Abstract

This article explores the local histories and ecological knowledge embedded within a Spanish print of enslaved, Afro-descendant boatmen charting a wooden vessel up the Chagres River across the Isthmus of Panamá. Produced for a 1748 travelogue by the Spanish scientists Antonio de Ulloa and Jorge Juan, the image reflects a preoccupation with tropical ecologies, where enslaved persons are incidental. Drawing from recent scholarship by Marixa Lasso, Tiffany Lethabo King, Katherine McKittrick, and Kevin Dawson, I argue that the image makes visible how enslaved and free Afro-descendants developed a distinct cosmopolitan culture connected to intimate ecological knowledge of the river. By focusing critical attention away from the print’s Spanish manufacture to the racial ecologies of the Chagres, I aim to restore art historical visibility to eighteenth-century Panamá and Central America, a region routinely excised from studies of colonial Latin American art.

1. Introduction

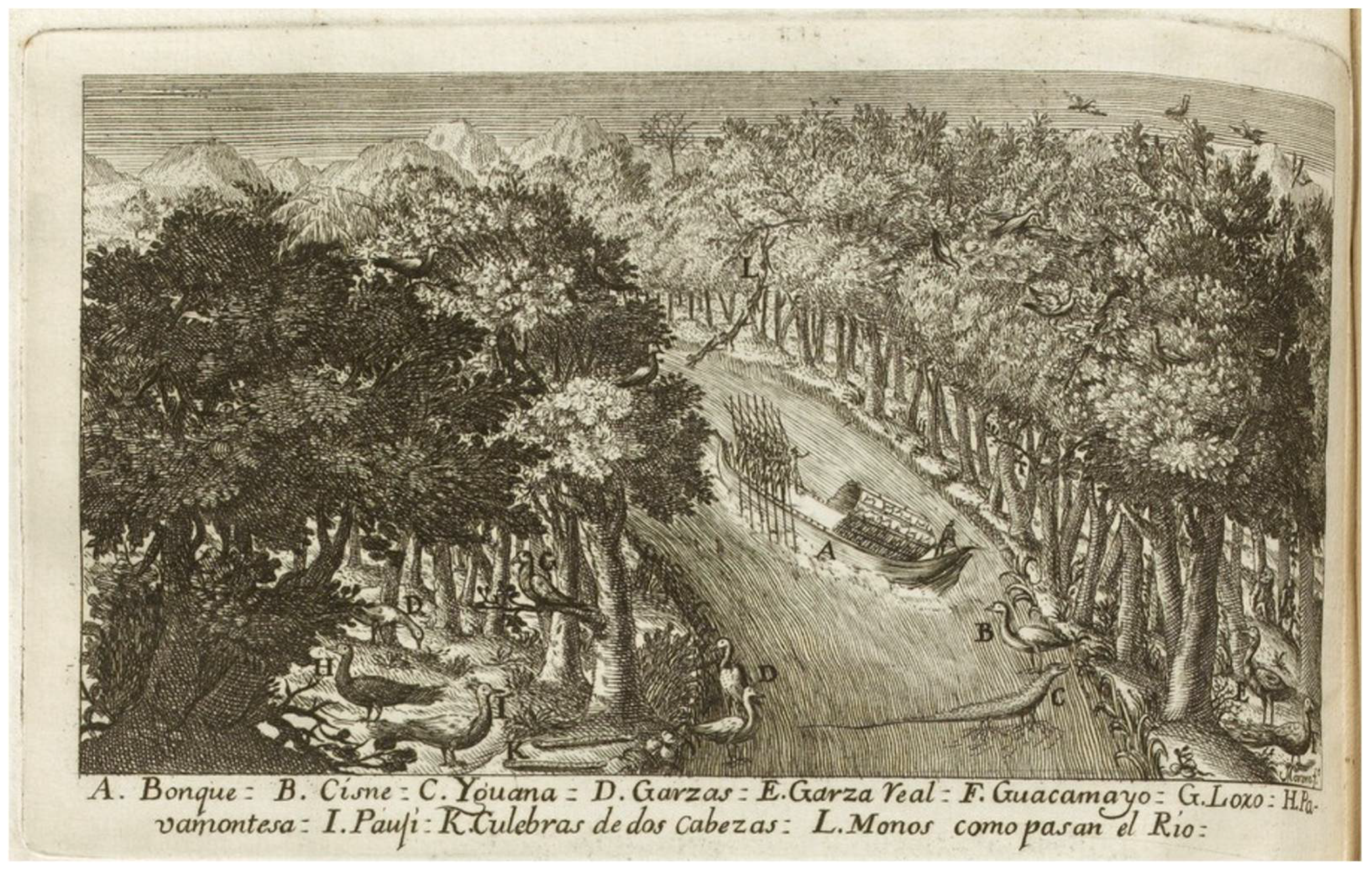

A boat ascends a coursing river (Figure 1). Fourteen oarsmen paddle against the force of the river’s downward stream towards a range of mountains. Despite the river’s coursing speed, flocks of birds have settled at the water’s edge. Swans and herons wade in cool waters as an iguana scuttles across the surface. Two-headed snakes slither along the ground, as a chachalaca (Ortalis ruficada, labeled here as Pava montesa) and other birds survey the scene. Above the river, small black monkeys form a chain as they swing from one bough of the canopy to the other, demonstrating a playful ease to navigating the forest that escapes the humans below. However, the bogueros, or boatmen, are hardly unprepared. They row with years of experience under their belts, having navigated up and down the Chagres River and across the Isthmus of Panamá innumerable times. Often enslaved and Afro-descendant, bogueros played a crucial role in the flow of silver, gold, and other precious goods and materials from the Pacific and Caribbean coasts of Latin America to the rest of the world. As they rowed along the river, they also dispersed other enslaved people throughout Latin America (O’Toole 2020).

Figure 1.

Illustrated chapter heading of Book Three “On the Journey from Portobelo to Panamá” (Ulloa and Juan 1748, p. 144). John Carter Brown Library. Image used with permission.

A Spanish printmaker by the name of Juan Moreno created this image of Panamá in Madrid, as an illustrated chapter heading in the 1748 tome Relación Histórica del Viage a la America Meridional (Ulloa and Juan 1748, p. 144). Penned by the Spanish scientists Jorge Juan and Antonio de Ulloa, the book narrated their journey from Cádiz to Quito and their efforts to measure the circumference of the Earth. Images were central to the book’s didactic function, expanding scientific accounts into engaging narratives by visualizing colonial cities, cultural customs, and landscapes of eighteenth-century Latin America. Upon their return to Spain, Ulloa and Juan supervised the careful creation of some forty-eight illustrations by Spanish artists including Juan Bernabé Palomino, Vicente de la Fuente, Juan Moreno, Carlos Casanova, Juan Pablo Minguet, Juan Fernández de la Peña, and Juan Palomino (Contreras and Iniesta 2015).

