Abstract

The Bedouin and Jewish inhabitants of the southern Israeli desert region share a common desert vista. However, they are diverse, multicultural communities who suffer inequity in access to valuable resources such as water. Between 2019 and 2021, Common Views art collective initiated a socially engaged durational art project with Bedouin and Jewish inhabitants entitled Common Views. The art collective seeks to enact sustainable practices of water preservation as a mutually fertile ground for collaboration between the conflicted communities, by reawakening and revitalizing rainwater harvesting, as part of traditional local desert life. Their interventions promote new concepts of Environmental Reconciliation, aiming to confront social-ecological issues, the commons, and resource equity, grounded in interpersonal collaborative relationships with stratified local communities. Their site-specific art actions seek to drive a public discourse on environmental and sustainable resources, while reflecting on the distribution of social and spatial imbalance. They take part in contemporary art discourse relative to socially engaged practices, yet their uniqueness lies in conflictual sites such as the discord arising from the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, and their proposed model for resolution linking politics with environment. It utilizes renegotiation with histories and heritage, as a vehicle to evoke enhanced awareness of mutual environmental concerns in an attempt at reconciliation on political grounds.

1. Introduction

“And today who will linger, who will awaken the dead and heal the fissures? For this mission, we need more than New Historians. For this mission, we need, as always, artists.”(Larry Abramson)1

The Common Views art collective, led by artists David Behar Perahia and Dan Farberoff, has been involved since 2019 in an on-going socially engaged durational art project, grounded in interpersonal collaborative relationships with stratified local communities worldwide. Their projects evolve through engaging with inhabitants of various communities at given locations, establishing an active public participation during various stages of the making. Their artistic toolbox contains site-specific, socially engaged art and participatory strategies in collaboration with local creative agents and with the local inhabitants of each of the intervening surroundings. These surroundings, characterized by means of environment, habitation, and social status, serve to inspire consistently novel activities. The place is treated as a tangible site by means of spatial, environmental and planning strategies and as an intangible site, belonging to local communities, their histories, traditions and memories, both individually and collectively.

The artistic strategies are part of the international contemporary genre of socially engaged art and participatory interventions, dealing with the notion of identity from a spatial perspective and touching upon political and civic issues. These practices broaden the artistic toolbox to include a collaborative dimension of social experience outside traditional institutions, to involve forms of engagement with social groups of both art and non-art communities, in the creative process. West Coast scholars distinguish them as an art genre of collectives that through joint continuous site-specific works, propose alternative models for social activity. Dismissal of art as an object, and its progression toward cooperative spatial intervention, release the artistic creative process from individual authorship, steering it to collective production. Artists who adopt strategies of social involvement seek to contribute to society where other social agents have failed, using their unique cultural capital (Bishop 2006; Atkins et al. 2008).

Although Common Views adheres to a participatory agenda, their uniqueness lies in an interdisciplinary dialogue revolving around social and environmental concerns. The collective promotes a new concept, Environmental Reconciliation, which juxtaposes the environmental, the civic and the political. They use art engagement as a critical creative tool to reflect on social-ecological systems, the post-anthropocentric idea of the commons, and natural resource equity. Their aim is to drive a public discourse on sustainable resources in the context of climate change and the growing global water crisis which have pushed the need for preserving time-honored approaches and the creative use of resources to the fore.

The environmental aspect of their artistic work is carried out at conflictual sites, interwoven with civic issues of identity, land and the accessibility to resources. Through this discussion they are able to reflect on a distributive imbalance of social and spatial injustice. By reviving ancient local traditions, they seek the reimagination and reconstruction of the inhabitants’ traditional knowledge for contemporary needs. The concept of Environmental Reconciliation offers a creative mode of operation intertwining the past, the local histories, collective memory, and heritage preservation. It aims to use environmentally oriented activity as a civic tool to promote a positive dialogue between contested communities.

The Common Views art collective was formed in 2019 in the course of work within the Israeli desert town of Arad and the adjoining Bedouin settlements. Their mutual activity became the first intervention of an on-going durational nature. The titles given these projects consist of Common Views, the collective name, and the main research themes they are engaged in worldwide. These include the following projects: Common Views: Sourcing Water (November 2019–June 2020); Common Views: Gemeinsame Sichtweisen, Schorfheide-Chorin Biosphere Reserve & Spreewald Biosphere Reserve (November 2020–September 2021); Common Views: Verkörperte Sichtweisen Performance, Grumsin forest UNESCO world heritage site 10th anniversary, Schorfheide-Chorin Biosphere Reserve (June 2021); Common Views: Tent of Assembly, Kumzits Art Festival, JCF, the old Jewish quarter of Kazimiers, Krakow, Poland (June 2021); Common Views: ARCHA, Spreewald, Germany (May–September 2021); Common Views: The Water Way, Kuseife, Israel, (November 2021); Common Views: A Cup of Water for the Messiah, Open House Festival, Abu-Tor, Jerusalem, Israel (November 2021); Common Views: Presentation, in the Commoning Curatorial & Artistic Education CAMP Notes on Education Summer School, DOCUMENTA fifteen, Kassel, Germany (June 2022); Common Views: Biosphäre Berlin | Berlin Biosphere, Germany (September 2022–February 2023).

Dr. David Behar Perahia is a French-born Israeli academic researcher and artist situated in Italy and Israel. His research, based on various fields of practice such as geology, material chemistry and architecture, propelled him to a site-specific approach. Through research-based art interventions, he aims to explore the layers that compose a local context, and to establish a strong sense of place in order to convey a new perspective on locality. He employs the use of mixed media, exploiting materials found locally, and inspired by his encounters with the locale, and his works are exhibited worldwide. Dan Farberoff is a multinational, interdisciplinary multimedia artist, director and filmmaker based in Berlin. He is a movement practitioner, at times involved with teaching Yoga and meditation as well. His work is primarily focused on mediated physical and digital presence in nature and urban site-specific environments. He incorporates new media, video, photography, interactive technology, live presence, and dance in his works on various multidisciplinary projects, events, festivals and shows worldwide. Some of these are large-scale works, presented before large audiences at major venues.

The article pinpoints strategies used by Common Views art collective in the “Negev” desert region of southern Israel through a collaboration with the local commons that inhabit this region, the Bedouin community, and the Jewish community. While sharing a common desert vista, these are diverse, multicultural communities which suffer inequity in access to valuable resources. (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

The “Negev” Desert Vista, Israel, 2019. On the left, the road between the cities of Arad and Massadah which runs through the Bedouin settlements of Al Baqi’a valley. Photographed by Dan Farberoff. Image courtesy of the artist.

