Graeco-Persian chalcedony intaglio, ca. 425–400 bce, today in the Cabinet des Medailles, Paris (inv. no. 58.1903). |

| 35 | In the Babylonian creation myth, Marduk sliced Tiamat in two, thus creating heaven and earth, the monster’s weeping eyes producing the streams of the Euphrates and the Tigris, its tail becoming the Milky Way; Enuma Elish 4.136–40 (ed. Lambert 2013). |

| 36 | For Ladon, e.g., see Hes. Theog. 333; Ap. Rhod. Argon. 4.1394–98; Hyg. Poet. Astr. 2.6. For Python, e.g., see: Ov. Met. 1.434–51; Hyg. Fab. 140. For Typhon, e.g., see: Hes. Theog. 820–22; Aesch. Prom. 353; Ap. Rhod. Argon. 2.1209–12; Apollod. Bibl. 1.39. |

| 37 | |

| 38 | DAM inv. no. 189. |

| 39 | After the Gigantomachy, ‘Themis displayed to dumbfounded Earth, mother of the Giants, the spoils of the Giant destroyed, an awful warning for the future, and hung them up high in the vestibule of Olympus’ (Nonn. Dion. 710). Typhon, in turn, was buried inside his mother, under Mount Etna, making periodical appearances in the form of volcanic eruptions (Pind. Pyth. 1, 15; Aesch. Prom. 350). |

| 40 | I thank Vasso Zachari for checking this reference for me. |

| 41 | In Eur. Bacch. 1330–31 this transformation was the punishment of Dionysos. |

| 42 | |

| 43 | For the role of the snake in the Erichthonios myth as well as other Greek infant heroes, see (Rodríguez Pérez 2010a, pp. 293–313); cf. Küster (1913, pp. 98–100). |

| 44 | |

| 45 | On the Athenian discourse of autochthony, see, e.g., Loraux (1990, 1993), Brulé (1987), and Gourmelen (2004). In addition, Aston (2011, pp. 91–132). On the Athenian sacred snake, see lengthier treatment in Rodríguez 2010b. |

| 46 | Palermo, Mormino Collection inv. no. 769; BAPD no 270; LIMC#19723. |

| 47 | E.g., SAM inv. no. J345 (Athenian red-figure stamnos; BAPD no. 205571); Louvre inv. no. CA 681 (Athenian red-figure lekythos; BAPD no. 265); SMB inv. no. F5237 (Athenian red-figure cup; BAPD no. 217211); MFAR inv. no. 81.70 (Athenian red-figure calyx-krater; BAPD no. 10158). |

| 48 | Apollod. Bibl. 3.14.6. |

| 49 | On this festival, see Mommsen (1898); Harrison (1903, p. 131); Deubner (1932, pp. 9–7); Parke (1977); Burkert (1972, p. 171); Simon (1983, pp. 39–46). |

| 50 | Frankfurt, Liebieghaus inv. no. STV7, BAPD no. 204131. |

| 51 | ASL inv. no. BS404, BAPD no. 376. |

| 52 | Louvre inv. no. MA 847. |

| 53 | Nevertheless, as Hurwitt (1999, p. 70) rightly emphasises: ‘despite their extensive propaganda of autochthony, historical Athenians were not indigenous or aboriginal after all: they simply forgot (or repressed the memory of) their ancient arrival’. |

| 54 | The supporting evidence for this is, admittedly, scarce and problematic: the study of the Minoan Snake Goddess has been heavily influenced by Arthur Evans’ emphasis on the domestic cult practiced in houses and palaces, and there is much confusion about the identity of the images of the Minoan goddess; it is also not clear to what extent the Mistress of Animals-type goddess can be considered a precursor to Athena, and the differences in religious practices and beliefs of Minoan Crete and Mycenaean Greece have been emphasised to the detriment of the unity vision of the past; cf. Küster (1913, pp. 28–34); Nilsson (1950); Whittaker (1997). |

| 55 | The most famous and iconic representations of snakes around house altars and hearths are those from the lararia and altars in Pompeii and Herculaneum, which have received a great deal of attention by scholars since the early 20th century AD. Cf. Boyce (1937); Orr (1978); Fröhlich (1991); Foss (1997); Giacobello (2008). |

| 56 | Evans (1935, p. 140) mentioned a number of objects from a private house at Knossos as evidence for such a cult. The material includes what he called ‘snake vessels’, a ‘snake table’, and a ‘portable hearth’. |

| 57 | Harrison (1899, p. 221) suggested that Athena anthropomorphised oikouros ophis (guardian serpent) and moira (fate) of her city. |

