1. Introduction

Lauren Fournier has contributed to the scholarly investigation of autotheory in art practice. Based on the history of philosophy and the development of theory in the West, especially in Europe and North America, what Fournier identifies as the autotheoretical turn follows the transformation of “philosophy” into “theory” and is a transformative force that is able to criticize institutional power and theoretical hegemony. Importantly, Fournier positions autotheory as a feminist practice (

Fournier 2021). A review of the development of contemporary Chinese art illustrates that there are art practices similar to “autotheory” which have different expressions from the performance of western theory’s long and particular evolution. The reason for calling the art practices “similar to” autotheory is because, as other contributors to this Special Issue also note, there is no strict definition of “autotheory”. Some regard it as “a genre in search of consensus” (

Frisina 2020). Fournier regards autotheoretical practices as interdisciplinary, trans-identified, and transmedial (

Fournier 2021). After discussing various possibilities of autotheoretical practices, Arianne Zwartjes suggested that there are “narrow and broader working definitions” when examining various projects through the lens of autotheory (

Zwartjes 2021). Whether in the field of literature or art, in correspondence with Arianne Zwartjes’ “broader working definitions”, the foundational feature of autotheory is theoretical reflection related to the self, lived experience, and individual experience. Based on Fournier’s research, this paper regards the emphasis on “self” experience and reflection on “theory” as important characteristics of autotheory and used these concepts to examine the practices similar to autotheory in Chinese contemporary art.

Arianne Zwartjes suggests that autotheory can be understood within a social context and as being situated in or connected to other academic fields (

Feldman and Sayers 2017). Through the case studies presented in this paper, we attempt to reveal some of the ways in which autotheory has operated within particular Chinese social contexts and the disciplinary trends in Chinese art. In particular, in the face of mixed cultural situations and the conflicts that can arise from such situations, autotheory provides a way to navigate contradictions and entanglements. Fournier’s research provides examples of individualist autotheoretical practices that respond to such mixed cultural situations. However, whether they are reinterpretations of historical feminist practices or contemporary examples, most of Fournier’s examples take individualist forms. That is, the “self”, in Fournier’s research, is about an individual’s experience or a reflection on this experience. From the late 1970s to the late 1980s, in the context of the end of the “Cultural Revolution” and the construction of modernity in the new era, contemporary China faced the cultural conflicts of multiple systems. As a result, collective perspectives within the fields of literature and art formed. These were creative reflections rather than a declarative expression or a manifesto and often operated in ways that can be read as autotheoretical.

Following the war of the 1930s–1940s in China and the founding of the People’s Republic of China, literature and art frequently played the role of propaganda, and there were clear limits on the content, form, and style of creation permitted within the Republic. This led to a long-term aesthetic fatigue in regard to creation. Some authors and artists reflected on this limitation through literature and art making in a covert manner, even during the Cultural Revolution, by expressing themselves in a variety of ways other than those officially sanctioned. The end of the Cultural Revolution was a major historical moment socially and culturally. In the arts, it was marked by an explosion of reflective artmaking. Moreover, if in earlier times alternative art making adopted indirect reflection strategies, the reflection practice that erupted after the Cultural Revolution was more direct in its themes and more theoretical. Underpinning this transformation from a predominantly secretive and indirect practice of reflective art making to a direct and theoretically reflective practice was a collective identification of the self with the country as a group (

Constantine and Brewer 2002). In contrast to the dominant individualism of Western culture in the same period, the group’s subjective consciousness led artists and intellectuals in China to pay special attention to the fate of the country as a collective at this historical turning point. Thus, from the late 1970s to the late 1980s, China developed collective autotheoretical practices beyond the feminist, antiracist, anticolonial, and de-colonial content that Fournier and others identify in contemporary Western art practice, providing an alternative lineage and mode of expression for autotheory. More recently, however, we can observe in the work of several artists a confluence between the feminist lineage that Fournier traces in autotheory and the collective self-reflection that characterizes earlier autotheoretical practices in Chinese art.

2. Reflection on a “Collective Self” in the Face of Mixed Culture

Fournier’s art-based examples of autotheory and most literary works of autotheory provide reflections on theoretical thinking through personal and life experience. The point that we wish to emphasize in this article is that although the experiences or thinking of the “self” are usually individualized in form and material, they also represent a certain group or identity. Current autotheoretical literary and artistic works often present the experiences of colonized, transgender, antiracist, or other marginal groups. Consequently, autotheory produces essentially “collectivist, rather than individualist, worldviews” (

Zwartjes 2021). This idea provides a prelude to understanding the “collective self”.

