Holding Our Nerves—Experiments in Dispersed Collective Silence, Waking Sleep and Autotheoretical Confession

Abstract

:1. Introduction

I think it’s really important to know that all of the so-called theory of philosophy, comes out of the urgencies felt by the human being, being alive. A lot of the liberatory theories: queer theory and feminist theory and critical race theory, they’re about … they couldn’t be more about life.—Maggie Nelson

2. Self-Reference and Performing Assimilation

[…] it is worth turning to critical understandings of whiteness (as explored by scholars such as Sara Ahmed) and also the notion of exnomination […] a word credited to Roland Barthes, literally meaning ‘outside of naming’. Barthes uses the term in ‘Myth Today’ when describing the different ways bourgeoisie (as a concept) operates in relation to ‘economic’, ‘political’ and ‘ideological’ discourses, […] in not referring to itself, the bourgeoisie and its values are (insidiously) able to become naturalised and accepted as an ideological societal norm. And this phenomenon has been echoed by writers and critics when pointing to a similar process of un-naming that occurs regarding the centrality of white-centric socio-cultural discourse in the West. […] societal standards become ideologically informed by a white perspective which mediates all subsequent human experience; whiteness becomes the standard from which all disparate meanings diverge, and “difference” and “otherness” are constructed and understood primarily in relation to white.

In 2009 I was at the end of a degree in English literature. I was writing a dissertation. It was the first time I’d felt positive about my writing. The course had so far taken away my ability to read, to absorb information, but this was slowly starting to return. In our final meeting, my dissertation supervisor asked me what marks I had been getting. My supervisor was the head of English. My supervisor was a very busy man. My supervisor was coolly interested. I told him I’d been averaging at a sixty five. But I was hopeful that I could push that to a seventy with this paper. I had been getting better. My supervisor made a note. When my bound dissertation was posted back to my family home in the summer, my dad unwrapped it. Over the phone he told me there were no pencil marks on the pages, no notes on the cover sheet, it didn’t look like it had been opened at all. The mark I received was sixty five. I’ve not read a word of it since then. This is the first time I have opened the pages …1

3. Holding Space for Silence

I allow time for daydreaming (without screens), thinking, or staring off into space. This is ‘waking sleep’, and science has shown it’s actually good for us. Just a few minutes of waking sleep will give you a huge brain boost to get through the rest of your day!

4. Extract of Episode 1 of Holding My Nerve as Transcribed by Otter.ai Grace Denton and Slacks Radio, June 2021

- 00:04

- Morning. Hi, this is Grace. So the basic aim of this show is that you and I do nothing for the next hour

- 00:31

- sounds good, right? So each week, I will be in a different space or scenario. And I’ll record for an hour. So that might be in a park, or library, any kind of public space where I’m unlikely to be disturbed, I will sit and not have anything to occupy me, like scrolling my phone, or listening to a podcast, or all of the things that I usually use as a crutch. And it would be nice if you want to join me and try and hold your nerve and do as little as possible. So the basic idea is the Our minds are very busy. And as easy at the minute for anxiety to creep in. In this capitalist, neoliberal hellscape, in which we live, feels like productivity is key. And aren’t to try and gently resist that, I guess. For myself, as well, I have ADHD, which means I have a naturally wandering mind. And I feel like I always have to have multiple things on the go.

- 03:00

- Or they’ll kind of get bored or spin out or any number of bad things. So even though doing nothing is so good for us. It’s very hard to implement. Because there’s always there’s always something we could or should or want to be doing. I recently found out through my research and interest in I don’t have a complicated interest in mindfulness and meditation. Kind of weary, weary interest in those things, because I struggle with the language and the kind of implication that we have to solve our own problems when actually the structures that we live in make that impossible. But as we do exist in these structures, and it’s incredibly difficult, even as a community to resist them. I thought this show and this idea might provide some solace are some feeling of being together or achieving something together. So I recently found out about this well, it’s a it’s a practice called waking sleep. And it’s apparently incredibly refreshing for our brains and helps us to focus and increase the kind of connections within our brain and kind of go deeper rather than existing just on this sort of anxious surface level. And in order to achieve waking sleep, you literally just do nothing you daydream and allow your thoughts to take you where you want to go. And if you have any experience with meditation, then you’ll know that the the main idea is is to kind of focus on the breath and ignore or push out any other thoughts, but I feel like that’s very difficult, and perhaps sets you up for failure because yes, focusing on the physical act of breathing can help you to slow your racing mind. But if you’re feeling guilty before you even start for myself, I know that I’ll never stop my mind from ping ponging all over the damn place