Art historian Daniela Bleichmar has established the visual culture of science in the Hispanic Enlightenment as an important site to investigate imperial formations of power relations (Bleichmar 2014; Bleichmar 2017). The illustrations in Juan and Ulloa’s books belong to this well-established genre of European expeditionary images, providing crucial insight into the eighteenth-century Spanish imaginary of colonial Latin America (especially the Andes) (Vega González 2010). Scholars have argued that Moreno’s image of Panamá is “the most well-known of all” of the book’s illustrations, enticing in its visualization of a “dangerous navigation system” (Contreras and Iniesta 2015). Moreno’s print is also distinctive for another reason: it renders enslaved black bogueros visible in a scholarly practice that usually insisted on blackness “remain[ing] in the interstices” (Safier 2008, p. 63). Seated under the thatched roof of the boat, the white European scientists Ulloa and Juan evade our gaze. This latent but invisible whiteness raises questions about the role of race within the image.

In Panamá, the print has taken on a different meaning, where, divorced from the original text, it appears as a routine illustration in history books about the isthmus (Castillero Calvo 2019, p. 620). The popular reproduction of this print marshals the image as foretelling visual testimony of Panamá’s transformation into a central hub of global commerce after the completion of the eponymous canal in 1915. Over the centuries, the 1748 image of the Chagres River has become synonymous with the canal’s historicity, supporting narratives of Panamá’s “predestined geography” to be a locus of intercontinental trade (Carse 2014, pp. 71–82). Yet, as Marixa Lasso has made clear, the creation of the Panamá Canal was dependent on the displacement and erasure of the country’s black citizenry (Lasso 2019). As humanities scholarship recenters Panamanians within accounts of Panamá (and away from twentieth-century U.S. actors), the historical significance of the Chagres River as a cultural space in the late colonial period—and the centrality of blackness therein—has emerged as an important avenue of inquiry.

In this essay, I contend that this 1748 print functions beyond its Spanish manufacture to reveal colonial Panamá, and the Chagres River in particular, as a historical space that has nourished black life and culture. In doing so, it follows models of black geographical thought developed by Katherine McKittrick, who urges us to pay attention to the “livingness” within a colonial archive of enslavement and dispossession (King 2019, pp. 30–31, 77–78). Closer consideration of the river’s enslaved bogueros establishes the racial valences of the isthmus’s aqueous ecologies, evoking Tiffany Lethabo King’s theorization of the black shoal as a liminal space that slows and disrupts white settlement. I therefore advocate for a shift in our positionality away from the print’s European Enlightenment manufacture in order to understand how the image embeds the ecological knowledge and cultures of colonial Panamanian actors.

2. Situating Colonial Panamá

The print’s focus on the slow ascent up the Chagres invites viewers to linger in the river’s liminality. In doing so, we can better see the complexity of our surroundings and reconsider the space of Panamá in eighteenth-century art histories. For art historians, the busy ports of Panamá City and Portobelo are important insofar that they are nodes in, say, the mobile networks of the Manila Galleons. Otherwise, the isthmus appears most often in lists that describe the geographical extent of the Viceroyalty of Peru (1543–1717) and later New Granada (1717/1739–1821), rather than as a site of cultural production. These Andean affiliations made colonial Panamá a clear beneficiary of and an occasional contributor to the famed Quito School. Seventeenth-century painter Hernando de la Cruz, for instance, traced his roots to Panamá, though his artistic activity was firmly in Quito and contributed little towards artistic production on the isthmus proper (Vallarino 1950; Ramírez 2013). Some of the earliest and most impressive churches on the isthmus, notably in Natá (or Natá de los Caballeros), feature the paintings and polychrome sculptures of Quito School artists.

An enduring emphasis on transit treats the isthmus as a site between cultures, rather than a site of distinct cultures, especially before independence from Colombia in 1903. This lacuna is especially conspicuous in the eighteenth century because of the closing of the Portobelo fairs (ferias) after 1739 (Ward 1993). The fairs had been the main Caribbean and Atlantic trading post for the Viceroyalty of Peru, where merchants exchanged Andean silver, New Granadan gold, textiles, cacao, tortoiseshell, and quinine for other global wares. The fairs were also the main impetus for the maintenance of transisthmian travel routes that utilized the Chagres River. After repeated attacks and sieges at Portobelo made the port an untenable location, the Spanish crown closed the ferias permanently in 1739.

Mercantilist histories exacerbate this absence of art historical investigation, suggesting that the closing of the Portobelo ferias ushered over a century of “decline” for Panamá, until the construction of the world’s first transcontinental railway across the isthmus in 1855 (Delgado et al. 2016, pp. 115–35). However, there are many reasons to consider the eighteenth century anew from a Panamanian perspective. When Antonio de Ulloa and Jorge Juan arrived to Portobelo in 1733, they witnessed one of the last fairs to take place, remarking that outside of the high season, free blacks were still active traders at the port (Ulloa and Juan 1748, p. 143; Lasso 2019, p. 57). Whether free or enslaved, Portobelo’s black majority called upon potent powers that made the city a sacred space. One legend recalls an angler who attracted a mysterious box ashore from a shipwreck. As it neared the shore, the object revealed itself as a polychrome wooden image of Christ. The unmistakable blackness of this Christ, what Renée Alexander Craft has described as “brown as or browner than most of the townspeople” (Craft 2015, p. 57), was redolent with curative properties. Arriving in the midst of a cholera epidemic, the Black Christ of Portobelo emerged as a potent devotional object to fold Afro-descendants into the colonial order, a legacy now enshrined in an annual pilgrimage on October 21 that draws thousands of devotees to the Panamanian town (Johnson 2019).

