1. Introduction

Belgian art historian and filmmaker Paul Haesaerts (1901–1974) made several important contributions to the promotion of Flemish art. After his studies in painting, architecture, law, and philosophy, he became a jack-of-all-trades, working as a painter, illustrator, architect, and, above all, as an art critic. From the 1930s onwards, he was a principal member of the Flemish art scene and part of Belgian artistic organizations such as

Les Compagnons de l’Art and

La Jeune Peinture Belge (

Thirifays 1951;

Maes 2015). Together with his brother Luc Haesaerts, he founded the journal

Les Beaux-Arts in 1930, publishing widely on Flemish modern art. In 1931, the brothers also published the influential book

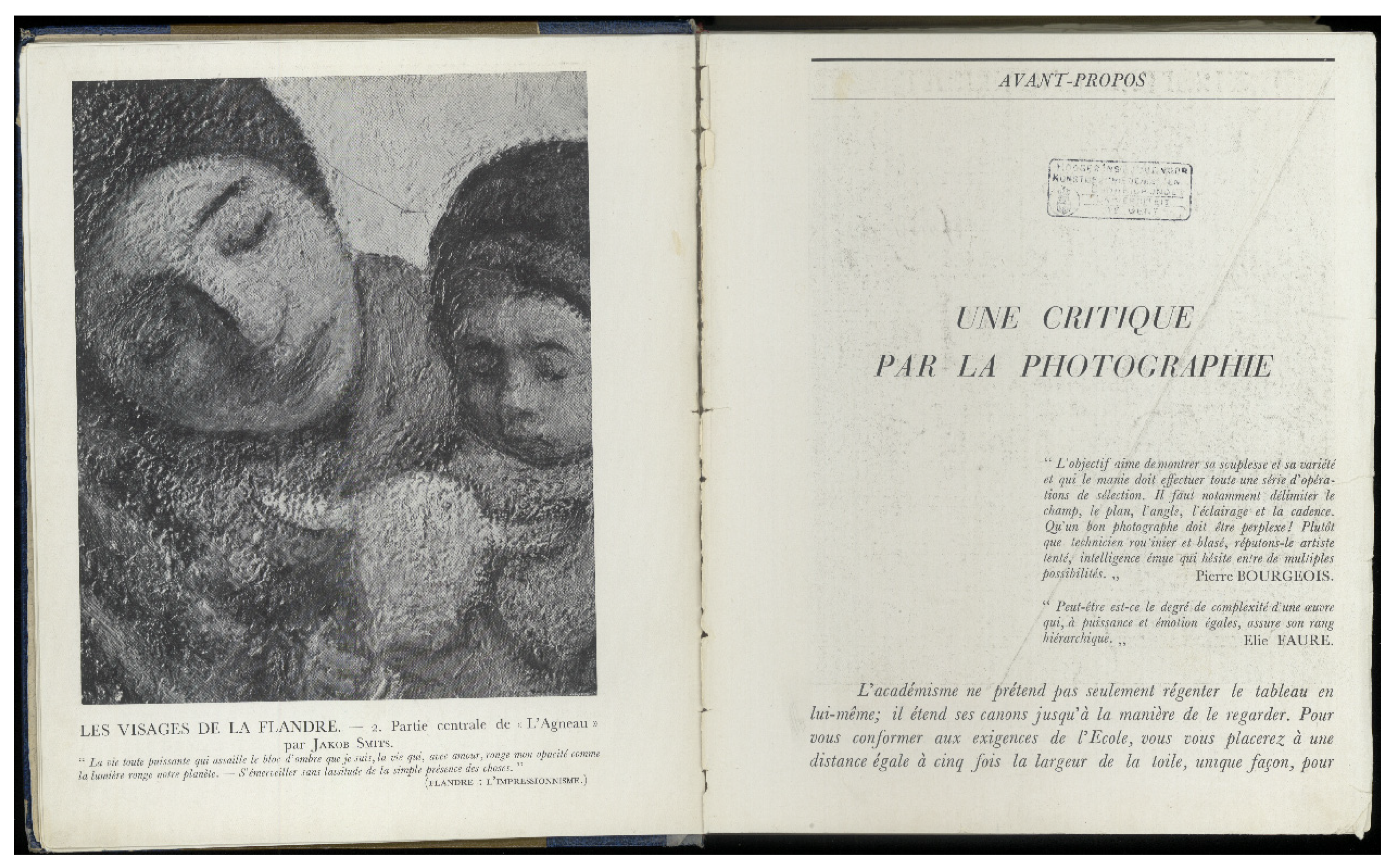

Flandre: Essai sur l’art flamand depuis 1880. Their close friend and artist Edgard Tytgat created a portrait of them with their celebrated book on the foreground (