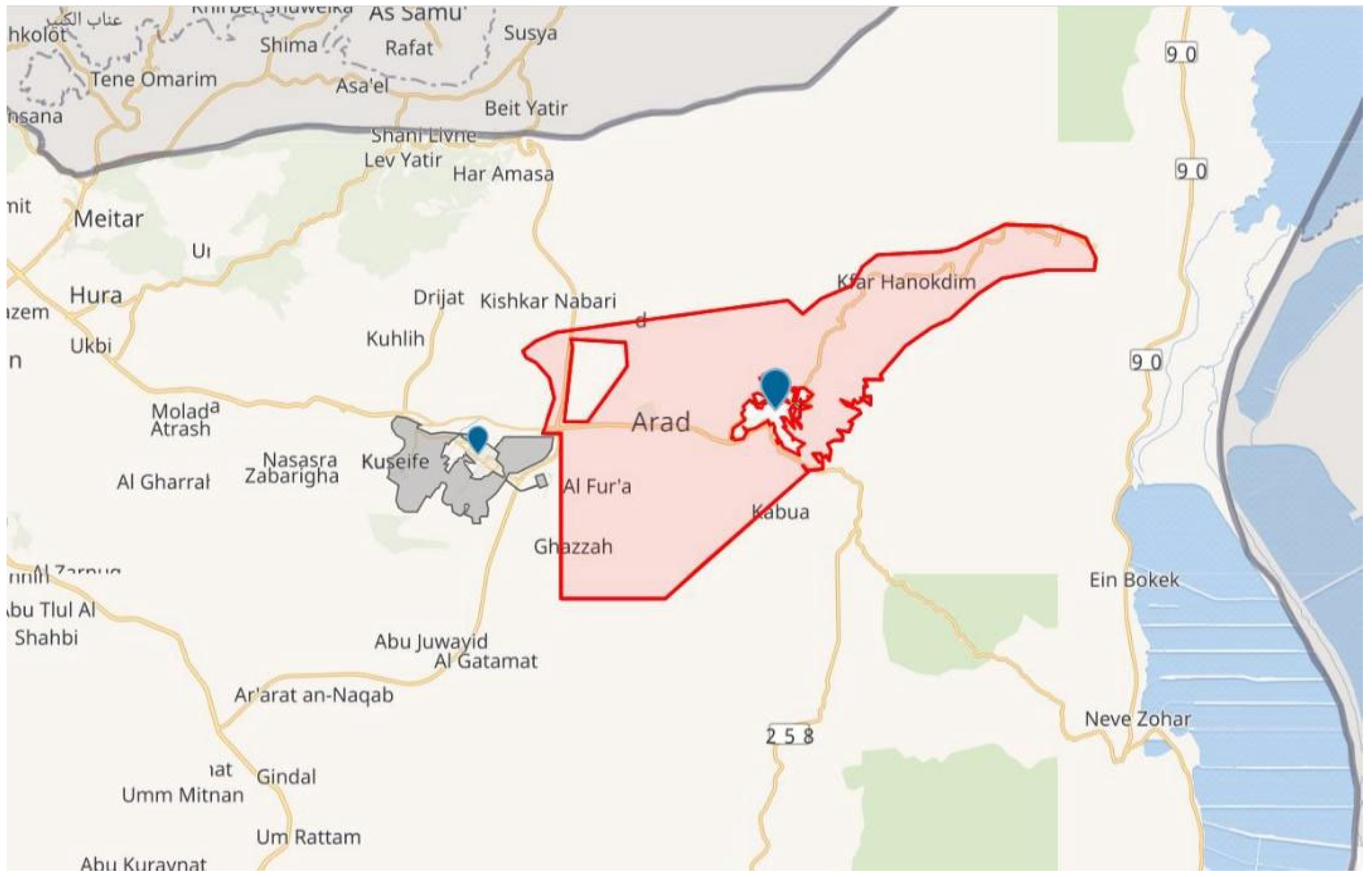

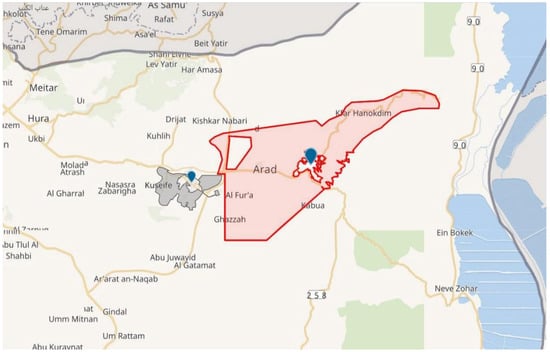

The article examines the Common Views project through two art interventions performed in the same desert environment and located in close proximity. The first—Common Views: Sourcing Water (2019–2020)—took place in the Bedouin settlements of Al Baqi’a valley and the adjacent Jewish town of Arad. The second—Common Views: The Water Way (2021)—took place in the Bedouin town of Kuseife (Figure 2). Both interventions reflect a conflictual area, both take place in the desert, and both pertain to the theme of water. The first is a long-term project which involves a Jewish city and unrecognized Bedouin settlements, and deals with the collaborative reconstruction of water cisterns, while the second involves a Bedouin city, its elders, schoolchildren, and various environmental and educational agencies, and deals with water harvesting. The second operation is in part, an extension of the first, despite the several-months-long gap, during which a sculptural product from the first intervention was applied to create another new sculpture, in the second intervention.2

Figure 2.

Map of the southern Israeli “Negev” desert region. Marked are the settlement of Al Baqi’a valley and the city of Arad (red) and the Bedouin town of Kuseife (gray). Source: Wikimedia Israel maps, OpenStreetMap®.

The artists have chosen to focus on water as the most precious resource in the desert region, to reflect on a distributive imbalance between Jewish and Bedouin inhabitants regarding water use and supply. Traditions of the desert practiced by the Bedouin who live there today have been practiced in the past not only by the Bedouin desert dwellers, but by the ancient Hebrews who were desert dwellers themselves. In fact, all inhabitants of the desert used these methods, which the artists are working to revive. They collaborated with local commons and their representatives to revitalize and awaken an interest in the local heritage of the desert tradition of rainwater harvesting, and to enact sustainable practices as a mutually fertile ground for both communities. These actions serve to trigger conversation and public discourse, to provide a possible sustainable future for this desert habitation, and to suggest a solution for future collaboration on mutual grounds.

Within my conceptual framework, I explore the Common Views interventions in the Israeli desert region as a case study of socially engaged artists working as environmental citizenship practitioners using reenactment strategies based on histories and local traditions to promote sustainability. I focus particularly on the agenda of preservation and reenactment of local heritage and histories to strengthen identity in the repressed community, as well as on the application of practical sustainable tools. These artistic strategies in essence reenact historical traditions, allowing participants to reimagine the vernacular practices of smart use of water in a desert environment that were used in the past but are no longer in use today. Reviving and restoring past customs, traditions and practices that were part of desert life, mainly through the reuse of water, creates a platform for the local participants to renegotiate their self-determination and local identity in regard to place.

Since this is a binary space of Jews and Bedouins, the new future identity that can be built, in long-term, will be a complex, layered and hybrid identity, which is characteristic of the Bedouin minority’s spatiality as the setting, and the politicization of natural resources in Israel as a site-in-conflict. I explore the artists’ actions, which are driven by dialogue promoting the advancement of solidarity and cooperation of a community within its space and catapulting them into the role of environmental citizenship practitioners. Inspired by the Situated Solidarities and the Cultural Action approaches, the artists’ strategy is based on dialogue, focused on listening, performing a reflection of cyclical learning, establishing trust and forging solidarity, simultaneously inviting exploration. These actions serve as catalysts for potential transformation and are aimed at engendering a sense of mutual responsibility and of empathy with the “other” and with the environment (Routledge and Derickson 2015; Freire 2000) (Figure 3). As part of the socially engaged art practices implemented at a site-in-conflict, they continuously mediate and create mutually fertile grounds for contested communities or groups, acting as civic practitioners. I explore these modes of art operation as they juxtapose the environmental and the political, offering an alternative mode of sustainable heritage preservation by means of contemporary art. I argue that the collective agenda widens contemporary art discourse on collectives and their role as environmental citizenship entrepreneurs.

Figure 3.

A symbolic image that signifies the concept of Environmental Reconciliation, coined by Common Views art collective to express their artistic vision. Displayed in the first intervention Common Views: Sourcing Water in Al Baqi’a valley 2020, are a Bedouin adult with a Jewish child working together to dig a water channel for the restoration of the Bir Umm al Atin water cistern. Photographed by Dan Farberoff. Image courtesy of the artist.

Moreover, a reflexive ethnographic stance, in which the process has developed throughout the research process, acknowledges my position as an art curator and academic researcher, who has been engaged in both projects as a creative agent and participant. In the first intervention—Common Views: Sourcing Water (Al Baqi’a valley and Arad) I was an active participant in all stages of the intervention. One of my major contributions was in the dialogue with women participants and I curated the exhibition project. In the second intervention—Common Views: The Water Way (Kuseife) I served as conceptual reflector and was involved in the ongoing discussions with artists prior to and throughout the project. My close involvement in the projects, and the personal acquaintances I established with the participants, the various agencies, and the stakeholders, afforded me the opportunity to accompany all stages of the project including collection of materials in the preliminary research, and formation of participatory actions. Collection of materials and documentation was done with critical insight into future research. This unique position reflects my methodology in regard to locating information provided in this article.

In this manner, I overcame the obstacle created by the critical reading of Hal Foster on the ethnographic role played by artists in their modes of intervention in communities and the danger of presenting pseudo-documentary materials, thus creating a one-sided narrative (Foster 1996). My writing can be regarded as reflexive writing, done after a period of time that allowed questioning, observation and review of the events that took place within the historiographic and theoretical context. The art collective sought my involvement due to my research specialization in the disciplines which characterize these areas of research, and include practices of contemporary art, heritage preservation and the Israeli-Palestinian sites-in-conflict (Carmon Popper 2019).

The article seeks to utilize the interdisciplinary experience to interlace socially engaged art and environmental citizenship in Israeli art today, using Common Views intervention in Israel as an example. Therefore, I will discuss the theoretical and conceptual framework of the participatory turn, as it interlaces with artistic and civic practices. I will review theories related to collaborative art, communal and socially engaged practices, as well as the participatory art evolution which intersect with the social and the communal. Then, I will discuss the historiographic framework by means of the research context on the Israel-Palestinian conflict, focusing the research on the Bedouin minority in Israel. Based on the meeting between the two frameworks, I will explore the Common Views art collective engagement at two interventions in the “Negev” desert, which took place successively. Each one is a site-specific intervention, but differs, as I will show, in particular characteristics and emphasis, yet both are wrapped under one umbrella, as part of a long-term durational art project worldwide.