Meanwhile in the capital, fires would destroy a striking proportion of colonial Panamanian visual and material culture. Most notoriously, the 1671 sack of the city by British buccaneer Henry Morgan reduced the proud Pacific port city to rubble. Crucial to Morgan’s success was his collaboration with the isthmus’s substantial maroon communities, as well as indigenous insurgents, who acquired precious materials and goods from the capital before it burned to the ground. Rather than rebuild itself, the city relocated eight kilometers to the west, designating the ruinous site as Panamá Viejo (Castillero Calvo 2019, pp. 1401–38). Newly fortified, the city endured a series of fires in 1737, 1756, and 1781 that destroyed altars, paintings, sculptures, silverwork, and all other sorts of material production made in and for the isthmus’s wealthiest, most cosmopolitan city (Baquero 2019a, 2019b). Fortunately, the Museum of Colonial Religious Art in the district of Casco Viejo maintains a modest collection of colonial visual culture.

As the majority of the capital’s colonial visual culture is no longer extant, and the precise history of Portobelo’s Black Christ remains unclear, what Panamanian makers produced for local audiences and how they worked in concert with local needs remains vastly under-researched in comparison to other geographical subfields of colonial Latin American art. The renowned Panamanian anthropologist Reina Torres de Araúz undertook the greatest effort to chart an important episode of eighteenth-century Panamanian art history in her 1980 edited volume on the small but significant church of San Francisco de la Montaña (Torres de Araúz 1980). Many contributors hinted towards the important contributions of Ngäbe and Buglé artists in opulent painted wooden altars, but Torres de Araúz’s untimely death in 1983 stalled further research.

Mónica Kupfer and Luisa Fuentes Guiza have emphasized how marronage culture (independent communities of once-enslaved Afro-descendants who usually lived and operated outside of colonial frameworks in the Americas) strongly resonates in the realm of contemporary art, but similar art historical investigations focused on the late colonial period are rare (Kupfer 2018; Fuentes Guiza 2020). Outside of Panamá, scholars such as Renée Alexander Craft, Sonja Stephenson Watson, Peter Szok, and Katherine Zien have demonstrated the centrality of Afro-descendant cultural production to Panamanian culture in the twentieth century (Szok 2012; Craft 2015; Watson 2017; Zien 2017). While the print under question here is a European image of Latin America, the paucity of late colonial Panamanian visual culture and the image’s consistent dissemination in the country have made this particular picture relevant to, if not indexical of, Panamanian history. Re-establishing the cultures of eighteenth-century black bogueros as manifest in the 1748 print wields considerable importance in charting new art historical contours of colonial Central America, granting important historicity to black culture in Panamá (Gudmundson and Wolfe 2010).

3. River as Agent and Method

In their volume Liquid Ecologies of Latin American and Caribbean Art, Lisa Blackmore and Liliana Gómez advocate for the uncovering of Latin American art history’s “alternate engagements with liquidity […] in whose viscous engagements the human and non-human converge” (Blackmore and Gómez 2020, pp. 2–3). I extend their analytical lens of “thinking with water” (paraphrasing Astrida Neimanis) about Latin American art from the modern and contemporary into the colonial period, and specifically the eighteenth-century Chagres, in order to recover local knowledge and lived experience along the riverbanks.

Before the completion of the Panamá Canal, water only carried one so far across the isthmus. The Chagres originates in the interior mountainous rainforest of Panamá, charting westwards before it turns northwards towards the Caribbean. The river’s turning point became the foundation of Las Cruces, the transitional site where travelers switched from boats known as bongos or chatas rowed by enslaved men for mule-driven carts to complete the journey south to the Pacific coast (or vice versa). This itinerary, part fluvial and part terrestrial, was distinctive from the Camino Real, a direct land route between Portobelo and Panamá City. Ulloa and Juan made clear that the Chagres route was their only possibility, because “some of the instruments were too large for the narrow craggy roads in many parts, and others of a nature not to be carried on mules” (Juan and Ulloa 1767, p. 110). In the colonial period, animal breeders in El Salvador, Honduras, and Nicaragua took care to cultivate specific stocks of mules to bear the hefty burden of transporting Andean silver over the mountainous route between Panamá City and Portobelo (Castillero Calvo 2019, p. 614). When imperial demand exceeded equine capabilities, settler-conquistadors exploited the labor of the enslaved.

When Antonio de Ulloa and Jorge Juan departed the Caribbean port city of Portobelo, they were eager to rush across the isthmus to Panamá City on the Pacific coast, where they would finally depart for Quito and embark on their project. It is telling that the beginning of their chapter about crossing Panamá is a caveat: “It had always been our fixed design to stay no longer than absolutely necessary in any place.” The Chagres had other plans. Once the group began to ascend the river, the authors lamented that their oars were “too weak to stem the current,” so the bogueros had to “set the vessels along with poles.” Though neither of the young scientists performed any labor in moving the boat, they regretted the “slow and toilsome” manner of ascending the river, until they finally “found a great increase in the velocity of the river.” Consistently working against the currents, the expedition spent more time on the isthmus than anticipated and, in doing so, more time immersed in the river’s colonial cultures and ecologies.

The ecologies of the Chagres often interrupted navigation. The currents uprooted trees along the riverbank, felling “monstrous trunks” that would remain irritating impediments to any passersby. Submerged under water and invisible from the surface, these trunks posed a veritable threat to the structural integrity of the bongos and the safety of the bogueros and their settler-conquistador passengers. It was for this reason that a helmsman stood firmly at the back of the bongo, surveying the depths and keeping a keen eye out for potential danger. Beyond natural debris, the depth of the river changed variably. One might presume that shallow waters were slow, but currents could course quickly—even violently—over shallow depths.

The shifting depths of the Chagres invite the invocation of Tiffany Lethabo King’s theorization of the black shoal. A shoal is a shallow space, where “an accumulation of granular materials (sand, rock, and other) that through sedimentation create a bar or barrier that is difficult to pass” (King 2019, p. 2). At once land and water, the shoal disrupts liquid mobility, slowing vessels down. Similar to the underwater trees of the Chagres, shoals are often impossible to predict and therefore defy mapping. It is in this refusal—geophysical as well as epistemological—where King conceptualizes the black shoal as “a critique of normative discourses within colonial, settler colonial, and postcolonial studies that narrowly posit land and labor as the primary frames from which to theorize coloniality, anti-Indigenism, and anti-Black racism” in the Americas (King 2019, p. 4).

Embracing the metaphorical slowness and constant mutability of the shoal encourages a disruption of Eurocentric readings of the image in question, what King calls “a willingness to give up a preoccupation to take up another” (King 2019, p. 78) At stake in shifting this positionality is no less than a rejection of the tendency to read and therefore reproduce anti-black and anti-indigenous violence. Writing “narratives that emphasize black life,” as Katherine McKittrick calls us to do, “betrays the archive” in order to transcend its limitations (Quoted in King 2019, p. 78).