Figure 1). This book on Flemish impressionist painting was striking, as it developed its arguments by means of illustrations, every left page showing only a combination of reproductions (

Haesaerts and Haesaerts 1931) (

Figure 2). The following years, Paul Haesaerts would continue to publish books on Belgian artists like George Minne (1939); Gustave De Smet (1939); Henri De Braekeleer (1940); Henri Evenepoel (1940); Permeke (1940) and James Ensor (1957), in which the innovative use of photographical reproductions remained highly important. An advocate of Belgian modern and contemporary art, Haesaerts also curated several international exhibitions on Flemish artists, and he often gave lectures on Belgian artists at museums and universities.

Shortly after World War II, Haesaerts started exploring a whole new way of practicing art criticism by experimenting with the medium of film. He particularly acquired fame and success with some landmark art documentaries (

Jacobs and Vandekerckhove 2020). Haesaerts’s first film,

Rubens (1948)—made in collaboration with Belgian filmmaker Henri Storck—presents the Belgian Baroque painter as a master of ultimate flexibility by means of a highly mobile camera, rapidly rotating images, and animated circles that point out the characteristics of his compositions, focal points, divisions, and his predilection for spiral-shaped movements. Additionally, in his landmark film

De Renoir à Picasso (1950), Haesaerts called in a wide variety of animation techniques, split screens, overlap dissolves, multiple exposures, and parallel editing in order to trace three inspirational sources of modern art—the so-called sensual or carnal (Renoir), the cerebral (Seurat), and the instinctual or passionate (Picasso). Following his concept of

cinéma critique, Haesaerts attempted to let images speak for themselves, presenting the medium of film as an analytical tool.

Haesaerts’s endeavors in the field of cinema coincided with the heyday of the experimental and lyrical art documentary in Europe. In the late 1940s and early 1950s, illustrious filmmakers such as Alain Resnais, Luciano Emmer, Glauco Pellegrini, and Robert Flaherty presented the film on art as a highly poetic genre that enabled them to combine cinematic experiments with artistic profundity. In addition, leading producers, directors, and museum officials co-founded FIFA (Fédération international du film sur l’art) in 1948, which supported the production, distribution, and critical contextualization of films on art. Particularly in Belgium, this resulted in a series of high-quality experimental films on art (

Jacobs 2011, pp. 1–38;

Bowie 1954;

Ragghianti 1951). What is more, Belgian directors like Charles Dekeukeleire, Henri Storck, André Cauvin, and Luc de Heusch recurrently presented canonical Belgian painters such as Jan van Eyck, Hans Memling, Peter Paul Rubens, and James Ensor in their films as key figures in Western art history.

1 Additionally, Paul Haesaerts created numerous documentaries on Belgian artists such as

Masques et visages de James Ensor (1952),

Un Siècle d’or. L’Art des primitifs flamands (1953),

Le Parc du Middelheim à Anvers (1953), and

Laethem-Saint-Martin: Le village des artistes (1955).

This article focuses on Haesaerts’s extraordinary color film Quatre peintres belges au travail (1952), which shows the creation process of artworks by Belgian painters Edgard Tytgat (1879–1957), Albert Dasnoy (1901–1992), Jean Brusselmans (1884–1953) and Paul Delvaux (1897–1994). Largely shot in the artists’ studios, Haesaerts creates a poetic portrait of the artists, repeatedly showing them painting on a glass pane placed in front of the camera. Although Quatre peintres was screened and praised internationally, the film remains largely understudied. Based on original archival research, this article attempts to reconstruct the film’s production process and reception. It also investigates in what way this documentary addresses Haesaerts’s notion of cinéma critique, a form of lens-based art criticism. Focusing on Haesaerts’s portrayal of the artists’ movements and interactions with their artworks in the studio space, it discusses how Haesaerts attempted to reconcile the spatial art of painting with the temporal medium of film. Finally, it situates Haesaerts’s footage of Belgian artists in the context of previous cinematic explorations of the artist’s studio and the international promotion of Flemish culture.