2. Theoretical and Conceptual Framework

2.1. Participatory and Socially Engaged art Practices

In recent decades, there has been a growing dominance of participatory and socially engaged art strategies. They are attributed to the intellectual climate shared by many disciplines in research and in practice, which has been broadening their scope by alluding to social, communal, and collective values. The generation of artists of the 1990s in Europe was recognized as belonging to a relational era based theoretically on human interaction and social context, and sociologically on the birth of a global urban culture, coined by Nicolas Bourriaud as esthétique rélationnelle (Relational Aesthetics) (Bourriaud 1998). It is grounded in collaborations and interpersonal relationships with the space of interventions in which they are installed, focusing on the present spectatorships as essential parts of the artworks. The dismissal of art as the object, and progression toward spatial intervention jointly released artistic creative process from individual authorship to collective production (Bishop 2006, 2011).

The relational esthetics has theoretically grounded various types of artistic practices that have prevailed in recent decades, such as participatory art, community-based art and socially engaged art projects. All practices broaden the artistic toolbox to include a collaborative dimension of social experience, to involve forms of social engagement with participants—social groups and art and non-art communities—in the creative process. Socially engaged art or social practice as coined by the West Coast scholars is an art genre of groups or collectives that experiment with art through joint continuous work in a specific place and/or specific local community, proposing alternative models for social activity (Lind 2009). Artists who adopt strategies of social involvement seek to contribute to society, where other social agents have failed, using their unique cultural capital (Atkins et al. 2008; Kwon 2004; Stiles 2004). Relational practices have attracted many discussions challenging their own definitions, the unclear borders of the genre and the direct interrelations they contain between art and life, sociability, and socialization. One of the ensuing theoretical debates, especially by Clair Bishop, have questioned the social-political perspective of the art practice, by pointing to its minor emphasis on social change and political activism, terming it relational antagonism (Foster 2004b; Bishop 2004, 2006, 2011).

These tendencies are rooted in the avant-garde movements of the early 20th century and were raised and developed in the 1960s–70s art movement (Bishop 2012). They are based on the recognition of a work of art as an action rather than an object, (Foster 1996) and share the interest in the individual and in the centrality of the relationship between art and the spectator (Almenberg 2010; Dickerman 2013). While the avant-garde predecessors are defined as art movements, argues Nato Thompson, the socially engaged art is not an art movement but a cultural practice indicating a new social order. As a social order, it challenges the establishment, the political as well as the disciplinary, as it calls into question related disciplines such as urban planning, communal work, and theater (Thompson 2012).

Foster points to the contradictions between the role of the artist as observer and that of participant. As an observer, he studies the community and reflects on it, and in this way, appropriates it. However, as a participant, he takes part in community actions as if he belongs to it, and through the mutual actions he contributes to preserving its materialistic values. Mark Godfrey adopts Foster’s notion of art practices dealing with archival knowledge, and emphasizes the artistic involvement with histories, as an emerging occupation since the 1980s. Such artists are engaged in historical research and representation to create artworks that invite the viewers to join together in memory and reconsider the ways in which the past is represented. The artists’ outcomes are described in terms of the physical presence of lost or displaced data (Foster 1996, 2004a; Godfrey 2007).

In this context, I argue that Common Views collective takes part in this wider phenomenon of artworks and history, by means of rewriting the history itself, partly in an attempt to suggest solutions to socio-political and environmental issues. However, I further argue that the collective’s interventions challenge the conventional genealogy of socially engaged and participatory art as it deals with sites-in-conflict. The set of circumstances of the Israeli–Palestinian conflict, creates a special platform that calls for action which entangle the civil with the political.

2.2. Environmental Citizenship Practices

All different types of participatory strategies have become dominant in the last three decades, due to an intellectual climate shared by many disciplines, which has been broadening their scope by alluding to social, communal, and collective values. In this context, the participatory turn is shared by the disciplines of environment and sustainability as well. The aforesaid link between community and environment appears in contemporary perceptions of environmental citizenship, as we face a deepening global environmental crisis. Environmental citizenship, unlike national citizenship, is common to all of us as citizens of the environment (Barak 2020; Mishori 2014).

Environmental citizenship practitioners make use of existing resources, urban and natural, as part of the public domain, thus paving the way for a democratic arena of action that allows dialogue between multiple voices and narratives, promoting solidarity and justice of man and environment. For those practitioners, the site is not only where constantly changing action takes place, but also its material resource that is constituent and integral to their actions. By deeply exposing the site’s components, some of which are hidden, they are able to create experiences that raise awareness to the actual surrounding, to provide support for greater visibility of marginalized issues, and bring out conflictual contents. The critical perspective challenges and subverts the hegemonic one, aims for change, and thus can be examined as a tool for indirect civic action or social resistance (Barak 2020; Mishori 2014).

It intersects with the “educational turn” while aiming to equip citizens with an adequate body of knowledge, skills and attitudes to empower them with the ability to participate as agents of social change on a local, national and global scale, acting individually and collectively within democratic means and taking into account the inter- and intra-generational justice according to the European Network for Environmental Citizenship (ENEC).3 “Education Turn” is an expression first used in art to describe practices characterized by different modes of educational forms and structures, alternative pedagogical methods and programs. Historically art strategies adopting discursive, pedagogical methods and situations were hidden in socialist countries of Eastern Europe, later to be spread in the west, and eventually in gradually growing collaboration with institutions (Rogoff 2008; O’Neill and Wilson 2010). Both uses of the term, in reference to art and to environment, shed light on various modes of educational forms and alternative pedagogical methods which are integral to those practices as they are read as civic actions.

2.3. Discussion

Operating within this shared intellectual climate, however, the Israeli case differs in favor of political and civic conflictual circumstances. The Israeli case is particularly pertinent, since it represents a site of multicultural communities, which has borne intensive activities seeking on the one hand, the formation of a local Jewish identity in respect to the question of their historical link to their ancestral home, and on the other hand, that of the local Bedouin traditions, narratives and identity, its recognition, and its civic right as a minority in Israel. This significant social binary, fluctuating between Jewish and non-Jewish, renders the inquiry of the past within Israeli culture, fertile ground for investigation of hybrid, complex and stratified local identities.

I reexamine the ways in which the art collective activates spatial and collective practices in order to understand their substantive and conceptual contribution to promote long-term social change. The artists’ vision is driven by the concept of a dialogue promoting the advancement of social solidarity and cooperation of communities, some of which are competitive with the place, hence taking the role of environmental citizenship practitioners. In this light, the art interventions become civic acts. I argue that although Collective Views takes part in the agenda of various acting community engagement initiations, emphasis on socio-environmental entrepreneurship, they are also involved in the civic and political aspects of the sites that characterize the Israeli “Negev” desert and serve as a model for collaborative art performed at conflictual sites.

Moreover, I argue that by turning to the modus operandi of art practices, the artists have managed to fathom the multilayered history of the sites and offer alternative modes of preservation and commemoration of local traditions and vernacular heritage. While offering alternatives to the hegemonic historicizations, their set of actions mark a shift from the critique of power relations to interventions in the processes through which history is remembered and narrated. In this manner their activities in the local Israeli arena explore the role of art as a form of rewriting local history.

The contribution of rewriting local history is based on the act of reimagination of the past through contemporary perspective, and therefore suggests a renegotiation of identity and self-determination. Dealing with imagination of the past as a strategy, resembles the concept of “Civil imagination” coined by Ariella Azoulay, which seeks out relations of partnership and solidarity that come into being at the expense of sovereign powers. The concept deals with civil inequality and offers partnership as the base for reimagining and reconstructing collectivity in which both the ruling and the opposing powers participate, in order to go beyond the familiar concept of citizenship conditioned by the sovereign rule and the institution of the State, in the act of imagining which in the case of a common landscape, the artists also seek to implement (Azoulay 2012).

While much work in the aforesaid disciplines has focused on international discourse, local Israeli discourse, other than the interpreted documentation of the collectives themselves, regarding other collectives which in Israel use similar practices and strategies in favor of social and civic change, has been rather underdeveloped and not much research has been devoted to the unique aspects of the Israeli case as a site-in-conflict model.

3. The Israeli Bedouin Spatiality: Natural Source Politicization

3.1. The Historiography Turn

The transitional processes of the Israeli Bedouin have been extensively studied from economic, social, and spatial perspectives and have been framed mostly within the broader context of nation-state vs. indigenous politics, during the military rule in the region until the mid-1960s. After the 1967 war, Arab scholars relied mainly on Palestinian oral history, aiming for a broad picture on the Arab narrative during the war and its aftermath. Research has recently begun to explore critical social theories that focus on human agency as a venue for the analysis of Bedouin spatiality and their reciprocal relations with social practices, constructed identities and sense of place (Karplus and Meir 2014).

