1. Introduction

Those who destroy the lie promote Ma’at; those who promote the good will erase the evil. As fullness casts out appetite as clothes cover the nude and as heaven cleans up after a storm.

To “destroy the lie” is to “promote Ma’at”, which means that one may understand ma’at as the idea of rightness or correctness, or truth, order, and balance. The Moaning of the Bedouin also describes the antithesis of ma’at, which is “evil”, but more specifically “injustice, disorder, and unreason“ (

Hornung 1992, p. 136). According to Erik Hornung, these qualities embody the ancient Egyptian conception of chaos, or “isfet”. Ma’at encapsulates a plurality of meanings that connote ideas of “harmony”, “justness”, “rightness”, and “order” (

Anthes 1954) and is foundational to many aspects of ancient Egyptian religion and social life.

1 Ma’at may also be conceptualized as a force that governs the cosmos and reinforces “the sense of stability desired by the Egyptians” (

Goff 1979, p. 180;

Morenz 1973, p. 113). To maintain this stability, there is a constant cosmic struggle between order and chaos (

Hornung 1982, p. 213;

Kemp 2006, pp. 6–7;

Muhlestein 2011, pp. 1–3).

One of the king’s roles is to maintain “ma’at”, which may involve banishing elements of isfet, such as foreign people who threaten the Egyptian way of life (

Robins 1997, p. 17). In the images of kings smiting cowering foreign captives, there seems to be a clear dichotomy of triumphant, lawful (orderly) good versus chaotic (disorderly) evil that must be subdued (

Figure 1).

Similar in pose to Egyptian kings bludgeoning foreign enemies with mace heads on temple facades, elite non-royal Egyptians raise one arm to catch wild birds with their throw sticks (

Figure 2). While the artistic context of the depictions of foreign enemies being subdued by the king is different from the fowling scenes found in tombs, this visual parallel suggests that wild animals were sometimes equated with foreigners, and vice versa (

Robins 1997, p. 17).

2 Just as foreign prisoners of war are bound and constrained in Egyptian art,

3 animals are shown bound and controlled through reins and leashes (

Evans 2010, p. 182, Figure 11-21, Figure 11-22, Figure 11-23). Foreigners are sometimes shown behaving in ways that are identical to wild animals, as if to dehumanize them and emphasize their placement outside of the ordered Egyptian world. When animals are chased in the hunt, they turn their heads back to their attacker. This movement, which evokes fear and weakness, is identical to the depictions of foreigners who look back toward the pharaoh who is about to deliver the fatal blow of his mace head.

The ancient Egyptian artistic stylistic canon is a result of relatively long-lived and comprehensive invariance,

4 which Whitney Davis describes as “images regarded as acceptable or well-formed according to particular standards of correctness” (

Davis 1989, p. 3). Davis characterizes the nature of ancient Egyptian artwork as highly organized, consistent, rigid, and “governed by a single set of formal and iconographic principles” (

Davis 1989, p. 3) or conventions that regulate the subject matter, as well as the figural proportions, composition layout, and measurements.

Because the images and motifs in ancient Egyptian art are iconic and are immediately recognizable, so would be, one assumes, the symbols and representations of “chaos” and “order”. Visually and conceptually, “ma’at” may be wrapped up in the orderly Egyptian world and can include depictions and representations of the cultivated, “civilized” region of Egypt with its domesticated animals, strict social hierarchy, and behaviors and customs that are specifically Egyptian. “Isfet”, or chaos, on the other hand, could be anything that potentially threatens this order; the implication is that the wild lands and animals beyond the cultivated land of Egypt, the breaching of social boundaries, and foreign behaviors and customs essentially embody chaos (

Robins 1997, pp. 17, 69;

Vanhulle 2018, p. 174;

Hendrickx 2006;

Hendrickx and Eyckerman 2010;

Raffaele 2010;

Hendrickx 2011;

Friedman et al. 2011).