Though not following King or McKittrick, Juliet Wiersema’s art historical reading of a specific painted map of the Dagua River has revealed crucial information about Afro-descendant cultures and waterways in eighteenth-century New Granada (Wiersema 2018). In its geographical remoteness from Spanish oversight, the Dagua River fostered the potential to cultivate what would later become new Afro-Colombian cultures and identities (Wiersema 2020). The Chagres presents opposite political conditions. If the Dagua was remote, the Chagres was arguably one of the most traversed rivers in the Spanish Americas. The constant flow of people, materials, and goods across Panamá made it one of the most cosmopolitan regions of the Spanish Empire.

Scholars of Panamá often emphasize that istmeños were limited beneficiaries of this active global trade. Nevertheless, Jesús Sanjurjo Ramos suggests that we should understand colonial transisthmian routes as a “rupture, nexus, and border of oceans, continents, and societies” (Sanjurjo Ramos 2012, pp. 260–61). When we follow his thinking alongside McKittrick and King, we expand the Chagres River from a transitory road of commerce and exploration that exploited enslaved labor into “an unstable ecozone and nervous landscape where boundaries between the human and Black and Indigenous bodies continually shift” (King 2019, p. 78). It is here where we begin to see the livingness of the landscape and, on a larger scale, eighteenth-century Panamá.

4. A Pilot’s Potency

Tiffany Lethabo King conceptualizes the shoal as a method to unmoor blackness from, and bring indigeneity closer to, ideas of liquidity and water (King 2019, p. 9). For King, the shoal interrupts the prevalence of the oceanic (and thus, the Middle Passage) in Black Diasporic thought. However, Kevin Dawson finds that a “disregard [of] marine environmental variants” has hampered our understanding of enslaved life (Dawson 2013, p. 165). For Dawson, the distinctions between seas and swamps, rivers and oceans, are significant ones, as they directly determined the contours of everyday life and even the conditions under which one could negotiate power. Indeed, he argues that the liminality of certain waterways between the terrestrial and the aquatic—in our case, the part of the Chagres River between Las Cruces and the Caribbean—created a crisis of (white) authority, an opening where enslaved persons could exert explicit control, especially the figure of the enslaved pilot.

In the 1748 print, a single figure stands firmly at the stern of the bongo. He leans ever so slightly forward, shifting his weight as the vessel ascends the stream. By moving his body with the current, he stabilizes his position on board, ensuring his ability to survey not only hydroscapes of the Chagres before him, but also the entire boat, its crew, and its passengers. In this back position, he determines the direction of the bongo with a steering paddle, chanting orders at a clear volume so that his fellow bogueros can hear him over the rushing river, howling monkeys, and chattering birds.

Because most white people could not swim in the eighteenth century, waterways created a particularly potent place—Dawson would call it a “persuasive” place—for black captains, whether free or enslaved, to ward off typical racist abuse, harassment, or violence (Dawson 2018). One of Dawson’s leading arguments in his book Undercurrents of Power is the contention that many (enslaved) Africans and Afro-descendants in the Americas retained cultural and muscle memory of aqueous environments from the opposite side of the Atlantic (Dawson 2018). This knowledge fostered more than comfort or familiarity with water. It granted an epistemological advantage to Afro-descendants over settler-conquistadors. As Spanish scientists traveled up the Chagres, translating fleeting Panamanian landscapes into an Enlightenment sense of hierarchy and order, black ecological knowledge disrupted such classifications, with familiarity itself functioning as a metaphorical black shoal.

As Dawson observes, the singular position of the pilot, honed over years of experience, was not easily replaceable, granting him a distinguished position from more rote kinds of enslaved labor (Dawson 2013, p. 169). The fact that the Chagres had been a major transit site of the Spanish Empire for two centuries by the 1730s did not ensure simple navigation. The success of the pilot was dependent on his experience, as well as on how he negotiated the management of swift currents, felled trees, and even feisty crocodiles with his crew. In an ever-changing and rarely predictable fluvial landscape, the pilot had to balance his experiential knowledge—identifying changes in the color of water (to indicate depth) and where it heaves over shallows (to anticipate abrupt changes)—with a constant eye focused towards whatever was teeming at the riverbanks (Dawson 2018). The print here suggests abundant wildlife along the river’s edge. Animals traversed the river—a large iguana behind the boat, crocodiles below (described in the text), monkeys above—while the constant threat of shifting depths, submerged trees, and sandbars demanded equal vigilance.

A free or enslaved black helmsman could, and often had to, command nervous, non-swimming, white men to sit still and stop moving. Otherwise, their movements might capsize the boat. For Ulloa and Juan, the journey up the Chagres must have been a vulnerable one. The invisibility of the Spanish scientists in the print, therefore, occludes the real fears and anxieties of absolute white dependence on the black captain. As the awning of the boat obstructs our vision of Ulloa and Juan, it also limits their own sight of their surroundings. They rely on and expect that the pilot behind them will bring them to safety. Such ambivalence may explain why the sketch makes the animals more legible than the black oarsmen of the bongos, making most visible those elements of the Panamanian landscape that the scientists could classify and attempt to control.

5. Towards Boguero Culture

If the pilot steered the bongo, the bogueros sat at the front of the dugout, paddling forward against the current. Our print in question visualizes the bogueros as an indistinct, homogenous mass of bodies. We can distinguish them not by corporeal forms but, instead, by the fourteen slanted lines that represent the poles used to propel the vessel forward. In their narrative under this image, Ulloa and Juan recalled, “Each of these boats is equipped with twenty or eighteen strapping Blacks (Negros fornídos [sic]) and the captain. Without them, it would not be possible to climb up the river against the current” (Ulloa and Juan 1748, p. 148). The discrepancy between the visual suggestion of fourteen bogueros in the image and the recollection of eighteen to twenty in the text demonstrates the refusal of the white scientists who recalled and sketched the event to take black livingness seriously. The use of scale distinguishes the tropical landscape and its denizens from human figures. Because Juan Moreno’s print is likely a copy of a drawing by Jorge Juan, this visual difference reflects the white scientists’ prioritization of tropical flora and fauna—some of which, including the two-headed snakes, the authors admitted never having seen—over enslaved bogueros (Ulloa and Juan 1748, p. 168) Rendered at such a small scale, the bogueros appear incidental—indistinguishable tools of labor rather than individuals. Following the calls of McKittrick and King, I feel compelled to question what life we can notice in spaces where the settler-conquistador archive reveals only laboring black bodies.