Since the late 1980s, we have witnessed the emergence of an anti-hegemonic intellectual phenomenon which revisited various notable chapters in Israeli history, soon dubbed as the “New Historians.” They challenged the Zionist narrative, the Israeli establishment, accusing its agents and mechanisms of discrimination against the Palestinian minority and appropriation of its lands.4

In the last two decades, research has begun to focus on the political and ethnic aspects of the Bedouin community and on issues of civil and land rights in general. This line of discourse has highlighted the lack of home, as a metaphorical concept in the Bedouin community—their need for culturally appropriate spaces. More specifically, it supports their demand for a land-territory-place nexus emanating from their indigeneity and their economic and social marginality. A recent byproduct of the vivid discussion on the conflict and its implications, is the question of the Bedouin place. This rather new line of research has dredged up an array of distorted Bedouin interactions with space, manifested in a negative sense of place, along with prevalent emotions of alienation and belonging to places. These include their nomadic heritage as a state of mind, landlessness as war refugees and uprooted populations, being a cultural ethnic-religious-national minority in Israel, economic and social weakness, unequal development policy by the State, and lack of diversified settlement options and residential opportunities. Several factors have been suggested to be responsible for this distortion. As these studies refer to the connection between the Bedouin and the place, the art collective as well, commences from the same point, in which the place is a common place in the sense of shared interests of Bedouin and Jew alike, from an ecological perspective (Abu Rabia 2002; Yiftachel 2005; Ben-Israel 2009).

3.2. The History of Bedouin Spatiality and Civility in the Desert Region

Within contemporary Israel, the Bedouin constitute an indigenous Arab-Muslim ethnic minority, settled mainly in the “Negev” (Arabic: Naqab) region of southern Israel (Suwaed 2015). However, Bedouin tribes throughout the wide MENA (Middle East and North Africa) region have lived in the desert for decades, and thus inhabited the “Negev” Desert since the 5th century, organized traditionally into nomadic or semi-nomadic tribes, grazing herds, and engaging in seasonal agriculture. The Bedouin of the Naqab Desert are among the indigenous Palestinian Arabs who remained on their land after Israel was established in 1948. During the last five decades, the Palestinian Bedouin of the “Negev” have undergone tremendous changes, including dislocation, massive land confiscation, and forced urbanization. In 2006, they numbered about 200,000 and comprised 25% of the region’s population (Abu-Saad 2011). Despite urbanization and modernization processes that have gradually increased, they maintain ancient norms and traditional values which include holistic, individual, and communal, perception of the land, which inherently sustains their identity, and as such, creates a loss of identity with the loss of their lands (Kersel 2018).

The 1948 war which concluded with the establishment of the State of Israel and the Nakba (catastrophe) for the Palestinians, had a profound impact on the area, which is evident till today. Until 1948, the Bedouin were scattered mainly in the northern “Negev,” while obtaining special conditions honoring their land under the former Ottoman and British rules (Kedar et al. 2018; Suwaed 2015). During the course and aftermath of the war, their vast majority fled under threat of war, or were expelled and became refugees in the surrounding Arab countries and in the Palestinian territories. Many others were forced to be confined to a designated military-administered area in the northeastern “Negev” Desert (the Siyag area) and their movements were firmly restricted. The Israeli authorities took control of most of the land, so the Bedouin lost the freedom to move around with their herds and were unable to cultivate their lands, having been declared State land. Consequent reduction in areas of migration and grazing damaged their main source of livelihood, and became one of the factors that signaled the end of nomadism and the initiation of permanent accommodation (Abu-Saad 2011).

The heart of this land dispute lies in opposing conceptualizations of ownership, possession, and land use. On the one hand, the Bedouin claim land rights based on customary and official laws, possession, and cultivation of the land for generations, and tax payment to previous regimes, which, in their views, should provide proof of ownership and be integrated into contemporary land laws from Ottoman and British statutes. On the other hand, Israel, drawing on a highly formalistic approach, views many of the Bedouins as illegal trespassers invading State property (Kedar et al. 2018). This situation has led to the creation of a series of governmental bodies which put regulations into effect, to take formal control of refugee property initially referred to as “abandoned lands” and govern its usage from the 1950s and onward. Therefore, since the 1950s, the Bedouin population has been dispersed in tribes, villages, rural settlements, most of which are officially classified as “unrecognized” and “illegal” (Fischbach 2003). Since Israel has dedicated major efforts to secure their control over the land of the “Negev” region, most Bedouin claims to return were firmly rejected on the ground that their claim for ownership lacks legal validity, and they have been entangled in a protracted legal and territorial battle over traditional tribal land.

The end of the military administration in 1965 marked the beginning of governmental attempts to further regulate Bedouin settlement. In the late 1960s and early 1970s, the government developed plans for resettlement of the entire “Negev” Bedouin population into urban-style towns, rationalized by modernization which would enable efficient provision of services. It began with the establishment of “seven planned towns”, based on morphological principles of middle-class suburban settlements. Many Bedouin were once again relocated, but now into completely new places whose design was inspired by Western, individualistic suburban-bourgeois inclinations. With very little economic development, these planned towns soon became neglected slums and tension-ridden in terms of inter-tribal, inter-kin and inter-patrilocal group relationships. Despite the dramatic upgrading of the municipal infrastructures, most of these towns became deeply desperate and socially and politically charged ethnic ghettos (Abu-Saad 2011).

Around the same time, in 1962, the Jewish city of Arad (pop. 2017~26,000) was established with the goal of settling and developing the “Negev” frontier. Arad serves as the main urban center of the area and provides various services to all communities, Jewish and Bedouin alike (Meir et al. 2019). However, the Jewish residents enjoy a water-rich town, with paved roads, leafy gardens, and sanitation facilities, which appear almost entirely disconnected from the actual realities of the neighboring Bedouin and their surrounding desert environment. For most, with some notable exceptions, the surrounding desert forms a scenic backdrop to the townscape, a place one might venture into for leisure activities, but certainly not as an environment in which one lives.

Nowadays, the Bedouin population in the “Negev” is over 250,000, all living in agrarian and urban settlements, which are split approximately 50% in “unrecognized” settlements and only 50% in the planned towns. Due to the lack of land ownership arrangements, the State persists in their refusal to develop the “unrecognized” settlements and to issue building permits and infrastructure for them as required by Israeli law. The unrecognized Bedouin villages do not appear on Israel’s official maps, and their residents have no addresses (Abu-Saad 2011). Therefore, they have been established and developed by the inhabitants themselves using lightweight material that can easily be packed up and moved. Alongside the traditional goat hair tents, they began to erect permanent tents with a stable and permanent wooden frame covered with sheets of thick fabric. Around them they have gradually added residential buildings: shacks and stone buildings. Moreover, since the structures are defined as unauthorized, they are in constant danger of demolition, and indeed continue to be destroyed by State officials.5 The uncertain situation is evident in the lack of planned road systems and special areas allocated for public purposes, as well as the lack of integration into national and regional physical modern infrastructure systems such as water, sewage, electricity, public transportation, and proper access to education and medical services (Noach 2009) (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Makeshift structure for Bedouin residence in the “Negev,” desert environment, 2020. These structures, defined as “unauthorized” as many others in the area, are in constant danger of demolition. Therefore, they have been erected by the inhabitants themselves using lightweight material that can easily be packed up and moved. Photographed by Dan Farberoff. Image courtesy of the artist.

The State’s spatial policy toward the Bedouin reflects the departing directions as both sides are trapped within their respective ideologies of control and resistance. It has been formally refraining from expropriating these lands unless the holders are willing to accept compensation or an alternative land parcel elsewhere on State land in exchange for relocating, in which case their claim is accepted retroactively. This state of affairs thus represents a zero-sum approach by both parties. For the Bedouin, this implies exclusion from the State support mechanisms even though, as noted, they continue their life within a highly constrained reality in their villages. For the State this implies a negative impact on its governance capabilities (Meir et al. 2019). Yet, in practice, movement of local or civil society and NGO organizations has recently emerged for purposes of public representation and welfare support in local communities.

In this complex context, the Common Views collective proposed to act in favor of raising awareness, which would eventually lead to social and civic change under State regulation. This article pinpoints three characteristic settlements, the agrarian “unrecognized” village of Al-Baqi’a, the planned recognized town of Kuseife, and the Jewish city of Arad, which is located in between them.