Recently Axelle Brémont and Niv Allon have questioned how strictly ancient Egyptian culture adhered to a binary division of order and chaos by reassessing visual and textual iconography (

Brémont 2018;

Allon 2021). This article complements Brémont and Allon’s skepticism by studying the degree to which order and chaos were conveyed artistically through formal analytic considerations. One goal of this article is to challenge earlier, as well as some current, scholarly assumptions that animals, as “potential elements of chaos”, are depicted in a looser, more disorderly fashion that strays away from the ancient Egyptian artistic canon

5 (

Riggs 2013, p. 157).

The predynastic combs and knife handles, and early dynastic cosmetic palettes, which frequently depict wild (and sometimes supernatural) animals, will be discussed first. Though not directly influencing later pharaonic images, which will also be examined, the predynastic and early dynastic materials serve as an important foundation in understanding ancient Egyptian artistic conventions and iconography.

Given that art historians often only cite the New Kingdom tomb imagery in illustrating the organic quality in which nature and its animals are depicted, this article also briefly surveys the tomb imagery from the Old Kingdom and the Middle Kingdom. This initial investigation shows that there is an underlying sense of order and rigidity in how wild animals have been depicted, which challenges the assumptions that the disorder and chaos of the wild animal world are expressed stylistically and compositionally in ancient Egyptian art.

6 The fluid representation of motion seen in the New Kingdom animal imagery, a quality that leads to interpretations that these animals encapsulate spontaneity and therefore chaos, is acknowledged but interpreted differently.

2. Previous Interpretations of Animal Imagery and Predynastic and Early Dynastic Material

Decorum in ancient Egyptian art and culture was highly valued, which meant that the subject matter was often restricted (

Riggs 2013;

Baines 2007, pp. 18–29;

Baines 1985, pp. 277–95). For instance, Egyptian people are rarely represented with open mouths, even when they are depicted in situations where an open mouth would be expected. In Old Kingdom

Reden und Rufe scenes,

7 Egyptians are depicted talking and yelling at one another, yet the mouths of the figures are closed and remain essentially expressionless. In New Kingdom banqueting scenes, men and women eat, drink, and even vomit, but never with open mouths. With few exceptions,

8 open mouths are never shown, which would suggest that this behavior, as natural as it is, might be considered indecorous and even animalistic.

9 One might argue that animals are sometimes shown vocalizing, eating, and drinking with open mouths and protruding tongues as if to emphasize their crude inhuman behaviors.

10In tandem with this interpretation, Whitney Davis, Henriette Antonia Groenewegen-Frankfort, and Naguib Kanawati have argued that the ancient Egyptians depict animals—domestic and wild—with more artistic freedom than their human counterparts:

“Drawing an animal was not regulated by precisely the same representation of the human figure.”

“The coherence of animal forms in drawing is a simpler matter than that of human beings […]”

“The Egyptian artist was sensitive to nature and allowed himself more freedom in expressing it.”

However, there are shortcomings with Davis, Groenewegen-Frankfort, and Kanawati’s broad conclusions about the so-called freedom and exaggeration in depictions of animal locomotion and behavior. For one, their observations are focused on representations in pharaonic history, which ignores the standard of animal depiction set in the predynastic and early dynastic periods. Secondly, recent formal analyses demonstrate that the representation of animals is not as free as these scholars have presumed.

The predynastic and early dynastic periods (ca. 4400–2649 BCE) include the ancient Egyptian cultures living in the Nile Valley from the fourth to the second half of the third millennium BCE. Visually and conceptually, the predynastic and early dynastic imagery is distinct from pharaonic Egyptian art in that it is much more abstract and symbolic, with meanings that can change according to the medium and context in which an image is used (

Vanhulle 2018, p. 174). However, these Neolithic and early Bronze Age people established what would become pharaonic ancient Egyptian culture; their objects and images provide Egyptologists and art historians with a way to understand the development of ancient Egyptian iconography and modes of representation (

Patch 2011).

The predynastic and early dynastic materials are striking in their level of visual organization. For instance, the predynastic ivory knife handles and combs show animals walking along in neat processions, either from left to right or from right to left. It is clear from some of the types of animals represented, such as elephants and lions, that we are looking at wild animals that exist in areas well outside the cultivated area of the Nile River Valley. Despite being wild, they are certainly not demonstrating wild behaviors here.