We might begin by considering the origins of the bongo itself. Juan and Ulloa’s text is one of the most extensive archival writings on the construction of Panamanian bongos. They note the following:

“There are two kinds of boats that navigate this river: one known as chatas and the other bongos, or bonques in Peru. The former are made from pieces of timber, wide enough to not draw in water. These carry around six- or seven-hundred quintales. The bongos are made from a single piece [of wood], it is surprising to think there should be trees of such a prodigious bulk, some of them being eleven Paris feet broad, and carrying conveniently four or five hundred quintals. Both forts have a cabin at the stern for the convenience of the passengers, and a kind of awning supported with wooden stanchions reaching to the head, and a partition in the middle, which is also continued the whole length of the vessel. Over the whole, when the vessel is loaded, are laid hides, that the goods may not be damaged by the violence of the rains, which are very frequent here”(Ulloa and Juan 1748, p. 148). (Juan and Ulloa 1767, p. 140).

The felling and shaping of large trees to construct bongos held deeper significance beyond an onerous task demanded by the colony. Commensurate with the ban on indigenous enslavement across the Spanish Americas, the dugout canoes of enslaved Afro-descendants reflected the retention of African cultural knowledge and techniques of manufacture (Dawson 2018, pp. 43–63). I am not arguing that indigenous collaboration did not occur on the banks of the Chagres but rather that officially sanctioned navigation of the river was the sole domain of enslaved black bogueros in the colonial era. As Dawson relates, bogueros “layered African meanings onto waterscapes that once possessed Amerindian cultural values” (Dawson 2018, p. 204), creating new cultural spaces in the process.

One of the layers of African meaning reverberated in the river’s soundscapes. Paddling songs would have been the last sounds an enslaved person would have heard in Africa and among the first upon being transported from ship to shore in the Americas (Dawson 2018, p. 222). The cadence of songs provided a uniform rhythm that oarsmen could follow, utilizing paddles and poles not only as tools of transit, but also as percussive instruments. Songs could rally tired workers and create a new sense of community among newly displaced Africans of disparate cultural backgrounds (Dawson 2018, pp. 223–24). Some lyrics retained African languages, whereas others would adopt Creole words or eventually morph into colonial European languages (Iyanaga 2019). A British author traversing Panamá’s Chagres River in the nineteenth century penned an evocative passage about her experience of these songs:

“Our native rowers plied their broad paddles vigorously and swiftly, singing incessantly, and sometimes screeching like a whole flock of peacocks, with a hundred-horse power of lungs, Indian songs, with Spanish words; one of which songs was rather remarkable, inasmuch as, instead of being, as usual, full of the praises of some chosen fair, it was nothing but a string of commendations on the beauty and grace of the singer ‘I have a beautiful face,’ ‘I am very beautiful,’ &c.When we passed any boat—and in our flying craft, with our light luggage, we shot by immense numbers—the yells of triumph, I suppose, of our boatmen, and a sort of captain they had (who was clad in very gay-colored garments with a splendid scarlet scarf or sash to denote his rank, I conjecture) were literally almost deafening, and the beaten rowers were not slow to answer them, with shouts and shrieks of merry defiance, reproach, or mockery.Such a volley of volubility, I think, I never heard—it was the most distracting, bewildering, vocal velocity conceivable”(Stuart-Worthey 1851, p. 286).

When we look beyond the exoticizing descriptions (their voices as “screeching” or “shrieks”), we see songs of friendly competition, camaraderie, and pleasure. Racing past one another down the river may have even been a way to find delight in the banality of repetitive, arduous labor. It is important to note that the author here is experiencing the Chagres one year before the abolition of enslavement in Gran Colombia (of which Panamá was a part from 1821 to 1903) in 1851. Therefore, we can be confident that these songs were indeed part of boguero culture. What makes this passage so important is what it reveals about group formations. Bogueros not only worked in unison as a team at the front of bongos, but also cemented close social ties with one another, singing songs along the way. Her note that “the beaten rowers” responded quickly in a call-and-response manner further attests to the sophisticated sense of rivalry among the boatmen. Moreover, it suggests that the Chagres may have had its own songs.

Sounding the Chagres disrupts the colonial epistemologies of Ulloa and Juan’s travelogue, a black shoal that reveals black life before black labor. Thinking of the sonorous cultures of the river in turn transforms how we read the visual blending of the bogueros at the front of their dugout bongo. Rather than understanding the homogenization of bodies as an erasure of personhood, we might also think about how their overlapping visual presence embodies the “hundred-horse power of lungs” of the river’s floating choirs. The slanted lines that help us distinguish the fourteen oarsmen are more than tools of arduous labor for the white settler-conquistador passengers. They are also percussive instruments whose rhythms formed social bonds and created new communities along the Chagres. This shift in interpretative strategy emphasizes how, in McKittrick’s phrasing, we can “notice” what black life is already embedded in historical images of enslavement, beyond the intent or knowledge of Hispanic Enlightenment authors.