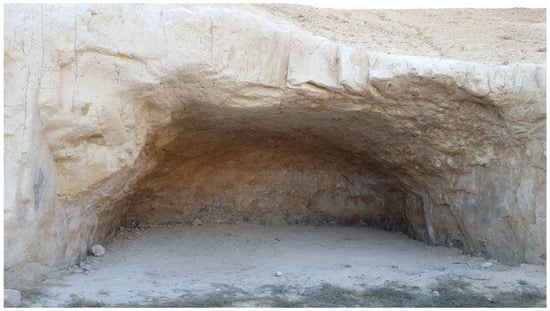

3.3. Water and Way—Desert Life Essential Natural Sources

The significance of stability in water supply is inarguable. Despite the ancient romantic myths attached to water and water cisterns, they are an essential part of desert living conditions. Cisterns and dug water tanks are an ancient phenomenon that have provided for desert dwellers for millennia. Archaeological research indicates that since the Iron Age, storing water near the settlements was common in this area of the Judean Desert, mainly due to the limestone found there, which is suitable for quarrying water and preventing infiltration. Water cisterns located at the bottom of the slope collect rainwater which reaches them through channels stretching the length of the slopes (Ben Joseph 2011; Tzuk 2005) (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

(a,b) Examples of few of the typical water cisterns found in the area of the “Negev” desert, which until only a few decades ago served as the principal water source for the Bedouins, and nowadays are neglected and unused. The photograph was taken during the artists research tour of the area in 2019, when they were accompanied by one of the Bedouin residents. Photographed by Dan Farberoff. Image courtesy of the artist.

The Bedouin inhabitants used to rely on rainwater harvesting for all their needs, and usually settled near water sources. They carried water on camels and donkeys, which were later replaced by modern tractors and tankers until the laying of a national water pipeline from the city of Arad to Mount Masada in the 1960s, influencing the water supply structures. The recognized town of Kuseife, located along the main road leading to city of Arad, was later to connect to the infrastructure supply, but its location is historically an ancient crossroad connecting major water sources in the eastern “Negev” between the settlements of Tel Arad, Tel Malhata and Be’er Sheva. Water sources and reservoirs in the desert, as well as the road systems that connect them, have been part of the legacy of Bedouin settlement heritage in the desert for thousands of years.

The unrecognized Bedouin villages of Al Baqi’a valley have been denied access to the formal water pipeline, yet their solution has become a community self-care system. Fixed taps have been added at the Kfar Nokdim Jewish tourist site, from which an unauthorized network of self-laid, sun-beaten black agricultural PVC irrigation pipes wind their way for miles, bringing precious water from the official pipeline to the isolated settlements (Figure 6). Since this water supply solution lies in a gray area, the service runs through an internal inter-family management representative. The extended family leader receives the water bill from the formal water corporation and lists it according to the count of each family based on their respective independent water clocks. This has gradually led to the Bedouin abandoning the traditional use and maintenance of the cisterns, which were subsequently filled with alluvium so that they can no longer fulfill their purpose, and by the early 2000s, were rendered unusable.

Figure 6.

An unauthorized network of self-laid, sun-beaten black agricultural PVC irrigation pipes in Al Baqi’a valley, 2020. The pipes wind their way for miles, bringing precious water from the official pipeline to the isolated settlements, since the Bedouin residents have been denied access to the formal water pipeline of the state of Israel. Photographed by Dan Farberoff. Image courtesy of the artist.

Today, issues of environment and sustainability, including climate change and the growing global water crisis, have pushed the need for preserving time-honored approaches and creative use of resources to the fore. One of these is to conserve ancient water sources and use smart traditional methods of storing water, especially in desert spaces. As early as 1971, the UNESCO Ramsar Convention expressed the importance of conserving water cisterns as one of the most vital ecosystems.6 As part of this discussion, UNESCO Man and Biosphere (MAB) program defined biosphere reserves as a model for sustainable preservation and conservation in a range of aspects, from the biological to the cultural. This model highlights the importance of preserving the natural environment in tandem with the humans and the heritage of local communities (Golan et al. 2017). In accordance with this perception, the artists seek to revitalize interest in the native tradition of rainwater harvesting, proposing to preserve and reuse existing neglected old cisterns of the Al Baqi’a valley. Yet, in the politically contested areas, adoption of the UNESCO recommendation is complicated and challenging. The water cisterns are subject to actions of enclosure by the State, due to the Israeli Antiquities Law designating them as archeological sites, where antique artifacts have been found dated pre-17th century. Therefore, any intervention in the cisterns is forbidden, which effectively precludes their maintenance. It is contextualized by the development of archaeology as a field of research in tandem with the emergence of nationalism dealing with destruction and conservation of cultural property. The Israeli archaeological practices have also established a territorial connection between the biblical Jewish nation and the new nation-state, and recast it as a political, geographical, historical, and epistemological truth (Carmon Popper 2019; See: Abu El-Haj 2001; Feige and Shiloni 2008; Kletter 2005). The Bedouin, on the other hand, view the many cisterns dotting the area as representations of their connection to the land and as an important part of their cultural landscape.

Moreover, only in 2012, a special sector dedicated to locating and preserving Palestinian heritage sites was established within the Council for the Preservation of Israel’s Heritage Sites. The present zeitgeist motivates non-governmental organizations (NGOs) and environmental citizenship agencies to expand the strict traditional codes of discipline to include social, communal, and cultural values in the context of intangible Palestinian heritage. For example, BIMKOM—Planners for Planning Rights, established in 1999 by architects and planners, offers alternative professional work to develop a practice which concentrates on strengthening the weakened and silenced social layers.

4. Common Views Art Interventions

The art collective acquainted themselves with the living conditions of the Bedouin in the valley, their political-civic situation and the condition of illegality, the communities, and their association with their environmental and natural resources. Under their leading concept of Environmental Reconciliation, the art collective treats these issues by referring to water as the desert inhabitants’ most precious and essential natural resource.

The major theme regarding water which was implemented in the art project Common Views: Sourcing Water was rainwater harvesting, reflecting on its imbalanced distribution between the Al Baqi’a settlements and the city of Arad. By referring to the tradition of rainwater harvesting and other related environmentally sustainable Bedouin practices, the collective employed native knowledge to advance an overall vision for sustainable desert habitation—linking past and future, tradition and transformation—and offering an additional entry point for local engagement (Behar Perahia and Farberoff 2022).

The Common Views: Sourcing Water project consisted of a set of actions (“steps”) to promote the preservation of the old Bir Umm al Atin water cistern, as one of a large group of old cisterns which exist in the area. The artists’ vision was to create a future walking trail—“The Cisterns Trail”—between major preserved cisterns, for the daily use of the Bedouins for tourism purposes. The Cisterns, which until only a few decades ago served as their principal water source, are nowadays neglected and unused. The trail seeks to form a link between the Jewish and Bedouin settlements—traditional and modern communities sharing a common landscape. The vision of reconciliation is implemented by the artists in various creative, socially engaged activities, to raise awareness of the control and distribution of the resource of water between Jewish and Bedouin settlements and by negotiating in favor of cooperative actions to revive traditional methods of water preservation. The vision aims to promote a practical solution to the spatial complexity of the Bedouin minority in terms of property rights and territory.

The second art intervention Common Views: The Water Way at Kuseife combined the theme of water with the theme of the desert ways to reflect on the substantial knowledge and practical tools inspired by the oral history of the elders, and their conversion for current needs. The essentially linked themes of water and way serve as a bridging tool for the artists to mediate the relationship between local communities and their desert environment, and sustainability in a broader context.

It took on the shape of a performative event in the form of the “Art and Ecology Festival,” held at the Bedouin town of Kuseife. The festival, first of its kind, was based on the topics of sustainability, environment, and desert culture, and held various activities presenting the desert heritage from the perspectives of water saving and desert roads through musical performances, folk tales, storytelling, tours, sustainable agriculture workshops and creative workshops of poetry, drawing and craft. The merging themes of water sources and desert ways emphasize their central cultural axis in desert habitation heritage. The reawakening and reimagination of traditional environmental tools and the operations of the elders, highlight the essential role played by the relationship between man and nature in the Bedouin desert culture, and promote its propagation with the younger generations, as well as between contested tribes of the urban limited space, as a source of inspiration to be used nowadays in favor of environment and reconciliation.

4.1. Common Views: Sourcing Water

The “unrecognized” settlements of Al-Baqi’a originated by the Khamisa and Khawamasha families of the Genbiv tribe and a family from the Abu Jawid tribe, members of the Dulam headquarters, who were transferred to the Al Baqi’a valley. Since then, they are spread in residential complexes of small families based on a male ancestor and his descendants, isolated in a large scattering from each other. They own herds of sheep, camels, donkeys, and horses, but are also employed in state institutions, academies, and local leisure sites. As their habitus is uncertain and temporary, their living conditions are harsh, with inadequate transportation infrastructure such as unpaved roads, the absence of basic facilities such as water and power supply, and cellular reception. It’s interesting to note, that despite the harsh living conditions, most of the elders wish to stay and become villages with agricultural tourist characteristics and are struggling to obtain State recognition and permanent housing permits (Kahana and Hanegbi 2015).

As a central aspect of the project, the artists initiated special actions to revive existing cisterns in the area, with the participation of local inhabitants and participants from further afield, employing site-specific, and community-engaged, participatory practices to touch upon the native desert tradition of water harvesting and the current distributive inequity.