2. Preparations, Production and Premiere

Following the premiere of Haesaerts’s first film

Rubens at the 1948 Venice Biennial (where it won the Golden Medal in the category of films on visual arts), Haesaerts created two films on French modern art entitled

De Renoir à Picasso: Trois aspects de la peinture contemporaine (1950) and

Visite à Picasso (1950) (

Turfkruyter 1948). In both documentaries—commissioned by the French government—Haesaerts presents Picasso as the ultimate embodiment of the modern artist. Inspired by Sasha Guitry’s landmark film

Ceux de chez nous (1915),

Visite à Picasso also includes shots of Picasso at work. Apart from appropriating Guitry’s footage of the painter Auguste Renoir, Haesaerts visited Picasso in his studio in the Mediterranean village Vallauris in May 1949. This resulted in unique footage of Picasso walking in front of his studio where he handles various canvasses, lining them up. The film also features Picasso painting on a transparent plate of plexiglass placed between the artist and the camera (

Figure 3). In these remarkable sequences, we see the creation and development of images, displaying familiar motifs of Picasso’s oeuvre: birds, a bull, a vase with flowers, and female nudes. In so doing, Haesaerts literally sets Picasso’s static paintings in motion, bringing them to life as it were. In addition, these iconic images of Picasso creating life-size figures on the invisible planar surface of glass triggered Haesaerts to create a new short film entirely dedicated to Belgian artists.

In the autumn of 1951, Haesaerts discussed his ideas for a film entitled Quatre peintres belges au travail with the Belgian Ministry of Public Education (Christophe and Haesaerts 1951). He specifically planned to create a documentary that shows the creation process of artworks by Belgian painters Edgar Tytgat, Albert Dasnoy, Jean Brusselmans and Paul Delvaux. Adopting his previously used cinematic techniques of Visite à Picasso, he showed these artists working on a large sheet of glass placed in front of the camera, as they each paint one of the seasons. These seasons also represent a stage in a person’s life: spring and childhood in the case of Tytgat, summer and youth for Dasnoy, autumn and adulthood for Brusselmans and winter and death in the case of Delvaux. Haesaerts’s intention was to subsequently exhibit these finished panels in the permanent collection of the Ghent museum (Van Raemdonck and Vandendael 1951; Haesaerts and Musée des Beaux-Arts de Gand 1952; Haesarts and Christophe 1952). However, due to a lack of institutional and financial resources, the finished panels were finally acquired by Musée des Beaux-Arts de Liège (Christophe and Haesaerts 1952; Van Raemdonck and Bosmant 1952) and are now housed in the Haesaerts archives kept at the Musée des Beaux-Arts in Brussels.

In the press release of the film, Haesaerts proclaimed that the artists—who were all related to Flemish Expressionism and were at the height of their artistic career around the interwar period—were “chosen to represent four profoundly different facets of contemporary Belgian art.”

2 Additionally,

Quatre peintres would be “at the same time a document about current painting in Belgium, a series of portraits of artists and a study of four pictorial methods” (Haesaerts and Van Raemdonck Press 1952). In the context of UNESCO’s post-war humanist ideal of cultural emancipation and reconstruction through education, public authorities often encouraged the production of films that exhibited a national pride, in view of propagandistic and touristic exigencies (

Barry 1952, p. 2). In addition, the Belgian government showed a special interest in Haesaerts’s film that promoted Flemish culture. In a letter to the Belgian Ministry for Public Education (Cinema Department), Haesaerts and Van Raemdonck also claimed their film would be “extremely useful for fine arts schools, for works of popular education and also for the dissemination of Belgian art and culture abroad” (Van Raemdonck et al. 1952). Subsequently, the 16mm color film was produced by Haesaerts’s own production company

Art et Cinéma, which he had founded in 1949 together with his brother-in-law Jean Van Raemdonck, and financially supported by the Société Royale des Beaux-Arts de Liège and the Belgian government (

Bolen 1978;

Willems 2015).