The animals are represented in an almost identical fashion row to row and are also frequently organized according to species. However, sometimes one may find an “intruder”, where a different animal may be found in a row of animals. In the second row of a comb from the Metropolitan Museum of Art (Metropolitan Museum of Art, 30.8.224), a giraffe stands among cranes (

Figure 3), while on the second row of a flint handle (Metropolitan Museum of Art, 26.7.1281) an elephant leads a procession of lions (

Figure 4). While one could make the argument that these categorical interruptions may reflect the chaos of the wild animal world, the pervasive orderliness of the images is difficult to ignore. Perhaps, rather than representing a chaotic land, these “intrusions” are instead reflecting and embracing the diversity of animal life found outside the cultivated Nile Valley.

The larger early dynastic cosmetic palettes have images that appear less rigid, showing more of the organic and naturalistic qualities of animal depiction that might be recognized as representing the distasteful, dangerous, or so-called chaotic behaviors seen in wild animals. On one side of the

Battlefield Palette (British Museum, EA20791), birds pick at the corpses of fallen enemies while a lion devours a Nubian, whose back is dramatically curved to emulate the circular shape of the cosmetic area above him.

11However, the opposite side of the Battlefield Palette shows a more static composition, with rigid shapes and lines. Though damaged, one can see that the motif is symmetrical. A stylized tree divides the palette into two halves. On either side of the tree, long-necked creatures face the center of the object. Further to the right side of the palette, we see a depiction of a bird, which was likely featured on the opposite side as well.

A similar motif is on the reverse side of the Four Dogs Palette (Louvre, E11052). In addition to the long-necked creatures facing the tree, four dogs frame the overall palette. These dogs are also featured on the front side of this palette, which creates an overall balance to the design. If we imagine dividing this side of the palette horizontally, where an animal or a pair of animals is flanked by two identical representations of the dogs, we see that the composition is balanced. Similarly, a vertical division of the palette demonstrates a sense of stability and order as well.

The Two Dogs Palette (Ashmolean, AN1896–1908 E.3924) combines some of the organizational tactics evident in both the Battlefield Palette and the Four Dogs Palette. On both sides of this palette, for instance, two dogs frame the upper two-thirds of the entire object, like the dogs that frame the Four Dogs Palette. On the primary, or front side, of the palette, this symmetry is echoed by two additional creatures, whose long, serpentine necks wrap around the circular cosmetic area. Like the Battlefield Palette, animal forms swirl around the sides of the cosmetic area, creating a circulatory composition. The lower half on both sides of the Two Dogs Palette features irregular, organic register lines that emphasize the object’s rounded shape.

The secondary side of the Two Dogs Palette includes depictions of numerous types of animals that range from the wild to the supernatural. Their spatial arrangement is dense, and there is little negative space. The top of the palette includes two lions flanking two smaller antelopes, forming an almost heraldic composition. The placement of the antelopes mimics the depression on the other side of the palette, while the lions echo the forms of the larger dogs that frame most of the relief. Below the lions and the gazelles, the animals walk along slightly curved but invisible groundlines that conform to the overall shape of the object.

David O’Connor has identified and named two primary compositional structures in his overview of these and other early dynastic cosmetic palettes: “circulatory” and “vertically linear” (

O’Connor 2002, p. 13). He notes that linear organization is more typical on the secondary, or reverse, side, whereas “circulatory compositions” are more typical on the primary side—the side that includes the grinding area of the palette (

O’Connor 2002, p. 19). He argues that each mode of organization is directly related to the value or the meaning of each face of the object, explaining that the “circulatory” mode of organization represents the chaotic or, as he puts it, the “potentially impure, polluting, and destructive”, whereas the vertically linear compositions highlight the “divine, productive, pure, and order generating”. (

O’Connor 2002, p. 20) For O’Connor, the vertically linear composition “shields” the more chaotic “circulatory” mode (

O’Connor 2002, p. 20).