The site chosen for the first act was Bir Umm al Atin cistern, located close to the Hamai’sa family’s unrecognized settlement. The cistern, dated likely to the Late Ottoman period, includes a settling pond at its entrance and canals to which surface runoff flows along the mountainous topography (Markus 1984). Nowadays, since the cistern has not been used for years, it has lost its original ability to store water for both human and animal use. Its interior was filled with alluvial soil and the water-carrying canals have been eroded, preventing the accumulation of water in the short wintertime (Figure 7). Although the Bir Umm al Atin cistern is located within the projected territory of the Bedouin family, its location is also within the projected territories of governmental, urban and military agencies such as the Israel Antiquities Authority, the Arad municipality and the regional Environmental Agency. This complex contention for ownership is reflected at all levels, with competing authorities seeking to impose control over the land and its natural resources, in which the artists were required to negotiate the power dynamics, ownership relationships and enclosure gestures.

Figure 7.

Bir Umm al Atin Cistern, Al Baqi’a valley. Cisterns, which were commonly located in the vicinity of the settlements, served as the site for a series of mediating actions in 2019–2020. Cisterns and water tanks are an ancient phenomenon that have provided for desert dwellers for millennia. Photographed by Dan Farberoff. Image courtesy of the artist.

The Bir Umm al Atin cistern served as the site for a series of mediating actions which included an introductory tour, an action to renew the rainwater harvesting channels leading to the cistern, an action to renew the cistern sedimentation pool, and finally, a performance at the site. These actions served as points of mediation for the wider Bedouin community and for the Jewish community from the nearby town and further afield. This resulted in a continuous conversation among them, which engendered solidarity, and thus formed a for-purpose community. This successful bringing together of Bedouin and Jewish children, of religious nationalists with liberals, the disenfranchised, independent women, and conservative patriarchs, to work together and collaborate meaningfully, should not be underestimated considering the region’s entrenched divisions. The cistern served as a common ground, bringing together the different interests of those with a love of nature, of “The Land”, of history, of archeology, of ecology, of culture and of tradition, while aligning their various needs with those of the environment (Behar Perahia and Farberoff 2022).

As a long-duration art project, it consists of several levels (steps) on a chronological timeline. The first essential step is to form ideas in a theoretical manner that will underlie the art vision and the modes of action, based on a process of historical and archival research for visual and textual documentation in formal and informal local agencies. Another step is to reach out to active agents such as officials, activists, community leaders, educators, and researchers, some of whom are already engaged and can offer insight into the relevant local issues. As part of this initial preliminary site-research, a fertile dialogue was conducted with Bedouin community leaders in the valley, who drive the struggle against their uncertain existential situation, with their settlements constantly under the threat of eviction. On behalf of the art practice, the focus of negotiation was on listening, establishing trust, forging solidarity that invites mutual exploration and leads to an agent network, which expands into an intricate web, encompassing various individuals and organizations, some of which are controversial.

The first operation at the site (December 2019) was an open public call dedicated to cleaning and excavating the channels for runoff water to accumulate in the cistern, based on volunteers of various ages and diverse interests from both the Jewish and Bedouin communities using excavation tools such as hoes and buckets, while working side by side for the sake of the common vision of reusing the site (Figure 8). The second public operation (February 2020) was dedicated to a comprehensive cleaning of the cistern by Bedouin schoolchildren, in collaboration with archeologists and representatives from the Israel Antiquities Authority (IAA), under their community-educational practice of “adopting a site”, as part of an environmental studies program. The final goal of preparing the cistern for functional use was not achieved due to disagreements between the archaeologists and the Bedouins concerning suitable modes of intervention such as the use of modern mechanical instruments. Representatives of the Bedouin community aspired to significant intervention at the site in favor of its establishment as an active cistern that would collect runoff water during the winter. The IAA insisted on manual excavation. This created a state of action that was more symbolic of an open dialogue and study of local traditions and desert life, rather than a dynamic act of change in the site’s status (Figure 9). Thus, the art intervention explored aspects of the site which concern access, control, agency, and authorship, and engaged the ideas of the Commons and environment as they go hand in hand with empowering individuals in the repressed community by promoting a sense of ownership and custodianship.

Figure 8.

(a–c) Volunteers in the first socially engaged act at Bir Umm al Atin Cistern cleaning and excavating the channels for runoff water to accumulate in the cistern, December 2019. Photographed by Dan Farberoff. Images courtesy of the artist.

Figure 9.

(a,b) Schoolchildren with IAA archeologist in the second socially engaged act at Bir Umm al Atin Cistern (a) receiving instruction in preparation for their work, and (b) clearing buildup of earth from the cistern, February 2020. Photographed by Dan Farberoff. Images courtesy of the artist.

Future action based on artist visions to revitalize and reawaken the native tradition of rainwater harvesting, proposes the creation of a cistern trail linking the town of Arad with the settlements in the Al Baqi’a valley and running through a number of existing cisterns along the way (Carmon Popper 2019). The marking of the water cistern trail is designed to present a tour of the public desert space and to initiate through it, a process of mutual sharing between urban and scenic communities, and Jewish and Bedouin ethnicity.

The vision has vastly expanded from a dormant proposal by local activists for a biosphere reserve that would balance the needs of the Bedouin and the desert environment at Al Baqi’a, to encompass the entire region surrounding the town of Arad, including its urban center, settlements, and nature reserves (Golan et al. 2017). This conceptual, regional plan for a social-ecological commons that brings the needs of all inhabitants and lifeforms into consideration, was developed by the collective throughout 2021, in the area of biosphere reserves of Schorfheide-Chorin and Spreewald in the state of Brandenburg in Germany. In this context, models of sustainability, such as UNESCO’s Man & Biosphere program’s biosphere reserve model, Deep Ecology philosophy, and other models that present global solutions to local challenges were reviewed.

All actions which have been carried out, and those that are planned were presented in the form of an art exhibition in the Arad Center for Contemporary Art (ACAC). The raw materials, documentation and the artist experiences, participatory actions, and working collaborative processes were transformed and translated by the artists into site-specific, formalistic structures, parts of which extend out of the gallery building into the public domain, serving as a spatial experience (Figure 10). The series of artworks included sculpture, video and sound installations, drawings, and photographic works which touch upon living conditions in the “unrecognized” settlement population and mediated issues of land ownership, control and distribution of resources, inequity, and exploitation.

Figure 10.

“Common Views: Sourcing Water” Exhibition, ACAC, Arad, 2020. Shown here are sculptures and artwork which touch on the living conditions in the desert, Curated by: Irit Carmon Popper. Photographed by Dan Farberoff. Image courtesy of the artist.