Based on the development and history of contemporary Chinese art, this paper argues that there exists a collective autotheoretical practice. Compared with the individual “life material” and individualized reflection commonly attributed to autotheory in the West, collective autotheoretical practice relies on collective experience, as well as the collective and communal reflection formed from this “collective material”. Brewer and Sedikides argue that the collective self is based on impersonal bonds with others derived from common identification with a group (

Constantine and Brewer 2002). From another point of view, the collective self can be understood as “the source of our common motivation, our us”, as Levi Asher said, “our concern and desire for the well-being of numerous collective groups to which we belong is a primary instinct. We care about us. Us, it turns out, is no less a strong glue than me” (

Asher 2011). In the context of China, we should also recognize the political valence of collective identity. As Wu argues, “The core value of socialism is collectivism” (

X. Wu 2012). These social, psychological, and political models provide a theoretical premise for understanding collective concerns and the occurrence of artistic practices of reflection on the collective self in China.

How does this “collective self” come into being? From the founding of the People’s Republic of China to its “reform and opening-up”, Chinese people’s work and lives were carried out in the form of collectivism.

1 Most literary and artistic creation was required to revolve around the collective national call and policy, and traditional art forms, such as “literati art”, were marginalized due to their avoidance of social reality and excessive attention to nature, such as Shanshui (Chinese landscape), plants, and personal mood. In addition to constraints on subject matter, the political culture placed strict restrictions on specific art forms and aesthetics, advocating works of realism, harmony, and classicism and works of clear and positive significance and opposing non-realistic styles, such as abstraction, cubism, or expressionism and contents that expressed negative social significance. This political influence over art production reached its peak during the “Cultural Revolution”. During the late 1970s and early 1980s, after the formal end of the Cultural Revolution, the art community “started to ‘wake up from the pain’” (

Lü 1992). In addition to the officially sanctioned style, artists were allowed to try different themes and forms of expression. Avant-garde art groups represented by the Stars art group contributed to the move away from the official style by appealing to the further freedom of artistic expression. This is understood to be the beginning of the “Chinese contemporary art” era.

2 The emphasis on common experience and memory, the care for the fate of China in the new era, and the call for national modernization resulted in a particularly strong collective concern within the art practices of this period.

Scholars and critics recorded the practices of artists within and outside the system at that time (

Cohen 1987;

Lü 1992;

Andrews and Gao 1995;

Galikowski 1998;

Gladston 2013;

DeBevoise 2014). This period has been referred to by scholars as the era of “self” discovery due to an ideological emphasis on freedom of expression in both politics and art (

Galikowski 1998). An example of this can be seen in the work of the artist Ming Zhong. In his painting “He is Himself–Sartre”, he painted a portrait of Sartre with the printmaking style (lower right of the picture) and a glass of water (upper left of the picture) on a red background. For people at that time, this work as puzzling as the thoughts of the philosopher painted within it. In response to the public’s initial misunderstanding or confusion of the artwork, Ming Zhong wrote an article, “Starting from Painting Sartre: Talking about Self-Expression in Painting”, which cited Sartre’s ideas to explain his view on the relationship between art and the “self”. Although it was out of the artist’s personal love for the philosopher that he wished to paint him, this painting and his article later triggered a discussion on the relationship between art and self-expression due to his aim of “proving one’s ‘self’ in his creative motivation and activities” (

Zhong 1981). This discussion encouraged artists’ practice of self-expression and became a theoretical basis to reflect on “collective self” in the face of the impact of mixed culture.

Many artists at this time followed their strong desire to explore various creative styles, and this, combined with the social commentary present within the artwork, was seen to be radical. The artist Yang Shang’s statement, “We must make contributions to ‘modernity’”, is representative of the common concern of intellectuals and artists at that time (

Shang 2009). This atmosphere created the conditions for the emergence of collective autotheoretical practice. During this period, works engaging with the Cultural Revolution began to appear in literature and art. An early example of this is Xinhua Lu’s short story “Scar” (

Lu 1978) and the gouache serial pictorial story “Maple” (

Chen et al. 1979), both of which became the earliest representative works of a style now known as “scar literature” and “scar art”. Later, Xiaohua Gao’s painting “Why” and Conglin Cheng’s painting “Snow on x (month) × (day), 1968” presented each artist’s reflection on and criticism of the political climate by showcasing the experiences of ordinary individuals during the Cultural Revolution. This wave of artistic reflection on collective experience enabled a questioning and rethinking of culture and became an important part of collective reflection in China in the 1980s. This reflection and subsequent nationwide “culture discussion” in the mid-1980s contributed to a rise in the consideration of “culture” within a more Western theoretical and philosophical framework in certain Chinese intellectual and artistic circles.