- 07:15

- so yeah, my challenge to myself every month when I do this show, will be to sit or lie in in silence with no nothing to do with my hands nothing to particularly look at except the passing world

- 07:44

- and just in an unguided way be present and to be with you all the listeners collectively, even though we’re we’re out of time and space from one another

5. ADHD, Diagnosis, and Maintaining the Garbage

6. Extract of Episode 2 of Holding My Nerve as Transcribed by Otter.ai Grace Denton and Slacks Radio, July 2021

- 51:19

- Mostly I was thinking about this thing about meditation. And I think my negative experiences of it have been when the focus has been on clearing the mind completely, and on pushing out any thoughts that drift up? And, yeah, I don’t find that particularly useful, because I don’t think I’m ever going to be able to do that. And I think a lot of people maybe feel similar. But I think I think it’s connected to the fact that a lot of Western interpretations of meditation maybe focus on discipline, and its connection to productivity and kind of optimising the self. And I think, I think going into the practice of meditation. I always feel like if I’m not getting up at dawn, and clearing my mind then I’m already failing and I think for someone who struggles with routine and

- 54:25

- just the basics of life getting up at the same time, every day is impossible for me. So enforcing a habit of something as difficult and nebulous as meditation.

- 54:50

- It’s very difficult. Um, yeah, I hope that this feels like a space that’s A little more open you know if you get distracted by something if you

- 55:10

- get bored you start looking at Instagram on your phone that’s fine

- 55:30

- I was thinking about Laurie Anderson and her ability to just put things into words that feel very much like the very human base sort of niggling emotions that we all at some time or other feel feel like tapping into the body especially then this idea of like a nerve so you know I’m holding my nerve by doing this radio show and kind of inviting you all do the same doing this thing that feels can feel so alien this sort of occupying a different part of our brain where we do nothing and

- 56:59

- explore what happens there together. But yeah, I spent when my last show was broadcast, I spent the hour feeling acute embarrassment that I was occupying the airwaves with dead air Oh, but that’s just that’s always going to be there, isn’t it? Because this is a weird idea. And blah. Yeah. So yeah, this this, this feeling of the nerve Bible7, like, was so. So connected to our nervous system. Like experiences of the world. Our responses to the world are all dictated by our nervous system. And I feel like switching off that part of my brain that’s thinking what next? What next? What next? What next? allows my nervous system maybe to relax a little bit and take the foot off the gas and respond to self instead of the urgencies? I don’t know. Yeah, thanks for staying tuned

7. Losing and Re-Finding the Self, or Enacting and Enduring the Practice of Researching

Piper was told by her peers that she should read Kant, because his philosophical writings engaged with similar ontological and epistemological questions to those that Piper was engaging with in her studio work. She decided to start reading Kant, but rather than keeping this act separate from her studio practice, she framed it as part of a conceptual artwork. The performance, […] consisted of her moving between monastically reading Kant’s Critique of Pure Reason […], scribbling in the margins as she read passages over and over, and capturing her image on a photographic film negative using a Kodak Brownie camera and a mirror.

The silence of photography becomes an apt and resonant space to stage the dissociative conditions of black life that insist on both visibility and the threat of disappearance.the fear of losing myselfShe is looking at herself and she’s looking at us. She is a body and a spirit and she’s an image. She is an image which is not a transcendent self. I imagine the time between the split seconds of these photographs and the swell of her consciousness. I imagine her interior life that can’t be photographed.