Roland Tefnin also addresses the contrast between the primary and reverse sides of early dynastic palettes, arguing that they represent an “artistic crisis” or an abrupt stylistic change. On the one hand, the artists were entrenched in the predynastic artistic tradition, which is regulated by organized rows, while moving to new forms that prefigure the future pharaonic art. Tefnin’s observations do not necessarily negate O’Connor’s, though they provide an additional explanation for why one object would have two different compositional treatments. Style, after all, exists on a spectrum, and one finds many examples of monuments and works of art that blend different styles.

However, another, more practical reason why one might find “vertically linear composition[s]” (

O’Connor 2002, p. 20) on one side of a palette and curvilinear shapes and layouts on the other is that the form and structure of these objects require both compositional layouts. The circular grinding area of one side of the palette dictates how the image around it is organized. A strict linear structure would be impossible, and the grinding area requires elements to be arranged in a looser, more organic fashion. The inclusion of the grinding area appears to show up in the late predynastic and early dynastic periods; so, perhaps the inclusion of this feature is part of the “artistic crisis” that Tefnin is referencing. Nonetheless, I think it is most likely that the two modes of representation have less to do with representing the cosmic battle between chaos and order and more to do with the design following the structure.

The Hunter’s Palette, which is preserved in two pieces at the British Museum (EA20792) and the Louvre (E.11224), is an unusual example because it is single-sided rather than double-sided. Nonetheless, for O’Connor, the representation of the dichotomy of order and chaos is preserved by combining the “circulatory” and “vertically linear” compositional modes (

O’Connor 2002, p. 18). Tefnin also acknowledges this juxtaposition, noting that the animals above the grinding area are more like a “whirlwind” or “

tourbillon”, while the animals and humans in the lower half of the palette are calmer (

Tefnin 1979, p. 225). Although Tefnin does not explicitly say so, it is implied that this juxtaposition of forms may express the concept of chaos and order. The more chaotic part of the palette includes a depiction of a lion attacking a hunter, whereas the calmer side of the palette, below the neat floating registers of animals and hunters, shows a retreating lion (

Tefnin 1979, p. 227).

At the same time, Tefnin demonstrates how the overall composition of the Hunter’s Palette is dictated by symmetrical and balanced arrangements. The hunters, for instance, are arranged on the palette according to the weapons and hunting tools they carry and are placed diagonally opposite to one another around the grinding area (

Tefnin 1979, p. 227). He also describes the palette’s balanced composition in the arrangement of “vanquished” and “living” antelopes and lions on either side of the palette (

Tefnin 1979, pp. 226–28).

12 For Tefnin, this object’s decoration effectively fills up the entire surface area of the palette, while also prefiguring the style and compositions common in pharaonic Egypt (

Tefnin 1979, p. 228).

Interestingly, the depictions of humans and animals in the Hunter’s Palette are not dissimilar, meaning that the humans are not necessarily represented as less chaotic or more orderly than the animals. In the “vertically linear” section of the palette, both the animals and the humans are walking on floating registers. Meanwhile, the humans and animals are arranged more organically on the “circulatory” side of the palette. It is unclear whether the animals are the ones who have instigated violence and disorder rather than the other way around.

The early dynastic palettes and predynastic knife handles seemed to have served ceremonial or religious functions

13 and have a shared repertoire of visual motifs, such as wild and supernatural animals and people in combat (

O’Connor 2002, p. 20;

Raffaele 2010, pp. 6–7). If the palettes illustrate the dichotomy of chaos and order in how the figures are arranged, then one would imagine finding similar visual juxtapositions on the ivory knife handles. However, this is not often the case.

The Gebel el-Arak knife is an interesting example to cite at this point because the Master of Animals motif, which is understood to communicate power and control, dominates one side of the handle (

Wilkinson 2000, p. 28). Below the Master of Animals, the animals are arranged sometimes heraldically and striding along floating registers. Perhaps one could argue that the neat arrangement one sees here and in the other predynastic and early dynastic animal compositions is a result of an ordered universe established by humankind (

Patch 2011, p. 153). Interestingly, though, the opposite side of the Gebel el-Arak knife is equally orderly in composition even though it depicts otherwise chaotic subject matter: a battle on land and at sea. While the messages conveyed on both sides of the knife handle may be about dominance and control, are they necessarily about chaos versus order?