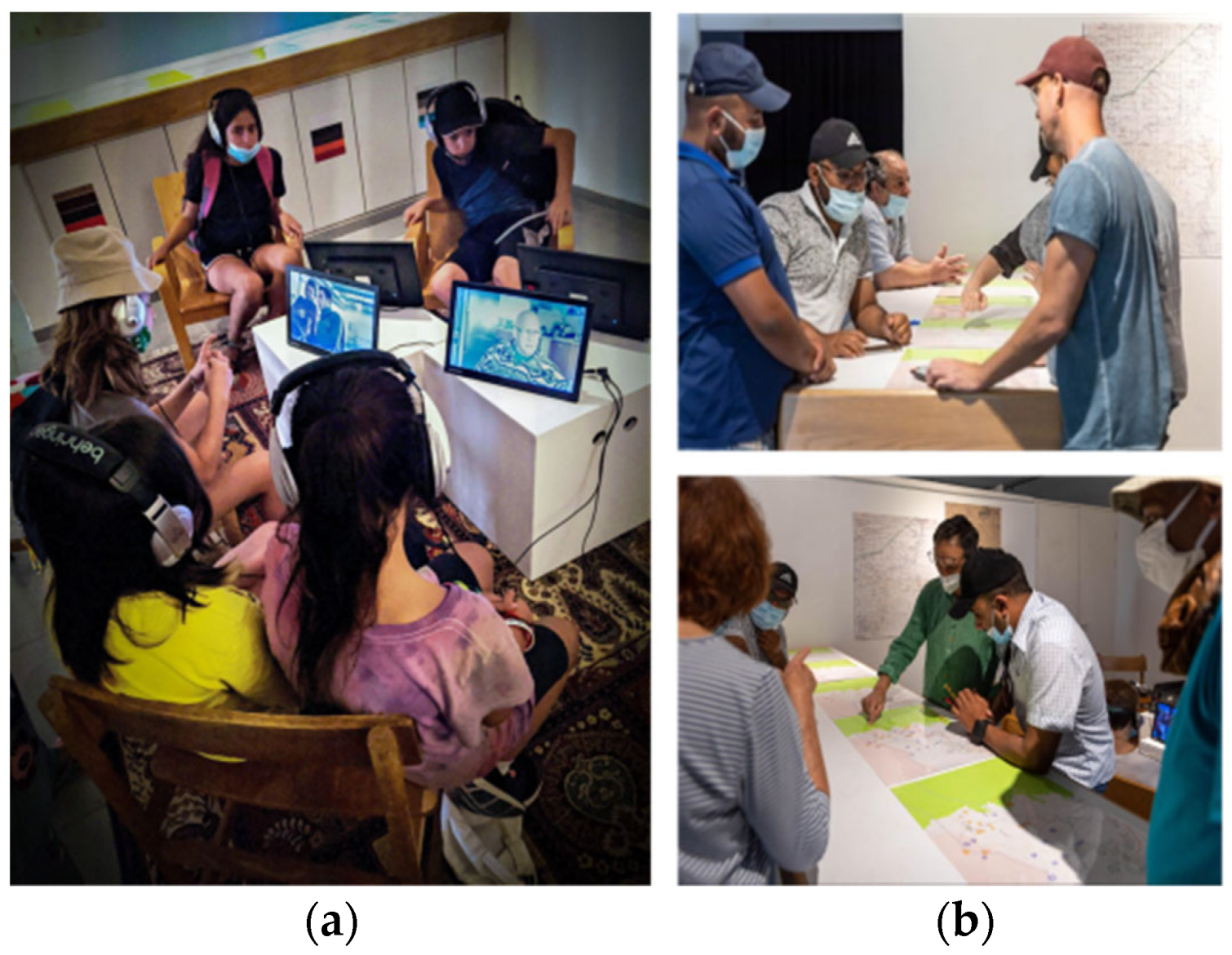

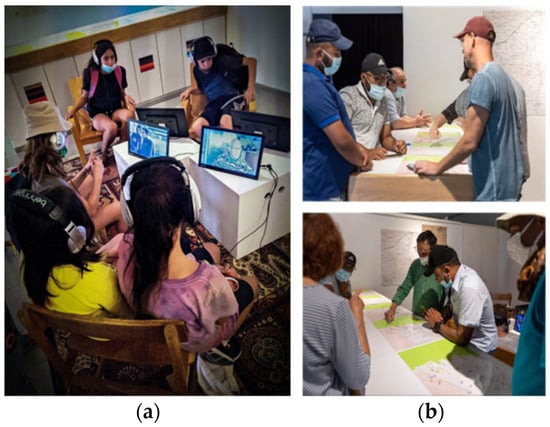

From a curatorial, conceptual, and practical process, recognizing the need to distinguish between the artworks and the archival raw materials and future vision in the exhibition space, an inner intimate space was defined at the heart of the gallery space, as an integral part of this exhibition. It was perceived as the “dreaming room” into which the audience was invited to sit, view the documentation, and review professional literature about socially engaged art history and theory to further investigate the “Negev” desert environment, the notion of Biosphere reserve and its optional implementation in the area. Strategically placed nylon maps of the area afforded the public an opportunity to mark the route they thought appropriate for the cistern trail (Figure 11).

Figure 11.

Scenes from “Common Views: Sourcing Water” Exhibition, ACAC, Arad, 2020, curated by Irit Carmon Popper. (a) “Dreaming Room”—a special space in the center of the exhibition presenting the various theoretical and historical materials of the exhibition, where the public is invited to learn and contemplate. (b) Artists Dan Farberoff (top) and David Behar Perahia (bottom) with local Bedouins from Al-Baqi’a discussing a map of the options to draw the future ‘cistern trail’—a tourist walking trail that will connect the Jewish town of Arad and the Bedouin settlements of Al-Baqi’a region. Photographed by Dan Farberoff. Images courtesy of the artist.

To demonstrate the current Bedouin challenges of water sourcing, a network of water tanks and black pipes, scavenged in the desert, was set up as the main visual symbolic art intervention in the gallery space, spilling out into the street below. This was accompanied by a series of sculptures of a Rujum—the desert way marker traditionally made of piled-up stones, as a practical and symbolic object which became a minimalist sculpture, in the form of a pyramid-shaped metal grid draped in colorful knitted surfaces, created by the women of Arad and the nearby Bedouin settlements. The participatory knitting action was based on a series of colored palettes conceived by the art collective, matching the different countries of origin of the various women, and selected by personal preference according to their traditional cultural style (Figure 12).

Figure 12.

The preparation process of the Rujum sculpture, 2020. (a) The Rujum sculptures presented at the “Common Views: Sourcing Water” Exhibition, ACAC, Arad, 2020, curated by: Irit Carmon Popper. (b) Women Knitting group from Arad Community Center, 2020. Photographed by Dan Farberoff. Images courtesy of the artist.

The first landmark on which a Rujum will be erected will be a convergence of the Desert Threshold Promenade—a future promenade circumducting the perimeter of the city of Arad, emanating from a collaboration between the art collective and the Promenade Planning Team, as part of a public participant planning in which the diverse human landscape of Arad and the Bedouin communities take part. The act of placement stems from a direct affinity between the body and space that will be expressed in a ceremonial action on site. The meaning of human presence is exposed to political and cultural coverage and is directly linked to nature and the essential connection between the desert environment and the water cycle that passes through it. The act of erecting the first Rujum will be the beginning of an annual ritual of renewing and “draping” the Rujum cyclically each year. This will be followed by future operations at the other cisterns along the trail.

4.2. Common Views: The Water Way

The art intervention Common Views: The Water Way in the Bedouin town of Kuseife focuses on two concept simulations, the concept of water and the concept of way in the sense of desert way. The combination of water and way represents the most essential signs for survival in the desert in general, and particularly in the culture of desert life.

Bedouin heritage cherishes the intersection between water and way. Major importance is attributed not only to the site of the water source as a meeting place, but to the water carriers (Waradath) and to the sacred way (Tariq’), which must not be harmed or blocked, and which ensures safe passage. The road may not be an equally open space despite being apparently a public space. Indeed, a road may be a space of exclusion. As a place, a road is thus subject to complex political and economic influences that may facilitate cultural and social encounters, but might also generate conflict and friction. The location of the town of Kuseife indicates a junction of ancient desert roads which connect major cisterns and wells that were the main water sources in the area. These kinds of desert ways are cultural axes in Bedouin tradition. Today, in the face of climate change and increasing desertification, addressing the topics of water and the ways in the desert, enables us to reflect on principles of conservation of natural resources and on human-environment relations also as a means for bringing the communities in the region closer through sustainable tools.

The town of Kuseife was established in 1982, 10 km west of Arad, as part of a wider plan of the State for the settling of the “Negev” Bedouins in 7 new Bedouin towns (Rahat, Hura, Negev Ara’ra, Tel-Sheva, Segev Shalom, Lakia and Kuseife). It was announced in 1996 as a local council in which all residents are Bedouins. Kuseife’s population includes 70% Bedouins originally from Rafiah and El-Arish, who for generations were serving the local Bedouins in various agricultural works and therefore called “Falahs” (farmers in Arabic). The other 30% see themselves as indigenous Bedouin and the original owners of the land. The town serves all residents including those of unrecognized settlements in its vicinity. It numbers 20,000 people, half of whom are under the age of twenty-one, and boasts various schools in town. For many years the mayor belonged to the Abu Rabia family, but in recent years, the mayor belongs to the larger and stronger Abu Ajaj family. The families harbor deep territorial disputes over their lands, which also cover public spaces, including educational spaces.

The project was initiated and carried out by the collective in a team effort with Saad Abu Ghanam, a local Bedouin poet and Kuseife resident. Together, they set up a creative team to negotiate the anticipated art intervention in regard to content, operation and location, with town leaders and residents, as well as with state officials, Bedouin and Jew alike, such as Ali Abu Ajaj, the Bedouin Urban Community Center Director.

Ongoing negotiations with various agencies revealed the local complexities of urban life, which required consideration and adherence to the accepted common social rules; local political rivalry, clan-affiliation, as well as the rapid change that Bedouin society is going through, and the discriminatory status of women which is evident in Bedouin society. Results of the preliminary research led the team of artists to choose groups of local women and schoolchildren to serve as agents of transformation, with the help of local creative educators and female Bedouin environmental agencies who served as mediators to unravel the intricacies of the special delicate and competitive nature of the relationships in the town. In addition, a group of community elders, serving as storytellers, became the markers of the Bedouin desert tradition, which connects the past with the future. This strategy relied on indigenous knowledge and collective memory to advance a vision for communalism and shared interests. In this context, the theme of the “way” as a traditionally neutral territory which allowed the bridging of divisions, became pivotal.7

Using the traditional ways and notions, the collective relates to the local tradition and illuminates shared values that connect all inhabitants in their relationship to the place, so as to overcome the territorial and internal tribal struggles characterizing their town. However, this mode of action seeks to touch upon current relevant issues of sustainability facing the populace due to climate change. The goals of the project are to exhibit solidarity with the various populations in the area, between groups that are usually separated on the basis of tribe, gender, or age, in favor of intergenerational exchange within the urban community. The affinity was the mutual occupation with desert nature and heritage, which was explored as part of a wider actual phenomenon, in order to increase awareness of environmental issues, the smart use and reuse of natural resources in light of increasing climate change and the global water crisis. The experiences, the actual tools and the expressions of thought and awareness were presented as universal challenges to all residents who share a common landscape.