8. Extract of Episode 13 of Holding My Nerve (Figure 9)

- Transcribed by Otter.ai and partially edited to amend inaccuracies, acknowledge silence and describe incidental sound

- Grace Denton and Slacks Radio, June 2022

- 24:49

- to embrace where the mind goes and open up your thinking that way.

- 24:58

- 25:19

- so I think my piece is becoming about the elusive nature of that so called scientific theory, I need to find what research has been done into it, which has been claimed in various spots on the internet that I found, but not actually referenced

- 25:54

- cos I’m really interested in non, hmm, I’m not gonna say non medical approaches, but non medication? approaches?

- 26:23

- I recently started taking some medication for ADHD which completely changed my life

- 26:35

- felt like I was suddenly able to focus and get on with stuff that had been hanging around for years, and then I was told that it was making my heart rate too high, that I was technically tachycardic the entire time I was taking it [laughs awkwardly] so, I had to stop which is very disorienting

- 27:11

- I am interested in these interventions and kind of brain hacks that do actually help if you can remember to do them

- 27:47

- another aspect of this text I think is going to be about, about my kind of shame and self flagellation around not, not being able to just sit and

- 28:14

- read about using this this format this radio format in order to help me perform the act of researching, the auto theoretical act of not being able to read the theory that you want to read, is that, [laughs] is that a thing?

- 29:02

- so, with that I’m going to try and use this time to read. this odd context in the bath, with the recording set-up

- 29:57

- so, today in this bath I’m gonna be reading the very recent text by Lauren Fournier about auto theory. I also notice that she refers back to Chris Kraus’ I Love Dick which was a pretty key text for me in terms of accessing a [water rippling] critical, personal space. so I’ve got that here too. to refer back to. so I’m gonna leave you listening to the sounds, and I’ll come back at the end to share any thoughts or quotes

- 31:29

- [water dripping softly]

- [pages turning]

- 32:37

- [water splashes]

- 33:50

- [page turns]

- 34:02

- [water dripping]

- 36:04

- [page turns]

- 40:33

- [water rippling, bath squeaks]

- 40:43

- so, in I Love Dick Kraus uses a crush that she has developed on a philosopher to fuel, a kind of re, recapturing of her own voice in relation to theory, I think the first half of the book or a large part of the book is written as a series of letters

- 41:38

- to a semi mysterious figure called Dick, and in, in writing this text and revealing, revealing this kind of contradiction, of finding a kind of feminist voice but it being shamefully fuelled by a man who was by most accounts seemingly indifferent, she ostracised herself. so in 1997 when the book was first published, it was demonised, and then in 2016 it was it was published in the UK

- 43:14

- and a whole, a whole new generation of people were wildly celebrating this, this text that Kraus was kind of over? [laughs]

- 43:48

- this section that I’m reading and in the Fournier text is talking about how the celebration of the text in 2016 is perhaps to do with the more porous boundaries of privacy that we’re accustomed to today. Kraus’ radical blurring of art and life. So, one of the reasons why her work reverberates with millennial feminists in a post internet age of widespread disclosure

- 44:35

- another, another byproduct of this kind of radical sharing is that, in reading, in rereading her work a lot of people from our generation were turned off by the fact that she talks about making her living from property in New York State and er,

- 45:32

- I guess that’s one of the, one of the risks of transparency and shifting attitudes to how we as artists make ends meet in this fucked up world

- 46:48

- Interestingly as well the philosopher Dick Hebdidge, who the book was about but he was unnamed other than his first name, was only really widely associated with the book after he took legal action