3As Haesaerts and Van Raemdonck started filming in early spring 1952, the painted panels were finished by September 1952 (Haesaerts and Lucien 1952). In the following months, the Kodachrome color images were developed in the Kodak studios in Paris (Van Raemdonck and Valdes 1952). Belgian filmmaker Charles Conrad assisted with the final editing as different versions of the film in French, Dutch, English and Italian were created (Van Raemdonck and Conrad 1952). Finally,

Quatre peintres belges au travail premiered at the Musée des Beaux-Arts de Liège in April 1953, accompanied by a lecture by Paul Haesaerts (Haesaerts and Christophe 1953). In addition, the documentary was nominated for the

Mostra Internazionale d’Arte Cinematografica at the 1953 Venice Biennial. Renowned film critic Francis Bolen praised Haesaerts not only for “defending his artistic theories”, but especially for succeeding “to communicate an artistic emotion in front of the general public” (Bolen 1952). In local newspapers, the film was especially applauded for its “technical and artistic qualities” and its “remarkable colors that managed to faithfully translate the colors of the paintings” (

J. R. 1954).

The artistic universe of these painters proved to be a beloved subject for numerous other post-war art documentaries as well. For instance, Tytgat was filmed by Floris Jespers in his studio in the late 1940s and his paintings were the center of the documentary

Huit dames d’Edgard Tytgat (Jean and Raymond Antoine, 1968) (

Tytgat et al. 2017). In addition, the documentary

Albert Dasnoy was created by Christian Bussy et Claude Lebrun in 1973. Additionally, Delvaux appeared in several films on art such as

Règne du silence ou l’art de Paul Delvauw (Eric Blanckaert, 1959) and

Paul Delvaux ou les femmes défendues (Henri Storck, 1969). However, it was especially Storck’s first film on the artist entitled

Le Monde de Paul Delvaux (1946), produced by Luc Haesaerts’s production company

Séminaire des Arts, which received major success (

Knight 1952, p. 13). This film also inspired Paul Haesaerts to include Delvaux’s mysterious oeuvre in his own films on art (Haesaerts 1950).

3. Four Belgian Painters at Work

The thirty-minute film

Quatre peintres belges au travail opens with images of hands with particular red nail varnish holding color reproductions of the richly decorated miniatures of

Les Très Riches Heures du duc de Berry (c. 1415) by the Limbourg brothers. While the voice-over declares that the representation of seasons is an old and popular theme in art, the camera gently scans

The Months series (c. 1565) by Bruegel and various Épinal prints. After this brief prologue, the documentary is divided into four parts, each one introduced by an explanation of the life and oeuvre of the four participating artists (

Figure 4).

Showing close-ups of artworks such as

Bouquet ‘Envie’ (1922),

La Berceuse de Jocelyn (1923) as well as contemporaneous paintings like

Le chasseur maudit (1952), Haesaerts introduces Tytgat’s oeuvre as “an art of joy, flowers and freshness of spring.”

4 After a selection of Tytgat’s beloved motifs of fairs, games and acrobats, several of his wood engraved illustrated artbooks appear.

5 In the following establishing shots of the surroundings of Tytgat’s studio, Haesaerts presents us the artist. We follow Tytgat as he prepares his artwork on spring and childhood. We encounter a little girl whom the artist had chosen as his model as he hands her a colorful flower wreath. The next sequences (shot by Belgian cinematographer Fernand Tack) demonstrate the artist drawing his sketches on the grid of the glass pane’s exterior. A variety of close-ups of his hands and eyes draw the viewers’ attention towards the concentrated process of the painter. As the voice-over highlights the peculiarity of painting on a transparent canvas, Tytgat pays attention to both the front- and the backside of the plexiglass plate. Slowly but surely, the little girl, some sailors and a loving couple are brought to live with “tender and joyous colors.”

6The following scene introduces Albert Dasnoy. A diverse range of his portraits, landscapes and nudes “that have a sculptural appearance” present Dasnoy as an “excellent portraitist” who has the ability to “render nuanced expressions, looks and smiles that reveal the intimate spirit of beings.”