3. Animal Iconography and the Egyptian Artistic Canon

One method that the ancient Egyptian used to maintain proportional and visual consistency in their images was the use of gridlines. Gay Robins’ scholarship has allowed Egyptologists to better understand the chronological developments of Egyptian proportional methods and stylistic changes in Egyptian art (

Robins 1994). Her studies, along with the work of Erik Iverson, however, are primarily concerned with human representation (

Iverson 1975).

Erwin Panofsky, an early 20th-century art historian and iconographer was one of the first to recognize the use of grids in ancient Egyptian animal depictions (

Panofsky 1955, p. 60). More recently, Nicole Leary has explored the use of grids in animal depictions in her research.

14 In her presentation at ARCE’s annual meeting in 2017, Leary discussed the Old and Middle Kingdom scenes of animals at Meir and developed a hypothetical grid measurement, which she then manually applied to the analysis of fifty-eight examples of standing cattle, standing and swimming ducks, and standing oryx. Her examination revealed that there were consistent body measurements across the entire test group, strongly suggesting that a proportional guide was used in the rendering of all three figure types at the site. Since 2017, she has expanded her studies to other sites, such as Beni Hasan, and has used the aid of computational measurements to more definitively show that gridlines were used, and proportional consistency was followed in the depiction of animals (

Leary 2021). While the images Leary studied are restricted to animals that are represented more hieroglyphically, her conclusions nonetheless challenge previous generalizations about the depictions of animals in Egyptian art.

Linda Evans has documented the depiction of both wild and domesticated animal behavior in wall scenes from private tombs at Giza and Saqqara, and her findings indicate that the ancient Egyptians had essentially curated their representation of animals; certain bodily positions have been repeated to the point where different animals—domestic and wild—can be grouped according to specific activities (

Evans 2010, p. 27). For instance, Evans can categorize animals according to generalized behaviors, such as “Locomotive behavior”, “Comfort behavior”, and “Sexual behavior”, and then delve into more specific behaviors, such as “galloping”, “preening” and, “chin-resting” within these larger categories. With a few exceptions, the animals in her study do not seem to deviate from the set of behaviors that she has outlined (

Evans 2010, p. 28). She also notes that some animal images may have been artistically constrained to maintain a consistent visual vocabulary. Evans cites examples where animals are depicted mating in the same way, even when the depicted posture is incorrect for a particular species (

Evans 2010, p. 158).

In the 5th Dynasty tomb of Ptahhotep, there is a detail of two leopards mating—both animals are shown standing even though it is well known that female cats do not stand during copulation but crouch upon the ground instead (

Evans 2010, p. 158). Salima Ikram also noted this inaccuracy in her discussion of animal mating motifs in Egyptian funerary representations, explaining that the artist probably did not directly observe such dangerous animals (

Ikram 1991, p. 59). Evans, however, counters this argument by citing an image from the 12th Dynasty tomb of Ukhhotep II, where a mounted male lion leans forward to bite the neck of a female that remains upright (

Evans 2010, p. 159;

Blackman 1916, Pl. 7). This particular relief may indicate that the artist had witnessed the mating bite of male lions but chose to maintain the incorrect stance of the female for “representational/artistic considerations rather than biological accuracy” (

Evans 2010, p. 159). In other words, as with human representation, the depiction of animals is rule-bound according to the ancient Egyptian artistic canon. Animals are rendered so that certain behaviors can be iconized in a specific bodily position.

4. Wild and Domestic Animals in Egyptian Tombs (Old Kingdom to New Kingdom)

One would expect domesticated animals, as creatures inhabiting the cultivated land controlled by the ancient Egyptians, to be shown striding in orderly, rigid processions. Conversely, one might expect wild animals to be depicted in more varied positions to emphasize their lack of domesticity and “carefree” nature. This visual juxtaposition of wild and domestic animals is how they are sometimes illustrated, such as in the 12th Dynasty tomb of Amenemhat at Beni Hasan (

Kanawati and Evans 2016;

Newberry 1893, Pl. XVIII).