9. Conclusions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

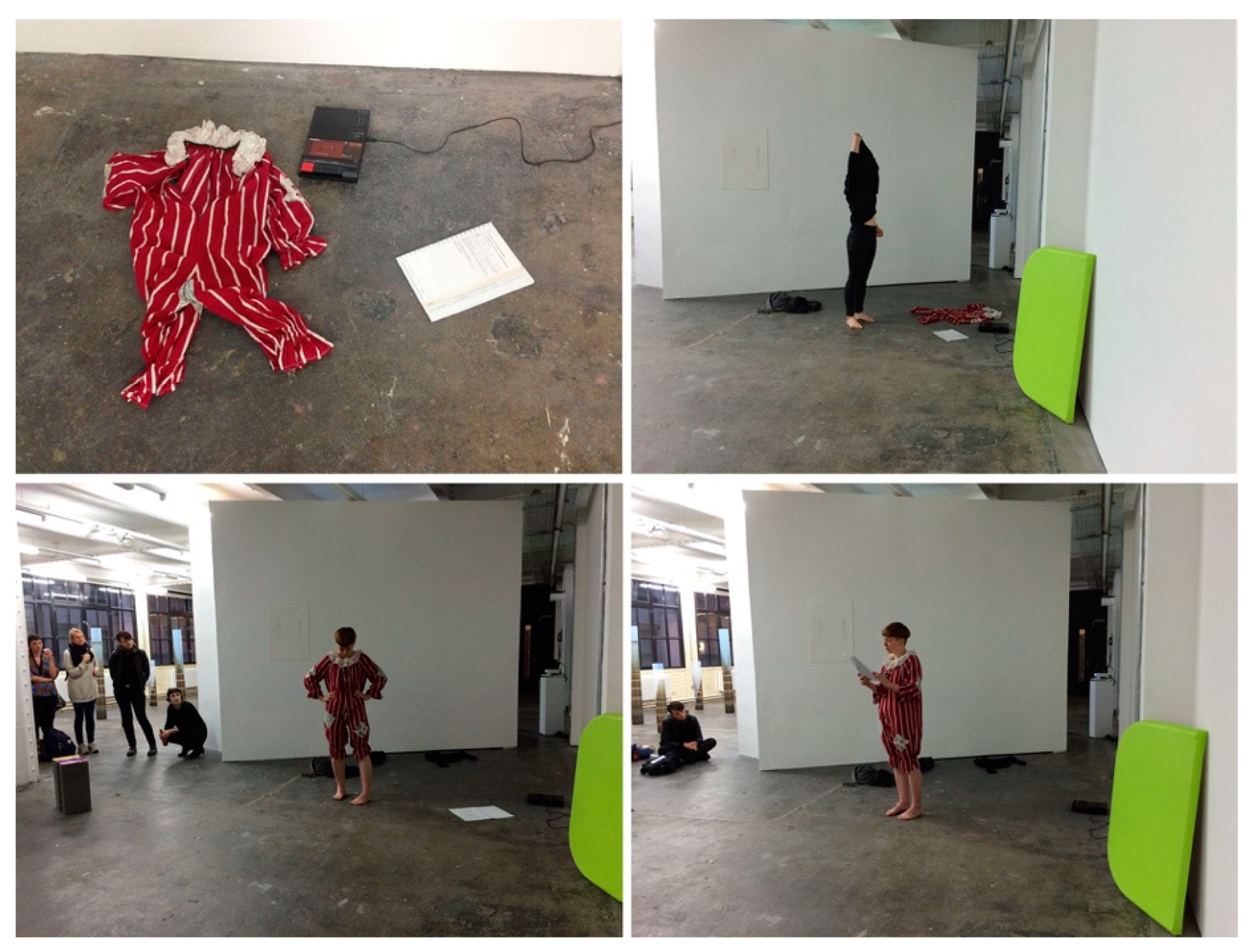

| 1 | Transcript of tape narration, Denton, Grace. Sixty Five. 2016. BALTIC 39, Newcastle upon Tyne. |

| 2 | A presentation format popular in the early 2010s in which 20 slides are visible only for 20 s each, moving the ‘storyteller’ on and keeping talks palatably brief. |