6. Marginal Metaphors

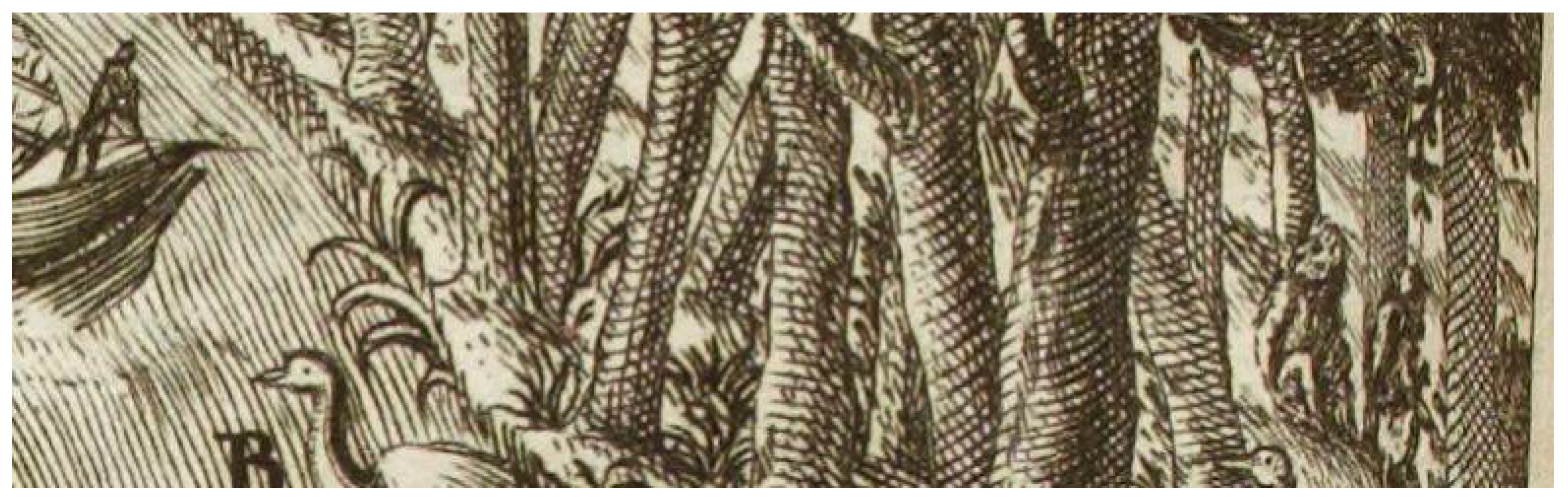

Close inspection of the margins of the bottom right-hand corner of the 1748 print reveals two figures who elude the image’s discrete labels (Figure 2). Hidden among the trees, they peer at the river from the safety of the forest. At such a small scale, both figures evade legibility, but they warrant investigation because one figure appears to make direct eye contact with—or, at the very least, stare at—the captain of the bongo. This suggestive gaze of the marginal figure raises questions about the relations that black bogueros and captains of the Chagres forged with the life—human and more-than-human—along the riverbanks, where King’s “unstable ecozone and nervous landscape” disrupts white navigation and progress.

Figure 2.

Detail of marginal figures on the right corner of Figure 1, Illustrated chapter heading of Book Three “On the Journey from Portobelo to Panamá” (Ulloa and Juan 1748, p. 144). John Carter Brown Library. Image used with permission.

Ulloa and Juan write evocatively about the ecozone of the Chagres, admiring its beauty as “picturesque” for its abundance of animals. They also describe the monkeys in racialized terms, delineating them into castas of negro and pardo, among others. This description plays a vital role in how they narrate eating habits along the Chagres. According to Ulloa and Juan, monkeys were a delicacy to the bogueros. Although the Spaniards conceded that “the taste of their meat was quite delicate,” the sight was “repugnant to the appetite” (Ulloa and Juan 1748, p. 149). The scientists recalled that bogueros would singe the hair off the monkeys in order to remove their fur. Once washed, all of the monkeys looked the same: casta affiliations disappeared with the hair to reveal the white complexion (cutis blanco) of the skin of the animals. This new whiteness was particularly horrifying for Ulloa and Juan because there was “no difference in size or appearance of a boy of two years old, who is crying and upset” (Ulloa and Juan 1748, p. 148). The implication is clear. They situate boguero eating habits within close proximity to accusations of cannibalism, extending a centuries-long European discourse about the Americas (Earle 2012). Unlike the small, playful monkeys swinging above the boats, these larger hidden figures may represent the scientists’ attempt to render those humanoid animals they described as so striking in their proximity to whiteness.

The evocation of the black consumption of white flesh in the text also invites considerations of another threat to white fragility looming along the riverbanks of the Chagres: maroons, persons who escaped enslavement to form new societies far from settler-conquistador control. One of the earliest colonial images of the Chagres painted in 1586 illustrates a text that makes explicit how the river was the safest way to avoid maroons:

“This river has been recently discovered by the Spaniards. It serves their shipping and carries gold and silver from the port of Panama distant by three leagues over land from Cap La Cruz in Panama and is the beginning of said river. When the fleet of ships from Peru arrives in Panama laden with gold and minted silver, they carry the gold and silver on mules over land to the Port of La Cruz in order to ship it in barges on said river to Nombre de Dios, thus avoiding the danger from the runaway negro slaves, commonly called thieves, from the port of La Cruz to the entrance of the sea which is the end of the river”(Histoire Naturelle 1586).

Although the 1586 text emphasizes the Chagres as a conduit of anti-blackness, in reality, maroon communities had long taken advantage of the river’s mercantilism in order to acquire iron, arms, wine, and other goods from the boats (Tardieu 2009, p. 140). A 1575 decree mandated that guards would be required to accompany every transit in order to protect embarkations from maroon attacks (Tardieu 2009, p. 149). This new posture responded to the 1571 sack of Panamá City, as well as the 1555–1566 insurrection of enslaved Africans known as the War of Vallano (sometimes Bayano) (Gallup-Díaz 2010).

If the heartbeat of marronage was its elusiveness, then the ambiguous figures of the margins may represent white fear of the unknown landscape beyond the riverbanks. Most accounts of maroon history in Panamá exclude the late colonial era, an irony made visible in the fact that our 1748 print features as the cover image of Carol Jopling’s edited primary source collection Indios y negros en Panamá, siglos XVI-XVII. Historian Ignacio Gallup-Díaz has made a compelling argument for why maroons disappear so quickly from accounts of Panamanian history. He argues that the historiography of colonial blackness marshals episodes of conflict and war with settler-conquistadors into a teleological narrative of pacification. In doing so, early historians transformed independent maroons into “controlled” imperial subjects of peripheral interest after the seventeenth century (Gallup-Díaz 2020, p. 11). The absence of eighteenth-century maroons, both discursively as well as visually in the print, serves as a reminder of limited Spanish control in the interior of the isthmus and the very real ways that black and indigenous inhabitants of the isthmus routinely disrupted and prevented colonial conquest.

Over the course of the eighteenth century, the Spanish Empire constantly grappled with the incompleteness of its conquest of the isthmus. Besides the port cities of Portobelo and Panamá City, “Hispanicized” areas were located closer to the Pacific coast and west of the capital, including the towns of Natá, Penonomé, Parita, Aguadulce, Las Tablas, and David. The majority of the western mountainous province of Veraguas featured limited colonial settlements, whereas Darién in the east became notorious for the tenacity of its indigenous populations—including Emberá, Wounaan, and, especially, Guna—in resisting Spanish control. A few years before Juan and Ulloa reached Panamá, a destructive indigenous insurgency leveled the mission at Yavisa (in Darién province) in 1727. Because peace negotiations would only be completed in 1735, native rebels remained an urgent issue for the Spanish on the isthmus at the time the scientists travelled down the Chagres (Gallup-Díaz 2003). Conspicuously unlabeled, the mysterious marginal figures of the print could also represent the unknown of the eastern frontier, as eighteenth-century Europeans continued to frame Darién as an untamable landscape (Velásquez Runk 2015). Both the Chagres and Darién highlight the agency of local communities, whose existence outside of a purely colonial paradigm furthers organic knowledge of the Panamanian context while scrutinizing the settler-conquistador narrative of Juan and Ulloa’s perceived experiences on the isthmus.