Interestingly though, wild animals that inhabit the “dangerous”, “uncivilized” desert, are often illustrated with the same level of formality and orderliness that one would expect from the representation of domestic animals. For instance, on one wall of Metjen’s tomb, which dates to the 3rd and 4th Dynasties, wild desert animals are lined up in neat registers for Metjen to observe (

Gödecken 1976, Abb. 1). The artistic treatment of the animals is like what we see on the predynastic ivory combs and knife handles. Generally, the animals show little indication of naturalistic behaviors, except for the occasional animal that turns its head to look behind itself. Other hunting scenes from Metjen’s tomb show dogs biting down on the legs of the desert animals. However, this motif is rendered more as a hieroglyphic icon than a naturalistic depiction of a hunt, as there is no sense of violence or distress in this image at all.

Even with more organic design elements, such as floating register lines, a schematic rendering of a desert hill, and some overlapping animals, order and calmness are evident in Rahotep and Nofret’s 4th Dynasty desert landscape scene (

Petrie 1892, Pl. ix, lower). Overall, the wild, desert animals in Metjen’s and Rahotep and Nofret’s tombs are not too different from the depictions of calm processions of the domestic animals. Contrary to what some would expect, stylistically there is not much in these desert scenes that references chaos.

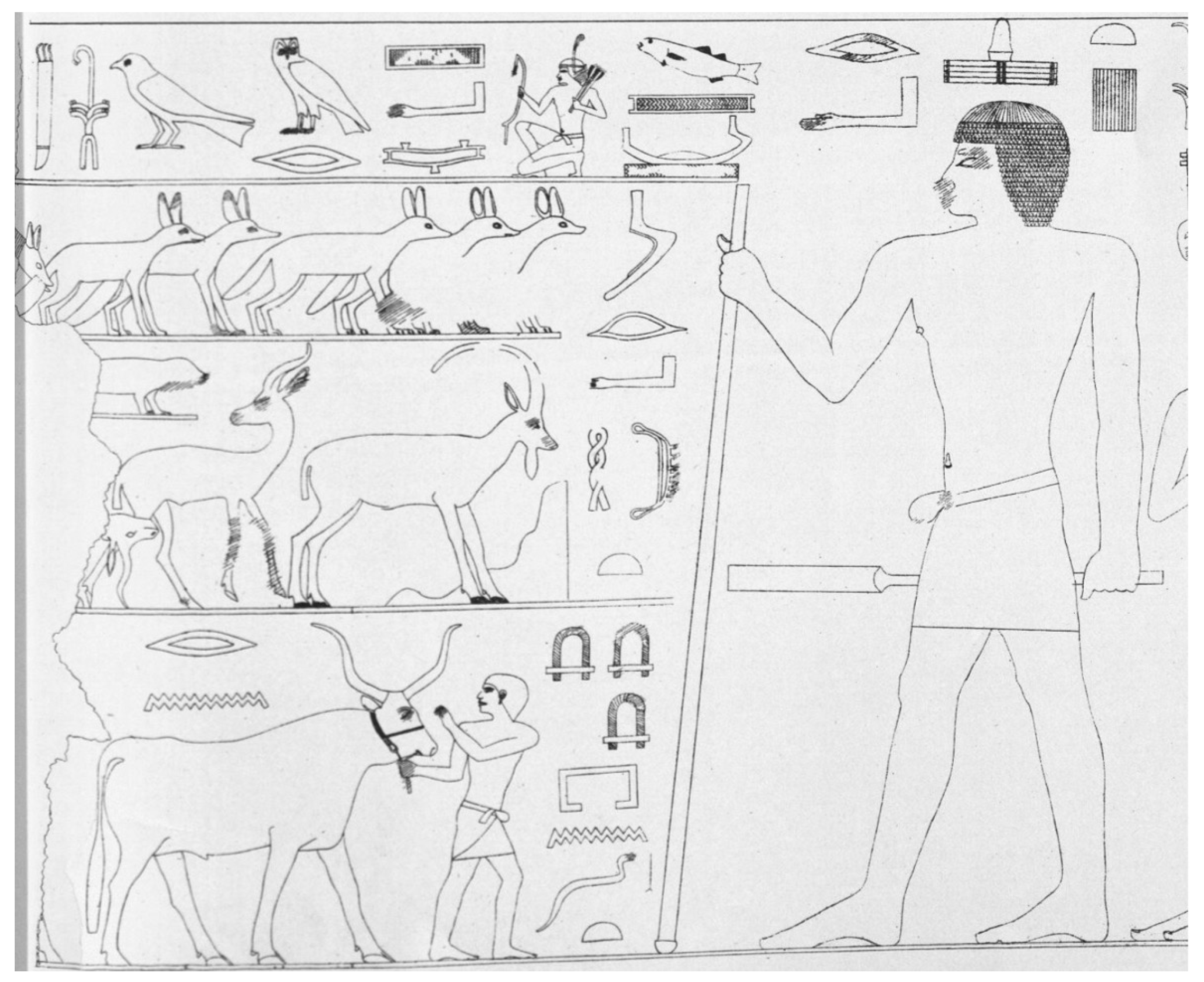

Upon close inspection, one will notice in the second register from the top of

Figure 5 that a canine is biting the tail of another canine. In the register below this one, we see a fragmented depiction of an upside-down caprid. These details disrupt the calm organized processions of animals walking toward Rahotep, which may lead one to the conclusion that stylistically and conceptually the chaotic forces are pervasive. However, it is not clear whether these representations necessarily represent a sense of chaos or instead are just a reflection of how animals naturally behave. In this example, the animals pose no threat to Rahotep, who calmly watches a domestic animal being brought before him, while the wild animals frolic in their natural environment. Perhaps this is an example of an ordered world working the way it is intended, with different animals and beings performing and behaving as they are expected.

15 While Egyptologists have assumed that order was something the Egyptians believed had to be imposed by human beings, perhaps order is instead “[…] already present by essence into every element of the world” (