| 58 | |

| 59 | For examples of snakes as decorative elements of fountain houses in Athenian vase painting, see BM reg. no. 1836,0224.169 (Athenian black-figure hydria; BAPD no. 320163); Rijksmuseum van Oudheden, Leiden, inv. no. PC 63 (Attic black-figure hydria; BAPD no. 320011); Agora Museum, Athens, inv. no. P2642 (BAPD no. 31131); Archaeological Museum, Florence, inv. no. 94754 (BAPD no. 8099); MGEV inv. no. 417 (BAPD no. 302871); SMB inv. no. F 4027 (BAPD no. 206280). |

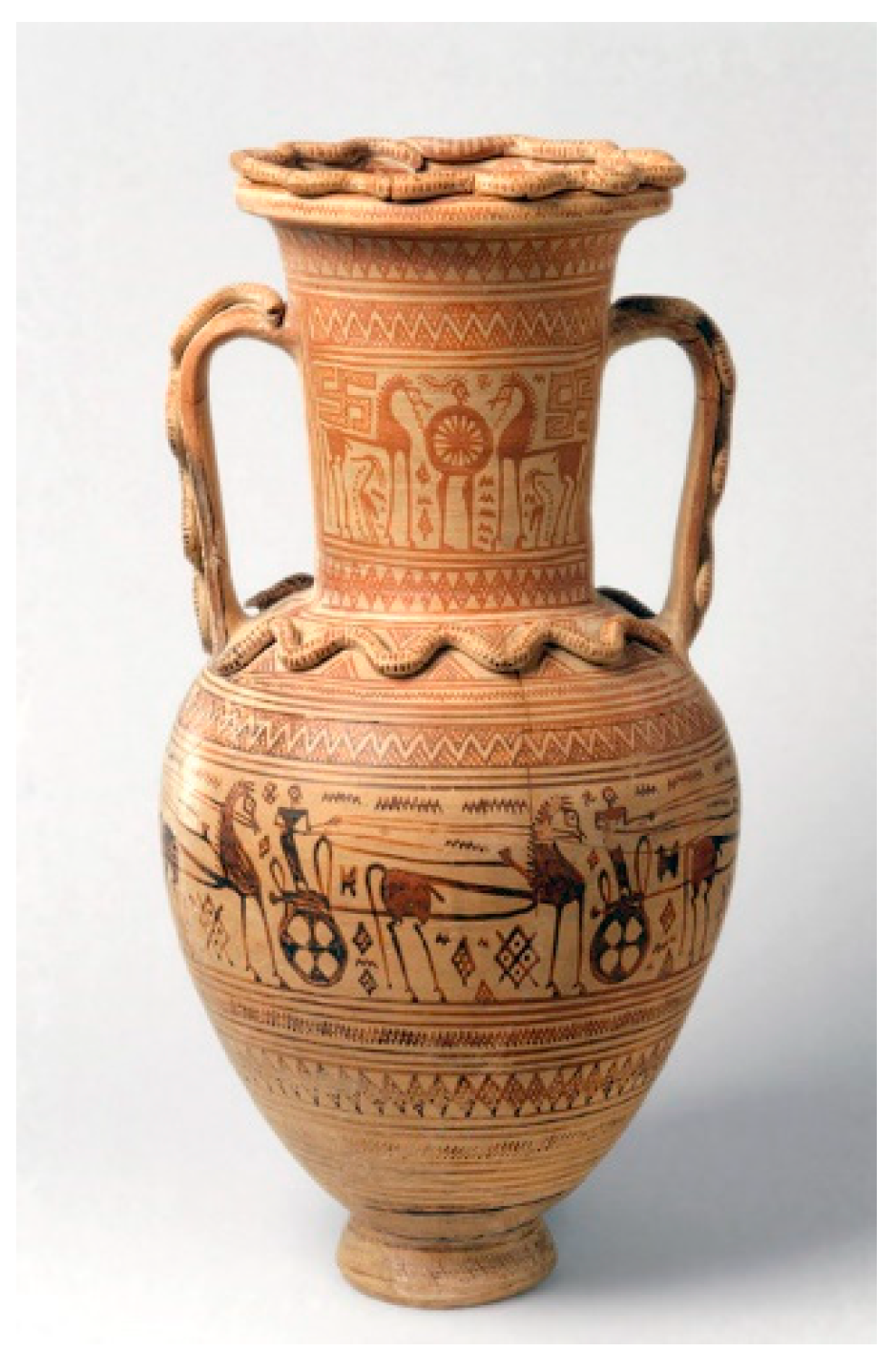

| 60 | E.g., MMA obj. no. 10.210.7 (Attic Geometric amphora); CUAM inv. no. 2006.36.T (Boiotian Geometric amphora); MFA acc. no. 92.2736 (Boiotian Geometric oinochoe); WAM acc. no. 48.2231 (Athenian Geometric amphora); for the interpretation that these anguiform appliques designating the soul of the deceased, already see Küster (1913, pp. 35–47); Nilsson (1950, p. 198, pl. 52, Figure 1). |