7. Conclusions

A map of the Chagres River in the Archive of the Indies from 1749 lists no less than seventy different stops along the river, ranging from tributaries to towns that dot the riverbank (Archivo General 1759). As Ulloa and Juan would admit later in their chapter on Panamá, at least two of the towns were majority (if not entirely) Afro-descendant (Ulloa and Juan 1748, p. 186). Twenty-four labels have an accompanying “R” inscribed next to them, signaling the likelihood of encountering a raudal, or swift current of the river. This map therefore presents the Chagres not as a river coursing through thick, uninhabited jungle, but a fluvial highway that cut through towns and settlements. This kind of Chagres, one actively populated by people, seems to foretell the vibrant nineteenth-century cultures of black republicanism that Marixa Lasso explores before the construction of the Panamá Canal (Lasso 2019). Printed ten years before the map, the 1748 print of Ulloa and Juan’s travelogue embodies a black livingness that the riverbanks had already nourished for centuries.

Whether enslaved or free, indigenous or maroon, Panamanians were crucial actors in the material networks of colonial Latin America, as the racial ecologies of the Chagres flowed beyond the riverbanks and terrestrial transition at Las Cruces. Ships departing Panamá City for the Guayaquil-Callao route passed by the Pearl Islands (Las Perlas). Ulloa and Juan wrote with striking clarity about the trials and tribulations of the enslaved divers who endured perilous underwater conditions in the collection of pearls. Mónica Dominguez-Torres has explored the global circulation of pearls harvested by enslaved divers in the Caribbean, but those from the Pearl Islands in the Bay of Panamá were in dialogue with Pacific port cities (Domínguez Torres 2015). These same pearls encrusted sacred objects across the Viceroyalty of Peru (Abramovich 2019).

As pirates came and went, fires destroyed cities, and the Portobelo ferias disappeared, the 1748 print visualized how the Chagres itself remained a fluvial site of new cultural formations, merging diverse modes of African knowledge onto an ecosystem already redolent with Amerindian significance. As they rowed up and down the river, singing songs to each other about their beauty, dignity, and competitive camaraderie, the black bogueros of the eighteenth-century Chagres hardly saw its waters as a place of decline. Their waters were home.

Funding

This research was made possible by the New Carlsberg Fundation any my postdoctoral fellowship connected to the international research project “The Art of Nordic Colonialism: Writing Transcultural Art Histories” at the University of Copenhagen.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank Alena Robin and Lauren Beck for their invitation to contribute to this exciting Special Issue on eighteenth-century arts in late colonial Latin America, the insights of the two anonymous peer reviewers, as well as Rogelio Cerezo, for his editorial prowess and role as an inimitable guide of Panamanian history and culture. All images have been sourced from digital scans of the John Carter Brown Library, which does not claim copyright over the book. See: https://archive.org/details/relacionhistoric03ullo/mode/2up.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Abramovich, Lucia. 2019. Precious Materiality in Colonial Andean Art: Gold, Silver, and Jewels in the Paintings of the Virgin. Ph.D. dissertation, Tulane University, New Orleans, LA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Archivo General de las Indias. 1759. Mapa del Rio de Chagre, comprehensivo de los tres Puestos que en el mismo Rio se reconocen desde su boca donde está el sitio y Castillo de Chagre (que demolieron los ingleses el año de 1741) hasta el sitio de Cruzes, con los nombres del Gatún y la Trinidad, los que se fortificaron y guarnecieron en la proxima passada Guerra con Yngleses: D[o]n Joseph Antonio Pineda, Sargento Mayor de la Plaza de Panamá, lo pone en manos del Señor D[o]n Antonio Guill y Gonzaga, Governador y Comand[an]te G[ene]ral. del Reyno de Tierra Firme, para el uso del R[ea]l servicio que su Señoria tenga por conveniente. MP-PANAMA 158. [Google Scholar]

- Baquero, Angeles Ramon. 2019a. Pintura y escultura en el arte colonia. In Nueva Historia General de Panamá: El Orden Colonial. Edited by Alfredo Castillero Calvo. tome 3. Panamá: Alcaldía, pp. 1263–80. vol. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Baquero, Angeles Ramon. 2019b. Platería y plateros en la Colonía. In Nueva Historia General de Panamá: El Orden Colonial. Edited by Alfredo Castillero Calvo. tome 3. Panamá: Alcaldía, pp. 1281–344. vol. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Blackmore, Lisa, and Liliana Gómez. 2020. Beyond the Blue: Notes on the Liquid Turn. In Liquid Ecologies of Latin American and Caribbean Art. New York: Routledge, pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Bleichmar, Daniela. 2014. Visible Empire: Botanical Expeditions and Visual Culture in the Hispanic Enlightenment. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bleichmar, Daniela. 2017. Visual Voyages: Images of Latin American Nature from Columbus to Darwin. New Haven: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Carse, Ashley. 2014. Beyond the Big Ditch: Politics, Ecology, and Infrastructure at the Panama Canal. Cambridge and London: The MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Castillero Calvo, Alfredo. 2019. Nueva Historia General de Panamá: El Orden Colonial. tome 3. Panamá: Alcaldía, vol. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Contreras, Ramón María Serrera, and María Salud Elvás Iniesta. 2015. Grabados y grabadores en la Relación Histórica del Viaje a la América Meridional (1748) de Jorge Juan y Antonio de Ulloa. In Antonio de Ulloa: La Biblioteca de un Ilustrado. Sevilla: Universidad de Sevilla, Biblioteca, pp. 77–86. [Google Scholar]

- Craft, Renée Alexander. 2015. When the Devil Knocks: The Congo Tradition and Politics of Blackness in Twentieth-Century Panama. Columbus: The Ohio State University. [Google Scholar]

- Dawson, Kevin. 2013. The Cultural Geography of Enslaved Pilots. In The Black Urban Atlantic in the Age of the Slave Trade. Edited by Matt D. Childs. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, pp. 163–84. [Google Scholar]

- Dawson, Kevin. 2018. Undercurrents of Power: Aquatic Culture in the African Diaspora. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. [Google Scholar]

- Delgado, James P., Tomás Mendizábal, Frederick H. Hanselmann, and Dominique Rissolo. 2016. The Maritime Landscapes of the Isthmus of Panamá. Gainesville: The University Press of Florida. [Google Scholar]

- Domínguez Torres, Mónica. 2015. Pearl Fishing in the Caribbean: Early Images of Slavery and Forced Migration in the Americas. In African Diaspora in the Cultures of Latin America, the Caribbean and the United States. Edited by Persephone Braham. Newark: University of Delaware Press, pp. 73–82. [Google Scholar]

- Earle, Rebecca. 2012. The Body of the Conquistador: Food, Race and the Colonial Experience in Spanish America, 1492–1700. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Fuentes Guiza, Luisa. 2020. Panama: Echoes of Marronage in Contemporary Art. Colección Cisneros. May 8. Available online: https://www.coleccioncisneros.org/editorial/featured/panama-echoes-marronage-contemporary-art (accessed on 10 February 2021).