Brémont 2018, p. 11).

Later dynasties of the Old Kingdom depict the desert landscape with an increased sense of naturalism and movement. Ptahhtoep’s 5th Dynasty tomb features rolling hills on top of the straight groundlines to evoke the rugged terrain of the desert. Additionally, desert flora is interspersed in the image to differentiate these scenes more clearly from the supposedly more orderly agricultural landscapes. The animals are represented with varied bodily positions, though none of the postures falls outside the categories that Evans outlined in her study (

Evans 2010, p. 27).

In both Meruruka and Ptahhtoep’s tombs, hunting dogs push down on the antelope’s rear so that their hind legs collapse, mimicking actual animal behaviors (

Evans 2010, p. 123). However, even as the dogs attack the antelopes, other animals are not shown hiding or trying to escape. Instead, some calmly stride forward, while others rest, graze, or copulate; these natural behaviors seem unnatural given what is happening around them. The variations in the animal poses and the range of animal behaviors shown may initially seem to evoke a realistic natural environment, but ultimately, they compose a generalized ideal of the desert landscape, where hunting may be abundant but where life nonetheless thrives.

The New Kingdom tomb desert scenes are rendered in a fluid, dynamic style that has been directly equated to the representation of chaos (

Davis 1989, pp. 39–40;

Groenewegen-Frankfort 1951, p. 41;

Kanawati 2001, p. 83). Abundant movement is represented in the 18th Dynasty tomb of Puyenre, with animals galloping and running away from hunters on wavy desert terrain (

Figure 6). Some animals overlap one another, giving the composition a greater sense of spontaneity that is unlike the strict registers of animals processing along firm groundlines in earlier ancient Egyptian art (

Davies 1922, Pl. 7). However, despite these seemingly organic qualities, many stylistic elements in Puyenre’s tomb invoke a sense of organization and order. For one, the animals gallop in a uniform, synchronized fashion, which is not what one would expect in an image that is depicting a hunting scene realistically. Secondly, the antelopes are arranged in a clean diagonal line, with their heads evenly spaced out within their register line. This animated yet controlled style is also seen in other tombs, such as Rekhmire’s tomb, where we see animals leaping in unison (

Davies 1943, Pl. XLIII) (

Figure 7).