7 Haesaerts also pays attention to Dasnoy’s activities as an art critic, showing several of his art historical books. With these shots, Haesaerts not only refers to the blurred boundaries of academic and artistic work, but he also positions himself explicitly in the field of the ongoing scholarly research on modern Belgian art, using film as a new art historiographical tool. Explicitly linking his filmic exploration of modern art to print media and the illustrated art book, Haesaerts demonstrates that art has entered Walter Benjamin’s “age of mechanical reproduction” or André Malraux’s contemporaneous

Musée imaginaire (

Malraux 1952–1954).

8 In the following sequence, we witness Dasnoy’s process of creating his painting on youth and summer. Contrary to Tytgat, Dasnoy traced various compositions on small surfaces of glass that cover his entire studio floor. A close-up of his palette shows his limited selection of green and white color tones. We then follow his smooth brushstrokes as he draws the contours of a woman’s face, large trees and a distant skyline on the back side of the glass. Layer by layer he gives more depth and color on the panel’s front side. As he waits to apply new coats until the previous ones are perfectly dry, the voice-over concludes how “with patience and looking at the work from a distance, the final result will be revealed in the end.”

9Next up is Jean Brusselmans, whose “significant colors and rigid compositions” are characterized by Haesaerts as “rigorously harmonized by its realism and its harsh poetry” (

Haesaerts and Brusselmans 1939, p. 12). Extreme close-ups of

L’Arc-en-ciel (1932) and

La Tempête (1936) demonstrate the painter’s “predilection for the sea and its changing colors,” as well as his particular pointillism that is “made of vigorous and broad constructivist dots.”

10 Haesaerts filmed several of Brusselman’s views of Dilbeek, a village West of Brussels, and other landscapes in diverse museum collections, galleries, as well as in his own private collection (

Haesaerts 1951).

11 Before starting to paint his composition of autumn and adulthood on the glass panel that was placed in the middle of his studio, Brusselmans examines some charcoal drawings on large sheets of paper. A high angle shot shows him studying his composition of a landscape with two tall figures harvesting fruits. After delicately arranging his utensils and colors, he applies his first layers of paint on the transparent plane with brush strokes that are “broad, attentive but decided.”

12 The voice-over adds that Brusselmans’ dominant colors of bright blue, purple and green are “expertly dosed,” as he paints the fruits of autumn in his “typical geometric and strict style.”

13Last but not least, Haesaerts presents us the painter Paul Delvaux. As the camera scrutinizes the artist’s dream-like characters of uncanny nudes, marble statues and classical architecture in desolate nocturnal landscapes, the voice-over presents Delvaux as “a descendant of Lucas van Leyden and Hans Baldung” with his surrealist characters that are “dreamed of by Proust and evoked by Maeterlinck, attempting to return from the places of memory.”

14 The next sequence announces the painter and his model, a skeleton, as he prepares for his artwork centered around winter and death. Carefully placing his composition of a skeleton in an iron cage within an eerie landscape surrounded by plants and lifeless forms, the painter confronts his preliminary sketches with real-life objects. As touch-ups on a surface of glass are more difficult than on a regular canvas, Delvaux proceeds gradually, seeking the right angles and colors. Haesaerts further refers to Delvaux’s creation process as “a battle” that “constantly needs to be monitored with extreme caution.”

15 Finally, the artist manages to transpose the reduced dimensions of his sketches to a universe of dark blues and moonlight glow on the glass pane. In the final scene, the results of the entire panels are revealed with the voice-over’s concluding remarks: “The girl who served as a model for Tytgat, a shy

printemps figure finally meets the macabre model of Delvaux. Her crown of spring flowers then discovers the image of Winter. Life and death come together, as the cycle of seasons is closing.”

16 4. Haesaerts’s Art Criticism in Color

In the years immediately following the Second World War, not only renowned filmmakers, but also leading art historians such as Roberto Longhi, Lionello Venturi, Giulio Carlo Argan, Henri Focillon, Pierre Francastel, Carlo Ludovico Ragghianti, and Gaston Diehl showed great interest in art documentaries. Occasionally, they were also involved in the production of such films. For these art historians, cinema was not only capable of bringing art to wider audiences, it also made it possible to compare, analyze, and investigate artworks in original ways.