- Gallup-Díaz, Ignacio. 2003. The Door of the Seas and the Key to the Universe: Indian Politics and Imperial Rivalry in Darién, 1640–1750. New York: Columbia University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gallup-Díaz, Ignacio. 2010. A Legacy of Strife: Rebellious Slaves in Sixteenth-Century Panamá. Colonial Latin American Review 19: 417–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallup-Díaz, Ignacio. 2020. European Expansion and Representations of Indigenous and African Peoples: A Distorted Vision. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Gudmundson, Lowell, and Justin Wolfe, eds. 2010. Blacks and Blackness in Central America: Between Race and Place. Durham: Duke University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Histoire Naturelle de les Indes. 1586. New York: Morgan Pierpont Library.

- Iyanaga, Michael. 2019. On Hearing Africa in the Americas: Domestic Celebrations for Catholic Saints as Afro-Diasporic Religious Practice. In Afro-Catholic Festivals in the Americas: Performance, Representation, and the Making of a Black Atlantic Tradition. Edited by Cécile Fromont. State College: Penn State University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, S. Kyle. 2019. Panama celebrates its black Christ, part of protest against colonialism and slavery. The Conversation. October 10. Available online: https://theconversation.com/panama-celebrates-its-black-christ-part-of-protest-against-colonialism-and-slavery-122171 (accessed on 13 January 2021).

- Juan, George, and Antonio de Ulloa. 1767. A Voyage to South-America: Describing at Large the Spanish Cities, Towns, Provinces &C. on that Extensive Continent. Interspersed throughout with Reflections on the Genius, Customs, Manners, and Trade of the Inhabitants; Together with the Natural History of the Country and an Account of Their Gold and Silver Mines. London: L. Davis and C. Reymers. [Google Scholar]

- King, Tiffany Lethabo. 2019. The Black Shoals: Offshore Formations of Black and Native Studies. Durham and London: Duke University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kupfer, Mónica. 2018. Sandra Eleta: El Entorno Invisible. Panamá: Fundación Casa Santa Ana. [Google Scholar]

- Lasso, Marixa. 2019. Erased: The Untold Story of the Panama Canal. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- O’Toole, Sarah. 2020. Securing Subjecthood: Free and Enslaved Economies in within the Pacific Slave Trade. In From the Galleons to the Highlands: Slave Trade Routes in the Spanish Americas. Edited by David Eltis, Alex Borucki and David Wheat. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, pp. 149–75. [Google Scholar]

- Ramírez, Susan Rocha. 2013. Los Imaginarios Sociales Sobre el Infierno en la Pintura de Hernando de la Cruz, 1629. Master’s thesis, Universidad Andina Simón Bolívar, Quito, Ecuador. [Google Scholar]

- Safier, Neil. 2008. Measuring the New World: Enlightenment Science and South America. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sanjurjo Ramos, Jesús. 2012. Caminos transísmicos y ferias de Panamá, siglos XVI–XVIII. Anales del Museo de América 2012: 260–71. [Google Scholar]

- Stuart-Worthey, Lady Emmeline. 1851. Travels in the United States, etc., during 1849 and 1850. New York: Harper & Brothers. [Google Scholar]

- Szok, Peter. 2012. Wolf Tracks: Popular Art and Re-Africanization in Twentieth-Century Panama. Jackson: University of Mississippi Press. [Google Scholar]

- Tardieu, Jean-Pierre. 2009. Cimaronnes de Panamá: La forja de una Identidad Afroamericana en el Siglo XVI. Madrid: Iberoamericana Editorial. [Google Scholar]

- Torres de Araúz, Reina. 1980. San Francisco de la Montaña: Joyel del arte Barroco Americano. Panama: Instituto Nacional de Cultura. [Google Scholar]

- Ulloa, Antonio de, and Jorge Juan. 1748. Relación Histórica del Viage a la America Meridional hecho de orden de S. Mag. para medir Algunos Grados de Meridiano Terrestre, y venir por ellos en Conocimiento de la Verdadera Figura, y Magnitud de la Tierra, con otras varias Observaciones Astronomicas, y Phisicas. Madrid: Antonio Marin. [Google Scholar]

- Vallarino, Teresa de. 1950. La vida y el arte del Ilustre Panameño Hernando de la Cruz z S.J. de 1591 a 1646. Quito: Prensa Católica. [Google Scholar]

- Vega González, Jesusa. 2010. Ciencia, arte, e Ilusión en la España Ilustrada. Madrid: Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas. [Google Scholar]

- Velásquez Runk, Julie. 2015. Creating Wild Darién: Centuries of Darién’s Imaginative Geography and its Lasting Effects. Journal of Latin American Geography 14: 127–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, Christopher. 1993. Imperial Panama: Commerce and Conflict in Isthmian America, 1550–1800. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press. [Google Scholar]

- Watson, Sonja Stephenson. 2017. The Politics of Race in Panama: Afro-Hispanic and West Indian Literary Discourses of Contention. Gainesville: University of Florida Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wiersema, Juliet. 2018. The Manuscript Map of the Dagua River: A Rare Look at a Remote Region in the Spanish Colonial Americas. Artlas Bulletin 7: 71–90. [Google Scholar]

- Wiersema, Juliet. 2020. Importing Ethnicity, Creating Culture: Currents of Opportunity and Ethnogenesis along the Dagua River in Nueva Granda, ca. 1764. In The Global Spanish Empire: Five Hundred Years of Place Making and Pluralism. Edited by Christine D. Beaule and John G. Douglass. Tucson: University of Arizona Press, pp. 267–90. [Google Scholar]

- Zien, Katherine. 2017. Sovereign Acts: Performing Race, Space, and Belonging in Panama and the Canal Zone. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).