In one detail from Kenamun’s 19th Dynasty tomb (

Figure 8), each animal remains still or in the act of grazing, as if unaware of Kenamun and his companion drawing his bow and arrow to the left side of the composition (

Davies 1930, Pl. XLVIII). Any sense of movement is instead evoked in the depiction of the landscape, which is essentially an uneven network of wide, pebbly strips dotted with desert flora. While the rendering of the desert space seems to evoke a confusing and perhaps chaotic landscape, it is also crucial to note that the animals in this tableau all seem to be separated into their cells or spaces; the artist has effectively categorized the desert fauna into species groups, therefore establishing a sense of order in the layout of the composition. While the artists of Kenamun’s tomb were not necessarily inspired by predynastic and early dynastic material, this kind of categorization is the same as what one finds in predynastic knife handles and combs, which sort species from register to register.

Overall, there is a greater degree of artistic freedom in the representation of animals in the New Kingdom than in the earlier dynasties of Egyptian art. While wild animals break away from the strict, regulated processions that we see in the Old Kingdom, this stylistic decision is probably not to depict the “chaos” of the animal world as some believed (

Kantor 1947, p. 63). More likely, this increased use of organic lines and the emphasis on movement is a result of Egypt’s continuous interaction with other cultures whose artistic traditions are not as strict and rigid in appearance

16 (

Feldman 2006, pp. 10–11).

The depictions of animals running and moving in the New Kingdom material are the “flying gallop” motif found in Mediterranean and Western Asian monuments and especially in luxury objects (

Feldman 2002, p. 21). Prestige goods were produced and traded throughout the Mediterranean world during the late Bronze Age especially and commonly included a shared repertoire of motifs, such as depictions of nature, wild animals, and hunt scenes (

Feldman 2002;

Feldman 2006, pp. 10–11).

Tutankhamun’s precious iron knives depict frolicking animals and plant forms that are derived from this international visual language (

Aruz 2008, p. 383). On one sheath, animals are placed one on top of the other, in a flying gallop. The animals float above a stylized palmette tree, a motif that is ambiguous in its stylistic origin but likely derived originally from ancient Western Asian ornamentation (

Feldman 2002, pp. 21–22). Furthermore, hundreds of seals from the Aegean depict hunting and predators closing in or attacking their prey, which undoubtedly traveled to Egypt and influenced the design of the larger desert tomb scenes.

Still, some may argue that the overall movement and fluidity of the animals and the wild depicted in these New Kingdom tombs is in particularly stark contrast to the rigidity used in representations of the human world, which have come to symbolize “order”. In the most formal ancient Egyptian compositions—meaning depictions of elite or royal Egyptians in tomb or temple settings, for instance—the human figure is represented with what has been described as “aspective”

17. Stylistically, this mode of representation gives images a sense of stiffness and little sense of movement, even if a person is represented engaged in an activity.

Foreigners are usually depicted with active and more varied poses. In battle scenes, foreigners are arranged in the composition dynamically, with limbs splayed out. In some cases, aspective is abandoned, and the heads of foreigners face the viewer. One might interpret this deviation from the artistic canon as contributing to the “othering” of the foreigners and the equating of them to animals, which would strengthen the argument that they are emblems of “chaos”.

As with the foreigners, the representations of low-status Egyptians, such as servants, laborers, and musicians, also occasionally abandon the formal canon of Egyptian art. In a detail of musicians and dancers from Nebamun’s tomb, two women are illustrated face-forward, while two dancing girls overlap one another and are shown with their shoulders in almost complete profile. Rekhmire’s tomb shows a serving girl with her back almost turned away, directing her buttocks toward the viewer. However, these dynamic representations of the human body emphasize the movements required of certain professions, which characterize their lower status social positions; it is doubtful that deviations from the formal artistic canon should necessarily convey “chaos” to the ancient Egyptians. Hence, style and modes of representation are not accurate indicators of what was considered good, bad, “orderly”, or “chaotic” in ancient Egypt.