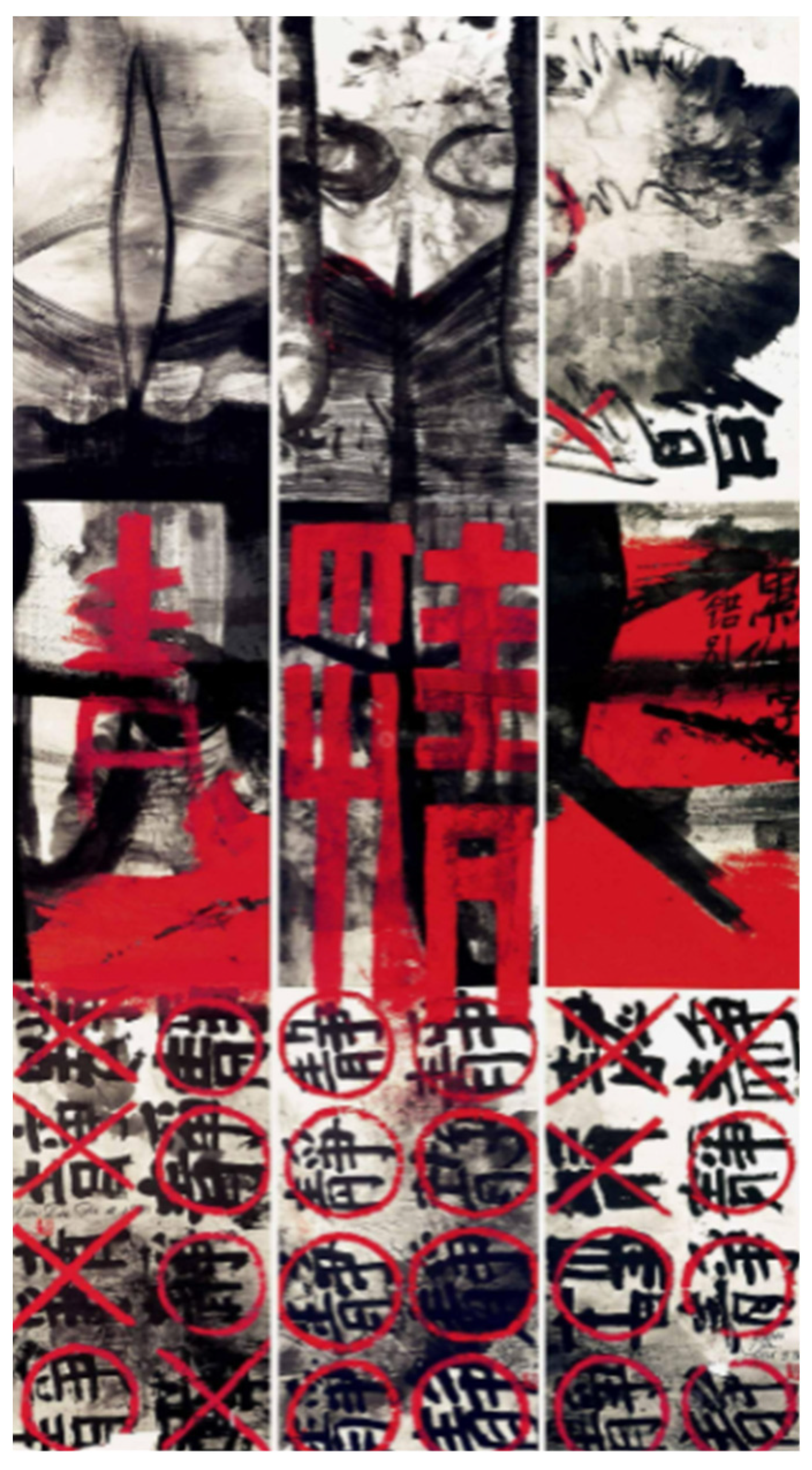

Wenda Gu’s “Drama of the Hybridization of Two Cultural Forms” is an early artwork that directly provides theoretical thinking about the collective self (