| 3 | At this point I must acknowledge the similarities between waking sleep and the practice of meditation. Thus far, my research has not progressed beyond a surface-level understanding of the deep rooted traditions of meditation, or Zen Buddhism, and this is a discrepancy I plan to rectify in further reflection, and writing on this project. In my introductions to Western translations of these Eastern principles, I have found a focus on self-discipline at odds with the neurodiverse mind. I am interested in this tension, and forging an accessible route through. The more I practice waking sleep, the closer I seem to come to the level of self-acceptance required to find solace therein. A succinct Buddhist parable no doubt exists to explain this process, but perhaps the internal barriers are greater in some than others, and we can convince ourselves we do not have the ‘correct’ capacity before we even try, making the external barriers that much harder to overcome. |

| 4 | There is a larger point to be made here, which is outside the scope of this essay, on Cage, Modernism and the obfuscation of the contribution of non-white artists and practitioners. I would point again to Craig Pollard’s thesis on the Politics of Creative Practice. Several sections of his thesis were later published in his book Inside A Gleaming Feeling (2020), designed and printed by Glasgow’s The Grass is Green in the Fields For You. The final section Kenny G and his Crew is of particular relevance here. |

| 5 | I believe the rise in the number of people seeking a diagnosis for ADHD is due to (1) a historic under-diagnosis of the inattentive form of the condition due to its characterisation within the popular imagination as the preserve of young, physically hyperactive boys, who struggle to sit still and make trouble with authority figures; (2) a rise in the distribution of information through easily digestible forms such as memes and short-form videos, for instance Tik Toks. This information boom and the subsequent rise in self-diagnosis is viewed warily by medical figures. Of course the ‘infographic industrial complex’ of social media does over-simplify complicated issues, and the desire for a quick fix for much deeper problems perhaps fuels this proliferation—nevertheless, this mode of communication is a successful tool for slipping in under the ADHD concentration limit, and meeting those suffering where they’re already seeking dopamine. |

| 6 | Jo Hauge is a neurodivergent live artist doing a practice-based PhD about neurodivergent performance practice at Northumbria. They are based in Glasgow and are currently making work about fandom/figure skating/pleasure. Together we began a weekly coworking session for neurodivergent researcher-artists, called Making Time: http://www.gracedenton.co.uk/making-time (accessed on 21 June 2022). |

| 7 | Laurie Anderson’s Stories From the Nerve Bible, a series of performances and then a book, 1972–1992. |

| 8 | In Can The Subaltern Speak? (1988) Spivak directly addresses a conversation between Michel Foucault and Giles Deleuze: From Nelson and Grossberg (1988, pp. 271–313). |

| 9 | I use the term female here as it relates directly to my personal experience, but I also use it in reference to Johanna Hedva’s Sick Woman Theory, and their definition of ‘woman’ not necessarily as female, but as feminised, i.e “those who are faced with their vulnerability and unbearable fragility, every day, and so have to fight for their experience to be not only honored, but first made visible.” (Hedva 2019, p. 8). |

References

- ADDitude. 2020. 25 Everyday Brain Boosts from Our ADHD Experts. February 24. Available online: https://www.additudemag.com/brain-boosts/ (accessed on 6 October 2021).

- Anderson, Laurie. 2021. The Road Part 4 of Norton Lectures: Spending the War without You. October 6. Available online: https://haa.fas.harvard.edu/event/mahindra-humanities-center-norton-lecture-4-road-laurie-anderson (accessed on 21 June 2022).

- Berlant, Lauren. 2011. Cruel Optimism. Durham: Duke University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Denton, Grace. 2021–2022. Holding My Nerve. Monthly on Slacks Radio. Available online: http://www.gracedenton.co.uk/#/holding-my-nerve/ (accessed on 21 June 2022).