The urban space chosen for the event was the local school complex. Its proximity was suitable not only as a neutral space lacking any territorial or family dispute, but also marked the cooperation of leaders of the urban establishment in general, and particularly, the educational establishment, with the artists, as encouragement for the residents to participate. The project, initiated and prepared by the artists in collaboration with the local community, included a variety of creative activities adapted to education for sustainability, and working with groups of schoolchildren, women, and the city elders. These activities spanned a period of one month and culminated in a festive ceremonial event to mark its completion.

The festival included a large Bedouin tent which was used, in accordance with the local traditional hospitality tent, as a communal gathering place. The tent served as a mediating factor for generating participatory, egalitarian, multi-generational discourse, and as a gallery space wherein the creative products crafted during the festival were presented and music was played. It offered a neutral location where all members of the community could gather regardless of clan affiliation. The large tent, based on the use of vernacular language and familiar materials, was used also as a hosting venue where outsiders, namely members of the Jewish community could be received (Figure 13).

Figure 13.

Kuseifa Tent, 2021. Adhering to local traditional hospitality tents, it was used as a communal gathering place. Photographed by Dan Farberoff. Image courtesy of the artist.

The “Desert Sustainability and Art” festival took the form of a two-day event celebrating water conservation and traditional Bedouin agriculture. Activities were based on creativity and sustainability, and aimed to expose and experience various means of smart utilization for saving, conserving, and preserving water, inspired by the past and traditional local knowledge, and adapted to the present, in keeping with a critical environmental and climatic perspective. The overall vision for a biosphere reserve in the area was, however, excluded to simplify the process.

The festival was open to the public, Bedouin and Jew alike, and offered various activities such as creative workshops, tours and experiments, while addressing a wide variety of audiences including women, children, and adults, all guided by the artist team and their collaborators. The activities included environmental education workshops which taught the practical tools of traditional desert agriculture used for conserving water; creative writing workshops, painting and drawing workshops, storytelling workshops, tours and walks to learn about water heritage in the area and the ancient waterways.

The ‘Desert Water’ and ‘Desert Agriculture’ workshops conformed to the principle of reviving history and connecting tradition with contemporary time. Mediated by environmental educators of the Institute for Education and Sustainability, who compared traditional solutions for the water-scarce environment with contemporary sustainable solutions for storage, conservation, and reuse of rainwater. Irrigation of crops and vegetables under desert conditions, water-scarcity, soil types, organic fertilization and irrigation were also examined through contemporary tools, to provide an answer for floods and productive agriculture (Figure 14).

Figure 14.

(a–c) Women and children participating in ‘Desert Water’ and ‘Desert Agriculture’ workshops, “Desert Sustainability and Art” Festival, Kuseife, 2021. Photographed by Dan Farberoff. Images courtesy of the artist.

Storyteller workshops ensued, with stories of desert life told by the elders of Kuseife, as well as Bedouin folk. All stories revolved around the relationship with their environment—water sources, the ways of the desert and nomadism (Figure 15). Creative writing workshops with school children produced original poetry on the topic of water and the ways of the desert (Figure 16). The festival concluded with a Bedouin music stage show with participation of the world-renowned Israeli musician Yair Dalal, and in collaboration with the Sharji Ensemble—the first Jewish-Bedouin ensemble which performs traditional and modern Bedouin music (Figure 17).

Figure 15.

Kuseife elders participating in the Storyteller workshop, “Desert Sustainability and Art” Festival, Kuseife, 2021. Photographed by David Behar Perahia. Image courtesy of the artist.

Figure 16.

The local products of the Creative Workshops at the “Desert Sustainability and Art” Festival, Kuseife, 2021. (a) Children holding their Stone Painting Workshop products and (b) Children’s drawing reflecting the water problem from their eyes, and their creative water harvesting solutions Photographed by Dan Farberoff. Images courtesy of the artist.

Figure 17.

Bedouin music stage show with participation of Israeli musician Yair Dalal, and in collaboration with the Sharji Jewish-Bedouin Ensemble, at the “Desert Sustainability and Art” Festival, Kuseife, 2021. Photographed by Or Fruchter. Image courtesy of the artist.

The artists used one of the Rujum series as a ready-made object which was re-treated and transformed from a way marker to a rainwater harvesting tool. As a socially engaged project, it was conceived as a common activity in collaboration with local residents and visitors to create an ecological sculpture with the practical function of collecting rainwater following the ancient tradition of rainwater harvesting in the area. Unlike the entire festival, which was a temporary event, the sculpture lives on at the site since the festival, necessitating continuous maintenance by local residents (Figure 18).

Figure 18.

Rujum Transforms to Water Harvesting Sculpture, permanent installation in the school yard, Kuseife, 2021. Photographed by Dan Farberoff. Image courtesy of the artist.

5. Conclusions

The two art interventions by Common Views art collective in the Israeli “Negev” desert—Sourcing Water (Al Baqi’a Valley and Arad) and The Water Way (Kuseife)—set a model to the genre of collaborative and socially engaged art at a site-in-conflict. They take part in a wider global art phenomenon, converging the artistic with the social and the communal as presented at the Documenta fifteen in Kassel (June-September 2022) which was dedicated to the topic. I argue that Common Views strategies challenge the conventional genealogy of the genre as they call for action while seeking to intertwine the civic and political with the environmental. Acting under the complex circumstances of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, their art actions rise from a critical aspect on the spatial injustice and civic inequality between Bedouin and Jewish communities sharing the same desert vista.

Both art interventions are performed in the same desert environment and located in close proximity to each other. Moreover, both pertain to the theme of water and reflect a conflictual Israeli area. The first, a long-term project which involves a Jewish city and unrecognized Bedouin settlements, deals with collaborative reconstruction of cisterns, while the second involves a Bedouin city and its various environmental and educational agencies, and deals with water harvesting in a festive event. In this sense, they contribute an interesting perspective to the discussion of the relational aesthetic theory of Bourriaud and Bishop on micro-communities and socially engaged acts. Micro-communities are small and hyper-small-scale communities engaged in mutual interests and concerns revolving around everyday human involvements in concentrated areas. They are defined in regard to a specific place and time and therefore are synonymous with the identity of a place. Micro-communities uncover activities that are not evident in traditional public policy, and local politics and micro-politics revolve around them as they represent a paradigm shift in the ways that local authorities treat fluid and shifting urban areas (Virani 2007).

The notion of micro-community relates to micro-utopia or hands-on utopia—one of the key concepts used by Bourriaud—which renounces social change through conflict, yet does not maintain the same utopian aspirations as the 20th century avant garde. He argues that utopia nowadays operates at a micro-level and has given way to everyday micro-utopias, which are incorporated into the daily construct of social life. Hence, the role of artworks is no longer to form utopian realities, but to actually become a way of life and a model of action within the existing realm (Bourriaud 1998). Bishop criticizes the artwork as a producer of micro-community in bringing together people with a shared interest in a specific place, and especially points to an exhibition space as a privileged place where micro-communities, or instant communities as she coined them, can be established to generate a particular ‘domain of exchanges’ (Bishop 2006). She argues that the exhibition serves the artist as a place for utopian transgression using the tools of art within the institutional framework of the art world. The relational artist is confronted with a strongly ambiguous situation, given that he himself is the beneficiary of that system which he desires to set in opposition to his own micro-utopias (Bishop 2004; Horváth 2016). Common Views art intervention discussed in the article might be considered under the definition of ‘domain of exchanges’, as they are judged on the basis of aesthetic criteria and therefore fit the definition of micro-communities. On the other hand, within the conflictual interstice of Isarel/Palestine, the artists take responsibility for the symbolic models of their art, as all representations refer to values that can be transposed into society and inserted into the social-ethnic fabric rather than taking inspiration from it.

Moreover, as we presently face the growing threat of climate change and a global water crisis, their actions seek to integrate with the urgent need for preserving time-honored approaches and the creative use of resources. In this manner, they are using their artistic toolbox to activate collaborative processes of environmental citizenship. This kind of action is linked to a paradigm shift from protest as a “raison d’être” toward the active proposal of an alternative and creative solution, both civic and sustainable. The artists propose using smart traditional methods of storing water, especially in desert environments, including conservation of ancient water sources such as existing old cisterns that have been inactive, and to reenact traditional agrarian methods of rainwater harvesting.