Figure 1). This artwork represents China’s traditional culture and political culture, respectively (

Long Museum 2018). At the time, political culture was the more dominant of the two, with traditional culture having been marginalized and “modified” since the founding of the People’s Republic of China. As an artist and scholar who majored in traditional Chinese painting, Wenda Gu has a deep understanding of the experience of collective cultural conflict. The spirit advocated by traditional literati art represented by ink and wash was deemed to be incompatible with the ideas of collective construction and the unity of the people advocated in the political culture after the foundation of China because of its excessive focus on personal moods and interests, especially in nature instead of social reality. As the title of Wenda Gu’s “Drama of the Hybridization of Two Cultural Forms” suggests, the work explores the tensions and assumed incompatibilities between traditional and “modern” Chinese art by gradually covering and “correcting” the traditional medium with red symbols to represent the dominance of the political culture, suggesting a certain suppression of the traditional by the political. Traditional Chinese literati art aesthetics were transformed by the politics of the Cultural Revolution, resulting in specific requirements of form and theme. The drama and absurdity of this treatment of traditional culture and historical legacy, especially during the Cultural Revolution, are revealed in this image. In addition to this political and social commentary, Gu provides suggestions about how to resolve the conflict between political and traditional ideologies by showing the continuation and inevitable “modernization” of traditional culture, juxtaposed with political culture. The traditional ink painting at the top of the image has been “modernized”, suggesting that the literati spirit is no longer suitable for that contemporary culture; thus, it is necessary to carry out self-transformation. This is consistent with Gu’s view on modernity. Minglu Gao called Gu’s works typical “scholar painting” (

Gao 1986), in as much as they embody a theoretical and academic processing of ideas into art. In his early days, Gu was both a researcher and an artist, and he hoped to convey his thinking and research through artworks (

Art China 2016). Wenda Gu’s academic methods shares characteristics with autotheory by emphasizing the theoretical possibility of reflection on the collective self.

Collective self-reflection is not only present in retrospection and criticism. From the late 1970s to the late 1980s, the conflict between different cultures came into focus. Due to implementation of the reform and opening-up policy, China has gradually restored its ties with the rest of the world. Western culture has continued to flow into China and continues to have a great impact. Coupled with the tension between the socialist political culture and the traditional culture that existed in China for thousands of years, more complex cultural conflicts began to appear. In China, a variety of binary oppositions, such as the West and the East, or traditional and modern, have become sources for collective reconsideration about China’s cultural identity. Western art theories and practices were brought back to China by artists or scholars studying abroad in the early twentieth century, with the purpose of better exploring the fullest possibilities of art by learning different technologies. In some instances, western practices were adopted as ways to transform the performance of Chinese painting techniques or to integrate the two, but the overall goal was to learn from their differences. This goal ensured that there were few psychological conflicts or points of resistance in the study of western art. However, when western art theory and practice entered China again after the end of the 1970s, its reception was more critical due to the history of ideological criticism it had received under the long-term influence of the socialist political culture. In the efforts to construct modern Chinese culture, the question of how to deal with this mixed theoretical framework became a collective challenge in the 1980s. The tension brought about by these internal and external influences in the 1980s erupted into a nationwide “Cultural Discussion” between 1984 and 1985. Within this wider discussion, artists expressed their different positions through their art practices, forming the vigorous ‘85 New Wave Art Movement’.

An example from this movement is the performance artwork known as “

The History of Chinese Painting and

The Brief History of Western Modern Art Washed in the Washing Machine for Two Minutes” by the artist Yongping Huang. Within the context of conflicting positions regarding the cultural choices faced by art circles (and wider society) at that time, the artist placed books representing Chinese traditional culture and Western culture in a washing machine for two minutes (

Figure 2). The literal and conceptual “mixing” of the two cultures, as represented by the books, mirrored the situation faced by Chinese intellectuals at that time. The cleaning enacted by the washing machine represents the possibilities presented by combining, analyzing, discussing, and attempting the purification of the Chinese and Western cultures (both traditional and modern), as well as the intention to clarify them. The artwork takes the final form of a cleaned residue, a mass of paste in a moist state, which suggests that the washing machine can be regarded as a digestive organ, and the result of this cultural collision is shown as “digestion” or “indigestion” (

Fei 2022).