| 61 | NAM inv. no. CC688 (Athenian black-figure loutrophoros; BAPD no. 480; LIMC #4149); Harrison (1899, p. 219); Haspels (1936, pp. 115, 229 n. 59); Peifer (1989, p. 158, pl. 6, Figure 13, no. 76). |

| 62 | See discussion in (Rodríguez Pérez 2013). |

| 63 | MMA acc. no. 25.70.2 (Athenian black-figure lekythos; BAPD no. 390342; LIMC #29345); Haspels (1936, p. 233, no. 15); cf. Louvre inv. no. CA601 (Athenian black-figure lekythos; BAPD no. 11079; LIMC #32299); SAM inv. no. 1719 (Athenian black-figure hydria; BAPD no. 302008; LIMC #21483); BM reg. no. 1899,0721.3 (Athenian black-figure amphora; BAPD no. 301780; LIMC #4150); DAM inv. no. B6137.546 (Athenian black-figure lekythos; BAPD no. 302338; LIMC #20103); MFA acc. no. 63.473 (Athenian black-figure hydria; BAPD no. 351200; LIMC #311537). |

| 64 | The Greek εἴδωλον (eidolon, lit. “image, likeness”) is notoriously difficult to translate, ranging from ‘unsubstantiated form’ via ‘spiritual entity’ and ‘ghost, phantom’ to ‘statue.’ |

| 65 | |

| 66 | SMB inv. no. 4841 (BAPD no. 310022; LIMC #32582). Another example is one of the metopes of Orestes from Foce del Sele (Junge 1983, pp. 15–16). A 4th-century black-glazed guttus in the British Museum (reg. no. 1836, 0224.396) shows Orestes at Delphi pursued by an anguiform Erinys. |

| 67 | For the sacrifice of Polyxene, see BM reg. no. 1897,0727.2 (Attic black-figure amphora). |

| 68 | BAPD no. 14851 (Athenian black-figure lekythos); Haspels (1936, p. 198, no. 5); Grabow (1998), pl. 22 (K104). |

| 69 | I thank the anonymous reviewer for prompting me to articulate this assumption more explicitly. |

| 70 | Louvre inv. no. CA1739 (Corinthian black-figure alabastron; BAPD no. 9013950); NAM inv. no. 12.821 (Athenian black-figure lekythos; BAPD no. 370005); Haspels (1936, p. 198, no. 6, pl. 18, Figure 5). |

| 71 | BM reg. no. 1892,0718.2 (Athenian white-ground kylix; BAPD no. 209459); (Hoffmann 1997, pp. 120–26). |

| 72 | For the myth of Glaukos and Polyeides, see: Apollod. Bibl. 3.3; Hyg. Fab. 136. |

| 73 | |

| 74 | |

| 75 | |

| 76 | |

| 77 | See discussion of the introduction of Asklepios’ cult in Athens, including the Telemachos monument and the snake, in Parker (1996, pp. 175–87). |

| 78 | Livy, Per. 9.3; Ov. Met. 15.622–744; Val. Max 1.8.2; Paus. 2.10.2–3, 3.23.7. |

| 79 | Iamata 37, 42 (ed. LiDonnici 1995); Ar. Plut. 653–748; Paus. 1.34.5; Küster (1913, pp. 107, 121–22); Lupu (2003); Gil (2004, p. 354). |