17 Films on art, consequently, became tools of the art historian, generating new art historical methods and paradigms. This notion was crucial for Haesaerts. Yet, unlike most of his colleagues who collaborated with film directors, he went beyond the traditional role of advisory expert or author of the voice-over text, taking the full responsibility of the film’s form and content. With his films, the art documentary entered into the domain of art analysis. Through various cinematic devices such as camera movements, split screens, dissolves, animation techniques, and showing the artists at work, his films not only provided an art historical reading of the artworks, but also presented a formal analysis of the artworks.

Considering both the camera and its mechanically reproduced images as indispensable instruments for the modern art historian, Haesaerts argued for new photographic and cinematic kinds of art criticism by using juxtapositions, sequences, and close-ups: a

critique par la photographie or a form of criticism through or in photography (

Haesaerts and Haesaerts 1931, pp. 11–27). With his following concept of

cinéma critique, Haesaerts also presented the medium of film as a “new instrument of investigation and thinking,” that enables us to comprehend artworks in an original way (Haesaerts 1948). In a 1951 lecture, he stated that “the beauty of a phrase (…) may easily distract us from the quality of the artwork, whereas a harmonious movement of the camera or successful lighting can never distance our judgment from the real value of the filmed object.” In addition, he advocated for the replacement of words with images to let discourse become “an eloquent succession of images” (Haesaerts AICA 1951).

Quatre peintre belges au travail is a perfect example of Haesaerts’s

cinéma critique. Apart from the titles of the artworks that are included in this “film of experimental order” and the collections where they are situated, Haesaerts’s elaborated script also contains the commentary voice-over texts and specifications on the use of cinematic techniques, camera movements and the original soundtrack composed by André Souris (

Haesaerts 1951). The script for

Quatre peintres also comprises notes and handwritten clarifications by Haesaerts himself, emphasizing that, for example, “the mobile camera needs to express the extreme vitality of these paintings from different angles and diverse points of view” (

Haesaerts 1951). Similar to his other productions, Haesaerts also made sketches and drawings on photographic reproductions of the selected paintings as visual indications for his cinematographer Fernand Tack.

18 Additionally, Haesaerts specifically distinguished three types of

cinéma critique corresponding to the possibilities of textual criticism: the anecdote, technical analysis, and lyrical representation, which are combined in

Quatre peintres belges au travail. The film shows anecdotal information of Tytgat, Dasnoy, Brusselmans and Delvaux in their studio. Haesaerts also presents a technical analysis of their paintings by demonstrating the act of their creation. According to Haesaerts, however, the most important component of a

film d’art relies on its lyrical representation that attempts to express a personal message through a work of art, a style or time (Haesaerts AICA 1951). Central to this idea that a film on art has to adopt the style and rhythm of the artworks being filmed. “The camera has to borrow its gestures and demeanour from the subject it is talking about,” the art historian states. “It has to be

trecento with Giotto, impressionist with Renoir, classical and Poussinesque with Poussin, baroque and Rubensian with Rubens” (Haesaerts 1948).

In this regard,

Quatre peintres pays significant attention to the painters’ personal expression of a “tender color palette” in the Kodachrome color film (

Haesaerts 1951). Launched in 1935 by Leopold D. Mannes and Leopold Godowsky of Eastman Kodak, the subtractive Kodachrome principle used three emulsions—each corresponding to a primary color—which are coated on a single film base. In his preparatory notes, Haesaerts planned for each part of the film to have its own prevalent color, corresponding to the overall mood of the painter: yellow for Tytgat, white and green for Dasnoy, rust for Brusselmans and blue for Delvaux (

Haesaerts 1951).

19 He also collaborated with color adviser Paul Faniel, who would continue to work with Haesaerts on his Gevacolor film

Un Siècle d’or: L’art des primitifs flamands (1953). With its ability to capture vibrant colors, Kodachrome was also perfectly fit for documenting the painters’ artistic process. However, because of its complex processing requirements, Haesaerts’s 16mm films frequently had to be returned to the manufacturer in Paris for processing that slowed down the production process substantially (Van Raemdonck and Valdes 1952; Van Raemdonck and Kowalski 1952; Drabbe and Pottier 1952).