Although the cases discussed here do not clearly “cite” any specific existing theories, what they reflect resonates with those ideas discussed in post-colonial theory and cultural studies. In the context of China in the 1980s, this collective autotheory mostly involved the artistic representation of “non-western modernity” and approaches that highlight choice, resistance, transformation, and juxtaposition in cultural conflict (

Bill et al. 2002), or grafting and hybridization (

Young 2004), presenting a picture of postmodern cultural theory in the context of non-Western culture. This practice, based on the reflection on the collective self in the 1980s, contributed to the theorizing of cultural research in fine art. In addition, it is worth mentioning that in this example of collective-self rethinking, the “self” disclosed and narrated in autotheoretical practices is not aimed towards “non-self” factors. In Fournier’s example, these “non-self” factors are colonists, racial discriminators, and other power subjects. Autotheory thus becomes a criticism of “non-self” factors. In Chinese art, by contrast, this rethinking on the collective self reflects collective self-experience and a practice whose essence is anti-self and constructive.

3. The “Self” Evaluation of Women Artists in Contemporary Chinese Art

Fournier states that, as a contemporary art practice, autotheory is “attuned to its long-standing ties in feminist practices across media and form” (

Fournier 2021). Within the wider set of contemporary Chinese women artists whose practices are underpinned by feminist social and theoretical concerns, there are some cases that can also be considered autotheoretical. As far as the situation following the 1980s, as discussed in this paper, is concerned, the influence of Chinese women artists was established at a time when the focus of Chinese contemporary art turned to a more individualized consciousness in the 1990s. Changes in the social environment and artistic ecology have attracted scholarly attention to women (in art and other areas) in the new era. Autotheoretical modes have been adopted to explore the connections between China’s traditional gender and family concepts and the contemporary social changes of “modernity”, and to unpack the impacts of social changes on women’s lives in contemporary China.

The combination of autobiographical and theoretical reflection is often considered a basic characteristic of autotheory. The works of the artist Yu Cao can be regarded as a typical critical autobiography but can also be considered autotheoretical. Compared with literary examples of autotheory, such as

The Argonauts and

I love Dick, Yu Cao’s autotheory exists in a variety of cross-media forms, but she take her “self” as a site of theoretical investigation. In 2017, her first solo exhibition, “I Have an Hourglass Waist”, included photography, video, painting, sculpture, installation, and performance, amongst other forms. The artist’s reflection on life, identity, and attitude are present in this exhibition, as they are in “I Have” (

Figure 3), “Confused Romance”, “Flesh Flavor”, “Living, nothing to Explain”, “Female Artist”, and “The Artist is Here”. Taken together with her previous works, audiences can see in her oeuvre the characteristics of her autobiography. Many of her works are inspired by her own experience, ranging from the girl’s identity she realized to her learning, marriage, childbirth, and other experiences. For example, her work “Spring”, presented at her master’s graduation exhibition, used videography to depict breast-swelling-related pain during lactation and the squeezing of the milk with her hands and its ejection. “It made me feel the changes of my body as a mother and the great inner power of connotation” (

Cao 2021).

The video work “I have” is a practice of autotheory, which reflects theoretically on women’s self-evaluation. If, following Rosalind Krauss, we understand self-referential video works as embodying a form of narcissism (

Krauss 1976), Yu Cao’s video deploys that narcissism as the strategy that makes her autotheoretical practice possible. In the video, a kind of visual “I” is highlighted. In the surrounding darkness, the “center” only has the “I” image that contrasts with the darkness. In the video, Yu Cao, the artist and protagonist, repeats an excerpt of the content. The artist speaks, with a serious face, words designed to arouse universal envy:

I had a wonderful childhood;

I have an intelligent mind;

I have an innate artistic talent;

I have the admission notice from the Central Academy of Fine Arts;

I have a bachelor’s degree and a master’s degree from the Central Academy of Fine Arts;

I have an hourglass waist,

Additionally, long legs;

I have a happy and wonderful marriage;

I have a Beijing hukou (registered residence);

I have a great cooperative gallery;

I have five properties in and around Beijing;

I also have a very large studio in Beijing;

I have participated and will participate in more heavyweight-level exhibitions;

I will have my resume at the Kassel Documenta and the Venice Biennale;

I will be one of the most representative artists in China…

The work’s double focus on the self and her narcissistic discourse with “I” as the subject in the video have a multiplying effect. The script reflects a reality that the audience can grasp, and someone slightly familiar with her curriculum vitae will recognize the authenticity of it. There is some information, however, whose authenticity the audience cannot judge. The autobiographical formulation does not guarantee authenticity, which, as Fournier explains, is not the focus of autotheory. Any sentence within this excerpt could be the condition under which an individual, especially a woman, is judged on her appearance, life, occupation, and identity, within the values of contemporary Chinese and Western culture. This 4′19″ vignette is displayed on continuous loop, so that the viewer hears the “standards” or “conditions” of real-world individual evaluation ubiquitously distributed, regardless of the point at which they encounter this work in its cycle.