- Fournier, Lauren. 2018. Sick Women, Sad Girls, and Selfie Theory: Autotheory as Contemporary Feminist Practice. a/b: Auto/Biography Studies 33: 643–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fournier, Lauren. 2021a. Autotheory as Feminist Practice in Art, Writing, and Criticism. Cambridge: The MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Fournier, Lauren. 2021b. The self-immolation required to be sufficiently “rigorous”. In Autotheory as Feminist Practice in Art, Writing, and Criticism. Cambridge: The MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hedva, Johanna. 2019. Sick Woman Theory. Self-Published on Their Website. Available online: https://johannahedva.com/SickWomanTheory_Hedva_2020.pdf (accessed on 21 June 2022).

- Huffer, Lynne. 2020. Respite: 12 Anthropocene Fragments. Arizona Quarterly: A Journal of American Literature, Culture, and Theory 76: 167–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamps, Toby, Steve Seid, and Jenni Sorkin. 2012. Silence. Houston: The Menil Collection. [Google Scholar]

- Larson, Laura. 2020. A Short Essay on Adrian Piper’s Food for the Spirit, Black One Shot. ASAP Journal. Available online: https://www.lauralarson.net/news/essay-on-adrian-pipers-food-for-the-spirit-on-black-one-shot (accessed on 19 June 2022).

- Maté, Gabor. 2019. Scattered Minds. London: Vermilion. [Google Scholar]

- Merriam Webster Dictionary. n.d. Definition of Self-Immolation. Available online: https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/self-immolation (accessed on 30 May 2022).

- Morgan, Grace. 2018. The Power of Silence: The Art of Marina Abramović. The Cherwell. November 19. Available online: https://cherwell.org/2018/11/19/the-power-of-silence-the-art-of-marina-abramovic/ (accessed on 6 October 2021).

- Nelson, Cary, and Lawrence Grossberg, eds. 1988. Marxism and the Interpretation of Culture. Basingstoke: Macmillan Education. [Google Scholar]

- Nelson, Maggie. 2015. Maggie Nelson: The Argonauts. Bookworm—KCRW Radio. June 6. Available online: https://www.kcrw.com/culture/shows/bookworm/maggie-nelson-the-argonauts (accessed on 21 June 2022).

- Pollard, Craig. 2018. Interjecting into Inherited Narratives: The Politics of Contemporary Music Making and Creative Practice. Newcastle upon Tyne: Newcastle University, p. 18. [Google Scholar]

- Potter, Roy Claire. 2021. Experiment Now: Contemporary Art Research Forum. Newcastle upon Tyne: Northumbria University. [Google Scholar]

- Price, Devon. 2022. My Autistic Journey into Mindfulness. Self-Published on Medium. June 1. Available online: https://devonprice.medium.com/my-autistic-journey-into-mindfulness-1cb33e4e64d0 (accessed on 21 June 2022).

- Rich, Adrienne. 1971–1972. Diving Into the Wreck: Poems 1971–1972. New York: WW Norton & Company. [Google Scholar]

- Ukeles, Mierle Laderman. 1969. Manifesto for Maintenance Art. Available online: https://queensmuseum.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/Ukeles-Manifesto-for-Maintenance-Art-1969.pdf (accessed on 21 June 2022).

- Wiegman, Robyn. 2020. Introduction: Autotheory Theory. Arizona Quarterly: A Journal of American Literature, Culture, and Theory 76: 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Denton, G. Holding Our Nerves—Experiments in Dispersed Collective Silence, Waking Sleep and Autotheoretical Confession. Arts 2022, 11, 75. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts11040075

Denton G. Holding Our Nerves—Experiments in Dispersed Collective Silence, Waking Sleep and Autotheoretical Confession. Arts. 2022; 11(4):75. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts11040075

Chicago/Turabian StyleDenton, Grace. 2022. "Holding Our Nerves—Experiments in Dispersed Collective Silence, Waking Sleep and Autotheoretical Confession" Arts 11, no. 4: 75. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts11040075

APA StyleDenton, G. (2022). Holding Our Nerves—Experiments in Dispersed Collective Silence, Waking Sleep and Autotheoretical Confession. Arts, 11(4), 75. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts11040075