5. Screening the Artist Studio

In

Quatre peintres belges au travail, Haesaerts aspired to “present some characteristic artworks and recreate an atmosphere specific to Tytgat, Dansoy, Brusselmans and Delvaux, whose working methods and styles are eminently personal and differentiated” (Haesaerts and Van Raemdonck 1952). Not only did the film evoke the artists’ individual style through its rich color contrasts, it also tried to grasp the painters’ psyche by demonstrating them at work. Throughout his career, Haesaerts maintained a close relationship with Tytgat, Dasnoy, Brusselmans and Delvaux as they regularly collaborated on other artistic projects, illustrated art books and exhibitions. Creating films in which the “personality of the painter and his immediate surroundings are central,” Haesaerts often corresponded with these artists to gain new insights on their artistry (Haesaerts and Rigot 1948). In addition, the original idea was to have all artists discussing their ideas on the film’s subject in the opening shot of the documentary (

Haesaerts 1951). Instead, the film immediately gives a unique view of the artists’ studios and attempts to highlight the painters’ individual approach. In so doing, Haesaerts mainly focuses on showing the diverse stages in the development of the creations instead of merely exploring finished artworks (

Figure 5).

As showing a static artwork in the dynamic medium of film was sometimes considered a somewhat unchallenging task, many filmmakers favored the motif of the creation of an artwork. Already in the 1910s, French director and actor Sacha Guitry had portrayed several leading French artists at work in his aforementioned

Ceux de chez nous. Especially Guitry’s portrayal of Jean Renoir inspired Haesaerts to create his own documentary on Belgian artists (Haesaerts and Janlet 1948). In the 1920s, Hans Cürlis made the landmark series

Schaffende Hände that showed Max Liebermann, Lovis Corinth, Käthe Kollwitz, Max Pechstein, Wassily Kandinsky, Otto Dix and others at work (

Cürlis 1955, pp. 172–85;

Thiele 1976, pp. 15–18). However, particularly in the 1940s and 1950s, many art documentaries continued this tradition like

Aristide Maillol, sculpteur (Jean Lods, 1943),

Calligraphie japonaise (Pierre Alechinsky, 1956),

Magritte, ou la leçon de choses (Luc de Heusch, 1960), and

Henri Matisse (François Campaux, 1946). Additionally, in 1946–1947, renowned French filmmaker Alain Resnais made a series of 16 mm films in the studios of artists such as Henri Goetz, César Doméla, Félix Labisse, Lucien Coutaud, Hans Hartung, Christine Boumeester, and Max Ernst, while Haesaerts contributed to the subgenre as well with

Visite à Picasso (1950) and

Masques et visages de James Ensor (1952). This indicates that filming the artist at work became a highly popular practice in the years shortly after the Second World War. This is not a coincidence, as the focus on the act of creation tallied perfectly with the aspirations of contemporaneous artistic currents such as Action Painting or lyrical abstraction, which celebrated an expressionist style of painting implying vigorous manual activity and powerful bodily movements.

Like many of the other aforementioned films, Haesaerts’s

Quatre peintres belges au travail does not only show the event of the artwork’s creation, it also makes clear that some form of intensified temporality is inscribed in the works by Tytgat, Dasnoy, Brusselmans and Delvaux. The temporal development of these artworks is not only emphasized by the different stages of the artist’s paintings, but also in their subject of seasons and moments in a person’s life. As the voice-over commentary emphasizes the artistic practice as “a game of both chance and skill,” the mechanical gaze of the camera shows the artists thinking, doubting, and repeatedly making corrections to their drawings.

20 According to Philip Hayward, however, this “extreme fetishisation” of the actual moment of creation resulted in the production of films that “have merely served to highlight the shortcomings of this approach” (

Hayward 1988, p. 7). Additionally, journalists criticized the repetitiveness of Haesaerts’s film, stating that “despite all his ingenuity and some pretty successful images, the Brussels critic’s experience leaves you hungry for more” (

L. J. 1954). These critics are referring to the at times tedious routine of showing four artists creating four paintings within the same context and with similar subjects. Although Haesaerts specifically aimed at demonstrating each of the painter’s individual approach, the general outline of the documentary indeed stays quite monotonous.