“I have” makes visible the (often gendered) evaluation of the self: the examination of the self’s status quo, the contrast of some sort of social public evaluative indicator, and the attitude of the self toward psychological satisfaction and anticipation about the future. These features convey the experience of contemporary women’s self-evaluation through the presentation of the author’s autobiographical content. Yu Cao uses imitation and irony to remind people to reflect on the significance of this evaluation of the self. Indeed, the work can be read as a kind of satire of the pervasively “successful” or “perfect” anxiety disorder in contemporary society. Many social platforms and social media, replete with the shaping of “perfect” standards for women’s bodies, such as “the hourglass waist” or “the long legs”, create and traffic the anxiety that emerges from this evaluation of the self. Educational background, property, occupation, and friend sourcing have also become indexes of success within the context of increasing competition, which is, in China, called “involution”.

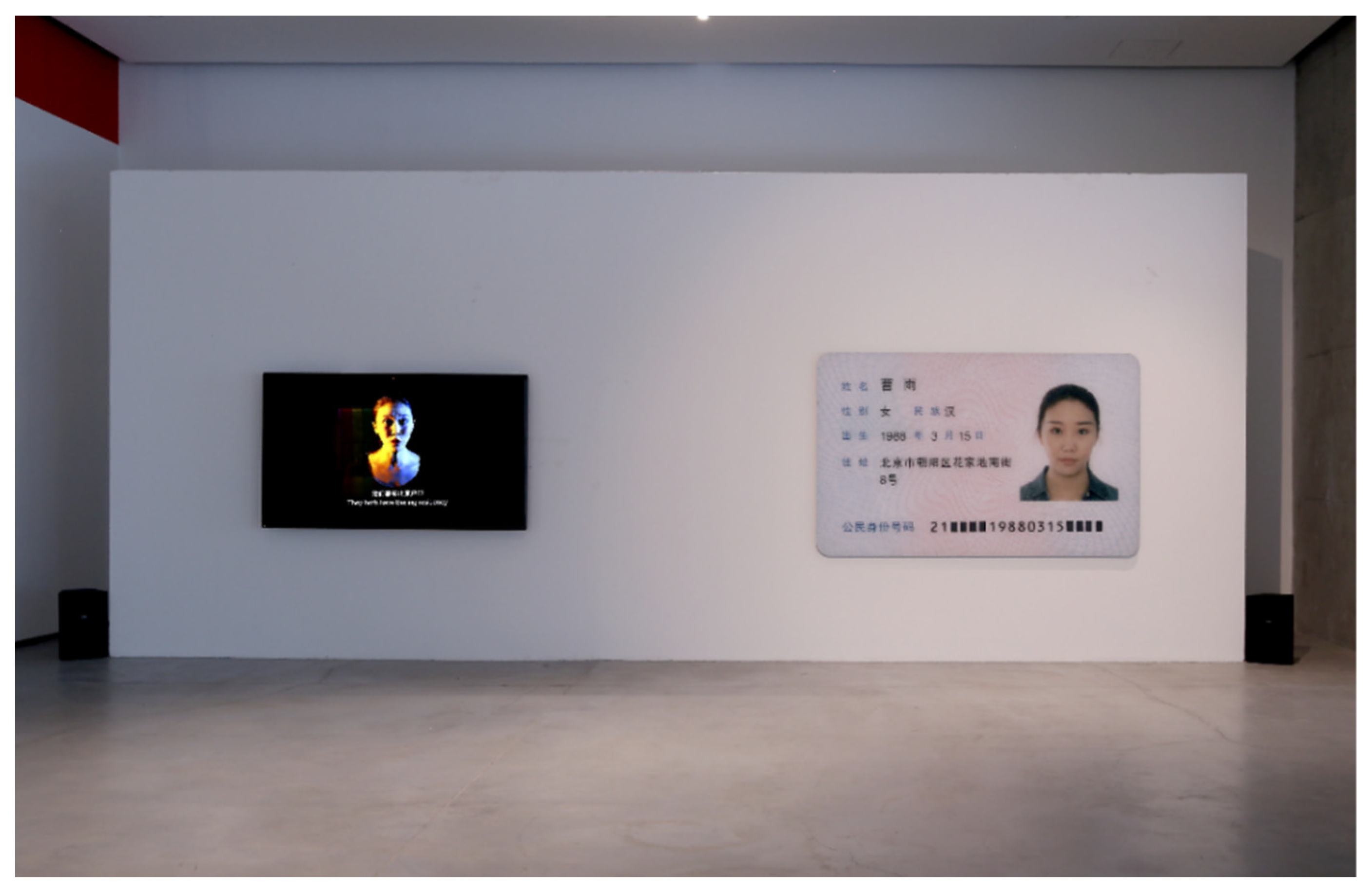

What are the answers to this self-evaluation anxiety for Yu Cao? Her other works imply her theoretical thinking and, as in the case of “I have”, express this thinking through her “self” as a site of theoretical investigation. On the opening day of her solo exhibition, Yu Cao, being 8 months pregnant, drew a circle by hand on the ground with chalk and stood quietly inside the circle for two hours, turning the artist’s self “hidden” under the eyes of sentience into a living sculpture, while leaving the audience to form their own judgements. On a wall next to her hung the artist’s enlarged ID card, namely “Female Artist”, which presented the natural gender attributes of the artist. In this way, she emphasizes a subjective existence that circumvents judgments regarding identity, gender, and profession and tacitly accepts the multiple identities of the self’s natural gender, profession, family, and so on, instead. Works such as “Living. There is Nothing to Explain” and “90 °C” show contemporary women’s attitudes to survival under the condition of straightforwardly accepting multiple identity traits, fearless of secular judgment conditions and realistic stress, through a clear awareness of the “self”, positively realizing their self-worth. These works, which are based on the self of the author, resonate intrinsically with “I Have” and are followed by a woman’s affirmation of her power as a female, maternal, artistic “self”.

4. Art Practice Interacting with “Theory”