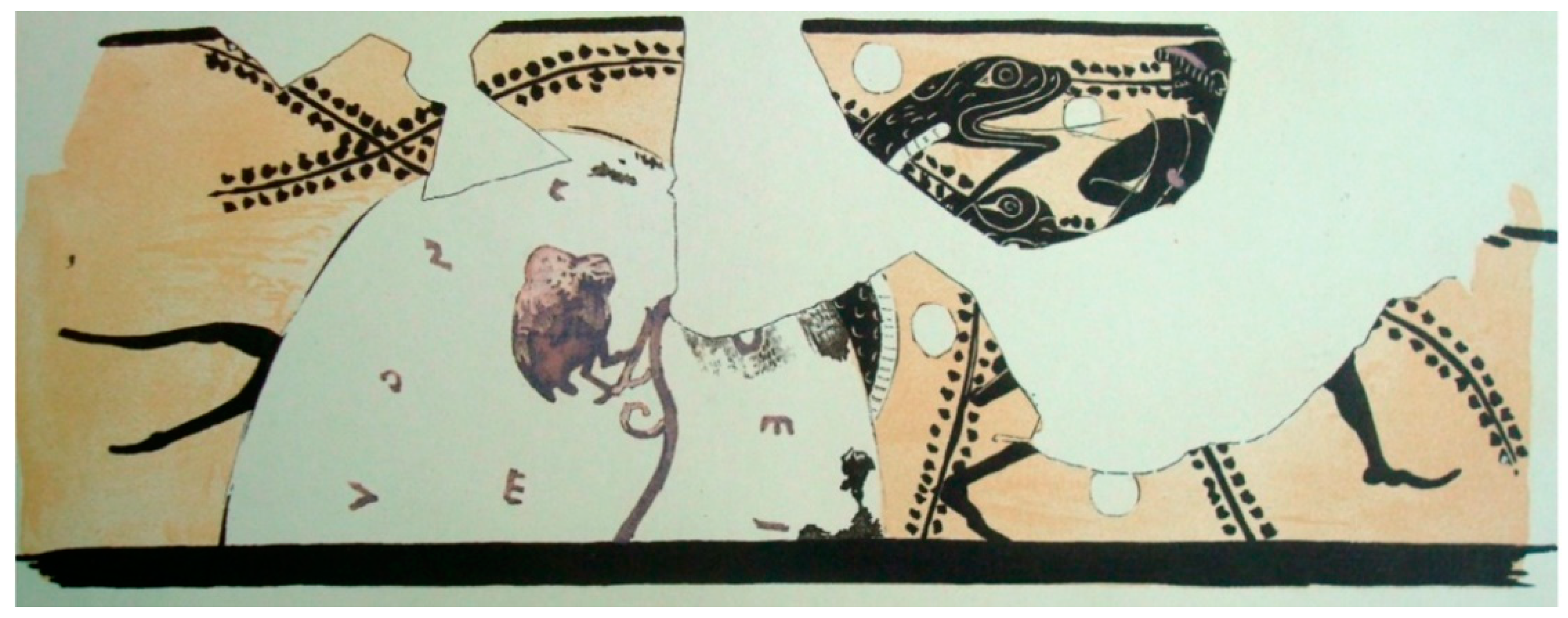

| 80 | Boardman (1995, p. 132, Figure 142); Lupu (2003, p. 325, Figure 2); Platt (2011, pp. 44–46) (with further lit.), Figure 1.6. |

| 81 | |

| 82 | For the possibility, that the relief might not represent the experience of a single individual but the various ways in which encounters with Amphiaraos, by one or many individuals, might occur, see Platt (2011, p. 46). |

| 83 | |

| 84 | It is not clear to me whether we are before an image of a bearded snake licking Archinos’ shoulder or rather a snake with the mouth full open biting him, as first-hand observation of the relief in Athens led me to think. |

| 85 | On the sometimes-puzzling interplay between epiphany, the act of dedication, and the ritual action/response see Platt (2011, p. 39). As she notes, the reflexive reference to the own material presence of the dedication created by the presence of the pinax in the relief emphasises the object’s role in transforming the ephemeral experience of divinity into a permanent, visible memorial of the god’s impact upon the physical world (p. 45). |

| 86 | While transmitting their cure through biting, snakes convey their prophecies by licking the ears; such as, Melampos, Teiresias, Helenos and Cassandra, or the Arabians from whom Apollonius of Tyana learnt the language of birds (Philostr. Vit. Apol. 1.20); Küster (1913, pp. 124–26). |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rodríguez Pérez, D. The Meaning of the Snake in the Ancient Greek World. Arts 2021, 10, 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts10010002

Rodríguez Pérez D. The Meaning of the Snake in the Ancient Greek World. Arts. 2021; 10(1):2. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts10010002

Chicago/Turabian StyleRodríguez Pérez, Diana. 2021. "The Meaning of the Snake in the Ancient Greek World" Arts 10, no. 1: 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts10010002

APA StyleRodríguez Pérez, D. (2021). The Meaning of the Snake in the Ancient Greek World. Arts, 10(1), 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts10010002