This demonstrates the duality in aspiring to capture spontaneous moments of creativity with the device of a film camera: the moment a film camera is placed, this spontaneity is lost one way or another. Haesaerts was highly aware of this process as he wrote an article entitled

Picasso devant la camera in which he described the artist’s awareness of the “giant eye of the camera” as one of the main obstacles on the set of his film

Visite à Picasso: “Picasso’s refusal to act as an actor, the impossibility of making him, at the desired moment, restart a gesture or rediscover an expression hardly facilitate the work of anyone who wants to present him on screen” (

Haesaerts 1951, p. 44). However, contrary to numerous biopics on canonical artists like Picasso, Van Gogh or Michelangelo, Haesaerts does not dwell on this “magical process” of artists at work, but rather attempts to create a cinematic equivalent of the artist’s style and technique.

21 Instead of copying popular ideas on the “genius modern artist,” Haesaerts deliberately avoids such rhetoric. He keeps his voice-over texts as neutral as possible in order to let the artworks “speak for themselves.” Although

Quatre peintres belges au travail, to a certain extent, undoubtedly contributed to the processes of mystification of the artistic process, it also unveils this mysterious act of creation, showing Tytgat, Dasnoy, Brusselmans and Delvaux in their everyday surroundings.

Evidently, this simultaneous presentation of the emerging drawings and the artist himself was made possible by the device of the sheet of plexiglass placed between the artist and the camera. This use of translucent material in order to show the creation process proved to be particularly successful. It was applied in several acclaimed documentaries from the fifties that all adopted Haesaerts’s technique, such as Jackson Pollock (Paul Falkenberg and Hans Namuth, 1951) and Le Mystère Picasso (Henri-Georges Clouzot, 1956). In line with the aesthetics of gestural abstraction, which combines physical and biographical aspects of the artist’s personality, Haesaerts used carefully selected camera positions to suggest an organic connection between the artists and their works of art. As the artists paint both the front and back of the glass, the camera directs our attention to the artist’s physical gestures. Showing close-ups of their hands and squinted eyes, it put forward the painters seemingly immersed in their paintings. Yet, they are unmistakably aware of their attitude and appearance in front of Haesaert’s camera as some of them look straight into the lens.

6. Conclusions

Haesaerts’s

Quatre peintres belges au travail not only serves as an intriguing piece of

cinéma critique and as a tribute to the fascinating process of artistic creation, it also functions as a promotional tool, supporting the international spread of Flemish culture in view of the encouragement of local tourism. What is more, the production of

Quatre peintres coincided with the politics of popularization and democratization of the fine arts. In the early 1950s, the cultural involvement of the lower and middle class was growing significantly. This resulted in the breakthrough of the photographically illustrated art book, as well as a higher number of museum visits. Haesaerts’s films on art not only had the ability to bring artworks of diverse international collections to a broad non-expert public, these films also traveled across the world themselves, enhancing the spread of local art on an international level. This increased the international interest in Belgian artists such as Tytgat and Delvaux which in their turn resulted in more museum visits of foreign tourists in Belgium to visit these artworks in real life.

22 (

Jacobs and Vandekerckhove 2020;

UNESCO 1951). In addition, the Belgian government favored productions of documentaries that presented national artworks and financially supported several of Haesaerts’s films (Haesaerts and Christophe 1952).

23 Also, the finished panels that were especially created for this film contributed to this political strategy. In a letter to the Buying Committee of the Musée des Beaux-Arts de Gand, Haesaerts stated that by purchasing these panels, “the Ghent Museum would have the merit of adopting an unusual formula likely to arouse new interest in museums.” He was convinced that his color film “would serve as propaganda that would encourage both Belgian and foreign audiences to visit or revisit the Museum” (Haesaerts and Musée des Beaux-Arts de Gand 1952).

Apart from the democratizing ability of cinema to bring paintings closer to a wider audience, Haesaerts’s also presents his

cinéma critique as a curatorial space with artistic qualities in its own right. Although it is undoubtedly a didactic film on art, it also self-consciously touches upon the boundaries between painting and film, oscillating between art and reality and stillness and movement. According to Phillip Mosley, Haesaerts’s

Quatre peintres “displays a consistent fusion of subjective and objective elements.” In addition, he stated that Haesaerts’s “impeccable scholarship is counterbalanced by an idiosyncratic approach to his material” (

Mosley 2001, p. 83). Thanks to the illusion of the artistic universe by Tytgat, Dasnoy, Brusselmans and Delvaux a new cinematic illusion is created by using cinematic techniques and devices. In so doing, Haesaerts convincingly put forward his film on art as a new model of art historical scholarship.