Fournier examines citation as a method commonly used in autotheory that often appears as “performing citations and visualizing references” in art practice, as a way of rethinking and developing existing theories. The cited theory or other cited text forms an intertextual point of reference from the author’s perspective, illuminating the author’s autotheoretical intentions and orientations in different art materials. Two issues emerge from Fournier’s examination of citation as an autotheoretical practice: the question of what is commonly cited and the question of what is to be derived from autotheoretical practices. Must the references be “theories”? Must the practical results of autotheory produce some kind of “theory”?

Monica B. Pearl analyzes the citations of Maggie Nelson’s

The Argonauts, arguing that while they “engag[e] the words and ideas of myriad others including acquaintances, friends, experts outside the realm of scholarly thought, poets, even her partner”, they do not have “a point: no overarching claim that is being pushed and proved” (

Pearl 2018).

The Argonauts gives one example of autotheoretical citation. In addition to literary citations, similar to those used in academic writing for referential purposes, there tend to be various types of “premise” or epigraphical quotation at the beginning of autotheoretical writing. Does this kind of textual reference also have an autotheoretical importance or impact? Arianne Zwartjes, in another context, points to the extensiveness of “theory”, “as ways of defining and explaining our experience to ourselves”, affirming the larger scope and more flexible content of “theory”. This capacious understanding of “theory” corresponds with the context of China. In China, “theory”, in its Western sense, is a relatively modern concept that has emerged since the 1980s. Nonetheless, traditional theories and perspectives remain latent in apparently non-theoretical genres of texts, such as history, poetry, or commentary. Thus, these texts can also be regarded as “theories” that invite and provide opportunities for intertextual citation in autotheoretical practice.

Unlike Yu Cao’s practice of using her “self” as a site of theoretical investigation, the artist Wei Peng (also translated as Peng Wei) communicates with different historical texts in her works. Peng’s exhibition in 2019, entitled “Feminine Space: Peng Wei”, is a typical case. “Handbook for the Boudoir”, “Old Tales Retold”, “The One in My Dreams”, and other works in the exhibition directly or indirectly cite traditional Chinese theories about femininity, while other works are related to female texts in different cultures. “Old Tales Retold”, for example, interacts with the cultural history of the “Lie women” (

Figure 4). Since ancient times, China has had a guiding theory of women’s morality, ethics, qualities, and other aspects. “Lie women” is a historical collection of representative stories about women, selected by ancient scholars or authors to reflect the values of morality, benevolence, wisdom, courage, sagacity, and motherhood traditionally attributed to women. While the collection has had stories added and deleted in different dynasties, creating different emphases over time, its purpose remains to be to educate women, exhorting them to uphold the values it celebrates. Wei Peng’s “Handbook for the Boudoir” responds citationally to a “Bible of women’s virtue” written by Lü Kun in the Ming dynasty, which outlines the attributes of a daughter, a wife, and a mother that it wishes to celebrate, in line with the Lie women tradition (

Figure 5). These women, however, shocked the artist: they are ferocious, seek revenge with a knife, self-mutilate, and express sadness, a picture which is very different from the female images in other traditional works. Peng’s response to this “Lie women” theory has two aspects. It prompts a rethinking about the independence of women’s subjectivity today and the resistance to expectations of suppressing the “self” through self-sacrifice and service to men.

Peng skillfully uses the technique of “citation” to convey this reflection. She directly quotes Lü Kun’s

Handbook for the Boudoir in the title of her work, signaling the relationship between the two. In addition, she selects several typical images from Lü Kun’s

Handbook for the Boudoir and enlarges and transforms them into a continuous female image to create an alternative book of images of women. As Wu Hung argues, Peng Wei extracts these images of women from their original context, where they were depicted as hurting themselves for loyalty, filial piety, and righteousness, and amplifies them to create independent individuals who are larger than life (

H. Wu 2020). These magnified images and their composition on the page become visual references. This method of citation not only makes people alert to and invites criticism of the unjustified expectations of women but also reflects on how the traditions exemplified in the

Handbook for the Boudoir continue today. Although, in the process of opposing the feudal customs of dynastic China, the women’s liberation movement has raised the status of women in China, there remains an implicit constraint on women’s virtue at the social level. With the revival of traditional culture in the new century, the deformation of the “boudoir models” or Lie women has emerged in the new era through phenomena such as “female virtue training classes”, which impose a layer of moral constraint on women who have not truly been respected as independent individuals. By her citational practice, Wei Peng shows clear critical attitude towards the distorting “boudoir models” set up through the invocation of the “Lie women” tradition.

Interestingly, in 2022, an academic article entitled “Lie Women Do Not Hate” echoed the questions raised in Wei Peng’s works. In the article, Feng Peng, an art critic, studies the reasons why most figures among the Lie women expressed anger and hatred in both their textual and their visual representations (

Peng 2022). Whether the latter research is inspired by Wei Peng’s exhibition or not, it shows how Wei Peng’s art responds to a larger ideological problem and does so through a visually citational and autotheoretical practice.

The formation of a dialogue with “theory” is a common practice in autotheory. However, even if the practice of autotheory is a living, emotional, and personal creative “genre”, dialogue with existing texts or a certain “citation” does not automatically make an artwork autotheoretical. This problem is also one of the difficulties involved in judging the practice of autotheory. The series known as “The One in My Dreams” is an exchange of writing generated by a conversation with Judith T. Zeitlin (

Figure 6). The female characters she chose are mostly from

Strange Tales from a Chinese Studio by Songling Pu. Each picture is accompanied by a letter from a Western female writer translated by Wei Peng into Chinese. The juxtaposition of the two forms a contemporary view of women (

Figure 7). For example, the female image shown in the picture is Xiaoxiao Su, a talented Geisha from the ancient south of the Yangtze River. The text is a letter from the poet Anna Akhmatova to her brother-in-law. The two women’s experiences and their talented characters frame the sincere language of the letter in relation to the image. Peng Wei’s exhibition thus uses various citational modes to connect women from different cultures and historical moments to explore contemporary women’s experiences.

This kind of “dialogue” or communication is interesting, but is it a practice of autotheory? It cannot be recognized as autotheory solely because of its citation and its intertextual practice. At the same time, it also cannot be judged as non-autotheoretical simply because the work does not interact with existing critical theory. This uncertainty puts pressure on the understandable or identifiable scope of autotheory in art practice and underlines the caveat expressed by Fournier and others that autotheory only occurs in certain fields (

Fournier 2021), especially when its expression is not narrative. Fournier’s examples of autotheory are frequently drawn from contemporary video or performance art, for example. These artforms are frequently narrative in nature, producing a linear expression of time, and this characteristic provides a point of commonality with textual autotheory. However, in other forms of art practice, especially in those contemporary art forms underpinned by “concept first” awareness, the question of how to distinguish a theoretical contribution from autotheory remains to be considered.